1. Introduction

As “the most important trend in education” (The New Media Consortium, 2013: n.p.) over recent years, massive open online courses (MOOCs) have reshaped models of online education and have been integrated into innovative teaching practices in different fields and disciplines. The study of language MOOCs (henceforth LMOOCs) is a new, emerging field and refers to “dedicated Web-based online courses for second languages with unrestricted access and potentially unlimited participation” (Bárcena & Martín-Monje, Reference Bárcena, Martín-Monje, Martín-Monje and Bárcena2014: 1). Compared with traditional forms of language education, LMOOCs offer an innovative language learning experience in creating unlimited learning opportunities for a massive number of language learners. Since 2012, LMOOCs have become an enticing alternative to other types of online courses, with a wide range of languages on offer, innovative pedagogies, and resourceful language learning materials.

In recent years, LMOOCs have received attention as they are proliferating on MOOC platforms and websites around the world. Many MOOC platforms now offer a special category of language courses.Footnote 1 There are more than 200 LMOOCs from providers in Europe and the United States, for example. The British CouncilFootnote 2 (a government-funded organisation that promotes UK arts, culture, education, and the English language) has collaborated with FutureLearnFootnote 3 to provide English courses to improve learners’ English and broaden their knowledge of British history and culture. The earliest LMOOCs in China were developed in 2014, two years after the first LMOOC appeared in Europe. With the second largest number of higher education institutions in the world, China now has more than 500 LMOOCsFootnote 4 provided by more than 20 platforms, ranging from the biggest provider “iCourse” to other smaller ones. Table 1 shows the presence of LMOOCs on three internationally influential MOOC platforms and the three biggest Chinese platforms to offer LMOOCs (author’s own survey of these platforms, January 2021).

Table 1. The number of LMOOCs across the principal MOOC platforms

During the COVID-19 outbreak, with many countries issuing stay-at-home orders and millions of learners having to study online at home, LMOOCs, as an open, free resource, have become the ideal way for learners to continue with their language learning online.

Although LMOOCs are still “in the … early stage of development” (Bárcena & Martín-Monje, Reference Bárcena, Martín-Monje, Martín-Monje and Bárcena2014: 6), they are the subject of a growing body of research. The first notable initiative in the study of LMOOCs was the landmark book by Martín-Monje and Bárcena (Reference Martín-Monje and Bárcena2014), which was the first monographic volume to discuss LMOOC research and offered insightful analysis from a range of different perspectives. Later publications include the prospect and potential of the integration of MOOCs in language learning (Perifanou, Reference Perifanou2014a; Perifanou & Economides, Reference Perifanou and Economides2014; Qian & Bax, Reference Qian and Bax2017); the exploration of LMOOC participants’ motivation (Beaven, Codreanu & Creuzé, Reference Beaven, Codreanu, Creuzé, Martín-Monje and Bárcena2014); the introduction of new models of LMOOCs supported by innovative technologies (Teixeira & Mota, Reference Teixeira, Mota, Martín-Monje and Bárcena2014); self-directed learning in the context of LMOOCs (Luo, Reference Luo2017); and language teacher education in LMOOCs (Castrillo, Reference Castrillo, Martín-Monje and Bárcena2014; Manning, Morrison & McIlroy, Reference Manning, Morrison and McIlroy2014). Discussions around LMOOCs have focused on their potential and on practical, social, and technological issues. There has been less focus on the quality of LMOOCs, despite quality being a decisive indicator of the success of the courses.

As millions of people learn from LMOOCs and millions of dollars are invested in LMOOCs every year, there is a pressing need to establish benchmarks for quality assurance. Some studies have discussed topics such as “what constitutes an effective LMOOC” (Sokolik, Reference Sokolik, Martín-Monje and Bárcena2014) or the design of effective LMOOC learning environments (Perifanou, Reference Perifanou2014b; Read, Reference Read, Martín-Monje and Bárcena2014). These studies are related to quality issues, but the results are mostly based on MOOC creators’ experiences and reflections. There is limited empirical research into perceptions of what quality is in LMOOCs from learners’ perspectives. The present study investigates learners’ evaluations of Chinese LMOOCs, aiming to identify the key factors that determine the quality of an LMOOC from the learners’ perspectives. The following research questions guided the study:

-

RQ1: Which factors have influenced learners’ perceptions of LMOOCs?

-

RQ2: How do the key factors relate to each other to form a holistic quality criteria framework for LMOOCs?

-

RQ3: What specific quality indicators are involved in the evaluation of different types of LMOOCs?

2. Quality issues in MOOCs: Related studies

2.1 Studies on the quality issues of MOOCs

Quality is the condition that determines how effective and successful learning can take place (Creelman, Ehlers & Ossiannilsson, Reference Creelman, Ehlers and Ossiannilsson2014; Ehlers, Ossiannilsson & Creelman, Reference Ehlers, Ossiannilsson and Creelman2013). The quality of MOOCs is a critical indicator and prerequisite for the sustainable development of MOOCs. Although MOOCs offer an innovative learning experience, effective learning may be hindered by bad design, poor instructions, and inefficient assessment (Conole, Reference Conole2016; Sokolik, Reference Sokolik, Martín-Monje and Bárcena2014; Yuan & Powell, Reference Yuan and Powell2013). Consequently, several scholars have expressed their desire for quality benchmarks in MOOCs (e.g. Lowenthal & Hodges, Reference Lowenthal and Hodges2015; Morrison, Reference Morrison2016). Due to the unique features of MOOCs, such as their open, flexible nature, scholars argue that the quality criteria applied to MOOCs should not be the same as those applied to traditional university courses and should be manifested in new ways, especially in relation to technological and pedagogical perspectives around engaging participants to become active online learners (Creelman et al., Reference Creelman, Ehlers and Ossiannilsson2014; Downes, Reference Downes, Khan and Ally2014; Yousef, Chatti, Schroeder & Wosnitza, Reference Yousef, Chatti, Schroeder and Wosnitza2014).

Research on quality issues related to MOOCs has examined the key indicators of MOOC quality from different perspectives. Instructional design has always been considered a key element of the overall quality and pedagogic effectiveness of all kinds of courses (Merrill, Reference Merrill2013). However, there are limited studies on the instructional design quality criteria of MOOCs, and several have adopted criteria based on the first principles of instructionFootnote 5 (Aloizou, Villagrá Sobrino, Martínez Monés, Asensio-Pérez & García-Sastre, Reference Aloizou, Villagrá Sobrino, Martínez Monés, Asensio-Pérez and García-Sastre2019; Margaryan, Manuela & Littlejohn, Reference Margaryan, Manuela and Littlejohn2015; Watson, Watson & Janakiraman, Reference Watson, Watson and Janakiraman2017). Some studies have addressed technological issues to ensure the quality of MOOCs, suggesting that natural language processing, learning analytics, and assessment tools are key factors of the effectiveness of these courses (Cross et al., Reference Cross, Keerativoranan, Carlon, Tan, Rakhimberdina and Mori2019; Khalil, Taraghi & Ebner, Reference Khalil, Taraghi, Ebner and Carmo2016; Shukor & Abdullah, Reference Shukor and Abdullah2019; Yousef et al., Reference Yousef, Chatti, Schroeder and Wosnitza2014). Furthermore, attempts have been made to establish various kinds of quality rubrics or frameworks (Dyomin, Mozhaeva, Babanskaya & Zakharova, Reference Dyomin, Mozhaeva, Babanskaya, Zakharova, Kloos, Jermann, Pérez-Sanagustín, Seaton and White2017; Huang, Pei & Zhu, Reference Huang, Pei and Zhu2017; Ma, Reference Ma2018; Poce, Amenduni, Re & De Medio, Reference Poce, Amenduni, Re and De Medio2019; Stracke, Reference Stracke, Zaphiris and Ioannou2017; Wang, Zhao & Wan, Reference Wang, Zhao and Wan2017). The studies cited offer diverse understandings of what quality is in a MOOC, but to date, there are no universally accepted quality criteria for MOOCs.

2.2 The quality of MOOCs from learners’ perspectives

Most of the previous research has dealt with quality criteria in MOOCs based on a survey, a questionnaire, or an interview with professors and course designers, who are considered to be core stakeholders and can provide important suggestions for MOOC development. The viewpoints proposed by experts have been organised into an overall quality criteria framework for MOOCs in many studies (Bai, Chen & Swithenby, Reference Bai, Chen and Swithenby2014; Creelman et al., Reference Creelman, Ehlers and Ossiannilsson2014; Tong & Jia, Reference Tong and Jia2017). However, the quality indicators in these studies seem somehow arbitrary to us and have little in common with each other.

Compared with the emphasis placed on experts’ dominant role, learners’ perspectives have often been neglected in the investigation of MOOCs. As the recipients and target audience of MOOCs, learners are closely involved in the whole process of online delivery. They also play an inseparable role in quality assurance in MOOCs. Moreover, the interests and demands of learners usually determine the goal and development of MOOCs. Although the expertise of professional course designers is important in controlling and monitoring the quality of MOOCs, learners’ opinions of the courses are mirrors that reflect the effectiveness and eventual success of the courses. As a gap has been found in MOOC learners’ and designers’ intentions and experiences (Stracke et al., Reference Stracke, Tan, Teixeira, Pinto, Vassiliadis, Kameas and Sgouropoulou2018), there is a need to foreground learners’ perspectives and place learners at the centre of the quality measurement.

Uvalić-Trumbić and Daniel (Reference Uvalić-Trumbić and Daniel2013) suggested assessing the quality of MOOCs against the question, “What is it offering to the student?”. So, in order to identify the key factors of quality from learners’ perspectives, researchers should develop better metrics to understand what learners aim for and how they are interacting with MOOCs (Kernohan, Reference Kernohan2014; Pomerol, Epelboin & Thoury, Reference Pomerol, Epelboin and Thoury2015). The present study will draw on learners’ perceptions and evaluations of LMOOCs to identify the key factors that influence their assessment of LMOOCs.

3. Theoretical framework

The digital nature of MOOCs provides researchers with enormous data with fine granularity. Stickler and Hampel (Reference Stickler and Hampel2019) point out that there is great potential in the use of qualitative methodologies in online language learning studies. They emphasise that more attention should be paid to the learning process, such as learners’ reactions and interactions in their online language learning. The present study adopts a qualitative method in the study of quality issues of LMOOCs, aiming to reveal a real picture of learners’ perceptions of LMOOCs.

The grounded theory method (GTM) comprises a systematic, inductive, and comparative approach for qualitative research. In contrast to the top-down deductive research method, GTM builds empirical checks with a bottom-up approach and leads researchers to abstract new concepts and ideas starting from empirical facts. Researchers can thus find the concepts reflecting the essence of phenomena based on systematic data collection and then construct the relevant theory through the connections between these concepts. The term “grounded theory” is used in various ways. Sometimes it refers to the results of the research; in other cases, it refers to the method used in the research (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). In the current study, we have used GTM to represent the research method we have adopted.

Grounded theory was first proposed by Glaser and Strauss in Reference Glaser and Strauss1967. There are various schools of grounded theory; among these, programmatic GTM is most widely used. The present study adopts the coding paradigm used by this school of GTM, and also incorporates the logic of abduction, not just induction, in the reasoning and analysing of data (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006, Reference Charmaz, Holstein and Gubrium2007; Reichertz, Reference Reichertz, Bryant and Charmaz2007).

A study using GTM is likely to begin with a question or just with the collection of qualitative data. As researchers review the data collected, repeated ideas, concepts, or elements become apparent and are tagged with codes. Codes capture patterns and themes and cluster them under a “title” that evokes constellations of impressions, which are then grouped into concepts, and then into categories. These categories may become the basis for new theories.

Generally speaking, three steps of data coding are involved in most GTM research. Open coding is conceptualising on the first level of abstraction. Written data from field notes or transcripts are segmented, detected, and separated into different categories. The second level of abstraction is axial coding, the purpose of which is to combine the concepts that are clearly related to each other, and to construct a unique category in that each clearly related code can be compared among different categories. The third and most abstract procedure is called selective coding. At this level, researchers need to construct a core category that links all the others. As a result, selective coding is classified as a process of integration, the function of which is to give coherence and coordination to the data as a whole. GTM provides a set of clear and systematic strategies to help researchers think, analyse, organise data, excavate, and build theory. Figure 1 shows the procedures involved in the process of GTM, and our study adopts this method in our analysis.

Figure 1. Procedures of the grounded theory method (authors’ diagram)

GTM has been applied in studies of the effectiveness of MOOCs, student retention in online courses, and quality design in MOOCs (Adamopoulos, Reference Adamopoulos2013; Gamage, Fernando & Perera, Reference Gamage, Fernando and Perera2015; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhao and Wan2017), as it enables researchers to go beyond the data and form a holistic picture of these courses. To investigate learners’ perception of the quality of LMOOCs, the present study adopts GTM to examine these participants’ evaluations on the MOOC platforms. Drawing on GTM, this study aims to segment, compare, and analyse learners’ evaluations as they are converted from codes to categories, and to abstract learners’ separate comments on the LMOOCs into major concepts. This will help to build a clear and well-structured quality criteria framework of LMOOCs using a bottom-up method.

4. Methodology

4.1 Research design

As a new language learning context, MOOC platforms provide abundant feedback from learners shown in evaluative comments throughout a course. These comments reflect the quality of online courses and provide valuable data to explore the effectiveness of LMOOCs. Generally speaking, learners’ comments are likely to be more wide-ranging, objective, and comprehensive when given spontaneously during a course than when given in an exit survey. Exit surveys are guided by their creator’s beliefs and assumptions and limited by their design: usually small numbers of open questions and predetermined set questions. They do not furnish such rich data.

The present study adopts a GTM approach and conducts a systematic analysis of LMOOCs learners’ evaluation comments. This study includes three steps of analysis, which provide answers to three research questions step by step. The first step is to uncover all the factors that have influenced learners’ evaluation of LMOOCs and capture key quality indicators that are commonly emphasised in most evaluations. The second step is to ascertain the relationship between key quality indicators and to establish an overall quality criteria framework for LMOOCs. The last step is to compare learners’ evaluations of five types of LMOOCs, aiming to identify specific quality criteria for each type of language course.

4.2 The setting

The study was carried out on China’s biggest MOOC platform “iCourse”. Established in 2014, iCourse is one of the earliest MOOC platforms in China. Up to January 2021, there were more than 6,000 free online courses on the platform provided by nearly 700 Chinese universities. Among these courses, there are 380 LMOOCs covering a wide range of themes, including language skills, cultural studies, and English for specific purposes. Each LMOOC accommodates from hundreds to tens of thousands of learners each semester. Usually, the courses provided by top universities and famous professors attract more students, but some good-quality courses from ordinary universities are also popular.

Among all the LMOOCs on the iCourse platform, English as a second language (ESL) courses are the most popular ones, with large numbers of learners. In order to investigate how these learners evaluate the quality of LMOOCs in China, the present study selected 10 popular Chinese LMOOCs belonging to five types of ESL courses. The 10 LMOOCs include two ESL speaking courses, two ESL writing courses, two ESL reading courses, two cultural studies courses, and two ESL integrative skills courses. The 10 courses are all among the top three in their own types of course in terms of the number of learners, and they are all open to the public for at least two years (four semesters). They are representative of the most typical and most popular LMOOCs in China.

On the cover page of every course there is a category listing all the evaluation comments from learners, accompanied by learners’ ratings ranging from one to five starsFootnote 6 (with five being the top). All of the 10 LMOOCs received more than 300 comments from learners. The layout of the web page with learners’ comments on the platform is shown in Figure 2. It is from one ESL speaking course in the present study.

Figure 2. Layout of the web page with learners’ comments on the “iCourse” platform

4.3 Data collection

In order to guarantee a balanced and detailed investigation of learners’ comments on the quality of the 10 LMOOCs, the study aimed to analyse 100 comments from each course. First, the researchers removed irrelevant comments from the entire dataset such as “I like this course”, “This University is really good”, or “I will recommend the course to others”. Even if these were positive evaluations of the course, they had nothing to do with quality issues and so were not included in the analysis. From the remaining comments, 100 were selected from each course and they were not randomly chosen. The study used an equidistant sampling method. For example, if there are 500 comments left for one course, the researcher picks the 1st, the 6th, the 11th, the 16th, and so on. Altogether, the study collected 1,000 learners’ comments relevant to quality issues in the 10 LMOOCs.

The study made use of NVivo 12 in the analysis of learners’ comments. Some of the comments were written in English but most were written in Mandarin Chinese. The researcher coded the comments according to their meaning regardless of the language used, focusing on the comments’ relationship with quality issues in the course.

4.4 Data analysis

4.4.1 Reframing the quality criteria of LMOOCs from learners’ perspectives

First, in the open coding of the raw data, the study coded the comments into different nodes containing initial indicators of the quality of the courses. Twenty-five initial indicatorsFootnote 7 were found in 1,000 comments and they represented learners’ basic perceptions of the quality of the LMOOCs. They were labelled as A1–A25 in open coding, such as overall quality of the course (A1), teachers’ oral English proficiency (A2), teachers’ personal image (A3), teachers’ teaching style (A4). The 25 factors were basic-level evaluations of the quality of LMOOCs, combining learners’ understanding of the pedagogical, technological, and social features of LMOOCs. Table 2 shows four of the 25 initial indicators, their statements, and example comments.

Table 2. Initial indicators and statement in quality evaluations of LMOOCs

In the axial coding of the data, the study mixed qualitative and quantitative methods in analysing the ratio and percentage of initial indicators in 2,062 instances of comments containing 25 indicators.Footnote 8 Among the 25 initial indicators, the study identified the top five indicators that appeared most frequently in learners’ comments. These five indicators are those that learners mentioned the most and they carry considerable weight in learners’ evaluations of the quality of LMOOCs (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Top five indicators of quality of LMOOCs from learners’ perspectives

The next step was to remove indicators that have a weak relationship with quality issues in LMOOCs. The frequency of five indicators in the total 2,062 instances was less than 2%, including the teacher’s image (A3 0.48%), availability of videos (A12 0.1%), the management of discussion forums (A18 1.78%), issuing of certificates (A19 1.03%), and the stability of the platform (A25 0.97%). Because Indicator A1 (overall quality evaluation of LMOOCs) does not reflect any specific quality issues, it was excluded from our analysis before selective coding.Footnote 9

After deleting these six indicators, the study analysed and established the relationship between the 19 initial indicators. In the last step of the analysis, selective coding helped to categorise the 19 indicators into five key concepts, which represented the most important aspects of the quality issues in LMOOCs. Thus, a quality criteria framework for LMOOCs was established consisting of five major types of quality criteria on the second level, including teacher/instructor criteria, teaching content criteria, pedagogical criteria, technological criteria, and teaching management criteria. Each category of quality criteria included three to five quality indicators. The following framework (Figure 4) reflects some commonalities with quality assurance frameworks for online courses (e.g. Tong & Jia, Reference Tong and Jia2017; Yousef et al., Reference Yousef, Chatti, Schroeder and Wosnitza2014) but has included special features of language courses.

Figure 4. Quality criteria framework of LMOOCs from learners’ perspectives

4.4.2 Revealing specific quality criteria for different types of LMOOCs

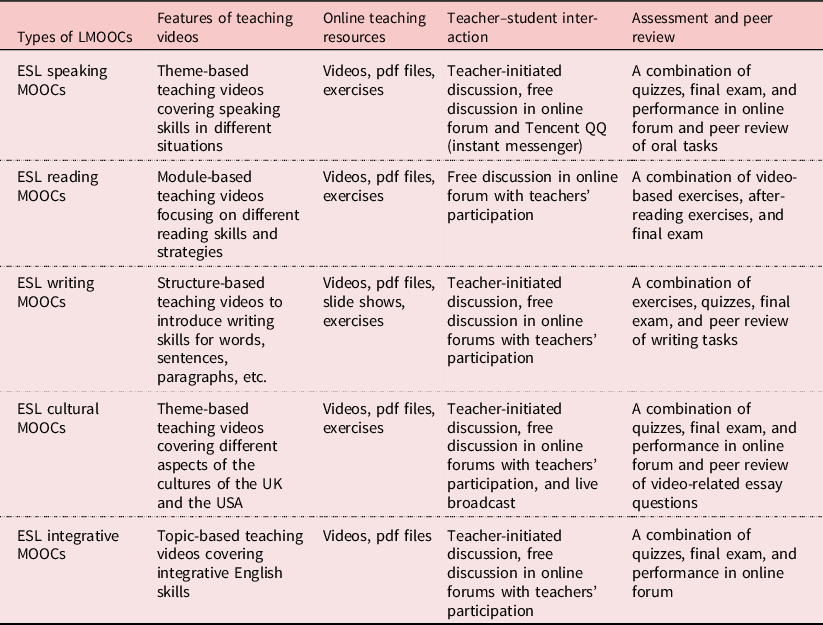

Competency-based language teaching focuses on what “learners are expected to do with the language” (Richards & Rodgers, Reference Richards and Rodgers2001: 141). Also, language learning is skill based and should emphasise the practice of receptive, productive, and interactive capabilities. Teixeira and Mota (Reference Teixeira, Mota, Martín-Monje and Bárcena2014) highlight the importance of competency-based learning in online language education, in which language skills sets should be broken into smaller competencies. For example, ESL courses for speaking, writing, and reading provide different competencies requiring different knowledge and skills. The present study analysed 10 LMOOCs belonging to five types of ESL courses, the basic information of which is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Basic information of the five types of LMOOCs in this study

Based on the information in Table 3, our analysis sought to identify learners’ quality criteria for the five types of LMOOCs. In the following section, the top five initial indicators for each type of ESL MOOC are presented to show learners’ specific quality criteria for different LMOOCs.

First, the researcher analysed learners’ comments from two ESL speaking MOOCs. The two courses were “College English Speaking” and “Oral English & Public Speaking”. They are the two most popular English-speaking MOOCs on the iCourse platform.Footnote 10 In 200 comments from ESL speaking MOOCs, we identified 578 instances containing 19 indicators. Table 4 shows the top five quality indicators in learners’ comments from the two ESL speaking courses. Learners cared most about the effectiveness of the oral English teaching content (A9) because they expect to obtain English speaking skills directly from teaching content. They are also highly concerned about teachers’ oral English proficiency (A2) due to the teacher’s role as model in speaking courses. They also look for good instructional design (A8), rich teaching content (A10), and good teaching ability (A5) in ESL speaking MOOCs.

Table 4. Top five quality indicators of ESL speaking MOOCs

Second, the two ESL writing MOOCs are “How to Write an Essay” and “Basic English Writing Skills”. They are now the most popular English writing MOOCs in China.Footnote 11 In 200 comments from ESL writing MOOCs, we identified 416 instances containing 19 indicators. Table 5 shows the top five quality indicators of the two courses. Chinese ESL learners lack English writing practice due to limited English teaching at school and want to learn useful writing content in these courses. They also paid attention to a teacher’s teaching ability (A5), because skilled teachers can present abstract writing strategies in an effective way. Learners attached great importance to the assignment of exercises and teachers’ feedback (A17). It is a common belief that practice makes perfect, so learners consider writing tasks such as exercises and peer review an important component of ESL writing MOOCs.

Table 5. Top five quality indicators of ESL writing MOOCs

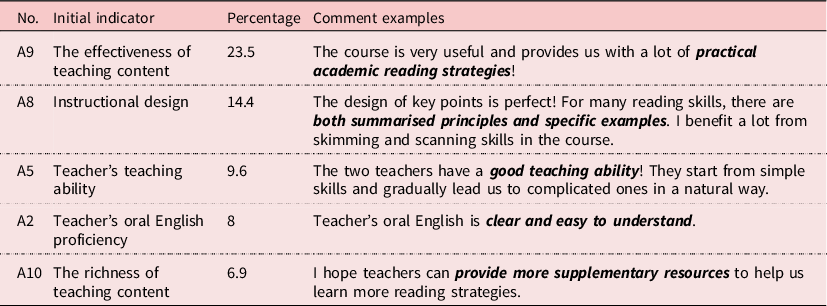

Third, the two ESL reading MOOCs are “College English Academic Reading” and “English Critical Reading”.Footnote 12 The two are among few but popular ESL reading LMOOCs. In 200 comments from ESL reading MOOCs, we identified 374 instances containing 19 indicators. Table 6 shows the top five quality indicators of ESL reading courses. Learners attached great importance to the effectiveness of teaching content (A9) and expected to learn more reading skills and strategies. As there is a big variety of reading skills, learners highly valued a clear and well-organised instructional design (A8). Learners also emphasised the indicators of teachers’ teaching ability (A5), teachers’ oral English proficiency (A2), and rich teaching content (A10) in ESL reading MOOCs.

Table 6. Top five quality indicators of ESL reading MOOCs

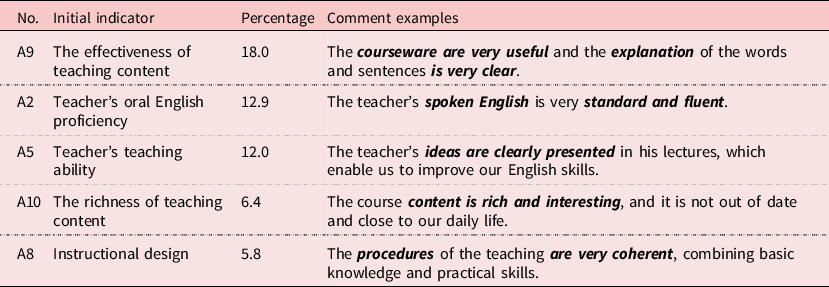

Next, the two ESL cultural studies MOOCs are “Impressions of the UK and the United States” and “A Survey of the UK and the United States”. The two courses are the most popular cultural studies MOOCs with the largest number of learners in China.Footnote 13 In 200 comments from ESL cultural studies MOOCs, we identified 476 instances containing 19 indicators. Table 7 shows the top five quality indicators of ESL cultural studies MOOCs. Compared with ESL courses focusing on language skills, learners of the two cultural studies courses cared more about the effectiveness, richness, and good taste of teaching content (A9, A10 and A11). In ESL cultural studies courses, the width and depth of foreign cultural knowledge meant a lot for learners. They also cared about instructional design (A8) and teachers’ oral English proficiency (A2) in ESL cultural studies MOOCs.

Table 7. Top five quality indicators of ESL cultural studies MOOCs

Finally, the two ESL integrative skills MOOCs are “College Integrative English Course” and “Advanced College English”. The two courses are very popular with learners because they provide comprehensive ESL knowledge and skills.Footnote 14 In 200 comments from ESL integrative skills MOOCs, we identified 432 instances containing 19 indicators. Table 8 shows the top five quality indicators of ESL integrative skills MOOCs. Learners aimed to improve their comprehensive English skills and highly evaluated the effectiveness of teaching content (A9). As integrative English courses are what students usually learn on campus, they easily associated the MOOCs with their offline courses. Learners tended to have a requirement for teachers’ oral English proficiency (A2) and teaching ability (A5) in MOOCs and looked for rich teaching content (A10) and good instructional design (A8) in ESL integrative skills MOOCs.

Table 8. Top five quality indicators of ESL integrative skills LMOOCs

5. Discussion

Based on a qualitative GTM approach, the present study analysed 1,000 learners’ evaluation comments of 10 LMOOCs. In order to find out the most decisive factors in learners’ perceptions of LMOOCs, the results reveal that 25 factors have influenced learners’ evaluations of the quality of LMOOCs. Among these factors, 19 indicators were found to be highly relevant to the evaluation of quality in LMOOCs and were taken into consideration in the establishment of quality criteria for LMOOCs.

As for the relationship between these decisive quality indicators, the present study determines the connections between 19 indicators and formulates a holistic quality criteria framework (shown in Figure 4). Previous scholarship has mostly divided the quality criteria of MOOCs into two to three categories including pedagogical criteria, technical criteria, and sometimes teachers’ competence criteria (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Chen and Swithenby2014; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Pei and Zhu2017; Yousef et al., Reference Yousef, Chatti, Schroeder and Wosnitza2014). They are established in the general framework of MOOCs, without taking a close look at LMOOCs.

In the present study, teacher/instructor criteria for LMOOCs (shown in Figure 4) include factors that are related to the teacher’s competence, such as oral language proficiency, teaching style, and teaching ability. Other criteria related to the teaching process, such as teaching methods and instructional design, are grouped into pedagogical criteria. Contrary to the definition of “learner support” as technological support in other studies (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Pei and Zhu2017; Tong & Jia, Reference Tong and Jia2017; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhao and Wan2017), the present study is more concerned about the problems learners encounter in LMOOCs and teachers’ help and solutions for these problems. Some students hoped teachers would slow down and provide more explanations when introducing challenging topics. Thus, the learner support indicator is classified into pedagogical criteria in this study.

As for online learning environments, especially MOOC platforms, the present study defines them as technological criteria, in line with Yousef et al.’s (Reference Yousef, Chatti, Schroeder and Wosnitza2014) quality system, but it differs in its classification of issues related to video materials into technological criteria, even though “the quality of video” indicator is grouped into pedagogical criteria in some previous studies (Yousef et al., Reference Yousef, Chatti, Schroeder and Wosnitza2014). Tong and Jia (Reference Tong and Jia2017) grouped all the platform issues into “learner support” criteria. The present study defines the main quality criteria using parallel names, which are on the same level of abstractness.

The other two quality criteria, namely teaching content criteria and teaching management, focus on the quality of LMOOCs’ content and management respectively. This study groups the courseware and the supplementary resources into the category of teaching content criteria, whereas the quality of videos is related to the visual characteristics of the video and is classified into the technological criteria. As for the teaching management criteria, the study includes the aspects involved in the implementation of online language teaching, such as teachers’ engagement and interaction with students, the assignment of exercises and teachers’ feedback, as well as the implementation of peer review and online assessment of the course. Teachers’ responsibility in this criteria is different from the one included in teachers’ criteria and pedagogical criteria because the former focuses on the teacher’s role in the implementation of the LMOOCs instead of the teacher’s personal quality or the teaching strategies or methods as designed in the curriculum.

The present study makes a more in-depth investigation to unveil the specific quality criteria of five types of LMOOCs, including ESL speaking, reading, writing, cultural studies, and integrative skills MOOCs. It is noteworthy that for all these types of LMOOCs, the most decisive quality indicator is “the effectiveness of teaching content”. Even though they share the same indicator, the analysis reveals that what learners care about in the five types of LMOOCs is different. For learners of ESL MOOCs for speaking, writing, and reading, “effectiveness” refers to the ability to boost their oral English, to grasp more writing skills, and to learn more reading strategies respectively. However, for ESL cultural studies MOOCs, “effectiveness” refers to the ability to broaden learners’ horizons and enrich their world knowledge. And for ESL integrative skills MOOCs, it means to have comprehensive English competence in vocabulary, grammar, reading, and writing. The second quality indicator that the five types of LMOOCs share is instructional design of the course. It seems that this is consistent with previous studies that have emphasised the importance of effective instructional design (Aloizou et al., Reference Aloizou, Villagrá Sobrino, Martínez Monés, Asensio-Pérez and García-Sastre2019; Margaryan et al., Reference Margaryan, Manuela and Littlejohn2015; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Watson and Janakiraman2017).

Apparently, the quality criteria for the five types of LMOOCs are different in many aspects. First, teachers’ oral language proficiency is universally agreed to be a key factor in the quality criteria of ESL speaking MOOCs. Second, the teachers’ teaching ability is held as an important factor for both ESL writing and reading MOOCs. Chinese learners suffer from the lack of reading and writing practice in face-to-face ESL reading and writing courses and they long for new teaching methods in these ESL courses (Lu, Ja & Wu, Reference Lu, Ja and Wu2016; Wang, Reference Wang2014). For ESL writing MOOCs, learners attached great importance to peer review writing tasks and looked forward to the teacher’s timely feedback. This suggests a need for teachers to carefully consider writing tasks in the design of online writing MOOCs. Third, learners of ESL cultural studies MOOCs valued high-quality teaching content, as these courses provided a window for learners to know about the outside world, and the richness of content is the decisive factor in their quality criteria. Compared with the general quality criteria across the five types of LMOOCs, the specific criteria for each type of LMOOC was unique and depended on their different teaching objectives and the competences that learners were supposed to obtain.

6. Conclusion

In the past decade, LMOOCs have emerged and developed as a new form of online language education. With the proliferation of LMOOCs in recent years, there is a pressing need to establish quality criteria for measuring the effectiveness of LMOOCs. This enables learners from all countries to formulate a systemic and scientific judgement in choosing an LMOOC.

Some scholars have pointed out the large number of unresolved problems of MOOCs, such as high dropout rates or variable educational quality, and emphasise the student’s role in judging the quality of MOOCs “from the inside” (Finger & Capan, Reference Finger and Capan2014; Kinash, Reference Kinash2013). The present study aims to investigate the quality criteria of LMOOCs from learners’ perspectives. With the data collected from 1,000 evaluations from ESL learners on China’s biggest MOOC platform iCourse, our study identifies 19 indicators that have shaped learners’ evaluation of the quality of LMOOCs. The factors relate to each other and form a holistic quality criteria framework for LMOOCs, which consists of five categories of major quality criteria: teacher/instructor criteria, teaching content criteria, pedagogical criteria, technological criteria, and management criteria.

It is widely agreed that the quality enhancement of MOOCs helps to create a good learning experience (Conole, Reference Conole2016; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Ossiannilsson and Creelman2013). This study makes suggestions for the recalibration of the design of LMOOCs and provides clues for improving the quality of LMOOCs. The study captures and identifies quality indicators of LMOOCs for the first time and identifies specific criteria for five types of LMOOCs corresponding to different language competences.

The results of this study are consistent with some earlier views about the success of LMOOCs, all emphasising students’ engagement, teacher presence, and effective instructional design (Bárcena & Martín-Monje, Reference Bárcena, Martín-Monje, Martín-Monje and Bárcena2014; Sokolik, Reference Sokolik, Martín-Monje and Bárcena2014). Our empirical research covers a wider range of details in learners’ experience and lays a foundation for the further exploration of the effectiveness of LMOOCs.

Although the study is limited in scope and only Chinese LMOOCs are involved, the results shed light on general problems and challenges faced by all LMOOCs. The findings in the study help to bridge the gap between course designers’ and learners’ evaluations of LMOOCs. Course designers, teachers, and MOOC platforms need to use data effectively to work together to make collaborative contributions to promote the sustainable development of LMOOCs in the future.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344021000082

Ethical statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. All the data in the present study have been collected and analysed anonymously.

About the authors

Rong Luo is an associate professor of Hangzhou Normal University. Her studies focus on technology-enhanced foreign language learning and teaching, especially the design, quality, and effectiveness of language MOOCs.

Zixuan Ye is a postgraduate student in the School of International Studies of Hangzhou Normal University. Her primary research interest is internet-mediated discourse analysis and online language learning.

Author ORCIDs

Rong Luo, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5069-6200

Zixuan Ye, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6867-2474