1 Introduction

Corrective feedback (CF) refers to the practice whereby a teacher or peer provides formal or informal feedback to learners on performance that contains linguistic error. CF has increasingly received scholarly attention over the past two decades (Bitchener & Ferris, Reference Bitchener and Ferris2012; Bitchener & Storch, Reference Bitchener and Storch2016; Mackey, Reference Mackey2012). Previous research on CF has focused on (a) the typology of CF types (Ellis, Reference Ellis2009); (b) whether CF facilitates or impedes second language (L2) development (Li, Reference Li2010; Lyster & Ranta, Reference Lyster and Ranta1997; Russell & Spada, Reference Russell and Spada2006; Truscott, Reference Truscott1996, Reference Truscott2007), (c) whether explicit CF is more effective than implicit CF (Bitchener, Reference Bitchener2008; Bitchener & Knoch, Reference Bitchener and Knoch2010a; Ferris, Reference Ferris2006; Ferris & Roberts, Reference Ferris and Roberts2001; Sheen, Reference Sheen2007), (d) whether CF is more effective when it is focused (targeting a few structures at a time) or unfocused (comprehensive) (Bitchener & Knoch, Reference Bitchener and Knoch2010b; Ellis, Sheen, Murakami & Takashima, Reference Ellis, Sheen, Murakami and Takashima2008; Ferris, Reference Ferris1997), and (e) learners’ attitudes toward and perceptions of CF (Cornillie, Clarebout & Desmet, Reference Cornillie, Clarebout and Desmet2012). This body of research has accumulatively contributed to our overall understanding of the mechanisms of CF in facilitating language learning.

However, the CF used in previous studies tends to be static and stationary; that is, it generally does not change in terms of explicitness or specificity as a function of a learner’s response to the feedback. The type and extent of CF needed by a learner, as suggested by Vygotsky (Reference Vygotsky1978), sheds important light on whether a learner is developing his or her abilities in a particular area and the ways they do it. Aljaafreh and Lantolf (Reference Aljaafreh and Lantolf1994) showed that CF, provided in a graduated fashion—i.e., from more implicit (asking learners to read an erroneous sentence) to more explicit (providing learners with metalinguistic explanations)—can promote L2 learning in a dialogically and collaboratively constructed zone of proximal development (ZPD).

Guided by the same theoretical framework, Poehner and colleagues have developed a web-based formative assessment tool called Computerized Dynamic Assessment (C-DA) to evaluate learners’ language proficiency in French, Russian, and Chinese (Poehner & Lantolf, Reference Poehner and Lantolf2013; Poehner, Zhang, & Lu, Reference Poehner, Zhang and Lu2015). The C-DA system documents how many test questions learners answer correctly and how many incorrectly on the first try, as well as tracking how much CF they need in order to complete the assessment task. By offering graduated CF, the C-DA system is able to gauge test-takers’ listening and reading comprehension abilities in a more fine-grained way than is possible with traditional tests. This research project has highlighted the usefulness of dynamically adjusting the explicitness of CF depending on a learner’s response to it.

The present study continues this line of research and explores how graduated CF can be implemented in an intelligent computer-assisted language learning (ICALL) environment. Technology-mediated CF, as Sauro (Reference Sauro2009) noted, holds great promise for the learning of especially complex or low-salient forms. Given marked advances in computational linguistics, ICALL has become a promising avenue for exploring the effects of graduated CF in language learning. Yet scholars have not addressed the implementation and efficacy of graduated CF in an ICALL environment, despite extensive and valuable research on ICALL’s potential for facilitating language learning. The C-DA project, which uses multiple-choice questions, has primarily focused on language recognition and comprehension so far. In the present study, we implemented graduated CF in a socioculturally informed ICALL environment in order to assess learners’ language production through the use of a more open-ended translation task. We explore the effectiveness of graduated CF in helping American learners learn the Chinese ba-construction, an important aspect of the Chinese language that invariably proves challenging to L2 speakers (Jin, Reference Jin1992; Wen, Reference Wen2012).

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 CF in second language acquisition

A central question pertaining to the value of CF in the context of second language acquisition centers on whether CF benefits language learning at all, and if, in fact, it does, then in what ways. Truscott (Reference Truscott1996, Reference Truscott2007) has argued that CF does not benefit language learning and advocated for its total abandonment in instructional contexts. Using a combination of qualitative analysis and quantitative meta-analysis, Truscott (Reference Truscott2007: 255) has claimed with 95% confidence that CF has a “very small” actual benefit, if any, in regard to having a positive impact on learners’ ability to write accurately. Such small effect of CF has also been reported by Kepner (Reference Kepner1991) and Polio, Fleck, and Leder (Reference Polio, Fleck and Leder1998). For example, Polio et al. (Reference Polio, Fleck and Leder1998) examined 64 English as a second language (ESL) students’ writings over seven weeks and found that differences in posttest score for the treatment and control group were not significant. However, it needs to be pointed out that this may be due to the difference in instruments between pretest and posttest (journal entry vs. in-class essay). In response, other researchers have amassed a large volume of empirical evidence showing that CF benefits learners both in the short term and in the long term (Li, Reference Li2010; Lyster & Ranta, Reference Lyster and Ranta1997; Russell & Spada, Reference Russell and Spada2006). CF helps learners notice (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1990) mismatches between their own language production and target-like forms.

Researchers have found that CF can be particularly effective when it targets specific error types as compared to providing comprehensive CF to all errors (Bitchener & Knoch, Reference Bitchener and Knoch2010a, Reference Bitchener and Knoch2010b; Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Sheen, Murakami and Takashima2008; Ferris, Reference Ferris1997; Han, Reference Han2002). Certain approaches to CF have been found to be conducive for pushed output, as evidenced in learners’ self- or other-repair (Lyster & Ranta, Reference Lyster and Ranta1997; Panova & Lyster, Reference Panova and Lyster2002) as well as accuracy in repair (Nassaji, Reference Nassaji2007). Used as a pedagogical tool, CF has been found to be valuable in increasing learners’ accuracy in L2 writing (Ferris, Reference Ferris1999, Reference Ferris2006; Bitchener & Ferris, Reference Bitchener and Ferris2012). There is a general consensus among SLA researchers that CF makes errors more salient and explicit and that it is especially useful for helping adult learners avoid fossilization and continue developing their target language competence.

Different types of CF may generate different types of responses, which may, in turn, produce different levels of processing. Explicit CF (e.g., metalinguistic explanation) can be effective in promoting acquisition of specific grammatical features and may be more valuable for L2 learners than unlabeled CF (Bitchener, Reference Bitchener2008; Bitchener & Knoch, Reference Bitchener and Knoch2010a; Bitchener, Young, & Cameron, Reference Bitchener, Young and Cameron2005; Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Sheen, Murakami and Takashima2008; Ferris, Reference Ferris2006; Ferris & Roberts, Reference Ferris and Roberts2001; Sheen, Reference Sheen2007). This may be due to L2 learners receiving extensive formal grammar instruction and explicit CF may elicit their prior knowledge. However, explicit CF has a disadvantage in that it requires minimal processing on the part of the learner, and thus, considered not as beneficial for long-term learning (Ellis, Reference Ellis2009). By contrast, implicit (or indirect) CF requires more work on the part of the learner than explicit CF does and is, therefore, thought to facilitate long-term language learning (Ferris & Roberts, Reference Ferris and Roberts2001). Finally, scholars have emphasized the importance of considering individual student responses to CF in addition to cross-group comparisons (Bitchener & Ferris, Reference Bitchener and Ferris2012; Ferris, Reference Ferris2006, Reference Ferris2010; Ferris, Liu, Sinha, & Senna, Reference Ferris, Liu, Sinha and Senna2013; Hyland & Hyland, Reference Hyland and Hyland2006). While individual differences may serve as a “useful direction for future second language writing research” (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2010: 167), few studies have attempted to individualize CF for different student writers.

2.2 Sociocultural theory-informed CF

CF has been studied through a diverse range of theoretical lenses. The guiding principles underlying the design of an ICALL system for Chinese, the focal language in the present study, were drawn from Vygotskian sociocultural theory (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978). A fundamental tenet of sociocultural theory is that the human mind is mediated by culturally constructed artifacts, the most pervasive of which is language, considered the most powerful auxiliary means for intentionally controlling and reorganizing social life and psychological processing (Lantolf & Thorne, Reference Lantolf and Thorne2006). A key theoretical construct in sociocultural theory is mediation, which refers to the use of material and symbolic tools or signs in regulating, including influencing and changing, our relationships with others and with ourselves. Of particular interest to the present study is the extent to which graduated mediation can be implemented in an ICALL environment in order to promote L2 development.

One of the best-known theoretical constructs in sociocultural theory, also relevant to the discussion of CF, is ZPD, which refers to “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978: 86). To put it another way, what a person can do today with corrective feedback from others is what he or she will be able to do independently tomorrow, because feedback from others triggers the internalization process by which one’s ability to control the mind is enhanced (Lantolf, Reference Lantolf2000). As such, the ZPD construct not only evaluates a learner’s past performance, but also predicts the learner’s potential. For Vygotsky (Reference Vygotsky1978), learning and development are not the same: the developmental process does not coincide with—but lags behind—the learning process. The difference between the two is what constitutes a learner’s ZPD at any given time. The essential characteristic of learning is that it creates the ZPD. Intentionally designed learning instructions organized to be sensitive to a learner’s ZPD are highly effective in stimulating qualitative mental development and can lead, therefore, to qualitative changes in development. The present study explores how ZPD can be created between the ICALL system and the learner by developing computer algorithms that provide graduated CF that, in turn, creates language learning opportunities.

The transformation of learners’ abilities in the ZPD through dialogic collaboration between the learner and his or her mediator constitutes much work behind the pedagogical approach known as Dynamic Assessment (Lantolf & Poehner, Reference Lantolf and Poehner2004; Poehner, Reference Poehner2008, Reference Poehner2011). Through providing appropriate mediation (i.e., CF) to both understand and to intervene in development, Dynamic Assessment dialogically linked assessment and instruction as a single activity. Studies employing the Dynamic Assessment approach have examined microgenetic growth both in a range of learning contexts, including traditional classroom-based environments (Lantolf & Poehner, Reference Lantolf and Poehner2011; Poehner & Ableeva, Reference Poehner and Ableeva2011), and computer-based learning environments (Poehner & Lantolf, Reference Poehner and Lantolf2013; Poehner, Zhang, & Lu, Reference Poehner, Zhang and Lu2015).

Of particular interest to L2 development is ontogenetic (longitudinal) analysis and microgenetic analysis. The former focuses on developmental processes over a person’s lifetime, whereas the latter focuses on developmental processes that occur in a relatively short period of time. The microgenetic approach has been used by SLA researchers to document L2 growth in various contexts. Through detailed transcription of oral interactions, Ohta (Reference Ohta2000) has documented two university-level L2 Japanese learners’ microgenetic developmental processing of the Japanese desiderative construction in a translation task. By using a range of verbal cues (vowel elongation, filled pauses, intonation contours), the learners provided and responded to developmentally appropriate CF that facilitated learning and internalization of this grammatical feature. Particularly relevant to the present study is the ICALL system’s ability, through the use of relational database technology, to track a learner’s microgenetic changes as he/she works through iterations of graduated CF in an effort to complete an English–Chinese translation task.

2.3 Feedback in ICALL

Intelligent computer-assisted language learning (ICALL) has benefited from an evolving theoretical understanding of SLA processes and from rapid advances in computational linguistics and NLP technologies (e.g., lemmatization, part-of-speech annotation, syntactic parsing). Typically, ICALL systems can automatically enhance textual input, analyze a learner’s language production, and provide immediate and individualized CF (Dickinson, Eom, Kang, Leeb, Sachs, Lee Reference Dickinson, Eom, Kang, Leeb, Sachs and Lee2008; Heift, Reference Heift2002, Reference Heift2004, Reference Heift2010a; Heift & Schulze, Reference Heift and Schulze2007; Schulze, Reference Schulze2008). To date, a number of ICALL systems have been created, including E-Tutor for German (Heift, Reference Heift2010a, Reference Heift2010b), TAGARELA for Portuguese (Amaral, Meurers, & Ziai, Reference Amaral, Meurers and Ziai2011), ROBO-SENSEI for Japanese (Nagata, Reference Nagata2009), and WERTi for English (Meurers et al., Reference Meurers, Ziai, Amaral, Boyd, Mimitrov, Metcalf and Ott2010). E-Tutor provides individualized interactions between the learner and the computer system by emulating a learner–teacher interaction. Through the use of an error-checking system, E-Tutor provides CF to the learner “one error at a time” (Heift, Reference Heift2010b: 448). In this way, the system tracks a learner’s performance history on specific activities. Similarly, TAGARELA uses a learner and a teacher model to select the best feedback strategy to use with each learner based on the level of the activity, the type of task, the characteristics of the errors, and the learner’s profile (Amaral et al., Reference Amaral, Meurers and Ziai2011). By comparison, while WERTi does not provide individualized CF to learners, it offers various types of supplementary language-learning activities (e.g., colorize, click, and practice) and supports the practice of a wide range of grammatical forms and functions (e.g., articles, gerunds/infinitives, phrasal verbs).

While CALL researchers have examined the Vygotskian perspective on technology-rich language learning environments (e.g., Blin, Reference Blin2004), the theoretical frameworks guiding the development of E-Tutor, TAGARELA and WERTi are not related to Vygotskian sociocultural theory, at least not explicitly. However, they have in various ways inspired the development of the Chinese ICALL system reported in this study (e.g., textual enhancement, tracking functions). In contrast to the C-DA project, which uses multiple-choice questions, we explore a more open-ended question format to study how graduated CF can help learners to learn the Chinese ba-construction. In this article, we consider two research questions: What effect, if any, does graduated CF in an ICALL environment have on language learning? What are the participants’ perceptions of this type of CF? Next, we briefly describe the design of the Chinese ICALL system (core algorithms, tracking capabilities, and system architecture), participants and context, and data collection methods and data analysis.

3 Method

3.1 Participants and context

This study is part of a larger research project that examines whether and how a concept-based approach to language instruction can promote L2 development in regard to the acquisition of the Chinese ba-construction (Ai, Reference Ai2015). As the full study from which this paper is drawn is quite extensive in the scope of its findings, we limit the analysis here to some of the data that illustrate how graduated CF is implemented in an ICALL environment and how CF promotes language learning in this environment. This study involved six participants enrolled in a one-on-one eight-week enrichment program with the researcher (tutor) to learn the Chinese ba-construction. The participants were college students taking third-semester Chinese courses at a large public university in the US (see Table 1). Students at this level had the prerequisite vocabulary and grammatical knowledge (e.g., resultative verb compound) necessary to learn the Chinese ba-construction. This study reports the results of the ICALL session of the enrichment program in which the participants spent 30–45 minutes completing an English–Chinese translation task that required them to negotiate various syntactic components of the ba-construction.

Table 1 Participant information

Note. Pseudonyms are used in place of the participants’ names.

3.2 Designing a Chinese ICALL system

In this study, we developed a socioculturally informed ICALL system that assesses learners’ language production through the use of a relatively open-ended translation task. Figure 1 depicts the core algorithm of the Chinese ICALL program. The ICALL system was designed to provide a series of graduated CFs to the participants whereby the CF progresses from implicit and general to explicit and specific. For instance, if a learner does not provide the correct answer on the first try, the system will start with a very implicit CF: “Hmm, can you take a look at it again?” This creates an opportunity for the learner to identify and correct the answer him/herself. If, however, the learner still cannot produce a correct answer, then the system provides CF that is slightly more explicit and specific (e.g., “OK. So can you take a look at the grammatical object of the verb phrase?”). The system compares the learner’s answer to a set of pre-constructed acceptable ones. In the event that the answer provided by the learner does not match any of the pre-defined answers, the ICALL system then subjects the answer to a series of NLP processes (e.g., Chinese-word segmentation, syntactic parsing) in order to determine the location and nature of the problematic areas and provide relevant CF based on the result of the analysis.

Fig. 1 Core algorithm of the Chinese ICALL program

Aljaafreh and Lantolf (Reference Aljaafreh and Lantolf1994) have proposed a 13-level regulatory CF system, ranging from the most implicit to the most explicit. In the C-DA project (Poehner & Lantolf, Reference Poehner and Lantolf2013; Poehner, Zhang, & Lu, Reference Poehner, Zhang and Lu2015), four levels of CF are provided, regardless of the learner’s response. In contrast, the algorithm designed in this study does not have a predetermined number of levels of graduated CF (Figure 1). This is because the CF provided by the ICALL system depends on the type of error the learner makes, which varies across learners. However, when a learner fails to produce a correct answer on the first attempt, the ICALL system always starts with the most implicit CF. The subsequent CF seeks to target aspects of the syntactic elements of the ba-construction, which include (a) the ba-particle, i.e., whether it is correctly present or incorrectly absent, (b) the perfective –le, i.e., whether it is correctly present or incorrectly absent,Footnote 1 (c) the word order, i.e., whether the ba-NP correctly occurs before the ba-VP or incorrectly occurs after it, (d) the grammatical object, i.e., whether the ba-NP is correctly translated, and (e) the verb complement, i.e., whether a verb complement exists and the complement collocates well with the main verb.

The web-based ICALL system was implemented in Python and used the Django Web Framework. The system utilized the Java-based open-source Stanford ParserFootnote 2 to parse the participants’ language production in Chinese, and used TregexFootnote 3 to traverse the parse tree in order to identify important structural arrangements of grammatical elements of the ba-construction. For instance, a well-formed ba-construction stipulates that the ba-NP must occur before the ba-VP. This idea can be expressed in a Tregex pattern: NP>(IP $ BA) & $ (VP<VRD|VP|VV).Footnote 4 This means that an NP must be dominated by an IP that contains the ba-particle and that the NP must be located to the left of a VP in which a VRD, VP, or VV is included.

A crucial aspect of CALL and ICALL design is that of tracking learners’ interactions with the system (Heift, Reference Heift2010a; Heift & Schulze, Reference Heift and Schulze2007; Park & Kinginger, Reference Park and Kinginger2010). Heift (Reference Heift2010a) pointed out that in order for an ICALL system to individualize instruction, it must track each user’s information and share it system-wide. In this study, we used MySQL, an open-source relational database management system, to keep a record of the following information pertaining to the participants’ interactions with the system: Who is answering the question? What is the question being answered? What is the participant’s answer? What is the participant’s confidence level for his or her answer? How long does it take for the participant to provide an answer? What is the IP address of the computer from which the participant provided the answer? Because each user was assigned an independent account, the ICALL system can document in detail the revisions made by each participant to each answer during the ICALL activity.

3.3 Data collection and analysis

The data analyzed in this study were collected from video screen recordings, website logs, audio and video recordings, and post-enrichment program interviews. The participants’ complete interactions with the ICALL system were recorded using video screen recording software called Camtasia. The post-enrichment interviews were conducted, recorded, and transcribed. The tutor was present when the participants performed the tasks. To analyze the data, we first viewed the video and audio recordings in order to identify instances in which the ICALL system identified (or failed to identify) the participants’ problematic areas. We then examined the participants’ interactions with the system as captured by the website’s logging function, which allowed us to reconstruct a moment-by-moment edit made by the participants as they completed the English–Chinese translation task. Finally, we transcribed the semi-structured interview and used a top-down approach to analyze the transcripts of the interview focusing on illustrative episodes where the participants expressed their views on the ICALL system’s pedagogical value, including its occasional break-down, in regard to helping them navigate the various aspects of the ba-construction.

4 Results

4.1 Effectiveness of graduated CF

The analysis of the data shows that overall the graduated CF provided by the ICALL system was effective in identifying the participants’ problems in regard to various syntactic elements of the ba-construction and in providing pertinent and meaningful CF for them to revise their answers. In total, the ICALL system identified 54 errors across the five translation questions by the six participants. Of these, about 15% turned out to be false positives, instances where the ICALL system mistakenly identified the participants’ answer as erroneous but nevertheless were grammatically acceptable. In such situations, the tutor intervened and provided needed CF. In general, however, the graduated CF provided by the ICALL system was effective in helping the participants to identify and correct a number of grammatical issues (e.g., punctuation, grammatical objects, and verb complement) related to the ba-construction. Derrick, for instance, was able to identify and self-correct a punctuation error based on the graduated CF from the ICALL system. Table 2 shows Derrick’s moment-by-moment interaction with the ICALL system on this point.

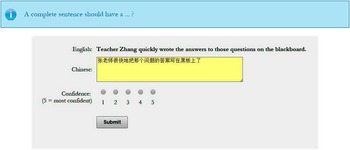

Fig. 2 Example question

Table 2 Moment-by-moment changes via Derrick’s interaction with the ICALL system

Table 3 Moment-by-moment changes via Stacy’s interaction with the ICALL system

Derrick was quite confident Footnote

5

(i.e., level 5) about his initial answer. He said “Okay, I feel good about that” and clicked on the submit button. However, his initial answer was rejected by the ICALL system as incorrect, and Derrick received implicit CF: “Hmm, can you take a look at it again?” Derrick then read his initial answer out loud and immediately removed the adverb

![]() $$\raster="rg1"$$

(“quickly”). At that point, he realized that the English sentence specified “those” questions, so he changed the demonstrative

$$\raster="rg1"$$

(“quickly”). At that point, he realized that the English sentence specified “those” questions, so he changed the demonstrative

![]() $$\raster="rg2"$$

(“that”) to

$$\raster="rg2"$$

(“that”) to

![]() $$\raster="rg3"$$

(“those”), and restored the deleted adverb to its original place. He then selected the highest confidence level and submitted this second answer. Unfortunately, his second attempt was still unsuccessful. Although Derrick had corrected his error in the use of the demonstrative, his error in regard to missing punctuation still remained. In response, the ICALL system provided a second CF that was more explicit than the first: “A complete sentence should have a …?” Derrick thought for a moment, pointed the cursor to the end of his answer and entered a period (i.e.,

$$\raster="rg3"$$

(“those”), and restored the deleted adverb to its original place. He then selected the highest confidence level and submitted this second answer. Unfortunately, his second attempt was still unsuccessful. Although Derrick had corrected his error in the use of the demonstrative, his error in regard to missing punctuation still remained. In response, the ICALL system provided a second CF that was more explicit than the first: “A complete sentence should have a …?” Derrick thought for a moment, pointed the cursor to the end of his answer and entered a period (i.e.,

![]() $$\raster="rg4"$$

in Chinese), and smiled. Choosing again the highest confidence level and saying “Picky, picky,” Derrick submitted his third answer. At this point, the system accepted his answer as correct and displayed— “Congratulations! That’s exactly right!” Derrick smiled and said to himself, “Alright! Third time is the charm!”

$$\raster="rg4"$$

in Chinese), and smiled. Choosing again the highest confidence level and saying “Picky, picky,” Derrick submitted his third answer. At this point, the system accepted his answer as correct and displayed— “Congratulations! That’s exactly right!” Derrick smiled and said to himself, “Alright! Third time is the charm!”

The above brief episode shows that the two rounds of CF provided by the ICALL system helped Derrick to iteratively revise his answer until it was accepted as correct. This indicates that Derrick was, in fact, able to self-identify and self-correct the mistake without the need of extensive explicit CF. In other words, he already had the relevant knowledge in his repertoire—he just needed a little external mediation in order to correct the errors himself. The interaction between Derrick and the ICALL system collaboratively and dialogically—through a written rather than a spoken mode—created a ZPD that promoted Derrick’s development in regard to understanding minor aspects (i.e., demonstrative and punctuation) relating to the ba-construction.

In addition to guidance on punctuation, the graduated CF was also effective in drawing the participants’ attention to a more difficult area of the ba-construction, i.e., the omission or incorrect form of the verb complement. In translating “My roommate fixed my bicycle yesterday afternoon,” Larry produced

![]() $$\raster="rg18"$$

(“Yesterday afternoon my roommate fix my bicycle –le”). His answer was rejected by the ICALL system as incorrect, because the ba-construction calls for an explicit description of the results of the verb action. The graduated CF moved from the most implicit option (“Hmm, so can you take a look at it again?”) to the next more explicit option (“Okay, so what’s the result of the verbal action?”). Based on this gradually more specific feedback, Larry was able to correct his own error by revising the predicate from

$$\raster="rg18"$$

(“Yesterday afternoon my roommate fix my bicycle –le”). His answer was rejected by the ICALL system as incorrect, because the ba-construction calls for an explicit description of the results of the verb action. The graduated CF moved from the most implicit option (“Hmm, so can you take a look at it again?”) to the next more explicit option (“Okay, so what’s the result of the verbal action?”). Based on this gradually more specific feedback, Larry was able to correct his own error by revising the predicate from

![]() $$\raster="rg19"$$

(“fix perfective –le”) to

$$\raster="rg19"$$

(“fix perfective –le”) to

![]() $$\raster="rg20"$$

(“fix-good perfective –le”).

$$\raster="rg20"$$

(“fix-good perfective –le”).

The analysis of the data also shows that, in a number of cases, in their efforts to identify and correct various syntactic aspects of the ba-construction, the participants benefited from the graduated CF jointly provided by the ICALL system and the tutor, who was present during the ICALL session. Excerpt 1 documents Stacy’s interaction with both the ICALL system and the tutor during the first translation task.

Excerpt 1

1 Stacy: ((Upon finishing and reviewing her first answer))

2 I’m pretty confident about this ((chooses the highest confidence level and

3 submits her answer)).

4 T(utor): ((Smile)).

5 Stacy: ((The computer rejects her answer and offers an implicit prompt:

6 “Hmm, can you take a look at it again?”)) Oh, my gosh, haha

7 ((Stacy shows a little disappointment)).

8 Stacy: ((Highlighted

![]() $$\raster="rg21"$$

“yesterday afternoon”)).

$$\raster="rg21"$$

“yesterday afternoon”)).

9 Um (+++) do I need to move this here?

10 T: (++) You could try.

11 Stacy:

![]() $$\raster="rg22"$$

“My roommate,” maybe

$$\raster="rg22"$$

“My roommate,” maybe

![]() $$\raster="rg23"$$

$$\raster="rg23"$$

12 “my roommate yesterday afternoon.”

13 Stacy: ((Highlights

![]() $$\raster="rg24"$$

“fix-complete-perfective”)).

$$\raster="rg24"$$

“fix-complete-perfective”)).

14 Um, oh, it’s probably with the verb again ((laughs)).

15 This is the part I usually mess up ((looking toward the tutor)).

16 Stacy: I can probably take this

![]() $$\raster="rg25"$$

“possessive de” out.

$$\raster="rg25"$$

“possessive de” out.

17 T: No, here you can’t.

18 Stacy: Okay.

19 Stacy: ((Stacy chooses confidence level 4 and submits her second answer.

20 However, the computer rejects her answer as incorrect and offers

21 feedback: “Okay, so what’s the result of the verbal action?”)).

22 Okay. So the result is not right.

23 T: (++) What could it be?

24 Stacy:>Oh, could it be

![]() $$\raster="rg26"$$

:: “good.”

$$\raster="rg26"$$

:: “good.”

25 ((Stacy changes

![]() $$\raster="rg27"$$

“fix-complete” to

$$\raster="rg27"$$

“fix-complete” to

![]() $$\raster="rg28"$$

“fix-good”))?

$$\raster="rg28"$$

“fix-good”))?

26 T: Why, why do you think so?

27 Stacy: Because it’s like, fixed it, so that, it’s (++) good, like …

28 T: It’s working?

29 Stacy: Yeah. (+) Let me try that.

30 ((Stacy chooses confidence level 4, and submits her answer)).

31 Stacy:((The computer accepts Stacy’s answer as correct and displays “Congratulations!

32 That’s exactly right!” Stacy is very happy and smiles broadly.))

33 T: That’s exactly right! It’s not finished. It’s fixed well.

34 Stacy:Okay. So my resultative verb is a little bit shaky at the moment

35 ((then Stacy moves on to the next question)).

Stacy’s translation of the ba-construction—

![]() $$\raster="rg29"$$

(“Yesterday afternoon, my roommate fixed my bicycle”)—was in many regards grammatically correct. It satisfied the major syntactic requirements of the ba-construction: the word order was correct, the predicate included a resultative verb compound (RVC), and the use of the perfective marker –le was also correct. However, the real issue related to the RVC

$$\raster="rg29"$$

(“Yesterday afternoon, my roommate fixed my bicycle”)—was in many regards grammatically correct. It satisfied the major syntactic requirements of the ba-construction: the word order was correct, the predicate included a resultative verb compound (RVC), and the use of the perfective marker –le was also correct. However, the real issue related to the RVC

![]() $$\raster="rg30"$$

(“fix-complete”), which does not express the idea that the bicycle has been fully fixed and restored to good working condition. Stacy’s usage merely indicated that the roommate has finished working on the bike. The correct RVC in this context is

$$\raster="rg30"$$

(“fix-complete”), which does not express the idea that the bicycle has been fully fixed and restored to good working condition. Stacy’s usage merely indicated that the roommate has finished working on the bike. The correct RVC in this context is

![]() $$\raster="rg31"$$

(“fix-good”). The most implicit CF provided by the ICALL system (line 6) was not enough to enable Stacy to identify her error. In contrast, the second CF provided by the ICALL system was more explicit and specifically focused on the issue: “So what is the result of the verbal action?” (line 21). At this point, Stacy was fully convinced that the real issue was related to the RVC structure: “Okay, so the result is not right” (line 22). Sensing that Stacy was on the right track to finding the correct resultative word for the RVC structure, the tutor followed up with a leading question: “What could it be?” (line 23). In response, Stacy produced the correct answer,

$$\raster="rg31"$$

(“fix-good”). The most implicit CF provided by the ICALL system (line 6) was not enough to enable Stacy to identify her error. In contrast, the second CF provided by the ICALL system was more explicit and specifically focused on the issue: “So what is the result of the verbal action?” (line 21). At this point, Stacy was fully convinced that the real issue was related to the RVC structure: “Okay, so the result is not right” (line 22). Sensing that Stacy was on the right track to finding the correct resultative word for the RVC structure, the tutor followed up with a leading question: “What could it be?” (line 23). In response, Stacy produced the correct answer,

![]() $$\raster="rg32"$$

(“good”), and revised her answer accordingly (lines 24–25). In addition to producing a correct answer, more critically, Stacy was able to explain why her choice of the resultative word was appropriate: “The bicycle is fixed so that it’s good now.” Based on this understanding, Stacy submitted her third revision, which the ICALL system accepted as correct. A congratulatory message appeared on the computer screen, and Stacy expressed great pleasure in regard to her interaction with the ICALL system and in regard to the fact that she had persisted and ultimately worked out the correct answer based on a more complete understanding of the resultative component of RVC in the ba-construction.

$$\raster="rg32"$$

(“good”), and revised her answer accordingly (lines 24–25). In addition to producing a correct answer, more critically, Stacy was able to explain why her choice of the resultative word was appropriate: “The bicycle is fixed so that it’s good now.” Based on this understanding, Stacy submitted her third revision, which the ICALL system accepted as correct. A congratulatory message appeared on the computer screen, and Stacy expressed great pleasure in regard to her interaction with the ICALL system and in regard to the fact that she had persisted and ultimately worked out the correct answer based on a more complete understanding of the resultative component of RVC in the ba-construction.

As noted previously, there were instances in which the ICALL system was not able to locate the source of the error such that it failed to provide effective graduated CF. The data analysis shows that the participants seemed to have difficulty determining the correct location of the perfective marker –le, particularly in post-verbal positions. In translating the first sentence, Larry produced

![]() $$\raster="rg33"$$

(“write –le on the blackboard”). In response, the graduated CF provided by the ICALL system was not particularly relevant or useful: “You might be right already, but the translation you provided is not exactly what I have on file. Can you please try it one more time?” This CF option is typically shown to the participants when the ICALL system has exhausted all the possible potential answers and still cannot find a match. As such, it serves as a catch-all clause for all the cases that the system cannot handle by itself. Seeing that the CF series provided by the ICALL system was ineffective, the tutor intervened by informing Larry that the issue at hand pertained to the placement of the perfective marker –le. With this information, Larry ventured a guess that the perfective marker –le could be placed at the end of the sentence, just before the

$$\raster="rg33"$$

(“write –le on the blackboard”). In response, the graduated CF provided by the ICALL system was not particularly relevant or useful: “You might be right already, but the translation you provided is not exactly what I have on file. Can you please try it one more time?” This CF option is typically shown to the participants when the ICALL system has exhausted all the possible potential answers and still cannot find a match. As such, it serves as a catch-all clause for all the cases that the system cannot handle by itself. Seeing that the CF series provided by the ICALL system was ineffective, the tutor intervened by informing Larry that the issue at hand pertained to the placement of the perfective marker –le. With this information, Larry ventured a guess that the perfective marker –le could be placed at the end of the sentence, just before the

![]() $$\raster="rg34"$$

ma question word, to express the notion that the whole idea is in the past. He, therefore, promptly revised his answer to

$$\raster="rg34"$$

ma question word, to express the notion that the whole idea is in the past. He, therefore, promptly revised his answer to

![]() $$\raster="rg35"$$

? (“Did she lock her keys in the car again?”), which was correct.

$$\raster="rg35"$$

? (“Did she lock her keys in the car again?”), which was correct.

4.2 Participants’ reflections

The second research question considers the participants’ perceptions of the ICALL system in general and the graduated CF in particular in helping them learn the ba-construction. The analysis of the transcripts of the post-enrichment interview data shows that the participants generally expressed positive views on the effectiveness of the ICALL system in helping them learn the various aspects of the ba-construction. For example, one aspect of the ICALL system that Larry liked most was that he felt the feedback provided was very “personal” and functioned like “a teacher on the Internet” with whom he could communicate by typing “back and forth.”

Excerpt 2

1 T: So you, you definitely like the computer-based exercises=

2 Larry: =The most, yes.

3 T: >Can, can you elaborate on that,< How-, Why, why do you like it the most?

4 Larry: Um, I think it (++) um, it was more personal, ah, perhaps the messages

5 that came in the dialog box, when you didn’t do it right, it was like,

6 “Hmm, that’s not it, look at the verb phrase.” I think it was almost like

7 having a teacher on the Internet ((laughing)) that you’re typing back

8 and forth. And, sure, the program needs like, more work on it, so it can

9 get more answers that are potential. But it was still-, it seems to me, if

10 I wanted to learn Chinese (+) on my own, and I didn’t want to take [a]

11 cla:ss, I would use the program, and it could really, I think teach me=

12 T: = Okay.

While Larry pointed out that the program had room for improvement, he nonetheless acknowledged that the ICALL system has pedagogical value, especially for learners who want to learn Chinese on their own. Some participants mentioned that the graduated CF provided by the ICALL system, particularly the implicit feedback, was useful in that it provided an opportunity for them to locate and revise the problemsthemselves. Chris, as shown in Excerpt 3, felt strongly about the pedagogical value of using implicit CF as it afforded him an opportunity to “pick out what is wrong” by himself, a practice that is likely to help him recognize the same type of error in different contexts in his future learning.

Excerpt 3

If you say, look at it again, even just looking at it the second time, rings something. You can, half the time, you’ll find your mistakes: “Oh, I forgot the –le at the end, I’m so dumb.” And, then, if you really don’t get it, you really can’t see it, having the computer point to it, and say “This is where you should look. What’s wrong here?” And, you say, “Oh, what is wrong here?” “Oh:, and I got it. ” But it is, I think it is good not to point to it right away, because instead of kind of giving you the answer like: “Look at the end of the sentence, do you have –le?” ((laughing)), like, let me look at it again, and let me figure out it myself. If I can figure [it] out myself, that’s gonna be more beneficial than having it pointed out to me.

On the other hand, the participants did comment on the ICALL system’s inability to provide pertinent CF in some occasions. For instance, Derrick’s translation

![]() $$\raster="rg36"$$

? (“Did she lock the keys in the car again?”) was rejected by the ICALL system as incorrect, because it was looking for

$$\raster="rg36"$$

? (“Did she lock the keys in the car again?”) was rejected by the ICALL system as incorrect, because it was looking for

![]() $$\raster="rg37"$$

(“her keys”) for the grammatical object slot (i.e., Derrick only provided

$$\raster="rg37"$$

(“her keys”) for the grammatical object slot (i.e., Derrick only provided

![]() $$\raster="rg38"$$

(“keys”)). The prompt Derrick received from the ICALL system for this particular iteration was not particularly helpful: “You might be right already, but the translation you provided is not exactly what I have on file. Can you please try it one more time?” Derrick looked at the feedback for a while, and eventually said “I have no idea how to translate this.” However, the translation provided by Derrick was, in fact, correct because the pronoun “her” can be inferred and thus omitted from the context—a practice that is not uncommon in Chinese.

$$\raster="rg38"$$

(“keys”)). The prompt Derrick received from the ICALL system for this particular iteration was not particularly helpful: “You might be right already, but the translation you provided is not exactly what I have on file. Can you please try it one more time?” Derrick looked at the feedback for a while, and eventually said “I have no idea how to translate this.” However, the translation provided by Derrick was, in fact, correct because the pronoun “her” can be inferred and thus omitted from the context—a practice that is not uncommon in Chinese.

5 Discussion

The first research question focused on the effect of the graduated CF approach on language learning in an ICALL environment. Overall, the analysis shows that the graduated approach to providing CF in the ICALL system appeared to be an effective pedagogical tool in mediating the participants’ learning of the ba-construction. When the CF became more specific, the participants were more likely to locate the issue and self-correct the error in question. For instance, when the ICALL system provided a more specific feedback on Stacy’s problematic area (i.e., resultative), Stacy was able to act on this information, and worked out an acceptable answer that include the correct components of the grammatical construction. This finding corroborates Heift’s (Reference Heift2004) study on learner uptake of CF in German ICALL system E-Tutor. She reported that when the CF was more explicit and prominent, her students were more likely to correct their errors in grammar and vocabulary exercises. Similar results have been reported in non-ICALL studies. For example, Han (Reference Han2002) noted that when targeted at specific L2 forms, CF can be especially useful in helping learners notice mismatches between their own language production and target-like forms.

The mechanism of CF designed in this study differs from previous work in several important aspects. It differs from the CF provided in the C-DA project (Poehner & Lantolf, Reference Poehner and Lantolf2013; Poehner, Zhang, & Lu, Reference Poehner, Zhang and Lu2015) in that the type of CF provided in this study was contingent on learners’ language production, not recognition. Another difference pertains to the selection of which linguistic feature to focus on. The CF provided in the ICALL system reported in this study takes an iterative process and focuses on one error at a time, a feature that is similar to the German ICALL system E-Tutor (Heift, Reference Heift2010b). Yet it differs from the E-Tutor in that CF reported in this study was graduated in nature (moving from more general to more specific), whereas in E-Tutor, it was prioritized according to frequency and error type (e.g., first focus on word order, then subject, then object, and finally prepositional phrase).

L2 microgenetic development in previous research has primarily been studied in the context of moment-to-moment interactions between language learners and mediators in face-to-face scenarios (Aljaafreh & Lantolf, Reference Aljaafreh and Lantolf1994; Lantolf & Poehner, Reference Lantolf and Poehner2011; Poehner, Reference Poehner2008; van Compernolle, Reference van Compernolle2011). Using conversational analytic method, van Compernolle (Reference van Compernolle2011) illustrated how one learner progressed in cognitive function in sociopragmatic concepts of French second person pronouns in one-hour one-on-one concept-based instruction tutorial. In the present study, the majority of the CF or mediation was realized through computer-mediated means. However, the microgenetic development documented in the ICALL environment, as the results show, parallel those in the more traditional face-to-face context. In addition, the provision of graduated CF by the ICALL system to understand and intervene in L2 development resonates with practices advocated by Dynamic Assessment (Lantolf & Poehner, Reference Lantolf and Poehner2004; Poehner, Reference Poehner2007, Reference Poehner2008). For instance, Chris expressed that figuring out something (not just language) by himself is more valuable because “now that I know that is, I can see it the next time I do it.” In other words, the amount of support provided to Chris by the ICALL system enabled him to stretch beyond his independent performance. Yet at the same time, it also provided insights in relation to his emergent abilities. The graduated approach to providing CF affords an opportunity for the participants to take on as much responsibility for task completion as possible, and the ICALL system (and at times, the tutor) remain ready to intervene when the participants “slip over the edge” of their abilities (Newman, Griffin, & Cole, Reference Newman, Griffin and Cole1989: 87).

The analysis also found instances in which the ICALL system failed to locate the source of the error (e.g., the placement of the perfective marker –le) and thus failed to provide effective graduated CF. At such junctions, the tutor intervened and remedied the situation by providing necessary CF to the participants. This was not an intended feature in the original research design. The presence of the human tutor in an ICALL environment may have hindered the effectiveness of the graduated CF of the ICALL system being used as a stand-alone computer program. While a completely independent ICALL system may be desirable, in technology-mediated learning environments, it is not entirely unusual to have an instructor available to help the learners navigate the various technology and non-technology-related hurdles in L2 learning. The interview data from this study showed that the participants generally acknowledged the pedagogical value of this tool and appreciated the tutor’s remedial CF when the ICALL system broke down and failed to do its part.

The second research question asked about the participants’ perceptions toward the graduated approach of CF. The interview data revealed a preference toward implicit CF by some participants. For example, Chris indicated that implicit CF provides him with opportunities to figure out the issue by himself, and regarded it as more beneficial than having the correct answer provided to him. Even the most implicit CF of having him look at his answer one more time “rings something.” This finding corroborates results in Panova and Lyster (Reference Panova and Lyster2002), who found that students prefer implicit types of CF (e.g., recasts). Ferris et al.’s (2013) reported that students appear to learn more with indirect/implicit CF. One plausible explanation is that implicit CF requires more language processing (noticing or rehearsing in short-term memory) on the part of the learner in order to turn explicit linguistic knowledge into implicit knowledge (see DeKeyser, Reference Dekeyser2003; Ellis, Reference Ellis2005; Ellis, Loewen, & Erlam, Reference Ellis, Loewen and Erlam2006; Ellis & Sheen, Reference Ellis and Sheen2006; Long, Reference Long2007 for discussion on explicit/implicit learning/knowledge).

Another finding emerged from the interview pertains to the quality of the CF provided by the ICALL system. By design, the graduated approach to the provision of CF in the ICALL system varies as a function of each participant’s actual language production, a practice that can be considered as “individualized” to each learner. For Larry, this type of CF was valuable because it was “personal” and resembled “a teacher on the Internet,” with whom he communicated back and forth through typing. This finding is consistent with Ferris et al.’s (2013) study in which the students acknowledges the value of individualized and interactive approach to teaching and learning. Similarly, other scholars have recognized the need to consider individual student responses when providing CF (Bitchener & Ferris, Reference Bitchener and Ferris2012; Ferris, Reference Ferris2006, Reference Ferris2010; Hyland & Hyland, Reference Hyland and Hyland2006).

The conventional understanding of the notion of “intelligence” in ICALL research leans more toward technology than toward language learning. The idea of intelligence in ICALL comes from the field of artificial intelligence, particularly in relation to NLP techniques (Schulze, Reference Schulze2008). To echo a call Oxford (Reference Oxford1993) made a quarter century ago that ICALL research has an obligation to integrate sound language learning and teaching principles the same way it integrates ever-evolving cutting-edge technologies, in this study, we proposed an alternative understanding on the notion of intelligence in ICALL: what makes an ICALL system intelligent is not simply the use of state-of-the-art technologies—although they are necessary—but how such technologies, NLP or otherwise, are creatively used to develop language-learning opportunities and to provide immediate, meaningful, and graduated CF in order to facilitate language development.

Clearly, the ICALL system in its current condition needs further improvement. Derrick’s struggle with the unhelpful CF highlighted the system’s failure to account for all potentially correct answers, particularly answers to open-ended questions. Although the core algorithm developed in the ICALL system was able to analyze a range of linguistic features (e.g., the ba-particle, word order, verb complement), the system still needed to determine whether the answers provided by the participants were grammatically correct. Because there is usually more than one way to express more or less the same meaning, the combination of different lexical and syntactic arrangements can dramatically increase the total number of potential correct answers. This challenge is well recognized in the ICALL literature (Heift, Reference Heift2010a; Meurers, Reference Meurers2012; Nagata, Reference Nagata2009). Nagata (Reference Nagata2009) showed that in order to provide a direct response to a simple question, one could obtain 6,048 correct sentences by considering possible well-formed lexical, orthographical, and word-order variants. However, that number jumps to a staggering one million if incorrect options restricted only to incorrect particles and conjugation choices were to be included. Heift (Reference Heift2010a) also recognized the infeasibility of exhaustively anticipating all potential mistakes students might make. To address this issue, Meurers (Reference Meurers2012) suggested to move away from a lower-level string-matching practice and move toward a more advanced and automated approach that calls for the utilization of NLP algorithms. This appears to be a major hurdle and more research is needed in this area in order for the field to move forward.

6 Conclusion

In this study, we have explored the effectiveness of a graduated approach to CF in a computerized environment. Drawing on Vygotskian sociocultural theory, we have developed a web-based ICALL system capable of analyzing learners’ language production from a relatively open-ended question format (i.e., a translation task) and providing a series of graduated CF that moves from more general and implicit to more specific and explicit. The microgenetic analysis has shown that the graduated approach to CF, provided by the ICALL system, and supplemented by the tutor, when needed, is effective in helping learners to self-identify and self-correct a number of grammatical issues (e.g., punctuation, verb complement) in regard to the Chinese ba-construction. In addition, the type and amount of assistance learners need can be taken as indications of their developing abilities in language learning (Poehner, Reference Poehner2008).

An important contribution of this study to the research on CF is that CF does not have to be static and intermittent, but rather graduated and interactive, in real-time. This dynamic view of CF aligns well to the notion of individualization of CF. Within the field of L2 writing, scholars have recognized the importance of considering individual student responses to CF (Bitchener & Ferris, Reference Bitchener and Ferris2012; Ferris, Reference Ferris2006, Reference Ferris2010; Ferris et al., Reference Ferris, Liu, Sinha and Senna2013; Hyland & Hyland, Reference Hyland and Hyland2006). In this study, we have shown that it is possible to tailor CF not only to each individual student, but also to each interaction or attempt to answer the question by considering his or her prior (incorrect) answer to the same question. To achieve this, we have benefited from the rapid advancement of state-of-the-art technologies from neighboring fields such as computational linguistics and natural language processing.

This study is not without limitations. In some cases, the ICALL system failed to identify problematic areas in some of the participants’ answers and, therefore, could not provide useful graduated CF due to the difficulty of predicting all the potential correct answers. A partial solution might be to inventorize potential errors by combining instructors’ knowledge about common errors and errors from large learner corpora. Another approach might be to design activities that allow learners to drag and drop words from a randomized but definitive set of words in order to circumvent the “unlimited number of answers” challenge. Additionally, the ICALL system will benefit from more fine-grained hinting such as highlighting only the problematic segment of a learner’s answer. One of the challenges, also room for future improvement, as commented by many participants in this study in post-enrichment interviews, is to “fine-tune” (Poehner, Reference Poehner2007: 325) the mediations generated by the ICALL system as learners improve their language abilities and become more agentive.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a RGSO Dissertation Support Grant from the College of Liberal Arts at The Pennsylvania State University. The author would like to thank the editor and three anonymous reviewers’ corrective feedback on earlier versions of this paper.