Starting in 2010, the United States, European Union, and United Nations imposed a series of sanctions on Iran's oil and financial sectors in response to the unresolved and growing “threat” of the country's nuclear program. Ayatollah Khamenei and other officials quickly declared the sanctions to be an opportunity to strengthen a homegrown “resistance economy” (iqtiṣād-i muqāvimat) that would be impervious to the machinations of hostile foreign powers like the United States. Via the news media they aggressively promoted the nuclear program's technical accomplishments as an example of domestic capabilities in the face of a Western-dominated global economic order seeking to rob Iran of its sovereignty. For regime officials and supporters most opposed to greater political or economic engagement with the West, the sanctions could even provide Iran protection from the moral and cultural threat of neoliberalism disguised as foreign investment and free trade.Footnote 1 These calls for economic self-sufficiency resembled in tone the rhetoric of self-sacrifice and denial that, according to Fariba Adelkhah, had invigorated the revolutionary struggle and the Iran–Iraq War effort previously.Footnote 2 Of course, the longstanding dependence of government budgets and, correspondingly, the livelihoods of millions of Iranians on oil revenues made any plans for achieving economic autarky highly dubious. Indeed, the processes of “globalization,” especially the removal of trade barriers via state policies, international organizations, and even violent coercion, have seemingly undercut the potential for autarky in today's world. Nevertheless, both domestic and foreign-based polling outfits reported that a majority of the Iranian public supported the acquisition and use of nuclear technology for peaceful purposes.Footnote 3 That same public would also bear the brunt of the sanctions regime in the form of subsidies cuts, massive inflation, joblessness, consumer shortages, and widespread government corruption and mismanagement. Iranian negotiators reached a deal with global powers in 2015 to suspend the sanctions in exchange for limits on the nuclear program. However, the economic and social damage from the contraction of oil revenues and international trade were not so easily undone. Ironically, Iranian leaders’ insistence on maintaining a nuclear program has imposed some of the same austerity measures that those in the Euro-American orbit have often voluntarily adopted for full integration in a neoliberal “global economy.”Footnote 4

Given the limited scope for news analysis and debate on Iranian state and state-censored media outlets, further insights on the general public's response to the sanctions regime must be found elsewhere. This essay examines popular culture, and especially the television viewing habits of Iranians, for responses to the country's economic and political isolation. Cultural elites the world over have labeled modern “mass” entertainments, including those found on television screens, as “mindless escapism” disconnected from everyday life. By contrast, they have claimed that other cultural forms (e.g., “art”) have provided privileged and unvarnished access to both inner and outer realities.Footnote 5 Mass entertainments may well offer up fantasies to audiences. However, those fantasies, via their interplay with the concerns and techniques of “realism,” invariably figure into representations of social and political life that the public statements of officials or opinion polls do not always reflect. Thus, millions of Iranians during (and after) the sanctions era nightly watched foreign and especially Turkish melodramas shown on offshore satellite networks. In doing so, they connected with consumerist utopias just beyond their borders where glamorous characters engaged in steamy love affairs, freely traveled around the globe, and indulged in the latest fashions and technology. At the same time, Iranians tuned into some homegrown serials on state networks that at least indirectly addressed the difficulties that ordinary people were facing during the sanctions regime. The comedy Paytakht/Capital (2011–15), is one such state television program that successfully competed for viewers with foreign-based satellite content. Capital not only focused on the lives of a pious, provincial working class family dogged by a series of financial crises but also eschewed the polish and “professionalism” of foreign melodramas for a realist, documentary style. This essay compares the thematic and stylistic concerns at the center of Capital with those of the glossier soaps on offshore satellite networks. Capital, in fact, follows a number of recent comedies on state television that have either implicitly or explicitly taken the “threat” of foreign-based satellite television as their referent. These two contrasting television trends may indicate for some a split in viewership—presumably between a more “cosmopolitan” demographic that watches foreign satellite programming and the more ideologically devout who watch only the Islamic Republic's networks. However, the essay concludes by asking how Iranians might enjoy Capital and offshore satellite programming simultaneously.

Consuming Media in the Islamic Republic and Beyond

Iranians since the Islamic Revolution have increasingly turned to television technology via a variety of different formats for their entertainment.Footnote 6 Ironically, state television has rarely figured into the medium's burgeoning popularity. During the bleak 1980s, when the Iran–Iraq War cast a long shadow over national life, the two state networks broadcasted little that viewers could describe as entertainment—with updates from the front, revolutionary propaganda, and religious programming monopolizing the airwaves.Footnote 7 Many who had access to video cassette players joined a fast-growing “video club” scene, where they could buy or rent films and television series banned from theaters and the state television networks.Footnote 8 This banned content circulating in Iranian homes could include music videos of exiled pop stars or the anti-Islamic Republic sermonizing of dissidents on foreign terrestrial networks, with many of these new recordings originating in California. Even after the war, when the state television networks dramatically expanded their bouquet of channels and signal strength to reach every corner of the country, new home video formats emerged to compete for viewers. Video CD and later DVD, with their compact size and lossless digital copies, made peddling and viewing the latest uncensored foreign hits and exile television far easier than before.

The post-war era also witnessed the explosive growth of satellite television in Iran, providing access to entertainment from regional commercial and state networks free of the Islamic Republic's censorship regime. Dozens of offshore Persian-language satellite networks too appeared, many of them operating on a shoestring budget. They broadcasted much of the same pre-recorded content that earlier or additionally circulated on videocassettes and discs. The Islamic Republic's television networks were themselves moving towards satellite technology for both domestic and overseas broadcasts during the 1990s.Footnote 9 However, foreign-based satellite television, especially channels originating in the West or beaming Western programming, became a target of fierce criticism from national leaders who viewed them as a “cultural invasion” (tahājum-i farhangī).Footnote 10 While some officials and clerics, especially since the end of the Iran–Iraq War, have supported economic liberalization and expanded trade with the world,Footnote 11 they have largely joined opponents of further integration in the global economy in vigorously opposing any accompanying cultural (or even consumer) liberalization. Consequently, Parliament in 1995 banned the possession and use of satellite dishes in private homes. Nevertheless, ownership of private satellite dishes has continued to grow with the post-2010 nuclear sanctions doing little to slow down this process. By government officials’ own admission, some 70 percent of the population is now in violation of the law.Footnote 12

A growing degree of corporatization and professionalization has seemingly characterized Persian-language foreign-based satellite networks over the past decade.Footnote 13 Newly established media companies like the GEM Group and Marjan Television Network and even international conglomerates like News Corporation have launched channels that moved away from what Hamid Naficy has described as the highly politicized and nostalgia-driven content of the first generation of exile television during the 1980s and 1990s.Footnote 14 Yet, official concern for these recent entrants in the competition for Iranian viewers (and values?) has only reached new heights. In fact, the GEM Group's founder, Saeed Karimian, was murdered in Istanbul in April 2017 with some commentators alleging the Islamic Republic's involvement.Footnote 15 The new satellite channels have also employed a different business model from many of their predecessors, relying more on commercial advertising than donations from Iranian exiles.Footnote 16 Their programming heads have in turn sought to attract viewers by filling prime viewing blocks with successful foreign series, especially ensemble melodramas, dubbed into Persian by experienced voice-over actors. While there is some original, largely reality-based, content, foreign soaps have been the focus of network schedules. Iranian satellite viewers’ enthusiasm during the 1990s and early 2000s for US productions like Dynasty (1981–1989) and Baywatch (1989–2001) may well have contributed to these networks’ decisions on content.Footnote 17 News Corporation's Farsi1 relied in particular on Fox-owned properties like The Bold and the Beautiful (1987–) and 24 (2001–2010) to populate its lineup.

However, these new satellite networks have also followed television trends originating in the Middle East like the burgeoning popularity of Turkish soap operas. The private Saudi-owned Middle East Broadcasting Center (MBC) group was the first to bring Turkish television drama to regional audiences outside of Turkey in 2007. The early and astounding success of one series, Gümüş (2005–2007), named after its female protagonist and retitled Nur on MBC, opened the floodgates to Turkish soap operas on Arabic-language satellite television where they have taken their place alongside Egyptian and Syrian dramas, American soaps, and Latin American telenovelas.Footnote 18

Although critics have often denigrated melodrama as antithetical to realism, the form has nevertheless been crucial to representing (and problematizing) modern realities—first in literature and theater, then cinema, and finally television.Footnote 19 Turkish television melodramas have seemingly taken advantage of new and “borderless” communications technologies to attract regional audiences. In doing so, they have followed in the footsteps of the “multinational” telenovelas that Ana Lopez has traced to the late 1980s.Footnote 20 She has claimed that these telenovelas’ storylines privileged cosmopolitan, upwardly mobile types in the major urban centers of Latin America whose careers and spending habits quite literally connected them to similar social groups across the “viewing area.”Footnote 21 In doing so, they articulated a transnational, consumer-oriented economy and society, which advocates of neoliberal policies and institutions have declared that these new communications technologies could help to bring into existence.Footnote 22 Correspondingly, many Turkish serials that have aired in the Arab world since 2007 take, according to Marwan Kraidy and Omar al-Ghazzi, modern, cosmopolitan Istanbul as their setting and focus on the lives of the city's elites and elite aspirants.Footnote 23 While these Turkish “social dramas” draw on class conflicts to complicate the romantic relationships at the center of their narratives, they also highlight the possibility of social mobility for their characters. One prominent example that Kraidy and al-Ghazzi have given of such class climbing is the title character in Nur, who overcomes her provincial past to graduate to a successful career in fashion and marriage into Istanbul aristocratic circles. Nur's “fashion sense” was crucial to her social advancement in the series and would apparently become a model for Arab female audiences to emulate, from clothing and make-up to home decorations.Footnote 24 Thus, it may not come as a surprise that many Turkish soap stars started out as advertising models before landing roles on television [Figure 1].

Figure 1: Former commercial stars Kıvanç Tatlıtuğ and Tuba Büyüküstün in recent Turkish export Cesur ve Güzel/The Brave and the Beautiful (2016–2017). The couple's modeling past lends itself to product placement as they and other characters drive a variety of Ford vehicles in the series, with the driving sequences’ cinematography often resembling that of advertisements.

For Kraidy and al-Ghazzi, the wider, regional appeal of such Turkish melodramas may in part be found in their slick representations of a new social class whose work, wealth, and especially consumption patterns are not necessarily limited to the nation of origin or by increasingly “obsolete” definitions of the national interest. Indeed, the seeming transformation of social outlooks and individual mentalities that the authors have highlighted in their study of Turkish soap operas and their audience effects eerily resembles what mass communications scholar Daniel Lerner once labeled “psychic mobility” in reference to earlier, more nation-specific media revolutions in the Middle East.Footnote 25 Yet, the authors have also attributed Turkish serials’ popularity with Arab audiences to their “Turkishness,” claiming that they present a successful and relatable package of modernity, which the more culturally distant telenovelas and American soaps presumably cannot.Footnote 26 However, what Kraidy and al-Ghazzi have taken to be integral to the Turkish imports on Arab satellite may not be shared by their audiences. Turkish melodramas’ reconciliation of a Western-oriented neoliberal vision may also attract Arab audiences because it involves a problematization of that vision. If people in the Middle East or elsewhere considered the so-called processes of globalization to be natural and inevitable, there would be little need for their often violent imposition.Footnote 27 In fact, the simultaneous popularity of historical dramas like Muhteşem Yüzyıl/Magnificent Century (2011–14) and its sequel Muhteşem Yüzyıl: Kösem/Magnificent Century: Kösem (2015–17) seems to complicate Kraidy and al-Ghazzi's overwhelming focus on the appeal of individual prosperity and personal consumption in Turkish social dramas for Arab audiences. The historical dramas also depict the consumption of luxury goods as well as the lives of Istanbul elites, namely those of the Ottoman court. However, those luxuries and those elites bear little resemblance to the technologized, consumer-oriented world of a jet-setting business class that viewers are supposedly tuning in to watch in many soap operas set in present-day Turkey. What Turkish historical and modern-day melodramas do appear to have in common is a focus on family dynamics, love affairs, friendships, and rivalries—or the interactions of two or more, often overlapping social circles centered around the main male and female protagonists. These relationships, their triumphs, and their missteps generate much of the melodrama within. A celebration of neoliberal economic policies and their consequences would appear to be more or less incidental to these programs.

The role that Kraidy and al-Ghazzi have claimed for Turkish soap operas in shaping Arab consumption patterns itself points to how many viewers in the wider Middle East have likely understood (and reconciled themselves to) a neoliberal economic order—as providing easier access to consumer and luxury goods that state protectionist policies had previously limited or banned. Indeed, the novelty of contemporary soap operas from Turkey would appear to be their blatant incorporation of consumerism and consumer advertising in the melodrama [Figure 1]. After all, family and friends–centered melodrama by itself is hardly an alien concept to viewers in the Middle East familiar with the historically important cinemas of the region. There may well be an increasingly aspirational dimension to consumption patterns in the region, which Turkish soap operas have likely promoted, but it is not entirely clear that personal aspiration is now (or was ever) the driver of much consumer behavior.Footnote 28 What might then for some commentators resemble American or Western-style consumerism and business practices (i.e., the spread of “globalizing” values) on satellite television imports may not have that same resonance for ordinary viewers.

Many of the Turkish television melodramas popular in the Arab world, including Nur, have found similar success on the new offshore Persian-language satellite networks. The ability of Turkish soaps to represent especially romantic and family relations in a more “realistic” fashion than what is possible in Iran may also contribute to their success.Footnote 29 For some Iranian viewers, Turkish serials represent a social vision entirely at odds with the Islamic Republic's regulative order and the various prohibitions it has placed on public male-female interactions and “fun.”Footnote 30 Moreover, the material lives (and, specifically, consumer habits) of certain characters in Turkish soaps have likely stirred the aspirations of millions in Iran even as nuclear-related sanctions made their achievement more difficult. In fact, Turkey both on screen and in real life has for some Iranians become emblematic of the prosperity that the Islamic Revolution and Iran–Iraq War denied them and their families. Unsurprisingly, it has also become a primary destination for Iranian tourists since those events, with shopping for items far more expensive and/or of limited availability at home a chief draw.Footnote 31 Of course, revolutionary rhetoric had long identified such material concerns to be barriers to Muslims’ ultimate salvation. Nevertheless, this threat of worldly corruption would not keep President Hassan Rouhani from making the lifting of nuclear-related sanctions and reconnecting with the global economy a chief campaign pledge during his successful 2013 election run. Accordingly, rivals especially associated with the Revolutionary Guards or the Basij militia have accused Rouhani and other like-minded politicians and intellectuals of betraying revolutionary principles and aiding foreign enemies in spreading an immoral materialism and hedonism in the Islamic Republic.Footnote 32 Turkish programs on Persian-language satellite networks have not necessarily revealed to viewers a way of life at odds with more official ideas of worldly prosperity in the Islamic Republic. Nevertheless, they have been another channel through which Iranians can remain in contact with a highly selective (regional?) interpretation of neoliberal consumerist lifestyles, which appear at least on screen to be available to a growing number of people.

Iranian state television for its part has, in concert with the rise of illegal satellite ownership and foreign satellite programming directed at Iranians, made greater efforts to showcase on its networks domestically-produced films and television series in order to attract the home audience. However, its moral and legal commitments as well as economic constraints have made direct competition with foreign satellite programs and Turkish melodramas in particular neither desirable nor realistic. Still, the lack of a level playing field has not meant that state television has held no place in the viewing habits of Iranians, as the success of Capital as well as a number of other recent homegrown comedies suggest.

Confronting Satellite Television and Sanctions in Capital

Turkish serials on satellite television, in spite of their popularity with Iranians, have had little to say about the conditions of life in today's Iran. Doubtless, one of the reasons viewers have also tuned into domestically produced programs is because they have featured Iranians living in Iran. Capital during its initial four “seasons” on Channel 1 quite clearly set out to showcase ordinary Iranian characters, both in life circumstances and in appearance—to the extent that the last name of the main character Naqi (played by Muhsin Tanabandih) is Maʿmuli or “ordinary.” Likewise, Naqi and his extended family hail from a small town in Mazandaran province called ʿAliabad, itself perhaps the most commonplace name in Iran. A heavy reliance on location shooting, hand-held camera work, and actors then mostly unknown to television contributed to this focus on the small details in the lives of small people.Footnote 33 This attention to detail even extended to the incorporation of local expressions in character dialogue and local folk music in the soundtrack.Footnote 34 In fact, the approach that the makers of Capital took in production shared little with Turkish melodramas and owed far more to post-1990s iterations of British social realism in film and television, which have also drawn humor and pathos from the complications of working class life.Footnote 35

While the name of the series refers to Iran's mega-city and capital, Tehran, it is a reference that increasingly loses its meaning over time. The initial plot conceit is the relocation of Naqi, his wife Huma (Rima Raminfar), and their twin daughters from ʿAliabad to Tehran so that he can find work as a plasterer and Huma can attend university. This “fish out of water” scenario is a source of humor in the first season but also a common, even clichéd, plot device in Iranian cinema and television. In fact, the many obstacles that the city and its denizens present to the family's attempts to move into their new home ultimately prompts them to return to ʿAliabad, which serves as the setting for much of the action in subsequent seasons. The final season, for example, has no scenes or storylines that take place in Tehran.

Tanabandih, who also supervised the writing, casting, and acting for Capital, thus ironized in his narrative a city that has been at the center of the most dramatic and devastating social transformation of the post-revolutionary era—namely the migration of millions to the major urban centers largely as an economic strategy and the concomitant depopulation of the surrounding countryside. This keen interest in issues and events of national as well as international significance was something that Tanabandih and his collaborators demonstrated throughout the series’ run, which only added to the realism of the storylines. To be sure, uncontrolled migration to the cities was also a Pahlavi-era problem but its pace and scale accelerated after the Islamic Revolution.Footnote 36 Capital not only reverses the population flow to Tehran but Tanabandih has in press interviews claimed to reject stereotypical depictions of the urban sophisticate and country bumpkin that some have accused his series of indulging in.Footnote 37 The series impresses on the viewer that the “capital” of the Islamic Republic is seemingly everywhere but Tehran. The contrast with some Turkish melodramas, which treat the mega-city Istanbul as a place where dreams are realized, is again striking.

Alignment of the narrative chronology in Capital with the airing schedule also enhanced the documentary-style realism that its makers employed. Thus Capital was first broadcast around New Year's Day (Nawruz) in 2011 and set during that broadcast window. The filming and editing of episodes from the second season onwards were completed just days before they aired, which ensured their timeliness.Footnote 38 State programmers’ placement of the series during the roughly two weeks around the holiday, when much of the country is away from work and with family, indicated their high hopes for the program's success. Its renewal for three more seasons, with the second and third season airing during the 2013 and 2014 New Year's holidays and the fourth in Ramadan 2015, was a validation of state television's hopes for it.Footnote 39 Like Ramadan in much of the Arab world, Nawruz has become a showcase for the most anticipated television programs of the year—underlining the character of television viewing in the Middle East as predominantly a family-centered and social activity. Capital in turn endorses the idea that home is wherever the family is.

Capital not only incorporates events of contemporary relevance into its plots but turns them into objects of satire. Thus, the first season is not only about runaway migration to Tehran but also the rising tide of immoral and anti-social behavior that has come to plague the city. Naqi and his family repeatedly encounter the general bad manners of their fellow citizens but also more serious offenses like family betrayals for inherited wealth, robbery, drug dealing and abuse, and real estate fraud. Social problems afflicting the working and middle classes seemingly organize every season. The second season spends several episodes exploring the thriving trade of human organs, which the makers present as too often motivated by donors’ financial distress and unscrupulous middlemen. The third season highlights marriage scams, unemployment, personal debt, and the challenges of environmental conservation in Iran. The final season attends to illegal construction projects, especially in the Caspian coastal areas, and the related problem of government corruption.

While the nuclear-related sanctions certainly contributed to the social problems on display, the series rarely attributes blame for society's ills to such outside pressures. The inescapable reality of the sanctions regime perhaps made any direct correlation unnecessary. In fact, its impact was literally imprinted on the screen. The Supreme Leader's office had since 2011 stressed the urgency for greater economic self-reliance and efficiency, through strategies like import substitution and the elimination of supposedly wasteful and unnecessary expenditures, to counter the intensifying foreign embargo on trade and banking. In 2012, those calls for an “economic jihad” (jihād-i iqtiṣādī) took on a more formal character under the rubric of the resistance economy, complete with a policy center to ensure government follow-through on its principles.Footnote 40 Khamenei has ever since inaugurated Nawruz with a new slogan for the resistance economy, which state programmers have then affixed to the top right hand corner of the screen during broadcasts, including Capital [Figure 2].

Figure 2: Rotating globe chyron from season two of Capital, which reads “Ḥamāsih-i siyāsī, hamāsih-i iqtiṣādī” or the “[Year of the] Political and Economic Epic”

Characters in Capital do themselves make occasional reference to the sanctions and the international negotiations aimed at lifting them. However, it is more the individual consequences of the sanctions that the series makers considered in these four seasons. Financial difficulties plague Naqi throughout the series’ run. A high school dropout, he only holds a full-time job during parts of the second season—a situation that both highlights the bite of sanctions on ordinary people and draws into question the efficacy of the resistance economy. Not only do economic conditions place consumer luxuries off limits to Naqi and others like him, but even basic necessities become a challenge. Naqi and his family are essentially “homeless” after the first episode and frequently reliant on his extended family's charity. In fact, the family spends much of that first season living in the back of a truck belonging to Naqi's younger maternal cousin, Arastu (Ahmad Mihranfar), who volunteered to help them move. Naqi and his immediate family are in subsequent seasons also forced into temporary and often shared living arrangements.

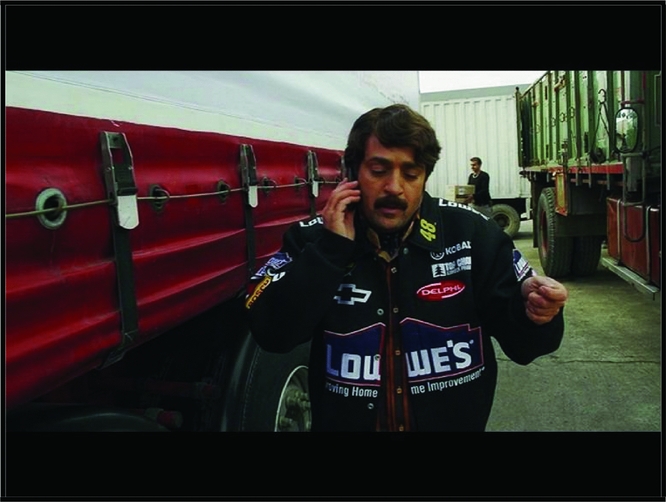

The sanctions theme gained further traction in the final two seasons to air, as the repercussions of declining oil sales along with a precipitous fall in oil prices took hold. Budget cuts to the state television networks had direct effects on the series itself, with the producers ironically compelled to accept product placement in order to cover their costs. In the third season, Arastu becomes a long-haul driver for the commercial sponsor, Atlas Mall, with their logo plastered on the side of his trailer and strategically parked in scenes for maximum exposure. Indeed, the makers’ lack of subtlety would suggest an additional, comic dimension to the product placement. It was during the third season when Tanabandih and company especially highlighted and problematized the divide that Khamenei and others had posed between the virtuous self-denial of a radical Shiʿi utopia and the corrupting self-indulgence of a neoliberal consumerist utopia—with Naqi and his cousin at the center of this divide. If Naqi is the hero in Capital, then the ironically named Arastu (i.e., Aristotle) is his sidekick and foil. In previous seasons, the rash and impulsive Arastu stumbled from one disaster to another, usually precipitated by his comically inept attempts to court a woman. In turn, it became the seeming obligation of the more thoughtful Naqi to curb his cousin's worst instincts. The third season begins on a high note as Naqi is about to take delivery of his newly constructed house while Arastu readies for his wedding ceremony to be held there. Yet the final scene in the first episode sets the stage for a reorientation of the characters’ relationship and respective roles, as Arastu's wedding ceremony ends in disaster with Naqi's home collapsing under the weight of the guests. However, it is Naqi and not Arastu who is to blame for the collapse since he had insisted that the builder remove a load-bearing column to create a more impressive reception area. Viewers later learn that this design flaw also invalidated the insurance policy.

The second episode jumps ahead several months to just before Nawruz. Viewers are confronted by an unfamiliar Naqi, both in personality and appearance. He is suffering from a debilitating depression due to his joblessness and related financial woes. In fact, his wife's new catering business is the family's only source of income, though still not enough to pay for the house repairs. Huma's attempts to boost his confidence only result in his mood darkening. The mislabeled (and presumably domestically produced) dye that she buys to hide Naqi's graying hair turns him blond. She then encourages him to enter a masters-level national wrestling tournament, only for him to suffer a humiliating defeat to a competitor many years his senior in the televised final match.Footnote 41 Meanwhile, the fortunes of the other main characters all improve: Huma's business is quickly expanding with new clients; Naqi's sister is pregnant with her first child; and his brother-in-law, a forest ranger, gains national attention for saving an endangered Iranian cheetah from poachers. Perhaps most shocking is Arastu's turn of fortune, given previous understandings of the character. The tragicomic end to his wedding ceremony actually saved him from a “doomed” marriage as he later discovers his now ex-fiancee's hidden marital history and child. Moreover, he not only manages to trade in his ancient truck for a new eighteen-wheeler, but also becomes a successful international transit driver regularly hauling cargo to and from Europe. In fact, on one of his trips through Turkey, Arastu secretly marries.

The series makers depict Naqi as a man standing in place while the rest of the world rushes past. His situation would appear to be symbolic of the country's situation under the yoke of sanctions—one characterized by scarcity and economic contraction.Footnote 42 The fact that the protagonist is a God-fearing provincial (shahristānī) may further underline the country's dire economic situation for many urban, educated viewers who have held the (somewhat faulty) impression of their small town and village compatriots as the major support base for and beneficiary of the current regime. By contrast, Arastu and his newfound good fortune would seem to represent the potential transformation of Iran by way of “unfettered” (or Turkish-mediated) links to the global economy. In fact, Arastu's new clothes and attitude, symbolic of his upward mobility, literally makes him, like his Turkish soap opera “competitors,” into a walking billboard for the brands of multinational conglomerates [Figure 3]. Arastu's travels have also changed his speech patterns, now peppered with English words often in “unique” combinations; hence, his catchphrase in season three is bisyār lukshirī, or “very luxury,” which he uses to describe, among other things, the various gadgets and gifts that he has purchased while abroad. Finally, Arastu's connections to the world beyond the borders of an isolated Iran have blessed him, after many past failures, with an “exotic” Chinese wife: Cho Chung (Zhang Menghan). Interestingly, the setting that Arastu chooses for her introduction to Naqi and Huma is Tehran's Milad Tower, a vivid symbol of the modern, cosmopolitan city and the telecommunications hub tying it to the world beyond. Given the opposing directions in which the two cousins are seemingly headed in the first half of the season, it is perhaps unsurprising that they are on bad terms with one another during many of those episodes.

Figure 3: The newly made over Arastu wearing a jacket covered in brand names.

However, Capital does not quite land on either side of the officially claimed divide between the self-effacing values of the Islamic Revolution and the self-serving values of a neoliberal economic order. Thus, the two cousins do not remain at war but are in fact reconciled through the pressure of family elders. Viewers may consider this reconciliation to be inevitable. Indeed, the very inseparability of the cousins is emblematic of the paradox of attaining national prosperity outside a foreign- and especially Western-dominated global economy that the series explores. Moreover, Arastu's English serves more to amuse than impress viewers given his often trivial and ungrammatical use of it. Arastu's bizarre “Penglish” ironically draws into question his very conversion to a Western-oriented neoliberal ideology and the apparent threat of cultural “rootlessness” that accompanies it. Even Arastu's consumer behavior as a form of personal gratification is suspect. Viewers learn that most of his purchases abroad are meant for family members, instead of evidence of a growing individualism. His buying sprees even become a source of family melodrama, with Naqi at once contemptuous and envious of his cousin's newly acquired consumer tat and tastes.

Arastu's marriage to Cho Chung equally problematizes his ideological conversion. To be sure, the presence of a Chinese woman in Iran provides a natural opening for humorous cultural misunderstandings in a comedy series. However, Cho Chung's role in the narrative may also resonate with Iranian viewers for other reasons. More specifically, she stands in for China, which had after 2010 become Iran's economic lifeline as U.S. and E.U. pressure forced other nations to end or drastically cut back trade relations with Iran. Yet, China's entrenched position as Iran's dominant (or domineering) trade partner had generated serious concern among politicians and the public for the nation's subordination to Chinese interests. Members of Rouhani's cabinet, especially after the signing of the nuclear deal, would reveal to media outlets the humiliating concessions that China had secured from the previous administration in exchange for continued oil purchases.Footnote 43 Some viewers may thus interpret the news of their marriage as further evidence of Arastu's seduction by powerful foreign interests seeking to open up Iran both economically and culturally. However, the subsequent introduction of Cho Chung at least partly undermines this conclusion. She may be Chinese but she is also depicted as a convert to Islam as well as a fluent Persian speaker. Iranians have seemingly seduced the foreigner rather than the reverse. The character likewise complicates the accusation that Iranian critics and even some fans have leveled at Turkish soaps and other foreign satellite programs of exploiting highly impressionable Iranian viewers.Footnote 44 The series makers invite audiences to view her as a symbol of the resilience and attractions of Iranian culture and Islam.

Finally, the season climax involves Naqi's participation in an international masters-level wrestling competition in Tehran, after an injury to the Iranian champion and Naqi's bête noire. In a fantastical sequence at odds with the overarching realism of Capital, Naqi gains a measure of redemption (and a cash prize) by defeating in succession a Chinese, Russian, and American competitor to win the gold. Indeed, viewers may interpret his win as a national triumph against the foreign powers that were most responsible for inflicting or exploiting the crippling sanctions on Iran. They may also take Naqi's invocations of the eighth Shiʿi Imam Riza prior to his bouts as evidence of the victory of the spirit, embodied in believing Iranians, over the material, which even managed to lead astray some regime officials at the time.Footnote 45

Capital may pose quite an aggressive contrast, both thematically and stylistically, with the programs that Iranians watch on satellite television and the moral and cultural rootlessness that they supposedly propagate. However, those divergences do not necessarily indicate full convergence with the “official line” on satellite and sanctions.

Active Audiences and “Divergent” Pleasures

The popularity of Capital seemingly highlights the lingering unease that not only government authorities have had about Persian-language satellite networks but also ordinary Iranians. The drive to fill state television schedules with entertainments palatable to both censors and audiences springs from this unease. To be sure, Tanabandih and company were not the first to tap into Iranian viewers’ ambivalence for foreign-based satellite programming. Cyrus Zargar has pointed to the work of Mihran Mudiri, perhaps the most important comic presence on state television over the past ten years, as one critical voice taking on these offshore programs.Footnote 46 Zargar has suggested that Iranians’ relationship with the foreign and exile content beamed directly into their homes from overseas networks is rooted in unequal center-periphery relations. In these foreign-based media representations, Iran and Iranians would appear to be situated on the periphery of a Western-oriented global cultural, economic, and political order. However, Iranian viewers in Iran may also invert such representations of unequal relations by viewing the country as a cultural island whose morality and spirituality rooted in Islam and social institutions like the family are pitted against an atomized, technologized, and hedonistic world around it. The post-2010 nuclear sanctions perhaps made this “divide” between inside and outside even clearer for some. According to Zargar, Mudiri's depictions of appalled Iranians watching satellite programming challenge longstanding claims made by the Los Angeles-based opposition in particular that what was valuable about Iran now resides outside the country.Footnote 47 Nevertheless, those same viewers may still regularly tune into the latest installments of Turkish melodramas on satellite even as they delicately balance sentiments of aspiration and bemusement in their viewings.Footnote 48

Politicians and clerics’ panic about foreign satellite television programs in Iran has long been premised upon their straightforward ideological effect and the passivity of audiences in the face of enticing images flashing across their screens. Ironically, most academics writing about Iranian television have similarly treated the programming on state networks as propagandistic, sometimes subversive, but largely unambiguous in their content. Such scholarly accounts have also seldom credited viewers’ ability to have more complex and even contradictory perspectives on domestically produced programs. Yet, the popularity of Capital demonstrates the ability of Iranians, both on set and at home, to navigate between the absolutist visions of a neoliberal world order and an Islamic revolutionary one at a time of acute crisis. Zargar, for his part, has similarly argued that overly deterministic interpretations of Mudiri's programs as either serving or belying regime interests overlook their role as “. . .cultural artifacts still in production, commenting on a living Iran.”Footnote 49 Iranian audiences may simultaneously embrace the social realist depiction of the humble, pious Muslim family in Capital as well as the program's acknowledgment of the limitations of material deprivation and self-abnegation. Likewise, they may make fun of the ridiculous and empty-headed characters they find in Turkish soap operas while also enjoying those same characters’ “freedom” to have fun and engage in a transnational consumer culture. The idea of watching both satellite and state television with a variety of different objectives and dispositions only seems strange if one insists on the ideological rigidity of television programs and their audiences. In other words, both popular Iranian serials on state television and their viewers are likely doing far more than what critics and academics have often credited them for.

The revolutionary and war “propaganda” of the 1980s has in more recent times slowly given way to family-centered comedies and dramas on the Islamic Republic's television networks. These programs have faced formidable competition for viewers, especially from the highly polished foreign melodramas on offshore satellite networks. Iran's isolation under nuclear-related sanctions may have made these foreign programs and aspects of their characters’ lives more appealing to Iranian audiences. Yet, the competition between foreign and domestic television has not resembled a zero sum game in part because neither has been able to entirely satisfy those audiences. Iranians have thus watched Turkish melodramas and homegrown programs like Capital not merely to counter neoliberal or radical Shiʿi representations of the world but to complement them.