INTRODUCTION

The Minoan Santorini eruption, classified as “super-colossal” with a volcanic explosivity index (VEI) of 7, may have been the largest known volcanic eruption in the world during the Holocene (Johnston et al. Reference Johnston, Sparks, Phillips and Carey2014). It certainly was the largest eruption in the eastern Mediterranean region during this time period. The date for the latter eruption is controversial. Studies about cultural archaeological associations with Egypt are usually understood to suggest a link between the Minoan Eruption and the 18th Dynasty around 1500 BCE (Doumas 1983; Bietak Reference Bietak2003, Reference Bietak2013, Reference Bietak2015, Reference Bietak2016; MacGillivray Reference MacGillivray2009; Warren Reference Warren2009; Wiener Reference Wiener2009). However, radiocarbon dates of organic materials related stratigraphically to the time of the eruption favor a calibrated age range in the second half of the 17th century BCE (Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Manning and Galimberti2004; Friedrich et al. Reference Friedrich, Kromer, Friedrich, Heinemeier, Pfeiffer and Talamo2006; Friedrich and Heinemeier 2009; Manning Reference Manning2014; Manning et al. Reference Manning, Bronk Ramsay, Kutschera, Higham, Kromer, Steier and Wild2006, Reference Manning, Höflmayer, Moeller, Dee, Bronk Ramsey, Fleitmann, Higham, Kutschera and Wild2014; Bruins et al. Reference Bruins, MacGillivray, Synolakis, Benjamini, Keller, Kisch, Klügel and van der Plicht2008, Reference Bruins, van der Plicht and MacGillivray2009; Bruins Reference Bruins2010; Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht2014).

The significance of the controversy is well expressed by Warren (Reference Warren2009:181): “Why is it important to fix the date of the Minoan eruption of Santorini? Essentially the answer is that in order to write the history of international relations of the later Middle and the Late Bronze Age in the eastern Mediterranean we need to establish whether, at the time of the Minoan eruption of Santorini, the Egypt which was linked to the Aegean, Cyprus and the Levantine region was that of late Dyn. XIII or earlier Second Intermediate Period on the one hand or that of the early New Kingdom (early Dyn. XVIII) on the other.”

One of the most important sites in Egypt in relation to the above controversy is Tell el-Dabca, (Figure 1) excavated during many years by Bietak (Reference Bietak1975, Reference Bietak2003, Reference Bietak2013, Reference Bietak2015, Reference Bietak2016). Seaborne pumice of the Minoan Santorini eruption has been found in phase C/2 in the Palace District ‘Ezbet Helmi (Bietak Reference Bietak2003; Bichler et al. Reference Bichler, Exler, Peltz and Saminger2003; Bietak and Höflmayer Reference Bietak and Höflmayer2007). Radiocarbon dates on charcoal were not useful (Bruins Reference Bruins2007), but short-lived material (seeds) from Tell el-Dabca gave important results, showing an offset of about 120 years between archaeo-historical ages and 14C dating (Kutschera et al. Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012). Concerning this enigma, Bruins (Reference Bruins2010:1490) expressed a key question: “What is erroneous here—the 14C dates … or the associations between the Tell el-Dabca archaeological phases and dynastic history?” The rather comprehensive 14C dating investigations of Egyptian dynasties by Bronk Ramsey et al. (Reference Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Rowland, Higham, Harris, Brock, Quiles, Wild, Marcus and Shortland2010) and Dee (Reference Dee2013a, Reference Dee2013b) do not show a systematic offset of 120 years between dynastic history and 14C dating. In fact, the 14C results grosso modo corroborate historical chronological compilations of ancient Egypt. Therefore, the problem seems to be the association between archaeological phases and political history. Indeed, alternative historical-archaeological associations or interpretations concerning Tell el-Dabca have recently been developed by Höflmayer (Reference Höflmayer2017, Reference Höflmayerforthcoming), also in relation to new radiocarbon dates of other Middle Bronze Age sites in the Levant (Höflmayer et al. Reference Höflmayer, Kamlah, Sader, Dee, Kutschera, Wild and Riehl2016a, Reference Höflmayer, Yasur-Landau, Cline, Dee, Lorentzen and Riehl2016b).

A key archaeological site in southern Israel is Tel Ashkelon (Figure 1), where important excavations were conducted by Stager and his team since 1985 in the framework of the Leon Levy expedition (Stager et al. Reference Stager, Schloen and Master2008). The Middle Bronze Age stratigraphic phases of Tell el-Dabca and Ashkelon have been related to each other (Table 1) on the basis of ceramic studies (Bietak et al. Reference Bietak, Kopetzky, Stager and Voss2008). This stratigraphic linkage between the two sites enables evaluation whether the radiocarbon dating offset found for Tell el-Dabca (Bietak and Höflmayer Reference Bietak and Höflmayer2007; Kutschera et al. Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012) is also present at Tel Ashkelon?

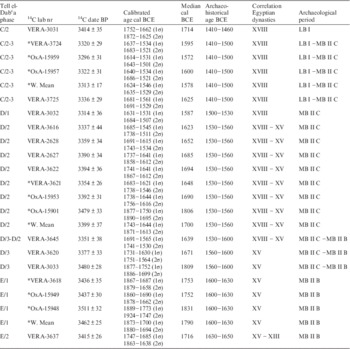

Table 1 Stratigraphic relationship between archaeological phases of Tell el-Dabca and Ashkelon, based on ceramics (Bietak et al. Reference Bietak, Kopetzky, Stager and Voss2008). Also added are correlations with archaeological periods, Egyptian dynasties and archaeo-historical age assessments, partly based on Bietak, as published in Kutschera et al. (Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012:Table 3).

Entailed in the above question is the chrono-stratigraphic position at both sites of the Minoan Santorini eruption, according to 14C dating only (Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht2003), which is the main focus in this preliminary study. The 14C dates presented and evaluated in this article include Ashkelon Phases 10 and 11, as well as the related Phases D/1 to E/2 of Tell el-Dabca (Table 1). In addition, Phases C/2 and C/3 of Tell el-Dabca are also considered in this study, because these immediately predate Phase D/1 in the stratigraphic archaeological sequence, while pumice from the Minoan Santorini eruption was found in Phase C/2 (Bietak Reference Bietak2003; Bichler et al. Reference Bichler, Exler, Peltz and Saminger2003). Using radiocarbon dating as the principal chronological tool is a legitimate methodological approach, carried out in countless archaeological and geological studies all over the world.

14C DATES OF TELL EL-DABcA AND THE MINOAN SANTORINI ERUPTION

An important set of 14C dates of Tell el-Dabca, based on seeds, was published by Kutschera et al. (Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012). We used their data to calculate the 1σ and 2σ calibrated age ranges with the newer IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013), using OxCal 4.2. (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2016), for the series of Phases from E/2 to C/2 (Table 2). We also added the calibrated median values, available in the OxCal program (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2001, Reference Bronk Ramsey2009, Reference Bronk Ramsey2016) as a concise figure to represent the middle value of the calibrated age range (Table 2).

Table 2 Radiocarbon dates of Tell el-Dabca, based on Kutschera et al. (Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012: Table 1a). Calibrated ages were calculated with OxCal 4.2 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2001, Reference Bronk Ramsey2009, Reference Bronk Ramsey2016), using the IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). The stratigraphic phases C/2 to E/2 are included and presented in relation to archaeo-historical age assessments, correlations with Egyptian Dynasties and archaeological periods, according to Bietak, as published in Kutschera et al. (Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012: Table 3).

Based on short-lived organic material from the archaeological excavations at Akrotiri on Thera, the average uncalibrated 14C age for the Minoan Santorini eruption is 3350±10 BP (Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Manning and Galimberti2004). Our investigations of tsunami layers at Palaikastro (Crete), caused by the Minoan Santorini eruption, yielded similar results on short-lived animal bones. Two 14C dates from a building destroyed by the tsunami gave a weighted average of 3350±25 BP (Bruins et al. Reference Bruins, MacGillivray, Synolakis, Benjamini, Keller, Kisch, Klügel and van der Plicht2008). Three other 14C dates near Building 6, yielded a weighted average of 3352±23 BP (Bruins et al. Reference Bruins, van der Plicht and MacGillivray2009). These average uncalibrated ages for the Minoan Santorini eruption from Thera and Crete are remarkably similar. Hence there is no volcanic reservoir effect on Thera, as explicated in more detail by Bruins and van der Plicht (Reference Bruins and van der Plicht2014). This conclusion has recently been confirmed by an independent investigation of modern vegetation on Thera by Fernandes et al. (Reference Fernandes, Dreves, Klontza-Jaklova and Cook2016).

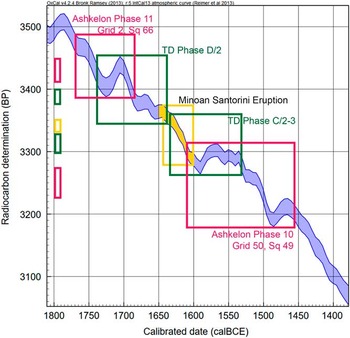

Bayesian modeling by Manning et al. (Reference Manning, Höflmayer, Moeller, Dee, Bronk Ramsey, Fleitmann, Higham, Kutschera and Wild2014) based on 25 radiocarbon measurements of short-lived samples from Akrotiri (Thera) resulted in a 2σ calibrated date of 1646–1603 BCE (95.4%) for the Minoan Santorini eruption. Concerning the famous olive tree branch from Thera, which has given a precise wiggle-matched calibrated date for the Santorini eruption (1627–1600 cal BCE), the uncalibrated 14C date for the outer rings 60–72 is 3331 ± 10 BP (Friedrich et al. Reference Friedrich, Kromer, Friedrich, Heinemeier, Pfeiffer and Talamo2006). Moreover, recalculation by Manning et al. (Reference Manning, Höflmayer, Moeller, Dee, Bronk Ramsey, Fleitmann, Higham, Kutschera and Wild2014) with the more recent IntCal 13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013) of the four dated olive branch segments from Thera (Friedrich et al. Reference Friedrich, Kromer, Friedrich, Heinemeier, Pfeiffer and Talamo2006), using sequence analysis without tree ring input yielded a very similar calibrated date of 1646–1609 BCE (93.5%), as compared to the above date of the 25 samples of Akrotiri (Manning et al. Reference Manning, Höflmayer, Moeller, Dee, Bronk Ramsey, Fleitmann, Higham, Kutschera and Wild2014). This time range for the Minoan Santorini eruption, based on the above two data sets from Thera (Manning et al. Reference Manning, Höflmayer, Moeller, Dee, Bronk Ramsey, Fleitmann, Higham, Kutschera and Wild2014) is indicated on the calibration curve (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Location of the Santorini Volcano (Aegean Sea, Greece) and the archaeological sites of Tell el-Dabca (Egypt) and Ashkelon (Israel), generated with Google Earth Pro ©.

Figure 2 The IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013) in OxCal (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2016). Upon this time framework we show the graphic location of the 2σ calibrated ages of the Minoan Santorini eruption (Manning et al. Reference Manning, Höflmayer, Moeller, Dee, Bronk Ramsey, Fleitmann, Higham, Kutschera and Wild2014), of Tell el-Dabca (TD) Phase D/2 and Phase C/2-3, based on dates by Kutschera et al. (Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012), and of Ashkelon Phase 11 (Grid 2, Square 66) and Ashkelon Phase 10 (Grid 50, Square 49). The related uncalibrated radiocarbon dates BP are indicated along the Y-axis.

The 14C results from Thera and Crete give an idea of the age of the Santorini eruption in both uncalibrated radiocarbon years BP and calibrated ages cal BCE. Concerning the chronostratigraphic position of the Minoan eruption at Tell el-Dabca, we follow two lines of reasoning. First we compare apples (archaeological dates) with oranges (14C dates). Archaeological age assessments by Bietak (Reference Bietak2003, Reference Bietak2013, Reference Bietak2015) give an age of about 1590–1620 BCE for Tell el-Dabca Phase E/1 and 1620–1650 for Phase E/2. Therefore, these two strata appear to have a rather similar time dimension as the calibrated sequenced 14C ages for the Minoan Santorini eruption (Friedrich et al. Reference Friedrich, Kromer, Friedrich, Heinemeier, Pfeiffer and Talamo2006; Manning et al. Reference Manning, Höflmayer, Moeller, Dee, Bronk Ramsey, Fleitmann, Higham, Kutschera and Wild2014).

However, comparing oranges with oranges, the weighted mean 14C age for Phase E/1 (3462±25 BP) has a calibrated 1σ range of 1873–1700 cal BCE (Table 2), which is about 250 to 80 years older than the 14C age for the Minoan eruption. Phase E/2 has only one 14C date (3415±26 BP), being somewhat younger, with a calibrated 1σ range of 1747–1685 (Table 2), about 120 to 60 years older than the eruption. Evidently, Phases E/2 and E/1 are significantly older than the Minoan eruption, according to 14C dating.

Examining 14C results of Tell el-Dabca in Table 2, it is clear that Phases C/2-3 and D/1 have rather comparable or slightly younger 14C dates as the Minoan Santorini eruption. It is, therefore, striking that pumice from this eruption has been found in Phase C/2 (Bietak Reference Bietak2003), as highlighted also in other studies (Bruins Reference Bruins2010; Höflmayer Reference Höflmayer2017). The weighted mean of a number of samples from Phase C/2-3, 3313 ± 17 BP (Table 2, Kutschera et al. Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012), and the related calibrated 2σ age range, 1635–1529 cal BCE, have been placed on the IntCal13 calibration curve (Figure 2) for comparison with the 14C age of the Minoan Santorini eruption. There is indeed considerable overlap with the calibrated age range of the eruption, though part of the Phase C/2-3 age range is somewhat younger than the eruption.

Concerning Phase D/2, we have calculated the weighted average of all seven 14C dates (Table 2), resulting in a date of 3387±12 BP. The calibrated 2σ age range is 1740–1637 cal BCE. These results are graphically placed in Figure 2, showing that Phase D/2 is somewhat older than the eruption, though the youngest part of its 2σ age range slightly overlaps with the age range for the eruption. Therefore, in chronostratigraphic terms, based on 14C dating, the Minoan Santorini eruption appears to have occurred, within the field stratigraphic sequence of Tell el-Dabca, after Phase D/2 or in its youngest part, or in Phase D/1, or in the older part of Phase C/2-3 (Figure 2).

14C DATES OF ASHKELON IN RELATION TO TELL EL-DABcA AND THE MINOAN SANTORINI ERUPTION

In this article we present a number of radiocarbon dates of Tel Ashkelon from Phases 10 and 11 (Table 3), in relation to the 14C date of the Minoan Santorini eruption. Since only two phases of Ashkelon are included in this study, we consider it premature to present here a sequence model. However, this will be done in another investigation, after additional 14C dates have been measured of Ashkelon. Then the Middle Bronze Age Phases 14, 13, 12, 11 and 10 (Table 1) will all be incorporated in a Bayesian sequence model.

Table 3 Radiocarbon dates of Tel Ashkelon for stratigraphic phases 10, 11 and 12. Calibrated ages were calculated with OxCal 4.2 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2001, Reference Bronk Ramsey2009, Reference Bronk Ramsey2016), using the IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). Archaeo-historical age assessments are based on Bietak et al. (Reference Bietak, Kopetzky, Stager and Voss2008: Figure 9). Correlations with archaeological periods and Egyptian Dynasties are based on comments by Daniel Master (personal communication) and Ross Voss (personal communication), and partly on Bietak et al. (Reference Bietak, Kopetzky, Stager and Voss2008: Figure 9) and Bietak, as published in Kutschera et al. (Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012: Table 3).

Ashkelon Phase 10

The duration of Ashkelon Phase 10 is not clear. This phase is mainly associated with the last period of the Middle Bronze Age (MB II C or MB III in other classification systems). The matter is well expressed by the excavators, Voss and Stager (Reference Voss and Stagerforthcoming), concerning the northern part of Tel Ashkelon: “The Phase 10 construction belongs to the last part of the Middle Bronze Age but its exact date and duration are difficult to determine on the basis of the material that is preserved. The centuries of erosion that followed, when the city’s fortifications were neglected during the Late Bronze Age and the first part of the Iron Age I, resulted in the loss of the hypothesized Phase 10 glacis, which we were not able to detect. The erosion of the rampart came to an end in the later part of the Iron Age I, after the arrival of the Philistines, when a new rampart was built on the North Slope of Ashkelon in Phase 9” (Voss and Stager, Reference Voss and Stagerforthcoming). The above quotation makes it clear that a long time period exists between Phase 10 and Phase 9, as the former is considered primarily Middle Bronze Age IIC and the latter primarily Iron Age.

Concerning Tell el-Dabca, Bietak (Reference Bietak2003, Reference Bietak2015) places the transition between the Middle Bronze Age (MB) and the Late Bronze Age (LB) in the time range of about 1530 to 1480 BCE. A treatment of this issue is beyond the scope of the present article, but the above time boundary will be used in the evaluation of the 14C dates presented here from Ashkelon. Indeed the Ashkelon excavators place Phase 10, according to archaeological considerations, in the time period 1580–1480 BCE.

Olive pits were found in a stone-lined installation (Table 3) in Grid 50, Square 49 (Feature 521, Basket 40), which was assigned by the excavators to Ashkelon Phase 10. This excavation area is situated in the southwestern part of Tel Ashkelon. The associated pottery has been related by the excavators to the Late Bronze Age. The three 14C dates from the olive pits (Table 3) show two results that are quite similar (GrA-40885, 3275±35 BP and GrA-40886, 3225 ± 35 BP), well within 2σ standard deviations from each other. However, a third date (GrA-40889, 3355±35 BP) is significantly older. Indeed, the weighted average of the three dates (3285±20 BP) is not quite acceptable by the chi-square test (T=7.0, 5%=6.0). Removing the latter outlier, the weighted average of the two remaining dates is 3250±25 BP, which is accepted by the chi-square test (T=1.0, 5%=3.8). The calibrated 2σ age range, using OxCal (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2001) and the IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013) is 1611–1453 cal BCE, while the median value is 1522 cal BCE (Table 3).

Comparing this result with the archaeological time period given to Ashkelon Phase 10 by the excavators, 1580–1480 BCE, it is clear that the calibrated 14C age range covers the former completely. Therefore, archaeological dating and radiocarbon dating appear to be quite similar for the Phase 10 stone-lined installation in Grid 50. Comparing the olive pit calibrated date with the Minoan Santorini eruption, it can be concluded that this part of Ashkelon Phase 10 is younger than the eruption (Figure 2), though there is very slight overlap in the 1611–1600 time range.

Regarding archaeological periodization, the related pottery of the stone-lined installation was classified as LB. Taking the MB-LB boundary time interval 1530 to 1480 BCE suggested by Bietak (Reference Bietak2003, Reference Bietak2015), the above calibrated 14C date of Ashkelon Phase 10 can indeed be either MB or LB. Yet the relative MB time coverage of the 14C date (1611–1453 cal BCE) is larger than the respective LB coverage. Ashkelon Phase 10 has been stratigraphically related (Table 1) to Tell el-Dabca Phases D/1, D/2 and partly D/3 on the basis of ceramic comparison (Bietak et al. (Reference Bietak, Kopetzky, Stager and Voss2008). The above 14C results of Ashkelon Phase 10 from Grid 50 show similarity with 14C dates of Tell el-Dabca Phase D/1 (Table 2). The 14C dates for D/2 and D/3 tend to be older (Table 2). Phases D/1, D/2 and D/3 are all considered to belong to MB IIC (Bietak Reference Bietak2003, Reference Bietak2015), i.e. the youngest part of the Middle Bronze Age.

Another sample of Ashkelon Phase 10 is derived from the northern part of the tell (Grid 2, Square 101). It is a bone (vertebra) of a mature sheep or goat found in a bin fill (Layer 139, Basket 175). The related pottery of this bin fill is classified by the excavators as a mixture of Middle Bronze Age and Iron I ceramics. Such a classification fits with the above quotation from Voss and Stager (Reference Voss and Stagerforthcoming) that after Phase 10, attributed largely to MB IIC, the next Phase 9 is Iron Age. Though the archaeological context of the bone sample is not ideal, the 14C dating result (GrA-34459, 3310±60 BP) is definitely not Iron Age, having a 2σ calibrated age range of 1741–1451 cal BCE, with a median value of 1593 cal BCE. The amount of collagen in the bone was not sufficient for a more precise date, as the standard deviation is 60 radiocarbon years. The calibrated age range is, as a result, very wide covering about 300 years, including mainly MB, a bit of LB, and also the 14C time range of the Minoan Santorini eruption.

Ashkelon Phase 11

The excavators have related Phase 11 to the MB II B archaeological period, associated in political-historical terms with the Early Fifteenth Dynasty (Early Hyksos Dynasty), dated to 1660–1580 BCE. The four 14C dates of Ashkelon Phase 11 are all very coherent. A calcaneus bone of a sheep from destruction debris in Grid 2 (Square 101, Layer 146, Basket 228) yielded a rather precise date (Table 3) of 3390±35 BP (GrA-34267). The 1σ calibrated age range is 1737–1641 cal BCE and the 2σ age range is 1862–1612 cal BCE, while the median calibrated value is 1688 cal BCE. Also from Phase 11 in Grid 2 (Square 66, Layer 178, Basket 8) is a burial with charred grape pips. These seeds were measured by three separate AMS determinations, which gave very similar results (GrA-40728, 3400±30 BP; GrA-40730, 3440±30 BP; GrA-40731, 3430±30 BP). Hence the weighted average of the three dates, 3425±15 BP, can be regarded as an accurate and precise time measurement. The 2σ calibrated age range is 1770–1683 cal BCE, while the median value is 1722 cal BCE (Table 3).

Although the calcaneous bone date (GrA-34267) has minor overlap in its youngest part of the calibrated time range with the 14C age of the Minoan Santorini eruption, the date of the grape pips is significantly older than the eruption. Therefore, it seems on the basis of these 14C dates that Ashkelon Phase 11 predates the Minoan eruption (Figure 2). Concerning comparison with Tell el-Dabca, Phases D/3 (partly), E/1 and E/2 are related to Ashkelon Phase 11 on the basis of ceramics (Bietak et al. Reference Bietak, Kopetzky, Stager and Voss2008). How do the 14C dates of these interrelated phases of both archaeological sites correlate with each other? It is clear that the radiocarbon dates are indeed very similar (Tables 2 and 3)! Hence the ceramic association between these phases of Tell el-Dabca and Ashkelon is fully supported by their 14C dates. It also proves that the time difference between archaeological dating and 14C dating, established previously for Tell el-Dabca (Bietak and Höflmayer Reference Bietak and Höflmayer2007; Kutschera et al. Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012), has now also been confirmed for Tel Ashkelon regarding Phase 11. The 14C dates of both sites are about 100 years older than the archaeological age assessments for these phases.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The principal results of our investigation are displayed graphically in Figure 2. We used 14C dating as the basic methodology to assess the time position of the Minoan Santorini eruption within the archaeological stratigraphy of Tell el-Dabca and Tel Ashkelon. The 14C dates of various phases at Tell el-Dabca show that Phase D/2 is for most of its 2σ calibrated age range (weighted average 1740–1637 cal BCE, based on Kutschera et al. Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012) older than the volcanic eruption. Only the youngest edge of the age range of Phase D/2 just touches the eruption date, 1646–1603 cal BCE. The latter 2σ calibrated date for the Minoan eruption (Manning et al. Reference Manning, Höflmayer, Moeller, Dee, Bronk Ramsey, Fleitmann, Higham, Kutschera and Wild2014) is based on multiple short-lived samples from the archaeological excavations at Akrotiri.

Tell el-Dabca Phase D/1 is stratigraphically younger than Phase D/2 (Bietak, Reference Bietak2003, Reference Bietak2015). There is only one 14C date available for Phase D/1 (Kutschera et al. Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012), which has a wide 2σ calibrated age range of 1684–1507 (Table 2) that also overlaps fully with the above 2σ calibrated date for the Minoan eruption.

The subsequent Phase C/2-3, stratigraphically younger than Phase D/1 (Bietak, Reference Bietak2003, Reference Bietak2015), has a number of 14C dates (Kutschera et al. Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012). The weighted average of three dates (Table 2) gives a 2σ calibrated age of 1635–1529 cal BCE. This result overlaps in its older part with the volcanic eruption (Figure 2), although the central and younger part of the range is somewhat younger, as indicated also by the median calibrated value, 1578 cal BCE (Table 2).

Concerning Ashkelon, Phase 11 (Grid 2, Square 66), having a 2σ calibrated age of 1770–1683 cal BCE, is clearly older than the Minoan Santorini eruption. This Ashkelon phase has been associated by Bietak et al. (Reference Bietak, Kopetzky, Stager and Voss2008) on the basis of ceramics with Tell el-Dabca Phases D/3, E/1 and E/2. The latter phases have similar 14C dates as Ashkelon Phase 11, which independently confirm the validity of the above ceramic correlation. However, the 14C dates of these phases are about 100 years older than their archaeological age assessment. Ashkelon Phase 11, therefore, shows the same age offset as previously found for Tell el-Dabca (Bietak and Höflmayer Reference Bietak and Höflmayer2007; Kutschera et al. Reference Kutschera, Bietak, Wild, Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Golser, Kopetzky, Stadler, Steirer, Thanheiser and Weninger2012).

Ashkelon Phase 10 (Grid 50, Square 49) has a 2σ calibrated age of 1611–1453 cal BCE. Hence it is younger than the Minoan eruption, though the oldest part of the range slightly overlaps with the youngest part of the calibrated age for the eruption (1646–1603 cal BCE, Manning et al. Reference Manning, Höflmayer, Moeller, Dee, Bronk Ramsey, Fleitmann, Higham, Kutschera and Wild2014). Since Ashkelon Phase 11 is clearly older than the eruption, it might well be that the Minoan eruption occurred during Phase 10. However, more 14C dates of this phase are required to substantiate this preliminary conclusion.

Since radiocarbon dating is not at odds with the investigated parts of Egyptian Dynastic history (Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Rowland, Higham, Harris, Brock, Quiles, Wild, Marcus and Shortland2010; Dee Reference Dee2013a, Reference Dee2013b), the crux of the problem, in our opinion, may be in the correlation between archaeological strata and political history during parts of the 2nd millennium BCE. Indeed, cultural change does not necessarily follow historical change in a coeval manner, as pointed out by Marée (Reference Marée2010) with respect to the Second Intermediate Period. The latter period is missing in the investigation by Bronk Ramsey et al. (Reference Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Rowland, Higham, Harris, Brock, Quiles, Wild, Marcus and Shortland2010), for obvious reasons. Ryholt (Reference Ryholt1997:1) succinctly summed up the problematic nature of this historical period in ancient Egypt: “The Second Intermediate Period, covering the time span between the Twelfth and the Eighteenth Dynasties (c. 1800-1550 B.C.) … is an epoch on which research is still in its pioneer stages. It is not entirely clear how many kingdoms existed during the period, and those that are known are poorly defined insofar as both their territorial and chronological extent remains uncertain.” Indeed, King Khyan for example, linked with the archaeological stratigraphy of Tell el-Dabca (Bietak Reference Bietak2003, Reference Bietak2013, Reference Bietak2015), has been placed in various historical chronological positions within the Second Intermediate Period (Ward Reference Ward1984; Ryholt Reference Ryholt1997; Moeller and Morouard Reference Moeller and Morouard2011). A new study by Höflmayer (Reference Höflmayerforthcoming) gives additional chronological options concerning Khyan that may have considerable effect on archaeo-historical dating. Radiocarbon dating places the Minoan Santorini eruption in the Second Intermediate Period (Bruins Reference Bruins2010).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Lawrence E. Stager of Harvard University, who has directed the Leon Levy expedition to Ashkelon since 1985, for allowing us to select organic samples for 14C dating. We sincerely thank Daniel M. Master, director of the field excavations since 2007, for checking the stratigraphic positions of the samples. Concerning the Middle Bronze Age, we are thankful to Ross Voss, who excavated at Ashkelon during many years since 1985, for evaluating and discussing stratigraphic aspects, also in relation to Tell el-Dabca (Egypt). Last but not least, we express our gratitude to the technical staff at the Center for Isotope Research (University of Groningen) for pretreatment and AMS dating of the organic samples from Ashkelon.