INTRODUCTION

On Thursday, 6 April 1606, around midnight, nineteen eminent citizens gathered at the local church of Santa Maria del Carmine, in Florence, to see and touch the corpse of a man who had died 232 years earlier.Footnote 1 After two centuries at rest, the remains of Bishop Andrea Corsini (1306–74) should have been in an advanced state of decay.Footnote 2 Yet the witnesses noticed with wonder that the corpse, intact, had retained a skin so flexible, soft, and colorful that it was as if it was still alive. Among the witnesses, the doctor Angelus Bonellus, an experienced physician, was entrusted with the physical examination of the cadaver.Footnote 3 After scrutinizing the surface, he decided to open the corpse and perform an autopsy. He explored the bodily insides, searching for earlier traces of embalming, trying to understand the causes of such a remarkable state of preservation. He saw that Corsini had been eviscerated after his death, as was customary in Italian funerary rituals, but he had not, however, been embalmed, as no traces of preservatives could be found. Unable to find a medical explanation for the extraordinary conservation of the body, the physician wrote in the notarized record of his examination that the incorruption of the bishop, clearly “beyond [the boundaries of] Nature,”Footnote 4 was miraculous—a conclusion he could only draw because, he said, “I, Angelus Bonellus, Florentine, examined by seeing, touching, and smelling [Corsini's] body.”Footnote 5

At the end of the official record of the postmortem, the eighteen other witnesses officially testified that they had attended the visitation of the now presumed holy body. Among them were the city general inquisitor; two senators, including Lorenzo Guiccardini; a surgeon; the rector from the Society of Jesus College; and several important ecclesiastical officials. They all signed the notarized relation written by Bonellus and stated that they were present and had seen the body intact, and they attested to the veracity of the physician's report. Of great interest to this article is that, in addition to confirming that they had seen the dissection, eleven witnesses considered it noteworthy to write that they had touched the cadaver on display: “vidi et tetigi,” wrote those that testified in Latin; “visto e tocco,” wrote those who used their native vernacular language: “I saw and I touched,” some even adding, “with my own hand” (“con mano propria”).Footnote 6

This list of signatures covers four manuscript pages of Andrea Corsini's canonization process, held by the Archivio Apostolico Vaticano. As I went through the records of the bishop's postmortem, I was struck by the repetition of this almost formulaic “vidi et tetigi” in an official document established by the Counter-Reformation Church. That eighteen people gathered in the middle of the night to attend a dissection might perhaps seem odd by contemporary standards, but it was common practice in the early modern period, as is well known from the vast body of literature on Renaissance anatomy.Footnote 7 From the fourteenth century onward, cadavers were routinely opened in Northern and Central Italy. In addition to holy autopsies, there were public and, more frequently, private dissections being held in medical schools; judicial and domestic autopsies performed in cases of suspicious deaths; caesarean sections; and embalming practices in elite funerary rituals. Witnesses were present at most of the recorded dissections, although not always as clearly identified as in Corsini's postmortem. The presence of witnesses was vital to the production of knowledge and to the establishment of truth in the early modern period—a fact discussed extensively by scholars since Shapin and Schaffer's Reference Shapin and Schaffer1985 Leviathan and the Air-Pump.Footnote 8 What is more intriguing, in Corsini's case is that witnesses would not only watch but also touch the corpse, and record that they had done so in official legal documents issued by central ecclesiastical authorities. Corsini was not an isolated case. The Archivio Apostolico Vaticano holds several documented cases of witnesses testifying to having touched dissected dead bodies considered for canonization, including those of Ignace of Loyola, Teresa of Avila, Luis Bertràn, Isabel of Portugal, and Giacomo della Marca, to name but a few.

The aim of this article is to shed light on these practices and to uncover the ways in which, and the reasons why, early modern men and women were touching dissected corpses. Building on the rich scholarship from the history of medicine, science, and technology, which in recent decades has uncovered the significance of practice and experience in knowledge production, I investigate, more specifically, the importance of touch in empirical knowledge making. Studies have questioned the relationship between the body and the “body of knowledge.”Footnote 9 Yet, while extensive research has been undertaken on the part played by visual culture and observation in the rise of experimental sciences in the early modern period, the sources, practices, and epistemologies of touch are yet to receive the same level of scrutiny.Footnote 10 A focus on the knowledge practices of touch is particularly useful, as touch, theorized in natural philosophy as a bodily sense of contact since Aristotle's widely disseminated work on the senses, De anima (On the soul), encapsulates sensory and bodily experience of the world in a much more intimate and material way than sight does.Footnote 11 This is especially salient since touch is a relational sense: the act of touching necessarily entails to be touched in return, which transforms both the person touching and the object/person that is touched. This makes touch a particularly complex and ambiguous sense in relation to knowledge making.

While previous studies on touch have either tried to capture the actual sensory experience of the past or to examine metaphors, allegories, and theories of touch displayed in early modern writings through rich histories of literature or ideas,Footnote 12 this article starts with practices, and examines a specific type of physical encounter, one that is particularly striking because of its extreme nature—touching dissected corpses. It then further examines the link between bodily practices and epistemologies in the early modern study of nature. My aim is not just to describe haptic practices and epistemologies (Greek ἅπτομαι [haptomai]: to touch) but also to explore the broader context in which they were implemented and the reasons that justified the performance and recording of specific haptic events, epitomized by the expression et tetigi.

Moreover, touch needs to be considered in its multiplicity. Unlike the other senses, which have a localized organ (the nose for smell, the eye for sight) and hence a more clearly circumscribed perception, touch is ubiquitous, as tactile receptors are spread throughout the body. Although most often embodied in the hand, touch is also associated with skin, flesh, movement, the reproductive organs, and even the entire body. It is the sense of pain and pleasure, of temperature, pressure, and texture, of interoception and proprioception.Footnote 13 As outlined by Pablo Maurette, it is “the external, epidermal sensation of the outside world and also the intimate experience of our inner body.”Footnote 14 Exploring touch within the broader framework of the haptic is a productive way to build on its multiplicity and apprehend touch not as one but many senses, encompassing a diverse range of experiences.Footnote 15 The haptic, moreover, requires “an active movement of the hand, so that the sensory information a person receives does not come just from passive contact but from actively exploring the environment,”Footnote 16 which was the case in the forms of touch involved in anatomical practices that are examined here. These are the reasons why I propose to refer here to the haptic rather than to the tactile, building on previous research on touch from Maurette and Mark Paterson. In addition to stressing the plasticity of the concept, Maurette convincingly argues that using the more recent and less familiar word haptic creates “estrangement,” thus providing “the distancing needed” to explore past sensory worlds.Footnote 17

The first two sections of the article examine the religious and medical-historical meanings of the expression vidi et tetigi, building on extensive research from historians of medicine and religion, who have revealed the intersection between religious edification and medical expertise in the early modern period.Footnote 18 The later sections then uncover the haptic epistemologies at play in physical encounters with dissected corpses. After examining the variety of ways open corpses could be touched by medical experts, on the one hand, and nonmedical witnesses, on the other, I look at the ways in which haptic experience was framed in dissection records. I show that the sources documenting holy autopsies cast medical practitioners as haptic experts who were able to assess, fully describe, and interpret the qualities of the bodies of presumed saints, an experience seen as a necessary prerequisite to the determination of incorruption. This expertise consisted not only in performing technical gestures that involved an experienced ars of the hand (encapsulated by the skilled medical art of cutting), but also in the ability to feel and act upon matter—to discern the nuances of textures and material substances through an embodied experience of living and dead bodies. I propose that touch lay at the heart of the understanding of medicine and religion in the early modern period, a time largely recognized to have transformed people's understanding and experience of visuality in the sciences and the arts.

“DALLA MANO DE DIO”

As shown by Katharine Park in her foundational work about the anatomy of female bodies in late medieval and Renaissance Italy, dissections first emerged from the practice of embalming by evisceration, where bodies of holy nuns were cut open, often by women, for the purpose of preserving their relics.Footnote 19 From the first documented case of Chiara of Montefalco's postmortem in 1308 until the mid-sixteenth century, what Park calls “holy autopsies” or “holy anatomies” exclusively involved female saints.Footnote 20 With the development of papal bureaucracy and the formalization of canonization processes in the Counter-Reformation, the number of autopsies, now frequently led by university-educated physicians who would cut open both male and female saints, grew exponentially from the late sixteenth century onward.Footnote 21 Doctors were appointed by the church as experts because they were able to provide material evidence of miracles, thus turning “miracles from objects of faith into objects of knowledge.”Footnote 22 For medical experts, conversely, holy autopsies performed for the church became an opportunity for professional development and social recognition.

Corsini's case is particularly striking as it was one of the first cases in which medical practitioners were convened as experts and in which the autopsy record was included as a key element in the process that would ultimately lead to his canonization.Footnote 23 The determination of incorruption was central to his physical examination.Footnote 24 Although the social, religious, and political justifications for such a postmortem have been outlined by previous research, the reasons why eleven witnesses testified to having touched his corpse are still unclear.

Naturally, since the aim of the procedure was to search for signs of sanctity, the first idea that comes to mind is that the witnesses touched Corsini for the same reason they would have touched any other saint's relics: the thaumaturgic powers of holy remains. Since the sanctity of Bishop Corsini was attested by medicine—although it took a few more years to receive official confirmation from the Vatican, in 1629—touching his miraculous remains would have represented a powerful experience of devotion. Among the eleven witnesses who wrote that they had touched the corpse were six religious figures. The first witness to write that he had seen and touched the body (vidi et tetigi) was the Inquisitor General of Florence, followed by the rector of the college of the Society of Jesus, an archdeacon, a brother Augustine, a Mendicant monk, and a prior.Footnote 25 The religious witnesses were not the only ones, however, to use the expression vidi et tetigi, since the two Florentine senators and three other lay witnesses also adopted the formula, as well as the physician in charge of the autopsy and author of the dissection record. The desire of the witnesses to touch the body that was considered holy conjures up images that evoke the long historical fascination for relics that led crowds of pilgrims to touch corpses and to tear bodily parts and pieces of clothing in the hope of benefiting from the protection of their miraculous nature.Footnote 26 Relics, “believed to contain physical traces as well as the imprint of Christ's body,” were thought to allow communication with the divine, which frequently passed through the sense of touch.Footnote 27

The phenomenon is especially revealing in the case of Corsini, as he was already known as a thaumaturge during his lifetime. His cadaver was considered to have retained this healing power, as evidenced by the fact that his relics were distributed throughout the city by the Carmelites to be touched by incurable patients.Footnote 28 Miraculous healings make up the bulk of the 62 miracles attributed to the bishop of Fiesole and described by the 114 witnesses of his canonization process. Corsini was not an isolated case. The great majority of the miracles attributed to candidates for holiness in the canonization processes, both during their lifetimes and after their deaths, were indeed healing miracles, inspired by the stories of miracles described in the Gospels.Footnote 29 Touching, embracing, and eating the relics of a saint made it possible to establish a connection with them in order to solicit their intercession, ideally by bringing the suffering part into contact with the holy remains. The sick, cured by contact with a sacred body, “acting as a channel of divine power,”Footnote 30 were considered to have been directly touched by the hand of God, as can be seen from the testimonies of the trial of Angelo del Pas, who died in 1596 and whose hand was widely acknowledged as a “divine hand”Footnote 31 that cured all infirmities: “He had this grace from God in the palm of his hand, which he touched upon the heart of the sick.”Footnote 32 Likewise, the preservation of holy bodies was seen as an extraordinary act performed “by God's hand” (“dalla mano de Dio”), as evidenced in the record of Filippo Neri's postmortem.Footnote 33

Touch was thus a key sense in spiritual encounters with reputed holy bodies, where it acted as a mediator between the hand of God, the hand of his holy intercessors, and the suffering bodies of humans on earth. This form of touch, the touch of God, highlights the relational dimension of touch: not only does touch entail a reciprocal contact between the object and subject of sensation, it also connects natural and supernatural worlds, revealing the porosity of bodies as much as of the frontiers between the visible and the invisible.

Holy remains, moreover, were believed to be of a different nature than ordinary corpses, as evidenced by both internal and external signs.Footnote 34 A corpse decomposes, whereas a relic is a powerful spiritual entity (virtus) that retains a part of the person it incarnates; it escapes putrefaction and smells good. There is, therefore, no disgust in approaching, touching, kissing, or ingesting a relic because the body is reputed to be alive.Footnote 35 As Gianna Pomata has shown in her study of the holy autopsy of Caterina Virgi (Saint Catherine of Bologna), the medical witnesses present during the visitation of the remains were experiencing a “double vision—a disconcerting mix of corporeal and spiritual seeing,” and facing a “double object of knowledge”: on the one hand, they saw a corpse, on the other hand, “the possibility of a supernatural presence.”Footnote 36 Marcello Malpighi, who was present as an expert in the canonization process, qualified Caterina's corpse as “an ‘adumbration’ of immortality: a ‘beautiful and precious relic’ that offered a glimpse of the perfect incorruptibility that the bodies of the blessed would achieve in paradise.”Footnote 37 Pomata explains that when they were interrogated in 1669–74, several witnesses of the canonization process declared that they had “not only seen but touched Caterina's body, with awe-struck devotion mixed with an inquisitiveness that they themselves ‘spiritual curiosity’ [coriosità spirituale].”Footnote 38

Similar testimonies pervade most witness records from canonization processes, including those written by university-trained physicians, who, just like their lay contemporaries, were men of their time and sought to have tangible contacts with the divine. Acting as a permanent backdrop during holy autopsies, the touch of God was a constant presence in the mind of the witnesses called in to put their hands on and inside the bodies of presumed saints. Corsini's dissection, therefore, meant much more to the participants than usual autopsies did to practicing physicians.

However, the spiritual power of mortal remains is only part of the answer, as the following sections of this article will uncover. I will now scrutinize the genesis of the expression that lies at the core of this research: vidi et tetigi. Tracing the uses of this expression will lead me to examine more specifically the medical side of the story.

VIDI ET TETIGI

Weber and Maurette consider the formula vidi et tetigi as epitomizing the new anatomical method fostered by medical practitioners who praised sensory experience of dissections and practical skills in medicine (peritia) that flourished in late fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italy.Footnote 39 These doctors promoted a program of sensory anatomy of the human body that relied on sight and touch, as evidenced in Berengario da Carpi's (d. 1530) sensory-based assertions (“So it is according to the sense”Footnote 40) and Niccolò Massa's (1485–1569) “sensat[a] anatomi[a].”Footnote 41 The anatomists that promoted this method claimed that after reading medical authorities such as Galen, Aristotle, and Hippocrates, medical practitioners needed to see and touch the body.Footnote 42 Andreas Vesalius (1514–64) is an emblematic figure of this movement that started decades before De Humani Corporis Fabrica (The fabric of the human body) was published in 1543. In the anatomical textbooks that promoted this method, sight and touch became the warrants of the sensory truth of nature and of the authenticity of the narrative reported. Like the witnesses in the opening story, these medical practitioners were quick to highlight their personal experiences of dissection and would readily use the first-person singular in their writings to convey this idea.

However, if the idea of hands and eyes fostering anatomical knowledge was widespread among these practitioners, the expression vidi et tetigi was not so commonly used. Vidi and other words referring to visual experiences were far more frequent, confirming the prevalence of vision in Renaissance anatomy, which has long been established by the very rich scholarship on the subject.Footnote 43 Interestingly, the word vidi is accompanied by et tetigi when it is used by writers who explicitly state that they are dissecting with their own hands, as was the case for Carpi and Massa, but also Antonio Benivieni (1443–1502), Realdo Colombo (1510–59), Gabriele Falloppia (1523–62), and, of course, Vesalius. As historians of Renaissance medicine have shown, physicians who held the university chair of anatomy were not necessarily all dissecting with their own hands. Since the late Middle Ages, tasks were divided among the lector (a university-educated physician who lectured on ancient authorities); the demonstrator, or ostensor (who showed the parts that were being discussed by the lector on the corpse); and the sector, or prosector (a barber-surgeon or a medical student who was responsible for performing all the manual procedures).Footnote 44 This work division, compellingly described by Rafael Mandressi as a “hierarchy of touch,”Footnote 45 was tied to the traditional discrimination against the dirty hands of artisans working within the mechanical arts. The greater the distance from the corpse, the higher the status; only low-ranking, manual workers were touching organic matter. This anatomical model was famously condemned by Vesalius, who argued that the true anatomist had to embrace all three tasks (lecturing, showing, and cutting) in order to achieve a true understanding of human anatomy. This claim was powerfully displayed on the frontispiece of De Humani Corporis Fabrica and in Vesalius's portrait at the beginning of his landmark publication, where he is pictured dissecting an arm, a powerful symbolic representation that placed the sense of touch at the center of the anatomical project.Footnote 46

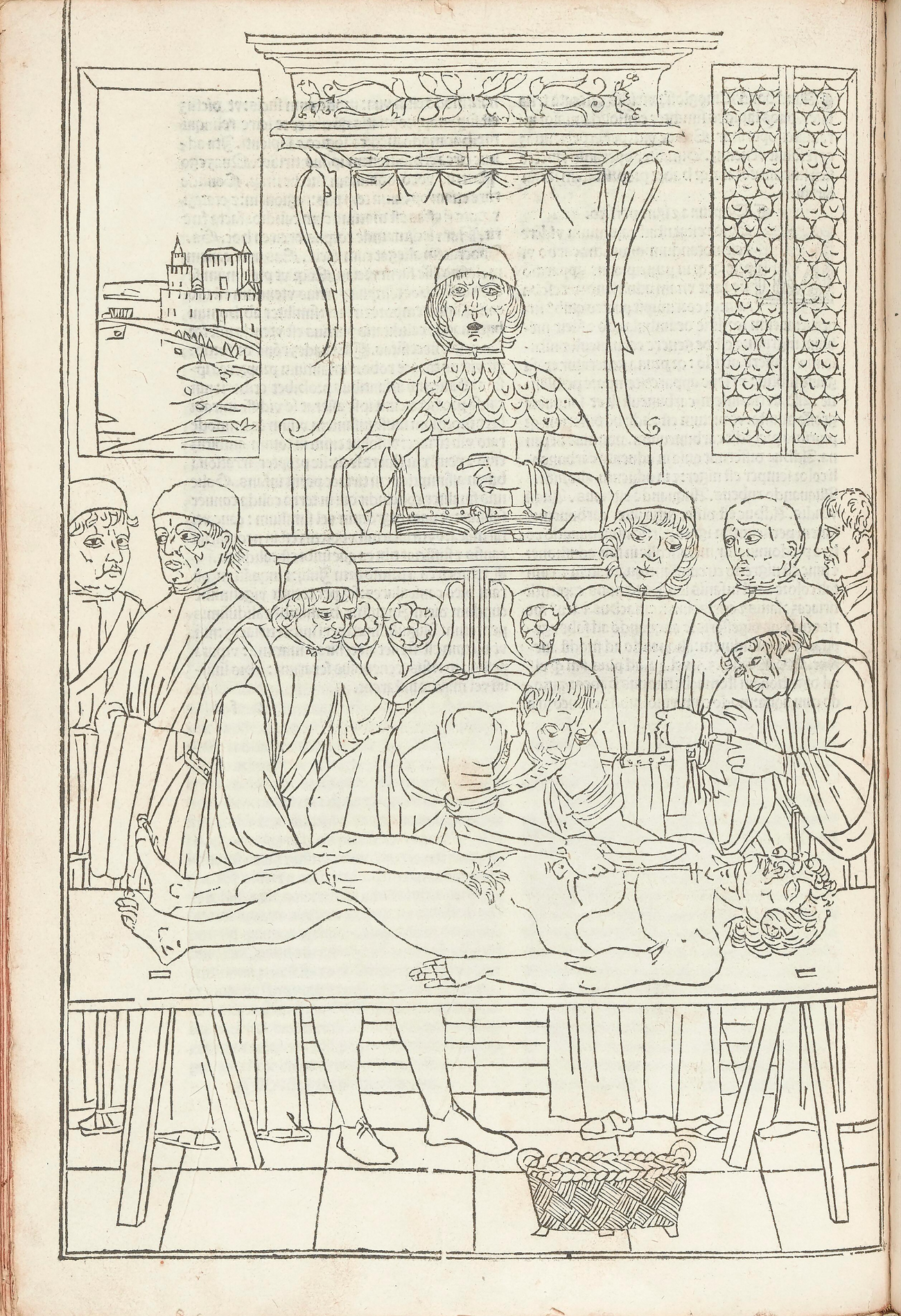

These two models of dissection—the tripartite and the Vesalian one—are abundantly illustrated in the visual culture of anatomy; these illustrations often reveal the contrasting roles played by touch in each of these two early modern approaches to the practices of dissection.Footnote 47 Those in favor of the medieval anatomical model would split the space of the picture in two in order to visually represent the higher authority of the lector, who stands at a distance from the prosector performing the dissection on the anatomy table, as can be seen in the Fasciculus Medicinae (1495) (fig. 1). In contrast, those defending the Vesalian model, and thus claiming a better integration of theory and practice, would display anatomists delving into a cadaver's abdominal cavity with their hands, accompanied by an audience whose hands would also be touching the body or would be at close proximity, as exemplified by the title page of Realdo Colombo's De Re Anatomica Libri XV (Fifteen books on anatomy, 1559) (fig. 2). Interestingly, in the chapter of this work devoted to describing cases of unusual anatomy, the description of Loyola's 1556 autopsy is the only passage in which Colombo emphasizes the procedural role played by his hands (“I extracted with these hands innumerable stones”), whereas in all the other examples he mainly highlights his visual experience of anatomy, with more than twenty occurrences of vidi and related words.Footnote 48 For medical practitioners who, like Vesalius, Colombo, and Bonellus, were both reading Galen and cutting corpses, employing the words et tetigi in their writings was a way to make a point and advocate in favor of a personal and practical (visual and haptic) firsthand experience of the body. If many people in Northern Italy had opportunities to watch dissections, far fewer were actually able to touch the dissected bodies with their own hands. Those who did considered they had something more to say.

Figure 1. Fasciculus Medicinae (Venice, 1495), fol. [e IIv]. Wellcome Collection / Public Domain Mark 1.0.

Figure 2. Realdo Colombo. De Re Anatomica libri XV (Venice: Nicolai Bevilacquae, 1559), title page. Wellcome Collection / Public Domain Mark 1.0.

I will now have a look at two instances where the expression vidi et tetigi appears. The first is in a case history written by the Florentine physician Antonio Benivieni (1443–1502), about a century before Corsini's autopsy. During the thirty-two years of his medical practice, Benivieni made detailed notes on dozens of the clinical cases he was entrusted with, a selection of which were published posthumously in 1507 by his brother in a book entitled De Abditis Nonnullis ac Mirandis Morborum et Sanationum Causis (On some hidden and remarkable causes of disease and recovery). In one of these cases, which was not included in the publication, Antonio describes the postmortem of Aloisius Mancinus, who unexpectedly died after having been diagnosed with a strong fever by his doctors. The parents of the deceased, suspicious of the diagnostic, requested an autopsy that revealed a case of gallbladder stones, which, to Benivieni's astonishment, his doctors had failed to see: “This is the reason why, once the dead had been opened, they knew that the man had been poorly cared for, when, against the opinion [of the doctors] they found a gallbladder stone, which equaled the size of a dried chestnut, and sixty other little stones that did not exceed the size of a grain of wheat: I saw them myself, and touched them [quos ego vidi, et tetigi]: and I considered that it was a thing absolutely worthy of admiration, and I could not convince myself in any way how the doctors could have been mistaken.”Footnote 49

This case, like all the other cases that were carefully collected by Benivieni, is presented as truly experienced in person by the author, as evidenced by the expression Ego vidi et tetigi (I saw them myself, and touched them). Ego statements (using the first-person singular to highlight personal experience) are key features in published and manuscript case histories and observationes, the “epistemic genre” coined and extensively studied by Pomata.Footnote 50 The senses in these stories are instrumental to the narrative, as they validate the truth of the experience related and new ways of making knowledge. Practical forms of medical expertise became increasingly important from the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries onward, although discussions about the interplay between practices and theories of medicine happened as early as the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Bénatouïl and Draelants have recently argued that if experience was already considered critical to knowledge production in the late Middle Ages, medieval understandings of experientia differed from later conceptualizations in that medieval experience could also be indirect (and rely on the experience of authorities), whereas in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries it was personal experience that rose to prominence.Footnote 51 Evidence of this can be found in Benivieni's case histories and in Vesalius's praise to his students: “Please do feel yourselves with your own hands and trust them.”Footnote 52

The second case comes from Berengario da Carpi, a younger surgeon contemporary to Benivieni, who, in his Commentaries on the Anatomy of Mondino, published in 1521, used the expression vidi et tetigi in his discussion about the rete mirabile, a complex of veins and arteries found in some vertebrates that was held to be the organ that was the most closely connected to the soul.Footnote 53 Carpi writes that after “dissecting hundreds of human heads almost solely on account of this rete,” he had been unable to see and touch (vidi et tetigi) this organ.Footnote 54 Therefore, relying on his principle to always consider sensory experience as the best “judge,”Footnote 55 he concludes that Galen, who had described the organ in his work, could not have seen the rete mirabile and that those after him who talked about this organ did so solely on account of Galen. In this example, the senses are used as probatory tools to prove the inexistence of an organ that had been described for centuries—and which would keep on being described by medical writers long after Carpi. The formula vidi et tetigi here testifies to a new relation to the knowledge of the body, in which sight and touch became the warrants of the sensory truth of nature.

When Bonellus and his fellow witnesses decided, about a century later, to write that they had seen and touched Corsini's cadaver, they were thus using an expression that explicitly referred to a group of medical practitioners who praised practical skills and visual and haptic experience of the body, and who advocated for the value of personal experience in knowledge production. The expression was used to strengthen their testimonies and expertise, as it connected the physician and his witnesses to a scholarly network of famous surgeons and medical practitioners, who were believed to have renewed medical knowledge by using sensory organs as medical tools.

A hundred years later, in 1700, the medical procedures involved in the canonization processes were well established. In the deposition of Dominicus Parente about his examination of Giacomo della Marca, the physician noted that on 2 June 1700 he was present at the opening of the grave and that he “saw, palped, touched [vidi, palpavi, tetigi], and diligently and minutely explored” the body of the presumed saint.Footnote 56 The surgeon Carlo Prudense then explained that he personally “touched [the corpse] with [his] own hands.”Footnote 57 In holy autopsies, the expression vidi et tetigi had become a trope that encapsulated the once contested and now widely acknowledged practical expertise of these medical practitioners who were requested to establish the miraculous nature of holy bodies by the Counter-Reformation Church; it reflected the new status of medicine, presented as an ars and a scientia.

TOUCHING CORPSES AND FEELING SUBSTANCES

The importance of touch in early modern anatomy was not limited to the practical experience of medicine. Rather, it pervaded the understanding of the body from the moment medical students entered university until they became professional practitioners, especially for those who joined the ranks of medical experts requested by the church to perform holy autopsies, such as Colombo, student and successor of Vesalius at the University of Padua. In addition to being a key sense in the development of technical skills, touch was a crucial element when students learned to visualize and memorize bodily structures, and when they reflected, theoretically, on the physiology of the body.Footnote 58

In his rich account of Vesalius's public demonstrations in Bologna during the winter of 1540, Baldasar Heseler, a German student in medicine, showed that medical students had numerous opportunities to touch dissected bodies and organs. In addition to touching bones and skeletons, students were able to touch cleaned and inflated intestines, severed lungs, and even a penis. As Heseler recalls, Vesalius “showed us the substance of the uterus, which consisted of membranes and sinews and therefore was very elastic.”Footnote 59 The rectum “was thick, musculous and white, and straight.”Footnote 60 After the lecture, students were invited to see and touch the object of the demonstration in order to assess their substances and textures. Heseler explains: “Afterwards, I went up and took the dissected penis in my hands. I saw that the fistula spermatis was rather spongy. And I felt also that the testicles were soft and light.”Footnote 61 There was, of course, most likely a form of humor in displaying the penis, a way for Vesalius to entertain his audience. Yet I think there is more to it, as this scene repeated itself for other organs, like the lung: “And afterwards I took [the lung] in my hands, and it was like a very light sponge. There was a great quantity of blood in it.”Footnote 62 Heseler also reported having touched the rete mirabile—he notes that two human bodies and one sheep were dissected that day; it is likely that this dissection was performed on the sheep: “At last he showed us the rete mirabile, situated higher up in the middle of the cranium near where the arteries ascend, and forming the plexus in which the spiritus animalis are produced out of the spiritus vitales transferred there. And it was a reddish, fine, netlike web of arteries lying above the bones, which I afterwards touched with my hands [manibus meis . . . tetigi], as I did with the whole head.”Footnote 63

This was an innovative teaching technique that Vesalius used in his anatomical demonstrations, a technique that could be related to the later anatomical models of body parts made in wax, which were also meant to be touched and handled.Footnote 64 As was demonstrated by Cynthia Klestinec and Michael Stolberg, students also had multiple other opportunities to pursue their sensory inquiries in private venues devoted to teaching more practical forms of anatomical and surgical procedures.Footnote 65 It can therefore be concluded that medical students were trained with their hands when they were learning medicine.

Part of this training involved learning to feel, assess, describe, interpret, and theorize the substances of organic matter. As evidenced in anatomical textbooks and anatomical demonstrations, organs and body parts were traditionally defined and classified according to a series of criterions (“properties” or “conditions”),Footnote 66 including location, size, shape, form, quantity, color, function, and temperature and substance, the latter two both of a haptic nature. According to physiological theories, each organ had a certain temperature, or, more precisely, a complexio, a certain mix of elemental qualities among the four main qualities (warm, cold, moist, and dry). This was not new to the Renaissance, as complexional theories were developed centuries before and had a lasting influence up until the seventeenth century and beyond.Footnote 67 The human body—and food and the entire natural realm for that matter—was understood according to these four main qualities, which still framed the way in which most forms of knowledge were understood in the Renaissance, including anatomical knowledge, knowledge of the self, and knowledge of nature.

The knowledge of substances suffused Renaissance anatomical writings, because it did not rely specifically on dissections, which were contested at the time, but rather on a very strong scholarly tradition of Galenic medicine, which was framed by a haptic understanding of the body.Footnote 68 This is particularly clear in Galen's work Mixtures (Peri kraseon, translated as De Complexionibus or De Temperamentis), in which the physician from Pergamon devotes a great deal of attention to the sense of touch, stressing the long and difficult labor required by the medical practitioner to gain experience and to learn to discern the different nuances of bodily qualities.Footnote 69 In this work, Galen explains that the nature of every human being (the state of their body and of their intellectual abilities) is determined by a specific combination of the four elementary qualities (hot, cold, dry, and wet). These qualities are the “tangible qualities that are the particular object of the sense of touch,”Footnote 70 which contributes to making touch the most important sense in medical practice to Galen—and not only with regard to pulse-taking techniques. While reasoning was essential, it was through a trained sense of touch, Galen explains, that the doctor learned to assess his patient's bodily mixture, which was necessary to be able to pose a diagnostic and determine the appropriate therapeutic action. The “skin of the inner side of the human hand,” which is the “precise midpoint of the human body,” was the standard benchmark that allowed gauging of the mixtures.Footnote 71 This treaty of Galen's, rediscovered and translated into Latin in the twelfth century, became a key reference point in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, even before Thomas Linacre's edition in 1521.Footnote 72 It figured among the reading requirements in many North Italian medical schools throughout the late Middle Ages and the early modern periods,Footnote 73 which led to new discussions about bodily qualities and the complexional body, as well as to the creation of a new haptic language capable of translating these feelings into words.

In actual dissections, Heseler explains, substances of bodily parts were learned “by sight and touch” and needed to be gauged in order to determine the complexion of the body.Footnote 74 According to the Galenic physiological theories, each part had a certain substance, and thus a particular complexion, which allowed it to perform its specific function, as “the operation is the sequel of the substance.”Footnote 75 It is because the skin of the palm of the hand has a “broad tissue-like sinew” quality,Footnote 76 which consists in “something between the warm flesh and the cold sinews,”Footnote 77 that “the skin of the palm has the most perfect sensation of touch.”Footnote 78 Holy and medical autopsies displayed how theoretical physiological concepts were grounded in a haptic understanding of matter, giving touch a prominent role in dissections.

WITNESSES

However, not everybody was allowed to touch dissected bodies. In medical schools, anatomical demonstrations could be watched by a large audience—at least in their public form, organized in the anatomical theater, which, in Padua, could accommodate around two hundred people—but only medical students and practitioners appear to have touched the dissected bodies. The corpse was prepared in advance, often by student assistants (frequently called massarii or anatomistae Footnote 79) or barber-surgeons, before the demonstration was led by university-educated physicians. The performance itself could either follow the Vesalian model or the medieval form of tripartite division of tasks. This means that the presentation could be led by one medical practitioner or by several, with different sets of skills.

In any case, the sources documenting early modern lay autopsies only mention medical students and practitioners touching corpses. The epistemological advantage gained through this haptic approach to medical dissections was restricted to medical hands, albeit from a variety of skills and social standings, from students to barber-surgeons, surgeons, and physicians. The wider audience—including shoemakers, tailors, butchers, and fishmongers—was only invited to watch.Footnote 80 They may have also touched the cadaver on display, but their sensory experiences were not recorded. In contrast, as shown by the anecdote that opened this article, in holy autopsies, a variety of witnesses got to touch the corpse. Certainly, in both cases, the corpse that was being dissected was very different in nature. Holy autopsies had for their object potential saints, likely to hold thaumaturgic powers, whereas the corpses that were dissected during public demonstrations belonged to executed criminals, who were usually foreigners of low standing. Likewise, autopsies performed in hospitals were frequently performed on the unclaimed bodies of poor foreigners, which did not hold the same powerful spiritual fascination as presumed holy bodies.

While anatomical demonstrations were performed in medical schools, holy autopsies were often performed in churches, where many people came not only to watch but also to come into physical contact with the dissected bodies. The corpse of Teresa of Avila, examined during the same period as Corsini's, provides a richly documented example of multiple haptic experiences of an opened corpse. It was exhumed numerous times between her death in 1582 and her canonization in 1622, in front of various audiences, and was consistently acknowledged as “complete, and incorrupt, and with odor, and liquor.”Footnote 81 Teresa's hands were repeatedly described as particularly fragrant; witnesses reported that the extraordinary odor of her cadaver would remain for days on the hands of those who had been in close proximity to her.Footnote 82 The records of her canonization process provide numerous descriptions of her body remaining intact, “so flexible and agreeable to touch [flexibile, tactuiqu[e] suave], that it seemed she was still alive.”Footnote 83 Teresa's holy body was therefore seen as her first miracle and recorded in her printed vita, which provided little detail on the physical examination itself, in contrast with Teresa's (haptic) healing miracles, which make up the bulk of the work.Footnote 84

Among these numerous visitations to the corpse, Bradford Bouley identifies three key moments that led to her canonization. First, she was examined nine months after her death, in 1583, by anonymous medical practitioners who wondered at the incorruption of her body, which was considered even more miraculous since the casket in which it was contained was in an advanced state of putrefaction. Later on, she was examined by Ludovicus Vasquez, a medical practitioner from Alba, who submitted the corpse to a series of physical examinations, aiming to test its resistance to different conditions (cold and hot weather, with and without witnesses). The record of his investigation was included in the ordinary (local) process. Finally, her remains were examined in 1592 by Cristoforus Medrano, chair of medicine at the University of Salamanca, as well as by other physicians. The record of this physical examination was the only documented case included as evidence of the holy body's incorruption in the apostolic (Roman) process.Footnote 85

The details of Teresa's numerous exhumations were recorded in the Vatican archives documenting her canonization process.Footnote 86 In addition to showing an increasing level of medical expertise, from Alba's medicis to Salamanca's university chair of medicine, they reveal a rise in eminence among the witnesses present. The second examination was witnessed by the bishop and the governor of the city of Alba, the bishop of Tarzona (who was also the confessor of the king), and other clearly identified eminent observers.Footnote 87 In 1604, the corpse was exhumed in the presence of the Duke and Duchess of Alba, Don Antonius Alvarez de Toledo and Doña Mencia de Mendoza, and the infantado Don Joannes Hurtado de Mendoza.

These records also clearly show the diversity of forms of touch that were performed on Teresa's body, the different organs and bodily parts that were touched, and the great variety of people who were touching and testifying to having touched the corpse. Ludovico Vasquez reported touching Teresa's fully fleshed belly and intestines. Her corpse was “truly light, indicating that [it had] the weight of saintly flesh.”Footnote 88 Later on, Cristoforus Medrano scrutinized it “with particular care and diligence.”Footnote 89 The report mentions twice that Medrano “saw, and palped [the body] with his hands,”Footnote 90 which he found to be “complete, soft, and tractable,” especially in the uterus, belly, breasts, and nipples.Footnote 91 In other words, the doctors’ testimonies focused on the bodily organs that were particularly fleshy and therefore the most prone to rot after death.

Interestingly, the physical examinations performed on Teresa's corpse were not only the work of medical practitioners. The canonization process of Teresa also includes several nonmedical witness reports relating to physical contact with Teresa's corpse. Nuns were present at all recorded exhumations and most medical examinations. Some of them went further than testifying to having seen the incorrupt and miraculously fragrant body on display, commenting also on the remarkable haptic qualities of Teresa's cadaver, consistently acknowledged in the successive exhumations of her corpse, as “incorruptum,” “integrum,” “molle,” “flexibile,” “agile,” and “tractabile.”Footnote 92 This is the case, for instance, in the chapter devoted to “the beauty and whiteness of the cadaver, and the flexibility of its members.”Footnote 93 Seven testimonies were included in this section, none from doctors. Four Discalced Carmelites (Mariana de Incarnatione, Caterina de S. Angelo, Maria de S. Francisco, and Constantia ab Angelis) reported having seen Teresa's beautiful white body that did not seem to be dead, as her bodily members remained “flexible, and tractable,” which indicates that the witnesses touched the corpse, as these qualities could not be assessed by sight alone.Footnote 94 This example also shows the aesthetic dimension of physical contacts with holy corpses, as lively cadavers were experienced as beautiful evidence of God's grace on earth, since the degree of incorruption was thought to be a reflection of the favor received by the saint in heaven.Footnote 95

In 1594, the nun Anne de Jesus touched Teresa's shoulder and marveled at its wonderful colors, as they were still tinted with blood, which made them seem alive: “And when the aforementioned Anne of Jesus diligently inspected her, she saw a part of her shoulders affected by so many colors, that she said it appeared the blood was alive, and she touched this part with a cloth, and it remained stained with blood, despite the fact that the skin of the body was healthy, and without any marks, or injuries.”Footnote 96 These testimonies show that the nonmedical people who were included in canonization processes were not only there to testify about thaumaturgic miracles but also to talk about the physical qualities of the corpse. A great number of women were included among them, in contrast to medical experts, who were male.

Inevitably, haptic inquiries were further complicated by issues of gender: on the one hand, because dissection practices, and holy autopsies in particular, were inextricably gendered; on the other hand, because the sense of touch itself was readily associated with women, the body, and materiality.Footnote 97 Since these questions have been thoroughly discussed in previous research, it is not necessary to get into too much detail here. It is important, nevertheless, to remember that when examining female bodies, the male touch, especially, was ambiguous, transgressive, and problematic for reasons of honesty and decency, even when the body was no longer alive. Building on Park's previous demonstration that in the Renaissance female bodies became the “paradigmatic object of dissection,”Footnote 98 Bouley explains that in later forms of holy autopsies, male holy bodies were frequently described as “asexual and hypermasculine”; their reproductive organs were rarely examined, in contrast with women's, which almost systematically were.Footnote 99 Teresa's reproductive organs were indeed examined, whereas Corsini's were not.

The postmortem examination of Caterina Vigri (Catherine of Bologna), a fifteenth-century nun who was physically examined in the seventeenth century, is a particularly telling case. As Pomata shows, the two physicians who were convened for the examination in 1646, Giovan Battista Malisardi (lecturer in the studio) and Onorio Beati (dean of the medical college), wrote that they had “felt a certain tenderness [mollities], which clearly extended both nature and reason,” but only “in those parts, which it was decent to touch,”Footnote 100 which means that they could not or did not want to touch the entire corpse. This is in contrast with Teresa's examination. The restrictions were even stronger twenty-five years later when, in 1671, eight doctors (including Marcello Malpighi) were convened to reexamine the remains and were only allowed to see the body clothed in the presence of witnesses and to touch “the head, the neck, and the arms, the feet and legs only below the knee, for reasons of decency.” Female witnesses (“noble matrons”) were then allowed to examine the naked corpse entirely and freely touch the corpse in the absence of the male gaze.Footnote 101 These women declared afterward that they had seen no traces of embalming and evisceration and found the body to be “‘pliable and soft to the touch especially in the area of the breasts and even more so in the thighs’ (precisely those parts that the doctors had not been allowed to see or touch). . . . All they could see were some tiny cracks in the skin, especially under the breasts, due presumably, they said, to the body's desiccation.”Footnote 102 This case shows that when female bodies were examined, female witnesses could play a much more important role, as they were allowed to get in physical contact with bodily parts that would have been suspicious for male physicians to touch, most especially the reproductive organs—soft bodily parts particularly prone to rot and therefore significant to determine the miraculous incorruption of a body.

Characterized by different haptic approaches, the examinations that were conducted by male medical experts and female lay witnesses differed greatly in their interpretations of the haptic qualities of the corpses and often produced contrasting conclusions that were debated during the canonization process. The conflicting testimonies led to the contestation of the incorruption of the body: Catherine of Bologna would need to wait until 1712 to get canonized.

HAPTIC LANGUAGE

I will now look more closely into what this haptic expertise entailed and examine the specific language that was developed in the context of holy autopsies. In Corsini's autopsy report, the physician Angelus Bonellus, in addition to using his own hands to open and dissect the corpse, grounded his inquiry in a series of haptic criteria that would ultimately allow him to demonstrate the holiness of the remains. It was through the sense of touch that the incorruption of Corsini and of many other prospective holy men and women was attested: it was by touching the corpse that the doctor realized that the physical qualities of the body were absolutely exceptional. In his testimony, Bonellus describes what he saw and touched during the visitation of the reputed saint:

I saw [vidi ego] the dead body of saint Andrea Corsini, formerly bishop of Fiesole, completely buried in the Church del Carmine . . . and as [the body] was brought forward, the skin was everywhere intact [integra cute], and if you took the members which appeared slightly worn off by the frequent contact of devotion, that is, the face, hands, and feet, but the skin had kept its natural color in all of them, except on the face where [the color] was turning black because of the smoke of the luminaries; the stomach had been emptied, and negligibly filled with simple tow, without trace of any preservation technique. But [the stomach] and the thighs were among the fleshiest [carnosis] parts; the skin in its dryness conserved all its tenderness [mollitiem] from before, as it were natural.Footnote 103

Here Bonellus explicitly shows how embedded religious and medical forms of touch could be, as his testimony refers as much to the thaumaturgic contact from the wider public as it does to the medical scrutinization of the corpse. First, he noted that the skin of the deceased was intact.Footnote 104 Likewise, Teresa's skin was so supple that a finger would leave a mark when touching it, and it would straighten up once the finger had been lifted.Footnote 105 One of her vitae explains that she had lost all her wrinkles when she died.Footnote 106 The visual and haptic quality of skin mattered for obvious reasons: it is one of the parts of the corpse that is the quickest to rot after death. Similarly, the presence of eyes and ears was seen as a significant indication of incorruption. Yet cadavers needed more than just the remaining presence of skin to be deemed saintly: their flesh had to retain the haptic qualities, elasticity, and feeling of a living skin to demonstrate their supernatural resistance to putrefaction. In several postmortem records included in the canonization processes of figures who were eventually determined to be holy, the skin was described as mollis (soft, moist, tender), tractabilis (tangible, palpable, manageable, malleable, that one can touch), and flexibilis (flexible, supple). These qualities were often used to describe the skin of many candidates for holiness, highlighting the vitality of bodies that escape the effects of time and the material dissolution that follows death.

According to the Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca, the first dictionary of the Italian language, published in 1612, the term trattabile is defined as “yielding, soft, agreeing to the touch, contrary to hard, and rough.”Footnote 107 Defined as the opposite of hard, the term trattabile contrasts with the actual feeling of a corpse, which would be described today as hard and cold, since the body hardens after death due to the cooling and solidification of bodily fluids, especially fats. The term flessibilità (flexibility), also frequently used in dissection records of candidates to sanctity, carries similar meanings; interestingly, the example chosen by the dictionary Della Crusca refers to the “flexibility of the fingers.”Footnote 108 The dictionary, in the 1739 fourth edition, also associates the term trattabile with the Latin word mollis and with the Greek terms μαλακός (malakós [malleable]) and ψαλαφητός (psilafitós [palpable]).Footnote 109 The malleability of the body was one of the main evaluation criteria, as evidenced in Bonellus's report.

All these qualities—flexibilitas, tractibilitas, mollities—are haptic by nature. They refer to the plasticity of living bodies, composed of blood, fats, bodily fluids, and soft fleshy parts. Giovanni Antonio Vitale, during the canonization process of Giacomo della Marca, stated: “Beyond that I observed a certain softness in the skin, which was so sensitive that it yielded to the touch”; it was “coming from an unctuous instance of flesh which can be observed in living bodies.”Footnote 110 In contrast, cadavers are dry, cold, possess no fleshy parts, and have fragile skins that quickly dissolve—which is why the solidity of the corpse matters as well. Whether or not the sources explicitly mention that the witness had touched the corpse on display, the fact that they mention these physical qualities implies that they did, as these qualities could not be apprehended by sight alone. These features, which were key to the definition of incorruption, strongly suggest the existence of haptic epistemologies of dead and living bodies. Dissection records of holy autopsies are bursting with references to the textures of cadavers, the miraculous nature of which was assessed through the sense of touch, which allowed the examiners and the witnesses of the dissections not only to see the incorruptible body but also to feel the vitality of its holiness with their own hands.

Moreover, these physical examinations were not limited to the surface of the body. Questions of internal bodily moisture and dryness were of primary interest to these physicians. An interesting case is the description of the postmortem of Giacomo della Marca by Dominicus Bonincuntus, one of the doctors present, in 1700. Admiring the remarkably moist substance of the corpse, and deeming its resistance to touch to be clearly beyond the boundaries of nature, he highlighted the supernatural character of della Marca's holy remains over an incredibly rich and detailed ten-pages-long digression on the haptic qualities of dead and living bodies and the relationship between humidity and dryness in relation to life and death.Footnote 111 A dried-up corpse was not a miracle, as its desiccation could be explained by natural causes. Miracles, on the other hand, were defined as such when they were considered to be supernatural, which means, as highlighted by Lorraine Daston, that they superseded the possibilities of nature and were caused by God only.Footnote 112 The difference between desiccation and incorruption was widely discussed by those who, like the physician and jurist Paolo Zacchia (1584–1659), would try to define the conditions of possibility of bodily incorruption, which required, to be miraculous, not only the preservation of “the solid and dry parts [to be intact] but also those parts that are softer and humid, and more subject to deteriorate” after death.Footnote 113

In sum, there were a variety of forms of touch at play in holy autopsies, involving diverse degrees of expertise and various forms of mediation. These forms of touch were not mutually exclusive, however. Rather, they intersected and interplayed with one another, making touch a relational sense endowed with medical and religious power. To determine whether or not a corpse was incorrupt, physicians needed to touch and palp the corpse, feel every part and substance, seeking the soft fleshy parts. This ability to draw comparisons and discern the different haptic qualities of bodily parts and fluids required an embodied experience of the feeling of touching human bodies, dead and alive. In other words, these medical practitioners turned out to be experts of touch. The haptic language used in canonization processes reflects the epistemologies of touch that pervaded early modern anatomical writing, which were grounded on Galenic physiological concepts.

Bodily substances and their qualities, nature, and location on the body were thoroughly described in dissection records drafted for canonization processes. University-educated physicians were chosen not only on the basis of their practical skills, which allowed them to cut the cadavers open and explore their insides, but also on their ability to feel, identify, and fully describe these elusive sensations that come from touching. They were able to properly articulate and discuss what they had touched by integrating their sensory experience into a vast scholarship of written tradition. The importance of touch in early modern anatomy was therefore as much a question of technical practice and experience as one of language and theoretical knowledge.

In contrast, lay witnesses were more concise when describing their sensory experiences of holy bodies: they mainly stated they had touched the cadavers with their own hands and felt it was as if they were still alive. In addition, the multiple voices captured in canonization processes were mediated and filtered through the lens of medical and judicial discourses, which were highly structured texts that aimed to fulfill specific literary and rhetorical requirements. In other words, the testimonies stemming from canonization processes did not properly reflect personal experiences, but the “memory” of experiences “filtered through the theological and legal practices of the inquest, as well as the cultural patterns regarding the miraculous.”Footnote 114 Nonmedical witnesses’ words were informed and influenced by medical theories, as evidenced by the fact that they frequently resorted to the same specific (haptic) vocabulary to describe bodily incorruption. Regardless, their testimonies mattered: after being debated and negotiated by a variety of witnesses and authorities, the incorruption of the cadaver had to be unanimously acknowledged as miraculous to be considered for canonization. Conflicting anatomical reports could lead to dismissing cases of bodily holiness, as happened for Ignace of Loyola and Charles Borromée.Footnote 115

CONCLUSION: HAPTIC KNOWLEDGE

In 1601, Giulio Cesare Casseri (ca. 1552–1616), an experienced surgeon and professor in charge of private anatomies at the University Padua, wrote in his De Vocis Auditusque Organis Historia Anatomica (An Anatomical History of the Organs of Voice and Hearing) that “certain parts of bodies are soft [mollia] or hard [dura], some rare [rara] or dense [densa], others thick [crassa] or slight [tenuia], I claim that the body of the larynx is hard, dense, and thick. . . . I imagine it is accurate enough to think that this nomenclature derives from practical experience and not from any artificial criteria. . . . I shall maintain fearlessly what I have been allowed to observe in the human larynx—not once, but again and again.”Footnote 116

Casseri was a skilled dissector renowned for the virtuosity of his private anatomies. His writings and teaching practices that focused on the display of surgical skills show the important part haptic epistemologies played in his understanding of anatomy. It is, therefore, not surprising to see him promoting touch as an instrument conveying authority and expertise, such as in the portrait in which he is pictured dissecting a hand (fig. 3).Footnote 117 The value of touch and practical skills is particularly clear in chapter 8 of his work, which describes the “recurrent [laryngeal] nerves” and the way to vivisect them.Footnote 118 Reflecting on the substances of the nerves, he explains that the “closer they are to the brain . . . the more moist and soft” their substance will be.Footnote 119 Nerves, then, could be distinguished by touch:

If anybody should doubt this he should handle these nerves in various ways in his hands [manibus tractet]. Then he would observe that various differences of pitch arise: if one or two fingers squeeze them, the voice is lessened; if the nerves are tied or split, the voice is not only lessened, but completely disappears; if they are cut off, the animal will continue on through life mute. But if they are first tied and then undone again the tone of these nerves returns and is one and the same for all other nerves, in as much as they take on the appearance of the constituent nerves.Footnote 120

Figure 3. Julius Casserius. De Vocis Auditusque Organis Historia Anatomica (Ferrara: Victorius Baldinus, [1600–01]), fol. [br]. Wellcome Collection / Public Domain Mark 1.0.

The experience described above that required manipulating, pitching, and cutting the nerves of a (living) animal was not just theoretical: it was a spectacular performance of vivisection occasionally executed in public demonstrations, often on (poor) dogs. Anatomists like Casseri showed that once the recurrent laryngeal nerves had been cut, the dog would cease to bark, which exemplified the role of this organ in the formation of the voice. Vesalius had chosen the same procedure half a century earlier to urge his students to trust their own hands and minds, in the twenty-sixth demonstration witnessed by Heseler.Footnote 121 He then invited them to touch the heart of the dog, to feel its warmth on their skin, and to compare the movement of the pulse with that of the heart.Footnote 122 The lecture was concluded by Vesalius refusing to comment on anatomical structures any further, inviting his students to touch bodies and think by themselves.Footnote 123

The dissection and vivisection of the larynx is an emblematic procedure epitomizing the multiple ways in which touch shaped, negotiated, and transformed early modern understanding and experience of anatomy, from the display of manual skills to the feeling of substances; from the experience of temperature in living and dead bodies to the epistemic promotion of personal experience (vidi et tetigi). Casseri's and Vesalius's famous celebrations of the dissecting hand were not just rhetorical and literary claims about the value of hands-on knowledge aimed at self-promotion, but rather epistemic programs grounded in genuine haptic practices that engaged the sense of touch in its multiplicity. Renaissance anatomical writings are bursting with stories of people touching, squeezing, holding, scratching, stroking, cutting, testing, and experimenting with their hands. Medical practitioners write that they are palping organs, skins, bodily parts, and fluids. They describe organs in terms of their haptic qualities, including texture, consistency, and temperature, relying on sophisticated scholarly knowledge and refined specialized languages.

Touching and handling cadavers was, therefore, much more than an extravagant gesture, and marked an epistemic turn with major implications for modern medicine. Touch was a significant part of Renaissance experiential cultures, which were not limited to practices of observation.Footnote 124 This is not to say that visual cultures were not fundamental to early modern knowledge practices—of course they were. But just like in the realm of natural philosophy, where alternative theories privileging touch coexisted alongside ocularcentric works,Footnote 125 in the medical domain, touch was used in conjunction with sight, in contrasting and complementary ways.

Touch has long been considered secondary to sight because of its lasting association with manual craft and its connection with the use of the hand, typical of the lower mechanical arts in the long tradition of the classifications of arts and crafts. These classifications were fundamentally questioned in Renaissance cultures, as shown in the pioneering works of Pamela Smith and Pamela Long, which complicated previous understandings of craft and scholarly work while inspiring research in recent decades about hands-on knowledge.Footnote 126 These studies have shown that manual work was redefined in many fields in the Renaissance—including medicine and anatomy—and that the relations between book learning and technical skills must be understood not as dichotomic structures but in terms of fluid and dynamic interactions.

More recent contributions, like those from Paolo Savoia on sixteenth-century “practitioners of the body,” which rely on the earlier critical contribution from Sandra Cavallo about seventeenth- and eighteenth-century “artisans of the body,” have shown the fluidity of the barriers between medical practitioners, challenging previous narratives that assumed that manual activities were assigned to surgeons and barbers, while physicians hardly used their hands in the clinical profession.Footnote 127 This article also helps to question this narrative by confirming that Renaissance medical practices were fundamentally manual, especially in Italy, where surgery and anatomy were taught at the university, to which foreign students were flocking from all over Europe to learn more about practical skills. This article, therefore, also builds on the findings from Michael Stolberg and Cynthia Klestinec, who have both shown the importance of touch in early modern medical practices of diagnosis and anatomy.Footnote 128

While entering into conversation with these and other works, this article provides a more detailed investigation into what precisely hands-on knowledge entailed, disclosing the rich variety of ways in which haptic experiences and skills were used to produce knowledge about and through the body. The multiple forms of touch that were examined also embodied aesthetic forms of knowledge, especially if one considers the original meanings of aesthesis as referring to sensation or sense perception, as well as to the beauty of sensory experience itself. There was a form of literality in the haptic knowledge of the body: it came from the senses and expressed a greater proximity between humans and their environment, a connection diametrically different from the one humans have with the world they inhabit today.