How often do libraries make the headlines? About as often as societies choose to invest them with meaning greater than their day-to-day functions. In the last decade and a half, only a handful of national libraries in the Middle East and North Africa have garnered international media coverage, including Egypt's Bibliotheca Alexandrina, the Iraq National Library and Archive, the recently-opened Qatar National Library, and the Mohammed Bin Rashid Library, which is shaped like an opened book and planned to open in Dubai in 2019 [Figure 1].Footnote 2 In some cases, the news articles draw attention to the uniqueness of a library's collection; in others, it is the size of a patron's donation. In every case, however, they consider how a library's architecture conveys cultural and even political messages to the general public.Footnote 3

Figure 1: Left, Mohammed Bin Rashid Library, Dubai, UAE (under construction), 2019; right, Qatar National Library, OMA Architects, 2017.

Recently, the National Library of Israel (NLI) has also made the headlines as it is being moved to a new building under construction in West Jerusalem and as its institutional mandate undergoes transformation.Footnote 4 Known formerly as the Jewish National and University Library (JNUL), the NLI had long operated as a division within the Hebrew University. In 2007, the Israeli Knesset passed a law defining and expanding the NLI's objectives and functions, which built upon efforts by the library's leadership to reform its operating structure, governance, and public mission.Footnote 5 This transformation was accompanied by calls for a new physical home, an edifice appropriate to the revised mission of a prominent national institution. Not surprisingly, the development of the NLI's new building has attracted media attention as well, not least because of the public controversy and, later, scandal over its design competition. As a result, the building, slated to open in 2021, will look very different [Figure 2] from the design proposals first made public in 2012. What will its architecture say about the National Library of Israel, about the politicians and philanthropists who commissioned it, and about the society that will use it? What was its architecture expected to say?

Figure 2: The National Library of Israel, Jerusalem (under construction), 2016.

The NLI's revised institutional framework and design follow global discussions about what libraries are meant to be. Around the world, libraries and their staff face changes to the management of their collections and new expectations about their public function. The transition from printed to digital media is one obvious change; the increasing financial burden of physical document storage is another. More fundamental, however, have been changes in cultural expectations about the proper role of libraries.

Libraries in Transition: From “Knowledge Culture” to “Discourse Culture”

In a 2013 essay published by the NLI, “From Knowledge Culture to Discourse Culture,” Israeli historian Moshe Rosman identified a shift in the Israeli public's understanding of what roles a library should fulfill.Footnote 6 According to Rosman, a “Knowledge Culture” has long prevailed among libraries, including the JNUL for most of its history. Such a culture emphasized the value of acquiring knowledge and of the elite class that cultivates and preserves it:

Since by its very nature access to it is restricted … knowledge culture has traditionally been housed in quasi-Temples or Palaces of Culture…. Visitors are allowed in for a defined period of time and permitted to enter only a few well-marked areas. They often feel disoriented, “lost,” in such places, requiring the guidance of members of the elite to help them get their bearings.Footnote 7

Rosman argues that the NLI's institutional transformation is a result of a shift towards “Discourse Culture” and that this shift will inevitably be embodied in the design of the new building.Footnote 8 According to Rosman, Discourse Culture emphasizes access to knowledge and the value derived from its consumption. The transition towards it is not merely a consequence of how digital media operates but also reflects increasing social diversity, from “cultures in conflict to cultures in dialogue.”Footnote 9 Thus, libraries are increasingly expected to facilitate an “interpretive or participatory examination of social phenomena.”Footnote 10 Just as importantly, a Discourse Culture library becomes more than the mere sum of its collections, acting as “a powerful cultural force, a ‘player,’ beyond its role as repository.”Footnote 11

Some controversies surrounding the NLI stem from disagreements about the mechanisms of discourse and the identity of its participants:

• Under what circumstances does “discourse” about culture occur?

• How do media and physical spaces support discourse?

• Which media or spaces are prioritized by discourse about culture?

• How do media and physical spaces serve their audience? Or do they engage multiple audiences in multiple – even contradictory – ways?

• What is the relationship between Discourse Culture and a civic culture, that which stands at the foundation of government and national identity?

These questions lie at the heart of the NLI's institutional and architectural history. Unbuilt designs from the first phase of the NLI's 2012 design competition sought to envision spaces (architectural and non-architectural) in which Israeli Discourse Culture might (or might not) be constituted. Furthermore, the competition results also recalled Israeli architects’ long-standing argument that architecture itself, as a discipline, should define the spatial locus of a common Israeli culture.

History, Architecture, and the Perseverance of Knowledge Culture within the JNUL

The idea of a “national” Jewish library dates to the 1870s, when early Zionist philanthropy in Europe and the United States sought to establish new Jewish cultural institutions in Ottoman Palestine.Footnote 12 The sobriquet “people of the book” suggested at least one common value to which Jews in all cultures could aspire. And although the earliest library proposal was conceived as a repository of only religious writing in Hebrew,Footnote 13 subsequent proposals expanded their scope to include works about Jews in other languages and even secular topics. Generally, the motivations for establishing a Jewish library in Palestine were nationalistic and sought to prepare the cultural infrastructure for Jews’ national revival.Footnote 14 Nevertheless, attempts in 1875 and 1884 to open reading rooms for the Jewish community in Jerusalem were thwarted by Jewish religious authorities who rejected such tendencies.Footnote 15

Up until this time, libraries and reading rooms in Palestine existed mostly in the consulates of Western governments, in Christian archeological institutes, and in churches that consolidated previously dispersed holdings.Footnote 16 For the Muslim population, manuscripts and books were assembled by Jerusalem's elite families. Smaller collections of religious tracts may have been available to the public in mosques or legal institutions.Footnote 17 None of these libraries served the growing Jewish population's interests or needs.

Jerusalem-based members of the International Organization of B'nai Brith established the Midrash Abarbanel Library in 1892. The lexicographer Eliezar Ben Yehuda contributed 200 volumes from his own collection, and in 1895 physician Joseph Chasanowich of Bialystok provided 10,000 additional volumes.Footnote 18 A dedicated library building opened in 1902. Its design was modest and consistent with the contemporary local vernacular for new commercial structures located outside the walls of Jerusalem [Figure 3, left]. In 1905, the Seventh Zionist Congress in Basel endorsed a proposal to turn the Abarbanel Library into the core of a future National LibraryFootnote 19; fifteen years later, ownership of the library was transferred to the World Zionist Organization for that purpose.Footnote 20

Figure 3: Left, Midrash Abarbanel Library (1902); right, Wolffsohn University and National Library (Frank Mears and Benjamin Chaikin, 1930).

Particularly influential for what would become the National Library of Israel was an essay by German-Jewish librarian Heinrich Löwe.Footnote 21 As historian Dov Schidorsky has written, “Löwe proposed that the national library fulfil functions and provide services that in other countries are normally the province of three different types of libraries. It would be a scholarly library, a public library, and a popular library.”Footnote 22 Thus integrated, a single library would provide the intellectual resources necessary for a revived Jewish nation. With the opening of the Hebrew University in 1925, Löwe's ideas were put into practice. A substantial bequest from a prominent donor, David Wolffsohn, provided the means to relocate the nascent National Library to the Hebrew University.Footnote 23 The collection moved to a purpose-built building on Mt. Scopus in 1930 [Figure 3, right], where it was visible throughout the geographical basin that contains Jerusalem's Old City.

In the aftermath of the 1948 war, Israeli access to Mt. Scopus was lost. The JNUL collection was evacuated to locations in West Jerusalem, and both university and library functions operated under ad hoc conditions until the construction of a new Hebrew University campus in Givat Ram, near the government complex. In 1960, the Lady Davis Building became the JNUL's new home [Figure 4]. This facility, widely considered a modernist architectural masterpiece, remained the home of the JNUL even after the 1967 war allowed renewed access to Mt. Scopus. It is in this building that the National Library of Israel has recently assumed its redefined mission, pending the completion of a new building nearby.

Figure 4: Jewish National and University Library (Alexandroni, Armoni, Havron, M. Nadler, Sh. Nadler, Powsner, Yaski, 1960). Left, exterior view. Right, interior view, main reading room.

With the founding of the State of Israel, the JNUL assumed some of the responsibilities of a national library, including the legally mandated collection of two copies of every book and newspaper published in the country. Yet the corporate status of the JNUL, ostensibly a unit of the Hebrew University, remained ambiguous, and so it had limited opportunity to solicit revenue from other sources.

Transition to “Discourse Culture”: Changes to NLI's Institutional Framework

Despite the continual growth of the Hebrew University, the JNUL's operating budget did not keep pace. By the mid-1990s, the budget for acquisitions had fallen considerably, and staff cuts reduced activities in preservation and cataloging.Footnote 24 A report commissioned by Israel's Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sport, along with the Hebrew University and Yad Hanadiv (a charitable organization founded by the Rothschild family in 1958), complained that the JNUL served poorly its role as a national library, or any of its other roles.Footnote 25

The committee that created the report included two heads of the most prominent national libraries in Europe and the United States: Dr. James Billington, librarian of the United States Congress; and Dr. Gunther Pflug, former director of the German National Library. Joining them was David Vaisey, librarian of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, UK (a center for Judaica as well as other prominent special collections), and Dr. David Shulman, director of the Hebrew University's Institute of Advanced Studies. The committee was charged with evaluating the JNUL's existing tripartite mission as Israel's national library, as the Hebrew University's central library, and as a “library of the Jewish people.”Footnote 26 With such a broad mandate, the committee felt well within its purview to propose radical changes to the JNUL's institutional basis, its administrative hierarchy, and its physical infrastructure. The committee's conclusions were stated without equivocation:

The Library must modernize itself: it must open its collections more widely and efficiently to scholars and the community at large…. Instead of simply storing books (mostly underground), the Library should make them present and available to users in a physical setting which is inviting, gracious, and efficient…. Such an “environment of the book” will serve the national function, broadly defined in light of the Library's position as the finest library in the country in all humanistic disciplines, in addition to its task of preserving all evidence of Jewish civilization throughout history.Footnote 27

The committee's final words were no less direct: “The Library must be reborn. Only then will it achieve its place as a matrix of creative cultural and scholarly activity … where the resonant voices of the past can come alive to speak … to future generations.”Footnote 28 In short, the committee encouraged the JNUL to shift decidedly towards Discourse Culture.

The Hebrew University accepted the committee's recommendations and canvassed the Israeli government about implementing them though appropriate legislation.Footnote 29 But government officials rejected converting the JNUL into a state agency or its equivalent. Some objected, on principle, to the government's involvement in the direction of an otherwise “professional” body and argued instead for the library's continued independence.Footnote 30 In 2002, a second committee was assembled to address the library's status itself. Issued in 2004, this committee's report agreed with the government's position and proposed that the library be re-established as a public-benefit company – essentially, an autonomous utility – rather than a branch of the state.Footnote 31 In 2007, Israel's parliament passed a law closely modeled on those recommendations.Footnote 32

The 2004 committee report also stipulated that Israel's national library be located in Jerusalem, the country's seat of government. It demurred from recommending a precise location, but gave the following criteria for its selection:

1. Providing a suitable presence for the National Library in a setting and in a space where it is to be located; possibility of creating a fitting public image as a national institution.

2. Guaranteeing easy, convenient and available access for the general public, totaling hundreds of thousands of visitors a year.

3. Possibility of operating separately from the Hebrew University, in terms of access routes, parking, and visiting days and hours.

4. Continuing ties with the academic community of the Hebrew University and other research establishments.

5. Economic efficiency, which will naturally be reflected in using the existing building.

6. Making sure that there is proper physical infrastructure (parking places, security, etc.).

7. Possibility of using the National Library's facilities for the purpose of educational and cultural formats.

8. The extent to which the possible locations match the range of the library's physical needs.Footnote 33

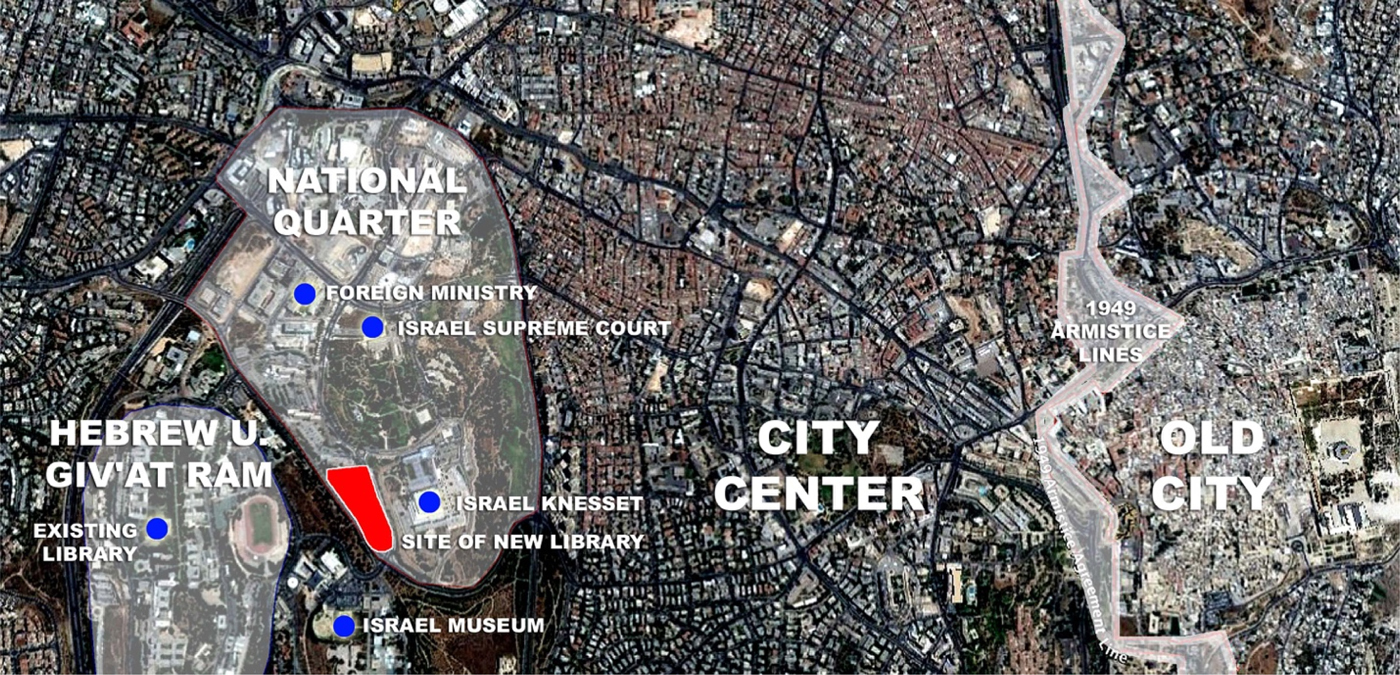

With obvious emphasis on the first three items, these criteria would eventually lead to the library's placement within Israel's “National Quarter,” the seat of most government buildings, yet close also to the Givat Ram campus of the Hebrew University.Footnote 34

In February 2010, the Israeli government made a cabinet-level decision to identify such a parcel, previously set aside as open space, as the site for the new library building [Figure 5].Footnote 35 This move drew criticism from some observers for abandoning the Lady Davis Building, a familiar architectural icon. In response, the NLI's first director, David Blumberg, argued publicly for the need to set the new library apart from the Hebrew University. As journalist Noam Dvir wrote:

Its location in the heart of [the University] – with all its security-related and accessibility problems – became “a millstone around the library's neck, and not an advantage,” [Blumberg] says… Moreover, moving to the new site, situated between the Knesset and the Israel Museum, is supposed to afford the institution an independent identity, both symbolically and physically, along with state-of-the-art cataloging and collecting capabilities. The move is expected to bump up the number of users significantly, from 10,000 to more than 200,000 a year.Footnote 36

Figure 5: Aerial view of Israeli “National Quarter” in Jerusalem. Red marks the site selected in 2010 for the National Library of Israel and nearby buildings of significance.

Blumberg's words suggested that critics and advocates alike were arguing at a deeper level about the cultural shift that characterized the reborn NLI and its proposal to move to a new building.

Some university people said: “What – are you building a National Library ‘community center’?” This was the most contemptible thing that could have crossed their lips … We see the openness of the library and accessibility to its holding as key elements in our activities … The more people in Israeli society are exposed to the works and the treasures that are here – the more we will be able to do.Footnote 37

Blumberg and other NLI decision-makers seem not to have noticed that the National Quarter is remote from Jerusalem's busy commercial center, a legacy of modernist urban planning whereby political and cultural institutions were spatially separated from the “messy” areas of residential, commercial, and religious activity.Footnote 38 Nevertheless, following the official signing of the NLI's corporate charter in March 2011, a public call for architects’ proposals was issued in January 2012, with submissions due three months later.

Discourse Culture in the Realm of Architecture

Why call for a competition to design the Israel National Library? What were the expectations and terms surrounding the competition's call? A competition can solicit high-quality designs from high-profile designers, according a project great prestige and cultural capital both in domestic and international contexts. They also give the public a tangible glimpse of new government initiatives, which otherwise might be too distant or abstract to perceive. They can be used to gauge political support for a particular project: a realistic architectural rendering tends to solidify public opinion for or against an institutional initiative, whatever the merits of the design itself. At the same time, such competitions act as a forum for the exchange of new architectural ideas, visual or otherwise. Some architects equate the holding of “open” competitions with democracy itself, since typically the market for designers’ services is contingent on private contracts, even with government agencies.Footnote 39 In Israel, architectural competitions have long been significant events for many stakeholders in the public process,Footnote 40 but often for different and even contradictory reasons.

National Library of Israel leadership conceived the competition to draw public support for their venture. Yet the format of the competition differed from “traditional” Israeli competitions. Following the precedent set in 1984 for the design of the Israeli Supreme Court, the competition would take place in two stages. The first, anonymous and uncompensated, would be open to all architects registered in Israel. The second would include four contestants selected from the first phase, and eight architects (four Israeli and four foreign) invited directly to compete in this phase.Footnote 41 From among these twelve architects, competition judges would prepare a short list of three, who would then present their project to the committee. In turn, the committee would present the highest-ranked project for consideration by the NLI's board of directors and the National Library Construction Company (NLCC), the shell company formed by Yad Hanadiv to manage the project. Yet competition terms emphasized that the search was for more than an architectural design. As a press release issued by the NLCC explained,

It is important to note that the competition does not only entail reviewing architectural plans and choosing an architectural design. It seeks to find an inspiring individual, capable of bearing the responsibility for designing a building that will serve the Library for years to come, and for anticipating rapid technological developments and frequent changes in the way we use information.Footnote 42

Despite the legalistic specificity of the competition process, and its apparent endorsement by the Israel Association of United Architects, many designers complained immediately that the competition shattered (again) the norms surrounding architectural competitions.Footnote 43

“Reading” the Competition: First Stage

It is to the competition's first, open stage that observers can look first for evidence of an “Israeli” interpretation of the National Library's institutional mandate. Eighty-one Israeli architects submitted entries to the first stage of the competition. A broad survey of these designs (eventually published online in ad-hoc fashion by competition participants) demonstrates the unsettled diversity within Israel's architectural culture. The range of approaches is, in fact, characteristic of open competitions the world over. As historian Hélène Lipstadt has explained, architects have long seen competitions as laboratories for intellectual experimentation.Footnote 44

In April 2012, a panel of judges reviewed the submissions. The following month, the NLCC announced their conclusions. The designs of Gil Even-Tsur, David Zarhy, Daniel Assayag, and Rafi Segal made it to the second round.Footnote 45 A closer look at these four projects reveals substantive propositions about the National Library in its specifically Israeli context.

In a published description of his firm's project, for instance, Gil Even-Tsur calls so much state-sponsored architecture “mirror-traps (expressing a perfect, unyielding, unchanging structure)” and cites philosopher George Bataille: “‘Great monuments are erected like dikes, opposing the logic and majesty of authority against all disturbing elements; it is in the form of cathedral or palace that Church or State speaks to the multitudes and imposes silence upon them. It is, in fact, obvious that monuments inspire social prudence and often even real fear.’”Footnote 46 With respect to his design, he evokes a spatial analogy to Moshe Rosman's definition of Discourse Culture as open, multivalent, and malleable.

We believe that our most important work is not defending, fortifying, defining ourselves/our societies, but exploring and improving ourselves/our societies. We are strong when we are open to change. The goal of our architecture is to fully engage this criticism of architecture and the state through a form that resists singularity in favor of multiplicity and complexity, while still seeking beauty, function, and strength of composition.Footnote 47

The published images of Even-Tsur's design align the concept of “openness” alternatively with literal transparency (where the building connects with the ground) and with interpretive freedom, given the abstractness of the building's bulk above. Yet the design is, intentionally, quite the opposite of “populist.” The result evokes a sophisticated image in line with Israel's long-standing Modernist architectural tradition, epitomized by the NLI's current Lady Davis Building [Figure 6]. At the same time, Gil Even-Tsur's education in New York and professional training there with architect Richard Meier underscore the internationalism of so many Israeli architects who have cultivated personal links to Europe and the United States.

Figure 6: National Library Project (2012). Left: view of exterior from the north. Right: interior view of reading room.

The entry of Zarhy Architects emphasizes not “openness” but efficiency, expressed by its compact and relatively vertical composition [Figure 7]. The building's relationship to the surrounding landscape is formal, with little obvious interconnection. Instead, Zarhy Architects proposed for the library's roof a series of open-air terraces, described as “additional social spaces” to complement the building's working spaces. The architects explained that the digital age demands a shift in thinking about the NLI “from a place of acquiring knowledge to a place of exchanging knowledge.”Footnote 48 The heart of the building, a series of large interior volumes through which stairs would wend upwards, would express even more forcefully the library's transformation.

Figure 7: National Library Project (2012). Left: view of exterior from the southwest at Ruppin Road. Right: view of central space and stair.

Daniel Zarhy and his collaborators envisioned a single harmonious structure whose parts would integrate seamlessly under one design while articulating their own individual character in response to the specific needs of different parts of the building.Footnote 49 An “Israeli” architectural legacy is tempered by the building's highly machined appearance. Although Daniel Zarhy studied architecture at Tel Aviv University, he too has worked abroad, collaborating regularly with designers in the Netherlands and in Switzerland.Footnote 50

Jerusalem-based architect Daniel Assayag, in collaboration with Alex Meitlis and the UK-based Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios, had more to say about the potential of the National Library's design to create its own genius loci. Doing so meant more than working with the existing topography or geography. Rather, the designers conceived the building's entrance as a reinterpretation of the existing JNUL's best architectural feature: a pathway underneath the bulk of the building, open to the adjacent gardens [Figure 8].Footnote 51

Figure 8: National Library Project (2012). Left, view from the south towards building entrance. Right, view from within exterior “atrium.”

In the new design, the building bulk was itself opened up and made light. As the architects explained, “the building is part of the landscape rather than an object on it … allowing education and culture as well as research and study to take place as part of this garden of knowledge.”Footnote 52 Furthermore, the visual character of this “garden” depended heavily upon specific environmental tropes, familiar across a broad spectrum of Israeli society: textured stone walls and paving, linked traditionally and by legal mandate to construction within Jerusalem's municipality; terraced garden walls, akin to contemporary Israeli land-form housing designs meant to evoke the character of traditional Palestinian buildingsFootnote 53; tall columns borrowed from the institutional architecture of Israel's “developmental modernism”; a reflecting pool and water channel to belay the nation's anxiety about limited water resources; and, in a central location, a mature evergreen tree. Through the use of all these tropes, this project's design was intended to promote a place in which each distinct spatial experience would foster a unique kind of dialogue.

The fourth project [Figure 9], by Rafi Segal, then design critic at Harvard University's Graduate School of Design in the United States, also conceived the National Library as landscape, specifically, as “a ‘landscape of stone steps’ which ascend the bedrock and resonate with the terraced hills of Jerusalem.”Footnote 54

Figure 9: National Library Project (2012). Left, aerial view of proposed library seen from the west, towards the Knesset. Right, interior perspective of the main reading room.

Of the entries in the second competition phase, Segal's was the most obviously rhetorical: its monumental interior spaces were designed at a scale consistent with the outsized ambition of a small nation. As Segal's team wrote, “The library building is not placed ‘on site’ but as a foundation rebuilds the site,”Footnote 55 referring not only to the library functions enclosed by the design's large stepped-roof canopies but also to the resulting landscape above. Competition renderings depict library readers sitting up on the roof, traversing its undulating structure, and reading documents there. However impractical, given the sun's intensity in that region, Segal's roof design offered a compelling case for the National Library's ultimate transformation. From the NLI's new vantage point, “contested Jerusalem” might at last become the idealized version of itself: its structure made up of elemental stone and concrete, its terrain an abstract maze, and its occupants (apparently) free from conflict over control, about boundaries, or even identity. Such social and political implications are only implicit in the architects’ written description, but as they also write,

The library building … upholds the Information Age dictum that knowledge be a field of interaction rather than an object of control and containment…. As knowledge is liberated from its historic carriers, so is architecture freed to provide more flexible and diversified spaces.Footnote 56

At the same time, the project's visual message is unambiguous: through architecture, the library's patrons and their environment may be also liberated from “historic carriers.”

Different as they might appear, the four projects selected in the first round shared the following principles:

• The NLI's architecture should express the institutional transition towards Discourse Culture. In practical terms, this meant the provision of architectural spaces that visually emphasize acts of movement and, in reciprocal fashion, spaces that allow library users to witness acts of movement.

• The building's solution should be integrated extensively with propositions about a uniquely Israeli landscape. In each of these four projects, the NLI's institutional message is interpreted in large part through the architects’ definition of (and design for) “ground.”

• The Library's specific architectural elements must evoke the material characteristics of contemporary Israeli Jerusalem. These four projects did so in different ways, but generally by orchestrating contrasts between familiar, symbolically charged materials and their opposites, in order to highlight the former. Examples include certain kinds of stone masonry, a color pallet of light earth tones, and – most importantly – a subtle visual dialectic concerning massiveness and lightness.

This dialectic is present in many buildings designed in Jerusalem by Israeli architects, although it is not uniquely Israeli. In the local context, however, it may best correspond to tacit concerns among secular Israelis (including the architects participating in the competition) about the persistent co-existence of traditional cultural or religious norms in an otherwise forward-looking modern society. For architects and the general public alike, the visible interplay between solidity and void, between rough and smooth – or simply between old and new – is the architectural counterpart of changing social norms. If one can indeed “read” the collective message of these four architectural designs, one might conclude that if the NLI does become a prominent site of Israeli discourse, that discourse will be inspired primarily by those concerns.

Results of the Second Stage: Award, Scandal, and Retraction

After the first competition phase, these four Israeli architects and their teams continued to refine their designs alongside an additional eight architects, selected from among Israel's best-known architects and from the world of global “starchitects.” The former included Ada Karmi-Melamede; Bracha and Michael Chyutin; Carlos Prus; and Udi and Ganit Mayslits-Kassif. The latter included David Chipperfield (United Kingdom); Shigeru Ban (Japan); Moshe Safdie (United States, the base of his main office, although he has also an office in Jerusalem); and Bohlin Cywinski Jackson (United States).Footnote 57

In September, the judges selected three teams to present their work in person to the jury, after which the jury made its selection: architect Rafi Segal, pending a final contract between the architect and the NLCC.Footnote 58 In a press release, the chairman of the NLI's board explained that “the proposal reflects internalization of the historical significance of the national library and expresses the needs of the library in an age of social and technological change.”Footnote 59 The chair of the competition jury, Luis Fernandez-Galiano, praised the urban relationships between Segal's design and nearby public buildings in the National Quarter.Footnote 60

Within only a few weeks, however, the announcement drew criticism from a local politician named Yair Gabbay, a member of Jerusalem's Planning and Building Committee. The subject of his complaint had nothing to do with Segal's design; instead, Gabbay insisted that Segal himself was not a “worthy planner … from among the Zionist architects living in Israel.”Footnote 61 Gabbay referred to Segal's leading involvement in an exhibit for the 2002 World Congress of Architecture in Berlin. Published in book form as A Civilian Occupation: The Politics of Israeli Architecture, the show documented Jewish settlement in Israel, focusing mainly upon settlements since 1967 in the West Bank. The Israel Association of United Architects had originally commissioned the exhibit, but withdrew its support and suppressed the exhibit in advance of its official opening.Footnote 62 After a public exchange of recriminations, Segal and his collaborators published the book separately.Footnote 63 A decade later, Segal's part in that controversy was a target for right-wing politicians such as Gabbay, who objected to Segal's being awarded the NLI project while ‘spitting on Israel all over the world.’”Footnote 64

Additional, apparently unrelated complications arose soon after.Footnote 65 On December 19, 2012, the NLCC announced that it would terminate its negotiations with Segal.Footnote 66 Without giving an account of the process leading to its decision, the NLCC reserved the right to continue the search for an architect on its own terms. Doing so precipitated yet another media scandal, in which observers noted the extreme opacity of the NLCC's decision making and decried the Rothschild Foundation's lack of accountability in this and similar developments of such public importance.Footnote 67

Most of this episode's details are beyond the scope of this essay. Nevertheless, if the promise of open public and civic discourse lay at the heart of the National Library of Israel's institutional rebirth, how would the NLCC's handling of the design competition's results reflect upon the potential of the NLI to fulfill its mission? In fact, complaints about the competition results, before or after, had little to say about the merit of Segal's design, or about any of the competition entries. Instead, critics pointed to the failure of public discourse to engage, and to be engaged by, the physical planning of the National Library itself. Journalist Esther Zandberg claimed that the failure was inevitable, a consequence of a structural defect in the relationship between Israel's public affairs and private philanthropy. As she wrote, “That's how it is in a remote colony where the baron magnanimously funds the country's most salient public institutions: the Knesset, the Supreme Court and now the new National Library, meant to be the repository of our cultural treasures.”Footnote 68 Eyal Weizman, Rafi Segal's collaborator for The Politics of Israeli Architecture, echoed Zandberg's sentiments in an opinion piece titled “The Nationalist Library.” Weizman argued that the involvement of Yad Hanadiv in the development of Israel's public buildings has sustained nineteenth-century “colonial” attitudes among Israel's planners.Footnote 69 Referring to the management of the competition itself, Weizman also asked:

By what right does the state seek to construct a building that purports to represent and claim custodianship of Jewish people's cultural heritage – much of it written by the very people opposing Jewish nationalism or the nationalist politics of present-day Israel. Shouldn't a state project be by and for its citizens and subjects?Footnote 70

Subsequent developments demonstrated that, where public architecture is concerned, the answer to Weizman's question may be “no.” In March 2013, the NLCC voided the results of the two-stage competition.Footnote 71 A second by-invitation-only competition was quickly constituted and concluded within just a few weeks. In this competition, the number of architects among the judges was reduced in favor of representatives from Yad Hanadiv.Footnote 72 In April 2013, from a reduced field of just six architects, Swiss architects Herzog and de Meuron were chosen.Footnote 73 According to the terms of the revised competition, they were selected based on their credentials alone, without having submitted a design. It was not until eighteen months later, in November 2014, that plans for the new building were finally released to the public [Figure 1]. The building's cornerstone was laid in April 2016,Footnote 74 and the extensive excavations required for the building's foundations began later that year. Construction of the National Library of Israel is scheduled for completion in 2021.Footnote 75

Conclusion: Architecture and the Efficacy of Discourse Culture

Since the release of Herzog and de Meuron's design, volatile public discussion about the new library building has receded. Still, some Israeli architects have complained about the outsized monumentality of the entire projectFootnote 76; others opined that the final design was not monumental – or “iconic” – enough.Footnote 77 To judge from the current temperature of public opinion, however, most are sympathetic to the NLI's final design. Eschewing the linear severity of Segal's earlier competition proposal, Herzog and de Meuron's project is lyrical, light (if solid), and seemingly open at ground level to all sides [Figure 10]. Interior renderings give the impression of great luminosity, as well as easy access to the library's collections. One can discern a subtle atavism in the overall roofline, curved from side to side. The shape is akin in reverse to the nearby Shrine of the Book museum, whose roof is said to recall the shape of the ceramic jars in which antique scrolls were found.Footnote 78

Figure 10: The National Library of Israel (under construction). Left, exterior view of proposed library. Right, interior perspective of the main public space.

More fundamentally, however, the diverse constituencies that make up the Israeli public have yet to come to terms with the manner in which public architecture should become public. Israeli society has become increasingly characterized by extremes of poverty and wealth, yet decision-makers in government and the private sector appear less and less to need (or want) input from a class of “technocrats” sufficiently independent to affect public affairs. To be sure, this trend is hardly unique to Israel and has occurred in nearby Middle East countries that have liberalized their economies. On the other hand, in Israel the trend remains a matter of public contention just like security, religious influence, or even national identity. As the multiple controversies surrounding this and other design competitions demonstrate, Israeli architects continue to advocate for their profession's autonomy in planning the country's built environment. Fewer and fewer, however, anticipate its success.Footnote 79

Meanwhile, less than 20 miles to the north, another national library has already opened its doors. In August 2017, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas announced that the Presidential Palace near Ramallah would be used instead as the National Library of Palestine.Footnote 80 As Abbas's minister of culture, Ehab Bseiso, told reporters, “the announcement of the project this year, which marks 100 years since the Balfour Declaration, is a message to the world that the Palestinians are inexorably linked to the homeland, as a matter of right, culture and identity. That is the cultural answer to the Balfour Declaration, and we are saying this out loud: We are staying here on our land.”Footnote 81 Although the architecture of the converted palace is aspirational in its own way, its aesthetics seem to matter little to the politicians who conceived the project. Bseiso added that establishing the library represents a “cultural-political vision which flows from the necessities and reality of the future,” and will serve as key Palestinian cultural center.Footnote 82 Once again, a library is in the news.

When the new National Library of Israel opens its doors, it will not be the architecture alone by which the institution's success is measured. Scholarly usage, access to artifacts, and the number of library visitors will no doubt be important metrics of assessment. Nevertheless, the building's architecture will have an observable impact. Indeed, the NLI leadership and Yad Hanadiv have shared with the curators of the canceled 2002 exhibit The Politics of Israeli Architecture at least one fundamental, if perhaps tautological, proposition: that architecture is indeed the “space” in which all discourse finds its “place.”

Disclaimer:

The author was employed between 1994 and 1999 by an architecture firm of which Daniel Assayag, one of the architects mentioned in this article, was co-principal. During that time, the author worked with Yishai Well, who received honorable mention at the conclusion of the competition's first stage and whose written work has been cited in this article.