Introduction

Can we graze livestock sustainably as operating environments shift due to climate change? The question engages a range of scholars working in different paradigms: experimental and farm-scale management scientists, biologists and ecologists, rural sociologists, agricultural economists and agri-business scholars. Debates often emerge among those working on such complex questions, sometimes over highly-theorized archetypes. A good example is the recent battle over whether land-sharing or land-sparing farming practices are better for biodiversity, food security and other desirable outcomes (Tscharntke et al., Reference Tscharntke, Clough, Wanger, Jackson, Motzke, Perfecto, Vandermeer and Whitbread2012; Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Abson, Butsic, Chappell, Ekroos, Hanspach, Kuemmerle, Smith and Von Wehrden2014a). It is not surprising that simplified archetypes can provoke conflict: the wide range of specific practices considered consistent with any given archetypal regime are likely to have varying results across diverse landscapes, scales, climates and agricultural operations. There is rarely one answer that fits everywhere, but rather many that ‘depend’.

While archetypes can be problematic, they are often generally accepted as heuristic tools along the path to better practices. Archetypes are not mutually exclusive in theory nor are they generally seen or implemented in a ‘pure’ state in practice, even were that desirable. In fact, research on farmer adoption shows us that the capacity to trial a new practice on a small part of a farm is critical in the uptake of that practice (Vanclay, Reference Vanclay1992; Pannell et al., Reference Pannell, Marshall, Barr, Curtis, Vanclay and Wilkinson2006). Farmers are natural scientists, and like to experiment and observe, but they are also generally risk averse (Greiner et al., Reference Greiner, Miller and Patterson2008). As such, whole-of-farm conversions to new commodities or practices are uncommon without substantial evidence about the benefits of the new practice, whether academic in origin or from agricultural advisors or fellow farmers. There is some evidence from the USA that research in agroecosystem approaches such as rotational or regenerative grazing is federally underfunded in relation to that related to agricultural inputs (DeLonge et al., Reference Delonge, Miles and Carlisle2016).

One of the most persistent debates in grazing systems involves the utility of adaptive grazing practices, such as Holistic Management™ (HM), developed by Allan Savory to mimic the intense yet brief grazing pressure of large herds in parts of Africa (Savory and Parsons, Reference Savory and Parsons1980; Savory and Butterfield, Reference Savory and Butterfield1999). Proponents observe that such ‘hoof and tooth’ pressure, in the wild or with managed livestock, improves water and nutrient cycling and thus land cover. The practice relies on holistic-goal setting, and adaptive decision-making: for instance, when to move animals through a large number of small paddocks to foster high intensity grazing pressure followed by long rest and recovery periods (see Box 1; Stinner et al., Reference Stinner, Stinner and Martsolf1997; Savory and Butterfield, Reference Savory and Butterfield1999). Science is divided on the utility of such practices: experimental scientists see no benefits from the constituent practices in controlled experiments, particularly not the scale of production increases promised by Savory, while many management-oriented agricultural, ecological and social scientists report benefits at the farm scale (Nordborg and Röös, Reference Nordborg and Röös2016).

Box 1. What is HM?

Holistic Management is an adaptive and highly flexible practice, and such characteristics (as well as varying language) are part of the challenge of studying it. In 1980, Savory and Parsons laid out two key ecological principles behind the ‘Savory Method’:

1. Animal impact does not degrade rangelands but rather expedites plant succession by improving water penetration as a result of ‘hoof action’

2. Carefully controlling the time that animals are grazing an area and leaving time for pasture recovery, is what avoids plant stress and thus degradation.

From this basis emerged seven applied principles (Savory and Parsons, Reference Savory and Parsons1980):

1. Versatility—no prescribed grazing system can have success in varying conditions.

2. Herds—stock must be grouped and run together to achieve and control impact.

3. Movement—stock should only be left on pasture for a short time (e.g. 1–5 days), before resting, which generally means smaller field units and more fencing. Slower pace is possible in non-growing seasons.

4. Rest—native pasture should be rested from 1 to 2 months after grazing, shorter for improved.

5. Increase stocking—carefully raise stocking rate to match land base. No guidance was given in 1980 about ideal rates, but later work suggested stocking could be doubled from that possible with continuous grazing (i.e. set stocking).

6. Fencing—fencing designs such as wheel-like ‘cells’ (in flat country) can be used to make rotation efficient and ensure access to water, though is optional.

7. Whole-ranch planning—the above must be carried out as appropriate to planning that includes all farm aspects, including business management.

The method has evolved since 1980, and been codified including training via the Savory Institute and Holistic Management International. Today, it is characterized by principles one to four, which are those most matching the ecological principles, guided by holistic planning (principle seven) that covers production, ecosystem and lifestyle goals. Systematic monitoring was introduced later (Savory, Reference Savory1983), correcting perceptions of HM as ‘time-controlled’. Rather stock should be moved to respond to plant growing rate and available forage in relation to the planned return of stock to that pasture. Optional wheel-like fencing designs, so called ‘cell grazing’ has been a spinoff area of research, but are not possible in many rangeland settings and Savory stepped away from this principle (Savory, Reference Savory1983).

Increasing stocking rate (principle five) has been the most controversial, and also varies in practice. While this claim inspired much experimental research, there is little evidence that this is what inspires uptake by ranchers. Some farmers are interested in using less of their land, for instance, for the same stock, allowing for conservation efforts. While Savory and Parsons do not advocate destocking that is one of the adaptive options practiced by HM farmers during drought in places such as Australia as they match stocking to ground cover.

Polarization describes the way that opposing views can drive people further apart, like opposing magnets. Eventually, consensus is reached on most questions of public good, but until then, the scientific literature is often characterized by internal divisions (Shwed and Bearman, Reference Shwed and Bearman2010). There is a persistent disagreement about whether HM ‘works’ based on the varying interpretations and apparently growing entrenchment of competing understandings. Complicating the mix is the chaos of terminology in play for HM and related systems (McCosker, Reference McCosker2000), and the salesmanship of Savory himself, who has recently and controversially claimed that HM can ‘reverse climate change’ (Briske et al., Reference Briske, Bestelmeyer, Brown, Fuhlendorf and Polley2013). The implications of this disciplinary tug of war extend beyond the scholarly community, where it simply hampers collegiality and interdisciplinary collaboration, to potentially distract from progress and policy on sustainable grazing.

HM is a whole-farm management process that is currently a fringe practice (Sherren et al., Reference Sherren, Fischer and Fazey2012; Roche et al., Reference Roche, Cutts, Derner, Lubell and Tate2015), in part because it cannot be ‘trialed’ before full conversion. HM often requires explicit training in a new way of thinking about the farm, to learn to set and monitor goals that reach beyond production to social and environmental aims, and a significant up-front outlay in farm infrastructure (water points, fences, solar power, etc.) to enable carefully controlled grazing and rest periods. Entrenched binary positions among scholars do not well serve this practitioner constituency, which—thanks to the dominance of grazing landscapes worldwide (Asner et al., Reference Asner, Elmore, Olander, Martin and Harris2004; Foley et al., Reference Foley, DeFries, Asner, Barford, Bonan, Carpenter, Chapin, Coe, Daily, Gibbs, Helkowski, Holloway, Howard, Kucharik, Monfreda, Patz, Prentice, Ramankutty and Snyder2005)—together represents a powerful driver of global environmental conditions. The Savory Institute only exacerbates the problem when it includes only research that indicates benefits from HM in its ‘research portfolios’ (Nordborg and Röös, Reference Nordborg and Röös2016). Policy-makers seeking to facilitate sustainable grazing, such as via payments to offset transition costs, are understandably left confused (Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Maczko, Hidinger and Ellis2016).

We use scientometrics to systematically explore the rift around HM and similar practices that has been described anecdotally and debated in numerous reviews (Briske et al., Reference Briske, Sayre, Huntsinger, Fernandez-Gimenez, Budd and Derner2011; Teague et al., Reference Teague, Provenza, Kreuter, Steffens and Barnes2013; Carter et al., Reference Carter, Jones, Brien, Ratner and Wuerthner2014; Garbach et al., Reference Garbach, Milder, DeClerck, Montenegro De Wit, Driscoll and Gemmill-Herren2017; Nordborg and Röös, Reference Nordborg and Röös2016). Specifically, we delineate the HM scholarship as represented in Web of Science, and use those records to: (1) describe the impact that Allan Savory has had on grazing scholarship since the publication of The Savory Grazing Method, in 1980; (2) show how attitudes on HM differ by field and over time; and (3) reveal clusters and polarization in papers on HM as indicated by the similarity of their bibliographies. We conclude with a set of reflections on the root causes of polarization, including the challenges it presents and pathways to more integrated approaches to studying and making decisions around grazing systems.

Methods

Scientometrics is a practice aimed at measuring scientific influence, and is typically carried out upon cohesive or well-defined rather than diffuse (sensu Whitley, Reference Whitley1984) fields or concepts. It is not easy, however, to delineate the scholarly discourse around holistic management for such analysis. First, scholars in disparate disciplines make reference to HM and use varying terminology when doing so, including using aspects of HM to refer to the practice as a whole (i.e., cell grazing, managed intensive grazing, time-controlled grazing, high-intensity short-duration grazing, adaptive multi-paddock grazing) (McCosker, Reference McCosker2000). Additionally, some disciplines, such as management and computer science, use ‘holistic management’ to refer to management approaches unrelated to livestock and Allan Savory's methods.

We thus implemented a comprehensive literature search of HM by performing a cited reference search in Web of Science (WOS) of all publications authored by Allan Savory, the ‘father’ of HM. Bibliometric analyses to track the influence of a single individual or publication series are rare in the literature, but occasionally warranted (e.g. Vasileiadou et al., Reference Vasileiadou, Heimeriks and Petersen2011; Skupin, Reference Skupin2014). We selected WOS over PubMed and Scopus, two other citation databases, because the WOS cited reference search resulted in the most complete set of Savory's publications (and thus a sizeable set of records citing those publications). We searched the WoS Core Collection for records authored by a ‘Savory, A’; of the 88, 62 were ‘Allan Savory’. Cited reference searching, also called ‘known item’ searching, is a search function that is especially strong in WOS. A cited reference search of the 62 Savory publications produced a dataset of 337 records published between 1980 and 2015 that referenced at least one of Savory's HM publications (see full list at Kent and Sherren, Reference Kent and Sherren2015). We checked to confirm that each of these was discussing HM, albeit to varying degrees.

Any WOS-based dataset is necessarily incomplete. Like most databases, WOS has weak tracking of book citation, which is the form in which Savory has published most often on HM. It does not capture reports and other uses, as does Google Scholar. WOS also does not index all journals nor does it include all issues of the journals it does index. WOS has a bias toward North American, English-language, high impact factor, journal-based scholarship and has significantly improved coverage of serial publications after 1996 (Moya-Anegón et al., Reference Moya-Anegón, Chinchilla-Rodríguez, Vargas-Quesada, Corera-Álvarez, Muñoz-Fernández, González-Molina and Herrero-Solana2007; Jacsó, Reference Jacsó2009; HLWIKI International, 2015). Of the 148 unique publication sources in the dataset, 18 were not serials (e.g., were book chapters or conference proceedings) and one was ineligible because of discrepancies. For the remaining 126 (121 given that five simply changed names), the total publication timeline of the serial according to UlrichsWeb Global Serials Directory was compared with WOS coverage. Gaps were present in 51% of journals and fully a quarter of the incomplete serials were missing over half of their publication timeline. As many journals with incomplete coverage were from smaller, regional publications, excluding those journals from this study would exacerbate the geographic bias in the database so all were kept. For a full analysis of WOS coverage and bias, see Appendix B of Kent and Sherren (Reference Kent and Sherren2015). In general, the biases in the Savory-citing dataset are typical of scientometric research such as ours, and hence are unavoidable. In all cases of research with large secondary datasets, the data can be ‘noisy’ but broad patterns still discernable and valuable.

Few scholars would consider 337 citations over such a period a strong indication of career impact, though as outlined above, many things are missing. This number represents about a quarter of Savory's citations as captured in Google Scholar, for instance, which tracks books and reports as well as less formal work such as extension materials. The disparity between WOS and Google Scholar results actually speaks to the penetration of Savory's ideas beyond the academy and thus the importance of understanding scholarly division on the topic of HM. We decided to use WOS in part because of its limits—it was the most systematic way to capture the peer-reviewed scholarship citing Savory. While the WOS citations suggest that Savory has been ignored by science, alternative interpretations exist, which we tackle in the discussion.

Nonetheless, Savory has certainly not been ignored by society, and that makes understanding his impact even more critical. HM is still a fringe activity on-farm, estimated at <10% of farmers in some places, though that still makes a substantial number of practitioners (Sherren et al., Reference Sherren, Fischer and Fazey2012; Roche et al., Reference Roche, Cutts, Derner, Lubell and Tate2015). His paradigm shift has been influential beyond the farm scale, too, informing debates over public land management (Chiaviello, Reference Chiaviello, Coppola and Karis2000), regenerative agriculture (e.g. Soils for Life, http://www.soilsforlife.org.au) and climate change mitigation through soil carbon storage (Teague et al., Reference Teague, Apfelbaum, Lal, Kreuter, Rowntree, Davies, Conser, Rasmussen, Hatfield and Wang2016). Savory's (Reference Savory2013) TED talk has had a million views per year, and is by far the most viewed of all TED talks on the topic of Agriculture. Its viewership is likely higher given likely classroom use. That TED talk reinvigorated scientific debates around HM among those studying grazing and introduced Savory to those studying climate change (Briske et al., Reference Briske, Bestelmeyer, Brown, Fuhlendorf and Polley2013; Carien de Villiers et al., Reference Carien De Villiers, Esler and Knight2014; Carter et al., Reference Carter, Jones, Brien, Ratner and Wuerthner2014; Monbiot, Reference Monbiot2014; Garbach et al., Reference Garbach, Milder, DeClerck, Montenegro De Wit, Driscoll and Gemmill-Herren2017; Nordborg and Röös, Reference Nordborg and Röös2016; Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Maczko, Hidinger and Ellis2016). Savory's potential impact on policy is clearly disproportionate with his scholarly citation rate.

We examined the impact that Savory has had on scholarship as captured in WOS and how scholars in turn have opined on HM, by performing a detailed scientometric analysis of the Savory-citing records. We first analyzed the records for temporal and geographic patterns. Geographic locations were based on a scheme put forth by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (Population Division, 2002). Each record was assigned author regions (based on the listed addresses of reprint authors), publisher regions and where evident from abstracts and titles, the region of study. We developed a custom classification scheme to reveal patterns in the subject matter of each publication. Rather than assigning a single subject term to a record, which is subject to all the challenges of classification such as oversimplification, we allowed for two (or the same subject assigned twice) (Supplementary Table 1). While WOS includes its own subject terms as well as research areas, these are not applied consistently enough to be useful.

While Allan Savory's work revolves primarily around grazing and land management, the HM practice is based on a holistic model of managing land, people and resources that has appeal to authors in diverse fields, given the emphasis on adaptive principles. That is, Savory has a meaning for researchers outside of the grazing realm and this is largely as a working example of an adaptive management practice (e.g. Hodbod et al., Reference Hodbod, Barreteau, Allen and Magda2016). Though most such papers were positive about HM, these were not included in our analysis of position because they did not present any data to support that assessment. Only 137 of the records citing Savory's work examine HM as a system or specific aspects of the practice using data analysis. We deductively gauged overall ‘position’ on HM for each of these records (positive, neutral/mixed, or negative) by reviewing the text. This is a qualitative process, and as might be expected, assigning a single ‘position’ for each paper was not clear cut (Ryan and Bernard, Reference Ryan and Bernard2003). In some cases authors equivocated based on their results, for instance where some variables supported improvements from HM and others did not (or indicated declines). We classified these as neutral/mixed. Because of the relatively small sample we did not split it further by separating out analyses of various aspects of HM, or scale of study (i.e., farm or field), though we did capture the study location.

We did not differentiate between the evidence on which any expressed position was based, for instance whether it was using quantitative or qualitative methods. Instead we relied upon peer review in the journals where they appeared to ensure rigor appropriate to the field. It was not our aim to perpetuate the tendency to critique findings based on poor understanding of other disciplinary norms and methodological standards. For instance, all research using humans must be done with their consent and thus farm-scale work around HM, is subject to self-selection bias (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, Mackenzie and Podsakoff2011), but this does not mean that only farmers who see themselves as successful will volunteer. We assumed that all researchers will make an effort to capture a sample that covers the extant range of relevant experience to their questions and if that is not achievable, will interpret their results accordingly.

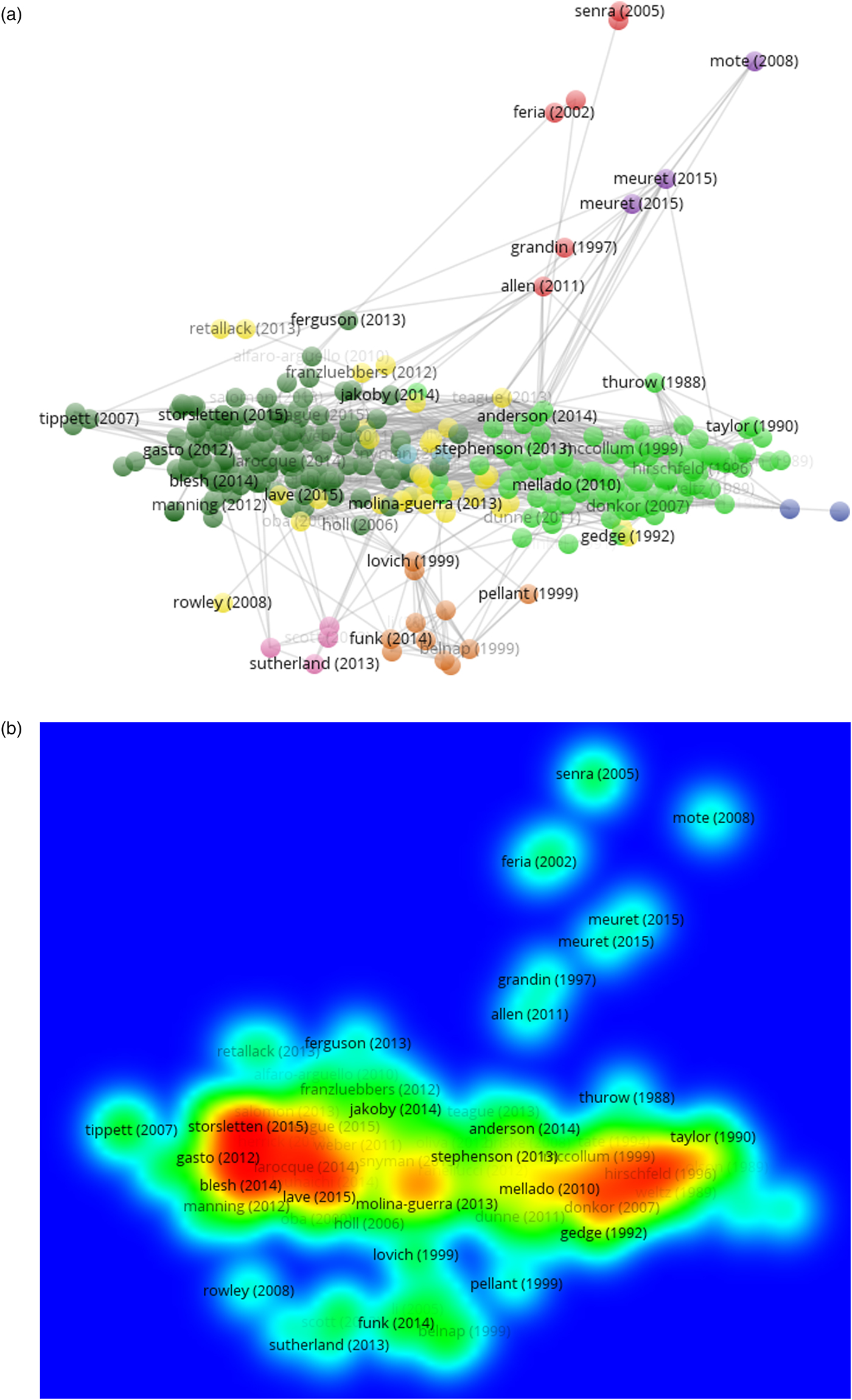

Finally, we visualized bibliometric clusters in our dataset using network analysis to reveal research tendencies based on citation lists. The software VOSviewer 1.6.1 (van Eck and Waltman, Reference van Eck and Waltman2010) was used to visualize networks of our records based on bibliometric coupling, which creates links between records when they share references. Networks inherently rely on linkages between their component parts: of the 337 eligible records in our dataset, five were omitted as they shared no links with any of the others. Records are identified as ‘nodes’ in the visualizations, listed by the lead author only, followed by some bibliometric data (i.e., the record's date of publication). We can interpret how strongly nodes are tied to one another (i.e., the degree of similarity of their cited references) by their proximity due to the stress majorization function used to draw them, visualization of similarity (VOS) (van Eck and Waltman, Reference van Eck and Waltman2009). As the bibliographies of every pair of papers is compared relationships could be represented in a two-dimensional (2D) matrix, with as many rows and columns as there are papers, and cells holding a measure of bibliometric similarity for each pair. This would be impossible to interpret visually, however, so we typically seek to represent them in a graph. VOS is a calculation that allows for elements and their relationships to be represented in a 2D space, when the many links between those elements are under tension across many dimensions and do not naturally allow it to be ‘flat’ (for details see van Eck and Waltman, Reference van Eck, Waltman, Decker and Lenz2007). VOSviewer's software then uses algorithms (van Eck and Waltman, Reference van Eck, Waltman, Decker and Lenz2007) to automatically cluster nodes. These clusters are useful in understanding the structure of the academic literature. We compared these clusters with subject areas and position on HM to explore polarization.

Results

Patterns over time, space and subject

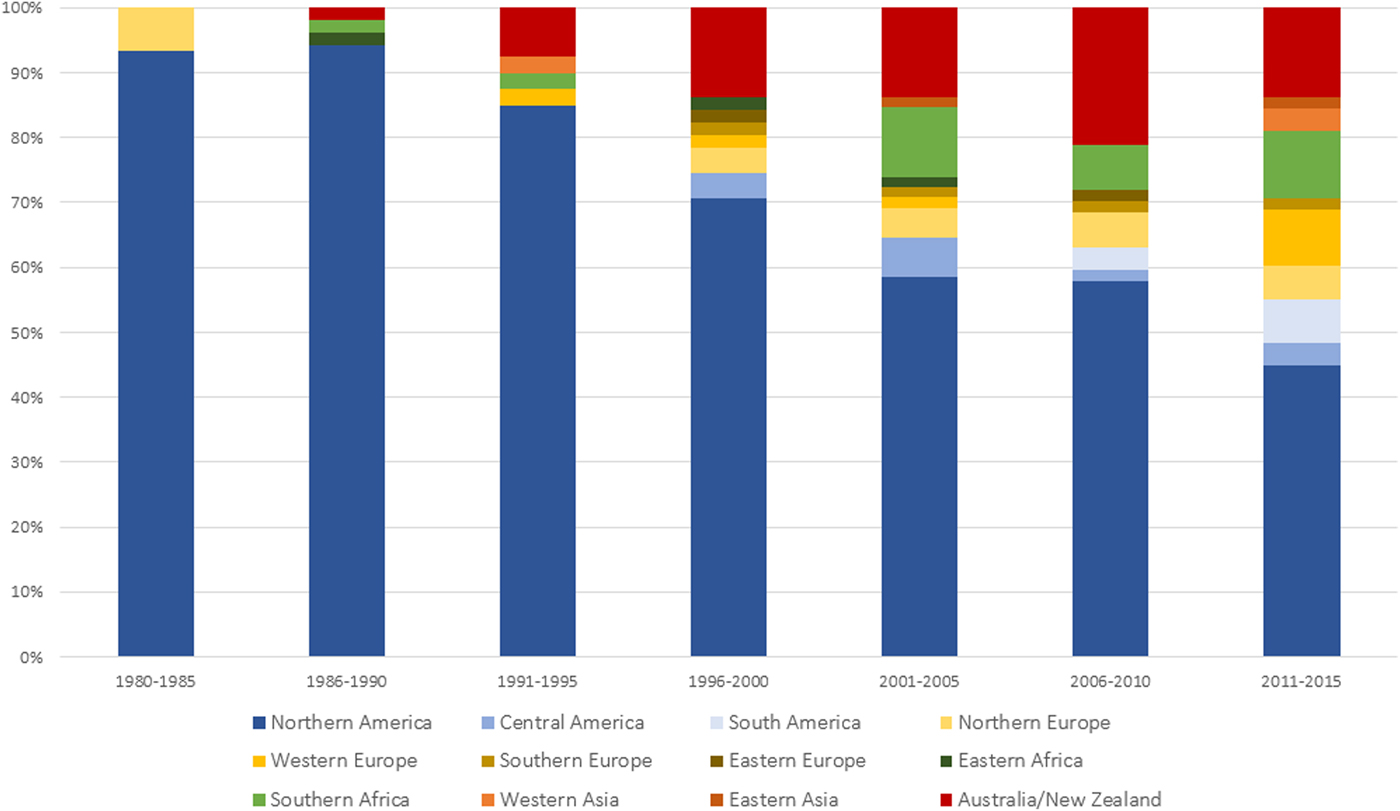

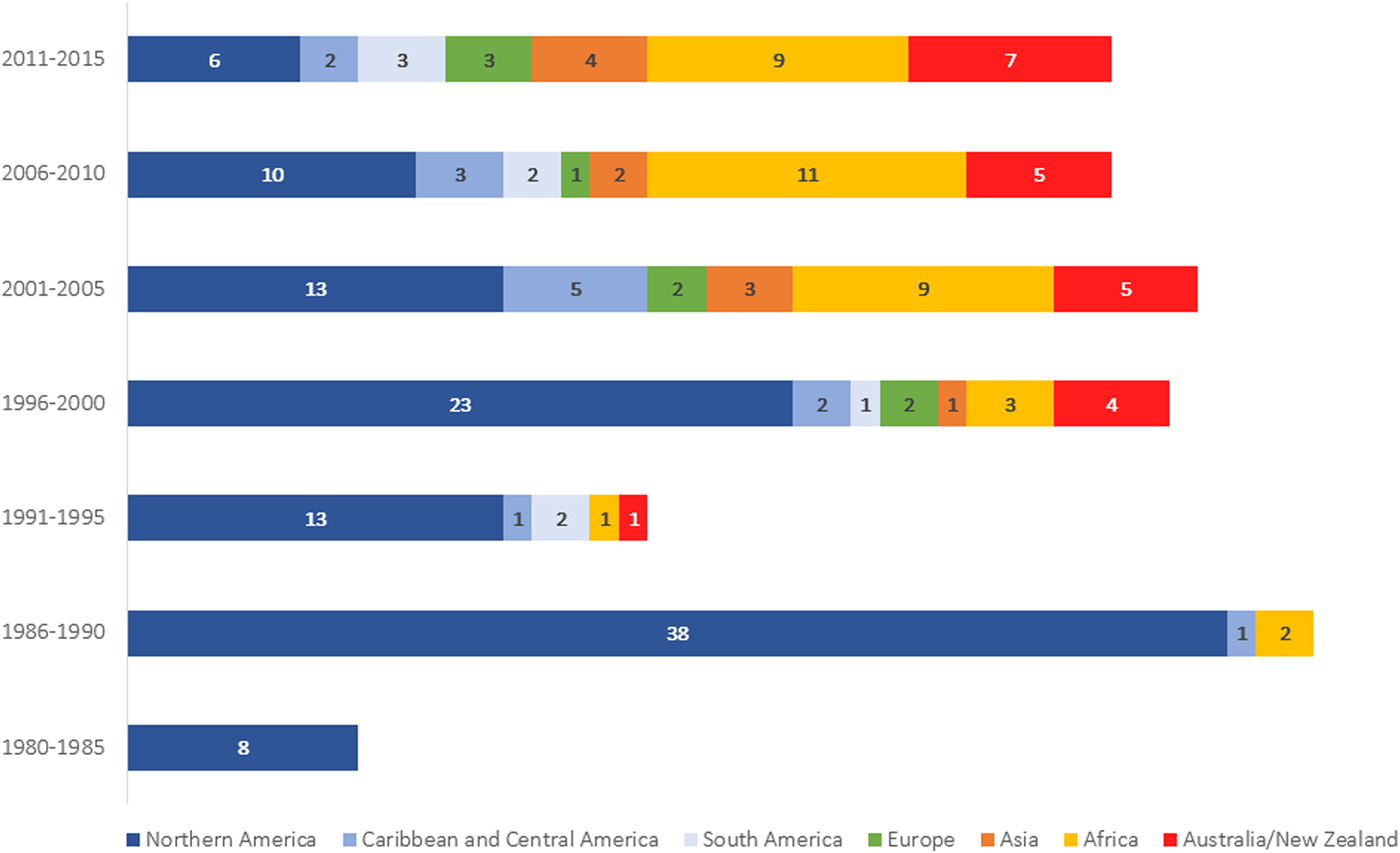

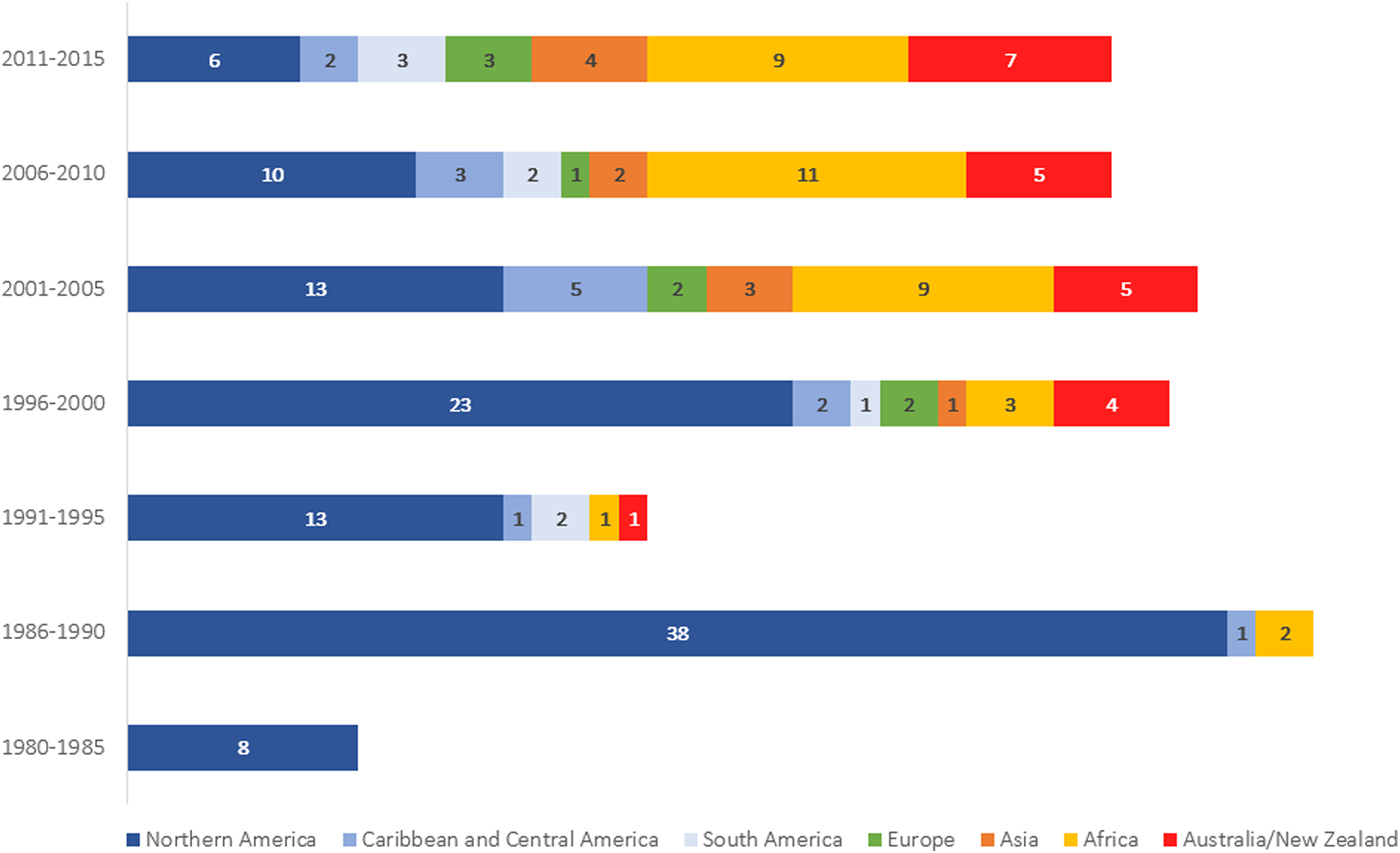

The geographical influence of Savory's work on scholarship is at times difficult to disentangle from the geographical biases on WOS. Two-thirds of corresponding author addresses are North American, where Savory has lived and operated his Institute for the majority of his career. A further 12% are from Australia or New Zealand, and 6% from Southern Africa, near his birthplace of erstwhile Rhodesia, where he developed the ideas that led to the development of HM. The dominance of North America has decreased over time, however (Fig. 1), particularly since 1996 when journal coverage in WOS improved. While the majority of scholars (81%) seem to work in their own region—particularly those in Oceania—there are also common research ‘imports’: Europeans worked in Africa (7 sources), and North Americans in Africa (9), Central & South America (8) and Asia (4) (Kent and Sherren, Reference Kent and Sherren2015). The dominance of North America as a study site for Savory-citers (including those working in their own continent) has continually decreased since 1996, with increasing work taking place in Australia and Africa (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Percent representation of authors’ regions over time. The Americas are in shades of blue, Europe is in yellow, Africa is in green, Asia is in orange and Oceania is in red.

Figure 2. Study site continents by year of publication (including those studies that took place in the first author's home region).

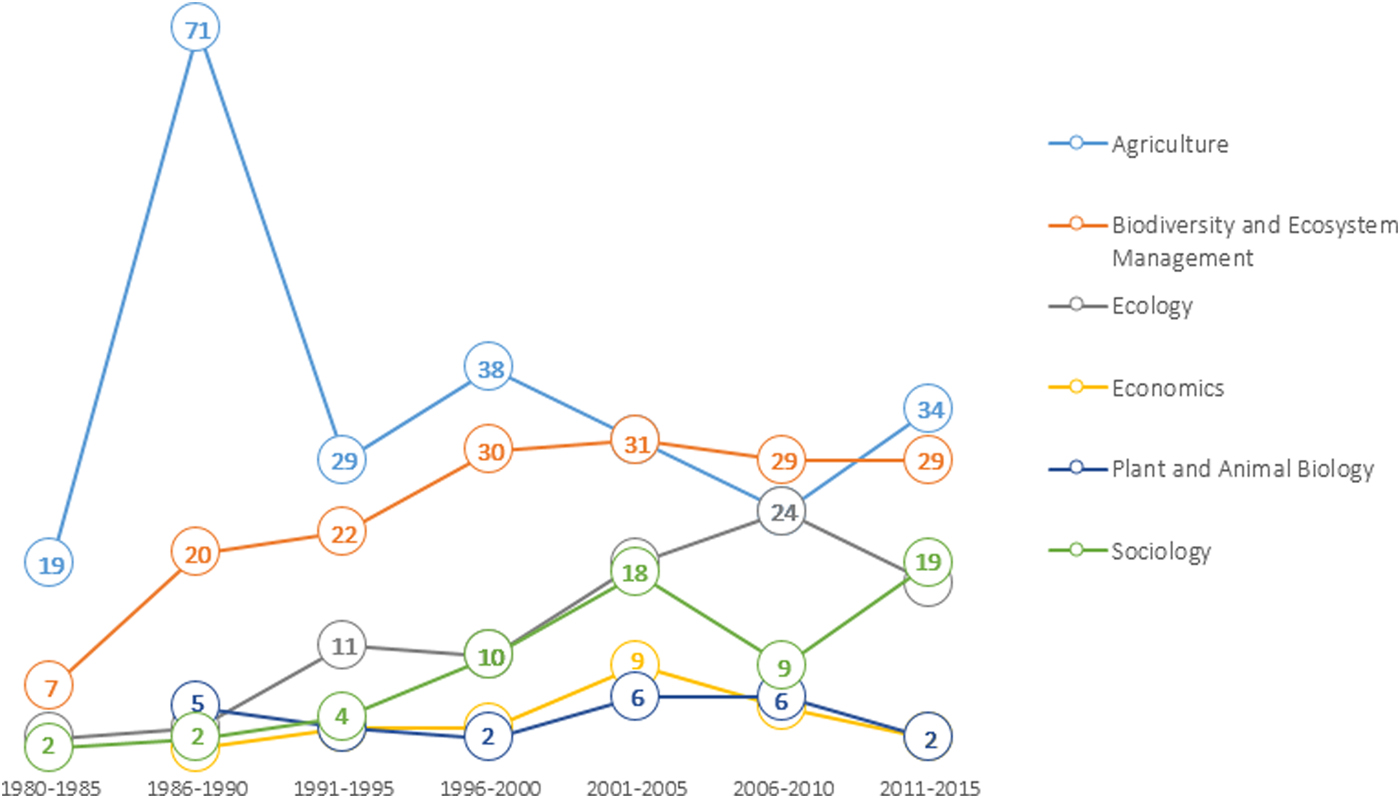

Savory's work clearly applies primarily to those working in Agriculture (37%), but is used in various fields of scholarship including Biodiversity and Ecosystem Management (25%), Ecology (13%) and Sociology (9%). Authors referring to Savory's work generally tackle the following themes: (1) agricultural management contextualized by environmental impacts on biodiversity and ecosystems, (2) range and land management for ecological health, (3) agricultural management to ensure efficient and economical food production, including animal welfare and (4) human uptake of new management strategies, including epistemology and formalized education. Agriculturally-themed publications dominated the literature until the mid-1990s, when more environmental and sociological perspectives began gaining ground (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Trajectory by paper count for subjects occurring at least 20 times across the dataset.

Expressed position on HM

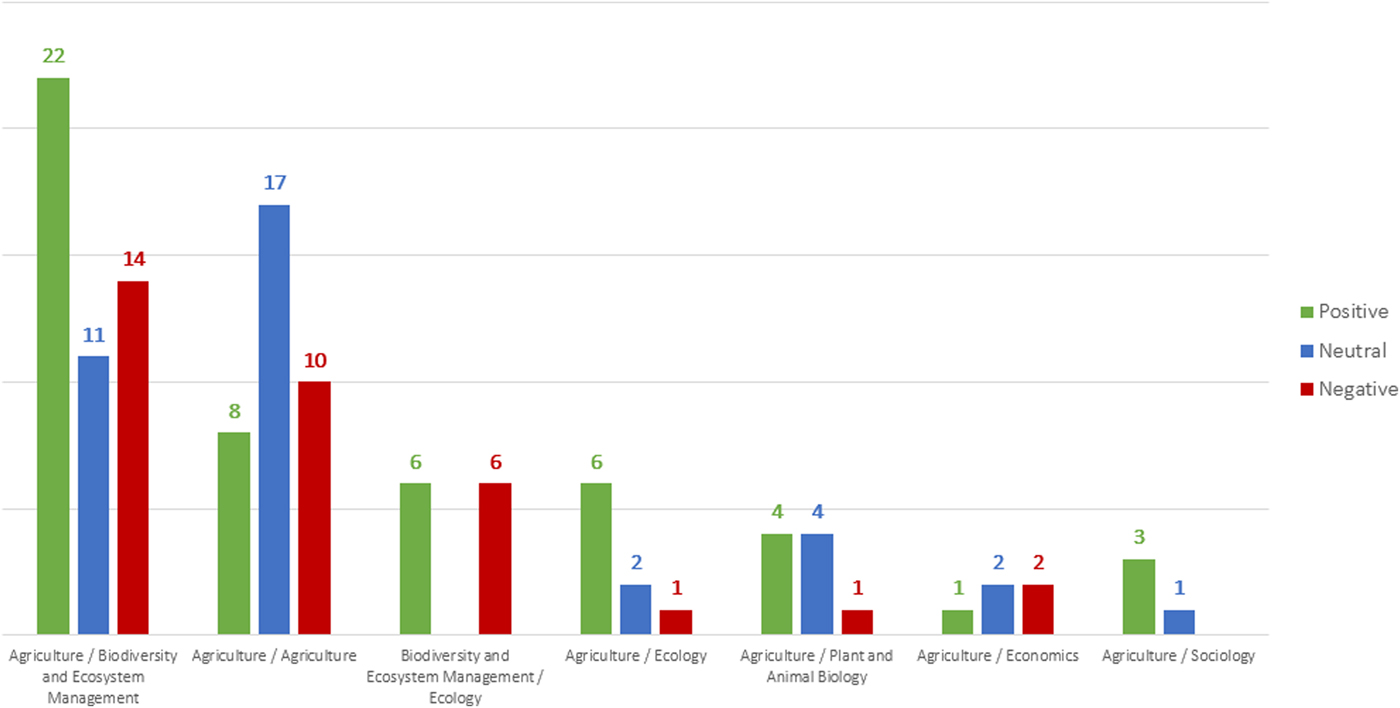

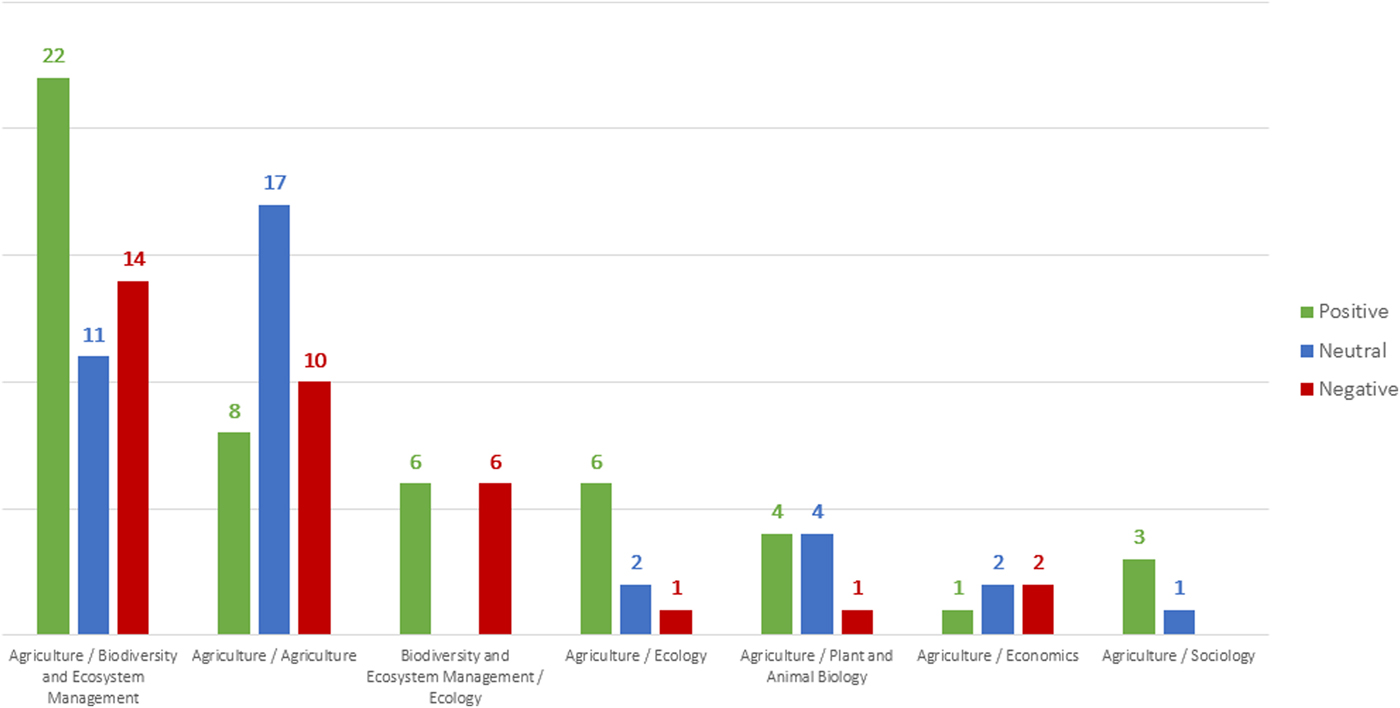

Sentiments (‘positive’, ‘negative’ and ‘neutral/mixed’) toward HM were recorded for all 137 records that mentioned examining HM or any aspect of Savory's model using data (e.g. high speed of rotation, smaller paddock size and/or high stocking rates) in their title or abstract. The records assigned to each category (positive, neutral/mixed or negative) existed along a spectrum of each value. For instance, some of the 45% ‘positive’ records were effusively positive, while others tentatively endorsed the aspect presented. Neutral/mixed records (30% of records) were characterized by inconclusive results or presentation of equally negative and positive implications of the aspect(s) examined. Three periods were evident in the results (Table 1). Prior to 1990, the three positions were quite evenly distributed, with neutral/mixed records highest at 40%. From 1991 to 2000 fewer papers were produced (30) and positive assessments started to nudge ahead at 47%. Since 2001, positive assessments (at 63%) have dominated the literature as captured in WOS. Half of the neutral/mixed and negative records were published in the first period, before 1990 and half of the positive ones in the last period, since 2000. The surge in positive articles echoes the parallel increase in Biodiversity and Ecosystem Management, Ecology and Sociology records (Fig. 3). Additional examination of the top subject pairs in the dataset by position on HM, tell a similar story (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Position on HM by top subject pairs.

Table 1. Counts of papers displaying a position on HM across all records discussing specific elements of HM, using data, rather than using it as a general example of adaptive management, over three time periods.

Geography clearly also plays a role in assessments, because HM is likely more suitable for some ecosystems than others. In particular, Savory has described a particular suitability of HM for what he calls ‘brittle’ ecosystems (Savory, Reference Savory1983): those with prolonged dry periods that challenge plant growth and where low soil biota makes for slow nutrient cycling. This analysis is difficult because of the dominance of North American-authored papers in the WOS dataset and the risk of bias by individual scholars in places with fewer records. North American studies comprised three-quarters of the sample and were quite split on HM. Of the remaining quarter, Central and South American studies represented half and were also evenly split in opinion. Most of the remainder of the studies were in Oceania or Southern Africa, three-quarters of which resulted in positive assessments (Kent and Sherren, Reference Kent and Sherren2015), which might suggest the context climate has an impact.

Similarity of citation lists

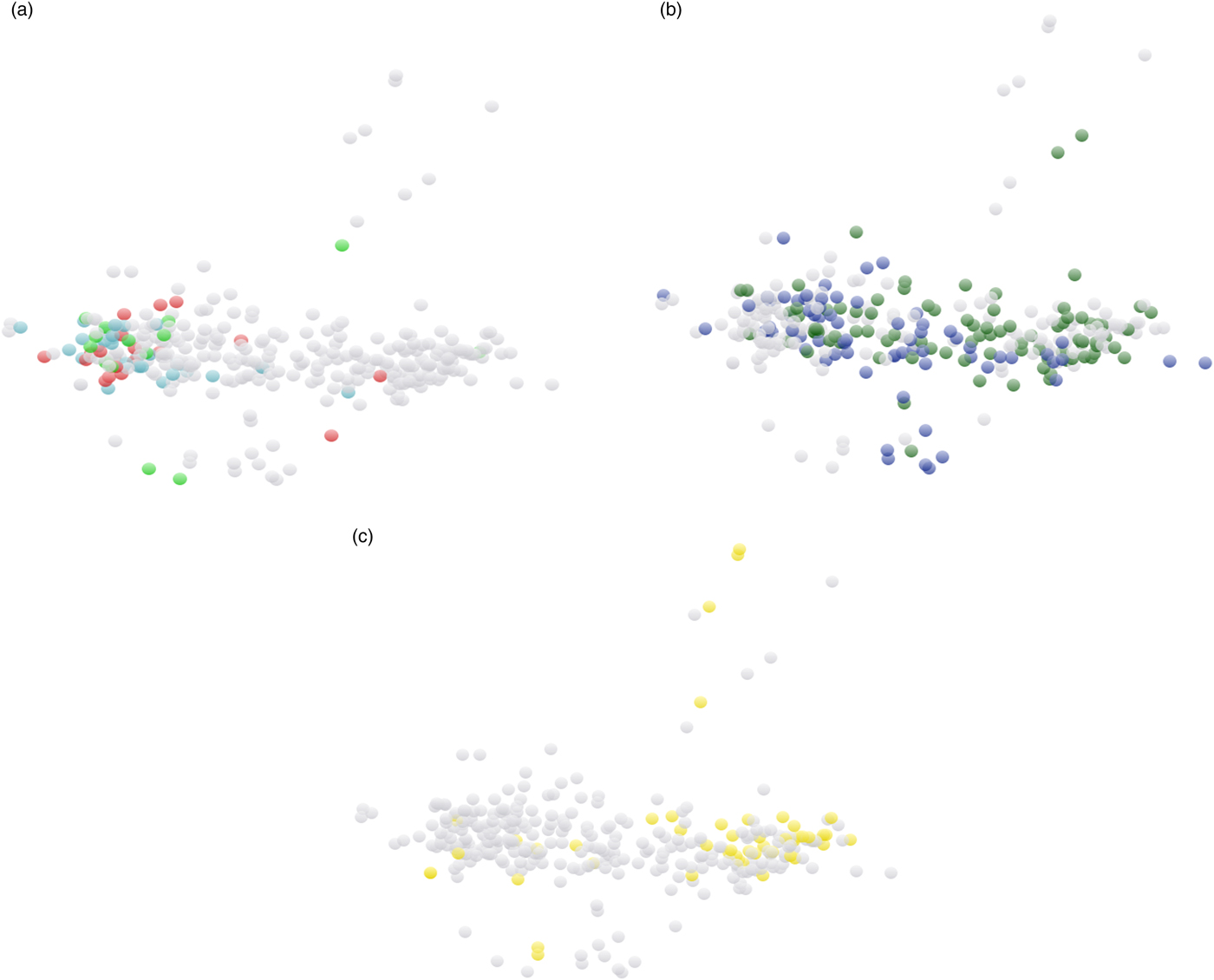

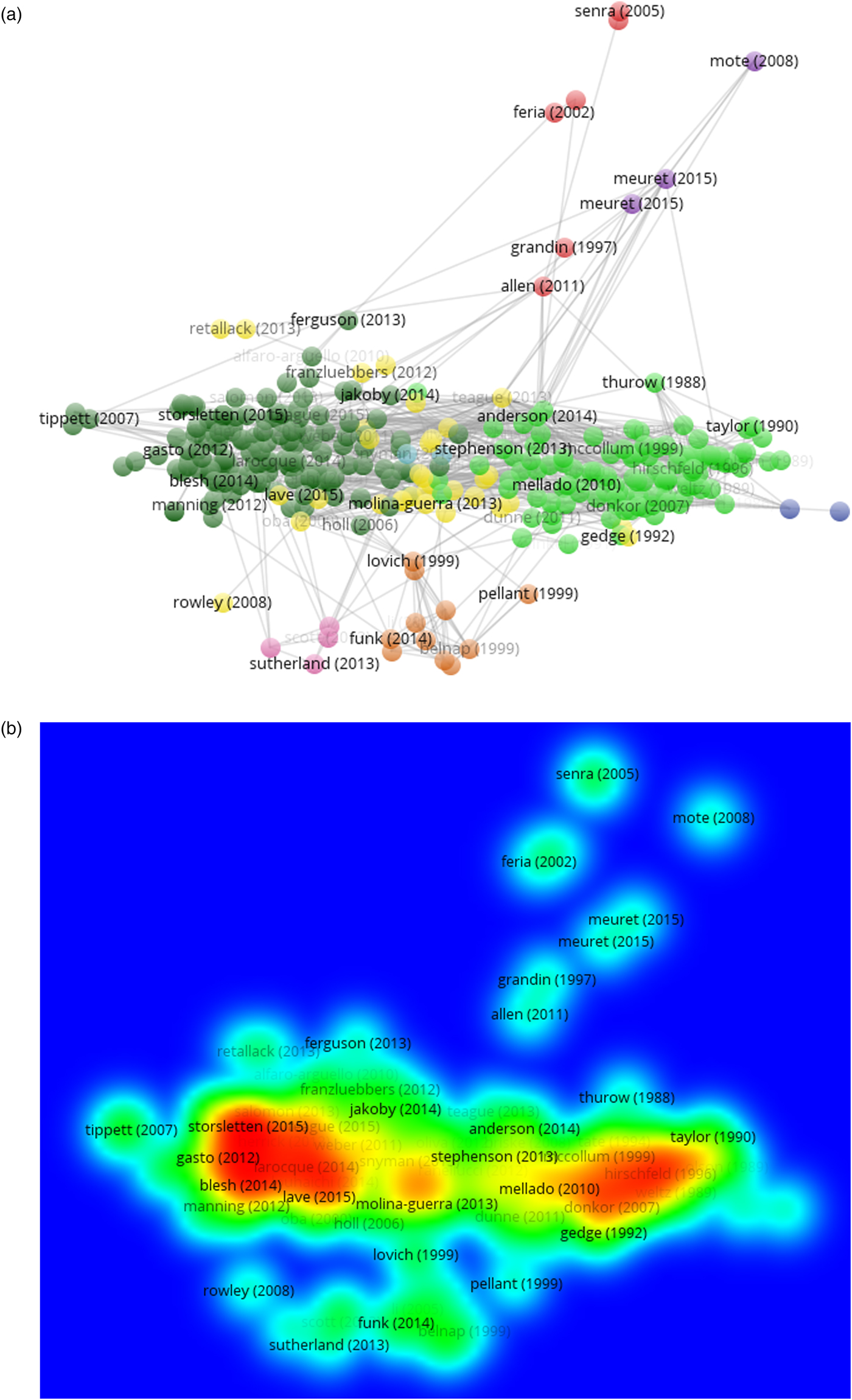

Most fruitful for understanding polarization in the HM scholarly discourse as captured by WOS was bibliometric clustering, which arranges records (visualized as nodes) based on the similarity of their bibliographies (Fig. 5), placing those with a high degree of similarity close together. The automatically-generated bibliometric clusters (Fig. 5a, light and dark green) show, for instance, that there are two dominant clusters, or factions (sensu Shwed and Bearman, Reference Shwed and Bearman2010), in the literature in terms of the bodies of work recruited to support papers (Fig. 5b, red areas). Based on our subject area classifications, as applied to where the records appear as nodes in that same ‘space’, these distinct literature hotspots are associated with social sciences/management (left) and experimental agriculture (right). Social sciences and management nodes include bibliographic references dealing principally with human issues and human decision-making (Fig. 6a). Note that we did not differentiate in this analysis between qualitative (interpretivist) and quantitative (more positivist) social sciences methods. Conversely, experimental agricultural science nodes were located mainly around the right hotspot (Fig. 6c), affirming a general polarization between social and physical sciences, notwithstanding the scattering of environmentally-themed nodes across the bibliometric network (Fig. 6b).

Figure 5. Network (a) and density (b) visualizations of HM dataset using bibliometric coupling. Network colors in (a) differentiate clusters determined by VOSviewer based on citation list similarities. Density colors in (b) indicate peaks (red) where many sources have similar citation lists. Nodes with proportionally more connections are displayed with primary author's last name and year of publication.

Figure 6. Nodes showing subjects by three dominant subject area clusters: (a) social sciences (red = management, light blue = social science, light green = social science perspectives on agriculture); (b) environment (dark green = environmentally inclined agriculture, dark blue = environment); and (c) experimental agriculture (yellow). Proximity in node placement is based on similarities in bibliographies.

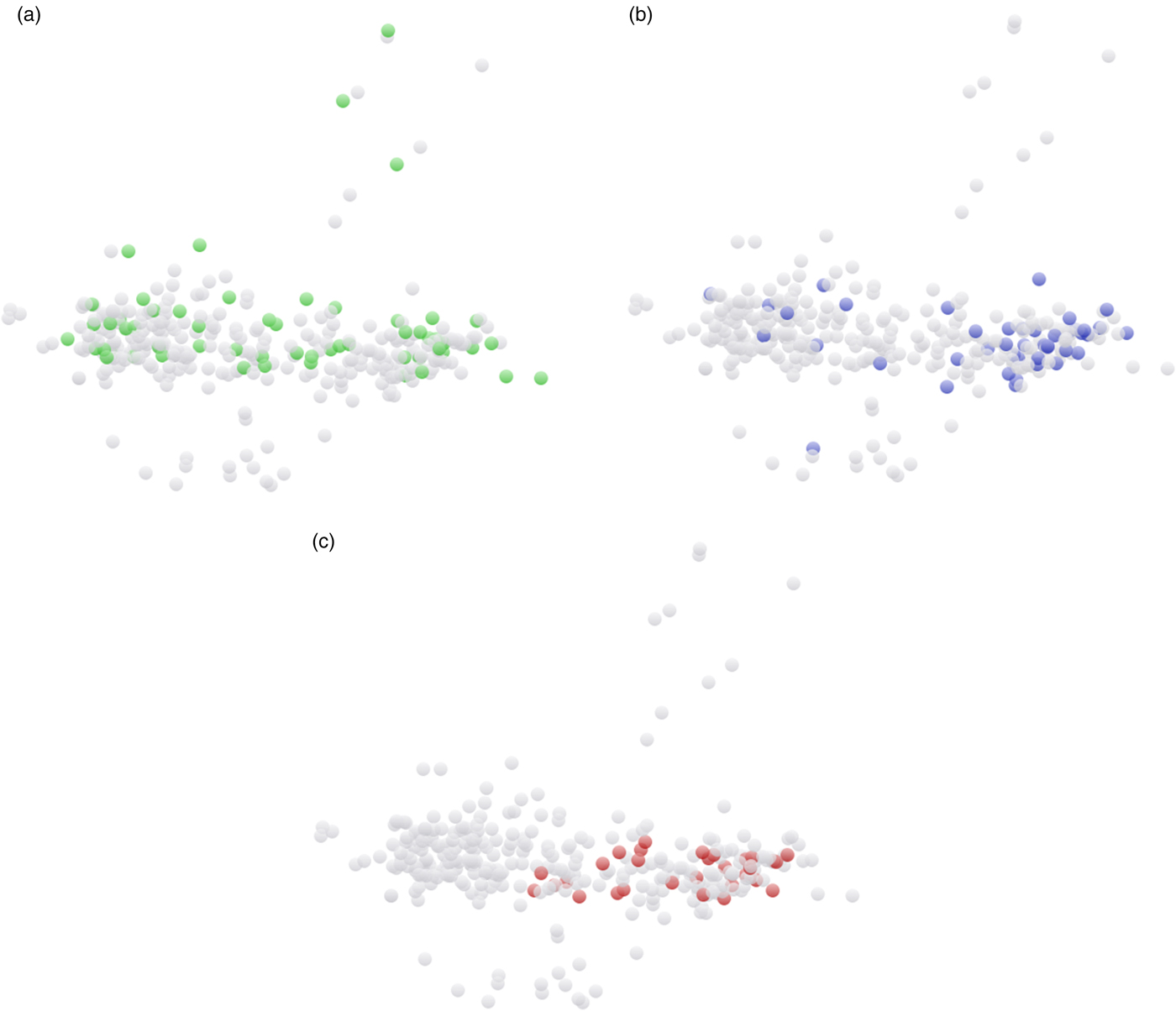

Critically for understanding polarization, the hotspots reveal that papers cluster not only by fields of study but also the position on HM they convey (Fig. 7). Papers negative or neutral/mixed about HM seem to be located at the right hotspot, with more experimental work (Fig. 5b), whereas papers positive about HM are found across the network. A quick look would suggest that the experimental agriculture subject area dominates that negative cluster (Fig. 6c), but in fact this is not the case (Fig. 4). Social sciences and management records were overwhelmingly positive about HM (Table 2; see also Fig. 4), while environment records were somewhat polarized between positive and negative: Experimental agriculture records were in fact predominantly neutral/mixed (Table 2).

Figure 7. Visualization of dataset network using bibliometric coupling and manually colored nodes based on records’ attitudes toward HM, broken out by attitude for improved visibility: (a) positive (green); (b) neutral or mixed (blue); and (c) negative (red).

Table 2. Proportions of each dominant cluster (Fig. 5) by associated attitudes toward holistic management, where available, shown as percentages.

Discussion

We set out to understand the structure of science on HM, captured via WOS citations to the HM work of Allan Savory and specifically to systematically explore the rift around HM that is quickly evident to readers of that literature. While some emergent patterns may be spurious, others suggest productive veins for further research and policy development, particularly integrated work in specific contexts.

What can we say about HM science?

Patterns can be discerned of an increasingly diverse English-language scholarship in terms of subject and geography, as well as one that is increasingly positive in its assessment of HM. Caution must be used, however, when interpreting the upward trajectory of positive assessments. This does not simply mean that early criticism has been overcome by positive consensus. Some such patterns may be artifacts of the dataset itself. It may be, for instance, that those working in different fields are citing different works of Savory: if one was increasingly citing his later books and the other his papers, a similar pattern could emerge. It may also be that different positions emerge from examining different incarnations of HM over time (Box 1). Further research is needed that captures a wider range of HM (and related) scholarship.

Some trends evident in this analysis are revealing, however, in ways useful for grazing policy. What was once a topic of agricultural research in North America is increasingly being studied in other so-called ‘brittle’ landscapes (dry, with low soil biota, where HM is described by Savory as most useful) like Australia, Mexico and Southern Africa, with the involvement of ecology and sociology. That such places and ecosystems still represent a small share of work on HM as defined here may be part of a broader geographic and climate imbalance in environmental research (Karlsson et al., Reference Karlsson, Srebotnjak and Gonzales2007). Further work should endeavor to include a wider range of journals than those indexed in WOS, particularly smaller, regional journals that would allow such observations to be more fully explored (e.g. Fynn, Reference Fynn2008).

The shift in subject area evident among Savory-citers may also drive the increasingly positive assessments of HM, particularly as those who talk to farmers—social scientists—seem overwhelmingly to hear positive reports of its impacts. Disciplinary patterns are likely entangled with the scale at which such work is done. For instance, compared with experimental science, whether agriculture or biology, ecologists typically study a system in situ rather than mimicking it in a controlled setting. This is akin to the difference between psychologists, for instance, and sociologists. It may be inferred here, though not proven, that it is farm-scale work that tends to produce positive assessments.

What also seems likely, based on low citations overall and decreasing amounts from some disciplines, is that many experimental agricultural scientists have ceased citing Savory (or at least citing his journal papers). While Savory planted intriguing hypotheses in the 1980s about increasing stocking rate without environmental cost, which scientists wanted to examine, his method is no longer an active vein of research for them. The process of scientific consensus on HM may have played out fully within experimental science to the extent that the outcome (e.g., HM does not ‘work’, or perhaps HM is untestable) has become a black box, easily stated without the need for explanation or citation (Shwed and Bearman, Reference Shwed and Bearman2010). The next generation of agricultural scientists thus may take it as truth. The problem is that such a consensus—if it exists—is likely based on incomplete understanding of the grazing system: it leaves out the farmer (Sherren and Darnhofer, Reference Sherren and Darnhoferin review).

Bibliometric coupling revealed that there are two distinct bodies of evidence being used to support papers on HM—that is, very different citation lists—and that those two factions align with social sciences/management and experimental sciences. This indicates that the authors of papers in one faction are not citing, perhaps not even reading, the papers used by those in the other faction. Such factions tend to reproduce themselves through conventional literature review practices like ‘chaining’ (finding citations from other papers) and keyword searches using discipline-specific or value-laden jargon, which only exacerbates polarization (Supplemental Box 1). This is not so different in process, though it may be in impact, from the increased consumption by citizens of news and other media personalized based on past browsing behavior (Koutrika, Reference Koutrika, Colace, De Santo, Moscato, Picariello, Schreiber and Tanca2015): polarization is often exacerbated by the aggregate impact of editorial, peer and automated ‘gatekeeping’ decisions (Shoemaker and Vos, Reference Shoemaker and Vos2009).

Our dataset includes many examples where HM is used as a successful example of adaptive management (AM) by those who are not setting out to test it with primary data. This is appropriate as the only clear consensus that is emerging in the HM literature to date is about the value of its adaptive framework (Nordborg and Röös, Reference Nordborg and Röös2016). AM is a structured iterative practice of decision-making and monitoring for management towards specific goals that was introduced by Holling (Reference Holling1978), yet is rarely found fully implemented. Savory works primarily in range management, but was trained in former Rhodesia as a game range manager and biologist, and has political and consulting experience (Waghorn, Reference Waghorn2012). He is a strong advocate of sustainable practices that protect ecosystem services and his management approach emphasizes systems thinking. These generic principles see his work picked up by many fields interested in how AM can be applied and these records draw entirely upon other papers or reports for evidence (e.g. Hodbod et al., Reference Hodbod, Barreteau, Allen and Magda2016). Whether such ‘synthesis’ scholars discuss HM positively or negatively within that context may well depend on which paper and thus faction they find first—that paper could be a thread that may lead them to a predominantly positive or negative set of evidence.

Possibly the most interesting aspect of this research is the evidence that polarization on HM was not between social science and experimental agriculture. In fact, experimental agriculture tended towards equivocation: a neutral or mixed position in the presence of uncertainty, likely derived in part from an awareness that the scale of their analysis does not fit that of the system under debate (Roche et al., Reference Roche, Cutts, Derner, Lubell and Tate2015). Social science was predominantly positive about HM after conversations with, or surveys from, people on the ground. Social scientists were perhaps more inclined to advocacy on the basis of farmer perspectives, taking farmers as experts in their systems and whether their goals are being met. This may be caused by the fact that working with farmers gives a whole-farm perspective: as Teague et al. (Reference Teague, Provenza, Norton, Steffens, Barnes, Kothmann, Roath and Schroder2008) explain, there is a difference between science and management (see also Mills and Clark, Reference Mills and Clark2001). Experimental scientists are only generally looking at one piece of the puzzle, to control variability, and few scholars can span all elements. Therefore, not only does it take many experimental studies to build evidence of the larger system, if that is even possible to do, but no particular scholar is responsible for it all, making advocacy less likely (Steel et al., Reference Steel, List, Lach and Shindler2004; Nelson and Vucetich, Reference Nelson and Vucetich2009).

It was in fact environmentally-inclined agriculture and environment as a field of study that was internally divided on the matter of HM, based on our analysis. It would be interesting to know whether that division (or the two peaks more generally representing each faction) followed methodological lines: do qualitative/interpretivist traditions tend toward positive assessments and quantitative/positivist traditions tend toward negative? Both traditions are common within the social sciences as well. This is a productive avenue for further research in this and other intractably bifurcated fields. Additional insight would be gained also from a full meta-analysis examining results by study area climate regimes and scale of analysis, as well as methodology. As already mentioned, casting a wider net may also be appropriate—including to capture non-peer reviewed sources such as reports—to gain a clearer sense of Savory's impact and wider perceptions of HM.

The entanglement of person, practice and method is undoubtedly part of the problem. Savory developed the HM system, but there have been significant parallel developments around similar approaches, with overlapping practices, that avoid the term because of its ‘baggage’, as well as intellectual property. He is a polarizing figure, in part because of the paradigmatic shift his ideas represent for rangeland thinking (Chiaviello, Reference Chiaviello, Coppola and Karis2000; Hadley, Reference Hadley2000). Savory clearly sees HM as his legacy and understandably seeks thus to advance it as well as protect it. Savory planted the tantalizingly testable hypothesis that drove early experimental work (and controversy) by suggesting HM allows for doubling or tripling stocking rates without tradeoffs. The new testable hypothesis seems to have been inspired by the now-notorious TED talk (Savory, Reference Savory2013), suggesting HM ‘can green deserts and reverse climate change’ (Nordborg and Röös, Reference Nordborg and Röös2016). Both hypotheses are likely distractions from understanding what benefits HM may bring at the farm scale, or why farmers may choose to adopt it.

What are the implications for grazing research and policy?

Fundamentally, the structure of science about HM as described above is suggestive that silos dominate an applied field—grazing—that should be interdisciplinary. Some of the drivers of these silos have roots in the way scholars work and are thus persistent in part because they also have benefits. Limitations of human cognition, inherent and as trained by disciplines (e.g. language and esteem) (Gieryn, Reference Gieryn1983; Palmer and Cragin, Reference Palmer and Cragin2008), allow focused work and academic progress but can introduce biases that reinforce boundaries. In fact, disciplinary lenses often come with normative ones (Sarewitz, Reference Sarewitz2004). Scholars are also not immune from logical fallacies (Lord et al., Reference Lord, Ross and Lepper1979; Golman et al., Reference Golman, Loewenstein, Moene and Zarri2016) or the effects of cognitive dissonance (as used to explain away positive farmer assessments of HM by Briske et al., Reference Briske, Ash, Derner and Huntsinger2014). Bias—disciplinary, normative, cognitive, systemic (e.g. funding, publication)—is both introduced and reproduced in research. All methods have their strengths and weaknesses, for instance the vulnerability of qualitative methods to ‘chapter and verse’ language by HM practitioners (Sherren et al., Reference Sherren, Fischer and Fazey2012). Awareness of the incompleteness of any one picture should help to mitigate polarization and smooth the way for integrative, socio-ecological research to address complex problems (Hinrichs, Reference Hinrichs2008; Pohl, Reference Pohl2008).

Practitioners of HM and other advocates should take care in their use of rhetoric, which may fuel polarization. Rhetoric is simply language designed to persuade and it is used in academic and non-academic settings. Transparency is the cure, but is not always evident. For instance, as mentioned earlier, the Savory Institute curates a research portfolio that only includes pro-HM results (Nordborg and Röös, Reference Nordborg and Röös2016) and as a result some scholars see HM advocates as rejecting science per se. A preliminary rhetorical analysis of HM based on online discourse by Holistic Management International, for instance, revealed a tendency to persuade through emphasizing the reputation and expertise of authors, rather than through logic (e.g. sharing data) (Kent and Sherren, Reference Kent and Sherren2016). A lack of transparency in such a context is just as troubling as it is in scientific circles (Cheney, Reference Cheney1983). There is evidence of smaller scale farmer-to-farmer networks (Carien de Villiers et al., Reference Carien De Villiers, Esler and Knight2014; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Brummel, Jordan and Manson2014), in person and online, where challenges and successes on such fringe practices may be shared and supported, but not with non-members. Scholars may be more likely to engage and partner if the HM community were to share the problem-solving and critical reflection that is happening inside: reveal challenges encountered with HM principles in action; document iterations of experimentation; and demonstrate the community as a place of critical analysis and support.

Scholars can start to bridge silos through reasonably small and mundane ways. Busy academic schedules and rewards for publication may encourage shortcuts in literature review, rather than systematic searches (e.g. Browne et al., Reference Browne, Pitts and Wetherbe2007; Pontis and Blandford, Reference Pontis and Blandford2015). Researchers may seek too narrowly and linearly and stop too soon (Supplemental Box 1), finding what would be considered in algorithmic terms a ‘local maxima’ (i.e., closest, best solution). New optimization algorithms use analogies such as genes, ant colony behavior and the slow annealing of metal as inspirations for search strategies to find global solutions (e.g. Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Rothwell and Ross2004). In social-ecological research, it may also be wise for searchers to take a pseudo-stochastic ‘leap’ out of normal literature review trajectories. Recalling the difficulties alluded to in creating a dataset for examining HM publications, the confusion and fragmentation around vocabulary and approaches is also problematic in advancing research on adaptive grazing practices. It is thus critical for research in such a ‘noisy’ but important applied field to develop common vocabularies (Bracken and Oughton, Reference Bracken and Oughton2006). Such a translation device is important for all players to (1) navigate the literature systematically and (2) know when various authors are talking about the same (or different) things.

For policy-makers, it is important to note that scientific factions around HM, as in other controversial topics, bring rigor to the bigger questions (i.e., how to graze), but that none provides a definitive answer. What we see in such situations is less scientific uncertainty than ‘competing scientific understandings’ (Sarewitz, Reference Sarewitz2004), bringing to mind those blind men examining an elephant, which require more productive ways of resolution for application (Cornell et al., Reference Cornell, Berkhout, Tuinstra, Tàbara, Jäger, Chabay, De Wit, Langlais, Mills, Moll, Otto, Petersen, Pohl and van Kerkhoff2013). Proof will always be elusive (Oreskes, Reference Oreskes2004). Indeed, ‘proving’ is not what science does. For the policy community, the uptake of science will depend on the policy culture, which remains opaque to those outside (Hellström, Reference Hellström2000; Lalor and Hickey, Reference Lalor and Hickey2013). Yet policy-makers should seek to improve their search for evidence, as recommended above for scholars, to ensure that they are capturing the extant diversity of opinion rather than privileging individual experts or fields. Some of the most externally visible elements of the policy process are research funding allocations, where recent work has shown that increased funding is required for agroecological systems (DeLonge et al., Reference Delonge, Miles and Carlisle2016). New funding could target more place-based integration across factions such as those revealed here (Sherren et al., Reference Sherren, Fischer, Clayton, Schirmer and Dovers2010; Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Sherren and Hanspach2014b).

Competing understandings need to be plumbed, and integrated in a real context with real managers, in order to assess the HM method for application in situ. Some excellent examples of such research have been done, for instance, in Chiapas, Mexico (Alfaro-Arguello et al., Reference Alfaro-Arguello, Diemont, Ferguson, Martin, Nahed-Toral, David Álvarez-Solís and Ruíz2010; Ferguson et al., Reference Ferguson, Diemont, Alfaro-Arguello, Martin, Nahed-Toral, Álvarez-Solís and Pinto-Ruíz2013). Interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary work relies on strong disciplines (van Kerkhoff, Reference van Kerkhoff2005). The process of integration may be similar to what has been called ‘public ecology’ (Robertson and Hull, Reference Robertson and Hull2003), but the critical outcome is the bringing together of science with users outside of the protected space of the academy (Cortner, Reference Cortner2000). One set of collaborators should be the farmers themselves, whose expertise is based on years of high-stakes experimentation and observation (Sherren and Darnhofer, Reference Sherren and Darnhoferin review). In doing so, it will be important to discard the desire for consensus, which will tend to narrow teams to those sharing an epistemology (a sense of what constitutes evidence). Despite the risk of discomfort, it will be more productive in the end to expose competing understandings than reach a coherent outcome based on limited perspectives.

Conclusion

The scholarship that cites the work of Allan Savory, as indexed by the Web of Science, was used as a proxy for peer-reviewed HM literature. Though an imperfect representation of Savory's impact, as well as the HM domain, these papers were examined for patterns: topical, temporal, geographical, as well as position on HM and bibliographic similarity. We described an increasingly global footprint, over a widening breadth of disciplines, as well as indications that positive assessments of HM were associated with work at the farm scale and in dry climates. Distinct clusters were evident in that literature, suggesting two dominant and disconnected factions in terms of substantive scholarly influence. This suggests search or assessment techniques are being used that funnel researchers along familiar paths, blinding them to different approaches and types of evidence. Disciplines roughly aligned with expressed position on HM: social science and management tended to make a positive assessment, environmental scholars were split (perhaps along chosen response variables) and experimental scientists largely equivocated. Integrative work that combines these various approaches is necessary to overcome this polarization but this must come with mutual respect as well as better understanding of norms, methods, evidence, vocabulary and rhetoric from other fields and domains of practice. Moreover, the grazing community should seek to expose and if possible resolve competing understandings via transparent examination within the context of potential application, drawing scientists together with farmer experts and research users of various kinds.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170517000308.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Insight Grant #435-2015-0702 to KS by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, 2015–2019. The authors would like to thank Anatoliy Gruzd and Philip Mai at the Social Media Lab, Ryerson University, for hosting CK during the summer of 2015 and anonymous reviewers, Graciela Rusch, John R. Parkins, Edward Bork and Walter Willms for feedback that has improved the work.