Introduction: The transformation of order at sea

A substantial shift in the political evaluation of maritime space has taken place over the past decades. The oceans have re-emerged as a problematic space in international politics. Maritime inter-state rivalries in the Arctic, the South China Sea, and elsewhere question existing institutions and the law of the sea.Footnote 1 Transnational maritime crimes, including piracy, illegal fishing, trafficking of people, or smuggling of illicit goods increasingly occupy the international security agenda,Footnote 2 while the rise of China and India as naval powers questions the naval hegemony of the United States.Footnote 3

These new challenges have confounded the relatively settled international maritime order of the immediate post-Cold War period. A range of complex, interconnected, and globalised challenges have emerged, against which the established norms and practices have struggled to cope. This article demonstrates that we witness not necessarily a rise of disorder at sea, but the emergence of a new ordering processes. This transformation serves us as an empirical case to advance a new model for understanding international ordering.

Drawing on and advancing recent arguments for shifting the analytical perspective from order and change to processes of ordering, we develop a five-stage model of ordering practices in the light of empirical evidence drawn from maritime space. As a growing range of authors has shown, the move from noun to verb is productive as order can be analysed as an effect of ongoing ordering moves.Footnote 4 Order is an achievement, rather than a given. Ordering thus shifts attention to processes.

The model of pragmatic ordering advanced in this article proposes a much-needed heuristic for empirically studying such processes. Providing a synthesis of recent theoretical arguments and empirical global governance research, we identify five stages of an ordering process: problematisation, informalisation, experimentation, codification, and consolidation.

We illuminate each of these stages through empirical material from contemporary maritime ordering processes. We show how ordering emerges in response to new problems and is driven by practical activities geared at coping with and governing these. According to the model, once a new problem emerges (problematisation), informality allows for experimenting with new practices and developing new knowledge (informalisation and experimentation). Once these experimental practices become codified through ‘best practices’, ‘lessons learned’, and other instruments they increasingly settle (codification). If they resist controversy and contestation, they may produce a newly settling order. The principles of the new order may then further consolidate and spread through activities such as capacity building or the spread of best practices geared at educating and training practitioners in the new ways of handling things (consolidation).

The model of pragmatic ordering has the potential to make visible practical processes that have often flown beneath the radar of much International Relations (IR) scholarship. As a new way of studying the emergence of international orders, the model allows for consideration of informal and experimental forms of governance, and a better grasp of short-term and incremental political transformations, as well as bringing us closer to the practical activities of those engaged in building orders. We translate core insights from pragmatist philosophy and practice theory into a concrete model for the empirical study of ordering processes.

Our argument proceeds in three steps. In section two we introduce core insights from recent moves towards ordering in the IR literature and consider what understandings of order and change evolve from these. We pay particular attention to recent pragmatist and practice theoretical debates. Drawing on these core premises, we then outline the five stages of the pragmatic ordering model.

The remainder of the article then uses empirical material from the oceans to flesh out each of the stages of the model. We start out with a general discussion of the problematisation of maritime space implied by the new maritime security agenda. The next section zeros in on a paradigmatic case. We study the Western Indian Ocean in order to demonstrate how informality and experimentation drive the formation of new practices and the emergence of new orders at sea. We discuss how these new practices consolidate and spread. We end in discussing the specificities of the case. Since the power of paradigmatic case studies is not only to elaborate a model, but also to invite comparisons, we draw some general lessons for the maritime and other international orders.

From orders to ordering

The question of how to conceptualise and empirically study order and change remains one of the most pertinent theoretical challenges in IR theory. In particular, the recognition that international relations are subject to forms of order other than the modern international system of sovereign states has since the 1970s led to a growing range of conceptual proposals for (sub)orders including ‘regimes’, ‘regions’, ‘communities’, and other forms of normative and ideational structures.Footnote 5 Although one of the main intentions of introducing such concepts was to account for the emergence and transformation of orders, these proposals have been frequently criticised for offering too static a picture and remaining weak in understanding change.Footnote 6

Responding to such critiques, a wave of scholarship has drawn on recent ideas, concepts, and structural metaphors from social theory to advance alternatives. Inspired by pragmatist philosophy, practice theory, and related approaches, scholars have put forward relational and process-oriented proposals of order. ‘Assemblages’,Footnote 7 ‘actor-networks’,Footnote 8 ‘communities of practice’,Footnote 9 ‘fields’,Footnote 10 or ‘pragmatic networks’Footnote 11 present such new concepts of order.

What unites these proposals is that they question the usefulness of a binary division between order and change. They focus instead on the plurality of international order, including nestedness and overlap within and between orders, and the importance of ongoing processes of ordering within these. While not a homogenous circle of scholars who cite and follow each other's works or share a distinct objective, there are enough common ideas and a shared intellectual project to justify speaking of an emerging movement. The core ideas of the ‘ordering movement’ revolve around an emphasis on process, practice, and a pragmatist model of change.

Arguing against a dichotomy that contrasts stability and order with change and disorder, the call for ordering emphasises process. The new concepts of order aim to offer simultaneous accounts of change and stability recurring through processes of learning, evolution, innovation, or translation.Footnote 12 Order is hence neither seen as a given, nor as being continuously in flux, but as an achievement that requires enactment and reproduction. As Ray Koslowski and Friedrich Kratochwil argued early on, ‘any given international system does not exist because of immutable structures, but rather the very structures are dependent for their reproduction on the practices of the actors’.Footnote 13 Practices, understood as organised patterns of activities, become the core unit of analysis to understand order and the locus of change.Footnote 14 These notions, as developed in IR, conceptualise orders as patterns of practice and relations between them.

Ordering is a continuous process of adjustment. It requires innovation, but also repetition and maintenance work. It therefore implies a performative element; that is, how in and through action, new orders or new components of them emerge, and an ostensive element; that is, how that which has already been established, such as expectations or rules, is re-enacted and maintained in a situation. Order in this sense is reproduction and we can speak of a ‘settled order’ if the ostensive elements dominate. However, the indefiniteness and uncertainty of new situations generate context-specific reinterpretations of existing practices. These in in turn force and facilitate fresh approaches, which in their (at least partial) innovation, represent more than pure repetition.Footnote 15

Ted Hopf clarified that such a focus offers two potential understandings of change: one based on the principle of indexicality, the other based on deliberate reflection.Footnote 16 The principle of indexicality suggests that, since no two situations or actors are the same, any enactment of a practice in a given situation implies adjustment and hence transformation. This leads to an incremental understanding of change. Following Hopf, a second understanding is to see change as the outcome of deliberate practical reflection on how to proceed in the face of difference, an acceptable alternative, a crisis situation, or an innovation.Footnote 17 This brings to the fore a pragmatist understanding of change, which associates transformations with crisis moments; that is, when routines and existing rules are challenged through a new experience or a problem that existing practices are ill-equipped to deal with.Footnote 18

Our intention in the following is to take these key insights from the ordering movement forward. Yet, instead of adding further philosophical abstraction, our ambition is to turn them into a model useful for understanding how ordering occurs in actual international practice, such as those processes evolving in response to the maritime security agenda. Following Kevin A. Clarke and David M. Primo, models have to be understood as productive fictions.Footnote 19 They are ‘partial representations of objects of interest’ and their accuracy is limited.Footnote 20 A model hence does not offer testable propositions, nor should it be judged by its accuracy or truthfulness, but by its ‘elegance’ and how well it serves the purpose at hand.Footnote 21 As such, models operate as tools or ‘mediating instruments’, made of a ‘mixture of elements’Footnote 22 of ‘bits of theory’ and ‘bits of data’.Footnote 23

The model of pragmatic ordering presented in the following draws together the abstract premises from the ordering movement and empirical insights from current global governance research. It then refines the model through the analysis of a carefully chosen paradigmatic case from the reordering of the maritime space. Paradigmatic case studies are means for rendering phenomena such as ordering intelligible; they are, as George Pavlich puts it, ‘designed to reveal’ and particularly useful for developing models.Footnote 24 They allow for exploring mechanisms in depth and open up a space for comparison and contrast with other cases.

Pragmatic ordering: A five-stage model

On the basis of the core assumptions of the ordering movement, we propose a model in which new orders emerge in response to new problematic situations. Orders are constructed in practical activities geared at coping with and governing problems. They are hence the effects of the practical everyday ordering and coordination work of diverse actors dealing with problems. This work is not necessarily directed towards establishing formal and legal rules and is often informal and ad hoc in character. The principle of experimentation, of identifying and testing mechanisms and responses to cope with and order problems, structures such practices. Since new problems tend to involve high levels of uncertainty, pragmatic ordering relies heavily on epistemic practices, expertise, and knowledge production.

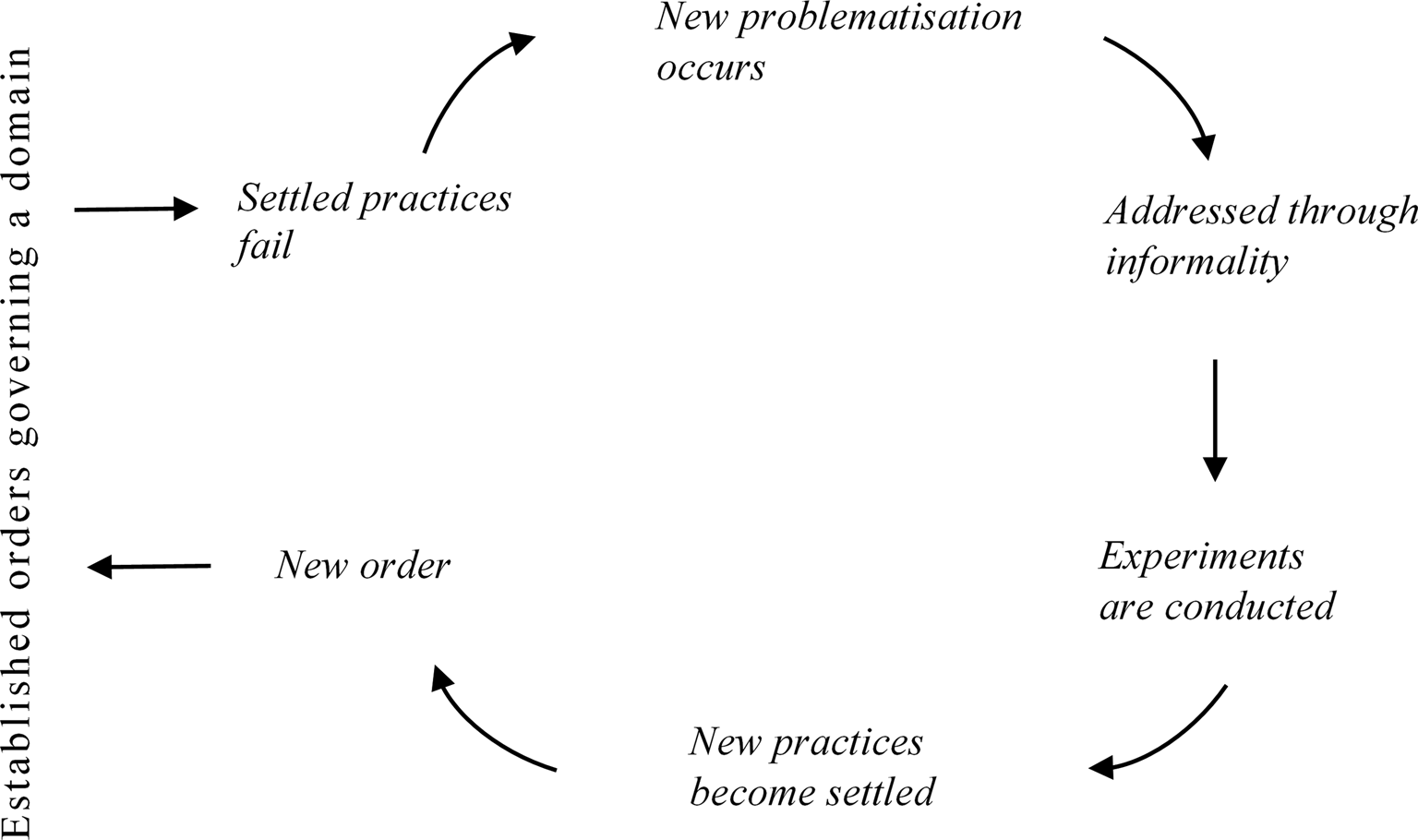

These dimensions together form a model of transformation. This begins with the emergence of a new problem. Established practices (routines, rules, and procedures) do not allow for the problem to be adequately addressed, while its novelty creates uncertainty. In the face of uncertainty, new practices and knowledge are required to grapple with the new problem. Actors resort to informality and experiment, since there are insufficient settled practices or formal rules to follow. Informality provides the space for experimentation. Conditions of informality provide the flexibility to try new solutions, include new or different actors but also to accommodate potential failures of experiments. Experiments require expertise, but in turn also lead to new knowledge as the outcome of the tests are recorded. Once a new set of practices is developed, these may increasingly become settled as actors strive to codify them in best practices, lessons learned, or practical agreements and install, maintain, and institutionalise them. In time, and if they resist controversy and contestation, these practices may instantiate a new order, which in turn becomes nested in or part of the established orders governing a particular domain (Figure 1). Each of these stages is further elaborated below.

Figure 1. Pragmatic ordering and change.

Problematisation

Orders develop along and in response to new problematisations. A problematisation occurs once collectives are concerned about a distinct situation, consider it problematic, and start to attend to it. In the process of ‘problematisation’, actors identify what the challenges are and how they might be addressed. Problematisation has been identified as a vital component of contemporary politics by pragmatist philosophy, in particular John Dewey's political theory. It is also a central theme in the work of Michel Foucault, and the driving idea in economisation and securitisation research. All of these approaches provide important clues into the logics of problematisation.

In Dewey's pragmatist political theory, politics arises primarily to solve problems of the commons. For Dewey the starting point for politics was the rise of what he called a ‘problematic situation’, which is a situation in which issues cannot be solved through private interaction.Footnote 25 When a problematic situation arises collectives face difficulties in proceeding by everyday routine and a process of major public adjustment is required.Footnote 26 For Dewey, such situations trigger a process of ‘inquiry’ geared at identifying the meaning of the problem and how it can be best addressed.Footnote 27

With many parallels to Dewey, Foucault develops an understanding of politics that takes problematisation as the starting point.Footnote 28 With the concept of problematisation he referred to the practical conditions and institutional mechanisms under which something is turned into an object of knowledge in response to a dedicated situation.Footnote 29 For Foucault, problematisation implies ‘the transformation of a group of obstacles and difficulties into problems to which the diverse solutions will attempt to produce a response’.Footnote 30 Problematisation refers to a process that starts out from the recognition that a common issue exists that requires political action. Uncertainty arises over how newly emerging issues should be dealt with and whether and how existing routines can be adjusted to do so. It evolves through attempts to connect issues, sort the problem dimensions, define its boundaries, and identify strategies and solutions to cope with it.

Both Dewey and Foucault hold that problematisation produces new practices.Footnote 31 As Foucault reasoned in Discipline and Punish Footnote 32 for instance, ‘the problematization of discipline established a deep set of motivating constraints that facilitated the emergence of new practices of punishment in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. These concrete new practices then reinforced the more diffuse disciplinary problematic.’Footnote 33

Problematisation has become a core theme in contemporary social research. In IR, a classic insight is John Ruggie's argument that international cooperation starts out from the negotiation of a collective situation whereby an agreement is reached between actors concerned about a particular problem.Footnote 34 For Ruggie such situations are inherently unstable in that they depend on available knowledge and the degree to which a given set of actors are concerned about it.Footnote 35

Problematisation is also the core logic applied in securitisation as well as economisation research. Here research investigates particular types of problematisation, namely how particular issues are rendered problematic in terms of the extraordinary responses of security or the market solutions of the economy.Footnote 36 As is shown in both of these research programmes, the actors of problematisation can be quite varied, with emphasis on industry, state administrations, civil society, and activists, but also scientists and analysts taking a pivotal role.Footnote 37 On the one hand, new problematisation processes provide the opportunity for new actors to take the stage. On the other, contexts of problematisation are not free of power relations, which implies that voices from certain positions will exert greater influence in defining a problem than others.

Informalisation and experimentation

Problematisation occurs when existing rules and procedures struggle to cope with a particular problematic situation. While problematisation might imply that actors work within existing practices and institutions, it may also open the space for reconfigurations in the ways in which this situation is addressed, including the emergence of novel roles for actors, or the entry of new and different actors. Such situations are often characterised by ‘informality’. Informalisation can be understood as the explicit attempt to develop responses outside of formal institutions and their rules.

As Friedrich Kratochwil notes, informal modes of world politics are increasingly important and widespread as the direct outcome of the proliferation of problems in quantitative terms, but also in consequence of their quality and complexity.Footnote 38 Substantial evidence supports this observation. The majority of post-Cold War political transformations are permeated by informal processes, such as soft law, contact groups, expert panels, or pragmatic networks.Footnote 39 Indeed, many recent global political innovations can be traced directly back to informal processes, often involving actors other than states.Footnote 40

Informality is an important lens through which to observe practices that fall outside publicly recorded formal and legalised international organisations and to empirically scrutinise the de facto actors participating in ordering. The focus on informality also brings to the fore the wider range of practical agreements that actors develop and rely on, such as Memoranda of Understanding, Codes of Conduct, or Best Practices.

Informality provides the basis for experimental politics and inquiry. It provides the space to try out new responses and include new and other actors in the process. As Dewey argued, problematisation is a spur to inquiry and experimentation.Footnote 41 In response to the uncertainty and novelty of a new problem, actors tinker, develop, and test new practices.Footnote 42 Recent research supports that theoretical argument. It shows how important the experimentalist logic is for many current global governance processes.Footnote 43 As Gráinne De Búrca, Robert O. Keohane, and Charles Sabel argue, experimentalist governance is driven by a logic of problem solving, probing, and testing.Footnote 44 While certainly involving diplomatic protocols, such processes tend to be more informal in nature and not focused on establishing rules and enforcing compliance. Experimentalism is hence a distinct mode of practice in international relations, characterised by tinkering, testing, and knowledge production.

Knowledgeable actors and epistemic practices are critical to understanding pragmatic ordering processes. Knowledge is needed not only to develop common understandings of the problem and new coping strategies, but also to record the success and failure of experimental solutions.Footnote 45 Knowledge production is thus a vital feature for understanding pragmatic ordering. Science and knowledge production should not be considered as falling outside an ordering process; they are an inherent part of it. Consider the importance of deterrence theory in shaping the rise of the nuclear order as a case in point,Footnote 46 or the rise of transnational terrorism as an international problem, which was, as Lisa Stampnitzky argues, closely linked to the emergence of the terrorism expert and the new discipline of terrorism studies.Footnote 47 Knowledge production is a core practice of ordering and of deriving and documenting the experiments conducted.

Codification and consolidation

The last stages in the model concern the processes through which the new practices become settled, start to become routine and are translated and adopted across local situations. Codification initially entails recording the results of experimental practice. These records are then stripped of histories of failures and condensed into documentations of what works.Footnote 48 Codification can take place through, for example, lessons learned exercises, the production of manuals, or the identification of best practices. Such texts then potentially start to be used in training, for instance in capacity building projects or in education. If widely adopted, such documents may come to function as customary or soft law. As Steven Bernstein and Hamish van der Veen note, best practices can become the de facto prevalent mode of governance in an issue domain.Footnote 49

Consolidating and installing new practices in such a way, potentially implies contestation and resistance. Even if evidence for the success of the new practices is overwhelming, as proposals for new ways of handling things they are likely to be challenged by those vested in previous ways of doing things. New practices will thus only settle and stabilise if they withstand such resistance and controversy, and this in turn is rarely a friction-free process. It is only then that the order fully consolidates. This might imply that a full settlement or consolidation is never reached if new practices meet ongoing resistance or refutation.

Summary

These five stages delineate the model of pragmatic ordering and outline an alternative for the study of emergence of orders on the basis of practice-theoretical and pragmatist assumptions.

As a model based on pragmatist and practice theoretical assumptions, it is not without limitations. Pragmatist approaches tend to be criticised for downplaying the importance of power.Footnote 50 As Deborah D. Avant stresses in responding to such critiques, while power does not necessarily feature as an explicit concept, the processes described in pragmatist analyses capture generative understandings of power and new forms of distributing power relations.Footnote 51

Discussing the role of power in conceptualisations of ordering, Stefano Guzzini suggests that, ‘even if power systematically refers to order, order does not need to be defined through power’.Footnote 52 In this sense, the model of pragmatic ordering evokes understandings of power, but does not define its core processes through it. In so far as the move to ordering implies a focus on process and change, it connects power not to domination and control, but to how the repositing through processes such as problematisation or informalisation generates new dispositions and forms of agency. The focus hence turns to forms of power that are generative in nature, and conceptualised through notions such as ‘deontic’, ‘performative’, ‘protean’, or ‘productive’ power.Footnote 53

Pragmatic ordering is, to reiterate, a model, and as such it is an abstraction. While this allows, as shown above and below, the illumination of certain processes and the integration of important existing empirical results from global governance research, it will be less useful for understanding others. The model is particularly suited to understand those situations where novel problematisations are in play and where considerable uncertainty on how to proceed arises. It is likely that in more settled, less uncertain and fluid situations, other forms of ordering might prevail, which in turn are also shaped by other dispositions and power relations.

Moreover, the model posits a linear logic. In practical terms, at each of the stages of the model there is a risk that the process breaks down. In practice we cannot assume a frictionless process. A shared problematisation might become challenged, contested, and renegotiated, or the agreement to resort to informality, experimentation, and knowledge production might collapse and actors may resort to other modes of ordering. The model then invites us to explore why and how such breakdowns might occur.

In the next sections we substantiate the model of pragmatic ordering in the light of a paradigmatic case of the transformation of maritime order. We demonstrate the heuristic power of the model and refine its elements through the empirical case. To do so we show how, in the past decades, the new problematisation of maritime security gradually emerged. Briefly investigating some of the core features of this problematisation, we zoom in on the case of the Western Indian Ocean to provide concrete illustrations of informalisation, experimentation, and consolidation.

Reproblematising the maritime

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s the oceans were not understood to be a problematic space requiring major international political attention.Footnote 54 In other words, a particular order governing the oceans had become increasingly settled. The rules and principles governing the oceans were established and agreed. The period from the 1970s through the 1980s saw the consolidation of a series of international maritime regimes, the most important of which was the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The development of these maritime regimes did much to embed commonly agreed norms and practices of political order at sea, whether in relation to the stewardship of marine resources or the free passage of commerce and the demarcation of territorial waters. At the same time, the end of the Cold War diffused the major naval confrontation of the period between the forces of NATO and the Warsaw Pact. Indeed, by the end of the Cold War, the sea appeared in many respects to have become an increasingly well-ordered space; characterised by legal regulation, normative agreement, and, generally speaking, pacific relations between states.Footnote 55

With the new millennium, the advent of novel international security challenges at sea led to a new problematisation of the oceans captured in the ‘maritime security agenda’. This problematisation has led to a wave of experimentation and practical innovation and with it new processes of ordering the sea. Below we provide a brief reconstruction of the maritime security problematisation, before zooming in on a paradigmatic region to discuss informalisation, experimentation, and codification in greater empirical detail. This is both to illustrate the core stages of pragmatic ordering, and to indicate how the model provides a heuristic for empirical research.

The rise of a maritime problem space

What can be described as the ‘maritime security agenda’, is a process through which the maritime space comes to be seen as inherently problematic. The emergence of transnational and substate maritime insecurities, as well as the re-emergence of geopolitical rivalries, contestation, and doubts over the legal regime at sea have created new uncertainties. These new insecurities disrupted the established maritime order of the immediate post-Cold War period. This in turn led to uncertainty over how newly emerging obstacles and difficulties should be dealt with and whether and how existing practices could be adjusted to cope with them. The new problematisation set in motion a complex ordering process at sea.

As several reconstructions have shown, maritime security as a concept and integrated set of problems has its roots in the rise of maritime piracy and incidents of maritime terrorism, beginning in the late 1990s.Footnote 56 More holistic thinking that conceives of the maritime as an interconnected security space develops from the mid-2000s. This was reflected in the growing attention given to maritime security issues both in the academic discourse and also in state administrations and international governance forums.Footnote 57

A major indication of this new problematisation of the maritime are the considerable efforts that international actors have devoted to the drafting of national and regional maritime security strategies. The United States published the first exemplar, when in 2005 the Bush administration concluded its work on the National Strategy for Maritime Security.Footnote 58 This document was the first strategy of its kind to explicitly conceive of the maritime sphere as a differentiated security space in its own right, identifying proliferation, terrorism, transnational organised crime at sea, piracy, environmental destruction, and illegal seaborne immigration as core challenges.Footnote 59

The US strategy has since been followed by a host of similar work by international actors. The UK, France, Spain, the European Union, the African Union, and the Group of 7 among others all completed such documents between 2014 and 2015. In common with the US strategy, these approaches endeavour to connect different maritime threats and to understand and engage with the maritime arena as an inter-linked security space rather than a series of discretely separated challenges. Security strategies function as mechanisms through which governments and other actors in the security sphere attempt to articulate and grapple with the problems in which they are engaged. Their recent proliferation is, at least in part, an indication of the extent of the new problematisation of the sea.

Features of the maritime security problematisation

As documented by the strategies, the maritime security problematisation contains at least four features. The first relates to an increasingly significant role of non-state actors in challenging maritime order. Non-state actors have always been prominent in the maritime arena, not least because of commercial interests in trade and resource exploitation. However, what is new – or at least newly resurgent – is the advent of non-state actors as security threats. Such threats fall into three main categories.

The first relates to extremist violence and terrorism. Such concerns were initially spurred by an al-Qaeda attack on a US warship in 2000. This raised fears of a rise in terrorist activity at sea, and led to a drive to secure ports and coastal areas from the incursion of terrorist groups and materials, including potentially weapons of mass destruction. Second, the rise of piracy in Southeast Asia, Western Indian Ocean, and Gulf of Guinea from the late 1990s onwards caused major concerns over the disruption of international shipping routes, the associated financial and human costs, and the need to formulate an effective response.Footnote 60 Finally, various organised criminal groups have utilised the sea to facilitate their activities, whether those be the trafficking of weapons and narcotics or the smuggling of people.Footnote 61 Such concerns have been heightened since the European migrant crisis in 2015 and the importance of maritime smuggling routes in facilitating these movements.

Another feature of the new problematisation relates to the expansion of the maritime stewardship agenda and an increasing tendency to link this to issues of economic and food security in coastal states and communities, as well as to the health of the global economy as a whole. At least 80 per cent of global trade by volume travels by sea, while marine resources such as fisheries and offshore oil are key economic assets.Footnote 62 Most obviously, piracy, criminality or other forces of maritime disruption threaten global commerce. More ambitiously, however, there is also a new recognition among coastal developing countries that the sustainable exploitation of marine resources offers a potential route to development, as captured by the concept of the blue economy. Moreover, that past neglect of these areas has led to their predation by outside actors, whether by fishing vessels or other external interests. In consequence, there has been an explosion of interest both in the marine economy itself, and also in the structures required to protect, manage, and police it.

A third feature relates to issues of human security; in the sense of the insecurities experienced by individuals and local communities. Human security issues penetrate much of the maritime security agenda. Migration into the EU across the Mediterranean for example is driven by human insecurities at home, while the action and process of migration is itself a source of often-deep insecurity to those participating in it. Fisheries protection and sustainability underpins the livelihoods of millions of people living in coastal regions, while these same groups are often the most vulnerable to the adverse impacts of climate change or marine pollution. Such concerns relate both to the security of the individuals and coastal communities themselves, but also to the role of human insecurities in facilitating the emergence of activities such as piracy or criminality as alternative sources of employment in regions of significant economic deprivation or breakdown.Footnote 63

The final feature concerns the rise of geopolitical challenges and new competition at sea, induced by the rapid increase in naval capacity of states such as India and China.Footnote 64 This rise of new naval powers has been accompanied by a proliferation of relatively cheap and easy to access maritime warfare technologies such as anti-ship missiles and submarine forces to a much wider range of state (and sometimes non-state) actors than was the case in the past. This in turn has challenged the competitive advantage enjoyed by the long dominant naval forces of the West, at least in certain specific geographic domains.Footnote 65 Concurrently, the period since 2001 has seen the emergence of new flashpoints of geopolitical tension and territorial competition at sea, including particularly the South China Sea, and nascently the Arctic.Footnote 66 These developments have gone along with the fundamental contestation of key norms governing the sea established by the UNCLOS, in particular through China's claims in the South China Sea.Footnote 67

Taken together, these features give us a good grasp of the advancement of a new problematisation of the sea. We now turn to the second stage of the model and review the manner in which international actors are responding to this.

The paradigmatic case

In the following we zoom in on the paradigmatic case of the Western Indian Ocean – the maritime region reaching from South Africa in the West to India in the East, and Yemen and Pakistan in the North.

Paradigmatic cases are useful for rendering particular phenomena intelligible; akin to reasoning by analogy.Footnote 68 We here draw on the paradigmatic case of the Western Indian Ocean to illuminate the subsequent four stages of our model. While problematisation is a more overarching phenomenon and as shown above can be usefully reconstructed in a more abstract manner, understanding the later stages requires to zoom in closer on a situation in which problematisation spurs particular practical responses.

The Western Indian Ocean is a useful paradigmatic case since it functions as a microcosm of the global maritime space and has been a pivotal region for the new problematisation of the sea. The region is an area of critical global geostrategic significance and is internationally recognised as presenting a diverse and complex range of maritime security challenges that incorporate all the themes we identify above.Footnote 69 It is the location for major geopolitical and naval interactions between a diverse range of states; it has seen the most virulent outbreak of piracy in the modern period; it borders hotspots of terrorist activity in Somalia, Yemen, and the wider Middle East; it incorporates key trafficking routes for narcotics, humans, and arms; and has played host to rampant illegal fishing activities, and other forms of organised crime.

In addition, and in so far as a paradigmatic case ‘simultaneously, if paradoxically, emerges from, and constitutes, the set to which it belongs’,Footnote 70 the Western Indian Ocean is also host to significant processes of informalisation, experimentation, and codification processes. The case is hence ideally suited to further illuminate how these processes unfold and hang together. The Western Indian Ocean has been a crucible of innovation in maritime security with multiple experiments leading to practices that not only structure interactions in the region itself, but are increasingly indicative of a new global ordering process. The developments in the region hence give us a case of prototypical value both for understanding the specificities of the ordering implied by the broader maritime security problematisation, but also for the general model of pragmatic ordering.

Informality and experimentation in the Western Indian Ocean

What practical responses has the problematisation of maritime security triggered in the Western Indian Ocean?Footnote 71 In the following we show how problematisation gave rise to a host of informally derived experiments. We investigate three of the experiments that are observable in the region:Footnote 72 (1) the development of new coordination mechanisms for naval forces; (2) the creation of an experimental governance mechanism to coordinate actors and establish practical rules; and (3) the introduction of a new form of law enforcement structure. Each of these responses are informal in that they operate with a minimum of rules, and neither rely on formal legal agreements nor are organised in the frame of established institutional settings. They are experiments in that they test new means of responding to maritime insecurity. They draw on the reconfiguration and translation of practice from other fields, new actor configurations, and the introduction of new technologies to the maritime. Together they provide us with indications of what forms of informality and experimentation might be spurred by problematisation.

New means of military coordination

Naval responses to maritime insecurities in the region, in particular piracy off the coast of Somalia, have led to remarkable informal and experimental forms of military coordination. These work in the absence of any shared command structures or formal commitments of states. Instead, coordination is facilitated trough frequent information sharing meetings as well as information technology. As Sarah Percy notes, these novel mechanisms are not adequately grasped by any familiar notions such as alliances, coalitions, or partnership and are truly experimental.Footnote 73

The first precedent for such a coordination structure was set when a multilateral naval operation was installed in the region in 2002 as a response to concerns over maritime terrorism. The so-called Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) was a new type of multi-naval arrangement.Footnote 74 At its launch five states were part of the arrangement, but the number grew quickly to 31 nations, including regional powers such as Pakistan, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. The CMF has a flexible and informal structure. It works ‘without long-term binding commitments’ and ‘rotates command among member states every couple of months’.Footnote 75 The flexible and informal character is well captured on the CMF website:

Participation is purely voluntary. No nation is asked to carry out any duty that it is unwilling to conduct. The contribution from each country varies depending on its ability to contribute assets and the availability of those assets at any given time. The 31 nations that comprise CMF are not bound by either a political or military mandate. CMF is a flexible organisation.Footnote 76

The main tasks of the CMF are carried out by a range of task forces commanded by member states in rotation, with the US naval headquarters in Bahrain providing the basic command infrastructure. The activities that navies engage in range from ‘assisting mariners in distress, to undertaking interaction patrols, to conducting visiting, boarding, and search-and seizure operations, to engaging regional and coalition navies’.Footnote 77 The creation of the CMF represents an initial case for how the emerging maritime problem space led to experimentation with a new type of military operation and a standing multi-naval constabulary force in the Western Indian Ocean. CMF became one core element in the maritime security structure of the region, and when from 2008 piracy became a major issue it was one of the forces that reacted to it by creating a dedicated task force.

To respond to piracy two additional multilateral forces started to operate in the region. NATO launched Operation Ocean Shield and the EU created EUNAVFOR Atalanta.Footnote 78 Also a broad range of state actors, including China, India, Japan, South Korea, and Russia began to send naval vessels. The UN Security Council gave these navies a broad mandate to operate in the area and also in Somali territorial waters. Yet, counter-piracy was not a formal UN naval peacekeeping mission, and there were no proposed joint or integrated command structures. Instead, drawing on experience with the CMF, naval actors developed an informal coordination mechanism.

The so-called Shared Awareness and Deconfliction Mechanism (SHADE) was established in 2008 to conduct informal discussion and de-conflict the activities of the diverse nations and organisations involved in counter-piracy operations off the Horn of Africa.Footnote 79 Initially, SHADE included only the CMF, EU NAVFOR, and NATO participants, but it rapidly expanded to incorporate all navies active in the area, including those of China, India, Japan, Russia, South Korea, and Ukraine. By 2012, 14 organisations and 27 countries were active SHADE participants.Footnote 80 The novelty of the SHADE arrangement, and the opportunities it offered for addressing common problems, was recognised by a representative of the US State Department, who described the organisation as:

not … a coalition [which] implies [centralized] command and control. Instead [there are] three organized missions and a wide variety of national independent deployers who have simply chosen to collaborate. No one is in charge. No one has command. They deconflict and operate constructively, and that's a new model of operation. … many countries are voluntarily collaborating to secure the maritime space.Footnote 81

One of the most successful measures developed by SHADE was the Internationally Recommended Transit Corridor (IRTC) – a demarcated patrol area in which the coverage by naval vessels was maximised through computer modelling.Footnote 82 The IRTC not only reduced the size of the area of operations, but also allowed ‘more concerted task-sharing between the three multinational deployments’.Footnote 83 The basis for the Corridor's operation in practice is the IRTC Coordination Guide, ‘a gentlemen's agreement to keep the number of ships per area within the IRTC to a minimum’.Footnote 84

A second noteworthy initiative facilitated by SHADE was the creation of a new information-sharing platform called MERCURY. MERCURY allows various actors – including national navies, civil information sharing centres, and law enforcement agencies – to communicate with each other through synchronous text-based chat, with a live feed on naval operations and piracy incidents providing real time data to all participating actors.Footnote 85 ‘This secure but unclassified internet-based communication system, … works as a neutral communications channel and allows all SHADE participants to coordinate together in real time.’Footnote 86

The CMF force structure, the SHADE forum, the transit corridor optimised through modelling, and the information sharing system, are four novel ways of how to coordinate military activity between nations and to increase the success rate of responding to maritime security incidents. They were all launched in an informal setting, are experimental in character, and have endured over time.

An experimental informal governance mechanism

By 2008, piracy in the region had become a problem of significant proportions – a threat to the delivery of aid to Somalia as well as to international shipping. The question arose as to which international governance body could oversee, coordinate and legitimise counter-piracy activities. It quickly became apparent that the existing institutional set up was struggling to address the problem. The UN Convention of the Law of the Sea defined piracy as a criminal activity taking place on the high seas. It gave any state the right to arrest and prosecute pirates but did not give anyone the obligation to do so. The IMO, the UN body in charge for regulating the shipping industry, discussed the issue, but lacked the means to authorise or organise any larger-scale multilateral response. The issue was transferred to the UN Security Council. A series of UN Security Council resolutions called upon states to protect shipping and to cooperate in doing so. But it remained unclear which body could develop a strategy and coordinate the increasing number of different actors involved, in particular flag states, regional states, as well as the shipping industry.

The response was the creation of a new informal governance mechanism, the Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia (CGPCS). The group has been described by scholars variously as an ‘international cooperation mechanism to act as a common point of contact’, as a ‘forum where a considerable number of States meet to discuss issues related to the effective repression coordination mechanism’,Footnote 87 ‘more as a transnational network than governance, as it lacks any direct regulatory power’,Footnote 88 or as ‘a voluntary mechanism for states to collectively address maritime piracy’.Footnote 89

A former chairperson of the group described it as a ‘diplomatic initiative’ that grew into an ‘expansive, elastic, multi-faceted mechanism’ that ‘has acted as a lynchpin in a loosely structured counter-piracy coalition’ but that has ‘no formal institutional existence’.Footnote 90 Another described it as ‘an inclusive forum for debate without binding conclusions’ without ‘any real structural formality’.Footnote 91 And, indeed, the group has been described by the participants themselves as ‘a laboratory for innovative multilateral governance to address complex international issues’.Footnote 92

The group as such is a fascinating case of informality that evolved through a series of experiments and exerted significant structuring power over the counter-piracy response. Created as a coordination body by 15 states in 2009,Footnote 93 it was originally meant to be a limited contact group, following the templates of other state groupings regularly formed to address international crises.Footnote 94 But the group very quickly evolved into an entire new form. The CGPCS became a process-driven, informal organisation working on principles of inclusivity rather than representation. It grew in membership, with over eighty states and twenty-five international organisations participating. Also, non-governmental organisations started to attend, as did shipping industry associations. Despite its size, the CGPCS worked with a minimum of rules, which left many of its procedures to the discretion of a rotating chairmen, while the work was decentralised in a series of working groups.

The main objective of the group was to serve as fora for the exchange of information concerning ongoing operations, to develop a shared understanding of the problem of piracy, to discuss new proposals for responses, and to develop a concerted strategy. Although the decisions of the CGPCS are non-binding in nature, they exert a substantial orchestrating effect.Footnote 95 The group experimented with coordination mechanisms, such as a shared legal toolkit or a coordination matrix and database.Footnote 96 In particular it has facilitated the development of a legal system on the basis of memoranda of understanding by which piracy suspects could be arrested, transferred, prosecuted, and jailed across different jurisdictions.

A new legal infrastructure

The cross-jurisdictional legal structure developed to prosecute pirates is another noteworthy experiment in regional maritime security.Footnote 97 It arose from the practical problem that most of the states providing naval forces for counter-piracy operations were unwilling to prosecute detained piracy suspects in their own courts for legal, financial, or political reasons, despite being given the right to do so under UNCLOS. To avoid suspects simply being released, international actors debated various options for prosecuting pirates, including the proposal for establishing an international court in Tanzania.Footnote 98

The majority of actors engaged in counter-piracy, however, preferred a more informal and less institutionalised system that would not set legal precedents or lead to a formal institution. This system was developed within the legal working group of the CGPCS. As a former chairman of the legal working group phrased it, the group developed

a unique legal and practical framework for prosecuting pirates in the region, also known as the Post Trial Transfer system. The framework allows arresting states to transfer apprehended suspected pirates to littoral states, including Kenya and Seychelles, for prosecution, and, if convicted, to have the pirates transferred to Somalia (Somaliland) to serve their prison sentence.Footnote 99

The bases of the system are bilateral Memoranda of Understandings. For international criminal lawyers the cross-jurisdictional coordination framework was a hallmark for inventing transnational law enforcement on the basis of informal understandings and practical coordination.Footnote 100

Summary

The three processes detailed above are examples of experiments that have been engendered by the failure of existing practices. The provisions by UNCLOS and the mechanisms developed within the IMO were insufficient to address the situation. Rather than creating a formal organisation such as a new naval operation, an international court, or orchestrating a response through UN structures, a loose and informal set of multilateral activities were developed to respond to multiple maritime insecurities, but particularly the piracy problem.

The outcome has been the experiments discussed above. It is noteworthy that these experimental activities have not receded with the dissipation of the piracy problem in the region from 2012. Indeed, there are clear indications that they are beginning to consolidate into settled practices and become routine. In the next section, we show how these new practices have become codified through lessons learned and strategy documents, and how capacity building activities increasingly install and embed these into the littoral states of the region and elsewhere.

Codification, consolidation, and global translation

The last recorded major successful piracy attack in the Western Indian Ocean occurred in May 2012. Eight years later, the measures discussed above remain in place, and in many ways have consolidated. This is the outcome of increased explicit efforts to install these practices among the littoral states, and hence embed them in the region as a whole, but also to expand these practices to other maritime regions.

Codification, consolidation, and capacity building

Both SHADE and the CGPCS engage in ongoing monitoring and evaluation of the effects of their activities, recorded for instance in the frequent communiques of the groups. In addition, several actors began to devote significant attention to recording experience and conducting lessons learned exercises, indicating a substantive process of codification. In 2014 the CGPCS initiated a major ‘lessons learned’ exercise. Following its experimental spirit, the group commissioned a think tank and a university-based researcher to carry out the project. The objective was to record the experience of the group and distil lessons and best practices through a participatory approach. ‘Lessons learned’ has become a standing item on the agenda of the groups plenary meetings.Footnote 101 Several actors including various states, NATO, and the shipping industry either contributed to the CGPCS process or conducted their own lessons learned exercises.Footnote 102 The goal of these exercises has been to capture the practices installed, why they succeeded in containing piracy, how they could be maintained, and whether and how they could be replicated to address other maritime security problems and regions.

Consolidation occurred also through an effort to transfer the responsibility for maintaining the by now settled practices to regional actors in order to make them enduring and even permanent. In consequence, international actors continued to experiment, and, in so doing, shifted the focus of their activities towards the institutionalisation of the new practices in the region. In particular, new experiments have been conducted in capacity building.Footnote 103 These initiatives are meant to enable littoral states to take over key tasks from the international community. They also represent an effort to incorporate and address some of the broader issues raised by the maritime security agenda, addressing in particular the economic and human security dimension.

Capacity building is geared at training practitioners of countries in the new practices. Such activities have been part of counter-piracy operations in the region from the very beginning. Regional actors were trained in systems such as MERCURY, and increasingly given major roles in the CGPCS. Capacity building was notably important to enable littoral states to play a part in prosecuting piracy suspects as part of the legal transfer system.

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), for instance, created a new programme to undertake such capacity building for maritime security.Footnote 104 The focus soon became broader and programmes evolved into training regional diplomats and maritime security actors in order to allow them to take over the core tasks of maintaining the regional structures. The IMO and the EU, but also states such as the US and Japan invested substantially in capacity building operations. Yet, such capacity building efforts have not been without contestation and present and ongoing challenge, which suggests that the new practices are not fully consolidated.Footnote 105

Translating the new practices to other situations

In what ways does this consolidation process also affect other regions? There are numerous indications that the results of the experiments in the Western Indian Ocean have also been translated to other regions and situations and hence have a wider, global ordering effect. Core practices from the Western Indian Ocean region have been adopted elsewhere, and many of the developments are paradigmatic of wider trends in the emergent maritime security agenda.

In the Gulf of Guinea, for example, a governance mechanism similar to the CGPCS, the so-called G7++ Friends of the Gulf of Guinea Group, was established in 2013. In 2018 a contact group was created to coordinate responses to piracy in the Sulu and Celeb Seas, which took the CGPCS as a template. The SHADE coordination model has been adopted in other regional contexts. A similar mechanism has been introduced in Southeast Asia, as well as in the Mediterranean as a means to coordinate the fight against human smuggling.Footnote 106 The flexible military operational structures that allow for the participation of non-member states is in use in various naval operations, such as NATO's Mediterranean naval counterterrorism operation Active Endeavour. Capacity building for maritime security has become a global enterprise. A good indicator is the evolution of the UNODC's programme: Starting out as the Counter-Piracy Programme operating in four countries (Kenya, Somalia, Seychelles, Tanzania), it has since has evolved into the Global Maritime Crime Programme active in capacity building around the world.

These are examples of how the practices developed and tested in the Western Indian Ocean became replicated across the globe. They form part of the new pragmatic ordering process at sea and signify an increasing consolidation of these activities and practices beyond the Western Indian Ocean region for which they were originally developed.

Conclusion: Ordering and the new pragmatic order at sea

The problematisation of the maritime security agenda has spurred a pragmatic ordering process through which the oceans are increasingly governed differently. It presents a forceful, paradigmatic case for how problematisation, informality, and experimentation lead to new orders through codification and consolidation. It is the power of paradigmatic cases to illuminate and elaborate,Footnote 107 and this was the primary intention of our empirical discussion; it was to show how the model of pragmatic ordering can shed new light on global ordering processes.

Informalisation and experimentation are observable master trends of world politics, and are increasingly recognised as such. The model of pragmatic ordering allows us to put these trends in context and relate them to the occurrence of ordering. The model hence gives us a new tool to study change in international orders. It allows to translate the often-intricate philosophical ideas of pragmatism concerning the importance of problems, inquiry, and change, but also the insistence of practice theories to pay more attention to the mundane, practical, often informal activities into a concrete model useful for empirical research on ordering.

Problematisation processes are critical in this regard. The maritime security problematisation came along with the identification of new and inter-related security challenges at sea. Uncertainties over how to deal with these challenges opened space for informal and experimentational processes to occur. New kinds of military cooperation, the use of technology, experimental governance formats, and a complex law enforcement system were the outcome.

Nonetheless, it is likely that not every problematisation will favour or trigger the pragmatic ordering process induced by the model. Indeed, a case can be made that ocean space is particular prone to such a form of problematisation. Given the terra-centrism of much of world politics, there might be a case that the oceans operate differently. And indeed, navies historically have stronger inclinations to cooperate, not the least given the fluidity of ocean space and extreme weather conditions. The status of ocean space in world politics, without doubt, represents particular conditions, and as such it is an ideal paradigmatic case for advancing the pragmatic ordering model.

Yet, the core driver of the model is the rise of new problematisations induced by the failure of existing ways of handling things. In the case of counter-piracy off the coast of Somalia, this was not the lack of legal provisions, but the failure of existing institutions, centrally the UN system, to organise a practical response. Piracy is interesting in this regard, since it is also a case of an old international problem, which resurfaced, raised new uncertainty, and hence required a new and different response.Footnote 108 New uncertainty and the failure or absence of settled practices hence provides the core conditions for the model to set in motion.

Paradigmatic cases, like our discussion of the maritime security ordering process, are also meant to be of prototypical value and open up comparisons.Footnote 109 We expect the model to be a revealing heuristic tool if applied to other cases and compared to the maritime security case. We expect the model to provide valuable insights in how newly emerging issues and problems challenge existing orders and trigger new ordering process.

A range of contemporary issue areas will benefit from being researched through these lenses. State failure, transnational terrorism, cyber security, artificial intelligence, or autonomous weapons represent emerging global problematisations that induce significant ordering processes. Like the maritime security problematisation, these are recognised problems that are inherently complex, transnational, and cross-jurisdictional in the way in which they manifest, and in which pragmatic responses are engendered both as a function of their nature and as a consequence of the specific territories in which they take place.

Yet, the pragmatic ordering model will also be useful for historical research and investigations into how orders, such as the international humanitarian order have evolved through problematisation, informality, and experimentation and have become settled.

Comparing these instances with our paradigmatic case will contribute to refining the model and better identify its scoping conditions. Key questions relate to the situations and particularities of the problematisations required to trigger pragmatic ordering processes, and the circumstances under which the stages of the model could break down. These include when and how informality and experimentation fail due to controversies, how new practices fail to settle and the ways in which they may be contested or resisted and hence consolidation does not take place. Investigating such issues will also bring questions of power, in particular the power to shape the outcomes of experiments, or to refuse or resist consolidation more strongly to the fore than it is currently captured in the model.

As James G. March and Johan P. Olson argued, ‘the historical processes by which international political orders develop are complex enough to make any simple theory of them unsatisfactory’.Footnote 110 The model of pragmatic ordering developed in this article does not pretend to offer such a simple theory. As a model its goal is to organise, illuminate, and provide a heuristic for exploration, not a theory to be tested.Footnote 111 Likely, there are other mechanisms of change and ordering at play, within which (maritime) orders are nested, and that are nested within it; and other models and conceptual apparatuses are required to describe them. The model of pragmatic ordering is, however, an important addition to our repertoire of models how (global) ordering occurs. It is a model that brings problems, informality, and experimentation to the fore.

Acknowledgements

This article has benefited from feedback provided at seminars at the Department of Politics and International Relations, Cardiff University, the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, the Global Insecurities Centre, University of Bristol, and the Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen. For comments and suggestions that have greatly improved the manuscript we like to thank in particular Emanuel Adler, Rebecca Adler-Nissen, Niklas Bremberg, Niels Byrjalsen, Jeff Colgan, Jeremie Cornut, Alena Drieschova, Frank Gadinger, Eric Herring, Peter Marcus Kristensen, Daniel Nexon, Jon Pevehouse, Jan Stockbruegger, Ole Wæver, Tobias Wille, Yongjin Zhang, as well as the reviewers and editors. The paper has benefited from funding provided by the British Academy (GF16007), the Asia Research Institute of the National University of Singapore, the Economic and Social Research Council UK (ES/S008810/1), and the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs under the AMARIS grant administered by the DANIDA Fellowship Centre. We further thank Daniela Dominguez for editorial assistance.