1. INTRODUCTION

A growing literature (Álvarez-Nogal and Prados de la Escosura Reference Álvarez-Nogal and Prados De La Escosura2013; Henriques Reference Henriques2015; Álvarez-Nogal et al. Reference Álvarez-Nogal, Prados De La Escosura and Santiago-Caballero2016; Palma and Reis Reference Palma and Reis2019) argues that living standards in the Iberian Peninsula had a head start relative to most of Europe. According to these authors, the countries born of the Reconquista were high land/labour ratio frontier economies that benefitted from relatively more favourable natural endowments until well into the 16th century. This literature, however, did not address the issue of the availability of capital. Even in largely agrarian economies, favourable natural endowments are not a sufficient cause for growth. The key sectors of 13th- and 14th-century Iberian agriculture required a great deal of investment; without livestock, drainage, irrigation and a variety of capital goods the conquered territories could not become productive, however vast they were. Vineyards, in particular, required terracing and were high-maintenance assets, threatened by rapid obsolescence.Footnote 1 Some 14th-century observers even complained that shortage of stock prevented the adequate exploitation of the abundant reconquered lands in the south (Henriques Reference Henriques2015, p. 3).

There are reasons to argue that frontier or settler economies struggle with the scarcity of capital and with high-interest rates. Adam Smith (Reference Smith1981 [1776], p. 106) contrasted the low-interest England of his day, where loans were available for as little as 3.5 per cent, with the American colonies where market interest rates ranged from 6 to 8 per cent (see also Homer and Sylla Reference Homer and Sylla2005, p. 271).Footnote 2 For Smith, factor endowments explained this difference: «a new colony must always for some time be more under-stocked in proportion to the extent of its territory (…) than the greater part of other countries» (Smith Reference Smith1981 [1776], p. 109). This is confirmed by empirical work on 19th-century Argentina and Canada (Adelman Reference Adelman1994) and also for 13th-century Holland (van Bavel and van Zanden Reference van Bavel and van Zanden2004, pp. 512–513).

In this paper we show that 13th- and 14th-century Portugal benefitted from lower interest rates than most contemporary European countries. We argue that the favourable factor endowments contributed to, rather than prevented, low-interest rates. As early capital markets depended on property for collateral, the wide availability of land typical of frontier economies made borrowing easier. Lower interest rates cannot solely be ascribed to factor endowments, as institutional conditions including the stability of the money supply and the protection of property and creditor rights also played a major role.

This conclusion is built upon an entirely new dataset of interest rates and returns on capital for Portugal in the period 1230–1500. As acknowledged by Álvarez-Nogal and Prados de la Escosura (Reference Álvarez-Nogal and Prados De La Escosura2013, p. 9, note 46), the neglect of the issue of the availability of capital is largely due to the lack of relevant data, a gap we hope to fill here by bringing forward new data on interest rates and returns on capital for Portugal in the period 1230–1500. Mostly drawn from unpublished sources, this dataset is instrumental to the main purpose of this research which is to understand whether the Portuguese frontier economy struggled with the scarcity of capital.

The other goal of this paper is to provide a Portuguese viewpoint on a crucial period of European financial history. From the 14th century onwards the continent saw a sustained decrease in interest rates both in private and public credit markets (Epstein Reference Epstein2002, p. 62). It is difficult to exaggerate the importance of this process for the long-term economic growth of Europe, even more so given that it was unique to the continent, as neither China nor India experimented anything comparable (Gupta and Ma Reference Gupta, Ma, Broadberry and O'Rourke2010). The reasons for this decrease remain in doubt, with researchers divided between institutional explanations (Zuijderduijn Reference Zuijderduijn2009; Chilosi et al. Reference Chilosi, Schulze and Volckart2018) and the dramatic change in factor endowments caused by the Black Death, as advanced by Epstein (Reference Epstein2002), Campbell (Reference Campbell2009) or van Bavel and van Zanden (Reference van Bavel and van Zanden2004). When comparing different European settings, the case of Portugal suggests that the drop in the level of interest rates was due to a combination of the improvement of per capita factor endowments with favourable institutions, especially those related to money and coinage.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Based upon the existing literature, Section 2 briefly outlines Portuguese credit markets and their main financial instruments. Section 3 presents the new dataset that will be used in this paper, while Section 4 analyses the available data on the moneylending market. The data on the interest rates on perpetuities and on the return on capital is analysed in Sections 5 and 6, respectively. Section 7 presents an international comparison of interest rates and discusses the reasons for the European-wide decrease in interest rates. Finally, the conclusion answers the questions posed in this Introduction.

2. CAPITAL MARKETS IN PORTUGAL, 1230–1500

Early Portuguese capital markets have received comparatively little attention from economic historians. The most valuable research is decades old and did not address the level of interest rates. Legal historian Almeida Costa (Reference Costa1961) carried out a thorough analysis of the legal origins and development of censos until the mid-14th century from a comparative perspective, whereas Themudo Barata (Reference Barata1996) studied the interplay between commercial credit and the different types of contracts in place. Barbosa (Reference Barbosa and Barbosa1991) and Durand (Reference Durand1982) focused on the social consequences of credit and indebtedness in the regions they studied.

From their different standpoints, these authors did agree that credit was widespread in 13th- to 15th-century Portugal and spanned the urban/rural divide. In particular, Durand (Reference Durand1982, pp. 256–271) showed that credit contracts between private parties are common in the Portuguese archival collections. The spread of credit can also be confirmed in the numerous wills that survive which often mention extant loans both to be redeemed or to be demanded by the executors of the will (Vilar Reference Vilar1995; Morujão and Saraiva Reference Morujão and Saraiva2010). Thirteenth-century personal and monastic accounts also contain numerous mentions of loans owed (Pedro Reference Pedro2008).

The spread of credit contracts in Portugal is not surprising given that this was the norm on the European continent (Furió Reference Furió and Berthe1998; Gilomen Reference Gilomen and Berthe1996; Zuijerduijn Reference Zuijderduijn2009, pp. 5–8). Nevertheless, as stressed by the literature (Epstein Reference Epstein2002, pp. 61–62), there were major differences between «advanced» cities or highly-urbanised regions and «backward countries». From the 12th century, European financial innovation was driven by Italian cities, whence it spread to the rest of the continent (Felloni Reference Felloni2008). The first adopters of the Italian innovations were densely-urbanised areas such as Flanders or the northwestern German lands which eventually became pioneers in their own right (Munro Reference Munro2003) and, as explained in a recent paper (Chilosi et al. Reference Chilosi, Schulze and Volckart2018), had more integrated capital markets than in Italy.

In light of this divide, Portugal, a little-urbanised country of dry plains and mountains interspersed by small agro-towns (Henriques Reference Henriques, Freire and Lains2016, p. 33) is very different from the innovative hubs of Central Europe or the Mediterranean. Unlike the Flemish, Aragonese or Italian towns, Portuguese municipal governments did not issue long-term debt instruments and the country as a whole relied on Italian merchants for financial services and did not develop a large banking sector (Barata Reference Barata1996; Farelo Reference Farelo, Hernández, Sánchez Ameijiras and Falque2018).

However, as implied by Chilosi et al. (Reference Chilosi, Schulze and Volckart2018), financial sophistication does not necessarily equate to sound institutions. On the whole, Portuguese institutions do not appear to have been powerful impediments to the emergence of a capital market. Property rights appear well-defined, with operational legal distinctions between different rights over the lands already matured in the middle of the 13th century (Costa Reference Costa1982). This has important consequences for the capital market, as it allows potential investors to resort to their property as collateral in order to raise capital. Well-defined property rights existed alongside a strong notarial culture in which contracts were public, followed rigorous protocols and were registered by notaries. As in other European states, notaries public kept public registers of contracts and reduced information asymmetry by acting as brokers. This culture was a positive influence on the capital markets as it supplied the necessary formal assurances for both parties.

The rights of the creditor were protected by the royal courts and by executive decisions, as shown in the way the ecclesiastical institutions recovered their credits after the turbulent 1370s and 1380s (Ferreira Reference Ferreira1989) and how the crown forfeited property on behalf of Jewish lenders (see Section 4). Likewise, forfeiture of collateral also followed seemingly well-oiled procedures as early as the first half of the 13th century (Roldão Reference Roldão2007, pp. 22–24).

Finally, for a large part of the period covered here, lenders could count on monetary stability. In fact, from 1261 to 1369, the King of Portugal operated under a strict «monetary constitution» that forbade the monarch from significantly changing the money supply as well as the fineness of the circulating bullion (Henriques Reference Henriques2008, p. 109). This meant that debasements and other forms of monetary mischief would not affect the value of interest rates, even in the case of credits with long maturities.

The institutions outlined in the previous paragraphs encouraged the distribution of savings in the different capital markets. As was the case across the Peninsula (Furió Reference Furió and Berthe1998), the supply and demand for credit varied across social, geographical and sectorial divides. Here we follow Furió (1998, p. 142) in distinguishing three capital markets: one for low-value and short-term credit, which was mostly rural and relatively informal; the moneylending market which supplied merchants or wealthy consumers with short-term credit; the market for loans with infinite maturity or perpetuities. The first market traded loans of small sums at the local level (Furió Reference Furió and Berthe1998, p. 145). This market benefitted from the high levels of trust within the rural communities and, as such, was relatively informal. Consequently, it did not leave a large paper trail in the surviving archives and was left out of this research. The surviving sources, nonetheless, clearly illustrate the working of the remaining two markets: moneylending and the market for perpetuities.

Moneylending took many forms. Letters of exchange were occasionally used to disguise interest-paying loans (Barata Reference Barata1996, p. 688) and traders also borrowed money for a specific venture or a time period and then split the profits at an agreed moment. In the literature this is called a comanda, although the sources use terms like a ganho/ad ganatiam/ad lucrum. Mortgages were also common. Despite the presence of different types of contracts, most of the surviving loans are of the mutuum type. The mutuum (Port. empréstimo) involved borrowing a sum for a short period, at the end of which the borrower had to pay back the sum lent. These loans were secured by the lands of the borrower, which could be seized by the local courts and given to the creditor in case of default. Also, the contracts set fines that were triggered in the case of delay in payment (Barbosa Reference Barbosa and Barbosa1991). As in Valencia (Garcia Marsilla Reference García Marsilla1999, p. 114–115), the mutuum was often used for financing commercial ventures, although it was also used for consumption or to repay debts.

In a legal mutuum, the lender could not demand any compensation for the sum lent except in the case of delay of payment. As stated by Afonso IV in 1349, interest-bearing loans were forbidden «by canon and civil law» (Albuquerque and Nunes Reference Albuquerque and Nunes1988, p. 521). Statutes forbidding usury loans were first issued by the monarchy in 1254–1261, with further restrictions emerging in 1310, 1340 and 1349. The wording of these contracts emphasised that no interest was payable with the common formula gratis et pro amore, a term used throughout Mediterranean Europe to denote that the lender expected no material reward (Felloni Reference Felloni1999, p. 84). The usury doctrine that shaped the financial history of Europe since the first half of the 13th century (Munro Reference Munro2008) became as restrictive in Portugal as in the rest of the continent.

In spite of usury laws, there was a market for interest-bearing loans (Durand Reference Durand1982, p. 268). Otherwise, monasteries and other church institutions would not have been able, as they were (see a 1309 example in Silva Reference Silva2010, p. 354), to secure licenses from their bishops to borrow at interest in times of hardship or when facing unexpected expenses. Even when times were not desperate, lenders and borrowers found ways of circumventing the law and disguising interest. This, as the royal statutes suggest, required some measure of ingenuity. In many allegedly interest-free mutua some sort of compensation for the opportunity cost (i.e. an interest rate) was defined between the two parties and, possibly, recorded by the notary who redacted the contract. The statute of 1349 describes another solution to the prohibition of usury: the borrower declaring to have received a larger sum than he or she actually did and paying back a lower amount. A mutuum could also be disguised as a letter of exchange, as a merchant from Coimbra did for the local canons in 1276 (Durand Reference Durand1982, p. 265). Another common trick involved disguising the contract as a seemingly innocent sale of a commodity (olive oil, wax, wine or grain) with an anticipated payment. The most common device involved rewarding the borrower with the fines established in the contract. In a nominally interest-free loan, the two parties agreed that the borrower would intentionally delay the repayment so that the fines were triggered. These devices are not different from those found in the moneylending market elsewhere in Europe (Garcia Marsilla Reference García Marsilla1999).

In these circumstances, the two parties who consented to the payment of interest entered into some form of collusion and, hence, their rights were not protected by law. There was, nevertheless, an important exception: lending by Jews. Canonical and civil usury laws only forbade lending by Christians. Thus, whenever the lender was a Jew, the interest-paying mutuum was legal and could be enforced by the state.

The market for perpetuities was fundamentally different insofar as it complied with usury laws. Landowners could obtain funds by selling a share of the future revenues generated by their property in exchange for a sum in cash. Because the money was never returned, these contracts conformed to the usury doctrine (Costa Reference Costa1961, pp. 15–16). Some canonists saw through this contract and considered it as a loan, but their position was not strong enough to alter the customs and the law throughout Europe (Schnapper Reference Schnapper1957, pp. 66–69; Furió Reference Furió and Berthe1998, pp. 157–159).

In Portugal, perpetuities are known among historians as censos consignativos, after the name adopted in the authoritative work by Costa (Reference Costa1961). In the 12th century, a censo was simply a «fixed payment». In the middle of the following century, the right to collect a censo from a given land or asset started being sold by means of a simple sales contract signed by the two parties before the notary public (Costa Reference Costa1961, p. 40). This sales contract implied that the selling party acknowledged having received a sum of money for which he owed a perpetual censo that was assigned to a specific property (Costa Reference Costa1961, Appendix). The censo or obligation to pay could be transferred to other properties at the mutual agreement of the two parties, as 14th-century documents confirm (Costa Reference Costa1961, Appendix) and as the 15th-century cases of non-performing censos in Guimarães show (Ferreira Reference Ferreira1989). In fact, in many known contracts, landowners explicitly pledged their properties to honour the annual payment (Costa Reference Costa1961, p. 101). The contract remained nameless until the 15th century, when other terms like compra de censo or compra de foro started to occur (Costa Reference Costa1961, p. 89).Footnote 3

It is important to stress that landed property played a crucial role in the two capital markets surveyed here. In moneylending contracts, land operated as collateral so that the lenders could recover their capital and interest. The perpetuity went a step further insofar as a share of the revenue of the land was owned by the lender. As such, the borrower could not access these two credit markets without land ownership.

The interpretation of the interest rates formed in the capital market, especially in the market for perpetuities, would be incomplete without considering the main alternative available to the owners of financial capital. Potential lenders could also obtain a return on their capital by acquiring a property (agriculture or housing) from which they would collect a rent. In these cases, the ratio of the rental to the purchase price of land can be considered as the rate of return on financial capital (Allen Reference Allen1988; Clark Reference Clark1988, pp. 268–269). The return on this investment is called the implicit interest rate or the rate of return on capital (rK) and can be expressed as the ratio between the rental of a given land (Rl) and its selling price (Pl):

$$rK = \displaystyle{{Rl} \over {Pl}}$$

$$rK = \displaystyle{{Rl} \over {Pl}}$$It is possible to observe an implicit interest rate when owners of capital acquire a property from which they obtain a payment. This happens when buyers become landlords either because they let their property immediately after buying or because the property was already paying a rent when it was bought. Implicit interest rates can also be extracted in other ways. First, when an investor estimates the expected return of his or her investment. In fact, a given individual may set aside, say, 1000 libras (money of account) to buy property which would then generate an income of, say, 100 libras. In this situation the expected rate of return is 10 per cent. This is observable when investors assign the income of their property to meet a future expense, typically a pious individual acquiring lands or houses whose income would meet the cost of religious services for all eternity, as stated in wills or in the obituary lists. Alternatively, we might come across an evaluation of a property based upon the effective rent, which is also equivalent to the expected return.

3. SOURCES AND DATA

This section describes the strategy for gathering the empirical evidence on the capital markets outlined in the previous section and its representativeness. Our data collection efforts had to overcome some archival limitations that we explain here.

This paper is built upon the evidence derived from an entirely new set of 241 interest rates in private contracts in Portugal in the years between 1230 and 1500. The starting point was imposed by the sources employed, as we did not find any interest rates in sources earlier than 1230. The year 1500 was taken as an ending point because the first long-term public debt instruments (the juros) were introduced in that year. The emergence of state-issued perpetuities was a game-changer for the owners of capital, as it granted them access to the large revenue streams of a functional tax state (Henriques Reference Henriques2008, p. 180). The text of the first juros (Costa 1883, p. 121) indicates that these new instruments were designed to crowd out the savings that would otherwise have gone to the private market in the form of censos.

Notarial registers underpin the research on Southern European credit markets, namely in Southern France, Italy, or the Crown of Aragon (see papers in Berthe Reference Berthe1998). Nevertheless, the registers of the Portuguese notaries public did not survive, probably because notarial books were not deposited in public archives. Some original contracts can still be found in the archives of church institutions, which carefully kept or copied the charters attesting their rights over their assets (grants, wills, sales, tenancy contracts). It is among these largely unpublished and poorly-described archival collections that the relevant sources can be found.

Gathering a representative sample of mutuum-type contracts, perpetuities and implicit interest rates poses different problems. Stray mutuum-type contracts are frequently found. The absence of notarial registers did not prevent Robert Durand (Reference Durand1982, p. 266) from finding about 100 charters with mutua and other credit operations for the period 1150–1300 in the area between the Douro and the Tagus. However, no interests were declared in these charters and only a couple contained the necessary data to calculate the rate. The contracts that generated perpetuities include the value and the price of the censo but very few archival catalogues are accurate enough to locate them. The fact that these contracts did not have a precise technical term also contributes to the poor cataloguing of sources.

Observing implicit interest rates is harder and requires a different approach. Censos and loans are contracts and hence can sometimes be found with the help of catalogues and other archival tools, as well as by screening collections of documents, published or otherwise. In order to estimate the implicit interest rates two variables are required: the selling price and the rental. Occasionally, and unpredictably, one document may contain the values for these two variables. However, most times, these can only be found in two different contracts: a sale to the investor and a letting agreement in which the investor lets the acquired property. Given poor cataloguing, it is very unusual to find these two documents. Hence, this information can only be obtained using the method that Christopher Dyer memorably described as «truffle-hunting». This was complemented by the help of some generous colleagues who indicated potential sources and shared documents collected for their own research.Footnote 4

Without any possibility for sampling, the strategy followed was to maximise the quantity of the sources consulted. Given that the research spanned the period 1230–1500, source collections with long spans were chosen. Thus, after screening the most accessible (i.e. published or calendarised) collections, we gave priority to the obituaries from the late-12th to the mid-16th centuries. Within the unpublished sources, we prioritised collections with long-temporal coverage and usable catalogues. These included the Colegiada de Guimarães (CSMOG), several collections kept by the chapter of the diocese of Braga, as well as those calendarised in the online database from the archives of Évora.Footnote 5

As shown in Table 1, maximising the number of collections was essential; three-quarters of the sample came from stand-alone charters, of which most were unpublished.

TABLE 1 THE SOURCES OF THE OBSERVATIONS

Source: Appendix B (online).

Note: «Source types» refers to the original archival type of the document, regardless of whether published or not.

In order to limit selection biases resulting from these priorities we resorted to additional sources. Older sources tend to be published in larger quantity than later ones, which creates an important bias. In contrast, publications of late 14th-century and 15th-century sources are relatively rare. This «convenience sampling» bias was compensated with more archival hours dedicated to collections with late 14th- and 15th-century charters. This proved correct, as some unpublished collections from this period contained 22 contracts, notably the Poor Clares of Porto (CSCP), the cartulary of Nossa Senhora da Piedade de Azeitão (MSNPA, Livro 18°) and the miscellaneous charters of the municipal archive of Porto (AMP, Pergs).

Despite our efforts, the time distribution of the sample is uneven (Figure 1). Roughly three-quarters of all observations fall within the first hundred years of the study.Footnote 6 Nonetheless, given that we prioritised sources with a continuous time coverage, we can be confident that the scarcity of cases collected from the 1360s to the 1420s is not an effect of a selection bias but instead a reflection of a change in the behaviour of the investors at the time.

FIGURE 1 Observations and accumulated frequencies.

In order to minimise the geographical bias favouring the northern regions we consulted more sources from the southern half of the country, namely from the collegiate churches situated in Lisbon and Santarém. This is relevant insofar as the higher land/labour ratios in the south might have had an impact on the interest rates. Thus, the fact that the southern territories account for only 20 per cent of the observations (see Table 2) is not a reflection of any selection bias or convenience sampling.

TABLE 2 GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE OBSERVATIONS

Source: See Appendix B (online).

Notes: Implicit interest rates from the small dioceses of Tuy and Guarda were counted in the adjacent dioceses of Braga and Évora respectively.

The strategy of data-collection ensures that the observations gathered reflect the temporal and spatial parameters of the records of the capital markets. A more complex issue is whether the interest rates collected can be considered market prices. A common criticism of quantitative economic history in the case of pre-statistical ages is that the data are unreliable, because the observed prices are affected by non-economic factors such as coercion, gift-exchanging, privileges or religious rewards (Pastor Reference Pastor De Togneri1999). This criticism is closely related to a major strand of research that regards the concession of credit as essentially another predatory device used by the feudal lords to extract farmers' surpluses (on this strand of research, see Furió Reference Furió and Berthe1998).

These issues can be addressed by looking at the variability of some of the observed interest rates. In a «feudal» setting, governed by privilege and hierarchy, interest rates were affected by the status differences between the parties in the contracts, with the dominant party extracting a higher interest. Conversely, in a competitive market, status differences between the borrower and lender have no real effect on prices. This issue can be tested by contrasting sales of perpetuities in which the buyer, i.e. the owner of capital, is from the clergy but the seller is not (Table 3). The assumption at work here is that the institutional privileges of the clergy conferred them a superior position and, hence, granted them higher returns (Clark Reference Clark1988, p. 270). In order to control for other influences on rates, we focused on the censos agreed in the north in their first century of existence (1261–1361), as they are very numerous and uniform.

TABLE 3 INTEREST RATES OF CENSOS AGREED IN THE NORTH (1263–1361)

Source: See text.

Note: Four censos in which both the creditor and debtor were from the clergy were not considered here and their values (4.0 per cent, 4.3 per cent, 4.4 per cent and 5.9 per cent) would not significantly change the results reported.

Table 3 shows that interest rates charged by the, potentially predatory, clergy are in fact 0.3% lower than those of lay investors. Also, the statistics for the cases in which the estate of the lender is unknown are very similar to those of the laity and of the clergy, another indication that the current sample can be taken as representative. We replicated the same test for the rates of return on capital (Table 4). Although data are less uniform with strongly contrasting median rates, the difference also favours the supposedly inferior laity.

TABLE 4 RETURN ON CAPITAL INTEREST RATES OF CENSOS AGREED IN THE NORTH (1263–1361)

Source: Appendix B (online).

The statistics of the sample allow us to infer that the rates observed in the censos reflect the prices paid in a functioning market. However, we cannot claim that the observations collected for the moneylending market are representative of the going interest rates. The sample is small and its chronological distribution skewed, with over 80 per cent of the observations earlier than 1360 (Figure 1). There are reasons to think that the unobservable or missing interest rates were very different from those gathered here. Whilst the observation of the censos or the implicit interest rates depends on the largely random factors governing the survival of some archives, most of the rates we can observe are from contracts involving Jewish lenders, who could legitimately demand interest (see Section 3). We can only observe these contracts because they resulted in the forfeiture of the borrower's property by a state court. Eventually, the forfeited property passed to a monastery or cathedral and the contract found its way into its archive. This creates a clear selection bias and, as such, the interest rates charged in these contracts with the Jew are not necessarily representative of those involved in the (allegedly) interest-free mutua.

4. THE MONEYLENDING MARKET

The interest rates agreed in the seventeen loans collected provide an entirely new perspective on the Portuguese moneylending market between 1270 and 1410. Table 5 displays the interest rates and other relevant variables for the twelve mutuum-type loans. In order to allow for a comparison, interest rates were annualised.

TABLE 5 INTEREST-BEARING MUTUUM-TYPE LOANS IN PORTUGAL (1270–1410)

Sources: Appendix B (online).

Notes: The values in square brackets were estimated. The linear regression of the spot interest rate (x) on the maturity (y) in the contracts whose duration was known indicated that spot interest rates increased with the maturity (R 2 of 0.8202). Thus, we used the equation of the straight line from this linear regression to estimate the maturity (in months). Prices used for estimating interest and principal in kind are from Henriques and Reis (Reference Henriques and Reis2016). The * in the third column indicates that part of the interest was expressed in kind.

The annualised interest rates for mutuum-type loans were nearly identical. If we exclude the 1381 outlier, we get an average of 33.4 per cent with a standard deviation of 3.6 per cent. This is not an arbitrary value; the 33.3 per cent rate was introduced as a cap for Jewish lenders in 1330 (Cunha and Costa Reference Cunha and Costa2004, doc. 19).Footnote 7 This followed earlier Castilian legislation from 1256 and 1294 and corresponded to the rates prevalent in Castile (see one example in Castán Lanaspa Reference Castán Lanaspa1983, p. 84).Footnote 8

The interest rates in Table 4 appear moderate when compared with other polities such as Austria where the interest rate cap for loans was set at 65 per cent in 1338 (Gilomen Reference Gilomen and Berthe1996, p. 107). Nevertheless, the sample collected does not contain interest rates nearing 10 per cent that were already practiced in financially-advanced countries (Garcia Marsilla Reference García Marsilla1999; Homer and Sylla Reference Homer and Sylla2005, Tables 6 and 7). In Valencia, for instance, the maximum interest rate was set at 1.67 per cent per month in 1241 (Garcia Marsilla Reference García Marsilla1999, p. 354), which equals a rate of 20 per cent per annum.

It is doubtful that the interest rates found in Table 5 are representative of the Portuguese moneylending market during this period. There are reasons to argue that the general level of interest rates in the moneylending market was considerably lower. The average of 33.3 per cent is skewed by the fact that three-quarters of the observable interest rates were agreed with Jewish lenders. As mentioned in the previous section, there is a self-selection bias, as only interest rates charged by Jewish lenders can be known. As suggested by Table 5, as in other European contexts, Jews charged higher interests than their Christian counterparts. Garcia Marsilla gathered a sample of the interest-bearing loans in Valencia and saw that Jews lent in the range of 20–25 per cent, while the interest rates charged by their Christian counterparts oscillated between 7.5 and 17.5 per cent (Garcia Marsilla Reference García Marsilla1999, pp. 40–41).

While the literature suggests that the Jewry played an important role as moneylenders (Barbosa Reference Barbosa and Barbosa1991; Barata Reference Barata1996, pp. 691–692), the numerous gratis et amore contracts published in source collections (for instance, Guimarães Reference Guimarães1889; Lira Reference Lira2001; Saraiva Reference Saraiva2003) do not involve Jewish lenders. The contracts gathered in Table 5 represent the high-risk end of the market rather than the most common type of contract. As the crown upheld the rights of the Jewry, confiscation of collateral was frequent which weakened the landowning and military elites (the borrowers of the mutua in 1301 and 1341 were two knights).Footnote 9 The anti-usury legislation singles out Jewish lending for its devastating effects on the wealth of borrowers who often lost their collateral (Cunha and Costa Reference Cunha and Costa2004: doc. 19), a situation with clear parallels with England (Campbell Reference Campbell2005, pp. 93–95). Mounting complaints about the usury of the Jewish eventually led Afonso IV to forbid credit contracts between Jews and Christians altogether in 1349 (Albuquerque and Nunes Reference Albuquerque and Nunes1988, pp. 518–523).

The unbalanced temporal distribution of our sample might also be misleading. There is some evidence that lower interest rates were common earlier in the 13th century. In that period, the common Portuguese term for usury was onzena, which can be translated as «the eleventh». Considering that in Portugal, as elsewhere in Europe (Aragon and Castile, France, German-speaking lands), interest was commonly expressed as the amount of principal required to acquire one monetary unit per annum, this suggests that moneylenders typically demanded one unit for each eleven units lent, which equates to an interest rate of 9.09 per cent.Footnote 10 Likewise, loans other than the mutua show relatively low spot interest rates (Table 6).

TABLE 6 INTEREST-BEARING LOANS IN PORTUGAL (1267–1410)

Sources: Appendix B (online).

Notes: Interest rates were not annualised when the duration of the loan was unknown.

The stigma of usury weighed heavily on the institutions of the moneylending market and hence affects the sources available to historians. Interest-paying loans appear very expensive. However, there are reasons to think that the interest rates from Table 5 relate to the high-risk end of the market. The evidence gathered in this section is insufficient and too discontinuous to state that Portugal lacked an adequate level of savings or that the institutions stymied the emergence of an effective moneylending market (Barbosa Reference Barbosa and Barbosa1991; Durand Reference Durand1982, p. 271).

5. PERPETUITIES

Perpetuities appeared in Portugal in the middle of the 13th century. The first known contract buying a censo in Portugal dates from 1261 in Braga, with the second one contracted 2 years later in Coimbra. Tellingly, the first known perpetuity is from 1261, the year in which Afonso III swore to respect the monetary constitution that would continue until 1369 (Henriques Reference Henriques2008, pp. 74–76). The period prior to the 1330s saw the creation of most of the censos documented in this research. Sold initially for 5 per cent, perpetuities increased slightly over the following decades reaching 5.9 per cent in the 1330s, as shown in Figure 2. In the 1340s and 1350s, the creation of new censos became rare and, after 1361, they disappeared from the sources for nearly half a century. Perpetuities reappeared in 1410 but with an important difference: eight out of the 17 censos, including the two earliest (1410 and 1429), were not denominated in the country's currency, instead they had to be paid in kind (not in silver or foreign coinage).

FIGURE 2 Observations and average interest rates of censos (1261–1500).

The reason for the absence of perpetuities between 1361 and 1410 and the emergence of interest in kind is not difficult to fathom: monetary instability. The chronology of the disappearance of censos from the sources closely matches the cycle of debasement that started in 1369 and continued until the 1430s (Henriques Reference Henriques2008, p. 72). In the price index built by Henriques and Reis (Reference Henriques and Reis2016) prices rose on average 0.8 per cent per annum during the period 1261–1368, but between 1369 and 1435 annual inflation rates reached 4.5 per cent. In this context, inflation-weary investors avoided censos and those who did not hedged their investment against future debasements by negotiating in kind. The rare observations and noisy rates show a disruption of the market for perpetuities. Figure 3 shows a contrario how important a stable currency was for investment in perpetuities.

FIGURE 3 Observed censos and the intrinsic value of the currency.

6. RETURNS ON CAPITAL (IMPLICIT INTEREST RATES)

The interest rate of perpetuities should be compared with alternative uses of financial capital. As mentioned in Section 2, buying and letting property was another investment option available for the owners of capital in the 1230–1500 period. The observations gathered for these implicit interest rates are plotted in Figure 4. Unsurprisingly, given the findings by Allen (1988, Table 1) and Clark (Reference Clark2005, Figure 1), the long-term trajectory of the implicit interest rate is very similar to that of the perpetuity. The period until the 1360s can be characterised as one of increasing returns, followed by the scarce and noisy observations from the beginning of the 15th century. From the 1460s onwards, returns on capital started to decrease and by 1500 they were at a very similar level to 1250.

FIGURE 4 Observations of implicit interest rates.

Investing in land to collect rents involved higher risks than buying a perpetuity. In the latter the investor owned a nominal, intangible right which was not affected by changes in the rental market or output fluctuations. The censos owned by the Collegiate Church of Guimarães (Ferreira Reference Ferreira1989) resisted the monetary changes and the instability of the late 14th century (war-related destruction of property, dereliction, confiscation, strong debasements and the disruption of church discipline). The state protected the interests of creditors by issuing statutes demanding that censos and other standing payments had to be settled in the silver equivalent of the original nominal amount (Henriques Reference Henriques2008, Figure 21). Thus, the old perpetuities denominated in the obsolete money of account (morabitinos) owned by the collegiate in 1500 still yielded a considerable share of their original silver value (Ferreira Reference Ferreira1989).

In contrast, owning a rent-paying land or house required management, as the owner had to choose the tenants and, crucially, negotiate the terms of the contract. In highly competitive sectors such as wine, the owner was not necessarily an absentee landlord; tenancy contracts often demanded specific products, techniques and improvements from the tenant (Viana Reference Viana1998).

Subtracting the returns from risk-free perpetuities from the returns from capital invested in land provides us with the risk premium. Figure 5 indicates that the returns on investment in land were slightly lower than the risk-free alternative of censos from the first decades after the Reconquista, which ended in 1249, to the 1310s. The second decade of the 14th century, however, saw a steady increase in the premium for investing in property, as the interest rate from perpetuities stagnated while returns on capital increased. From 1369 onwards, the observations are scarcer and the results noisier, probably reflecting the disruption in investment created by the monetary turbulence of the period. The final decades of the 15th century saw a falling risk premium.

FIGURE 5 Perpetuities, implicit interest rates and risk premia (1270–1500).

Table 7 compares the two variables in the old northern territories and in the reconquered lands, leaving aside the noisy and scarce 15th-century observations. There is very little variation within the two territories before the monetary shock of the mid-14th century. Not only are interest rates similar, but the risk premia are also remarkably close.

TABLE 7 GEOGRAPHICAL VARIATION OF THE RISK PREMIUM (1240–1369)

Source: See text.

The lack of regional variation suggests that the Reconquista gave way to the equalisation of the returns on capital across the country, as had happened with labour (Henriques Reference Henriques2015, Figure 3). A likely explanation for the equalisation of the returns on capital is that this factor flowed southwards and, hence, supplied the frontier with adequate levels of capital.

7. INTERNATIONAL COMPARISONS

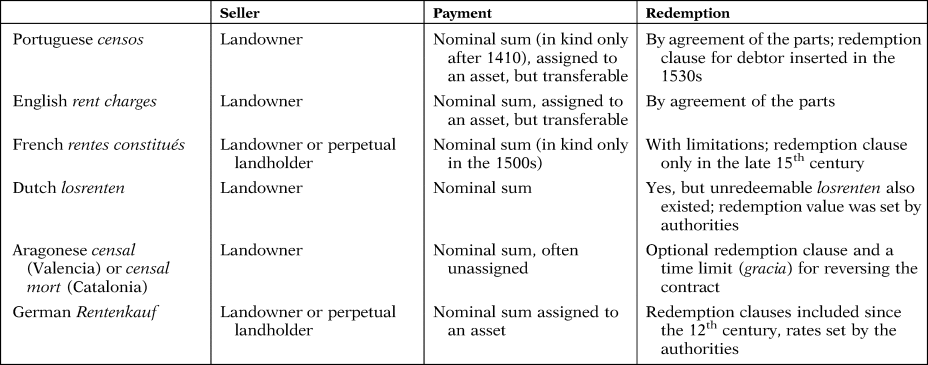

According to a number of authors (Costa Reference Costa1961; Gilomen Reference Gilomen1984, p. 11; Clark Reference Clark1988; Zuijderduijn Reference Zuijderduijn2009), the sale of perpetual fixed payments first appeared in northwestern Europe (Normandy, England, Flanders, Hanseatic towns and Lower Rhine) at the beginning of the 13th century. As it conformed to the usury laws and doctrine, this type of contract later became prevalent in nearly the entire continent (Furió Reference Furió and Berthe1998, pp. 147–148; Zuijderduijn Reference Zuijderduijn2009, p. 11).Footnote 11 Despite changes across time, norms and customs, perpetuities remained recognisable across legal systems.Footnote 12 Pope Callixtus III, in the important bull Regimini Universalis of 1455 (Denzinger Reference Denzinger2015, p. 437), described this institution in a way that was applicable throughout Europe: perpetuities were a fixed nominal (in monete) annual payment (reditus sive census annuos) that had been paid for (emptus) for a price (pretium) in cash (pecunia numerata) and was assigned to property (super bonis). The instances of this contract studied by national historiographies (see Table 8) clearly fit this description.

TABLE 8 PERPETUITIES IN EUROPE (1200–1500)

Sources: Portugal (Costa Reference Costa1961); France (Schnapper Reference Schnapper1957, pp. 42, 61–62); Valencia (Garcia Marsilla Reference García Marsilla1999, p. 301); Low Countries (Zuijderduijn Reference Zuijderduijn2009, pp. 50, 108, 148, 172); England (Clark Reference Clark1988, pp. 269–270; Clark Reference Clark1996, p. 573); Germany (Costa Reference Costa1961, passim; Gilomen Reference Gilomen1984, pp. 105–130).

Note: Aragonese censos constituidos (Valencia) or censals a seques/vif (Catalonia) were not included because they yielded a fixed sum together with two contingent feudal dues (fadiga and lluisme) (Garcia Marsilla Reference García Marsilla1999).

As Table 8 shows, there are only two relevant differences between the various contracts: the assignment and the redemption clause. The former is a moot point, insofar as the Portuguese censo, the Rentenkauf or the rente constituée all included an obligatio bonorum clause and hence the entire patrimony of the seller was liable for the annual payment should the assigned asset not perform (Schnapper Reference Schnapper1957, p. 56; Genestal Reference Génestal1901, doc XVI, doc. XVII; Costa Reference Costa1961, pp. 108, 165–167). The rights of the buyer/creditor were thus protected because they could be extracted from other assets. While the censal mort of Catalonia and Valencia was a personal, inheritable liability that was not assigned to a concrete land or property (Garcia Marsilla Reference García Marsilla1999, p. 307, note 125) in case of default, all the assets owned by the sellers or by their heirs were liable for payment (Garcia Marsilla Reference García Marsilla1999, pp. 307–308). This is not substantially different from its Europeans counterparts because the liability was not limited to a specific asset. Costa (Reference Costa1961, p. 100) mentions a case of Rentenkaufen in Cologne in which the payments were assigned by the seller to his dwelling, which generated no income.

The issue of the redemption clause of the Rentenkaufen and losrenten is more sensitive as it could influence the expectations of the buyers/creditors regarding the yield of their investment. However, this influence was limited. In fact, the rates applicable for redemption were not decided by the parties but by the authorities. For the losrenten, redemption was difficult because the contracts did not mention which rates to apply (Zuiderduijn Reference Zuijderduijn2009, p. 50, note 273). Also, the rates of these redemption clauses were not static and responded to the same market forces that shaped interest rates. The rules for redemption issued by princely and municipal authorities in the Empire and Switzerland show the same long-term decreasing trend as interest rates (see list in Gilomen Reference Gilomen1984, pp. 201–204).

The rates of the censo observed in Portugal can thus be compared with other countries and territories, adding to the work already laid out by Gregory Clark (Reference Clark1988, Table 4). This comparison can now be expanded by including data on Catalonia, Valencia and Holland as well as Portugal (see Table 8 and Figure 6), while abandoning the time- and space-discontinuous series from France.Footnote 13 Also, given that Clark's figures for «Germany» bundled together different areas within the Holy Roman Empire, we chose to select from the wide dataset gathered by Max Neuman (Reference Neumann1865), six series with long-temporal coverages and which represent different economic and institutional contexts: trading cities (Lubeck and Basel), rural areas (the Palatinate countryside) and territories encompassing rural and urban areas (Austria and Saxony) and different jurisdictions (Lower Rhine).

FIGURE 6 Nominal rates in perpetuities in Europe (1200–1500).

An important methodological issue is whether the comparison of the nominal (as opposed to real) interest rates is not misleading for the present purposes. The available price data do not allow us to consistently discount the annual inflation rates for all these territories. There are other good reasons for settling for nominal rates. The first is that, as argued by the literature (Clark Reference Clark1988, p. 268; Chilosi et al. Reference Chilosi, Schulze and Volckart2018, p. 643), 14th- or 15th-century investors did not have the tools to perceive the effects of inflation. Investors knew that prices were volatile but did not necessarily assume that they would increase in the long run (and in some cases they did not). Overall, this was an era of low inflation rates across Europe (Allen Reference Allen2001, Figure 5). Clark (Reference Clark1988, Table 3) remarked that the average annual inflation rate was very low in England (0.25 per cent in 1200–1500). Inflation rates were not very different for 15th-century Valencia, Austria and Holland.Footnote 14 As price inflation was not very high during this period, investors were more likely to focus on the metallic value. If there is an exception, then it is Portugal between 1369 and 1435, when debasement-fuelled inflation reached 4.5 per cent. As signalled (Figure 2), only four perpetuities could be found in this period (in 1410, 1429, 1431 and 1434), of which only one had its interest expressed in currency.

The Portuguese case indicates that the concerns with the silver or gold value of the payment overrode concerns about its purchasing power. This provides a strong argument for the comparability of nominal interest rates for perpetuities; these are only found in settings in which currency kept its metallic content. In periods with high-inflation rates and/or frequent debasements, perpetuities were not sought after by investors who were likely to be alarmed by the loss of value of their interest. The case of Portugal from 1369 to 1435 was mentioned in the previous paragraph. The absence of perpetuities in Castile before the late 15th century (see footnote 15) provides a contrario evidence for this. Unlike her neighbours (Aragon and Portugal), where perpetuities were common, Castile did not benefit from a long period of monetary stability starting in the 13th century. On the contrary, Castilian monetary history experienced many episodes of debasement; from 1265 to 1391 all monarchs debased the coinage at least once and only under the Catholic Kings (1474–1504) did the realm find stability (Radamilans Reference Radamilans2010, pp. 54–55, 62–63, 65). The monetary instability of 14th-century France probably contributed to the «decay» of rentes (Schnapper Reference Schnapper1957, p. 44, note 15), although they did not disappear altogether.

Figure 6 shows Portugal against a European backdrop of falling interest rates. With little variation, the drop in the interest rate was felt across European towns, cities and territories. Rates converged towards the 5 per cent mark, which had been attained by the first censos sold in Portugal in the 1260s.

The low and stable interest rates for perpetuities in Portugal are an intriguing finding in light of the recent literature emphasising the role of the institutional frameworks. For Zuijderduijn (Reference Zuijderduijn2009, pp. 53, 100–101, 165–166, 188), the decrease in interest rates in Holland is explained by the emergence of truly public institutions, free from predatory feudal rulers and driven by a centralised state. On the other hand, Chilosi et al. (Reference Chilosi, Schulze and Volckart2018, p. 666) stress how German cities placed under the same sovereign and operating under similar legal codes sought to enlarge the supply of capital by attracting foreign lenders with protective institutions and low risks. The bellicose Italian city-states did not enjoy these advantages and as such did not benefit from market integration.

The institutional setting provides a meaningful hypothesis for explaining the evolution of interest rates in Holland and the German cities.Footnote 15 However, no such institutional factors can explain Portuguese low-interest rates on perpetuities from the outset in 1260 and their relative stability afterwards. We provided evidence that the market for perpetuities was not distorted by feudal privilege (Table 3) and the advantages of a centralised state were already in place in 1260. Also, as regional variation of interest rates was already small in the early stages (Table 7), there was little scope for market integration. The debasements of the late 14th century did disturb the market for perpetuities but their interest rates did not change by a large margin and by 1451–1500 (5.7 per cent) they were roughly the same as they had been in 1301–1350 (5.6 per cent) (Figure 6). Portugal's low-interest rates were therefore grounded in structural factors that not even a major monetary shock could alter.

As previously mentioned, Epstein (Reference Epstein2002) and others regard factor endowments as the key determinant of interest rates. Under this theory, a sudden mortality such as the Black Death led to considerable increases in the ratio of capital per living person, a situation which amounted to a «free lunch» (Epstein Reference Epstein2002, p. 61) for the survivors. For most of the countries analysed in Figure 6, the half century after the Black Death (1351–1400) saw a decrease in interest rates, including in Holland and imperial lands (with the exception of Saxony), although for Austria, Holland, Lubeck and the Palatinate there is a sustained decrease in interest rates that started before 1348. The post-1348 drop is especially clear for Tuscany, Holland and England, whose rates on perpetuities nosedived after 1350 (see Figure 6). In England, it took a «windfall» like the Plague to increase the amounts of land and capital per head (Campbell Reference Campbell2009, 96), which shows in the sudden descent of interest rates. Likewise, in the Low Countries, drainage works only commenced after the Black Death when farmers finally gained access to cheaper credit (van Bavel and van Zanden Reference van Bavel and van Zanden2004, p. 521). The increase of capital stock per head was also noted in post-1348 Centre-North Italy (Federico and Malanima Reference Federico and Malanima2004, pp. 451 and 455). Conversely, in the Iberian economies (Catalonia, Portugal and Valencia), interest rates remained at similar levels before and after the demographic shock.Footnote 16

Factor endowments appear thus as a credible explanation for the comparatively low level of Portuguese interest rates in the mid-13th century. This does not deny that institutional conditions have a key role; as argued in Sections 2 and 5, the market for perpetuities that emerged in the 1260s was underpinned by courts, laws and rights which protected creditors and property-owners and benefitted from the monetary constitution that commenced in 1261.

The positive relationship between factor endowments and low-interest rates is explained by the features of the 13th- or 14th-century capital markets. As argued in Section 2, the demand side of Portuguese capital markets depended on landed property. The capacity for raising capital rested on the (price or rental) value of the property charged with a perpetuity or used as collateral. Interest rates are correlated with the value of land, as confirmed empirically by Clark (Reference Clark2005, Figure 1) and Allen (Reference Allen1988, Table 1) for England in, respectability, 1170–1860 and 1600–1800.

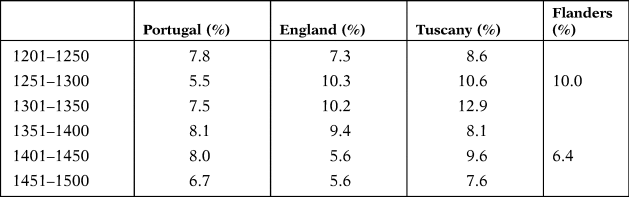

As Table 9 shows, the rental/land price ratios in Portugal in 1301–1350 were considerably lower than in England, Tuscany and Flanders before the Black Death. In these three territories, the rental/land price ratios exceeded 10 per cent before the Plague only to fall considerably afterwards, approaching Portuguese ratios. As shown in Figure 6, interest rates in these countries also fell after 1350. It is likely that, before the epidemic, population pressure resulted in high demand for land and high rentals. Hence, the owners of capital could secure a good return by buying property.

TABLE 9 RENTAL/LAND PRICES, 1201–1500

Source: For Portugal, Appendix B (online); for others, Clark Reference Clark1988 (Tables 3 and 4).

Notes: The following data points are based on two or fewer observations: England 1201–1250 (2), 1351–1400 (2); Tuscany 1451–1500 (1).

Conversely, in Portugal, the implicit interest rates and risk premia (see Figure 5) appear unaffected by the Black Death. Implicit and effective interest rates were moderate and continued to be so because the Plague and the ensuing demographic crisis did not have the effect of dramatically improving factor endowments per capita, as was the case in England or Tuscany.

8. CONCLUSION

Despite being a little-urbanised frontier economy, Portugal benefitted from low interest rates. The market for perpetuities was effective in supplying capital with stable (Figure 2) and comparatively moderate (Figure 6) interest rates across the entire country (Table 7). These main findings indicate that Portuguese high land/labour ratios did not result in scarcity of capital, unlike the archetypal frontier economies of the New World. By 1300, if not earlier (see Table 7), the country had integrated its capital market as it had integrated its labour market (Henriques Reference Henriques2015).

The flat trajectory shown by Portuguese interest rates is relevant for the discussion surrounding the European-wide decrease in interest rates in the 14th and 15th centuries. As seen in the Portuguese mirror, factor endowments were decisive in this process. Tuscany, England and the Low Countries, where the Plague led to the decrease of interest rates and returns on capital, contrast with Portugal (see Section 7), where low returns on capital and land appear as structural features that remained unaffected by the Black Death. The Portuguese case provides a good argument for the thesis pioneered by Epstein (Reference Epstein2002) which argued that the lowering of interest rates was due to the dramatic change in factor endowments induced by the Plague.

The determining role of factor endowments does not exclude the role of institutions. Perpetuities emerged in a context in which institutions were protective of property rights and well-aligned with the interests of the owners of capital. This protection is especially relevant for capital markets in which the existing financial instruments were leveraged on landed property. Most of all, the analysis of Portuguese perpetuities highlights the decisive role of one institution for the development of capital markets: money. The first documented censo is dated 1261, that is the very year in which the monarchy formally abdicated from its own prerogative to debase and accepted strict rules for issuing money. Conversely, no perpetuities were agreed for five decades after the debasements in 1369. In Castile, a frontier economy with a similar legal background, but one in which no such monetary constitution emerged, no perpetuities have yet been found until late in the 15th century, when monetary stability commenced.

The combination of favourable factor endowments with adequate institutional conditions largely explains why Portugal already had low-interest rates in the mid-13th century. This finding strengthens the argument developed by the recent literature that the relatively high living standards enjoyed by the economies born out of the Reconquista were largely due to high per capita factor endowments.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0212610919000326

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I acknowledge the comments, criticisms and suggestions made by the participants at the Lisbon Economic History Seminar (ICS-University of Lisbon), at the 38th APHES Conference in Lisbon and at a seminar at the University of Valencia, maxime those by Antoní Furió. I am grateful for the hard work and recommendations of the editors, in particular Blanca Sánchez Alonso and Nuno Palma, and of the anonymous referees. Special thanks are also due to my colleague Pedro Cosme at Porto for his generous and perceptive advice. I also thank Adolfo Cueto, Hanif Ismail, Diogo Lourenço and Rui Vieira for their recommendations. Finally, I thank Ana Ferreira, Cláudia Silveira, Marta Castelo-Branco, Raquel Oliveira Martins, Mário Farelo, João Fialho, Tiago de Sousa Mendes, Paulo Paixão and Pedro Pinto for kindly sharing the results of their research.