1 Introduction

As the world today is experiencing an erosion of boundaries and increasing global interconnectedness, intercultural interactions are more frequent and observable in our current lives. In order to help students navigate effectively through complex recent global developments, language education systems strive to equip them with the necessary skills to engage effectively in global communication networks and (intercultural) communicative language practices (Alptekin, Reference Alptekin2002; Thorne, Reference Thorne2003). Intercultural (communicative) competence (ICC) has, therefore, gained an important status in language education worldwide, as the cultivation of this competence is designed to help language learners communicate and negotiate successfully with people from different backgrounds (Byram, Reference Byram1997). Producing interculturally competent individuals/speakers is an important issue, as linguistic competence by itself does not predict successful communication with other cultures (Schenker, Reference *Schenker2012). Teachers of second/foreign languages are thus expected to find sound ways to integrate ICC into their language education, since “the intertwined relationship between language and culture is central to language learning and teaching” (Chen & Yang, Reference *Chen and Yang2016 [2014]Footnote 1 : 263). However, not every language student has a chance to communicate with people from diverse backgrounds, although the necessity of intercultural communication has been underscored for the experiential development of ICC.

With regard to helping language learners improve their ICC skills as well as their language skills, telecollaborative projects have opened up new avenues by designing and implementing online intercultural collaborative environments. By doing so, learners are provided with an opportunity to communicate in the language(s) of choice with people from diverse “linguacultures” in a virtual collaborative environment that has been designed to stimulate collaborative tasks and intercultural exchanges (Godwin-Jones, Reference Godwin-Jones2013). In that regard, telecollaborative learning can be framed as “an embedded, dialogic process that supports geographically distanced collaborative work through social interaction, involving a/synchronous communication technology so that participants co-produce mutual objective(s) and share knowledge-building” (Sadler & Dooly, Reference Sadler and Dooly2016: 402). Guth and Helm (Reference Guth and Helm2010: 14) maintain that:

Telecollaboration is generally understood to be internet-based intercultural exchange between people of different cultural/national backgrounds, set up in an institutional context with the aim of developing both language skills and intercultural communicative competence (as defined by Byram, Reference Byram1997) through structured tasks.

Telecollaborative projects, therefore, draw mainly upon digital tools such as email services, discussion forums, instant messaging, and audio- and videoconferencing (Chun, Reference Chun2015; Guth & Helm, Reference Guth and Helm2010; Lee & Markey, Reference *Lee and Markey2014) and can take place in different settings such as the classroom, computer lab, home, and so on.

Establishing different types of telecollaborative designs may give rise to improved language skills and ICC (Lee & Markey, Reference *Lee and Markey2014; Schenker, Reference *Schenker2012). In addition to helping language learners develop intercultural, intracultural, and language skills, telecollaboration can also assist learners to develop their electronic or digital literacies (Guth & Helm, Reference Guth and Helm2010). The goals of telecollaboration, therefore, are to enrich language, digital literacy, and intercultural and intracultural learning.

Since such telecollaborative developments have gained more importance recently (O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2016), existing studies stress the need for further research and practice in technology-oriented intercultural and language learning environments (Lee & Markey, Reference *Lee and Markey2014; O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2007; Perry & Southwell, Reference Perry and Southwell2011). There is also a limited number of research reviews on this issue. Carney (Reference Carney2006) revealed the impact of telecollaboration on intercultural learning in a single country, Japan. Chun (Reference Chun2015) focused particularly on Cultura-based projects (Furstenberg, Levet, English & Maillet, Reference Furstenberg, Levet, English and Maillet2001) as well as culture and language learning in higher education through telecollaboration. However, Chun (Reference Chun2015) lacked a systematic coverage of recent telecollaborative projects, thereby lacking an explicit intention to reveal recent issues. Çiftçi (Reference Çiftçi2016) reviewed the role of computer-based digital technologies in intercultural learning; however, his focus was only on the intercultural issues and not on language learning aspects. Moreover, Çiftçi did not have a specific focus on telecollaborative projects; rather, he chose to investigate the role of digital technologies in intercultural learning. On the other hand, O’Dowd and Ritter (Reference O’Dowd and Ritter2006) reviewed “failed communication” in telecollaborative projects, so their micro-focus was not on culture and language learning in a broader sense. Overall, these four review studies did not present a systematic attempt to show recent observable patterns and emerging issues specific to the telecollaborative studies from different country contexts.

Two final review studies are rather closer to the one at hand. Lewis and O’Dowd (Reference Lewis and O’Dowd2016: 22) concentrated on the contributions of online exchanges particularly with respect to “(a) second language development, (b) intercultural communicative competence and (c) learner autonomy by carrying out a systematic review of empirical research findings in university class-to-class telecollaborative initiatives”. They covered a broad range of studies that have been conducted since the 1990s. On the other hand, O’Dowd (Reference O’Dowd2016: 292) “review[ed] briefly [emphasis added] the recent past and the ‘state of the art’ in telecollaborative research and practice”, with greater focus on the studies presented at the 2016 Telecollaboration in Higher Education conference. With a slightly different approach from Lewis and O’Dowd (Reference Lewis and O’Dowd2016) and O’Dowd (Reference O’Dowd2016), the review study presented here examines the interconnected nature of language and culture in intercultural online exchanges and aims to reveal recent observable patterns and emerging issues. In addition, different reviewers can reveal different dimensions or patterns around a literature phenomenon (Galvan, Reference Galvan2013); therefore, different synthesis or review studies in rapidly evolving research and practice areas such as telecollaboration could be worthwhile efforts as they might bring new perspectives and “make the familiar strange”, or vice versa.

This synthesis study thus aims to fill a review gap by concentrating on recent observable patterns and emerging issues regarding intercultural and language learning through telecollaborative projects. However, the study limits its scope to the two main goals of telecollaboration: ICC and language learning (Guth & Helm, Reference Guth and Helm2010). Online or digital literacy skills are not within the scope of this study, as the synthesis concentrates on the intertwined relationship between language and culture. The four major questions are:

∙ What are the focal research points of telecollaborative projects in terms of language and intercultural learning?

∙ What type of participants and contexts are involved in telecollaborative projects?

∙ What types of technologies are used in telecollaborative projects?

∙ What are the major, observable patterns and emerging issues in terms of language and intercultural learning through telecollaboration?

In accordance with the answers to these questions, the current study, with its modest scope, aims to offer an overview of the studies that were published between 2010 and 2015. It examines focal research points, participant profiles, context types, observable patterns, and emerging issues, all in respect to language and intercultural learning through telecollaboration, and to inspire researchers to look for further directions in the field.

2 Research method

The research on telecollaborative projects has recently benefited from both quantitative and qualitative paradigms (Lewis & O’Dowd, Reference Lewis and O’Dowd2016), and, accordingly, this study chose to adopt a qualitative synthesis of both quantitative and qualitative research (Baran, Reference Baran2014; Suri & Clarke, Reference Suri and Clarke2009). Such an interpretive qualitative approach to meta-synthesis aims to help synthesists reveal the benefits of accumulated qualitative and, possibly, quantitative findings (Walsh & Downe, Reference Walsh and Downe2005). This type of synthesis, in fact, “is not a trivial pursuit, but rather a complex exercise in interpretation: carefully peeling away the surface layers of studies to find their hearts and souls in a way that does the least damage to them” (Sandelowski, Docherty & Emden, Reference Sandelowski, Docherty and Emden1997: 370). That said, this qualitative meta-synthesis of qualitative and quantitative findings aims to offer refreshed interpretations with “the least damage to” the particularities around the phenomenon at hand. Overall, the study designs an environment where individual studies are synthesized into a more abstract level in which multidimensions, varieties, and complexities are disclosed. The resulting analysis, therefore, covers more than a single study can provide (Hammersley, Reference Hammersley2001).

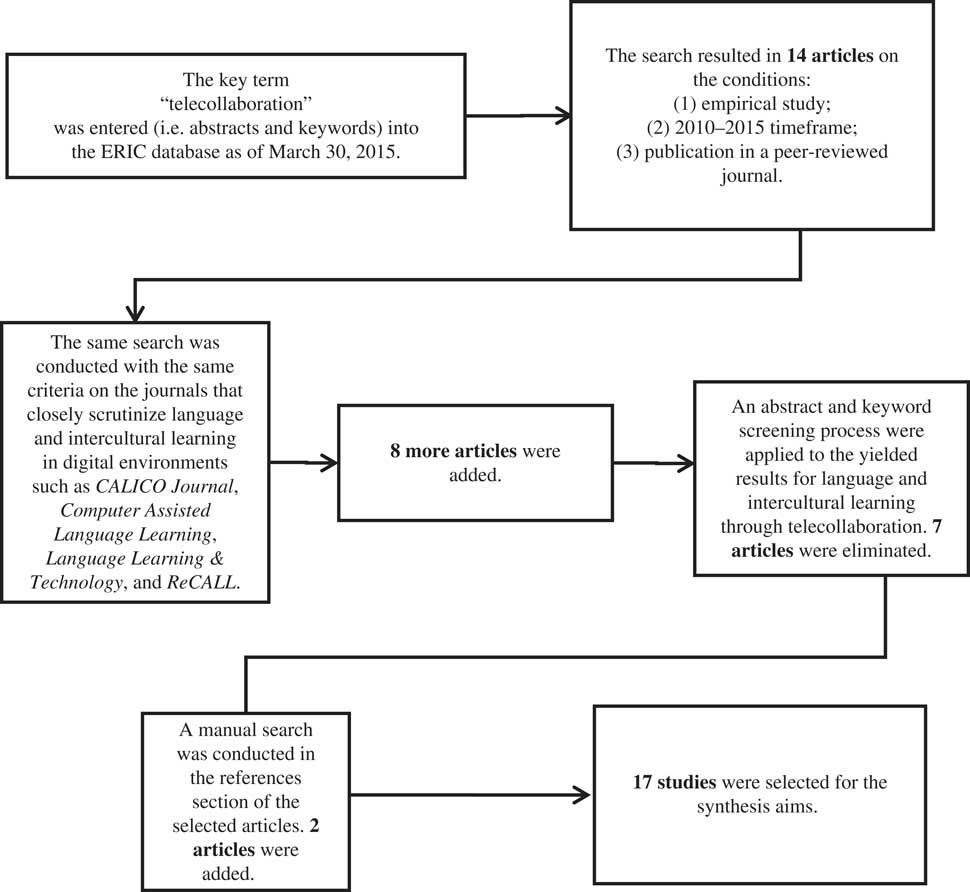

In order to achieve the aims of the synthesis, this study methodologically draws on a number of studies on the issue, namely Baran (Reference Baran2014), Çiftçi (Reference Çiftçi2016), and Suri and Clarke (Reference Suri and Clarke2009). This study, as a qualitative meta-synthesis, has not neglected the following systematic steps: problem formulation, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and interpretation of the results (cf. Cooper & Hedges, Reference Cooper and Hedges2009). In order to locate studies for the aims given, a number of systematic micro-steps were also followed (see Figure 1 for a summary of the selection process). The time period was set as 2010 and 2015, covering a 5-year-long, relatively recent period.

Figure 1 The literature search process and selection criteria

On the other hand, the study excluded studies on tandem language learning because the focus was more on the explicit sociocultural and intercultural collaborative aims rather than on the tandem exchanges, although such exchanges are also known to promote language and intercultural learning (O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2016). Therefore, the study conducted by Chen, Shih, and Liu (Reference Chen, Shih and Liu2015 [2013]), which involved only Taiwanese students from different institutions, and O’Dowd’s (Reference O’Dowd2013) research, which investigated barriers in telecollaboration and possible strategies to overcome these barriers, were not included in the final list of articles. The studies conducted by Fuchs, Hauck and Müller-Hartmann (Reference Fuchs, Hauck and Müller-Hartmann2012), and Guth and Helm (Reference Guth and Helm2012), which concentrated on developing multiliteracy skills, were also not included in the review process due to the sole focus on language and intercultural learning. And because only empirical studies were included in the synthesis processes, Negueruela-Azarola’s (Reference Negueruela-Azarola2011) theoretical paper on the motivational dynamics of one individual was also rejected here.

An analytic synthesis table was created for the final list of articles, which were coded under the following categories: focus of the study, participants, technologies used, and, country context (see Appendix A). In addition to this analytic table, the major findings of the studies in terms of intercultural and language learning were included as data. Although the table paved the way for the identification of emerging research trends, the research findings helped this study identify key and critical issues among telecollaborative projects. These major themes in the literature were synthesized after a qualitatively emergent/evolving and interpretive coding process.

The coding process offered by Thornberg and Charmaz (Reference Thornberg and Charmaz2014) was adopted to synthesize emerging issues and observable patterns. Their coding process is called constructivist grounded theory (GT). This process is usually applied in order to claim a theory grounded in the empirical data. However, for this synthesis study, the coding process alone was taken into account due to its flexible and constructivist nature. According to GT, the coding process includes initial and focused coding stages. In this paradigm, the researcher initially reads the data line by line and codes it using a constant comparison method to compare data with data, data with code, and code with code in order to keep a closer eye on the emerging differences and similarities. Then, in the focused coding stage, the main points are captured and synthesized. In this study, the main findings of telecollaborative projects were first extracted as they were reported in the studies, and then coded by the researcher with respect to language and intercultural learning using the GT coding processes. A representative coding sample that shows a small portion of the entire coding and analysis process is provided in Appendix B. Finally, the process yielded an “analytic story” of the literature under six broad themes as outlined in the following.

3 Findings

This study first investigated research trends within its scope, then, following the coding processes, identified the main themes that emerged from the studies themselves. The first theme reported the participants’ overall views on their telecollaborative experiences. Other themes concentrated on the details of language and intercultural learning within telecollaborative projects. However, some other issues such as challenges and needs were also salient in the literature; therefore, they were also reported under separate headings. The final themes are thus given as (1) research trends, (2) the participants’ overall views on their telecollaborative experiences, (3) language learning through telecollaboration, (4) intercultural learning through telecollaboration, (5) the challenges experienced within the telecollaborative projects, and (6) the needs for further effective telecollaboration.

3.1 Research trends

3.1.1 The applied technology types and environments designed

Nine of the 17 studies benefited from more than one digital tool to design online intercultural environments depending on their own contextual considerations. This subtheme, however, does not aim to compare the tools for their effectiveness, but instead describes an overall picture of technological choices. Figure 2 provides an overview of the favored tools in telecollaborative studies. Videoconferencing, email exchanges, learning management systems, and blogs were the most frequently used tools among the studies, followed by text-based chat and discussion boards. These favored tools offer both asynchronous and synchronous communication, which reflects efforts to diversify the means of communication away, even though asynchronous tools still seem to be dominant on the whole (Lewis & O’Dowd, Reference Lewis and O’Dowd2016). Other tools such as video recording, wikis, virtual worlds, and podcasting were used to enrich the quality and effectiveness of exchanges between people from different countries or cultural contexts. Microblogging (Twitter) was used only once in the study by Lee and Markey (Reference *Lee and Markey2014) alongside podcasting and blogging; a file-hosting service (Dropbox) was used by Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban (Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]) for sharing files with the instructors and with other participants. Although they may not be viewed as recent technologies, TV series and sitcoms featured in Pérez Cañado (Reference *Pérez Cañado2010) as part of their telecollaboration efforts to enhance vocabulary instruction. Their Spanish participants practiced vocabulary items with their Dallas tutors from the USA through telecollaboration – the first time that sitcoms were used for vocabulary teaching through telecollaboration.

Figure 2 The frequency distribution of the tools used in the studies

3.1.2 Study contexts, countries, and participants

The studies reported exchanges between participants from at least two different country contexts; two exceptions also involved offline contexts. Dooly (Reference *Dooly2011) conducted her study in a blended learning environment and considered offline context as well in order to examine divergences between task plans and participant actions. Canto, Jauregi and van den Bergh (Reference *Canto, Jauregi and van den Bergh2013) included an experimental group that explored intercultural aspects only in a traditional classroom environment, and the researchers compared this group with an online interaction group whereby Dutch learners of Spanish had the opportunity to communicate with native speakers of the target language.

Regarding the country contexts, Spain–USA exchanges (n = 6) formed over a third of all intercultural exchanges, followed by China–USA (n = 2) and Germany–USA (n = 2) exchanges. Figure 3 illustrates the country contexts of the exchanges and displays how many times these country contexts were involved in telecollaboration. The USA emerges as the most popular country choice for telecollaboration, then Spain and Germany in terms of frequency of participation. Prioritizing these country contexts could be indicative of the language concern in telecollaboration, as most studies involve the speakers of widely spoken and taught languages.

Figure 3 The frequency distribution of participants’ country contexts

The studies foregrounded various profiles from different cultural and country backgrounds. These included in-service teachers (Angelova & Zhao, Reference *Angelova and Zhao2016 [2014]; Bueno-Alastuey & Kleban, Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]), seventh grade learners (Chen & Yang, Reference *Chen and Yang2016 [2014]), middle school, secondary-, and post-secondary-level students (Vinagre & Muñoz, Reference *Vinagre and Muñoz2011; Ware, Reference *Ware2013; Ware & Kessler, Reference *Ware and Kessler2016 [2014]), and high school (Schenker, Reference *Schenker2012) and primary school students (Dooly, Reference *Dooly2011). Language and intercultural learning was the focal point in these studies, but the focus was usually on different micro/macro features of intercultural or language learning as explained in the next subtheme.

3.1.3 Focal points of the studies in terms of telecollaborative language and intercultural learning

Although the studies focused overall on language and intercultural learning, they exhibited varied interests in terms of their aims in designing and implementing their telecollaborative tasks. Various aims were to provide peer feedback, corrective feedback, and error correction (Lee, Reference *Lee2011; Lee & Markey, Reference *Lee and Markey2014; Vinagre & Muñoz, Reference *Vinagre and Muñoz2011), to tutor language learners (Angelova & Zhao, Reference *Angelova and Zhao2016 [2014]), to improve techno-pedagogical skills (Bueno-Alastuey & Kleban, Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]), to analyze interaction patterns (Ware, Reference *Ware2013; Ware & Kessler, Reference *Ware and Kessler2016 [2014]), to trace openings and closings in computer-mediated communication (CMC) Zhang (Reference *Zhang2014), to scrutinize technical, linguistic, and educational hegemonies (Helm, Guth & Farrah, Reference *Helm, Guth and Farrah2012), to examine contradictions in online collaboration (Antoniadou, Reference *Antoniadou2011), to investigate the processes involved in the design and implementation of a telecollaborative project (Dooly, Reference *Dooly2011), and to analyze linguistic features of the discourse of participants (Liaw & Bunn-Le Master, Reference *Liaw and Bunn-Le Master2010).

3.2 The participants’ overall views on their telecollaborative experiences

The synthesis revealed a prevalence of positive telecollaborative experiences, as reported by the participants, resulting from a lively engagement with speakers of the target languages and people from diverse cultures (Bueno-Alastuey & Kleban, Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]; Chun, Reference *Chun2011; Lee & Markey, Reference *Lee and Markey2014; Liaw & Bunn-Le Master, Reference *Liaw and Bunn-Le Master2010). Some participants noted that the project was an eye-opening one thanks to the complex engagements in network-based activities (Antoniadou, Reference *Antoniadou2011; Helm et al., Reference *Helm, Guth and Farrah2012). Moreover, participants in the study conducted by Pérez Cañado (Reference *Pérez Cañado2010) stated that they would be very willing to participate in another telecollaborative project in the future. Telecollaboration, therefore, played an overall satisfactory role in providing enjoyable intercultural experiences (Angelova & Zhao, Reference *Angelova and Zhao2016 [2014]).

Digital tools such as learning management systems (e.g. Moodle and Blackboard), microblogging (Twitter), blogging, podcasting, videoconferencing, virtual worlds (e.g. Second Life), and chat rooms were also embraced by the participants and reported to be engaging during the exchanges (Antoniadou, Reference *Antoniadou2011; Canto et al., Reference *Canto, Jauregi and van den Bergh2013; Chen & Yang, Reference *Chen and Yang2016 [2014]; Chun, Reference *Chun2011; Lee & Markey, Reference *Lee and Markey2014; Schenker, Reference *Schenker2012). However, there were also some opposing voices regarding the integration of technology. One third of the participants in the study conducted by Chen and Yang (2016 [2014]) found the online tasks stressful and felt nervous even though they appreciated the opportunities for intercultural communication. However, in the same study, prospective language teachers shared their satisfaction at their growing acquaintance with more recent tools such as Second Life, Dropbox, and podcasts since they cultivated greater confidence in their usage in language education. Because of the prevailing satisfaction with telecollaboration, some researchers suggested the integration of telecollaboration into the curriculum of mainstream language teaching programs (Canto et al., Reference *Canto, Jauregi and van den Bergh2013; Ware & Kessler, Reference *Ware and Kessler2016 [2014]). O’Dowd (Reference O’Dowd2011) and Sadler and Dooly (Reference Sadler and Dooly2016) in this regard found supporters for integrating telecollaborative projects into mainstream language (teacher) education.

3.3 Language learning through telecollaboration

The reader of the studies here can sense that expectations are usually high prior to a project in terms of language and intercultural learning. This synthesis confirms that their expectations were met to a certain extent. Chen and Yang (Reference *Chen and Yang2016 [2014]), for example, reported that telecollaboration yielded a strong positive impact on the language learning processes of Taiwanese learners who conducted deep cross-cultural inquiries in collaboration with participants from four different country contexts. In their study, participants reported a sense of achievement and improved self-scaffolding skills, and benefited from less stressful learning opportunities. Furthermore, Schenker (Reference *Schenker2012) and Liaw and Bunn-Le Master (Reference *Liaw and Bunn-Le Master2010) found that intercultural exchanges resulted in a significant growth of overall language skills. As interactions with people from diverse backgrounds could be an efficient way to observe authentic language use and to practice existing intercultural communicative skills, telecollaborative learning helped participants take advantage of the authenticity and improve their oral skills in the target languages (Angelova & Zhao, Reference *Angelova and Zhao2016 [2014]; Canto et al., Reference *Canto, Jauregi and van den Bergh2013; Chen & Yang, Reference *Chen and Yang2016 [2014]). In addition, language learners also had a better understanding of lexicon and grammatical structures of the target languages (Angelova & Zhao, Reference *Angelova and Zhao2016 [2014]; Lee, Reference *Lee2011; Pérez Cañado, Reference *Pérez Cañado2010).

The interactions with native speakers represented added value in language classrooms compared to the traditional language instruction, as the learners had more opportunities to practice and indirectly develop greater confidence and motivation in their speaking skills (Canto et al., Reference *Canto, Jauregi and van den Bergh2013; Pérez Cañado, Reference *Pérez Cañado2010). Zhang (2014) supported the idea that telecollaboration offered an authentic way of both learning and practicing second/foreign languages. In her study, participants were able to acquire openings and closings in Chinese through online interactions with Chinese pre-service language teachers. They used similar openings and closings to real conservations, with Zhang (2014) thus arguing that these online learning gains were highly likely to be transferred to real-life communication contexts.

Some other researchers realized that online intercultural projects also have potential in giving feedback to language learners. At the same time, prospective teachers may have a chance to practice their skills in tutoring or particularly in feedback delivery. Lee (Reference *Lee2011) highlighted a worthwhile role of telecollaboration in the improvements of language form through peer feedback in particular. Vinagre and Muñoz (Reference *Vinagre and Muñoz2011: 82), who also explored the impact of peer feedback on the improvement of learner accuracy, voiced concerns about the prevalence of telecollaborative exchanges that had only focused on fluency development; they therefore placed more emphasis on language accuracy in their study and enabled the participants to use “different strategies and correction techniques to foster attention to linguistic form”.

On the other hand, language learners should not only be seen as language learners since they exhibit multiple identities (Norton, Reference Norton2000). Taking identity and hegemony issues into account, Helm et al. (Reference *Helm, Guth and Farrah2012) conducted telecollaborative exchanges between Palestinian and Italian students and found that micro, meso, and macro contexts of their participants had an impact on the quality and effectiveness of online exchanges; they thus foregrounded a relatively new insight into telecollaborative projects thanks to their efforts in observing possible hegemonies between communities from different country contexts. Lastly, although different proficiency levels and power issues among participants were regarded as a challenge at first (Bueno-Alastuey & Kleban, Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]), it was possible to overcome them through effective guidance (Helm et al., Reference *Helm, Guth and Farrah2012).

3.4 Intercultural learning through telecollaboration

Alongside improvements in language skills, one of the major aims of the telecollaborative learning was to promote ICC. By stimulating people to reflect on different worldviews (Bennett, Reference Bennett1993; Byram, Reference Byram1997), telecollaboration helped them to grow interculturally (Liaw & Bunn-Le Master, Reference *Liaw and Bunn-Le Master2010). Among other things, they increased their knowledge (Lee & Markey, Reference *Lee and Markey2014; Schenker, Reference *Schenker2012), interest (Liaw & Bunn-Le Master, Reference *Liaw and Bunn-Le Master2010), curiosity (Chen & Yang, Reference *Chen and Yang2016 [2014]), and awareness (Angelova & Zhao, Reference *Angelova and Zhao2016 [2014]; Chen & Yang, Reference *Chen and Yang2016 [2014]) toward both their own background and other cultural perspectives. Byram’s (Reference Byram1997) ICC model was by far the most widely adopted framework for the studies reviewed here. This model offers different levels of intercultural competence that stretches beyond basic fact-based intercultural information exchange. Liaw and Bunn-Le Master (Reference *Liaw and Bunn-Le Master2010) identified a shift from exchanging facts to sharing personal views on the assigned topics. Furthermore, those studies deploying ICC in the interpretation of data evidenced different levels of ICC that can be observed, for example, in Schenker’s (Reference *Schenker2012) study where English and German learners demonstrated four different levels of ICC. Chen and Yang (Reference *Chen and Yang2016 [2014]) similarly signaled an ambivalent developmental process of ICC among their participants. Telecollaborative studies, in a sense, helped participants improve their ICC to different extents, and such efforts may thus help participants reach the more sophisticated, critical, and complex levels of ICC in the long run with longer intercultural online exchanges. From the perspective that underscores complexity and variation, a need for further longitudinal and qualitative studies emerged in order to track the complex, individual, and developmental processes involved in ICC development within online intercultural environments (Çiftçi, Reference Çiftçi2016).

As telecollaborative exchanges enabled people to develop their ICC on different levels, some studies were interested in the quality of exchanges and in the analysis of ongoing processes involved in the intercultural exchanges and communication. Some studies found that the majority of the exchanges were fact based (Angelova & Zhao, Reference *Angelova and Zhao2016 [2014]; Liaw & Bunn-Le Master, Reference *Liaw and Bunn-Le Master2010). To a large extent, the flow of the exchanges was first grounded on the stereotypical and information-seeking questions and then tended to include information sharing (Chen & Yang, Reference *Chen and Yang2016 [2014]; Liaw & Bunn-Le Master, Reference *Liaw and Bunn-Le Master2010; Ware & Kessler, Reference *Ware and Kessler2016 [2014]), although most questions were still based on information seeking rather than critical interpretation (Ware & Kessler, Reference *Ware and Kessler2016 [2014]). For further stages of the exchanges, however, participants generally elaborated on the issues that emerged during the previous stages, and some of them started to challenge existing stereotypes through mutual negotiations or started to shake the possible hegemonies or power relations (Chen & Yang, Reference *Chen and Yang2016 [2014]; Helm et al., Reference *Helm, Guth and Farrah2012; Liaw & Bunn-Le Master, Reference *Liaw and Bunn-Le Master2010).

Some participants tried to be polite and refrained from conflict and challenging different viewpoints (Angelova & Zhao, Reference *Angelova and Zhao2016 [2014]; Liaw & Bunn-Le Master, Reference *Liaw and Bunn-Le Master2010). However, Helm et al. (Reference *Helm, Guth and Farrah2012) regarded conflicts among participants as an opportunity for increased motivation, thereby triggering transformational processes. The same researchers supported the idea of taking learners out of their comfort zones as an optimal condition for increased intercultural awareness, thereby helping them to develop ethnorelative perspectives. A facilitator or a competent “telecollaborative teacher” (O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2015a) can indeed help learners to become involved in constructive dialogues, or can create stimulating environments for learners to maximize and optimize the affordances of intercultural environments whereby they can argue over different viewpoints non-judgmentally (Çiftçi, Reference Çiftçi2016). However, such teachers should always remember that the reasons for superficial exchanges may not be detected easily (O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2015b) due to the complex, contextualized nature of interactions, because online communication differs from face-to-face interactions both in conceptual and practical terms (Ware, Reference *Ware2013). Another caveat pointed out by Chun (Reference *Chun2011) is that asynchronous and synchronous tools had different results: Asynchronous tools provided opportunities for more complex statements, whereas synchronous tools were more appropriate for short and less formal statements. Therefore, a rigorous design that is informed by contextual features should be considered before combining digital tools in telecollaborative language and intercultural learning (Çiftçi, Reference Çiftçi2016).

Although most participants showed significant improvements in different aspects of language and intercultural learning, there were still some instances of “failed communication” (O’Dowd & Ritter, Reference O’Dowd and Ritter2006) between partners or groups from different countries. Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban (Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]), for example, reported that their Polish students thought their Spanish partners lacked motivation. Additionally, Ware (Reference *Ware2013) found that a lack of stimulating context and key interactional features such as topic development, asking questions, and risk-taking turned some exchanges into a failure. However, some characteristics of successful communication were also patterned by Ware and Kessler (Reference *Ware and Kessler2016 [2014]), who pointed out that successful intercultural communicators put greater effort into the depth and context of the exchanges and moved from information-seeking questions to contextualized topics, whereas unsuccessful communicators tended to ask questions that were out of context and lacking in depth.

Lastly, a knowledge repertoire as to the glocal (local + global) contexts of participants can be helpful to understand the nature of the communication between different groups. Helm et al. (Reference *Helm, Guth and Farrah2012) examined the dynamics of the different local and global contexts with a deep exploration of micro, meso, and macro levels, and were able to describe and interpret intricacies of the interactions, and even to discuss possible hegemonies between different cultural communities. Further explorations of identity, power, and hegemony issues in online intercultural exchanges may indeed provide deeper insights with respect to language and intercultural learning from sociocultural perspectives.

3.5 The challenges experienced within the telecollaborative projects

Telecollaborative projects overall succeeded in fostering existing intercultural and language skills even though there were some drawbacks, such as failed communication and fact-based exchanges. Further, the studies did not claim that everything was perfect and recognized a number of problems or challenges. The most salient challenge was the need to set different goals and objectives for each side due to different contextual features and academic backgrounds (Angelova & Zhao, Reference *Angelova and Zhao2016 [2014]; Antoniadou, Reference *Antoniadou2011; Bueno-Alastuey & Kleban, Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]). Therefore, some researchers preferred to analyze data from one side only (Chen & Yang, Reference *Chen and Yang2016 [2014]; Dooly, Reference *Dooly2011; Ware & Kessler, Reference *Ware and Kessler2016 [2014]).

Another example can be found in Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban’s (Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]) study, where the Polish student teachers aimed to improve their pedagogical knowledge of CMC, whereas their Spanish partners targeted language improvements (Bueno-Alastuey & Kleban, Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]). Although both sides were positive about their intercultural experiences, the Polish participants reported limited learning due to differences in language proficiency levels. Nevertheless, these same participants reported that the project contributed to their ICC while the Spanish students viewed the experience as helpful for their language skills. Antoniadou (Reference *Antoniadou2011) in particular acknowledged the existence of contradictions during the implementation of her project, necessitating the reorganization of activity systems and the adoption of new solutions as these emerged. In her study, participants either abandoned a tool that they had difficulty in managing or found an alternative one to maintain the communication. These examples demonstrated that not everything follows the pre-established plans; therefore, implementers should always be prepared for emerging contradictions and for generating new solutions/strategies.

Other challenges or difficulties can briefly be listed as lack of participation (Bueno-Alastuey & Kleban, Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]; Ware & Kessler, Reference *Ware and Kessler2016 [2014]), lack of collaboration (Bueno-Alastuey & Kleban, Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]), scheduling problems (Bueno-Alastuey & Kleban, Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]; Chun, Reference *Chun2011; Ware & Kessler, Reference *Ware and Kessler2016 [2014]), time zone differences (Lee & Markey, Reference *Lee and Markey2014), challenges of technological tools (Antoniadou, Reference *Antoniadou2011; Ware & Kessler, Reference *Ware and Kessler2016 [2014]), and challenges of assessment (Schenker, Reference *Schenker2012; Ware & Kessler, Reference *Ware and Kessler2016 [2014]). The studies overall grappled with difficulties related to different objectives, technical issues, communication, and collaboration.

3.6 The needs for further effective telecollaboration

As discussed in the previous section, telecollaboration has its own challenges. The telecollaborative learning experiences thus revealed a certain number of needs for further practices and research in order not to repeat similar mistakes. First, ensuring effective participation was one of the major issues. In order to handle this challenge, studies had their own suggestions for further endeavors. They strongly suggested creating a safe and stimulating collaborative environment under the guidance of competent facilitators (Angelova & Zhao, Reference *Angelova and Zhao2016 [2014]; Helm et al., Reference *Helm, Guth and Farrah2012). Ware and Kessler (Reference *Ware and Kessler2016 [2014]) even noted that the teacher’s role increased rather than diminished in the case of technology integration. According to Pérez Cañado (Reference *Pérez Cañado2010), an instructor who conducts a telecollaborative project should be monitoring, prompting, guiding, and communicating. Moreover, Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban (Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]) suggested including reflective sessions under the guidance of telecollaborative teachers who would have a closer eye on the progress and learning processes. Such teachers can also scaffold learners to go beyond their existing levels of intercultural understanding and language use, thereby stimulating their higher order thinking and research skills (Chen & Yang, Reference *Chen and Yang2016 [2014]). If the facilitators lack experience in telecollaboration, they can be trained by experienced people in the field (Helm et al., Reference *Helm, Guth and Farrah2012).

Participant training is another crucial issue, as participants are the ones who are expected to take control over their own learning processes and participate actively (Dooly, Reference *Dooly2011; Pérez Cañado, Reference *Pérez Cañado2010). Since technical issues were listed as a barrier for some participants, careful training in how to use digital tools was seen as another imperative (Chun, Reference *Chun2011; Lee & Markey, Reference *Lee and Markey2014). The participants themselves, however, may look for new solutions to their technical problems during telecollaboration; therefore, a number of observation plans and alternative solutions or strategies to anticipated problems could be generated prior to or during an exchange (Antoniadou, Reference *Antoniadou2011; Dooly, Reference *Dooly2011). Ensuring high motivation for active participation was another critical issue: Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban (Reference *Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban2016 [2014]) suggested assessing and grading students’ efforts in order to increase the likelihood of active participation. Similarly, Antoniadou (Reference *Antoniadou2011) and Pérez Cañado (Reference *Pérez Cañado2010) acknowledged the idea of providing extra credits to those who participated in an exchange. As a final caveat for further studies, Helm et al. (Reference *Helm, Guth and Farrah2012) viewed a balanced distribution and matching the participants from different backgrounds as key factors for an effective telecollaboration.

4 Concluding remarks

This synthesis study revealed a number of critical issues for further research and practice in telecollaborative intercultural and language learning. First, the studies tended to favor certain Western contexts and participant profiles. However, the literature revealed a prevailing satisfaction with telecollaborative intercultural and language learning. These studies indicated that participants showed – to varying degrees – developments in terms of both language and intercultural competencies. Even though the projects were helpful for the participants’ language and intercultural growth, they were confronted with a few substantial challenges. As telecollaboration involves people from diverse backgrounds, establishing a common ground and shared goal can be difficult to achieve. Facilitators may also not be able to solve all the emerging socio-institutional and communication problems and may have trouble in guiding the participants for an effective intercultural collaboration/communication that involves ICC and intercultural pragmatic competence (Lewis & O’Dowd, Reference Lewis and O’Dowd2016). Such accumulated challenges and experiences, therefore, highlighted a number of needs for future practices and research in telecollaboration. In the next and final section of the paper, recommendations for further research and practice are offered in light of the main findings. Figure 4 provides a visualization of the key findings with the help of the interpretive guidance of this qualitative meta-synthesis.

Figure 4 Overall representation of the key findings

4.1 Recommendations for further research and practice

This synthesis study makes a number of recommendations for researchers and practitioners who plan to benefit from telecollaborative projects in respect to intercultural and language learning. First, implementers need to consider the challenges and major necessities that are given in Figure 4. In order to minimize technical problems and to optimize intercultural communication, participants and teachers need prior training, in particular to develop their ICC and intercultural pragmatic competence sufficiently before engaging in an online exchange (Lewis & O’Dowd, Reference Lewis and O’Dowd2016). The technical and communicational aspects are thus crucial to bear in mind before any project is conducted. Implementers should also consider such technical and institutional challenges as differences in terms of time zones, academic calendar, and course requirements between participating institutions.

Preparing participants or teachers through traditional training sessions, however, may not guarantee effective intercultural communication between parties, as “teachers learn by being actively engaged in educational activity, forming part of communities of practice and having opportunities to reflect and theorize based on their own learning (Johnson, 2006, 2009; Wright, 2010)” (O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2015b: 65). Therefore, both teachers and learners should be provided with longitudinal, ongoing, and experiential reflective opportunities so that they can build their own first-hand repertoire of online intercultural exchanges and grow accordingly. In addition, meticulously contextualized online intercultural exchanges and careful task designs can foster engagement in rich interactions around certain topics or tasks (Lewis & O’Dowd, Reference Lewis and O’Dowd2016). A variety of digital tools such as videoconferencing technologies can be considered for further telecollaboration experiences (Lewis & O’Dowd, Reference Lewis and O’Dowd2016; O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2016) in parallel with the unique characteristics of the participating subjects and contexts. However, interculturally competent facilitators/guides should always be available – and indeed should intervene periodically – during every stage of telecollaboration for meaningful language and intercultural growth. These telecollaborative teachers should be competent in interculturality and be cognizant of theoretical backgrounds to intercultural communication and language acquisition as well as having organizational and pedagogical competences (O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2015a).

Another observable pattern in the literature was the dominance of interactions between Western country contexts, with just a small number of other instances. For future practices, further exchanges between different country and cultural contexts with different languages may bring another layer of depth and complexity to the literature. In particular, interactions between communities that are mutually stereotyped due to macrocontextual features such as economy and politics may yield intense intercultural discussions, which may pave the way for thought-provoking and innovative approaches to intercultural and language learning. For those who aim to establish new or further partnerships and need resources to set up telecollaborative exchanges, the UNICollaboration platform (https://uni-collaboration.eu) offers an optimum starting point.

Some further creative analyses and different perspectives can also be helpful in offering rich descriptions of the language and intercultural learning experiences. For example, Helm et al. (Reference *Helm, Guth and Farrah2012), in an effort to foreground macrocontextual features such as larger societal, political, and economic factors, underscored the critical role of power relations in telecollaborative exchanges. Such “critical” telecollaborative approaches may help future researchers and practitioners “unfollow” the shallow, essentialist approaches to culture or to intercultural exchanges (Holliday, Reference Holliday2011), since “impressions of intercultural competence are always contextually contingent and situated in macro structures; historically influenced and framed by global, political, economic systems, and ideologies such as neoliberalism” (Collier, Reference Collier2015: 10). Speaking of intercultural competence, a comprehensive or sound intercultural competence model that is specifically devised for online intercultural exchange remains to be defined (Lewis & O’Dowd, Reference Lewis and O’Dowd2016) because such virtual environments may not correspond conceptually and practically to the conventional models (Dooly, Reference *Dooly2011). Such different perspectives indeed indicate how telecollaborative exchanges are open to different research directions with a variety of complex and dynamic issues. Further research in different directions involving intercultural and language learning are thus essential in order to understand fully what specific contributions telecollaboration can make and how it can find a more visible place in mainstream foreign language education as a relatively new but already established approach (Lewis & O’Dowd, Reference Lewis and O’Dowd2016; O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2011).

The last recommendation acknowledges the main limitations of this synthesis paper and concerns potential future meta-synthesis or meta-analysis. The study at hand had a limited scope and time period, although it provided an overview of the relatively recent findings and accordingly interpreted emerging issues and observable patterns in such a rapidly evolving field that has a history of almost 25 years (Lewis & O’Dowd, Reference Lewis and O’Dowd2016). With larger research teams that may have an interest in the past, present, and future of telecollaboration, further efforts can either take a longitudinal perspective to capture the major trends in telecollaboration since its early days, or can concentrate on a particular research area in telecollaborative learning (e.g. ICC components, linguistic competence, digital literacy, or learner autonomy), again from the very beginning of telecollaboration to the current date. By doing so, such review studies can enable us to see the full extent of prevalent patterns within broader historical perspectives.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Editor, Professor Alex Boulton, and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions for this manuscript.

Appendix A

Analysis Table

Appendix B

A Coding Sample for Major Findings in the Literature: Angelova & Zhao (Reference *Angelova and Zhao2016 [2014])

About the authors

Emrullah Yasin Çiftçi is a research assistant at the Middle East Technical University, Turkey, where he is also working on a PhD in the English Language Teaching program. His research interests include language teacher education, international education, intercultural communication, and intercultural (communicative) competence.

Perihan Savaş is an associate professor at the Middle East Technical University, Turkey. She received her PhD in Curriculum and Instruction with a major in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) from the University of Florida. Her scholarly interests include integrating technology into English as a foreign language (EFL) curricula, mobile-assisted language learning (MALL), teacher training/faculty support in online education, and computer-mediated communication (CMC).