1. Introduction

The Feast of Herod was a narrative of considerable flexibility throughout the medieval and Renaissance periods. While the events of the story were clear — it was, after all, the only saint’s martyrdom described in the Gospels, with both Matthew and Mark agreeing on the central actions — interpretations of the implications of those actions for a Christian audience varied from the outset. According to the biblical sources Herod Antipas, the first-century tetrarch of the Roman territories of Galilee and Perea, took Herodias, the wife of his brother, as his own wife.Footnote 1 When John the Baptist condemned this relationship as inappropriate under Jewish law, Herod imprisoned him. The tetrarch and his wife then arranged for Herodias’s daughter (unnamed in the Bible, but identified as Salome by Josephus) to dance at Herod’s grand birthday banquet.Footnote 2 As he expressed great pleasure at her dance, he vowed to give her any recompense she requested; the girl was instructed by her mother to ask for the head of John the Baptist, and, in light of his public oath to her, Herod was compelled to acquiesce. The Baptist was beheaded in his prison, his head was brought to Salome at the feast, and the girl took the head to her mother. That John was unjustly martyred for having taken an ethical stand was in no doubt in the Gospels; less clear were the motivations of the various actors. Matthew suggested that Herod and Herodias were jointly offended by a public denunciation of their illicit sexual relationship. On the other hand, in Mark’s Gospel Herodias was a kind of ancient femme fatale, driving her husband — who knew that John was a “righteous man and holy and kept him safe”Footnote 3 — into ordering the saint’s execution.Footnote 4 For Josephus it was Herod’s fear of John leading a rebellion against him, rather than personal spite, that required the Baptist’s execution. For some commentators Salome’s dance — an entertainment commonly provided by women of ill repute in the ancient worldFootnote 5 — was an excuse for Herod to order the execution, while for others she seduced him into the act. The daughter could be seen as the unwitting pawn of her mother or stepfather or she could be said to harbor evil intentions toward the saint that were fulfilled in her horrific request. Hence, the sources of evil in the event were variously defined.Footnote 6

Early medieval commentators found plenty of blame to spread around. For many writers Herod’s authorization of John’s beheading was seen as an element in a larger pattern of sinful behavior in the tetrarch, exemplified by the self-celebration and physical intemperance inherent in his birthday feast.Footnote 7 St. Ambrose (ca. 340–97) provided a typical reading: “Look, most savage king, at the sights worthy of thy feast. Stretch forth thy right hand, that nothing be wanting to thy cruelty, that streams of holy blood may pour down between thy fingers. And since the hunger for such unheard-of cruelty could not be satisfied by banquets, nor the thirst by goblets, drink the blood pouring from the still flowing veins of the cut-off head. Behold those eyes, even in death, the witnesses of thy crime, turning away from the sight of the delicacies. The eyes are closing, not so much owing to death, as to horror of luxury.”Footnote 8 But the women did not escape culpability. In the same sermon Ambrose also condemns Salome: “when a larger concourse than usual had come together, the daughter of the queen, sent for from within the private apartments, is brought forth to dance in the sight of men. What could she have learnt from an adulteress but loss of modesty? Is anything so conducive to lust as with unseemly movements thus to expose in nakedness those parts of the body which either nature has hidden or custom has veiled, to sport with the looks, to turn the neck, to loosen the hair? Fitly was the next step an offence against God. For what modesty can there be where there is dancing and noise and clapping of hands?”Footnote 9 On the other hand, for Augustine (354–430) Herod was a weak man in the hands of a dangerous wife: “That detestable woman, however, conceived a hatred to which sooner or later, given the occasion, she would give birth. When she was brought to bed, she bore a daughter, a dancing daughter. And that king, who held John to be a holy man, who feared him because of the Lord, even if he did not obey him, when John’s head in a dish was demanded of him, was deeply grieved. But because of his oath and because of the guests, he sent a halberdier and carried out what he had sworn.”Footnote 10 So medieval commentators could blame any or all of the main characters for John’s death.

With texts offering a range of motives, it is hardly surprising that details in the artworks that represent the Feast of Herod also diverge. In medieval and early Renaissance art in Italy the narrative normally occurs not in isolation, but as the culminating scene in Baptist cycles of every medium. As such, it defines John’s perfect ascetic character in the face of worldliness and establishes his role as the forerunner of Christ. The Baptist is the only saint to enjoy two feast days in the liturgical calendar, the celebration of his birth and the commemoration of his beheading, so it is possible to devote special attention to representations of his martyrdom.Footnote 11

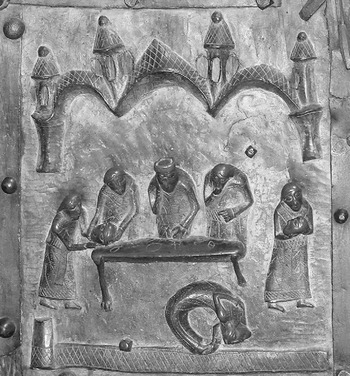

Three compositional formulas for representing the feast survive from medieval Italy: Salome tumbles before the banquet table as John’s head is brought in; Salome dances beside the table, balancing the platter with the Baptist’s head atop her own head; demons inspire Salome to a relatively decorous dance alongside the table, and the head is brought in separately.Footnote 12 In all three approaches, more often than not Herodias is seated at the banquet table, but occasionally Salome follows her dance by presenting John’s head to her mother in a separate space. The formulas overlap chronologically, and it is not entirely clear why particular artists or patrons favored one over the other. The first is a Northern European tradition, and surely develops out of jongleur entertainments:Footnote 13 indeed, textual references survive that identify Salome as a jongleuse. Since the early medieval period jongleurs had been criticized consistently by clerics as obscene, unnatural, and lascivious, so it is not surprising to find Salome among their number. The acrobatic display of Salome’s dance is particularly striking in this iconography. Without minimizing Herod and Herodias — they are, in fact, normally the largest figures in the compositions — artists draw viewers’ attention to the indecorous behavior of the girl through an extraordinary pose, usually a backflip or handstand, that clearly communicates her depravity. This iconography is quite rare in Italy, however, and is best known from the twelfth-century door of the church of San Zeno in Verona (fig. 1). Scholars suggest that jongleurs were increasingly perceived in a positive light from the early thirteenth century in Italy, which may explain why the Northern motif seems to have gained little purchase in the South.Footnote 14

Figure 1. Feast of Herod, twelfth century. Verona, San Zeno. Author’s photo.

The second iconographical approach is Byzantine and may be found widely throughout the eastern Mediterranean over a long period of time: in this version Salome dances with the platter containing the Baptist’s head atop her own head (fig. 2). It very likely derives from a Greek exegetical tradition that describes the dancing girl displaying John’s head in triumph.Footnote 15 Again, it is a relatively rare motif in Italy, found primarily in areas of Byzantine domination such as Venice (San Marco) and Sicily (Monreale cloister). Herod and Herodias usually host the feast, but the utter horror of Salome’s display of the head focuses viewers’ attention on the girl. In the Greek vitae that relate this narrative, the devil inspires Herodias’s vengeance and Salome’s triumphant dance, but demons appear in the representations only seldom, and relatively late, during the fourteenth century.Footnote 16

Figure 2. Feast of Herod, fourteenth century. Venice, San Marco. Scala/Art Resource, NY.

The same Byzantine textual tradition may very well have inspired the third medieval Italian formula of the event, for the girl is egged on to her dance by demons in a number of representations, including the lintels over the baptistery doors at Pisa and Parma. In these images Salome’s dance is far less spectacular — she does little more than shift her weight and wave her arms — but even when her behavior is more dignified, artists tend to fault her. Benedetto Antelami carved the lintel of the entrance into the baptistery at Parma in the early thirteenth century (fig. 3). His relief shows Salome merely standing beside the banquet table, but a demon, labeled Satan, shoves her forward into her evil request, while the beheading of John occurs behind her.Footnote 17 Herod pulls at his beard in a gesture commonly related to distress, and Herodias lays a troubled hand on her chest. Readers of the Bible or a vita of the Baptist could certainly infer that the king and queen’s concern is feigned, but from the perspective of direct narrative illustration, only Salome is in the hands of the devil in this image.

Figure 3. Benedetto Antelami. Feast of Herod, thirteenth century. Parma, Baptistery of San Giovanni. Author’s photo.

A break with the traditional compositional formulas comes in the earliest surviving Florentine representation of the Feast of Herod: the mosaics made for the baptistery shortly after 1300. Though their style is Byzantine in inspiration, their iconography follows no known Byzantine model.Footnote 18 The artist separates the narrative into three scenes: the dance, the beheading, and the presentation of the head to Herodias (fig. 4). Salome’s dance is relatively restrained — she raises her right arm above her head to snap her fingers while she bends her left knee and cocks her left arm — but no demons impel her action. The execution of the Baptist occurs not behind her back, but under her direct supervision, and the presentation of the head elicits sorrowful and concerned expressions from the king and queen as the girl appears to smile smugly. If anything, Salome appears even more responsible for John’s death here than she does when she dances or acts as if possessed in other depictions of the narrative.Footnote 19

Figure 4. Feast of Herod, Decollation of the Baptist, Presentation of the Baptist’s Head to Herodias, ca. 1310. Florence, Baptistery of San Giovanni. Author’s photo.

Regardless of how blame is spread across the three characters in the textual tradition, then, in medieval Italian artistic convention Salome is most often the centerpiece of the event. She dominates through her bizarre dance or her command of the action, and the average viewer — no reader of biblical commentary in Latin — must have focused on the girl as the wicked heart of the story. By the end of the Middle Ages the varied textual assignation of culpability comes, in a sense, to follow the visual tradition: guilt is almost always laid on only one character. That guilty character is not, however, Salome, but her mother. Both The Golden Legend and The Meditations on the Life of Christ concentrate on the Baptist’s character as a perfect martyr, rather than on his enemies, but in the Vita di San Giovanni Battista, an anonymous vernacular biography of John produced in Florence early in the fourteenth century, Herodias stands out as the active villain in the plot.Footnote 20 She abuses John from the moment he speaks to her and Herod:Footnote 21 while the king seems open to the Baptist’s message and fears harming him because he is beloved by the people, his “awful” wife has such control over him that he has to follow her lead.Footnote 22 Herodias consults with demons to concoct a plot. She summons her daughter, whom the demon teaches “new and delectable things”;Footnote 23 she instructs Herod to look sad when Salome demands the head; she tells the girl to cry and carry on if Herod hesitates to comply with her request. When the officer comes to execute John, all the prisoners and guards cry out and start to “damn the girl and her mother, because they had already heard how it was they who had demanded it.”Footnote 24 Salome is certainly not innocent — a demon inhabits her as she dances, and the “awful” girl takes the head to her “even more awful” mother — but Herodias instigates the action and rejoices in her revenge.

A sacra rappresentazione of the beheading of St. John, performed in Florence in the 1450s, follows a similar line.Footnote 25 Herod fears the repercussions of harming John, but his wife is determined, and he accepts her plot: it makes him happy to please her.Footnote 26 The guests urge Herod to reward Salome for the dance and insist he keep his promise to her, further diminishing the king’s active role in the decision, and Salome’s request, tone, and reaction to Herod’s expressions of horror are all carefully scripted by her mother. Herod insults Salome harshly, calling her the “worst of whores,” and utters unwavering disgust for the “sinful” and “villainous” request — but such invective is typical of the period and must have appeared part of the plot to a contemporary audience.Footnote 27 Only Herodias is shown punished, for in the last action of the play an earthquake strikes when she takes the head from Salome, and her body is swallowed by the earth. In general, then, while no audience could doubt that Herod, Herodias, and Salome are all sinful, Herodias is presented as the center of the wickedness in surviving texts that describe John’s martyrdom in early Renaissance Florence.Footnote 28

At the same time that texts focus on the guilt of the women, Herodias and Salome come to dominate the story in Italian works of art. Dressed in contemporary costumes, acting out the narrative in lifelike settings, the characters in early Renaissance images bring the distant historical event of John’s martyrdom into the current world. Just as they modernize the staging of the narratives, artists refashion the nature of the women’s wickedness: neither freakish nor possessed, Herodias and Salome become exemplars of depraved Renaissance women.

2. Giotto’s Feast of Herod in the Peruzzi Chapel

Mother and daughter do not share their dominance of the Feast of Herod: instead, Italian artists take two approaches to the story, choosing one or the other of the women to hold accountable for the saint’s death. In the first approach Herodias is blamed, following closely on the interpretation of the narrative found in contemporary texts. Giotto (ca. 1266–1337) appears to have initiated this interpretation in a fresco cycle of the life of John the Baptist in the Peruzzi Chapel at Santa Croce in Florence. The cycle is undocumented, and scholars cannot agree on its dating, but it was likely executed in the second or third decade of the fourteenth century. It comprises three frescoes that represent the annunciation of the saint’s birth to his father, John’s naming, and his martyrdom in an abbreviated vita that marks the Baptist’s saintly character from conception to death.Footnote 29 The Feast of Herod is the most visible scene, at the bottom of the wall (fig. 5). The fresco is in exceptionally poor condition, so it is helpful to look at a near copy of it, in the predella of an altarpiece painted in the workshop of Agnolo Gaddi (ca. 1350–96) at the end of the fourteenth century, today in the Louvre (fig. 6).Footnote 30

Figure 5. Giotto. Feast of Herod, ca. 1320. Florence, Peruzzi Chapel, S. Croce. Alfredo Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

Figure 6. School of Agnolo Gaddi. Feast of Herod (detail of a predella panel), ca. 1390. Paris, Louvre. © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY.

Giotto’s conception of the feast derives from the mosaics in the Florence baptistery, although he has reworked the separate scenes into a single continuous narrative and has made changes that alter its emphases.Footnote 31 The mosaics do not follow an established compositional formula but are still linked to tradition; Giotto, however, breaks from the medieval versions of the narrative. He represents the three episodes that are customarily included — the beheading, the dance at the feast, and the presentation of the head — but he places these events in a new kind of space and arranges his actors in new relationships that convey multivalent messages to the audience.

Giotto’s Baptist Cycle occupies the entire left wall of the relatively small Peruzzi Chapel; since the chapel was originally closed off by an iron gate, most viewers would have experienced the scenes from outside the space. Hence, the Feast of Herod would have been viewed from an oblique angle to the left (fig. 7).Footnote 32 In response to this viewpoint Giotto arranges the narrative to unfold before the spectator in a temporal manner. On the left side of the scene, closest to the viewer, is the decapitated body of St. John in the door to his prison. Blood flows from his neck toward the viewer: it is a horrific sight, quite unusual in this period, that, in its original condition, would probably have shocked and disturbed.Footnote 33 The eye then moves beyond the martyred body to settle on the presentation of the head at the feast. A soldier, whose back is toward the viewer, offers the head to Herod on a platter, who appears silent and almost still, but gestures to his left to the figure of Salome, whose dance is so controlled that she scarcely appears to move. These poses, together with the recession of the architectural setting, move the eyes to the right, or, from the spectators’ experience outside the chapel, back into space. Beyond the banquet chamber the figure of Salome appears again, now a small girl before her mother, who faces toward the viewer. Salome’s docile kneeling posture here, along with her relative stasis earlier at the feast, produce an impression of the girl more as an obedient daughter than as an active agent in John’s martyrdom. Herodias looms over the girl — she is significantly larger — and stares, impassive and unconcerned, into the face of St. John, whose death she has caused. By separating Herodias from the main action, Giotto leads the spectator to a quite specific experience of the narrative that begins at the mutilated body and ends with the perpetrator of the plot against John. Herodias is the unfeeling villain of the piece.Footnote 34

Figure 7. View from outside the chapel of Giotto, Feast of Herod, ca. 1320. Florence, Peruzzi Chapel, S. Croce. Author’s photo.

Although the fresco represents the Baptist’s saintly character through the horrific details of his death, Giotto’s Feast depicts more than just the narrative of John’s martyrdom. The painting was produced within the highly self-conscious culture of early Trecento Florence, for a patronal family that loomed large in the mercantile society of the city. Giotto situated all the frescoes in the chapel within a convincingly naturalistic, contemporary context. Settings resembled the real world of fourteenth-century Italy, costumes reflected people’s actual garb, and figures appeared to move in lifelike ways. This naturalization of sacred stories has always been seen as Giotto’s artistic revolution, but naturalizing also marked significance, creating a reciprocal relationship between the imagined world and its audience. Painted figures did not merely mimic what people in the real world did, they mirrored actions back to the viewers, and in the naturalistic world that Giotto created these behaviors were not only spiritual, but also social.

One route to understanding social norms of early Renaissance conduct for wealthy merchants is via the extensive network of didactic and pastoral literature that emerged in twelfth-century Europe, and that only waned in popularity in the sixteenth century.Footnote 35 Written in Latin and in vernacular languages, instructional texts were produced throughout Western Europe. While only a few circulated widely or were translated into other languages, the surviving texts followed patterns that suggest a pan-European approach to defining appropriate behaviors for both men and women. In the Trecento instructive sermons and conduct books were particularly addressed to merchants, such as Giotto’s patrons, who had recently achieved the wealth and influence of the nobilità but were still in many ways tied to the working traditions of the popolo minuto. Correct social conduct became a means for merchant families to reinforce their connections to the former and diminish their similarities to the latter, and instructive literature provided clear parameters for determining proper comportment. As Laura Jacobus has suggested for the Scrovegni Chapel, art “propagated ideological norms of behavior in the service of the new class.”Footnote 36

One of the primary pedagogies found in didactic texts was the use of exempla, stories that illustrated precepts in action. Exempla could come from the Bible, from familiar stories, or from real life, and typically included both admirable and despicable behaviors. Art historians have proposed for some time that images, too, could serve as exempla.Footnote 37 In the fourteenth century the Florentine poet and lawyer Francesco da Barberino (1264–1348), contended that viewers should use images to shape their behavior.Footnote 38 The Dominican friar Giovanni Dominici (1356–1419), an influential preacher and writer in early Quattrocento Florence, suggested that images were important vehicles for properly educating children, who should grow up with representations of “figures that would give them a love of virginity with their mother’s milk, desire for Christ, hatred for sins, disgust at vanity, shrinking from bad companions, and a beginning, through considering the saints, of contemplating the supreme saint of saints.”Footnote 39 Scholars have mostly focused on artworks as positive models of behavior, seeing depictions of saints as paradigms of appropriate conduct, but texts make it clear that scoundrels also offered lessons to readers in the display of unacceptable misbehaviors. Among the latter, the actions of John the Baptist’s enemies figured frequently.Footnote 40 Thus, rules of conduct offered both general attitudes toward comportment and specific interpretations of the Feast of Herod that cast considerable light on ways early Renaissance representations of the narrative could be understood.

The main actors in sacred narratives were normally saintly characters and were more often male, but the Feast of Herod offered three villains, one male and two female, which gave it a particular focus on feminine misconduct. It was marked by a constant undercurrent of sexuality, even when no explicit eroticism was described. Retellings of the story in the early Renaissance made it clear that the narrative was driven by the vice most closely linked with women: luxuria. Herod was “vinto dall’ amor” (“lovestruck”) for Herodias and sought only to please her, while Salome’s demonic dance offered “delectable things”; sensuality was implicated throughout. By the very nature of the story Herodias and Salome were evil — intemperate, self-indulgent, vicious — so any behaviors they displayed had the potential to be tarred with a negative brush. The narrative thus offered the opportunity not only to relate the story of St. John’s death, but also to demonstrate current concepts about feminine misbehavior. Like the many conduct books addressed to women, the Feast of Herod could provide lessons on comportment a woman should avoid, to “serve as a warning to her to be on her guard.”Footnote 41

In the Peruzzi Feast Giotto depicts three main actors, six subsidiary actors, and the body of John the Baptist. He foregrounds the saint, placing the headless body to the left, nearest the spectator outside the chapel space, and setting the severed head at the center of the image for a viewer standing directly before the fresco within the chapel. However, John is a passive vehicle for the actions of Herod, Herodias, and Salome. Herod is identified as the king by a tall hat and a large scale, and he is seated at the center of the fresco, facing the Baptist’s head. With his powerful male nature and prominent situation, he ought to dominate the scene, but Giotto pushes him into the background: behind the table with his guests, Herod barely registers on the audience.Footnote 42 The eye instead concentrates on Salome and Herodias, and contemporary viewers would have read their actions in light of a strong sense of how women should not conduct themselves.

The scene takes place within Herod’s palace. Giotto creates a persuasive impression of interior space by filling the fresco field with architecture and sharply marking its limits. This setting is remarkably different from that in medieval representations of the narrative, where the space of Herod’s palace is never fully described. Although definition of interior space is one of Giotto’s interests in his Santa Croce frescoes in general, it is particularly appropriate to this narrative, for the domestic interior is the sphere of female action. Restricting women to their homes was a constant in the pastoral and didactic literature of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, and while men had authority over women at all times, the wife was to take charge of the domestic economy, managing the household and raising the children.Footnote 43

Since a domestic setting was normally considered a woman’s sphere, Trecento viewers would likely have looked for Herodias in this scene, even had Giotto not made her the focal point of the composition. She is an isolated, unfeeling character, lacking any of the merciful and nurturing qualities considered essential to a good woman.Footnote 44 Her segregation from all company is unexpected. In medieval representations she is most often seated at the table, among the banquet guests; in the few examples when she is separate, she is normally flanked by companions.Footnote 45 While nothing as obvious as disorder reveals her mismanagement, things are nevertheless awry in the palace: bloodshed on her threshold; presentation of a horrific dish at her table; lack of supervision, or even a female companion, for her daughter; and indifference to John’s suffering. All signal to the contemporary audience that Herodias is not a proper woman.Footnote 46 That she acted against a man of God makes her still more despicable: in a thirteenth-century conduct book from France, Herodias’s folly is her “hatred of all holy men.”Footnote 47 Most serious of all, her improprieties have brought dishonor to the casa. In the Trecento the casa was both the house and the family, and any failure on the wife’s part to protect the former brought shame to the latter. Sexual misbehavior was the most dangerous threat to family honor: while Herodias displays no such conduct in the fresco, the whole plot is motivated by her adultery, so the implication of unchastity pervades the scene.Footnote 48

Luxuria does not, at first, appear to have any role to play in Giotto’s fresco; the style of his bulky figures, with their measured movements and enveloping garments, does not lend itself to sensuality.Footnote 49 But there are two elements of the painting that would have reminded viewers of the sexual current informing the narrative: nude statues stand on the roofline of Herod’s palace, and Salome is the only woman in the banqueting hall.Footnote 50 Although Trecento artists and audiences were familiar with ancient nudes, they would have associated them with pagan luxuria, not with Jewish tetrarchs, and girls in this period were consistently cautioned that appearing in public without female companions “could diminish [their] honor.”Footnote 51 Such warnings came from female as well as male writers: in the Livre des trois vertus, Christine de Pizan (1363–ca. 1430) advised girls at festivities not to go among the men, but “always stay near their mothers or other women.”Footnote 52

Beyond her lack of female companions, Salome’s dancing was itself potentially troubling, and, while her pose was far from acrobatic, Giotto raises a link to the problematic jongleur tradition by dressing the musician in a parti-colored garment and having him play the vielle. Both costume and instrument were favored by jongleurs, and the vielle was the preferred instrument for dance music in the fourteenth century.Footnote 53 But dance of any kind could be a problem. Exempla in moralizing literature normally condemned dancing; often demons were part of the dance.Footnote 54 This familiar connection between dance and devilry could have revived in viewers’ minds the demon that inspired Salome’s dance in the Trecento vita of the Baptist and in several medieval representations of the scene.

On the other hand, social dancing was a popular patrician pastime, as Boccaccio in the fourteenth century, and Castiglione in the sixteenth, made clear. Moreover, dance and music became an increasingly important part of Italian public rituals and ceremonies in the early Renaissance, and girls from the best families were expected to perform with no dishonor. Both male and female dancers celebrated triumphs and weddings and served to welcome important dignitaries to Italian cities. Even major religious festivals in Florence were marked by public dancing; while professional performers could be used, the young elite also typically participated in these ceremonies. Indeed, works of art from the period illustrate such types of festive moments, for example, Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Effects of Good Government.Footnote 55

Still, condemnations of dance continued throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Not only did clerics question the propriety of the activity, but a direct association between dance and lasciviousness was spelled out in Quattrocento dance manuals, which surely reflected a familiar opinion within the secular elite.Footnote 56 Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro (ca. 1420–ca. 1484), dance master at various Northern Italian courts in the second half of the fifteenth century, wrote a treatise on proper dance form around 1463, in which he acknowledges disapproval of the pastime: “often, in the guise of honour, [corrupt souls] even make it pimp for their shameful lewdness so that they may slyly use dancing to satisfy their lust.”Footnote 57 Because of the ambiguous attitude toward dance, its acceptability depended on strictly controlled movements. Dance manuals and conduct books made clear the limited range of movements that characterized appropriate dance, especially for women. For example, Francesco da Barberino recommended that if a woman were asked to dance “she should do it modestly, without affectations; not trying to leap like a jongleuse, so that no one says she is weak-minded,” while Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro defended dance against the accusation that it was “wicked and sinful” by arguing that “noble, virtuous, and honest” dancers would demonstrate their worthiness by following his precepts for “measured” movement.Footnote 58

Salome’s dance raised particular problems; since she was the daughter of the ruler, her performance at Herod’s feast could be considered an appropriate patrician presentation, but the dire consequences of her action cast its propriety in doubt.Footnote 59 For clerics everything about the dance was bad, while for other writers Salome’s dance could be more equivocal. Lucrezia Tornabuoni de’ Medici (1425–82) gives just such an ambiguous reading when she describes the girl’s “graceful” dancing in her poem of the Baptist’s life written in the 1470s:

She seemed as though she was sent from heaven,

so beautifully adorned, so gentle and pretty;

her garment was a lovely veil

adorned with jewels, a marvelous thing,

an incredible thing to see,

and I conceal nothing of her beauty;

so pretty was the garment she was wearing,

and how perfectly it complemented her loveliness!

But when the performance ended with the Baptist’s beheading, his followers “blamed the dancing.”Footnote 60 Hence Salome’s dancing was liminal, beautiful but perilous, and the way an artist represented it determined how the audience would judge the action.

As a representation of a dance in Giotto’s fresco, Salome’s pose is somewhat puzzling. Her body is utterly upright, and there is no indication she moves her legs or torso in any way; she is far from a jongleuse and dances in the modest fashion approved by the conduct books. The artist of the baptistery mosaics gives a stronger impression of movement with his Salome: there she twists her torso, tilts her head, and swings her arms. Although Giotto shows Salome’s arms raised, the gesture of her right arm is so damaged that nineteenth-century restorers of the fresco touched up the figure to carry a harp.Footnote 61 The artist could have chosen to represent a more defined dance posture, as is evident by the predella panel of the Justice figure at Padua, in which he depicts figures dancing more freely. In restraining Salome’s movements Giotto minimizes the inappropriate action that was the basis of her condemnation by commentators on this scene. He also demonstrates that the girl follows the precepts for appropriately controlled movement for females that was reiterated by contemporary writers.Footnote 62

Salome is just a girl: her small size in the banquet hall and in her mother’s chamber and her restrained, respectful postures in both scenes clearly signify her docility. She has been set into this spectacle by a maternal failure, indeed, by Herodias’s outright connivance. Salome’s exposure is clarified by the servants standing at her back. They block any access to more private parts of the palace and stare intently at the girl as they whisper about her actions. Whispering was a behavior conduct books discouraged, for “things which one is reluctant to make known are never correct and honorable,” and it indicated that the subject of the whispering was held in low esteem.Footnote 63 According to moralists, being the object of stares and rumors was the most embarrassing situation a girl could experience, and several early Renaissance writers indicated that Salome was put into this difficult situation by her mother, rather than by her own sinful character. Both the Florentine poet Antonio Pucci (ca. 1310–88), in the mid-Trecento, and Lucrezia Tornabuoni de’ Medici in the 1470s, excused the daughter as obedient to Herodias’s will; a thirteenth-century French conduct book used her to offer a rather mild social lesson to readers, suggesting Salome should have known not to ask her mother for advice.Footnote 64

Giotto thus outlined a particular interpretation of the Feast of Herod that mitigated Salome’s role to focus on Herodias’s culpability, using current concepts of appropriate feminine comportment to illustrate the dispositions of his characters and to serve as exempla to his audience. Beholders could understand Salome’s relative innocence through her behavior at the same time that they were instructed about how household mismanagement might make a woman Herodias-like. Notions of proper conduct both illuminated the religious narrative and accentuated lessons about contemporary life in his fresco.

3. Andrea Pisano’s Doors on the Baptistery of Florence

Giotto’s approach to the narrative strongly influenced Florentine representations of the feast for the next century. While many artists largely mimicked his composition, Andrea Pisano (1290–1348) revised it, even as he followed Giotto’s emphasis on Herodias’s guilt. The bronze doors of the baptistery in Florence (1330–36) were commissioned by the Arte di Calimala, whose members were of the same patrician, merchant class as the Peruzzi — indeed, the Peruzzi were members of the guild.Footnote 65 It was a civic, rather than a personal, commission, however, for John was the patron saint of the city, and the baptistery was one of Florence’s most important public buildings. The large bronze doors were ostentatious objects: both the materials and the technical complications of their fabrication allowed the doors to signify a special status for Florence as represented by its patron saint. The Calimala hired Andrea to fashion the largest cycle of John’s life yet created in Italy: it comprised twenty episodes rather than Giotto’s three (or the baptistery mosaics’ fifteen), and it shaped John’s life as a parallel to that of Christ, with scenes arranged according to the saint’s youth (which paralleled Christ’s infancy), his mission (Christ’s ministry), and his martyrdom (the Passion). The goal of the cycle was to illustrate the Baptist’s extraordinary character as forerunner — similar in tone to the account in The Golden Legend — and the sacrificial character of his death formed a critical element of this message.

Andrea’s version of the feast is more expansive than that of any of his predecessors. He tells the story through four scenes rather than the more usual three: Salome’s dance at the banquet, the beheading of John, the presentation of John’s head at the banquet, and Herodias’s reception of the head from her daughter (fig. 8). The door combines the iconography of the baptistery mosaics with that of Giotto: as in the former, Salome dances in one banquet scene and John’s head is presented in a second; as in the latter, Herodias is isolated in a separate chamber at the end of the narrative.Footnote 66 Since the doors have twenty panels to depict the life of the Baptist, one might argue that expanding this part of the vita is space filling, but it also allows Andrea to focus the narrative on Herodias.

Figure 8. Andrea Pisano. Life of John the Baptist (detail), ca. 1335. Florence, Baptistery of San Giovanni, south door. Author’s photo.

The composition of the Dance panel is strongly influenced by the banquet portion of Giotto’s fresco. The musician stands to the left of the table; two guests and Herod, who wears a high hat, sit behind the table at the center; and Salome dances to the right. The scene is highly simplified, with a background curtain standing in for the architectural setting and five figures spread evenly across the panel. Physically it is hard to argue for a focal point, but psychologically Salome dominates here, as all four men face her, and the three seated at the table concentrate on her dance.Footnote 67 Again she is the sole woman at a male gathering, an unacceptable situation in this period, but she is not as small as she was in Giotto’s painting, nor does she appear as docile. Moreover, her adult figure beneath the gown is more emphasized, so there is some sense of enticement in her dance.

Salome is the most graceful figure in this scene. She wears her hair rolled around her head in a fashionable style typical of women in Northern European (rather than Italian) art in this period and tops it with a delicate crown; her dress is embroidered at neck and sleeves and flows elegantly behind her.Footnote 68 Her pose is once again controlled, although she displays slightly more movement than Giotto’s figure in the tilting of her shoulders and the pressing of her left leg against her skirt. The relief is in fine condition, and viewers can see that her arms are poised in a carefully calculated position, possibly the same pose as in Giotto’s fresco. The gestures of the arms, and particularly of the fingers of the right hand, find parallels in other images of dancers: for example, the figure of Venus in the top border of the Effects of Good Government at Siena from 1348, and dancing courtiers and ladies in the Codex Manesse, a collection of love poems produced in Zurich in the first half of the fourteenth century.Footnote 69 Perhaps Andrea copied this pose from some other image of dance, but it may be that this gesture was part of a formal dance choreography. If so, it would be a sign of social status, for dance training was reserved for the elite, and choreographed dances were one way that the upper classes in Renaissance Italy distinguished themselves from the rest of society. The goal of training was to teach dancers to regulate their bodies in a beautiful way, and restrained movements were designed to express a harmonious soul.Footnote 70 Salome’s dance, then, could reveal her in a positive light: comely, reticent, graceful, and aristocratic.

John’s execution occurs in its own panel and, as in the baptistery mosaics, the saint has not yet been decapitated. But Salome is not present in Andrea’s relief: this is an all-male affair. The Baptist kneels meekly, while the executioner swings his sword and two soldiers look on; their expressions appear sorrowful, and the executioner even turns his face into his arm, as if he cannot bear the deed. Just as the Trecento vita suggests, they have probably been swayed by John’s sanctity.Footnote 71 The figures are dignified masculine types who restrain their emotions — even the executioner avoids grabbing John’s hair, as he did in the mosaic — which typifies the male ideal found in contemporary conduct books: in the words of the Chevalier de la Tour Landry, “the man is of more of harde corage than the woman.”Footnote 72

The second banquet scene follows John’s beheading: thus Andrea places it on the baptistery door directly under the first banquet scene, and its composition closely follows that of the Dance. The setting and the men at the table are basically the same. Whereas in the first scene the fiddler was at the left, now Salome stands there, and the official with the head occupies the right side of the relief, where she danced in the earlier episode. It is hard not to see a parallel between the dance and the severed head that implies cause and effect. Salome, however, shows no desire for the head in this relief: she leans back, away from the table where the platter has been set, and folds her arms tightly across her torso in a gesture that suggests reluctance and passivity. One of the guests at the table even turns to her and motions her toward the head, but she is locked in place. Salome’s dance may have caused John’s beheading; the young woman, however, did not will it.

In the final scene Salome presents the head to her mother. Here, for the only time on the doors, Andrea has created an architectural setting that completely encloses the figures and projects strongly from the surface. As a result, this relief stands out sharply from the other narratives. The architecture symbolizes the casa and recalls Herodias’s dishonoring of the family. As with Giotto’s fresco, viewers feel that they are inside, in the domain of the mother, and Salome seems far smaller here than she did in the banquet narratives.Footnote 73 Herodias is a rather bulky figure, raised up on a platform so that she fills the space from top to bottom, and she presents a somewhat disheveled appearance, with her hair half falling down her neck. Salome appears meek in her crouching pose, a shadowed void over her head: she is a very different girl from the lithe and comely dancer at the banquet. The changes in her demeanor across the three scenes in which she appears offer a strong impression that Salome is Herodias’s pawn, for her confidence seems to dwindle the closer she gets to her mother: dancing like the princess she is at the banquet, stunned at the consequences of that dance when the platter is brought in, and submissive to the will of the unlovely Herodias as she offers her the head.

The arrangement of the four scenes allows Andrea to convey two important points about the women in the narrative. First, the propriety of Salome’s behavior is underlined by repetition: in both banquet scenes she is entirely composed. Her dance is extraordinarily controlled, as in Giotto’s painting, allowing little movement of the body, but she is also tightly restrained at the presentation, her arms locked over her chest as she gazes solemnly at John’s head from across the room. Second, the addition of the extra banquet scene permits Andrea to line up Herodias’s reception of the head with John’s beheading, above, and burial, below. The mother is a massive figure who dwarfs her obedient daughter and callously accepts the gruesome relic: chillingly placed between two images of John’s demise, she is equated with death.

In Giotto’s and Andrea’s reading of the narrative, Salome maintains the character of the Renaissance good girl: a decoration to the household, modest in her demeanor, obedient to her parents in her actions, and submissive to her elders in her behavior. Herodias, on the other hand, breaks the rules. She fails to be the good wife and mother who safeguards the honor of the house and the well-being of those within it. In neither work does she show the compassion or concern that Renaissance audiences expected of the mistress of a household, and in Giotto’s painting bloodshed on the doorstep and atrocity in the banquet hall lead ineluctably to the figure of Herodias, while on Andrea Pisano’s doors she is visually equated with dismemberment and death. Herodias is no monster in these images. Despite their dire consequences, her actions fall within the range of relatively ordinary misbehavior, and she thus exemplifies conduct that Renaissance matrons must avoid.

4. Quattrocento Attitudes toward Educating Girls

In the fifteenth century Salome reemerged as the dominant character in Florentine representations of the Feast of Herod. There is no change in extant Quattrocento literature describing the event that would account for the shift of focus from Herodias to her daughter in images of the scene. The Florentine sacra rappresentazione of John’s martyrdom that survives from midcentury continues to vilify and punish Herodias as the architect of the plot against the saint, and Lucrezia Tornabuoni de’ Medici’s poetic vita of the Baptist makes Salome the innocent pawn of her mother.Footnote 74 Thus no direct textual explanation for the new emphasis on the girl survives. However, a broader shift of attitudes toward young women has been identified in Italian culture in this period, which may explain the transformation of the visual iconography.

Evidence indicates a growing role for adolescents in early fifteenth-century Florence. Richard Trexler’s analysis of youth participation in the city’s public rituals suggests that “adolescence became a new fetish of a deeply religious society” in this period.Footnote 75 In concentrating on the public sphere, studies tracing this development have focused on boys, but for several decades scholars also have noted that from the late Trecento Italians were preoccupied with unmarried girls as essential bearers of family honor. The salient characteristic of these girls was their chastity, the preservation of which was to be ensured via a number of strategies. Girls were carefully guarded from outsiders and were married young, typically in their mid-teens, to limit opportunities for perilous contact with males. Ever-growing proportions of family resources were dedicated to dowries that safely channeled girls’ sexuality toward marriage. And increasing numbers of girls were pressed into convents where, it was hoped, the physical enclosure of their sexuality would uphold the honor of the family.Footnote 76 Each of these methods engendered its own problematic consequences: girls who were physically of an age to bear children were not necessarily psychologically prepared for the task of mothering, excessive dowries tended to drain families’ wealth, and forced monachization both distressed family relationships and failed to always safeguard a girl’s innocence. While a concern for the chastity of young women was hardly novel — as not only saints’ lives but also didactic and pastoral texts from the Middle Ages make clear — the pursuit of new strategies for protecting girls’ purity that went to the point of endangering family patrimonies and imprisoning unwilling daughters in convents suggests that this issue had become almost an obsession during the early Renaissance.

External control of girls was the chief tactic for preserving their honor, but coaching them to protect their own virtue was also important. While girls’ education traditionally came primarily from their mothers, a growing interest in their formal instruction was expressed by humanist thinkers and put into practice with the emergence of educational institutions outside the home from early in the fifteenth century in Florence. Although there is no evidence for a fixed pedagogical program in these institutions, an insistence on moral behaviors — that is, behaviors that heightened religious devotion and maintained chastity — does appear to have been a constant, and exempla were one of the chief tools used to indoctrinate students.Footnote 77 Thus, intensified concern about youthful female chastity went hand-in-hand with enhanced training of girls during the Quattrocento.

A role for images in teaching appropriate and inappropriate behaviors had already been established in the Trecento; given the new cultural emphasis on girls, it seems hardly surprising that the visual arts would follow suit and focus on lessons for nubile women. The Feast of Herod offered that most rare exemplar in Christian iconography, a girl behaving badly. While the Virgin and a whole range of female martyrs could model virtuous conduct to be emulated, only Salome provided a dishonorable display that should be avoided at all costs.

5. Donatello’s Feast of Herod

Perhaps the first instance in Quattrocento art of an emphasis on Salome is found in a relief by Donatello (ca. 1386–1466) for the baptistery font at Siena, from ca. 1425 (fig. 9). Like Giotto’s and Andrea’s narratives, Donatello’s Feast of Herod is part of a Baptist cycle, but the individual scenes were designed by several different artists.Footnote 78 The font commission was opened by the operaio of the Duomo in 1416, in response to a committee of citizens who wanted a font that suited the beauty of their cathedral, while the narrative reliefs were cast in the mid-1420s. An object of civic pride, in competition with the many costly commissions assigned in Florence in the early Quattrocento, the cycle was an expensive and complicated endeavor that avoided duplicating any Florentine version of the Baptist’s life.

Figure 9. Donatello. Feast of Herod, 1425. Siena, Baptistery of San Giovanni. Author’s photo.

Comprising six episodes, the cycle begins with the annunciation of John’s birth and his naming, represents his preaching and the baptism of Christ, and ends with his arrest and the Feast of Herod. Like Andrea Pisano’s doors, it divides the vita into three categories: infancy, ministry, and martyrdom.Footnote 79 In contrast to earlier cycles, it omits John’s actual beheading. This is unlikely to have been the artist’s decision: a document recording the final payment for Donatello’s relief in October of 1427 describes it “when the head of St. John was brought to the feast of the king,” which implies that the operaio had requested this subject.Footnote 80 Curiously, scholars have not remarked upon the singular absence of the critical beheading scene. Its omission takes the audience’s attention off St. John as a martyr to focus it on responses to his death, suggesting that the goal of the cycle may have been hortatory as much as hagiographical, designed to teach viewers not only Christian history, but also how to behave among their peers.

There is, in fact, no scholarly agreement on the exact iconography of Donatello’s image. That it shows Herod’s feast is clear, and while the relief is far more complex than those of Andrea Pisano, a general compositional relationship can be detected. In the foreground of his relief Donatello conflates Andrea’s two banquet scenes, returning to the customary representation of the event, in which the head is presented at the table while Salome still dances. The king sits at the table, this time to the left, with a soldier kneeling before him to present the head; two guests sit behind the table, and Salome dances to the right.Footnote 81 The avid onlookers from the baptistery mosaic and Giotto’s fresco crowd behind Salome, while the fiddler plays in the middle ground behind the dining chamber. Donatello adds small boys scrambling to get away from the head to the left side of the scene.

The figure immediately to the right of Herod is sometimes identified as Herodias. Before Giotto she was usually represented at the table, as in the baptistery mosaics, so her presence here would be no surprise. However, despite a slight suggestion of breasts, the figure is more typical of Donatello’s masculine figures: as in Giotto’s and Andrea’s images, then, the figure is probably a male guest.Footnote 82 Another area of scholarly disagreement involves the background scene of the image. A soldier carries the head on a platter toward three women: they might be random bystanders who merely witness the head conveyed to the feast, although there is no precedent for their inclusion in the narrative, or one of those women may be Herodias, a common actor in depictions of the event. The head is the only object in the relief that is repeated, but there are no precedents or narrative-symbolic traditions for depicting its transport to the banquet. Since the normal iconography of the feast includes the presentation of the head to Herodias (at the table or in a separate chamber), it seems most likely that, as Janson suggests, this detail refers to that scene.Footnote 83

Where Giotto’s and Andrea’s figures are highly controlled, Donatello’s are intensely dramatic. Ostensibly he depicts the same narrative as his predecessors, but in Donatello’s relief every figure is in movement, and every emotion is heightened. Herod throws up his hands and pulls back from the horrible sight, while his dinner guests struggle to get away from it. Such extreme reactions are frowned upon in conduct books, which urge men to restrain their emotions and always act with composure. The vivid expressions of Donatello’s men could thus signal that they are all behaving badly, but these same reactions are also so consistent with the abnormal situation of the narrative that contemporary viewers might have seen them as totally naturalistic.Footnote 84 Their appalled, disgusted countenances contrast strongly with the reaction of Salome, drawing attention to her as she continues to twist and turn her body sinuously and fasten her dogged gaze upon her victim.

The decorum of Trecento representations of Salome gives way in Donatello’s sculpture to a girl who, although not outlandish like medieval Salomes, is nonetheless improper. Her pose can best be described as slithery, as her right arm and left leg swing behind her, while her left arm crosses over her front. Her draperies cling indecorously to the left leg, outlining its shape in a series of curves and counter-curves that are entirely unlike the concealing ample folds in the dress of Giotto’s or Andrea’s Salome. Although no specific prototype has been found for the pose, scholars usually trace it to classical representations of dancing maenads.Footnote 85 Such reliefs not only model the emphasis on feminine curves found in Donatello’s panel, but also offer a meaningful interpretive scheme, for maenads are followers of Bacchus, and their dancing is part of their carnal worship of that pagan god. Choosing this model allows Donatello to negatively characterize Salome: her pose is both pagan and erotic.Footnote 86

Of course, erotic dancing runs absolutely counter to acceptable feminine display in Renaissance culture. The moralists, theorists, and dance masters who encouraged females to dance did so under a strict understanding that all movements would be disciplined; writers who opposed public dance were precisely concerned with its potential carnality.Footnote 87 The only parts of the female body that were to be seen in public were the head, neck, and hands: although Salome’s lower body is completely covered by her skirt in Donatello’s relief, the wet-drapery style of her dress provides such an explicit view of her legs that they are close to naked. Christine de Pizan writes that the world condemns women who are “disorderly” in their dress, noting that clothes should not be “too tight, too low-cut, or in any other way immodest,” while Alberti describes how women who dress in “lascivious and improper clothing” are “provoking disapproval.” Francesco Barbaro (1390–1454) remarks in De re uxoria — a treatise on marriage written for Lorenzo di Giovanni de’ Medici in 1416 — “we approve someone who has preserved decency in her dress.”Footnote 88 So Salome’s presentation addresses beholders on two fronts: doctrinally the girl’s dance represents the evil in the world that threatens the presence of the holy; and socially her display stands for all that is reprehensible in feminine public behavior.

The sensuousness of Salome’s pose is in stark contrast to the intensity of her face. Giotto and Andrea show her as contained and even closed off from John’s head, but Donatello’s girl stares down as if to scowl into his face. The sharpness of her features and the power of her gaze give her a kind of aggressiveness that would have been seen as entirely inappropriate for any Renaissance woman, but must have been particularly startling in a young girl. Her expression is hard to define — she may be shocked, malicious, or appalled — but the force of her stare is completely outside the bounds of proper feminine behavior. One of the admonitions that occurs most often in conduct literature is that girls should keep their gazes modestly lowered.Footnote 89 For Francesco da Barberino in the early Trecento they must keep their eyes down because eyes easily transmit emotions that should remain private. St. Antoninus (1389–1459), who wrote a guide to living a good Christian life for Dianora Tornabuoni in the mid-Quattrocento, advises his reader not to look at shocking sights because “death enters by the window, that is, through the eyes.”Footnote 90

Salome may not be the sole woman at Herod’s banqueting hall in Donatello’s sculpture. Four figures pack into the space behind the girl and at the edge of the relief. Two are clearly men: the figure immediately behind Salome and a figure leaving the scene, who is half-cut by the frame. Very likely the figure to Salome’s right is also a man; all that can be seen of it is a turban and a left arm, but it appears to be masculine headgear, and a Renaissance woman would never sling her arm around a man’s shoulder. Finally, the top of the head and upper face of a fourth figure is behind the men who surround the dancer; the hair looks to be pulled back smoothly in a style that duplicates that of Salome, suggesting a female companion. Nevertheless, the men crowd Salome far too tightly for propriety. Although his hands remain close to his body, the shoulders of the man behind her curve forward almost as if to embrace her. No doubt Donatello was motivated by aesthetic issues in this arrangement — the relief is designed as a composition of diagonals and counter-diagonals — but to a Renaissance eye the men would be indecorously close to the girl. Tommasino dei Cerchiari makes it clear that good women cannot allow men to touch them: “No decent woman should allow any man who has no right to do so to take hold of her.” Christine de Pizan warns that a young girl “should not allow a man to touch her under any pretext,” because to do so would “cause great damage to the decency that there must be and to her good name.”Footnote 91

Herodias is nowhere to be seen in the relief’s foreground action; instead, she receives the head in the background of the image. Donatello represents this part of the sculpture in schiacciato carving that contrasts strongly with the high relief of the foreground scene. Scholars typically address this treatment as a stylistic issue, designed to emphasize spatial effects, but it also has an impact on the way the beholder experiences the narrative, for the background figures are fainter and harder to perceive. In a sense Donatello is duplicating how viewers experience Giotto’s fresco from outside the Peruzzi chapel (fig. 7): they look through the banqueting hall to Herodias’s chamber beyond it. But Giotto’s architecture and composition channel viewers to Herodias, turning her into the focal point, while Donatello’s diminished depth of carving causes her to fade into the background, especially in the dim lighting of the Siena baptistery.Footnote 92 Unlike her daughter, Herodias is flanked by female companions and shows no signs of misbehavior. While viewers could still blame her for the disruptions of the household, she appears so inconsequential that they could also easily ignore her. Her scene lacks any details and is minimally noticeable behind the fiddler in the middle ground, whose playing takes the viewers’ eyes back to Salome’s unseemly dance.

Through his characterization of the figures’ demeanors, then, Donatello makes the girl the lynchpin of the plot. She misbehaves on multiple levels: uncontrolled movements, an immodest exposure of her body, a display of boldness, and a failure to keep herself physically separated from men all signal that Salome is sinful. At the same time, she serves as a warning to Tuscan girls: this is the comportment exhibited by bad girls, so it is the behavior they should strive to avoid. Spiritual and social lessons are mutually reinforcing in the image.

6. Filippo Lippi’s Feast of Herod

Scholars do not normally see Donatello’s interpretation of the feast as the source for many later Quattrocento versions of the narrative, but later images do continue his focus on Salome. Filippo Lippi (ca. 1406–69) painted a cycle of the life of John the Baptist for the choir chapel of the church of Santo Stefano in Prato, 1453–64.Footnote 93 The Commune owned the rights to the chapel and the city council commissioned the work from Lippi, so the patrons were the same class of wealthy businessmen who commissioned Giotto’s and Andrea Pisano’s cycles. Although the church was dedicated to St. Stephen, and owned a relic of the Virgin, it was also the center of a Baptist cult, not only because it served as the baptistery in Prato but also because the city was under Florentine political domination. The life of St. Stephen appears on the north side of the chapel, while John’s life is related in three frescoes on the south. Establishing the parallelism between the two saints’ vitae is an important aspect of the program in the chapel, with the top tier illustrating their births, the middle their missionary activity, and the bottom their deaths. There is a particular emphasis on the youth of the two saints, which Eve Borsook has linked to contemporary pedagogy with regard to religious instruction.Footnote 94 Like the Siena font, then, the Baptist cycle at Prato has a strong didactic focus.

The Feast is the final fresco of the cycle (fig. 10), and Salome appears in it three times: dancing at the center, receiving the head of the Baptist at the left, and presenting the head to her mother at the right. Lippi uses the normal three scenes for his narrative but deploys them across a single, continuous perspectival space, which entails repetition of John’s head and the figure of Salome. The narrative unfolds clearly, however: when the girl appears in a different part of the space, she is illustrating a different moment in time, but no other figures recur.

Figure 10. Filippo Lippi. Feast of Herod, ca. 1465. Prato, Santo Stefano. Alinari/Art Resource, NY.

Aspects of the fresco are confusing. Significant parts of the image were painted a secco and have largely disappeared: not only have a number of figures become ghostly forms, but details that might help to make sense of the narrative are lost. On the left side of the fresco a large bearded male who cannot be securely identified stares out at the audience: he is a festaiuolo, bringing the spectator into the scene, but his prominence suggests he may also be an important character. Nothing in the visual tradition of the feast accounts for him, however. Herod is also problematic: recent scholars agree in identifying him as the man in blue behind the table at which Herodias sits on the right, but the narrative requires the king to witness Salome’s dance, and this man does not see her performance.Footnote 95 Moreover, his hair is arranged exceedingly stylishly, a characteristic of young men in Florence, not established, powerful males, who normally are shown wearing simpler hairstyles. Rulers were expected to dress in more expensive materials than anyone else, but the fabric of this man’s garments lacks pattern or gold, the customary ostentatious elements of the most elite male clothing.Footnote 96 The only man who fits both narratively and sartorially is the gray-haired man in a red hat at the center of the banquet table behind Salome: he has an unobstructed view of the dance, and his clothing, though simple in design, has a scrolled gold overlay that would be too magnificent for anyone but the king.Footnote 97 Separating Herod and Herodias follows Giotto’s iconography and allows the continuous narrative to work with less disruption to the scene as a whole.

Despite the damaged character of the fresco, a noticeable quality of its presentation is the lavishness of the scene. Lippi filled the tables with costly serving dishes, peopled the event with a wide cast of characters, and arrayed his actors in elaborate costumes. With more detail than any of the preceding versions of the feast, this image set the biblical story into the current world, and viewers must have recognized it as a typical aristocratic banquet. The artist went beyond making the scene naturalistic, however, for the contemporary costumes he gave his characters announced their status to the audience.Footnote 98 Comportment was still an important indicator of character for Florentines in the second half of the Quattrocento, but the appropriateness of clothing also played a significant role in determining a person’s nature, and Lippi’s careful delineation of dress offered the audience another channel for experiencing the image.

As Florentine viewers would have expected, the women in the fresco are more lavishly dressed than the men. Like dancing, elaborate costumes for women were liminal, both admired and despised. On the one hand, sumptuary laws that were constantly reiterated and revised throughout the early Renaissance disparaged feminine vanity and prodigality in excessive expenditure on dress. On the other, clothing was a public display of a family’s magnificence and virtù, and the more ornate it was, the greater the honor it expressed.Footnote 99 Herodias and Salome wear fashionable costumes, with a particular emphasis on elaborate sleeves that is characteristic of later fifteenth-century Florentine styles. Herodias is clad in an overdress in red, the most expensive color for clothing, and her gown is covered with embroidery and jeweled patterns.Footnote 100 The shoulders are defined by a kind of epaulet with fringe dangling from it, below which she wears blue sleeves that also display a pattern. Her neck is bare above the edge of her chemise, which peeks out from the neckline of her gown, and her hair is elaborately pulled up around a frame and decorated with jewels in a style not unlike that of the princess in Pisanello’s St. George fresco in Verona. With her blond hair, high forehead, and white skin, Herodias is an ideal of femininity for the period, and her appearance is hard to distinguish from those of laudable women in contemporaneous art, although her hairstyle and jewelry may be somewhat excessive for a respectable matron.Footnote 101

Salome appears rather differently from her mother. A difficult aspect of her presentation in the fresco is that it differs in each of her three appearances: while her costume is relatively consistent, changing only in color — given the degree of damage to the fresco, this is perhaps exaggerated today — her hairstyle and even her face vary. She wears a light-colored garment that is gathered twice, once below the bust, where ladies’ gowns are normally belted in fifteenth-century art, and a second time at the waist. The result is a pouf of fabric that circles her torso. Although Quattrocento women are occasionally shown wearing this style, it is far more common to see it on angels, biblical characters, and symbolic figures in Renaissance paintings, as, for example, in Lippi’s Coronation fresco at Spoleto, Gozzoli’s Destruction of Sodom at the Camposanto in Pisa, and the reverse of Piero della Francesco’s Urbino portraits in the Uffizi. Her skirts are quite long — Salome has to hold them up as she dances and receives John’s head, and they spill out behind her as she presents it to her mother — so this pouf does not serve a practical, skirt-lifting function. Costume historians have not investigated the style, making its significance difficult to discern. The dress is normally reserved for young, sexually innocent characters, but when these figures wear it, the entire costume is made from a single material, and the sleeves are very plain; in Salome’s case elaborate sleeves attach to the simple dress, which seems to suggest there is something off about her appearance.Footnote 102 Perhaps Renaissance viewers would have recognized it as a visual warning about Salome’s character.

The girl’s layered sleeves are even more extravagant than her mother’s. The undersleeve is blue, puffing out from the shoulder to be gathered just above the elbow with a bracelet or embroidered band, then clinging tightly to the forearm before ending in an embellished cuff.Footnote 103 Salome’s light-colored outersleeve consists of vertical panels of fabric that cascade down from her shoulder to end in heavy hems picked out with gold embroidery. When she is still (in the presentation of the head) the sleeve looks like solid folds of fabric, but when she moves (in the dance) the panels separate and wave around her.Footnote 104 A broad band of gold further embellishes the outersleeve at chest level. While the material and exact color of Salome’s costume can no longer be determined, it is clear that the dress represents the kind of expensive garb — in quantity of fabric, in complexity of construction, and in degree of decoration — characteristic of nubile women from the richest Florentine families.

There seems little doubt that contemporary viewers would have seen Salome, like Herodias, as beautiful. Not only is she dressed in a gorgeous costume, but she has the appealing countenance of the Petrarchan ideal: pale skin, delicate features, golden hair spilling down her neck. Modern scholars frequently remark on her corporeal appeal.Footnote 105 In terms of her physical self she ought to be a good girl, for Renaissance Florentines commonly held that outward appearance reflected inward character, so beauty equaled virtue.Footnote 106 But feminine attractiveness was not an absolute value, divorced from any ethical character: indeed, Renaissance audiences could also see beauty, in the words of Elizabeth Cropper, as “dissolute and wanton.”Footnote 107 Only women’s behaviors revealed whether their outward beauty was a real manifestation of inner worth or if it was a deceptive facade. Moralists had long been aware of the equivocal nature of appearances: according to Francesco da Barberino, some appearances that might be seen initially as virtuous could actually mask vice, and he admonished readers to evaluate the outward aspects of forms by the actions to which they led.Footnote 108 For Alberti, “a handsome person is pleasing to see, but a shameless gesture or an act of incontinence in an instant renders her appearance vile.”Footnote 109 And Lucrezia Tornabuoni de’ Medici directly addressed Salome’s beauty, writing, “nature had gifted [her] with beauty to make men marvel; but this beauty would bring about misfortune.”Footnote 110 The viewer’s interpretation of the messages conveyed by the appearances of Herodias and Salome, then, needed confirmation in their conduct.

Clearly Salome dominates Lippi’s image. She is not only the sole character repeated in the composition, but also the only active one. As with Donatello’s Salome, her pose derives from a classical model,Footnote 111 and her dance is too revealing, since her skirt shapes her leg from hip to ankle. She moves more quickly and with broader gestures than Donatello’s girl, however. Her left hand gathers her skirts so she can sweep her right leg out far behind her, and her right arm swings away from her body, setting her sleeve into eye-catching motion. Both the speed of her movements and the imbalance of her posture signal impropriety to the audience: conduct literature directs girls to move with slow, measured paces, and any public dancing should be “pudicissima” (“extremely modest”).Footnote 112 So, for example, Francesco Barbaro explains that in women “a hasty gait and excessive movement of the hands and other parts of the body cannot be done without loss of dignity, and such actions are always joined to vanity and are signs of frivolity.”Footnote 113 Herod and his guests at the table behind Salome avert their eyes conspicuously from her distasteful public display, but their movements and expressions are far more controlled than those of the diners in Donatello’s relief; only Salome misbehaves at the banquet in Lippi’s painting.

A striking aspect of the painting is an implied (if narratively atemporal) transformation of Salome from left to right. Andrea Pisano already depicts a change in the girl over the course of the narrative, but for the Trecento artist the change occurs in the direction of increased docility; for Lippi the change is toward greater boldness. As she receives the head, Salome is appropriately modest, with movements restrained, chin tucked in, and eyes decorously downcast. Her facial expression in the dance is still somewhat timid, but her body moves freely. When she presents John’s head to Herodias her head is up, her jaw juts out stubbornly, and she gazes right out of the painting at the spectator. It is almost unheard of in Quattrocento art for a main actor to look out of a narrative, and it is especially unusual in a female character.Footnote 114

Salome does not merely look out of Lippi’s fresco: she meets the viewer’s gaze. Conduct literature firmly admonishes girls to keep their eyes down, for, in the words of Tommasino dei Cerchiari, “propriety demands that a lady should not stare at a stranger.”Footnote 115 Christine de Pizan advises young girls not to have a “vague glance that wanders here and there but one that stays modestly low”; Francesco Barbaro requires women to maintain “a decorous and honest gaze”; Francesco da Barberino writes that “the shameless eye is a messenger of the shameless heart”; and Alberti notes that “a beautiful face is praised, but unchaste eyes make it ugly through men’s scorn.”Footnote 116 Making eye contact with a person she does not know is more than a breach of decorum, however, particularly if the unknown is male, for “seeing this gaze the man will believe she loves him.”Footnote 117 Hence the act is a sign of luxuria, that most pernicious of all female vices. But the vice is not Salome’s alone; beyond what it reveals of her own immodesty, the girl’s gaze has become dangerous for others. When she boldly looks into the eyes of strangers, that is, the viewers, she implicates them in her crime, since “the gaze of bad women…[will] lure anyone from good conduct.”Footnote 118

While Lippi does not disregard Herodias to the extent Donatello does, neither does he allow her to misbehave like Salome. Seated to one side of the banquet hall, properly surrounded by courtiers and maidservants, she is utterly restrained in both movement and behavior, even as her companions revolt from the display of John’s head. Although her figure, unfeeling and rather domineering, does not differ significantly from her representation in Giotto’s or Andrea Pisano’s works, Lippi does not frame her as the lynchpin of the action as those artists do.Footnote 119 Instead, it is Salome cavorting across a wide-open space and defiantly gazing out of the fresco who claims the viewers’ attention and thereby drives the action.

For Donatello and Lippi, Salome was an assertive young woman who flaunted herself inappropriately. Her beauty was a sham, and she horrified her audience through a display of willfulness that would have been censured in Renaissance girls. By making a spectacle of herself, she eclipsed any actions on the part of her elders, turning contemporary notions of acceptable feminine behavior on their heads. In the context of the real world, she served as a warning to the audience: since both artists linked her social misconduct to vice, viewers studying these images would understand the serious consequences of girls stepping out of line. Salome thus did more than propel the plot against the Baptist in these works: she exemplified conduct that good girls must shun.

7. Conclusion

The Feast of Herod was above all a religious narrative. In the art of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Florence it served to illustrate the presence of evil in the world as a man of the highest moral standards, a saint beyond all others in the words of the Golden Legend,Footnote 120 was brought low by human — above all, female — malice. In the context of the cycles examined here the first impression viewers received from the scene was very likely an awareness of John’s sanctity. Framing the event in a contemporary context allowed Giotto, Andrea Pisano, Donatello, and Filippo Lippi to humanize the message, to give viewers a way to relate to the sacred story, yet it also allowed current social values to become part of the viewers’ experience. As spectators identified the ways that a depraved woman and girl acted in this scene, they could also come to recognize that certain behaviors were to be avoided by virtuous, upper-class women.

The narrative of the martyrdom of St. John the Baptist was defined by wickedness. For readers and viewers alike in medieval and early Renaissance Florence there was no doubt that Herod, Herodias, and Salome all imperiled the saint. But in the Middle Ages that endangerment was explained by unnatural circumstances: bizarre dancing and demonic connections revealed that the characters belonged to a special category of evil. On the other hand, in the early Renaissance their damaging qualities extended beyond the threat they posed to the Baptist, for the mother and daughter broke sanctioned standards of feminine behavior. Cunning rather than innocent, unscrupulous as opposed to protective, wanton rather than chaste, wayward instead of submissive, Herodias and Salome threatened contemporary social norms, and in so doing they stood as women who continued to be dangerous even into the contemporary world of Renaissance Florence.