INTRODUCTION: IRONY AND THE FURIOSO

Irony has long been recognized as one of the defining characteristics of Ludovico Ariosto's (1474–1533) romance epic masterpiece, the Orlando furioso (first ed. 1516; second ed. 1521; third and definitive ed. 1532).Footnote 1 As Christian Rivoletti points out in his thorough study of irony in the Furioso and its reception during the Romantic period, the primary theoretician of the German Romantic movement, Friedrich Schlegel (1772–1829), identified the Furioso as the epitome of his modern, expanded conception of irony, understood not solely in rhetorical terms—as had been the case since Aristotle—but as an artistic and literary category, founded “on the relationship of communication existing between author and reader.”Footnote 2

Before this Romantic expansion of the term, irony had been conceived of as a rhetorical trope for embellishing discourse by expressing an idea through its opposite.Footnote 3 As Dilwyn Knox points out, irony was thought of primarily as aggressive or derisive in tone throughout the Middle Ages.Footnote 4 It is only during the Renaissance—thanks in particular to Petrarch's (1304–74) rediscovery of classical discussions of Socrates's use of irony—that a more gentle and witty conception of irony arose.Footnote 5 Implicit in even the more simplistic medieval understanding of irony is the notion that the reader must recognize and interpret an ironic statement or passage in order to understand it properly. In other words, as Wayne Booth formulates it, literary irony presents the reader with an invitation to interpretation: “Whenever a story, play, poem, or essay reveals what we accept as a fact and then contradicts it, we have only two possibilities. Either the author has been careless or he has presented us with an inescapable ironic invitation.”Footnote 6

Much of Ariosto's irony arises from his bemused detachment from his material and characters, owing in part to his belated arrival to the genre of medieval romance.Footnote 7 The narrator's shifting perspective resists identifying fully with his medieval characters or his contemporary readers, but rather chooses to stand apart from them, beholding from a critical distance the world he creates. It is precisely this mastery of the space between reality and its representation that the nineteenth-century Romantics appreciated as modern in Ariosto. The distance between the author and his material comes about as a function of the age in which he lived: a time during which long-standing notions of politics, society, religion, and chivalry were being shaken and upended. Ariosto occupies the same belated position with respect to the conventions of chivalric romance as he does with respect to traditional assumptions about the shape and contents of the world, which were rapidly passing into obsolescence, as a fuller picture of the new geography was being constructed.

In this study I identify a distinct target of irony in the Furioso, which has until now gone unidentified: geography. For all the commentaries and analyses carried out on the Furioso since its publication more than five hundred years ago, Ariosto's ironic treatment of geography has been essentially overlooked. To this point, when critics or commentators have identified clear contradictions in Ariosto's description of geography, they have either attempted to explain them away through contorted logic or dismissed them as mistakes or oversights. It is my contention that, in keeping with the tenor of the work as a whole, the Furioso invites its readers to pick up on these contradictions and interpret them ironically, just as it does with its better-known ironies. Interpretation of these geographic inconsistencies leads to a deeper understanding of the poem's relationship with the geographic and cartographic revolutions of the time, and a greater appreciation for Ariosto's incisive commentary on the intellectual crises of his age and the instability of the contemporary imago mundi.Footnote 8

Given that the Furioso's irony and its geographic intricacy have both been well documented as integral to the character of the poem, it is only natural to investigate points at which these two aspects converge.Footnote 9 For if irony functions essentially as a call to interpretation,Footnote 10 and space can serve a symbolic and functional role in narrative,Footnote 11 then it follows that irony and geography may work together to create meaning in the text. This study explores three key sites in the poem that are particularly rich in ironic geography—Ebuda, Alcina's island, and Astolfo's journey to East Africa and the moon—in order to discover how the text imbues geography with irony, and to demonstrate the heuristic possibilities that reading geography ironically makes available. These three locations have long been identified as sites of particular allegorical weight in the Furioso, where Ariosto implicitly remarks upon the profound upheavals of his age, and important scholarship has uncovered the darker side of Ariostan poetics by interpreting the rich symbolic and allegorical significance of Alcina's island, Astolfo's journey to the moon, and Ruggiero's voyage around the world, of which Ebuda is a part. This study is meant as a complement and extension of that fundamental work, aimed at highlighting the ways in which Ariosto makes the very landscape of his story world a vehicle for irony that speaks to the crisis in geographic knowledge of the period.Footnote 12

THE GEOGRAPHIC AND CARTOGRAPHIC REVOLUTIONS OF THE EARLY CINQUECENTO

Although there was significant continuity in mapmaking between the medieval and early modern periods, the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries witnessed transformational developments in the Western understanding of the size and shape of the globe, and in the production of maps. In the opening chapter of Cartography in the European Renaissance, David Woodward conducts an intriguing thought experiment by imagining what a cosmographer of the mid-1400s would have made of a standard world map produced only a century and a half later, in 1610. According to Woodward, the answer is astonishingly little, so much had our knowledge and conception of the world—and our conventions for representing it—changed in the intervening 150 years.Footnote 13 A seismic shift also took place in terms of the sheer scale of production. At the close of the manuscript era (ca. 1472) it is estimated that there were several thousand maps in circulation throughout Europe. By the end of the sixteenth century that number had risen into the millions.Footnote 14

The revolutions in geography and cartography are inextricably bound up with the recuperation of ancient works of geography and the age of discovery, both of which had profound effects on the worldview of early modern humanists. Within the course of several decades, beginning in earnest with Bartolomeu Dias's (1450–1500) rounding of the southern tip of Africa in 1488, the Ptolemaic conception of the world, which was the prevailing geographic model of the time, began to be not so much replaced as radically modified and expanded to account for the information brought back to the intellectual and cartographic centers of Europe from expeditions to Africa, Asia, and the Americas. As a result, the assumed size, shape, and content of the world were opened up for reinterpretation, throwing long-standing assumptions into doubt and disarray.Footnote 15

Although they played no direct part in the expeditions or colonial projects of the larger European powers, Ariosto's patrons, the Este family of Ferrara, maintained a keen interest in geography, amassing a considerable collection of books, maps, and correspondence relating the accounts of explorers’ travels—even engaging in international espionage and smuggling to secure the most up-to-date mapsFootnote 16—making Ferrara an important center for geographic and cartographic knowledge.Footnote 17 Ariosto's writings testify to the fact that he shared his patrons’ predilection for geography and cartography. The most direct evidence of the poet's interest in maps is an attestation to the fact in his “Satire 3,” in which he compares the enjoyment that some men take in striking out on adventurous journeys to his preference for staying home and exploring the world by map:

Men's appetites are various. The tonsure pleases one man, while the sword befits another. Some love their homeland, while others delight in foreign shores. / Let him wander who desires to wander. Let him see England, Hungary, France, and Spain. I am content to live in my native land. / I have seen Tuscany, Lombardy, and the Romagna, and the mountain range that divides Italy, and the one that locks her in, and both seas that wash her. / And that is quite enough for me. Without ever paying an innkeeper, I will go exploring the rest of the earth with Ptolemy, whether the world be at peace or else at war. / Without ever making vows when the heavens flash with lighting, I will go bounding over all the seas, more secure aboard my maps than aboard ships.Footnote 18

Here Ariosto enlists the ancient Greek geographer Ptolemy (100–170 CE) as a companion on his voyages of the imagination as he goes “bounding over all the seas” depicted on the maps of the Geographia, Ptolemy's authoritative work of geography.

It is also the narrative of the Furioso itself that testifies to Ariosto's deep interest in and knowledge of geography and cartography. As his dozens of characters race, wander, fly, and generally gallivant around the world, caught up in a constant play of centrifugal and centripetal forces with Paris at the center of the action, the poet employs an astounding degree of geographic precision in describing their journeys, far beyond what might be necessary to give the reader an idea of their trajectories.Footnote 19 For instance, in accompanying Astolfo in his voyage along the southern shores of Asia from Alcina's island to Egypt in canto 15, readers can draw the contours of the Asian coastline from east to west, as filtered through the early sixteenth-century Western imagination: the fifty-six-line itinerary of the voyage begins with Astolfo's departure from Alcina's island (more on this location further along), past the “rich and populous cities of fragrant Asia,” and “the thousand scattered islands” of the South China Sea and Maabar, north to the Malay Peninsula and west along “rich shores” to the mouth of the Ganges, through the Gulf of Mannar with Sri Lanka on one side and the Coromandel Coast on the other, further along the Indian shore to Cochin, and on to “the ends of India,” into the Persian Gulf where he disembarks along the western coast, through “numerous fields, woods, mountains and valleys,” across the Arabian Peninsula, to the Red Sea, and on to Pithom in Egypt, along Trajan's Canal to the Nile River.Footnote 20

This is just an example of the many meandering journeys undertaken by characters in the Furioso distinguished by a superabundance of toponymic specificity that serves to define the contours of the Furioso's story world. Such intricately delineated itineraries convert points within an isomorphic geospace into discrete places by pausing ever so briefly along the way to name a city or describe a coastline with an evocative adjective or two, drawing out the journey to give a panoramic sense of the world's vastness and variety through the use of exotic toponyms.Footnote 21 Yet none of these are invented: rather, all are drawn from a repertoire of literary and cartographic works. It is clear that, as Michele Vernero noted over a century ago, “the sum total of the Furioso's geographic details presents a correspondence to contemporaneous representations of geography that is anything but coincidental, but rather is such that makes it beyond doubt to my mind that the author kept an eye on his maps.”Footnote 22

Ariosto employed the same meticulous attention to cartographic detail in more explicitly fantastical journeys, such as Ruggiero's transcontinental flight on the magical hippogryph from Alcina's island to Ebuda in canto 10: a tour de force that guides the reader from east to west across the expanse of the Ptolemaic ecumene. Despite the utterly fabulous nature of the journey, all of the toponyms and demonyms that mark moments of pause along Ruggiero's route are found on maps of the era.Footnote 23 This piling up of almost two dozen locations along the way not only serves to fill in the shape of the Furioso's geography, converting space into place, but also sets up a moment of wry irony, when the narrator notes that despite Ruggiero's oft-stated desire to return as quickly as possible to his beloved Bradamante, he nevertheless indulges in the pleasure of travel to enjoy some sight-seeing along the way: “For all his pressing desire to return to Bradamante, Ruggiero was unwilling to forgo the pleasure of discovering the world . . . Days and months went by as he pursued his way, so eager was he to visit lands and seas.”Footnote 24

This admixture of geographic fact and narrative fiction both lends a degree of realism to the fantastical story and reflects the nature of cartography during this time of radical transformation of the imago mundi. The strategies adopted by the leading mapmakers of the age were both innovative and conservative: incorporating information regarding recent discoveries within a depiction of the world that still relied heavily on traditional authorities. This hybrid nature is reflected in the content of the maps of the period, which interweave fact with fiction, mathematical calculations with imaginative speculation, data from travelers and explorers with stories from myth and legend, and iconography of medieval provenance. A prime example of this eclectic approach to cartography is the Este's mid-fifteenth-century Carta Catalana, which features current data regarding the Portuguese exploration of the West African coast together with images and text depicting the location of the biblical Garden of Eden, the mythical kingdom of Prester John, and other material from ancient and medieval sources. Even a map that on the surface presents a more distinctly modern, scientific appearance like Martin Waldseemüller's Universalis Cosmographia from 1507, retains residue of ancient and medieval tradition.Footnote 25 The tenacity of past narrative becomes most apparent when one compares the map's depiction of Eastern Asia, with its long tradition of legendary lore, to that of the Americas, which had no such attending tradition in Europe. Waldseemüller is content to leave blank everything beyond the eastern coasts of the American continents, labeling it simply “terra ultra incognita”; whereas the horror vacui typical of mapmakers of earlier ages still encroaches on his treatment of East Asia, where he fills in empty space with medieval commentary, such as the Latin caption that accompanies the island of Angana near the extreme southeast corner of the map, which borrows nearly verbatim from Marco Polo's (1254–1324) account of the island's dog-headed and idolatrous inhabitants, or the text of a cartouche off the northern coast of Madagascar, describing an enormous sea monster that shines like the sun and has a form that defies description.Footnote 26

EBUDA / THE ISLE OF TEARS

In the Isle of Ebuda the Furioso presents an intriguing case of ancient geography put to ironic use, making this mysterious island the richest site of ironic geography in the entire poem. Ebuda is invested with an overdetermined ironic charge, as the author packs it with doubled-up signifiers, some of them in direct contradiction with one another.Footnote 27 The island's name, location, and the description of the events that take place there make it a locus of dense ironic geography, which calls out for interpretation.

Characters visit Ebuda several times during two separate incidents that unfold over cantos 8 through 11, in which knights arrive on the island and save women from the ravenous sea orc. The two occasions—the first involving Angelica and Ruggiero; the second, Olimpia and Orlando—constitute a redoubling that becomes a characteristic theme of this place. The first episode, that of Angelica and Ruggiero, is already featured in the first two editions of the poem (1516 and 1521), while that of Olimpia and Orlando makes its debut appearance in the third and definitive edition of the Furioso (1532). Rather than simply inserting the second episode into the story, Ariosto masterfully interlocks the two narratives by recounting Angelica and Ruggiero's story in cantos 8 and 10, and Olimpia and Orlando's story in cantos 9 and 11. This tight interweaving of the two episodes constitutes a prime example of the entrelacement that characterizes the macro-structure of the poem, formally binding the two accounts and inviting the reader to conceive of them as connected or as two seemingly identical versions of the same story that yield ironic contradictions when held up one against the other.Footnote 28

Typical of the accumulation of redundancies that mark ironic geography in Ariosto's poem is the island's name, or really names, since it is designated by two toponyms. In its first appearance in the poem (8.51), the island is called Ebuda. Here the narrator introduces the island, its location and inhabitants, and their gruesome custom of kidnapping virgins and chaining them naked to a boulder by the sea as sacrificial offerings to the horrid sea orc who visits their island daily to feast on human flesh. It is here that Angelica is brought by the Ebudans after they abduct her.Footnote 29 And despite the Ebudans’ pity for her, they carry out their grim ritual, binding Angelica to the rock. Her story is interrupted at this point, until canto 10, when Ruggiero, at the tail end of his world-spanning journey west from the realm of Alcina, flies over the island astride the hippogryph and serendipitously catches sight of Angelica chained to the seaside bolder: “He turned his steed south towards the sea that washes the Breton coast, and looking down, he espied Angelica chained to the bare rock. // Chained to the bare rock, she was, on the Isle of Tears—for [the Isle of Tears] was the name given to the island inhabited by those cruel savages, those barbarous folk who, as I related in a previous canto, went marauding along many a shore abducting every comely damsel in order to feed her infamously to a monster.”Footnote 30

Here the island is reintroduced with a set of redundancies that reinforce the doubling that characterizes this place. Not only is the island of Ebuda referred to by a completely different name, but this alternative name is preceded by a repetition—“to the bare rock. // To the bare rock” (“al nudo sasso. // Al nudo sasso”)—and then the new toponym itself is repeated—“to the Isle of Tears; // for the Isle of Tears” (all'Isola del pianto; / che l'Isola del pianto”) (a repetition not reported in Waldman's translation, above). When Ariosto sends the reader back to canto 8 with the parenthetical aide-mémoire “as I related in a previous canto,”Footnote 31 he makes abundantly clear, were there any lingering doubt, that the Isle of Tears and Ebuda are one and the same.Footnote 32

In the first two editions of the poem, Ariosto only refers to the island as “una Isola” or as “l'Isola del pianto.” It is in the third edition that Ariosto inserts the toponym Ebuda into the text in six different instances, five of which occur in the newly interpolated story of Olimpia and Orlando (9.11; 9.12; 11.28; 11.55; 11.60). Tellingly, however, the poet also inserts the name Ebuda into the introduction to the Angelica-Ruggiero episode in canto 8, mentioned above. Here Ariosto revises text which had already appeared in the first two editions, so that the location of the first episode is no longer referred to simply as an island, but is explicitly identified by name as Ebuda.Footnote 33 This particular emendation has the effect of reinforcing the stitching that binds the previously published episode of Angelica and Ruggiero on the Isle of Tears to the newly intercalated episode of Olimpia and Orlando on that same island, now also named Ebuda. However, rather than erase the name Isola del pianto and replace it in every instance with Ebuda, the author retains the former name, allowing it to exist alongside the new one, adding another layer of redundancy and flux to this already enigmatic place and destabilizing our conception of this island at the edge of the Furioso's story world. The fact that Ariosto retained the name Isle of Tears in the third edition when he added Ebuda demonstrates that the poet sought to augment the island's double nature in the final edition of the poem, where ambiguity and instability are more pronounced than in the first two editions.

While the name Isle of Tears is likely derived from the Chastiax de Plor that appears in the medieval Romance of Tristan,Footnote 34 the toponym Ebuda is clearly traceable to the ancient Greek geographic tradition, specifically Ptolemy.Footnote 35 After its reintroduction to the West in 1397 at Florence by the Greek monk Manuel Chrysoloras (ca. 1350–1415), Ptolemy's Geographia revolutionized geographic understanding and cartographic methods in the West, with its mathematical approach to cartography and its method of pinpointing locations on the earth's surface through the use of coordinates of latitude and longitude. Copies of the Geographia spread throughout Europe following its translation into Latin (completed ca. 1409 and published in print in 1475), allowing the text to disseminate widely in various languages and editions, to become one of the most successful printed books of the Renaissance.Footnote 36 The version of Ptolemy's text that was translated into Latin included no maps, but rather a description of his mathematical approach to geography and a gazetteer containing over eight thousand locations and their coordinates. Scholars later extrapolated these coordinates into maps, called projections, and precious versions of the translated manuscript were then copied and supplied with the illustrated projections. A particularly exquisite illustrated manuscript of Ptolemy's Geographia was acquired by the Este family in 1466, containing the seven books of the Geographia, plus an eighth book comprising richly illustrated cartographic projections of the locations listed in the first seven books. Ariosto clearly had access to Ptolemy's text, as he states in his “Satire 3,” and as evidenced by the fact that many of the place names that the poet sows throughout the text are traceable to the Geographia, and Ebuda is no exception.

Ptolemy ascribes the name Ebuda to an archipelago of five islands located off the northern coast of Ireland, at the northwestern edge of the ecumene. These islands are indicated on two maps in the Este manuscript: the initial planisphere map, which depicts the entire ecumeneFootnote 37; and the first table map, which portrays the British Isles and other nearby islands.Footnote 38 On the planisphere, the Insulae Ebudae are the most northwesterly objects on the map, residing to the north and northwest of Ireland, where they are depicted but left unnamed. On the first table map, which features the British Isles, the name Ebuda is ascribed to the two most westerly of six islands placed in the Oceanus Iperboreus to the northeast of Ireland.Footnote 39 Like the atlas's illustrator, Ariosto unmoors and multiplies the island from its fixed position on the earth, allowing it to drift around the northwest corner of the world, and making the island's wayward nature one of its key characteristics, a destabilizing contradiction that complicates our ability to place the island fixedly on the map of the Furioso's story world.

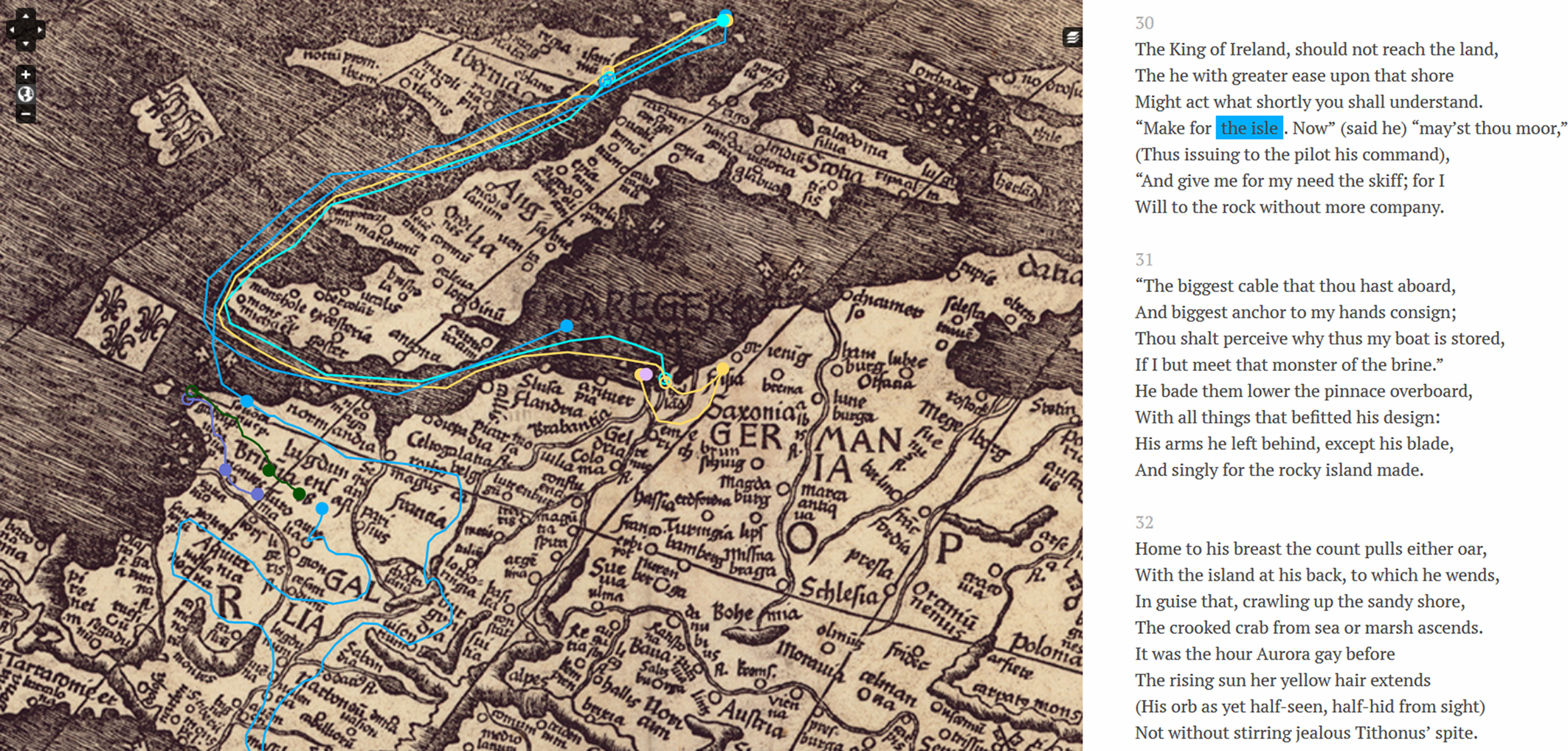

At the beginning of the Angelica episode in canto 8 the poem characterizes the island's position in language reminiscent of Ptolemy's description: “In the northern seas, over towards the setting sun, out beyond Ireland, there lies an island; its name is Ebuda.”Footnote 40 This is echoed in a similar description in canto 9 at the beginning of the Olimpia episode: “You must know that beyond Ireland there are many islands and one of them is Ebuda.”Footnote 41 This seems clear enough: the same island appears in both episodes, found in the same location at the extreme northwestern edge of the known world according to the Ptolemaic tradition, more or less consistent with the real world Hebrides. This makes sense as an evocative location for such a place: an isolated islet at the edge of the world, inhabited by a barbarous people and terrorized by a horrendous sea monster. Indeed, the entire episode of Olimpia and Orlando includes nothing that complicates this initial picture. After being jilted by her faithless lover and abandoned on an unnamed island somewhere in the open ocean near Scotland (10.16), Olimpia is kidnapped by the Ebudans, who bring her to their island and chain her to the seaside boulder. Orlando's route takes him from Dordrecht, Holland (9.61–87), out to sea where he casts Cimosco's infernal firearm into the depths (9.90), toward Ebuda (9.91), west through the English Channel, and north through the Irish Sea (9.93) to Ebuda (11.30) where he slays the orc, rescues Olimpia, accompanies her to Ireland, and then returns to France to continue his search for Angelica, disembarking at Saint-Malo (11.80). It seems clear, then, that readers should imagine Ebuda residing somewhere north of Ireland—“oltre l'Irlanda”—at the northwest edge of the world.

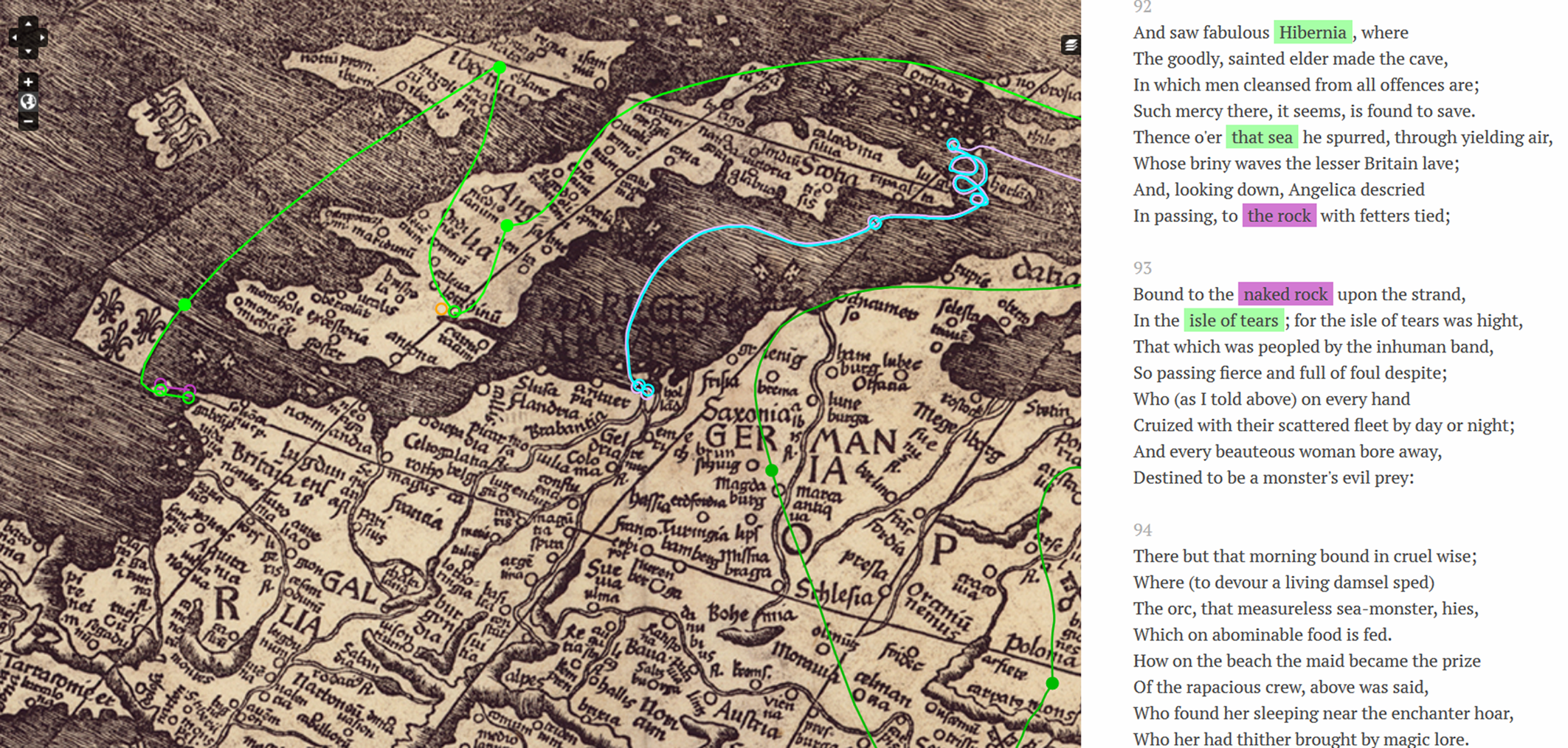

The complications arise when the geographic description of Ebuda in the Olimpia/Orlando episode is compared with its implied location in the Angelica/Ruggiero episode. The way in which Ruggiero unexpectedly arrives at the island contradicts everything previously stated regarding Ebuda's location. Astride the hippogryph, the Saracen knight sets out from London steering his course west toward Ireland: “At once he shaped his course toward Ireland, for he had seen Englishmen from all parts. // He beheld fabled Hibernia . . . After this he turned his steed south towards the sea that washes the Breton coast, and looking down, he espied Angelica chained to the bare rock.”Footnote 42

The plain sense of this passage is that after touring Ireland, Ruggiero heads south over the sea “which washes the lesser Brittany,” i.e., the portion of the Atlantic Ocean between southern Ireland and the Breton Peninsula that is now known as the Celtic Sea. This seems so obvious that Waldman inserts the directional adverb south into his translation (quoted above), while the word is not in the Italian original (a more literal translation of the Italian would read: “then he moves his horse over the sea / there where it washes the lesser Brittany”). It is here, south of Ireland, that Ruggiero spots Angelica tied to the boulder on the island (where she was last seen in canto 8). This southerly route is reinforced later in the canto when the narrator mentions that Ruggiero had intended to head from Ireland to Spain (10.113): a voyage which requires a journey to the south, surely not toward the north where Ebuda should be located based on the Ptolemaic worldview and on the descriptions in 8.51 and 9.12. Further evidence for Ebuda's new position south of Ireland is provided by the reiteration of the island's proximity to Brittany at the conclusion of the episode when Ruggiero and Angelica leave the Isle of Tears on the back of the hippogryph, and Ruggiero, in his haste to possess Angelica, lands precipitously on the nearby Breton coast: “Instead of circling Spain, as he had earlier planned, he put down at [the] neighbouring shore, where Brittany juts furthest out to sea.”Footnote 43

Suddenly, Ebuda is unequivocally situated south of Ireland, off the coast of Brittany, a position that is incompatible with earlier descriptions in the poem and with Ptolemy's positioning of the island. Although perhaps difficult to visualize, the discrepancy in position becomes obvious when the journeys of the various characters are charted on a map. This is the approach I took in my digital humanities project, the Orlando Furioso Atlas, where I constructed digital maps for each of the poem's cantos by tracing the characters’ travels on the Waldseemüller Universalis Cosmographia world map (1507),Footnote 44 which represents the most up-to-date geographic and cartographic knowledge at the time in which Ariosto was beginning to write his masterpiece.Footnote 45 A cursory glance at the map of canto 11, which contains Orlando's visit to Ebuda (fig. 1), alongside that of canto 10, which describes Ruggiero's visit (fig. 2), reveals the incongruity of the island's position in the two episodes.Footnote 46

Figure 1. Orlando's journey to Ebuda as described in canto 11, traced on the Waldseemüller world map of 1507. Orlando Furioso Atlas: http://furiosoatlas.com/project/neatline/fullscreen/canto-ix.

Figure 2. Ruggiero's journey to Ebuda as described in canto 10, traced on the Waldseemüller world map of 1507. Orlando Furioso Atlas: http://www.furiosoatlas.com/project/neatline/fullscreen/canto-x.

Most commentators have passed over this inconsistency in silence, while some have chalked up the aberration to a mere oversight, and still others have sought to force an alignment by imagining circuitous routes, which would take Ruggiero first north from Ireland, and then south. This theory was put forward by Vernero, who admitted that “certainly it requires a stretch”Footnote 47 to imagine that Ruggiero, intending to circumnavigate Spain, first headed north from Ireland to Ebuda, and then swerved south to land at Brittany. At any rate, this solution is invalidated by the fact that the text explicitly describes Brittany as the “neighboring shore” (“propinquo lito”) to Ebuda, which it would certainly not be if Ebuda were situated north of Ireland. Doroszlaï picks up on Vernero's hypothesis and attempts to rationalize it, but it still remains incongruent.Footnote 48

I see no reason to ignore this inconsistency, nor does it seem reasonable to ascribe it to an oversight by the author, who meticulously edited and reedited his text through three editions over the course of sixteen years, and whose attention to geographic detail is attested to throughout the text. A strong argument against the oversight theory is supported by the fact that the ambiguous nature of the island's location is already present in the first two editions of the poem, described in language almost identical to that of the final edition, both regarding Ebuda's collocation northwest of IrelandFootnote 49 and regarding its position off the coast of Brittany.Footnote 50 In other words, Ariosto would have had to fail to notice these glaring discrepancies through two painstaking revisions to his text and the complicated intercalation of the Olimpia-Orlando episode within that of Angelica and Ruggiero. This, I would argue, is very unlikely.

I would also venture a less cumbersome explanation than the Vernero-Doroszlaï hypothesis. A likelier and more elegant explanation, I believe, is that the author, perhaps picking up on the discrepancies in Ebuda's position on the two maps in the Este family's manuscript of Ptolemy's Geographia, intentionally displaced the island in his text in order to destabilize the reader's perception of the story world, in an act of ironic geography.

Here readers are faced with a contradiction in the text, which, as Booth indicated above, means that “either the author has been careless or he has presented us with an inescapable ironic invitation.”Footnote 51 Rather than simply rule out inattention on the part of the author out of deference to Ariosto, the rest of his text may be presented as evidence for an ironic invitation. To cite Booth once again, he states in his discussion of Voltaire's Candide as an epitome of the ironic literary text that “our best evidence of the intentions behind any sentence in Candide will be the whole of Candide,”Footnote 52 which is to say that the tenor of the text itself provides the strongest attestation for any individual instance of irony. The Furioso is redolent with irony, as has been well established, and so it follows that there is no necessary reason for the geography of the poem's story world to be free of irony; rather, it implies that it very well may be.

It is by considering Ebuda's wayward geographic drift as an instance of irony that its seemingly nonsensical shift in position suddenly makes sense. Ebuda's sudden and unexplained dislocation causes attentive readers to pause and question the stability of the imago mundi that they have been constructing from the text. I would contend that the text intentionally relocates the island in an ironic move that calls attention to the fractured Ptolemaic ecumene of the early sixteenth century. With a knowing wink to his readers, Ariosto here acknowledges the instability of the human conception of the globe—a worldview in flux—by allowing islands to float around the edge of what had been the accepted limits of the world for over a thousand years. This unraveling of a stable geography marks an intellectual crisis, which Ariosto expresses here through ironic geography. In its demand for readers’ reconsideration, irony insists that neither the world nor the meaning it contains is stable; rather all is in a continually fluid state of change, which no description can ever fully capture.Footnote 53 The ironic detachment typical of the author's attitude vis-à-vis his source material—in this case, the Ptolemaic geographic tradition—is here made manifest as a detachment of an island from the ocean floor.

In a poem in which the characters are constantly on the move, caught up in a whirlwind of ceaseless motion, at least the ground on which they stand should be stable, yet it is not. During Ariosto's lifetime, the edges of the Ptolemaic world were pushed and stretched ever further to the west, south, and east as the reports of the voyages undertaken by Columbus, Vespucci, da Gama, and others were disseminated through the intellectual centers of Europe, and this sudden malleability of a world assumed to be fixed in form is reflected in his depiction of this ironically errant piece of topography.

The irony created by Ariosto's exacting yet contradictory descriptions of Ebuda's position in his story world is figured in the episodes themselves. In retrospect, it seems that Ariosto signals his intention to throw his readers off course back in canto 8, where he states by way of introduction to Angelica's Ebudan adventure and the first description of Ebuda's location north of Ireland: “But before I tell you what happened, I must make a slight [detour from the straight path].”Footnote 54 The redundancy of the two nearly identical episodes creates the impression of a hall of mirrors, and the action of the episodes, when interpreted through the lens of ironic geography, reinforce the instability of the place.Footnote 55 Both episodes revolve around the barbarous Ebudans attempting to lash a woman to a boulder at the edge of the world, only to be defeated by a hypermobile knight, who releases the damsel from her captivity, granting her freedom of movement once again. In other words, the trajectory of both episodes takes us from enforced groundedness and fixedness to liberated flight and movement.Footnote 56

In allegorical terms, if binding a captive to a seaside bolder figures humankind's desperate attempts at nailing down and reifying a fixed image of the world, then the anchor that Orlando uses to heroically slay the sea orc can also be interpreted in an ironic key: rather than its canonical symbolic connotations of fixity and security, Ariosto's anchor triggers movement and instability. Orlando employs the anchor to interrupt the monotonous tyranny of tradition (the ceaseless daily sacrifice of young women to the sea orc), granting freedom of movement to the human captive. Indeed, in describing the mortal effect of Orlando's anchor upon the sea monster, Ariosto figuratively dislocates the orc, hoisting it out of its natural element by describing the predicament in which this terror of the seas finds itself with the terrestrial metaphor of the miner or sapper: “Orlando drove forward right into its jaws, bringing the anchor and, if I am not mistaken, the boat as well. He wedged the anchor between its palate and its soft tongue so that it could no longer bring its two fearsome jaws to shut together. Thus will a miner working at the rock face shore up the tunnel as he works forward, for fear it cave in suddenly and engulf him while, all unwary, he is absorbed in his labour.”Footnote 57 This incongruous image foreshadows Orlando's coup de grace, which is to drag the massive sea monster up onto land, thus displacing the beast geographically, swapping its nautical abode for a grave on the terra firma. Thus, not only does Ebuda / Isle of Tears occupy an unstable, shifting place on the map, but even the border between sea and land is shown to fluctuate.

L'ISOLA D'ALCINA

Explicitly linked to Ebuda / Isle of Tears is a second locus of ironic geography in the Furioso, which resides at the other extreme of the Eurasian continent: l'isola d'Alcina (Alcina's island). It is here that first Astolfo and then Ruggiero sojourn, falling prey to the seductions of the evil fairy Alcina, only to be rescued by the sorceress Melissa, and hastened back to Europe with the help of Alcina's sister, the good fairy Logistilla. Although located at opposite ends of the ecumene, Alcina's island and Ebuda are connected, representing the departure and arrival points, respectively, of Ruggiero's flight on the hippogryph. It is only fitting that Ariosto linked these two ironic realms of contradiction and ambiguity by such a chimerical creature: completely fantastical, and yet one that the narrator insists is real—“true and natural” (“vero e natural”) is how it is described when it first appears on the sceneFootnote 58—which becomes, according to Stefano Jossa, “protagonist of a play of mirrors between reality and literature that will lead it to introduce the space of the unknown, the unexplored, the possible.”Footnote 59

Astolfo is the first to arrive on Alcina's island. His misadventure begins in the work that constitutes the prequel, as it were, to the Furioso, Matteo Maria Boiardo's (1441–94) romance epic poem, the Orlando innamorato (1494). Ariosto then starts his poem more or less where the unfinished Innamorato leaves off, maintaining and adapting many of the same characters and plot lines as well as adding his own. In the Innamorato the English knight Astolfo is abducted by Alcina who carries him away from his companions on the back of an immense whale.Footnote 60 His fate is left hanging in the balance since Boiardo never managed to return to him, despite his intention to do so.Footnote 61 It is not until canto 6 of the Furioso, when Ruggiero arrives on Alcina's island, having been carried there against his will on the back of the supersonic hippogryph, that Astolfo fills us in on his fate subsequent to his kidnapping in the Innamorato. When Ruggiero alights on the island he discovers Astolfo transformed into a myrtle tree on the shore, and asks him how he came to be there. Astolfo launches into his tale, reiterating Boiardo's account of his abduction from the Innamorato, and then expanding upon it with Ariosto's continuation of the story. The repetition of the first part of Astolfo's adventure implicitly refers the reader back to the source material in the Innamorato, and it is in comparing Boiardo's and Ariosto's descriptions that the location of Alcina's island in the story world of the Furioso begins to lose stability.

According to Astolfo's recounting of his tale in the Furioso, he, Rinaldo, and some other companions had been working their way along a beach in northern Asia—“We were journeying Westward, along the dunes which endure the wrath of the North winds”Footnote 62—when they came upon a seaside castle, belonging to the fairy Alcina. There they see a beautiful woman, who turns out to be Alcina herself, standing on the shore and magically commanding fish to leap out of the water and onto the beach. Upon noticing Astolfo, Alcina is immediately smitten by him, and concocts a plan to abduct him. She invites the English paladin and his companions to swim out to a small island just off the coast where they can see a siren who has the power to calm the seas with her sweet voice. Astolfo, being the most impetuous of the knights, sets out immediately for the islet, despite the protests of his companions. Upon arrival he realizes that it is not an island at all, but rather an enormous whale under the magical command of Alcina. Before he can escape, Alcina arrives, and the whale swims away from the shore, carrying both of them out to sea.

It is at this point that Boiardo had interrupted the tale, and here that Ariosto picks up the threads and begins his elaboration, according to which Astolfo and Alcina ride for a day and a night on the back of the whale until they arrive at Alcina's island, which she shares with her sisters, the evil fairy Morgana and the good fairy Logistilla. As is her custom, Alcina seduces Astolfo, lulling him into a life of decadent pleasure, only to grow tired of him after a few months and transform him into a myrtle tree, in order to prevent him from escaping and warning others of her treachery. It is only then that Astolfo discovers that the island is littered with trees, fountains, and animals that were once her former lovers. Despite Astolfo's warnings, Ruggiero cannot resist Alcina's exceptional beauty or the luxurious trappings of her castle and gardens, and so he promptly falls under her spell and becomes her lover, leaving Astolfo in his imprisoned state on the beach. It is not until the sorceress Melissa arrives on the island that Alcina's hold on Ruggiero is broken, when Melissa reminds Ruggiero of his true love, Bradamante, and gives him a magical ring that allows him to see through all of Alcina's magic illusions. Ruggiero sneaks out of Alcina's palace, makes his way to the northern part of the island that is ruled by Alcina's sister, Logistilla, and with her help escapes the island and returns to Europe on the back of the hippogryph. Meanwhile, Melissa releases all the other hapless knights from their imprisonment, including Astolfo, who returns to Europe as well.

Boiardo provided scant detail in his description of Alcina's realm: “Alcina was Morgana's sister. / She dwelt with the Atarberies / Who lived up north beside a sea, / With no laws, wild and barbarous. / She'd built there, by her phantom art, / A garden with green trees and flowers / And a small castle, fair and noble, / Made out of marble top to bottom.”Footnote 63 This description raises as many questions as it answers. First of all, scholars remain puzzled as to who the Atarberies could be, since this demonym seems to be unique to Boiardo. Canova in his notes to the Innamorato identifies the Caspian Sea as the “mare, verso Tramontana” mentioned in the description, as does Bruscagli.Footnote 64 This seems consistent with the description of Rinaldo's departure from Alcina's castle after she absconds with Astolfo, which takes him through Tartary (a vague geographic term applied loosely to a vast area from the Caspian Sea across north-central Asia) to the River Don and on to Transylvania.Footnote 65

There is nothing particularly striking here, but when compared with descriptions in the Furioso, it becomes clear that Ariosto creates a series of ironic geographic contradictions in the text. The most confounding incongruity arises when considering the identity of Alcina's island, which has presented commentators with a scholarly crux. The main contender has been the island of Japan, known in the West after Marco Polo's Milione (ca. 1299) as Cimpagu, Cipangu, Zipangri, and other variations.Footnote 66 Others have suggested a Caribbean island,Footnote 67 or a purely imaginary place.Footnote 68 It is clear that Alcina's castle is no longer where Boiardo imagined it in north-central Asia;Footnote 69 however, the question of its new location has continued to vex, because Ariosto seems deliberately—and uncharacteristically—vague in his collocation of the place, leaving to readers the task of cobbling clues together in order to situate it within the space of the Furioso's story world.

In canto 6, Ruggiero and the hippogryph circle above Alcina's island and land on it after traveling a great distance “in a straight line and without ever turning.”Footnote 70 The “linea dritta” that the hippogryph follows is the Tropic of Cancer, which can be inferred from canto 4, when the winged horse sets out from the Pyrenees with Ruggiero on board: “he set course to where the sun sets when its circle lies in Cancer.”Footnote 71 This direct journey is confirmed later in canto 10 when the narrator reminds us that, “Coming hither, he had left Spain behind and made a direct line for India, where it is washed by the Eastern Sea.”Footnote 72 This brief description is followed by a longer depiction of the island, to which the generic attributes of a locus amoenus are ascribed.Footnote 73

Later in the canto, Astolfo delivers a topographic description of the island: bisected by a gulf on one side and an uninhabited mountain on the other, “similar to the mountain and the firth which separate England from Scotland”: possibly a subtle allusion to Ebuda.Footnote 74 Alcina rules the lower end of the island, while her sister Logistilla rules the upper part. When Ruggiero eventually frees himself from Alcina's grasp he makes his way north to Logistilla's castle, and then takes off on the hippogryph for Europe. Rather than retracing the journey that took him there, he decides to complete his circuit of the globe by heading west. When he takes off, the first toponyms the narrator names are Cathay, Mangiana, and Quinsai, all located, according to contemporary maps, in the eastern extremity of the Asian continent, implying that Alcina's island is located somewhere east of the Asian mainland at more or less the latitude of present-day China.Footnote 75

At first glance it seems logical, considering the indications Ariosto supplies and the maps of the era, to identify Alcina's island with Japan, which contemporary mapmakers placed directly on the Tropic of Cancer. However, there is a major problem with this identification. Ariosto rarely hesitates to employ specific toponyms to tell us exactly where his characters find themselves during major sequences. If Alcina's island is Japan, then why did he not say so? Zipangu still represented a sufficiently exotic locale to the early modern European reader to be suggestive of all manner of fantastical connotations, including vast riches and barbarous practices, so if Ariosto had wanted to conjure up these images in his readers’ minds, he likely would have simply told us that Alcina ruled over Japan.Footnote 76 The description of Alcina's island owes more to literary topoi, especially that of the locus amoenus, than to any real-world place.Footnote 77 It very well may be that Ariosto was inspired, at least in part, by Marco Polo's description of Zipangu (for example, one could see a model for the impossibly tall golden walls that surround Alcina's compound in Polo's description of the golden-clad palace of Japan's rulerFootnote 78), but that does not justify a wholesale identification of Alcina's island with Japan.Footnote 79

The displacement that Ariosto creates by dislocating Alcina's realm from Boiardo's collocation of it in north-central Asia, and then remaining vague about its location or identity, is only reinforced by the images of illusion and ambiguity that typify the place. This begins already in the Innamorato, where Astolfo and his companions had been fooled into thinking that Alcina's enchanted whale was an island,Footnote 80 a geographic misunderstanding that Ariosto has Astolfo reiterate, emphasizing the paladins’ error of perception and inability to accurately read the landscape.Footnote 81

The voyage to Alcina's island begins with an instance of geographic instability: an island that is not an island—a location that seems inert and static, but is in fact alive and mobile. This explicit ambiguity in Boiardo's narrative carries over to Ariosto's depiction of Alcina's island, which is implicitly ambiguous, since nothing there is what it seems (or even perhaps where it seems). The island, while occupying a discernible geographic location in the story world of the poem (perhaps coincident with real-world Japan, but not Japan itself) is an eminently literary construction, as the long list of source texts compiled by Rajna confirms (including biblical texts, ancient epic, medieval romance, even Dante, Boccaccio, and Poliziano):Footnote 82 a prototypical locus amoenus, which should be our first clue that something is ironically amiss, as it so often is in such idylls.Footnote 83

The theme of deceptive appearances begins straight away when Ruggiero lands on the shore and ties the hippogryph to a myrtle which turns out to be Astolfo transformed.Footnote 84 Later in the canto, the narrator goes so far as to remind his readers with a wink that they should beware of believing what they see here lest they fall with Ruggiero into Alcina's trap. In the couplet that closes the octave the narrator describes a golden gate flanked by columns of solid diamond: “whether they presented a true or false image to the eye, there was nothing like them for grace or felicity.”Footnote 85 This could well apply, too, to the hyperbolized portrait of Alcina's beauty, which takes up fully eight octaves overstuffed with every clichéd description of the beloved lady ever uttered by a Petrarchan lover, from her “long blond tresses” to her “small, rounded feet”; of course, each enchanting detail is mere illusion, since her beauty is the result of bewitchment masking her true appearance: that of an ugly old crone.Footnote 86

And yet, in contradiction to this warning, the narrator opens canto 7 by lamenting the fact that the unlettered masses are incredulous when confronted with accounts from far-off and unfamiliar lands, while only the educated few are wise enough to apprehend “the shining truth of my tale.”Footnote 87 The narrator often sets an ironic tone in the introduction to each canto, as he toys with the distance between the mythic past that he recounts and the real world in which he and his audience live. In the proem to canto 7, where much of the action on Alcina's island takes place, the narrator alludes to the hyperfictional nature of this episode with an ironic complaint about the skepticism of the ignorant and an equally ironic compliment of the wise for their willingness to believe tall tales:

He who travels far afield beholds things which lie beyond the bounds of belief; and when he returns to tell of them, he is not believed, but is dismissed as a liar, for the ignorant throng will refuse to accept his word, but needs must see with their own eyes, touch with their own hands. This being so, I realize that my words will gain scant credence where they outstrip the experience of my hearers. // Still, whatever degree of reliance is placed on my word, I shall not trouble myself about the ignorant and mindless rabble: I know that you, my sharp, clear-headed listeners, will see the shining truth of my tale. To convince you, and you alone, is all that I wish to strive for, the only reward I seek.Footnote 88

The irony here, of course, is that the narrator well knows that none of what he is relating is true, so that he pokes fun at his audience by creating an ironic contradiction by which his readers end up part of the ignorant and mindless rabble whether they believe him or not: credulous in belief, or ignorant in distrust. The emphasis here is on the difficulty of believing your senses, of ascertaining the truth of a story or of the world, which is the trap that both Astolfo and Ruggiero fall into when faced with the whale/island (Astolfo) and with the astonishing beauty of Alcina and her island (Astolfo and Ruggiero). The narrator couches this consideration of the inability to distinguish clearly between fact and fiction, nature and artifice, in terms of traveling far distances, calling into question the reliability of accounts from the edges, from far-flung peripheral places that are unfamiliar.Footnote 89

This is indeed the same story that maps of the time tell about the world, which, by the early sixteenth century, had reached a remarkable level of accuracy regarding the shape of the European continent, but still faded into vague and fanciful depictions of those lands about which much less was known in the West.Footnote 90 As Sara Belotti points out in her study of cartography in the age of Boiardo, even as the maps of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries were filling up with information about distant lands brought back to Europe by explorers, navigators, and merchants, cartographers continued to adorn unexplored areas with “information derived from ancient legends, like the presence of the earthly paradise or Noah's ark, or depictions of fantastic realms, such as Gog and Magog, or the kingdom of Prester John. At the same time, as the exploration and discovery of new lands advance, expanding the scope of the real world, imaginary places migrate ever further, remaining nonetheless cornerstones in the geographic imaginary.”Footnote 91 Just as mythic places are drifting to the margins of sixteenth-century maps, so do these two sites of irony in the Furioso's story world reside at the margins: the far northwestern (Ebuda) and far eastern (Alcina's island) edges of the expanded Ptolemaic ecumene that is Ariosto's field of play.Footnote 92 These two unstable places remain obscured by indeterminacy even as they are bordered by an overabundance of geographic specificity, like two mythic realms situated on either side of the real world of empirical history and knowable geography, a distinction ironic in itself, since, of course, the entire world of the Furioso is fictional. It is in the juxtaposition of overtly fictional and deceptively factual representations of the world that Ariosto leads the reader to consider the ambiguous distinction between the real and the imaginary. Here the irony of the geography not only acts in service of the larger allegory, but also points to the hollowness of cartographic pretentions to accurately portray the world, undermining any notion of a fixed or stable world image, and, as Samuel Beckett noted, “respect[ing] . . . the mobility and autonomy of the imagined.”Footnote 93

ASTOLFO IN AFRICA AND BEYOND

Alcina's island represents the point of departure for not one but two journeys that lead to remote loci of ironic geography, since both Ruggiero and Astolfo set out from Alcina's island only to end up in destinations marked by ironic geography: Ebuda in the case of Ruggiero; and East Africa in the case of Astolfo, launching pad for his journeys to hell, paradise, and the moon. If Ebuda represents the hazy western edge and Alcina's island the oblique eastern edge of the Furioso's story world, the southern extreme is occupied by sub-Saharan Africa.Footnote 94 Bridging these three sites is the figure of the hippogryph, occupying a space “squarely between the world of nature and that of poetic fantasy as a way of showing how equivocal are all meditations of imagination between the two.”Footnote 95 Connected by the hippogryph, the ambiguous geography of these three sites further problematizes any clear distinction between reality and imagination.

Although North Africa is well documented in the maps of the time (and indeed, the Furioso is replete with toponyms of this region from Ceuta to CairoFootnote 96), Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa are still shrouded in mystery for Europeans. And it is in this undefined imagined space that Ariosto sets another highly ironic episode, that of Astolfo's descent into hell, ascent to the earthly paradise, and voyage to the moon. This sequence marks a major turning point in the plot of the poem, since it is Astolfo who here manages to find Orlando's lost wits and return them to him, thus enabling the hapless knight to fulfill his role as Charlemagne's greatest paladin.Footnote 97 It is also a sequence rich in allegory and ironic literary echoes—namely of Dante's Comedy (1321), Leon Battista Alberti's “The Dream” (1440), and Lucian's “Icaromenippus” (ca. 160 CE).Footnote 98 What has not yet been noted is the fact that much of the irony is in fact geographic, arising from the ways in which Ariosto distorts the landscapes of his source texts as he borrows and adapts their geography and topography.

Ariosto infuses the sequence with irony at the outset, even before Astolfo's arrival at the entrance to hell. At this point in the narrative, Astolfo finds himself at the court of the mythical Senapo, ruler of the Christian realm of Nubia located in the vicinity of the Upper Nile. Senapo, also known as Prester John, is plagued by a host of ravenous harpies, and Astolfo graciously offers to rid the king of the nuisance. Using his enchanted horn, the paladin casts the harpies out of Senapo's palace and pursues them south astride the hippogryph: “Astolfo kept blowing his horn, and the harpies fled toward the torrid zone, till they reached the towering mountain where the Nile rises—if it rises anywhere.”Footnote 99

By slipping an insinuation of doubt into his geographic description at the conclusion of the octave, Ariosto mischievously calls into question his entire description of the scene, undermining his meticulous cataloguing of African locations and topography that distinguished Astolfo's journey to this point. Now it seems that not only the existence of Senapo's kingdom, but even the reality of the Nile River is thrown into doubt. What would it mean for the Nile to lack, of all things, a source? Here the poet once again calls into question our assumptions about the shape of his story world, and casts a particularly suspicious glance at sources, evoking in his readers’ minds the question of sources, perhaps including literary ones.

Astolfo's extraterrestrial journey begins at the foot of the mountain where he investigates, ever so briefly, an entrance to the underworld in an ironic parody of Dante's Inferno. Rather than explore the depths of the pit from top to bottom, as might be expected based on the Dantean precedent, Astolfo saunters in, listens to the rather long-winded tale of the first shade he encounters, then, without a reply, promptly turns around and beats a hasty retreat.Footnote 100 Once outside, the English knight mounts the hippogryph and swiftly flies from the base of the mountain to the summit where he discovers the Garden of Eden. Here the geography is once again Dantean in inspiration—recalling the earthly paradise located atop the mountain of purgatory—but is given an ironic twist when the arduous journey from the base of purgatory to the Edenic plateau that took Dante's pilgrim, heavy with sin, twenty-eight toilsome cantos to accomplish, is achieved by Astolfo and his flying horse in a single stanza. Rather than having to descend through the entire pit of hell, traverse the ghastly body of Lucifer, scramble through the narrow passage leading to the opposite side of the world, and trudge up the entire height of the mountain by foot, as Dante's pilgrim did, Astolfo merely jumps on his trusty steed and soars up the side of the mountain in the blink of an eye, the entrance to hell here conveniently located at the base of the same mountain that hosts the earthly paradise on its summit. This extreme compression of geographic space serves to ironically undercut the epic solemnity of the Dantean source text by deflating the epic dimension of Dante's journey from one supernatural realm to another.Footnote 101 By placing them so close together, the text also makes an ironic point about the proximity of these two apparently opposite spiritual states.Footnote 102

It is on the moon, however, that Ariosto creates a fully ironic landscape. Accompanied by his guide, Saint John the Evangelist, Ariosto takes off from the earthly paradise and flies to the moon, which he finds is about the size of the earth and made of steel. Like Lucian's Menippus, who makes a similar lunar journey, Astolfo is surprised to find that the earth appears tiny from the moon, its meager size compounded by its relative darkness, since it does not emit its own light. And as in the “Icaromenippus,” Astolfo's new vantage point on the moon deflates the size and importance of the earth, its topographical features now barely discernible on the surface of the small, dim globe: “the earth being unilluminated, its features can span but a short distance.”Footnote 103 This new perspective, rather than granting Astolfo a new perspective on life on earth, affords him but an obfuscated view of a dingy orb. How different this is from Dante's pilgrim's retrospective glance at the earth from the heaven of the fixed stars—a much greater distance than that of Astolfo from the moon—where, in addition to the insight he receives, he is able to discern every detail of the earth's terrain, from hills to river mouths.Footnote 104

After glancing down at the lackluster earth, Astolfo turns his eyes to the lunar landscape, describing it in contrast to terrestrial topography: “Other rivers, other lakes, other fields up there were not as they are down here. Other plains, other valleys, other mountains, that have their own cities and castles, with houses the like of which for sheer size the paladin had never seen before or since. And there were spacious, empty forests where nymphs were forever hunting game.”Footnote 105 In this brief description of the lunar terrain Ariosto presents a landscape that is simultaneously like and unlike that of the earth. It has all the same elements, but they are all other. Marsh suggests that the poet's repetition of the word other highlights the moon's role as a site of allegory.Footnote 106 It is an allegory, yes, and a particularly ironic one, as it is both like the earth and is its opposite. Not only is the moon bright, while the earth is gloomy, but whereas the earth in Ariosto's telling is the barren field of humanity's constant searching, striving and yearning, the moon, it turns out, is the repository of all those unattainable desires. This is made clear as Astolfo is led by Saint John into a valley littered with all the things that humans lose on earth. The list includes “tumid bladders,” which are ancient kingdoms and empires now long forgotten, “gold and silver hooks” (gifts given to kings and other patrons in hopes of royal favors), “garlands . . . which concealed a noose” (flattery), and “exploded crickets” (fawning poetry dedicated to patrons).Footnote 107 And of course, in addition to cities, castles, treasures, beauty, and charms, the largest pile of all is made of brains, the lost wits of countless people sealed in small flasks, among which Astolfo not only finds his own, but also those of Orlando.Footnote 108

Ariosto borrowed and elaborated this imagery from Leon Battista Alberti's “The Dream,” and as in Alberti's dialogue, Ariosto's lunar landscape is a supremely ironic terrain, made up of physical incarnations of immaterial wishes and desires. Taken together, these irretrievable objects of desire, all of which are bound to be lost on earth—love, empire, glory, fame, riches—represent a summa of the concerns of all the Furioso's characters. The very surface of the moon undermines the constant questing that motivates the action of the entire poem, proving that desire is folly and exposing as bankrupt the entire structure and enterprise of the romance genre. Even the fame of the elect few whose glory and deeds will outlive them needs to be rescued by magic swans from a feature of the moon's topography: the river Lethe. It turns out that all the effort expended by the Furioso's characters in traversing, exploring, cataloging every inch of the earth—from Ebuda to Alcina's island, from “the dunes which endure the wrath of the North winds” to the “torrid zone” of Africa—had been spent in vain, for they had been searching the wrong planet the entire time. As Zatti frames it, the allegory of the lunar episode forces the reader “to recognize and adopt an entirely relativistic principle, according to which earthly truths, earth's cognitive certainties, find in the new lunar perspective their overturning and contradiction. . . . Astolfo's investigation therefore becomes the authentic exploration of the universe of ‘non-correspondence’ in which the dissonances of the sublunary world are reflected as in a mirror.”Footnote 109 The lunar landscape is not only the stage for this ironic upending, but is itself the ironic mirror image of the earth. And as is the case with Ebuda and Alcina's island, this non-correspondence to common expectations is inscribed in geography.

CONCLUSION

As the Furioso comes to a close, the opening image of the final canto is that of a ship's navigator consulting his maps in order to find his way back to shore: “Now if my chart tells me true, the harbour will soon be in sight and I may hope to fulfill my vow ashore to One who has accompanied me on so long a voyage. Oh, how I had paled at the prospect of returning with but a crippled ship, or perhaps of wondering forever! But I think I see . . . yes, I do see land, I see the welcoming shore.”Footnote 110

Even as the narrator looks expectantly toward his destination, his hopes are still couched in doubt: “Now if my chart tells me true”; “I may hope to fulfill my vow ashore”; “But I think I see.” The narrator is not yet certain if he should fully trust his maps—or maybe even his poem, since carta can mean both map and poem Footnote 111—even at this advanced stage in the narrative, perhaps because of the ambiguity and instability of the Furioso's story world that he has come to know along the way. Indeed, it is with a palpable sense of relief that the narrator sights land, incredulous that he has actually made it to his destination.

Rather than state outright that the image of the world created by the text—and all the images of the world that humankind has created—is unstable, imperfect, unmoored, and hybrid (based on at least as much imagination as fact), readers are led to this understanding by decoding contradictions that can only be understood as ironic invitations to interpretation. At the outer reaches of the ecumene, precisely where the decisively drawn lines of the Ptolemaic projections had remained firmly in place until a decade prior, when they began to be pushed back and away, along the hazy frontier between pragmatic and mythic space—those “fuzzy areas of defective knowledge surrounding the empirically known”Footnote 112—it is here that the poet collocates these loci of geographic contradiction, instability, and irony. Ebuda / Isle of Tears, Alcina's island, and East Africa demarcate not only the edges of the presumably knowable Ptolemaic globe, but also the most unstable zones of the world as reports from abroad reshaped Europeans’ conception of the contours of the earth's surface.

Undoubtedly, Carolingian Paris sits firmly at the center of the Furioso's story world—its bridges, walls, palaces, and churches drawn in bold and solid lines—where it exerts a constant gravitational pull on all the characters, as Charlemagne, Agramante, and Marsilio repeatedly implore their paladins to return and help them in their bitter battle for control of the Frankish Empire. At the same time, the outer reaches of the world exert their own fascination on the poem's characters, setting up the constant push and pull of centrifugal (the call of duty) and centripetal (the allure of adventure and pleasure) forces that keep the poem's characters in constant motion. At the world's margins the apparent solidity and firmness of the imago mundi give way to the shifting sands of a worldview in flux, denying with an ironic smile our cartographic desire to fix it in place.

In his recently translated work, Blinding Polyphemus: Geography and the Models of the World, Franco Farinelli recounts the accusation leveled against the pre-Socratic philosopher Anaximander, the author of the first world map. Farinelli states that Anaximander's contemporaries supposedly chastised him for the hubristic act of drawing the earth and seas from above, a point of view reserved for the gods alone. However, the real reason for their disapproval was another: “with his drawing, Anaximander had paralyzed and thus killed something (physis, nature) that is instead in continual growth and movement. It is the ‘genesis of growing things,’ as Aristotle also notes, a dynamic process and not its inert result.”Footnote 113 Through the introduction of irony in the description of the geography of his story world, Ariosto effectively reverses Anaximander's petrification of the world image, breathing life back into it, reanimating it, and laying bare the inevitable inadequacy and falsehood of all static depictions of the world.