In 2013, the Gezi Park protests created a wave of optimism in Istanbul – until it was brutally suppressed by the government. Although the ephemeral movement ended without having achieved its immediate goals, it continues to have ripple effects on the public culture of Istanbul. The ruling party, for example, has emulated the forms and formats of performance that emerged during the protests in order to mobilize its own support base. In a post-Gezi Istanbul, however, the occupation of public spaces in protest of the government has become nearly impossible, rendering alternative artistic and activist practices all the more important.

In this paper, we highlight the periphery of the city as a new site of activism as opposed to formal public spaces (e.g., central squares, parks, streets) associated with various Occupy movements. In particular, we focus on Serkan Taycan's “Between Two Seas,” an artistic mapping and walking project that was produced and put on display in 2013 for the 13th Istanbul Biennial.Footnote 2 Between Two Seas is an invitation to walk between the Black and Marmara Seas along the planned route of Kanal Istanbul, a government megaproject to build a real estate development of unprecedented scale along an artificial sea-level water canal to the west of the Bosphorus [Figure 1].

Figure 1: Kanal Istanbul's route.

Between Two Seas is a participatory artwork that seeks to raise consciousness of the dramatic transformation of Istanbul's periphery. The artist's invitation to walk along the area set aside for the canal has been taken up by many individuals and collectives from Istanbul, elsewhere in Turkey, and beyond. The artist deliberately avoids defining Between Two Seas as a reaction to Kanal Istanbul; nevertheless, the work is a response to the rapid and colossal transformation of the periphery of the city in which Kanal Istanbul takes part.

We first discuss how neoliberalism materializes in megaprojects, and how these in turn trigger different forms of urban resistance. Urban megaprojects, and the neoliberal mode of spatial production more generally, have become subject to protests for the “right to the city.” In what follows, we situate Between Two Seas within a lineage of walking-as-resistance projects. Next, we discuss the artwork and other contemporary artistic responses to urbanization in Istanbul and assess their overall efficacy. Such activist art projects may not bring down megaprojects or the government imposing them, but they do challenge them, exposing various myths that lend them credence and revealing underlying networks of power.

Neoliberalism, Megaprojects, and Resistance

Urban theorists have used the term neoliberalism since the 2000s to describe the current urban condition in cities across the world. Numerous previous theories – post-modernism and post-Fordism as theorized by David Harvey,Footnote 3 the post-modern city theorized by the Los Angeles School of urban geographers (Edward Soja, Mike Davies, Allen Scott, Jennifer Wolch, and Michael Dear),Footnote 4 and Saskia Sassen's theory of the “global city”Footnote 5 – have made significant contributions to our understanding of the role of cities within a new global financial and political order. Neil Brenner and Nik Theodore, perhaps the most oft-cited authorities on neoliberalism, explain that neoliberal doctrine promotes unregulated markets with a belief in the disciplining role of competition in the marketplace.

Since the 1980s, neoliberalization has emerged as a global geo-economic project with powerful implications for cities. The belief that markets can be relied upon to self-regulate is highly contested, as waves of economic crises have revealed economic instability around the world, leading to externally imposed austerity measures and, reciprocally, protests against them. Yet, “mechanisms of neoliberal localization”Footnote 6 continue to be pushed more than ever by increasingly authoritarian national governments in cooperation with multinational corporations. Among these mechanisms, the construction of large-scale megaprojects comes to the fore.

Megaprojects are intended to attract corporate investment, reconfigure local land-use patterns, and promote economic growth, but their attractiveness for politicians and their electoral base ultimately lies in their ideological promise of development and progress. In contrast, opponents argue against megaprojects as being not only globally imposed, requiring the coordination of global capital and state power at the expense of local interest or public good, but also unnecessary – hence their key difference from historical building projects of great scale.

Colossal architectural projects have been undertaken for millennia: the most famous examples include the Great Wall of China, commenced in the seventh-century B.C., and the Suez Canal, built in 1869. Contemporary megaprojects are justified as helping to spur local economic growth and give national economies access to global financial networks and visibility on the international stage.Footnote 7

The term megaproject is relatively recent. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, the first use dates from 1976,Footnote 8 while Alan Altshuler and David Luberoff attribute its coinage to the Canadian government and the Bechtel Corporation, who used the term to describe large-scale energy development projects in the late 1970s.Footnote 9 Paul Gellert and Barbara Lynch identify four broad types of megaprojects: infrastructural, extraction, production, and consumption.Footnote 10 They emphasize “displacement” in their definition of megaprojects, of people, communities, flora and fauna, and the earth itself.Footnote 11 In fact, most scholarship on neoliberalism and cities offers a critique of the doctrine of neoliberalism and emphasizes its negative effects. This is especially pronounced in urban studies in Turkey.Footnote 12

In Contesting Neoliberalism, Helga Leitner, Jamie Peck, and Eric S. Sheppard identify a “political fatalism” in neo-Marxist accounts, which focus on the damning but eventually self-destructive nature of neoliberalism in structural terms.Footnote 13 Also an emphasis on the power of neoliberalism to dispose and displace may have the unintended effect of reifying the doctrine. Along with taking the suggestion of Leitner, Peck, and Sheppard of “looking beyond neoliberalism, to the social movements and political projects that coevolve with it,” we prioritize “walking in the periphery” – what we identify as an emerging political project among activist-artists and ecological activists. In line with such critiques, we seek to focus on neither the material manifestations nor the conduits of neoliberalism, but rather the resistance projects and social movements that evolve in direct response to it. There is already a growing body of literature on urban resistance from within spatial disciplines (e.g., geography, planning, and architecture), much of which has focused on the occupation and reclamation of formal public spaces such as streets and parks.Footnote 14

In Turkey, the most poignant example of urban resistance took place in 2013 in Istanbul. The seemingly successful government of Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (Justice and Development Party, AKP) was in its third term when political analysts were taken by surprise by civil resistance against plans to develop Gezi Park, a public space abutting Taksim Square. The protests were triggered by a violent crackdown on a small group of peaceful demonstrators seeking to protect the park from demolition. The AKP's proposal and punitive action were seen by the millions who joined the protests as emblematic of the ruling party's increasingly authoritarian and neoliberal tendencies, that it was stifling freedom of speech and constraining citizens’ right to shape the future of their city. The protests may have failed according to one set of criteria – the AKP government was not toppled, and by 2018 the demolition of the Ataturk Cultural Center on Taksim Square had begun along with the construction of a new mosque across the square; and furthermore, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan seems adamant about building his mall on Gezi Park – but it also led to unprecedented, previously unimaginable unification, and challenged irrevocably the AKP's hegemony. The Gezi Movement led to a new political consciousness about the democratic process (or its failings) and gave rise to new awareness about the environment and to the “right to the city” as a rallying cry against displacement by the forces of neoliberal urban development and political power.

Scholars have observed that Erdoğan's government uses megaprojects as tools for building hegemony.Footnote 15 The proposals for Gezi Park or Taksim Square are small in scale compared to his other megaprojects, the largest of which are the Third Bosphorus Bridge, now the Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge (completed 2016), the Istanbul New Airport (slated to be opened in October 2018), and Kanal Istanbul. Erdoğan announced Kanal Istanbul during his 2011 election campaign as a “crazy project” [Figure 2]. Since 2011, preliminary earthworks have reportedly begun but a tender is yet to be held as of September 2018.Footnote 16 The projects for the periphery of the city have not garnered as much protest as Gezi did, although it can be argued that this is because the Gezi Park protests implicitly took aim at these projects as well.

Figure 2: 2011 Election campaign advertisment.

Aside from expert condemnation of these megaprojects, few critical voices have been heard due to Erdoğan's chokehold on print and other mass media in the aftermath of the Gezi Movement. In this restrictive atmosphere, various groups critical of the government's approach to urbanization have emerged, appearing at face-to-face events, meetings, and on social media for publicity and announcements. They include gardeners – many community gardens have emerged in Turkey, nicknamed “gardens of resistance” – ecological activists, activist-artists, and new non-governmental organizations such as The Northern Forests Defense (Kuzey Ormanları Savunması), an association campaigning against megaprojects that threaten Istanbul's ecology and supporting other ecological struggles around Turkey.Footnote 17

Around the world, megaprojects have given rise to environmentally-oriented social movements beyond the NIMBY (not in my backyard) type of local resistance such as No TAV, Stuttgart 21, and the Gezi protests. These movements are typically heterogeneous, with no economic class, age, gender, or ethnic group dominating. They prefer grassroots and democratic (leaderless, horizontal) formations in their organizations and use an array of creative methods of protest, ranging from occupations and collective dinners to festive musical, theatrical, and other artistic gatherings. Some of these movements also build transnational connections and solidarity networks, such as the Forum against Unnecessary Imposed Mega Projects.Footnote 18 Governments increasingly use militarized tactics, such as water cannons and tear gas, to dispel such peaceful opposition.

Scholars of megaprojects suggest that the mechanisms used to implement them erode the democratic process, leading to de-politicization.Footnote 19 Although many movements against such projects fail to achieve their immediate goals before being neutralized by the state, they have helped raise new political consciousness by “re-politicizing space”Footnote 20 as well as disseminate new forms of resistance and knowledge production by virtue of their very presence. In a unique twist, the act of walking has emerged in post-Gezi Istanbul as a subtle form of urban resistance.

Walking-as-Resistance

Walking may seem to be one of the most mundane acts, but it is associated with a number of diverse and complex social practices, including political resistance. It can be performed individually as well as in groups, with varying structure or none, and is primarily understood as a means of getting from one point to another. In contemporary urbanism, walking-oriented neighborhood planning is upheld for its potential to contribute to healthier lives – though such utilitarian understanding of walking is quite modern.Footnote 21

Anthropologist Marcel Mauss is credited with the first critical examination of the act of walking. In a 1934 essay entitled “Techniques of the Body,” he argued that this seemingly basic function of the human body was in fact a learned, socially constructed technology of the self which differed in look from one part of the world to the other.Footnote 22 Writing in the 1960s, urbanist Jane Jacobs emphasized the importance of streets and sidewalks and, by extension, walking.Footnote 23 In the 1970s, Ricard Sennett suggested encounters in public spaces had a democratizing effect on the city.Footnote 24 The most influential theoretical essay on the power of walking or walking-as-enunciation is Michel de Certeau's “Walking in the City” (1980). De Certeau builds on Michael Foucault's discussion of the Panopticon to suggest that the elevated view belongs to the logic of top-down power, the corporation, the institution, and the state.Footnote 25 As a form of resistance, pedestrians can use the street tactically and imaginatively, their path never fully determined by imposed order. The binary schema in de Certeau's model – top-down power versus man on the street, domination versus resistance, vertical versus horizontal – has been aptly criticized.Footnote 26 Walking, in de Certeau's formulation, is more a metaphor about audience practices rather than walking in the bodily sense as discussed by Mauss. Nevertheless, it is de Certeau's text which has had most influence in theoretically attributing agency to walking as a mode of political resistance.

How did walking come to be historically associated with resistance? There are many different methods, according to who is doing the walking, how, where, and for what purpose. There seem to be two distinct streams, however: cultural and artistic. Walking in carnivals is a type of group walking that informs present-day political protests. Whereas today's carnivals are commercialized, historically they provided a platform for social and political criticism “allow(ing) for the display of social hierarchies and their temporary abolition.”Footnote 27 In keeping with the carnival tradition, walking has served as a medium for nonviolent social movements associated with several revolutionary figures such as Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.Footnote 28 Political walking practices of the 1960s and 1970s took many forms, as Joseph Anthony Amato explains: “from solemn candle-carrying, hymn-chanting processions to disorganized, carnival-like strolls to defiant and militant demonstrations, most of which at the start protested segregation in the South and then the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War.”Footnote 29 While semi-structured, with pre-determined dates and routes, the carnivalesque protest walks’ forms, performances, and sounds differed distinctly from those of marches or military parades organized specifically to communicate the ruler's or colonizer's power.

Unstructured individual walking in the city was elaborated upon by Charles Baudelaire in the late nineteenth century, Walter Benjamin, the Surrealists, and the Dadaists in the first half of the twentieth century, and the Situationists Internationale in the 1950s, and has been taken up by various conceptual artists and arts groups thereafter, such as the contemporary Italian group Stalker.Footnote 30 Walking in the modern metropolis evokes different feelings and responses. Flânerie involved walking, but it was in fact a mode of urban spectatorship specific to the modern city.Footnote 31 Baudelaire's (male) figure, the flâneur, appreciated the transitory, contingent, and fugitive aspects of strolling the boulevards of the modern city as a leisurely yet disinterested observer. Having translated American writer Edgar Allan Poe's literary works into French, Baudelaire was inspired particularly by Poe's short story “Man of the Crowd,” whose narrator trails a man through crowded London streets.Footnote 32 In Baudelaire's reformulation, “The Painter of Modern Life,” the protagonist is not merely walking, but searching too: “He is looking for that quality which you must allow me to call ‘modernity’.”Footnote 33 This is an artistic figure representing the emblem of aesthetic modernity. Writing in the 1920s, Walter Benjamin revived the figure of the flâneur in his Arcades Project.Footnote 34 Flânerie moved out of the arcades to the sidewalks, flourishing in the boulevards constructed by Haussmann. In Benjamin's writing, flânerie was an attempt to “reprivatize social space”;Footnote 35 it wasn't by any means a mode of resistance to commodity capitalism.

Flânerie was reinvented by the Dadaists as small-scale group excursions to explore on foot the “banal places” of the city, and the flâneur was transformed from disinterested observer to participant in a performance. This approach was adopted by the Surrealists, and later adapted by the Situationists on the streets of Paris, where, by the mid-1950s, the concept of dérive (drift) was included among the frameworks for direct action alongside psychography, detournement (diversion), construction of situations, and unitary urbanism. Dérive was different from flânerie as performed by the Surrealists: “Chance is a less important factor in this activity than one might think: from a dérive point of view cities have psychogeographical contours, with constant currents, fixed points and vortexes that strongly discourage entry into or exit from certain zones,” as Guy Debord explained in the Theory of the Dérive. Ideally, the dérive was to be pursued by groups of two or three people in similar states of awareness over the course of a single day. It was to be used to draw up new maps that would provide knowledge about long forgotten or ignored venues, which may be hidden in official cartography.

Walking-as-a-Medium for Art

In the mid-twentieth-century, artists in Europe and the United States began using “walking” as a medium for artistic productions. In search of non-commodifiable art, they identified their walking practices and experiences as the art itself. Land artist Richard Long translated his walks in the countryside into works of art by bringing into the art gallery photographs of marks he made on the ground, mud, stones, and other collected natural objects. According to cultural geographer Tim Edensor, “Long's walking body is accompanied and impacted upon by the sensual rhythms of varied temporalities in nature.”Footnote 36 Other artists, such as Paul Gaffney, Janet Cardiff, Graeme Miller, Marina Abramovic, Phil Smith, Hamish Fulton, Tina Richardson, and Vito Acconci, staged walking performances and then recorded them using such media as photography, sound recording, drawing, and painting to transport and relay the work to audiences elsewhere.

Today, positioned somewhere between art and protest, walking practices have been taken up by ecological activists, activist-turned-artists, urban design professionals, and non-governmental organizations in cities such as London, Paris, Athens, Hong Kong, New York, and Moscow. Istanbul is no exception. Among its local walking actors, academic-architects Sinan Logie and Yoann Morvan recently published a book about their walks on the outskirts of the city.Footnote 37 As part of their work within the Center for Spatial Justice in Istanbul, they lead collective walks, helping participants to read the history and layers of urban fabric deemed out of sight (of touristic attention).Footnote 38 Another collective, Karakutu (Blackbox), organizes memory walks in different parts of Istanbul to critique recent, neoliberal-tinged urbanization in a program called “Memory Journey” whose aim is “that young people explore and question the injustices against the historically marginalised groups, based on religion, gender, ethnicity, or political view.”Footnote 39 Likewise, the feminist activist group Curious Steps within the Sabancı University Gender and Women Studies Program leads “Gender and Memory Walks” in the historic core of the Beyoğlu district to remember the contributions of women artists, many of whom were from ethnic and religious minorities, who lived and worked here contributing to the entertainment sector, nightlife, and public culture of the city.Footnote 40 Artist and storyteller Trici Venola also organizes walking events, specifically art walks, around Istanbul “featuring major attractions such as Hagia Sophia, but specializing in the odd detail and often-overlooked aspect of this multi-layered place.”Footnote 41 Some of these projects have been especially inspired by Taycan's Between Two Seas, which also participates in a collective conversation about walking in the city as a response to the fear-inducing transformation of Istanbul.

Between Two Seas

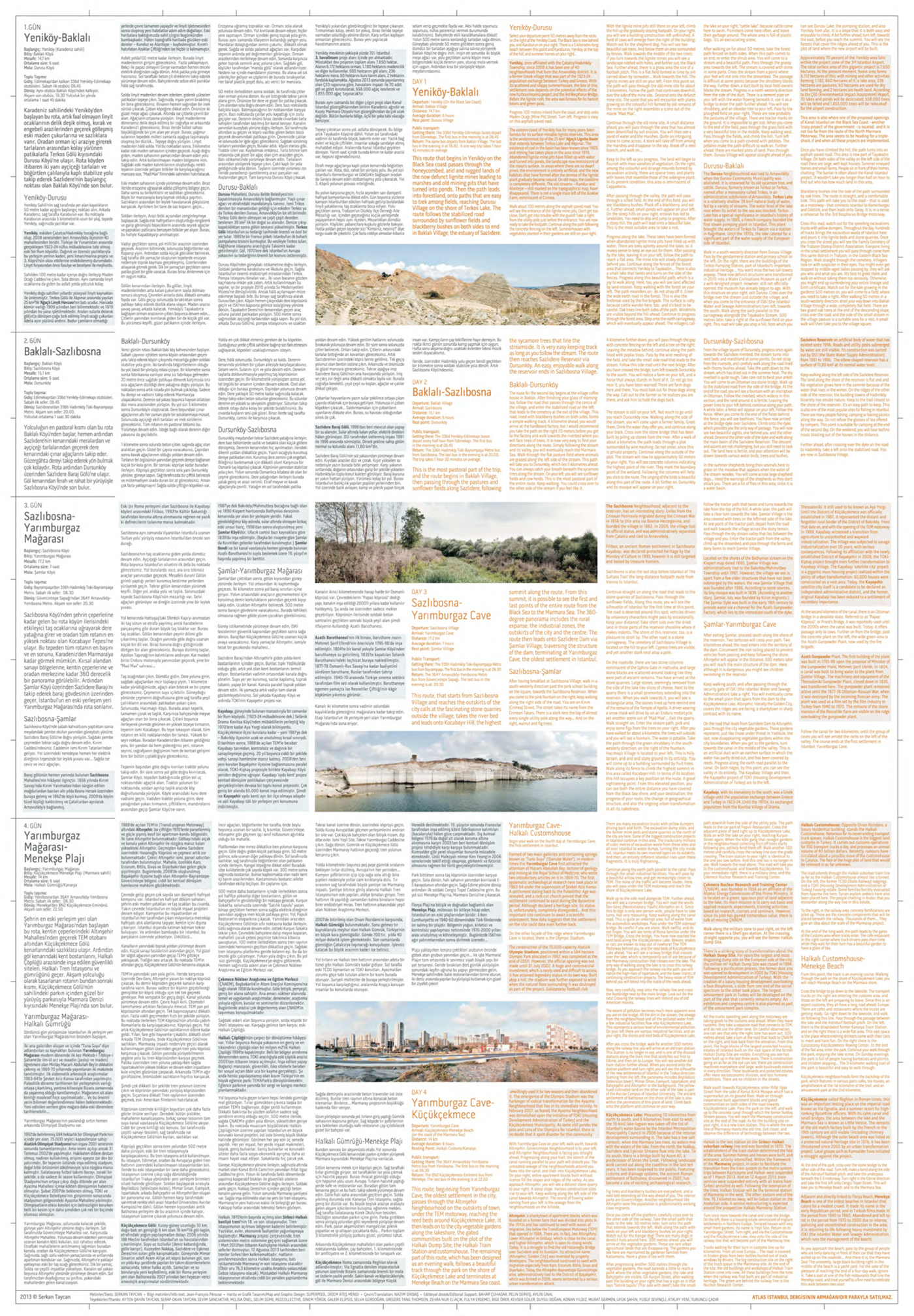

Between Two Seas first made its appearance at the 13th Istanbul Biennial. It presented photographs of the route neatly arranged on four white shelves on one wall and the guide on the adjacent one – folded and stacked, the front showed the terrain, and, unfolded and pinned flat on the wall, the back showing the narrative itinerary and descriptions, displayed side by side [Figures 3, 4 and 5]. Taycan explains that the photographs were a last minute addition: His initial aim with the exhibition was to provide complimentary copies of the map and to offer transportation to the visitors from the exhibition space to and back from the beginning points of the route. However, the above-mentioned withdrawal of the biennial from public spaces meant he had to substitute a series of photographs from the route in lieu.

Figure 3: “Between Two Seas – Installation View.”

Figure 4: “Between Two Seas.” Map (front). Authors’ copy.

Figure 5: “Between Two Seas.” Map (back) narrative guide. Authors’ copy.

This edition of the biennial was curated by Fulya Erdemci and featured the theme “Mom, Am I Barbarian?” (September 14 - October 20, 2013).Footnote 42 It was originally inspired by questions of public space and, more specifically, the urban transformation of Istanbul, the relationship of power and capital, and the impact on ecology and social relations.Footnote 43 However, following the violent repression of the Gezi Park protests, which took place that summer, the fall Biennial withdrew in its choice of locations.Footnote 44 Still, several projects exhibited at the Biennial, in fact in the same building and exhibition space (Galata Rum Okulu), directly took on the ongoing urban revolution.

One of the projects exhibited in the same space as Between Two Seas was the Sulukule Platform (2007–2013), in which an association of local activists came together to resist the heavy-handed government-led gentrification (dubbed “kentsel dönüşüm” in Turkish, or “urban transformation”) of an inner-city Roma neighborhood and the forceful eviction of its residents from 2005 to 2008.Footnote 45 While the wholesale eviction, demolition, and rebuilding of this neighborhood could not be prevented, the platform created a “community of practice” and became an important precedent for Gezi protests.Footnote 46 Another work, “Networks of Dispossession,” was originally an online social network-mapping project [mulksuzlestirme.org] led by Yaşar Adanalı, Burak Arıkan, Özgül Şen, Zeyno Üstün, Özlem Zıngıl, and anonymous volunteers, to visualize the relationship of capital and power through the connections of private companies, finance organizations, government institutions, media firms, and urban projects. This was translated into a gallery exhibition for the Biennial.Footnote 47 Between Two Seas was in good company among these works directly taking on the state-led urban transformation of the city.

It is, of course, also possible to examine the work in relationship to the artist's oeuvre. Taycan had completed a trilogy entitled “Habitat,” “Shell,” and “Agora” that laid the groundwork for Between Two Seas [Figure 6]. Undertaken in 2013–4, “Agora” documented Istanbul's well-known public squares from elevated vantage points. Preceding that, “Shell” documented the earth mounds, earthworks, and massive construction activity in the periphery of the city. “Habitat” (2007–9) took on the topic of place-based identity through shots across Anatolia. Of these three, “Shell” confronts the urban transformation of the periphery of the city. It is conversant with other activist documentary photography of Istanbul's changing urban periphery, such as “Million Dollar View” (2012–3) by the Nar Photos Collective.Footnote 48 Between Two Seas is different from “Shell” and other documentary activism in that it exceeds a photographic project. By presenting itself as an itinerary and map, it is an invitation to walk, to tell stories, and to engage critically with the transformation of the periphery of the city.

Figure 6: “Shell #21.”

Between Two Seas traces the approximate route of the proposed Kanal Istanbul. Taycan acknowledges the canal project as a source but is also wary of naming it, which would, according to the artist, legitimize it.Footnote 49 Therefore, he deliberately connects it more to Gezi than to the Kanal project. In his own words from his artist's portfolio:

Between Two Seas is a child of the Gezi Resistance. The project has many identities and is a sum of all the following: an activist and artistic project – first presented at the 13th Istanbul Biennial in 2013 – a 4-day walking trail, a collaboration of participants that subject themselves due to this direct, physical experience, a workshop and social act aimed at present and future solidarity. It produces a log and a narrative of the massive detrimental transformation the approximately 70 kilometre-route between the Black Sea and the Marmara Sea which is facing ruin due to the uncontrolled, threatening attack on both city and nature.Footnote 50

The Canal

While we share the artist's reluctance to publicize the canal project, some background description may be useful for readers who are not exposed to the Turkish media-sphere. Perhaps the most revealing aspect is that the public has little information on the project. When, in the middle of an election campaign in 2011, Erdoğan announced Kanal Istanbul, it received heated media coverage and more limited scholarly criticism. Ensuing scholarly discussions of the project have focused on its impending economic and environmental impacts as an infrastructure project and international legal implications.Footnote 51

Based on our analysis of 2011 election posters, speeches, press releases, media coverage, and scholarly interpretations, as well as civil society and artistic responses, we make several suggestions about this megaproject. Kanal Istanbul seeks to build an imagined future of the city by re-drawing and re-designing the city's past, a territory deemed to be empty. Erdoğan has developed a political discourse based on an urbanism of illusionary images, legitimized by their reference to the past. In addition to being a major infrastructural project, Kanal Istanbul is a key symbolic project, significant for understanding this particular political sphere.

At the center of the project will be a new artificial canal between the Black Sea and Marmara Sea, parallel to the west of the Bosphorus. Announced as a “crazy project,” the audacity of Kanal Istanbul was a key pillar of Erdoğan's successful election campaign in 2011 and since then it has been resurrected in traditional news media, now controlled wholly by the government at politically strategic moments. Most of the information released by the government is in the form of a promotional YouTube video.Footnote 52 According to the little information available, the artificial waterway is only but the spine of the project. While exact dimensions and route descriptions have kept changing over the past seven years, the waterway is projected to be a 50 kilometers long maritime transportation canal, 150 meters wide and 25 meters deep. Along its route, it will feature the largest airport in Turkey, a seaport, a motorway, bridges passing over the canal, connection roads to the recently completed Third Bosphorus Bridge, railway bridges passing over the canal, new residential areas, congress and convention centers, cultural facilities, tourism facilities, business districts, and recreational areas.

There are several points of legitimization for the canal project, announced on the pro-government TV channels and published in mainstream newspapers. First, infrastructural and real estate projects help put Istanbul on the “map” of global cities and propel Turkey ahead among emerging markets. Hence, the future Istanbul depicted in the Kanal Istanbul plan mimics familiar global city images. The global ambition is further demonstrated in a themed section of buildings designed to represent the architecture of those nations with whom Turkey has or wants to build strong trade ties, reminiscent of Disney's “Epcot World Showcase” in Florida. According to the promotional YouTube video, it will include Turkish, American, Brazilian, Chinese, French, German, Indian, Iranian, Italian, Japanese, Spanish, and Thai architectural styles. These buildings will be run by citizens of those countries, with lower floors used as restaurants and upper floors used as home offices, demonstrating that the intended audience of the “bay” zone is to be tourists, wealthy visitors, and investors.Footnote 53 The second point of legitimization is that current traffic on the Bosphorus is dangerous for the existing natural and cultural heritage. The Turkish Straits Vessel Traffic Service (TSVTS) reports that the export of natural resources extracted in countries near the Caspian Sea has dramatically increased traffic in the Bosphorus strait: according to various Turkish agencies, it sees an average traffic of 150 ships each day. Thus, the government promotes the canal as a means of minimizing the threat of accidents and ecological strain on the Bosphorus, especially by oil tankers. The third selling point is that by reducing ship traffic on the Bosphorus, the canal will allow it to be used once again for recreation, as it was during Ottoman times.

In response, critics have pointed out several legal, environmental, cultural, and financial limitations to the government's plans. Legally, the Montreux Convention Regarding the Regime of the Turkish Straits limits the Turkish state from closing the Bosphorus to foreign ships. Signed in 1936 by ten states, including Australia, Bulgaria, France, Greece, Japan, Romania, Turkey, Yugoslavia, UK, USSR, the convention returned control of the straits to the Turkish military on the condition that it not stop vessels from passing through them, including on the basis of a new canal. Thus, in order to redirect shipping traffic, Turkey would have to convince the convention's signatories to agree to a revision.Footnote 54 Environmentally, scientists warn the canal would result in an ecological disaster. Istanbul's only remaining forest areas, located in the northern part of Istanbul and dubbed the city's “lungs,” would be destroyed by the new settlements and recreational activities envisioned by the plan.Footnote 55 Because the Black Sea and Marmara Sea are at different levels and have different salt ratios, oceanographers speculate that a canal between them would endanger aquatic life in both seas.Footnote 56 Third, archaeological sites such as the Yarımburgaz Cave, which dates back to the Stone Age, would be irrevocably ruined.Footnote 57 Fourth, the project faces financial obstacles. The Turkish banking system is too small to finance a project of this size, which according to the government's optimistic calculations, would cost $10 billion. Foreign investors would be needed to bankroll such a sum, and this could create economic dependency in the long run.Footnote 58

It is hard not to notice the emphasis on size in any promotional account of the canal, and how that emphasis substitutes for any discussions of benefits. “Smart,” or New Cities, is the new mantra of such colossal development. Usually presented through glossy images, these projects lack specificity and promote instead idealized lifestyles detached from local realities. This boldness of vision is not unique to Erdoğan. In China, India, Egypt, and other emerging economies, leaders advocate for economic growth fueled by new cities. What is unique in this and similar cases is that it is not only historic pastiche in the architectural idiom of a few buildings: some of these megaprojects also transform geography and even rewrite geological time. Regardless of the similarity in approach – populist national politics run on an urbanism of images – each country has its specific conceits.

In the case of Turkey and Kanal Istanbul, two tropes have been mobilized: conquest and magnificence, both invoking an Ottoman Golden Age. The promotional video describes Erdoğan as the second conqueror of Istanbul and the conqueror of New Istanbul. Promotional material and write-ups emphasize the canal was in fact the dream of the 16th century Ottoman sultan, Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520–66). New buildings in the New Istanbul area are to be built in the Seljuk and Ottoman styles. Hotels, bazaars, and market places are to be placed throughout the project and a mosque complex built in the middle of the New Istanbul area.

The reference to the “magnificent project” in the 2011 election poster positions Erdoğan as a leader on par with Süleyman the Magnificent. 2023, the 100th anniversary of the Republic, is presented as the “target” for completing the project, also marking the beginning of a new century for Turkey in which the country would be guided by Islam and economic liberalism, rather than the Republic whose guiding principles included secularism/laicism and statism. Kanal Istanbul, then, is more than a real estate project; it is a conduit to mediate the vision of a leader who will propel Turkey to its next Golden Age, the notion of which, of course, is an essential component of ethnic nationalism.Footnote 59

The slowdown of the economy in the last decade has led the AKP government to rely on megaprojects to sustain growth rates, by means of an increasingly diffuse discourse of ethnic nationalism. The canal is one of many projects undertaken without public consultation. In fact, numerous accounts and analyses linked the Gezi Park protests to all recent megaprojects, including the canal project, and to the AKP's disregard for public opinion, citizens’ rights, historical and cultural heritage, and the environment. The conceptual scheme is based on a simulacrum of Istanbul. The Ministry of Transport, Maritime and Communications seems to be running the project from the capital, Ankara, 450 kilometres away from Istanbul, and pitching it to international financial investors without input from Istanbul's urban authorities, and with apparent disregard for the city's municipal plans, its physical needs such as fresh water access, and the people who live or use the land on the route of the proposed canal.

While Kanal Istanbul would produce radical physical, ecological, economic, and social changes in Istanbul, its intellectually critical yet contingent effect has been the contemporaneous rise of contestation at the local scale, and the ensuing shift from debates on the negative effects of neoliberal restructuring of cities toward issues of social justice and the city: a shift signalling the re-politicization of space. Specifically, the contribution of artistic projects such as Between Two Seas has been to highlight the lack of knowledge about the periphery of a city undergoing immense transformation, turn that into a collective learning opportunity, and create a community around walking in the periphery.

The Effects of the Walk

The trajectory of the proposed canal as well as Taycan's project pass through lignite mines, an area earmarked for the new airport, the road leading to the Third Bosphorus Bridge, excavation dump sites, industrial sites, and housing areas. In the past five years, Taycan has been organizing walking workshops along the 69-kilometre “hypothetical” route of the canal, inviting the public to experience the rapid transformation of nature and the built environment in Istanbul's peripheries [Figures 7 and 8]. He has been documenting this change through photography and geospatial mapping. While it seeks to highlight the ecological, social, and historical impacts of completed and ongoing urban transformation projects including the canal, Between Two Seas is more than a negative critique of megaprojects. It is not just a “walk” either: it is first a call for active spectatorship and activism; second, it is a performance intended to create new social relations as in “relational art”; and finally, it incorporates visualization techniques such as mapping and photography to amplify the work beyond the participants.Footnote 60

Figure 7: Artist discussing the route with an international group prior to the walk. The walks are organized and disseminated through social media.

Figure 8: Walk by “Hiking Istanbul,” a group established following Gezi protests and with inspiration from “Between Two Seas,” and in association with Kuzey Ormanları Savunması (Northern Forests Defence) activists. September 23, 2017.

As they read the artist's map with its annotations or walk on the suggested route, participants see that this land is not the empty canvas it appears to be on official maps. On the ground, they observe diggers excavating earth while trucks carry that earth elsewhere, and they develop a keen sense of the exchange of property, which is a driving force in the current neoliberal urban economy. There are entire forests with teeming ecosystems soon to be displaced and extinguished. There are villages still engaged in subsistence farming and providing essential foodstuffs for the city soon to be bulldozed. As they walk on Taycan's route, participants observe the radical transformation of this periphery with highways and new “themed” real estate developments, isolated enclaves with typically large-scale tall apartment buildings. One of these enclaves, Bosphorus City, which lies on the route, may be considered a precursor to Erdoğan's canal project, as it features a mini-canal of its own themed after the Bosphorus Strait. The popularity of a miniaturized Istanbul, as walk participants can see for themselves, “has moved on from the representational realm of the exhibition.”Footnote 61 Most importantly, walkers see each other as a group against rampant urban transportation, united through the act of walking together. In this sense, walking is performed as a quest for knowledge, an act of solidarity, and an act of resistance.

Conclusion

Neoliberalism has increasingly been spatialized through megaprojects: projects imposed top-down that divert public resources to benefit private interests, and without consideration for preserving the locales of the sites being transformed. Ruling political and financial actors typically use exceptional measures, from expropriations and other extra-legal means to the lack of environmental regulatory mechanisms to the police force, to implement megaprojects. Urban resistance against neoliberalism has more successfully united against specific megaprojects rather than class or identity-based demands such as those regarding the rights of minorities or labor conditions. These local resistance movements have built on earlier social movements but are also unique in the way they transcend class, united in their calls for democratic access to decision-making processes. Governments have responded to this with violent crackdowns, leading to a withdrawal from formal public spaces, but this only led to the emergence and proliferation of creative and artistic practices.

In the case of Kanal Istanbul, the public has had little to no information on who the project is for, what the real cost is, what the designs are, or what implications it will have on Istanbul. In most media promotions, it sounds as if the terrain is simply blank, in need of development, while in actuality it is a landscape full of life and home to diverse uses. In addition to joining other activist-artist projects in documenting Istanbul's transformation, Taycan's Between Two Seas invites participation by walking: a bodily knowledge gained by experiencing the probable route of the canal and seeing for oneself the falsity of government-sponsored notions of a tabula rasa ground condition. This form of critical spectatorship is not only individually empowering, but also politically transformative. New social formations and creative citizen actions have emerged in the aftermath of the announcement of the canal project. The unintended effect of such megaprojects, in fact, is to mobilize new political consciousness.