INTRODUCTION

Afanasyevo Culture and Sites

This study aims to systematize and analyze all radiocarbon (14C) dates available so far for one of the most important archaeological cultures of the Central Asian Paleometal period—the Afanasyevo. The problem of the attribution of the Afanasyevo Culture to a particular archaeological period has long been a complicated and topical issue. The culture has been attributed by various scholars to the Eneolithic (Gryaznov Reference Gryaznov1999; Vadetskaya Reference Vadetskaya1986) or Early Bronze Age periods (Kuzminyh Reference Kuzminyh1993; Molodin Reference Molodin2002; Pogozheva et al. Reference Pogozheva, Rykun, Stepanova and Tur2006). To avoid ambiguity, we will be using the term “Paleometal period.” Importantly, this culture is associated with the introduction of western/Central Asian domesticated herd animals (sheep, goat, cattle, probably horse) into East Asia, as well as skilled metallurgists who had an advanced tradition of construction of kurgans (tumuli). Afanasyevo people were migrants in Southern Siberia, who introduced a food producing economy into the local environment of ceramic-using hunter-gatherers (Anthony Reference Anthony2007). Modern anthropological and DNA data support the hypothesis of the distant Western ancestry of the Afanasyevo population (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Allentoft Morten, Nielsen, Orlando, Sikora and Sjögren2015; Khokhlov et al. Reference Khokhlov, Solodovnikov, Rykun, Kravchenko and Kitov2016). The majority of the Afanasyevo sites have been discovered in the Altai-Sayan mountain region, which comprises a system of ridges of various elevations, river valleys, plateaus, and intermontane basins with continental climate (Figure 1). There have been 35 cemeteries and 12 settlements discovered in the Middle Yenisei River area, and 77 cemeteries, ca. 40 settlements, a ritual site, a mine, and traces of human activity identified in four caves in the Altai Mountains (Vadetskaya et al. Reference Vadetskaya, Polyakov and Stepanova2014). The distance between the Altai and the Middle Yenisei Region groups of sites is at least 300–500 km, and the distance between the closest sites within those regions is 0.5 to several kilometers, which demonstrates their strong concentration in certain valleys and basins. Individual Afanasyevo type sites and artifacts have also been found in other areas of Central Asia—Northwest Mongolia, Northwest China, and the Zeravshan River Valley (Molodin and Alkin, Reference Molodin and Alkin2012; Avanesova Reference Avanesova2012).

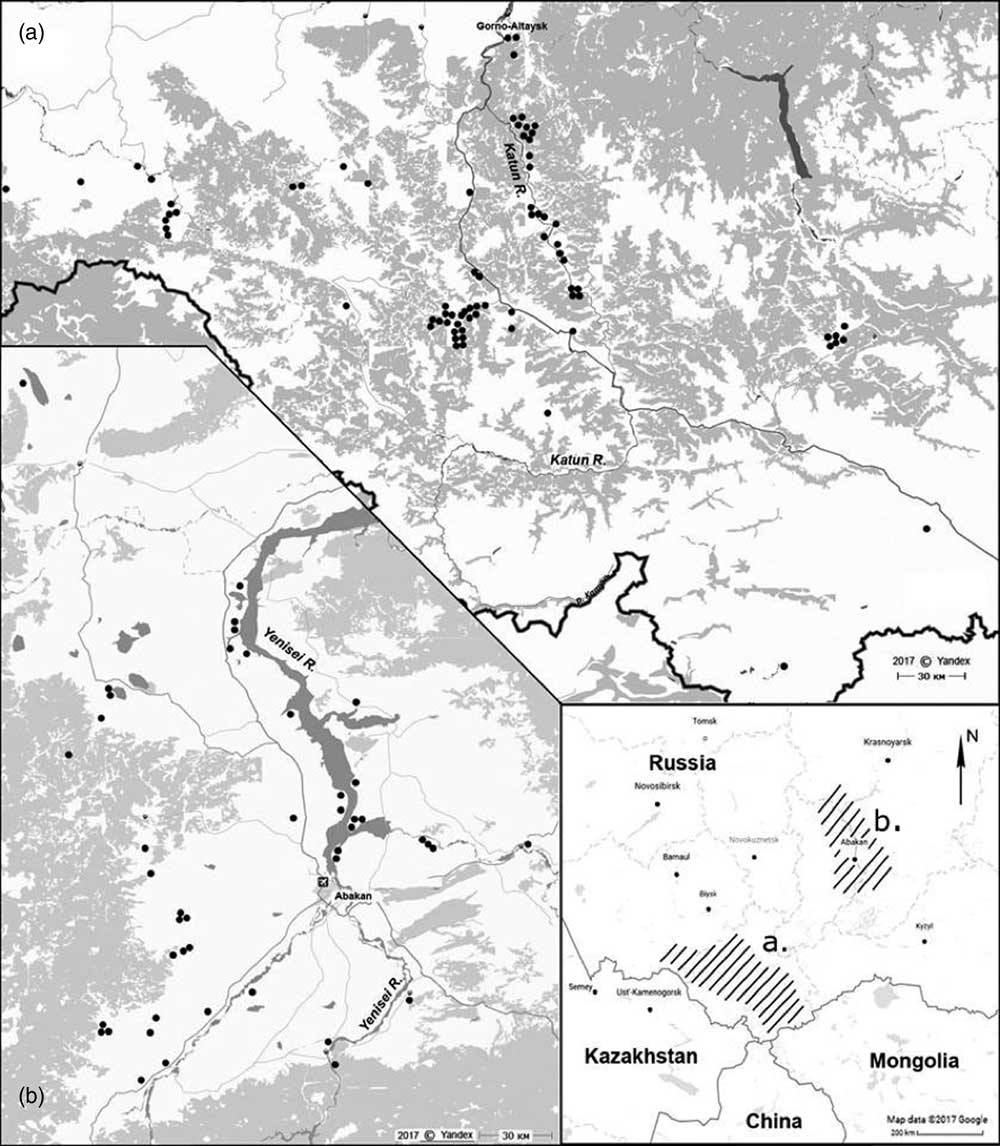

Figure 1 Location map of the Afanasyevo Culture sites in (a) Altai and (b) the Minusinsk Basin.

In the Altai, Afanasyevo sites are mainly located in the valleys of the Katun River and its tributaries, at an altitude of 450–4000 m asl. With the altitude increasing from northwest to southeast, the territory is divided into low-, mid- and high-mountain zones. Apart from highlands, the landscape encompasses intermountain basins. The Altai has an extensive hydrological system, with the largest river being the Katun and its main tributaries the Koksa, Argut, Chuya, Kadrin, Ursul and Sema. The nature of vegetation in the region is determined by topography and altitude—the mountain-steppe, mountain-taiga and alpine high-altitude zones are clearly defined in the region. Different areas of the Altai Mountains have distinctive zonal characteristics, related to climatic differences.

In the Middle Yenisei Region, Afanasyevo sites are located in the Minusinsk intermountain basins, which stretch along the middle reaches of the Yenisei River. This is a relatively small (ca. 350 × 100 km) area of rolling steppe, surrounded on all sides by mountains—the Eastern and Western Sayan and Kuznetsky Alatau. The altitude of the basins is 300–400 m asl. They are comprised of steppe and forest steppe, surrounded by taiga covered mountains. Such proximity of different climatic zones is an important feature of this territory. The Minusinsk depression is very rich in aquatic resources. From south to north, it is cut by the Yenisei River with its multiple tributaries, the largest being Abakan and Tuba. The area encompasses hundreds of lakes. Such a wealth of natural resources allowed prehistoric people to use variable economic models.

Absolute Dating of the Afanasyevo Culture: Overview

A specific feature of the Afanasyevo Culture is its very broad date range, running from the end of 4th to the beginning of 2nd millennium. BC based on both relative cultural analogies and 14C dates (see Tsyb Reference Tsyb1984; Molodin Reference Molodin2002).

Kiselev (Reference Kiselev1938) was the first scientist to raise the issue of the absolute chronology of the Afanasyevo sites. Based on a series of objects (“censers, cylinders, beaters”), he suggested that Afanasyevo cemeteries were synchronous with “Yamnaya-Catacombnaya burials” and dated them to the 3rd to beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. This approach was followed by researchers until the appearance of the first 14C dates. In the 1970s, M.P. Gryaznov (Reference Gryaznov1999) admitted that “we do not yet have data for direct dating of the monuments of the Afanasyevo Culture in the Minusinsk steppes. Their mentioned affinity with the monuments of the Yamnaya (“Pit Grave”) Culture only allows suggesting their synchroneity to Yamnaya, which is usually dated to the second half of the 3rd millennium BC. Hence, the Afanasyevo Culture is accepted to date to the same time. If the date of the Yamnaya Culture changes, the date of the Afanasyevo Culture will also be needed to be changed, respectively.”

The issues of dating the Afanasyevo Culture have been discussed by many researchers. M.D. Hlobystina (Reference Hlobystina1975) dated the Afanasyevo Culture of Altai from the second half of the 3rd millennium BC based on relative analogies with the the material culture and funeral rite of the Yamnaya Culture. On the basis of the relative similarities with the monuments of the Yamnaya cultural-historical region in Eastern Europe, the Kelteminar Culture of Khwarezm and other cultures, and 14C dates from five burials, Tsyb (Reference Tsyb1984) dated the Afanasyevo monuments of Altai to the end of the 4th to the first quarter of 2nd millennium BC. Savinov (Reference Savinov1994), exploring the materials from the burials of the most southerly Afanasyevo burial in the Altai Mountains—Bertek-33— noted that, at that stage of the study of the culture, the most likely date for it would be the 3rd to the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. Pogozheva (Reference Pogozheva2006) suggested that the Afanasyevo population appeared in the Altai in the first half of the 3rd millennium BC and that it would be difficult to give a more precise date. According to Molodin (Reference Molodin2002), the general trends in the development of cultures of Eurasia, outlined in his summary work, suggested a chronological framework for the Afanasyevo Culture which ran from the 4th to the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC.

The radiocarbon stage in the study of the Afanasyevo Culture began in the 1960s (Sementsov et al. Reference Sementsov, Romanova and Doluhanov1969). First, individual sites were dated, and later attempts were made to determine the chronology of the culture in general. Vadetskaya (Reference Vadetskaya1981) was the first scholar to propose the dating of the Afanasyevo Culture based solely on (non-calibrated) 14C dates. The same year, the first 14C dates for Altai sites were published, which were used as a basis for the absolute dating (Kiryushin et al. Reference Kiryushin, Posrednikov and Firsov1981). Analyses were carried out in the laboratories of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (SB RAS; Novosibirsk, lab code SOAN), the Institute for the History of Material Culture of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IHMC RAS; Saint-Petersburg, lab code Le) and the German Academy of Sciences (Berlin, lab code Bln) using conventional beta counting methods (LSC and GPC). However, only non-calibrated dates were used at that time, which seriously affected the conclusions.

The constant gradual increase of the number of 14C dates lead to the necessity of revisiting the data at a new level. To date, 102 14C dates have been obtained for the Afanasyevo Culture—39 for the Middle Yenisei Region and 63 for Altai (including Mongolian Altai).

The Problem of the “Wide” Chronology of the Afanasyevo Culture

For a long time, the lengthy existence of the Afanasyevo Culture was not questioned for a number of reasons, partly because of the lack of known archaeological sites of cultures preceding and succeeding Afanasyevo in the Altai Mountains. It was even suggested that Afanasyevo was an ultra-conservative culture and that the population survived little changed until the Early Iron Age (Abdulganeev et al. Reference Abdulganeev, Kiryushin and Kadikov1982), which was partly “supported” by the 14C dates (Kiryushin et al. Reference Kiryushin, Posrednikov and Firsov1981).

In the past two decades, special attention has been given to the Afanasyevo Culture. As a result, the contradictions between the results of 14C dating and archaeological data have become particularly apparent. According to 14C analysis, the chronological span of the Afanasyevo Culture can be identified as 38th–25th century BC for the Altai Mountains, and 33rd–25th century BC for the Middle Yenisei Region (Svyatko and Polyakov Reference Svyatko and Polyakov2009; Polyakov Reference Polyakov2010). However, with growing data from 14C dating and material culture, it has become obvious that the proposed existence of the Afanasyevo Culture for 1400–1500 years is very extended; there is no archaeological evidence for the Afanasyevo population residing there for such a long time (Stepanova Reference Stepanova2009, Reference Stepanova2012; Vadetskaya et al. Reference Vadetskaya, Polyakov and Stepanova2014). A chronological period of almost 1500 years must inevitably split into stages, traceable in the development of all elements of the culture, including the funeral rite. However, despite almost a century of the study of Afanasyevo antiquities, such a development has not been established and described.

Another important argument in favor of the shorter existence of the culture is the scarcity of archaeological sites. As a rule, the long-existing archaeological cultures are characterized by several times greater number of burial complexes and people buried, such as has been recorded for the Yamnaya Culture (Fisenko Reference Fisenko1970; Merpert Reference Merpert1974; Kovaleva Reference Kovaleva1984; Yarovoy Reference Yarovoi1985, Reference Yarovoi1990; Dergachev Reference Dergachev1986; Shaposhnikova Reference Shaposhnikova, Fomenko and Dovzhenko1986; Morgunova and Kravtsov Reference Morgunova and Kravcov1994). For example, for the Andronovo Culture of the Altai, 62 funerary complexes are known, containing more than 700 burials dating to the 19th and 18th century BC (i.e. for only two centuries in total; Kiryushin and Papin Reference Kiryushin and Papin2010; Kiryushin et al. Reference Kiryushin, Papin and Fedoruk2015). Quite illustrative are the materials of the Karasuk Culture, dated to the 13th–9th century BC (i.e. 500 years of existence), yet already ca. 3000 burials have been investigated to date, with this only being a few percent of the total number of burials known (Polyakov Reference Polyakov2006). At the same time, to date only about 600 Afanasyevo burials in total have been excavated—more than 300 in the Middle Yenisei Region, more than 200 in the Altai, and ca. 10 in Mongolia.

The territory of the Altai Mountains and Minusinsk Basin has already been sufficiently explored archaeologically, and therefore there is no reason to expect a significant increase in the number of new monuments to be discovered. Taking into account the Afanasyevo cemeteries that have not been excavated, as well as the fact that some burials have not been discovered yet, the number of monuments is still insufficient to assume the long existence of the culture implied by the 14C chronologies. In this regard, the data on the number of the deceased people is of a particular interest. In the Middle Yenisei Region, the average number of kurgans within a cemetery usually does not exceed 10, and the cemeteries themselves are extremely rare. The largest number of people buried within one site is 66. In the Altai, the number of kurgans within a cemetery is often more than 40 (Perviy Mezhelik-1, Saldjar-1), but there are also sites containing fewer than 10 kurgans (Elo-1 and 2, Bertek-33, and others). Judging by the almost completely investigated major burial ground of Saldjar-1, the number of people buried within is around 40 (only 13 of them adults, the rest are children and teenagers; Vadetskaya et al. Reference Vadetskaya, Polyakov and Stepanova2014). Even if we assume that each cemetery contains 13–15 adults, this is still much less than in sites of other archaeological cultures. Therefore, most Afanasyevo cemeteries in both regions functioned for short periods. It is also worth noting that there are several times more Scythian sites in the Altai than Afanasyevo, despite the chronological span of the former is limited to 200–300 years (Marsadolov Reference Marsadolov1985; Surazakov Reference Surazakov1989; Kiryushin and Stepanova Reference Kiryushin and Stepanova2004; Slyusarenko Reference Slyusarenko2010 and others). Similar examples can be highlighted for other Paleometal to Early Iron Age archaeological cultures of the Sayan and Altai Mountains.

The hypothesis of the synchronous and short-term functioning of many of the Afanasyevo sites is also supported by the analysis of pottery. The characteristics of manufacturing technology and ornamentation of the Afanasyevo ceramics from the Altai suggest that many of the items were manufactured in a short period of time by several groups of potters (at different sites). Two to four vessels, obviously made by same group of craftsmen within a few years, can be found in various sites, and this allows synchronizing the sites. Comparison of such groups of vessels indicates that most cemeteries and settlements were close to each other chronologically (Stepanova Reference Stepanova2009). The analysis of manufacturing technologies shows that Afanasyevo potters adapted to new environments and unfamiliar territories. The materials from the majority of sites indicate rapid decline of the introduced, foreign traditions and the emergence of new ones, more specific to mountainous areas. This has been recorded for both the source raw materials and artificially introduced mineral impurities in the fabric of the clay (Stepanova Reference Stepanova2008, Reference Stepanova2010c, Reference Stepanova2015).

Another reason for the refinement of the chronology of the Afanasyevo Culture is that its 14C dates are relatively earlier than those of the Yamnaya Culture, which does not agree with modern archaeological theories (Polyakov Reference Polyakov2010). There are no doubts among researchers that the formation of the Afanasyevo Culture was a result of a major migration wave from the west (e.g. Mallory Reference Mallory1989; Mallory and Mair Reference Mallory and Mair2000; Anthony Reference Anthony2007; Kuzmina Reference Kuzmina2007). This has also been confirmed by the latest aDNA tests that directly link the Yamnaya Culture and the Afanasyevo Culture (Allentoft et al. Reference Allentoft, Sikora, Sjogren, Rasmussen and Rasmussen2015). If we accept the fact of formation of the Afanasyevo Culture by the 38th century BC, it will also need to be accepted that all known similarities have been borrowed by the Yamnaya Culture from the supposedly more ancient Afanasyevo population, which has no archaeological evidence. The trajectory of all major innovations during this period would be assumed to have been directed from east to west, and not vice versa.

To sum up, it should be noted that there is no other archaeological culture that could be characterized by such a relatively small number of funerary complexes and such wide chronological boundaries. Either there was extreme paucity of the Afanasyevo population in the Altai Mountains or there was an extended chronology of this culture. The revision of the dating of the Afanasyevo Culture has become highly topical. This study aims at resolving this contradiction.

14С Dating of the Afanasyevo Sites

First Data

The Afanasyevo Culture was one of the first in Russia to be 14C dated. In the late 1950s, one of the first 14C laboratories in the country and in the world was organized in the Leningrad Branch of the Institute of Archaeology of the USSR (presently IHMC RAS; Zaitseva Reference Zaitseva2007). In this same period, the major Krasnoyarsk expedition led by M.P. Gryaznov started its work in the Middle Yenisei River region. At his disposal were new materials from the entire stratigraphic column of the archaeological cultures of the region. However, at the initial stage, due to laboratory requirements, only charcoal and, later, wood samples could be analyzed, which greatly limited the number of archaeological sites for which a 14C age could be determined. Bone samples started to be dated routinely in the laboratory of IHMC RAS only in the mid-1990s, and, as such, the overwhelming number of the Afanasyevo dates are still those made on charcoal and wood, especially for the Minusinsk Basin sites, where 14C dating was initiated earlier than in Altai. The 14C dating of the Altai sites was not started until the 1970s (Ermolova and Markov Reference Ermolova and Markov1983; Orlova Reference Orlova1995).

Among the Paleometal cultures of the Middle Yenisei Region, wooden structures are widely present only in the sites of the Afanasyevo and later Andronovo (Fyodorovo) Cultures. It is with them that the 14C research into archaeological sites of Siberia began (Sementsov et al. Reference Sementsov, Romanova and Doluhanov1969). The very first 14C dates for both cultures appeared extremely scattered, and this drew a lot of skepticism towards them (Svyatko at al. Reference Svyatko, Mallory, Murphy, Polyakov, Reimer and Schulting2009; Polyakov and Svyatko Reference Polyakov and Svyatko2009). This has led to persistent distrust of 14C dating among Soviet and Russian researchers for several decades (see Molodin Reference Molodin2002).

The entire initial period of 14C research into the Afanasyevo Culture can be characterized by a large number of issues, which question the attribution of a number of obtained dates. The major issue is concerned with the sampling and lack of understanding of the very principles of the method. Often “charcoals” from the grave filling were dated, however, their connection with the burial itself was not obvious, as it happened, for example, with kurgan 2 of the Maliye Kopeny II cemetery (Le-455; Vadetskaya Reference Vadetskaya2012). The situation is similar for the Vostochnoye kurgan, where the charcoal sample (Le-1316) was taken from the “little fireplace,” located within the mound but not directly associated with the graves, and not containing any artifacts (Vadetskaya et al. Reference Vadetskaya, Polyakov and Stepanova2014), and for a number of sites in the Altai, where charcoal samples were taken from grave filling or ceiling.

Another problem for the Middle Yenisei Region is later intrusions, in particular, intrusive burials of the succeeding Okunevo Culture (Maksimenkov Reference Maksimenkov1965). This is a widespread phenomenon, which is not always possible to identify reliably—at the later stages of the Okunevo Culture, the burials did not contain grave goods. In total, 95% of the Afanasyevo graves were subject to later intrusions. As a result, there is always a chance that the individual found in the grave without directly related goods is a later burial. In addition, the wooden ceiling of the grave, or some of its logs, could be replaced. In this case, the obtained 14C date will define not the time of construction of the Afanasyevo mound, but the time of the intrusion of the Okunevo burial. Perhaps this was the case with grave 3 of kurgan 4 of the Chernovaya VI cemetery. This mound contained the intrusive cist №5 with Okunevo tools, and it cannot be excluded that the central Afanasyevo graves (№3 and №4) may also be intrusive Okunevo burials (Vadetskaya Reference Vadetskaya2010). Therefore, the date received from the “wood sample from the fallen ceiling of the pit” (Le-532) raises certain doubts as to its immediate connection with the very moment of construction of the Afanasyevo kurgan. Moreover, by modern views, the date itself, 3700 ± 80 BP (2346–1883 cal BC), rather corresponds with the timing of the Okunevo Culture (Polyakov and Svyatko Reference Polyakov and Svyatko2009; Svyatko at al. Reference Svyatko, Mallory, Murphy, Polyakov, Reimer and Schulting2009).

Taking into consideration the aforementioned problems, the most controversial dates for which attribution to the Afanasyevo Culture is doubtful (Le-455; Le-532; Le-1316) were excluded from further statistical analysis.

AMS Dates

A new stage in the study of the 14C chronology of Southern Siberia commenced with the appearance of the first accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) dates. The largest series of 88 human bone samples was analyzed in the laboratory of the 14CHRONO Centre for Climate, the Environment, and Chronology (Queen’s University Belfast, UK) in order to obtain a fully coherent chronological sequence of the Paleometal archaeological cultures of the Middle Yenisei. All 14C dates available at the time for the region were assembled and a new chronological scale, fully based on the results of the 14C analysis, was developed (Polyakov and Svyatko Reference Polyakov and Svyatko2009; Svyatko at al. Reference Svyatko, Mallory, Murphy, Polyakov, Reimer and Schulting2009). Only five new Afanasyevo 14C dates for the Middle Yenisei sites of Afanasieva Gora and Karasuk III were introduced, and, being much less numerous than the ones obtained by conventional methods, they did not have a major influence on the overall perception of the timing of the culture (Polyakov Reference Polyakov2010).

Later, along with the increasing number of beta counting dates, another small series of AMS dates was made in the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (University of Oxford, UK) as part of a DNA study of ancient Siberian populations by the Centre for GeoGenetics of the Natural History Museum of Denmark (University of Copenhagen; Rasmussen at al. Reference Rasmussen, Allentoft Morten, Nielsen, Orlando, Sikora and Sjögren2015). However, the number of AMS dates was still rather small, and they were only produced for the Middle Yenisei sites.

The turning point, which prompted the revision of the chronology of the Afanasyevo Culture, was a series of new AMS 14C dates from human and animal bones from the Afanasyevo sites of Altai also produced in the 14CHRONO Centre (Svyatko et al. Reference Svyatko, Polyakov, Soenov, Stepanova, Reimer and Ogle2017b). These included the repeated analysis of burials previously dated by the liquid scintillation counting (LSC) method. Subsequently, one more date from a wood sample was obtained in the same laboratory. The discrepancies observed from these tests required a new interpretation of the results and prompted the present study.

METHODS AND MODERN RESEARCH

Two methods have been used to 14C date the archaeological materials of the Afanasyevo Culture.

For decades, beta counting remained the only approach. It involves measuring the radioactive decay of individual carbon atoms and requires a long counting time to achieve accuracy of the date. It also requires a large sample size—500–700 g of bone and 200–400 g of wood or charcoal.

The alternative AMS method, developed in the late 1970s, involves a direct counting of the number of 14C and 12C atoms in a sample, rather than measuring its activity. As a result, AMS is much faster—an accuracy of 1% can be achieved in several minutes, and it requires a far smaller sample size, from a few milligrams to a gram, depending on the sample type.

Notably, the recent 14C intercomparison exercises (VIRI) showed general agreement in the results when comparing radiometric and AMS laboratories both for bone (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Cook and Naysmith2010a) and wood/charcoal samples (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Cook and Naysmith2010b), despite the early 14C intercomparison exercises showing that LSC laboratories needed a larger lab error multiplier (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Cook, Harkness, Miller and Baxter1992).

From the total number of ca. 100 14C dates presently available for the Afanasyevo Culture, 76 were produced using beta counting (LSC and GPC), and 25 using AMS.

Presently, much attention has also been given to the influence of freshwater reservoir effects on 14C dates of various types of archaeological materials, including bones of humans and some animals (e.g. fish). The freshwater reservoir effects appear as older 14C dates of organisms with a diet that included “old” carbon from freshwater sources (Lanting and van der Plicht Reference Lanting and van der Plicht1998). The studies have been carried out in several regions of Southern Siberia, including the Minusinsk Basin (Svyatko et al. Reference Svyatko, Reimer and Schulting2017a) and the Altai (Svyatko et al. Reference Svyatko, Polyakov, Soenov, Stepanova, Reimer and Ogle2017b). This research revealed an interesting pattern. Modern fish showed freshwater reservoir offsets of 165 ± 30 to 757 ± 31 14C years for the Minusinsk Basin (n=4) and 578 ± 36 and 1097 ± 40 14C years for Altai (n=2). For archaeological samples, only six associated groups of samples (including human and herbivore bone, charcoal and wood) from the Afanasyevo, Okunevo, Karasuk, and Tashtyk Cultures have been dated. Surprisingly, with the exception of one Tashtyk pair, these groups showed no clear evidence for a reservoir effect. From stable isotope analysis it is not clear whether humans were consuming any significant amounts of fish in the Altai; for the Minusinsk Basin stable isotopes are indicative of fish contributing to the diet (Svyatko et al. Reference Svyatko, Schulting, Poliakov and Reimer2017c).

Absolute Chronology

Altai Burial Sites and “Old-Wood Effect”

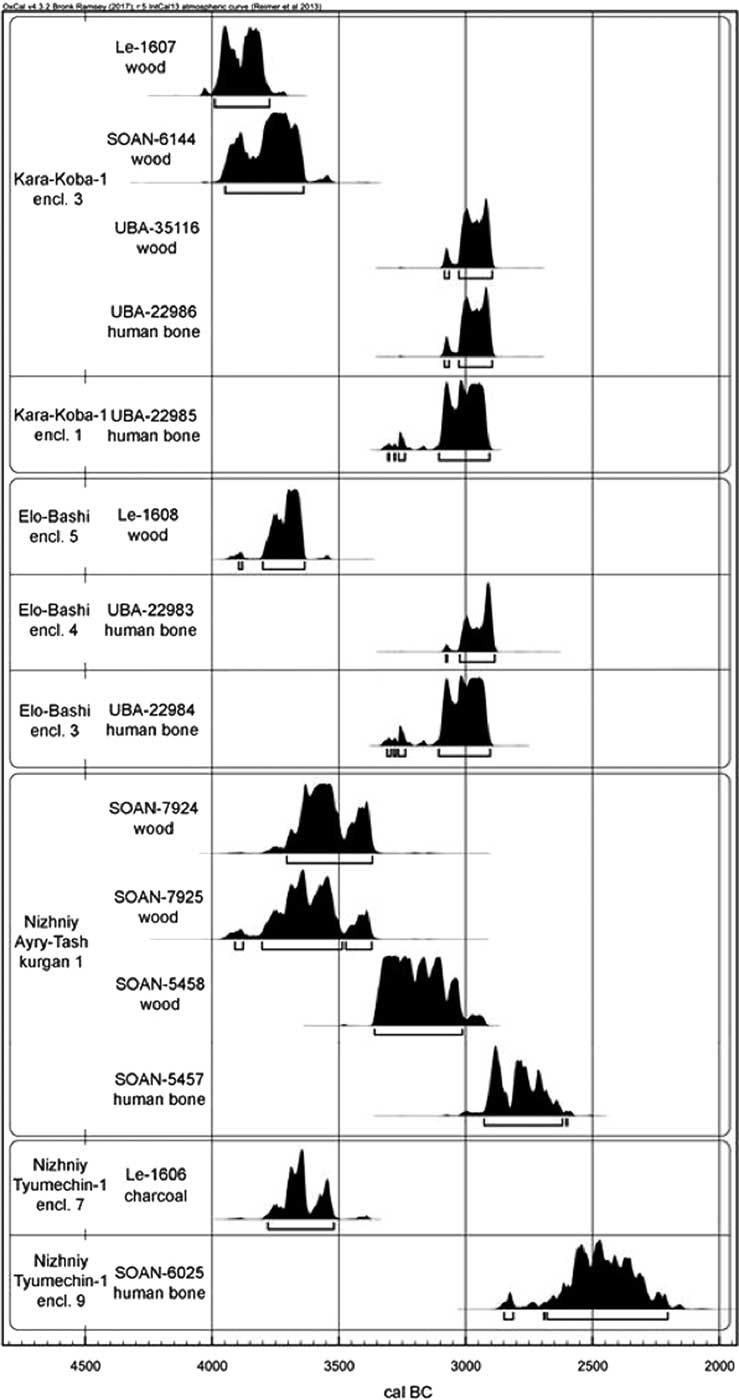

A new series of 14C dates for the Afanasyevo sites from the Altai (Svyatko et al. Reference Svyatko, Polyakov, Soenov, Stepanova, Reimer and Ogle2017b) highlights the issue of credibility of a number of earlier dates. Comparison with the previous results demonstrates major discrepancies. For example, based on earlier 14C dates from wood (Le-1607 and SOAN-6144), the cemetery of Kara-Koba-1 was considered to be one of the oldest Afanasyevo funeral monuments (Figure 6 in Polyakov Reference Polyakov2010). However, two new dates (UBA-22985 and UBA-22986) obtained from human bones from the same grave and the kurgan beside are 600–700 years younger (Figure 2). An additional AMS date from wood of the same grave (UBA-35116) is synchronous with the new human bone dates. Thus, based on AMS dating, this burial ground appears much more recent than previously thought.

Figure 2 Comparison of calibrated 14C dates for wood/charcoal and human bone samples from the same Afanasyevo cemeteries in Altai.

A similar situation can be observed for another “oldest” cemetery of Elo-Bashi—the single date received from a wood fragment of enclosure 5 is also around 600 14C years older than that from human bones from enclosures 3 and 4 (Figure 2). Two more cases should be brought up here, which have previously been mentioned, but have not been regarded as systematic phenomenon (Figure 7 and 8 in Polyakov Reference Polyakov2010). The first case is dates from Nizhniy Ayry-Tash kurgan 1 (SOAN-5457 and SOAN-5458), where the wood sample turned out to be at least 250 years older than human bone. Two more dates obtained later from wood samples from this burial also came out 500–600 years older than the human bone (Soenov et al. Reference Soenov, Akimova (Vdovina) and Triganova2012; Table S1, Figure 2). The second case is the cemetery of Nizhniy Tyumechin-1. The dates measured on the wood sample from enclosure 7 (Le-1606) appeared 900 years older than those on human bone from enclosure 9 (SOAN-6025).

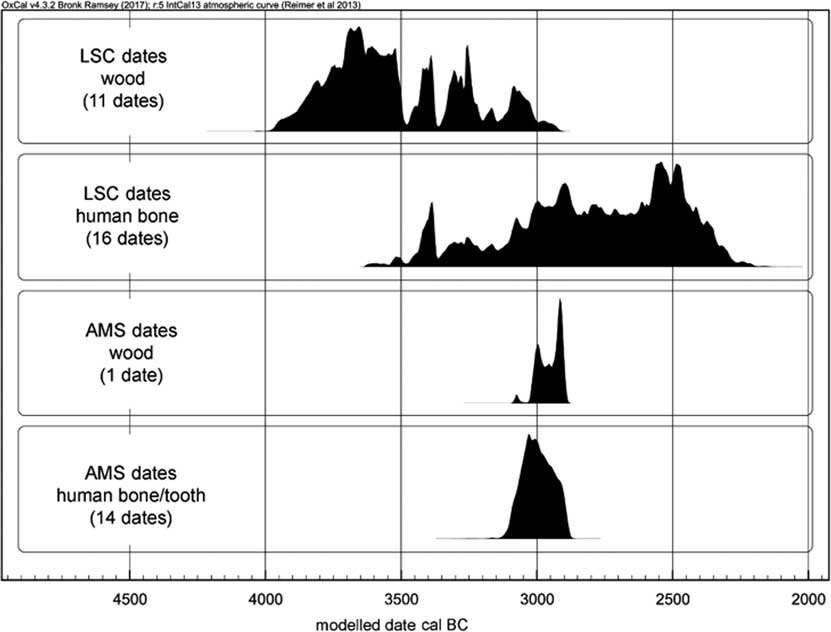

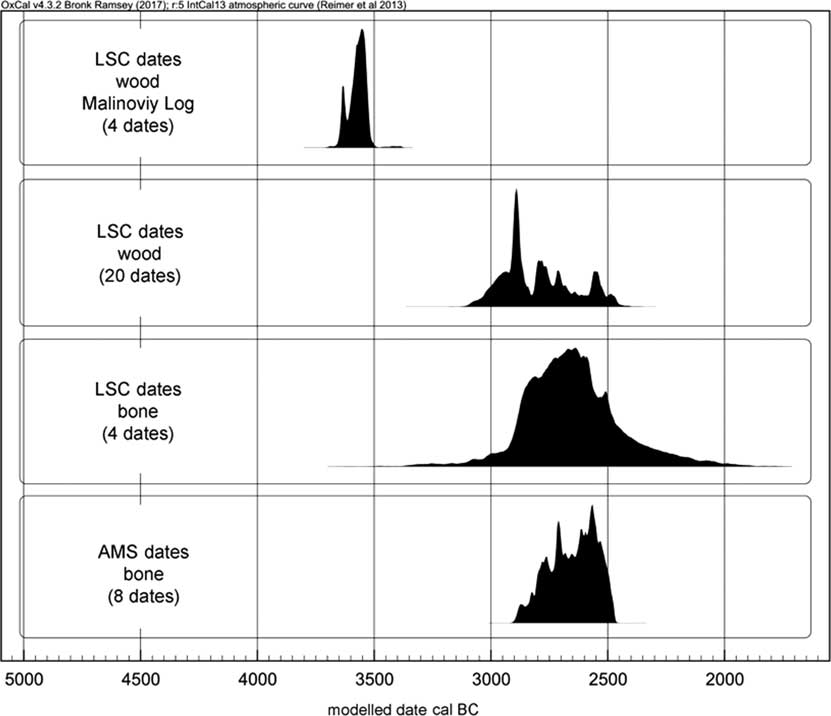

Two measurements from the wood samples from the Kara-Koba-1 cemetery (Le-1607 and SOAN-6144) made in different laboratories, however, produced almost identical results. This suggests that such an old date is not an analytical error. The trend towards the 250–600 14C years older dates from wood/charcoal samples is evident for virtually all analyzed sites of the Altai where the LSC method was used. This apparently systematic effect requires further investigation. The summed probability of wood dates is older than that from bone samples (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Calibrated summed probability for the Afanasyevo cemeteries of the Altai by sample type and method.

The factors leading to older dates from wood/charcoal samples are well known. Firstly, is the sampling of the central part of the tree trunk. The preservation of wooden structures in burials rarely allows sampling external rings that actually date the moment of cutting of the tree. Usually only the central part, which carries information about the initial period of the growth of the tree, is preserved. However, for the construction of burial ceilings, Siberian larch (Lárix sibírica) trunks about 30–40 cm in diameter were used. This species is fast-growing and its age with such a diameter should not exceed 50 years. Therefore, the chronological shift that occurs when using the central part of the logs should not be more than 50 years.

Secondly, the potential old-wood effect must be taken into account when the sampled tree was cut down in advance or reused. For example, for the construction of burials, a no-longer-needed structure could be dismantled and reused. Larch timber is characterized by high density and is rather resistant to rotting. However, its strength properties are not unlimited and do not last for centuries. Thus, the reuse of older logs cannot be the cause of such large discrepancies, especially because wooden structures have not been recorded before the arrival of the Afanasyevo population in the Minusinsk Basin and the Altai.

One of the explanations for the up to 600-year-older dates from wooden constructions may be related to the following feature of Siberian larch. Like oak, its strength improves when steeped in water, becoming stronger and significantly more resistant to decay. Steeping usually occurs naturally when the tree falls into the water—and as larch is a dense, heavy wood, it sinks. It is possible that Afanasyevo mound builders used larch from rivers or from old river beds, as well as collected logs washed out on the shore for construction. Another source of old wood could be trees killed by frost. This phenomenon is common, for example, in the valley of the Ursul River, where the cemetery of Kara-Koba-1 is located. Possibly such trees were more “available” to the Afanasyevo people. In general, based on a number of reasons, the 14C dates from wood may actually be several hundred years older than the time of construction of a kurgan.

However, the problem of the older dates from wood samples, produced by the LSC method, is much wider. As has already been mentioned, the only AMS date available at present from wood—from the Kara-Koba-1 cemetery—did not show the older age and appeared synchronous to the bone sample. This result raises even more questions. Perhaps the reasons for the older dates are not only related to material itself but also to the analytical method or laboratory used.

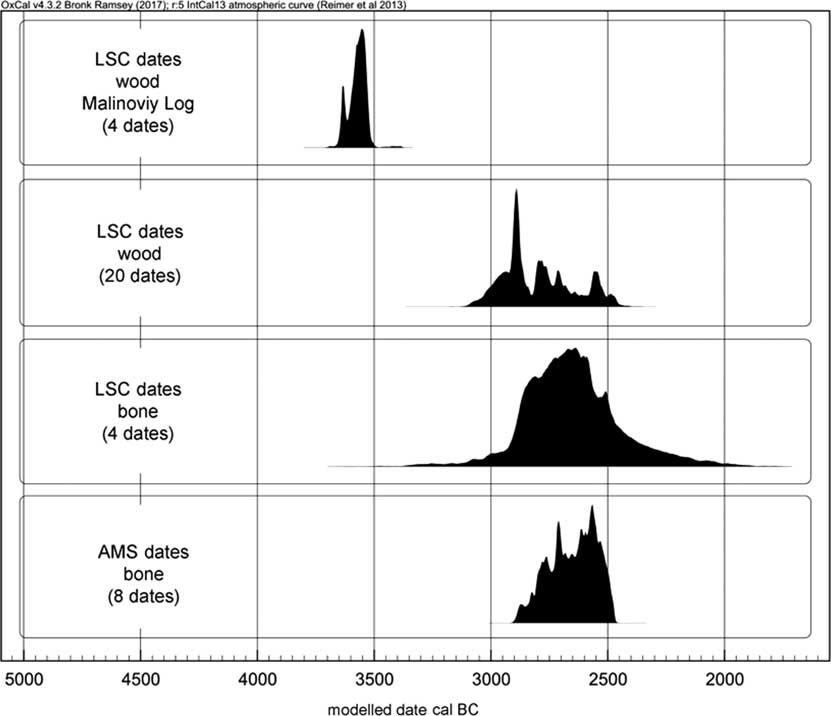

Middle Yenisei Region Sites

For the Minusinsk Basin sites, measurements on wood and charcoal samples (n=27) prevail significantly. Only eight AMS and four LSC dates have been produced from human bone and tooth samples. Unlike in the Altai, the majority of dates from wood here are similar to those from bones/teeth (Figure 4). The only site where the dates can be suspected to be too old is the aforementioned Malinovy Log (Bokovenko and Mityayev Reference Bokovenko and Mityaev2010; Polyakov Reference Polyakov2010). Four dates from wood from the roofs of two adjacent mounds demonstrate an amazing clustering. But there is about a 600-year gap between them and the rest of the dates from other burial grounds. This is another important evidence for the non-randomness and consistency of the phenomenon. The modern model of the development of the Afanasyevo Culture in the Middle Yenisei attributes this cemetery to the late period (Lazaretov Reference Lazaretov2017a, Reference Lazaretov2017b). In this case, the discrepancy with the real date of burial can reach about 800 years.

Figure 4 Summed probabilities of calibrated 14C dates for the Afanasyevo cemeteries in the Middle Yenisei by sample type and method.

Only one attempt to 14C date various materials from the same Afanasyevo burial has been made in the Middle Yenisei, for the Itkol II cemetery kurgan 23 grave 2. This attempt has not been very productive, as the age range for human bone appears too wide (Figure 7 in Polyakov Reference Polyakov2010). However, based on the dates of the Afanasyevo sites in the Altai, we can now assume that a number of dates from wood samples of the Minusinsk burial grounds can also be too old (such as Malinovy Log site). At the same time, analyzing the entire assemblage of dates, it may be observed that, as opposed to the Altai, some of them (Le-931, Bln-4769, Bln-4919) are located on the top of the chronological range and cannot be too old. Apparently, while in the Altai the older dates from wood samples are a systematic phenomenon, in the Middle Yenisei this happens only sporadically.

AMS versus LSC Dates

The appearance of AMS dates brought up another important issue. For the human bone samples, the dates produced by the beta counting method often have extremely wide confidence intervals. They can range from 70 to 200 years, and after calibration the interval spans for more than 1000 years (Le-8913: 4270 ± 200 BP or 3505–2342 cal BC; see Figure 3). Besides, there are notable discrepancies between the results from the samples of the same burials produced in different LSC laboratories. For example, differences in the median of 14C years between laboratories of IHMC RAS and the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of SB RAS reached 550 for Tytkesken VI kurgan 95 and 500 for Bersjukta I kurgan 1 (Figure 8 in Polyakov Reference Polyakov2010). Such a discrepancy appears only for human bone samples; no differences have been detected for the wood samples.

As such, at the moment AMS age ranges are the most “narrow.” Fourteen AMS dates obtained for eight Afanasyevo cemeteries all fall within the narrow period of 31st–29th century BC. At the same time, 16 LSC dates for human bones from 10 cemeteries cover a period of more than 1000 years—34th–24th century BC. Despite quite a similar number of determinations, the resulting difference in range is more than three times. For the Middle Yenisei Region, the pattern is not as obvious because of the smaller number of measurements.

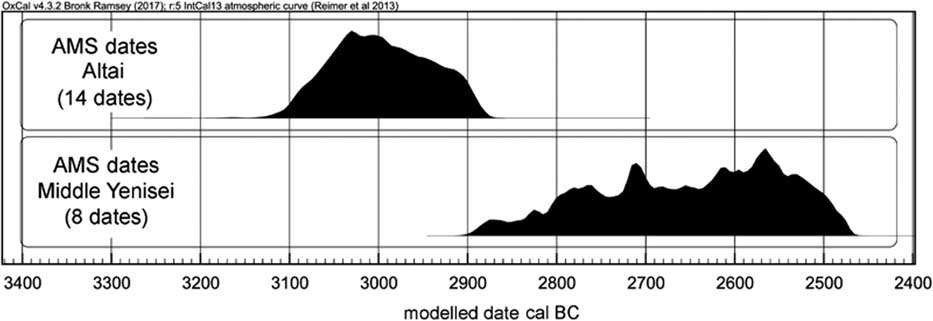

Altai versus Minusinsk Basin Summed Probabilities for AMS 14C Dates

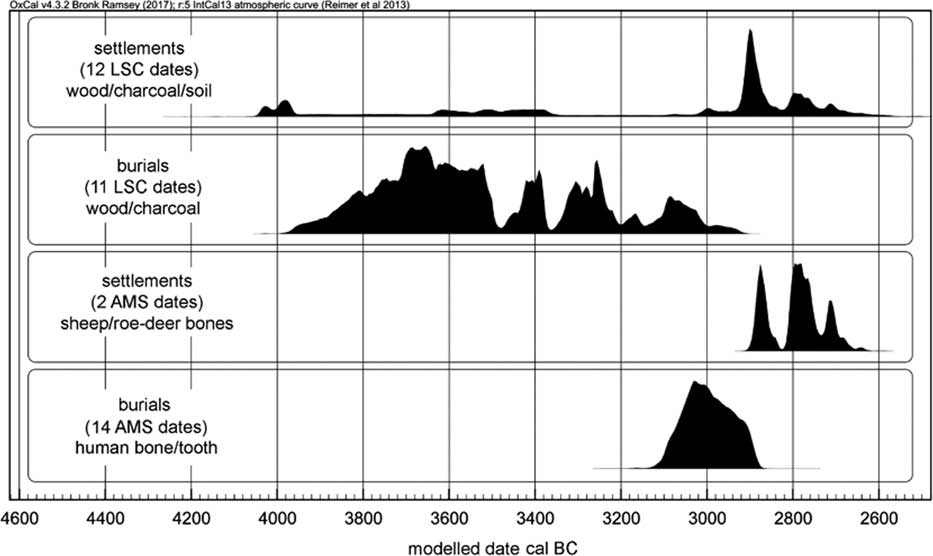

An amazing pattern appears when comparing AMS 14C dates for the Altai and Minusinsk Basin regions—the summed probabilities hardly overlap (Figure 5). The summed probability dates are the 31st to the start of 29th century BC for the Altai sites, and 29th to the start of 25th century BC for the Middle Yenisei (Minusinsk Basin).

Figure 5 Comparison of summed probabilities of calibrated 14C dates for the Afanasyevo sites from different regions.

However, we should not immediately conclude that the Afanasyevo population from the Altai moved to the Middle Yenisei Region, especially since there is no archaeological evidence for this (Stepanova Reference Stepanova2010a). All eight measurements made for the Minusinsk sites have been received from only two typologically close sites of Afanasieva Gora and Karasuk III, which is not enough to represent the full spectrum of the Afanasyevo funerary monuments for this territory. Possibly, over time, the lower chronological boundary for the Minusinsk sites will be extended and early monuments will partly synchronize with the Altai ones. The main conclusion to be made at present is that 14C dating confirms the relatively younger age of the Altai sites.

Settlement versus Burial Dates (Altai Sites)

To date, the 14C measurements for settlement of the Afanasyevo Culture have only been done for the Altai Region, as there is not a sufficient number of settlements analyzed in the Middle Yenisei region. Because of the large number of secondary factors that can affect the provenance of such samples (frost cracks, activity of burrowing animals, mixing of the layers while excavating middens, etc.), especially in multilayer sites, these data should be assessed carefully, considering that completely different samples, wood, charcoal, soil, animal bone were analyzed. At the moment there are 14 14C dates from five Altai settlements available, of which only two are AMS.

Comparison of the summed probabilities of the 14 settlement dates (LSC and AMS) with 14 AMS dates from cemeteries (the latter are all obtained from bones) demonstrates an interesting pattern (Figure 6). Two settlement AMS dates (from herbivore bones), and the majority of the LSC dates (wood, charcoal, bone) are a bit younger than burial dates. Only four out of 12 LSC dates for settlements (SOAN-2744, SOAN-2742, SOAN-2844, SOAN-3802, obtained from, soil, charcoal, and wood samples), are outliers and appear much older; they fall outside of standard deviation in statistical analysis. It is yet difficult to explain this phenomenon. One can only point out that a similar picture appears for other Bronze Age archaeological cultures of this region (Figure 1 in Polyakov and Svyatko Reference Polyakov and Svyatko2009).

Figure 6 Summed probabilities of calibrated 14C dates for the Altai settlements and cemeteries.

Relative Chronology

To understand how the overall picture of the Altai and Middle Yenisei Bronze Age can change after the proposed adjustments to the chronology of the Afanasyevo Culture, we need to involve data from other cultures and individual types of sites.

Altai Sites

Until the formation of the Afanasyevo Culture, the Altai Mountains were inhabited by Neolithic tribes and, apparently, the population of the Bolshoy Mys Culture attributed to the Eneolithic period (Kiryushin Reference Kiryushin1986). Both settlement layers and cemeteries have been explored. 14C measurements of various samples from these sites set the Neolithic dates mainly to the 5th–4th millennium BC (Kiryushin et al. Reference Kiryushin, Kungurov and Stepanova1995; Table 4 in Kungurova Reference Kungurova2005; Kiryushin and Kiryushin Reference Kiryushin and Kiryushin2008; Kiryushin Reference Kiryushin2015). These dates are much older and do not overlap with the chronological boundaries of the Afanasyevo Culture (Kiryushin Reference Kiryushin2015). So far, there are no reliable materials to explore interaction between local Neolithic groups and bearers of the Afanasyevo tradition. Thus, changing the lower chronological boundary of the Afanasyevo Culture does not create new contradictions.

In recent years, new types of sites with distinctive characteristics have been separated within the Afanasyevo Culture (Stepanova Reference Stepanova2010b, Reference Stepanova2012). Among them, the so-called Aragol and Ulita type sites have not yet been 14C dated and cannot be chronologically compared with the other Afanasyevo sites. Yet, a relatively large series of eight LSC dates has been published for the sites of the so-called Kurota type. Comparison with other Afanasyevo dates demonstrates their synchroneity (Figure 7), which also agrees with the archaeological materials.

Figure 7 Summed probabilities for the Afanasyevo Culture and Kurota type sites.

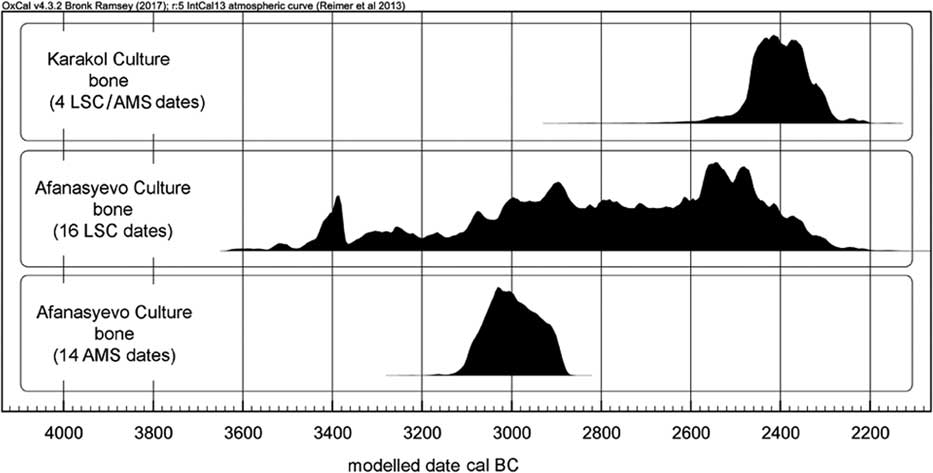

According to the current model, in the Altai Mountains the Afanasyevo was replaced by the Karakol and Elunino cultures. The chronology of the latter is relatively well understood. Based on 34 measurements, it has been dated to the 27th–17th century BC (Kiryushin et al. Reference Kiryushin, Grushin and Papin2009). This agrees well with new AMS data for the chronology of the Afanasyevo Culture. The boundary between the two cultures lies at the turn of the 28th–27th century BC. Much less chronological data has been obtained for the recently identified Karakol Culture—only five dates (one from a charcoal sample, and four from bones) have been produced for the Ozernoye cemetery. Importantly, a situation similar to one for the Afanasyevo Culture can be observed—the LSC date from charcoal is more than 1000 years older than AMS and LSC dates from bones (Figure 8). That is to say that the effect of the older dates from wood/charcoal samples affects not only Afanasyevo, but also the Karakol Culture. Based on the remaining four dates, it should be attributed to the 25th–24th century BC. These data are very preliminary, as only one burial ground has been dated; however, it does not contradict the revised Afanasyevo chronology (Figure 9).

Figure 8 Summed probabilities of the 14C dates of the Ozernoye cemetery (Karakol Culture) by sample type and methods.

Figure 9 Summed probabilities of the 14C dates for the Afanasyevo and Karakol Cultures.

Minusinsk Basin Sites

In the Middle Yenisei Region, the situation appears simpler. Before the emergence of the Afanasyevo Culture, this territory was inhabited by Neolithic tribes whose material culture has still been barely investigated (Vadetskaya Reference Vadetskaya1986). As of today, there are no materials suitable for absolute dating. Therefore, the shift of the lower chronological boundary for the Afanasyevo Culture has no effect on the established timeframe. The upper chronological boundary of the Afanasyevo sites in the Middle Yenisei Region corresponds with the appearance of the Okunevo Culture, and its beginning was previously attributed to the 25th century BC (Polyakov and Svyatko Reference Polyakov and Svyatko2009; Svyatko at al. Reference Svyatko, Mallory, Murphy, Polyakov, Reimer and Schulting2009). The new AMS data do not affect it. Only worth noting are slightly older early dates for Okunevo sites which belong to the 26th century BC. In this regard, it is appropriate to clarify here that currently the chronological boundary between the Afanasyevo and Okunevo Cultures is considered to fall in the 26th–25th century BC, and that the period of their coexistence does not exceed 100 years (Polyakov Reference Polyakov2017).

Mongolian Sites

The only presently dated site of the Afanasyevo Culture in Mongolia is Kurgak-Govi 1. A series of LSC measurements from wooden structures, charcoal and human bones date it to the 29th–26th century BC (Tables 1 and 3 in Kovalev and Erdenebaatar Reference Kovalev and Erdenebaatar2010). No AMS dates are available for this region. The earlier Neolithic population in the area has been barely studied and has no known 14C dates. Relatively later sites are represented by the recently identified Qiemuerqieke (Chemurchek) Culture (Kovalyev Reference Kovalev2012). As of now, tens of sites have already been discovered and the issues similar to the ones revealed in this research have been encountered for them. Specifically, the series of dates obtained from the charcoal and wood samples from the ceilings of burials (first half of the 3rd millennium BC) consistently appear to be older than the dates from human bone samples (second half of the 3rd to beginning of the 2nd millennium BC; Kovalev et al. Reference Kovalev, Erdenebaatar, Zaitseva and Burova2008). Most of the new studies relate the materials of the Qiemuerqieke Culture to the second half of the 3rd to beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. There is an expanding research database that demonstrates the affinity of this culture to the Okunevo and Elunino sites which date to the same time (Kiryushin et al. Reference Kiryushin, Grushin and Papin2009; Kovalev Reference Kovalev2012; Lazaretov Reference Lazaretov2017b; Polyakov Reference Polyakov2017).

It can be ascertained that the newly proposed refined chronology of the Afanasyevo sites is consistent with the established views on the periodisation of the Paleometal period sites of Southern and Western Siberia. In general, our results suggest that the chronology of the Afanasyevo Culture was possibly not the same in different parts of the region. The oldest sites are located in the Altai Mountains, where the sites were apparently abandoned earlier than in other regions. In the Middle Yenisei Region, the Afanasyevo sites probably appeared slightly later, yet the Afanasyevo population could have remained longer in that area. Perhaps the latter situation also happened in the Mongolian Altai, where some sites are 14C dated to the 29th–26th century BC.

CONCLUSIONS

The presented research was aimed to amalgamate and study in detail the entire existing body of 14C data for the Afanasyevo Culture and their correlation with the traditional chronology. The previous “long” chronology of the Afanasyevo Culture was widely criticized and contradicted many observations and conclusions made in the course of extensive archaeological excavations. The detection of the exceedingly wide ranges of the LSC dates from bone samples produced in the laboratories of SB RAS and IHMC RAS, as well as the systematic shift of the data towards an older age for the wood and charcoal samples, finally reveal the shortcomings of the conventional “long” chronology.

Summarizing the research, the following observations can be made:

1. From the AMS data (all from bone samples), the burials of the Afanasyevo Culture of Altai can be dated to the 31st–29th century BC, whereas those of the Middle Yenisei Region to the 29th–25th century BC. As the source database continues to grow, the chronological margins may broaden, i.e., be expanded or corrected.

2. This “narrower” chronology of the Afanasyevo Culture confirms the relatively earlier age of the Altai monuments, as compared to those of the Middle Yenisei Region.

3. Concerning the Altai burials, the LSC dates obtained from the wood samples appear to be systematically older by 250–600 years than the dates from human bone, and this was the reason of the unexplainable extension of the chronology of the Afanasyevo Culture in the area by 1400 years. A similar effect can be suggested in respect to particular Middle Yenisei sites (e.g. Malinoviy Log). The exact origins of this effect are still obscure. The only dated Afanasyevo site in Mongolia (Kurgak Govi-1) does not demonstrate any differences in 14C dates from wood and human bone.

4. The new AMS data for the Afanasyevo burials of Altai appeared to be significantly better clustered (31st–29th century BC) and in a good agreement with the accepted archaeological view of the short-term existence of the Afanasyevo Culture, as compared to the previous LSC results (35th–24th century BC). The new data suggest revision of the conventional “long” chronology of the Afanasyevo Culture, which was the result of very broad confidence intervals of the previous dates and their great scatter, and inconsistency between the results from different laboratories for samples from the same grave, up to the absence of overlap in the obtained dates. A short chronology of the culture removes the contradictions with the archaeological data, explains the small number of sites, the small size of the cemeteries and the lack of the internal periodization. It also removes the inconsistency with the dating of the Yamnaya Culture, which previously appeared “younger” than the Afanasyevo Culture. For the Middle Yenisei sites, the issue is not as evident. If we do not take into account dates from wood, the differences between the AMS and LSC dates from human bone are minimal. Perhaps this is due to the very small number of dates received so far.

5. The existing 14C dates for the Altai settlements exhibit a very large scatter. However, when subjected to statistical screening, they fall in the chronological range of 29th–28th century BC and appear younger than the main body of the AMS dates for the burials. The “younger” 14C dates for settlements (as compared to funeral sites) have been also reported for other archaeological cultures of the region. Further investigations are required to clarify the origins of the phenomenon.

Taking into consideration the whole body of data, we can clearly move towards a different perception. Whereas earlier it was obvious that the Afanasyevo chronology was too broad and possible narrowing was expected, the current situation is the opposite. The new AMS dates only represent a “core” for the Afanasyevo chronology, which cannot be narrowed down. Potentially, in the future, the earlier and later sites will be AMS dated and the chronological borders for the culture will slightly expand over time. Still, the changes will likely be insignificant and will primarily concern the materials from the Altai.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by the Russian State Academies of Sciences program for basic research grants 0184-2018-0009 (“Interaction of the Ancient Cultures of North Eurasia and Eastern Civilisations in the Paleometal Period (4th–1st millennia BC)”) and 0329-2018-0003 (“Historical-Cultural processes in Siberia and surrounding territories”). We are grateful to the reviewers for their very useful comments on the manuscript of this paper.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2018.70