1 Introduction

The question of the development of online pedagogical tools in blended learning devices to guide students through off-site aural and written tasks is a problematic one. If problems are indeed noticed in the students’ online work which is emailed to the tutor(s), information as to how this work is actually carried out, what tools are used and what language needs are required by them whilst doing their tasks constitutes a “grey area”. The latter therefore needs investigation, so as to determine what could be set up in terms of online tools that take into account the students’ needs and bring about a qualitative progression in their L2 learning process.

1.1 Pedagogical context

To do so, action research was carried out in 2007–2008 at the University of Perpignan amongst 59 heterogeneous B1/B2 ESP students (Brudermann in press). Those students were would-be primary school teachers, hence a very specific pedagogical context, as in the French system these students are required to take a competitive examination (concours de recrutement) which includes both written and oral subjects, before entering teacher training units (Instituts Universitaires de Formation des Maîtres) and becoming primary school teachers.

For each subject, there are official instructions providing guidelines and, for English, it is stated that this examination is an oral one, that there is no particular programme, that the candidates have to make a five-minute presentation of a 20-line B2-level text, whose “content must be sufficiently rich” (e.g. a press article or a novel extract). Then, there is a reading part in which the candidates are asked to read aloud a passage from the text, followed by a ten-minute interview with examiners asking questions about the main themes of the text, the cultural facts it includes and potentially ethical questions. The official instructions also recommend that the examiners should pay special attention to the phonological quality of the candidates’ L2 in the evaluation process.

1.2 Pedagogical engineering

At a pedagogical level, this examination requires preparation of various language skills, with a particular emphasis on written and aural comprehension, oral production, cultural knowledge, ethics, and phonology. The university had set up a 35-hour English module for the whole year and the students enrolled for this examination preparation programme were a very heterogeneous population; the only pre-requisite for them was to hold at least a three-year undergraduate degree in any subject, hence there was a discrepancy between those formerly engaged in linguistic programmes and those coming from non-linguistic programmes.

Moreover, the English module did not result in any grade or degree, the objective of the would-be primary school teachers’ programme being that the students pass the competitive examinations. In point of fact, all the activities within the programme were to be carried out on a voluntary basis.

In line with several studies (Narcy-Combes & Narcy-Combes, Reference Narcy-Combes and Narcy-Combes2007; Pernin & Godinet, 2008), a blended learning device had consequently been set up as a means to deal with heterogeneous groups by promoting individual learning paths in which everyone is able to work according to their own needs.

1.3 Pedagogical device

An environment open to a diversification of learning strategies for the students and to various forms of help was thus set up. As shown in Figure 1, it relied on different workshops geared towards work according to varied strategies. The dotted line marks for instance the separation between online and onsite work and the solid line indicates the separation between individual and collective work. The idea here was to try and trigger off a virtuous circle of acquisition, thereby promoting L2 acquisition.Footnote 2

Fig. 1 Blended learning device set up in Perpignan.

This environment also allowed students to go through examination simulations thanks to a system of macro tasks that had to be done online and individually, whereby they had to select a document, namely a press article or an extract from a novel, and to provide a presentation of it either in writing or orally.

They could also use an online resource centre which had been created to provide them with various types of help in different language skills.Footnote 3 They next had to email their productions to their tutor who gave them in return correction sheets complete with explanations related to their needs and with a list of links to micro tasks (Narcy-Combes, Reference Narcy-Combes2005; Guichon, Reference Guichon2006) for further practice on their particular needs. At this stage, students were free to do the exercises or not.

The hypothesis was that this system of macro and micro tasks would favour noticing and rehearsal in the students’ working memory and further storage in their long term memory (Baddeley, Reference Baddeley1995).

1.4 Action research

Action research was carried out to look into those 59 would-be teachers’ needs when performing off-site aural and written tasks. Four tasks had to be done online on a voluntary basis over a period of four months. The corpus of completed student work collected amounted to 185 tasks, among which 144 (77.8%) were written tasks and 41 were oral tasks (22.2%). An analysis of the problems encountered by the students in their productions highlighted a few facts, and some conclusions on the online mediation proposed in this pedagogical device were drawn.

To begin with, an analysis of the problems encountered in the 185 tasks was carried out. It highlighted 787 erroneous productions, all deriving from the same specific problematic points. It thus turned out that a typology of 43 types of problems emerged, including for instance the use of the article “the” or the reference to past events. In turn, those 43 types of problem could be classified into four macro categories, as shown in Table 1:

Table 1 Breakdown of the typology by macro categories

A further study also revealed that 80 percent of all the problems accounted for in the typology were due to sixteen problems (out of the 43 it includes). An analysis of the data collected next showed that most of those obstacles derived from A2/B1 elements that French university students are meant to have already been taught during their secondary education.Footnote 4

Next, it appeared that 40% (316/787 × 100) of the students’ needs could not be catered for by online tutoring, since some problems reappeared from one production to another, between 2 and 4 times in a row of four expected tasks, as shown in Table 2:

Table 2 Frequency of reappearing problems

Eventually, thanks to a counter set up on the online resource centre, data concerning the traffic on this website were collected. On average, it turned out that, for each task, the connection rate per student amounted to 1.7 both for the elaboration and correction phases. This revealed that, in line with other studies (Cárdenas-Claros & Gruba, Reference Cárdenas-Claros and Gruba2009; Fischer, Reference Fischer2007) the students rarely took advantage of resources in CALL as they did not log onto them at each stage. Furthermore, the results of an anonymous questionnaire confirmed that the students hardly ever did the online exercises proposed in the correction sheets. Therefore, the use of this system did not permit the measurement of any qualitative progression in the solving of recurring problems, even though the study revealed that the more tasks were completed, the more accurate and fluent the students’ productions became. This move towards a quantitative change therefore seemed to match Benoit’s results (Reference Benoit2004).

2 Readjustment

Those conclusions further led us to readjust the initial pedagogical device (Fig. 1) and to bring new hypotheses to the fore, so as to try and promote qualitative changes in the students’ productions:

(1) Providing students with relevant items and links when needed whilst doing tasks would help them reinvest and reflect upon their FL knowledge (Van Harmelen, Reference Van Harmelen2006);

(2) Replacing the correction phase by a system of asynchronous distance recasts would trigger off potential learning sequences (De Pietro, Matthey & Py, Reference De Pietro, Matthey and Py1989);

(3) Asking students to correct themselves and justify their answers regarding erroneous productions would favour rehearsal in their working memory and further storage in their long term memory (Baddeley, Reference Baddeley1995);

(4) All the EFL gains could be further reemployed in onsite and distance activities;

(5) The incorporation of all these new features in a blended learning device would help take everyone’s needs into account.

2.1 Customization of a website

As the previous study showed that the same problems appeared again and again, a websiteFootnote 5 incorporating forms of help adjusted to the typology was then designed. It functions as an automatized online teacher, hence the name “assistant” and it was designed to serve as a guide through the development of the students’ work and to raise their awareness about a certain number of aspects they are normally already acquainted with but which they nonetheless tend to forget when producing in L2. Its purpose is to have the students work out a certain number of problems by themselves before emailing their productions, since they have to deal with the typology of problematic points they are already familiar with. As the previous study had shown that the students were not comfortable with having a set of online links where they could find further help or exercises (Cárdenas-Claros & Gruba, Reference Cárdenas-Claros and Gruba2009; Fischer, Reference Fischer2007), the idea was to provide them with a concentration of all the relevant information according to their needs, in one single “closed-in” cyberspace. This system was designed for the completion of the same tasks as those which had been proposed to the would-be ESP teachers. In order to push students into committing themselves to their L2 learning process and have them evolve in a non threatening environment, the online tasks are not meant to be graded, so as to promote L2 practice only.

2.2.1 Organization of the website

This cyberspace has also been organised so as to have the students find the information they are looking for in a few clicks. To do so, as the problematic points from the typology derived both from written and oral needs, two main sections were first set up in the website, allowing the provision of specific forms of help, according to the type of work the students are led to choose on the main page of the website, as shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2 Main page of the pedagogical assistant.

One of the advantages of this type of presentation is that the web pages are less “crammed” and therefore less liable to discourage the students in their exploration of the website due to a cognitive overload of information and/or a potential disorientation of the learners when that is the case (Rouet, Reference Rouet2000).

The online resource centre from the previous study was redesigned, split into different sections and incorporated into the assistant in order to enable better scanning of the information (see Figure 3). That is why, instead of a listing in which they had to look up the required information, the students now have to click on a category and then find within this category more specific links to what they are looking for. The web pages are therefore shorter, clearer and highlight their content better.

Fig. 3 “New” design of the online resource centre.

2.2.2 Organization of the information

In order to help the students take care of problems from the typology by themselves, the information has been organized in such a way as to be accessible in “real time”, that is to say at the moment when help on a particular point is required. The previous study had shown that if the information was not made available immediately and easily to the students, they made no particular effort to try and seek help, either online or in books, often ending up with erroneous productions in their work.

The various forms of help incorporated into the assistant have been sorted out and organized so as to be found at the moment when needed. This necessarily entails working alongside the website when doing online tasks and, to push them into doing so, field experience reveals that an onsite session is required to make them aware of how to use the website and work with it.

The underlying principle is that according to the type of work the students have chosen to do, they are invited to follow an “online marked trail”, taking them from one end to the other of their tasks, that is from the “instruction” section to the “re-reading” or “re-listening” phases, which implies a certain number of phases. For each task, a separate sub-page was set up for the students to follow the various steps suggested (see Figure 4).

Fig. 4 Main page of the “oral task” section.

As the students progress with their productions, instantly accessible forms of help are hence provided according to the phase they are in. In addition, to help students be autonomous in their manipulation of the free open source recording software Audacity, online screen shots and other devices were incorporated to take into account some potentially confusing technical aspects (see Figure 5).

Fig. 5 Online tutorials on technical aspects.

2.3 Pedagogical assistant and online help

The organisation of the online help relies heavily on the typology of problems. Thus the purpose of the website is to propose a classified repertoire of online tutorials in line with learners’ needs and allow access to them at “strategic” moments, that is when needed, so as to operate as a “mistake sieve” for students. The various problematic points included in the four categories of problems were therefore considered in the assistant by highlighting tutorials required to solve them. As the needs varied according to the type of task chosen by the students, two main sections were set up for “written” and “oral” tasks. Morphosyntactic tutorials were arranged both for written and oral tasks, while a phonological module was added to the phonological task section. The various forms of help were designed to be used whilst doing a task.

2.3.1 Written tasks and online help

As far as written tasks are concerned, the main page of the “written task” section was designed to represent a virtual sheet of paper, notably because some problems of the typology are linked with certain sections of students’ productions. This was done deliberately to induce the students to find a tutorial at the moment when a particular type of help is required by them. For instance, the previous study had shown that date-related problems were more likely to be found in the introductory part where students are attempting to introduce the document they want to deal with. So, the help section related to dates has now been set up in the introduction section of the virtual sheet of paper (see Figure 6).

Fig. 6 Written task section and its virtual sheet of paper.

Again, since the majority of problems in the typology were part of the morphosyntactic macro category, they were gathered and sorted into sub groups in the assistant, more for the sake of clarity, to present a “non threatening” environmentFootnote 6 and encourage students to click on the appropriate links (see Figure 6).

The sub groups are: the use of verbal forms, miscellaneous grammatical points and an «agreement» section. Examples have also been provided within brackets for more guidance; they have been selected from the most numerous problems (in terms of rates of error), as indicated by the previous study.

An English dictionary has also been provided to allow students to look up words that they do not know or which they are unsure of. For each problematic point tackled by the assistant, anonymous examples taken from students’ productions are given, to confront them with possible “traps” they are liable to fall into and enable them to get round these and put forward other hypotheses, in accordance with their interlanguage (Selinker, Reference Selinker1972).

In line with the concept of affordance (Gibson, Reference Gibson1977), the assistant takes into account the learners’ needs and provides possible solutions designed to enable them to solve their own problems. Moreover, in line with Spear and Mocker (Reference Spear and Mocker1984), for whom “self-directed learning occurs as a direct result of the organizing circumstance of the environment within which the learner is located” (Redding, Reference Redding2001) it allows individuals to respond to the environment and to determine personal learning paths.

2.3.2 Oral tasks and online help

For oral tasks, a three step path has been designed so as to potentially lead the students to take into account for themselves all the problems related to oral productions highlighted in the previous study.

The first tutorial aims to encourage the students to simplify their vocabulary, use linking words, be synthetic and work with prompts instead of reading their notes out loud. The second module comprises the same morphosyntactic tutorials as those proposed in the written task section, though the information is displayed differently.

The third module deals with phonological tutorials targeting a certain number of recurring problems (see Figure 7). Depending on the problematic point tackled, explanations, phonological diagrams, tongue twisters, links to online audio files or to text to speech websites are provided, for the students to practise and improve their aural skills.

Fig. 7 Oral task section and online phonological tutorials.

As “one feels like a different person when speaking a second language and often indeed acts very differently as well” (Guiora & Acton, Reference Guiora and Acton1979: 199), which is thus liable to produce existential anxiety amongst learners (Rardin in Young Reference Young1992), the aim of the online assistant is to help the learners overcome their feeling of being “blocked up” when using an L2, and alleviate inhibition in L2 by, again, allowing them to evolve in a non-threatening learning environment.

The previous study had shown that a minor proportion of 22.2% of the tasks had been oral ones, whereas personal questionnaires filled in at the beginning of the year had revealed that more than 90% of those 59 students thought that they mostly had oral needs, hence a paradoxical situation.

Another aim of the assistant is therefore to lead the students to go beyond the frontiers of their language-ego permeability (Guiora & Acton, Reference Guiora and Acton1979), and invite them to do more oral tasks.

2.3.3 Re-reading and re-listening phases

In order not to overload the students with information, other sections were designed, to be used in a post-task phase with a view to taking into account methodological problems and those deriving from the influence of L1 on L2. Action research had shown that the students did not often re-read their productions and hardly ever listened again to their oral ones, which caused a certain number of lexical and methodological problems. Post-task tutorials with specific forms of help for this phase were therefore arranged for the students to refer to before submitting their productions (see Figure 8).

Fig. 8 Rereading and re-listening phases of the online assistant.

Again, the links from those sections were designed to match the needs highlighted in the previous study and were classified according to the frequency of their reoccurrence and importance (in terms of rates of error).

3 Online tutoring

In order to promote a qualitative progression in the students’ L2 interlanguage, a tutoring system was devised, “tailored” to provide a backup for the elements not taken care of by the students themselves during the production phase of their tasks; the intention was that the students would reflect on their productions in a final correction phase. Indeed, the previous study had shown that when the tutor was in charge of the correction, not only was there virtually no qualitative progression, but also some problems reoccurred, up to four times in a row, out of four expected tasks (see Table 2).

The purpose of the “new” correction system is no longer for the tutor to correct the students’ productions but to help them proceed to self corrections.

This tutoring system therefore implies that students are now encouraged to take into account as many problems from the typology as they can before submitting their tasks because, being from now on also in charge of their corrections, they will have to focus on them in the correction phase. To put into practice this online tutoring, a system of correction codes was developed to highlight the problems and to specify their category (see Table 3).

Table 3 Correction codes for online guiding

As far as written tasks are concerned, those correction codes can be directly inserted into the students’ productions, as shown in Figure 9.

Fig. 9 The use of correction codes in written tasks.

For oral tasks, the free open source software Audacity is used, particularly because it offers the option of inserting markers on the recorded track and also because some elements can be written by the markers, as shown in Figure 10, and those options can therefore be used for correcting purposes.

Fig. 10 The use of correction codes in oral tasks.

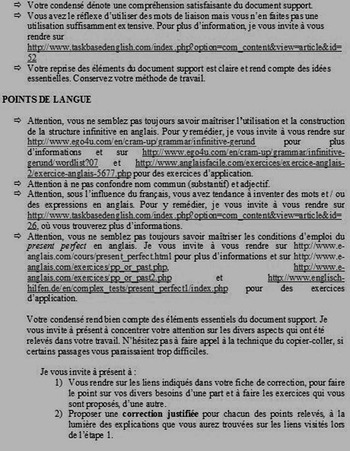

The documents with the correction codes are then emailed to the students who are expected to correct their mistakes. To do so, and to have them reflect on the problems encountered, they are also given a correction sheet providing a listing of all the problems which emerged in their productions and, for each bullet point, links to online help and exercises to meet their needs, as shown in Figure 11.

Fig. 11 Correction sheet provided to the learners.

3.1 The development of correction sheets

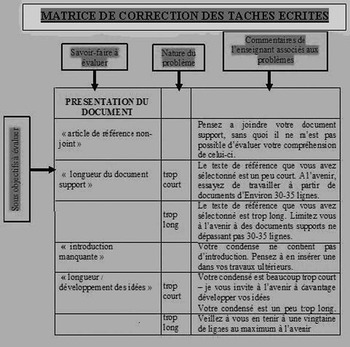

Since action research had shown that a fixed typology of problems always reappeared, it has been possible to develop matrices of correction from it for each type of task and to bring forward a system of semi-automatic correction whereby the tutor can copy and paste automatic comments from the correction sheet directly onto the students’ correction sheets.

As shown in Figure 12, the matrices were designed to take into account all the problems from the typology.

Fig. 12 Organisation of the matrices.

The various problematic points to evaluate have been inserted in the left hand column for a quicker visualisation and the middle column is there for the tutor to select the nature of the problem. For instance, the problematic point “reference to the past” can cover either problems linked to the conditions of use of the preterit or to problems deriving from an unsatisfactory manipulation of irregular verbs. After having located the relevant point that the tutor wishes to point out to his/her students, s/he then has to copy and paste the automatic comments to be found in the third column onto the students’ correction sheets (see Figure 11). Those comments are meant to highlight the problem (s) encountered and to further direct the students to relevant online help and exercises in accordance with the problems underlined in the students’ productions.

3.2 Tutoring and self-correction

It appears, thanks to those listings, that the correction phase is no longer, strictly speaking, a correction for the students, but it has more to do with a matching exercise between the bullet points provided and the problems highlighted. As a result, the correction phase now functions as a system of asynchronous recasts which, in accordance with the new hypotheses put forward, encourages noticing and rehearsal in the students’ working memory, notably because rehearsal and further storage in long term memory (LTM) are related (Ellis & Sinclair, Reference Ellis and Sinclair1996). This implies deep processing, as, according to Craik and Lockhart (Reference Craik and Lockhart1972), items which are processed “deeper” are consolidated into LTM.

At a pedagogical level, to trigger off a cognitive activity the students are next required to propose, for each problem, some form of correction and to justify their proposals; more particularly, to browse the web links provided and do the recommended exercises (see Figure 13).

Fig. 13 Example of a student’s correction.

Once this part has been done, students are next required to email their self corrections, and the second step for the tutor at that point is to agree or not with what has been proposed by the students, using a tick or a cross respectively. It is only at this point that the tutor provides the answer which was expected in the first place (see Figure 14).

Fig. 14 Example of a tutor-supervised student’s correction.

As far as the correction of oral tasks is concerned, it can either be carried out in a written form or it can be recorded. Again, a correction code can be used, as shown in Figure 15, to indicate whether the correction proposal is satisfactory or not.

Fig. 15 Example of a tutor-supervised student’s correction of an oral task.

It is only at this point that the workload expected for the completion of one task is finalized.

4 First results and perspectives

A blended learning device incorporating this application has now been implemented for six months at the University UPMC – Paris VI and action research is currently in progress.

The first results seem to reveal that when working alongside the pedagogical assistant, the rates of the most problematic points from the typology (manipulation of aspectual forms, reference to the past, noun agreements, use of the article “the”) are progressively going down as the number of tasks progresses. For example, problems related to the use of the article “the” have decreased by 86% after four tasks. Similarly, the number of non-attested forms of B2/C1 isolated problems not taken care of by the typology is continuously increasing, with a 56% rise between tasks 1 and 4. It therefore seems that the use of the assistant engenders a cognitive activity as it has students put forward new hypotheses in accordance with their interlanguage.

The system of directive tutoring relies on the students’ autonomy and their commitment to their learning processes. Practice from the field and monitoring of the students’ use of the website both reveal that the correction phase, which is the moment when they need to look for help, do exercises and when cognitive activity and conceptualization is engendered, is taken seriously. Post-tests have also shown that, after a 24-hour module of L2 which includes the completion of four online tasks, this progression is still fragile since, when working onsite without the assistant, the overall number of problems from the typology goes up again by about a third.

Furthermore, students claim that they have become more confident with written tasks thanks to this pedagogical device, even if they actually still tend to avoid doing aural tasks. The students’ satisfaction over the way the English class is run is high and they acknowledge they have made progress. As it is, the insertion of the assistant into a blended learning device seems to constitute a valid alternative for B1/B2 ESP students, insofar as traces of a qualitative progression in L2 are emerging. However, within the framework of this study, a 24-hour module does not seem to be enough to foster stability in the acquisition process.