Introduction

The province of Málaga (southern Spain) has a population of nearly 1.6 million. Attracted by its 175 km of coastline and its 26 protected nature reserves, 1.8 million tourists visit the province every year (INE, 2015). One feature that has been boosted with a view to strengthening the tourist sector is local cuisine, based on traditional recipes and local food; these are showcased in a number of local food fairs and festivals, including the Málaga Goat Festival in Casabermeja; the Perota Soup Day in Álora and the Handmade Cheese Fair in Teba. A number of public and/or private initiatives have also been launched, among them Km0 Gastro Club, Carta Malacitana, the Spanish Association of Málaga Goat Breeders, Guadalhorce Tourism and Sabor a Málaga. One might reasonably expect that this potential food demand, coupled with the drive to support local cuisine, would favor local agri-food development in a province with 313,000 ha of arable land (MADECA 2014) and 73,900 head of cattle (JA, 2014). Yet 43% of small- and medium-sized farms in this province have gone out of business over the last 10 yr (INE, 2015).

Málaga is not the only province affected. According to reports and statistics published by the European Commission, the number of farms in the EU-27 fell by 25% between 2000 and 2010; 98% were small farms (Forti and Henrard, Reference Forti and Henrard2014).

This process can be attributed, in many cases, to the absorption and concentration of food supply chains by multinational companies (Segrelles, Reference Segrelles2010), and to the strategic role of these companies as intermediaries between producer and consumer. Basically, it imposes certain supply requirements, prices and/or payment terms which are difficult to face by small- and medium-sized farms (MAGRAMA, 2006, 2010; García and Rivera, Reference García, Rivera, Montagut and Viva2007). In 2015, for example, 73,7% of food purchases by Spanish households were made in supermarkets, hypermarkets and discount stores (MAGRAMA, 2016); the five major operators in this sector accounted for 50.4% of market share (Reyes, Reference Reyes2016).

Alternatives put forward to improve the sustainability of small- and medium-sized farms have focused on two major lines: redesign of farms using new multifunctional models (Renting et al., Reference Renting, Oostindie, Laurent, Brunori, Barjolle and Jervell2008); and innovative forms of marketing (Hendrickson and Hefferman, Reference Hendrickson and Hefferman2002; Renting et al., Reference Renting, Marsden and Banks2003; Venn et al., Reference Venn, Kneafsey, Holloway, Cox, Dowler and Tuomainen2006; Chiffoleau, Reference Chiffoleau2009; Day-Farnsworth et al., Reference Day-Farnsworth, McCown, Miller and Pfeiffer2009; King et al., Reference King, Hand, Di Giacomo, Clancy, Gomez, Hardesty, Lev and McLaughlin2010), related to a certain degree of differentiation on the basis of the production process, the provenance and quality of the produce (Diamond and Barham, Reference Diamond and Barham2011), and the establishment of closer relationships with local or distant consumer communities.

As various authors have reported, consumers are increasingly aware that local food tends to be of higher quality, more natural, fresher and tastier, and also contributes both to the economy of rural areas and to their environmental sustainability, thus improving the welfare of farmers and farming communities (Guptill and Wilkins, Reference Guptill and Wilkins2002; Winter, Reference Winter2003; Born and Purcell, Reference Born and Purcell2006; Kneafsey et al., Reference Kneafsey, Venn, Schmutz, Balázs, Trenchard, Eyden-Wood, Bos, Sutton and Blackett2013). This has led to constant growth in the number of consumers seeking more sustainable neighborhood models which enable them to buy local food and in doing so support local farmers (Pérez and Vázquez, Reference Pérez and Vázquez2008; Adams and Salois, Reference Adams and Salois2010; Calle et al., Reference Calle, Soler and Vara2012; Focus Group SFSCM, 2014).

In this respect, short food supply chains (henceforth SFSCs), in their various guises, may provide an economic solution to the gradual decline in the market share of small- and medium-sized farms and thus, in the last analysis, improve their sustainability. However, and despite the favorable context for the development of SFSCs in the province where this case study was performed, the attempts made so far to implement SFSCs have failed to build up a market sufficiently large to guarantee the sustainability and continuity of the vast majority of small- and medium-sized farms.

The current study sought to examine why SFSCs are not helping to solve the sustainability problem small- and medium-sized farms are experiencing. Three different aspects of this situation, from the perspective of the production sector interested in these potential alternative chains, have been analyzed. First, the configuration of existing SFSCs; secondly, the obstacles encountered by SFSC initiatives based on small- and medium-sized farms when attempting to implement them, which may be hindering their adoption and; thirdly, to identify some learnings that could help to address these constraints.

About the concept of local food and SFSCs

There is no single, clear definition of what constitutes local food, or indeed SFSCs, applicable to the diversity of current production, processing, marketing and distribution systems (ENRD, 2012). Three different approaches have been used to develop a theoretical definition of what is ‘local’. According to the first approach, the term ‘local’ can be applied to food produced, processed, marketed and consumed within a circumscribed geographical area (Morris and Buller, Reference Morris and Buller2003). There appears to be no clear limit to this area, nor has there been any attempt to reconcile the various views in national or EU legislation; instead, limits appear to be dictated by context (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Comfort and Hillier2004). In France, for example, the maximum distance is often set at 50 miles, whereas for UK farmers’ markets it is reduced to 30 miles (Focus Group SFSCM, 2014). When applied to conventional distribution, the geographical concept of ‘local’ also varies considerably, covering anything from regions to whole countries (Abatekassa and Peterson, Reference Abatekassa and Peterson2011).

A second approach links the idea of ‘local’ to a distinctive value and quality associated with a given geographical region (Murdoch et al., Reference Murdoch, Marsden and Banks2000; Barham, Reference Barham2003; Renting et al., Reference Renting, Marsden and Banks2003). The geographical origin of a product is thus taken as a guarantee, primarily of certain distinctive features linked to that region, due to the biophysical attributes of the region, the raising there of native breeds or varieties or the use of traditional production processes (Abatekassa and Peterson, Reference Abatekassa and Peterson2011; Cuéllar and Castillo, Reference Cuéllar-Padilla, Castillo, Castillo and Martínez2015). Examples include Protected Geographical Indications—such as ‘Chivo Lechal malagueño’ [Malaga Suckling Goat] and ‘Sabor a Málaga’ [Taste of Málaga] and, more particularly, Protected Designations of Origin.

The third approach focuses on environmental, social and cultural aspects of local foods. Here, geographical distance, administrative limits and specific quality attributes are subordinated to an emphasis on linkages and networks within a given community, on the development of agroecologically friendly production and marketing practices and on the establishment of more horizontal relationships between stakeholders (O'Hara and Stagl, Reference O'Hara and Stagl2001; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Comfort and Hillier2004; Ilbery and Maye, Reference Ilbery and Maye2005; Feagan, Reference Feagan2007). This adoption of horizontal mechanisms, coupled with closer personal involvement, leads to new ways of generating trust, such as participatory guarantee systems (Cuéllar and Calle, Reference Cuéllar-Padilla and Calle2011).

The conceptual framework governing SFSCs is highly diverse, not only in terms of forms of organization and sales techniques but also in terms of the internal social processes driving these channels and their immensely varied socio-economic, ecological and territorial ramifications.

Most authors appear to agree that neither the number of middlemen nor the distance between producer and consumer are critical to a definition of a short supply chain (Marsden et al., Reference Marsden, Banks and Bristow2000). Indeed, there appears to be no consensus regarding the number of intermediaries, although it is certainly assumed that SFSCs operate with fewer middlemen than other supply chains. Some authors thus provide no maximum number (Marsden et al., Reference Marsden, Banks and Bristow2000; Renting et al., Reference Renting, Marsden and Banks2003), while others suggest that the number should be ‘minimal’ or, ideally, nil (Ilbery and Maye, Reference Ilbery and Maye2005). The definition of ‘circuit court’ provided in 2009 by the French Ministry of Agriculture includes just one intermediary between producer and consumer (e.g., shop, restaurant and school canteen). Processors (e.g., slaughterhouses, oil-mills, etc.) are regarded not as intermediaries but as service providers (Kneafsey et al., Reference Kneafsey, Venn, Schmutz, Balázs, Trenchard, Eyden-Wood, Bos, Sutton and Blackett2013).

Marsden et al. (Reference Marsden, Banks and Bristow2000) and the authors of later studies (Renting et al., Reference Renting, Marsden and Banks2003; Soler and Calle, Reference Soler and Calle2010; Focus Group SFSCM, 2014) stress that a key characteristic of the new SFSCs is their capacity to re-socialize or re-spatialize food. Food reaches the consumer embedded with information on the food itself, the production methods employed and the people involved. Such foods are commonly defined by the locality or even the specific farm where they are produced. Another major feature is the emphasis on building relations of trust and transparency between the actors in the chain, and especially between producer and consumer. This ‘allows the consumer to make value-judgements about the relative desirability of foods on the basis of their own knowledge, experience or perceived imagery’ (Marsden et al., Reference Marsden, Banks and Bristow2000 p. 2). Thus ‘shortening’ the supply chain is not just a question of physical distance or the number of agents involved, but also, fundamentally, a question of building shared values and trust in regional quality and/or environmental sustainability, and of the organizational and cultural conditions established in trading. It is what has been identified as ‘value chains’.

For other authors, including Sevilla et al. (Reference Sevilla, Soler, Gallar, Vara and Calle2012), the main issue, apart from the physical shortening of the distance traveled by the food product, is that of practically and actively redefining the power relationships between the agents involved. The aim should be to empower producers and consumers, and bring them closer together as part of a win–win strategy. This consideration places much tighter limits on the kinds of supply chains employed, since local brands and Designations of Origin do not entail the redefining of these parameters.

In this paper, in order to select the initiatives through which we were going to identify the difficulties that small- and medium-sized farms face when developing SFSCs, we established criteria that were readily identifiable prior to in-depth analysis of individual experiences: (a) physical proximity, establishing the boundaries of local at the administrative demarcation of the province (in this case the province of Málaga); (b) marketing approach defined in terms of both number of intermediaries (maximum of one) and geographical proximity (production, processing and sale within the province of Málaga).

Methodology

A method based on structural analysis was used in order to achieve these aims, drawing on a case study. The idea was to obtain and process information on the problem, taking into account the knowledge, visions and social structures (Alberich, Reference Alberich and Villasante2002; Cuéllar and Calle, Reference Cuéllar-Padilla and Calle2011) of the actors involved in the production and marketing of local food in the province of Málaga.

Research was carried out in several stages. Experiments by producers in implementing short supply chains in the province were mapped, using primary and secondary sources, and after the criteria already defined.

The study focused on three sectors—meat, dairy and fruit and vegetable. Meat and dairy sectors were chosen because of the funding source interests (a producers’ cooperative network). And the fruit and vegetable sector was chosen partly because it is the sector which has launched most SFSC initiatives in the province, and partly because it employs highly innovative processes, and was thus able to provide other perspectives and experiences.

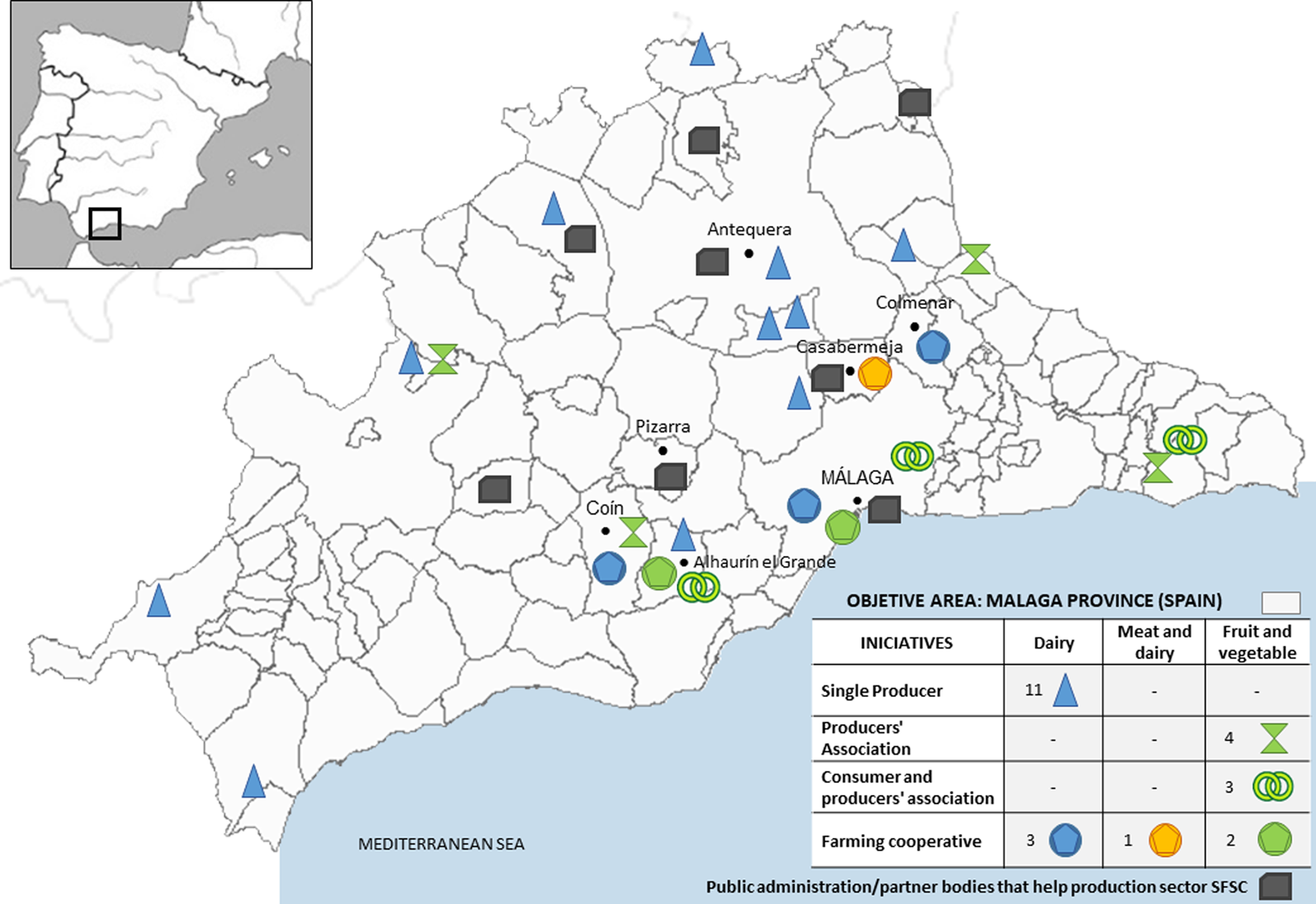

A total of 24 initiatives were studied (see Fig. 1), accounting for almost 2500 local farmers, i.e., 1.9% of the province's farms according to data published by the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (2009).

Fig. 1. Producers’ initiatives on SFSCs studied.

The mapping process also included systematization of initiatives sponsored by the public administration and/or partner bodies with a view to helping the production sector to market produce through SFSCs. A total of eight initiatives were included from this group.

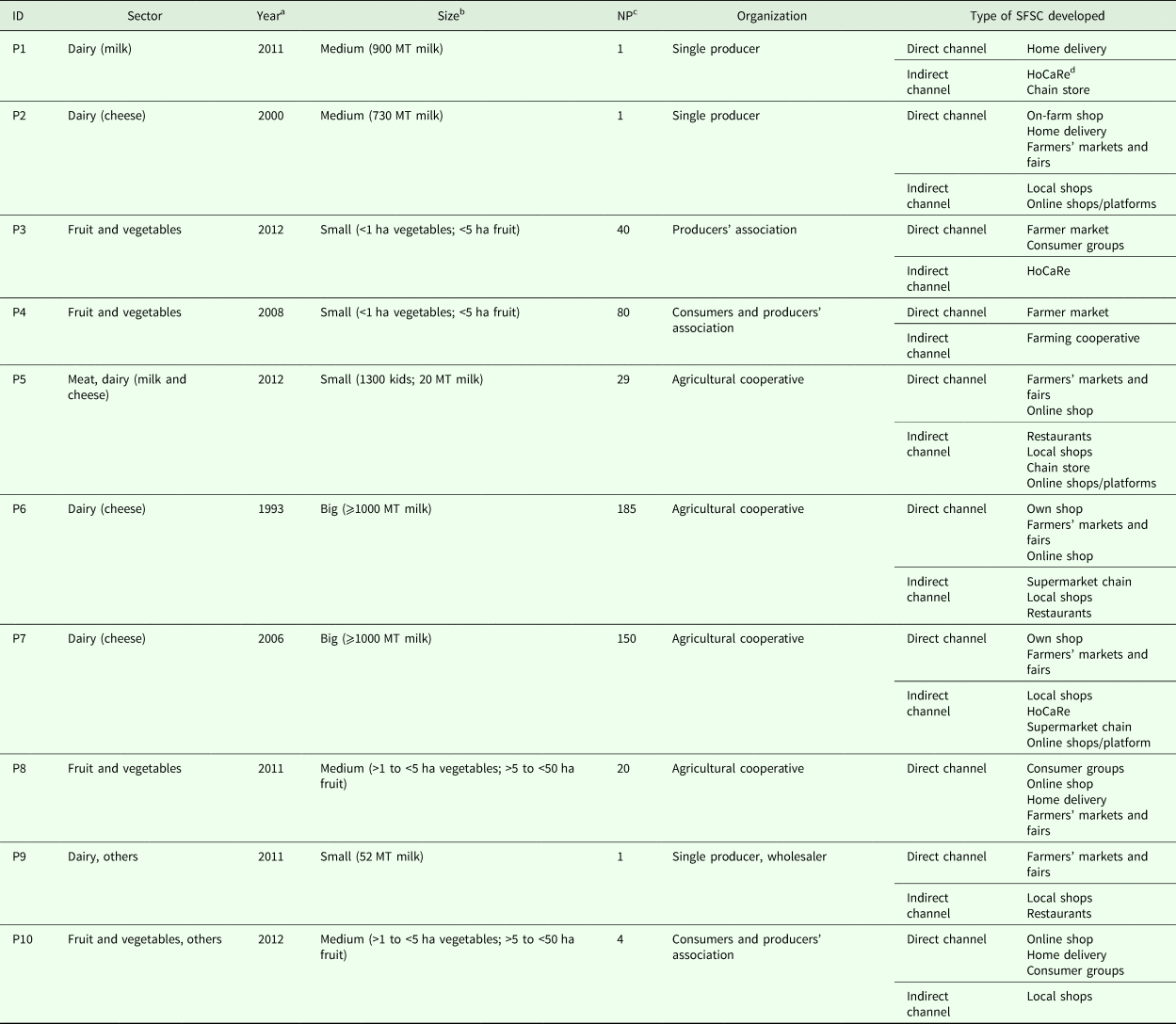

Finally, interviews were carried out with a total of 13 key bodies—ten producers, one online shop and two public administration and/or partner bodies—selected with a view to representing the broadest possible range of organizational structures and SFSCs implemented by the production sector. A detailed description of the cases studied can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Interviewed key informants profile.

a Year, year that started SFSC.

b Size, production volume sold through SFSC.

c NP, Number of producers involved.

d HoCaRe: HOtels, CAtering and Restaurants.

Semistructured interviews were designed in order to answer to the main objectives of the research: to systematize the characteristics of the SFSC developed, difficulties and barriers found by the initiatives when developing SFSCs and good practices and learnings that might be helpful to overcome them. The information was analyzed using software Atlas.ti, that has helped to organize the answers and to establish relations between the main elements identified, as well as main trends in terms of barriers and difficulties.

Systematization of SFSCs under a producers’ perspective

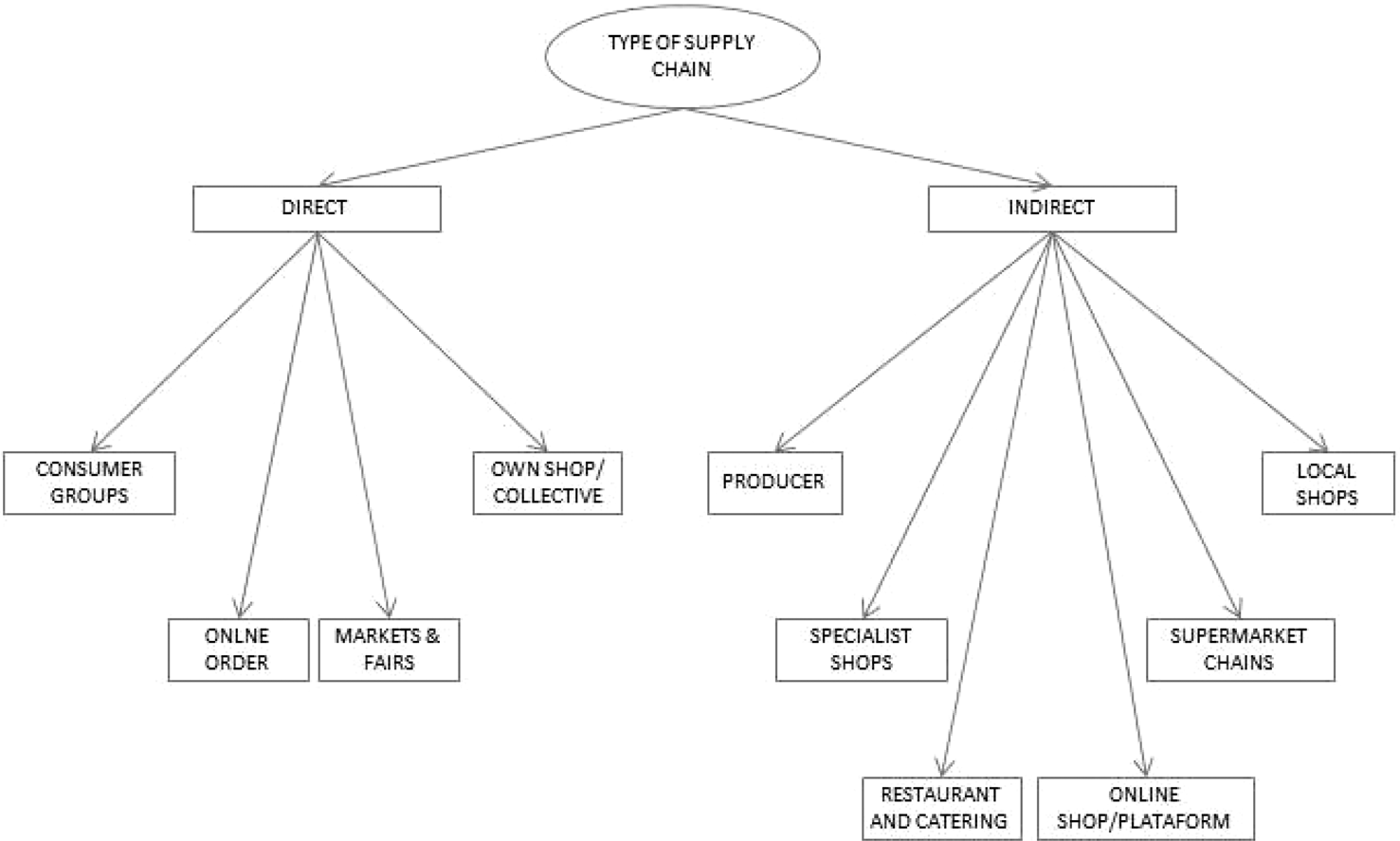

The SFSCs mapped varied considerably in terms of configuration, a finding also reported by other authors both for Andalusia (Soler and Calle, Reference Soler and Calle2010; González et al., Reference González, Haro, Ramos and Renting2012; Sevilla et al., Reference Sevilla, Soler, Gallar, Vara and Calle2012) and for Europe as a whole (Karner, Reference Karner2010; ENRD, 2012; Kneafsey et al., Reference Kneafsey, Venn, Schmutz, Balázs, Trenchard, Eyden-Wood, Bos, Sutton and Blackett2013). The primary distinction in terms of the type of channel used was between ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ channels. ‘Direct’ channels include those in which the food is sold from the producer straight to the consumer, through consumer groups, farmers’ markets and fairs, producers’ on-farm shops—individual or collective—or at the processing site, as well as online orders with home delivery or delivery to pick-up points. ‘Indirect’ channels are those in which food is sold through an intermediary. It may include other producers, physical shops (independent shops or chain stores), the hotel and catering sector or online shops/platforms managed by other agents representing producer groups or product-based groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Description of SFSCs by type of channel implemented.

The main interesting findings while making the map were the following. First, we identified that some of the criteria used by a number of authors to classify SFSCs—among them Renting et al. (Reference Renting, Marsden and Banks2003), Venn et al. (Reference Venn, Kneafsey, Holloway, Cox, Dowler and Tuomainen2006), González et al. (Reference González, Haro, Ramos and Renting2012) and Kneafsey et al. (Reference Kneafsey, Venn, Schmutz, Balázs, Trenchard, Eyden-Wood, Bos, Sutton and Blackett2013)—are scarcely explicative under a producers perspective; criteria such as the relationship between consumers and producers and the role of this relationship in constructing value and meaning or community, for example. Although important to analyze, from the perspective of producer-driven initiatives, a given channel may encompass various forms of participation, various kinds of relationships with the consumer and differences in the construction of value. Moreover, these may be developed in other spaces, and thus to some extent cease to be tied to the actual food purchase. Thus, although there may be some match between the SFSCs used and a given type of producer/consumer relationship and value construction, the degree of cooperation and collective interaction within a given channel may vary considerably, depending on the stakeholders and the relational spaces involved rather than on the channel chosen.

Secondly, this classification helps to identify the various options open to the producer, who normally develops more than one of them. Several combinations are possible and, in most cases, single producers/organizations need to implement a number of different SFSCs in order to sell the whole production.

Thirdly, some organizations make simultaneous use of SFSCs and other channels, giving rise to what Ilbery and Maye (Reference Ilbery and Maye2006) and López et al. (Reference López, del Valle and Velázquez2015) term ‘hybrid strategies’. Authors found that producers and organizations producing large volumes but with limited diversification still tend to opt for non-SFSCs. Even so, they have a very positive view of SFSCs, which they regard as favoring proximity with the consumer and generating added value. Small producers with diversified output and/or links to other groups display a clear preference for SFSCs. Farmers and organizations producing medium volumes tend to adopt hybrid strategies: those producing a limit range of products and not tending to associate with other groups with a view to diversification are more interested in opening/expanding non-SFSCs, whereas those with more diversified output generally opt to strengthen existing SFSCs.

Fourth, we have identified five factors or key elements that determine several different chain configurations which facilitate adaptation to producers, that is, in the same SFSC model, different configurations related to these factors can be found: (a) use of own and shared resources (tangible and intangible); (b) the functions to be assumed; (c) the motivations of the participant producers; (d) the kind of relationship sought and (e) the values to be transmitted.

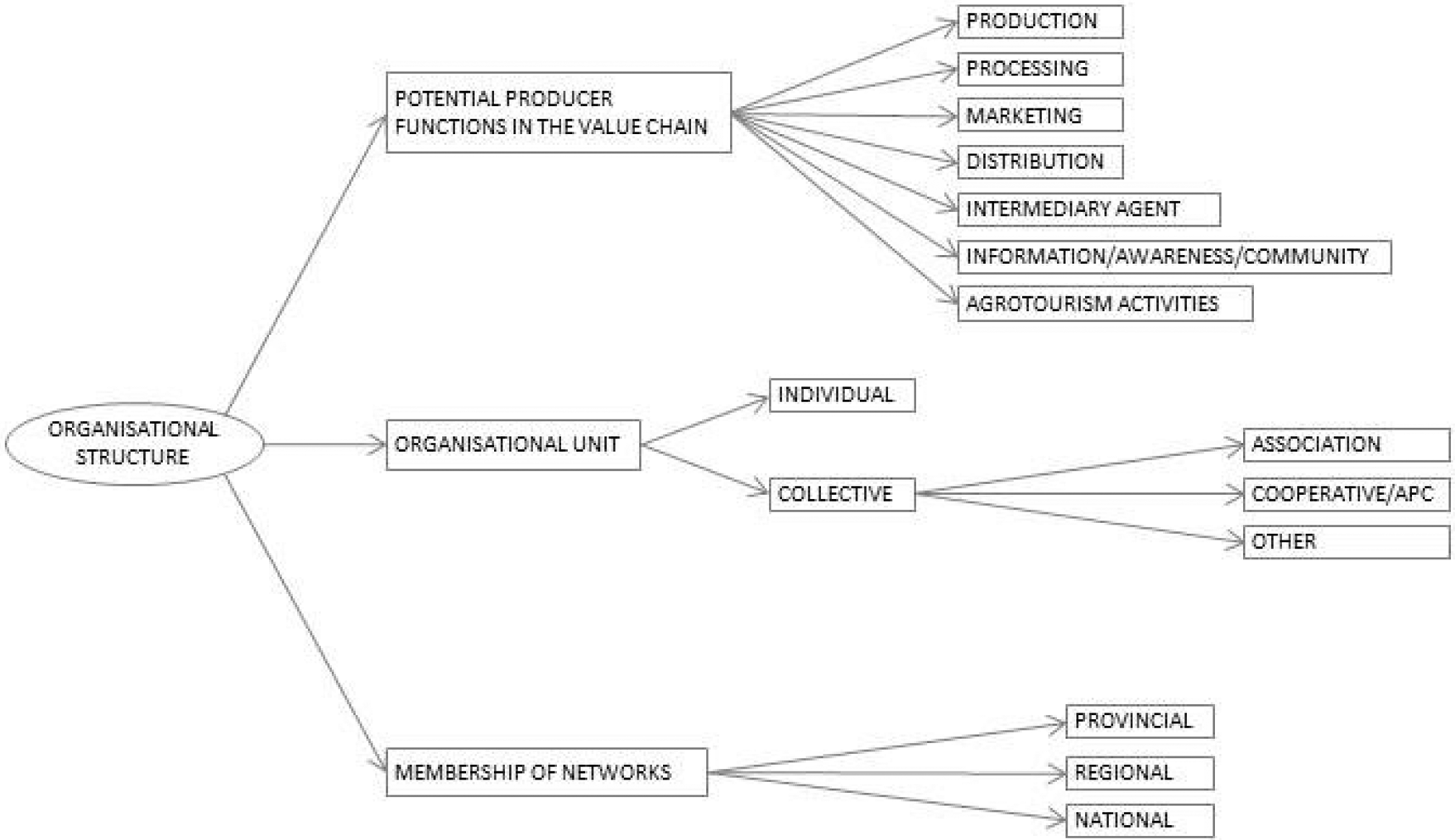

These key elements are about: first, the range of potential functions that the producer might undertake within the marketing channel, which would be governed to a large extent by the resources invested and the skills developed. A producer might simply produce, or might also take part in the processing, marketing and distribution of his/her own produce and that of others, and might even be involved in training/awareness-raising or agritourism.

Secondly, the number of people comprising the organizational structure. In some cases, the initiative might be the work of a single producer, while in others it might involve formal or informal organizations such as farmers’ associations or cooperatives, with a view to sharing out some of the functions. Members of these organizations might sell their produce individually, or jointly with other group members.

Thirdly, linkage with other initiatives or structures, enabling advantage to be taken of the synergies provided by networks of varying complexity operating at provincial, regional, national or international level (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Description of SFSCs by organizational structure.

Some of the producers’ associations, for example, were created with the aim of providing spaces for direct marketing and awareness-raising, by organizing markets and running activities there. Common spaces like these help producers to engage with each other, and may lead both to the emergence of groups, within the farmers’ association, with a particular interest in expanding their marketing channels, and to the building up of contacts and sharing of skills enabling some producers to market their produce individually and to distribute that of other producers. One such group can additionally belong to a regional direct-marketing network and might also establish links with nationally based groups.

SFSCs as solutions for small- and medium-sized producers: barriers and learnings

Despite the initiatives implemented, the number of small- and medium-sized farms continues to decline, and fewer than 2% of farms are involved in SFSCs. This study identified a number of constraints preventing larger-scale implantation of SFSCs that are intrinsic to these supply chains. In some cases authors present learnings from the case study that could help to overcome these barriers.

Required infrastructure, capacities and logistics

In order to market their produce through SFSCs, producers need a certain logistical infrastructure, which varies as a function of the type and volume of the produce itself, the need for processing, storage conditions, distribution points and relationships with consumers.

Moreover, the producer—as indicated earlier—has to take on new roles. In many cases, due to lack of resources, shortage of time to launch new activities and/or lack of training, producers are obliged to make new investments and contract new staff, all of which leads to increased costs.

Additionally, producers need to have at their command a flexible, dynamic logistical infrastructure enabling them to dispose of their produce (particularly in the case of seasonal foods consumed fresh) and to adapt smoothly to market circumstances. These factors generate uncertainty and are regarded as a risk, particularly in terms of the stability of contracted staff and the need to finance the investments required.

According to other sources (cf. TRAGSATEC, 2013), logistical issues are among the major constraints for online SFSCs, due to high transport costs. In our case, the main logistical constraint is linked to the size and volume of produce transported, regardless of the channel used.

Cooperation schemes observed are an answer to this barrier. They are based essentially on: (a) sharing resources, infrastructure and logistics, leading to reduced costs, improved efficiency and larger channels; (b) broadening the range of products on offer and mitigating the seasonality of production through the sale of produce from other farms, either acting as an intermediary or through exchange of produce; (c) adopting a common approach and engaging with the administration on legislative issues and (d) sharing insights.

This practice, however, is less widespread in the livestock sector, due basically to a greater fragmentation of farms, the need to process products and/or more stringent health and hygiene requirements (transport of live animals, packing, cold chain regulations, etc.). Even so, there are interesting innovative schemes whereby a small food processing facility is placed at the disposal of local producers who want to manufacture their products and get their own brand of a concrete product. It is the case, for instance, of a collective cheese factory launched by a dairy products cooperative. Another example of this practice can also be found in different business incubators in the EU that offer a commercial kitchen with license (Lyons, Reference Lyons2002). This allows the producer to embark on a commercial activity without needing to make heavy investments, and at the same time to learn about processing and acquire marketing experience.

Other schemes include external actors such as distributors. Producers stress the importance of building horizontal trust-based relationships, with distributors who must believe in the project/product, as a means of establishing mutually beneficial arrangements which have no adverse implications for the consumer or customer (other type of relationships are identified as unsatisfactory). An interesting initiative related to this idea is the regional food hubs taking place in the USA, that allow local producers to access larger markets by organizing the local offer and counting on useful services related to production, distribution and marketing (Barham et al., Reference Barham, Tropp, Enterline, Farbman, Fisk and Kiraly2012).

Some producers operating online ordering systems use a network of shops as pick-up points; this facilitates the process for the consumer, concentrates orders at a limited number of delivery points and thus reduces costs. Most of these collective solutions drive us to the following difficulty related to the wide spreading of SFSCs.

The importance of social linkages based on food and difficulties associated

SFSCs mean in many cases that producers band together with a view to pooling efforts and pursuing shared interests, which poses certain challenges. One of these is that producers may find it difficult or not able to cope with the strains arising when taking joint decisions within an associative or cooperative structure. This is due, among others, to cultural considerations: the absence of a participatory tradition; the passive attitude of certain members; the selfish attitude of members who place personal interests before the overall group vision and the role of the member as a mere user in selling the produce, with no sense of ownership of the project. A further contributory factor is the difference between members in terms of production systems and economies of scale, which may hinder the establishment of fully horizontal relationships within the association itself, since the larger-scale members will wield power and influence over the rest.

Moreover, although the creation of synergies and cooperation with other stakeholders is acknowledged as important, it is not always regarded as easy. Obstacles detected are primarily linked to local issues; certain models have become deeply rooted in given areas, and their particular characteristics contrast sharply with those of other working models; rivalry, and the fear of reduced competitiveness, may give rise to mistrust and clashes between stakeholders, making it difficult to reach an understanding.

A number of authors including Dyer and Singh (Reference Dyer and Singh1998) and Zander and Beske (Reference Zander and Beske2014) note that proximity is essential to overcome some of these barriers. Collaborative efforts are based on long-term trust and especially on reciprocity. It is essential that each party pursue a specific aim that fits into an overall general objective. Prior internal analysis of the enterprise itself and external analysis of the alliances to be constructed can help, as it can favor a common approach and strategic review of the proposed alliance. A number of producers stressed the need to have a clear idea of the issues involved, and to focus on common, general interests rather than personal interests, which in the long-term results in higher advantages.

Proximity is also identified as crucial for a sound relationship with the consumer. Findings suggest that when personal contact is lost and the relationship becomes more mechanical and detached, the consumer gradually reduces the volume and frequency of his/her orders, becomes more demanding and sets product price above other considerations. This finding suggest that considering SFSC as a marketing channel with certain technical characteristics (number of intermediaries, distance, for instance), regardless of other intangible factors such as values and personal relations will not help the development of such chains. Incorporating this important aspect of SFSCs will allow to assume, and design consequently, that these are key issues that must be taken into account.

Basically, it must be considered that the time required to nurture communications and maintain personal relationships with customers is a guarantee to ensure consumer satisfaction and loyalty (Barroso and Martín, Reference Barroso and Martín1999; Cobo and González, Reference Cobo and González2007). And it poses something of a dilemma for the producer, who often has to choose between maintaining and enhancing customer relations or devoting the energy to finding new customers. The SFSC mechanism thus requires that top priority be given to ensuring consumer satisfaction and loyalty; so the SFSC expansion will be conditioned by the capacity of maintaining a high level of communication and personal relations with consumers. Some producers have found that a direct relationship with the consumer generates other added values, including personal acknowledgment of the producer's efforts and sustained, long-term consumption. These findings tally with relationship marketing and emotional marketing theories which regard keeping existing customers, rather than attracting new clients, as the key to business success (Barroso and Martín, Reference Barroso and Martín1999). According to this approach, customer satisfaction linked to quality and service creates loyalty, prompting new sales at a lower cost (Cobo and González, Reference Cobo and González2007).

Producers have also found that loyal customers becomes allied as they often act as advertisements, promoting the product by recommending it to people they know. Loyalty strategies, such as ‘friend’ and ‘partner’ schemes offering discounts or products access facilities, tend to be successful.

Another key strategy for some of these models is the creation of groups or communities, with a view to enhancing relationships through transparency and proximity, enabling the consumer to identify with the product and to participate in the project to the extent that he/she feels comfortable in doing so. Theses links are strengthened not just by face-to-face dealings but also by social or festive activities, which might help to stabilize and extend a developed SFSC. Examples of such activities include workshops on the manufacturing of certain products, open days at farms and processing sites, talks on responsible consumption, etc. The emotional experience creates a personal link between producer and consumer which far transcends the mere exchange of goods.

Internet can be a useful tool used not only as a sales channel but also to strengthen these social links with consumers. Websites, blogs and social media are regarded as valuable tools, providing a comfortable, easy way for users to identify shared interests, from the pleasure of sharing an elaborate meal made with local food to various outlooks on life in a rural/urban environment. They also enable users to interact and exchange information, and to identify the SFSCs best suited to their purchasing habits.

The need to combine several SFSCs

Private consumer purchases are dictated by household requirements, and orders therefore tend to be small. In the case of direct selling, farmers need a large network of customers/consumers in order to dispose of their output.

All respondents stressed that a single SFSC was insufficient for marketing all their produce. Since some foods are perishable, various SFSCs need to be used simultaneously, together with other channels at lower prices, in an attempt to adapt to different consumer habits.

They report that dealing with various SFSCs and a large network of customers/consumers implies considerable effort, and that more time and money has to be spent on managing, selling and distributing produce.

Not all products are suitable for SFSCs

Some respondents noted that when marketing via SFSCs it is essential that the product be original and of good quality, without ceasing to be artisanal. They added that, since few customers are interested in products of this kind and also willing to pay for quality, the producer must identify clearly the potential market in order to adapt to it, and must also know where to find it and how to access it.

They also highlighted the need to organize production and create a corporate image, taking into account the importance of format and presentation (size, packaging, etc.) and ensuring that these appeal to the target clientele. Sometimes, producers may not be sufficiently aware of such strategies, and respondents recommended seeking advice from professional marketing experts.

Conclusions

SFSCs are not answering to the expectations created around them related to the sustainability of small- and medium-sized farms because of many constraints. In order to identify them, rather than focusing on different types of producer–consumer relationship or on the values associated with specific channels, our research highlights the importance of understanding what various types of channel entail from the producer's perspective.

The producer profiles best suited to specific channels—and the skills the producer needs to develop before implementing SFSCs—are governed by the functions required of him/her, by the individual vs collective nature of the process, and by the potential need for larger-scale linkages. Findings suggest that the intensity of the producer–consumer relationship and the values transmitted through it are in many cases unrelated to the supply chain itself, and depend more on the stakeholders involved and on the relational spaces articulated in parallel to the supply chain.

The numerous skills required of producers are one of the main constraints to consider. Producers, when entering into SFSCs, quite apart from producing foodstuffs, have to take on the additional roles of distributor, salesman, advertiser and public relations expert. These requirements have a threefold dimension: technical (know-how), psychosocial (skills) and financial (investments); whose solutions become harder in the context of small- and medium-sized producers. At the same time, since these are often group initiatives (either undertaken by producers’ associations or involving consumer input), there is also a need for group emotional management, conflict-solving and communication skills, which few producers possess.

Apart from the intrinsic exigence of each SFSC, most producers opted to use a combination of SFSCs to dispose of their produce. In practice, a single SFSC is in most of the cases not able to cover producers marketing needs. Multichannel strategies need to be developed, which entails an increased workload for the small producer, who is additionally required to develop new skills, making his/her work considerably more difficult. This becomes ever worse when the producer needs to use also non SFSC, in what have been termed ‘hybrid spaces’. This hybrid, multichannel strategy provides a means of overcoming the insufficient capacity of a single supply chain to absorb a producer's entire output. It is also dictated by the structural characteristics and organizational/logistical skills of each production unit, and by the attempt to adapt products and services to different client-groups with differing needs and purchasing habits. The degree of producer reliance on these hybrid spaces depends essentially on the volume and range of products. Less use is made of hybrid spaces when output is small and more diversified.

In this context, producers often face the dilemma ‘whether to increase the volume of sales through SFSCs or use a range of channels to ensure sale of the entire output’. However, successful initiatives suggest that it must not be resolved at the expense of existing customers’ loyalty. Careful nurturing of, and communication with, all the stakeholders in the chain (intermediaries and consumers) is essential, not just to generate stability but also to guarantee the growth of SFSCs in return for a minimal effort, taking full advantage of synergies with already established mechanisms. This means that growth will be slower, and therefore that more time will be required, but it will lead to greater stability and sustainability in the medium and long term. A striking aspect of this emphasis on caring for the consumer is developing abilities to build socio-affective spaces in parallel to SFSCs; these serve to strengthen links and facilitate acceptance of the product/project. In this respect, online technology is proving extremely useful.

Finally, not every product has a place in SFSCs. The criteria of consumers using SFSCs to purchase local food are linked to quality rather than price or ease of purchase. ‘Quality’ in these channels is understood as referring to produce of identified origin, displaying certain attributes associated with artisanal food products, and transmitting certain values in terms of social and environmental sustainability. This will be related not only with the production process, but also with the presentation and format of products.

A specific sight on SFSCs from a producer perspective put in evidence that not only consumers’ needs facilities in order to get interested in SFSCs, but also producers. The numerous exigences SFSCs pose to producers are in the basis of the stagnation of this type of alternative for small- and medium-sized producers.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture & Sport/MINECO, Banco Santander and CeiA3 for financing this research.