INTRODUCTION

Direct radiocarbon dates of pottery are usually obtained on organic residue preserved on the internal (food crusts) or external (soot, food crusts, coating) vessel surfaces. Such dates are not always reliable, since they can be affected by an old wood effect from wood fuel or by a marine or freshwater reservoir effect from the processing of aquatic resources (e.g. Fischer and Heinemeier Reference Fischer and Heinemeier2003; Boudin et al. Reference Boudin, Van Strydonck, Crombé, De Clercq, van Dierendonck, Jongepier, Ervynck and Lentacker2010; Philippsen Reference Philippsen2013). An alternative way to directly date pottery is by dating the carbon content from the clay (De Atley Reference De Atley1980; Hedges et al. Reference Hedges, Tiemei and Housley1992; Bonsall et al. Reference Bonsall, Cook, Manson and Sanderson2002). This carbon can either derive from organic matter of unknown or “geological” age, that was naturally present in the clay and partially preserved after firing (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Clark, Miller-Antonio, Robins, Schiffer and Skibo1988), from absorbed smoke or soot during firing, with a possible old wood effect, or from organic material that was added to the clay as temper and is often preserved as charred remains in the pottery. To avoid the old carbon content of the clay, and increase the chance of reliable dates, it is better to isolate the charred organic temper remains from the pottery prior to radiocarbon dating (Hedges et al. Reference Hedges, Tiemei and Housley1992; Gomes and Vega Reference Gomes and Vega1999). This method has already been successfully applied to date grass temper (e.g. Bollong et al. Reference Bollong, Vogel, Jacobson, van der Westhuizen and Sampson1993), moss temper (Gilmore Reference Gilmore2015) and accidental inclusions of organic macrofossils in pottery (Arobba et al. Reference Arobba, Panelli, Caramiello, Gabriele and Maggi2017). Gilmore extracted charred remains of Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides) from early fiber-tempered pottery in the southeastern U.S. The nine AMS 14C dates of moss agreed with the expected pottery age and with most paired dates of soot from the same vessel or associated charcoal from the same context.

Moss is used as temper in pottery by diverse cultural groups of the Early and Middle Neolithic periods in northwestern Europe. So far, it has been mostly noticed in 5th to early 4th millennium cal BC pottery of the Cerny, Epi-Rössen, Swifterbant, Chassean and Michelsberg Cultures in northern France, Belgium and the Netherlands (Constantin and Kuijper Reference Constantin and Kuijper2002; Constantin Reference Constantin, Vanmontfort, Louwe Kooijmans, Amkreutz and Verhart2010; Jan and Savary Reference Jan, Savary and Burnez-Lanotte2017), but it is probably already present in La Hoguette pottery and Begleitkeramik of the late 6th millennium cal BC (Constantin Reference Constantin, Vanmontfort, Louwe Kooijmans, Amkreutz and Verhart2010). Moss temper is macroscopically visible as fine (≤ 1 mm wide) curved or rectilinear voids on the vessel surfaces, resulting from the disappearance of organic matter during firing (Figure 1). However, charred moss remains are often preserved in the dark, reduced core area of the vessel and can be identified in ceramic thin sections (Jan and Savary Reference Jan, Savary and Burnez-Lanotte2017; Figure 1).

Figure 1 Above: macroscopically visible moss voids at the surface of Swifterbant pottery from the Scheldt river valley. Below: charred moss remains in thin sections of Swifterbant and Spiere group pottery from the Scheldt river valley (200 × magnification; plane polarized light).

For this study, moss was extracted for AMS 14C dating from Swifterbant Culture (ca. 4500–4000 cal BC) and Spiere group (ca. 4300/4250–3800 cal BC) pottery from different sites in the Scheldt and Lys river valleys in northern Belgium (Figure 2). The moss dates are compared to reference dates of associated organic macro-remains (charred hazelnut shells; charred seeds; charcoal) from these sites and with food crust dates with a probable FRE from the same pottery. Our aim is to assess if moss dates are reliable, as indicated by the pilot study of Gilmore (Reference Gilmore2015) and confirm the presumed FRE of the food crust dates.

Figure 2 Locations of the Swifterbant and Spiere group sites mentioned in the text, in the Scheldt and Lys river area of northern Belgium.

SITES AND SAMPLES

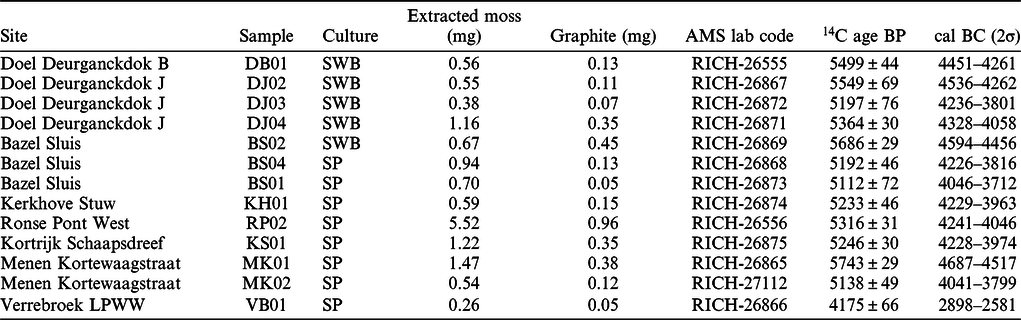

This study includes AMS 14C dates of charred moss remains extracted from five samples of Swifterbant Culture pottery and eight samples of Spiere group pottery, of seven different site locations in the Lys and Scheldt river valleys of northern Belgium (Figure 2; Table 1). The Swifterbant Culture pottery of this area is usually tempered with grog, sometimes combined with moss, whereas a mixed temper of burnt flint and moss is characteristic for pottery of the Spiere group, a regional Middle Neolithic group from the Scheldt river valley, that has affinities with the contemporaneous Michelsberg and Chassean Cultures (Vanmontfort Reference Vanmontfort2001).

Table 1 AMS 14C determinations of moss temper from Swifterbant (SWB) and Spiere group (SP) pottery from the Scheldt and Lys river valleys (Belgium). 14C calibrations are performed using OxCal version 4.3 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) and the IntCal13 calibration curve date (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

Three Swifterbant sites at Doel “Deurganckdok” (called B, J, and M) are firmly dated in the second half of the 5th millennium cal BC, based on radiocarbon dates of organic macro-remains (charred hazelnut shells; charred seeds of blackthorn, common dogwood and guelder rose; charcoal of whitebeam, oak, mistletoe and dogwood) found in association with the cultural remains (Crombé Reference Crombé2005; Boudin et al. Reference Boudin, Van Strydonck, Crombé, De Clercq, van Dierendonck, Jongepier, Ervynck and Lentacker2010; Figure 3). However, a significant number of AMS 14C dates of food crusts from this Swifterbant Culture pottery systematically date in the first half of the 5th millennium cal BC, indicating a FRE due to fish processing in these vessels (Boudin et al. Reference Boudin, Van Strydonck, Crombé, De Clercq, van Dierendonck, Jongepier, Ervynck and Lentacker2010). Four pottery fragments from different vessels with moss temper were selected from sites B and J (samples DB01, DJ02-DJ04). The pottery from site M has almost exclusively grog temper and was not included in this study.

Figure 3 AMS 14C determinations of pottery food crusts (n = 24), moss temper (n = 4) and organic macro-remains (n = 15) for the Swifterbant sites at Doel “Deurganckdok” (B, J, and M). The organic macro-remains include charred shells of hazelnut (Corylus avellana); charred seeds of blackthorn (Prunus spinosa), common dogwood (Cornus sanguinea) and guelder rose (Viburnum opulus); charcoal of mistletoe (Viscum album), whitebeam (Sorbus sp.), oak (Quercus sp.) and dogwood (Cornus sp.).

The site of Bazel “Sluis” is a so-called cumulative palimpsest, with cultural remains (pottery; lithics) and ecofacts (burnt and unburnt animal bone; charred plant remains) of multiple occupation events from the Early Mesolithic to the Middle Neolithic (8th to early 4th millennium cal BC) (Crombé et al. Reference Crombé, Sergant, Perdaen, Meylemans and Deforce2015; Meylemans et al. Reference Meylemans, Perdaen, Sergant, Bastiaens, Crombé, Debruyne, Deforce, Du Rang, Ervynck, Lentacker, Storme and Van Neer2016). As a result of long-lasting bioturbation and trampling, the material remains of these different occupation events have vertically migrated and became mixed, making it difficult to connect AMS 14C dates of organic macro-remains and animal bone with the cultural remains of a specific group or period. The ca. 8000 pottery fragments recovered from this site can mainly be attributed to the Swifterbant Culture and Spiere group, and in smaller numbers to other Early Neolithic (Linear Pottery Culture; Limburg pottery) and Middle Neolithic (Epi-Rössen/Bischheim) cultural groups or pottery traditions (Crombé et al. Reference Crombé, Sergant, Perdaen, Meylemans and Deforce2015). AMS 14C dates obtained on food crusts of grog-tempered Swifterbant pottery from this site situate in the first half of the 5th millennium cal BC (Teetaert et al. Reference Teetaert, Boudin, Saverwyns and Crombé2017). However, these dates are again affected by a FRE due to fish processing, which is confirmed by the identification of fish bones and scales in the residue by microscopic analysis. More recent (unpublished) food crust dates of moss-tempered Swifterbant pottery from this site are situated in both the first and second half of the 5th millennium cal BC. The Spiere group occupation at this site is equally difficult to date due to the mixed palimpsest situation. Most (unpublished) food crust dates of Spiere group pottery from this site are situated in the second half of the 5th or early 4th millennium cal BC, which corresponds to the known age interval of ca. 4300/4250–3800 cal BC for Spiere group sites in northern Belgium (Crombé and Vanmontfort Reference Crombé and Vanmontfort2007; Vanmontfort Reference Vanmontfort2007). Some of these food crust dates however pre-date 4300 cal BC and are likely to have a reservoir age. For this site, one sample of Swifterbant Culture pottery and two samples of Spiere group pottery with moss temper were selected, each with a reference date on food crusts.

The other samples of Spiere group pottery originate from several sites in the Scheldt/Lys river area. In the case of Kortrijk “Schaapsdreef” and Menen “Kortewaagstraat”, the selected pottery comes from dated features: a domed oven structure at Kortrijk, with AMS 14C dates between ca. 4300–4000 cal BC obtained on pottery food crusts, a charred cereal grain and charcoal (Teetaert et al. Reference Teetaert, Baeyens, Perdaen, Fiers, De Kock, Allemeersch, Boudin and Crombé2019); and a water pit at Menen with a radiocarbon date between ca. 4250–4000 cal BC obtained on charcoal of Corylus avellana (KIA-38937: 5300 ± 35 BP; Verbrugge et al. Reference Verbrugge, Dhaeze, Crombé, Sergant, Deforce and Van Strydonck2009). For the samples of Kerkhove “Stuw” (Sergant et al. Reference Sergant, Vandendriessche, Noens, Cruz, Allemeersch, Aluwé, Jacops, Wuyts, Windey, Rozek, Depaepe, Herremans, Laloo and Crombé2016), Ronse “Pont West” (De Graeve et al. Reference De Graeve, Verbrugge and Cherretté2019) and Verrebroek “LPWW” (Perdaen et al. Reference Perdaen, De Loecker, Opbroek and Woltinge2017) no reference dates are available due to the absence of associated organic macro-remains.

Because the sampling is destructive, the selected fragments for moss extraction and dating are usually body fragments, i.e. the least diagnostic parts of the vessel. However, only those fragments are chosen that can be related with certainty to a larger vessel profile or diagnostic rim fragment, either because the fragments can be refitted or because of their common fabric and context. The presence of charred moss remains in each of these pottery types has been confirmed in advance by petrographic analysis of the selected sherds or sherds of the same vessel/fabric. Except for the pottery of Ronse “Pont West” that contains abundant charred moss remains visible by the naked eye.

METHODS

The selected pottery fragments, including relatively small (<15 cm2 surface) and larger sherds, are first broken by hand over aluminum foil. Because the moss contracted by water loss during the initial firing of the pottery, creating a void between the charred plant fragment and its clay container, the remains are often quite easily isolated during breaking of the sherd. Sometimes it is necessary to tap the broken sherd onto the table to free the moss. Although small, the moss remains can be quite easily recognized with the naked eye by their specific shape: <1 mm thick and a few mm long charred “twigs”, often with small branches. A stereo microscope (×20 magnification) is sometimes used to confirm that the plant remains are of moss, and in the case of doubt these remains are excluded from the sample. The charred moss remains that are isolated in this way are manually sampled, using a pincer, and stored in glass vials. This extraction method is time-consuming and only yields small sample sizes. On more than one occasion, multiple sherds of the same vessel had to be broken to collect enough moss for AMS 14C dating (a minimum of 0.25 mg). It is noted that combining moss from different sherds to make up a sufficiently large sample creates “bulk samples”, i.e. different components may be of different dates and the obtained radiocarbon age will be an average. However, by only sampling sherds of the same vessel, it can be assumed that the moss will be of a similar age.

The moss samples are transferred in tin-cups, with 1% HCL added to remove carbonates (for one hour), rinsed with Milli-Q water and dried in the oven at 60°C. At the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage in Brussels (RICH), normally acid-alkali-acid (AAA) is used as pretreatment for organic samples at 90°C. However, this method cannot be applied here, because tests on moss with AAA resulted in too large a sample loss, a problem that is also indicated by Gilmore (Reference Gilmore2015). Following Gilmore, we assume that the alkali (NaOH) treatment is not necessary here, because the moss is encased in the clay container, which lowers the chance of post-depositional contamination by humic substances. This will be further investigated in future research. For now, we assume that the HCL-pretreatment, used to remove calcite, is sufficient. After pretreatment, the moss samples are transformed into graphite using the automatic graphitization device AEG (Němec et al. Reference Němec, Wacker and Gäggeler2010; Wacker et al. Reference Wacker, Němec and Bourquin2010). 14C concentrations are measured with accelerated mass spectrometry (AMS) at RICH (Boudin et al. Reference Boudin, Van Strydonck, Van den Brande, Synal and Wacker2015). As the sample sizes are small, standards (oxalic acid II), control standards (FIRI D, IAEA-C5) and blanks (interglacial wood) were prepared in the same magnitude as a means to obtain good measurements. 14C results are expressed in pMC (percentage modern carbon) and indicate the percentage of modern (1950) carbon corrected for fractionation using the δ13C AMS measurement. 14C calibrations are performed using OxCal version 4.3 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) and the IntCal13 calibration curve date (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Swifterbant Culture

The AMS 14C determinations of charred moss remains from Swifterbant Culture pottery are presented in Table 1. All five moss dates are within the expected age interval of ca. 4500–4000 cal BC (2σ), with sample BS02 possibly dating slightly before 4500 cal BC and sample DJ03 possibly dating slightly after 4000 cal BC. Standard deviations of uncalibrated BP ages are quite high due to the small sample sizes, but they are ±30 14C yr for samples yielding ≥ 0.30 mg of graphite. However, samples yielding between 0.12 and 0.15 mg of graphite gave uncertainties of less than 50 14C yr and are still useful.

Figure 3 compares all available AMS 14C dates for the Swifterbant sites at Doel “Deurgancdok”, with 24 food crust dates, four moss dates and 15 dates of organic macro-remains found in association with the Swifterbant cultural remains. Whereas the food crusts systematically date in the first half of the 5th millennium cal BC, most likely due to a freshwater reservoir effect (Boudin et al. Reference Boudin, Van Strydonck, Crombé, De Clercq, van Dierendonck, Jongepier, Ervynck and Lentacker2010), the charred moss remains preserved inside this pottery date in the second half of the 5th millennium cal BC, which is in agreement with the dates of organic macro-remains.

The moss date of Swifterbant Culture pottery from Bazel “Sluis” (BS02) is compared to a date obtained on food crusts of the same sherd (Table 2). Both dates are close to one another, but without overlap. The moss temper dates even slightly older than the food crusts, which is hard to explain and makes it difficult to interpret the reliability of both dates. A reservoir effect of the moss date, related to the use of aquatic moss as temper, cannot be excluded (see below).

Table 2 Comparison of AMS 14C determinations of moss temper with reference dates of food crusts or of associated organic macro-remains. For the paired dates of each sample a χ2-test (Ward and Wilson Reference Ward and Wilson1978) is performed to establish their consistency

Spiere Group

The AMS 14C determinations of charred moss remains from the Spiere group pottery are presented in Table 1. Six out of eight dates are within the expected age interval of ca. 4300/4250–3800 cal BC (2σ) (Figure 4). Sample MK01 dates a few hundred 14C yr too old and sample VB01 dates approximately 1000 14C yr younger than the expected pottery age. The latter could be related to the very small sample size of moss remains, yielding only 0.05 mg of graphite. For such a small target it is hard to quantify how much contamination can be expected.

Figure 4 AMS 14C determinations of moss temper from Spiere group pottery of sites in the Scheldt and Lys river valleys. The expected age interval for Spiere group sites in this area is indicated by the green column. (Please see electronic version for color figures.)

Five moss dates of Spiere group pottery can be compared to reference dates of food crusts of the same sherd or organic material of the same context or layer (Table 2). Again, the moss dates often do not overlap with the reference dates. For samples BS01 and BS04, the moss dates fit the expected pottery age, but the food crusts of the same sherds date several hundred 14C yr too old and very likely have a reservoir effect. MK01 and MK02 represent two moss dates from the same vessel, but they are several hundred 14C yr apart from each other. The date of MK02 fits perfectly within the expected age interval and seems most reliable. Yet it deviates slightly from the reference date on charcoal of Corylus avellana from the same context (a water pit or well). The charcoal was retrieved from the bottom of the pit, while the potsherds were found in two separate layers in the lowest infilling (Verbrugge et al. Reference Verbrugge, Dhaeze, Crombé, Sergant, Deforce and Van Strydonck2009). Possible explanations for the slightly deviant dates are a long use period for the water pit or an old wood effect for the charcoal date. The reason for the too old date of MK01 is unclear, but it could be related to a moss reservoir effect from the use of aquatic moss as temper (see below). Sample KS01 fits the expected pottery age and corresponds with the reference date of pottery food crusts from the same layer of the oven structure. Both dates are slightly younger than that of a carbonized cereal grain recovered at the bottom of this layer. This makes sense, since the cereal grain could be related to the use of the oven to dry cereals (Teetaert et al. Reference Teetaert, Baeyens, Perdaen, Fiers, De Kock, Allemeersch, Boudin and Crombé2019), while the pottery with food crusts is interpreted as settlement waste and is related to the infilling of the oven after its final use. The link between the moss and food crust dates is more important here, since both are directly related to the pottery.

For the sites of Kerkhove (KH) and Ronse (RP) no reference dates are available, yet the moss dates can be considered reliable since they are in full agreement with the expected pottery age (Figure 4). With an expected age between ca. 4300/4250–3800 cal BC, a deviation of 100–200 14C yr remains however possible. In any case, it illustrates the potential of moss temper as a dating material for sites which are otherwise “undatable” due to the lack of associated organic material.

Moss Dates, Reservoir Effect and “Old Moss Effect”

As illustrated by the AMS 14C dates of Swifterbant Culture pottery from Doel “Deurganckdok” and from Spiere group pottery from Bazel “Sluis” (samples BS01, BS04), moss temper is more reliable as a direct dating material for pottery opposed to food crusts with a possible reservoir effect. However, moss can also contain a reservoir age, already before it is harvested and used as temper. 14C dates of moss are often used to establish chronologies for lake sediments. These studies have demonstrated an important difference in the reliability of AMS 14C dates between terrestrial and aquatic moss. While terrestrial mosses almost exclusively take up atmospheric CO2 during photosynthesis and give reliable dates (e.g. Shen et al. Reference Shen, Liu, Yi, Sun, Jiang, Beer and Bonani1998), aquatic (submerged or emergent) mosses can also take up reservoir-aged dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), yielding radiocarbon dates that can be up to 6000 14C yr too old (e.g. MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Beukens, Kieser and Vitt1987; Madeja and Latowski Reference Madeja and Latowksi2008). Therefore, aquatic moss is considered unsuitable for radiocarbon dating (Philippsen Reference Philippsen2013; Marty and Myrbo Reference Marty and Myrbo2014). These studies stress the importance of moss identification prior to dating.

Moss that is used as temper in Epi-Rössen pottery of northern France and Belgium is already partially identified as the terrestrial moss species Neckera crispa Hedw. (Constantin and Kuijper Reference Constantin and Kuijper2002). For our study, the too old 14C dates of BS02 and MK01 compared to their reference dates could be explained by a moss reservoir effect due to the use of aquatic moss. From previous studies including radiocarbon dates of fish remains and pottery food crusts, it appears that the FRE offset for the Scheldt river basin can range from 100 to almost 2000 14C yr (Boudin et al. Reference Boudin, Van Strydonck, Crombé, De Clercq, van Dierendonck, Jongepier, Ervynck and Lentacker2010; Teetaert et al. Reference Teetaert, Boudin, Saverwyns and Crombé2017; Ervynck et al. Reference Ervynck, Boudin and Van Neer2018). For the remaining moss dates, with no apparent FRE, the use of only terrestrial mosses as temper can be expected. Archaeobotanical analysis of moss remains from the dated pottery is planned in the near future.

Alternatively, the risk of an “old moss effect” cannot be entirely excluded. Moss could have grown at the clay extraction site decades or centuries before the clay was dug up. During petrographic analysis of Neolithic pottery from the Scheldt river valley, very small amounts of charred moss or related voids have been observed in pottery that does not seem to be tempered with moss. This could point to the presence of some old moss in the extracted clays. However, in the case of pottery with abundant moss remains, for which the addition of moss as temper is obvious, we can assume that at least most of the extracted remains for AMS 14C dating are chronologically related to the time of pottery production.

CONCLUSIONS

The AMS 14C dates of charred moss remains from Swifterbant and Spiere group pottery appear to be largely reliable, since 11 out of 13 moss dates correspond to the expected pottery age. This study confirms the potential of moss temper as a direct dating material for pottery, in particular for Neolithic pottery of northwestern Europe. It yielded seemingly reliable dates for sites lacking any other datable material, as well as for sites where the direct dating of pottery is complicated by a reservoir age of the food crusts.

However, moss temper can also have a reservoir age if aquatic moss was used. This could be the case for some samples in this study. The differences between moss dates and their reference dates can be hard to explain. Therefore, more research regarding the reliability of moss dates is necessary. Future research will include (a) experiments with different extraction methods to enhance sample sizes, (b) multiple dates of mosses from the same vessel to test the consistency of these dates, (c) more samples with reference dates, and (d) moss identification prior to dating to distinguish between terrestrial and aquatic plants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research is a collaboration between the department of Archaeology of Ghent University, the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage and the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. Part of this research is funded by the Special Research Fund (BOF) of Ghent University. We would like to thank all colleagues from archaeological institutions and companies who provided samples for this research.