Introduction

In recent years, scholars of IR have been preoccupied with challenges to the ‘liberal international order’. Assessments abound. The erosion of Western dominance, the ascent of China, the impact of a revanchist Russia, to mention only a few. But few of these challenges have been more surprising or, in many eyes, more concerning, than the rise of the radical Right. Over the past decade, the transnational networks of the radical Right have made significant gains in Europe, North America, and beyond. Governments and political parties espousing avowedly ‘conservative’ foreign policies have also proliferated, often routinely mobilising the ideas and ideological repertoire of the radical Right to contest prevailing visions of the global order and undermine established forms of international governance.Footnote 1

The prominence of these ideas and movements demands engagement with the intellectual origins, inspirations, changing worldviews and past achievements of radical conservative forces in international relations. Yet, conservatism or right-wing thought seems to have no distinct place within the theories that have structured debates in International Relations (IR) since the end of the Second World War. In fact, unlike its sister discipline of Political Theory, IR is marked by a conspicuous lack of engagement with avowedly conservative ideas and theories.Footnote 2 This absence is not an oversight. It has a history and a politics – and both are essential for understanding the striking absence of radical conservative ideas in IR and the implications of that absence for the field's ability to engage the resurgence of those ideas today.

This article traces some of the ways that radical conservative thinking was ‘disciplined and narrated out of the mainstream of IR’.Footnote 3 Doing so requires challenging conventional narratives of the field's theoretical development and filling important gaps in its disciplinary history. For although they have almost completely disappeared from the field's historical memory, radical, or what we call ‘militant’, conservative ideas were in fact found across large parts of the study of postwar world politics. Often closely engaged with international security, geopolitics, and Cold War strategy, these conservative positions expressed scepticism or hostility towards liberal modernity, belief in intrinsic racial hierarchy, and convictions that global orders reflect or ought to reflect deep foundations in culture, tradition, and myth.

We seek to recover these forgotten positions by focusing on four influential conservative voices in American foreign policy and international affairs: Robert Strausz-Hupé, James Burnham, Stefan Possony, and Gerhart Niemeyer. These thinkers did not constitute a unified theoretical movement, but they were highly aware of each other's work, often knew each other personally, sometimes collaborated, and frequently supported the same political causes. Backed by philanthropic foundations, each engaged extensively in journalism and public debate, writing bestselling books and influential columns. They lectured frequently to the US military and war colleges, setting up training programmes based on their ideas. They held government positions or consultancies and advised political leaders and candidates, all the while holding influential academic positions in leading American universities. They also played notable roles in postwar discussions over the creation of a theory of international relations. And yet, significantly, all of them have been almost completely forgotten in accounts of those origins.Footnote 4

In the second part of the analysis, we argue that the near disappearance of these ideas and thinkers from the increasingly well-defined discipline of International Relations can be traced in part to the politics of postwar IR theory, and to activities of postwar thinkers we now call classical realists. As Nicolas Guilhot has shown, the development of postwar IR theory was no neutral enterprise.Footnote 5 It was marked instead by a ‘realist gambit’ – a self-conscious attempt to ‘invent’ IR theory and determine the analytic and political principles on which the emerging field would be constructed. Guilhot compellingly demonstrates that a key goal of this enterprise was to provide a bulwark against the emerging hegemony of American political ‘science’. Yet this was not their only ambition. We argue that a crucially overlooked consequence of the realist gambit was also to marginalise radical conservative ideas within the legitimate discourse of the field of IR.

Realist thinkers were not alone in this endeavour. The postwar social sciences saw sustained efforts to counter the influence of what Daniel Bell called the ‘radical Right’.Footnote 6 Driven by fears of militant anti-communism, these efforts also reflected the advances of the civil rights movement and similar campaigns across multiple academic disciplines and much of modern society to affirm liberal norms of human equality against the racial essentialism and hierarchies characteristic of radical right-wing thought. Postwar American IR developed in this wider context. Concerned that anti-communist and anti-liberal zeal posed tangible threats to peace and democracy, many of the emerging field's most prominent thinkers directly attacked militant conservatism's anti-liberal philosophy, foreign policy prescriptions, and racial essentialism. Informed by its aversion to this militant conservatism as well as by its more well-known suspicion towards Wilsonian liberalism, they also sought to produce an alternative, a fusion of liberalism and conservatism designed at least in part to combat the arguments and appeal of the radical Right – a position they called ‘realism’.

Our claim is not that we should ‘reinstate’ or carve a space for radical right-wing thought within the conceptual or normative tool box of the discipline, but rather that recovering this history challenges some of IR's most powerful and enduring narratives about its development, identity, and commitments – particularly the continuing tendency to find its origins in a defining battle between realism and liberalism. We argue that despite its near-canonical opposition to liberalism in disciplinary hagiography, realism in this period is best understood as part of a wider attempt to craft a ‘conservative liberalism’,Footnote 7 seeking not only to avoid what its advocates saw as the pitfalls of utopian liberalism, but also to meet the challenge of radical conservatism. The success and dominance of this oft-misunderstood fusion during the 1950s, 1960s, and beyond played a key role in narrating the radical Right out of the mainstream of IR. Coming to terms with this neglected chapter in the intellectual history of the discipline thus both contributes to our understanding of right-wing thought and draws attention to an underappreciated dimension of the realist tradition, revealing overlooked resources for reflecting on the nature of radical conservative attacks on liberal orders in contemporary politics and international relations.

Conservatism and militant conservatism

Conservatism is not a rigorously developed and cohesive school of thought but a constellation of ideas, attitudes, and thinkers revolving around a series of historically situated rejections of liberal and socialist ideas. As Karl Mannheim argues, conservatism ‘is a counter-movement, and this fact alone already makes it reflective: it is, after all a response, so to speak, to the “self-organization” and agglomeration of “progressive” elements in experience and thinking’.Footnote 8 Against the abstract, speculative tendencies of modern thought, conservatism emphasises the comforting immediacy of shared cultural conventions and self-evident truths. It affirms the importance of historical heritage, collective memory and the concrete, situated experience of one's particular environment as the main determinant of political thought and action.

Contrary to many critics, conservatism is not necessarily committed to maintaining the status quo. Rather, conservatism seeks to prevent the sort of abrupt and disruptive change sought by forces perceived to be of the left and destructive of what conservatives at the time want to preserve. It does this typically by insisting on the presence of forces – for example, nature, God, biology, history – deemed beyond human control, and which impose severe limitations on the perfectibility of the human condition. This preference for stability and continuity over disruptive change is often matched by support for more substantive political concepts such as hierarchy, elitism, religiosity, property rights, free enterprise, and state sovereignty.Footnote 9 However, the difficulty with trying to identify a more substantive ideational essence to conservatism is that such concepts are notoriously open to a wide variety of interpretations and configurations; they are also not exclusive to the ideological repertoire of the Right.Footnote 10 As Michael Freeden argues: ‘to ransack conservatism for the substantive core concepts and ideas located in rival progressive ideologies, such as liberty, reason, sociability, or welfare, is to look at the wrong place’.Footnote 11 For, apart from the morphological consistency provided by its core commitments to organic change and the randomness and uncontrollability of events and human behaviour, ‘conservative ideology can only display a substantive coherence that is contingent and time- and space-specific, because that coherence is created solely as a reflection of the substantive internal congruence of the rival ideological structures which the particular conservative discourse aims at rebutting’.Footnote 12

What we call militant conservatism or the radical Right in this study has its origins in an anti-Enlightenment current that is consciously traditionalist and ‘reactionary’, insofar as it emerged as a reaction to the breakdown in the sacred historical order thought to have been created and guided by an inexplicable Providence. However, it only came into its own as a distinct style of right-wing politics during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries as a response to the rise of socialism and the perceived failures of conventional conservatism and bourgeois society to deal with the challenges of mass liberal democracy. As Jerry Muller argues: ‘The radical conservative shares many of the concerns of more conventional conservatism, such as the need for institutional authority and continuity with the past, but believes that the processes characteristic of modernity have destroyed the valuable legacy of the past for the present.’Footnote 13 This leads to the conclusion that ‘a restoration of the virtues of the past’ requires abandoning the gradualist attitude of conventional conservatism in favour of a more militant, voluntarist, and programmatic approach that will command the loyalty of individuals and bind them together into an organic whole to a greater extent than existing institutions can be expected to do under present conditions of sociocultural decay.Footnote 14

The threshold delimiting where conventional conservatism ends and radical conservatism begins is often ambiguous, as is the relationship between ‘militant’ and ‘reactionary’ conservatism, not least because the relationship between tradition and authority determining this continuum of reaction can manifest itself in many different forms.Footnote 15 As George Nash has argued, however, in Cold War America it was marked by virulent anti-communism, the powerful influence of European émigré thinkers, and adoption of the label ‘conservatism’.Footnote 16 A particularly important platform for this confrontational style of right-wing politics was the influential magazine National Review. Founded in 1955 by the self-declared radical conservative William F. Buckley, the National Review was established with the aim of creating a new ‘movement conservatism’ that would take a decisive stand in what its Mission Statement described as the most ‘profound crisis’ of the twentieth century: ‘the conflict between the Social Engineers, who seek to adjust mankind to conform with scientific utopias, and the disciples of Truth, who defend the organic moral order’.Footnote 17 In this regard, Buckley emphasised, National Review was a reaction to the advances of organised labour, racial desegregation, women's emancipation, and the ‘satanic utopianism of communism’, as well as a response to the conformist conservatism of establishment Republicans:

National Review stands athwart history, yelling ‘Stop’, at a time when no one is inclined to do so, or to have much patience with those who so urge it. National Review is out of place, in the sense that the United Nations and the League of Women Voters and the New York Times and Henry Steele Commager are in place. It is out of place because, in its maturity, literate America rejected conservatism in favor of radical social experimentation. … Radical conservatives in this country have an interesting time of it, for when they are not being suppressed or mutilated by the Liberals, they are being ignored or humiliated by a great many of those of the well-fed Right, whose ignorance and amorality have never been exaggerated for the same reason that one cannot exaggerate infinity.Footnote 18

Preoccupations with the conflict between the United States (and the ‘West’) and the Soviet Union in the historiography of postwar IR have obscured the extent to which thinkers across the social sciences grappled with different expressions of this revolt from the intellectual right, and with the rise of more conspiratorial movements such as McCarthyism and the John Birch Society. Prominent sociologists like Daniel Bell, Talcott Parsons, and David Reisman saw in this new ‘radical Right’ (or what the historian Richard Hofstadter called the ‘paranoid style’ in American politics,Footnote 19 and Martin Seymour Lipsett and Earl Raab (1970) ‘the politics of unreason’)Footnote 20 one of the major social and political challenges of the era, reflecting deeper fractures in the fabric of American society.Footnote 21

These concerns were particularly intense in the sphere of international politics and foreign policy. Extreme assessments of the Soviet threat, the weakness of American responses to it, and the need for drastic remedies were staples of the radical Right. Buckley, for instance, speculated that American conservatives might need to ‘be willing to accept totalitarianism on these shores for the duration’ of the Cold War.Footnote 22 Indeed, many feared that it was in international affairs, and in the military itself, that what Time magazine labelled the ‘ultras’ of the radical Right had their most worrying influence. In the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, for instance, Gene Lyons and Louis Morton outlined the influence of a radical Right ‘School for Strategy’ that had since the 1950s brought together thinkers from the Foreign Policy Research Institute, the Institute of American Strategy, and various parts of the US military to promote a highly conflictual vision of the Cold War.Footnote 23 In Lyons and Morton's view, it was a vision that would generate ‘a wide network of secrecy and security in government operations, a “cold war” orientation in our schools and universities – in short, a stunting of pluralism, a curtailment of individual liberties, and a weakening of politically responsible government’.Footnote 24 Concerns over the influence of ‘ultra’ conservatism in the military even led Senator William Fulbright to issue a famous memo in warning, with the Bulletin article attached.Footnote 25

The thinkers that we discuss in the following sections – Robert Strausz-Hupé, James Burnham, Stefan Possony, and Gerhart Niemeyer – were at the forefront of those foreign policy debates. Each had wide influence on the intellectual coalescence of the American conservative movement throughout the 1950s and 1960s and beyond.Footnote 26 Although their positions sometimes differed, they shared a political sensibility heavily indebted to Europe and shaped by profound anxieties over the erosion of traditional communities, racial hierarchies, and sources of authority. Unlike their later ‘neoconservative’ counterparts, these thinkers did not fight communism in the name of the supreme value of American democracy and market capitalism, but rather as the arch enemy of the ‘Western religious heritage, of historic nationalities, and metaphysical as well as political freedoms’.Footnote 27 In their eyes, the isolationist attitudes that defined the foreign policy discourses of the anti-New Deal Right during the interwar period had been made redundant by the urgency and scale of the ‘internationalized civil war’ that had been destroying Western civilisation from within since the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. If the Right were to become a major force in this fast-changing political environment, it would have to adopt a much more interventionist stance towards public and international affairs. For to be a conservative in this new age of mass political ideology was as much about thwarting the transformative ambitions of the Left as it was about creating a new world order worth conserving.

Robert Strausz-Hupé: Geopolitics

In terms of intellectual and policy influence, Robert Strausz-Hupé was arguably one of the most successful IR scholars of his generation.Footnote 28 Having immigrated to the United States from his native Austria in 1923, he worked on Wall Street and as editor of Current History Magazine before joining the University of Pennsylvania's political science department in 1940. Author of more than a dozen books, including (with Possony) a prominent early textbook on international politics,Footnote 29 he was also, with Niemeyer, part of a 1953 Council on Foreign Relations study group on the foundations of IR theory.Footnote 30 In 1955, with financial assistance from the conservative Richardson Foundation, he established the Foreign Policy Research Institute (FPRI) at the University of Pennsylvania and founded its journal, Orbis. The FPRI quickly developed close ties to the military, particularly through the highly conservative Institute for American Strategy – activities that prompted their denunciation by Fulbright as reactionary threats to American democracy. Strausz-Hupé was also a foreign policy advisor to the maverick Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater in 1964Footnote 31 and, less prominently, to Richard Nixon in 1968. He subsequently served as US Ambassador to NATO, Sri Lanka, Belgium, Sweden, and Turkey.

To the extent that Strausz-Hupé is remembered in IR today, it is likely through his complex association with geopolitics – and it is here that we can begin to unravel his connections to the radical Right. Geopolitical ideas and reactionary politics share a long, if not necessarily identical, history. Via nineteenth-century theorists like Friedrich Ratzel or Rudolph Kjellen, geopolitics became linked to organic state theories and global social Darwinism. A nearly biologically imperative expansionism, racial or societal international hierarchy, and inevitable conflict became its bywords. Subsequently, in the hands of radical conservative thinkers such as Oswald Spengler, Moeller van den Bruck, and Carl Schmitt, this ‘German’ geopolitics also took a more political-cultural guise, with culture, race, and myth at its core, and the meaning and fate of the West as its most important stake.Footnote 32 Spengler offered the gloomy prognosis of the West as an aged and increasingly decrepit liberal ‘Civilisation’ in terminal decline. Moeller, by contrast, reversed Spengler's diagnosis, arguing that Germany and Russia were in fact young and vibrant ‘Cultures’ that could escape the yoke of increasingly decadent liberal Anglo-American ‘Civilisations’ and flourish in a continental partnership that would dominate the future. Karl Haushofer, the most practically influential of these ‘Generals and Geographers’,Footnote 33 held that Eurasian land power was the geographic pivot of history, and viewed the ‘telluric’ Eurasian land powers as inescapably at odds with the ‘thalassocratic’ Anglo-American sea powers.

In this European (and especially German) setting, geopolitics had profoundly conservative, often reactionary entailments. Many of its proponents virulently rejected liberal visions of politics and were particularly hostile towards the United States and Britain. Advocating an arch-power political geographic determinism opposed to the idea of a ‘Euro-Atlantic’ partnership,Footnote 34 this ‘cultural’ geopolitics cast Europe as the ‘true’ West – an alternative to the Atlantic World, not a part of it.

During and after the war, Strausz-Hupé and other European émigrés, as well as American thinkers such as Edmund Walsh (founder of Georgetown University's School of Foreign Service)Footnote 35 undertook a dual mission: first, instructing Americans in the power of geopolitics while avoiding its disastrous ‘German’ formulations; and second, providing a reading of the Cold War steeped in the wider geopolitical critique of liberal modernity.Footnote 36 These thinkers often used the language of analytic objectivity to justify a particularly blunt form of power politics, but they married this ‘science’ with readings of political modernity that connected their vision of the Cold War to other counter-Enlightenment currents on the American Right.

Strausz-Hupé's first major contribution in this direction was a scholarly but highly polemical analysis treating German geopolitik as a dogmatic rationalisation of the Nazis’ relentless will to conquest.Footnote 37 Whereas statesmen had previously used geopolitics to pursue national ends and achieve the balance of power, the Nazis used geopolitik to destroy the balance of power and wipe out all commitments to the shared Christian heritage of Western civilisation: ‘shorn of its learned trappings’, he argued, geopolitik was ‘the doctrine of nihilism pure and simple applied to international relations … the antithesis of the principles of civilized order for which Western man has struggled. It expresses the Asiatic aversion to fixed boundaries …’.Footnote 38

As this statement suggests, Strausz-Hupé's anxieties over the geopolitical nihilism of Nazi Germany remained rooted in the racialised categories and assumptions of Europe's colonial legacy.Footnote 39 Moreover, despite his criticisms of geopolitik, he endorsed its neo-Darwinian vision of international relations as an everlasting struggle for world domination and its view that the future lay in the establishment of regional systems, each clustered around a hegemonic great power. Geography and technological mastery, he averred, had designated America the new epicentre of the West, a ‘congeries of all the races of Europe’ that would use its unprecedented military capabilities to create a stable world order out of the defeat of the Axis Powers.Footnote 40

The success of this new trans-Atlanticism depended on the resolve and ability of the United States to lead the fight against communism and create an order under which a federated Europe could be subordinated within NATO.Footnote 41 Yet the West, and Europe in particular, confronted profound barriers in this task – challenges that were primarily philosophical and psychological rather than military or technological. Like many émigré scholars, Strausz-Hupé lamented the degeneracy of European culture where the forces of secularism, relativism, and individualism had resulted in the ‘alienation of man from vital beliefs, alienation of social groups from society, and alienation of whole peoples from the Western community’.Footnote 42

These weaknesses contributed to the West's fundamental misunderstanding of the Cold War. Where others saw pragmatic compromises and contradictions in communist foreign policies, Strausz-Hupé saw a coherent strategy of ‘protracted conflict’Footnote 43 rooted in the revolutionary logic of Marxist-Leninist philosophy. Yet to the Western liberal mind, he argued, ‘conflict as a conscious, managed struggle, the goals of which are mutually incompatible, is an unpalatable idea’.Footnote 44 Liberals failed to recognise that periods of ‘peaceful, competitive “coexistence”’ or even retrenchment were as much a part of the communist war plan against the Free World as periods of aggressive expansion. They clung to the naïve and dangerous belief that communism could be contained or reformed when, in reality, ‘Conflict to the bitter end is the stuff from which communism draws its sustenance.’Footnote 45

Strausz-Hupé thus suggested abandoning containment and using superior military power to ‘rollback’ and ultimately destroy communism. Developing a military posture and strategic doctrine that maintained nuclear deterrence, but allowed America to fight limited wars and prepare for the possibility of a total nuclear war, was essential if it was to take the initiative and avoid the perils of attrition. A key obstacle to this approach was the Soviet Union's ability to exploit liberalism's values and weaknesses by using free speech and civil rights activism to cultivate feelings of culpability and foment hostility to Cold War militarism across the Atlantic.Footnote 46 At the same time, the relaxation of tensions under Eisenhower allowed the Soviet Union to displace the conflict into a ‘backward’ and opportunistic Third World, where America was being ‘blackmailed’ and acted as ‘a whipping boy to atone for the dislocations caused by Westernization’.Footnote 47 The Cold War, in short, was the expression of a deeper civilisational and metaphysical crisis – a spiritual and ideological struggle that both liberalism and containment-focused realists failed to understand and threatened to lose.

James Burnham: Liberalism and the ‘suicide of the West’

Strausz-Hupé's power politics, aggressive anti-communism, and attacks on liberal decadence were echoed by James Burnham. A philosophy professor at New York University from 1929 to 1953, Burnham lectured frequently on international affairs at the Naval War College, the National War College and the Johns Hopkins School for Advanced International Studies during the 1950s and 1960s. Although relatively unknown in IR circles today, he was among the most influential ‘geopolitically minded’ public intellectuals of the American Right from the 1940s to the 1970s.Footnote 48 A co-editor of Buckley's National Review, he contributed a weekly foreign policy column (tellingly renamed ‘Protracted Conflict’ in 1970), and penned a number of bestselling books on politics and international relations

Burnham began his political life on the radical Left as one of Trotsky's leading American disciples. After breaking with Marxism, he achieved international recognition with his bestselling book The Managerial Revolution.Footnote 49 Arguing that the means of production had been absorbed by new administrative instruments of elite domination, Burnham held that the coming order would be neither the old bourgeois society of capitalism nor the new classless society of socialism but a world-conquering managerial technocracy run by a New Class of administrators, engineers, and educators wielding power through the interpretation of cultural symbols and the manipulation of the state-authorised mechanisms of mass organisation and economic redistribution.

Burnham adopted a particularly stark power politics and aggressive foreign policy position. In The Machiavellians, he tapped the political theories of Sorel, Mosca, Michels, and Pareto to argue that all societies are by nature oligarchical, ruled through force and fraud, and held together through the interplay of cultural conventions, myths, and rationality. Political leaders had to understand that ‘The political life of the masses and the cohesion of society demand the acceptance of myths. A scientific attitude toward society does not permit the belief in the truth of the myths. But the leaders must profess, indeed foster, belief in the myths or the fabric of society will crack and they will be overthrown. In short, the leaders, if they themselves are scientific, must lie.’Footnote 50 Democracy was one such myth, designed and propagated by elites to sustain their rule under secular modernity.Footnote 51 Against the ‘liberal consensus’, he exalted a conservatism of hierarchical structures, cultural renewal, and the primacy of patriotism over internationalism.

These ideas took an explicitly geopolitical cast in the spring of 1944 as Burnham worked on a secret study commissioned by the Office of Strategic Services to help prepare the US delegation to the Yalta Conference. Expanded and published three years later as The Struggle for the World, the book claimed that the Soviet Union had emerged as the first great Heartland power and sought to educate the American public in the geopolitical challenges ahead. Like Strausz-Hupé, Burnham insisted that the Soviet Union was driven by its revolutionary ideology to seek continuous expansion. The United States, having made ‘the irreversible jump into world affairs’ during the first half of the twentieth century, could longer withdraw into isolation.Footnote 52 The only alternative to a ‘communist World Empire’ was an American Empire established through a network of hegemonic alliances and colonial and neocolonial relationships, ‘which will be, if not literally world-wide in formal boundaries, capable of exercising decisive world control’.Footnote 53

A leading conservative critic of containment, Burnham saw the ‘realism’ of Kennan and the Truman administration as a delusional form of appeasement.Footnote 54 In its place, he advocated a policy of immediate confrontation aimed not merely at containing communism but at overthrowing Soviet client governments in Eastern Europe via intense political warfare, auxiliary military actions and, quite possibly, a full-scale war.Footnote 55 These criticisms of realist foreign policy prescriptions continued in debates over the Vietnam War, where Burnham repeatedly attacked what he called the ‘Kennan-de Gaulle-Morgenthau-Lippmann approach’Footnote 56 for over-emphasising the nationalist dimension of the Cold War at the expense of its more fundamental counter-revolutionary character. Although he conceded that realists made a ‘plausible, seemingly hard-headed strategic’ analysis, they ended at the same place as pacifists, defeatists, and revolutionaries – their ‘superficial and mechanistic idea of the national interest’ failed to grasp the broader geopolitical and metaphysical consequences of a withdrawal that would lead to the communist takeover of the entire Asian continent, leaving the US with only the ‘inflexible nuclear deterrent that Professor Morgenthau, like so many other withdrawers, has ruled out under the Better Red than Dead axiom’.Footnote 57 Entering the war may have been a strategic mistake, he admitted, but it had now become America's ultimate ‘test of will’. An unapologetic defender of imperialism, he lamented that the West had been ‘“drugged” by the “myth” that it was “always just … for Indonesians to throw out the Dutch, Indians the British, Indochinese the French, dark men the white men, no matter for what purpose, no by whom led, no matter the state of development, nor the consequences to the local people and economy, nor the effect on world strategic relations”’.Footnote 58

Despite Burnham's renunciation of Marxian theories of universal history, a holistic approach to social theory remained a defining feature of his thinking. Like Strausz-Hupé, he saw the Cold War as geopolitical and metaphysical, and grew ever more certain that America's liberal philosophical and cultural commitments conflicted with the sacrifices needed for its survival. As he argued in The Suicide of the West:

Modern liberalism does not offer ordinary men compelling motives for personal suffering, sacrifice and death. There is no tragic dimension in its picture of the good life. Men became willing to endure, sacrifice, and die for God, for family, king, honor, country, from a sense of absolute duty or an exalted vision of the meaning of history …. And it is precisely these ideas and institutions that liberalism has criticized, attacked, and in part overthrown as superstitious, archaic, reactionary, and irrational. In their place liberalism proposes a set of pale and bloodless abstractions – pale and bloodless for the very reason that they have no roots in the past, in deep feeling and in suffering. Except for mercenaries, saints, and neurotics, no one is willing to sacrifice and die for progressive education, medicare, humanity in the abstract, the United Nations, and a ten percent rise in social security payments.Footnote 59

Burnham's critique of liberalism was foundational. Incapable of understanding the Machiavellian paradoxes and brutal realities of politics, liberalism's rise corresponded to the decline of the West. Most liberals were ‘foxes rather than lions’, unable to see that politics was a messy, complex, and historically contingent sphere of human activity defined by disagreement, conflicts, unequal distributions of power, and the inevitable presence of cruelty and violence.Footnote 60 In response, as his allusions to lions and foxes illustrate, Burnham proposed a ‘Machiavellian’ synthesis of realpolitik and cultural metaphysics. This did not make him a ‘realist’ in the sense that the word was increasingly coming to be defined. Indeed, as we will show, it made him a prime opponent of those who claimed the title.

Stefan Possony: Race, intellect, and global order

Stefan Possony played an important role in conservative foreign policy debates for nearly half a century. Also originally from Austria, Possony was a prolific strategic analyst and long-standing collaborator of Strausz-Hupé. After arriving in the United States in 1940, he held research positions at Princeton's Institute for Advanced Study, the Psychological Warfare Department at the Office of Naval Intelligence, and the Pentagon's directorate of intelligence,Footnote 61 as well as teaching strategy and geopolitics at Georgetown. In 1961, he became Senior Fellow and Director of International Studies at the Hoover Institute at Stanford, served as a foreign policy advisor to Goldwater's presidential campaign, advocated an offensive ‘forward strategy’ in the Vietnam war, and became an influential advocate for the Strategic Defense Initiative undertaken by President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s.

Again, however, there is more to Possony's political vision than strident anti-communism and power politics. He was also deeply interested in racial hierarchy; in fact, racial geopolitics was central to his vision of international order. These convictions are clear in the tellingly entitled Geography of the Intellect he co-authored with Nathaniel Weyl.Footnote 62 Published with the highly conservative house Regnery, the book sought to demonstrate the racial hierarchy and geographic distribution of intellectual abilities and their implications for foreign policy. World power and historic progress depended on racially determined mental capacities and the ability of an elite – a ‘creative element’ – to influence a society's direction. Their survey of the ‘historic record’ concluded that intelligence is directly connected to the ‘comparative mental abilities’ of different races, and that ‘Those people who have accounted for the large preponderance of creative intellectual achievement since the Middle Ages are within the Western political orbit’,Footnote 63 a fact that accounted for the West's current geopolitical dominance.

However, this situation was unlikely to continue without radical change. Technological advancement and demographic dynamics allowed the less able to out-reproduce the elites, threatening the Western order domestically and internationally. Echoing Spengler, Weyl and Possony held that

As societies reach the peaks of civilization and material progress they face the threat of application of a pseudo-egalitarian ideology to political, social and economic life – in the interests of the immediate advantage of the masses who, for political reasons are told that if all men are equal in capacity, all should be equally rewarded. The resources of the society will be thus increasingly dedicated to the provision of pane et circenses – either in their Roman or modern form. Simultaneously, excellence is downgraded and mediocrity must fill the resulting gap. As the spiritual and material rewards of the creative element are whittled away, the yeast of the society is removed and stagnation results.Footnote 64

Liberal commitments to equality thus led not to progress and greater democracy, but to dangerous decline demanding radical remedies: ‘The political and social effects of population trends which reduce the inherited intellectual potential of the human species’ they warned, ‘must be viewed with profound misgivings. A democracy of the unfit is more likely to choose monsters for its rulers than a democracy of the fit. As the level of brain-power declines, we can expect that even the affluent nations may become, to an increasing extent, the dupes of demagogues and scoundrels.’Footnote 65 A partial response lay in selective genetic reproduction. Following Hermann J. Muller's ‘positive eugenics’, they suggest that via artificial insemination ‘Women who are unable to have children by their husbands, and married couples who wish to have at least one exceptional child, could resort to germinal selection of this sort. In this way, a small minority of the female population might multiply the production of genius several fold.’Footnote 66

At the international level, intellectual inequalities divided the world into distinct racially defined hierarchies, with clear policy implications. Like Burnham and Strausz-Hupé, they held that American aid policies and support for decolonisation, while laudable in intent, were disastrously misguided. ‘The root of these erroneous politics and self-defeating procedures’, they declared, ‘is the assumption that men, classes and races are equal in capacity and that human resources can be stepped up to any level by education. In Africa and the Middle East, with the pious purpose of destroying colonialism, we have unleashed the forces of savage race and class warfare. We have forced the emigration and expulsion of the European elite, which is in fact virtually the only elite, and by doing this we have condemned the area to a swift regression to chaos and barbarism’.Footnote 67

Weyl and Possony also mobilised another classic reactionary trope: that the West's decline was abetted by the ‘treason of the scholars’.Footnote 68 Liberal intellectuals set themselves up as the ‘self-appointed champion of the rights of the proletariat or “the common people”’, spreading specious egalitarian ideals and sowing envy, anxiety, dissent, and disloyalty – a ‘process of spiritual corrosion’Footnote 69 – among the masses. This existential threat required radical action: ‘The danger is great and the time is short’, they aver, ‘for the healthy forces in the American community to reassert themselves. A prerequisite for such a national resurrection is that the pseudo-intelligentsia be supplanted by a genuine creative minority’Footnote 70 that will stem the rise of ‘mediocrity’, unjustified anxiety, resentment, and envy, and stave off the intellectual ‘aristocracide’ threatened by mass society and democratic politics.

Gerhart Niemeyer: From international law to tradition

If the names of Strausz-Hupé, Burnham, and Possony may still ring distant bells among IR scholars and strategists today, Gerhart Niemeyer is almost wholly forgotten. Yet he, too, provides important insights into militant conservatism and the study of world politics. A native of Essen, Germany, Niemeyer like Burnham began his career on the left as a student of the social democratic lawyer Hermann Heller. He emigrated to the United States via Spain in 1937, teaching international law at Princeton and elsewhere before joining the State Department in 1950 and spending three years as a specialist on foreign affairs and United Nations policy. After two years as an analyst at the Council of Foreign Relations, he spent the next four decades as Professor of Government at Notre Dame University.

Niemeyer's 1941 book Law Without Force was a prominent part of postwar attempts to relate international law to power politics.Footnote 71 Heavily influenced by Heller's robust conception of state sovereigntyFootnote 72 and his lament over the politically naïve legalism of the Weimar left, Niemeyer argued that the ‘unlawfulness of contemporary international reality’ could not be blamed exclusively on the evils of certain political regimes but also reflected the unrealistic nature of modern international law.Footnote 73 The rise of liberalism during the nineteenth century had transformed international law into a mere instrument for managing the common affairs of the bourgeoisie and its ideal of an interdependent global society of profit-seeking individuals. But the rise of authoritarianism and the assimilation of individual and group interests to those of predatory nationalist objectives meant that liberal international legal norms had become completely obsolete.Footnote 74 Convinced that international order through law is a precondition for the preservation of culture, Niemeyer asserted the need for a ‘renovation of international law’ on a new functional basis reflecting the secularised, fragmented nature of modernity itself.

Niemeyer moved away from international law as the Cold War intensified, and his presence in IR faded.Footnote 75 But he hardly withdrew from either scholarship or politics. From the mid-1950s, he became in the eyes of one admirer ‘one of the most important Conservative thinkers in the United States’, sharing a ‘decades-long friendship with William F. Buckley’ that included four years as a contributor to the National Review.Footnote 76 Nor did Niemeyer turn away from international politics. Instead, he carved out a role as an expert on Communist thought, Soviet politics and foreign policy, and was ‘commissioned by Congress to write The Communist Ideology which was widely circulated in 1959–60’.Footnote 77 Like Strausz-Hupé and Possony, he worked as foreign policy advisor on the Goldwater campaign, serving subsequently as a member of the Republican National Committee's task force on foreign policy from 1965 to 1968.

Niemeyer was the most self-consciously philosophical of the thinkers considered here. Influenced by Eric Voegelin, he became a prominent ‘traditionalist’ during his long career at Notre Dame. Indeed, if a key claim of postwar conservatism was that ‘ideas have consequences’,Footnote 78 Niemeyer took to this conviction to great lengths. Political modernity, he argued, is a uniquely ‘ideocratic’ epoch where dominant ideologies strive for new certainties in order to remake the world, a movement that Voeglin called ‘political gnosticism’.Footnote 79 The result is a world dominated by ruthlessness, absolutism, and intolerance in which ‘logical murders’ and ‘logical crimes’, not atavistic hatred or traditional rivalries, made the twentieth century ‘one of the worst in human history’.

These convictions led to a particularly radical vision of the Cold War that re-articulated Niemeyer's earlier admonitions against the naive legalism of liberal thought in a more explicitly conservative metaphysical register. Liberals naively misunderstood the Soviet Union, which was not simply a great power adversary but an implacable enemy driven by gnostic desires of the ‘Communist mind’ – a nihilistic and pathological product of modernity.Footnote 80 As a result ‘we, who have to live in the twentieth century, have come to fear Liberalism as superficial, ignorant of mankind's demonic possibilities, given to mistaken judgments of historical forces, untrustworthy in its complacency’.Footnote 81 ‘Today’, he concluded, ‘the leading elements of our culture have come to the end of the tether. This is what we mean when speaking of “democratic disorder”. The Christian capital has been used up in the hearts and minds of those who have discarded its regenerating faith. The Enlightenment's vision of a brave new world is known to have been a fata morgana. Where once there seemed to be something of great promise, there now is nothing.’Footnote 82

The solution to this ‘malady of a spiritual “dead end”’ lay in a ‘mystical’ awakeningFootnote 83 that recognised the indispensability of mystery and myth in political life. For Niemeyer, political orders rest on a matrix of ‘customs, habits, prejudices’ underpinned by foundational myths. ‘If it were not for the myth’, these relations would ‘atrophy’ and ‘in place of familiarity and confident communication a universal assumption of hostility would arise’.Footnote 84 Only a ‘publicly shared theology or philosophy, a recognized view of what is man, society, nature and the meaning of life’Footnote 85 grounded in deeply inherited mores and values underpinned by Christianity could sufficiently support limited government and responsible political action. Failing this, the alternatives lay in an empty but crusading universalism of utopian (‘human rights’) liberalism, the facile and ineffectual vacillations of liberal relativism, the victory of Communist nihilism, or the violence of an unconstrained modern will to power.Footnote 86

Capturing conservatism: Realism and militant conservatism

These four thinkers demonstrate the breadth of militant conservative visions of international politics during the postwar era. Their geopolitical ‘realism’ reflected much more than a fixation on space, resources, and national power: it was tied to a narrative of the ‘crisis of man’,Footnote 87 and a recognisably reactionary critique of liberal modernity. Casting the Cold War in metaphysical terms, they saw the USSR as an extreme embodiment of the pathologies of political modernity demanding radical responses. Failing this, modern liberalism's weakness and decadence would lead to the destruction of the West. None of these thinkers were anti-democrats in the traditional authoritarian mold. But they all expressed grave misgivings about democracy and were deeply critical of liberal modernism. Their arch-power politics and aggressive policy prescriptions were embedded in these convictions.

Militant conservatism was never a dominant force in philosophy or politics in the 1950s and 1960s, however its support for military confrontation, ‘rollback’, and nuclear adventurism (not to mention at least partial sympathy towards McCarthyism) were seen by many as at least as worrying as any residual liberal ‘idealism’ in America's political culture and foreign policy. As Arthur Schlesinger Jr put it in a letter urging Hans Morgenthau to become a member of Americans for Democratic Action's Committee on Foreign Affairs (which he accepted): ‘Each passing day gives increasing evidence of the need for strong, vigorous leadership if American liberalism is to resist the trend toward reaction, and to formulate the policies and programs to meet today's needs in national and international affairs.’Footnote 88

The nascent field of IR was not always at the forefront of attempts to critically engage militant conservatism, but some of the field's most important early thinkers were keenly aware of the challenge and systematically attacked militant conservatism's ‘Machiavellian’ politics and geopolitical theorising. Even more importantly from the perspective of IR theory, they sought to mobilise conservative insights to develop a more robust liberalism capable of withstanding ‘pseudo-conservative’ attacks – a position that became a key part of realism.

Realism and realpolitik: ‘It is a dangerous thing to be a Machiavelli’

As we have seen, a vision of ‘Machiavellian’ politics was central to key strands of militant conservatism and its claims to political realism. These claims were explicitly denied by the most prominent realists of the time. As early as 1945, Morgenthau argued that the challenges facing realistic thinking in the postwar era lay not just in America's ‘Idealist’ disregard of power, but in the influence of disappointed idealists on the left who had become cynical power-politicians.Footnote 89 Whereas writers like himself had once been termed ‘cynics’ and ‘realists’ by the ‘perfectionist’ advocates of the League of Nations and Wilsonian internationalism, Morgenthau noted, the erstwhile perfectionists now moved ‘to the right and took the position the cynics seemingly had held before’.Footnote 90 Rather than adopting a responsible realism, these disillusioned perfectionists went to the opposite extreme, glorifying power as absolutely as they had once opposed it. ‘Having been late in discovering the phenomenon of power’, he argued, ‘they cannot get over the shock of recognition. In essence they are still utopians; only their utopianism is no longer of Wilsonian vintage, but has a strong Machiavellian flavor.’Footnote 91

As a result, Morgenthau continued, while he had long stressed the importance of power politics, it was now necessary to oppose the advocates of cynical realpolitik. In this strangely reversed landscape, it was the responsibility of realists to defend the indispensability of perfectionist insights, holding ‘as they have always done, that whereas international politics cannot be understood without taking into consideration the struggle for power, it cannot be understood by considerations of power alone’. If opposition to this new Machiavellianism resulted in him now being called a ‘perfectionist’, he concluded, ‘I do not mind being called a perfectionist today any more than I minded being called a cynic fifteen years ago.’Footnote 92

Morgenthau avoided naming names, though his focus on Machiavelli and lapsed leftists likely made his targets clear enough at the time.Footnote 93 Niebuhr had no such qualms. In a review of Burnham's The Machiavellians tellingly entitled ‘A Study in Cynicism’, he echoed Morgenthau's critique. Having discovered the existence of power and immorality in politics, Niebuhr argued, Burnham nonetheless failed the test of a ‘proper realism’. Instead, his ‘cynicism has become so obsessed with the dishonesty of human behavior, particularly the dishonesty of political leaders, that it proceeds to disavow all normative principle of political life’. ‘This’, he noted dryly, ‘is what Mr. Burnham calls a scientific politics’,Footnote 94 but the result is a ‘doctrine of total depravity. One may question whether a cynical reaction to the moral sentimentality of our culture is much more mature than the sentimentality.’ Whatever Burnham and other realpolitikers on the Right might claim, Niebuhr and Morgenthau declared them dangerously disillusioned idealists, not realists.Footnote 95

Realism contra geopolitics

Just as realists disputed the ‘Machiavellians’ claim to realism, so, too, they challenged their geopolitical theory. Although no realist discounted the significance of geography and its relationship to other elements of national power, realism's most significant figures were united in dismissing what they portrayed as the naive and dangerous power politics of the geopoliticians. On this theme Morgenthau took Burnham as his specific target, arguing in Politics Among Nations that his geopolitics was ‘a pseudoscience erecting the factor of geography into an absolute that is supposed to determine the power, and hence the fate, of nations’.Footnote 96 Geography, he acknowledged, could give ‘one aspect of the reality of national power’ but in the hands of those such as Burnham it amounted to a narrow ‘distortion’, especially when fused with virulent nationalism, as it so often was. In these debates, ‘geopolitics’ was not simply an analytic concept: it was infused with connections to a dangerous militant conservatism.Footnote 97

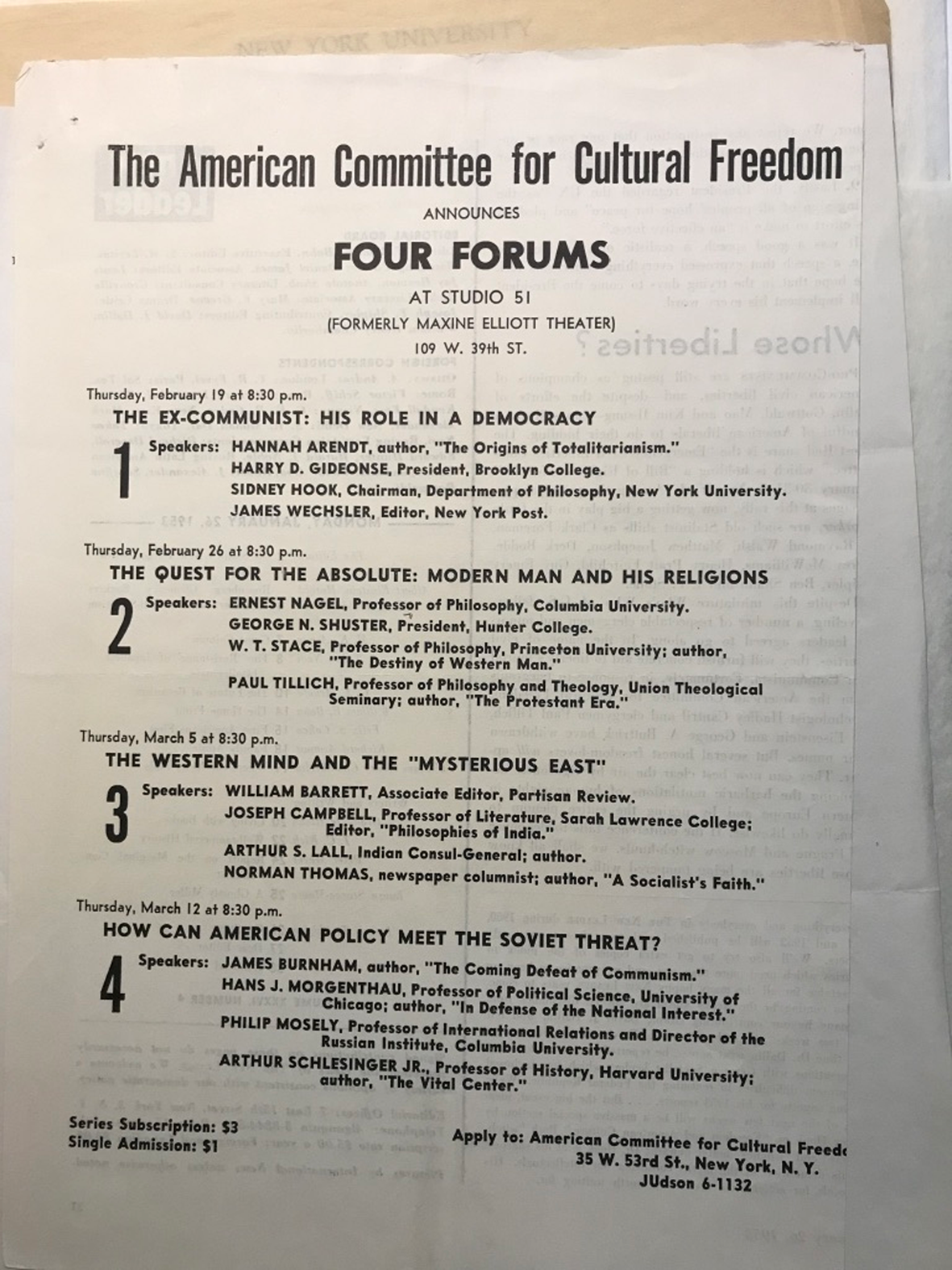

There were, of course, much more than theoretical issues at stake. Realists and their liberal-realist allies such as Schlesinger were concerned to counter attacks on containment and calls for ‘rollback’ and preventative war (see Figure 1). To Kenneth Thompson, the fusion of cynicism and geopolitics animating Burnham's interpretation of the Cold War represented dangerous ideological oversimplifications rather than realistic responses to complex problems.Footnote 98 In a review of The Struggle for the World, Schlesinger concurred, noting that although Burnham's analysis was superior to ‘the confused and messy arguments of the appeasers’, its reduction of Soviet foreign policy to a deterministic synthesis of geography and Marxist ideology disregarded the possibility that skillful Western diplomacy could steer the USSR towards a ‘minimum’ geographical-ideological position.Footnote 99 Six years later, assessing Containment or Liberation?, he was less restrained, charging that while the book had a ‘superficial thrust and plausibility … a quick examination shows it to be a careless and hasty job, filled with confusion, contradictions, ignorance and misrepresentation’.Footnote 100 Like many, Schlesinger was particularly troubled by Burnham's conclusion that the liberation of Central and Eastern Europe from communism could only be achieved through a decisive military campaign, a conclusion that flowed from his dangerous fusion of cynical power politics and deterministic geopolitics.

Figure 1. Foreign policy debates involving Burnham, Morgenthau, and Schelsinger organised by the American Committee for Cultural Freedom.

Source: Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr papers. Archives Division, New York Public Library. Box 21, File C.

In sum, for a wide range of prominent realists and realist-inclined liberals, the ‘theory’ of international politics and ‘protracted conflict’ propounded by militant conservatives lacked both analytic cogency and political responsibility. Neither ‘Machiavellian’ realpolitik nor geopolitical power politics was sufficient to qualify as political realism; on the contrary, they represented disillusioned perfectionism, naïve cynicism, bad metaphysics, excessive anti-modernism, and spurious scientism.

Realism, conservatism, and liberalism

The realist thinkers we have been considering were intimately familiar with radical conservative critiques of modernity and liberalism.Footnote 101 They, too, identified dangerous and destructive dynamics in modern liberal thought and socioeconomic organisation: concerns over mass media, culture, and society, along with worries that modern industrial societies generated anomie, ennui, and insecurity are replete in their writings of the time.Footnote 102 However, while militant conservatives claimed these dynamics required a movement against liberalism, postwar realists and like-minded liberals pursued an alternative of strengthening liberalism by incorporating some conservative insights concerning the limits of progressive politics, while challenging the radical Right's claim be a legitimate brand of conservatism, casting it instead as an ill-adjusted form of ‘pseudo-conservatism’.

Niebuhr was at the forefront of these endeavours to reorient progressive liberalism and pragmatism (to which he was once attracted) and show the value of a liberal politics shorn of its ‘utopian’ elements. The answer, as Richard Pells observes, was for liberalism to ‘become authentically conservative’ in order to combat ‘the “pseudo-conservatism” of the McCarthyites’.Footnote 103 Or, as Eric Goldman put it, in the late 1940s, this form of liberalism gradually ‘turned into a form of conservatism’ as ‘liberal intellectuals – Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr and Reinhold Niebuhr most prominently – began to reformulate liberalism in a way that muted the radical, progressivist, egalitarian, and utopian premises of the Progressive Era and to talk about ‘original sin’, the inherent irrationality of human nature, and the limitations of political solutions to intractable problems of the human condition’.Footnote 104 ‘Niebuhr's method’, Schlesinger remarked approvingly, ‘was to use “conservative” arguments to make a stronger case for “liberal” policies’.Footnote 105

Notwithstanding the conservative insights he drew on, Niebuhr explicitly rejected the notion that this process of conceptual innovation was distinctively ‘conservative’. There was, he argued, a basic error in ‘equating realism with conservatism’ and, as Daniel Rice points out, ‘Niebuhr's insistence on the distinction between “realism” and “conservatism”’ and ‘his deliberate choice of the term realist for himself’ reflected this conviction.Footnote 106 Moreover, since Niebuhr was convinced that there was ‘unfortunately, no social locus in America for a valid (that is, moderate, British) ‘conservative’ philosophy’, he saw ‘realistic liberalism’ as the only alternative to the extremes of left or right. Realism thus had considerable appeal within (and sometimes as part of) the ‘vital centre’ politics of the 1950s and early 1960s that, as James Nuechterlein put it, moved ‘from conservative assumptions to liberal conclusions’.Footnote 107

Another realist, John Herz, also worried about the rise of naïve power politics and cautioned that the ‘Adoption of this point of view would mean the ultimate ethical victory of the “Machiavellian”, power-political, fascist, and related values over those of liberalism, humanitarianism, pacifism.’Footnote 108 Seeking to rebut conservative charges that liberalism could not provide a cultural and ‘esthetic’ basis for a viable politics, he strove to formulate a robust ‘Realist Liberalism’ – a kind of ‘second liberalism’ capable of meeting challenges the radical Left and Right.Footnote 109

Morgenthau, in turn, took up the challenge in notably Arendtian tones. In a searching enquiry into the pitfalls and potential of American liberal democracy, he held that the philosophic foundations of the United States lay its constant commitment to change, an always-in-process goal of seeking ‘equality in freedom’. Like Niebuhr, he concluded that there was no social basis for an ‘authentic’ conservatism in America, echoing Louis Hartz's famous thesis that ‘the conservative view of politics endows the status quo with a special dignity and seeks to maintain and improve it. This conservatism has its natural political environment in Europe; it has no place in the American tradition of politics.’Footnote 110 Leaving aside the Confederacy ‘and other special interests, such as the concentrations of private power’, he continued, the great majority of Americans

have never known a status quo to which they could have been committed. For America has been committed to a purpose in the eyes of which each status quo has been but a stepping-stone to be left behind by another achievement. To ask America to defend a particular status quo, then, is tantamount to asking it to foreswear its purpose.Footnote 111

Meeting America's challenges required overcoming social, economic, racial, and political barriers to achieving the country's progressive purpose, not turning towards militant conservatism. Yet doing so required recognising the inadequacies and dangers of previous forms of liberal progressivism (including Wilsonian internationalism) and adopting the synthesis of ‘revolutionary liberalism’ and ‘conservative liberalism’ that represented the best of the American political tradition.Footnote 112

At the same time, realists and their liberal allies suggested that the radical Right's unwillingness to join this consensus was not just ideological – it was positively pathological. Adopting Hofstadter's influential treatment,Footnote 113 they argued that the radical Right was not really conservative at all. It was a ‘pseudo-conservative revolt’ reflecting the ‘status anxiety’Footnote 114 of its proponents – a product of maladjustment to liberal modernity, not a compelling critique of it. Schlesinger's verdict that Burnham's Containment or Liberation? revealed ‘the evolution, not of an intelligence, but of a neurosis’ captured the charge succinctly.Footnote 115

This kind of realism fits comfortably within the wider political and ideological context of the time. As Guilhot has perceptively noted, it represented an ‘unprecedented ideological hybrid for which we still lack a descriptive term’, but which exercised widespread appeal. Seizing the terrain of a kind of conservative liberalism, as well as a place within the ‘American tradition’, which, it argued, militant conservatism stood outside, realism became an ‘active ideological force’.Footnote 116 Manipulating the conceptual conventions and ideological alliances of the era, postwar realists sought to delineate the range of legitimate discourse. By casting the dominant debate as between itself and ‘utopian’ liberals, realism could make common cause with ‘realistic’ liberals such as Schlesinger (or ‘counter-Enlightenment’ liberals like Isaiah Berlin) on issues ranging from containment to McCarthyism, and occupy the ‘conservative’ position within a wider conceptual field that allowed a variety of forces within and around consensus liberalism to claim to recognise, address, and successfully engage the dilemmas of liberal modernity without having to grant entry to militant conservatism.

Conclusion: Legacies and limits

Perhaps the most powerful founding narrative in postwar international political theory is that it was born in a contest between realism and liberalism. As we have tried to show, this does scant justice to the actual history of international theory, or to the political issues at stake. Retrieving largely forgotten strands of radical conservative thought demonstrates that realism did not simply define itself against liberalism. It tried to construct a liberal-conservative position that, in addition to attacking a relatively thin liberal ‘idealism’, could deny the radical Right a place within the field's theoretical alternatives and, by extension, its discursive legitimacy. IR did not ignore radical or militant conservative views; the evolving historical narratives, and indeed the very conceptual structure, of the field excluded them.

As IR theory became increasingly formalised and professionalised during the 1950s and 1960s, the defining theoretical opposition between realism and liberalism solidified in its increasingly internal, professionalised conceptual discourse.Footnote 117 Even as ‘classical’ realism waned and consensus liberalism eroded, the grip of this divide on the theoretical and pedagogical imagination means that international political thought remains largely stuck within a constricted set of oppositions that fail to fully come to terms with either realism or conservatism – or the ways that contemporary radical conservatives are challenging liberalism today. At a time when the radical Right is making a comeback in global politics and a range of theoretical perspectives are seeking to come to terms with it,Footnote 118 the unrecognised legacy of the discipline's forgotten intellectual history represents a continuing obstacle. Understanding how this came to be the case is a first step towards overcoming it.

As we emphasised in the introduction, this marginalisation was not the product of realist theoretical manoeuvring alone. It reflected wider progressive political and ideological processes and developments across the social sciences. Likewise, to say that the radical Right was narrated out of the self-understanding of the discipline is not to say that those ideas and thinkers disappeared completely. Just outside of academic IR, in conservative philosophic discussions, political analyses, philanthropic networks and an expanding constellation of research, educational, and more corporate policy-advocacy institutions, militant conservatism continued to exercise significant influence.Footnote 119 A key possible avenue for future research in this respect would be to determine whether the declining influence of militant conservatism within academic IR provided an impetus for its thinkers to withdraw into those para-academic organisationsFootnote 120 and connect with those wider intellectual and political currents of the conservative movement that, for reasons beyond the scope of this article, had begun its long and increasingly successful rebellion against the ‘liberal consensus’ and through which, in recent years, they have again burst into prominence. If this is the case, one of the ironic and important consequences of the history of IR theory recounted here is that militant conservative ideas thrived by operating not in the academic field, but in the para-scholarly space just beyond the political world with networked connection to it. At a time when IR theory continues to ask questions about its ‘relevance’, the insights to be gained by putting a concern with the radical Right back at the centre of enquiry may be even more important than we have yet recognised.

Acknowledgements

For insightful comments on earlier drafts of this article, we would like to thank Rita Abrahamsen, John Mearsheimer, Robert Vitalis, and the three anonymous referees. We gratefully acknowledge support for this research from the Social Sciences Research Council of Canada grant 435-2017-1311. Jean-François would also like to thank the Velux Foundation and the Danish Institute for International Studies for support during the early stages of this project.