1. INTRODUCTION

In the second half of the 20th century, Portugal became involved in a heavily armed conflict on the African continent known as the Colonial War (1961-1974)Footnote 1. This war brought the Portuguese armed forces into direct opposition with the independence movements in the overseas provinces of Angola, Guinea and MozambiqueFootnote 2. Resulting in a high number of deaths and mutilations, it lasted for more than a decade and was one of the main reasons for the downfall of the so-called Estado Novo Footnote 3.

Using historical data (primary sources), combined with carefully selected secondary sources, this research is original in that it seeks to answer the following fundamental question: what were the financial costs incurred by Portugal with the Colonial WarFootnote 4? The answer to this question is important in terms of Portuguese historical culture, since it makes sense to understand all the dimensions—political, social, economic and financial—of one of the main wars in which Portugal participated as an autonomous state with almost nine centuries of history. Viewed from a more scientific perspective, the results of this study may open new research avenues in economic history, for example, by making it possible to establish comparisons between the expenses incurred by Portugal with its colonial war and those resulting from other initiatives, as well as to compare this spending with the financial costs of conflicts fought by other countriesFootnote 5.

Another aim of this study is to test whether the extraordinary military expenditure on the defence and security of overseas provinces, as recorded in the Portuguese public accounts (which included the budgetary costs of war), had any relationship with Portugal's economic growth. This is an interesting question, especially if we take into account that, for most of the time during which these expenses existed (from the late 1940s to the early 1970s), the Portuguese economy grew at its highest rates ever, in a period that became known as the Golden Age (1950-1973)Footnote 6.

After this introduction, Section 2 presents a historical overview of the Portuguese Colonial War and the budgetary impacts of military spending on public finances. This is followed by Section 3, which presents concrete estimates of the financial costs to Portugal of this conflict. In Section 4, an econometric model is estimated to test the possible relationship between the extraordinary military expenditure on the defence and security of the overseas territories and the country's economic growth. Finally, the main conclusions are presented in Section 5.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. Historical Overview

The independence of Guinea-Conakry in 1958, the problems in the British Central African Federation and the Belgian Congo, as well as the emergence of African nationalist movements in the Portuguese overseas territories, already pointed to potential problems in these regions even before the start of the Colonial War (Alexandre Reference ALEXANDRE2017, pp. 770-771). However, Portugal was not prepared for the conflict that was about to begin. The reports of the military missions in 1959 had already underlined the ineffectiveness of the Portuguese forces stationed in the overseas territories in the event of their being required to engage in combat (Moreira Reference MOREIRA, Afonso and Gomes2000, p. 321). These reports ended up being undervalued by the Portuguese government.

It is generally agreed that the event which marked the beginning of the Colonial War occurred on 4 February 1961, when groups of armed guerrillas attacked the casa de reclusão militar [military prison], the headquarters of the Public Security Police and the headquarters of the Emissora Nacional [National Radio Broadcaster] of Luanda in Angola. These attacks, which took place almost simultaneously, were perpetrated by the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola [People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola] (MPLA)Footnote 7. This was the first organised group to engage in significant anti-colonial activities in the overseas province of Angola. On 15 March, there were fresh incidents in northern Angola, involving guerrilla attacks on civilians in a wave of massacres that lasted for several weeks and resulted in hundreds of victims. Responsibility for these attacks was claimed by another revolutionary movement called the União das Populações de Angola [Union of Angolan Peoples] (UPA). These events led the Portuguese government to despatch additional military forces to defend the Angolan territory.

About 2 years later, on 23 January 1963, there was an attack in Guinea, in southern Bissau, by guerrillas from the Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde [African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde] (PAIGC)—the main anti-colonial movement in Guinea. This incident is seen as the event that marked the beginning of the conflict in this overseas province.

In Mozambique, the war started later, in September 1964, with an attack on the administrative post of Chai in Cabo Delgado by the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique [Front for the Liberation of Mozambique] (FRELIMO), the only independence movement of any significant size in this Portuguese colony.

In the different theatres of this war, which was essentially waged in the bush, Portugal mobilised more than 800,000 men (Afonso Reference AFONSO and Medina1996, p. 351; Martelo Reference MARTELO, Afonso and Gomes2000, p. 512). The statistics of Afonso and Gomes (Reference AFONSO and GOMES2000, p. 522) further show that the number of soldiers killed in Angola, Guinea and Mozambique during the Colonial War amounted to 8,290, while, according to Rodrigues (Reference RODRIGUES, Afonso and Gomes2000, p. 562), around 25,000 military personnel were evacuated with the most diverse problems (motor, sensory, organic and mental deficiencies).

At the same time as the war was being fought, Portugal was also faced with an anti-colonialist current within the UN, which was not surprising, especially if we take into account the admission of new African countries to this organisation (Alexandre Reference ALEXANDRE2017, p. 518)Footnote 8. These diplomatic problems became more acute from the beginning of the 1960s onwards, with Portugal being condemned in several UN resolutions, which soon recognised the legitimacy of the struggle that the peoples under Portuguese domination were waging in order to achieve their freedom and independence (Duarte Reference DUARTE1995; Nogueira Reference NOGUEIRA2000). Thus, the campaign against Portuguese colonial policy intensified visibly as the war progressed. Diplomatic relations with Portugal were severed by some countries—as was the case, for example, of Senegal and Congo-Kinshasa (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo)—and embargoes were placed on arms sales by some western countriesFootnote 9. On 2 November 1973, while the war was still being waged, the UN General Assembly passed a historic resolution (Resolution 3061 [XXVIII] of 2 November 1973) recognising the independence of the Republic of Guinea-Bissau and considering the presence of Portuguese military personnel in that territory to be illegal (General Assembly of the United Nations 1973, pp. 2-3).

On 25 April 1974, after decades of dictatorship, the political regime of the Estado Novo was finally overthrown. The new political decision-makers defended the independence of the overseas provinces and the self-determination of the African people. Transition phases were negotiated with the independence movements, leading to the end of Portuguese military operations (Afonso and Gomes Reference AFONSO and GOMES2000, p. 5). The demands of the independence movements in Angola, Guinea and Mozambique were accepted, with Portugal similarly relinquishing all of its other overseas provinces on African soil.

2.2. War and Public Finances

With the start of the war, military spending skyrocketed, which naturally affected the Portuguese public finances, as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1 MILITARY EXPENDITURE AND THE BUDGET BALANCE IN PORTUGAL (AS A PERCENTAGE OF GDP), 1947-1974.

Sources: Calculated with data from Ministério das Finanças (1948-1977) and Valério (Reference VALÉRIO2008).

Notes: Regarding the period chosen for this analysis, 1947 corresponds to the year in which Portuguese public finances ceased to include items relating to the Second World War (Valério Reference VALÉRIO1994, p. 28). 1974 was the year that marked the end of the war.

Military expenditure was calculated by using the Portuguese General State Accounts (Ministério das Finanças 1948-1977) to identify the expenses incurred with the armed forces, specifically the Army, Navy and Air Force. These expenses are documented in the accounts of the following Portuguese ministries: (1) Ministry of War (renamed Ministry of the Army in 1950); (2) Ministry of the Navy; (3) Ministry of the Colonies (renamed Ministry of the Overseas in 1951); (4) Ministry of Finance; (5) Ministry of Public Works; (6) General Expenses of the Nation (included in the expenditure of the Ministry of Finance until 1957, but rendered autonomous in 1958). The estimates for GDP are taken from Valério (Reference VALÉRIO2008).

To better understand the impact of military expenditure on the budget balance, it makes sense to remove a series of variables from the latter. The following items were therefore removed from the budget balance: (1) loans obtained; (2) revenue carried over from previous balances (which was a mere artifice for transferring state revenue from one year's accounts to the next; (3) amortisations of public debt; (4) interest on «fictitious» public debt (in practice, the money that was paid for certain state services and received by the state itself).

Apart from a small budget surplus in 1970, there were budget deficits in most of the years of the Colonial War. As can be seen, these deficits were higher in the first years of the conflict, reaching a maximum of 2.7% of GDP in 1964, the year when military expenditure amounted to 5.6% of GDP (whereas, in 1960, before the war started, it was only 3.2%). It is important to highlight that this war shock occurred at a time when the state's expenditure was growing more rapidly due to the stimulus to economic activity, which continued to be implemented despite the conflict in Africa.

To finance the increase in expenditure during 1961-1964, the Portuguese state resorted to a greater volume of loans. However, in the following years, more specifically between 1965 and 1973, the budget balance improved due to a higher level of tax collection, ranging between −0.9% and −0.2% of GDP. This was essentially the result of the combination of two separate elements: (1) an extraordinarily favourable macroeconomic environment referred to as the «Golden Age» of economic growth, 1950-1973; (2) an increase in taxation levels and the creation of new taxes in this positive context.

It should be pointed out that, during the so-called Golden Age, Portuguese GDP and GDP per capita each grew, on average, by 5.7% per year, corresponding to a better performance than that registered by the world economy itself, where these variables recorded average growth rates of 4.9 and 2.9 per cent, respectively, as can be seen in Table 1.

TABLE 1 GDP and GDP per capita growth rates in a series of countries, 1820-1998

Source: Maddison (Reference MADDISON2001, pp. 196-197; 262; 265).

Of the countries considered, Portugal recorded the second highest GDP and GDP per capita growth rates in Europe during 1950-1973. This fact allowed for the economic convergence of Portugal with a group of more developed countries (Badia-Miró et al. Reference BADIA-MIRÓ, GUILERO and LAINS2012).

During the Golden Age, there was a large accumulation of physical capital in the Portuguese economy, with total factor productivity growing at an even faster pace. On the other hand, it was the industrial sector that grew at the fastest rate, with Portugal having undergone a strong industrialisation process. Portuguese economic performance between the early 1960s and early 1970s was particularly noteworthy, with the average growth rate of its real GDP exceeding 6% (see also the data from Valério Reference VALÉRIO2008).

In the literature on this subject, it is possible to find several explanations for the Portuguese performance (Lains Reference LAINS1994, Reference LAINS2003; Silva Lopes Reference SILVA LOPES1996; Mata and Valério 2003; Costa et al. Reference COSTA, LAINS and MIRANDA2011; Coppolaro and Lains Reference COPPOLARO and LAINS2013; Mateus Reference MATEUS2013; Reis Reference REIS2018). One of the most important factors was the orientation of Portuguese economic policy towards the promotion of economic growth, with Portugal having implemented, for this purpose, the so-called Development Plans (1953-1974), which called for heavy investment, especially in the sectors of industry, energy, and transport and communicationFootnote 10. Another decisive factor was the relative liberalisation of the Portuguese economy and its integration into the world economy, which resulted in its greater openness to the outside, one of the main results of the international agreements that the country had signedFootnote 11.

In this favourable economic environment, a major tax reform was introduced between 1958 and 1966 (Valério Reference VALÉRIO and Valério2006; Sousa Reference SOUSA2012; Ferraz Reference FERRAZ2015). Due to its importance, particular emphasis should be placed on the creation of the Tax for Overseas Defence and Development in 1962, with the aim of raising funds to be used directly for the defence of the overseas provinces. This tax was levied on companies that exploited public service concessions or were engaged in industrial activities that benefited from special privileges in the market (Diário do Governo 1961a; Diário das Sessões 1962, p. 129). Subsequently, a customs reform was introduced in 1965, which resulted in a significant increase in import duties (Diário do Governo 1965a). Also in 1965, the capital gains tax was created, which was levied on the gains made through various activities, such as, for example, the sale of land for construction or the incorporation of reserves into the capital of companies (Diário do Governo 1965b). Finally, in 1966, the Transactions Tax (the predecessor of the present-day VAT) was created, which was levied on the sale and exchange of goods, services and financial assets (Diário do Governo 1966a). The Transactions Tax was the most important tax to be levied during the period 1971-1974.

The combination of these two aspects—strong economic growth and the increase in, and creation of, taxes—made it possible to obtain greater tax revenue, which enabled the Portuguese state accounts to remain relatively controlled and stable. In other words, none of the deficits recorded exceeded the limit of 1% of GDP during the period from 1965 to 1973, despite the war. It should, however, be noted that the public accounts deteriorated in the last year of the conflict (1974), which also marked the transition of the political regime from the Estado Novo to democracy and the effects of the first international oil shock. In a more adverse external environment, this decline was essentially due to the increase in military expenditure and the increase in expenses with the Development Plans, as well as a series of social measures adopted after the fall of the Estado Novo regime, as was the case, for example, with the increase in the wages of civil servants (Carolo and Pereirinha Reference CAROLO and PEREIRINHA2010; Ferraz Reference FERRAZ2017).

3. ESTIMATES OF THE COSTS OF THE WAR

Afonso and Gomes (Reference AFONSO and GOMES2016, p. 338) revealed the existence of a document issued by the Direcção do Serviço de Administração e Finanças do Estado Maior General das Forças Armadas [Administrative and Financial Directorate of the Armed Forces] (EMGFA)—Portugal's supreme defence body. Dated 17 December 1974, this document shows the total amount of the expenses recorded by the Portuguese armed forces in Portugal's overseas territories during the period 1960-1974.

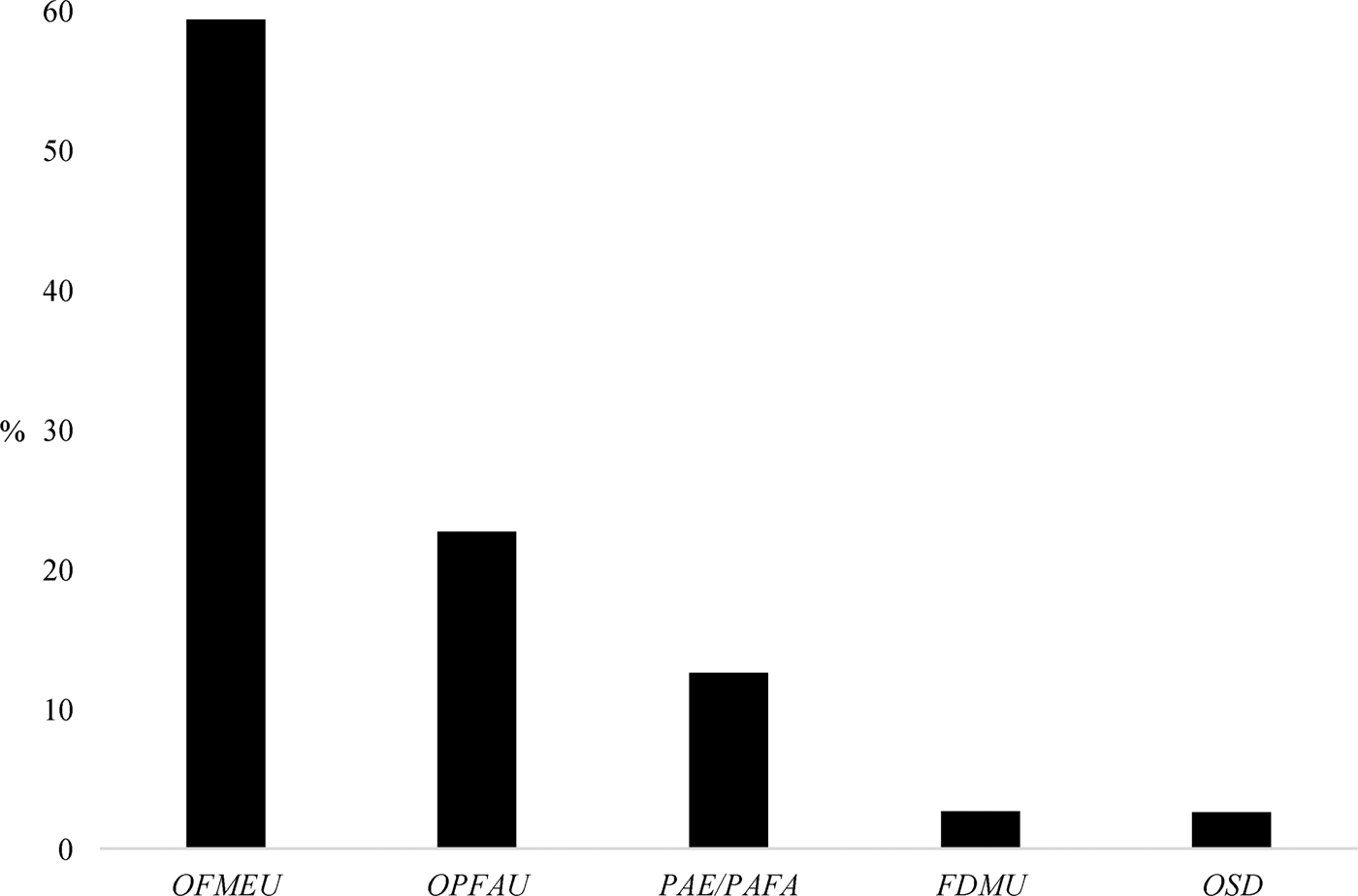

The amount mentioned was paid through the following budgets: (1) Orçamento para as Forças Militares Extraordinárias no Ultramar [Budget for the Extraordinary Overseas Military Forces] (OFMEU)Footnote 12; (2) Orçamento Privativo das Forças Armadas Ultramarinas [Private Budget of the Overseas Armed Forces] (OPFAU)Footnote 13; (3) Plano de Reequipamento Extraordinário do Exército e da Força Aérea [Extraordinary Plan for the Re-equipment of the Army and Air Force] (PAE/PAFA)Footnote 14; (4) Fundo de Defesa Militar do Ultramar [Overseas Military Defence Fund] (FDMU)Footnote 15; (5) Orçamento Suplementar de Defesa [Supplementary Defence Budget] (OSD)Footnote 16.

Thus, using the EMGFA document made available by Afonso and Gomes (Reference AFONSO and GOMES2016, p. 338) and also using the Portuguese General State Accounts (Ministry of Finance 1961-1977), Figure 2 was constructed to illustrate the contribution of each of these budgets to the total amount spent on the Portuguese overseas armed forces during the period 1960-1975.

FIGURE 2 EXPENSES PAID BY OFMEU, OPFAU, PAE/PAFA, FDMU AND OSD (AS A PERCENTAGE OF THE TOTAL AMOUNT SPENT ON THE PORTUGUESE OVERSEAS ARMED FORCES), 1960-1975.

Sources: Calculated with data from Ministério das Finanças (1961-1977) and Afonso and Gomes (Reference AFONSO and GOMES2016, p. 338).

Note: There are differences between the values presented in the EMFGA document and those that are recorded in the General State Accounts, more specifically regarding the expenditure of OFMEU and PAE/PAFA in the period 1970-1974. On the other hand, unlike the EMFGA document, the Portuguese public accounts also show the amounts that were spent on those two items in the year 1975. Therefore, Figure 2 includes adjustments to the values of the EMGFA document, based on the information contained in the General State Accounts (which are an official source of public information).

As can be seen, it was the OFMEU budget that accounted for the largest share of the expenses incurred with the overseas armed forces, amounting to roughly 60%. According to Simões (Reference SIMÕES, Afonso and Gomes2000, p. 517), these expenses «provided the budgetary measure of the costs of the war», in other words «the money actually spent on the Overseas War», as stated by Cunha (Reference CUNHA2014, p. 78). On the other hand, these expenses also enable us to understand «how the war had turned into the dangerous defence of a prejudice» (Martelo Reference MARTELO, Afonso and Gomes2000, p. 514).

Although the OFMEU expenses only appeared for the first time in the State Budget of 1960, as explained by the Portuguese Minister of Finance, António Manuel Pinto Barbosa, this amount only showed the expenses that already existed for the defence and security of the overseas territories (Diário do Governo 1959a, p. XCI). Thus, using the accounts of the Ministry of War (later renamed the Ministry of the Army) and the Ministry of the Navy, it is possible to calculate estimates for the expenses of the OFMEU budget before 1960, more concretely between the years of 1948 and 1959.

Figure 3 presents the evolution of these expenses as a percentage of total state expenditure in a period of both peace and war.

FIGURE 3 EXPENDITURE ON EXTRAORDINARY OVERSEAS MILITARY FORCES (AS A PERCENTAGE OF STATE EXPENDITURE), 1948-1975.

Sources: Calculated with data from Ministério das Finanças (1949-1976).

Notes: Expenditure between 1948 and 1959 was calculated using the accounts of the Ministry of War/Ministry of the Army and the Ministry of the Navy. Expenditure between 1960 and 1975 corresponds directly to the expenses included in the item «Extraordinary Overseas Military Forces» of the «National Defence» section of the «General Expenses of the Nation» account. The state's expenditure does not include: (1) amortisations of public debt; (2) interest payments on «fictitious» public debt.

It can be seen that, before the Colonial War, these expenses had little relevance within the broader context of total state expenditure. However, the beginning of the war resulted in a significant increase in spending on extraordinary forces, which increased from a share of 5% in 1960 to 18% in 1961. During the period of the conflict, the values oscillated between a minimum of 18% and a maximum of 26%, with two distinct trends. The first of these was an upward trend, which occurred between 1961 and 1967, when the expenditure on extraordinary forces grew at a faster rate than the state's overall expenditure. The second trend was a downward one, occurring between the years 1968 and 1974, in which the expenditure on extraordinary forces grew, but at a slower pace than the state's total expenditure. This second trend is explained by the large increases in expenditure in other sectors, as was the case with the education sector, whose share increased from 10% of total expenditure in 1969 to 16% in 1974 (Ferraz Reference FERRAZ2020b, p. 5)Footnote 17. In 1975, the expenditure on extraordinary forces accounted for only 8% of state expenditure, reflecting the sharp fall in these expenses in absolute terms in the first year after the end of the war.

In the period in which this conflict took place, 1961-1974, Extraordinary Overseas Military Forces absorbed, on average, 22% of state expenditure and 3.1% of GDP each year. It was in 1968 that these expenses reached their highest value as a percentage of GDP, namely 3.5%Footnote 18.

On the other hand, Figure 4 shows that, during the war, and especially in the first years (1961-1965) and in the last year (1974), the expenses with these forces significantly exceeded the budgeted values.

FIGURE 4 EXCESS EXPENDITURE COMPARED TO THE STATE BUDGET FOR EXTRAORDINARY OVERSEAS MILITARY FORCES (AS A PERCENTAGE), 1950-1975.

Sources: Calculated with data from Ministério das Finanças (1951-1977) and Diário do Governo (1949-1951, 1952c, 1953b, 1954-1958, 1959a, 1960, 1961b, 1962-1964, 1965c, 1966b, 1967-1971, 1972b, 1973, 1974).

Note: Expenses (budgeted and incurred) between 1950 and 1959 were calculated using the expenditure accounts of the Ministry of War/Ministry of the Army and the Ministry of the Navy. Expenses (budgeted and incurred) between 1960 and 1975 correspond directly to those included in the item «Extraordinary Overseas Military Forces», which appears in the «National Defence» section of the «General Expenses of the Nation» account. There were no expenses budgeted for the years 1948 and 1949.

Indeed, the first years of the war resulted in sharp deviations from the state budgets. The largest deviation—over 150%—occurred in 1961, at the very beginning of the conflict, reflecting the adverse shock to the Portuguese public accounts (as we have already seen). The last year of the conflict (1974) also resulted in a serious deviation; it was precisely at this time that Portugal reached the critical limit of its capacity to mobilise the necessary resources for deployment in the overseas territories (Afonso and Gomes Reference AFONSO and GOMES2000, pp. 4-5). On the other hand, this figure also enables us to conclude that there was a chronic under-budgeting of these expenses during the war, allowing the Estado Novo regime to portray the Colonial War as being cheaper than it actually was.

Although the spending on extraordinary military forces reflects the costs that were most directly related to the war, and which were paid through the Portuguese state budget, it should, however, be admitted that there were other expenses incurred by the Portuguese overseas armed forces that were also linked to the war. This reasoning allows us to build an interval for estimating the costs of this conflict to Portugal.

To calculate the minimum value of the interval, we can use the amount spent on extraordinary military forces plus some residual expenses relating to the mobilisation of police contingents sent to defend the populations overseas. On the other hand, in order to calculate the maximum value of the interval, we can also consider the spending paid for by the remaining budgets (OPFAU, PAE/PAFA, FDMU and OSD), which also financed the Portuguese overseas armed forces. However, to calculate these amounts (minimum and maximum), it makes sense to consider as war expenses only the values that, in each of the years 1961-1975, exceeded the amount spent in the pre-war year of 1960.

According to the estimates presented in Table 2, the Colonial War cost Portugal a minimum of approximately 21.8 billion euros and a maximum of 29.8 billion euros respectively, at 2018 prices and in the present-day currency of PortugalFootnote 19.

TABLE 2 Estimates of the costs of the Colonial War for Portugal, in thousands of euros (at 2018 prices), 1961-1975

Sources: Calculated with data from Ministério das Finanças (1961-1976) and Afonso and Gomes (Reference AFONSO and GOMES2016, p. 338).

Notes: The expenses in escudos (the Portuguese currency at that time) were converted into «euros» (the Portuguese currency since 1999) at 2018 prices using the Consumer Price Index of the Instituto Nacional de Estatística [National Statistics Institute] (INE 2019). The value of the costs incurred in each year can be consulted in Table A1 (see Online Appendix).

If we spread these two amounts over the 13 years of war, we obtain an average annual cost of between 1.6 billion and 2.3 billion eurosFootnote 20. Interestingly, this latter value is similar to the average annual amount spent on (both public and private) investments in Portugal under the Development Plans (1953-1974)Footnote 21.

The question of whether the expenses with Extraordinary Overseas Military Forces—which included the costs most directly related to the war—show any relationship with the growth of the Portuguese economy, however, remains.

4. APPLIED STUDY

4.1. Brief Literature Review

The relationship between economic growth and the expenditure of the military sector has been increasingly studied and debated over time (Utrero-González et al. Reference AFONSO and GOMES2019). Many varying conclusions have been reached by a wide range of different studies (Dunne et al. Reference DUNNE and NIKOLAIDOU2005; Hou and Chen Reference HOU and CHEN2013) regarding the positive, negative and even neutral effects of this kind of spending in an economy.

For example, Rothschild (Reference ROTHSCHILD1973) found that a high level of military expenditure was associated with lower economic growth in some OECD member countries during the period 1956-1969. On the other hand, using a sample of 44 developing countries, Benoit (Reference BENOIT1978) concluded that, in this case, there was a positive correlation between heavy defence burdens and rapid economic growth rates during the period 1950-1965. More conclusions regarding this relationship can be found in Degger and Smith (Reference DEGGER and SMITH1983), Biswas and Ram (Reference BISWAS and RAM1986), Atesoglu and Muller (Reference ATESOGLU and MULLER1990), Knight et al. (Reference KNIGHT, LOAYZA and VILLANUEVA1996), Batchelor et al. (Reference BATCHELOR, DUNNE and SAAL2000), Klein (Reference KLEIN2004), Landau (Reference LANDAU2007), Pieroni (Reference PIERONI2009), Dunne and Nikolaidu (Reference DUNNE and NIKOLAIDOU2012), Yildirim and Ocal (Reference YILDIRIM and OCAL2016), and many other studies. In fact, there is still no consensus regarding the effects of such spending on economic growth (D'Agostino et al. Reference D'AGOSTINO, DUNNE and PIERONI2019).

According to Biswas (Reference BISWAS1992), there are several transmission mechanisms. For example, the military sector incurs consumption expenses that are part of total state expenditure, which, in turn, can be an important variable for stimulating the growth of an economy. Also, military innovations can contribute towards technical progress within an economy, thus benefiting the civil sector. Viewed from a less optimistic perspective, however, military spending can also lead to lower investment in key sectors such as education and health. Seen from this same viewpoint, increases in military expenditure may lead to crowding out effects, that is, to an increase in interest rates and therefore to a reduction in private investment. These expenses may also appear to be insignificant for an economy at a given time, when compared with other more important variables.

There is even a certain ambiguity regarding the effects of a war. Armed conflicts can lead to a fiscal stimulus that boosts economic growth, as was the case with the United States during World War II (Krugman Reference KRUGMAN2009, Reference KRUGMAN2011). In fact, increases in military spending during a conflict can create jobs, promote additional economic activities and develop new technologies that can then be used by other industries (Institute for Economics and Peace 2011). Viewed from the same perspective, and according to Thies and Baum (Reference THIES and BAUM2020), war can increase GDP per capita by reducing unemployment and employing people in the war industry (such as the production of weapons and ammunition). However, it can also lower GDP per capita through the destruction of physical and human capital, reduce investments in productive sectors, and diminish domestic and foreign trade (for the impact of the wars on trade, see Glick and Taylor Reference GLICK and TAYLOR2010).

Some studies have tested the relationship between military spending and economic growth in the specific case of Portugal. Barros and Santos (Reference BARROS and SANTOS1997) and Dunne and Nikolaidou (Reference DUNNE and NIKOLAIDOU2005) did not find any relationship between military expenditure and Portuguese economic growth in the periods 1950-1990 and 1960-2002. Furthermore, Nikolaidou (Reference NIKOLAIDOU2016) concluded that Portuguese military expenditure was insignificant in promoting economic growth during the period 1960-2014. However, more recently, clear empirical evidence has been found of the effects of military spending on the Portuguese economy over a broader time horizon, from 1874 to 2018. Such spending has had both positive and negative effects on the Portuguese economy (Ferraz Reference FERRAZ2020b).

4.2. Model

To test the relationship between the Extraordinary Overseas Military Forces (OFMEU) expenses and economic growth, an ARDL model was constructed (Pesaran and Shin Reference PESARAN, SHIN and Strøm1999; Pesaran et al. Reference PESARAN, SHIN and SMITH2001), which includes lagged values of both dependent and explanatory variablesFootnote 22. This growth model was inspired by other studies that have examined the impact of a set of variables on economic growth, such as Barro and Lee (Reference BARRO and LEE1994), Huchet-Bourdon et al. (Reference HUCHET-BOURDON, MOUEL and VIJIL2018), Ferraz (Reference FERRAZ2020a, Reference FERRAZ2020b)Footnote 23:

$$y_t = c_0 + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^a \alpha _iy_{t-i} + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 0}^q \beta _i\cdot EDUC_{t-i} + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 0}^b \lambda _i$$

$$y_t = c_0 + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^a \alpha _iy_{t-i} + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 0}^q \beta _i\cdot EDUC_{t-i} + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 0}^b \lambda _i$$ $$\eqalign{LIFE_{t-i} + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 0}^w \Omega _iGFCF_{t-i} + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 0}^k \theta _iTRADE_{t-i} + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 0}^z \Phi _iOFMEU_{t-i} + c_1\;t + u_t$$

$$\eqalign{LIFE_{t-i} + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 0}^w \Omega _iGFCF_{t-i} + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 0}^k \theta _iTRADE_{t-i} + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 0}^z \Phi _iOFMEU_{t-i} + c_1\;t + u_t$$All variables are expressed as growth rates in order to obtain better results in terms of stationarity, which is an important property in time series analysisFootnote 24. Therefore, y is the real growth rate of GDP per capita. As far as the explanatory variables are concerned, we have: (1) the past values of y, which enable us to evaluate the impact on growth of the initial conditions; (2) EDU is the growth rate of the population that has completed a higher education course, expressed as a percentage of the total population (the literature shows that there is a positive relationship between the level of education and economic growth, see Barro Reference BARRO and Lazear2002, Reference BARRO2013; Mariana Reference MARIANA2015); (3) LIFE is life expectancy at birth, and represents a health indicator (this is expected to contribute positively to economic growth—see Bloom and Sachs Reference BLOOM and SACHS1998; Sunde and Cervellati Reference SUNDE and CERVELLATI2011; He and Li Reference HE and LI2020); (4) GFCF is the real growth rate of Gross Fixed Capital Formation per capita (with it being expected that total investment, both public and private, would have a positive impact on increasing the productive capacity of the economy); (5) TRADE is the real growth rate of trade openness per capita, which enables us to assess the impact of international trade on the economy (in general, the literature tends to show that economies that are more open to the outside world usually experience greater economic growth, see Edwards Reference EDWARDS1998; Frankel and Romer Reference FRANKEL and ROMER1999; and Huchet-Bourdon et al. Reference HUCHET-BOURDON, MOUEL and VIJIL2018); (6) OFMEU represents the real growth rate of the expenditure on the Extraordinary Overseas Military Forces per capita; (7) t is the time-trend that is useful in accounting for period-specific effects, such as, for example, productivity changes. The parameters to be estimated are c 0, c 1, α i, β i, λ i, Ωi, θ i, Φi, with u being the error term.

4.3. Data and Time Horizon

The time horizon for which data are available for all the variables presented in equation (1) is 1949-1975; a period that covers both the Golden Age (1950-1973) and the Portuguese Colonial War (1961-1974). In the case of the price index, total population, exports and imports, and GDP per capita, the data were taken from Valério (Reference VALÉRIO2008). Data for students who completed higher education courses were taken from Valério and Domingues (Reference VALÉRIO, DOMINGUES and Valério2001). For life expectancy at birth, the data were obtained from HDM (2017). For Gross Fixed Capital Formation, the data were calculated using Pinheiro (Reference PINHEIRO1997). For the OFMEU expenses, the data were taken directly from the primary sources, namely Ministério das Finanças (1949-1977).

4.4. Estimated Results and Analysis

The model presented in equation (1) was estimated using the OLS method with Robust Standard Errors.Footnote 25 The appropriate ARDL lag order was chosen using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Hannan-Quinn Information Criterion (HQC) and Schwarz-Bayesian Criterion (SIC/BIC).

The estimated results are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3 Estimation of equation (1) by the OLS method with robust standard errors (HAC)

Notes: The first observation (for the year 1949) was dropped in order to accommodate the lag;*,** and*** represent the statistical significance of the regressor at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. The figures shown in parentheses are standard errors; the tests were performed using Gretl (2017).

According to the tests performed, there is no evidence of any problems relating to autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity and multicollinearity. There is parameter stability and the regressors are jointly significant. On the other hand, we can see that the explanatory power of the model is not particularly high.

Some regressors display a statistical significance in period t–1 that continues through to the period t, thus providing evidence of a relationship between these variables and economic growth in the period 1950-1975. This is the case, for example, with GFCF, which had positive effects on y. This is not surprising, since in the Golden Age there was a large accumulation of physical capital under the scope of the Portuguese industrialisation process. LIFE—a health indicator—also contributed positively to y, a result that is further supported by the empirical literature. However, contrary to expectations, the lagged TRADE variable was not statistically significant in regression.

By continuing to analyse Table 3, it is possible to identify the most relevant fact: the lagged variable of OFMEU displays statistical significance in regression. This means that an increase of 1 percentage point (pp) in OFMEU occurring in a certain year t–1 was associated, on average, with an increase of 0.02 pp in y in the following year (t) during the period 1950-1975. It is important to emphasise that, although these expenses related largely to expenditure on personnel (consumption spending), the war effort of 1961-1974, which was reflected more visibly in these costs, had reproductive effects, such as, for example, stimulating investment in the Portuguese military sector for the production of vehicles, weapons, ammunition and explosivesFootnote 26. These results are compatible with the empirical literature, namely the study by Ferraz (Reference FERRAZ2020b).

It is important to highlight that the coefficient of the lagged OFMEU is, however, clearly lower than that of other variables, such as LIFE and GFCF. This also suggests the hypothesis that, if the war had not occurred, Portugal could have channelled its resources towards other initiatives, which would have increased the economic growth of the Golden Age even more.

These estimated results should, however, be interpreted with some caution, due to the evident limitations of this study, such as its small sample size and the use of only one lag in the ARDL model, as well as the dangers of omitted variable bias.

5. CONCLUSION

The Colonial War (1961-1974) led to a sharp rise in Portuguese military expenditure. This had a negative impact on the country's public finances (a war shock), resulting in a worsening of the budget deficit in the first years of the conflict, from 1961 to 1964. However, in the following years, from 1965 to 1973, the budget balance remained at a low level (below 1% of GDP). This situation of relative comfort in the Portuguese public finances during the war (in contrast to the uncomfortable scenario of thousands of dead, injured and traumatised victims) can be attributed to the increase in tax revenue motivated by an extraordinary economic conjuncture, as well as to the increase in, and creation of, new taxes as part of the tax reforms implemented by the Portuguese state in 1958 and 1966.

The expenditure on Extraordinary Overseas Military Forces (OFMEU)—involving the despatch of additional contingents for the defence and protection of the Portuguese overseas territories—accounted, on average, for 22% of state expenditure in each year of the conflict, equivalent to 3.1% of GDP. These expenses reached their highest value, namely 3.5% of GDP, in 1968. Such figures suggest that this expenditure was a heavy and prolonged burden.

The estimates presented in this paper also show that the costs borne by Portugal with the Colonial War amounted to between approximately 21.8 billion euros (minimum estimate) and 29.8 billion euros (maximum estimate) at 2018 prices and expressed in the present-day Portuguese currency. It also means that, on average, each year of the military conflict cost Portugal between 1.6 and 2.3 billion euros. This last value is similar to the average annual amount invested in Portugal under the scope of the Portuguese Development Plans (1953-1974). This is an interesting fact, since the defence of the overseas provinces and economic planning (which made the Portuguese industrialisation process possible) were the two main stated objectives of the Estado Novo regime after the Second World War.

Additionally, by estimating a dynamic model, it was found that an increase of 1 percentage point (pp) in the real growth rate of the expenditure on Extraordinary Overseas Military Forces per capita in a certain year t–1 was associated, on average, with an increase of 0.02 pp in the real growth rate of GDP per capita in the following year (t), during the period 1950-1975. We cannot, however, fail to admit the hypothesis that, if the Colonial War had not occurred, important resources could have been directed towards more productive sectors, which would have boosted the Portuguese economy even further during the Golden Age. Although the results of this applied study are supported by the empirical literature, they should, however, be interpreted with some caution, due to certain limitations and risks that have been identified in this study.

The findings presented in this paper represent a unique contribution to contemporary economic history. The paper not only presents concrete estimates of the financial costs incurred by Portugal with the Colonial War—one of the most important conflicts in its history—but it also provides empirical evidence of a statistically significant relationship between the military expenditure incurred with the defence and security of overseas provinces (which included the costs of war) and Portuguese economic growth.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0212610921000148

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank Professor Blanca Sánchez Alonso and two anonymous reviewers for their important comments and suggestions which helped me to improve my paper. I am also grateful to Professors Nuno Valério, Álvaro Garrido, António Portugal Duarte and Pedro Bação for the extraordinary support that they gave me. This article received financial support in the form of national funds made available by FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia), Portugal (Project UIDB/04521/2020).

Appendix

TABLE A1. Estimates of the costs of the Colonial War for Portugal, in thousands of euros (at 2018 prices), annual data