INTRODUCTION

Ornament guided the perception of the arts of sixteenth-century Antwerp and the Low Countries. It framed works both physically and conceptually, serving as a mechanism of hermeneutic regulation. It offered systems of order and ordering. This is most obvious in the well-known species of column types, known as the orders, which set antique architecture out in five basic categories: the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian (which are well known today), coupled with the Tuscan and Composite. A specific set of elements and proportions adhered to each one of these categories, but the five classes did not determine the appearance solely of columns; each category pertained to a much larger system of architecture defined by ornament that included interior furnishings, such as mantelpieces, and entire facades. Nor did the system of classification stop here. Hans Vredeman de Vries (1527–1607) applied the orders to garden design, designating ideal layouts of gardens as Ionic, Doric, Corinthian, and so on.

Casual readers often think of ornament as peculiar to classicizing culture, yet it was also critical to Pieter Bruegel (ca. 1525–69), Pieter Aertsen (1508–75), and other artists associated with local and contemporary idioms. Ornament cuts across the vernacular-classicizing divide, that binary model that has structured much discussion of Netherlandish art of this period.Footnote 1 One important ornamental invention, the strapwork cartouche, had neither an ancient precedent nor an Italian provenance, but was rather developed by artists in the Netherlands and France in the early modern era. It consisted of interlaced bands that originally resembled the curling edges of leather straps but soon simulated a great variety of materials. As a device, it bestowed weight and power to the text or image it framed and might paradoxically be termed a kind of vernacular classicism.

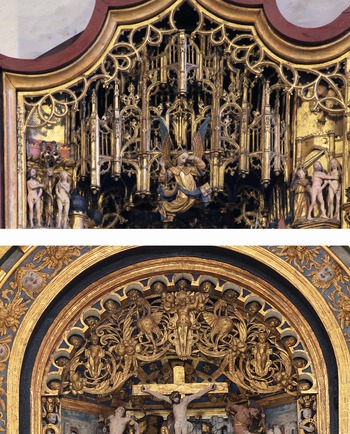

Bruegel was quite sensitive to the ability of ornament to signal values across media. Thus in his Adoration of the Magi of 1564, Bruegel decorates the robe of the aged, kneeling magus with finely painted, fictive embroidery (figs. 1–2). This seemingly recondite detail is more important than its size indicates, for it relates Bruegel's picture to classicizing tastes in the Netherlands, a trend rarely associated with the artist. The motifs on the hem point most directly to contemporary sculpture with its distinct formal conventions and social context. These motifs recall the narrow friezes that adorn the popular antique alabaster huisaltars (domestic altarpieces) produced so prolifically in Antwerp and Mechelen (figs. 3–4) and purchased by the nobility and upper bourgeoisie at home and abroad.Footnote 2 These works served both as altarpieces and as epitaphs; portraits of donors or the deceased could easily be affixed to their sides. The huisaltars were largely ornamental objects; putti, river gods, and nymphs, crowned by semicircular constellations, surround the religious narratives. These sculptures were among the most popular genres of the time. In fact, there arose a new category of sculptor, the cleynsteker (miniature carver), who was charged with executing the antique ornament in these dense works. Although scholars have related the decoration on Bruegel's gown to the legacy of ancient Rome, it is actually strikingly contemporary. Bruegel, intensely interested in the connotations of costume,Footnote 3 has adorned his magus with fashionable antique trim. It is a trope indicative of a much broader perspective on the arts. As ornament, and neighboring the grotesque, these motifs could function both as a sign of a distinct social class and as an index of boundless artistic invention.

Figure 1. Pieter Bruegel. Adoration of the Magi, 1564. London, National Gallery. Author's photo.

Figure 2. Pieter Bruegel. Adoration of the Magi, 1564, detail. London, National Gallery. Author's photo.

Figure 3. Mechelen artists. Domestic altarpiece, ca. 1550. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum. Author's photo.

Figure 4. Mechelen artists. Domestic altarpiece, ca. 1550, details of friezes. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, and Kalkar, Nicolaikirche. Author's photos.

To heirs of the modernist legacy of Adolf Loos (1870–1933) and Le Corbusier (1877–1965), ornament may sound extraneous to the essential demands of Netherlandish art. And many critics today tend to view ornament as a sort of cloying overlay of natural form. This is not solely a current prejudice; the sixteenth-century cosmographer Abraham Ortelius (1525–98) expresses similar reservations and categorically clears his friend Bruegel from this potential charge: “Painters who are painting handsome youths in their bloom and wish to add to the painting some ornament/allurement [lenocinium] and charm [gratium] of their own thereby destroy the whole character of the likeness, so that they fail to achieve the resemblance at which they aim as well as true beauty. Of such a blemish our friend Bruegel was perfectly free.”Footnote 4 The visual delight offered by ornament could be hazardous; to many it provided a distraction from the truth of a matter and was morally suspect. Particularly in Protestant Europe, ornament was considered dangerously seductive. “The world is still deceived with ornament,” warns one of the suitors in The Merchant of Venice when faced with the superficial attraction of gold and silver caskets.Footnote 5 Yet iconoclasts who objected to the representation of the human body could accept works composed solely of ornament: the architectural and abstract forms of Gothic and antique sculpture might be deemed safe and inoffensive. In 1601 the Amsterdam sculptor Hendrik de Keyser (1565–1621) ran into trouble of this sort with his memorial for the physician Petrus Hoogerbeerts in the Dutch town of Hoorn. A local crowd violently objected to Hoogerbeets's effigy, threatening to destroy the monument if the figurative sculpture was not removed. De Keyser complied.Footnote 6

An ascetic sensibility has long dominated these discussions in cultural studies. Early sixteenth-century art, replete in ornament, has frequently been disestablished through pejorative descriptors such as “overloaded,” “congested,” or “Mannerist.”Footnote 7 The noted British art historian Anthony Blunt spoke of the densely ornamented sculpture of early modern France as the expression of an “experimental spirit”—the premonition of a style not fully legitimate until its ornament was pruned and tamed through classicism.Footnote 8 And the Dutch scholar M. D. Ozinga applauded the “severe Renaissance style” that would endow Netherlandish sixteenth-century architecture with a new “purity” and redeem it from the copious and overabundant decorative tendencies that derived from an earlier Gothic mentality.Footnote 9 It is questionable whether recent discussions of ornamental “excess” adequately account for early modern practices.Footnote 10

Early modern attitudes to ornament, however, were frequently positive. During the mid-sixteenth century, Netherlandish artists devised strikingly new decorative devices and systems of embellishment. Indeed, ornament offers an illuminating register of artistic achievement, providing insight into a variety of practices and theories involving the leading painters of the Low Countries, while relating their medium to many others, including printmaking, sculpture, and architecture. Many members of Antwerp's cultural elite, including Bruegel and his learned and well-placed friend Abraham Ortelius, were intensely aware of ornament and its functions. Among others particularly attentive to the services of ornament were Maerten de Vos (1532–1603), Bruegel's traveling companion to Italy, and Frans Floris (1519/20–70), Bruegel's rival as one of the leading painters of the city. And there were many others: Cornelis Floris (1514–75), the brother of Frans and the leading sculptor in the Netherlands; and Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502–50), Bruegel's putative teacher and father-in-law, a designer of paintings, tapestries, and stained glass, and the leading architectural theorist in the Low Countries during the first half of the century. Both Aertsen and Joachim Beuckelaer (1533–74) referenced current architectural theory in many of their market paintings. This is also true of Vredeman de Vries, the painter of architectural tableaux and designer of architectural pattern books, who collaborated on at least one work with Pieter Bruegel and who executed the framing cartouches for Abraham Ortelius's famous album amicorum. Several artists designed series of prints devoted to ornamental patterns.

Such practices have been recently discussed as part of the continual realignment of art history. Ornament is once again current, much as it was at the end of the nineteenth century. During the past several years, it has been addressed in several important publications and examined from different perspectives and in different historical periods.Footnote 11 Yet it is notoriously difficult to define, both today and in the early modern era. The very nature and identity of ornament, for instance, was hotly debated in a Netherlandish court case in 1544. The Brussels joiner Mathys de Wayere (fl. 1506–44) had been hired by the Saint Gertrude Abbey in Leuven to make their choir stalls, a commission that entailed varied types of carving. As Angela Glover has shown, the dispute specifically addressed the statuettes and reliefs on the stalls. The Leuven masons’ guild insisted that only they, and not the joiners, were permitted to carve figures (beel[d]snyden). De Wayere and his fellow joiners answered that their carvings were not independent statues (beelden) but rather ornament (cyrate), integral to the stalls and within their compass.Footnote 12 The joiners prevailed; ornament was defined by its context, not its intrinsic properties. Here, as in most other instances, ornament was seen as relational, an enhancement or revision of something else primary to the discussion at hand.Footnote 13

Considerations of ornament frequently devolve into an analysis of its many functions, a stipulation of its “grammar,” and a tracing of the sources of specific motifs.Footnote 14 Ornament might be better understood as a series of related discourses around such notions as adornment, crafting, embodiment, beauty, fantasy, framing, and authority. It might further be comprehended as a system or systems regulating these values and properties. New words were coined for the concept in its various manifestations. Ornament performed many functions. Most obviously, it conveyed status; the word derived from the Latin ornoare, which could mean to honor or praise. Rich ornament could signify wealth and magnificence—of the subject or, by extension, of the patron. It could convey abundance, superfluity, and luxury. It could signal social caste and political agenda. By the seventeenth century, the linguistic link between Greek terms for adornment and the universe (kosmos-kosmetikos—related to the English cosmetic) allowed ornament to frame broader cosmographical inquiry.Footnote 15 Ornament showcased skill in fabrication of intricate and detailed objects or their representations. It might signal the virtuosity and materiality of finely crafted artifacts and could refer to other media. The gold vessels offered by the three magi in paintings by Jan Gossart (1478–1532) and Joos van Cleve (1485–1541) (fig. 5), for example, are so elaborate and elegant as to represent the epitome of the metalworker's art.Footnote 16

Figure 5. Joos van Cleve. Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1525, detail of left wing. Naples, Museo di Capodimonte. Author's photo.

Artistic mode could be indicated by ornament—allegiance to either the traditional Gothic system or to the newer antique, or Renaissance, practice, each with its own set of ideologies. It is easy to forget that cutting-edge works in the Gothic mode were commissioned as late as the 1540s and ran concurrently with early antique works for two or three decades. The Gothic or, as it was termed in French and Dutch, modern, was largely a field of nonmimetic, geometric composition, whereas the antique was rooted in imitation of the world and the human body as its measure. The two modes referred to divine authority in different ways, and these were immediately signaled by pointed arches and tracery as opposed to round arches and the established categories of columns.

A conspicuous ornamental detail could call attention to a particular area in a larger work or composition. Or it might be used to complicate a narrative. Ornamental objects—carved or depicted—might include inset vignettes that placed the overall narrative of a work on different levels. Ornament was one of the sites where artists could display their most liberal fantasy and imagination—their faculty of invention freed from the usual constraints dictated by the decorum of their nominal subjects. In this sense, it was the ideal aesthetic object, liberated from the restrictions of rational thought.Footnote 17 This is especially true of the grotesque in its various guises, a point of contact between different media. Artists of all media fashioned grotesques of such variety and distinctness that they might stand as a kind of secondary signature or badge of identity. Netherlandish sculptors, for instance, included idiosyncratic variants of the grotesque as an almost obligatory addendum on the tombs they carved (fig. 6).

Figure 6. Netherlandish sculptors. Grotesques on tombs: Cornelis Floris, tomb of Adolf von Schauenburg, ca. 1556, Cologne Cathedral; Anton van Seron, monument to Moritz of Saxony, ca. 1559–63, Freiberg Cathedral; anonymous Netherlandish sculptor (Philipp Brandin?), tomb of Ernst the Confessor, 1576, Celle Stadtkirche. Author's photos.

Ornament might be further understood as a system by which elements of different classes of visual information—iconic, narrative, symbolic—are integrated. Ornament stands apart from each of these separate indexes. This is very much the view of the philosopher Niklas Luhmann, who maintains that it provides the infrastructure for works of art. “Ornament,” he asserts, “holds the artwork together, precisely because it does not partake in its figurative division.” It offers, according to Luhmann, an “infrastructure,” an organizational metasystem that operates outside the representative dimension.Footnote 18 But by the middle of the sixteenth century, ornament had become its own subject. Printmakers such as Lucas van Leyden (ca. 1494–1533), Cornelis Floris, Vredeman de Vries, and Cornelis Bos (1508–55) dedicated a part of their oeuvre to ornamental patterns, and certain artists specialized in the practice. The Antwerp print publisher Hieronymus Cock (1518–70) issued multiple series of ornamental designs to meet market demand.Footnote 19 Ornament could pose as the essential supplement—a pivotal addition to its carrier.

By the mid-sixteenth century, the notion of embellishment, familiar from Latin and vernacular literary treatises, gave rise to a tension between the object and its addition. In addressing this dynamic, several art historians have recently relied on Jacques Derrida's critique of Immanuel Kant's (1722–1804) discussion of ornament and the frame.Footnote 20 Yet this reading, which continues to inflect studies of Renaissance ornament, is dependent on a relatively modern understanding of the work of art, on its presumed aesthetic autonomy, and is of questionable relevance to earlier periods.

ORNAMENT AND THE VERNACULAR-CLASSICIZING DIVIDE

One of the more notable structuring theories of sixteenth-century Netherlandish art is the idea of a programmatic divide between pan-European painters like Frans Floris and localizing artists like Pieter Bruegel, who, in the prescient words of Mark Meadow, “rejected the model of classicizing, Italianate art to valorize instead a peculiarly Northern, descriptive style.”Footnote 21 This binary model has since been usefully critiqued, most notably in the recent publications by Joost Keizer and Todd Richardson, and by Bart Ramakers. These two anthologies, in particular, have provided a chance to reevaluate the ideas of classicism and the vernacular—expressions that are still invoked to articulate the wide range of artistic idioms in the mid-sixteenth century.Footnote 22

Both terms—classicism and the vernacular—are now generally understood as problematic. Most authors reject the notion of an unbridgeable gap between local and foreign, concluding that most Netherlandish painting demonstrates a complex synthesis of different traditions. Equally contentious is the word classicism, which has been fruitfully examined in collections edited by Rudolf Bockholdt and David Freedberg.Footnote 23 While acknowledging an abiding European admiration for the forms of Greco-Roman antiquity, Henri Zerner has argued that classicism is essentially a mode of authority and can apply to a number of formal strategies imbued with authority in a given culture.Footnote 24 Writers have stressed the inevitably utopian nature of the classical and called attention to the cryptotheological basis of its authority—that the term arose in Germany during the second half of the eighteenth century in a university setting sharply influenced by developments in Protestant theology.Footnote 25 It is perhaps understandable, therefore, that the classical is seen as transcending time—always valid and always present.

Ornament is key to this discussion. Whereas most considerations of the perceived divide between vernacular and classicizing art focus almost exclusively on painting,Footnote 26 studies of ornament embrace varied media. After all, Frans Floris's brothers were Cornelis Floris, Antwerp's most prominent sculptor, and Jacob Floris, a prolific designer of ornamental prints. Frans and Cornelis collaborated on at least one project, and they both journeyed to Rome, where they drew copies of ancient monuments and inscribed their names in the Domus Aurea (Nero's Golden House, ca. 64 CE) with its celebrated grotesques.Footnote 27 Although Coecke van Aelst's publications are usually relegated to the domain of architectural history,Footnote 28 this segregation of media is very much a modern phenomenon. Coecke van Aelst was himself trained as a painter and closely integrated his designs for many arts. Typically, he dedicated his books not only to architects but also to painters, sculptors, and lay lovers of beauty.Footnote 29 Over the last several decades, Theodoor Herman Lunsingh Scheurleer, Keith Moxey, and Meadow have shown how Aertsen and Beuckelaer appropriated Coecke van Aelst's architectural designs for their paintings of religious and secular market scenes.Footnote 30 And Pieter Bruegel's more pan-European contemporaries, such as Frans Floris, Willem Key (ca. 1515–68), and Jan Massys (1509–75), were careful to place formidable ancient artifacts in their pictures: fountains, statues, sarcophagi, or Roman buildings shown complete or as ruined fragments. In Frans Floris's early painting of the Judgment of Paris (ca. 1550, Gemäldegalerie, Kassel), the artist situates an ancient sculpture of a reclining river god above a fountain, decorated with mythological reliefs. In his Adoration of the Shepherds (1568, Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp), the reverence of the Christ Child takes place against the ruins of what appears to be an ancient Roman market. Michael Coxcie (1499–1592), the grand figure painter and Habsburg court artist, often set his figures within spaces rigorously structured by ancient architecture. This occurs in his groundbreaking altarpiece of 1540 for Antwerp Cathedral (currently held at Kremsmünster, Benediktinerstift), as well as in his late Circumcision (Mechelen, St. Rombouts Cathedral) of 1589, which displays a particularly inventive and idiosyncratic approach to capitals, vaulting, and the simulated colored marble of the columns.Footnote 31

Significantly, ornament was a central concern in one of the key texts adduced in art historical discussions of the vernacular: Lucas d'Heere's invective of 1565 against a “certain painter” (“quidam schilder”) who has slandered his master, Frans Floris. Both Freedberg and Meadow have cited this poem as evidence of an artistic community divided between adherents of a foreign classical ideal and local conventions.Footnote 32 Significantly, d'Heere casts the putative attack on Floris and his defense in terms of ornament:

Ornament refers to the dress or embellishment of both Floris's rich pictures and the kermis dolls of the quidam schilder. Although d'Heere uses the transitive verb vercieren (to ornament or adorn), the substantive forms (cieraet, cierage, and vercieringhen) were also common and constituted ornament as an object. The word and its synonyms had been applied to the arts before the sixteenth century, but chiefly as metaphor. The use of ornament as a technical artistic or architectural term in the Low Countries, however, seems to date only from the introduction of the antique mode. Before this time, roughly 1530, contracts and other texts almost always refer to decorative elements by their particular names—pinnacles, tracery, candelabra, etc.; there does not seem to have been a collective term for Gothic ornament, which is, itself, highly significant.Footnote 35

As Giancarlo Fiorenza has pointed out, the terms ornamented, becomingly, and richly (verciert, becamelic, rijcke) were critical terms that d'Heere drew from the theory and practice of contemporary French poets. D'Heere, like his friend Jan Van der Noot (1539–95), was attentive to the poetry of the Pléiade, especially to that of Pierre de Ronsard (1524–85), whose mythological themes often parallel those of the Antwerp painter Frans Floris and his contemporaries in their foregrounding of ornament. Ronsard frequently described objects with narrative motifs—nested stories that would then be allegorically situated in terms of the entire poem. Textiles, musical instruments, armor, and jewelry might all find their place in his verse. Neptune's cloak in “Le Ravissement de Cephale” and Leda's basket in “La Defloration de Lede” both contain vignettes of gods and their actions. In Ronsard's “La Lyre,” the poet describes an instrument inlaid with Apollo dining at the feast of the gods, a scene remarkably comparable with the setting of several of Frans Floris's paintings. Terence Cave has described this “mythological style” as “ornamental.”Footnote 36 As Fiorenza analyzes it, it is a celebration of poetic creation and artistic production.Footnote 37

The use of ornament to provide narrative insets—to order complex layers of the story—frequently occurs in Netherlandish art. In his Adoration of the Magi in Naples, Joos van Cleve has King Melchior present a gold vessel bearing a relief of the judgment of Solomon (fig. 5).Footnote 38 The Old Testament theme bears a typological relation to the main action, but it also established a hierarchy of stories to be interpolated by the viewer, who must decipher the nested narrative design on the vessel and then relate it to the overarching theme of the picture. A different use of ornament and a closer pictorial counterpart to the poetry of the Pléiade is perhaps Frans Floris's Venus in the Forge of Vulcan (ca. 1560) (figs. 7–8).Footnote 39 Here the painter depicts the goddess of love in her husband's atelier. The subject is an opportunity for Floris to display his ability at rendering the female and male nude; Venus's pale skin contrasts markedly with the tanned bodies of Vulcan and his assistants. But the painting is also an occasion for Floris to demonstrate his skills as an armorer, rivaling the artistry of Vulcan himself. The ruby-red shield with the head of Medusa at the lower right, the elaborate wheel next to it, and the ornate silver helmet grasped by Venus at the far left are as magnificent as any armor or artillery owned by Charles V (1500–58). Indeed, the artifacts represented in the painting resemble items that the famous Filippo (1510–79) and Francesco Negroli (ca. 1522–1600) had fashioned for the emperor.Footnote 40 No finer arms did Vulcan craft for Aeneas.

Figure 7. Frans Floris. Venus in the Forge of Vulcan, ca. 1560. Berlin, Gemäldegalerie. Author's photo.

Figure 8. Frans Floris. Venus in the Forge of Vulcan, ca. 1560, detail. Berlin, Gemäldegalerie. Author's photo.

ORNAMENT AND ELEMENT

Ornament was often received in terms of discrete motifs or individual elements. Pieter Bruegel, for instance, was attentive to classicizing ornamental design, though he signaled this appreciation through components detached from larger objects. In paintings such as The Battle between Carnival and Lent (1559), for instance, he was equally attuned to specifically indigenous design. The church at the right of this painting demonstrates the painter's attention to the older Brabantine Gothic, though this architectural manner is primarily indicated by the geometrical tracery in the rose window and the minimal buttressing of the building. These elements of the Gothic have come to signal an entire local mode and, with it, a traditional way of life.

Bruegel's friend, the cartographer and cosmographer Abraham Ortelius, was likewise attracted to the latest ornamental genres and motifs. He used inventive patterns as cartouches in both his famous atlas, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theater of the world, 1570), and in his personal album amicorum, which he circulated to friends for the purpose of adding inscriptions within these frames.Footnote 41 For both projects, Ortelius commissioned the painter, theorist, and ornamentalist Vredeman de Vries to supply the artful strapwork cartouches.Footnote 42 And when another of Bruegel's friends, the painter Maerten de Vos, painted a family portrait from this social circle, he set the dedicatory inscription within a similar ornamental frame (1577) (fig. 9).Footnote 43 In these cases, the frame bestows dignity and authority. De Vos, in fact, ennobled his painting with various types of ornament. Antonio Anselmo, Joanna Hooftman, and their children are conspicuously costumed with considerable attention paid to imitating the different textiles and their embroidery; the painting of the lace collars is itself a virtuoso performance. But de Vos has also included less customary elements, such as the vase of flowers on the table behind the figures. Such still lifes were only beginning to be appreciated as independent artworks; during the second half of the sixteenth century they had become cherished details in portraits and religious scenes. The vase takes its place among the other objects on the table: an inkwell with two quills, a letter, a flower, and a pair of gloves. Above this ensemble the painter adds the ornate strapwork cartouche with its curling and hard-edged protrusions. It is an original contribution to a genre practiced by so many Netherlandish artists of the time. De Vos's ornament renders the portrait an artful, creative product, a prestigious artifact commanding attention, rather than a simple visual document of an Antwerp family.

Figure 9. Maerten de Vos. Portrait of Antonio Anselmo, Joanna Hooftman, and Their Children, 1577. Brussels, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts. Author's photo.

The strapwork cartouche was employed at the highest levels of society. It is one of the few elements that distinguish the archaicizing tomb of Charles the Bold (tomb, 1558–63) (fig. 10) from that of Mary of Burgundy (tomb, 1488–1501), which rests beside it in the choir of the Church of Our Lady in Bruges. The loss of the physical body of Charles the Bold had always been a sore spot to the Habsburgs. The Duchy of Lorraine had been more than happy to entomb Charles at Nancy, where he had famously fallen in battle. After several unsuccessful attempts to repatriate the corpse, Charles V was finally able to reclaim the body of his Burgundian predecessor and lay it alongside that of Charles's grandmother. Because Mary of Burgundy married Maximilian I of Habsburg (1459–1519), this juxtaposition of sepulchers in Bruges was an important sign of dynastic continuity and legitimation of Habsburg rule of the Low Countries.

Figure 10. Jacques Jonghelinck et al. Tomb of Charles the Bold, 1558–63, detail. Bruges, Notre Dame. Author's photo.

The tomb was designed and executed principally by Jacques Jonghelinck (1530–1606), the brother of Bruegel's dedicated patron, Nicolaes (1517–70). Although Cornelis Floris was asked to critique the plan, Jonghelinck intentionally rejected current models of funerary monuments, instead replicating many features of the older tomb of Mary of Burgundy. This was essentially a tomb chest with a recumbent brass effigy atop a substantial black marble base. Jonghelinck's greatest departure from Mary's sepulcher is the east end of the chest, which details Charles the Bold's achievements. The Gothic angels have been modernized and now look a bit like nymphs in paintings by Frans Floris or Jan Massys. But the most significant addition is the thoroughly up-to-date strapwork compartment that holds the text. By 1558 this ornamental frame was deemed necessary to bestow the requisite gravitas on the inscription.

The art of Hans Vredeman de Vries relates to that of Bruegel in unexpected ways. In addition to his work as a designer of ornament, Vredeman de Vries specialized in perspectivally constructed pictures of imaginary and heavily decorated architecture. Karel van Mander (1548–1606) reports that Bruegel augmented one of Vredeman de Vries's architectural fantasies with figures of two peasants in amorous embrace.Footnote 44 Although this work has not survived, Pieter Bruegel's design for Spring (1565) is indeed extant in both the original drawing and the subsequent print, which was engraved by Pieter van der Heyden (1530–72) and published by Hieronymus Cock. In the foreground, an aristocratic woman and her foppish daughter direct an obsequious peasant, who tends to a garden that is meticulously set out in discrete fields. Its careful composition looks forward to the landscaped terraces in Vredeman de Vries's book of garden design, the Hortorum Viridariorvmque Elegantes et Multiplices Formae (Elegant and complex images of gardens and parks) of 1583, which arranges garden patterns according to classical ornament—the species of columns.Footnote 45

Vredeman de Vries and his contemporaries tended to use architecture and ornament interchangeably. How are the two distinct? Architecture is usually conceived as a set of built edifices. Yet it may be better to think of architecture—particularly antique architecture—as an idea, manifested in a variety of texts and visual media. This is very much the case for France in the early sixteenth century, as Tara Bissett has shown, and it applies to the Low Countries as well.Footnote 46 Indeed, some of the most sophisticated antique designs occur in the paintings by Bernard van Orley (1487–1541) and the prints published by Hieronymus Cock. There were actually very few inhabitable buildings in the antique manner in the Low Countries until the late sixteenth century. And the antique elements that were constructed were often parts added to earlier Gothic or nondescript structures: portals, gables, or works of so-called microarchitecture, such as tombs, altarpieces, pulpits, choir stalls, and sacrament houses (towering receptacles holding the consecrated Host). These works can be seen as assemblages of decorative elements recombined to form the ornamental object.Footnote 47

Antique architecture was, in fact, often consumed in fragments. The sophisticated connoisseur Philip of Burgundy (1464–1524), patron of Jan Gossart, understood the legacy of Rome in much this way. As his court historian Gerard Geldenhouwer (1482–1542) reported, “When the conversation turned to architecture, [Philip] … spoke so precisely about pedestals, columns, architraves, cornices and other such things that one would think he had quoted from Vitruvius.”Footnote 48 This understanding of architecture as a series of parts also characterizes one of the bestsellers of the time, the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (The strife of love in a dream), published in Venice, in 1499, but translated into French and issued three times in the mid-sixteenth century.Footnote 49 This beautifully illustrated book tells of Poliphilo's search for his beloved Polia, all of which is recounted from a dream. The nostalgic allegory includes prolific descriptions of ancient architecture—of temples but also of tombs, fountains, and the like—much of it in ruins. There is considerable talk of bucrania (ox skulls), of pedestals with ram's heads, and other such fragmentary appointments, most of which are illustrated in the artful woodcuts.Footnote 50

One finds this appreciation of the architectural fragment in the writings of Pieter Coecke van Aelst, one of the most consequential designers and theorists of ornament in the Netherlands.Footnote 51 His books Die inventie der colommen (The design of columns, 1539) and his Generale reglen der architecturen (General rules of architecture, 1539), adapted from Sebastiano Serlio, present the art of building as a series of ornamental modes fashioned according to the different orders, which were only then becoming conventional. Although these volumes describe and illustrate monumental features such as facades, they frequently break architecture down into ornamental elements, all given names and appropriate proportions. Capitals, pedestals, mantelpieces, masonry details, and other such motifs are all addressed singly in text and image. The title page of Coecke van Aelst's Generale reglen der architecturen is emblematic. The words are set within a classical portal with male and female herms supporting a unique pediment. This pediment does not enclose an inscription or a figural relief. Rather, it frames a rectangular cavity filled with a chaotic assembly of architectural fragments. This jumbled antique bric-a-brac is made to stand for architecture itself (fig. 11).

Figure 11. Pieter Coecke van Aelst. Generale Reglen der Architecturen, title page. Antwerp: Pieter Coecke van Aelst, 1539. Author's photo.

Ornamental genres could easily supplant one another. The title page to Coecke van Aelst's French edition of the Generale reglen, from 1542, dispenses with the simulated portal and substitutes an elaborate grotesque surround, one without clear spatial properties (fig. 12). By the time that Coecke van Aelst's Den eersten boeck van Architecturen (First book of architecture) was published in 1553, a strapwork cartouche had taken the place of the grotesque surround (fig. 13). It is in this context of proliferating ornamental systems that new words appear. In fact, the word ornament seems to occur first in a Dutch text in Coecke van Aelst's Generale reglen of 1539.Footnote 52 One of Coecke van Aelst's most enlightening comments on the subject, however, is the definition he offers for décor in Die inventie der colommen, issued the same year: “Decoration [Décor]: that is ornament [ciraet] or curiosity [curieusheit], which is made complete through its status, usage, and nature.”Footnote 53

Figure 12. Pieter Coecke van Aelst. Regles generales d'architecture, title page. Antwerp: Pieter Coecke van Aelst, 1542. Author's photo.

Figure 13. Pieter Coecke van Aelst. Den eersten boeck van Architecturen, title page. Antwerp: Pieter Coecke van Aelst, 1553. Author's photo.

The coupling of “curiosity” with ornament is telling. The word curiosity cuts across different fields of meaning and had quite varied applications by the mid-sixteenth century.Footnote 54 Closest to its Latin root, cura, was the intimation of diligence and care, often excessive, in crafting highly decorated objects or architectural elements.Footnote 55 But the term conveyed more than this notion of elaborate fashioning. It could bear with it the idea of a nearly obsessive inquisitiveness that might attach itself to objects or human actions—in other words, an intense desire for knowledge of the material or human world. Curiositas or curieusheit had not entirely escaped the opprobrium of medieval writers, who viewed it as a dangerous distraction from serious matters, a beguiling seduction of the intellect that led it on a chaotic course unfettered by discipline or purpose. Hendrik Herp's Spieghel der volcomenheit (Mirror of perfection), published frequently in the early years of the sixteenth century, still uses the word in this sense.Footnote 56 But other writers began to endow the term with a more neutral valence, especially in secular discussions. This was particularly true of French usage.Footnote 57 Coecke van Aelst's spelling indicates that he adapted the term from the French rather than Latin, with its stronger patristic overtones. Of equal importance, the term might be transferred from the subject (one who experiences curiosity) to the object, which induces an attitude of curiosity in the beholder.Footnote 58 The curious object was something that drew the eye and the mind to it, stimulating reflection. It is this aspect of curiosity that prefigures the modern aesthetic regard.Footnote 59

ORNAMENT AND MODE

The introduction of the concept of ornament had much to do with the sudden juxtaposition of a thriving Gothic tradition with a new antique vocabulary of forms. Artistic mode was no longer a matter of recourse but rather a conscious choice, one that induced deliberation on the nature and value of ornamental systems. Prominent works in the Gothic mode, indeed, continued into the 1540s.Footnote 60 In 1536, for example, a sacrament house was commissioned for the St. Gommaruskerk, in Lier, near Antwerp. The contract for this work is especially interesting because it emphasizes the type of ornament to be employed. The work was to imitate a famous prototype in Leuven's Pieterskerk, from 1450—as far as the ground plan was concerned. But the tracery forms were to be in the latest flamboyant fashion: “in the new manner, that is to say, of masonry, as it is practiced these days.”Footnote 61 This was not the antique or Italianate fashion but rather a more current and elaborate version of Gothic forms. And the next year another flamboyant sacrament house was commissioned for Leuven's Jacobskerk, also following the revered older model and once again with more up-to-date ornamental figures.Footnote 62 Leading Netherlandish painters, such as Jan de Beer (1475–1527/28), Gerard David (1460–1523), Quentin Massys (1466–1530), Bernard van Orley, and Jan Gossart, exploited this latest Gothic for its rich associations.Footnote 63 But since the second decade of the sixteenth century, an alternative antique mode was also practiced.Footnote 64 And the coexistence of two different systems compromised them both. It prevented either from pretending to universal authority.

Gothic design was based on geometry; its elements were constructed with a compass and straightedge and bore little relation to objects in the world. In fact, the mathematical nature of Gothic forms could signify their celestial origin. God might conceive of all objects and creatures in mathematical terms, yet these inevitably became corrupted through their materialization in the world. The Gothic church and its furnishings could represent a prior state of creation—closest to the divine idea. This was especially true of Gothic drawing, which depended on different geometric operations, even if mimetic elements were included in actual buildings. And it was true of ostentatiously ornamental details of Gothic buildings—traceried windows, figured vaults, openwork balustrades—which presented as “pictures of geometry” and as a synecdoche for the Gothic itself.Footnote 65

Antique design communicated different concepts. Architectural members represented real-world objects, if at some remove. Columns modeled their proportions after various gendered bodies. And the triglyph, for instance, was thought to derive from the end of a supportive ceiling beam. To the degree that the Gothic was metaphysical, the antique was dramatically physical. Furthermore, the antique was associated with political power and military triumph in its earliest articulations in Northern Europe. With the French invasion of Northern Italy in 1494, and the subsequent battles over Lombardy by French and Habsburg forces, the antique or Italianate manner was appropriated as a kind of cultural spolia by Northern rulers. The antique mode was chosen for the tombs of the French kings Louis XII (1462–1515) and Francis I (1494–1547), whose Italian campaigns are indexed in the battle reliefs around the bases of these monuments. In 1526, Charles V began his palace in Grenada in a severe antique style, which was also appointed with battle reliefs.Footnote 66 Concurrently, he wore his beard in the fashion of ancient Roman portrait busts and insisted on being addressed as Caesar.Footnote 67 Accordingly, Charles was greeted by antique arches in his state entries into Bruges, in 1515, and Antwerp, in 1549. The leading Netherlandish nobles followed suit. The antique mode in which the tombs of the families Nassau, de Croÿ, and Lalaing were cast signaled political currency and propinquity to the emperor.Footnote 68

For several decades, however, both the Gothic and the antique were available to discerning patrons. A contract from 1530 for a sacrament house and a choir screen for the Abbey of Tongerlo suggests just how open was the choice of mode. The wording makes it clear that Gothic and antique were equally acceptable. The sculptor Philip Lammekens of Antwerp was instructed that the ornamental mode of the works was to be left up to him and the abbot: “be it of the antique or Gothic [manner] as my Lord the Abbot and Master Philip shall determine.”Footnote 69 The mode of execution was no longer fixed by the class of monument or its site. Despite being assisted by avowedly antique sculptors like Claudius Floris, the uncle of Frans and Cornelis, Lammekens was allowed to choose the mode himself—Gothic or antique—albeit with the advice of the abbot. Neither mode was to be preferred on account of its political or religious connotations.

THE GROTESQUE

The most popular species of antique ornament was the grotesque.Footnote 70 As an unmistakable reference to Roman antiquity, it became an obligatory addendum, a sign of validity on the sculpture of Cornelis Floris and his followers. Many of the same areas and fields that once contained Gothic ornamental patterns were soon occupied by grotesque equivalents; thus, an aspect of the modal change was a substitution of a particular element in one system with its counterpart in the other system. This, by the way, is very much how the Renaissance grotesque was supposed to be assembled, if it was to be tolerated at all. Hybrid creatures were to be fabricated by substituting one animal part for the corresponding part in another animal: a lion's head for a horse's head, and so on.Footnote 71 A comparison between two carved altarpieces from Antwerp, executed some thirty-five years apart, reveals both the change in mode and continuity in the logic of design (fig. 14). The Passion altarpiece from ca. 1525, in Bielefeld, shelters each compartment with an intricate Gothic baldachin composed of pointed arches, struts, and buttresses—all hanging in open air. Much has changed in the Passion altarpiece from around 1560, now in Roskilde. The baldachins hanging above the narrative scenes have now become compositions of grotesque motifs: hybrid sirens, masks, flowers, and tendrils in place of the usual patterns of Gothic tracery. Yet they occupy the same place in the overall design as the Gothic baldachin in the earlier work. One suspended decorative feature has replaced another, preserving the order of the system.

Figure 14. Antwerp artists. Passion altarpiece, ca. 1525, detail of baldachin, Bielefeld, Nicolaikirche; Antwerp artists. Passion altarpiece, ca. 1560, detail of baldachin, Roskilde Cathedral. Author's photos.

Even when serving as a marker of antiquity, the grotesque might convey the notion of prodigious artistic imagination. This is profoundly the case with the Tomb of Engelbrecht II of Nassau (1531–34) (figs. 15–16), the probable first owner of Hieronymus Bosch's Garden of Earthly Delights (ca. 1490).Footnote 72 Engelbrecht and Cimburga of Baden lie together at the bottom. The remarkable conceit of the monument has four warriors of antiquity kneeling to support a plinth, which holds Engelbrecht's knightly armor.Footnote 73 These dignitaries paying homage to Engelbrecht have been identified as Julius Caesar, Hannibal, Philip of Macedonia, and Atilius Regulus. As notable as their ancient pedigree, however, is their armor: they are covered from head to foot in original and differing configurations of grotesque ornament. This carving offers an appealingly tactile interface between the tomb and the beholder; it makes literal the notion of ornament as dress, the tangible and sensory face of the work.

Figure 15. Netherlandish artists. Tomb of Engelbrecht II of Nassau and Cimburga of Baden, 1531–34. Breda, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk. Author's photo.

Figure 16. Netherlandish artists. Tomb of Engelbrecht II of Nassau and Cimburga of Baden, 1531–34, detail: Philip of Macedonia [?]. Breda, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk. Author's photo.

This notion of ornament as dress was not uncommon. The Nuremberger Hans Sachs (1494–1576) described antique ornament in this way in his account of Peter Flötner's Triumphal Arch for the entry of Emperor Charles V into the city, in 1541.Footnote 74

The concept of ornament as dress, in fact, had long been known from treatises on rhetoric. The fifteenth-century architect Leon Battista Alberti was likely drawing on such ideas when he considered ornament to be the external trappings of a building, its variegated surface that clothed its abstract ideal form. Alberti insisted that buildings were first to be constructed “naked” before they were decorated.Footnote 76 Ornament might thus be understood as its sensory presentation, the building as phenomenon. At Breda the four bearers are literally clothed in ornament—in grotesques that seem alive, pulsating with the willful force of the fantastical creatures and flora that cover the harnesses, helmets, and leggings.

In the Netherlands, the grotesque was an ever-expanding genre; it mingled easily with the drolleries of medieval manuscripts and the elaborate scrollwork of printmakers. The grotesque exhibited the deformed and impure body: the monster, existing in a cognitive netherworld between recognized categories. Mikhail Bakhtin has emphasized the liberating and constructive (or reconstructive) aspect of the grotesque, a state related to the Carnivalesque, with its social misalliances and hybrid concatenations.Footnote 77 But the grotesque was an unbounded figure in a more profound way, a hybrid assemblage of animal, vegetal, and mechanical parts and an emblem of ungoverned fertility and growth. It threatened chaos and was thus carefully contained, confined, and disciplined by the architectural framework that it inhabited. Many of the grotesque prints by Cornelis Floris and Cornelis Bos imprison their amalgamated and transgressive forms within bands of strapwork, as Henri Zerner and Rebecca Zorach have noted (fig. 17).Footnote 78

Figure 17. Cornelis Floris. Design for a grotesque, 1557. Etching and engraving. © Trustees of the British Museum.

A different configuration of the grotesque appears on the magnificent mantelpiece dedicated to Charles V, in the Bruges Vrije, the administrative building of the lands surrounding the city of Bruges (1528–31) (figs. 18–19).Footnote 79 Life-size statues of Charles and his four grandparents stand before the breast of this extensive work. Situated around them are numerous grotesque inventions: centaurs surrounding candelabra, bifurcated tritons, and crossbred chimera. On one level, the grotesque could communicate the threat of chaos, the potential invasion of the center by a monstrous periphery. This was a ground against which Charles V might establish his rule of order. But the grotesque could serve other functions as well. On another level, the strange creatures that abundantly adorn the spindly architectural contours offer an alternative structure, an abbreviated network in which the political effigies are situated. Netherlandish grotesques rarely comprise the continuous ornamental web that occur in the frescoed vaults of Italian chapels and palaces; in Bruges, the grotesque appears as a series of discrete features, separate inventions all expertly crafted. These details adumbrate a system that exists both around and apart from the statues and narrative reliefs. Such grotesques were frequently banned to the margins as in so many Netherlandish tapestries of the mid-sixteenth century. Editions of Coecke van Aelst's series of the Seven Deadly Sins, for instance, are bordered with bizarre and whimsical vehicles, resembling ships and wagons that both carry and confine their human cargo.Footnote 80 Were these grotesque images merely empty conventions, assigned without much thought by the weaver, or could they be read in concert with the central scene—perhaps in opposition, as a form of slightly ominous nonsense that only heightened the contrasting seriousness of the central subject?

Figure 18. Lanceloot Blondeel (designer). Mantelpiece to Charles V, 1528–31. Bruges, Vrije. Author's photo. © Musea Brugge.

Figure 19. Lanceloot Blondeel (designer). Mantelpiece to Charles V, 1528–31, detail of grotesques. Bruges, Vrije. Author's photo. © Trustees of the British Museum.

The notion of the grotesque as a marginal invention was not limited to the visual arts. In his essay “On Friendship,” Michel de Montaigne (1533–92) speaks of his own words as akin to grotesques with which painters frame their principal subjects and which delight solely due to their “variety and strangeness.” Montaigne presents his text both as a hybrid concatenation of random thoughts and as an ornament of a separate, central idea:

As I was observing the way in which a painter in my employment goes about his work, I felt tempted to imitate him. He chooses the best spot, in the middle of each wall, as the place for a picture, which he elaborates with all his skill; and the empty space all round he fills with grotesques; which are fantastic paintings with no other charm than their variety and strangeness. And what are these things of mine, indeed, but grotesques and monstrous bodies [crotesques et corps monstrueux], pieced together from sundry limbs, with no definite shape, and with no order, sequence, or proportion except by chance?

Desinit in piscem mulier Formosa superne.

I am at one with my painter in this second point, but I fall short of him in the other and better part. For my skill is not such that I dare undertake a fine, finished picture that follows the rules of art.Footnote 81

Montaigne had intended his lines to adorn a political treatise by his friend Etienne de La Boétie (1530–63), which was originally to be included in the center of book 1 of the Essays. The treatise was published elsewhere, however, and Montaigne's words eventually stood alone as an ornament without its supposed subject.

Indeed, on occasions the grotesque might seem to overrun whole objects; the oak choir screen in the Dutch town of Enkhuizen, from 1542, has its entire base, piers, and entablature covered with elaborate grotesques that change their design in every bay, revealing an encyclopedic range of hybrid creatures—from the detached heads of frightened horses, to forbidding sirens, to frog-footed boys (fig. 20).Footnote 82 Lunettes with sculptures of Christ and the Evangelists top the screen, but the remainder of the surface is given to a wealth of grotesque invention.

Figure 20. Netherlandish sculptors. Choir screen, 1542, detail. Enkhuizen, Grote Kerk. Author's photo.

The grotesque was above all a field for play, for radical artistic invention of the most dreamlike kind. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), in fact, referred to grotesque designs as Traumwerk (dreamwork).Footnote 83 In this sense, it enjoyed a kinship, especially in the north, with the chimera of manuscript marginalia and, ultimately, with the misbegotten creatures of Hieronymus Bosch (1450–1516) and Pieter Bruegel.Footnote 84 It is in this context that Jeronimus Scholiers, who in 1576 was living in Madrid, made a rather surprising statement to his friend Ortelius: “I have often thought of you because everywhere we see more ingenious headdresses than I think Frans Floris or Hieronymus Bosch could ever have ornamented; if they have never been here, they must at least have dreamt of these fashions.”Footnote 85 The association with Hieronymus Bosch and Frans Floris is unexpected. It is easy to link this statement to the well-worn issue of naturalism that Ortelius raised in his Latin tribute to Bruegel, and its supposed opposition to Floris's manner. But it is perhaps more useful to connect it with the hyperinventive dream world of grotesque ornament. Of course, Bruegel famously emulated Bosch's strange hybrid organisms in the early years of his career, an artistic turn that drew considerable international notice.Footnote 86

One of the more interesting manifestations of this celebrity was the series of woodcuts published by Richard Breton in Paris, in 1565, under the title of Les Songes drolatiques de Pantagruel (The comic dreams of Pantagruel).Footnote 87 Several of the images were closely adapted from details in Bruegel's Boschian engravings of the Seven Deadly Sins (1558) (fig. 21).Footnote 88 Breton's short introduction explicitly relates his designs to the realm of ornament by stating that his inventions are of use in devising “crotestes” (“grotesques”).Footnote 89 His title explicitly frames these creations as dream fantasies. The adjective drolatique, its first appearance in French, derives from the Dutch root drol or drolle—troll or goblin, the deformed mythic dwarf—which lends a malevolent overtone to its comic import.Footnote 90 When Christophe Plantin (1520–89) sent Bruegel's engravings of the Seven Deadly Sins to a Parisian print dealer, in 1561, he referred to the works as “7 pechez drolleries,”Footnote 91 the traditional term for Northern European monstrous forms.Footnote 92

Figure 21. Pieter Bruegel. Avarice, 1558, detail. Engraving. Antwerp: Hieronymus Cock (left); Les Songes drolatique de Pantagruel. Paris: Richard Breton, 1565, page 110 (right). Author's photos.

Several of Breton's plates were culled from the margins of Jean de Tournes's vernacular paraphrases of Ovid, published in Lyon, from 1557 to 1559,Footnote 93 which had more loosely adapted earlier genre prints for its ornamental surrounds. How natural that these grotesque changelings provided the margins for Ovid's Metamorphoses. And how fitting that these Northern Carnivalesque translations of the antique grotesque—these drolleries—accompanied de Tournes's vernacular paraphrases of Ovid, issued in Dutch, French, and Italian editions.

Among the most influential ornamental creations in the Netherlands were the scrollwork inventions of Cornelis Floris and Cornelis Bos, published by Hieronymus Cock, from 1544 to 1556.Footnote 94 Here, ornament, and specifically local ornament, is the ostensible subject: strapwork, that distinctive Northern creation without antique precedent.Footnote 95 Deriving to a considerable extent from Rosso's stucco frames at Fontainebleau (1535–37), strapwork was developed in imaginative new directions by Netherlandish artists in all media. Less suggestive of the curling edges of leather ribbons, leaves, or manuscript pages that mark French production (Rollwerk), the Low Countries variants exploit references to cut metal shapes of the goldsmith (Beschlagwerk). In one of his series, Bos's hard-edged designs served as cartouches for proverbs in French as well as Latin—the printed strapwork, a vernacular form of classical or elite decoration, joined with vernacular language. But here too the grotesque rears its head, and not only in the shifting and unstable categories of ornament. One of Bos's surrounds frames the French saying: “He who praises himself crowns himself with shit.”Footnote 96 Even in this privileged setting, the body evacuates itself, transgresses its porous boundaries, and links with the Carnivalesque forms of Rabelais and Les Songes drolatiques.

The greatest showcase for Netherlandish strapwork was the series of arches designed by Coecke van Aelst and other Antwerp artists for the entry of Charles V and the future Philip II into the city in 1549.Footnote 97 A printed record of the event was published the following year, with extensive woodcuts, giving these works a permanent presence (fig. 22).Footnote 98 Although the bodies of the arches seem massive and stable, several are crowned by expansive strapwork crests that have little if any framing function, and measure one-third of the total height. These exuberant culminations, skeletal with vegetal sprigs, recall garden trellises, bands of metalwork, and transformed Gothic tracery. Whether or not these inventions actually capped the constructed arches in their full glory is uncertain, though even as paper monuments they exerted considerable influence on tomb sculpture and other public structures.Footnote 99

Figure 22. Pieter Coecke van Aelst (designer). The Triumphal Entry of Prince Philip of Spain into Antwerp, 1549. Antwerp: Cornelis Grapheus, 1550. Author's photo.

KANT AND THE PARERGON

Notions of excess and superabundance have guided discussion of mid-sixteenth-century ornament, especially that of Fontainebleau and Antwerp. Yet what may seem excessive to present-day critics was not necessarily extreme or unwarranted to early modern viewers. Nor was ornament exclusively an accessory or addendum to some principal artistic subject, as has been assumed in post-Kantian discussions. Ornament was treated in diverse ways. Although Alberti considered it a “complement to beauty,” it is not entirely clear what he meant by this pronouncement and he was not consistent in his evaluation of the concept.Footnote 100

The popular sixteenth-century genre of ornamental prints conveys much about the status of ornament itself. Although the various engravings and etchings that featured ornamental elements were frequently intended for appropriation, for selective adaptation of their details transposed into new contexts, the prints acknowledged that ornament itself was recognized as a distinct subject. Particularly illuminating is the cycle of engravings designed by Jacob Floris, the younger brother of Frans and Cornelis Floris, which was published by Hieronymus Cock, in 1566.Footnote 101 In each print, a miniature narrative scene, mostly drawn from Ovid, is set within an expansive strapwork invention. A couple of sheets present two stories together: Apollo and Daphne and the Rape of Europa, for instance, each set within a distinct and elaborate frame (fig. 23). The complex and abundant strapwork and grotesque motifs all but overwhelm the figural scenes, as the title of the series, itself, acknowledges in Latin and Dutch: “A manifold kind of compartments/cartouches, as they call them, ornamented with the most elegant stories from history and the poets” (Latin);Footnote 102 “Very many variants of compartments/cartouches ornamented with little stories of mythology and other [themes] published by Hieronymus Cock—painter in the Four Winds” (Dutch).Footnote 103 What is usually thought of as ornament itself, the supplement or parergon, is here literally ornamented by the narrative. There seems to be a reversal of the natural relationship between a representation and its frame. The frame is now prime and must be complemented by its content.

Figure 23. Jacob Floris (designer). Zeer Vele Veranderingen Van Compertementen gheciert met Historikens van poesie en ander. Antwerp: Hieronymus Cock, 1566. © Trustees of the British Museum.

The understanding of content and frame is always mutually dependent. The putative subject is largely indeterminate, literally and figuratively unbounded without its frame. Ovid, yes. Apollo and Daphne, of course. An image of these characters, naturally, and not their real selves.Footnote 104 But to what end? What context? What application? Contained by their cartouches, the narratives are set as emblems of elite culture, themselves addenda to designs signaling fashion and authority. The frames, Netherlandish strapwork, signaled local authority, however, as opposed to the boundless authority of antiquity and its narrative subjects. This phenomenon was the culmination to the development that had begun at Fontainebleau.Footnote 105 Prints after the decoration of the galerie François Ier began to exalt the strapwork setting of the narrative scenes, leading to what Femke Speelberg has called the “emancipation of the ornamental frame.”Footnote 106

This was not only a discourse on paper. Strapwork and the grotesque assumed a newfound prominence and monumentality atop gables and funerary sculpture. This occurs, for instance, in the so-called Fürstenepitaph (princes’ epitaph) in the Cistercian church at Doberan, carved in 1583 by Netherlandish artists and attributed to the shop of Philipp Brandin (ca. 1535–94) (fig. 24).Footnote 107 The inscription on the expensive black marble panel records praise of the Mecklenburg rulers of the past: Henry the Lion-Hearted, Albrecht VII, Magnus III, and Duke Pribislav.

Figure 24. Netherlandish sculptor (workshop of Philipp Brandin?). Fürstenepitaph, ca. 1583. Doberan, Monastery Church. Author's photo.

The monument is crowned by undulating strapwork that supports two playful angels and an hourglass with a skull, all surrounding a small trio of coats of arms. These representational figures, however, are merely ornaments themselves to the entire elaborate alabaster cartouche. The frame contains no representation within, no effigy, no narrative relief of the resurrection or Last Judgment—only a text, a laudatory account of the rulers’ achievements. Ornament has invaded the center and again become the principal subject, the desired object, and the technology of glorification. The black marble was a privileged material and, no doubt, commanded attention. And, likewise, the inscription marked the status and imminent lineage of the rulers of Mecklenburg. But this text is more a presumed presence than a visible phenomenon, since it is only legible from a short distance. The sepulchral monument as marketable product and empowering form is its exalted frame. The Doberan epitaph is unusual, but it is not unique, and it hypostatizes tendencies in all arts. Might such a strapwork cartouche be called, somewhat paradoxically, a form of vernacular classicism? It lacked an ancient pedigree and presented as a local genre, to a degree, yet it conveyed the authority of the pan-European elite. And through its close relation to the grotesque, it became a venerated sign of artistic fantasy and ingenuity.

Several scholars have had recourse to Derrida's discussion of this problem in his reading of Kant's Critique of Judgment; indeed, this text underlies many recent considerations of ornament.Footnote 108 As Derrida memorably demonstrates, there can be no absolute demarcation between a subject and its frame, no pure cut.Footnote 109 The frame, the ornament, the parergon, supplies that which the nominal subject inevitably lacks, joining with it to form a conceptual whole. For Derrida, the parergon need not be only the physical borders that demarcate an image, but any ornament, any addition to the essential image that frames it. Derrida thus interrogates his predecessor: “And when Kant replies to our question, ‘What is a frame?’ by saying it's a parergon, a hybrid of outside and inside, but a hybrid which is not a mixture or a half-measure, an outside which is called to the inside of the inside in order to constitute it as an inside.”Footnote 110 Zorach roots much of her own discussion of ornament in the notion of the parergon that Derrida develops.Footnote 111

And yet this distinction between ornament and subject depends on the paradigm of aesthetic autonomy and the modern idea of the work of art, an idea that had only imperfectly formed by the mid-sixteenth century. Derrida's perspective is largely dependent on Enlightenment notions of subject and ornament. Clearly, chief among the contributors to this discourse was Kant, who was especially sensitive to the pleasures and dangers presented by the grotesque, which he specifically names in his Critique of Judgment. He praised its “freshness” of “unstudied and purposive play,” but he relegated it to the realm of the nonrepresentational, of the ornamental. Here, “regularity that betrays constraint is to be avoided as far as possible. Thus English taste in gardens, and baroque taste in furniture, push the freedom of imagination to the verge of what is grotesque [bis zur Annäherung zum Grotesken]—the idea being that in this divorce from all constraint of rules the precise instance is being afforded where taste can exhibit its perfection in projects of the imagination to the fullest extent.”Footnote 112 This free play of imagination was to be lauded, “subject, however, to the condition that there is to be nothing for understanding to take exception to.”Footnote 113 Indeed, Kant stresses that “the imagination in its freedom should be in accordance with the understanding's conformity to law. For lawless freedom of imagination, with its wealth, produces nothing but nonsense.”Footnote 114

As Winfried Menninghaus has shown, the 1790s, the decade when Kant published his Critique, saw the rise of an early Romantic “poetics of nonsense,” an apotheosis of imagination's free play, divorced from its function of constituting reality.Footnote 115 The nonrepresentational quality of this poetics allowed it to develop a series of alternative worlds that were nonetheless haunted by their oblique relationship to the real.Footnote 116 The cultural genres born of this movement were ornamental; the fairy tale, the arabesque literary narrative, and the visual arabesque, akin in certain respects to the grotesque. To the degree that Kant had visual examples in mind, he was responding partly to the license of rococo ornament, which, though on its way out, was continually revived in series of prints and interior decorations that gave it a ghostly presence into the nineteenth century.Footnote 117 Eighteenth-century critics had frequently decried the insolence of rococo ornament, its refusal to bow to the needs of its supposed bearer or content.Footnote 118 In one of his jibes at contemporary artistic practice for the Mercure de France (February 1755), Charles-Nicolas Cochin satirically praised the ornamentalist's vaunted independence: “But where our genius triumphs is in the frames of over-door paintings, for which we can claim we have provided an infinity of different designs. Painters hate us because they do not know how to arrange their compositions with the encroachment of our ornaments on their canvas; but too bad for them: such a great display of genius should stimulate their creativity; these are the kinds of bout-rimés that we give them to fill in.”Footnote 119

For eighteenth-century viewers, the rococo had violated the comfortable relation between frame and subject. In many interiors, the famous shell- and leafwork expanded radically from its status as container until it became, as Menninghaus observes, a substitute for the image itself.Footnote 120 At the Amalienburg, an eighteenth-century hunting lodge on the grounds of Nymphenburg Palace in Munich, branches, feathers, shells, nymphs, putti, ships, musical instruments, and trophies all emanate from the cornice and the frames of the mirrors, rendering ambiguous the structure of the interior and calling into question its subject (fig. 25).

Figure 25. François Cuvilliés, Johann Baptist Zimmermann, and Joachim Dietrich. Hall of Mirrors, 1734–39. Munich, Amalienburg. Author's photo.

Polemics against rococo ornament assailed its “semantic emptiness,” its lack of a reliable ground on which play and license might assume some meaning.Footnote 121 In this respect, the rococo bore some resemblance to the grotesque. Hermann Bauer, in fact, has identified the Renaissance grotesque as an important conceptual forerunner of rococo ornament. It is also closely related to the arabesque, the genre of meandering ornament that arose around 1800 on the heels of the rococo and came to signify a free, unattached beauty.Footnote 122 The essence of the grotesque, Bauer suggests, “is less the unreality of a combination theory of forms and motifs than the unreality of a combination theory of different spatial logics.”Footnote 123 It was the potential chaos of unstable spatial relations between ornament and image that posed the greatest threat. And it was just this type of insecure and volatile spatial construction that occurs in certain literary works of the time, like E. T. A. Hoffmann's Princess Brambilla: A Capriccio in the Style of Jacques Callot (1820), in which ornament figures so heavily and in which a relationship to the visual arts is explicit.Footnote 124 The structural discordance and impossibility of both the rococo and the Renaissance grotesque generated its own brands of unsettling nonsense.Footnote 125 This secondary order presented by hybrid, erotic, spatially indeterminate grotesques was always potentially subversive; Michel Foucault has interpreted sites of such apparent meaninglessness as “points of resistance” within established power networks.Footnote 126

As Niklaus Largier observes, Kant dealt with the threat of unconstrained imagination by relegating its products to a new aesthetic realm. These creations of fantasy became useful representations of sensations and emotions, however, only after they had been subjected to reason.Footnote 127 Kant seems to have developed this aesthetic domain partly from Martin Luther, who had established a separate sphere in which to regulate mystical and fantastical interpretations of the scriptures. In Luther's view, these intensely subjective readings proved dangerous. He depended on a “secular realm” (“welltliches Reich”) in which reason and convention would apply controls to these interpretations.Footnote 128 By the eighteenth century, the private sphere of mystical inspiration had itself been partially secularized into an aesthetic domain. Kant deplored the same intellectually lazy “enthusiasms” or “exaltations” in perceptions of the world that Luther had condemned in his critique of mystical biblical exegesis.Footnote 129 In fact, Kant's term, Schwärmerei, for these lax and passionate analyses was adopted from Luther's word, Schwärmer, used to characterize self-indulgent, mystical enthusiasts.Footnote 130 Kant was thus able to extract from the early modern theologian a foundation for his own defense against illogic and disorder. If Kant's concept of aesthetics drew from sixteenth-century culture, however, it departed from it significantly. Artworks from the earlier period were never entirely aesthetic objects in this sense, self-contained and subject to the disinterested regard of their viewers. And the notion of subject had yet to gain the stability it would acquire in the Enlightenment.

CONCLUSION

Ornament functioned as a variety of systems that managed different types of information placed in the visual field. It was relational, understood in the context of a given subject but not necessarily subservient to it. Ornament provided a variety of services to artists, patrons, poets, and intellectuals in sixteenth-century Antwerp and the Low Countries. It offered pleasure and prompted curiosity. It could assert the material satisfactions of craft or complicate visual narratives by nesting stories in paintings or other artworks. And it could signal the overarching mode of design, Gothic or antique, each with its own ideology. Ornament cut across the apparent divide between the vernacular and classicizing—at least as far as these poles have recently been intuited. It related art in Antwerp to the cultures of Rome and Fontainebleau, but also to that of its own local past. Ornament established links between different artistic media and, on occasion, even spoke for architecture itself in professional and lay discourse. It benefited such diverse exponents of the culture as Pieter Bruegel, Abraham Ortelius, Pieter Coecke van Aelst, Maerten de Vos, Frans and Cornelis Floris, and Lucas de Heere. Removed from the exigencies of decorum that governed most religious and secular imagery, ornament was free to express the untrammeled fantasy of the artist. This was especially true of the grotesque, that genre of ornament based on inventive combinations of animal and vegetal parts, a clear register of the artist's power of imagination and originality. For this reason, distinctive grotesques became a sort of secondary artist's signature.

Ornament offered different perspectives on the objects or images it inhabited. It could communicate hierarchy and dignity, wealth and power. It could also convey aesthetic value to an object of otherwise utilitarian service. And in many cases it transcended its assumed supplementary role and became a valid subject in itself. The self-conscious attention to species of ornament in the mid-sixteenth century problematized its status as a comfortable and subservient frame. The notion of ornament as essentially supplemental and the prejudice against ornamental excess are both children of the Enlightenment, particularly of Kant's aesthetics. Both ideas depend on a modern conviction of the work of art as an autonomous, aesthetically self-sufficient object, and both betray the fear and rejection of rococo ornament with its irrational and destabilizing effects. It is helpful to view early modern ornament outside of this perspective. Ornament might, thus, profitably be considered as a set of systems, each with its own rules. The Low Countries employed several of these constructs, which were given their distinctive inflections by the creative individuals who navigated the rich and intersecting cultures of the Netherlands.