1 Introduction

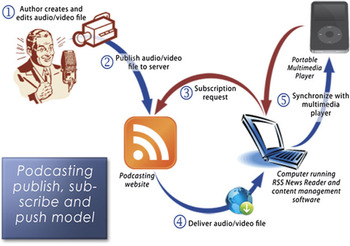

At the risk of overstating the obvious, technology is reshaping teaching and learning by supporting, expanding, and enhancing course content, learning activities, and teacher-student interactions. A new wave of “enabled wifi” personal multimedia players is expanding students’ access and mobility and is providing opportunities for them to time-shift their learning activities. MALL is gaining popularity as it is integrated into the foreign language curriculum, providing new learning tools to the “net generation” (Oblinger & Oblinger, Reference Oblinger and Oblinger2005). For this new generation of students who have been encouraged to “to take control of what they learn” (Kukulska-Hulme & Shield, Reference Kukulska-Hulme and Shield2007) MALL, and particularly podcasting, can play a key role by providing them with instructional materials and low-cost tools as they work toward developing language proficiency. As an audio/video content delivery approach based on web syndication protocols (RSS and/or Atom, see Figure 1), podcasting provides increased flexibility and portability, and allows for time-shifting and multitasking (Thorne & Payne, Reference Thorne and Payne2005). In this regard, it should be emphasized that syndication is the cornerstone of podcasting. By allowing subscription and notification, this XML-based protocol shifts audio/video file handling from a static and manual mode to a dynamic and automated mode.

Fig. 1 Podcasting publish, subscribe, and push model

Time constraints are often a major factor in the completion of course assignments for the working and/or the commuting student. The academic use of podcasting allows for constant accessibility to the teaching and learning experience, while enabling the on-demand learner to control and personalize the learning process (Lee & Chan, Reference Lee and Chan2007). Academic podcasting gives student learners “on-demand deliverability” (Donelly & Berge, Reference Donelly and Berge2006), and allows them to organize their studying into “manageable chunks” (Chinnery, Reference Chinnery2006). It also allows teachers to restructure classroom time and to convert the popular iPod and other MP3/MP4 players into multi-purpose teaching and learning tools to enable students to review lectures, to expand their vocabulary, and to build oral and aural skills (Facer, Abdous & Camarena, Reference Facer, Abdous and Camarena2009).

Interaction is critical in language learning. It links all the necessary conditions for successful language learning: quality input, feedback, and opportunities for practice (Gass, Reference Gass2003; Gass & Mackey, Reference Gass, Mackey, Van Patten and Williams2007). Synchronous and asynchronous media are needed to facilitate the different functions of interaction (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Lei, Yan, Tan and Lai2005), but the use of different media might be even more important in fostering the development of different language skills (Zhao, Alvarez-Torres, Smith & Tan, Reference Zhao, Alvarez-Torres, Smith and Tan2004). Oral synchronous interactions are thought to be the most effective approach for building oral proficiency, particularly for novice learners (Wang, Reference Wang2004). Frequent and timely feedback from instructors is also important in building language proficiency (Sawatpanit, Suthers & Fleming, Reference Sawatpanit, Suthers and Fleming2004; Thurmond, Wambach, Connors & Frey, Reference Thurmond, Wambach, Connors and Frey2002). Moreover, foreign language instruction should be somewhat fluid and instructors should address the linguistic problems and needs that emerge during instructional activities in a timely manner, rather than strictly follow a sequence of pedagogical tasks or learning activities (Reynard, Reference Reynard2003). Providing various types of learning activities and pedagogical tasks, assignments (e.g., individual and group; written and oral), and assessments (e.g., individual tests, group projects, oral interviews or presentations) provides variability and flexibility that enables instructors to better respond to students’ needs (Sawatpanit et al., Reference Sawatpanit, Suthers and Fleming2004).

Podcasts have generally been used as a supplemental resource (Bongey, Cizadlo & Kalnbach, Reference Bongey, Cizadlo and Kalnbach2006; Huntsberger & Stavitsky, Reference Huntsberger and Stavitsky2007) to support textbook materials (Stanley, Reference Stanley2006) and to engage students (Edirisingha and Salmon, Reference Edirisingha and Salmon2007). The most commonly reported use of podcasting has been to increase students’ preparedness and readiness for exams and to complete assignments (Copley, Reference Copley2007; Evans, Reference Evans2008). Kurtz, Fenwick and Ellsworth (Reference Kurtz, Fenwick and Ellsworth2007) report that students who received podcasts of classroom lectures for review received higher course grades than students who only listened to class lectures while in their classrooms. While these are useful benefits, additional benefits may be provided as a result of other, more innovative, uses of podcasting technology. Prior research indicates that the technology is most effective when it is thoughtfully integrated into course curricula, with a clear purpose and rationale for its instructional use (Copley, Reference Copley2007; Herrington & Kervin, Reference Herrington and Kervin2007).

Prior studies, including a recent study conducted by the authors, provide evidence that podcasting technology promotes second language learning; however, prior studies have not examined the effectiveness of different instructional uses of podcasts in language acquisition. In the light of this, this study attempts to examine the differential effectiveness of various instructional uses of podcasting in student language acquisition.

2 Background

The Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures at Old Dominion University (ODU) began podcasting in the Fall semester of 2006 as part of a project supported by a University Faculty Innovator Grant. This initial grant allowed faculty to begin to adapt podcasting technology for instructional purposes. This pilot project laid the foundation for a larger, follow-up project, supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). The NEH grant allowed more faculty members in the Foreign Language Department at ODU to develop podcasts and to use them for a variety of instructional purposes in different language courses and as data to be collected from a larger sample of classes taught during the 2007–2008 academic year.

Because of variations in course content, learning objectives, teaching styles and student language proficiency, faculty members were not limited in how they integrated podcasting technology in their courses. It was expected that they would adapt the technology both to help them achieve their course objectives and to meet their students’ needs. While the primary focus of the NEH study was to examine the effects of podcasting on second language acquisition (i.e., oral and aural skills), the initial analyses of the data collected during the Fall 2007 semester indicated that there were noteworthy differences in students’ learning that resulted from the different ways that teachers used the podcasts.

The sample of classes for this study included eight foreign language classes taught during the Fall 2007 semester. Given the relatively small number of faculty and classes participating in the study, only a limited number of comparisons could be made among the various instructional methods that faculty employed.

The study focused on the effects of the supplemental use of podcasting (Podcasts as Supplemental Material, PSM courses) and contrasted them with the integrated use of podcasting (Podcasts Integrated into Curriculum, PIC courses), comparing the instructional benefits of each method. Supplemental use is defined primarily as the unplanned use of podcasting, in which faculty members provide students with recorded lectures for later use and review. Integrated use is defined as the planned integration of podcasting into a variety of instructional activities, which include recorded critiques of student projects and exams, student video presentations, student interviews, recorded lectures, dictations, roundtable discussions, and guest lectures.

Faculty members were provided with the latest recording hardware and software and with any technical assistance needed to help them record, edit, upload, and download podcasts. All podcasts were uploaded to iTunes, enabling students to access, browse, search, subscribe, and synchronize their classes’ podcast lists. Assistance with the use of the podcasts was also provided to students.

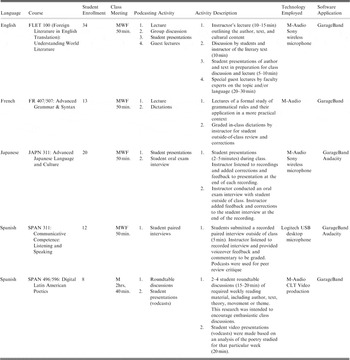

The classes that comprised the sample for the NEH podcasting study included upper level grammar and literature courses: one German, one French, one Japanese, three Spanish, and one world literature course, conducted in English (see Tables 1 and 2 for a complete list of the classes included in the study). The total enrollment for the semester in all eight classes was 128 students. The Japanese and Spanish course instructors developed podcasts of student presentations and interviews accompanied by instructor commentary and corrections. The French, German, and Spanish course instructors recorded class meetings as lectures for review. One Spanish instructor recorded student roundtable literature discussions, as well as student presentations, as vodcasts (video podcasts). The world literature instructor made podcast recordings of instructor lectures, class discussions, student presentations, and guest lectures. A detailed description of how the various instructors used podcasts for their classes is contained in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1 Classes that pedagogically integrated podcasts into their curricula (Fall 2007)

Table 2 Classes that used podcasts as supplemental material (Fall 2007)

3 Methodology

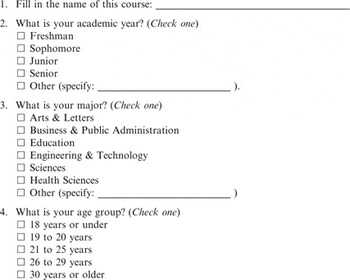

A post-test design was used: (1) to evaluate the effects of the use of podcasts for instructional purposes on student language skill acquisition; and (2) to compare the effects on student learning when the technology was integrated into the curriculum (PIC) versus when it was used as supplemental material (PSM). The study sample consisted of language classes taught by instructors who were willing to experiment with podcasts for instructional purposes. The study relied on survey and interview techniques to collect data from instructors and students. Survey data collection methods were used because of their efficiency and their simple administrative procedures.

A survey instrument (see Appendix A) developed during a pilot study was used to collect data from students. The survey included twenty multiple-choice questions about students’ academic performance; study habits; time devoted to studying and completing assignments for their language class; access to computers, iPods, and MP3 players; skills in using new technology (e.g. PCs, iPods, downloading materials from one medium to another); use of podcasts developed for their language class (i.e., frequency and ways used); perceived usefulness of the podcasts for improving language skills; and the effects of the podcasts on the students’ language skill development. In an effort to ensure that students provided honest responses, the survey was anonymous; no information that could result in the identification of a student was requested on the questionnaire.

3.1 Data collection

The student survey was administered to each student enrolled in the participating language classes at the end of the semester. With the permission of the instructors, a member of the evaluation team visited each class during the final weeks of the semester to administer the survey. Students were advised that their participation was voluntary, that the survey was anonymous, and that there would be no adverse consequences if they declined to participate. In order to ensure confidentiality, the survey forms were distributed to students at the end of class and were collected before they left the classroom.

3.2 Data analysis

Completed surveys were obtained from 113 of the students enrolled in the eight language classes that participated in the study. The survey data were compiled into an SPSS data file for analysis, and then frequency counts and per centiles were calculated. The sample of students was divided into sub-groups consisting of: (a) those enrolled in classes in which podcasts were integrated into the curricula (PIC), and (b) those enrolled in classes in which podcasts were used as supplementary material (PSM). The purpose for these comparisons was to examine potential differences in the two groups’ use of podcasting and any resulting effects on their learning and/or their acquisition of language skills. Frequency counts and per centiles were calculated for each student sub-group, so that their responses could be compared to determine whether different instructional uses of podcasts had differential effects on student learning and on their acquisition of language skills. The results of these analyses are summarized in the following section.

4 Results

Prior studies indicate that the use of academic podcasting is most effective when it is integrated into course curricula, and when podcasts are linked to specific instructional objectives (Copley, Reference Copley2007; Herrington & Kervin, Reference Herrington and Kervin2007). In a prior study, the authors found that the use of podcasts contributes to the acquisition of language skills, especially oral and aural skills (Facer, Abdous & Camarena, Reference Facer, Abdous and Camarena2009). In this study, we examined the effects of podcasting on language skill acquisition in classes in which podcasts were used for different instructional purposes (PIC vs. PSM), in order to try to determine whether there were any notable differences in learning. The analyses compared the effects of podcasting on the learning of students in foreign language classes in which podcasts were integrated into the curriculum using clear instructional objectives with the learning of students in classes in which podcasts were simply used to supplement the textbook.

4.1 Use of different devices to access podcasts

Although the technology is now relatively inexpensive, students living on limited budgets may not be able to afford to purchase an iPod or MP3 player in order to access podcasts developed for their courses. In a prior study, Facer, Abdous and Camarena (Reference Facer, Abdous and Camarena2009) found that some students used their personal computers to download and listen to podcasts. Almost all students who participated in the current study reported that they owned a personal computer (either a desktop or laptop model) and the majority (77 per cent) also owned an iPod or an MP3 player (see Table 3). Almost all students (94 per cent) reported that they used their personal computers for academic work often, while only about a third of them (31 per cent) reported that they used an iPod or MP3 player sometimes to listen to course material, and only 16 per cent used an iPod/MP3 player often for academic work (see Table 4). It appears that some students prefer to use a device which they already own (i.e., a personal computer) to download media, such as podcasts, rather than to purchase another device for use as a study tool.

Table 3 Percentage of students who own and use new devices

Table 4 Frequency of students’ use of new devices for academic purposes

Table 5 Reasons reported by students for not using podcasts

Table 6 Students’ confidence in their technical capabilities

Table 7 Frequency of students’ downloading podcasted classes to PC/iPod/MP3

Table 8 Influence of podcast availability on course enrollment decisions

Table 9 Effects of podcasts on study habits of students in PIC courses

Table 10 Effect of podcasts on study habits of students in PSM courses

Table 11 Effects of podcast use on language skills development in PIC courses

Table 12 Effects of podcast use on language skills development in PSM courses

4.2 Reasons for not using iPod/MP3 players

Thirty-five per cent of the students who were surveyed reported that they had never downloaded any of the podcasts for their language course, and an additional forty per cent reported that they had downloaded them less frequently than once a week. Students who used the podcasts less frequently than once a week were asked why they did not use the podcasts (see Table 5). The most common reason given by students was that they did not have time to download and use them. Eighteen per cent of the students who either did not use the podcasts or used them infrequently said that they did not use them because they did not think that the podcasts would help them with their studies. While only a small proportion of students (11%) reported that they did not use the podcasts because they did not know how to download them, students’ technical capabilities may have had a greater effect on their use of the podcasts than their responses to this question indicate. Students’ self-assessment of their technical skills indicated that they had much less confidence in their ability to download podcasts or to handle the interactive features of web-based instruction than they had in their ability to use personal computers for completing assignments or searching for information on the internet (see Table 6). Lack of confidence in their use of iPod technology might have affected students’ perceptions about the difficulty of downloading and using podcasts. If students thought that they would have to spend time learning how to download podcasts, in addition to downloading and using them, they may have felt that it was not worth spending the time to use them. Comments made by students in the focus groups at the end of the semester indicated that they still felt that they were not proficient in the use of podcast technology. To promote greater use of podcasts and to justify the time and costs involved in developing them, their usefulness as a learning tool will need to be made known to faculty and students. In-class training about how to subscribe, download, and save podcasts may need to be provided to students.

4.3 Frequency of podcast use by course type

Sixty-five per cent of the students who completed the survey (73 of 113 students) reported that they had downloaded the podcasts that had been developed for their language course at least once. In general, the students enrolled in the classes in which podcasting was integrated into the course curriculum (PIC classes) used the podcasts more often than those enrolled in classes in which podcasts were used simply as a supplemental resource (PSM classes). Slightly more than half of the students in the latter group reported that they had never used the podcasts (see Table 7). Twenty per cent of the students in the PIC classes reported that they had downloaded recorded class material once or twice during the semester, an additional twenty per cent reported that they had downloaded the podcasts at least once a week, and almost eight per cent reported that they had downloaded podcasts several times a week or more. In the PSM classes, only fifteen per cent of the students downloaded recorded class material once or twice during the semester. Another fifteen per cent of students in the PSM group downloaded the podcasts at least once a week, but none of the students in the PSM group reported downloading podcasts more than once a week.

A prior study (Facer, Abdous & Camarena, Reference Facer, Abdous and Camarena2009) found that students who did not own or were not familiar with iPods or MP3 players were not likely to use them, and that if students did not think that the podcasts would help them study, they would not take the time to use them. Again, many students reported that they did not use the podcasts because they did not think that they would be helpful or did not have time to download them, but those taking classes in which the instructors integrated the use of podcasts into instructional practices and classroom activities (the PIC classes) were more likely to take the time to learn how to download them and to use them than were students in the PSM classes. Almost two-thirds of the students in the PIC group reported that they would be more likely to take a language course if podcasts were available for the course (see Table 8). From students’ survey responses, it appears that if instructors take the time to carefully plan and to develop creative instructional uses for podcasts, as did the instructors of the PIC classes, their students will begin to see the podcasts’ value and will be more likely to use them. Slightly more than half of the students in the PSM classes reported that they would be more likely to take a language course if podcasts were available, which indicates that students do see some value in podcasts even if they are only used as a supplemental resource.

4.4 Effects of podcast use on learning and study habits

In addition to being asked about their use of podcasts, students were asked about how the use of podcasts had affected their study habits. Overall, a substantial number of students reported that the use of the podcasts had had positive effects on their study habits and that the podcasts had proven to be a very helpful learning tool. There were some large differences in how students enrolled in the classes in which podcasting was integrated into the course curriculum (PIC) rated the podcasts, versus how students enrolled in classes in which podcasts were just used as a supplemental study tool (PSM) rated them (see Tables 9 and 10). A larger proportion of students in PIC classes than in PSM classes reported that podcasting made learning course material, completing assignments, and obtaining instructor feedback much easier. Twice as many students in PIC classes as in PSM classes indicated that the use of podcasts made completing their assignments much easier, and 43 per cent of them reported that the use of podcasts made it much easier to get feedback from instructors, versus seven per cent of the students in the PSM classes. These findings indicate that podcasting can be an effective study tool which facilitates the completion and evaluation of assignments in foreign language classes (see Tables 11 and 12 for a complete summary of survey responses).

4.5 Effect of podcast use on acquisition of language skills

Students were asked to assess the extent to which the use of podcasts had helped them to develop their language skills. In general, the students reported that the podcasts had helped them to improve their language skills. As was found in a prior study (Facer, Abdous & Camarena, Reference Facer, Abdous and Camarena2009), students reported that the podcasts were most useful for improving their oral and aural language skills, as well as for improving their knowledge of vocabulary. (See Tables 7 and 8 for a complete summary of survey responses.) More students enrolled in the classes in which podcasting was integrated into the course curriculum gave the podcasts high ratings as useful tools – both for improving their oral and aural skills and for building their vocabulary and knowledge of grammatical rules – than did students who used podcasts simply as a supplemental study tool. A substantial proportion of students in both the PIC and PSM classes rated the podcasts highly as a useful tool for improving their aural and comprehension skills.

Another notable difference between the two groups of students was that a much larger proportion of students enrolled in the PIC classes gave the podcasts high ratings for helping them build their vocabulary and knowledge of grammatical rules than did students in the PSM classes. Ten per cent more students in PIC classes indicated that use of the podcasts improved their vocabulary than did students in the PSM classes, and almost twice as many in the PIC classes as in the PSM classes reported that the use of podcasts improved their knowledge of grammatical skills. This probably reflects the fact that their instructors used the podcasts for a variety of different instructional purposes, both in and out of the classroom. These findings indicate that, on the basis of student perceptions, podcasting can effectively promote the acquisition of a number of different language skills if instructors adapt and use the technology for a variety of instructional purposes.

5 Conclusion

Mobile Assisted Language Learning is progressively changing the way that foreign languages are taught and the way that students study. Instructors are beginning to rethink how they conduct their classes and how they use classroom time. This study shows the perceived benefits that the use of technology can provide to foreign language instructors and students. Because podcasting requires little technical support and because iPods and MP3 players are relatively inexpensive, podcasting can be a very cost-effective instructional tool. It also offers the advantage of being portable and accessible whenever needed, a factor which is important for today’s highly mobile students.

The variation that resulted from allowing instructors to decide how they would use podcast technology allowed us to examine whether this variation would result in differential effects on student learning. While this study indicates that how instructors choose to use podcast technology affects their students’ perceived learning gains, more rigorously designed studies which control how instructors use the technology are needed, in order to determine whether the differential effects are significant and to identify which instructional uses produce the largest learning gains.

As research begins to document the instructional benefits of podcasting, the initial reluctance of instructors to use this new technology should continue to decline. More and more instructional uses will be found for this technology as instructors begin to experiment with its use. Follow-up studies, which will examine the use of podcasting as a tool to help students prepare for and enrich their Study Abroad experience, are already being planned. Additionally, further studies examining the impact of podcasting and mobile devices on student learning styles should be beneficial. With recent US Federal initiatives that have provided funding for university projects designed to adapt iPods, MP3 players, cell phones, and PDAs for instructional uses, it is likely that these technologies will eventually be incorporated into classes in all academic departments at colleges and universities.

Appendix A: ODU Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures Student Survey about Podcasting Use Fall 2007 & Spring 2008

INSTRUCTIONS

Faculty in ODU’s Foreign Languages and Literatures Department are beginning to experiment with the use of iPods, MP3 players, and podcasting in foreign language courses. You can help them learn more about the use of these new tools and technologies for instructional purposes in college classrooms by completing this survey. Your participation is voluntary and your course grade will not be affected if you do not participate in the survey.

In addition to requesting your participation in this survey, we would like to obtain your final grade for this course and your oral proficiency score from the course instructor. Student grades and oral proficiency scores will be used to evaluate the effects of podcasting on academic performance. If you complete this survey, it will be assumed that you agree to let us obtain this information from the instructor. All of the performance data provided by your instructor will remain confidential.

The information you provide will remain confidential. Your individual responses WILL NOT be shared with the instructor of this course or anyone in the Foreign Language Department. The survey responses of students will be aggregated and only a summary of all survey responses will be reported. The results of the survey will be used only for research purposes to determine whether podcasting is an effective method of promoting language learning among college students.

Please provide as accurate an answer as possible to each question. If there is a question that you do not know the answer to or do not wish to answer, skip it and go on to the next question.

THANK YOU FOR COMPLETING THE SURVEY.

PLEASE RETURN IT AS INSTRUCTED.