Introduction

According to the Land Degradation and Restoration Assessment report of the United Nations Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)—the first comprehensive empirical assessment of land degradation and restoration globally—land degradation induced by human activities is undermining the well-being of over 3 billion people globally and driving species extinction, climate change and food insecurity at unprecedented levels (IPBES, Reference Scholes, Montanarella, Brainich, Barger, ten Brink, Cantele, Erasmus, Fisher, Gardner, Holland, Kohler, Kotiaho, Von Maltitz, Nangendo, Pandit, Parrotta, Potts and Prince2018). The recent IPBES Global Assessment report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, which builds on the Land Degradation and Restoration Assessment report, highlights the need for ‘transformative change’—involving a system-wide restructuring across technological, economic and social realms—which must start at the local scale if the Earth is to be restored, conserved and used sustainably (IPBES, 2019). Specific to agriculture, the IPBES calls for the reorienting of production systems towards integrated farming approaches that promote sustainable land management (SLM) and biodiversity conservation.

In smallholder farming settings in particular, SLM has been emphasized as a suitable pathway to address land degradation. SLM denotes the use of land and land-based resources in meeting human needs in a manner that ensures their long-term integrity and productive potential (Dallimer et al., Reference Dallimer, Stringer, Orchard, Osano, Njoroge, Wen and Gicheru2018). In the past few decades, agroecology interventions have been widely deployed in smallholder farming contexts to promote SLM and improve productivity. Agroecology is an approach to agriculture that integrates principles of SLM and local knowledge in the management of agroecosystems to promote sustainable agriculture (Altieri, Reference Altieri2002; Dumont et al., Reference Dumont, Vanloqueren, Stassart and Baret2016; Mdee et al., Reference Mdee, Wostry, Coulson and Maro2019). Agroecology is grounded on the principle that an agroecosystem should mimic the functioning of the natural ecosystem with less dependence on external inputs (Gliessman, Reference Gliessman2014). This entails ensuring a balance in energy and nutrient flows by minimizing energy loss, promoting nutrient recycling and other internal processes that reinforce synergistic outcomes for improved food production and environmental conservation (Altieri, Reference Altieri2002; O'Rourke et al., Reference O'Rourke, DeLonge and Salvador2017; Snapp, Reference Snapp, Snapp and Pound2017). At the farm level, agroecology entails the application of SLM practices such as mulching, manuring/composting, crop rotation, intercropping, livestock integration, agroforestry, etc. Although most SLM practices are within the scope of agroecology, there are some noteworthy differences between the two approaches. For instance, agroecology upholds the principle of minimizing the use of external inputs such as synthetic fertilizers and herbicides, while SLM may encourage some combination of both organic and synthetic soil amendment practices (High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) of the United Nations Committee on World Food Security, 2020).

Although agriculture is the mainstay of the Malawian economy, the potential of the sector continues to be derailed by multiple stressors including climate change and environmental degradation (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Pollard and Mwenda2010; Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Young, Young, Santoso, Magalasi, Entz and Snapp2019; Katengeza et al., Reference Katengeza, Holden and Fisher2019). Malawi remains one of the world's poorest countries that continue to grapple with achieving food security for its increasing population (Bezner-Kerr et al., Reference Bezner-Kerr, Patel and Nagothu2014; Kassie et al., Reference Kassie, Stage, Teklewold and Erenstein2015). Over the past decade, the Malawian government responded to the problem of soil infertility and sub-optimal productivity in smallholder agriculture through the Farm Input Subsidy Programme which provides farmers with subsidized synthetic fertilizers and hybrid maize seeds. However, empirical evidence shows that the most vulnerable farmers do not benefit as much from these subsidized inputs (Holden and Lunduka, Reference Holden and Lunduka2013; Bezner-Kerr and Patel, Reference Bezner-Kerr, Patel and Nagothu2014).

Land degradation is of major concern in Malawi. In a recent agricultural land suitability assessment, Li et al. (Reference Li, Messina, Peter and Snapp2017) observe that about 40% of agricultural land in Malawi is unsuitable for crop cultivation. Meanwhile, continuous cultivation on marginal lands further contributes to declining soil fertility (Li et al., Reference Li, Messina, Peter and Snapp2017; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Steinfield, Chiwasa and Ganunga2019). Notwithstanding increasing evidence of the positive potential of SLM in smallholder farming settings (Kassie et al., Reference Kassie, Zikhali, Pender and Köhlin2010; Ngwira et al., Reference Ngwira, Thierfelder and Lambert2013), in Malawi, where land degradation is a major challenge, SLM practices continue to be underutilized among smallholder farmers (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Steinfield, Chiwasa and Ganunga2019; Chinseu et al., Reference Chinseu, Dougill and Stringer2019).

While there is considerable research on the underlying reasons for the slow adoption of SLM practices among smallholder farmers, very little empirical research has focused on exploring the determinants of SLM adoption based on the turnover duration of diverse SLM practices. This is despite evidence that smallholder farmers tend to prioritize SLM practices with short-term turnover (e.g., composting and crop residue incorporation)—practices that yield benefits within a single planting season—than practices with long-term turnover (e.g., agroforestry), which typically yield benefits after a year or more (Liniger et al., Reference Liniger, Studer, Hauert and Gurtner2011; Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016). As explained by Adimassu et al. (Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016:1014), ‘the rationale for this classification [short-term and long-term SLM practices] is that farmers’ investments in different SLM practices depend on how quick the return from their investments is’. Consequently, agronomic SLM practices such as mulching, cover cropping, composting and manuring are conceptualized as investments for short-term returns given that they are typically targeted at supporting crop growth in a given planting season, while most physical SLM practices are considered investments whose returns materialize after a relatively longer period—usually more than one farming season (Shiferaw and Holden, Reference Shiferaw and Holden2001; Akinnifesi et al., Reference Akinnifesi, Ajayi, Sileshi, Chirwa and Chianu2010; Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016). There is empirical evidence that the decision to adopt either short-term or long-term SLM practices may be shaped by the associated high upfront and maintenance costs, as well as the perceived benefit-to-cost ratios for adopters who would have to wait much longer to break even on investments in long-term SLM practices compared to short-term SLM practices (Dallimer et al., Reference Dallimer, Stringer, Orchard, Osano, Njoroge, Wen and Gicheru2018). The choice of short-term and/or long-term SLM practices may also be shaped by other underlying socioeconomic and cultural factors such as land access, labor availability and social norms. While it is crucial for farmers to prioritize both short-term and long-term SLM practices for the maintenance of other ecosystem services besides the immediate improvement of soil fertility, the factors that shape the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices are not well understood. Understanding these determinants can generate useful policy insights for ensuring the holistic adoption of SLM practices.

Drawing data from a cross-sectional survey with smallholder farming households who participated in an agroecology intervention in Malawi that trained farmers on different SLM practices, this study contributes to the literature by exploring the determinants of the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices. We hypothesize that plot level conditions, capacity and socioeconomic factors will shape the concurrent adoption of long-term and short-term SLM practices.

Literature review

In the context of increasing environmental degradation and climate change, there is growing attention on ways to encourage the uptake of a broad spectrum of SLM practices (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2020). The overarching goal of SLM is to structure human–environment interaction in a manner that ensures the sustainable flow of the provisioning, regulating, cultural and supporting services we derive from ecosystems. In its landmark report on guidelines and best practices for SLM in SSA, the FAO (2011) identified three broad but reinforcing dimensions of SLM namely, the ecological, economic and socio-cultural (Hurni, Reference Hurni1997). The ecological dimension emphasizes restoration in areas where degradation has occurred using diverse ecological techniques. The FAO (2011) categorized these ecological techniques into: (1) agronomic measures that improve soil cover and fertility (e.g., crop residue recycling, mulching, composting and intercropping); (2) vegetative measures such as agroforestry, cover cropping and integration of perennial herbs and grasses such as vetiver (Vetiveria zizanioides L); (3) structural measures (e.g., terracing, stone bunds and shelterbelts); and (4) management measures (e.g., land use management approaches such as crop–livestock integration and species diversification). Economically, SLM should yield benefits that offset the cost of investments incurred by land users and policy makers. Intricately linked to the ecological and economic dimensions is the social dimension. The ecological and management techniques and the associated financial investments thereof, should contribute to improving livelihoods through reductions in food insecurity and poverty in a manner that is commensurate with the sociocultural aspirations of communities. Central to SLM is the application of ‘appropriate’ technologies based on contextual dynamics including topography and socioeconomic factors. As argued by Hurni (Reference Hurni2000), appropriateness in this context is a function of the core pillars of sustainability such that a given SLM technology can be considered appropriate if it is ecologically protective, socially acceptable, economically viable and reduces risk.

Over the past two decades, research on the determinants of farmers’ adoption of SLM practices has grown tremendously. In a recent comprehensive review, Adimassu et al. (Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016) categorized the factors shaping farmers’ decision to adopt SLM practices into three main groups namely, capacity factors, incentives and external factors. The factors related to capacity include financial capital, landholding, labor availability and knowledge. For instance, there is empirical evidence that farmers who have access to: financial capital (Nyanga et al., Reference Nyanga, Kessler and Tenge2016), enough household labor (Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Kessler and Hengsdijk2012) and land (Gebremedhin and Swinton, Reference Gebremedhin and Swinton2003; Tenge et al., Reference Tenge, De Graaff and Hella2004; De Graaff et al., Reference De Graaff, Amsalu, Bodnar, Kessler, Posthumus and Tenge2008) tend to invest more in SLM practices. Other studies have identified several household and individual level factors including age and education as important proxies of farmers’ capacity to adopt SLM practices (Nkonya et al., Reference Nkonya, Gerber, Baumgartner, von Braun, De Pinto, Graw and Walter2011; Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016; Ndagijimana et al., Reference Ndagijimana, Kessler and Asseldonk2019).

The decision to adopt SLM practices is also shaped by incentives emanating from cost-benefit considerations. Some scholars have observed that the decision to adopt SLM practices is an intertemporal choice between the cost of adoption and the cost of non-adoption (De Graaff et al., Reference De Graaff, Amsalu, Bodnar, Kessler, Posthumus and Tenge2008; Kassie et al., Reference Kassie, Zikhali, Pender and Köhlin2010; Nkonya et al., Reference Nkonya, Gerber, Baumgartner, von Braun, De Pinto, Graw and Walter2011; Tesfaye et al., Reference Tesfaye, Brouwer, van der Zaag and Negatu2016). Thus, each SLM practice has its associated investment cost, maintenance costs and benefits which collectively shape perceived profitability and feasibility (Dallimer et al., Reference Dallimer, Stringer, Orchard, Osano, Njoroge, Wen and Gicheru2018; Giger et al., Reference Giger, Liniger, Sauter and Schwilch2018). This cost may be expressed in financial, labor and time requirements (Wossen et al., Reference Wossen, Berger and Di Falco2015; Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016). Further, the underlying conditions in the physical environment e.g., the incidence of soil erosion and topography may also necessitate the adoption of certain SLM technologies and not others (Tiwari et al., Reference Tiwari, Sitaula, Nyborg and Paudel2008; Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016; Mponela et al., Reference Mponela, Tamene, Ndengu, Magreta, Kihara and Mango2016).

Factors that are external to the local environment such as institutional support as expressed in training on SLM technologies, extension services, government policies on land and availability of credit facilities can also shape farmers’ decision to adopt SLM practices (Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Kessler and Hengsdijk2012). Indeed, research shows that the effectiveness of SLM among smallholder farmers depends partly on institutional support available to farmers, especially the promotion of extension services and trainings on appropriate technologies (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ruiz-Menjivar, Zhang, Zhang and Swisher2019; Packer et al., Reference Packer, Chapman and Lawrie2019). However, other scholars have also observed that improvement in some of these external factors such as access to non-farm income opportunities may act as disincentives for investment in SLM practices (Holden et al., Reference Holden, Shiferaw and Pender2004; Grothmann and Patt, Reference Grothmann and Patt2005).

Conceptual framework

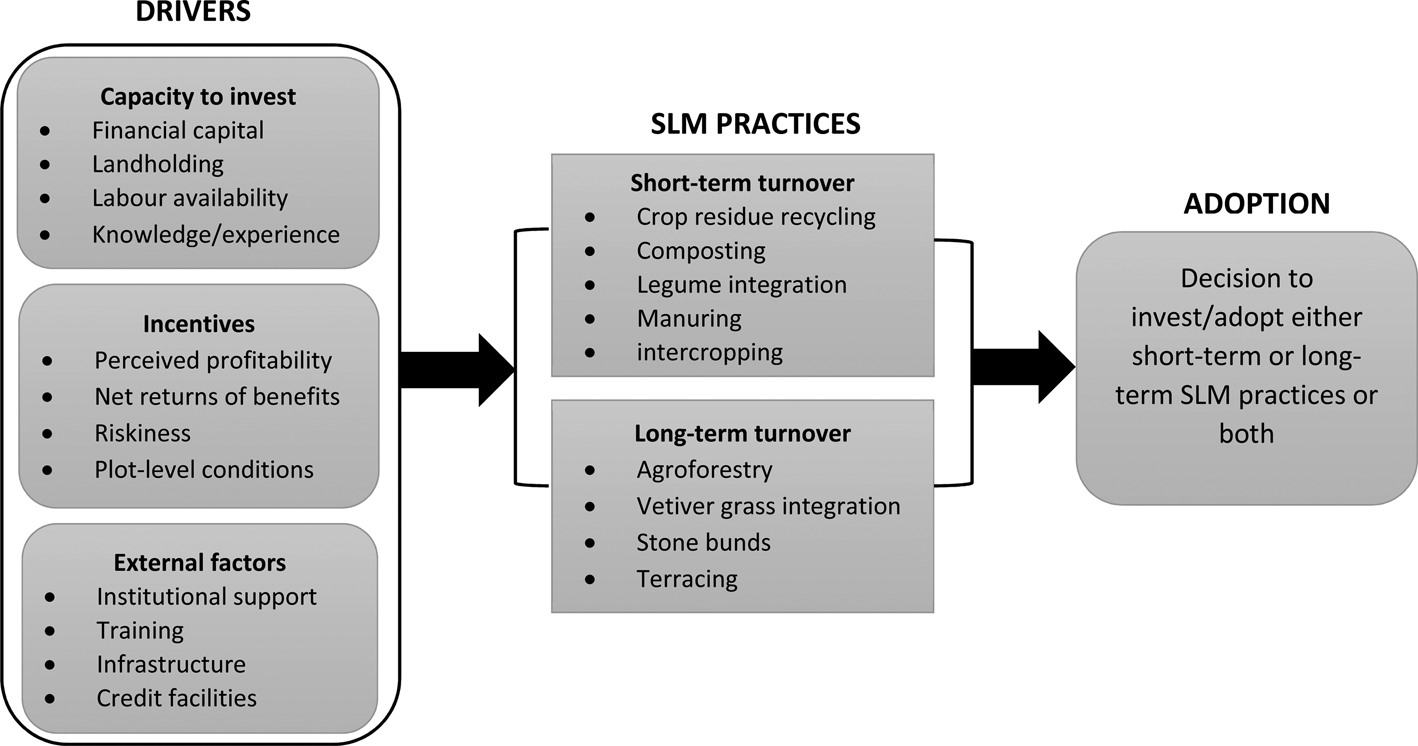

From the review of literature, it is apparent that a wide range of factors shape farmers’ decision to invest in SLM. While the literature provides useful insights on the determinants of SLM adoption, a crucial area that remains less well understood is how adoption decisions may vary based on the turnover duration of benefits for different SLM practices. Given that SLM technologies can have short-term turnover, with benefits accruing to the adopter in a single planting season or long-term turnover with benefits materializing after several farming seasons, the decision to invest simultaneously in both short-term and long-term SLM practices or to selectively adopt from a single category may be shaped by factors related to the capacity of the farmer, incentives and prevailing institutional dynamics.

The classification of SLM practices into short-term and long-term turnovers has been used in the SLM literature (see Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016). Other studies have also clarified the rationale behind this classification (Shiferaw and Holden, Reference Shiferaw and Holden2001; Liniger et al., Reference Liniger, Studer, Hauert and Gurtner2011; Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016). Research shows that poor households may have to meet immediate household needs through investment in SLM technologies that have shorter turnover and can improve soil fertility and productivity in the short-run as opposed to other SLM practices which may not contribute to improving the food security of the household immediately (Issahaku and Abdulai, Reference Issahaku and Abdulai2020). The role of the physical attributes/demands of short-term and long-term SLM practices is also worth noting in explaining this classification. Generally, agronomic SLM practices with short-term turnovers not only require minimal space but also occupy space temporarily compared to long-term practices such as agroforestry, vetiver grass and terracing which take-up more space on the plot over a relatively longer period (Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016). Thus, farmers with limited land may not invest in such space-demanding practices (Smith, Reference Smith2004; Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Mekonnen, Yirga and Kessler2014). Tenure insecurity is another potential factor that can influence SLM adoption. For instance, farmers who are cultivating on rented plots may not invest in long-term technologies like agroforestry due to fear of losing such investments (Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016). Based on these dynamics, we developed a framework (see Fig. 1) that is grounded on the conceptual understanding that the turnover duration of benefits from a given SLM practice is important in understanding SLM adoption decisions of smallholder farmers. Thus, while the ideal situation is for smallholder farming households to adopt short-term and long-term SLM practices concurrently, this may only be possible for certain categories of households. It is therefore important to understand why some categories of farming households may be able to adopt short-term and long-term practices while others resort to selective adoption.

Fig. 1. Conceptual framework.

In the context of smallholder agriculture, the adoption of SLM can be conceptualized as a reflection of diverse drivers in the environment of the actor, working interactively to shape the kind of practices that are prioritized. Thus, the fundamental conceptual basis of our analysis is that, the combination of drivers in the environment of a social actor—for example, a given actor or household may have low labor capacity, be cultivating on a rented land and lacking access to credit—can significantly shape the decision to invest in both short-term and long-term SLM practices.

Methods

Data and sample

This analysis is based on data from a cross-sectional survey with smallholder farmers in Malawi who participated in the Malawi Farmer-to-Farmer Agroecology (MAFFA) project. MAFFA was a five-year participatory agroecology intervention implemented in the Dedza and Mzimba districts. The project team used a farmer-to-farmer knowledge sharing approach to teach smallholder farming households the application of agroecology practices aimed at improving soil fertility, yields and ultimately, household food security. In July 2019, a survey was conducted with a randomly selected sample of households that participated in the intervention as part of efforts to ascertain the adoption of the diverse SLM practices they received training. Figure 2 provides information on the study context.

Fig. 2. Study context.

Given the widespread soil degradation in Malawi and the limited use of SLM practices (Li et al., Reference Li, Messina, Peter and Snapp2017; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Steinfield, Chiwasa and Ganunga2019), a key component of the MAFFA intervention focused on improving soil fertility through the promotion of SLM practices that draw on local resources. Table 1 provides a detailed description of some of the key SLM practices farming households were trained on.

Table 1. Description of SLM practices implemented under the MAFFA project

A wide range of SLM practices have been promoted across Africa in the past few decades. The MAFFA project however, focused on the above practices due to contextual dynamics and the objectives of the project. Amid increasing land degradation and associated food insecurity in the study context, the project focused on SLM practices that poor smallholder farmers could implement using locally available resources. Training in SLM was done using a farmer-to-farmer participatory learning approach. To facilitate farmer-to-farmer knowledge exchange, Farmer Research Teams (FRTs) were formed and trained. These farmers further trained and provided peer support to participating farming households in their respective communities as they implemented the different SLM techniques. Routine community level meetings were led by FRT members to provide opportunities for knowledge exchange. Figure 3 illustrates field-level application of some of the SLM practices promoted under the MAFFA intervention.

Fig. 3. Farm-level application of some SLM practices under the MAFFA project. (a) Agroforestry trees growing on a recently harvested maize field. (b) Vetiver grass planted across the slope on the farm to control erosion. (c) A farmer burying crop residue during land preparation. (d) Mulching of field prior to planting. (e) Legume (pigeon pea) integration in a maize field. (f): A maize field intercropped with soybean.

Data collection was done by trained enumerators who are proficient in the local language. The questionnaire was tested and reviewed to ensure context sensitivity prior to the actual data collection. In every household, the primary farmer responded to the survey on behalf of the household. The survey collected information on household farming practices, especially the application of SLM practices, household food security, nutrition, assets, on-farm and off-farm socioeconomic activities and gender relations. This data enables us to understand the factors that shape the concurrent adoption of long-term and short-term SLM practices.

Measures

We constructed our dependent variable based on the SLM literature (Shiferaw and Holden, Reference Shiferaw and Holden2001; Liniger et al., Reference Liniger, Studer, Hauert and Gurtner2011; Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016). Households were asked whether they applied the different SLM practices they received training on. Following previous studies on SLM adoption (Liniger et al., Reference Liniger, Studer, Hauert and Gurtner2011; Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016), we considered agroforestry, planting of vetiver grass and livestock integration as practices with long-term turnover, thus the materialization of benefits from these practices usually take more than a single planting season, while agronomic SLM practices whose benefits materialize within a single planting season (crop residue integration, mulching, legume intercropping, crop rotation and composting) were classified as short-term SLM practices. Given the overarching objective of understanding the factors associated with the concurrent adoption of SLM practices with short-term and long term turnovers, we created a binary variable coded as ‘both short-term and long-term’ if households adopted at least one short-term and one long-term SLM practice concurrrently, and ‘short-term or long-term only’ if households did not concurrently adopt at least a short-term and a long term SLM practice. While this categorization is useful for understanding the factors associated with the holistic adoption of SLM practices with both short-term and long-term turnovers, it is important to mention that the impact of the above categorized SLM technologies on soil fertility and land management may not be confined to just the short-term or long-term. For instance, although compost application may improve soil fertility in a single cropping season, it could also contribute to improvement in overall soil quality in the future.

The survey also collected information on household socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. Guided by the SLM literature (Gebremedhin and Swinton, Reference Gebremedhin and Swinton2003; Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Kessler and Hengsdijk2012, Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016), we included three blocks of relevant independent variables: ‘capacity’, ‘plot level factors’ and ‘household level characteristics’. Variables on households’ capacity to invest in SLM included size of active household labor, agricultural information sharing (0 = No; 1 = Yes), social support (0 = Never; 1 = Sometimes; and 2 = Always) and household wealth (0 = Poorest; 1 = Poorer; 2 = Middle; 3 = Richer; 4 = Richest). The household wealth variable was created using principal component analysis based on the Demographic Health Survey wealth computation guideline. We generated a composite measure of household wealth and subsequently grouped this into quintiles based on ownership of assets such as televisions, radio, bicycle and corn mill. Given the high incidence of HIV/AIDs and associated chronic conditions in the study context (Palk and Blower, Reference Palk and Blower2018), and the crucial role of health in determining the ability to engage in agriculture, we included a variable on the presence of chronically sick person(s) in the household (0 = Yes; 1 = No) as another proxy of household labor capacity. Plot level factors included farm size and use of fertilizer (0 = Yes; 1 = No). Household socioeconomic and demographic factors included age, level of education, marital status and gender of the primary farmer in the household, food availability (measured based on months food was available after the harvest) and women's autonomy (measured using a set of questions that asked if the primary women in the household could do a number of things by themselves including deciding on what to plant, what to sell and visit to relatives and friends).

Statistical analysis

Given that our dependent variable (SLM adoption) is binary, we employed binary logistic regression to examine the probability of households concurrently adopting short-term and long-term SLM practices. Our analysis was organized at three levels: univariate, bivariate and multivariate. We used univariate analysis to explore the distribution of the dependent and independent variables. We also employed bivariate logistic regression to understand the independent relationship between each of the covariates and the dependent variable. Finally, we used multivariate logistic regression to understand the association between the independent variables and the dependent variable within the same model. The equation for our model can be specified as follows:

where P is the probability that households concurrently adopted short-term and long-term SLM practices, α is the constant, β 1, β 2, …, βk are regression coefficients, and x 1, x 2, …, xk are covariates (Hosmer et al., Reference Hosmer, Lemeshow and Sturdivant2013). We reported findings with odds ratios (ORs), where ORs larger than 1 imply higher likelihood of simultaneously adopting short-term and long-term SLM practices, and those smaller than 1 indicate lower odds of doing so.

Results

Variable descriptions

Table 2 presents results from the univariate analysis. Findings show that 49% of farming households concurrently adopted both long-term and short-term SLM practices while 51% adopted only short-term or only long-term SLM practices. The mean age for of the primary farmers in surveyed households was 48.34 years. In the majority of households (69%), the primary farmer had basic education, whereas in 11 and 20% of households, the primary farmer had secondary education or higher and no education, respectively. The distribution of the education variable is consistent with national averages. For instance, nationally, 60 and 14% of the population has primary education and secondary education, respectively, while 26% has no education (Malawi National Statistical Office, 2012). More than two-thirds (71%) of respondents were married. 10% of households also reported having a chronically sick person. In terms of agricultural information sharing, 21% of households shared information on agricultural issues with other households in the community. In terms of wealth, 19 and 20% of the sample were in the poorer and richest wealth categories, respectively. The average active household labor size was 2.26 persons. In terms of food security (measured in months the household's food lasted after harvest) the average number of months after harvest food lasted was 8 months. The average plot size was 1.34 hectares compared to the national average agricultural landholding of 1.4 hectares (Malawi National Statistical Office, 2012).

Table 2. Sample characteristics (shown in percentages, otherwise noted)

Determinants of the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices at the bivariate level

Bivariate results of the determinants of the adoption of both short-term and long-term SLM practices are shown in Table 3. Our findings show noteworthy factors associated with the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices. In terms of plot-level and agricultural related factors, farm size and agricultural information sharing were significantly associated with the concurrent adoption of both long-term and short-term SLM practices. A unit increase in farm size was significantly associated with a 45% increase in the odds of simultaneously adopting both short-term and long-term SLM practices. Smallholder farming households who reported sharing agricultural information with other farmers in their locality were 2.09 times more likely to concurrently adopt both short-term and long-term SLM practices compared to those who never shared information with other farming households.

Table 3. Bivariate logistic regression analysis of the factors associated with the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices

OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

With regards to household capacity factors, household active labor size, having a chronically ill person in the household, wealth and social support were significantly associated with the adoption of both short-term and long-term SLM practices at the bivariate level. Compared to households with chronically sick persons, households that reported not having a chronically sick person were 2.61 times more likely to concurrently adopt short-term and long-term SLM practices. As wealth increased, the likelihood of simultaneously adopting short-term and long-term SLM practices increased. Compared to households in the poorest wealth category, those in the middle (OR = 3.01, p < 0.001), richer (OR = 3.14, p < 0.001) and richest (OR = 3.64, p < 0.001) wealth categories were all significantly more likely to adopt a combination of practices with short-term and long-term turnovers. A unit increase in household labor size was associated with a 29% chance of adopting a combination of short-term and long-term SLM practices. Smallholder farming households who reported always having support from other households in carrying out farming and other livelihood activities were significantly more likely (OR = 1.56, p < 0.05) to concurrently adopt short-term and long-term SLM practices compared to those who never have support.

In terms of household demographic and socioeconomic factors, age, gender and education of the primary farmer in the household, household food availability and women's autonomy were significantly associated with the adoption of both short-term and long-term SLM practices. A unit increase in age was significantly associated with 2% decrease in the odds of simultaneously adopting short-term and long-term SLM practices. Households with the primary farmer being female (OR = 0.54, p < 0.001) were also significantly less likely to concurrently adopt SLM practices with both short-term and long-term turnovers compared to households with the primary farmer being male. Compared to households with the primary farmer having no education, households with the primary farmer having basic (OR = 1.91, p < 0.001) and secondary or higher (OR = 3.05, p < 0.001) education were both significantly more likely to concurrently adopt SLM practices with short-term and long-term turnovers. A unit increase in the number of months food was available in the household after harvest predicted a 7% increase in the likelihood of concurrently adopting short-term and long-term SLM practices. Households in which women were autonomous (OR = 3.40, p < 0.001) were significantly more likely to simultaneously adopt short-term and long-term SLM practices compared to those in which the women were not.

Determinants of the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices at the multivariate level

Multivariate analysis of the determinants of the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices is shown in Table 4. Our findings show noteworthy factors associated with the combined adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices among smallholder farmers across ‘plot level’, ‘capacity’ and ‘demographic and socioeconomic’ factors. Consistent with the bivariate level, a unit increase in plot size was still significantly associated with increased odds of concurrently adopting short-term and long-term SLM practices. Although farming households that reported not using fertilizer were more likely to concurrently invest in both short-term and long-term SLM practices, the significance of the relationship was attenuated at the multivariate level. Consistent with the bivariate level, smallholder farming households that reported sharing farming information (OR = 2.50, p < 0.001) with other farming households in the locality were still significantly more likely to adopt short-term and long-term SLM practices concurrently.

Table 4. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of the factors associated with the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices

OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Household capacity related factors that were significantly associated with the combined adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices included the presence of a chronically sick person in the household, household wealth and active household labor size. The association between having no chronically sick person in the household and the simultaneously adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices at the bivariate level remained positive and statistically significant at the multivariate level. Farming households without chronically sick persons were 3.23 times more likely to adopt short-term and long-term practices compared to those with chronically sick persons. Consistent with the bivariate level, households in higher wealth categories were significantly more likely to adopt both short-term and long-term SLM practices compared to those in the poorest wealth category. A unit increase in active household labor size was also still significantly associated with increased odds of concurrently adopting both short-term and long-term SLM practices. It is however noteworthy that the significant association between social support and adoption of both short-term and long-term SLM practices was attenuated in the multivariate model.

Our findings also revealed some noteworthy factors associated with the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices across demographic and socioeconomic factors. Gender of the primary farmer remained significantly associated with the adoption of both short-term and long-term SLM practices. Households with the primary farmer being female still had significantly lower likelihood of concurrently adopting short-term and long-term SLM practices compared to households with the primary farmer being male. Compared to households with the respondent farmer having no education, households with the respondent farmer having primary (OR = 2.39, p < 0.001) and secondary of higher (OR = 2.97, p < 0.001) education were significantly more likely to adopt both short-term and long-term SLM practices. Consistent with the bivariate level, women's autonomy (OR = 3.28, p < 0.001) was also still significantly associated with increased odds of simultaneously adopting both short-term and long-term SLM practices, albeit with marginal reduction in the odds.

Discussion

In most countries in SSA including Malawi, investment in SLM remains low among smallholder farmers despite increasing land degradation (Mhango et al., Reference Mhango, Snapp and Phiri2013; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Steinfield, Chiwasa and Ganunga2019). The recent warning about the austere future implications of climate change and environmental degradation in the sub-region (IPBES, 2019) has engendered a renewed urgency for SLM. Although considerable research has gone into understanding farmers’ SLM adoption decisions, little is known about how the turnover duration of diverse SLM practices may shape their adoption by farmers. This gap is despite evidence that smallholder farmers tend to invest in SLM technologies that can bring immediate improvement to farming rather than practices like agroforestry that yield benefits in a relatively longer period. In this study, we examined the determinants of the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices. Our findings reveal several determinants across plot level, household capacity and socioeconomic characteristics of households.

Noteworthy among these determinants at the plot level is plot size. Land is central to the uptake of SLM. The literature on adoption has largely established a positive relationship between increasing farm size and the adoption of SLM practices in SSA with evidence suggesting that smallholder farmers with relatively larger farmlands have a higher tendency to invest in SLM (De Graaff et al., Reference De Graaff, Amsalu, Bodnar, Kessler, Posthumus and Tenge2008; Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Kessler and Hengsdijk2012; Teshome et al., Reference Teshome, de Graaff, Ritsema and Kassie2016; Ndagijimana et al., Reference Ndagijimana, Kessler and Asseldonk2019). While our findings are consistent with this observation, our analysis demonstrates that land size is important in shaping the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices as opposed to selective adoption. In the context of land scarcity, farming households may not prioritize long-term SLM practices like agroforestry and planting of vetiver grass, which compete for space with crops. Amid the growing pressure on agricultural land in Malawi, it is plausible that smallholder farmers who have relatively larger fields may be able to spare reasonable space for long-term SLM practices such as agroforestry while still using significant portions of the land for crop cultivation (Smith, Reference Smith2004; Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016). On the other hand, farming households cultivating relatively smaller plots may favor short-term SLM practices like mulching and composting which do not compete for space with crops (Amsalu and De Graaff, Reference Amsalu and De Graaff2007). Given that long-term SLM practices are likely to take more space on small plots, the benefits from adopting them alongside short-term practices may not be enough to compensate for reduction in productivity arising from the dedication of portions of farmland to these practices (Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016). The need to maximize space on farmlands becomes necessary given that most smallholder farmers in the study context also strive to cultivate multiple crops on the same land. Smallholder farming households in our study context who owned relatively smaller plots were often those growing different crop varieties, and this was mostly linked to the quest to diversify production as a risk spreading strategy while maximizing land utility. These findings demonstrate that land access dynamics are central to the simultaneous adoption of long-term and short-term SLM practices, for which reason policy attention must be placed on improving access to land and tenure security among smallholder farmers. Specific to the Malawian context, practical measures for ensuring access to adequate land and secure tenure for smallholder farmers should be prioritized in the ongoing land reform program of the Malawian government.

In terms of households’ capacity to invest in SLM, wealth, size of active household labor and presence of chronically ill persons in the household were significantly associated with the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices. The literature on SLM establishes a positive relationship between household wealth and SLM adoption, given the role wealth plays in improving access to inputs, labor and land for the uptake of various SLM practices (Kassie et al., Reference Kassie, Zikhali, Pender and Köhlin2010). Although short-term SLM practices such as composting, manuring and crop residue incorporation typically rely on household labor and other immediate household/locally available resources such as animal manure and waste, for which reason household income may not immediately impact their adoption, wealth may shape a household's ability to invest in long-term SLM practices like agroforestry and livestock integration which typically require capital for the purchasing of external inputs including seedlings and animals. Indeed, poorer farmers may be drawn towards investing in only short-term SLM practices in the quest to improve soil fertility and yield (Kristjanson et al., Reference Kristjanson, Neufeldt, Gassner, Mango, Kyazze, Desta and Thornton2012; Nkomoki et al., Reference Nkomoki, Bavorová and Banout2018).

There is empirical evidence of the positive impact of both education (Tiwari et al., Reference Tiwari, Sitaula, Nyborg and Paudel2008; Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Langan and Johnston2016) and farmer knowledge sharing (Misiko et al., Reference Misiko, Tittonell, Ramisch, Richards and Giller2008; Lukuyu et al., Reference Lukuyu, Place, Franzel and Kiptot2012; Franzel et al., Reference Franzel, Kiptot and Degrande2019) on the uptake of SLM practices. While our findings are consistent with the literature, they further suggest that increasing levels of education and farmer-to-farmer knowledge sharing may benefit the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices. In this context, education and farmer knowledge exchange may particularly benefit the uptake of long-term SLM practices, which are typically not prioritized by smallholder farmers. Indeed, most SLM practices with long-term turnover such as agroforestry are technical in nature and require some experience and knowledge sharing (Pender and Gebremedhin, Reference Pender and Gebremedhin2007; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Steinfield, Chiwasa and Ganunga2019). Farming households that share information with others in their locality would be better positioned to deal with the everyday practical challenges that accompany the application of SLM practices (Adimassu et al., Reference Adimassu, Kessler and Hengsdijk2012). These findings underscore the need for agricultural policy to promote farmer education and knowledge sharing. Farmer-to-farmer knowledge sharing is particularly crucial given the low public agricultural extension levels in rural areas across SSA. Also, the positive association between size of active household labor and the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices is consistent with the literature (Asrat et al., Reference Asrat, Belay and Hamito2004; Pender and Gebremedhin, Reference Pender and Gebremedhin2007; Teshome et al., Reference Teshome, de Graaff, Ritsema and Kassie2016). Given that both short-term and long-term SLM practices are labor-intensive (Kassie et al., Reference Kassie, Jaleta, Shiferaw, Mmbando and Mekuria2013), smallholder farming households with relatively higher labor capacity can invest more in their establishment and maintenance.

Gender was also significantly associated with the concurrent adoption short-term and long-term SLM practices. Generally, gender issues in SLM technology adoption manifest in the role gender relations and norms play in structuring differential access to productive resources including land and capital (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Steinfield, Chiwasa and Ganunga2019). Our findings demonstrate that households in which women were autonomous were three times more likely to concurrently adopt short-term and long-term SLM practices. The role of gender dynamics was also observed in the finding that households with the primary farmer being female were significantly less likely to adopt short-term and long-term SLM practices concurrently. These findings may be explained by contextual gender dynamics that limit women from participating in agriculture. For instance, in most parts of SSA including Malawi, evidence shows that women farmers tend to have relatively little control over productive resources such as land within the household due to unfavorable structural norms (Peters, Reference Peters2010; Me-Nsope and Larkins, Reference Me-Nsope and Larkins2016). In Malawi, the dominant system of land tenure is the communal system, in which households gain user rights to land through kinship structures—patrilineal in the north and matrilineal in the south. Even in matrilineal settings where land is passed down to females, there is evidence that these systems have evolved to the benefit of males in recent times (Peters, Reference Peters2010), with women mostly confined to smaller plots in marginal areas. This can negatively impact women farmers’ ability to contribute to the uptake of SLM technologies, especially given the positive relationship between plot size and SLM adoption (Kiptot and Franzel, Reference Kiptot and Franzel2012). Aside from not having enough access to land, tenure insecurity is also a major challenge for women farmers in Malawi (Lovo, Reference Lovo2016; Deininger et al., Reference Deininger, Xia and Holden2017, Reference Deininger, Xia and Holden2019). Empirical evidence suggest that farmers who do not have secure access to the land on which they cultivate tend not to invest in SLM practices with long-term turnover such as agroforestry due to fear of losing the land and the investment thereof (Gebremedhin and Swinton, Reference Gebremedhin and Swinton2003; Wannasai and Shrestha, Reference Wannasai and Shrestha2008; Fenske, Reference Fenske2011; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Holland and Naughton-Treves2014; Teshome et al., Reference Teshome, de Graaff, Ritsema and Kassie2016). Under the customary land tenure system of Malawi in particular, where tree ownership rights are mostly tied to land ownership (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Luckert, Minae and Place2005), women farmers who, due to customary provisions, do not have secure tenure, may not invest in agroforestry given the potential to lose rights to trees they planted. In a recent analysis of the low uptake of composting in Malawi, Cai et al. (Reference Cai, Steinfield, Chiwasa and Ganunga2019) also found that prevailing gender norms prohibited women from practicing certain acts including the climbing of trees, which are necessary in obtaining raw materials for implementing certain SLM practices.

While this paper presents interesting findings on some of the factors that may shape the adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices among smallholder farming households, there are limitations worth noting. First, due to data limitations, some key variables relevant to SLM, including field properties such as soil structure, elevation and distance from home as well as SLM implementation cost were not included in this analysis. Also, while it is important to understand the determinants of the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices among smallholder farmers, it is important to clarify that short-term and long-term practices may not be mutually exclusive. For instance, although practices such as composting and crop residue recycling tend to yield immediate benefits in a single planting season, they also have long-term benefits to soil health. Importantly, the sample for this analysis comprises only smallholder farming households who participated in a farmer-to-farmer agroecology project. Thus, the project activities and resources may have significantly shaped the socioeconomic characteristics and capacity of these households over time, with potential impact on their adoption behavior.

Conclusions

This paper examined the determinants of the concurrent adoption of short-term and long-term SLM practices among smallholder farmers in Malawi. The categorization of SLM practices based on turnover duration enabled us to add some insights to the literature on SLM adoption in smallholder farming contexts. Overall, our findings suggest that the decision to concurrently adopt short- term and long-term SLM practices is shaped by several factors that cut across the households’ capacity, plot level and socio-demographic factors. Thus, a one-size-fits-all approach may not be suitable in the design and deployment of SLM technologies in smallholder farming contexts. Initiatives targeted at promoting the holistic adoption of SLM—a combination of short-term and long-term practices—in smallholder farming contexts must therefore take into consideration the crucial role of underlying factors such as household wealth, land access, labor and women's empowerment concerns. Rather than treating smallholder farmers as a category with similar adoption behavior, paying attention to these dynamics can inform the design of policies targeted at ensuring the holistic adoption of SLM practices.