Introduction

One of the fundamental questions in International Relations (IR) is how can the world be changed into a better place. Yet, despite the normative aspirations to change dysfunctional, and often violent, practices, the IR discipline developed a widespread understanding that ‘the international’ was characterised by continuity and recurring patterns, and that the aspiration for making a better world, was an idealistic – even a utopian – project. The belief that change was unattainable became so ingrained in the discipline that when the Cold War ended, most had not even considered the possibility that such a change could take placeFootnote 1 and some even questioned its theoretical relevance.Footnote 2 Moreover, change was seen as one of those intellectual nettles that would be better left aloneFootnote 3 rather than as something that could be theorised, categorised, and conceptualised or indeed used prescriptively.Footnote 4 Therefore when constructivism entered the discipline proclaiming that ‘the world is of our making’Footnote 5 and that ‘anarchy is what states make of it’,Footnote 6 it not only opened up a completely new research agenda focused on change and agency, but it also returned the discipline to its original normative aspiration to be able to prescribe how to make change happen.

The new constructivist research agenda soon produced a voluminous literature enquiring into change. Emanuel Adler underlined the importance of change for constructivist research by suggesting that ‘if constructivism is about anything, it is about change’.Footnote 7 Change has been central to all constructivist theorising because of the fundamental premise that change is possible through the mutually constitutive relationship between structure and agency and the belief that the constancy of structure may be mitigated through agent practice, whilst agents’ identity and occasionally could be altered following structural change or through social processes of interaction.Footnote 8 Moreover with the constructivist insistence that structure is not just material but is ideas (nearly) all the way down,Footnote 9 relevant change was no longer just material structural change, but any kind of change that occurred when agents, through their performance altered the rules and norms that were constitutive of international interaction and in the process changed identities and hence interest.Footnote 10 The clear implication of constructivist theory was that if the world really is ‘what we make of it’, ‘we’, as individuals endowed with agency, can also ‘un-make’ recurrent dysfunctional practices. However, although there can be no doubt that constructivism has brought the discipline closer to understanding change, the promise of constructivist theory as an avenue for understanding change, and for prescribing how to achieve change, has arguably not been fully realised as constructivism seemed to develop a de facto focus on structure and stability rather than on agents and change.

The article starts from the constructivist premise that agent-led change is possible albeit difficult. I argue that the problem of change in constructivist theory is rooted in tensions and contradictions within and between constructivism’s own key assumptions, especially in the constructivist ontology of a social world consisting of structure and agency, in constructivism’s essentialist conception of identity, and in constructivism’s incomplete conceptualisation of change. Jeffrey Checkel has labelled the problem of change in constructivist theorising as ‘codetermination’,Footnote 11 in which key concepts are seen simultaneously as sources of stability and sources of change, yet without it being clear what motivates agents to switch from one to the other.Footnote 12 The puzzle is that constructivist research identified norms, rules, identity, and practice as both elements of stability and as essential for bringing about change, yet also linked assumed human desires for stability and predictability to the same concepts.Footnote 13 This article is essentially an attempt to resolve the problem of codetermination in constructivist theory with the ambition to be able to more fully understand why intended agent-led change often falters and how to better achieve the goal of making change happen. The logical solution to the codetermination problem might be to scale down the constructivist reliance on social psychology, which arguably has led to the (implicit) emphasis on continuity by focusing on the human need for cognitive stability and predictability. However, rather than taking flight from the reliance on social psychology as a way to understand human motivation, I prefer the approach championed by Ned Lebow who suggests that a more multidimensional and nuanced understanding of human motives to include appetite, spirit, and reason is the way forward.Footnote 14 I therefore remain committed to an explicitly psychological form of constructivismFootnote 15 centered on the self-constitution of agency through processes of identification and the suggestion that ontological security is a key concept for overcoming the ‘codetermination problem’.

The article proceeds in four main sections, starting out by locating ontological security as essential for the self-constitutive identification processes that are taking place at the agent level and as a decisive factor when agents decide to put their agency to use to undertake change-making action. I draw on the growing literature on ontological security to show that the search for ontological security is a primary motivational factor in all identification processes and a precondition for agents to use their agency strategically. In the second section I look more closely at the roots of the codetermination problem by focusing on constructivism’s conception of the social world, identity and change, drawing on authors such as Hidemi Suganami,Footnote 16 Charlotte Epstein,Footnote 17 and on the literature from Change ManagementFootnote 18 to offer alternative conceptualisations, which may help to alleviate the codetermination problem. In the third section the article moves inside the agent level to focus on agent-level identification processes and how the constitution of agency is an ongoing and always unfinished project arising from the ‘experience of being’, expressed through identity and narrative construction processes, and from the ‘experience of doing’ demonstrated through practice and actionFootnote 19 and with deep implications for the ongoing identity and narrative construction processes. Finally in the fourth section the article brings the strands together to present a constructivist framework for understanding agent-led change through ontological-security maximisation, suggesting that all agents engage in time consuming ontological security-seeking strategies, and that only when a sufficient level of ontological security has been achieved are agents able and/or willing to undertake the kind of action that might lead to change.

Ontological security

At its most basic level ontological security is ‘the security of the self’.Footnote 20 The concept was developed in the 1950s by psychiatrist R. D. Laing who described an ontologically secure person as ‘an individual that can be said to have a sense of his presence in the world as a real, alive, whole, and, in a temporal sense, a continuous person’.Footnote 21 Without ontological security there is a danger that the individual will be overwhelmed by anxieties that reach to the very roots of the individual’s coherent sense of ‘being in the world’.Footnote 22 Importantly the ontologically insecure individual will be ‘preoccupied with preserving rather than gratifying himself’Footnote 23 and so is unlikely to have a sense of agency or the inclination or ability to engage in social relationships or to undertake any form of action outside the narrow confines of simply preserving his or her own ‘being’. Moreover, from R. D. Laing’s description of ontologically insecure individuals, it is apparent that ontologically insecure individuals do not display the normal range of motives for action such as ‘spirit, appetite and reason’.Footnote 24 This is a point with hugely important implications for our understanding of why agents act the way they do. Yet, most IR theory either assume explicitly that agents act on the basis of reason and rationality or they assume, albeit implicitly, that agents are within a range of acceptable ontological security and hence have unimpeded agency and to be motivated in how they put their agency to use by one, or all, of the motives identified by Lebow.

Anthony Giddens introduced ontological security into social science in his structuration theory in the 1980s although the concept was not fully discovered by International Relations scholars until Brent Steele and Jennifer Mitzen (in separate articles) linked the concept to state identity and the security dilemma. Brent SteeleFootnote 25 suggested that the ontological security of states had been an overlooked form of security and that states wanted to maintain a consistent Self, which however could be undermined by state actions following a critical event, if the actions undertaken contradicted the values and norms on which the state’s identity was based. Importantly Steele suggested that actions that are not in accordance with the values and principles of the state would result in shame, which could lead to revisions of the state’s identity. In this sense Steele showed the need for coherence between identity, narrative and the actions undertaken by states as well as the importance of critical events for dislodging ontological security. Mitzen showed that ontological security is not necessarily related to action that is conventionally seen as ‘good’ such as peaceful relations. In fact states may prefer to continue to engage in what would logically appear to be dysfunctional conflictual practices, because doing so reinforces ‘the Self’ and because routinised practices have an intrinsic value by providing a stable cognitive environment.Footnote 26

Since the introduction of ontological security into International Relations, the relevance of the concept for the study of IR has been emphasised in a growing literature. In a general sense, ontological security can be said to be present when an agent has a stable view of ‘self’ with a sense of order and continuity in regard to the future, relationships, and experiences. Ontologically secure individuals are better able to realise their own agency because an ontologically secure individual is said to have a protective cocoon and a sense of ‘unreality’ to the many dangers that could threaten bodily or psychological integrity, which, if fully realised, would lead to paralysis in action as the individual would be overwhelmed by the many risks associated with living.Footnote 27 To be ontologically secure is to possess ‘answers’ to fundamental and existential questions and to have ‘basic trust’ which can limit anxiety to a manageable level.Footnote 28 Anxiety-management is important because anxiety is likely to paralyse agents, whereas fear is an altogether different kind of emotion arising from a specific threat, which may push agents to take action they would not otherwise have considered.Footnote 29 This is why Change Management often talks about creating ‘a burning platform’ because the fear that would arise from being on a ‘burning platform’ is likely to motivate individuals to undertake extraordinary action whereas anxiety will produce an urge to reinforce the agent’s cognitive stability and confidence in the continuation of the known ‘life world’.Footnote 30 In order to limit anxiety to acceptable levels,Footnote 31 individuals undertake routinisation of everyday practices, which not only reinforce the individual’s sense of beingFootnote 32 but which also provides coping mechanisms that regularise social life and provide confidence that the cognitive world will be reproduced. Routinised practices reinforce ontological security (at least until they for a variety of reasons may become dysfunctional) as they contribute to a stable cognitive environment. Yet, life also necessitates undertaking non-routine action and the ability to make, and cope with inevitable change.Footnote 33 An obsessive reliance on routines is a sign of a ‘neurotic compulsion’,Footnote 34 which is evidence of a lack of ontological security.Footnote 35

Giddens explains that identity is found in the capacity to keep a ‘strong narrative’ going,Footnote 36 which must incorporate a story about the self (who am I and what do I want) and past experience (what have I done and why). It is clear that individuals care deeply about their own actions and that they are likely to experience either shame or pride when judging the success or failure of past actions with clear consequences for their self-esteem and their ability to maintain a ‘strong narrative’.Footnote 37 Therefore, although routinisation of practice and a stable identity may be preferred by agents, action that changes established routines is sometimes a necessary undertaking, especially in response to disruptive events or unintended consequences.Footnote 38 Moreover, as underlined by Mitzen, it is ‘a crucial requirement of individual self-understanding that actions can sustain it over time’,Footnote 39 as the consequences of action will influence ongoing identification processes by reproducing, contradicting or changing self-identifications.Footnote 40 This point is also underlined by Charles Taylor who asserts that human agency is constituted by strongly evaluative self-interpretations of past actions, which are partly constitutive of our experience.Footnote 41

Since the introduction of ontological security to International Relations theory, a significant literature has emerged. In Critical Security Studies, the link between ontological security and physical security has been investigated to understand how securitised issues can be brought back to the realm of normal politicsFootnote 42 – or how to ‘un-make’ dysfunctional practices – by differentiating between ‘security as being’ and ‘security as survival’. The interesting finding is that desecuritisation need not take place through a social relationship with an ‘Other’, but can also be achieved through self-constitutive identification processes.Footnote 43 The concept has been increasingly used by a new generation of constructivist scholars who see ontological security as a means of highlighting the analytical separation between ‘self’ and ‘identity’ and how the nature of ‘self-identity’ is a ‘reflexive project’ that must be constantly ‘worked at, and striven for, across many different social and institutional contexts’.Footnote 44 In this understanding, emphasis is not on the stability of identities, but rather on how reflexivity towards identity within a constantly changing world requires continuous processes of identification and narrating the influence of ‘dislocatory events’ that often compel agents to undertake action or to change their practice and to reflect on how events and action impact established identification and narrative processes.Footnote 45 From this perspective, ontological security is not only of importance in those cases where it is lacking, but is important more generally for understanding identification processes as part of a reflexive project of continuously seeking to maintain a sense of ‘self’ through ‘being’ and ‘doing’ in a constantly changing environment.Footnote 46

Ontological security has also been utilised in the constructivist literature on the importance of biographical narratives and memory. For example, Maria Mälksoo has demonstrated that in a changing environment, memory becomes especially important as a temporal orientation device that constitutes the central core of a biographical narrative.Footnote 47 In this connection what is important is not so much what happened, but rather what was remembered – especially what was incorporated into the biographical narrative. This is an issue of importance both to ontologically secure and insecure individuals/entities, because as shown by Stuart Croft, although the ontologically secure individual does not worry about the deeper meaning of life and although social interactions are largely unproblematic and based on inter-subjective understandings that define the boundaries of the normal, there is always a fragility and precariousness to ontological security,Footnote 48 which means that even ontologically secure individuals need to continuously maintain their narratives and situational accounts of who they are and why they behave as they do.Footnote 49

The fragility and precariousness of ontological security is also underlined by Felix Berendskoetter, who suggests that identity is constituted through experience and knowledge structures, which are constantly developing and which suggest that neither the ‘self’ nor ‘the world’ are ever solidified but are constantly evolving.Footnote 50 Both need constant regrounding and adjustment in response to events and past actions and future visions. Drawing on Martin Heidegger’s ontology of ‘being-in-the-world’ (which Laing also used), Berendskoetter outlines how an entity (individual or state) is constituted through a narrative designating an experienced space, which seeks to give meaning to the past, as well as an envisioned space, which seeks to give meaning to the future.Footnote 51 Significant experiences – both good ones and bad ones – are likely to leave an imprint on the biographical narrative, which on each occasion is likely to require a reconfiguration of the narrative and the related identification processes.Footnote 52 Therefore, rather than just focusing on how identity is constituted in relations with others, the possibility of self-constitutive processes based on reflexivity of past experience and evolving knowledge structures emerges. As a result, being ontologically secure does not mean having a stable identity, but rather that the ‘self’ is constantly reconstituted and regrounded on the basis of changing knowledge structures that are captured in narratives and incorporated into identification processes. As such, ontological security is always a fragile and contingent condition that is constantly in danger of being destabilised by ‘dislocatory events’ or of being undermined by behaviour that is evaluated negatively by the external environment or by the individual/entity.

Although ontological security as a concept initially was developed for understanding how individuals with severe psychological issues might experience their own existence and the limitations a lack of ontological security would place on their ability to function in the wider society, the concept holds considerable potential for understanding how agents are able to utilise their agency, and perhaps more importantly, how a lack of ontological security might severely limit the ability of agents to fully exercise their agency in a strategic way. In the following, I draw on the literature on ontological security outlined here, to in the first instance return to the problem of codetermination in constructivist theory and then to outline a constructivist framework in which the continuous ‘regrounding’ of ontological security appears to be central for understanding how (and when) agents are able to utilise their agency strategically to bring about change.

Revisiting the social world, change, and identity

The problem of codetermination arises from the simultaneous belief that on the one hand, change is possible through agent practice and changing ideational structures (such as norms), and on the other hand, that the very same practices and norms have structural characteristics through their resilienceFootnote 53 derived from agents being hardwired to prefer the stability and cognitive consistency they provide.Footnote 54 This raises the question of how the impetus for change arises in the first place. In other words, if agents reproduce their own structural constraints though the very same quotidian practices and norms that are assumed to bring about changeFootnote 55 and they instinctively prefer stability to change, how does change ever take place? To move towards an answer to this question it is necessary to revisit constructivism’s foundational assumption about the social world as a duality of structure and agency, which leads to a problematisation of constructivism’s understanding of external and internal sources of change.

The ontology of the social world

The constructivist conceptualisation of the social world as consisting only of structure and agency, is a problem for understanding change because the possibility of change is restricted to structures changing through agent practice or agent’s practice changing through structural shifts. I am persuaded by Hidemi Suganami that the constructivist reliance on the structure-agency dichotomy represents an incomplete understanding of the social world and that a more all-encompassing understanding of the social world is one that focuses on a trinity comprising of those elements of life that can be changed, those that can’t, and those that just happen by chance. Therefore rather than seeing the social world as consisting of just structure and agency, I follow Suganami (and strangely Singer) in understanding the social world as consisting of elements that can be described as ‘voluntaristic, deterministic and stochastic’.Footnote 56 Suganami’s notion of the social world problematises the constructivist foundational assumption that structure and agency are mutually constituted,Footnote 57 because it suggests that the mutual constitutiveness between agency and structure is only part of a wider process that also includes important self-constitutive processes located inside the agent level, which are additionally, as suggested by constructivism, influenced by structural (deterministic) factors but which are also influenced by other random (stochastic) factors that like the deterministic factors are located outside the agent level. By including other external (to the agent) factors than just structure, the well recognised influence from the occurrence of events, from social processes with other agents and from unintended consequences from agents’ own actions move into theoretical view as additional external sources of change. Moreover by opening up the agent level and looking inside the agent level, the reflexive (voluntaristic) agent based identification processes that are recognised in the literature on ontological security also move into theoretical view thereby providing a theoretical space for processes that were invisible (or bracketed) in early constructivist theory.

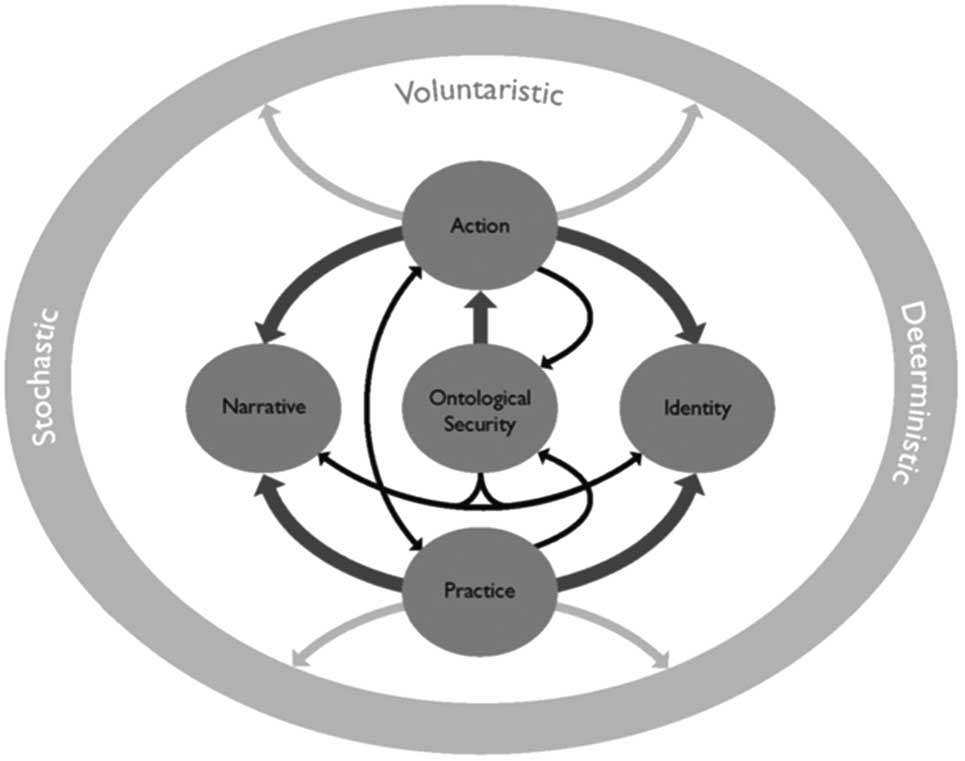

With Suganami’s conception of the social world, it follows that agents are not social and cultural ‘dupes’ blindly reacting to structural change or unthinkingly producing significant change through endless minor modifications of their practice (although both of these also happen) but that agents (human beings) act with purpose and intention – sometimes to bring about change – but always to seek to maintain or establish their ontological security. In this article, I assume that agency is constituted through relational processes with externalities (structures, events, and social relationships with other agents) and through internal sources of change found in the agent’s self-constitutive identification processes, which involve significantly more self-reflection and self-constitution than is implied in most constructivism. This assumption is expressed later in the article in Figure Three in the shaded ring, which represents external sources of change conceptualised as deterministic and stochastic sources of change which are placed around the voluntaristic processes, which represent internal sources of change originating inside the agent level.

Conceptualising change and its external sources

I have already alluded to the constructivist focus on change and the belief that dysfunctional practices can be ‘un-made’ through changes in agents’ identity and/or in the ideational milieu such as in commonly held norms and values,Footnote 58 constitutive rules,Footnote 59 or in social deeds/rules.Footnote 60 The sources of such change is often assumed to be a ‘critical juncture’, which will have revealed a disconnect between the ideational structure and agents’ experience of who they are and what they do, where it is widely agreed that agents will suffer from severe cognitive dissonance, making them highly motivated to accepting transformative change for example by searching for a new norm set with a new identity and new associated practices and appropriate action.Footnote 61 However, the centrality of the ‘critical juncture’ in constructivist thinking about change is curious, because in a social world conceived as a duality of structure and agency it is unclear who – or what – produces the critical juncture.Footnote 62

The other widely cited source of change in constructivist theorising is change as the result of processes of socialisation in which one set of agents (or a social group) seeks to induce identity or norm change in another group of agents. There is an extensive constructivist literature on socialisation in which it is argued that in times of cognitive dissonance, agents will be particularly open to influence from other agents through various forms of social interaction such as argument and persuasion,Footnote 63 socialisation,Footnote 64 or simply by mimicking other agents.Footnote 65 The focus here is on how norms or other non-material forms of structure might be changed, which in turn might change identity and interests. Yet as pointed out by Felix Berenskoetter,Footnote 66 few early constructivists have offered substantial insights into identity and how it is formed, let alone how it informs action. Indeed Alexander WendtFootnote 67 stated explicitly that his version of constructivism was not concerned with the formation of identity. In this sense therefore the emphasis on socialisation as a means to change norms and identity is also curious because not only are they processes of socialisation, processes that take place in an agent-agent constitutive relationship rather than in a mutually constitutive relationship between structure and agency, but it is also unclear where in a social world conceived as a duality of structure and agency the motivations for some agents to seek to socialise other agents come from.Footnote 68 The main sources of change in constructivist theory – critical junctures and relational social processes such as socialisation – leave constructivism with a problem of accounting for emergent factors originating neither at the structural level nor at the agent level. Moreover, despite constructivism’s rhetorical embrace of change, surprisingly little work has been undertaken on conceptualising change and for understanding the many forms different forms change can take. Therefore in order to bring more depth and nuance to our thinking about change, it is instructive to look to the literature on Change Management.

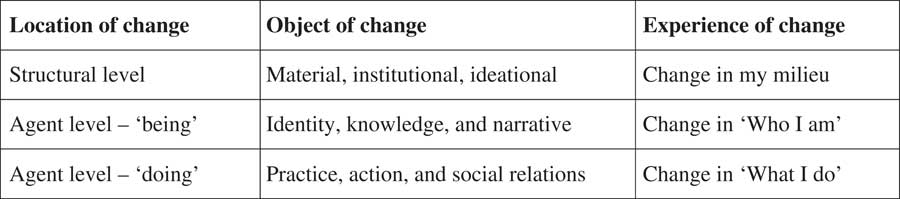

With inspiration from Change Management theory, I use a two-pronged approach to inquire into the ‘form of change’ in terms of location, object and experience, and by distinguishing between different ‘processes of change’ in terms of them being planned, emergent, evolutionary, or revolutionary.Footnote 69 I identify three different ‘forms of change’: one located at the structural level characterised by change in material, institutional, and ideational elements;Footnote 70 as well as two agent-level forms of change – one in the experience of ‘being’ observable in agents’ identity, knowledge, and narrative and the other in agents’ experience of ‘doing’ demonstrated in their performance through practice, action, and social relations. Constructivism has over the years been engaged with all three processes of change, but their difference has not been explicitly noted. These different forms of change are experienced as changes either in the material, ideational, or discursive milieu of the agent or as change in ‘Who I am’ and in ‘What I do’. The different forms of change are summarised above (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Forms of change.

Apart from different forms of change, change also takes place through different processes. Generally speaking, IR has operated with assumptions about the process of change being either intentional and progressive towards a particular vision or as being characterised by agents’ habitual practice occasionally interrupted by crises.Footnote 71 Curiously, the importance of events has been on the one hand clearly visible through the emphasis on ‘critical junctures’ – or perhaps better termed ‘dislocatory events’ and on the other hand as almost absent from theoretical discussions because ‘event-driven’ change has been dismissed as ‘reactive’ as opposed to the more desirable ‘strategic’ change. However, given Harold MacMillan’s memorable answer when asked what was most likely to throw a government off course: ‘events my dear boy – events’,Footnote 72 the failure to theoretically account for the occurrence of events seems a major deficiency in constructivist theorising on change. It seems clear therefore that a first step towards a more complete understanding of processes of change is to be aware of the different change processes ‘out there’ and to theoretically open up for the possibility of accounting for events. Again it is instructive to look to Change Management where the necessity of theoretically accounting for ‘events’ has long been recognised.Footnote 73

On the one hand, change can be said to be continuous and ever present as agents and structures alike are always in a process of becoming.Footnote 74 In this understanding, change is a temporal entity inextricably tied to an imagined future of the self and a narrative about the journey towards the imagined endpoint of the process of becoming. This is the view of change that has been most prominent in constructivist theorising in IR. But change can also be characterised by episodes marked by events or by actions undertaken by the agents that may have unintended consequences and which may at any time alter the direction and speed of the process of becoming.Footnote 75 These processes can be conceptualised as either planned or emergent,Footnote 76 where ‘emergent change’ is random and takes place when new patterns of performance emerge in the absence of explicit a priori intentions.Footnote 77 In this conception change can be either evolutionary or revolutionary,Footnote 78 depending on whether the ‘episode’ is a critical (or dislocatory) event, leading to transformation of the existing milieu, or if the ‘episode’ is simply a minor event requiring adjusted performance within the existing structural environment. With the insights from Change Management, processes of change can be described as emergent, planned, evolutionary, and revolutionary as outlined in the matrix above (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Ideal-type change processes.

The four possible change processes outlined in Figure 2 are of course ideal-types that are unlikely to be found in their pure form in actual change processes and clearly the three forms of change (see Figure 1) cannot easily be separated as I have done. In ‘real life’ the three forms of change are likely to be highly interconnected and mutually constitutive, where the different forms of change will continuously impact upon the agents’ ‘experience of being’ and ‘experience of doing’, which will result in continuous processes of identity and narrative constructions and in adjustments to changes in the shared knowledge, all of which is contingent on (rare) changes at the structural level (deterministic factors) as well as the (more frequent) occurrence of events (stochastic factors). In ‘real life’ agents are faced with the challenge of having to navigate strategically in an emergent environment characterised by the continuous occurrence of events, unintended consequences of past action, and the occasional crisis. The theoretical (and indeed practical) challenge therefore is to understand change as varied in both form and process and as something that places high demands on agents’ ability to reflect on their actions and use their agency strategically to bring about the desired change – preferably without detrimental consequences for agents’ self-esteem and standing. In practice, this probably means that to make change happen, agents will be engaged in a continuous struggle to manage emergent change, unintended consequences and to occasionally be disrupted by crises that require the undertaking of transformational change – all of which will require regrounding of the agents’ ontological security. To understand these processes, it is necessary to move to the second consequence of the Suganami-inspired social ontology, which is to look for the sources of change located inside the agent level.

Identity and internal sources of change

Constructivists believe that change can be achieved through identity change because identity is linked to interests, which will influence behaviour. However, constructivists (at least conventional ones) also adhere to an essentialist view of identity, which logically means that identities are preconstituted and fixed. Moreover by focusing on change as something that (almost) inevitably follows crisis and by emphasising norms as something that comes part and parcel with a socio-culturally determined identity and appropriate behaviour located in different pre-existing social groups, constructivists shied away from engaging in a deeper understanding of the reflexivity preceding norm and identity change and from understanding what other factors than cognitive dissonance might motivate agents to undertake changes in their identity and in their behaviour. This focus was perhaps understandable within the context of the early constructivist attempt to counter neorealism, but as suggested by Charlotte Epstein, it brought constructivism on a path that assumed the self to be fully formed prior to engagement with structure.Footnote 79 Constructivism effectively sought reconciliation between a structural, systemic focus that required positing given units and appraising them from the outside, while emphasising effects that called into question the assumed given-ness and which required opening up the units.Footnote 80 As we saw above in the section on ontological security, this issue has been taken up by a new generation of constructivists who ask how identities are constituted and what motivates actors to realise the possibilities of ‘being’ and ‘doing’Footnote 81 and more generally to appreciate the multifaceted nature of human agency and the ways in which agents make up their minds about how to put their agency to use.Footnote 82

One of the first approaches to try to understand the connection between identity, norms, and behaviour was to use social identity theory (SIT) for answering why agents associate themselves with certain identities and take on certain norm sets with specific behavioural expectations. Drawing on the literature from social psychology such as Henri TajfelFootnote 83 and John Turner,Footnote 84 constructivists argued that agents strive to maximise their self-esteemFootnote 85 by gaining membership of highly ranked social groups. It was argued that membership of a social group would require agents to take on the identity of the social group and to behave in accordance with the group’s socially sanctioned norms. Agents would be willing to do so because belonging to a highly ranked social group would afford the individual esteemFootnote 86 and standing.Footnote 87 Moreover, from narrative theoryFootnote 88 constructivists could point to how the identity of the individual and the social group continuously would be presented through ongoing narrative constructions, which would at all times seek to ensure positive emplotment and sense-making of the past by incorporating continuously occurring events into a narrative providing biographical continuity and supporting the identity of the social group.Footnote 89 The relationship between identity and narrative is widely acknowledged but has been specifically linked by Felix CiutâFootnote 90 through what he calls the ‘narrative shuttle’. Ciutâ sees the narrative shuttle as an ongoing process in which narratives and identities are continuously reinterpreted and realigned against each other in a process of ‘shuttling’ back and forth between ongoing narrative and identity construction processes, producing a continuous (re)constitution of narratives and identities and incorporating the occurrence of events and evaluation of performance.

Despite the contributions from social identity theory and narrative theory, the implicit assumption about the essentialist self was not fully overcome because it simply moved the question from one assumed given identity to a choice between several available, but fully formed, identities. Moreover, the constructivist foundational idea of a dialectic between structure and agency has meant that constructivism has struggled to demonstrate how agency is constituted and why, once constituted, agents might sometimes use their agency to bring about change. The turn to practice within constructivist theory has moved constructivist research some way towards addressing this issue by recognising practice as not just a mechanical form of routinised performance but also as constitutive of agency. In this view practice is not just a means for gradually changing structure as advocated in early constructivism but is actually constitutive of the agency that can undertake change.Footnote 91 As Janice Bially-Mattern notes, practice is about ‘how humans do their very being in the world’Footnote 92 and how they organise human life, establish social order, and transform the social orders they create. The ‘practice turn’ is an important point in the continuous development of constructivism towards overcoming some of the problems associated with ‘codetermination’ because it challenges some of the assumptions about change made during the initial stages of constructivist thinking and it avoids many of the traditional dichotomies between stability and change, agency and structure, as well as between ideas and matter.Footnote 93 Even so practice theory does not fully account for the motivational issue of why agents sometimes make the strategic choice of seeking change by altering the established practices that they are said to value.

I agree with Epstein, Mitzen,Footnote 94 SteeleFootnote 95 , Browning and Joeniemmi,Footnote 96 and others in the view that identity cannot be assumed to be preconstituted, but that it is continuously constituted in processes of ‘identification’Footnote 97 in complex and interlinked processes of agents’ identity and narrative constructions and their performance through practice and action. The assumption of a mutually constitutive relationship between structure and agency severely limits the theoretical scope for accounting for self-constitutive processes at the agent level, and for other external stimuli than structural factors, and it therefore requires opening up the agent level for further scrutiny. However, even with opening up the agent level to look at the self-constitutive identification processes taking place there, the assumption that agents prefer stability, leaves little room for self-constituted identity change. This is where the emerging literature on ontological security can offer insights into the micro-foundations of agents’ behaviour and identity changesFootnote 98 because the literature on ontological security suggests that people are much more reflexive about themselves and their actions than is usually acknowledged by constructivist theory.

The framework developed in this article, rests to a large degree on the insights from social psychology and from the IR literature on ontological security.

Inside the agent-level: Ontological security as motivation for utilising agency

If the question is how and when agents make decisions to undertake action that can lead to change at any one of the three ‘locations’ identified in Figure 2, given that two out three forms of change are located at the agent level, our focus has to be on the agent itself, how agency is constituted and the conditions necessary for agents to use their agency purposefully. I start from the rather simple premise that agency entails ‘being’ and ‘doing’ implying a ‘self’ defined by an identity, articulated through a narrative and performed through practice and action, which is continuously regrounded as a reflexive project’ that must be constantly worked at.Footnote 99

The literature on ontological security suggests that ontologically secure individuals are individuals who, although they may prefer a stable cognitive environment, have the ability to undertake change-making action when needed and who can cope with the change it induces and who are able to continuously incorporate change into their narrative and identity constructions. Moreover, based on the literature from social psychologyFootnote 100 it seems reasonable to assume that all individuals develop a framework for maximising their ontological security through their ‘being’ in terms of identity and narrative and their ‘doing’ in terms of practice and action. Ontological security can therefore be assumed to significantly influence the ability (or willingness) of agents to exercise their agency by undertaking the kind of action that might lead to change. Moreover, from the literature on ontological security it seems that the maximisation of ontological security can be seen as an important motivational factor in the self-constitutive processes taking place inside the agent level. From that I make the perhaps controversial move to regard ontological security maximisation as functionally equivalent to rationalist theories’ agent assumption of utility maximisation and I build on social identity theory’s agent-level assumption of self-esteem maximisation.Footnote 101

By adopting Suganami’s understanding of the social world and by understanding agency as constituted inside the agent level through ‘being’ and ‘doing’, it is possible to connect the different forms and processes of change into one overall framework in which identity, narrative, practice, and action are all connected through the basic need for human beings to at all times maintain a sufficient level of ontological security. The agent-level identification processes and their connection to ontological security and the influence of stochastic and deterministic factors are illustrated graphically in Figure 3, in which the four ‘bubbles’ illustrate the ‘experience of being’ in the identity and narrative construction processes as well as the ‘experience of doing’ through the performance of practice and action. The identification processes have been placed inside the shaded ring, with the ring representing the many stochastic and deterministic factors, which continuously will exert influence on agents and their identification processes. The bracketing of the stochastic and deterministic factors should not be read as a downgrading of their importance, but is simply an acknowledgement of the great variety of stochastic and deterministic factors that are constantly bombarding agents and providing new input to the self-constitutive voluntaristic processes continuously taking place inside the shaded area. The many possibilities for stochastic and deterministic influences include (but is not limited to) critical junctures through gradual and sudden structural change, the constant occurrence of events – dislocatory ones as well as minor ones, intended and unintended consequences arising from agent’s own actions as well as stimulus from social relations with other agents through, for example, socialisation, persuasion, or through learning from the behaviour of others as well as material change in for example infrastructure or the natural environment.

Figure 3 Voluntaristic identification processes inside the agent-level.

Change-making action will necessarily undermine cognitive stability by undoing the very practices that ensure cognitive stability, and it will require adjustments in agents’ identity and narratives. Logically therefore, change is always difficult to achieve because the agent action that is supposed to bring about change is difficult to sustain, as the inevitable disturbances in agents’ cognitive stability as well as changes in identity and narratives might lead to anxiety and hence a reduction in ontological security, which might result in paralysis rather than the ability to undertake action. This link may indeed explain the poor success rate observed in the field of Change Management in most change initiatives.Footnote 102

Although change-making action necessarily will undermine the aspect of ontological security that is associated with cognitive consistency, because individuals reflect and care deeply about their performance, action that is perceived to be successful can offer the prospect of strengthening ontological security by providing the individual with a sense of pride and a positive impact on self-esteem (or if action is perceived as unsuccessful) it can undermine ontological security. This is a crucial point because the connection between ontological security and action (represented in Figure 3 by the arrow from ontological security to action) is only likely to be active when the level of ontological security is sufficient enough to afford agents the emotional capacity to undertake non-routine action. Moreover, whether such action will be a one-off or whether it can be sustained over time depends on the perceived success of the action, as unsuccessful action will result in negative adjustments in identity and narrative constructions and in more time consuming processes of shuttling back and forth on the narrative-identity shuttle until ontological security can be re-established. This stands in contrast to situations where the action is deemed successful. In such a situation agents are likely to feel confident and enthusiastic about undertaking further change-making action and thereby open up for the (rare) possibility of a sustainable change process.

Ontological security maximising strategies

Given the vexatious nature of social reality especially caused by the continuous influence from stochastic and deterministic factors and the necessity of agents continually having to readjust their identity, narrative, and practice in response to stochastic and deterministic influences, ontological security is a fragile and transient condition that must be endlessly reconstituted and reasserted.Footnote 103 In doing so, agents are constantly engaged in costly (in terms of attention) and time-consuming processes of seeking to maximise their ontological security.Footnote 104 I identify two strategies for maximising ontological security; a ‘strategy of being’ focused on the nexus between narrative and identity constructions and aiming to secure a stable and esteem-enhancing identity and biographical continuity through the construction of a ‘strong narrative’; and a ‘strategy of doing’ focused on the seemingly paradoxical relationship between practice and action to, on the one hand, uphold a stable cognitive environment through routinised practice whilst at the same time being able to undertake change-producing action in reaction to stochastic and deterministic factors that can also contribute to maintaining a sense of individual integrity and pride. The two strategies are inter-linked and mutually constitutive and cannot be understood in isolation from each other – or in isolation from the constant influence of deterministic and stochastic factors.

In the ‘strategy of being’, I build on Ciutâ’s narrative shuttle by arguing that agents are primarily engaging in the ‘narrative shuttle’ with the aim of achieving coherence between narrative and identity at the highest level possible in terms of a positive and status giving identity, which can enhance self-esteem and which is supported by a convincing and positive narrative that can incorporate all voluntaristic, stochastic, and deterministic influences and provide biographical continuity. The point where this aim is achieved is where the agent has ‘ontological security’, which in Figure 3 is the point graphically expressed by the ‘upward’ move from the ‘smiley’ line into the ‘ontological security bubble’. The aim of the ontological security seeking strategy of being is to reach and maintain this point in the process.

At a first glance the establishment of a stable, esteem-enhancing identity supported by a ‘strong narrative’ seems to be a relatively easy undertaking as there often is considerable scope for ‘selectivity’ and ‘creativity’ in narrative constructions and in possible identity constructions. SIT has been used extensively in constructivist theorising to show how identities are constituted through membership of a social group, which is of paramount importance for simultaneously providing individuals with their identity and self-esteem.Footnote 105 According to SIT, individuals will attach value to any social group they are member of – no matter the actual qualities of the social group.Footnote 106 In this view even individuals who may be unable to gain access to a highly ranked social group are able to seek affirmation of their self-identity by drawing closer to alternative groups (such as gangs) or to a more open collective group (such as a religious group) and in doing so may reduce their insecurity and anxiety by providing core ‘identity signifiers’ such as religion or nationalism.Footnote 107 Therefore if, as outlined in the previous section, ontologically secure individuals are individuals who are able to sustain an esteem-enhancing identity supported and reinforced by a ‘strong narrative’, ontological security should be in reach of most no matter their actual position in society.Footnote 108 Following this logic, strategies for maximising ontological security through the narrative-identity nexus, span from attempting to join highly ranked social groups (available only to the lucky few) to joining more open groups that provide identity signifiers albeit at a much lower level, but that can enable the formulation of a narrative that emphasises alternative ways of achieving pride, honour, and self-esteem. However, as shown in Figure 3, the narrative shuttle is not a self-contained process, and even though the ‘strategy of being’ primarily takes place on the identity-narrative shuttle, narrative and identity constructions are also influenced by deterministic and stochastic factors and by the two other agent-level voluntaristic elements of the model – practice and action. As was pointed out by Stuart Croft,Footnote 109 the precariousness of ontological security is therefore always a factor in the calculations of agents.

Apart from engaging in ontological security maximisation through a ‘strategy of being’, individuals will also seek to maximise their ontological security through a ‘strategy of doing’. Maximising ontological security through the strategy of doing will however depend on whether the practice and action undertaken reinforce the identification processes to produce self-esteem and biographical continuity and hence to reach the point in Figure 3 of the ‘upward’ move from the ‘smiley’ line into the ‘ontological security bubble’. This corresponds with one of the major claims of practice theory – that practice has been an important, but largely overlooked, influence on both narrative and identity as both are constituted and reified through social practice.Footnote 110 Moreover, as noted by Giddens, individuals are not ambivalent about the nature of their actions, but care deeply about the success or failure of their actions with significant repercussions on their self-evaluations.Footnote 111 These claims and their connection to the ‘strategies of doing’ are important because input into the narrative-identity nexus from the ‘action’ and ‘practice’ elements in Figure 3 will prompt changes in identity and/or narrative, giving rise to further rounds of shuttling back and forth on the ‘narrative shuttle’ before the ‘upward’ move to ontological security is possible. In practical terms this means that the maintenance of ontological security over time is likely to be demanding and to involve costly and time-consuming processes that can appear to be ‘navel contemplating’ whilst agents ‘self-analyse’ and seek to formulate the necessary strong narrative. However, although practice and action are both intricately tied up with ontological security – this is so in different ways, which is why I, in contrast to most constructivist and practice theory, distinguish between the two.

Routine practices are likely to always have a mildly reinforcing effect on the narrative and identity construction processes and hence on ontological security by providing a stable, and largely taken-for-granted cognitive environment. Ontological security seeking will therefore involve routinisation of practices as far as possible. But whereas routinised practices are likely to reinforce the important sense of order, stability, and basic trust that is necessary for ontological security, it is unlikely to provide agents with any sense of pride or enhanced self-esteem, and practice certainly does not lead to change and may eventually be perceived as dysfunctional if practices are not adjusted in reaction to stochastic and deterministic factors. Moreover if change in practice result in even a temporary ‘disconnect’ between practice and the existing narrative-identity nexus, this is likely to give rise to an identity crisis and/or a crisis narrative.Footnote 112 Once such a ‘disconnect’ between practice and the narrative-identity nexus is realised, it is likely to have detrimental effects on ontological security and to lead to a new time-consuming process of shuttling back and forth on the narrative shuttle to re-establish ontological security. Whilst agents are busy shuttling back and forth on the narrative shuttle, they are less likely to have the inclination to take on new action – even when change is clearly needed.

Although all four elements of the model – an esteem-enhancing identity supported by a ‘strong’ narrative and reinforced through practice and action – are necessary for the maintenance (and re-establishment) of ontological security, the action element may only be actuated occasionally, as agents prefer the status quo sustained through practice to the change that could be attained through action. Moreover, paradoxically even successful action will (at least initially) undermine ontological security because it will necessarily change the very practices that provide cognitive stability. Added to this is that there is always a risk that action may be unsuccessful, which could lead to negative emotions such as shame and frustration and hence that it undermines ontological security rather than reinforce it. Moreover, if a change process is to be sustainable, the action undertaken must be perceived by the agents themselves as successful – meaning that the changed practices and resulting cognitive disturbance can be evaluated positively – which, given the paradox that agents prefer stability yet need self-esteem – is difficult to achieve.

If agents evaluate their action positively and are able to cope with the ensuring cognitive inconsistency, a dynamic and expanding change process might be initiated.Footnote 113 Such action is ‘reinforcing action’ providing agents with positive emotions such as pride, enthusiasm and confidence, which is likely to produce a ‘can do’ attitude and willingness to initiate further action. However, action that is deemed unsuccessful and which fails to positively contribute to the ongoing narrative and identity constructions and which is evaluated negatively by agents, is ‘undermining action’ that may produce negative emotions such as shame, frustration, and uncertainty. Unsuccessful action will usually be terminated causing the change process to fizzle out, but in those cases where termination is not possible (for example a military intervention or a contractual relationship), a negative and undermining dynamic may be the result with severely detrimental consequences for ontological security. This is a risk that one must assume will always be part of agents’ calculations of whether or not to undertake change-making action.

Given that undermining action can have severely detrimental effects on ontological security, it seems reasonable to assume that agents will be reluctant to undertake change-making action unless they are fairly certain of the action being rated as successful. The crucial question for agents seeking ontological security is therefore whether action is likely to be reinforcing or undermining. In day-to-day life, agents seeking ontological security will pursue the relatively safe option of simply engaging in practice that is in line with the agents’ narrative and identity and which will furnish them with cognitive stability. Because such practice is habitual, it is unlikely to prompt agents to question the existing narrative-identity nexus, but nor is it likely to provide them with any sense of pride or enthusiasm. The problem is that all negative influences from within the voluntaristic processes such as dysfunctional practices or undermining action and from external stochastic and deterministic factors are likely to block for the undertaking of new action. Moreover the number of stochastic factors, which might not be successfully incorporated into the ongoing narrative and identity constructions are so plentiful that they are probably the norm rather than the exception.

The intricate relationship between identity, narrative, action, and practice and the clear relationship between the two ontological security seeking strategies may well explain why change – especially sustainable change – seems so difficult to achieve. In the model illustrated in Figure 3, a positive and dynamic process of change is only likely when sustained reinforcing action is taking place (illustrated with the thick arrow from the ‘ontological security bubble’ to the ‘action bubble’), and when both ontological security seeking strategies are successfully invoked, and only for as long as action remains reinforcing. In the absence of ontological security, agents have only limited surplus or inclination to undertake new action, but will concentrate on routinised practices, as they may contribute to an acceptable level of ontological security, but are unlikely to motivate action beyond maintaining the status quo. Given the infinite number of possible external influences to interrupt the search for ontological security, coupled with the certainty that changes in practice will lead to cognitive dissonance and the significant risk that agents’ own action may not be successful or may have negative unintended consequences, it is no wonder that sustained change processes are rare or that constructivist theory has struggled to understand why continuity seemed to trump change.

Conclusion

The article set out with the aim of addressing the dilemma of codetermination in constructivist theorising about change by seeking to identify the motivations for agent-led change and to take a step in the direction of a more comprehensive constructivist understanding of why change appears to be difficult to explain for constructivists and difficult to undertake for agents. The article found that although arguably ‘constructivism is all about change’, constructivism has actually operated with a rather limited understanding of change, which in particular has not accounted for the emergent nature of change and has tended to focus either on the influence of structural factors or on change in identity or change in practice, but rarely on all three forms of change together. The introduction of ontological security as a key motivation for undertaking – or not undertaking – change-making action has not only provided a deeper understanding of why agents only sometimes choose to put their agency to use, but has also offered a linkage between the different change processes and forms of change that constructivist theory has engaged with separately. In doing so, the framework that has been presented here is able to account for influences that are not normally considered when trying to explain one of the most enduring questions of International Relations – how to make change happen – especially how to change dysfunctional practices. Moreover, by focusing on deterministic and stochastic factors rather than the conventional agent-structure duality, the framework is able to incorporate all conceptions of structure – including material, social, ideational, and discursive forms, and by introducing stochastic factors – it is able to theoretically account for all the ‘other stuff’, which clearly influence the ways in which we perceive ourselves and judge what constitute relevant action. This is important because as rather bluntly put by former US Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, ‘shit happens’, which inevitably impacts decisions and policy, but which is rarely addressed theoretically.

The focus on ontological security as a primary motivational factor for agents to use their agency strategically to alter the status quo, suggests that although human beings are endowed with agency and certainly appear to be more reflexive about their agency than is often acknowledged, their actual ability to utilise their agency is severely constrained by their need for maintaining ontological security. Once the scope of investigation is opened up to different forms of change and different processes of change and with a view of the social world as a trinity consisting of things that can be changed, things that can’t and things that just happen, the interconnectedness of the different processes and the extent of agent-level reflexivity prior to engaging in action that might lead to change move into theoretical view. For those with a normative agenda of ‘making change happen’ the new view of the field of change is certainly not a comforting one, because the model outlined in this article clearly shows the infinite number of possible obstacles standing in the way of sustained change.

Although the influence of the great variety of stochastic and deterministic factors certainly is important to take into account, the article has focused on the voluntaristic self-constitutive identification processes taking place at the agent level. The specific contribution here is that by focusing on these self-constitutive agent level processes and by introducing ontological security as a precondition for agency, the model does not rely on an essentialist conception of the Self, but is fully aware of the complex processes invoked in the constitution of the Self. Moreover, by combining several theoretical approaches such as SIT, narrative and practice theory, and by distinguishing between practice and action, the model is able to overcome the weaknesses of each of its constitutive elements. By opening up the agent level to focus on the self-constitutive agent-level processes as two inter-linked and mutually constitutive strategies for maximising ontological security, a new dimension has been achieved to add to our understanding of the prior constitutive processes and motivations that influence agents in making up their minds about how to put their agency to use.