INTRODUCTION

In 1609, historian and geographer André Du Chesne (1584–1640) described the role of royal buildings as serving “the glory of the prince, the ornament of the kingdom, [and] the common utility of the people.”Footnote 1 Throughout Les Antiquitez et recherches des villes, chasteaux, et places plus remarquables de toute la France (Antiquities and investigations of the most remarkable towns, chateaux, and squares of all of France, 1609), Du Chesne positioned architecture as a symbol of unifying monarchical authority in a civil war–torn realm. In the aftermath of Henri II's (r. 1547–59) fatal jousting accident in 1559, France had suffered decades of political and religious turmoil. Uncertainty about France's identity and future were heightened by the last Valois kings’ inability to produce the dauphin that Salic law demanded to secure a direct succession. This situation was further intensified by the fact that, absent a male child, the heir apparent was Henri of Bourbon (1553–1610), the Protestant king of Navarre who was related to Henri III (r. 1574–89) by just twenty-two degrees. When Henri IV finally ascended the throne in 1589, he set about taking physical control of the kingdom that was nominally his. Subduing his enemies and conquering Paris would prove to be a lengthy military endeavor. Yet the process of persuading French subjects to accept the first Bourbon as their sovereign was to be an even longer project that would require social and cultural solutions. In addition to texts like Les Antiquitez and commissioned portraits of the king in the guise of classical heroes like Hercules, Henri IV leveraged the built environment to ground his authority in blood lineage and to generate a perception of continuity.Footnote 2 Among the king's cultural projects was a cycle of fifteen mural maps adorning Fontainebleau's new Galerie des Cerfs (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Interior view of the Galerie des Cerfs, Fontainebleau. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Painted between 1604 and 1608, the Galerie des Cerfs (Gallery of the stags) was created at a moment when cartography's centrality as a tool of government and an expression of political ideals was growing.Footnote 3 In its general format, the gallery engages with painted map cycles in Italy created in the sixteenth century. Yet an examination of the gallery's iconography and architectural setting at Fontainebleau, as well as the circumstances of its inception, reveal a complex history that goes beyond simple imitation. The tumultuous rise of the Bourbon dynasty, Henri IV's marriage to Maria de’ Medici (1573–1642), and dramatic changes to the royal family's way of life are all reflected in the space. Drawing on a 1989 article by Jean-Pierre Samoyault that established the basic facts of the identity of the artist, Louis Poisson (d. 1613), and the gallery's commission, a recent essay by Emmanuel Lurin positions the idiosyncratic cycle as part of a larger effort to establish Bourbon legitimacy through architecture.Footnote 4 This article expands upon that notion to read the space within the contexts of royal travel, contemporary cartographic culture, and the gallery's physical site. The vast gaps that remain in knowledge of Henri IV's building projects, along with the Galerie des Cerfs's later restorations, partially explain its absence from art historical studies. Yet a reconsideration of the map murals in relation to their spatial and temporal contexts reveals the gallery's agency in the transition from Valois to Bourbon France. To explore what was at stake in the Galerie des Cerfs, this article first analyzes the cartographic visual culture from which it emerged. It then turns to the subject of royal itinerancy, evaluating Henri IV's travels against those of his Valois predecessors and analyzing the influence of alterations to the monarchy's peripatetic lifestyle on cartography, the built environment, and the kingdom's social cohesion—all topics addressed in the gallery. It then turns to the gallery's physical setting at Fontainebleau and, finally, to the content of the paintings.

CARTOGRAPHY AS TERRITORIAL PURSUIT

Samoyault located the Galerie des Cerfs cycle in the context of Henri IV's interest in cartography, a fascination the king shared with his favored minister, Maximilien de Béthune, Duke of Sully (1559–1641).Footnote 5 Indeed, the Galerie des Cerfs was created at a moment when European sovereigns were increasingly deploying maps to understand, control, and represent their realms.Footnote 6 Renewed interest in Ptolemy's Geography led to the production of maps ranging from urban plans to national atlases commissioned by rulers across early modern Europe.Footnote 7 In France, royal interest in cartography had grown steadily since Oronce Finé (1494–1555) created the first known map of France in 1538. The ongoing foreign wars and attempts to simultaneously chart and subdue the French kingdom that had motivated François I's (r. 1515–47) cartographic endeavors likewise drove his son and grandsons—as well as queen mother and regent Catherine de’ Medici (1519–89)—to commission maps.Footnote 8 By the time Henri IV became king, cartography was well established throughout Europe as a tool of government, a source of visual pleasure, and a way to exhibit one's knowledge.Footnote 9 In his funerary oration for the king, Antoine de Laval (1544–1619) remarked that Henri “loved chorographic maps with a passion,” and the first Bourbon's commissions, along with anecdotal accounts of his collecting habits, speak to his investment in cartography.Footnote 10

As J. Brian Harley and Peter Barber have shown, maps were discursive objects wielded to address a variety of political agendas.Footnote 11 One such project exemplifies the web of significations inherent to the early modern maps that inspired the Galerie des Cerfs. In 1594, Maurice Bouguereau (d. ca. 1596) published the first atlas of France, Le Théâtre français (The theater of France), compiling maps from a variety of sources.Footnote 12 Dedicated to Henri IV, Bouguereau wed the history of the French monarchy to representations of its territories. At the beginning of the book, a table provides a royal chronology and explanatory texts describe individual regions of France through the monarchs’ presence, emphasizing cities, natural features, and historical buildings, many of which the author calls antiquities. Through references to the ancient past, Bouguereau portrayed the monarchy as an inherent feature of the French landscape, as intrinsically tied to the kingdom as the geographic features he enumerates. With its frontispiece, which bears Henri IV's arms, and the placement of the king's portrait over a map of France on the following pages, Bouguereau's atlas used royal history to bound the kingdom chronologically and geographically.Footnote 13 The unified kingdom envisioned in Le Théâtre français was aspirational; as with Poisson's Galerie des Cerfs, Bouguereau's atlas sought to define France symbolically as much as physically.Footnote 14

As maps entered the visual language of mapmakers and viewers, they became increasingly entrenched in early modern visual culture. A number of prints depict Henri IV and his family alongside maps and globes, a mode commonly employed by early modern rulers to express grandeur and territorial ambition.Footnote 15 Some of these cartographic images juxtaposed portraits of the king with a map, as in the 1591 map of Gallia by Flemish cartographer Jodocus Hondius (1563–1612).Footnote 16 Here, the king's likeness overlaps a map of France, visually merging monarch and kingdom. In the words of Monique Pelletier, in such examples the “image of France confounds itself with that of its monarch.”Footnote 17 Reflecting the reality on the ground, France's borders are either loosely suggested—as with the Pyrenees—or completely absent, as in the northeast. Early modern Europe's confused, contentious, and unstable frontiers prohibited a strictly linear definition of the state's physical limits. Cartographers and rulers alike deployed architecture to confront this ambiguity. In Hondius's image, a series of small, stylized buildings dot the landscape. This was a common visual device; a 1596 engraving by Thomas de Leu (ca. 1555–ca. 1612) employs similar architectural icons on a miniature scale, as do the earliest maps of France by Finé and Jean Jolivet (d. 1553).Footnote 18 In De Leu's image, minute maps of Navarre and France surround the king. The depiction of France shows only the northern part of the kingdom, centered on the Loire and Seine rivers that formed the primary axes of Capetian and Valois power. The use of architecture to mark territory has a long history, from Mediterranean portolan charts to the maps of Rome created by Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72) and Pirro Ligorio (ca. 1510–1583).Footnote 19 In these latter examples, the inclusion of antique monuments expressed the creators’ and their patrons’ knowledge of history, allowing them to claim intellectual ownership over cultural heritage. In the Galerie des Cerfs, France is defined through a network of royal, noble, and religious architecture. Poisson's detailed renderings of the built environment diverge markedly from their simplistic representation in printed maps like those by Hondius and Finé. Nonetheless, the visual language of both sets of images, with their juxtaposition of natural landscapes and the built environment—including road networks and villages as well as single edifices—share the goal of fortifying royal power and equating Henri IV with his territory.

Because of Henri IV's attention to Paris and his urban interventions there, the city was a favorite subject of early seventeenth century mapmakers. One example from 1609 by Bénédict de Vassalieu superimposes an equestrian portrait of Henri IV above illustrations of the king's projects at the Place Dauphine, Pont Neuf, Place Royale, and the Louvre.Footnote 20 Another 1609 map by the painter François Quesnel (1543–1619) presents similar visual links between Henri IV and the city's architecture through references to Paris's “edifices, maisons, pallais” (as Quesnel calls them in the dedication) as the source of its greatness.Footnote 21 As in the Galerie des Cerfs, these maps exploited recent cartographic developments to highlight Henri IV's connections to Paris and to the royal past embedded in its urban fabric. Expanding out from Paris, Claude Chastillon (ca. 1559–ca. 1619), a military engineer employed as a topographer by Henri IV, created a compendium of images that approach architecture in a similarly cartographic manner: Topographie francoise ou Representations de plusieurs villes, bourgs, chasteaux, maisons de plaisance, ruines & vestiges d'antiquitez du royaume de France (French topography or representations of several towns, villages, chateaux, pleasure houses, ruins, and vestiges of antiquity of the kingdom of France, 1641).Footnote 22 Although Chastillon was primarily interested in martial technologies like fortification walls, the images in his book include the decorative elements that made buildings recognizable; the signature pediment sculptures of a stag and hounds on an entry portal, for instance, identify the chateau of Anet. The book's title is significant: in this formulation, French topography—and, therefore, the French kingdom—was woven together by the architectural features that marked the landscape. As in Du Chesne's book, Chastillon makes a claim for France's antiquity, describing an explicitly royal past for France. Here the story of France is inextricably tied to the monarchy, and architecture is the enduring physical manifestation of this union. Building was also a way of improving the landscape. By attending to the built environment, the royal family accepted the mantle of stewardship of the kingdom and its inhabitants in a highly visible manner.Footnote 23

In their conception of architecture and maps as simultaneously functional and aesthetic objects, Chastillon's book and Poisson's paintings drew on Jacques Androuet du Cerceau's (ca. 1511–86) Les plus excellents bastiments de France (The most excellent buildings of France, 1576–79). Another royal commission, Du Cerceau's books attend carefully to each building's history and topographical situation.Footnote 24 This publication—which Poisson seems to have owned a copy of—connected noble and royal buildings to imagine a network of geographic and political influence that was critical to the maintenance of royal authority during the Wars of Religion in the latter half of the sixteenth century.Footnote 25 As a project that described the material reality of dynastic rule and defined France via architecture, Du Cerceau's publication was timely in its appeal. The author stated these goals explicitly, describing his hope that “our poor French (to the eyes and senses of whom do not appear [anything] other than desolations, ruins, and pillages that the past wars have brought us), taking, perhaps, in breathing, some pleasure and contentment in contemplating here a part of the beautiful and excellent buildings with which France is still today enriched.”Footnote 26 Like Chastillon's Topographie francoise, Du Cerceau's text is oriented toward a broad readership. Each entry is paired with one or more printed images and recounts a building's architectural provenance—that is, who built it, who inherited it, and who expanded or improved it. Frequent references to François I, for example, indicate that these edifices retained clear associations to that king decades after his death.Footnote 27 Du Cerceau also regularly employs the words ancienneté (length of existence) and anciennement (formerly) to suggest an even longer history for edifices like Amboise, Blois, and Fontainebleau. Like Du Cerceau's prints, the Galerie des Cerfs attempted to define a history for France that was grounded in the succession of kings and their architecture. Jacques Thuillier has described the renewal of this tendency under Henri IV as a drive to “restore in the French the consciousness of their history, and therefore of their unity, around a dynasty whose succession must appear unfailing.”Footnote 28 The Galerie des Cerfs thus consciously drew on earlier precedents while borrowing from contemporary cartographic images to represent a king and a kingdom firmly rooted in the past.

THE FRENCH COURT'S ITINERANCY

In addition to imagining a cohesive French kingdom and translating it to two dimensions in maps, the royal family animated the landscape with near constant movement. Itinerancy characterized the lifestyle of medieval and early modern monarchs throughout Europe.Footnote 29 This was, in part, because royal presence in urban and rural areas alike was an effective tool of government that supplied opportunities for rulers to grant favors, reaffirm loyalties, and, when needed, to delimit the space of their authority.Footnote 30 In France, the peripatetic royal family moved frequently among their own chateaux as well as those of the nobility and even, on occasion, less prominent subjects for much of the sixteenth century.Footnote 31 Each monarch favored slightly different routes, motivated by personal preference as well as unpredictable and continually shifting exigencies like plague, construction, weather, and war. The Hundred Years’ War, for instance, pushed the French kings from the Île-de-France, where their Capetian forebearers had focused, south to the Loire Valley. Adding to this complex network of movement, the queen's itinerary periodically diverged from that of her husband, and the royal children normally traveled separately. In addition to serving practical purposes like limiting the spread of disease, the division of these groups extended the physical range of the monarchy's outreach to its subjects and, at least in theory, the appearance of the heirs served to bolster local support for future reigns.Footnote 32

The French kings’ sojourns with subjects both noble and not created a reputation for accessibility and familiarity that was unique among European rulers.Footnote 33 By the late seventeenth century, the courts of England and Spain were traveling in progressively circumscribed regions. During periods of temperate weather, Elizabeth I made regular progresses around England, using her travels to visit prominent subjects, participate in elaborate ceremonies, and, above all, to attend to state politics.Footnote 34 In her extensive study of these travels, Mary Hill Cole shows that the queen nonetheless remained mostly in the southern part of her kingdom, especially in the regions near London.Footnote 35 Because of the need to govern the disparate geography of his far-flung empire, Emperor Charles V traveled widely and his son, Philip II, initially followed suit. As king of Spain, Philip traveled out of necessity but seems to have preferred to stay close to Madrid and Toledo.Footnote 36 Throughout the sixteenth century, members of the French royal family, on the other hand, traveled frequently and relatively widely. In the early part of his reign, Henri IV mimicked his forebearers. Many of these voyages were motivated by necessity; strategic trips to regions held or influenced by the Spanish-backed League enabled military endeavors or enhanced local support.Footnote 37 Yet unlike most of his predecessors, as the king of Navarre, Henri IV already knew the southernmost provinces well and his unique circumstances led him to frequent slightly different parts of the kingdom. Securing subjects’ loyalty in areas vulnerable to rebellion was a central objective of his itinerancy, as allegiance to the monarch was not only an obvious way to assure peace but also concretized the physical extents of royal authority. In a 1602 survey of Picardy, for example, interviews with subjects inquired about their political loyalties as a way of establishing whether a village belonged to France.Footnote 38 The relationships cultivated through direct contact were invaluable to Henri IV, as the Wars of Religion had laid bare the vast kingdom's seemingly unbridgeable linguistic, cultural, and religious diversity, and allegiance to a common ruler was viewed as a singularly unifying force.Footnote 39 Burgundian cleric Guillaume Paradin (1510–90) observed this effect of itinerancy, stating that “there is nothing that so holds a people in obedience and fidelity as the sight of their sovereign prince.”Footnote 40

Relationships nurtured by physical proximity were essential, for as Machiavelli (1469–1527) knew, and as the Wars of Religion confirmed, in France it was in the monarchy's best interest to appease the powerful provincial nobility.Footnote 41 When traveling, the monarchs interacted with the local nobility, religious groups, and civic institutions.Footnote 42 This was, in part, what made the Valois’ itineraries so successful in eliciting subjects’ fidelity: nobles, clergymen, and merchants alike clamored to be near their rulers in the hopes of currying royal favor and the financial and social rewards it promised. The residences spread across the kingdom also indexed the Crown's territorial expansion; as France subsumed regions like Brittany, the monarchy's real estate portfolio grew. Even when unoccupied, these buildings manifested the Crown's authority and stood as visible indicators of royal dominance. Because these stone structures endured through generations, many residences also visualized dynastic continuity in their union of old and new construction and continued usage. Yet despite its clear political benefits, early modern travel was dangerous and uncomfortable. France's road system was expanding, but terrestrial journeys remained arduous, especially given the large trains of people, animals, and possessions that accompanied the monarchs.Footnote 43 The hazards of navigating the French countryside were infamous among visitors like Venetian diplomat Giovanni Soranzo, whose 1550 report is riddled with complaints about the “cattivo camino” (“bad road”) he encountered while traveling with the French court.Footnote 44 Accidents occurred regularly: in 1606, for instance, Henri IV and Maria tumbled from a ferry at Neuilly-sur-Seine and the queen had to be plucked from the water.Footnote 45 That travel was undertaken despite these perils underscores itinerancy's usefulness as a political tool.

Henri IV would have absorbed this lesson during his childhood, much of which was spent at the French court. At the time of his ascension to the throne, however, one critical region remained outside of his grasp: Paris. Paris's status as the realm's preeminent city was well established; contemporaries like Du Cerceau and François de Lorraine (1519–63) referred to it as the capital long before this was an official designation.Footnote 46 Upon his release from captivity in Spain in 1529, François I had declared his desire to make Paris the court's primary home, yet his itinerary and construction projects indicate that he was not fully committed to staying put.Footnote 47 Thus, although Paris hosted the kingdom's major religious and political institutions, the true seat of power traveled with the royal court.Footnote 48 The outbreak of civil and religious war at mid-century, however, forced François I's grandsons to retreat to the relative safety of the Île-de-France, and as queen mother, Catherine de’ Medici also spent much time in the city.Footnote 49 After finally retaking control of Paris in March 1594, Henri IV established the region as the primary residence for the court and the royal family. The king's bodily safety nonetheless remained a persistent concern; Henri III's assassination at Saint-Cloud and the numerous attempts on Henri IV's own life, culminating in his eventual murder inside a carriage in Paris, attest to the threats facing the monarchs when traveling. The practical considerations of security drove the first Bourbon to occupy the same residences that his immediate predecessor, Henri III, had favored for similar reasons.Footnote 50 Less well understood, however, are the symbolic benefits—and challenges—of the decision to largely limit royal travel to the Île-de-France. Further, the connection between the royal family's peripatetic lifestyle and the built environment has received little attention, even as the court's later concentration at Versailles is remarkable precisely because it so radically altered the monarchs’ mode of living. The court's geographic settlement was a gradual process, and the paintings in the Galerie des Cerfs manifest a critical moment of change.

In settling the court in the Île-de-France, Henri IV concentrated his architectural efforts on existing residences and urban interventions rather than new projects.Footnote 51 The financial and political uncertainty of Henri IV's early reign are viewed as factors in what some historians view as a failure to build, though his visionary projects in Paris suggest that the story is more complex.Footnote 52 Contemporary texts on royal buildings indicate that familial lineage was a significant factor in how Henri IV organized his architectural efforts. Du Chesne, for example, narrated architecture through dynastic history. In his discussion of the chateau of Vincennes, the author described the interventions of Philippe de Valois (r. 1328–50), his son, and his grandson Charles V (r. 1364–80), before culminating with the contributions of the first Bourbon's immediate predecessor, Henri III.Footnote 53 Among the buildings he describes, Du Chesne signals three residences in particular as “fruits of the peace” that had been achieved through Henri IV's reign: Fontainebleau, the Louvre, and Saint-Germain-en-Laye.Footnote 54 At these sites, Henri IV expanded and renovated existent structures, appropriating their symbolic associations with previous monarchs, foremost among them Louis IX and François I. Henri IV's legitimacy as the rightful king of France depended on his ties to these two men.

François I had successfully assumed power following the deaths of Charles VIII (r. 1483–89) and Louis XII (r. 1498–1515) without male heirs, the most effective example of dynastic change in recent memory. His son, Henri II, daughter-in-law Catherine de’ Medici, and reigning grandsons all adopted François I's political authority and cultural hegemony in one way or another to convey stability.Footnote 55 It is unsurprising, then, that Henri IV chose to follow suit. Reaching back into the medieval past, Henri IV's self-identification with Louis IX (r. 1226–70) was critical for two additional reasons. First, the Bourbon king's claim to the throne remounted three centuries back to Louis IX. The chronological distance of this relation was a source of tension that Henri IV sought to overcome by foregrounding the endurance of blood ties. Second, the medieval king's sainthood lent Henri IV religious credentials that he desperately needed to overcome the stain of his earlier Huguenot faith. A woodcut by an unknown artist created sometime after 1594 visualizes these familial relations (fig. 2): an olive tree sprouts from the torso of a reclining, serpentine Louis IX and bifurcates into two branches, one of which holds the lineage of Henri IV and the other that of Henri III, which includes François I.Footnote 56 As Lurin has shown, in a similar vein, the frontispiece of Du Chesne's Antiquitez et recherches de la grandeur & majesté des roys de France (Antiquities and investigations of the greatness and majesty of the kings of France, 1609) presents Henri IV alongside portraits of Clovis (r. 481–511), Charlemagne (r. 768–814), Hugh Capet (r. 987–96), and Louis IX, relating these rulers to one another via the shared architectural pursuits described in Les Antiquitez et recherches des villes, chasteaux, et places plus remarquables, published the same year.Footnote 57 With the dedication to the dauphin and the young prince's appearance alongside his siblings, the Antiquitez further connected Henri IV's heirs to his predecessors through French architectural heritage.

Figure 2. Unknown creator. Le prix d'outrecuidance, et Los de l'Union, ca. 1595. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Rés. FOL-LA25-6. © Bibliothèque nationale de France.

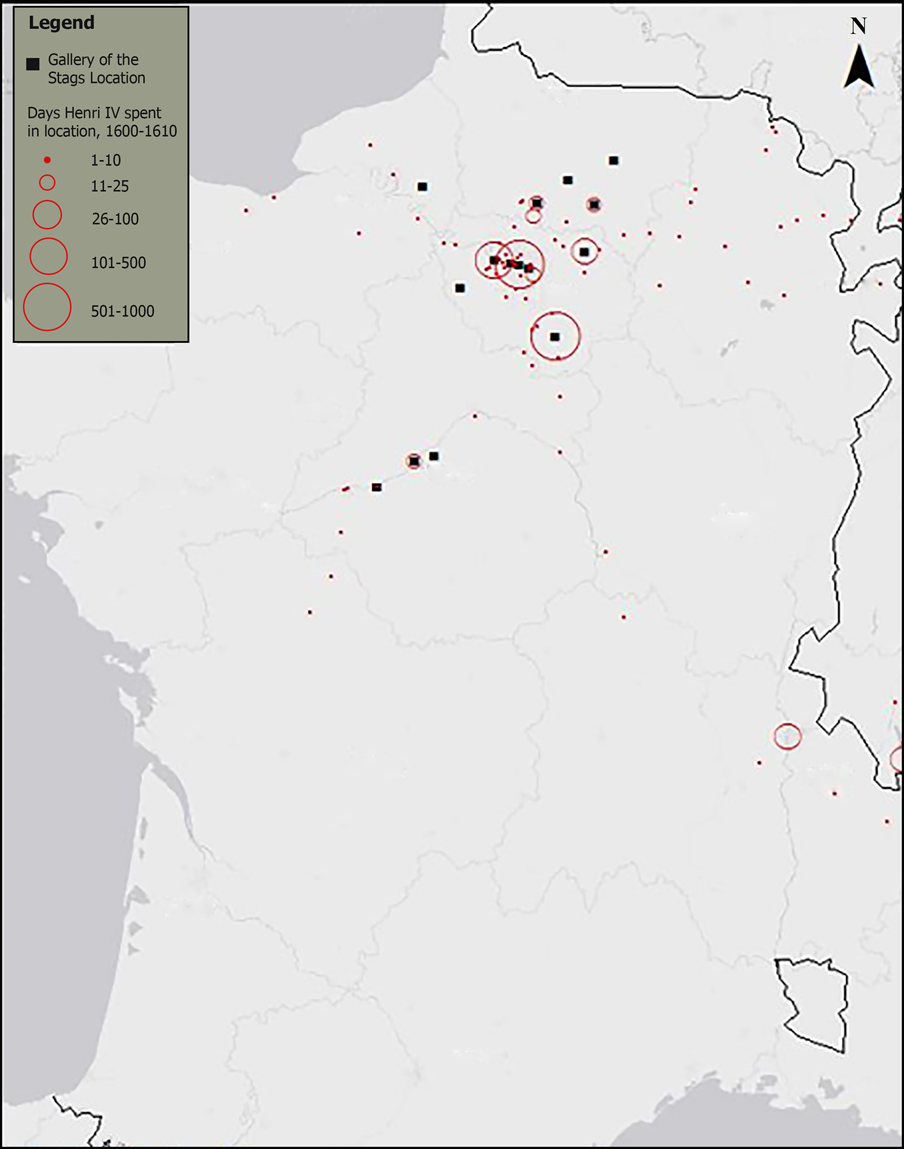

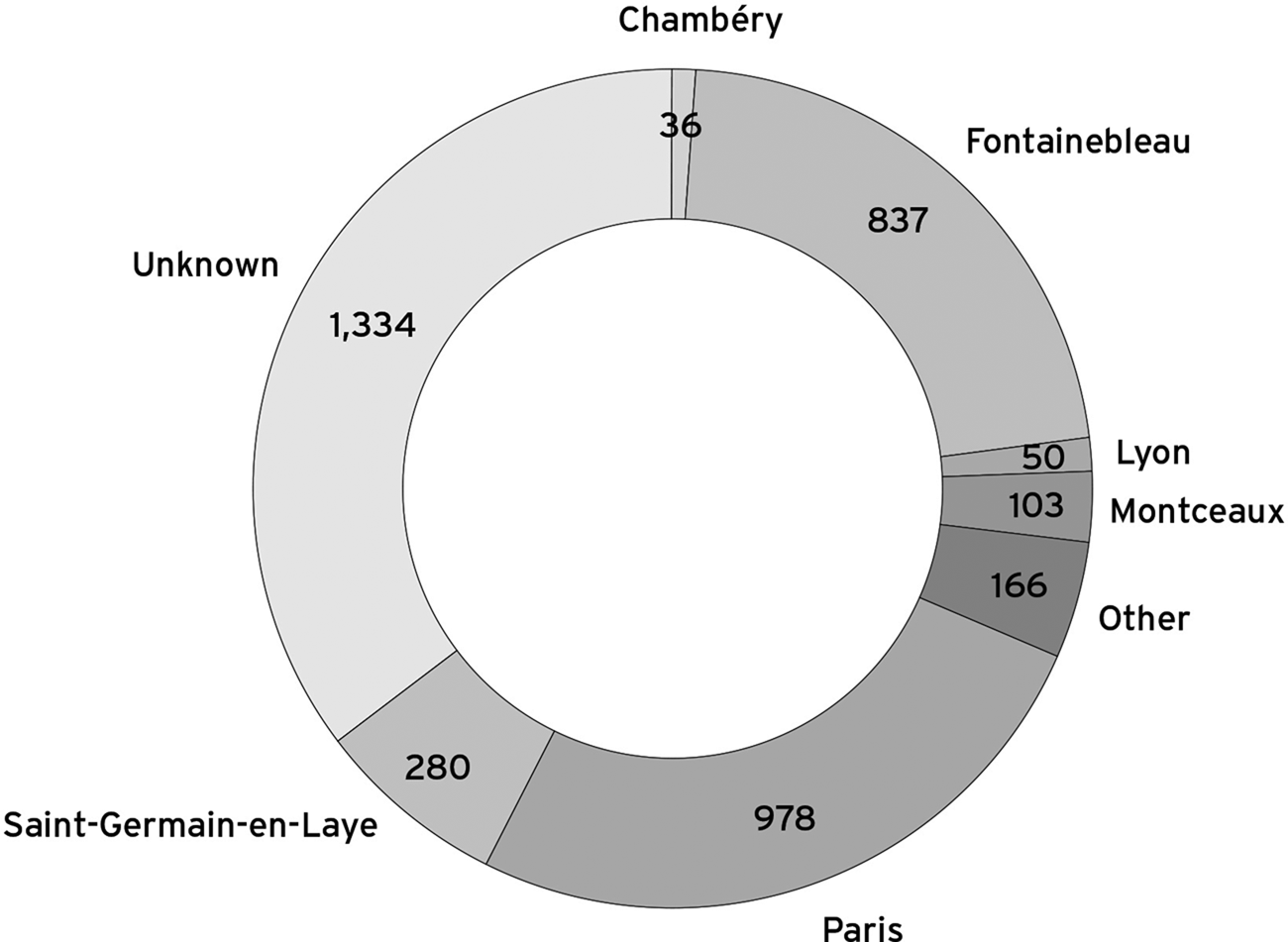

Analysis of Henri IV's itinerary also demonstrates a strong preference for Fontainebleau, Paris, and Saint-Germain-en-Laye in the years following his 1600 marriage.Footnote 58 The king's itinerary, published with his letters by Jean-Claude Cuignet in 1997, provides a glimpse—partial though it is—into Henri IV's movements. The data provided by Cuignet's published itineraries, once cleaned and plotted on an interactive ArcGIS map, visualizes what at first appears to be the impressive geographic scope of Henri IV's travels (fig. 3). This map is designed to show the relative frequency with which the king visited each region.Footnote 59 Yet singular events had provoked the king's visits to many of these locations. After nominally conquering his realm, the king continued to travel for military purposes; the Franco-Savoyard War of 1600–01, for example, took him to Lyon and Chambéry. Even after accounting for these extended voyages, Henri IV spent a remarkable 86 percent of the dates for which his itinerary is known at the three Île-de-France residences named above. A graph created in the data visualization program Tableau to represent this information must be interpreted in tandem with the map, as the former shows the relative frequency with which Henri IV visited each location as well as demonstrating the number of days for which no data is currently available (fig. 4).Footnote 60 Even in the absence of richer information, reading the map and graph together makes it possible to conclude that the king spent a great deal of his time at the Louvre, Fontainebleau, and Saint-Germain-en-Laye. The same phenomenon is apparent in the itineraries of other members of the royal family. While young princes and princesses usually traveled independently of the adult court, their spatial upbringing informed their later sociopolitical relationships, and the dauphin's itinerary should be understood as a corollary to his father's. In a break with the conventions of the last Valois, Henri IV's dauphin, Louis, principally resided at Fontainebleau and Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Under François I and Henri II, the royal children had frequented Saint-Germain but only rarely lodged at Fontainebleau or in Paris, preferring instead the safe distance and healthy airs of the Loire Valley.Footnote 61 In addition to responding to practical concerns, Henri IV's decision to raise his children at these residences suggests that he wished to associate his heirs with particular buildings and the monarchs who had built them. The pronounced changes in the royal family's itineraries at this point in history mark a comprehensive shift in the monarchy's manner of occupying its realm.

Figure 3. Map of Henri IV's itinerary, 1600–10. Author's diagram.

Figure 4. Graph with Henri IV's itinerary, 1600–10. The Other category includes locations at which the king spent fewer than twenty days total during this period. Author's diagram.

Against a backdrop of the French monarchs’ historically close proximity to their subjects, Henri IV's removal to the Île-de-France radically transformed the space of royal power. This was potentially problematic, since, as described above, a central goal of royal travel was to curate personal relationships and strengthen subjects’ perception of closeness to the sovereign. Henri IV's diminished personal presence in the provinces thus required a substitution—a way to fortify loyalties that was grounded in representations rather than frequent face-to-face contact. Political remedies like the burgeoning intendant system and reconfigured clientage relationships sought to address the evolution of governance caused by the monarchy's diminished itineraries.Footnote 62 As complements to these solutions, images like those in the Galerie des Cerfs memorialized a network of residences that had largely ceased to serve a practical function. The portrayal of residences—most of which Henri IV and his family rarely or never visited—in the Galerie des Cerfs emphasized the king's ties to dynastic history and visualized his control over French territory in a way that had previously been accomplished through travel.

THE ARCHITECTURAL SETTING

The complexity of Fontainebleau's plan is the result of its enduring prominence in the life of the French royal family. Though the chateau's earliest origins are medieval, monarchs continued to demolish, renovate, and expand the site through the sixteenth century.Footnote 63 Following in this tradition, Henri IV erected the Galerie des Cerfs on the ground floor of a new building adjacent to the oval court. The building was finished by January 1600.Footnote 64 Shortly thereafter, he commissioned his Peintre Ordinaire (Principal Painter in Ordinary), Louis Poisson, to decorate the gallery with a series of mural maps representing a selection of royal residences, their parks, and nearby villages, work the artist completed by 1608.Footnote 65 Galleries were common in early modern French chateaux. Their oblong shape made them an ideal “place to stroll”—to use the words of architect Sebastiano Serlio (1475–ca. 1554)—and offered the royal family a space for indoor exercise and visits with guests.Footnote 66 These spaces’ long walls lent themselves to expansive painting cycles that could capture the attention of those who entered. As Fontainebleau expanded, its galleries had multiplied: François I constructed the gallery which is now named after him as well as the Galerie d'Ulysses.Footnote 67 Henri IV's addition of a gallery complex in the chateau's northern quadrant was a spatial answer to his predecessor's architectural and political reputation.Footnote 68

The Galerie des Cerfs was part of Henri IV's expansion of the chateau's eastern and northern extremities.Footnote 69 Since the reign of François I, the king's apartment at Fontainebleau had migrated from the Pavillon de Saint Louis in the oval court to the Pavillon des Poêles, finally returning to the donjon under Henri IV.Footnote 70 Abutting Henri IV's quarters to the east were Maria de’ Medici's apartments, from which the Galerie de la Reine extended to the north.Footnote 71 The Galerie des Cerfs sits directly below this gallery on the ground floor. Extensive reconstruction of the existent oval court apartments was necessary to position the superimposed galleries at a harmonious angle with the irregular donjon.Footnote 72 The new galleries’ location placed them firmly within the royal domain, even though they were accessed independently. As a residence, Fontainebleau performed royalty by housing ceremonies along with a revolving cast of courtiers and household staff. Because the chateau served these multifarious functions, its spaces were routinely altered to address the royal family's evolving needs; nonetheless, the monarchs’ apartments held exceptional significance since they indicated the physical presence of the king and queen. With other buildings commissioned by Henri IV—the Orangerie and the Galerie des Chevreuils—the Galerie des Cerfs formed an enclosed courtyard near the royal apartments, now known as the Jardin de la Reine.Footnote 73 Analyzing the politics inherent to Henri IV's collecting activities, Delphine Trébosc describes this entire complex and the objects it housed as a conscious effort to laud the peace won by Henri IV and his “inscription in monarchical continuity [and,] in this way, the legitimacy of his sovereignty.”Footnote 74 With the hunting trophies and artworks Trébosc analyzes, the Galerie des Cerfs depicted a global vision of Henri IV's domination of France's land, people, and the past.

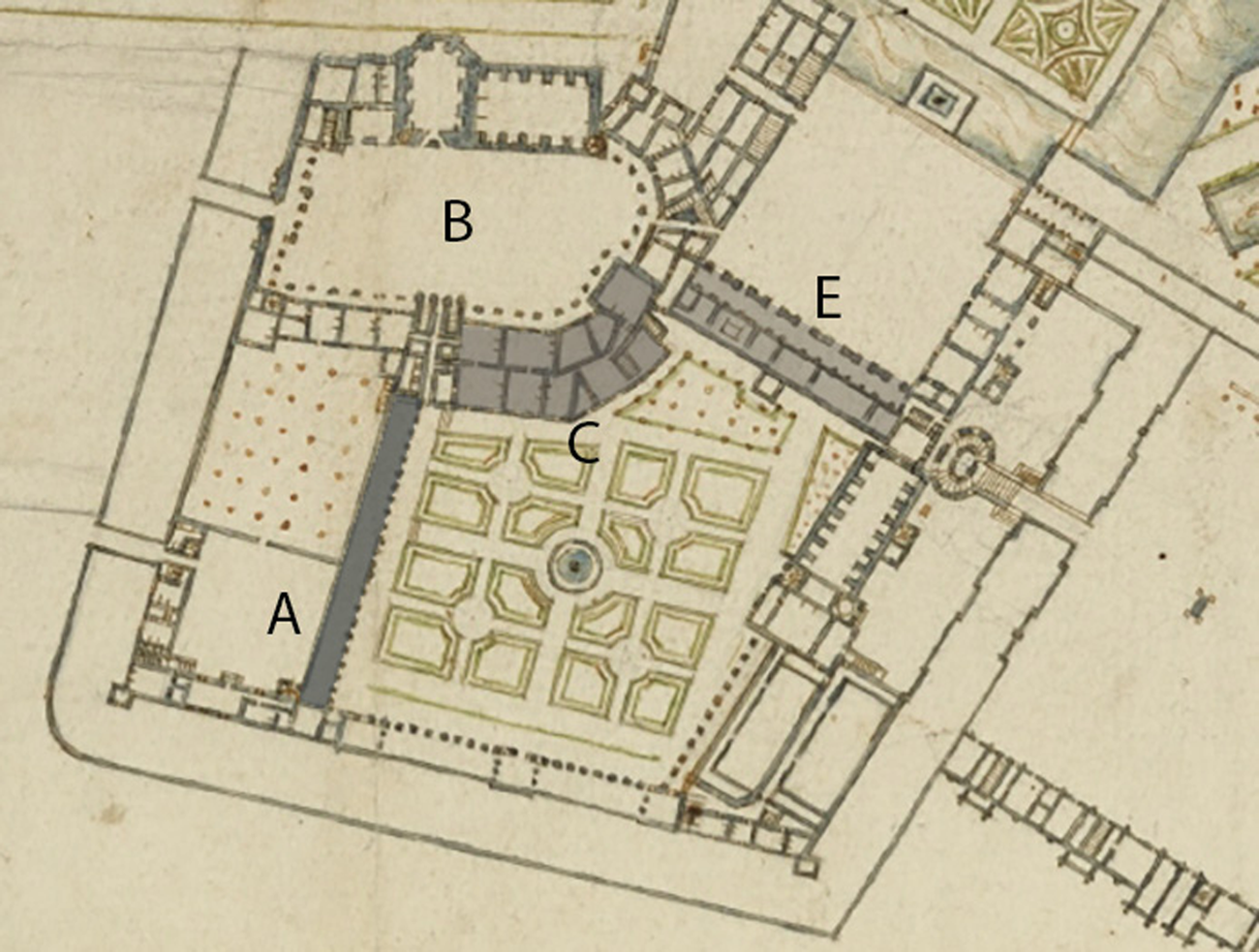

The Galerie des Cerfs may have been inspired by an eponymous space at Blois, a residence that Henri IV rarely visited but that nonetheless had dynastic significance, having entered the royal domain with Louis XII's succession in 1498. As at Fontainebleau, Blois's gallery extended from the royal apartments to the chateau's gardens, and both its decor and its architecture linked it to nature.Footnote 75 A plan conserved at the National Museum of Stockholm shows that one would have accessed the Galerie des Cerfs via the garden, which in turn could be entered from the oval court or a stairway that led down from the king's cabinet on the first floor (fig. 5).Footnote 76 Compared to the Jardin de la Reine, the oval court was a more public space that the royal family employed for ceremonies, including the baptism of the dauphin and his sisters in 1606.Footnote 77 Lacking an ostentatious entryway like the oval court's Porte du Baptistère, the gardens were further removed from the heart of activity in the donjon. Visiting in 1625, Cardinal Barberini's (1607–71) legate referred to it as a “secret garden.”Footnote 78 While the precise meaning of this phrase is unclear, it suggests that the space was less accessible than Fontainebleau's other courtyards. The gallery's distribution, however, indicates that access was not restricted solely to the monarchs.Footnote 79 Although the royal apartments overlooked it, they did not communicate internally with the Galerie des Cerfs. Since both monarchs’ suites included separate galleries, the Galerie des Cerfs was a third space that expressed a conception of dynastic monarchy that was intimately tied to the French landscape (of which the adjoining Jardin de la Reine was a microcosm) and to the Crown's architecture, with Fontainebleau situated at its symbolic heart. In early modern France, gardens formed an essential component of daily and ceremonial life for the monarchy. One need look no further than Du Cerceau's prints and drawings to comprehend the centrality of natural spaces in the planning and occupation of royal architecture. Henri IV expanded upon this tradition, creating the Jardin de la Reine as well as Fontainebleau's Grand Canal and the grottoes and terraces of Saint-Germain-en-Laye's Château Neuf.Footnote 80

Figure 5. Claude Mollet. Plan of Fontainebleau, before 1609. Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, Tessin-Harleman Collection (NM THC) 23. Author's diagram. © Nationalmuseum. A. Galerie des Cerfs; B. Donjon court; C. Royal apartments; E. Galerie François I.

Despite their exclusion from the line of succession in France, dynastic success depended on women to bear heirs, expand the Crown's territory through the territories they brought to their marriages, and to serve, when necessary, as regents for their minor sons.Footnote 81 Maria de’ Medici's role as mother of the Bourbon line, the proximity of the gallery to her apartment, and the Florentine precedents for the gallery's mural maps, suggest that the queen was critical to the form and meaning of the Galerie des Cerfs. As the daughter of Grand Duke of Tuscany Francesco de’ Medici (1541–87) and Archduchess Joanna of Austria (1547–78), Maria's pedigree advanced France's diplomatic and financial relationships in the Italian peninsula. Poisson set his paintings in trompe l'oeil frames and bordered them with painted architecture that featured both the king and queen's initials.Footnote 82 The union of the two monarchs’ insignia, a decorative tradition in France, can also be found in Fontainebleau's Porte du Baptistère, which commemorated the dauphin's baptism. The presence of intertwining emblems in these two dynastically significant spaces underlines Maria's role in the Bourbon dynasty.Footnote 83 When she arrived in France in 1600, Maria brought with her the knowledge of contemporary Florentine map cycles and an astute comprehension of art's political potential.Footnote 84 The Medici had long employed painted maps to communicate domination of land or geographic knowledge.Footnote 85 Maria's grandfather, Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519–74), had commissioned a cycle of maps representing the earth and cosmos for the Guardaroba Nuova at the Palazzo Vecchio, where he housed his Wunderkammer, itself a visualization of intellectual authority.Footnote 86

Even more closely related to the Galerie des Cerfs in both subject and style were the seventeen lunette paintings depicting the Medici villas created by Flemish painter Justus van Utens (d. 1609) between 1599 and 1602. Commissioned by Maria's uncle, Ferdinando I (1549–1609), Utens's cycle adorned a sala (sometimes called the Room of the Cities) at the newly constructed Villa di Artimino.Footnote 87 Like Utens, Poisson rendered most of the residences from a cavalier perspective with careful attention to architectural detail and the surrounding landscapes. The smaller format and higher placement of the Villa di Artimino paintings required the painted edifices to be proportionately larger than those at Fontainebleau, yet the two cycles evidence similar impulses: to visualize a family's architectural grandeur and the corresponding accumulation of territorial power. By the time Maria departed Florence, the Artimino project was underway and the queen corresponded regularly with her Italian confidants throughout her reign. The number of portraits of Maria and Henri IV in the archives of the Guardaroba Medicea at the Archivio di Stato of Florence attest to the bidirectional cultural exchange that existed between the two states.Footnote 88 As the mother of the Bourbon dynasty, Maria de’ Medici was invested in its legitimation as a source of honor for her family and an assurance of stability for her children. The coincidence of her arrival in France and the commission makes it likely that Utens's cycle inspired the Galerie des Cerfs and it is possible that the queen contributed in some way to its planning. The gallery's proximity to the royal quarters, similarities to Florentine models, and occurrence around the time of Henri IV's second marriage indicate its role as a statement about royal dignity's endurance and the new king's place in French history.

THE PAINTING CYCLE

The name of the Galerie des Cerfs refers not to Poisson's paintings but, rather, to the forty-three mounted stags’ heads that lined its walls.Footnote 89 Although dangerous, the stag hunt was a noble sport in which the monarchs performed their physical prowess and asserted spatial as well as social domination.Footnote 90 For this reason, stags figured prominently in the coats of arms of Charles VI (r. 1380–1422), Louis XII, and the dukes of Bourbon.Footnote 91 Fontainebleau's history was intimately tied to hunting and, according to Père Dan's 1642 guidebook, the residence had developed in part because of its proximity to game-rich forests.Footnote 92 The inclusion of hunting trophies accentuated the gallery's claims about Henri IV's connections to royal history. In his discussion of the space, Dan identified the stags by their provenance, tracing them to monarchs such as Charles VI, Henri IV, and Louis XIII (r. 1610–43).Footnote 93 The Valois kings—including Henri II and Charles IX (r. 1560–74)—had also played a part in assembling the collection.Footnote 94 While many of the residences painted in the Galerie des Cerfs were hunting retreats, this was not universally true and even in cases like Chambord, the identity of the residences was not solely or even primarily characterized by the hunt. Instead, the hunt was one aspect of a complex decorative cycle that was more deeply concerned with royal architecture and French history.

As in the seventeenth century, visitors entering the Galerie des Cerfs today face the expanse of the long eastern wall. Here, eleven paintings show buildings in the Île-de-France and the other traditional regions of the monarchy's residency: the Loire Valley and Picardy (fig. 6).Footnote 95 Moving through the gallery from north to south, these include Folembray and Coucy, Compiègne, Villers-Cottêrets, Blois, Amboise, Chambord, Saint-Léger, Charleval, Montceaux, Verneuil, and the chateau of Madrid. These chateaux vary dramatically in style, location, size, and history but are unified through their references to the kings with whom Henri IV wished to associate himself.Footnote 96 Louis IX had either built or inhabited at least five of the residences, while nine of the seventeen edifices offered explicit connections to François I. Henri IV had recently acquired two of the buildings: Montceaux—once the property of Catherine de’ Medici—which he repurchased for the Crown in 1594, and Verneuil, which he procured in 1599.Footnote 97 The inclusion of these two buildings in the gallery cycle inserted the first Bourbon into a visual history of royal architecture. In this way, the gallery visualizes Henri IV's pronouncement to Parlement on 7 January 1599, when he proclaimed that the kingdom was his “by heritage and by acquisition.”Footnote 98 Though ostensibly referring to the macrocosm of the realm, this statement likewise applies to the Crown's built environment, which, I argue, marked and molded French territory. The buildings painted in the gallery were thus not mere monuments; they had long functioned as seats of power from which the monarchy governed. Their assembly at Fontainebleau visualizes an enduring network of territorial and social power.

Figure 6. Location of paintings in the Galerie des Cerfs. Author's diagram.

Like Alberti's and Ligorio's views of Rome, the Galerie des Cerfs envisioned a kingdom whose grandeur derived from the continuity of past and future glory as embodied by the built environment. The inclusion of the chateau of Charleval is particularly revelatory of this strategy. Begun by Charles IX on a plot of land in Normandy, the building was not completed and almost never occupied. By the early seventeenth century it was largely abandoned.Footnote 99 In addition to adding a historicizing veneer, Charleval's crumbling appearance provided a critical link to the last Valois and pointed to Henri IV's reestablishment of French prosperity in the wake of civil war.Footnote 100 A century later, the gallery's success in evoking a specific version of the royal past is evident in Pierre Guilbert's Description historique des chateau, bourg et forest de Fontainebleau (Historical description of the chateau, village, and forest of Fontainebleau, 1721). In his discussion of Poisson's paintings, Guilbert narrates each building's history, connecting the images to the Gauls, Clovis, and Charlemagne, as well as to Henri IV's immediate predecessors and heirs.Footnote 101 This circle of associations linking past and present to the future embodies the propagandistic political narrative inherent in the Galerie des Cerfs.

In connecting his reign to France's network of royal residences, Henri IV drew on a long-standing artistic tradition. Buildings were understood in relation to their residents, and this symbolic association had assumed visual form from the medieval period on. In addition to Les plus excellents bastiments de France, the manuscript illuminations now known as the Très riches heures (The very rich hours, begun ca. 1412) include edifices tied to the volume's patron, the Duke of Berry (1340–1416), who had wrestled with his power relative to that of the throne throughout his life.Footnote 102 A lesser-known document from 1460 at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS fr. 4991, visualizes the connection between individuals and architecture even more explicitly. Its pages present a genealogy of the French monarchs that pairs royal portraits with buildings associated with each king's reign: Philippe Auguste, for instance, is shown alongside the chateau of Vincennes. In such examples, the artist employed buildings—primarily prominent churches and other religious edifices—to construct a map of France, completing the trinity of associations between ruler, architecture, and the kingdom that was essential to securing the peace in the period immediately following the dynastic tumult of the Hundred Years’ War.Footnote 103 Henri IV's adaptation of such visual models in the Galerie des Cerfs addressed a similarly disruptive moment for royal authority.

The gallery's current state is the result of a long history of destruction and renovation. Following an early restoration by Poisson's grandson, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Louis XV (r. 1715–74), Louis XVI (r. 1774–92), and Napoleon I (1769–1821) expanded and partitioned the space to accommodate additional apartments.Footnote 104 Later, Napoleon III (1808–73) undertook work to return the space to its original state.Footnote 105 Some of the paintings, including the chateau of Madrid, were well preserved during this process while others, like Charleval, were discovered in a sorry state of disrepair.Footnote 106 The architect charged with the project, Alexis Paccard (1813–67), seems to have thoroughly researched the restoration project.Footnote 107 Although the nineteenth-century interventions mediate modern understanding of the cycle, certain facts—principally the identity of each building and the overall schema of each layout—allow one to understand the murals’ content. Most of Poisson's paintings deploy cavalier perspectives in which some buildings are shown in profile, a solution similar to the representation of architecture in maps created by Henri IV's Géographes et Ingénieurs du Roi.Footnote 108 Each of the panels centers on a chateau, which is usually positioned in the bottom half of the frame where its details could be legible to viewers. Except for the Louvre and Vincennes, which use a different format, the buildings occupy only a small portion of each painting. The remaining spaces reveal the villages, religious edifices, and natural landscapes that surrounded the chateaux. Poisson carefully renders the sprawling gardens, fields, and forests of the countryside as well as the roads and rivers that connect them, listing their names in accompanying white cartelline (banners). Naming these sites contributed to the maps’ ability to express the king's domination: through their appearance in the gallery's maps they are cataloged as Henri IV's possessions.Footnote 109

Additional labels inside trompe l'oeil cartouches furnish the name of the chateau and note the total size of its park or forest. These measurements give an impression of the royal domain's vastness; Fontainebleau contained nearly 26,000 arpents, with one royal arpent equivalent to approximately half a hectare. The roads and waterways suggest movement between the buildings and invite the viewer to visually link the paintings. The distance and path from one chateau to another were crucial for planning itineraries, ceremonies, and military maneuvers. In Les plus excellents bastiments de France, Du Cerceau consistently references the distance between royal and noble residences in the texts that accompany his prints, describing Saint-Germain as “five leagues from Paris,” for instance.Footnote 110 Given the first Bourbon's diminished itinerary, the importance of distance as a symbolic expression of the geographic reach of the Crown's authority increased.

The short ends of the gallery feature the chateaux of Fontainebleau (fig. 7) and Saint-Germain-en-Laye. As his itinerary shows, Henri IV spent much time at these two residences due to their strategic locations, ample interiors, and historical importance. Critical to the narratives of continuity and territorial domination embedded in the Galerie des Cerfs was its location at Fontainebleau, a residence that had, even by the early seventeenth century, come to serve as a palimpsest of royal history.Footnote 111 As at Fontainebleau, at Saint-Germain-en-Laye François I constructed a new edifice atop existent foundations, physically wedding his reign to the past. The new structure was designed to highlight the Gothic chapel of Louis IX, which it embraces while simultaneously leaving the chapel visible from both the street and the courtyard.Footnote 112 Henri IV further expanded the residence, building the now-destroyed Château Neuf overlooking the Seine just two hundred meters to the east of the older chateau.Footnote 113 In doing so, he completed a project originally undertaken by Henri II before his death. With this addition, the king created a site capable of comfortably housing the entire royal family and court according to the specific needs of each constituency, just as he had done at Fontainebleau and the Louvre. Du Chesne emphasizes Saint-Germain's medieval origins and François I's interventions, but ultimately he credits Henri IV with having “rendered this maison of his predecessors truly Royal” through the architectural and engineering feats he narrates at length.Footnote 114 Du Chesne describes Saint-Germain's ancient history as central to its meaning, aligning Henri IV's reign with the past through his architectural accomplishments and continued use of the historical spaces.

Figure 7. Louis Poisson. Fontainebleau, ca. 1608. Galerie des Cerfs, Fontainebleau. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

The pairing of Fontainebleau and Saint-Germain-en-Laye in the Galerie des Cerfs recurs in another painting cycle that Henri IV commissioned from Poisson later in his reign.Footnote 115 In a gallery at the Château Neuf, Poisson depicted twenty-two maps of world cities ranging from Mantua to Aden in present-day Yemen.Footnote 116 Among these places, Poisson included Fontainebleau, positioning it alongside the metropolises of Italy and the Holy Roman and Ottoman empires and elevating its status by association.Footnote 117 This space mirrored a second gallery decorated with paintings that portrayed Henri IV as Francus, the heroic founder of France in Pierre de Ronsard's Franciade (1572).Footnote 118 Similarly to Fontainebleau's new superimposed Galerie des Cerfs and Galerie de la Reine, at Saint-Germain-en-Laye the new galleries were built adjacent to the royal apartments and their architecture and décor were closely allied to the monarchs’ identities. The Saint-Germain-en-Laye cycle expressed Henri IV's imperial ambitions and, when juxtaposed with the epic that Ronsard had penned for Charles IX, further linked the king's territorial concerns to dynastic strategies.Footnote 119

Poisson's visual quotation of the Galerie des Cerfs on its own walls completed a chain of references that centered on architecture as a defining aspect of Crown and kingdom. A precedent for this conflation of architecture and authority can be found in Fontainebleau's Galerie François I. Here, a diminutive stucco-framed fresco representing the chateau's Porte Dorée adjoins a painting of Fontainebleau Nova Pandora and wood panels featuring François I's arms, emblem, and initial.Footnote 120 This earlier example likely influenced Henri IV's commission of the Galerie des Cerfs, which argued for legitimacy through domination of royal history rather than the mythical past presented in the Galerie François I. Lurin has pointed out the discursive similarities between Fontainebleau's galleries and the Bourbon king's commission of the Louvre's new Petite Galerie, which was adorned with the king's portrait and those of his predecessors.Footnote 121 Writing on French history in 1605—likely with the Galerie des Cerfs in mind—De Laval expressed his “surprise that [François I] had not somewhere depicted his beautiful palaces, a subject proper and particular to his predecessor kings and to himself.”Footnote 122 Henri IV took up exactly this subject, playing on the associations between the concept of dynasty and the built environment that were so clear to Laval. The spatial primacy accorded to Fontainebleau and Saint-Germain in the Galerie des Cerfs supported the establishment of two residences as poles of Henri IV's itinerary and as central actors in his performance of dynastic history.

A second pair of complementary residences flank the entrance to the Galerie des Cerfs: the Louvre (fig. 8) and the chateau of Vincennes. Because of their location on the wall of windows facing the courtyard, these paintings have a different format than the others: they are square, the edifices are proportionally larger, and the frames are cropped more closely around the buildings, revealing less of the surrounding landscape.Footnote 123 Like the Fontainebleau–Saint-Germain dyad, this pairing visualized Henri IV's spatial relationship to the Capetians and Valois. Louis IX and François I had built at both sites and periodically inhabited them. Since the reign of Philippe Auguste, the Louvre had been an important royal landmark within Paris, even if it was inconsistently occupied. François I renovated the old fortress, as did Henri IV, slowly shifting its function from fortification to residence.Footnote 124 Located east of Paris, Vincennes had once served an analogous defensive role. Henri IV visited Vincennes only sporadically, but perhaps because of its proximity to Paris and his desire to connect his own reign to that of his predecessors through architecture, he also initiated renovations there.Footnote 125 Lurin views the pairing of Vincennes and the Louvre as an effort to suggest a parallel between Henri IV's architectural pursuits and those of his ancestor, Louis IX.Footnote 126 This dynastic link is certainly crucial to the selection of these two edifices, as is their location in the Île-de-France. Louis IX and François I's primacy in French history rested on their early modern reputations as just rulers, defenders of the faith, and champions of the arts, traits with which Henri IV also hoped to identify. The spatial distinction accorded to the Vincennes-Louvre and Fontainebleau–Saint-Germain pairs asserted the Île-de-France region as well as Henri IV's predecessors, Louis IX and François I, as the historical and dynastic foundations of Bourbon authority.

Figure 8. Louis Poisson. Louvre, ca. 1608. Galerie des Cerfs, Fontainebleau. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

The Galerie des Cerfs was conceived in dialogue with the adjacent Jardin de la Reine. The length of the gallery's western wall consists of bays of large mullioned windows that open onto the garden, allowing visual continuity between Poisson's landscapes and the outdoors. While traversing the Galerie des Cerfs, one's eye moves between painted nature on one side and real flora on the other. The cultivation of gardens was one way early modern rulers exercised control over their land: because these spaces molded unwieldy nature into contained forms, well-kept gardens symbolized good government.Footnote 127 At Fontainebleau, this concept was reinforced in the visual prominence attributed to landscape in Poisson's paintings, which depict royal buildings as deeply embedded in their natural surroundings. By visually associating the gardens with the broader French kingdom, the Galerie des Cerfs communicated the geographic extent of Henri IV's power. Through its association of nature with architectural prestige and political power, the gallery appealed to the naturalness of the Crown's territory, painting the king's authority as innate.Footnote 128

In earlier areas of Fontainebleau like the Galerie François I and the chamber of the Duchesse d’Étampes, decorative cycles linked nature and abundance to signal the realm's prosperity.Footnote 129 In these spaces, the iconography of fruit and foliage alluded to nature's feminine connotations and associations with fertility, a subject at the heart of dynastic stability. The productivity of French lands and the monarchy's fecundity are likewise conflated in the Galerie des Cerfs, where the fruits of centuries of architectural labor are pictured alongside the realm's verdant landscapes. By placing France's rich landscapes in relation to the Crown's traditional residences, Henri IV deepened the epistemological correlation between nature and nation that Rebecca Zorach identifies at sixteenth-century Fontainebleau.Footnote 130 The concepts of abundance and fertility were of heightened significance at the dawn of the seventeenth century. Henri IV had ascended the throne following the unexpected deaths of his three Valois predecessors without male heirs. The king's own twenty-seven-year first marriage to Marguerite de Valois (1553–1615) likewise failed to produce children. After more than fifty years without the birth of a dauphin, the arrival of Henri IV and Maria de’ Medici's son Louis in 1601 assured the Bourbon line's survival and was perceived as a sign of its divinely ordained legitimacy. Following this momentous event chronologically, the Galerie des Cerfs referenced the physical inheritance the dauphin would one day receive and historicized the bourgeoning dynasty's ties to the Capetians and the Valois.

Through its architectural and dynastic references, the Galerie des Cerfs returns the viewer to Fontainebleau and its royal patrons. In doing so, the paintings invited participation; guests recognized the building in which they stood and felt themselves present at the heart of royal power and, ideally, complicit in its propagation. Henri IV used Fontainebleau to receive prominent guests: Du Chesne describes it as the chateau where the king “most often [gave] audience to the ambassadors of foreign princes.”Footnote 131 According to Dan, the standard visit to Fontainebleau began in the Concierge and moved immediately to the Galerie des Cerfs, perhaps because of the way it situated the chateau in French architectural history.Footnote 132 Tuscan diplomat Camillo Guidi and the entourage of Spanish ambassador Pedro de Toledo Osorio (1546–1627) both reported on tours of Fontainebleau that were conducted by Henri IV himself.Footnote 133 Don Pedro commented specifically on the king's ability to discuss every painting inside.Footnote 134 Under Henri IV's descendants, the space would also host banquets, such as those for Charles Stuart, the Prince of Wales (1630–85), in 1646—a purpose for which it is well configured and which it continues to serve today.Footnote 135 During such encounters, the images in the Galerie des Cerfs allowed the monarch to demonstrate his knowledge of the realm and its history, architecture, and peoples while simultaneously inserting himself into the narrative. This educational function worked equally well for members of the royal family. In 1608, the six-year-old dauphin recognized the residences in which he lived among those in the gallery, exclaiming, “There is the Louvre, which is in Paris, it is Paris that is my mignon [darling],” and also, according to his doctor Jean Héroard (1551–1628), “recognized Saint-Germain-en-Laye with enthusiasm.”Footnote 136 These informal lessons indoctrinated the young prince into his father's spatial regime while instructing him about his ancestors. In his text on the instructive possibilities of gallery décor, De Laval described the ancient precedents for such didactic imagery, noting that “the ancients . . . wanted those of their century to receive instruction and utility [from this décor] as well as posterity after them.”Footnote 137 The question of who else may have had regular access to the Galerie des Cerfs remains. Héroard reported, for example, that the dauphin occasionally played in the space; additionally, a vast range of courtiers, servants, and visitors could enter spaces within the chateau, a fact that may surprise modern visitors.Footnote 138 For those who did have the opportunity to view it, the iconography, architecture, and functions of the Galerie des Cerfs provided a cohesive vision of the Bourbon dynasty's continuity with the past. Through spatial and architectural references to his predecessors, Henri IV announced himself as their heir.

As the royal residences painted by Poisson lost much of their practical value as destinations in the royal family's itineraries, they assumed an increased role in the monarchy's symbolic self-construction. Although Henri IV attended to the repair and maintenance of the buildings pictured in the gallery, itineraries reveal that he and his family occupied few of these edifices on a regular basis. The connection between the edifices’ appearance in the Galerie des Cerfs and the court's physical absence from their halls was not fortuitous. In its use of architecture to assert territorial control of the realm and narrative control of history, the gallery drew upon and functioned in concert with contemporary cartographic imagery to replace the royal itinerary with representations of it. Within this visual culture, the gallery was an index for dynastic continuity at a moment when juridical debates about the succession and foreign and domestic quarrels over the geographic limits of France reconfigured the royal family's spatial relationship to its subjects. Drawing on artistic precedents in France and abroad, Henri IV deployed visual territoriality in an effort to regain control over France's dispersed peoples and his own historical narrative.Footnote 139

ARCHITECTURAL NETWORKS: LIVED, PAINTED, PRINTED

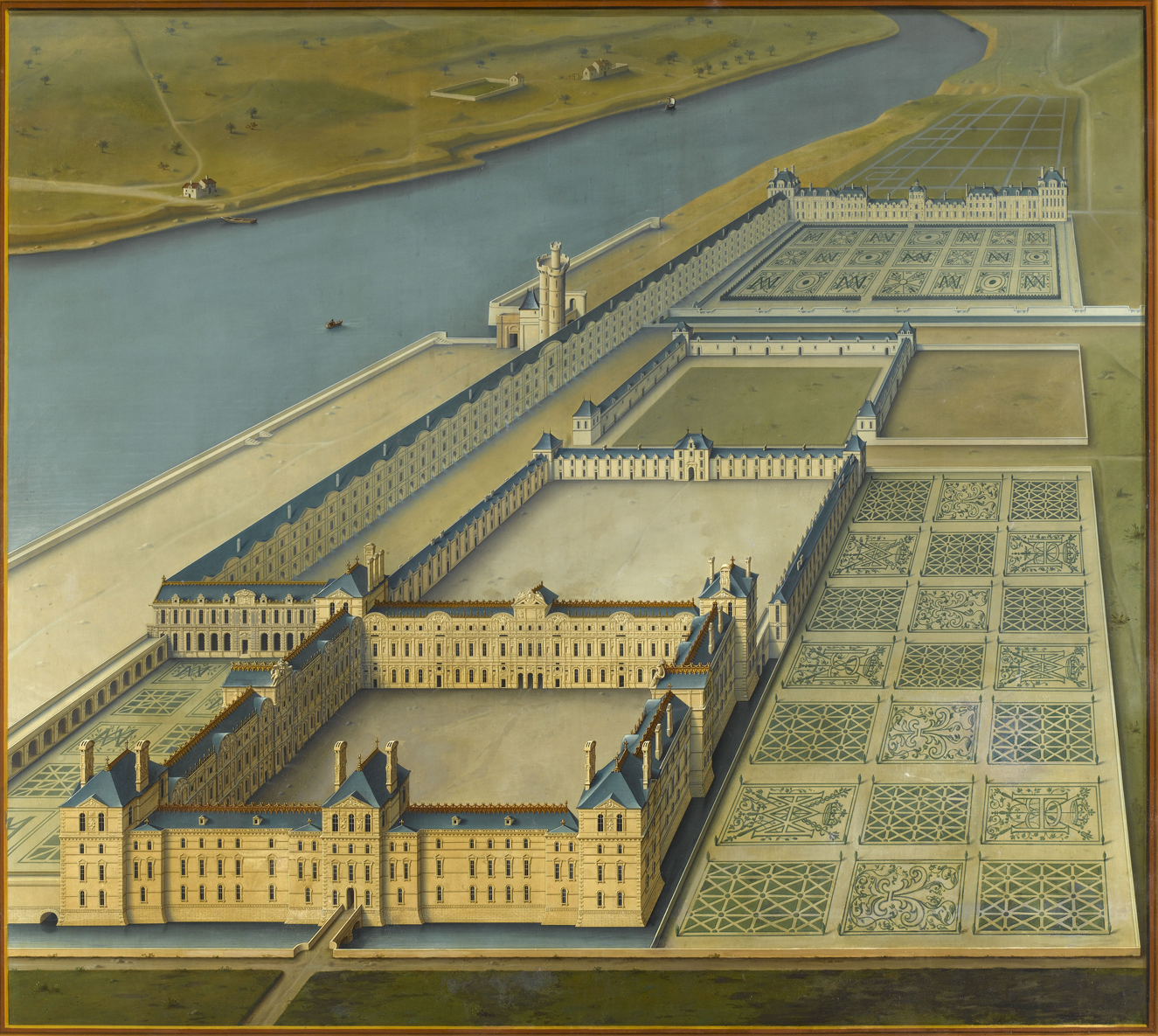

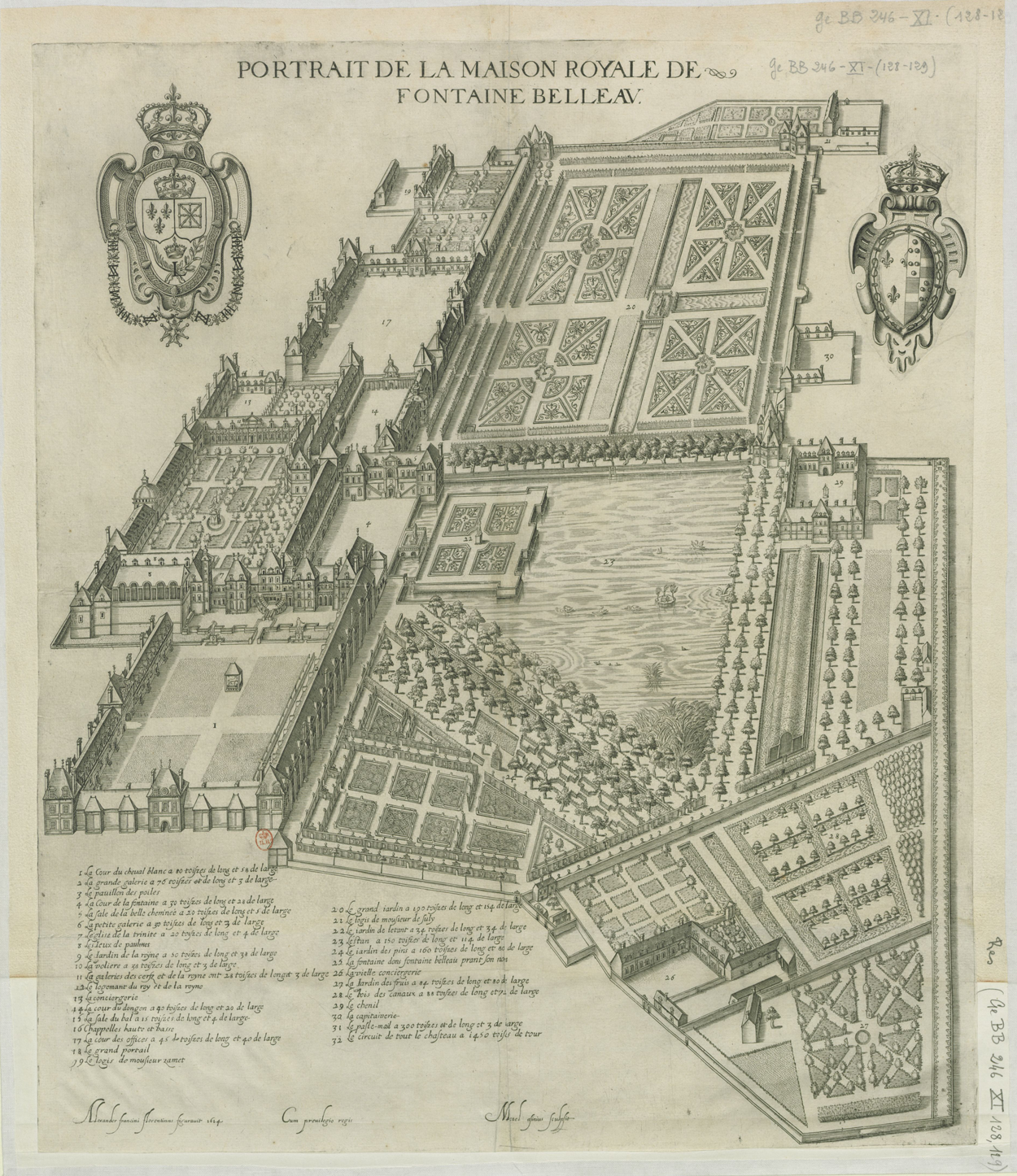

Printed maps and Poisson's paintings were oriented toward different viewers but they shared an objective, and print media allowed the gallery's iconography to circulate even more widely. Texts like Dan's and Guilbert's histories of Fontainebleau or the description of the chateau in Abraham Gölnitz's travel narrative Ulysses Belgico-Gallicus (1631) introduced a relatively broad audience to the cycle. Given the greater accessibility of images to a less educated public, however, printed images were even more effective in communicating royal ideals. The general principles of Poisson's map murals—detailed portraits of the residences in dialogue with the natural world, with an emphasis on Henri IV's interventions—were quickly translated into ink for this purpose. In 1614, four years after Henri IV's death, Alessandro Francini (d. 1648) made two drawings, known through engravings by Michel de Lasne (ca. 1590–1667), of Fontainebleau (fig. 9) and Saint-Germain-en-Laye. From a Florentine family, Francini was an engineer who Henri IV employed to work on Saint-Germain's grottoes and gardens, a position that afforded him access to the chateau's plans.Footnote 140 Francini's brother, Tommaso (1571–1651), also designed a hunting-themed fountain for the Jardin de la Reine, onto which the Galerie des Cerfs looked.Footnote 141 The engravings adopt the concept of the architectural portrait to print by portraying the buildings as more regular than they are in reality. This regularization is especially apparent in Fontainebleau's donjon court. Alternately called the oval court because of its irregular shape, the space is quadrilateral in Lasne's print, rendering the site more uniform and, therefore, more legible. Francini's images were evidently popular, and printmaker Abraham Bosse (1602–76) went on to reproduce them in Dan's book, which in turn was used as source material for Paccard during the nineteenth-century restoration.Footnote 142 By extending the territorial and dynastic arguments of the gallery to a more expansive audience, the engravings consolidated the identification of Fontainebleau and Saint-Germain-en-Laye as the royal family's homes and used architecture to ground the dynasty in legitimizing history.

Figure 9. Michel Lasne after Alessandro Francini. Portrait de la maison royale de Fontaine Belleau, 1614. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, GE BB-246 (XI,128-129RES). © Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The reappearance of Poisson's formula in Francini's drawings demonstrates that dynastic transition and the evolution of the monarchy's relationship to its architectural network could not be accomplished in a single reign. A narrative of continuity was of renewed importance during the early years of Louis XIII's rule. Henri IV's death and Maria de’ Medici's difficult position as a foreign, female regent left the new king's power vulnerable to the same noble infighting that had hindered his father's early reign. De Lasne's engravings pair Louis XIII's coat of arms with those of the queen mother, once again reaffirming the new regime's ties to the past through architecture.Footnote 143 If civic strife and war limited the monarchs’ ability to travel comfortably around their kingdom, the cultural weapons of cartography, art, and architecture furnished a partial remedy. These tools were revised throughout the long seventeenth century as the French court's itineraries continued to shift. Although modern histories focus heavily on Louis XIV's (r. 1643–1715) installation at Versailles, the court did not settle there until 1682, almost forty years into his reign. Until then, Louis XIV frequented the same Île-de-France residences as his father and grandfather.Footnote 144 The transformation of the monarchy's residential habits was a gradual, nonlinear process predicated on continual modifications of the sovereign's lifestyle as well as on domestic and international politics.Footnote 145 Notable among artistic responses to the model set forth in the Galerie des Cerfs is a set of tapestries produced by the Manufacture des Gobelins around 1680. Woven based on drawings by Charles Le Brun (1619–90) and alternately called the Mois or the Maisons royales, the much-reproduced series represented twelve royal buildings: Blois, Chambord, Fontainebleau, the Louvre, Madrid, Montceaux, Marimont, the Palais Royal, Saint-Germain-en-Laye (fig. 10), the Tuileries, Vincennes, and Versailles.Footnote 146 The media may have changed, but the tapestries’ use of architecture to visualize territorial rule and dynastic continuity descends directly from the Galerie des Cerfs.

Figure 10. After Charles Le Brun. Château Neuf de Saint-Germain-en-Laye from the Royal Houses, ca. 1676–80. Musée national du château de Pau, P.282. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

In commissioning the Galerie des Cerfs, Henri IV replaced the Valois kings’ strategy of physical presence with painted and printed images that redefined his connections to French history and territory. Though physically static, architecture's meaning is fluid and the symbolic associations and functional usages of royal buildings shifted over time. By this process—as well as their continual morphological changes—the residences portrayed in the gallery were living agents in the kingdom's sociopolitical life. As Henri IV's itinerary shifted, profoundly altering the Crown's spatial relationship to its realm, the king commissioned the Galerie des Cerfs as a chronological and spatial portrait of the royal family.