1. Introduction

The need to adapt learning environments to the characteristics of students has shaped teachers’ approach to teaching and learning in many different ways. In this respect, the interaction among learners and the teacher constitutes a fundamental part of a classroom environment that often, due to the traditional constraints of time and place, lacks a constant and continuous input from the teacher. In order to foster this interaction, mobile phones have been used to extend traditional classroom environments, allowing students to access content from different places, abandoning stationary devices to become technological nomads (Ally, Reference Ally, In Needham and Ally2008; Kukulska-Hulme, Reference Kukulska-Hulme2009).

Mobile instant messaging (MIM) applications are proposed as a virtual environment where the teacher can track students’ progress as well as give constant feedback in case any language errors are made during the interaction. The inherent characteristics of these applications, such as an instant delivery of messages through a pop-up mechanism, a list of users, a mechanism to indicate when they are available, or their synchronous and asynchronous character, make them fertile ground to put into practice a dynamic assessment (DA) approach (Feuerstein, Feuerstein, Falik & Rand, Reference Feuerstein, Feuerstein, Falik and Rand2003; Lantolf & Poehner, Reference Lantolf, Poehner, Shohamy and Hornberger2007, Reference Lantolf and Poehner2011; Poehner, Davin & Lantolf, Reference Poehner, Davin, Lantolf, Shohamy, Lair and May2017). This kind of assessment, based on Vygotsky’s (Reference Vygotsky1978) theory of mediation and zone of proximal development (ZPD), places emphasis on the process of developing cognition as well as the social context in which learning takes place, rather than on the product of this process. In other words, from a research point of view, the use of a DA approach has normally focused on analysing the gradual development of students, and different environments and types of DA have been used to achieve this end. However, most of the studies exploring DA in language learning have also pointed out its pedagogical value as a formative assessment instrument (e.g. Poehner, Zhang & Lu, Reference Poehner, Zhang and Lu2015; Yang & Qian, Reference Yang and Qian2017). This last type of DA will be the focus of the present investigation in which MIM and DA are implemented.

In this sense, either in a computerised or in-class version of DA, there is a need for providing constant feedback to learners as mediation becomes a fundamental element during the development of this type of approach. This mediation is normally carried out by the teacher, and in some cases students, responsible for intervention during social interaction. In order to achieve a higher degree of mediation during this process, MIM applications become a powerful tool to develop a DA due to their inherent characteristics such as ubiquity and accessibility. Thus, this investigation attempted to bridge the gap in the existing literature with regard to the use of a mobile-mediated DA to foster second language (L2) development as well as to further understand the potential of MIM to conduct this kind of assessment.

2. Literature review

Over recent years, computer-based language assessment and artificial intelligence involving the use of intelligent language tutoring systems have contributed to providing automated responses when a language error occurs (Heift, Reference Heift, Thorne and May2017). An example of such responses is the case of stealth assessment (Sharples et al., Reference Sharples, Adams, Alozie, Ferguson, FitzGerald, Gaved, McAndrew, Means, Remold, Rienties, Roschelle, Vogt, Whitelock and Yarnall2015; Shute, Reference Shute, Tobias and Fletcher2011; Shute & Ventura, Reference Shute and Ventura2013), where games are used to continuously track students’ progress and automated responses are given throughout the process. However, a limited set of answers may narrow the feedback provided to students as well as the possibilities of addressing problematic aspects in learners’ performance. In this sense, formative or pedagogical DA and mediation may help widen the type of responses given by students, which may result in more specific and individualised feedback.

Two different approaches to mediation have been observed in DA (Lantolf & Poehner, Reference Lantolf and Poehner2004). First, an “interventionist” approach consisting of a series of prompts or hints given by the mediator or instructor to students, in which the degree of explicitness varies gradually, and the mediator follows a pre-set scale that goes from most implicit to most explicit. This approach focuses on a specific aspect of the language and limits the conversation to a series of drills that students have to carry out. Second, an “interactionist” approach in which the mediator constitutes a fundamental element to help learners’ performance, detecting their difficulties and formulating responses for each of the problems students may have during the conversation (Feuerstein et al., Reference Feuerstein, Feuerstein, Falik and Rand2003). One of the main differences between these two conceptualisations is the degree of freedom the mediator has to respond to learners, with the “interventionist” being the most restrictive as materials and prompts are designed to predict the kind of difficulties students may encounter (Poehner & Lantolf, Reference Poehner and Lantolf2010). In order to further understand these two approaches to DA, the following literature review will be divided into “interventionist” and “interactionist” approaches to DA.

In this sense, studies involving DA in L2 learning have normally analysed students’ potential in the target language as well as explored the teaching and learning possibilities as a consequence of mediation processes. Interventionist approaches to DA have been widely used to assess students’ development, such as Kozulin and Garb (Reference Kozulin and Garb2002) who tested a DA of EFL text comprehension in a number of pre-academic centres in Israel. Through the use of a test-teach-test methodology, researchers were able to perceive the effects of mediation on students’ (n = 23) text comprehension. This procedure contributed to perceiving differences in students’ potential after the mediation. Similarly, Darhower (Reference Darhower2014) made use of an interventionist approach to analyse the past-tense narration through the synchronous computer-mediated communication of two Spanish learners. This type of assessment was also found to be a positive instrument to shed light on students’ ZPD and further understand students’ potential in the L2. Further interventionist approaches to DA such as Poehner and Lantolf’s (Reference Poehner and Lantolf2013) investigation explored the use of computerised dynamic assessment (C-DA) to analyse listening and reading comprehension in an L2 online test. By using a graduated prompt approach for each of the test items, the test not only collected information regarding students’ ZPD but also promoted learners’ abilities with regard to listening and reading. Similar studies making use of a graduated prompt approach, such as Ai’s (Reference Ai2017) or Poehner et al.’s (Reference Poehner, Zhang and Lu2015) investigations, confirmed these findings. In this latter study, students (n = 82) were given, apart from the test scores in listening and reading, a mediated score that indicated the prompts needed by each student. The researchers argued that the combination of both scores provided a precise diagnosis of students’ L2 development as well as relevant information to further teaching and learning.

On the other hand, interactionist approaches to DA such as Poehner and Lantolf’s (Reference Poehner and Lantolf2005) or Antón’s (Reference Antón2009) investigations into oral proficiency focused on student–teacher interaction as well as on the repetition of previous assessments to evaluate students’ development. Although a small sample size was used in both cases, results in the two studies highlighted the effectiveness of DA in better understanding learners’ abilities and addressing individual needs. Both studies also emphasised the possibility of promoting learners’ abilities through DA in line with most of the aforementioned interventionist approaches. Likewise, Shrestha and Coffin’s (Reference Shrestha and Coffin2012) investigation explored the value of tutor mediation in academic writing. An analysis of the tutor mediation associated with the DA sessions, student interviews, and a business studies tutor was evaluated. Mediational moves such as clarifying a task, asking to clarify meaning, or asking to consider a possible solution among others were used during DA. The analysis of this interaction showed that it helped students identify areas where they needed the most support.

Whether following an interactionist or an interventionist approach, the aforementioned studies into DA emphasised the use of DA as an evaluation instrument, in many cases being the pedagogical possibilities of this type of assessment an adjacent result. Likewise, it also seems necessary to overcome some of the challenges inherent to each approach such as the need to eliminate predetermined linguistic considerations common to interventionist approaches in order to provide a more individualised feedback, or the difficulty of interpreting the results of interactionist approaches in order to provide more appropriate responses. In this sense, taking these theoretical considerations into account and following Feuerstein et al.’s (Reference Feuerstein, Feuerstein, Falik and Rand2003) concerns on the great potential of dialogic mediation and the higher impact of open-ended mediation in revealing underlying difficulties and beginning the process of mediating development, this investigation attempted to combine an interactionist and interventionist approach. Following the graduated prompt approach (Campione & Brown, Reference Campione and Brown1985) in which a series of hints from most implicit to most explicit are given to students by the mediator, language learners were able to identify their mistakes during the interaction and the teacher was able to further understand students’ strengths and weaknesses depending on the prompt required and provide feedback. However, no specific errors, drills or specific linguistic cues common to interventionist approaches were expected during the interaction.

Furthermore, in order to cover the absence of studies with regard to mobile-assisted language learning and DA, we decided to explore further possibilities of MIM and open-ended interaction to foster language learning, investigating the potential of pedagogical DA in an L2 classroom. Through an analysis of the interaction in the application, we sought to answer the following questions: (1) Is the use of mobile-mediated DA beneficial for L2 development? (2) Is the use of MIM applications beneficial for conducting DA?

3. Study

This investigation involved two groups, each consisting of 30 participants who studied at the language centre of the University of Almería, Spain. Participants were Spanish speakers taking a B1 EFL course and had four teaching contact hours per week. The content given during the course met the parameters established by the CEFR for a B1 level, and the age of the participants ranged from 17 to 29, with 21 male participants and 37 female. The course was given over five months from October to February. WhatsApp was introduced in one of the groups studied (Group A) in which 30 students joined a chat group where DA was implemented. The university gave permission to the teacher to collect students’ phone numbers, and a WhatsApp group was created coding the identities of the participants. The popularity of the application avoided explanations about WhatsApp use as students had already mastered this MIM service. The second group studied (Group B) was used as the control group.

Both groups received traditional assessment through a grammar and vocabulary pre- and post-test as well as the same tuition and content. A communicative approach was used in both groups with the aim of improving students’ linguistic competence in the target language. Regarding the content provided in the course, the didactic units located in a B1 EFL book were used to guarantee a proper distribution of the target language skills, content and materials of the course. Group A and Group B had different timetables: A attended in the morning and B in the evening. In order to maintain the identities of the participants disguised, pseudonyms were used.

Practical considerations involved requesting students’ mobile phone number; creating a WhatsApp group with all the participants; guaranteeing all students had a smartphone with 3G connectivity and a data plan; minimising privacy threats (Boyd & Ellison, Reference Boyd and Ellison2007) by coding students’ names in the application and introducing common topics that did not include participants’ personal details; and scheduling a one-hour lesson in Group A to explain the activity and how to use the prompts in case any error was made.

Regarding task design, in order to maintain a constant thread of conversation, different B1 topics previously worked on in class were dealt with every week so that students could put into practice in-class focuses. A different student had to ask a minimum of one question per day, and students had to answer the questions raised in the group. A series of conditions were given to students in Group A: there was no word limit to the messages sent by participants during the interaction; the use of the English language was compulsory; there were no time restrictions to use the application; all the functionalities provided by the application could be used such as voice recording or image sharing. Nevertheless, for the purpose of the study only written data were analysed. The researcher participated in the conversation as he was the teacher of the groups investigated, becoming a mediator in the learning process of the participants and providing feedback when necessary. In this sense, thanks to the possibility of responding directly to a member of the group within the group conversation, feedback did not need to be provided in a timely manner; thus the teacher could respond to previous utterances where an error was made in case he was not present at the time of the conversation.

4. Methodology

The Creswell (Reference Creswell2003) fixed mixed methods was used as the data involved an analysis of quantitative and qualitative information. In the design of this investigation ex post facto criterion groups were analysed (Hatch & Lazaraton, Reference Hatch and Lazaraton1991; Shavelson, Reference Shavelson1981) as descriptive measures (central tendency and variability) were taken into consideration. The design involved a sequential quantitative–qualitative approach in which the qualitative phase was conducted once the quantitative phase had been carried out. Specifically, Onwuegbuzie and Teddlie (Reference Onwuegbuzie, Teddlie, Tashakkori and Teddlie2003) categorised this design as a qualitative follow-up interaction analysis where an analysis of the variance is followed by a subsequent qualitative analysis of the data presented during the interaction. Following discourse analysis methodology as described by Nunan (Reference Nunan1992), a naturalistic investigation was used. Figure 1 presents the design of this investigation.

Figure 1. Design of the study

The experimental group was used to assess L2 development through DA as well as understand the potential of MIM to conduct this type of assessment. In contrast, the control group was used to evaluate students’ zone of actual development (ZAD) at different times of the course, although direct comparisons between both groups could not be drawn due to the higher exposure of the experimental group to language practice. The ZAD showed learners’ level at a particular point in the learning process. With regard to the analysis in the experimental group, a scale with prompts (Figure 2) was used when students made a mistake in order to mediate during the learning process. This scale was designed and explained in class so there was not only one mediator during the interaction. The researcher, who was at the same time the teacher of the groups under investigation, provided feedback to students through an inventory of prompts when non-target-like features occurred. As previously mentioned, these prompts were given from most implicit to most explicit. Measures regarding the number of prompts used were collected in four stages of the interaction (after one month; after two and a half months; after three and a half months; after five months) in order to analyse the pedagogical DA at different times. Furthermore, a grammar and vocabulary pre- and post-test at the beginning and end of the course was administered in both groups in order to observe students’ development throughout the tuition.

Internal threats to validity in mixed methods research (Johnson, Onwuegbuzie & Turner, Reference Johnson, Onwuegbuzie and Turner2007) as well as socio-economic metadata were considered at the beginning of the activity in order to guarantee the participation of all the students. In this regard, the teacher confirmed that students participating in the experiment owned a mobile device with a data plan in order to use the application. Furthermore, the university provided free-of-charge Wi-Fi connectivity and mobile devices to borrow which, in this case, were not necessary. Interrater reliability was taken into consideration for the analysis of the samples in the application; a second rater was used during this process in order to guarantee a proper calculation of the prompts used. In the case of the grammar and vocabulary test, a multiple-choice structure presented no issues in this regard. Nevertheless, an external evaluator was used during the evaluation process in order not to compromise the results of the research.

5. Data collection instruments

5.1 Grammar and vocabulary test

A grammar and vocabulary test was given to students in both groups at the beginning of the course. This test was administered in order to guarantee a proper range of participants taking part in this investigation. An end-of-the course grammar and vocabulary test was also administered in both groups to observe potential differences in the ZAD of the groups under investigation. Both tests were conducted in a classroom environment and their length was 70 minutes. Regarding the design of the test, following Fulcher and Davidson’s (Reference Fulcher and Davidson2007) study of test creation, the tasks and items in the test were piloted at a partner university and statistical analysis was carried out to guarantee its discrimination and reliability. It consisted of a total of 150 items where grammar and vocabulary were targeted. The overall score ranged from 0 to 150 points, with 0–30 corresponding to A1 level, 30–60 to A2, 60–90 to B1, 90–120 to B2 and 120–150 to C1.

5.2 Inventory of teacher prompts

An inventory with the prompts used by the mediator was designed in order to follow a gradual sequence when giving feedback from most implicit to most explicit. Figure 2 shows the sequence of prompts used by the teacher during the interaction. The teacher strictly followed this scale starting with Prompt 1 every time an error was made. This feedback was given in instances where a non-target-like feature was pointed out, whether explicitly or implicitly (Iwashita, Reference Iwashita2003). Negative feedback was subdivided in the inventory following a gradual degree of explicitness: recasts, a restatement of a non-target-like form and in a more target-like one (Long, Reference Long, Ritchie and Bhatia1996); elicitations, a response to a previous instance pointing at a more target-like form without giving any kind of metalinguistic information; and explicit metalinguistic explanations in case the previous negative feedback had not achieved its purpose. All error categories were corrected, whether grammatical, lexical, syntactical, word order, or spelling, among others. Higher-level errors such as style and register were not taken into consideration as long as students produced target-like forms. Concerns regarding the challenges generated by DA in computer-mediated communication (see McNeil, Reference McNeil2018), such as visual (e.g. gestures) or auditory cues (e.g. intonation), which cannot be produced in an online environment, were minimised thanks to the use of emoticons found in MIM applications. Figure 2 presents the inventory of prompts used during the investigation.

Figure 2. Inventory of teacher prompts (based on Poehner & Lantolf, Reference Poehner and Lantolf2010)

5.3 Mark sheet

A mark sheet was designed in order to account for the feedback provided by the mediator to each of the students when they made an error. Due to high participation in the application, the proficiency level of students gave rise to many situations where negative feedback was needed. Thus, this mark sheet consisted of an account of the interaction in the application, including the name of the participants, the prompt given and the date when it took place.

6. Data collection procedure

First, as mentioned previously, the researcher made use of a mark sheet daily to account for the name, prompts given and date when the repair move took place. Subsequently, the information, which was collected using the web version of the platform, allowed the researcher and second rater to go through the data obtained and account for the degree of mediation used and students’ ZPD. To this end, four different measurements at different times of the interaction were used to explore students’ development. The first rater, who acted as mediator and was also the teacher and researcher of the groups under investigation, trained the second researcher in the use of DA and the inventory of prompts used throughout the interaction. This process consisted of a 60-minute session where the inventory of prompts was put into practice with samples from the interaction. Subsequently, all the language productions in the application were analysed. Interrater reliability was calculated taking into consideration the number and type of prompts used throughout the interaction. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r = .964) and the percentage agreement calculated between the two raters (97%) indicated a strong agreement. With regard to the pre- and post-test, information was collected at two different times in the course and statistical analysis was used to evaluate the results obtained. Close-ended questions allowed the researcher to analyse this information individually through the use of SPSS. Practical considerations included arranging a specific room for the test in order to guarantee exam conditions.

7. Results and analysis

7.1 Quantitative procedures

In order to explore the use of mobile-mediated DA for L2 development, two different statistical analyses were carried out in this investigation to evaluate students’ ZAD and ZPD. First, in order to observe the ZAD in both groups, an evaluation of the pre and post grammar and vocabulary test was used. The second analysis took into consideration students’ ZPD in Group A by observing teacher prompts given to students at four different stages of the course.

The paired samples t-test was used to analyse statistically significant differences between pre- and post-test scores in both groups. A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test confirmed a normal distribution of the sample. Alpha level was set at .05 under a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis. Table 1 presents the results of pre and post test measures in Group A and B. The pre-test results in both groups did not yield any major differences between Group A and Group B, t(29) = –1.07, p> .05, indicating that there were no significant initial differences among the participants at the beginning of the activity. Thus, the ZAD was similar in both groups. Nevertheless, this did not mean that the ZPD was similar too. Post-test scores indicated statistically significant differences between both groups, t(29) = 3.27, p < .05, suggesting that the effect of DA in Group A had a positive impact on students’ performance. The mean score was 72.13 for Group A and 67.7 for Group B, indicating that, although both groups were at the B1 level at the end of the course, the improvement of Group A was significantly higher. Nevertheless, these measures took into consideration students’ grammar and vocabulary scores at the end of the course in the two groups but failed to prove students’ development within the interaction. A paired-samples t-test was also conducted to analyse differences between the pre- and post-tests in the two groups. Results yielded a significant improvement in Group A, t(29) = –20.17, p > .05, and Group B, t(29) = –16.57, p > .05, probably as a consequence of language instruction.

Table 1. Pre and post-test measures in Groups A and B

Although the post-test scores allowed us to perceive a higher improvement in the ZAD of the experimental group students, a direct comparison between the groups could not be drawn, as a higher amount of exposure and practice time of those in the experimental group limited this possibility. Thus, there was a need for evaluating students’ progress through DA, tracing the data that arose from the interaction. The inventory of teacher prompts was used to interpret students’ potential development by analysing four different measurements at different stages of the course. These four measurements took into consideration a mean of the prompts given to students at different times during the interaction. In order to have a more reliable estimation of students’ ZPD, this mean was calculated taking into account the total amount of instances per student before the measurement. This information was recorded in the application and its web version was used to analyse the data. Table 2 presents the number of messages in the app as well as the number of prompts provided by the teacher.

Table 2. Data on student and teacher production in Measurement 1 to 4

In the case of Measurement 1 taken after the first month of tuition, the mean per student for each of the categories in the inventory was calculated from a total of 139 repair moves in which the inventory of prompts was used. In order to observe the degree of explicitness of the prompts provided during the different measures taken, Figure 3 presents the absolute frequency for the prompts used. To this end, and as mentioned previously, this graduated approach was implemented from less to more explicit (1–7). Figure 3 presents the frequency and type of prompts provided during the interaction. Measurement 1 indicated a high degree of explicitness, often using Prompts 4 (The mediator points out the wrong word or words by writing them in capital letters), 5 (The teacher offers a more target-like form, recasts), and 7 (Explicit metalinguistic explanation). Measurement 2 was taken a month and a half after Measurement 1 in order to observe students’ potential development after a considerable amount of time using the application. The degree of explicitness was gradually reduced in Measurement 2, notwithstanding the fact that the mediator still had to use elicitations pointing out a particular error within the sentence, an emoticon indicating that it was necessary to think again about the sentence, or just repeating the whole utterance again was not enough to make students aware of the error. Measurement 3, taken after three and a half months from the start of the course, marked a turning point in students’ potential development, as absolute frequencies for Prompts 1 and 2 indicated that the degree of explicitness needed had been reduced. This finding was later confirmed in Measurement 4 taken at the end of course, where absolute frequencies for Prompts 1 (Emoticon indicating the person is thinking), 2 (Repeat the whole utterance as a question, elicitation) and 3 (Repeat just a part of the sentence with error, elicitation) were the most common during the interaction, indicating that often just by showing misunderstanding students were able to repair the conversation. In order to confirm statistically significant differences between the different measures taken, we made use of a one-way repeated measures ANOVA. Taking into consideration the scale of prompts followed during this investigation, a decrease in the mean score of the prompts in a particular measurement would indicate that the feedback provided tended to be more implicit, as given the degree of explicitness of the scale, fewer prompts were needed to make students aware of the error. The results of the ANOVA indicated a significant time effect in the number of prompts, Wilks’s lambda = .48, F(3, 26) = 9.18, p < .05, n2 = .51. Pairwise comparison was also calculated to evaluate the difference in the number of prompts between the different measurements and Bonferroni adjustment was used to counteract multiple comparisons. Results indicated no significant differences between Measurements 1 and 2 (p > .05). Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of the total frequencies of prompts during the interaction.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and pairwise comparison of the total frequencies of prompts during the interaction in Group A

* Statistically significant difference (p < .05).

Figure 3. Frequency of prompts provided to students during the interaction following the scale for intervention (1–7)

Nonetheless, significant differences were found between Measurements 1 and 3 (p < .05) and 1 and 4 (p < .05) indicating that the difference in the number of prompts was considerably lower by the end of the interaction. DA in this case helped students reduce the gap between their current and target language, thus not only evaluating but also contributing to L2 development.

In consequence, answering the first research question in this investigation, statistical analysis of ZAD and ZPD has shown the potential of pedagogical DA in L2 development, offering a wider picture of students’ linguistic competence. In the following section, we will tackle the second research question regarding the use of MIM applications for conducting DA.

7.2 Qualitative procedures

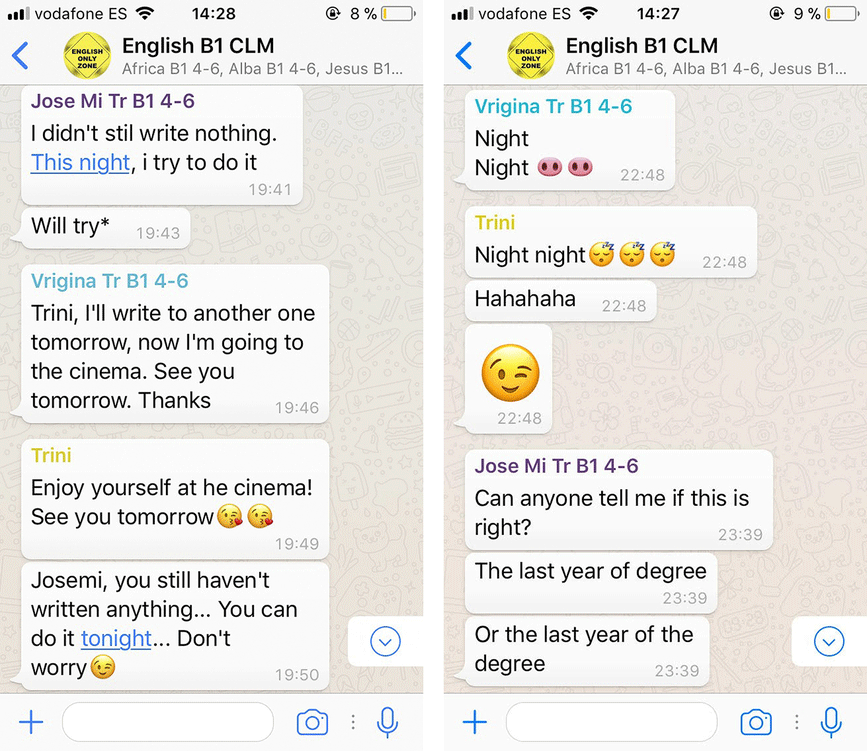

Natural observation as well as a systematic study of the interaction taking place in the application offered an insight into the characteristics of DA in the L2 classroom. Interactions between teacher and students were constant throughout the process, giving rise to different types of linguistic errors and becoming a rich environment for students’ practice, as reflected in Figure 4. Throughout this section, we will comment on some of the language-related episodes (LRE) that took place as well as the prompts used by the teacher in each of the cases. LREs, as described by Swain and Lapkin (Reference Swain and Lapkin1998: 326), were understood as any part of a dialogue where language learners discuss the language they are producing, reflect on the language use, or correct themselves or others. Figure 4 presents instances of the interaction in the application.

Figure 4. Screenshots of the conversation in the application

The following example was taken in Measurement 1 at the beginning of the course and shows a conversation between two students, Carlos and María (names are pseudonyms), and the teacher chatting about the environment and public transport in their hometown.

Example 1: Topic: Public transport

In this example, we can observe how while Carlos and Maria are speaking about public transport, Carlos makes a grammar mistake which, although not fundamental to understanding the sentence, requires the teacher’s participation in the conversation. The teacher starts by using Prompt number 1 in the inventory, but there is no reaction from Carlos. Prompt number 2 is used, but Carlos indicates he is not aware of where the error has been made. The teacher then repeats a part of the sentence with the error using Prompt 3, and Carlos repeats the sentence trying to confirm he was right. Prompt 4 is then used to say explicitly that there is a mistake in the sentence. Nevertheless, Carlos still did not know what the mistake was. Thus, a much more explicit form needed to be used by the teacher indicating in capital letters the problematic part of the sentence (Prompt 5), but Carlos once again indicates he does not know what is wrong in the sentence. Subsequently, the teacher provides a recast offering two possibilities so that Carlos can choose which of the two is the correct option. He finally selects the correct one showing that he has noticed where the error was made. This example, as well as many others, made students wonder about the language conventions, as students wanted to know why it was a mistake and if there was any rule that could be applied in that case. In addition, this conversation, as well as the rest of the messages sent in the application, were seen by all the participants in the WhatsApp group. Thus, even if the participants were not active while the conversation was taking place, they were able to access it later in the day, receiving the feedback provided by the teacher.

The interventionist approach used in this case was useful, as students would have continued the conversation without noticing the error due to the fact that the meaning of the sentence could be understood. The application gave the teacher the possibility of exploiting the synchronous and asynchronous characteristics of MIM; hence, explanations were not given to a single person but to the whole class.

Example 2 was obtained from Measurement 2, two and a half months after the start of the course. In this instance, we observe a conversation between Adrian and Jose (names are pseudonyms) where they are talking about working abroad.

Example 2: Topic: Working abroad

In Example 2, we can appreciate how the teacher takes part in the conversation in order to make sure students know “people” is plural in English. Prompt 1 and 2 had no effect on the student’s perspective on the sentence, as we can see in the student’s response where he even tries to exemplify what he considers an expensive city. The teacher tries again by specifically pointing out the part of the sentence with the error (Prompt 3) and later by saying explicitly that there is a mistake in the sentence (Prompt 4) but is still unsuccessful. It is not until Prompt 5, thanks to the use of capital letters, that the student is able to perceive the error in the sentence. In Measurement 2, we also observe the first comments of students in the group trying to work out the solution for a particular mistake pointed out by the teacher, hence involving cooperative learning (Slavin, Reference Slavin1990). This, as was previously mentioned in the analysis, would not happen without the teacher’s intervention as the student may not see the need for accuracy.

Example 3 was obtained in Measurement 3, three and a half months after the start of the course. This measure, as revealed in the statistical analysis, becomes a turning point in the inventory of prompts used by the teacher where more implicit prompts start to have an effect on students’ awareness of the errors. This example shows a conversation between Antonio and Judit (names are pseudonyms) talking about food and tapas bars in their hometown.

Example 3: Topic: Food and restaurants

In Example 3, we can observe how the use of explicit prompts to make the student aware of the mistake was unnecessary. Prompt 1 and 2 did not achieve its goal. Nevertheless, Prompt 3 provided enough information for Judit to realise she was making a mistake. As illustrated in Figure 2, there was an increase in the number of implicit prompts provided by the teacher in Measurements 3 and 4. This meant there was a drop in the number of prompts given by the teacher in comparison with Measurements 1 and 2, suggesting that students’ competence was higher. At the same time, the laborious nature of the job of the teacher, who many times had to reach Prompt 6 or 7 to make students aware of the error, was reduced.

Example 4 was obtained in Measurement 4, during the last month of the activity. In this case, the instance presented shows a conversation between Mario and Alba (names are pseudonyms) and the teacher, who was also participating actively in the interaction, about being a student at the university.

Example 4: Topic: Being a university student

In this case, Alba was able to notice she had made a mistake, and just because of the emoticon of the teacher (Prompt 1), she goes again through her sentence and is able to find and repair it. Further mistakes found in this example were also addressed through the use of the inventory of prompts such as “mi case” or the absence of the verb “to be”. Prompts 2 and 3 were used respectively to correct these errors. The teacher in Example 4 did not have to use any implicit correction to make the student aware of the error; hence, some of the time, the use of the emoticon became the equivalent of a pause in a normal conversation. That made the student reflect on her language production, which often becomes fundamental for L2 development. The use, in this case of Prompt 1, or Prompts 2 and 3, indicated an increase in the linguistic competence and accuracy of the students in the L2.

Answering the second research question, MIM applications were found to be very helpful for conducting a pedagogical DA approach as the teacher and students could participate “on the go”, generating a higher number of language productions where feedback and explanations about language conventions were provided through a graduated approach. Students, in many cases, wondered about the rules to be applied when they made a mistake, which led to participants reflecting on language use while interacting with their peers. Challenges observed in DA showed how teachers struggle to make split-second decisions in order to carry out a graduated prompt approach (Davin, Herazo & Sagre, Reference Davin, Herazo and Sagre2017; Davin, Troyan & Hellman, Reference Davin, Troyan and Hellmann2014), such as the one used in this investigation. Nevertheless, due to the synchronous and asynchronous characteristics of MIM, the teacher was able to provide more appropriate responses and had fewer difficulties using the scale for intervention. The instructor had the possibility to reply anytime and anywhere to the last message sent by any of the participants or directly to any other message in which feedback was required. Messages remained saved within the application, helping track the messages and fostering more concise and individualised learning.

8. Discussion

The need to provide students with a more accurate evaluation of their ZAD and ZPD has been one of the most common goals in the DA literature (e.g. Antón, Reference Antón2009; Poehner et al., Reference Poehner, Zhang and Lu2015). Likewise, a very common finding, apart from an accurate diagnosis of students’ ZPD, has been the pedagogical potential of this type of assessment. Emphasising this last aspect, the results obtained in this case study have contributed to further understanding the pedagogical value of formative or pedagogical DA. Students decreased the number of prompts needed over time and required less explicit prompts in line with previous DA studies (e.g. Aljaafreh & Lantolf, Reference Aljaafreh and Lantolf1994; Yang & Qian, Reference Yang and Qian2017), which suggested an increase in their linguistic competence as well as in the degree of reflection on the language used as a consequence of mediation strategies in the platform. The findings also indicated that the potential of mediator–learner as well as learner–learner interaction to promote L2 development already highlighted in previous MIM research (e.g. Andujar, Reference Andujar2016; Andujar & Salaberri-Ramiro, Reference Andujar and Salaberri-Ramiro2019; Andújar-Vaca & Cruz-Martínez, Reference Andújar-Vaca and Cruz-Martínez2017; Bueno-Alastuey, Reference Bueno-Alastuey2013; Jepson, Reference Jepson2005) may also be applied to DA approaches. The conversation was not limited to a certain number of grammatical structures or forms, which was found to be one of the main challenges of interventionist approaches (McNeil, Reference McNeil2018), giving students the possibility to experiment with new language they may not have used in a classroom environment.

Due to the fact that this approach to DA is original to this investigation, results cannot be directly compared with similar literature in the field. However, previous research into DA making use of a graduated prompt approach such as Poehner and Lantolf’s (Reference Poehner and Lantolf2013), Poehner et al.’s (Reference Poehner, Zhang and Lu2015) or Ai’s (Reference Ai2017) also emphasised the possibilities of DA to shed light on students’ weaknesses and strengths in the target language. Further factors such as the asynchronous and sometimes synchronous character of MIM also became fundamental to appropriately develop the pedagogical DA. As opposed to studies exploring C-DA in which automatic responses were given to predetermined linguistic cues through the use of an inventory of prompts (e.g. Poehner et al., Reference Poehner, Zhang and Lu2015; Teo, Reference Teo2012), or where students could select among the mediation prompts in the computer program (e.g. Yang & Qian, Reference Yang and Qian2019), the asynchronous characteristics of MIM allowed the teacher to observe and analyse the conversation, and provide appropriate responses to participants in the interaction guaranteeing the quality of the feedback. At the same time, the possibility of replying directly to each of the students within the group simplified the development of this type of DA.

9. Conclusion

Throughout this investigation, MIM applications were used to put into practice a pedagogical DA approach to foster students’ language abilities in the L2. The use of MIM attempted to maximise the advantages of this type of assessment using the inherent characteristics of mobile devices and limiting the drawbacks found in previous research on DA. Challenges such as the need to avoid predetermined linguistic aspects in order to provide a more individualised learning common to interventionist approaches, or the difficulty of interpreting the results of DA common to interactionist approaches, were overcome through MIM. In line with previous studies (e.g. Abdolrezapour, Reference Abdolrezapour2017; Poehner et al., Reference Poehner, Zhang and Lu2015), DA provided the possibility of exploring students’ ZPD in the experimental group and changed the paradigm of traditional test-based assessment that, although it was also used in both groups, provided a limited picture of students’ language abilities. To address this issue, apart from the ZAD, students’ ZPD offered a more detailed evaluation of linguistic potential in the experimental group.

Results indicated that by the end of the interaction, students needed less explicit feedback to realise their language errors within the application, indicating that students were able to perceive faster a particular language error and produce a more target-like form. Nevertheless, this investigation did not measure the actual learner uptake apart from the grammar and vocabulary test, thus conclusions can only be drawn regarding the type of feedback used in the scale for intervention and its development throughout the experiment. Researchers into DA, such as Aljaafreh and Lantolf (Reference Aljaafreh and Lantolf1994) and Lantolf and Poehner (Reference Lantolf and Poehner2011), understand students’ development as not only focusing on an appropriate performance but also emphasising self-regulation and control over that performance. If feedback is provided in a particular way, whether implicitly or explicitly, learners are treated equally regardless of their level of control over a specific language feature. Thus, it would be hard to determine how much regulation a learner is gaining over her or his performance and, consequently, to what extent the process of language development remains hidden or inhibited (Lantolf & Poehner, Reference Lantolf and Poehner2011). In this sense, the tendency towards implicit feedback may indicate that students gained control over their language performance. However, limitations such as students becoming more attentive to their mistakes in the interaction as they got used to the teacher prompts may affect the number of implicit prompts in this investigation.

Regardless of whether the teacher had to intervene in the conversation when necessary, the active participation of the mediator even when mediation was not needed as well as open-ended conversation created an environment that favoured dialogic mediation. In this vein, mobile-mediated DA expanded in-class time and became an individualised source of L2 input and feedback. Notwithstanding this fact, practical implications such as the time investment of the teacher who had to provide constant feedback may not be feasible in many instructional settings; thus further research into DA may include peer feedback or native speaker tutors that could help reduce teacher workload.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank professors Mary Spratt and Tim Spratt who greatly contributed to this investigation. Likewise, I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers who provided insightful comments and expertise to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Ethical statement

The identities of participants in this investigation remained disguised in order to meet ethical concerns. Likewise, the students in this research participated voluntarily and gave permission to the researcher to publish all the data concerning the project carried out. With regard to the data collection, an external evaluator was used during the evaluation process together with a second rater, which confirmed interrater reliability in the sample under investigation. The author certifies that there was no conflict of interest during the development and publication of this research. The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

About the author

Alberto Andujar is a lecturer and researcher at the University of Almería (Spain). He specialises in second language learning and technology, telecollaboration, and computer- and mobile-assisted language learning. He is also the author of different international research articles in these fields and a member of the virtual worlds and serious games SIG in EuroCALL.

Author ORCIDs

Alberto Andujar, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8865-9509