Introduction

Integrating fall-sown cover crops into annual cropping systems can enhance multiple ecosystem services (Schipanski et al., Reference Schipanski, Barbercheck, Douglas, Finney, Haider, Kaye, Kemanian, Mortensen, Ryan, Tooker and White2014). Overwintering cover crops provide suppression of winter annual weeds (Osipitan et al., Reference Osipitan, Dille, Assefa and Knezevic2018), limit soil erosion and phosphorus runoff (Adeli et al., Reference Adeli, Tewolde, Jenkins and Rowe2011), reduce nitrogen (N) leaching by removing residual nitrate (NO3−) from the soil (Thapa et al., Reference Thapa, Mirsky and Tully2018), and contribute to long-term improvements in physical, chemical and biological soil health indicators (Wick et al., Reference Wick, Berti, Lawley, Liebig, Al-Kaisi and Lowery2017). However, the use of fall-sown cover crops is limited by narrow growing season windows following late harvested grain crops in the Northeast region of the USA (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Mortensen and Kammerer-Allen2017).

There is renewed interest in interseeding cover crops into field corn early in the growing season to provide more consistent establishment in the northern USA (Curran et al., Reference Curran, Hoover, Mirsky, Roth, Ryan, Ackroyd, Wallace, Dempsey and Pelzer2018; Noland et al., Reference Noland, Wells, Shaeffer, Baker, Martinson and Coulter2018) and Canada (Belfry and Van Eerd, Reference Belfry and Van Eerd2016). Maximizing fall cover crop biomass production is critical for reducing nitrate leaching over the winter (Staver and Brinsfield, Reference Staver and Brinsfield1998; Hashemi et al., Reference Hashemi, Farsad, Sadeghpour, Weis and Herbert2013), reducing soil erosion potential and increasing suppression of winter annual weeds (Baraibar et al., Reference Baraibar, Hunter, Schipanski, Hamilton and Mortensen2018; Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Curran and Mortensen2019). Until recently, interseeding was mainly accomplished by broadcasting cover crops into standing corn using a tractor-mounted spreader early in the growing season or later in the growing season using aerial (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Allan and Baker2014) or ground equipment such as high-boy drop seeders (Hively et al., Reference Hively, Duiker, McCarty and Prabhakara2015). However, broadcasting cover crops on the soil surface provides minimal seed-to-soil contact and can leave seed prone to desiccation under dry conditions, which reduces plant establishment rates (Meisinger et al., Reference Meisinger, Hargrove, Mikkelsen, Williams, Benson and Hargrove1991; Baker and Griffis, Reference Baker and Griffis2009). Recent studies and on-farm trials have shown that drill-interseeding is a viable alternative to broadcast methods for establishing cover crops in no-till corn production systems in the Northeast (Curran et al., Reference Curran, Hoover, Mirsky, Roth, Ryan, Ackroyd, Wallace, Dempsey and Pelzer2018) and upper-Midwest (Noland et al., Reference Noland, Wells, Shaeffer, Baker, Martinson and Coulter2018). The viability of drill-interseeding has increased due to the recent development of high clearance interseeder grain drills that enable cover crop sowing in up to 1-m tall corn and facilitates greater seed-to-soil contact compared to broadcast methods.

Resource, or niche, partitioning is the primary underlying ecological principle that informs the development of cash- and cover-crop management practices in interseeded systems (Vandermeer, Reference Vandermeer1989; Brooker et al., Reference Brooker, Bennett, Cong, Daniell, George, Hallett, Hawes, Iannetta, Jones, Karley, Li, McKenzie, Pakeman, Paterson, Schob, Shen, Squire, Watson, Zhang, Zhang, Zhang and White2015; Bybee-Finley and Ryan, Reference Bybee-Finley and Ryan2018). High clearance interseeding grain drills facilitate both spatial and temporal resource partitioning by limiting cover crops to inter-row zones and permitting establishment across a range of corn heights and growth stages. Previous studies in the Mid-Atlantic (Curran et al., Reference Curran, Hoover, Mirsky, Roth, Ryan, Ackroyd, Wallace, Dempsey and Pelzer2018) and northern Great Plains (Bich et al., Reference Bich, Reese, Kennedy, Clay and Clay2014) show that drill-interseeding after the V3 (leaf collar method; Abendroth et al., Reference Abendroth, Elmore, Boyer and Marlay2011) stage in corn minimizes cover crop competition and does not impact grain yields. Integration of other cultural practices, such as adjustments in targeted corn densities, may facilitate resource partitioning and minimize competition in organic systems (Baributsa et al., Reference Baributsa, Foster, Thelen, Kravchenko, Mutch and Ngouajio2008). Youngerman et al. (Reference Youngerman, DiTomasso, Curran, Mirsky and Ryan2018) showed that fall biomass of interseeded cover crops was partially mediated by effects of corn population on light transmission into the corn canopy and use of flex-ear corn hybrids can potentially facilitate planting corn at lower rates (5–10%) without negative effects on organically-managed corn grain yields. Interseeding cover crop species with complementary, or different, resource acquisition traits can also improve interseeding performance (Curran et al., Reference Curran, Hoover, Mirsky, Roth, Ryan, Ackroyd, Wallace, Dempsey and Pelzer2018), though a narrow suite of shade-tolerant species consistently establish in interseeded corn systems (Caswell et al., Reference Caswell, Wallace, Curran, Mirsky and Ryan2019).

In the Northeast USA, there is interest in extending interseeding practices to organic, tillage-based grain corn production. Organic grain corn production relies on fertilization with organic N inputs such as animal manure, green manure and compost, which can result in residual nitrate pools that are prone to winter leaching (Finney et al., Reference Finney, Eckert and Kaye2015). In addition, frequent use of intensive tillage and cultivation increases the risk of soil erosion in organic systems. Consistent establishment of N-scavenging cover crops using interseeding could reduce N leaching potential and improve soil conservation, particularly in the corn–soybean phase of a rotation.

Based on informal surveys of organic grower networks in our region, labor constraints and equipment investments remain barriers to the adoption of drill-interseeding. Inter-row cultivation is a fundamental practice for controlling weeds in organic grain crops and is typically implemented multiple times early in the growing season, with the last cultivation occurring later than the V5 stage. Consequently, organic weed control practices may significantly constrain the agronomic window for interseeding and increase cash crop competition. However, organic weed control practices may increase the viability of broadcast interseeding, which is a lower cost alternative to specialized grain drills. Inter-row cultivation is typically accomplished with cultivators equipped with ‘duckfoot’ hoe shares that control small weeds by cutting the soil layer and mixing the loosened soil (Znova et al., Reference Znova, Melander, Lisowski, Klonowski, Chlebowski, Edwards, Nielsen and Green2017). Therefore, broadcasting cover crops into soil loosened by cultivation may result in seed-to-soil contact that is comparable to drill-interseeding.

In this study, we compared cover crop interseeding establishment methods (broadcast vs drill) with standard grower practices, including winter fallow or post-harvest seeded cereal rye (Secale cereale L.), at three Pennsylvania (PA) commercial organic farms to evaluate the effects of interseeding establishment method on cover crop biomass production, corn yield, weed abundance and nitrogen cycling. In collaboration with participating organic farmers, we interseeded a cover crop mixture that was designed to improve N scavenging and identified multiple production and conservation performance targets of interest.

Materials and methods

Experimental design and field operations

Field experiments were conducted in 2015–2016 and repeated within different fields in 2016–2017 at PA organic farms located in Lancaster (40°05′15N, 76°04′06W), Mifflin (40°31′45N, 76°28′38W) and Union (40°55′08N, 77°08′25W) counties. Participating farms were representative of small- to mid-scale organic farms in southeastern and central PA that include feed grains, perennial forages and cover crops in 5- to 6-yr rotations. Site-specific soil and crop management practices before and during field corn production are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Soil characteristics, crop management and precipitation at Pennsylvania organic farms in Lancaster, Union and Mifflin counties (LC, UC, MC) in 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 growing seasons

a SIN, soil inorganic nitrogen.

Three treatments were imposed in field corn using a randomized complete block design with four replicates. Individual plots ranged from 3- to 6-m wide and 120 to 210 m in length depending on field constraints. Each farm planted corn on 76 cm row spacing. Treatments included (1) the organic farm's standard post-harvest practice following corn; (2) drill-interseeding a cover crop mixture just after last cultivation; and (3) broadcast-interseeding a cover crop mixture just after last cultivation. Winter fallow was the standard post-harvest treatment at the two more northern locations (Mifflin and Union Co). At the more southern location in Lancaster Co, the standard post-harvest practice was cereal rye (S. cereale L.; ‘Aroostook’) broadcast at a rate of 134 kg seed ha−1 and lightly incorporated using a double-disk. The cover crop mixture in both interseeding treatments included annual ryegrass (‘KB Supreme’; KB Seed Solutions, Harrisburg, OR, USA), orchardgrass (‘Potomac’; Albert Lea Seed, Albert Lea, MN, USA) and forage radish (‘Tillage’; Cover Crop Solutions LLC, Lititz, PA, USA) at a seeding rate of 11 + 11 + 4 kg ha−1, respectively. Species selection was based on farmer-defined objectives and seeding rates were based on our previous experience with on-station and on-farm interseeding research (Curran et al., Reference Curran, Hoover, Mirsky, Roth, Ryan, Ackroyd, Wallace, Dempsey and Pelzer2018) and evaluation of shade-tolerant species (Caswell et al., Reference Caswell, Wallace, Curran, Mirsky and Ryan2019). Cover crops were drill-seeded with a two-row high-clearance grain drill (Interseeder Technologies, Woodward, PA, USA) designed to travel through 75-cm tall corn and seed three rows on 19-cm spacing between 76-cm cash crop rows. Cover crops were pre-mixed and seeded using a single seed box. Cover crops were broadcast-seeded from an elevated platform behind a tractor with a calibrated hand-held rotary spreader. In each experiment, cover crops were interseeded within 24 h of the last inter-row cultivation, which occurred between the V5 and V7 corn growth stage (Table 1).

Sampling methods

Aboveground cover crop and weed biomass were evaluated in the fall just prior to corn harvest and in the spring just prior to cover crop termination (Table 1) by harvesting six randomly located 0.25 m2 quadrats per main plot located between the center of two corn rows. Quadrats were constructed to sample between corn rows (32 by 76 cm) and delineate between inter-row and in-row zones to facilitate weed sampling. Cover crops and weeds were clipped at 2.5 cm above ground level, separated by species and dried for at least 5 days at 65°C and then weighed. Summer annual weeds located in-row (within 5 cm of corn row) were not included in fall samples because cultivation performance was considered the primary driver of in-row summer annual weed abundance in the fall. Both in-row and inter-row weeds were included in the analysis of spring weed biomass. Corn population density was assessed 42 days after interseeding in approximately 3 m length of a row in the center of two corn rows at six random places in each plot. Corn grain was harvested at the plot-level with a combine and weigh wagon at each on-farm location and adjusted to 15.5% moisture.

Cover crop aboveground biomass N content (kg ha−1) was measured in the fall and spring. Three harvested cover crop subsamples per plot were composited by species (excluding weeds) and ground to a fine powder. A subsample of this powder was rolled into a tin capsule and analyzed for carbon and nitrogen concentrations by dry combustion analysis (CHNS-O CE Instruments Thermo Electron Corp Elemental Analyzer EA; Matejovic, Reference Matejovic1996). Total N in weed biomass was estimated using 1.7% N content, which was based on the analysis of composited sub-samples across study locations in the spring of 2017.

Extractable soil inorganic N (SIN) concentrations were measured at five targeted points throughout the season: at corn planting, at the time of cover crop interseeding, in fall after post-harvest cover crop establishment and the following spring before cover crop termination. One soil sample was collected from each main plot by combining six 0.20 m depth by 0.02 m diameter cores. After homogenizing each sample, one fresh 20 g subsample was extracted for inorganic N with 100 mL of 2 M KCl. Following 1 h of shaking, extracts were filtered through Whatman 1 filter paper and frozen until further analysis. Extracts were analyzed colorimetrically for ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3−) concentrations (Sims et al., Reference Sims, Ellsworth and Mulvaney1995; Doane and Horwath, Reference Doane and Horwath2003). Total SIN is reported as the sum of ammonium and nitrate concentrations. Additionally, a subsample of homogenized soil from the first soil sampling event was submitted to The Pennsylvania State University's Agricultural Analytical Services Lab (State College, PA, USA) for standard soil fertility testing.

Statistical analyses

Linear mixed-effects (LME) models were used to conduct null-hypothesis significance tests for cover crop treatment differences in response variables of interest. Model specification varied among response variables due to differences in the standard grower practice treatment (winter fallow or post-harvest seeding) among commercial organic farms.

Models for biomass and yield data collected within the corn growing season were fit using a nested random-effects structure (year/site/block) to account for sources of variation associated with environmental and management differences (location, year) as well as spatial variation within site-years (block). The standard treatment was excluded from the models of cover crop performance (aboveground fall biomass, composition, aboveground cover crop N) and included in weed biomass, vegetative biomass N content (cover crops and weeds) and SIN models. Spring performance metrics (cover crop and weed biomass, aboveground N, SIN) were assessed by the experimental site due to differences in post-harvest management and used a random-effects structure that nested block within a year. Treatment effects on SIN (mg N kg dry soil−1) were first assessed during the corn growing season using a repeated-measures ANOVA in package ‘lme4’ (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) with each sampling date as a within-subject factor.

Cover crop and weed biomass (kg ha−1), cover crop N content (kg N ha−1), total vegetative N content (kg N ha−1) and SIN (mg N kg dry soil−1) were normalized using a log-transformation after adding a constant (1.0). Treatment effects on cover crop composition were assessed by expressing forage radish biomass as the proportion of the total aboveground biomass per plot. Proportion data were normalized using an arc-sin square root transformation. All LME models were fit with restricted maximum likelihood estimations in the ‘nlme’ package (Pinheiro et al., Reference Pinheiro, Bates, DebRoy and Sarkar2017) in R.3.2.5 (R Development Core Team, 2018) and statistical significance of fixed factors was assessed by conditional F-tests. Fitted models were used to estimate marginal means (±s.e.) for each response variable using the emmeans package (Lenth et al., Reference Lenth, Singmann, Love and Buerkner2018). Marginal and conditional coefficients of determination (R 2m and R 2c, respectively) were calculated to describe the proportion of the variance in the response associated with fixed effects only (R 2m) and random plus fixed-effect components (R 2c) of the model using the package ‘MuMIn’ (Nakagawa and Schielzeth Reference Nakagawa and Schielzeth2012).

Results and discussion

Fall cover crop performance

Drill-interseeding increased (P < 0.001) mean fall cover crop biomass production compared to broadcast-interseeding (Table 2). However, interseeding establishment method contributed only 12% of the total variation in the model of fall cover crop biomass, whereas environmental and management conditions associated with site, year and block contributed 62% of the total observed variation. Mean fall cover crop biomass did not exceed 300 kg ha−1 at the Lancaster and Mifflin County site in both years of the study, whereas mean fall cover crop biomass ranged from 750 to 1200 kg ha−1 across study years at the Union County location (Fig. 1a). Fall cover crop biomass production was also comparatively greater in the first study year at each location, which we attribute to normal to above-average precipitation in July and August. Forage radish represented a higher (P < 0.001) proportion of total aboveground cover crop biomass in drill-interseeded (78%) compared to broadcast-interseeding (35%) treatments (Table 2). Interseeding establishment method contributed 20% and environmental-management conditions contributed 48% of the total observed variance (Table 2; Fig. 1c). Interseeding method did not affect (P > 0.05) the ratio of annual ryegrass to orchardgrass in mixtures.

Fig. 1. Mean (a) cover crop biomass, (b) vegetative biomass N, (c) forage radish biomass, (d) forage radish N, (e) weed biomass and (f) soil inorganic N in late-fall at the time of corn grain harvest. Data are presented as within-group (site-year) treatment means (± s.e.), including Lancaster County (LC), Mifflin County (MC) and Union County (UC) sites conducted in 2015 (15) and 2016 (16) crop years.

Table 2. Interseeding treatment effects on plant and soil conditions at the time of corn grain harvest

Treatments with the same letter within columns are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

a Fixed effects are reported using back-transformed (log) estimated marginal means.

b Standard treatment included post-harvest, broadcast-seeding cereal rye at the Lancaster County location and fallow at Mifflin and Union Counties. Dash (–) indicates where treatment is excluded from the analysis.

c R 2m, marginal coefficient of deterimination; R 2c, conditional coefficient of deterimination.

In-season weed suppression

Weed biomass in the inter-row zone differed among treatments (P < 0.001) at the time of corn grain harvest. Drill- and broadcast-interseeding treatments both resulted in lower inter-row weed biomass compared with the standard (i.e., no interseeding) treatment (Table 2). Weed biomass within standard treatments ranged from 58 to 186 kg ha−1 across site-years at the time of corn grain harvest (Fig. 1e), and the average reduction in fall weed biomass due to the presence of interseeded cover crops ranged from 55 to 75% across site-years. Although we did not analyze weed biomass by species, field observations indicated that fall weed biomass was primarily comprised of early-emerging winter annual weeds rather than late-season summer annual weed escapes. Multiple inter-row cultivations were completed by participating farmers at each location prior to interseeding, leaving the inter-row zone primarily weed free at the time of interseeding.

Corn grain yield

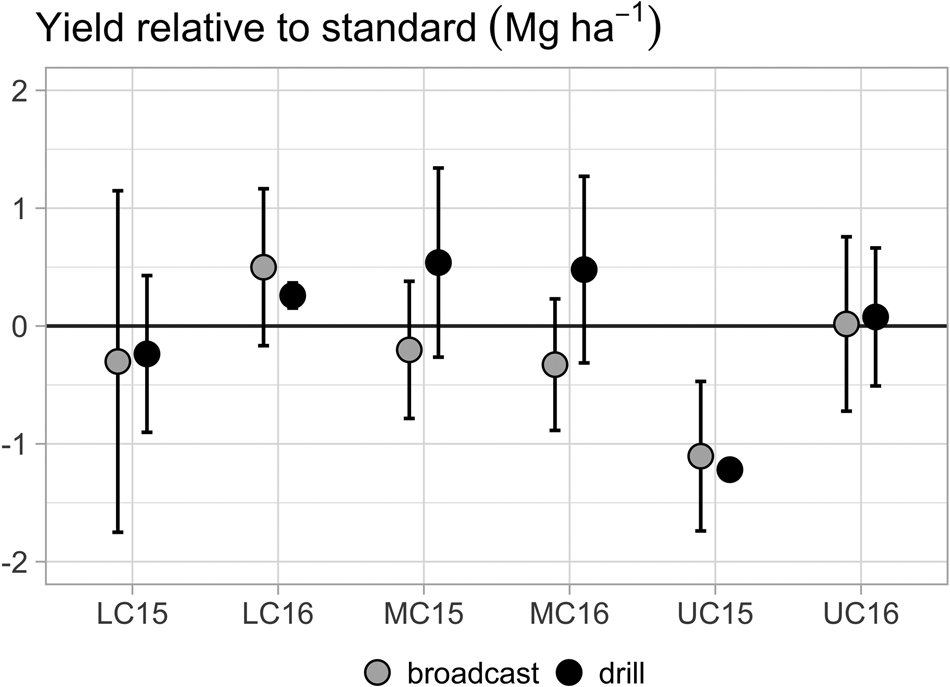

Interseeding treatments did not affect (P > 0.05) corn grain yield (Table 2). Grain yields ranged from 8.0 to 9.7 mg ha−1 across location and years, with higher yields observed at the Lancaster County location (southern) and lower yields observed at the Union County location (northern). Examination of interseeding treatment means relative to the standard treatment shows negligible effects on grain yields within location and years with the exception of Union County in 2015 (Fig. 2). In the 2015 Union County experiment, fall cover crop biomass exceeded 1000 kg ha−1 in both interseeding treatments, which suggests that competition from interseeded cover crops resulted in a yield drag. However, observed trends suggest that low final corn populations (approximately 45,000 plt ha−1) contributed to the cover crop and grain yield response in Union County in 2015.

Fig. 2. Effect size of interseeding establishment method treatment on corn grain yield relative to the standard treatment. Data presented as the mean difference between interseeding establishment method and the standard treatment (winter fallow or post-harvest seeding) within replicates at each site-year, including Lancaster County (LC), Mifflin County (MC) and Union County (UC) sites conducted in 2015 (15) and 2016 (16) crop years. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals.

Spring cover crop and weed dynamics

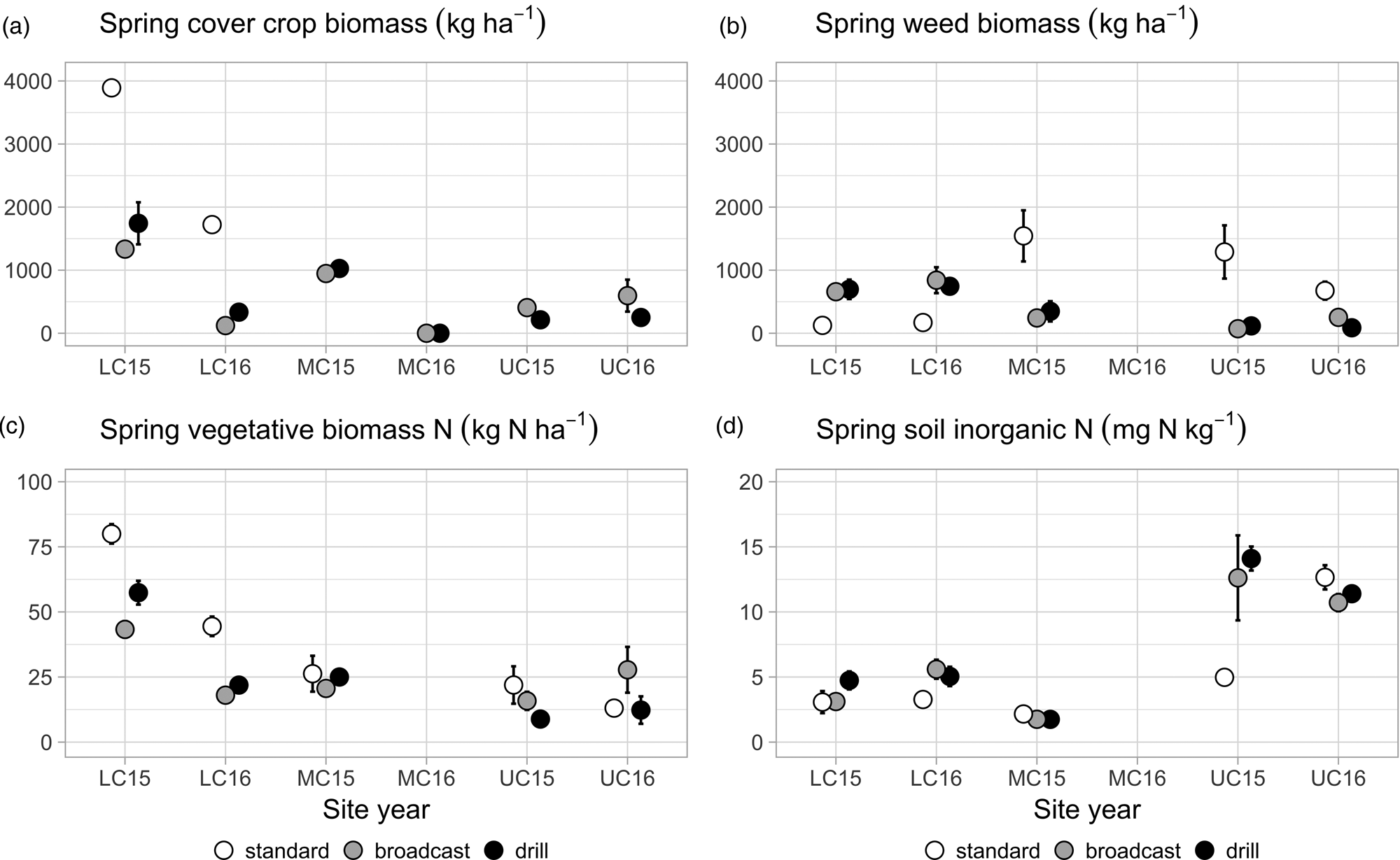

Post-harvest management practices in the standard treatment differed among sites. At the southern location in Lancaster County, cereal rye was broadcast seeded post-harvest, whereas standard treatments remained fallow at the other sites. Consequently, spring performance metrics were analyzed by site (Table 3; Fig. 3). At the Lancaster County site, total aboveground spring cover crop biomass and weed biomass differed (P < 0.001) among treatments. Cereal rye biomass was greater and weed biomass was lower at the time of spring termination in the standard treatment compared with either interseeded treatment. At the Mifflin County location, the analysis was limited to the first study year due to poor establishment and overwintering success of interseeded cover crops in the second year. Poor cover crop establishment in the second year can be attributed, in part, to drought conditions following interseeding (Table 1). In the first year, no differences (P > 0.05) in total spring cover crop biomass production were observed between drill-interseeding and broadcast-interseeding methods and weed biomass was lower (P < 0.001) in both interseeding treatments compared with the standard fallow treatment (Table 3). At the Union County location, aboveground spring cover crop biomass was higher in broadcast-interseeded treatments compared to drill-interseeded treatments and weed biomass was lower in interseeded treatments compared with the standard fallow treatment. Spring cover crop biomass was comparatively lower at the Union County location due to greater relative abundance of winter-killed forage radish (50–95% of total biomass) in the fall, which resulted in reduced stands of the winter-hardy cover crops species, annual ryegrass and orchardgrass, in the mixture.

Fig. 3. Mean (a) cover crop biomass, (b) weed biomass, (c) vegetative biomass N and (d) soil inorganic N in spring prior to cover crop termination. Data are presented as within-group (site-year) treatment means (±s.e.), including Lancaster County (LC), Mifflin County (MC) and Union County (UC) sites conducted in 2015 (15) and 2016 (16) crop years.

Table 3. Interseeding treatment effects on plant and soil conditions in late spring, prior to cover crop termination

Treatments with the same letter within columns by location are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

a Fixed effects are reported using back-transformed (log) estimated marginal means.

b Standard treatment included post-harvest, broadcast-seeding cereal rye at the Lancaster County location and fallow at Mifflin and Union Counties. Dash (–) indicates where treatment is excluded from the analysis.

Nitrogen availability and retention

SIN concentration (mg N kg dry soil−1) in the top 20 cm of soil was not affected (P > 0.05) by interseeding treatments during the corn growing season in the repeated-measures analysis of each site-year. However, differences in SIN among participating farms were observed at the time of interseeding (Table 1), likely due to unique manure or compost input legacies and soil properties (i.e., % SOM).

Both interseeding methods (drill, broadcast) resulted in higher total N in aboveground vegetative biomass than the standard (i.e., no interseeding) treatment at the time of corn grain harvest (Table 2). Forage radish contributed a significantly greater proportion of total N in drill-interseeding (63%) compared to broadcast (29%) interseeding. Environmental and soil management conditions associated with experimental site-years contributed 53 and 23% of the total variance in the total aboveground vegetative biomass N and forage radish N models, respectively (Table 2; Fig. 1b and 1d). No interseeding treatment effects (P > 0.05) were observed in the analysis of SIN at the end of the corn growing season (Table 2). Within experimental year and location, treatment-level means of SIN were below 15 mg N kg dry soil−1 except for Union (32–74 mg N kg dry soil−1) and Mifflin County (59–73 mg N kg dry soil−1) in 2016 (Fig. 1f). Fall SIN was negatively correlated with forage radish N among treatments at the Union County location in 2016, whereas no relationship between soil and aboveground plant N was observed at the Mifflin County location.

In the spring, total N in aboveground cover crop biomass differed among interseeding treatments at two of three locations (Table 3). At Lancaster County, post-harvest seeding cereal rye resulted in higher aboveground cover crop biomass N (60 kg N ha−1) and total vegetative biomass N (62 kg N ha−1) compared to interseeding treatments (Fig. 3a). At Union County, broadcast interseeding resulted in higher aboveground cover crop biomass N than drill interseeding, likely due to the higher percentage of radish in the drilled treatment leading to lower grass biomass in the spring after radish mortality. Due to high levels of weed recruitment (Fig. 3b), total aboveground biomass N was higher in the fallow treatment compared to drill-interseeding but did not differ compared to broadcast-interseeding (Table 3). Treatment effects on SIN at spring cover crop termination were detected at two locations (Table 3). Post-harvest seeding cereal rye at Lancaster County resulted in lower SIN compared to the drill interseeding treatment but did not significantly differ from the broadcast interseeding treatment. At the Union County location, drill-interseeding resulted in higher SIN compared with the standard fallow treatment but the weedy fallow did not significantly differ from broadcast interseeding.

Discussion

Our results indicate that compared to broadcast establishment methods, drill-interseeding (1) improves fall cover crop biomass production, (2) mediates the expression of cover crop mixtures, and (3) produces negligible to marginal benefits related to N retention and weed suppression. It is particularly instructive to note that differences in environmental conditions and soil and crop management among organic farms explained more variation in cover crop biomass production than the establishment method. These results are consistent with recent studies that have observed greater cover crop biomass production when utilizing drill-interseeding practices compared to broadcasting into the inter-row (Bich et al., Reference Bich, Reese, Kennedy, Clay and Clay2014; Noland et al., Reference Noland, Wells, Shaeffer, Baker, Martinson and Coulter2018). Recent studies have also reported similar levels of fall biomass production and interannual variability of interseeded cover crops on conventionally managed grain farms (Curran et al., Reference Curran, Hoover, Mirsky, Roth, Ryan, Ackroyd, Wallace, Dempsey and Pelzer2018) and within organic field crop experiments (Youngerman et al., Reference Youngerman, DiTomasso, Curran, Mirsky and Ryan2018) in the Mid-Atlantic region.

Forage radish dominance in drill-interseeded mixtures had important implications for N retention and weed suppression benefits in the spring growing season. We suggest that comparatively greater relative abundance of forage radish in drill-interseeded mixtures was due to differences in seed size among interseeded species. An individual forage radish seed weighs 15 mg, whereas annual ryegrass and orchardgrass seeds weigh <4 mg. Germination and emergence of larger seeded species are likely to be greater than smaller seeded species when sown at a shallow depth (Benvenuti et al., Reference Benvenuti, MacChia and Miele2001). The effects of seeding depth on establishment rates and competitive interactions between cover crops is a critical, but not well understood, factor that is likely to mediate the expression of cover crop mixtures and should be considered in the design of cover crop mixtures and establishment strategies.

Our results support previous studies that have shown that forage radish can provide significant fall N scavenging services (Dean and Weil, Reference Dean and Weil2009) and winter annual weed suppression (Lawley et al., Reference Lawley, Weil and Teasdale2011). However, forage radish-dominated cover crop mixtures in the fall are likely to induce higher SIN availability during the winter due to the combined effects of rapid forage radish decomposition and reduced establishment of winter-hardy grasses that could retain plant available N in late winter and early spring (Finney et al., Reference Finney, White and Kaye2016; Kaye et al., Reference Kaye, Finney, White, Bradley, Schipanski, Alonso-Ayuso, Hunter, Burgess and Mejia2019). Though estimates of SIN (20-cm depth) and aboveground cover crop N in fall and spring did not fully account for N-cycling dynamics, our results suggest that while there is an opportunity for targeting N retention by interseeding cover crop mixtures, over-expression of winter-killed species such as forage radish may reduce N retention and increase spring N loss potential. Interseeding winter-hardy grass monocultures may improve N retention and weed suppression services in the spring. For example, Noland et al. (Reference Noland, Wells, Shaeffer, Baker, Martinson and Coulter2018) reported that interseeded cover crops that produced more than 390 kg ha−1 of dry matter biomass in the spring reduced SIN compared to fallow treatments and, among interseeded species, interseeded cereal rye produced the greatest N retention benefits. Moving forward, understanding interactions between interseeding establishment methods, cover crop species, seeding rates and soil fertility on the expression of cover crop mixtures will be necessary to optimize N retention services of interseeded monocultures and mixtures.

Finally, our results highlight the need to better define the environmental conditions where interseeding cover crops provide more consistent conservation benefits than post-harvest seeding following grain corn production. Post-harvest seeding winter rye improved spring cover crop biomass potential, N retention and weed suppression in comparison to interseeding at our southern location, which has a fall growing season window sufficient for the consistent post-harvest establishment of cover crops. At our more northern locations, interseeding cover crops resulted in significant weed suppression benefits in the fall and spring compared to winter fallow. However, interseeding produced negligible N retention benefits at termination due to high weed biomass production and N retention in winter fallow treatments. Weedy fallow management practices have been shown to reduce N loss compared to bare fallow (Wortman, Reference Wortman2016) but our results suggest that, with improved management, interseeding practices offer an opportunity to target both nutrient and weed seedbank management goals.

In summary, our results suggest that broadcasting cover crops at last cultivation can produce similar benefits to drill-interseeding at lower labor and equipment costs in organic systems. However, further research is needed to determine if drill-interseeding reduces intra-annual variability in cover crop performance compared to broadcast-interseeding on organic grain farms over a wider range of environmental and management conditions. Our on-farm research highlighted additional management considerations that may constrain the adoption of drill-interseeding practices. In our experiments, last-cultivation and interseeding occurred just prior to when corn heights would limit the use of tractor operations, creating a narrow agronomic window to accomplish both operations. Modifying equipment to facilitate cultivation and interseeding operations in one pass could reduce labor constraints and lead to increased adoption of interseeding practices on organic grain farms. Finally, additional research is also needed to contrast conservation benefits and management tradeoffs between interseeding- and post-harvest establishment methods in regions where post-harvest seeding following grain corn is feasible.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by USDA-OREI Award 2014-51300-22231 and received partial support from the Pennsylvania State University College of Agricultural Sciences and the Department of Plant Science. We are grateful for the collaboration with Wade Esbenshade, Elvin and Michael Ranck, and Harvey Hoover. We are also thankful for the skilled technical assistance from Brosi Bradley, Tosh Mazzone and Andrew Morris.