1 Introduction

Because of the potential of social media to foster collaboration and enhance language skills, tools such as wikis, blogs, and Facebook have been increasingly integrated in foreign language (FL) classrooms. Recently, new editing software has allowed learners to create digital stories (DSs): story lines that integrate text, images, and sounds in an online environment. This allows learners to share their voices and views in an open and interactive environment (Gregori-Signes, Reference Gregori-Signes2008; Ohler, Reference Ohler2008; Sadik, Reference Sadik2008) and to integrate traditional writing skills and the latest digital media (Oskoz & Elola, Reference Oskoz and Elola2014) into multimodal texts (Porto & Alonso Belmonte, Reference Porto and Alonso Belmonte2014). Due to their potential value for second language (L2) writing development, DSs have been used in English as a second language (ESL) studies (Rance-Roney, Reference Rance-Roney2008; Vinogradova, Linville & Bickel, Reference Vinogradova, Linville and Bickel2011), in heritage speaker settings (Vinogradova, Reference Vinogradova2014), and in FL classrooms (Alcantud-Díaz, Reference Alcantud Díaz2010; Castañeda, Reference Castañeda2013; Gregori-Signes, Reference Gregori-Signes2008; Oskoz & Elola, Reference Oskoz and Elola2014; Yang, Reference Yang2012). However, little is known about learners’ use of rhetorical and linguistic features (e.g. selecting meaningful topics, developing a story line, organizing ideas coherently, and maintaining linguistic accuracy) together with non-linguistic components (e.g. sound, images) to create multimodal texts.

Given the omnipresence of multimodality in society, education, and our personal lives, language educators can benefit from insights into how learners acquire knowledge in a multimodal medium. Following a social semiotic multimodal approach (Kress, Reference Kress2003, Reference Kress2009) and activity theory (Leontiev, Reference Leontiev1978), this study focuses on learners’ perceptions of the production of DSs in an advanced Spanish writing course by exploring: (1) how the characteristics of the tools and artifacts used to create DSs mediate Spanish learners’ understanding of the final product, (2) how Spanish learners used tools and artifacts such as image, sound, and software editing to move from goal-oriented short-term actions to long-term object-oriented activity, and (3) how Spanish learners negotiated and reoriented their linguistic requirements to suit the characteristics of DSs.

2 Literature review and theoretical framework

2.1 DSs in the FL classroom

The burgeoning number of studies on the use of DSs for instructional purposes in ESL education, in heritage speaker settings, and in FL education, attests to the increasing relevance of this activity for the FL curriculum. From a pedagogical perspective, DSs offer two major benefits: first, they provide learners who have difficulties writing traditional texts with an alternative form of expression (Reid, Parker & Burn, Reference Reid, Parker and Burn2002); second, because of the way they integrate text, sound, and images, DSs allow learners to produce multimodal artifacts that strongly resemble the media products they encounter in their everyday lives (Haffner & Miller, Reference Haffner and Miller2011).

The visual and audio components of DSs have an obvious appeal, especially to a younger generation of learners, but we must not forget the “deep language acquisition and meaningful practice” (Rance-Roney, Reference Rance-Roney2008: 29) which has also been ascribed to this genre. As Robin (Reference Robin2007) suggests, selecting a meaningful topic and then writing a story about it are the two key elements of the digital storytelling process. During the development phase, learners write creatively, organize their thoughts coherently, and construct their own narratives (Gakhar & Thompson, Reference Gakhar and Thompson2007; Robin, Reference Robin2006). Researchers have found that the DS genre encourages learners to pay attention to grammatical rules (Reyes Torres, Pich Ponce & García Pastor, Reference Reyes Torres, Pich Ponce and García Pastor2012) just as much as traditional academic writing does (Oskoz & Elola, Reference Oskoz and Elola2014).

Mastering the DS genre, however, brings additional challenges. Learners who are familiar with traditional forms of academic writing (e.g. argumentative and expository essays), which require the collation of facts in an objective manner, might need several attempts to reproduce the more personal nature of a DS (Oskoz & Elola, Reference Oskoz and Elola2014). In the process of creating DSs, learners become aware of the oral nature of storytelling via a script, and they learn to include appropriate stylistic devices to suit the narrative flow (Gregori-Signes, Reference Gregori-Signes2008; Oskoz & Elola, Reference Oskoz and Elola2014). Porter points out that “unlike traditional oral or written stories, images, sound, and music [are] used to show a part of the context, create setting, give story information, and provide emotional meaning not provided by words.” (Porter, n.Reference Porterd.: para. 6). The inclusion of sound and images as an integral part of a story is grounded in the framework of synesthesia (Kress, Reference Kress2003): “the emergent creation of qualitatively new forms of meaning as a result of ‘shifting’ ideas across semiotic modes” (Porter: 36). The intermeshing and interaction of these modes is further enhanced by the brevity of the digital story, which should last no more than three to five minutes, based on a written script of no more than five hundred words (Davidson & Porter, Reference Davidson and Porter2005; Lambert, Reference Lambert2002). This compact time frame obviously influences writers’ decisions about the inclusion and function of all images, sound, and text.

2.2 Transformation and transduction

A social semiotic multimodal approach (Kress, Reference Kress2003, Reference Kress2009) that focuses on the sign-maker and his or her situated use of modal resources informs how language learners proceed when composing a DS (Yang, Reference Yang2012). According to Kress (Reference Kress2010), when producing a multimodal text, authors are involved in a multimodal process in which they make use of semiotic resources and where several types of modes (e.g. written, oral, music, and images) are used. In the language classroom, learners are urged “to serve as active designers, shaping and reshaping ways of presenting messages by utilizing and mingling semiotic resources for their potential with a focus on the intended meanings to be delivered” (Yang, Reference Yang2012: 223). Transformation (the actions that reorder and reposition semiotic resources within a mode) and transduction (the reorganization of semiotic resources across modes) are pivotal actions when designing a multimodal text (Kress, Reference Kress2003, Reference Kress2009). Within the development of DSs, for example, transformation is evident in the process of reconstructing a narrative story into a DS script, or reconstructing the syntax or structural complexity of sentences with the objective of creating new meanings. Transduction, for instance, involves shifting written narration into spoken language and incorporating images, music, and sound.

Yet, neither transformation nor transduction is easy to achieve in the FL classroom. For example, Nelson’s (Reference Nelson2006) learner had difficulty understanding how semiotic resources might be altered to convey specific meanings. However, Porto and Alonso Belmonte’s (Reference Porto and Alonso Belmonte2014) digital storytellers’ use of images as meaning intensifiers helped them to produce compelling multimodal metaphors. In Yang’s (Reference Yang2012) study, participants’ practice of transformation in the speech mode (tone, stress, intonation), the image mode (color, lines), and the audio mode (tempos, rhythms, melodies), and participants’ practice of transduction, allowed them to achieve their intended meaning. Therefore, when developing DSs in the FL classroom, learners need to understand (a) how the integrated design elements of multimodal texts communicate meaning beyond the simple sum of their parts (Kress & van Leeuwen, Reference Kress and van Leeuwen2006), and (b) how to integrate non-linguistic modes effectively to complement the central message – and not just use them as supplementary resources (Shin & Cimasko, Reference Shin and Cimasko2008) or as compensation for the learner’s own linguistic deficiencies (McGinnis, Goodstein-Stolzenberg & Saliani, Reference McGinnis, Goodstein-Stolzenberg and Saliani2007).

2.3 Artifacts, objects, and goals

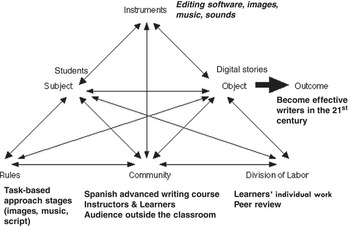

Developed by Leontiev (Reference Leontiev1978), activity theory (AT) considers that an activity “is a form of doing directed to an object” (Kuutti, Reference Kuutti1996: 14) and that individual actions, classified as automatic processes or operations (unconscious acts), and conscious processes or orientations (planned actions directed to the achievement of an immediate and defined goal) always take place in a minimal meaningful context that “must be included in the basic unit of analysis” (Kuutti, Reference Kuutti1996: 26). Actions occur within a collective system (see Figure 1) and are mediated firstly by tools and artifacts (e.g. computers, languages, and tasks), and secondly by “social mediators” (Engeström, Reference Engeström2008: 27), which includes the community (e.g. the L2 classroom and its potential audience) with its understood rules (e.g. task-based approach), and the division of labor in those community settings (e.g. peer feedback).

Fig. 1 AT in the FL writing classroom (from Engeström, Reference Engeström1987)

AT, which recognizes the dynamic nature of the interrelationship between the components of an activity system as a whole, also considers tools and artifacts to be “integral and inseparable components of human functioning” (Engeström, Reference Engeström1999: 29). According to Kuutti (Reference Kuutti1996), an activity contains various artifacts whose essential feature “is that they have a mediating role” (13). An instrument, therefore, “mediates between an actor and the object of doing” (Kuutti, Reference Kuutti1996: 13) and “changes in the design of a tool may influence a subject’s orientation toward an object” (Basharina, Reference Basharina2007: 85). When introducing a change in an established activity system, such as a new tool in an L2 writing class, contradictions – tensions between two or more components of the system (Engeström, Reference Engeström2008) – may emerge. Rather than being the cause of conflict, contradictions trigger a transformation of the activity system and can be critical to “innovative attempts to change activity” (Engeström, Reference Engeström2001: 137). This transformation entails (a) reflective analysis of the existing activity structure, (b) reflective appropriation of existing culturally advanced models and tools, and (c) individual innovation as a result of critical self-reflection (Engeström, Reference Engeström1999).

Given that the selection and use of tools are not neutral actions, they can shape the mediation process between the actor and the object that is acted upon (Kuutti, Reference Kuutti1996; Wertsch, Reference Wertsch1991) and can have an impact on language development (Hampel & Hauck, Reference Hampel and Hauck2006; Thorne, Reference Thorne2003). Because the object is seen and manipulated within the limitations set by the instrument (Engeström, Reference Engeström1991), tools are both enabling and limiting: they can direct the learner toward a desired outcome but also restrict his or her actions (Kaptelinin, Kuutti & Bannon, Reference Kaptelinin, Kuutti and Bannon1995; Kuutti, Reference Kuutti1996). At the same time, because an activity system is dynamic, the object and motive themselves can change in the process of activity (Kuutti, Reference Kuutti1996). Blin and Appel (Reference Blin and Appel2011), for example, found that learners deviated from expected procedures in applying the tools and developing an object, and in the Oskoz & Elola’s Reference Oskoz and Elola2014 study, learners’ interactions with tools and artifacts mediated their evolving perceptions of the object and helped them to focus on different aspects of DSs in a sophisticated way. Therefore, although learners share the same object, how they carry it out will differ depending on their selection, interpretation, and use of the available tools and artifacts.

When developing the DS narrative, learners’ selection, understanding, and use of artifacts such as images and sounds influence the way they envision the objects and how they develop them (Oskoz & Elola, Reference Oskoz and Elola2014). An important aspect of artifacts is “that [they carry] significant information across time and space and that [they] serve, through local interpretation, to create coherences between distal events” (Lemke, Reference Lemke2001: 21), linking long-term processes to short-term events (Blin & Appel, Reference Blin and Appel2011). Artifacts connect longer-term object-oriented activity, such as the construction of a digital story, and shorter-term individual or collaborative goal-oriented actions or chains of actions directed toward a goal (Kaptelinin et al., Reference Kaptelinin, Kuutti and Bannon1995), such as writing a text, selecting images, or editing language. For example, Oskoz & Elola (Reference Oskoz and Elola2014) found that dividing various writing components and processes into manageable tasks allowed learners to focus on short-term goal-oriented actions, such as selecting images, integrating sounds, revising drafts, or thinking about a topic, while maintaining focus on the long-term object-oriented activity: the completion of their DSs.

Although the educational use of DSs in the classroom is becoming widespread and popular, little is known about Spanish learners’ perceptions when interacting with genres that include multimodal semiotic resources. Therefore, this study seeks to answer the following questions:

-

1. How is learners’ understanding of the object (DSs) mediated by available tools and artifacts?

-

2. How do learners perceive the use of tools and artifacts as they move from goal-oriented short-term actions to long-term object-oriented activity?

-

3. What linguistic reorientation takes place when learners move from academic writing to the creation of DSs?

3 Methodology

3.1 Participants and setting

The study was conducted at a mid-sized university on the US east coast. The participants, whose ages ranged from 19 to 21, were six Spanish majors enrolled in a fourth-year Spanish writing course. This was a three-credit one-hour capstone course of the program and mandatory for all Spanish majors. The class met one evening a week for two-and-a-half hours. The instructor wanted to expose learners to the potential educational benefits of DSs, and to explore the ways in which the learners used linguistic, visual, audio, and spatial modes of representation and synthesized those distinct modes to form an integrated multimodal text.

3.2 Procedure

To ensure that learners could create a multimodal text, the instructor designed a task-based approach, in which an overall task was broken down into several interrelated steps (Samuda & Bygate, Reference Samuda and Bygate2008) to make the task more manageable. Following this model, the development of DSs was structured in six phases over the course of one semester (see Table 1).

-

∙ Phases 1 to 3: During the first ten weeks of class, learners developed two argumentative and two expository essays introducing the content that would form the basis for the DSs (i.e. a character in the Latino world, the relevance of the Latino vote in the US elections, the Dream Act). As part of this process, they searched for images that reflected the content of their essays (Phase 1). Images were evaluated in class in terms of their level of explicitness (literal reflection of the object presented) or implicitness (indirect relationship with the object presented) and assessed for their values or messages. In addition, learners with the help of the instructor in class viewed sample DSs and commented on how well the authors had integrated images, text, and sound within the digital storytelling genre (Phase 2). In Phase 3, learners selected their topics and reassessed their previously selected images, searching for new ones and discarding others. Learners also started to select accompanying music for their DSs.

-

∙ Phase 4: Learners finalized the first draft of their narratives and received initial training on the use of Final Cut, the chosen editing software, in the language lab.

-

∙ Phase 5: Learners received feedback from the instructor on the content, structure, and form of their narratives prior to converting them into DS scripts of approximately 500 words, five minutes long. Learners also worked on the non-linguistic components of their DSs. In class, learners shared their narratives in small groups. Reading their scripts aloud to their classmates provided an opportunity to discuss and receive feedback on content, structure, and organization, and on the kinds of images to include in the final DSs and to consider the emotions that the script and the pace of its reading might evoke in listeners.

-

∙ Phase 6: Learners completed their DSs and presented them to the class.

Table 1 Phases of DSs and data collection procedures

3.3 Data collection

For the purpose of this study, the unit of analysis was the activity system corresponding to the development of DSs in an advanced Spanish writing class. The data for this study consisted of (a) three online journal entries in which learners explained in Spanish how they created their scripts and selected and used images and sound to support them; (b) learner’s concluding reflections in Spanish on their creative processes, including their writing approach, selection of images and sound, collaboration with classmates, and use of instructor’s and classmates’ feedback; and (c) an English questionnaire (see Appendix) at the end of the semester targeting various factors presented in the AT framework, such as how the use of instruments (images, sound, text) influenced learners’ DSs and their sense of community (audience), and how their perception of the development of the object (DSs) evolved during the process. These sources were used to triangulate the data. The researchers analyzed them using a content analysis method reflecting the objectives of the research (Merriam, Reference Merriam2009). To ensure the anonymity of all participants, pseudonyms were used.

4 Results

The first research question focuses on how learners’ understanding of the object is mediated by the tools and artifacts used (text, images, and sound). Transitioning from academic assignment to script mode (switching to a different genre and finding a way to personalize a story) and incorporating non-text modes was a significant challenge for the six participants. Anna, in her reflections, explains the difference between a complex narration (the basis for the script) and the script of her final DS, which integrates images (transduction):

Yes, there is a narrative during the digital story but this narrative needs fewer details than the complex narration because the photos illustrate this information.

Following the narrative changes to the written text (transformation), the integration of multimodal elements allowed for a reduction in the number of words, partly due to the limited timeframe for the DS (around five minutes), but also because learners made use of the different semiotic resources, such as images and sound, to convey their meaning (synesthesia). Karen, in her reflection, explains how the chosen artifacts mediated the texts and what participants needed to consider when creating a multimodal text:

[My classmates gave me] ideas about which words I could eliminate and substitute with photographs, which helped me cut unnecessary words. One of the challenges for me was to eliminate words, because each word for me had profound meaning.

Hence, in working with images and sound, all the participants were involved in a process of transformation (within a mode) and transduction (between modes) as they created DSs.

Regarding the visual mode, the six participants’ evolving understanding of the value of implicit and explicit images mediated the development of their DSs. For instance, Kathy wrote in her questionnaire: “[T]he use of images allowed me to show emotion. For example, the dandelion and grasshopper represent hope, and the raindrops represent sadness.” Toward the end of the semester, in a process of transformation, the learners carefully selected and modified the images that would best reflect the meaning they were trying to convey. For example, in his questionnaire, Sam described his manipulation of image tones and colors:

At the beginning, the sepia-toned flowers and suburbs set the tone for the subsequent sequence, in which I began to foreground depressing pictures instead of manic or quirky ones. Toward the end of the process, the photo of the blue lotus, for whatever reason, had a strong impact on me and led me to consider that, after all the work I’d put in, the chain of images I’d constructed was finally complete.

With regard to the audio mode, the development of the DSs was also mediated by the learners’ understanding of the use of sound and music. Like other learners, Kerry, in her reflection, noted that the inclusion of sound allowed her to create specific emotions: “I used fast music when I wanted to express something happy and casual, and slow music to express more serious messages.” In another example, Anna reflected on the presentation of her story about immigration in Spain, saying that she had selected music that expressed not only the emotions she wished to convey but something about the topic itself:

I selected music with drums that sound like Africa, but it also has a Hispanic rhythm to signify the mix of both cultures. At the beginning, the tone of the narrative is dark, but at the end it is lighter because I learned something from this experience and I can use it to improve my life and the lives of others.

The melding of the various semiotic resources and their possibilities allowed learners to bring in new layers of meaning, in particular those relating to emotion. The six participants recognized that the integration of images and sound went beyond replicating the written text, and grasped that sound and music became an integral part of the story and had specific functions within the framework of the DSs. In fact, the learners became aware that when the scripts were read without these components, they sounded “choppy” and that where they had “gaps” in their DSs, “images and music filled them in” (Kerry, reflections). And when discussing the value of implicit and explicit images, Anna reflected:

It is not necessary to explain everything because the pictures themselves can explain.… In the oral narrative, the pictures explain emotions and the background of the story and help the audience understand the author’s purpose and connect with the message in the digital story.

Although selecting and integrating the sound and music tended to happen in the final stages of story development, in the questionnaire Sam noted that “the music gave the piece a sense of structure, as the various rhythms, moods and tempos generally corresponded to the story dynamics (rise-climax-fall-dénouement).” He went on to reflect:

When I added music, I realized that the text can be divided into five movements that correspond to the emotions evoked. It was obvious to me that the introduction deserved a restless stillness that mounted to a nail-biting crescendo, while the narration about my past demanded a frantic rhythm that suggested the passing of time as well as an internal instability. In contrast, the moment of truth needed something quieter, reflecting [how] the ideas in the background were settling down.

In addition to images, sound and music, learners exploited the editing software to convey meaning. Transition was probably the video-editing technique most commonly used to create atmosphere. For example, Kathy, who was developing a story with sad and somber overtones, preferred to use slow transitions. Other learners used Final Cut to integrate video, rotate images, or play with the zoom – finding instances of transformation and transduction. Only one learner, Sam, discovered that experimenting with sound editing features could express his intended meaning more effectively.

I left less space in-between lines during the first two sections to express a feeling of anxiety, disorder, and conflict that did not necessarily predominate in the written text alone. After the climax, however, I cut up the recording of my voice to leave more space in-between phrases and let words hang in the air, so to speak – an effect that combines with the meditative images and music to create a soothing impression that was not necessarily evident from the verbal text. (Sam, questionnaire)

These results illustrate how the learners’ personal selection, interpretation, and use of the available tools and artifacts varied the development of their DSs. Moreover, despite the initial contradictions that the introduction of new tools and artifacts brought to the L2 writing class, the six participants agreed that it had been a driving force of change. As Anna (questionnaire) pointed out, the introduction of the DS genre taught them “a new writing style” and Sam (questionnaire) mentioned that because of his work with images, text, and sound “the story constantly acquired new layers of meaning and connotations.” Transformations of the activity system occurred when the learners reflected on the purpose and process of L2 writing as they had previously understood it. Allison (questionnaire), for instance, stated that she had modified her story to inform not only the instructor but also all the “people who want to know about immigration, and [its] hardships, and what is happening for [immigrants] today.” Similarly, Sam admitted that his “initial goal for the project qua project was to get an A. Over the course of the semester, however, [he] became committed to making a beautiful and powerful work of art.”

The aim of the second research question was to understand how learners move from short-term goal-oriented actions to a long-term object-oriented activity. Although the learners were used to conducting research and were familiar with the formal nature of academic writing, they experienced some difficulties in understanding the transformation needed to portray the personal nature of the DSs. Kerry reflected:

I didn’t have to do much research with the digital story because of its somewhat personal nature, so it was easy for me. Although it was easier to write, it was more difficult to pinpoint the purpose of the story.

The short-term goal-oriented actions of developing the script aided the learners’ understanding of both the nature and the structure of the DSs. In terms of language, learners worked on a series of drafts that helped them to grasp the various components of the narrative, such as the gancho (hook) at the beginning of the story and the “rise-climax-fall” motif applied throughout. As Sam reflected, “I think the heavy lifting with regards to structure was accomplished during the classes about the narración compleja as this led me to consider how my work might fit into the traditional story structure.” At home, the learners reworked their scripts in the light of their new knowledge based on instruction and classroom feedback.

For instance, I reworked the text in order to emphasize the triangular “rise-climax-fall” motif, thereby increasing tension, and I also applied some of the concepts that I’d learned in the essay writing section of the course, such as the gancho at the beginning and the conclusion at the end” (Sam, questionnaire).

The learners also became aware of the orality of the DSs, which “read like a story rather than as a formal paper” (Anna, questionnaire), forcing them to question their assumptions about the use of the written word. The learners read the scripts aloud to their classmates so they could work on new drafts and on improving their reading. In terms of the visual mode, the learners selected images for each topic, analyzing them for implicit and explicit suitability. While learners were aware of the need to include both types of images in their final object, Kathy reflected that she knew that she wanted to include “a mix of implicit and explicit images.” Moreover, their selections changed as they drew closer to their final story version. Kathy, for example, commented in her reflection on how her “images have changed since the beginning of the semester” to improve how the text and images worked together.

Throughout the developmental stages, learners saw how the various modes (text, images, and sound) worked together. They realized that the non-linguistic modes were not supplementary to the written text, but had to effectively complement the central message, and that the inclusion of images and sounds would help them produce compelling multimodal metaphors. However, truly understanding this synesthesia was a challenge for the learners. It was not until they were constructing their final DSs that they fully realized the importance and impact of the images used. As Kathy (questionnaire) noted, “I ended up changing the order of my story and getting rid of some details because [the pictures] made them superfluous.” Other learners realized the need not only to combine the images with text to enhance specific emotions, but also to modify the images to intensify those emotions.

The challenge of learning, comprehending and adapting to this new form of written/oral expression was to understand which images I could use to express certain emotions and, when I found them, how I could position them to give more emphasis to what was important. (Kerry, questionnaire)

Similarly, the integration of sound was not fully apparent to them until the final stages. In some cases, the music was the last component integrated to draw the audience’s interest: “The music added a sad feeling to the story,” noted Karen in her questionnaire. In addition, the short-term actions (working on drafts, reading their stories aloud to their peers, receiving feedback from the instructor) helped the learners to achieve dramatic emphasis in their stories. As Kerry reflected, “Another very important element in the story was the intonation of the spoken words, and I paid special attention to that because it helped to dramatize my story.” Thus, it was not until learners read their script aloud and discussed the images and sounds in groups that they began to understand the real nature and potential of DSs.

Despite the familiar nature of the short-term oriented actions that guided learners through the different steps of creating their DSs, the learners acknowledged in their discussion groups that DS involved the novel integration of several modes to tell a single story. For example, after presenting his script and images to the group, Sam commented:

[My classmates] suggested that I get rid of some superfluous ingredients, such as excessive questions and praise, and that the images take the place of some commentary in the video—advice that led me to cut the running time back to only five minutes. (reflection)

Perhaps one of the main changes in the learners’ understanding of the object was the nature of DS as a public medium. Knowing that the DSs would be shown to a wider audience than the class increased the learners’ awareness of how interesting their DSs should and could be. “After I realized that the digital story would be published for an audience beyond the class (the instructor), I became aware that I had to make it more interesting.” (Karen, reflection). Anna reiterated this idea:

Knowing that the [digital story] was going to reach a wider audience than the class influenced me. I wrote it in such a way that the audience could understand and feel my message.

Finally, the third research question addressed what type of linguistic reorientation happens when learners move from traditional academic writing to a digital story script. The learners’ comments and reflections point to three main areas of change: vocabulary use, range of verb use (i.e. tenses and moods), and use of (or lack of) lexical connectors. With regard to vocabulary use, work on the set themes (e.g. immigration) in class and in their essays had supplied the learners’ background knowledge and a range of vocabulary that could be drawn on for writing about their specific topics. However, as they developed their scripts, the learners realized that, in addition to the topic-related vocabulary, they needed suitable words to express their personal views. This created the need for an enriched vocabulary to express feelings, emotions, and opinions.

I kept changing the vocabulary and also thought about the tone I would use for the narration of this story so the audience could feel the same emotions that the person experienced. (Karen, reflection)

When addressing the use of verb tenses and moods, learners recognized that they used the present tense more frequently in academic argumentative and expository texts than in their DSs. Anna said in her questionnaire that the learners felt they could use a wider range of tenses and moods in their DSs, including the present, past, and future as well as the indicative and subjunctive moods:

[We] can use a variety of verb tenses such as the pluperfect, subjunctive, conditional, and imperfect. The indicative mood expresses actions that happened but the subjunctive expresses doubt or opinions.

This is another interesting comment learners made related to the use of lexical connectors. As Anna pointed out in her questionnaire, “The connectors are the same for the argumentative and expository essays and the narrative essay.” However, when writing their DSs, the learners perceived a clear difference in the use of connectors.

The most obvious difference is the lack of connectors and sentences filled with clauses, which I normally use when I write essays. For me, this is due to the fact that [in the digital story] I wrote as if I were talking aloud, with the narration being an oral genre in which pauses, repetitions and inflections serve as connectors. (Sam, diary (emphasis in original))

Learners’ comments indicate that they needed to have a certain mastery of their own story to choose which connectors to replace with aural or visual components, and that they needed to be able to recognize when a pause or an inflectional tone change could be used to supply a transition (transduction).

5 Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine learners’ reflections and comments about developing a multimodal text, the DS, within the social semiotics and AT frameworks. By analyzing the learners’ perceptions of their actions, this study reflects their understanding of how the object was mediated by the use of multimedia tools and artifacts. The results show that the learners’ use of text, images, and sound via editing software influenced the development of their DSs. In terms of the written text (in contrast to Nelson’s (Reference Nelson2006) study), learners showed that they were able to understand the syntactic, vocabulary, and structural changes required to move from a traditional text to the narrative of a multimodal DS. This awareness was evident in the transformation from academic essays to story script, as expressed in the learners’ reflections on incorporating multimedia content. As in Oskoz and Elola (Reference Oskoz and Elola2014), learners became aware of the power of implicit and explicit images, and how their use could amplify the meaning of the written text to create compelling multimodal metaphors (Porto & Alonso Belmonte, Reference Porto and Alonso Belmonte2014). It was the fusion of images and sound that galvanized learners to discover new ways of structuring their evolving stories and impart emotion and meaning through them (Yang, Reference Yang2012). Thus, how well learners understood the power of images, the contribution of sound and music, and their own level of expertise and interest (or lack thereof) either facilitated or limited the accomplishment of their final products (Kaptelinin et al., Reference Kaptelinin, Kuutti and Bannon1995; Kuutti, Reference Kuutti1996). If the inclusion of the artifacts initially contradicted the learners’ previous views of L2 writing, their reflective analysis of the writing process and appropriation of the tools show that the tools’ use resulted in innovations and changes in the learners’ L2 writing practices. Yet, the learners’ object (their DSs) was seen and manipulated within the limitations and the possibilities set by the tools (Engeström, Reference Engeström1991). The DSs finally acquired emotional power through the learners’ interpretation and manipulation of the multimodal text.

In regard to learners’ perceptions on the use of tools and artifacts, they understood that their short-term oriented actions were directed toward the accomplishment of the long-term object-oriented activity; the learners were also aware of new orientations (conscious actions) associated with the new genre. During the course of the semester, the learners completed a series of actions, such as thinking about content, selecting images, writing text, and receiving feedback, all of which supported the achievement of the final goal (Kaptelinin et al., Reference Kaptelinin, Kuutti and Bannon1995). In the process, the learners were forced to question and reorient their automatic actions as they incorporated new tools, artifacts, genre, and goals (Kuutti, Reference Kuutti1996). Manipulating text, sound, and imagery; receiving instructor and peer feedback; listening and responding to classmates’ comments; and reading scripts out loud gave the learners a better understanding of their object. As Lemke (Reference Lemke2001) observed, the innovative use of artifacts helped the learners to link short-term events to long-term ones (Kaptelinin et al., Reference Kaptelinin, Kuutti and Bannon1995). With regards to semiotic synesthesia, in the development of the DSs, there were moments of transformation within modes (e.g. moving from an academic essay-oriented text to a digital storytelling script; selecting and reselecting images and ongoing color manipulation; and tailoring music) to moments of transduction, in which meaning could be illustrated first with words, then through an integration of words and images. Breaking the creation process down into steps helped learners to understand the concept of synesthesia (Kress & van Leeuwen, Reference Kress and van Leeuwen2006; Shin & Cimasko, Reference Shin and Cimasko2008; Yang, Reference Yang2012). Learners saw the interplay between multiple modes and manipulated them until their DSs finally told the stories they wanted to tell. This understanding helped learners to see their DSs as completed puzzles and not scattered pieces without meaning.

The last study question concerned the perceived linguistic orientation that took place when learners moved from academic writing to their DS script. The learners’ comments suggest that the personal nature of the DSs, with their melding of images and sounds, did have an impact on the language used in the narrative. In their efforts to reach their public, the learners tailored their vocabulary in their bid to move and influence their audience, moving from a logical, concrete, informative, and academic lexicon distinctive of argumentative and expository essays to more emotive vocabulary (Oskoz & Elola, Reference Oskoz and Elola2014). Learners also used a wider range of tenses than in previous essays, including the preterit and imperfect (Reyes et al., Reference Reyes Torres, Pich Ponce and García Pastor2012). Perhaps the most striking linguistic change was their reduced use of lexical connectors. Learners felt that the orality of the DSs allowed them to experiment with the use of pauses, repetition, and voice inflections to create transitions. As in Gregori-Signes’ (Reference Gregori-Signes2008) and the Oskoz and Elola’s (Reference Oskoz and Elola2014) studies, these learners became aware of the oral nature of the script and learned to include stylistic devices better suited to narration, creating a bridge linking oral and written proficiency (Lotherington, Reference Lotherington2008). Learners’ reflective conclusions suggest that the inclusion of the DS genre in the FL classroom can be a valuable pedagogical practice. As Sam noted in the questionnaire:

[The digital story] engages the student’s attention and breaks their expectations of the routines that language classes usually consist of…. [I]t simultaneously taps into and develops higher cognitive functions in both the student’s native and second languages…. [W]e’re applying our L2 to higher-level processes, as though we were “pushing ourselves” to do something more important than just practicing the language.

Producing a multimodal DS entailed the creation of meaning using more than one mode and working with language as an artifact; thus, the learners realized that the orality of language was just one more mode they had to work with, changing their understanding of the notion of a text.

6 Conclusion

Introducing a new genre into the FL classroom may require learners to apply different modes or new tools, and to reorient their actions to accomplish the new goal. Dealing with new genres also requires new writing practices that can result in necessary conflicts that help learners to grow as authors. In this case, a task-based approach enabled learners to reflect on and reconsider actions that had previously been automatic when drafting texts. As they developed their DSs in stages, these learners wrote creatively, organized their thoughts in coherent ways, and constructed their own narratives (Gakhar & Thompson, Reference Gakhar and Thompson2007; Robin, Reference Robin2006). Ultimately, they produced multimodal artifacts that resembled the sophisticated media products with which we are all familiar. The DS genre therefore combined the development of L2 linguistic and writing knowledge with 21st-century literacies, a central goal in modern FL curricula (Haffner & Miller, Reference Haffner and Miller2011).

Despite the positive outlook of this study, one must be cautious. First, the current study included only six participants, which limits the generalizability of its results, making them illustrative of potential behaviors rather than an indicator of trends or expected outcomes. Second, this study focused on the learners’ perspectives rather than on providing an objective assessment of their writing performance. Hence, a close comparison of traditional writing and creating texts in a multimodal genre could provide useful information about the inherent differences among these types of texts and how learners approach them. In the future, it would be of interest to examine in-class discussions about DS development, and the extent to which both the instructor’s feedback and peer comments influence the development of the DSs in terms of their audience, structure, and meaning, but also oral and visual modes. Despite the study limitations and need for further research, there is no doubt that the DS genre offers an opportunity to reshape the types of writing tasks used in Spanish FL advanced writing courses and to establish 21st-century literacy practices in the classroom.

Appendix

Students’ questionnaire

Name ___________________________

1. Native language ___________________________

2. Age _______

3. Gender: Female/Male

This semester, you wrote several academic essays (expository, argumentative and narrative essays). You chose one of your expository or argumentative essays as the foundation for your digital story. Please, answer the following questions.

4. What essay did you choose as your foundation?

5. What was the story that you wanted to tell?

6. Why did you want to talk about this story? Why was this story important to you?

7. What do you think this story reflects about the topic of the original essay?

8. In which emotions did you want your audience to engage when viewing your story?

9. When did you decide that the topic of your digital story was important to you?

10. How did the use of the images shape your story?

11. Describe at least two images that had an impact on you when you were searching and developing the story.

12. To what extent do your images have more than one meaning?

13. How did you combine the use of explicit imagery and implicit imagery? (Remember explicit imagery refers to the literal images that are used to illustrate a story and implicit imagery refers to the representation or implication of other meanings beyond the explicit image.)

14. What were the challenges when providing an emotional tone to your story?

15. How did the selected music enhance the narrative and images of your story?

16. How did you structure the story to appeal to your audience?

17. How did the pacing of your story contribute to the story’s meaning?

18. Who was the audience of your digital story?

19. Did the knowledge that this digital story was going to be posted on YouTube affect how you approached your writing?

20. How did the purpose of your story shift while creating your story?

21. What differences and/or similarities did you find between writing about the topic in an academic style and the writing for your digital story (writing processes such as planning, revision, etc., language choice, rhetorical elements)?

22. To what extent do digital stories as a medium develop writing skills?

23. Did your linguistic knowledge (grammar, vocabulary) improve during the semester? What differences do you see between working with academic writing and digital stories?

24. What resources (websites, images, equipment, etc.) did you use to complete your digital story?

25. What were your goals for this project? Did they change? If they did, what are the reasons that made you change your goal?

26. What is your perception of the final product (recording of digital story)? To what extent did your original idea of your digital story change during the process?

27. What have you learned about the topic you chose?

28. What makes digital story a worthwhile activity in the language classroom?