«As so often during the many centuries of the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance, British and Portuguese interests are identical on this vital question [preventing the spread of war to the Iberian Peninsula]» -Winston Churchill, 24 September 1940 (Lochery Reference Lochery2011, p. 88)

«Portugal has maintained during the present war a neutral position which does not imply the breach of any of its international undertakings. On the contrary, her policy has had the consistent concordance of the government of Great Britain, her ally» -Portuguese Legation in Washington DC, 20 May 1941Footnote 1

This paper explores Portuguese neutrality in World War II within the 800-year Anglo-Portuguese alliance, asserting that the financing associated with the balance of payments was an early principal difference between Portuguese economic neutrality and the neutrality of other European countries such as Spain, Sweden, Switzerland or the Vatican. Politically, Portugal was a unique neutral in the Second World War. Its neutrality in the war was not one of traditional impartiality, but rather a clear realist neutrality which from the outset inclined towards the British empire. This suited both parties. The alliance of 1373 was rarely invoked, because Portugal was militarily weak, would add little to the British war effort and would probably have brought Francoist Spain into the war on the side of the Axis.

Mainland Portugal was a neutral adjacent to the Atlantic naval fighting; it survived between Allied navies to the west and Franco's pro-Fascist Spain joined after 1940 by an increasingly aggressive Germany to the east. The Portuguese dictator Antonio Salazar saw fit to maintain peace on the Iberian Peninsula; thus to the belligerents Portugal provided goods, financial aid and assistance. Particularly after German successes in France during the spring of 1940, some aspects of the belligerent-Portuguese relationships were handled in the very even-handed way consistent with strict neutrality. One example is the more equal division of the available quantities of wolfram, a metal needed for Germany's war mechanised effort than had been made before the war. This particular point caused considerable friction with the British and the Americans.Footnote 2 However, as this paper demonstrates, while this was true in such cases as wolfram, it certainly was not with respect to the balance of payments and finance. The Portuguese authorities, while granting the Germans permits to buy, denied them an easy method of payment compared to the Allies, leaving then unable to buy what they wanted.

To be clear, Salazar was not a man of deep Fascist convictions: he had a natural affinity with Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, whom he supported in the Spanish Civil War because relations with the Second Spanish Republic were poor, but he did not to the same extent embrace the idea of Fascism per se. Instead, he gave interviews and in 1937 published a book criticising the Fascist-Nationalist idea (Salazar Reference Salazar1937). However, Salazar's Portugal depended on Francoist Spain to maintain peace over the Iberian Peninsula (Rezola Reference Rezola2008). Franco's victory, which was very much supported by Salazar, ushered in a new era of cooperation between the two countries, including a Portuguese–Spanish Treaty of Friendship and Non-Aggression (Halstead Reference Halstead1990). Maintaining the peace between them (and preventing a German invasion of Portugal through Spain or escalation of British activity) was of the utmost importance to both leaders. Still, mutual suspicion appeared at times, with the Portuguese belief that «Spain might one day want to rule Portugal again».Footnote 3 As historian Maria Inácia Rezola suggests, «The relations between the two countries ended up being developed within the context of a complex management of pressures being exerted upon them by the belligerent parties, resulting in a constant search for an equilibrium that would satisfy both their individual and common interests» (Rezola Reference Rezola2008, p. 3).

However, as the epigraphs above suggest, both the United Kingdom and Portugal continued to speak of each other as an ally in official correspondence until 1940; this extended to correspondence with other parties as well. While this paper is not concerned with semiotics, ‘ally’ is an odd word to use, given that the United Nations alliances were otherwise known as the Allies, and suggests that Salazar was not altogether neutral in his thinking vis-à-vis Britain, even when the war started. So, while Portugal acted with strict neutrality within the Luso-Spanish Treaty of Friendship and worked within the definition set by Hugo Grotius, it still very much viewed itself as linked to the British empire. This was a careful balance to achieve without eroding either the Luso-Spanish alliance or Grotius' view of neutral states, which implied that they should «show themselves impartial to either side in permitting transit, in furnishing supplies to … troops and in not assisting those under siege» (Grotius Reference Grotius1925, p. 783). Grotius' version of neutrality as impartiality remains the most widely understood definition of the concept.

But Portugal was also not in a particularly strong position with respect to its own empire, trade or international relations. Salazar had a significant empire that was largely surrounded by the Allies and dependent on British shipping capacity and shipping controls (Navicerts) which complicated its position (Medlicott Reference Medlicott1952, pp. 509-529). Its empire in East Asia was under threat: Timor was initially occupied by the Allies, but then partially invaded by the Japanese. Equally, Portugal's colonies in Africa were restive and surrounded by British colonies or the British navy. Landing strips in the Azores in the Atlantic were needed by the Allies to maintain air flight traffic between Europe, Latin America and the United States, but controlling them also meant controlling 900 miles of ocean around them as well as the ocean between Newfoundland and the Azores.Footnote 4 Other authors have explored in detail many of these aspects of the history, political economy and military operations at the time; this paper rather offers new conclusions with respect to the financial relationships within the Anglo-British alliance, and in particularly compares them to the Luso-German figures.

Portugal's military weakness and the significant favouritism shown to Britain reveal very clear elements of realist neutrality at work, for the maintenance of the Portuguese empire depended on Britain. Realist neutrality, a concept proffered by Nils Ørvik, evolved as part of the Great War because the increasing relative military strength of the Great Powers and their cult of the offensive made it impossible for most neutrals to resist the belligerents' military power merely by proclaiming themselves neutral (Ørvik Reference Ørvik1971, pp. 13-16). As a result, the neutral countries were forced to re-evaluate the power balance in Europe and adapt as necessary. In this realist power balance, a belligerent's offensive strength over a neutral would have to be calculated with respect to the military, economic and political force it could exert over the neutral and the credibility of its threats; the neutral's power, meanwhile, is derived from its own military, economic and political forces. This realist view differs from the pre-Great War version of traditional neutrality. Traditionally, even with a military imbalance, a declaration of neutrality would typically have been enough to protect a country from aggression. In the case of Portugal, the lack of military power had to be offset by its political, diplomatic and economic influence (Eloranta et al. Reference Eloranta, Golson, Markevich and Wolf2016, p. 265).

Using a combination of Portuguese, American and British archives, this paper argues that because of the long-standing Portuguese–British alliance and Salazar's desire to maintain the Portuguese empire, Portugal and Britain were in more of a symbiotic, mutually dependent relationship than Grotius' strict version of neutrality lays down. In areas where Germans were carefully monitoring Portuguese activity, including the sales of wolfram, Salazar applied a stricter version of neutrality; but in finance, such as the Payments Agreement of 20 November 1940, and other areas, he proved to me more flexible.Footnote 5 This ultimately gave the Allies a strategic advantage in economic relations, starting in 1939.

The present paper provides a new, standardised balance of payment statistics on the Anglo-Portuguese relationship for comparison with German–Portuguese. Building on the existing literature, it finds that the plumbing matters: the systems for payments and the extension of loans to Britain allowed considerably higher levels of economic activity to be maintained between the two empires than in the German–Portuguese relationship. The figures themselves are updated from previous publications to include additional details on trade, intra-government transactions, taxes on wolfram and significantly more detail on services and trade in invisibles. When we compare the Anglo-Portuguese and the German–Portuguese relationship, the figures presented in this paper suggest that a more realist neutrality was applied; they suggest that Portugal was willing to maintain its alliance with Britain and as the epigraphs paper suggest, Salazar was willing to give it this name. Moreover, this paper also shows this was a realist choice: engaging with the British opened access to trade with the Portuguese colonies through the granting of Navicerts.Footnote 6 The figures in this paper suggest this trade access was important to sustaining the Portuguese mainland.

The assistance given by Portugal to cash-strapped Britain included providing credits and loans which amounted to about 23 per cent of Portuguese GDP; these were not provided to the Germans, who had to pay cash or gold for their goods in Portugal. Even the much-criticised Swiss lent the Germans at most only 10.7 per cent of its GDP while the war lasted. The plumbing of this payment system mattered, since these credits gave Britain an advantage over Germany in Portuguese commerce. The higher levels of economic activity presented in the Anglo-Portuguese relationship confirm Portugal as very much a realist neutral.

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

Over the last few years, the economic history of Spanish and Portuguese activities during the Second World War has been hotly debated. The most detailed political-economic study of Spanish–German relations is unquestionably Christian Leitz's Economic Relations between Nazi Germany and Franco's Spain, 1936-1945 (Letiz, 1997). Leitz, building on the theses of Angel Viñas, Rafael García Pérez and Jordi Catalan Vidal, asserts that Germany had a first mover advantage in trading with Spain during the Second World War, from the strong Spanish–German economic cooperation in the Spanish Civil War (Viñas et al. Reference Viñas, Viñuela, Eguidazu, Fernandez Pulgar and Florensa1979, Viñas Reference Viñas1984; Catalan Reference Catalan1992, Reference Catalan1995; Garcia Perez Reference Garcia Perez1994; ). This did not change until Spain's physical isolation from German-occupied territory in late 1944. Caruana and Rockoff (Reference Caruana and Rockoff2003) have examined the effects of oil embargos against Spain and the pre-emptive purchasing of wolfram from that country and from Portugal. They conclude that Allied activities in the pre-purchasing of wolfram were particularly successful, although shipments to Germany continued; the price indices and real trade statistics calculated by Golson (Reference Golson2011) indicate that the Germans suffered from poor terms of merchandise trading with the Spaniards.

In a 2013 article in the Economic History Review, Professor Marcelo de Paiva Abreu provided a first glimpse into Britain's trade and financial relationship with Portugal during the Second World War, including a preliminary view on trade and payments, what the Sterling debts consisted of and why the Portuguese were willing to lend (De Paiva Abreau Reference De Paiva Abreu2013). Abreu demonstrates the political path towards the payment agreements and details the accumulation of the credits. As he notes, the Portuguese contribution to the British war effort was monetarily smaller than the funds provided by others: its financing of £76 million seems tiny, compared to the low estimate of £6 billion borrowed from the countries of the British empire and the United States (Sayers Reference Sayers1956, Appendix III).

Although Abreu's explanation goes into the debts accrued by the British and the mechanisms of payment, it does not sufficiently describe how the debts were generated or the depth of the Anglo-Portuguese relationship: for example, detailed data are taken from only one set of Bank of England documents. The trade in services and British investment in Portugal are largely omitted from his analysis and the trade statistics are not standardised, making it impossible to compare them to the German statistics. He also makes very broad generalisations, including very large unknown or vague statistical categories; these include British invisibles, Allied governments, service categories, total rest of sterling area and others which in 1944 exceeded the entire value of the sterling balance increase (De Paiva Abreu Reference De Paiva Abreu2013, p. 540, Table 1). Moreover, he gives us no comparator in the German–Portuguese relationship, a weakness which requires future research, as he admits in his concluding chapter (De Paiva Abreu Reference De Paiva Abreu2013, p. 552). The present paper completes the above research by presenting the German–Portuguese balance of payments.

TABLE 1. MERCHANDISE TRADE BALANCE PORTUGAL-PORTUGUESE EMPIRE (1938-1945, IN MILLIONS OF POUNDS STERLING)

Source: Valerio (Reference Valerio2005).

In his conclusion, Abreu speculates but ultimately fails to answer its own question of why Salazar provided the British with blank cheque loans: the long-standing Alliance, the Portuguese empire and rationalist neutrality clearly play a role; but none of these is mentioned as decisive and no archival work completes the proffered views. He mentions this empire in the conclusion to the 2003 paper but provides no trade statistics and hardly ever refers to it in the main text to this; the argument remains mere speculation. The simple Portuguese statistics offered in Table 3 of the present paper help to demonstrate more clearly the extent to which the empire was important. Moreover, in his conclusions, Abreu claims that political neutrality was strict until the 1943 concession to the Allies in the Azores, but clearly economic neutrality had broken down well before this date, according to much of the existing diplomatic literature (Stone Reference Stone1994). But, as this paper argues, this occurred in 1940, as soon as the payments and trade systems started to show a bias in favour of Britain.

Other scholars have taken a more political view of Portugal's role in the Second World War. A 1998 paper by Joaquim da Costa Leite carefully depicts the Anglo-Portuguese alliance as a cornerstone of Portuguese foreign policy, but also asserts Salazar was a practical man. Practicality in this sense meant ensuring that the Anglo-Portuguese alliance was stable and avoiding the ideological stereotype so often associated with dictatorship. He wanted to ensure the Allies' awareness that Portugal was free of Fascist influence and Jews were safe there. Costa Leite argues Britain had appreciated the assurances of neutrality given in September 1939 and accepted them as the best for both British and Portuguese interests. Without offering particular support for his views, Leite argues Allied support to Salazar was essential to achieving the underlying goals of the Anglo-Portuguese alliance even if Portugal did not directly join in Britain's war effort (Da Costa Leite Reference Da Costa Leite1998).

On some points, the existing literature suggests that Salazar was at times less willing to compromise with Anglo-American views. The Germans were particularly interested in the wolfram exports from Portugal and Spain. Wolfram (tungsten) is a particularly strong metal which is useful for tanks and other items. The historian Douglas Wheeler argues that despite many Allied requests in 1942-1944, Portugal did not want to restrict its wolfram shipments to the Germans. Consistent with the point made in this paper that Portugal was stricter in some areas than others about its neutrality, Salazar tried to avoid getting drawn into significant diplomatic problems and instead let the two belligerent groups bid up the prices for wolfram on the open market, sometimes via a third party. Naturally, the higher prices thus gained benefited the Portuguese. It was only in May 1943 that the Portuguese agreed to a complete halt to all sales of wolfram, whether to the Allies or the Axis (Wheeler Reference Wheeler1986).

The present paper provides more comprehensive financial and trade data, ultimately demonstrating that the Portuguese motivation was realist, since Portuguese lending was clearly linked to the maintenance of its empire, most of all by the priority given to the retaking of Timor after the Japanese invasion in 1942, when lending accelerated, followed by the lease of the Azores in 1943. As Salazar himself suggested in October 1941, the enemies of Portugal were also the enemies of Britain, not only militarily, but also ideologically.Footnote 7 Negotiations for British shipping capacity and services assistance by Portugal coincided closely with agreements on this very significant lending.

Although Portugal remained neutral per se in areas which were visible, particularly those which affected Iberian affairs, this paper argues that from 1940 in all financial and empire-related decisions it consistently favoured the British position; from this perspective, the belligerent-Portuguese relationship looks realist in the same way as Franco's Spain does, a non-belligerent acting largely in favour of Germany until 1944 (Viñas Reference Viñas1984; Garcia Perez Reference Garcia Perez1994; Leitz Reference Leitz1996; Golson Reference Golson2011). The reasons for Portugal's stance can be traced to a clear political choice on Salazar's part to ensure the preservation of the Portuguese empire, including Angola, Mormugao (Indian Goa), Macau, Mozambique and Timor. This pro-Anglo position ensured the continued political and economic power of Portugal during the war and for some time after it.

2. THE NUMBERS: METHODOLOGY

In presenting the belligerent-Portuguese statistics, a standardised methodology is used which reflects the post-War conventions as indicated in the IMF's Balance of Payments Manual (International Monetary Fund, 1993). Statistics in the War were reported on an ad-hoc basis depending on the reporting organisation. By standardising them, it is possible to compare one case with another to get a better idea of the behaviour of the countries involved; we can then comparatively examine the activities of Britain and Germany to better discuss Portugal's relationship with these two.

For these reports, the IMF conceptual framework for the balance of payment statistics has been simplified and the statistics are divided into five main categories: merchandise/goods, services, current factor income, private capital transfers and finally government capital account transactions. Current account items include trade in goods and services, as well as current factor income. Private transfers and government transfers are both listed under capital account transactions. By standardising the methodology, we can make easy year-by-year and case-by-case comparisons.

Another strength of the present work is that it constructs the statistics using figures from several official sources; both tables below list in full the sources used. The figures for merchandise trade originate from the Portuguese Annual Statistical Books and British government reports on trade; where possible they include illicit merchandise based on American Economic Warfare and British Board of Trade records as well as Bank of England reports.Footnote 8 Services trade is reported separately from merchandise trade.Footnote 9 As far as the available statistics permit, ‘services’ comprise freight and insurance, other transportation expenses, tourism, investment income, government services, British Empire government representation transactions and the category of ‘other remaining services’ which are taken from the Portuguese Annual Statistical books and Bank of England records. Private and government capital transfers based on Bank of England reports and Escudos transactions on behalf of the US, Spanish trade and loan payments to Brazil are all detailed from American, British Board of Trade and Bank of England documents. Government transfers include loans provided, gold and all payments made in foreign currencies. The German–Portuguese statistics originate from the Portuguese trade statistics, available Swiss statistics, existing secondary literature and American and British records. This improves Avreu's statistics on the published balance of payments by giving a more detailed and multifaceted account of the Portuguese transactions with both the British and the Germans; they show how far the British took advantage of their capital borrowing capabilities to pay for Portuguese merchandise and services, and even to pay third parties.

To make the various relationships and statistics comparable, for the sake of understanding more clearly the differences in the relationships, some terms have been standardised. All figures are reported in Pounds Sterling and local currency figures are converted by the official rate for each year. The statistics in this paper are presented from the standpoint of Portugal. For example, a surplus in the capital account of the Anglo-Portuguese relationship reported in Table A1 in the Appendix indicates a transfer of capital from Britain to Portugal.

It should be noted that examining a neutral-belligerent relationship over a balance of payments is subject to substantial constraints, not the least of which is data availability. Since precise totals for non-trade items were at the time considered less important than trade figures, such as those for service transfers, they are often difficult to come by and may be biased. Service statistics were often not recorded except by clearing or payment organisations. In the case of Portugal, the files available provide only patchy answers separately listing expenses and receipts, which have been woven together. The balance of payment figures was constructed in strict order of trustworthiness. At times conflicts between sources were found, usually due to the accuracy of the statistics, the use of different currencies, knowledge of subversive payments or time period conflicts in the reporting process. In all cases, priority was given first to Portugal's national statistics, followed by the belligerent's statistics. Some error terms result, and explanatory notes are provided whenever possible.

3. MECHANISMS OF PAYMENT FAVOURING BRITAIN

This is an area where plumbing is important: the ease with which the British government could generate Portuguese credits allowed the country to borrow significant funds in Portuguese Escudos without any wartime requirement to repay them. The Anglo-Portuguese balance of payment clearing system is demonstrated in Figure 1 (below). The Anglo-Portuguese balance of payments most closely resembles a Monetary Clearing system where any excess balance of payments or payment in monetary terms is cleared between the central banks representing the two trading countries. At point A of Figure 1, a Portuguese buyer imports goods from Britain; in exchange the Portuguese buyer pays a pre-arranged amount in Escudos to the Bank of Portugal (B) and the British seller is paid a similar amount in British Pounds by the Bank of England. In the countervailing trade, a Portuguese seller is paid by the Bank of Portugal (C) while a British buyer pays the Bank of England an equivalent sum in British Pounds.

FIGURE 1 Schematic of Monetary Clearing Scheme.

However, a critical difference after the Anglo-Portuguese Payments Agreement of 20 November 1940 is that these funds now carried a guarantee and required no repayment until after the war when circumstances permitted. Before the war, any excess funds on account resulting from trade, services or capital imbalances were settled through the transfer of balancing sums, which in practice was in gold (G). After the start of the war, the process of clearing the balancing sums at monthly intervals (G) stopped. Instead, the Portuguese government allowed the British to continue adding to their credit balance, which was eventually settled through a long-term payment plan. Additionally, as suggested in step (H), any borrowed Escudos were paid on behalf of the British to third parties, namely, Brazil and Spain, through the Bank of Portugal;Footnote 10 no other neutral country allowed cash payments to third countries on credit during the War (Golson Reference Golson2011, Chapter 5).

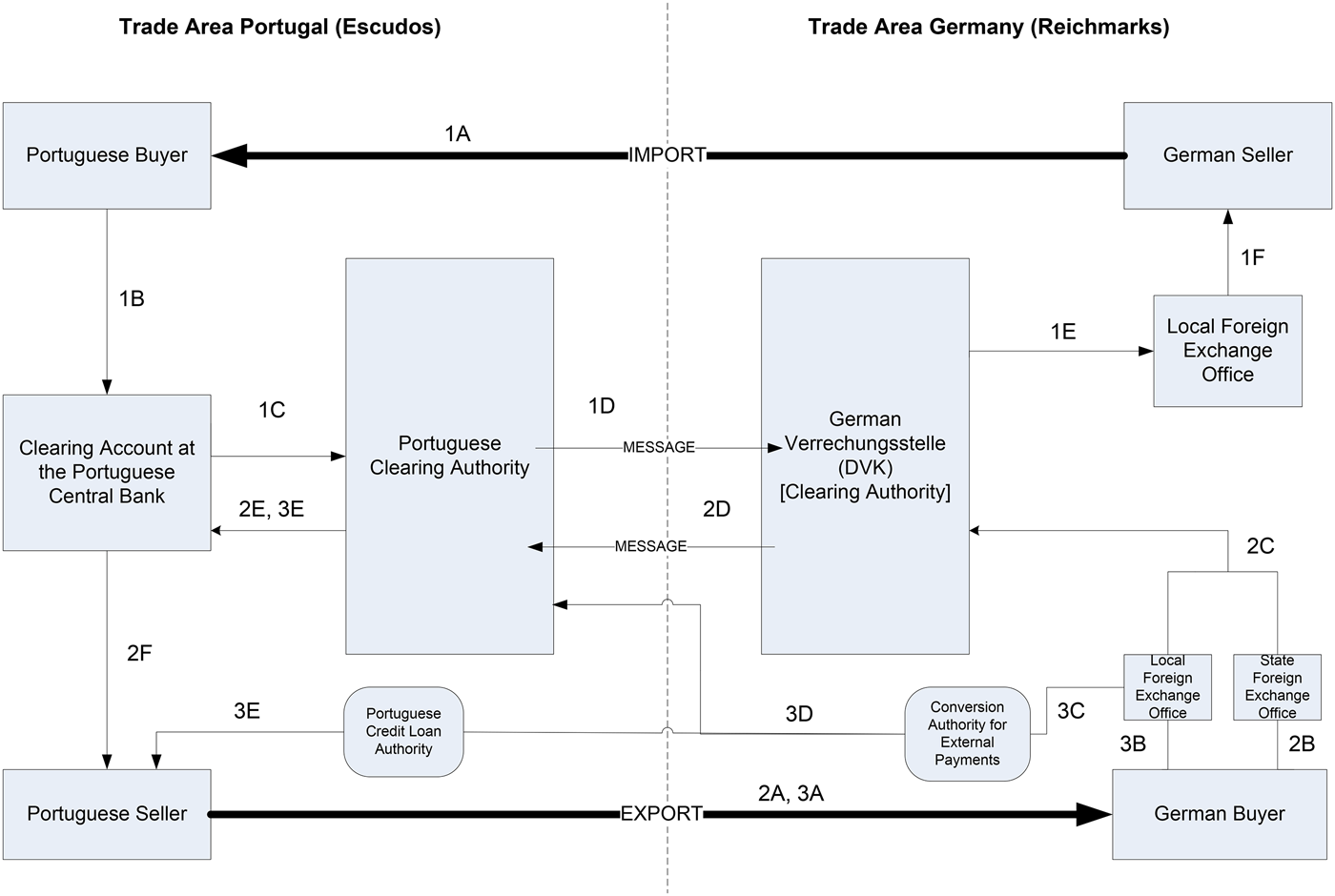

This should be contrasted with the German–Portuguese clearing system based on the 1935 Luso-German Clearing Agreement, which started as a compensation clearing system, by settling the deficit balances in goods and services.Footnote 11 Compensation clearing is a non-cash transfer system which clears deficits or surpluses by means of countervailing goods, services or private transfers; as a rule, no government uses gold flows for this purpose, except in the German–Portuguese case—the Germans started paying in gold in 1943 to maintain their purchases of tungsten (also known as wolfram). The central banks of the two countries typically did not monitor the transactions in such systems; instead, the clearing authorities balanced the trade and paid the buyers and sellers when cash was available. Such a system is chiefly used by a country (such as Germany) which is short of hard currency wherewith to maintain an even balance of payments; it forces trading partners and debtors to accept goods instead of gold or foreign currencies. This helps to maximise exports and minimise imports in an autarky. In doing this, Germany and Portuguese, of course, limited their trade until Germany set aside gold to reconcile the balance of payments.

Figure 2 shows the compensation clearing arrangements in place between Portugal and Germany from 1936-1945.Footnote 12 There are three specific scenarios to note, again describing them from the Portuguese standpoint. The first concerns imports into Portugal: a Portuguese buyer purchases a German product (1A) and pays Escudos to a clearing account at the Bank of Portugal (1B); the Bank of Portugal transfers these funds to the Portuguese Clearing Authority (1C). The Portuguese Clearing Authority credits the account of the DVK, the German Clearing Authority, in Escudos, without sending any funds to Germany (the transfer being accomplished by message in step 1D). The DVK credits the same amount in Reichmarks at the official rate to the Portuguese Clearing Authority's account at the DVK. The DVK then issues a credit to the local foreign exchange office in Germany (1E), which pays the seller according to the pre-authorised terms of the transaction. A Portuguese export to Germany follows a similar pattern in reverse, as denoted by 2A-2E. Each transaction requires approval; under this system it could take anything from a few days to months to get approval for purchases and sales, depending on the importance of the materials required.

FIGURE 2 Schematic of Compensation Clearing Scheme.

The transfer of capital from Germany to Portugal followed a similarly complex path and here, in particular, the plumbing of the system and the pressure of the British blockade were important. As Figure 2 shows, the sale of a security to a German buyer (3A) triggered a capital transfer from Germany, which was paid to the conversion authority for foreign payments (3C) and in turn would pay funds into the account of the Portuguese Clearing Authority. The Clearing Authority would then pass the funds to the clearing account at the Bank of Portugal or directly to the creditor (3E).Footnote 13 In 1943, when the German government was faced with an increasing need for tungsten it undertook to pay gold via Switzerland to cover its balance of payment deficits (Independent Commission of Experts of Switzerland - Second World War 1998; Telo Reference Telo2000, pp. 197-202).Footnote 14 However, because the Portuguese wanted physical delivery of the gold and the Swiss were not in a position to physically transfer much gold to Portugal due to the British blockade, poor Spanish transit facilities and German restrictions on shipping, the Germans could transfer only a limited amount of gold. Swiss and Portuguese attempts to transfer the possession of Swiss gold held in New York, Sweden, Brazil and Argentina ultimately broke down or were blocked by the Allies. Swiss Francs were later substituted, but the Portuguese authorities ultimately demanded gold bullion.Footnote 15 German attempts to sell captured Escudo bonds were also frustrated by Allied intelligence.Footnote 16 Thus, German payments were limited by currency and cash availability. The result of the compensation clearing system was to limit German trade and finance: it provided considerably less capital than the British were allowed to borrow using their financing facilities.

4. THE NUMBERS: ANGLO BLANK CHEQUE

Portuguese lending to Britain from 1939 to 1945 funded 99 per cent of the British balance of payment deficit with Portugal, including some transfers to third parties. This Portuguese lending represented a blank cheque which the British could draw on at any time. In both style and size, it was a wholly un-neutral act in keeping with the Grotius version of strict neutrality: no other country provided such an indefinite facility to a belligerent to cover both capital and current account payments (Golson Reference Golson2011, Ch. 5). In total, Portugal lent Britain £76 million sterling over the course of the war, roughly 23 per cent of annual Portuguese GDP in 1945 or an average of 5.8 per cent per annum over the 4 years in which the debts were accumulated (Maddison Reference Maddison2013). Most neutrals were not willing to provide long-standing credit; the next highest lender, Switzerland, never exceeded approximately 12 per cent of GDP in its lending to Germany; Sweden, Spain and Turkey never exceeded single digits in percentage terms, and most of them required these balances to be cleared by the end of the war (Golson Reference Golson2011).

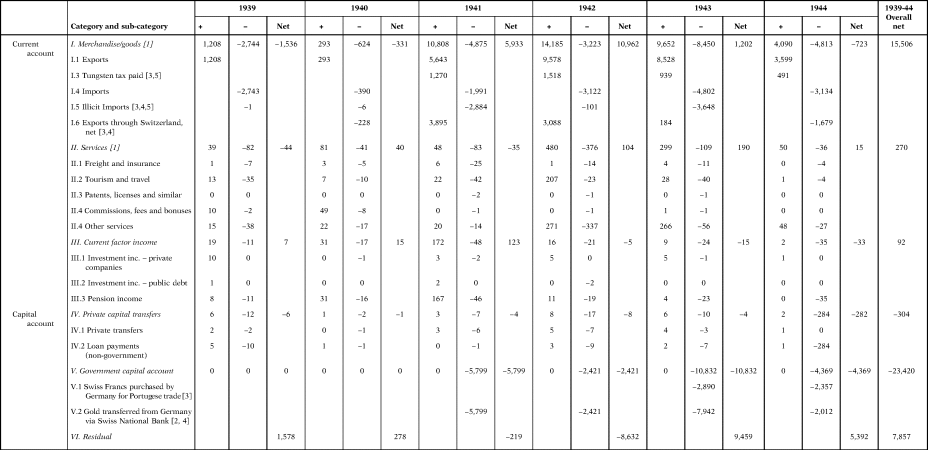

The balance of payment statistics from 1941 to 1944 indicates that Portugal registered sizeable benefits from its merchandise trade with Britain, in particular when compared with those from its trade with Germany.

An overview of the Anglo-Portuguese payment relationship is provided in Table A1 of the Appendix to this paper. The statistics in this section improve on the earlier paper by Professor Abreu by incorporating additional trade, services and trade through third parties to produce more accurate overall balance of payment figures; most importantly, figures which can be compared to Germany's.Footnote 17 As seen in Table A1, four main points should be considered: large increases in merchandise trade surpluses during the peak of pre-emptive purchasing in 1941-1943; increased surpluses for services over the course of the war, related to Portuguese protecting power working on behalf of the British government; a higher volume of current factor income, but without any additional surpluses over the 1939 levels, mostly related to changes to corporate income and remittances; and finally, increased surpluses for Portugal from private capital transfers, above all, British investment in the Portuguese industry. While the first is evident in the German relationship, the remaining three are unique to the Anglo-Portuguese relationship and reinforce the depth of the connection between the two countries.

During the war, Portuguese exports increased significantly while imports lessened; this resulted in a substantial balance of payment surpluses for Portugal. By the end of the first year of trade, Portuguese supplies of cork and diamonds alone exhausted Britain's fund of Escudos. Many of these changes were due to the pre-emptive purchasing of tungsten and other strategic commodities. From 1939, levels of imports and exports rose to ~£12 million and small surpluses of about £680,000 were recorded. As export earnings reached nearly £19.1 million, imports at their lowest point in 1942 declined to £4.5 million. Part of the £19.1 million was regular export earnings of £15.3 million, plus sums of £2.0 million for goods purchased and not exported, as well as £1.8 million, tax paid, for tungsten.Footnote 18 These purchased but retained goods were part of a pattern related to the pre-emptive purchasing of strategic commodities to keep them away from the Germans.

Goods purchased and retained in Portugal were held as part of the American and British programme of buying strategic materials, led by two government-owned commercial companies. Both countries, acting sometimes jointly, sometimes separately, authorised government-owned companies to pre-emptively buy strategic commodities. The goods acquired in Portugal included tungsten, animal hides, food, petroleum and pharmaceuticals. Many of the goods were exported, except for £2 million in 1942-43 and £1.8 million in 1944. A further £1.6 million was spent by the United States Commercial Company but paid for by the UK Commercial Company in 1941.Footnote 19 Total pre-emptive purchasing which was not exported over the period, including purchases for the USCC, amounted to £8.6 million or 9.7 per cent of the 1944 clearing balance.

Export taxes on tungsten were imposed on purchases by Portugal from 1941 onwards. These taxes were part of the system imposed by Portugal to control the allocation of tungsten and the profit from it. The production which was not owned by companies representing the British and German governments was split 50/50. This increased the price of tungsten, but not to the extent that it increased in the Spanish case.Footnote 20 As seen in Table A1 (Appendix), total tungsten taxes paid over the 1941-44 period were £8.6 million or more than 11.3 per cent of the 1945 debt.Footnote 21

Looking at the merchandise trade figures without the three additional wartime-related export items, there are still notable changes in the import–export balance, all in Portugal's favour. The general import and export balance increased substantially. From the import and export of ~£12 million and the small surpluses of about £680,000 previously mentioned, general merchandise trade in exports in 1941 increased to £14.6 million and in imports to £6.2 million. Surpluses grew to £8.4 million in the same year. By 1942 the general merchandise trade surplus had increased to £15.3 million with imports of £4.5 million, a surplus of £10.8 million in Portugal's favour. This represented the peak of regularised Portuguese merchandise trade. From the peak in 1942, the following years saw only £6.5 million as the 1943 surplus and £4.9 million in 1944 but these are still substantially higher trade and surplus values than before the war. Excluding the special items mentioned previously, the total of Portuguese earnings from merchandise trade amount to £32.2 million or 42.3 per cent of the 1944 clearing balance. Although in total this merchandise trade makes up a substantial proportion of the balances accumulated by the Portuguese, services, factor income and private transfers also made very important contributions to the credit balance, which should not be overlooked.Footnote 22

Services were a large source of net earnings for the Portuguese government. The term ‘services’ includes freight, insurance, patents, commissions and perhaps most important, government service transactions. Apart from the government services, few changes were made during the course of the war. Tourism was up in 1940, no doubt from spies setting up operations in Portugal and Europeans using surplus Sterling in Portugal to move to the United Kingdom or fly to the United States.Footnote 23

The largest gains are registered in the various levels of government expenditure; included in particular is work as a protecting power on behalf of the belligerents. Although Switzerland is famous as the protecting power during the Second World, providing links to POWs and protecting foreign embassies and interests in hostile countries, it lacked the international presence and shipping capabilities necessary to transport goods. Portugal worked closely with the Swiss and the International Red Cross to maintain these links during the war; for example, food parcels for British troops in Asia were routed through the Portuguese colonies, including Mozambique, Goa (India) and Macau, which for a time was the only neutral port in China.Footnote 24 These Portuguese government services are recorded separately as UK government transactions and British Empire government transactions in the balance of payment statistics presented in Table A1 (Appendix). Britain's government transactions increased steadily from a low of £100,000 in 1939 to a substantial £1.8 million in 1944, reflecting increased work by the Portuguese as a protecting power. Work on behalf of the countries of the British Empire also enhanced Portuguese service earnings—by £600,000 to £800,000 each year between 1941 and 1944.Footnote 25

This protecting power work ultimately attracted net earnings from services. Total earnings from services over the period amount to £10.0 million or 13.3 per cent of the 1944 clearing balance. As seen in Table A1, from a small surplus balance of £356,000 in 1939, the statistics indicate that service earnings increased to a maximum of £3.56 million in 1944. It is noteworthy that the increase was not evenly paced, despite the increased British expenditure on protecting power services.Footnote 26 Increases in other services, such as British shipping on behalf of Portugal (including journeys between ports in the Portuguese empire and the transport of Portuguese troops), reduced the earnings in 1942 and 1943. Other service costs increased from a pre-war figure of just under £1 million to over £2.7 million in 1943.Footnote 27 The greater part of this increase over pre-war levels is believed to be related to these shipping costs.

Current factor income was relatively constant throughout the war, with a total surplus of roughly £2 million for Portugal across the five years. The increased cash flow from British companies, including many mines owned by the United Kingdom and later the UK Commercial Company, bear witness to large increases in profits and hence remittances. From stable levels of nearly £160,000 in 1939-40, the sums increase to £720,000 in 1941 and are maintained at a level of around £480,000-£550,000 for the rest of the war. These profits reflect the high prices for tungsten and for tin, which were obtained from British owned mines and more generally the high levels of British investment in mining (discussed under ‘capital’ in the next paragraph).Footnote 28 The Portuguese also received interest on their loan to the British as part of a deal between the two countries. This is included in the current factor income calculations, entered as a loan increase of £200,000 in 1943 and £600,000 in 1944.

Because of the Portuguese loan, private capital transfers were less restricted in this case than in those of other neutral countries. Typically, private transfers were not allowed between neutrals and belligerents (Golson Reference Golson2011, Chapter 5). But to Britain they continued, because they were not limited by the available currency and therefore were almost universally approved. This may be compared to several periods when it was impossible to transfer funds from Britain to Switzerland or Spain, due to a shortage of domestic currency and a refusal to settle balances in gold. Overall, Portugal booked net transfers in its favour of £13.0 million or 17.1 per cent of the 1944 clearing balance. Approximately £5.8 million of these transfers represented UK government capital investment in the Portuguese industry, in particular the mining industry. With this investment, the British government sought to gain control over the Portuguese mining industry through buying additional mines, and also by increasing the output from current mines of materials held to be vital for the British war effort. Examples of equipment and investment include: buildings, schools, railways, electrical plant improvements, motor power, carts for the transport of material, land for water, casting equipment and the building of warehouse space, in particular for the mining industry.Footnote 29 Additional payments of some £12.2 million were net transfers from the Sterling area. They are shown in the archival records without any significant additional information.

Finally, the government capital account shows other minor activities amongst the large increases in clearing indebtedness from late 1940 through 1944. Adding to the lack of clear neutrality and unusually for a neutral country during the Second World War, Portugal repaid debts to third parties on behalf of the British, as recorded in the government capital account. These included small payments to the Spanish government for trade and also a large payment to the Brazilian government for a UK government loan which had been denominated in Escudos. To clear its trade balances with Spain in 1942 and 1943, Britain used the Portuguese clearing facility to purchase Escudos on credit. Although the amounts were small, one only £61,000 and the other £33,000, the payments are symbolically important, because they represent one of only two cases in which payments were made by one neutral to another on behalf of a belligerent.Footnote 30 The other case, as outlined below since it was Portugal that received the payments, was Switzerland, which provided Germany with credit and accepted German gold while making payments to third parties. After the war, the Swiss were challenged about these, because much of the gold paid by Germany to Switzerland for these transactions was, in fact, looted; the credits obtained by the Germans from the Swiss were also not fully repaid (Slany Reference Slany1997, App. 2). In addition to the Swiss parallel of paying for trade, the Portuguese also repaid in full an outstanding British loan of £2 million drawn in Brazil and repayable in Escudos. This loan was repaid in 1944 from Portuguese funds and added to the British balance to be repaid. In this way, Salazar was not only providing blank cheques for debts in Portugal, but also for British debts elsewhere.Footnote 31

This is very unusual and demonstrates the depth of the Anglo-Portuguese alliance. Other neutrals, notably, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland, required the British to pay their clearing debts in gold at regular monthly or other intervals (Golson Reference Golson2011, Ch. 5). The Germans, despite their compensation clearing agreement with Portugal, had to pay their Portuguese debts in Swiss Francs and in gold sent via Switzerland. Portugal would not accept any other form of payment. For the purposes of comparison, when payment was made in gold, the British prioritised and rationed their spending (Sayers Reference Sayers1956, pp. 439-460). The Germans had an even greater shortage of gold and therefore the friction over payments would have been even more intense. It is little wonder, therefore, that Britain's financial relationship with Portugal was deeper and more comprehensive than with the other neutrals. Britain's ability to borrow on credit and the long-standing Anglo-Portuguese political relationship were enough to ensure it.

Not even the United States was provided with such credit; it too had to scrounge for currency in Portugal. Salazar's pro-British economic policies did not generally extend to the Americans or the other Allies. The Portuguese government required payment in dollars for all US balance of payment deficits. Some funds were also provided via special letters of credit and lending to the US in Portugal. However, there were limits to what the Portuguese government would accept and in 1942, for example, unusual tactics were employed. These include acquiring 4 million Escudos (roughly £250,000) from the Portuguese–American Tin Company, reimbursing the parent office in the United States in dollars, while obtaining another 10 million Escudos (roughly £575,000) from the War Department and 5 million from the sale of excess tin held in Portugal. Further sums of £475,000 and £160,000 were paid by the British to the Americans in 1943 and 1944, respectively, in order to satisfy US Escudo debts in other countries and be exchanged for credits against British loans in other countries. These moves to raise cash to support US activities in Portugal remain in stark contrast to the British experience.Footnote 32

5. THE NUMBERS: GERMAN PARSIMONY

In contrast with the British case, Germany had to pay for its Portuguese goods either in countervailing trade or in cash. Based on the 1935 Luso-German Clearing Agreement, Portugal would not directly accept German Reichmarks. As previously suggested, this system guaranteed that the value of one country's exports was balanced by countervailing imports.Footnote 33 Since wartime arrangements meant that Portugal would not directly accept German gold, payments for German clearing deficits in 1941-44 were made via the Swiss National Bank, in gold or Swiss Francs that the Portuguese would accept. British transfers were thus much less severely limited than German transfers (Telo Reference Telo2000).

As seen in Table A2 in the Appendix, there was a spike in payments in 1943 to cover accumulated debit balances in 1942, but generally the Germans kept pace with outstanding balances, no doubt to maintain access to Portuguese markets.Footnote 34 This transfer mechanism was not unusual per se, since neutral countries, including Sweden and Spain, also accepted gold for this purpose and the use of the Swiss bank ensured that the German monies would be considered clean and would not be subject to Allied sanctions, even though they had been obtained by looting (Slany Reference Slany1997; Golson Reference Golson2011). Nonetheless, the British had an unusual advantage, since they were given credit while the Germans were made to pay in gold.

This payment situation also severely restricted German private capital transfers, current factor income and its services balances with Portugal. Germany's economic relationship with Portugal was less complex on these points than it had been before the war. As seen in Table A2, the volume of capital transfers from the two countries was one-hundredth that in the Anglo-Portuguese relationship and in fact, due to strict German transfer controls to Portugal, resulted in net outflows from Portugal to Germany of roughly £304,000. The volumes of current factor income were also significantly restrained, with almost no German investment in the Portuguese industry, earnings from industry to remit or pre-existing debts which required payment. The transfers were one-thirtieth of the Anglo-Portuguese current factor volume, the cash flow was small and again, they earned Portugal only a paltry £92,000 compared to over £2.1 million in the British case. The peak year for current factor income earnings was 1941, when considerable pension earnings were transferred out of Germany to Portugal.

German-Portuguese services were also quite small in relation to the services for Britain. Portugal served on behalf of Britain as a protecting power and was deeply integrated into the Allied shipping, resulting in net earnings of nearly £10 million.Footnote 35 By contrast, the Germans used few Portuguese services, relying in this region on Spain's services for its protecting power representation and shipping. As seen in Table A2 (Appendix), the main German expenditure in Portuguese services was for tourism and travel, in particular in 1942, but also in 1941 and 1943. But even then, it is important to note that the Portuguese spent more in Germany in 1941 and 1943. This travel was no doubt war-related, but no other information about it exists. Whatever it entailed, the total Portuguese service earnings in its German connection amounted to £270,000, or about one-fortieth of the Anglo-British relationship.

Most of the German–Portuguese financial relationship was focused on merchandise trade because this was an area where Germany competed with the Allies for raw materials and resources. It yielded Portugal net earnings of some £15.5 million. There was a sizeable expansion in the German–Portuguese trade after an initial decline caused by a lack of access and the Allied blockade in 1940. Increased trade in tungsten from 1941-1944, in particular, and the collection of export taxes led to the accumulation of large surpluses on the part of Portugal. The total tungsten tax collected by the Portuguese amounted to £3.7 million alone. Portuguese net illicit exports to Germany which were shipped through Switzerland, including metals and third-country items, totalled some £5.2 million in favour of Portugal. Additional illicit imports, largely through Spain, amounted to a £6.6 million cost for Portugal. Direct trade between Portugal and Germany over the course of the war earned Portugal a net £12.7 million.Footnote 36 Although Table A2 (Appendix) includes an error term, these German figures are still constrained. The lack of credit clearly limited German resources and forced Germany to focus on the purchase of tungsten above all other considerations (Telo Reference Telo2000).

6. WHAT MAKES THE ANGLO-PORTUGUESE FINANCIAL RELATIONSHIP UNIQUE?

The statistics suggest that Portugal behaved more like a country in the British Empire than a neutral country. In the light of the German financial statistics, the depth of the 800-year Anglo-Portuguese relationship is evident, with higher levels of trade, services, factor income and capital transfers. The merchandise trade surpluses greatly increased at the peak of the Allies' pre-emptive purchasing; Germany could not fairly compete with Anglo-American pre-emptive purchasing operations because of a severe shortage of available Escudos.Footnote 37

As demonstrated in Table A1 (Appendix), Britain had a close service relationship with Portugal, providing Salazar with shipping, but was dependent on Portugal for protecting power services and services to its prisoners of war, particularly in East Asia. There was a deeper level of British corporate investment in Portugal, with the remittances of profits recorded in current factor income and private capital transfers showing increased British investment.Footnote 38 But these show only part of the symbiotic relationship which existed between Britain and Portugal. The Portuguese could have behaved like other neutrals, and indeed as they themselves behaved towards the Germans, simply by requiring Britain to pay for its goods and services in gold. This obviously would have diminished the close relationship between the two countries, but certainly would not have ended it. So why did Salazar offer Britain a blank cheque? The answer returns to the location and vulnerability of the Portuguese empire, the long-standing Anglo-Portuguese alliance and the domestic position of Salazar.

The Portuguese Minster of the Colonies explained how the Portuguese government viewed the mainland's economic prosperity as directly linked to the continued existence of Portugal as an independent nation in possession of a large colonial empire:

«Portugal was a very poor country industrially and could not possibly hope to compete with countries so magnificently equipped as Great Britain, France, Germany, Belgium and even Holland. It was only in the preferences that Portugal enjoyed in her old Portuguese empire that she could at present eke out a difficult existence … and any loss of these privileges would bring about the ruin of the people of Portugal. It is for this reason that there exists this deep Portuguese anxiety as regards her Colonial empire».Footnote 39

As this quotation suggests, the maintenance of the empire was a premier concern of Salazar; the threat was multifaceted and the survival of his empire would have been very difficult without British cooperation (Newitt Reference Newitt and Byfield2015). The Portuguese Ambassador in London, Dr Monteiro, commented, «he attaches the greatest important first to the alliance and secondly to the guarantee of the future of the Portuguese Colonial empire …» clearly linking the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance and the empire.Footnote 40

After the initial outbreak of war, the Anglo-Portuguese relationship suffered friction over reductions in trade and the application of a blockade against Portugal and her colonies. The British required Navicerts to move goods by the ocean and placed restrictions on their trade with the Portuguese empire. Although the system had been designed to prevent supplies of goods from reaching the Axis shipped via neutrals, Navicerts caused Portugal a number of problems in moving goods between neutral ports, including those on the Portuguese mainland. It also dramatically reduced the amount of shipping available to Portugal, a service that Britain had traditionally supplied.Footnote 41 Many of the Portuguese colonies were surrounded by British interests—Goa surrounded by British India, Mozambique by Rhodesia and South Africa and Angola next to South Africa—and therefore were dependent on Britain for continued military and economic security. The British could easily have seised or starved these territories. Each one of Salazar's fears was expressed to both the British and American officials.Footnote 42

Additionally, the Portuguese mainland still needed raw materials from her colonies to continue her own manufacturing economy (Newitt Reference Newitt and Byfield2015, pp. 219-222). With belligerent-Portuguese trade shrinking in volume, the Portuguese economy increasingly relied on the country's colonies to provide scarce raw materials during the war and to produce goods for export; but the country had long depended on Allied controlled shipping for the transportation of up to 60 per cent of these goods (De Paiva Abreu Reference De Paiva Abreu2013, p. 553). Table 1 shows the increased dependence on the colonies for merchandise goods: volume more than doubles over the course of the war and with increasing negative trade balances (showing the volume of mainland Portugal absorbed goods); in the context of total imports, there is a notable increased dependence on imports from 1941. With the British priority now given to war transportation, Portugal's economy was particularly vulnerable to a change in British tactics in this regard.Footnote 43 Salazar was keenly aware of this situation and negotiated with the British for additional supporting shipping capacity. These shipping capacity agreements generally existed alongside the war trade agreements and loan negotiations, linking negotiations over the various items.Footnote 44

With regard to shipping, two important changes occurred over time, both representing British assistance to Portugal; these allowed the country to maintain its empire. The first was to make new shipping arrangements in place of the pre-war ones. Based on records in Allied intelligence reports, before the war, the Portuguese had carried materials from the US and UK to Portugal and British ships had carried trade to and from the Portuguese empire. By 1941, cargo from Allied countries, such as North American wheat and British coal, which would have normally been carried on Portuguese ships in the pre-war period, was instead being carried by British ships. Other shortages were mitigated by sourcing materials in the empire from the surrounding British colonies rather than directly from Portugal or Britain. These agreements were considered extra-ordinary provisions for Portugal and freed nearly 115,000 tons of shipping per month, equivalent to almost the entire Portuguese merchant marine. This allowed Portugal to devote its shipping resources to maintaining links with her empire.Footnote 45

Consideration of the timing is important: as his empire weakened, Salazar turned more solidly towards the Allies. Following the Japanese invasion of Timor in February 1942, he realised that the British were needed to ensure that his empire did not collapse. The correspondence indicates that he was careful to hedge his position. In particular, after the initial occupation of Timor in January 1942 by Australian and Dutch troops, Salazar made a point of pressing the Allies firmly and threatening to deny them access to Portuguese resources; but no action was taken.Footnote 46 However, after the Japanese landings in Timor, Salazar's mind turned to the reoccupation of Timor and ways of preventing the total loss of his empire. He made a speech for domestic consumption, linking the preservation of the empire with not abandoning Timor.Footnote 47 He placed a number of requests to use British shipping, transportation and logistical assistance, which were also recorded with the Americans, to transport Portuguese troops for invasion and reoccupation of Timor.Footnote 48

The British contribution was to directly provide shipping capacity for Portugal, set aside for moving goods between parts of the Portuguese empire and the home country. As Salazar was heard to say in October 1943, at the implementation of the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance, «British vessels continue to arrive in the Tagus with supplies for the Portuguese population, and their usefulness in the influencing of Portuguese policy is probably no less than it was in the XVIII century. But the cargoes of these vessels today are predominately ones that come from our country and not from England».Footnote 49 At this time, Salazar allowed the British and Allies to use the Azores, later extending the 1943 British agreement to include American use.Footnote 50 In exchange, the total shipping capacity provided by the British to Portugal amounted to a further 25 per cent of available Portuguese capacity, totalling roughly 30,000 tons of shipping per month. In addition, the United States increasingly sent direct supplies of fuel and coal to Portuguese possessions (except those in India), further reducing the required shipping capacity and ensuring their economic survival. The Allied shipping was vital to maintaining Portuguese control over these possessions. Had Portugal not had British assistance or joined the war on the side of the Axis, Salazar acknowledged to British officials, he knew that he would have lost part of Portugal's empire.Footnote 51

7. CONCLUSIONS

This paper has reviewed Portuguese financial and clearing arrangements with the United Kingdom and Germany during the Second World War. It has provided a new standardised balance of payment statistics which are in line with existing convention and cross-comparable. Differentiating itself from the existing literature by asserting that Portugal was not strictly neutral with respect to financial affairs from the date of its signature on the 1940 Anglo-Portuguese clearing agreement, this paper also demonstrates that the Portuguese were willing during the war to lend the British in total over a quarter of a year's GDP. Its unlimited lending, or blank cheque, allowed Britain to engage in trade, services and even pay third-party debts with Escudos; by contrast the Germans did not have access to such funds. Although allocated a fair share of commodities in an adherence to the rules of strict neutrality, the Germans were unable to pay for them due to a lack of corresponding goods, gold or Swiss Francs, the only commodities and currencies acceptable to Portuguese for German debts. As a result, British merchandise and services trade as well as investment in Portugal were stronger than Germany's and remained so throughout the war.

An explanation for this can be found in the British role in maintaining the Portuguese empire. According to the statistics and qualitative evidence presented in this study, Salazar would certainly have lost control of his empire, suffered serious shipping problems and been substantially weakened at home without British assistance, particularly as the war went on. British shipping was needed to maintain the Portuguese empire and supply the Portuguese mainland with goods. After 1942, threats against the Portuguese empire can be clearly linked to Salazar's improving cooperation with the British and greater willingness to provide loans.

As demonstrated by the clearing agreements, financial arrangements and need to maintain her empire, Portugal was a unique neutral in the Second World War: one which balanced an 800-year alliance against threats from Germany and a desire to maintain peace on the Iberian Peninsula. This worked well for both parties. As Salazar pointed out to the British Ambassador in Lisbon in 1943, Sir Richard Campbell says «[the British] must not underestimate the value of the Alliance up to date … the amount of wolfram that had gone to Germany and certain other matters of which we [the Allies] complained, had been the price that we had to pay for immeasurably greater benefits. Even so he would remind me that he had nearly always contrived a formula which had given us [Britain] a favourable position».Footnote 52 It was, of course, a favourable position for Portugal as well.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is grateful for the advice of two anonymous referees, Professor Mark Harrison, Dr Peter Howlett, Dr Nuno Palma, Dr Peter Sims and Dr Tamas Vonyo who commented on earlier drafts of this paper. He is also grateful for research support during this long running project from the University of Surrey, the Warwick Economics Department, the London School of Economics, the Economic History Society through an EHS Anniversary Fellowship (2011-2012) and from the Swiss Government while a Junior Research Fellow at Oxford University (2012-2016).

SOURCES and OFFICIAL PUBLICATIONS:

Anuário Estatístico, Portugal Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 1939-1945.

Ministério dos Negócios Estrangeiros, Dez anos de política externa: A nação portuguesa e a Segunda Guerra Mundial (1974), volumes IV-XIV.

United States Department of State, Allied Relations and Negotiations with Portugal.

Bank of England Archive (BoE).

OV6/99, Trade and Payments Agreement between the United Kingdom and Sweden.

EID3/16, records on relations with Bank of Portugal, 1944-1945.

International Monetary Fund, Balance of Payments Manual (International Monetary Fund, 1993).

National Archives, United Kingdom, Kew, London, UK (as TNA).

FO371/21 Foreign office files related to Portuguese affairs.

T160/1273 Files related to Portuguese trade.

T160/1274 Files related to Portuguese trade.

T160/1275 Files related to Portuguese trade.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland, USA (as NARA).

RG84/UD3162/34, records related to wolfram purchasing.

RG84/UD3127/5, Anglo-Portuguese negotiations and agreements.

RG84/UD3127/70, files on the Anglo-Portuguese alliance.

RG84/3126/58, Portuguese relations.

RG84/3126/80, Portuguese relations.

RG84/3134/1, Azores agreements.

RG234/16/19, Report on preclusive operations.

Appendix

TABLE A1. Portugal-United Kingdom (includes Sterling Area) (in thousands of Sterling Pounds)

TABLE B2. Portugal-Germany (in thousands of Sterling Pounds)