INTRODUCTION

The collection of Osteology of the Musée des Confluences consists of 250 heads and skulls of Egyptian mummies. These human remains were collected during the late 19th and early 20th century in Upper Egypt by Charles-Louis Lortet (1836–1909) and by the anthropologist Ernest Chantre (1843–1924). Ch-L Lortet was the first dean of the Faculty of Medicine of Lyon and then director of the Natural History Museum of Lyon. Only the heads of the mummies were brought to France to enrich the anthropological collections of the museum (Chantre Reference Chantre1904). Therefore, much of the information related to the mummification of the bodies, their burial sites, and their possible identities has been lost forever. The origin and the dating of these mummies were given by their discoverers without reference to any excavation or a particular tomb.

Some of these heads have been subjected to several scientific studies like radiology, paleopathology, anthropology, etc. (Herzberg and Perrot Reference Herzberg and Perrot1983; Perraud Reference Perraud2012, Reference Perraud2013). More recently, an isotopic study was performed on a few of them in order to track the diet of ancient Egyptians (Touzeau et al. Reference Touzeau, Amiot, Blichert-Toft, Flandrois, Fourel, Gabolde, Grossi, Martineau, Richardin and Lécuyer2014) and to evaluate the increasing aridity in the Nile Valley in ancient Egypt (Touzeau et al. Reference Touzeau, Blichert-Toft, Amiot, Fourel, Martineau, Cockitt, Hall, Flandrois and Lécuyer2013).

The present research is part of a multidisciplinary project about the practices of mummification in ancient Egypt. The aim is to determine the evolution of mummification through the study of museum mummies. Furthermore, the geographical origins are unknown for most of them. One of the important aims of this project was to establish the chronology of the mummification process of the heads, including the brain extraction, the filling of the skull with balm, the use of linen textile for the wrappings, and the packing of the eye cavities and the nostrils with pads. However, the lack of archaeological data or excavation reports makes dating the specimens impossible, and we cannot provide objective conclusions concerning the chronology of mummification protocols.

The only data available were those attributed by the discoverers without any written proof: the heads were “dated” between the 11th Dynasty and the Ptolemaic period. Thus, they defined four periods within ancient Egyptian chronology (Hornung et al. Reference Hornung, Krauss and Warburton2006):

-

- a first phase extended from the 11th until the 20th Dynasty (~2025–1077 BC), forming a large range between the Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom;

-

- a second phase corresponding to the 18th Dynasty (~1540–1292 BC) of the New Kingdom;

-

- a third one to the 26th Dynasty (~664–525 BC) of the Late Period;

-

- and the last is the Ptolemaic period (~332–30 BC).

The series of heads have been 14C dated in order to put individuals in a reliable chronological and cultural framework. If possible, hair samples were taken, a powerful biological indicator, which can provide useful information about the lifestyle of the individual. We have applied a preparation protocol for hair, based on the selective extraction of keratin from cortex (Richardin et al. Reference Richardin, Gandolfo, Carminati and Walter2011). This method has been used successfully on a large number of mummies from museum collections (Richardin et al. Reference Richardin, Coudert, Gandolfo and Vincent2013; Diaz et al. 2015).

EXPERIMENTAL

Sampling

The studied mummy heads are in a variable state of conservation (Figure 1). Some heads have not been unwrapped and are completely covered with linen textile (Figure 1a). Others have conserved all their biological tissues and also their hair (Figure 1b,c), while some have been damaged by keratinophage insects and are in a poor state of conservation (Figure 1d). Finally, skin, teeth, and also some hair were removed from heads (Figure 1e, f) where only a few organic tissues or linen textiles remain.

Figure 1 Photographs of six heads of mummies of the Confluences Museum, showing the diversity of mummification techniques and states of conservation: (a) Inv 30000141_B38; (b) Inv 30000121; (c) Inv 30000113_B10; (d) Inv 30000106_B8; (e) Inv 3000102_B3; and (f) Inv 30000151_B48.

For this reason, hair samples were collected and sometimes when hair was not accessible (totally wrapped mummies), linen textile samples were taken. In total, 20 samples of hair and 13 samples of linen textiles were taken for 14C dating.

Sample Preparation

The main difficulty for 14C dating of samples taken from Egyptian mummies is, of course, the contamination during the mummification process (due to the use of mineral salts, balms, resins, oils, etc.). Moreover, the fluids produced by the decomposition of the body complicate the dating. Therefore, the extraction of these exogenous organic compounds must be properly controlled to avoid perturbations during the 14C dating of samples (Quiles et al. Reference Quiles, Delqué-Količ, Bellot-Gurlet, Comby-Zerbino, Ménager, Paris, Souprayen, Vieillescazes, Andreu-Lanoë and Madrigal2014).

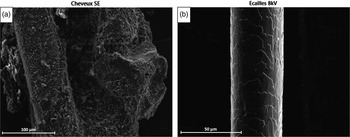

The efficiency of protocols used for the extraction of amorphous organic compounds from archaeological artifacts is well established. These methods, based on solvent extractions, were set up in 1959 (Bligh and Dyer Reference Bligh and Dyer1959) and slightly modified to be applied for chromatographic analyses in archaeology (Regert Reference Regert2011; Garnier Reference Garnier2014). In a recent paper (Richardin and Coudert Reference Richardin and Coudert2016), we have taken several samples from an Egyptian mummy and its associated burial material. Extraction with solvents, if the latter are correctly eliminated with pure water, does not affect the results of 14C dating, as it has been shown on keratin extracted from hair, linen textiles, and vegetal samples (leaves). Indeed, all the 14C dates obtained are similar. All samples were thus subjected to the same protocol (Richardin and Gandolfo Reference Richardin and Gandolfo2013a, Reference Richardin and Gandolfo2013b): a successive washing with ultrapure water (Direct-Q system from Millipore), then a mixture of methanol/dichloromethane (v/v 1/1) (for analysis, VWR International), and finally with acetone (AnalaR Normapur, VWR International) in an ultrasonic bath for 10 min. After the last treatment, samples were thoroughly rinsed three times with ultrapure water. This protocol was applied with success on very impregnated hair. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images (recorded on a Phillips XP CL 30 series) on a hair sample (Figure 2) show the efficiency of the cleaning procedure.

Figure 2 SEM-SE image of hair taken on the mummy head (Inv. 30000111) before (a) and after (b) the cleaning procedure.

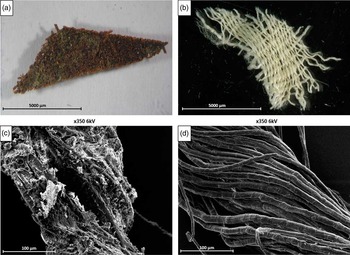

Keratin from hair samples was extracted (Richardin et al. Reference Richardin, Gandolfo, Carminati and Walter2011) according to a routine procedure we use in the laboratory and applied to various samples (Richardin et al. Reference Richardin, Coudert, Gandolfo and Vincent2013; Díaz-Zorita Bonilla et al. Reference Díaz-Zorita Bonilla, Drucker, Richardin, Silva-Pinto, Sepúlveda and Bocherens2016). Linen textiles were subjected to an acid-alkali-acid treatment followed by an oxidative bleaching with NaClO2. Figure 3 shows the binocular photographs and the SEM images of an impregnated linen textile sample before and after these pretreatments, showing their efficiency.

Figure 3 Photographs of a textile sample (taken on head Inv. 30000103) before (a) and after pretreatments (b). SEM-SE image of a few fibers before (c) and after (d) the cleaning procedure.

Some 2–2.5 mg of the dried samples were combusted for 5 hr at 850°C under vacuum in a quartz tube with CuO and a piece of silver wire. The CO2 was collected in a sealed tube. Graphitization of the CO2 gas was performed at the LMC14 laboratory of Saclay (France) with a routine protocol (Moreau et al. Reference Moreau, Caffy, Comby, Delqué-Količ, Dumoulin, Hain, Quiles, Setti, Souprayen, Thellier and Vincent2013).

Radiocarbon Measurements and Calibration

All measurements were performed with the Artemis AMS facility at Saclay (France) (Moreau et al. Reference Moreau, Caffy, Comby, Delqué-Količ, Dumoulin, Hain, Quiles, Setti, Souprayen, Thellier and Vincent2013). Calendar ages are determined using the OxCal v 4.2 procedure (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) and the most recent calibration curve data for the Northern Hemisphere, IntCal13 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

RESULTS

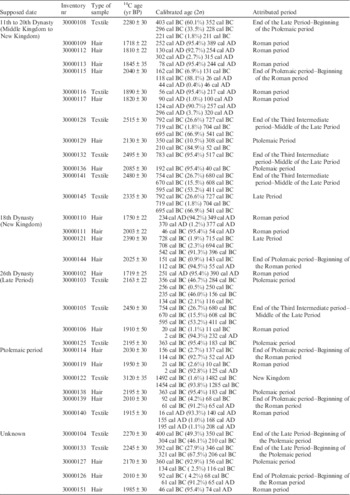

All the 14C ages and calibrated dates of hair and linen textile samples are given in Table 1. Among all the studied human remains, only one sample seems to stand out. Indeed, the date obtained for this linen textile sample taken on the mummy head Inv. 30000122 is 3120±35 yr BP (1492–1285 cal BC, 95.4%). It thus seems that the mummy is from the New Kingdom in ancient Egyptian history, a period between 1550 and 1070 BC, which corresponds to the 18th until the 20th Dynasty. The brain has been removed from the skull, and a little quantity of balm (a mixture of colophony and beeswax) has been poured into the cranium, which is filled with a linen textile. These mummification practices are more ancient than those used during the Ptolemaic period (Dunand and Lichtenberg Reference Dunand and Lichtenberg2001), the period attributed to the mummy by the archaeologists.

Table 1 14C age and calibrated age of all samples.

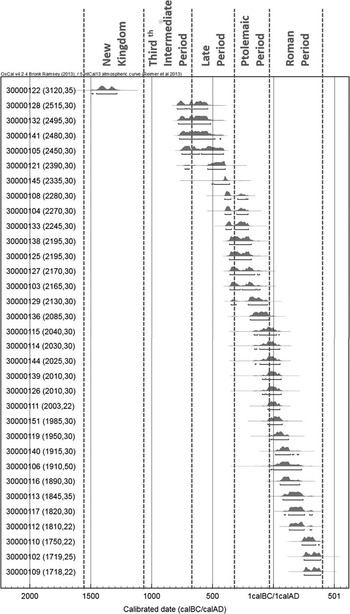

Therefore, except for this last sample, the range of dates obtained for all the mummies is between 2515±30 yr BP (for mummy Inv. 30000128) and 1718±22 yr BP (for mummy Inv. 30000109), a range spanning close to a millennium (Figure 4). These data correspond to a period from the Third Intermediate period (~1077–655 BC) until the Roman period (~30 BC until AD 395). We quickly concluded that the dates assigned to the majority of the mummies were wrong.

Figure 4 Calibrated dated obtained for the mummies, according the Pharaonic Dynasties in Egypt

The first series of 13 mummies were supposed to be dated between the 11th and 20th Dynasty (~1980–1077 BC, so from Middle Kingdom until New Kingdom). However, none appears from this period. Three of them (Inv. 30000128, 30000132, and 30000141) are from the end of the Third Intermediate period to the middle of the Late Period (~664–332 BC). Two mummies (Inv. 30000145 and Inv. 30000108) belong to the Late Period, and three of them (Inv. 30000129, 30000136, and 30000115) to the Ptolemaic period, whereas the five others date from the Roman period (Inv. 30000116, 30000113, 30000117, 30000112, and 30000109).

A group of four mummies supposed to date from the 18th Dynasty are indeed more recent: Inv. 30000121 (728–396 cal BC) is dated from the Late Period, Inv. 30000144 (112–55 cal BC) from the end of the Ptolemaic period to the beginning of the Roman period, and the last two mummies (Inv. 30000111, 30000110) are Roman.

All four mummies originally supposed to date from the 26th Dynasty are more recent: Inv. 30000105 (2450±30 BP, 754–411 cal BC) is dated from the end of the Third Intermediate period to the middle of the Late Period, Inv. 30000125 (2195±30 BP, 363–183 cal BC) from the Ptolemaic period, and Inv. 30000106 and 30000102 are Roman (1910±30 BP, 20 cal BC–cal AD 232 and 1719±30 BP, cal AD 251–390, respectively).

Among the six mummies originally dated from the Ptolemaic period, only one (Inv. 30000138) belongs to this period. Four others are Roman (Inv. 30000114, 30000144, 30000119, and 30000140), but the other one (Inv. 30000122), cited above, is the oldest of the series studied, belonging to the New Kingdom. However, Inv. 30000104 and 30000133, which are from the end of the Late Period to the beginning of the Ptolemaic period, the last three undated mummies are all from the Ptolemaic period or the Roman period (Inv. 30000127, 30000126, and 30000151).

The late Roman period was not considered by the discoverers, even though mummies from this historic period are the most frequently excavated. Indeed, in this period, mummification was practiced in all the social classes, and burials were less rich. Thus, grave robbers were less interested in them. It is also possible that these mummies were deposited in ancient tombs, which were thus reoccupied, giving incorrect information about their age.

CONCLUSION

This work is the first large 14C dating project on the heads of mummies from the Confluences Museum. Except for one mummy from the New Kingdom (~1540–1077 BC), the range of dates obtained is between approximately 800 BC and AD 400, a range of close to a millennium. These data correspond to a time from the end of the Third Intermediate period (~1069--655 BC) until the Roman period (~AD 30–395). Hence, the majority of the mummies are from more recent times.

The results allowed us to make conclusions about the chronology of this series and, in particular, revealed a lot of errors in attribution. Overall, we have shown that the attributed dates have often overestimated the age of the mummies. Indeed, for example, among the 13 mummies supposed to be dated between the 11th and the 20th dynasty, none corresponds to this period. The four mummies, dated as from the 26th Dynasty, also called the Saite period, are also more recent, i.e. from the end of the Third Intermediate period until the Ptolemaic period. The discoverers were probably motivated by an anthropological interest since they only took the mummies’ heads without studying the archaeological context and the funerary practices of ancient Egypt. They did not make excavation reports and consequently a large quantity of information about the deceased was lost.

At the end of this study, the dates of a series of mummies, previously undated, were correctly attributed. They are almost all from recent periods (Ptolemaic and Roman). For this reason, this project will be continued with the 14C dating of other mummies, in order to obtain data on earlier periods, which could reveal other funerary practices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors want to thank the staff of the LMC14 (Laboratory of Radiocarbon Measurement) of Saclay (France) for their contribution to the analytical work in graphitization and 14C measurement. We are also very grateful to Margaret Méjean for her English language corrections.