INTRODUCTION

The Bronze Age of the southern Levant featured the emergence of fortified towns, followed by their dramatic abandonment and redevelopment during the 4th and 3rd millennia BC. Sedentary agrarian settlements and their populations alternately aggregated or dispersed according to a variety of trajectories (Falconer and Savage Reference Falconer and Savage1995, Reference Falconer and Savage2009). Occasional walled communities in Early Bronze I (Joffe Reference Joffe1993; Gophna Reference Gophna1995; Philip Reference Philip2003) preceded more nucleated settlement in the subsequent Early Bronze II and III periods, as signaled by the advent of numerous fortified towns atop mounded tell sites throughout the region (Greenberg Reference Greenberg2002, Reference Greenberg2014; de Miroschedji Reference de Miroschedji2009, Reference de Miroschedji2014). These towns were abandoned gradually across the southern Levant by the end of Early Bronze III and populations shifted to farming hamlets and seasonal pastoral encampments during Early Bronze IV (also known as the Intermediate Bronze Age) (Palumbo Reference Palumbo1991; Dever Reference Dever1995; Cohen Reference Cohen2009; Prag Reference Prag2014). Subsequently, larger walled cities reappeared rapidly in Middle Bronze I (traditionally termed Middle Bronze IIA), growing in size, number, and scale of fortification during Middle Bronze II and III (Middle Bronze IIB and IIC) (Greenberg Reference Greenberg2002; Bourke Reference Bourke2014; Cohen Reference Cohen2014). The Late Bronze Age experienced a recession in the abundance and size of Levantine towns (Fischer Reference Fischer2014; Panitz-Cohen Reference Panitz-Cohen2014), although the period witnessed heightened commercial and political activity throughout the eastern Mediterranean, as well as the earliest textual documentation of local Levantine polities (Strange Reference Strange2000; Savage and Falconer Reference Savage and Falconer2003; Falconer and Savage Reference Falconer and Savage2009).

The relative chronology and periodization of the southern Levantine Bronze Age have been derived traditionally from systematic changes in material culture within the Levant (especially in ceramic vessel morphology) and linkages of local material culture (e.g. pottery and metal weaponry) with typological parallels in Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt (Cohen Reference Cohen2002, Reference Cohen2014; Bourke Reference Bourke2014; de Miroschedji Reference de Miroschedji2014; Prag Reference Prag2014; Richard Reference Richard2014). This chronology is anchored in absolute terms with particular reference to the dynastic chronology of Egypt. For example, the end of Early Bronze I is correlated with the end of Egypt’s Dynasty 0 between 3025 and 2950 BC (Stager Reference Stager1992; Greenberg Reference Greenberg2002; Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Rowland, Higham, Harris, Brock, Quiles, Wild, Marcus and Shortland2010; de Miroschedji Reference de Miroschedji2014; Sharon Reference Sharon2014). Similarly, the ascension of the 12th Dynasty has provided the chronological lynchpin for the orthodox beginning of the Levantine Middle Bronze Age at 2000 BC (Dever Reference Dever1987; Stager Reference Stager1992; Greenberg Reference Greenberg2002).

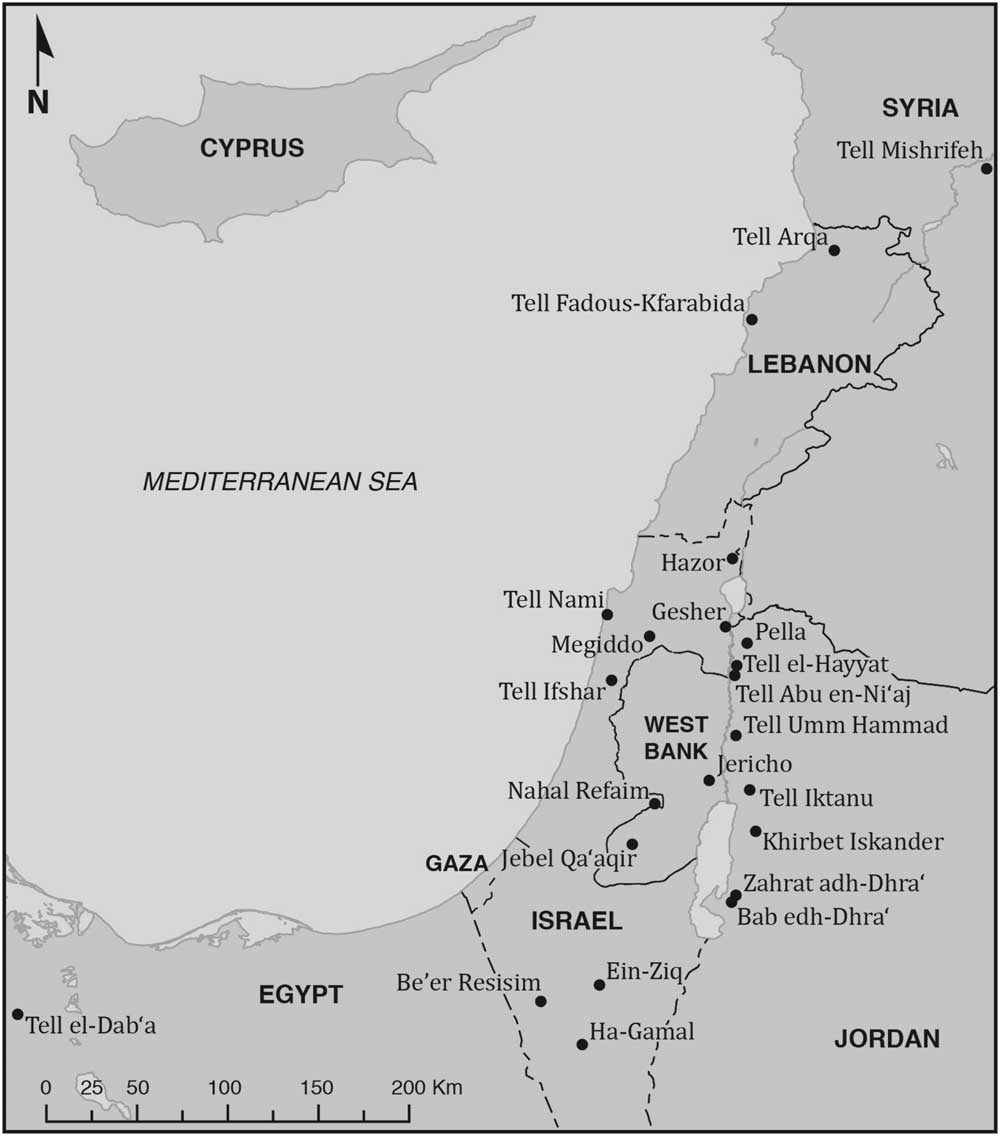

Traditionally, Early Bronze IV town abandonment has been correlated with the collapse of central political authority during the Egyptian First Intermediate Period, and sandwiched accordingly between the Old and Middle Kingdoms from 2300 to 2000 BC (Stager Reference Stager1992; Dever Reference Dever1995; Prag Reference Prag2014). This convenient linkage, however, risks a potential tautology in using Egyptian political history to first date and then explain the social dynamics of the southern Levant (for a similar argument from an Egyptian perspective see Bruins Reference Bruins2007: 65). This critique is particularly appropriate for the previously accepted 2- to 3-century Early Bronze IV chronology at the end of the 3rd millennium BC. This study presents new accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) 14C sequences from Early Bronze IV Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj and Middle Bronze Age Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1, Jordan, which we relate to published chronological evidence from the southern Levant, Lebanon, and Egypt (Figure 1). On this basis, we introduce detailed evidence for a lengthened southern Levantine Early Bronze IV period starting between 2600 and 2500 cal BC and continuing to ~2000 cal BC.

Figure 1 Map of the eastern Mediterranean, including the southern Levant (modern Israel, Palestine, and western Jordan) and the Early Bronze IV and Middle Bronze Age sites incorporated in this study.

Levantine Bronze Age chronologies and their correlation with evidence from Egypt, Lebanon, and Syria have attracted considerable critical review over the last decade. Reconsideration and modeling of Early Bronze Age 14C dates from sites across the southern Levant (e.g. Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht2001; Golani and Segal Reference Golani and Segal2002; Braun and Gophna Reference Braun and Gopha2004; Philip Reference Philip2008; Bourke et al. Reference Bourke, Zoppi, Hua, Meadows and Gibbins2009; Regev et al. Reference Regev, de Miroschedji, Greenberg, Braun, Greenhut and Boaretto2012a, Reference Regev, de Miroschedji and Boaretto2012b, Reference Regev, Finkelstein, Adams and Boaretto2014; Shai et al. Reference Shai, Greenfield, Regev, Boaretto, Eliyahu-Behar and Maeir2014) hinge on stratified evidence excavated from settlements spanning Early Bronze I–III. These investigations support a revised chronological structure that is significantly earlier than traditionally accepted timeframes. For example, the Early Bronze II/III transition may be revised “at least 200 yr earlier than the traditionally accepted dates” (Regev et al. Reference Regev, de Miroschedji, Greenberg, Braun, Greenhut and Boaretto2012a: 561). These studies also allude to an early beginning for Early Bronze IV, based primarily on the unexpectedly early end of Early Bronze III, which implies a start for Early Bronze IV no later than ~2450 cal BC (e.g. Regev et al. Reference Regev, de Miroschedji, Greenberg, Braun, Greenhut and Boaretto2012a: 561). In particular, the limited number of Early Bronze III/IV sites with clearly stratified 14C ages hinders modeling of the beginning of Early Bronze IV.

The traditional end date for Early Bronze IV remains tied to the expected date for the Early Bronze/Middle Bronze transition ~2000 BC. Comparative studies of 14C ages from Middle Bronze Age settlements estimate the beginning of Middle Bronze I at or slightly later than this orthodox date (e.g. Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht1995, Reference Bruins and van der Plicht2003; Marcus Reference Marcus2003, Reference Marcus2010, Reference Marcus2013; Bourke Reference Bourke2006; Fischer Reference Fischer2006; Bruins Reference Bruins2007; Bourke et al. Reference Bourke, Zoppi, Hua, Meadows and Gibbins2009; Kutschera et al. Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetsky, Stadler, Seier, Thanheiser and Weninger2012; cf. H��flmayer et al. Reference Höflmayer, Kamlah, Sader, Dee, Kutschera, Wild and Riehl2016). However, the current Early Bronze IV chronology remains unmodeled internally and accordingly may encompass anywhere from 200 to >500 yr as inferred indirectly from preceding and subsequent periods. The difficulty in defining the boundaries of Early Bronze IV results largely from a dearth of high-resolution 14C ages from Early Bronze III/IV sites and the near absence of Early Bronze IV/Middle Bronze I stratified sites in the southern Levant. The key challenges in redefining chronology through the full course of Early Bronze IV stem from this period’s paucity of excavated settlements and, more specifically, the absence of 14C ages from long-term stratigraphic sequences comparable to those available from stratified Early Bronze I–III and Middle Bronze Age sites. This study presents a seven-phase sequence of 24 AMS seed dates from the excavated agrarian settlement of Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj, Jordan, that pushes the start of Early Bronze IV earlier than proposed previously, approaches the earliest Middle Bronze dates from neighboring Tell el-Hayyat and more distant Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1, and covers an intervening span of at least 500 yr through Early Bronze IV.

TELL ABU EN-NI‘AJ

Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj extends over 2.5 ha and lies at ~250 m below sea level in the northern Jordan Valley, where it overlooks the present floodplain of the Jordan River (Figure 1; Ibrahim et al. Reference Ibrahim, Sauer and Yassine1976: 51, site 64). Judging from population densities in traditional Middle Eastern villages (generally 200–250 people/ha, see e.g. Kramer Reference Kramer1982), we estimate that Ni‘aj housed 500 to 600 inhabitants in Early Bronze IV. Excavations at Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj directed by the authors in 1985, 1996/97, and 2000 (Falconer and Magness-Gardiner Reference Falconer and Magness-Gardiner1989; Falconer et al. Reference Falconer, Fall and Jones1998, Reference Falconer, Fall and Jones2001, Reference Falconer, Fall, Metzger and Lines2004, Reference Falconer, Fall and Jones2007; Falconer and Fall Reference Falconer and Fall2009) covered about 2.5% of the site area (Figure 2; Falconer et al. Reference Falconer, Fall, Metzger and Lines2004: Figure 4), exposing 3.3 m of Early Bronze IV cultural deposits comprised of seven major strata of mudbrick architecture. The walls of Phase 7 structures, at the base of this sequence, are founded on archaeologically sterile Pleistocene lacustrine sediments. Phase 1 deposits incorporate ancient village remains just below the tell’s modern surface. The village plan of Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj is marked by closely packed mudbrick domestic and industrial structures separated by alleyways and, in Phases 5–1, sherd paved streets (Figure 3). In keeping with the original report of the East Jordan Valley Survey (Ibrahim et al. Reference Ibrahim, Sauer and Yassine1976), the excavated ceramics from Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj Phases 7–1 consist of characteristically fine-tempered hand-built Early Bronze IV vessels, which attest to the village’s occupation solely in Early Bronze IV. Thus, Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj provides a rare excavated example of a deeply stratified sedentary Early Bronze IV community.

Figure 2 Topographic map of Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj, Jordan showing 4×4 m excavation units in Fields 1–4. 14C dates come from Field 4, Units B, C, GG, K, W, & X. The main site datum is ~250 m below sea level.

Figure 3 Excavated Phase 2 Early Bronze IV architecture in Field 4 at Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj, Jordan, showing mudbrick structures, sherd-paved streets, pits, clay-lined bins, and stone pavements.

We compare the 14C sequence from Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj to dates from other Early Bronze IV sites in the southern Levant, Lebanon, and Egypt as a means of expanding and detailing this period within emerging revised Bronze Age chronologies. We also explore the end of Early Bronze IV with reference to Middle Bronze Age 14C ages from the southern Levant and Egypt, especially early Middle Bronze I dates from Tell el-Hayyat and Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1, Jordan.

TELL EL-HAYYAT

Tell el-Hayyat lies 1.5 km northeast of Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj, at ~240 m below sea level amid agricultural fields on the alluvial terrace above the Jordan River floodplain (see Figure 1; Ibrahim et al. Reference Ibrahim, Sauer and Yassine1976:49, site 56). This 0.5-ha settlement was inhabited by 100–150 people over the course of the Middle Bronze Age. Excavations in 1982, 1983, and 1985 (Falconer Reference Falconer1995; Falconer and Fall Reference Falconer and Fall2006) sampled about 8% of the site area and unearthed deposits almost 4 m deep that incorporate six stratified architectural phases (Falconer and Fall Reference Falconer and Fall2006: Figure 2.3). Basal Phase 6 produced Early Bronze IV ceramics from archaeological deposits just above sterile sediment. Phases 5–2 reveal a Middle Bronze Age settlement centered on four temples in antis surrounded by houses, courtyards, and alleys (Magness-Gardiner and Falconer Reference Magness-Gardiner and Falconer1994; Falconer and Fall Reference Falconer and Fall2006: Figure 3.1). Hand-built versions of Middle Bronze I vessel forms suggest that Phase 5 dates early in this period, while classic wheel-thrown pottery documents Middle Bronze I, II, and III habitation in Phases 4–2 (Falconer and Fall Reference Falconer and Fall2006: Table 4.1). Phase 1 provides fragmentary architectural remains of the village’s final occupation in Middle Bronze III.

ZAHRAT ADH-DHRA‘ 1

Middle Bronze Age Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1 on the Dead Sea Plain is distinguished by the remains of more than 25 semi-subterranean stone built structures spread over 6 ha atop a ridge between two tributaries of the Wadi al-Karak (see Figure 1; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Falconer, Fall, Berelov, Davies, Meadows, Meegan, Metzger and Sayej2001, Reference Edwards, Falconer, Fall, Berelov, Czarzasty, Day, Meadows, Meegan, Sayej, Swoveland and Westaway2002; Fall et al. Reference Fall, Falconer and Edwards2007). Eroded buildings along these wadis suggest an original settlement of at least 12 ha that has been truncated by post-Bronze Age downcutting. Field investigations directed by the authors in 1999/2000 utilized 23 excavation units to sample domestic remains across the site (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Falconer, Fall, Berelov, Davies, Meadows, Meegan, Metzger and Sayej2001; Fall et al. Reference Fall, Falconer and Edwards2007). Ceramic typology and inference of abandonment patterns suggest multiple episodes of occupation and abandonment in the Middle Bronze Age (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Falconer, Fall, Berelov, Czarzasty, Day, Meadows, Meegan, Sayej, Swoveland and Westaway2002; Berelov Reference Berelov2006).

METHODS

As a routine excavation method at Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj, Tell el-Hayyat, and Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1, archaeological sediments with visible burned organic content were processed by water flotation to recover plant macrofossils (Fall et al. Reference Fall, Lines and Falconer1998, Reference Fall, Falconer and Lines2002; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Falconer, Fall, Berelov, Davies, Meadows, Meegan, Metzger and Sayej2001; Falconer and Fall Reference Falconer and Fall2006:38–43; Klinge and Fall Reference Klinge and Fall2010; Klinge Reference Klinge2013). These samples were recovered from shallow well-defined features with burned sediments (e.g. small hearths, shallow pits in surfaces). The floated organic fraction from each sample, containing carbonized seeds and charcoal, was poured through nested 4.75-mm, 2-mm, 1-mm, and 0.5-mm mesh sieves. All material 0.5 mm or larger was sorted under a binocular microscope to separate charred seeds from charcoal fragments (see detailed methods in Klinge and Fall Reference Klinge and Fall2010: 38–43). Seeds and seed fragments were identified using Fall’s personal reference collection and comparative literature (e.g. Helbaek Reference Helbaek1958; Renfrew Reference Renfrew1973; Zohary and Hopf Reference Zohary and Hopf1973; Zohary and Spiegel-Roy Reference Zohary and Spiegel-Roy1975; van Zeist Reference van Zeist1976; Hillman Reference Hillman1978; van Zeist and Bakker-Heeres Reference van Zeist and Bakker-Heeres1982; Hubbard Reference Hubbard1992; Jacomet Reference Jacomet2006). We submitted seeds representing short-lived cultigens (rather than charcoal) from Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj, Tell el-Hayyat, and Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1 for AMS 14C analysis in order to optimize chronological resolution.

A set of 24 14C age determinations from Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj samples now contributes to the ongoing resolution of Bronze Age chronology in the southern Levant. A group of seed samples from upper phases at Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj produced three age determinations from the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Higham, Owen, Pike and Hedges2002) and four ages from the Vienna Environmental Research Accelerator (previously unpublished) as part of a 14C-based study of the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age conducted by Ezra Marcus (Reference Marcus2003, Reference Marcus2010). Seed samples submitted more recently to the University of Arizona Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory have produced 17 further age determinations (previously unpublished). The current suite of ages now covers the entire stratigraphic sequence at Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj (Phases 7–1; Table 1).

Table 1 AMS radiocarbon results for seed samples from Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj, Jordan (ordered by lab and sample number). Calibration based on OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013) using the IntCal13 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). Stratigraphic phases at Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj start with Phase 7 (the earliest, basal stratum) and end with Phase 1 (the latest, uppermost stratum). Context is indicated according to Excavation Unit, Locus, and Bag (e.g. C.066.239=Unit C, Locus 066, Bag 239).

14C analyses for seed samples from Tell el-Hayyat Phases 5 and 4 include four AMS ages from the University of Arizona (Falconer and Fall Reference Falconer and Fall2006: Table 4.2; Marcus Reference Marcus2003, Reference Marcus2010), which were followed by four determinations from Oxford, and five ages from the VERA lab (Marcus Reference Marcus2010). These dates address the beginning of MB I based on evidence recovered in close proximity to Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj. A suite of six previously unpublished seed dates from the ANTARES AMS Facility at ANSTO documents the span of Middle Bronze Age occupation at Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1, including 14C ages early in Middle Bronze I.

All 14C ages in this study were calibrated using OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013) and the IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). The modeling tools in OxCal v 4.2.4 were used for Bayesian analysis of the calibrated dates. Bayesian analysis of 14C ages enables the coordinated analysis of large suites of calibrated 14C determinations, which are becoming increasingly common in archaeology (see especially Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a). Further, it accommodates the non-normally distributed probabilities of calibrated 14C ages, and provides a means for archaeologists to build modeled 14C sequences on prior stratigraphic information.

RESULTS

Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj

Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj provides a sequence of 24 seed dates spread over seven stratigraphic phases (Table 1). We organized these dates in a series of contiguous phases based on the uninterrupted stratigraphic record of occupation at Ni‘aj; within each phase dates were ordered from older to younger based on 14C ages. Bayesian modeling suggests a starting boundary for Phase 7 with a 1σ range of 2591–2486 cal BC and an ending boundary range for Phase 1 of 2118–1970 cal BC (Figure 4). After removal of two outliers (AA-90067; AA-90071) (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009b), the Amodel=122.7. Removal of these outliers caused minimal shifts in modeled boundaries (<10 yr change in medians). This model generates an occupation span of ~500 yr or roughly 70–75 yr per phase. On this basis, each of the earlier strata (Phases 7–3) represents about 35–55 yr of habitation (as estimated by differences between boundary medians), while Phases 2 and 1 reflect longer episodes of roughly 150 yr each. In overview, Bayesian modeling suggests that the Early Bronze IV occupation at Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj began 2600–2500 cal BC and ended 2100–2000 cal BC.

Figure 4 Bayesian sequencing of 14C dates for seed samples from Phases 7–1 at Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj, Jordan. Light gray curves indicate single-sample calibration distributions; dark curves indicate modeled calibration distributions. Calibration and Bayesian modeling based on OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a; Bronk Ramsey 2013 and Lee) using the IntCal13 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

Tell el-Hayyat

Thirteen seed dates span Phases 5 and 4 at Tell el-Hayyat (Table 2). We assembled these ages in two contiguous phases within which dates were ordered from older to younger on the basis of 14C determinations. Bayesian modeling suggests a starting boundary for Phase 5 with a 1σ range of 1937–1823 cal BC and an ending boundary range for Phase 4 of 1835–1759 cal BC (Figure 5). The first samples submitted from Tell el-Hayyat produced relatively large uncertainties, and when three of them (AA-1237, AA-1238, AA-1239) are treated as outliers, Amodel=119.8. This model estimates an occupation span of about 100 yr for these two phases, in which Phase 5 began around 1900 cal BC and Phase 4 ended about 1800 cal BC.

Figure 5 Bayesian sequencing of 14C dates for seed samples from Phases 5 and 4 at Tell el-Hayyat, Jordan. Light gray curves indicate single-sample calibration distributions; dark curves indicate modeled calibration distributions. Calibration and Bayesian modeling based on OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a; Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013) using the IntCal13 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

Table 2 AMS radiocarbon results for seed samples from Tell el-Hayyat, Jordan (ordered by lab and sample number). Calibration based on OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013) using the IntCal13 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). Stratigraphic phases at Tell el-Hayyat start with Phase 6 (earliest, basal stratum) and end with Phase 1 (latest, uppermost stratum). Context is indicated according to Excavation Unit, Locus, and Bag (e.g. F.049.288=Unit F, Locus 049, Bag 288).

Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1

Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1 contributes six new seed dates from three structures across the site (Table 3). Unlike the stratified deposits at Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj and Tell el-Hayyat, the samples from Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1 come from dispersed, nonstratified contexts in five different stone walled rooms. Therefore, we did not model these dates in separate phases, although patterns of structural abandonment and ceramic deposition suggest multiple habitation episodes (e.g. Berelov Reference Berelov2006; Fall et al. Reference Fall, Falconer and Edwards2007). When compared with ceramic assemblages from settlements closer to Middle Bronze Age towns, the rather idiosyncratic pottery repertoire from marginally located Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1 led us to infer occupation primarily in Middle Bronze I and II (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Falconer, Fall, Berelov, Czarzasty, Day, Meadows, Meegan, Sayej, Swoveland and Westaway2002; Berelov Reference Berelov2006; Fall et al. Reference Fall, Falconer and Edwards2007). Bayesian modeling of the 14C ages from Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1 generates a starting boundary with a 1σ range of 2163–1952 cal BC and an ending boundary range of 1657–1438 cal BC (Figure 6; Amodel=92.0). Thus, the 14C evidence suggests occupation at Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1 at a series of points over the entire traditional range of the Middle Bronze Age between 2000 and 1500 cal BC.

Figure 6 Bayesian phase model of 14C dates for seed samples from Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1 (ZAD 1), Jordan. Light gray curves indicate single-sample calibration distributions; dark curves indicate modeled calibration distributions. Calibration and Bayesian modeling based on OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a; Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013) using the IntCal13 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

Table 3 AMS radiocarbon results for seed samples from Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1, Jordan (ordered by lab and sample number). Calibration based on OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013) using the IntCal13 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). Context is indicated according to Excavation Unit, Locus, and Bag (e.g. I.012.72=Unit I, Locus 012, Bag 72).

Comparative Evidence for Early Bronze IV

The stratified sequence of habitation and 14C ages from Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj links a limited number of possibly earlier dates at the beginning of Early Bronze IV with a larger array of dates from later Early Bronze IV contexts elsewhere in the southern Levant and at key sites in Lebanon and Egypt (Figure 7). All of the 14C determinations from the other southern Levantine Early Bronze Age sites derive from charcoal samples, except for three ostrich eggshell samples from Be’er Resisim (Table 4). The earliest ages from Ni‘aj slightly predate the first dates from a variety of locales, including Nahal Refaim in the Levantine Hill Country, Khirbet Iskander east of the Dead Sea, and Ein Ziq in the Negev. Two other sites in the Negev, Be’er Resisim, and Ha-Gamal, provide slightly earlier dates, although Resisim’s dates could be revised later based on the tendency for ostrich egg shell dates to run about 150 yr too early (Freundlich et al. Reference Freundlich, Kuper, Breunig and Bertram1989; Vogel et al. Reference Vogel, Visser and Fuls2001). Bab edh-Dhra‘, on the Dead Sea Plain, provides one 14C age (SI-2870) from a context reported originally as late Early Bronze III (Rast and Schaub Reference Rast and Schaub1980) then revised to Early Bronze IV (Rast and Schaub Reference Rast and Schaub2003). This date may be anomalously early or indicate a pre-Early Bronze IV context, as published originally. The balance of the southern Levantine Early Bronze IV 14C sequences (ranging between two and five dates each) include a determination from Khirbet Iskander ~2400 cal BC, followed by subsequent ages from Nahal Refaim, Ein Ziq, and Bab edh-Dhra‘, and end with a date just after 2000 cal BC from Bab edh-Dhra‘ (SI-2875).

Figure 7 Single-sample calibration distributions for 14C dates for seed and charcoal samples from Early Bronze IV sites in the southern Levant, Lebanon, and Tell el-Dab‘a, Egypt. Calibration based on OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013) using the IntCal13 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

Table 4 Radiocarbon results for seed and charcoal samples from Levantine Early Bronze IV contexts (ordered by site, lab, and sample number). Calibration based on OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013) using the IntCal13 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). *No Lab number indicated.

Beyond the southern Levant, the evidence for Early Bronze IV occupation of Tell Fadous-Kfarabida, Lebanon begins with two dates earlier than 2600 cal BC, and continues with a series of four more ages ending between 2300 and 2100 cal BC (Genz Reference Genz2014; Höflmayer et al. Reference Höflmayer, Dee, Genz and Riehl2014). The Early Bronze IV sequence at Tell Arqa, Lebanon, begins with a single charcoal age with a relatively large standard deviation (LY-2968) that may be anomalously early or offer isolated evidence of habitation in the early 3rd millennium BC (Thalmann Reference Thalmann2006, Reference Thalmann2008). The remaining five ages from Tell Arqa (two charcoal and three seed dates) stretch between the late 3rd and very early 2nd millennia BC. In tandem, these two Lebanese sites suggest Early Bronze IV occupations ~2600–2000 cal BC, based on 14C ages earlier in the period at Tell Fadous-Kfarabida and primarily later in the period at Tell Arqa. A set of six dates from Tell el-Dab‘a, Egypt, reflects Early Bronze IV habitation in the Nile Delta at the end of the 3rd millennium BC (Kutschera et al. Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetsky, Stadler, Seier, Thanheiser and Weninger2012). This comparative evidence hints at an early beginning of Early Bronze IV at Tell Fadous-Kfarabida and continues discontinuously at Tell Arqa and Tell el-Dab‘a through the balance of the period.

In the southern Levant, Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj provides the only detailed continuous 14C record of habitation through Early Bronze IV. Bayesian modeling estimates a beginning date before 2500 cal BC, which lies among a handful of the earliest Early Bronze IV dates anywhere in the Levant or Egypt. Unlike other southern Levantine records, the Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj sequence documents Early Bronze IV habitation over the ensuing 5 centuries, and ends concurrently with the latest comparative dates for the period ~2000 cal BC.

Comparative Evidence for the Beginning of the Middle Bronze Age

Tell el-Hayyat, Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1 and other key sites in the southern Levant, Egypt, and Lebanon provide 14C ages for the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age, thereby defining a terminus ante quem for the Early Bronze/Middle Bronze transition (Table 5; Figure 8). Unlike the array of previously published dates for Early Bronze IV, these results derive primarily from seed samples with smaller uncertainties than those produced by charcoal samples. Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1, where the earliest pottery conforms with Middle Bronze I vessel typology, reveals a 14C chronology starting slightly before 2000 cal BC and continuing to the mid-2nd millennium. Tell el-Hayyat Phase 5, featuring a ceramic assemblage ascribed typologically to early Middle Bronze I, contributes a series of 14C ages modeled ~1900–1850 cal BC. Phase 4 at Hayyat, with ceramics dated to Middle Bronze I, provides four tightly clustered dates modeled ~1830–1800 cal BC. Elsewhere in the northern Jordan Valley, Gesher contributes a single wood date around 2000 cal BC, while a seed-based sequence from Pella running between 2000 and 1700 cal BC accords well with the dating of Hayyat Phases 5 and 4. The Hayyat and Pella 14C sequences, as well as material culture and architectural forms, indicate the contemporaneity of the Phase 5 and 4 temples at Hayyat with the Phase 1 and 2 Early Mudbrick temples of Pella (Falconer and Fall Reference Falconer and Fall2006: 33–43; Bourke Reference Bourke2012).

Figure 8 Single-sample calibration distributions for 14C dates for seed and charcoal samples from Middle Bronze Age sites in the southern Levant, Tell Fadous-Kfarabida, Lebanon, and Tell el-Dab‘a, Egypt. Outlying dates OxA-25895 and VERA-5419 (Tell Fadous-Kfarabida) and AA-1239 (Tell el-Hayyat) omitted. Calibration based on OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013) using the IntCal13 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

Table 5 Radiocarbon results for seed samples from Middle Bronze Age contexts in the southern Levant and Tell el-Dab‘a, Egypt (ordered by site, lab, and sample number). Calibration based on OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013) using the IntCal13 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

14C ages from Tell el-Ifshar and Tell Nami on the Mediterranean Coastal Plain document settlement ~1900–1800 cal BC. Comparable Middle Bronze dates early in the 2nd millennium BC derive from Tell el-Dab‘a, Egypt and Tell el-Burak, Lebanon (Höflmayer et al. Reference Höflmayer, Kamlah, Sader, Dee, Kutschera, Wild and Riehl2016). Two of three 14C ages from Tell Fadous-Kfarabida, Lebanon (not included in Figure 8) lie very early in the 3rd millennium BC and probably indicate seeds mixed from earlier stratigraphic contexts (Höflmayer et al. Reference Höflmayer, Dee, Genz and Riehl2014: 534). A later sample from Tell Fadous-Kfarabida (VERA-5420) provides a more likely Middle Bronze Age date early in the 2nd millennium BC. The latter portions of the Middle Bronze Age in the Jordan Valley are reflected in several dates from Jericho ~1700–1500 cal BC, which follow those from Hayyat and Pella. When integrated with sequences from elsewhere in the Jordan Valley, the coastal southern Levant and the Nile Delta, 14C ages from Tell el-Hayyat and Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1 provide radiometric corroboration of a beginning date for the Levantine Middle Bronze Age about 2000 cal BC.

DISCUSSION

A variety of studies (e.g. Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht2001; Golani and Segal Reference Golani and Segal2002; Braun and Gophna Reference Braun and Gopha2004; Philip Reference Philip2008; Bourke et al. Reference Bourke, Zoppi, Hua, Meadows and Gibbins2009; Regev et al. Reference Regev, de Miroschedji, Greenberg, Braun, Greenhut and Boaretto2012a, Reference Regev, de Miroschedji and Boaretto2012b; Höflmayer et al. Reference Höflmayer, Dee, Genz and Riehl2014) now infer from radiometric data that the development of Levantine town life in Early Bronze II–III unfolded significantly earlier than suggested in previous literature. This growing revision features a radical repositioning of the end of Early Bronze III approximately 300 yr earlier than established in traditional chronologies. The date for this juncture has remained somewhat fluid, and a comparable revision of Early Bronze IV chronology has remained elusive, for several reasons. For example, predominance of charcoal dates and their relatively larger errors and, in the case of Be’er Resisim, shell dates with an added factor of uncertainty, have made greater resolution of Early Bronze IV chronology particularly challenging.

More fundamentally, however, the southern Levant includes only a limited number of excavated sites with radiometrically dated Early Bronze III/IV sequences and a near absence of stratified evidence spanning the Early Bronze IV/Middle Bronze transition. Both of these factors reflect the characteristic that most Early Bronze IV sites represent cemeteries, seasonal encampments, or discontinuous settlements that rarely persist through the period. Important village sites, such as Tell Iktanu (Prag Reference Prag1986, Reference Prag2001) and Tell Umm Hammad (Helms Reference Helms1986; Kennedy Reference Kennedy2015), as well as reduced Early Bronze IV habitation at a few major tells (e.g. Hazor, Megiddo; Bechar Reference Bechar2013), remain undated radiometrically. Bab edh-Dhra‘ and Khirbet Iskander provide unusual examples of sedentary communities occupied in both Early Bronze III and IV. However, each provides a limited number of ages, which date early in Early Bronze IV at Khirbet Iskander and late at Bab edh-Dhra‘ (if we exclude SI-2870 as an anomaly). In a similar fashion, the charcoal dates from Nahal Refaim and Ein Ziq estimate Early Bronze IV occupation primarily early at Ein-Ziq and later in the period at Nahal Refaim.

Farther afield, Tell Fadous-Kfarabida (Phase VI) provides 14C ages beginning early in Early Bronze IV based on seeds quite possibly mixed from earlier stratigraphic contexts (Höflmayer et al. Reference Höflmayer, Dee, Genz and Riehl2014:533–4). The evidence from Tell Arqa, Lebanon, includes three charcoal dates with particularly large uncertainties, one of which lies anomalously early in the 3rd millennium, and three seed dates that provide better resolution for the latter portion of Early Bronze IV. Thus, a revised date for the beginning of Early Bronze IV remains inferred largely from new dates for the end of Early Bronze III, rather than from Early Bronze IV sites with lengthy dated sequences stretching between the beginning and end of this period.

For the purpose of dating the close of Early Bronze IV, Tell el-Dab‘a, Egypt, provides 14C ages that bracket the Early Bronze IV/Middle Bronze Age transition (Kutschera et al. Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetsky, Stadler, Seier, Thanheiser and Weninger2012). In this case, seed dates from multiple excavation locales at the tell may be coordinated to chart Early Bronze IV occupation at the end of the 3rd millennium BC and Middle Bronze Age habitation beginning early in the 2nd millennium. When viewed jointly, these ages frame an Early Bronze IV/Middle Bronze Age transition around 2000 cal BC in the Nile Delta. Farther toward the interior of Syria, the excavated stratigraphy at Tell Mishrifeh spans the end of Early Bronze IV and the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age. Material culture and seven 14C ages from Phases 25–17 (including six charcoal dates) suggest a less distinctly defined transition again about 2000 cal BC (Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi2008). Strikingly, the southern Levant has provided no comparable example, thus far, of stratified Early Bronze IV ages that can be coupled with 14C evidence for the beginning of the subsequent Middle Bronze Age.

Unlike any other radiometrically dated site in the southern Levant, the 14C sequence from Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj, however, can be associated with stratified 14C evidence dating early in the Middle Bronze Age, in this case from the nearby village of Tell el-Hayyat. Early dates from Hayyat reveal Middle Bronze I occupation starting ~1900 cal BC, while those from Pella and Gesher to the north, as well as from ZAD 1 to the south provide earlier Middle Bronze dates around 2000 cal BC. The Middle Bronze 14C sequences at Tell el-Ifshar and Tell Nami on the Coastal Plain and Jericho in the Jordan Valley commence subsequently in the early 2nd millennium BC. This body of evidence, particularly the ages from Tell el-Hayyat, Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1, and Pella, provides a key link between the end of the Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj sequence and the immediately subsequent beginning of the Middle Bronze Age.

Most importantly, Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj provides the first example from the southern Levant of a deeply stratified, multiphase agrarian village that was occupied continuously through Early Bronze IV. The lengthy 14C sequence from Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj addresses both chronological ends of Early Bronze IV over the course of 22 AMS seed dates modeled through seven stratigraphic phases. Bayesian modeling calculates the beginning of this sequence ~2550 cal BC. A series of five phases (Ni‘aj Phases 7–3) ranging between ~35 and 55 yr each are modeled to ~2330 cal BC (as suggested by the modeled Phase 3/2 boundary), followed by two phases (Ni‘aj Phases 2–1) that continue to the apparent at the end of Early Bronze IV just before 2000 cal BC.

CONCLUSIONS

Bayesian modeling of a detailed stratified sequence of 14C ages from Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj, Jordan, indicates occupation over the course of the Early Bronze IV period beginning between 2600 and 2500 cal BC and continuing to just before 2000 cal BC. Thus, Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj provides the longest, most finely detailed 14C sequence of Early Bronze IV occupation in the southern Levant. The modeled dates for the beginning of this sequence align well with recent 14C-based revision of the end of Early Bronze III (e.g. Regev et al. Reference Regev, de Miroschedji, Greenberg, Braun, Greenhut and Boaretto2012a). When compared with Early Bronze Age sites across the southern Levant, Egypt, and Lebanon, the evidence from Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj pushes the beginning of Early Bronze IV 50–100 yr earlier than suggested by recent literature. In conjunction with early dates in the Middle Bronze Age from nearby Tell el-Hayyat and Pella in the Jordan Valley, and from Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1 by the Dead Sea, the Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj sequence continues through Early Bronze IV, ending ~2000 cal BC. This evidence from Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj augments the current trend of adjusting the constituent periods of the Levantine Early Bronze Age significantly earlier than suggested by traditional chronologies, while linking the end of Early Bronze IV with the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age ~2000 cal BC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Excavations at Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj, Tell el-Hayyat, and Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1 were conducted under permits from the Department of Antiquities, Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, and with the collaborative support of the American Center of Oriental Research, Amman. We offer our thanks to Department of Antiquities Directors-General Dr Adnan Hadidi, Dr Ghazi Bisheh, and Dr Fawwaz al-Khraysheh, and to ACOR Directors Dr David McCreery, Dr Pierre Bikai, and Dr Barbara Porter. An ACOR Publication Fellowship held by Falconer helped support analysis of Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj. The authors directed excavations at Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj with funding from the National Science Foundation (grants #SBR 96-00995 and #SBR 99-04536), the National Geographic Society (#5629-96), and the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research (#6006). Excavations at Tell el-Hayyat, directed by Falconer and Bonnie Magness-Gardiner, were funded by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities (#RO-21027 and #RO-22467-92), the National Geographic Society (#2598-83 and #2984-84), and the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research (#4382). Excavations at Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1 directed by the authors were funded by the National Geographic Society (#6655-99), the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research (#6608), and by a grant to P Edwards, Falconer, and Fall from the Australian Research Council. A grant from the Australian Institute for Nuclear Science and Engineering to Edwards, Falconer, and Fall funded the AMS 14C ages from Zahrat adh-Dhra‘ 1. Our work benefited from the cooperation provided by the NSF-University of Arizona AMS Laboratory and its director Greg Hodgins, as well as from a Bayesian analysis workshop provided by Project Mosaic at UNCC, and constructive comments provided by two anonymous reviewers. We thank Patrick Jones for drafting Figure 1, Barbara Trapido-Lurie for preparing Figure 2, and Wei Ming for drafting Figure 3.