INTRODUCTION

The aim of this study is a complete reassessment and multiple recalibration of all available radiocarbon dates referable to the Early Bronze Age from Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho, one of the best-known and most widely published archaeological sites in the Levant. For this purpose, all available 14C samples (Burleigh Reference Burleigh1981, Reference Burleigh1983; Weinstein Reference Weinstein1984; Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht1998, Reference Bruins and van der Plicht2001; Lombardo et al. Reference Lombardo, Piloto and Calderoni1998; Lombardo and Piloto Reference Lombardo and Piloto2000) have been re-examined by checking their correct setting into the EBA sequence. This also allowed double checking of the new absolute chronology proposed for the Early Bronze Age in the Southern Levant, which included samples from Tell es-Sultan (Regev et al. Reference Regev, de Miroschedji, Greenberg, Braun, Greenhut and Boaretto2012a, Reference Regev, Finkelstein, Adams and Boaretto2014: 258–262).

As Kathleen M. Kenyon demonstrated, stratigraphy is the basic tool for setting the chronology of a site like Tell es-Sultan, with an extraordinarily long occupational history, and the exact location of 14C measured samples it is, thus, decisive to understand its chronological setting. For this reason, the precise location of 14C dated samples from EBA layers at Jericho has been carefully verified, and new samples have been taken and measured from well-defined stratigraphic contexts useful to pinpoint the EBA sequence. Moreover, the archaeological contexts and nature of each sample have been carefully re-examined in order to better understand their chronological implications.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONTEXTS OF THE RADIOCARBON SAMPLES

Tell es-Sultan/Ancient Jericho: A Key Site for Bronze-Age Palestine

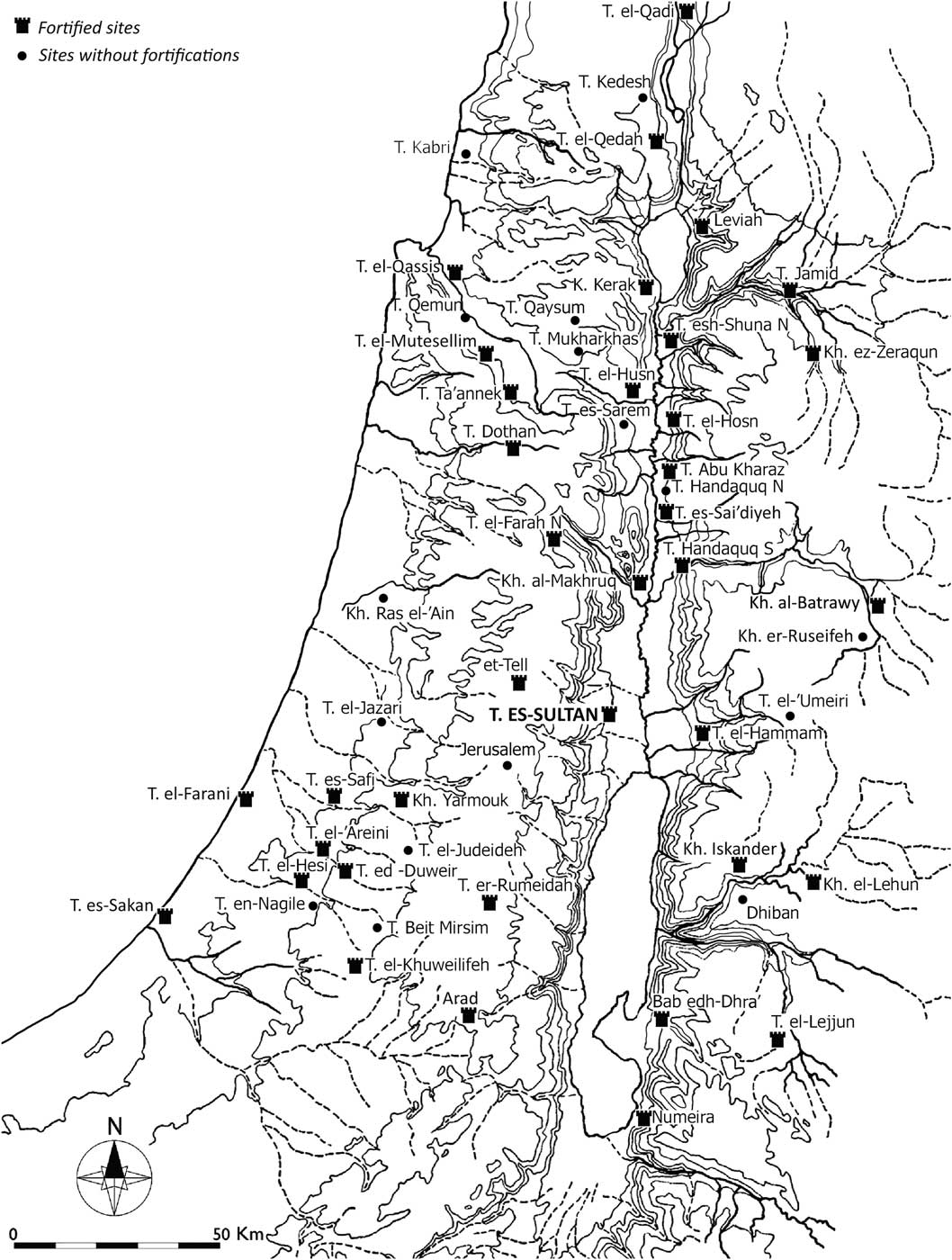

The site of Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho lies around 9 km north of the northern shore of the Dead Sea, 7 km west of the Jordan River, 250 m below sea level (Nigro Reference Nigro2013), at the foot of the Mount of Temptation (Jebel Quruntul) (Figure 1). It was one of most relevant human settlements in the ancient Near East from the Mesolithic/Epipaleolithic through the Neolithic, and one of the earliest to develop into a city at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, with a continuity in the occupational sequence from the Late Natufian (∼10,500 BC) up to the Ottoman Period (1918 AD). The nearby Spring of ‘Ain es-Sultan, which provided 4000–5000 liters of fresh water per minute, ensured life to the community over about 10 millennia (Nigro Reference Nigro2014a: figs. 1.1–1.2).

Figure 1 Map showing the location of Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho and the major EBA Southern Levantine sites.

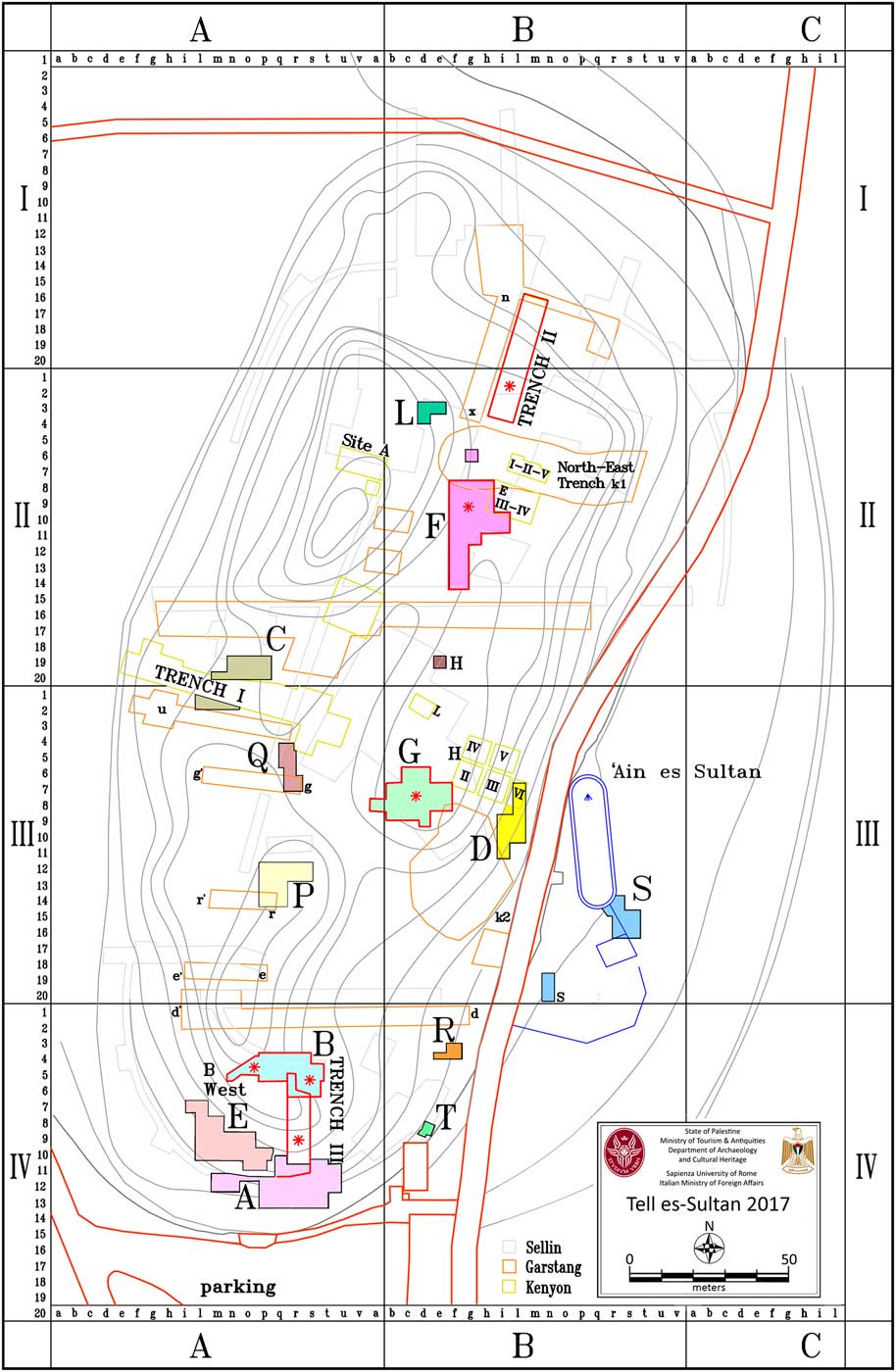

Tell es-Sultan has been the object of archaeological explorations since the beginning of the 20th century: the Austro-German Expedition between 1907 and 1909, directed by E. Sellin and C. Watzinger and fully published in 1913; the first British Expedition between 1930 and 1936, directed by J. Garstang (Garstang and Garstang Reference Garstang and Garstang1948); the second British Expedition between 1952 and 1958, with a distinguished international team directed by Lady Kathleen M. Kenyon, published in five volumes (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1960, Reference Kenyon1965, Reference Kenyon1981; Kenyon and Holland Reference Kenyon and Holland1982, Reference Kenyon and Holland1983). During Kenyon’s excavations at Tell es-Sultan, the stratigraphic digging method became a standard and three major trenches were excavated on the western (Trench I), northern (Trench II), and southern (Trench III) flanks of the tell in order to vertically read the long occupational history of the site. Moreover, for the first time, radiocarbon dates were measured from samples taken from the site (Callaway and Weinstein Reference Callaway and Weinstein1977: 8, 10; Burleigh Reference Burleigh1981, Reference Burleigh1983). In 1997, the joint Italian-Palestinian Expedition resumed excavations at Tell es-Sultan, 40 years after Kenyon’s last season, and during 13 seasons reappraised Kenyon’s stratigraphy, which proved to be largely reliable, even though in some spots strata were missed and in other multiplied. New techniques and horizontal excavations have allowed a drastic increase of the information about the earliest city during the Bronze Age and to double-check contexts and sequences connected to samples recovered to be chronological anchor stones (Nigro Reference Nigro2016, Reference Nigro2017: 159–162).

New excavations documented the rise of the Early Bronze Age city (Nigro Reference Nigro2013: 3–5), its continuous development from the Early Bronze I rural village (Nigro Reference Nigro2005, Reference Nigro2008) to the EB II earliest fortified city, characterized by an impressive fortification system, the presence of public buildings and of extended domestic quarters in EB III (Nigro Reference Nigro2010a, Reference Nigro2010b), until its final dramatic destruction (Nigro Reference Nigro2016, Reference Nigro2017). Furthermore, the main contribution of the Italian-Palestinian Expedition was to put forward a comprehensive stratigraphy of the site, including data produced by all the previous expeditions (Marchetti and Nigro Reference Marchetti and Nigro1998, Reference Marchetti and Nigro2000; Nigro Reference Nigro2005, Reference Nigro2010a; Nigro and Taha Reference Nigro and Taha2009; Nigro et al. Reference Nigro, Sala, Taha and Yassine2011: tab. 1). The Early Bronze Age has been divided into 4 periods, each sub-divided into two sub-periods on the basis of stratigraphy, architecture (major constructional phases of the city-walls and the palace) and associated material culture remains. These periods (Sultan IIIa-d) have been connected to the overall archaeological periodization of ancient Palestine of the EBA (EB I-IV), covering the time span 3500–2000 BC according to traditional chronology (Höflmayer Reference Höflmayer2017: 21–22). Periods Sultan IIIa-d have also been related to Egyptian chronology as summarized on Table 1.

Table 1 Archaeological periodization of Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho in the Early Bronze Age, in relation to the Egyptian chronology, with a specific reference to the stratigraphic sequence of Trench III.

Archaeological Contexts and Stratigraphic Sequence of 14C Samples

A total of 45 14C dates have been determined from different types of samples (charcoals and short-lived charred materials) collected by the two last archaeological expeditions at Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho (Figure 2): the second British Expedition, and the still on-going Italian-Palestinian Expedition started in 1997. This study concerns 32 14C samples already published and 13 new 14C samples collected during the last seasons of excavations (2014 and 2017). Seven samples previously considered reliable have been ruled out because of their scarce accountability [GL-24 (EB IA); BM-548, BM-549, GrA-223 (EB IIA); GrA-225, BM-1783R (EB IIB); BM-1781R (EB IIIB)].

Figure 2 Map of Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho showing the excavated areas. The stars (asterisks) indicate the areas from which 14C samples were collected.

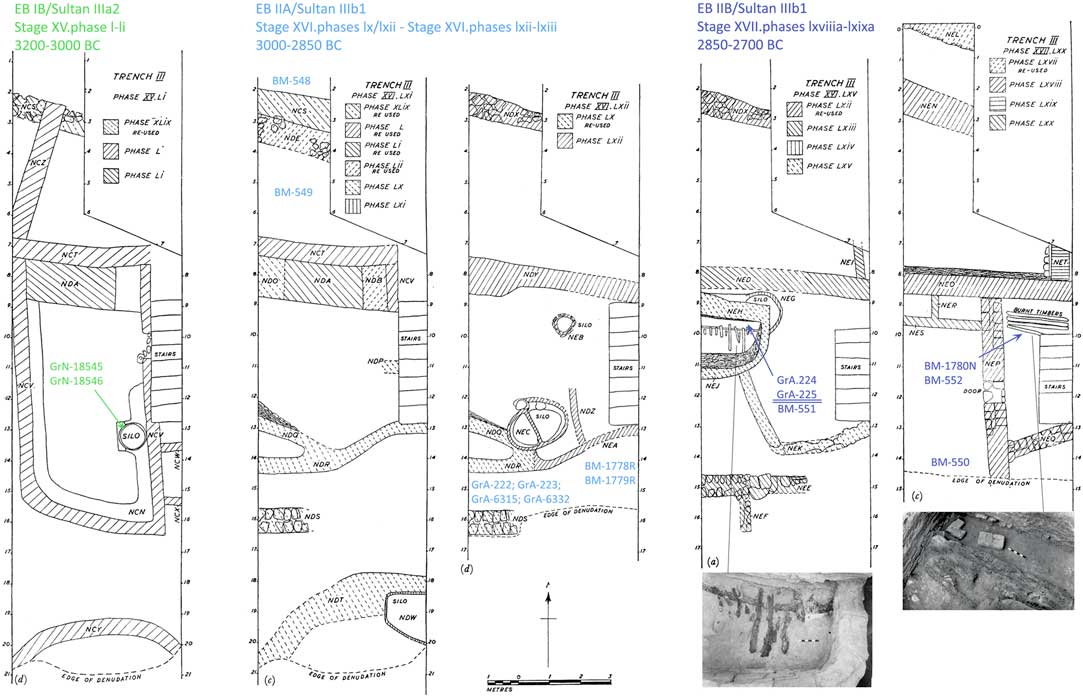

Twenty-nine 14C dates derived from samples collected at Jericho in the 1950s (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981; Kenyon and Holland Reference Kenyon and Holland1983), and published in 1980s and 1990s (Burleigh Reference Burleigh1981, Reference Burleigh1983; Bowman et al. Reference Bowman, Amber and Leese1990; Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht1998, Reference Bruins and van der Plicht2001): 5 samples were collected in Tomb A94, 2 samples were collected in Trench II, and 22 samples were collected in Trench III (Figures 3–4). In this deep cut through the southern flank of the tell, all the four periods representing the Early Bronze Age were documented on both sections in clearly stratified layers (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 193–215, pls. 273–274), firmly connected to the overall stratigraphy of the site (Nigro Reference Nigro2016: table 1). 14C samples from Trench III have been double-checked with a careful micro-stratigraphic re-examination and re-excavation of the trench sections during the last (2017) excavation season. This analysis allowed us to correct stratigraphic errors and to reassessing the stratigraphic distribution of some of the samples.

Figure 3 General view of the southern flank of Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho and the deep cut of Trench III, from south.

Figure 4 East and West Sections of Kenyon’s Trench III with the stratigraphic distribution of 14C samples discussed in this paper.

Three 14C samples were collected in Areas B and F during the first two seasons of excavations (1997–1998) of the Italian-Palestinian Expedition (Marchetti and Nigro Reference Marchetti and Nigro1998, Reference Marchetti and Nigro2000; Lombardo et al. Reference Lombardo, Piloto and Calderoni1998; Lombardo and Piloto Reference Lombardo and Piloto2000).

To these already published dates, 13 14C samples were added by the recent seasons of the Italian-Palestinian Expedition. Five samples were collected in 2014 season in Area G, and further eight samples of charcoals and short-lived organic materials were collected in different areas of the site during the 2017 season: Areas B and B-West, Area F and Trench III.

In this study, 14C samples have been listed according to their archaeological context, set into a carefully verified and documented stratigraphy. The distribution of the available dates across strata, with the exception of 5 EB IA dates from a single tomb in the necropolis (Tomb A94, Kenyon Reference Kenyon1960: 16–40), is the following: 2 dates are from a Sultan IIIa1/EB IA context; 4 dates are from Sultan IIIa2/EB IB contexts; 18 dates are from Sultan IIIb/EB II archaeological layers, namely 11 from Sultan IIIb1/EB IIA contexts, and 7 from Sultan IIIb2/EB IIB layers; 14 samples originate from Sultan IIIc/EB III strata, namely 9 from Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA contexts, and 5 from Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB layers. Finally, 2 more dates are available from Sultan IIId2/EB IVB archaeological deposits.

All dated samples are set in the stratigraphic sequence of Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho as illustrated in Figures 4 and 5, Tables 1–8, and discussed in detail in the following paragraphs.

Figure 5 Stratigraphic distribution of samples collected during Kenyon’s excavations in Trench III from layers dated to Sultan IIIa2/EB IB and Sultan IIIb1-2/EB IIA-B (after Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: pls. 265d, 267c-d, 268a, c).

Table 2 Sultan IIIa1/EB IA 14C dates from Tomb A94 in the Necropolis of Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho and from the Tell itself (Trench III).

Table 3 Sultan IIIa2/EB IB 14C dates from Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho (samples listed according to their stratigraphy=top is a lower/older stratum in the dig).

Table 4 Sultan IIIb1/EB IIA 14C dates from Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho (samples listed according to their stratigraphy=top is a lower stratum in the dig).

* Measurements of the same sample.

Table 5 Sultan IIIb2/EB IIB 14C dates from Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho (samples listed according to their stratigraphy=top is a lower stratum in the dig).

* Two measurements of the same sample.

Table 6 Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA 14C dates from Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho (samples listed according to their stratigraphy=top is a lower stratum in the dig).

* Dates older in respect of the archaeological context and other datings from the same stratigraphic setting.

Table 7 Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB 14C dates from Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho (samples listed according to their stratigraphy=top is a lower stratum in the dig).

* Dates older in respect of the archaeological context and other datings from the same stratigraphic setting.

° Two measurements of the same sample.

Table 8 Sultan IIId2/EB IVB 14C dates from Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho (samples listed according to their stratigraphy=top is a lower stratum in the dig).

METHOD OF ANALYSIS

The published 14C dates have been reanalyzed and calibrated with the IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards and Friedrich2013), using both OxCal program version 4.3.1 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a) and CALIB program version 7.04 (Stuiver et al. Reference Stuiver, Reimer and Reimer2018). All date ranges are given with various relative probabilities due to the wiggles in the calibration curve at that time (ca. 3rd millennium BC).

The 14C samples collected during the 2014–2017 seasons of excavations were measured by accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) at the Centre for Dating and Diagnostics (CEDAD) of the University of Salento in Lecce, Italy. To clean the samples and rid them of any possible contaminants, a preliminary chemical protocol was adopted at the CEDAD chemical laboratories (D’Elia et al. Reference D’Elia, Calcagnile, Quarta, Sanapo, Laudisa, Toma and Rizzo2004). Macroscopic contaminants were removed after observation with an optical microscope. The standard AAA (acid-alkali-acid) protocol was then used to remove any source of contamination. The purified sample material was sealed under vacuum together with CuO in sealed quartz tubes and then combusted at 900°C for 8 hr in a muffle oven in order to extract CO2, which was then reduced to solid graphite at 600°C by using H2 as reducing agent and iron powder as catalyst. The quantity of graphite extracted from the samples was sufficient for accurate experimental determination of age. The 14C concentrations (expressed as 14C/12C ratio) in the extracted graphite were measured by comparing the 12C and 13C ion beam currents, and the 14C counts measured with those obtained from standard samples of C6 (sucrose), supplied by the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency). All 14C ages have been corrected for isotope fractionation by using the measurement of the δ13C values carried out directly with the AMS system, and corrected for sample processing and machine background (Stuiver and Polach Reference Stuiver and Polach1977; Calcagnile et al. Reference Calcagnile, Quarta and D’Elia2005). Finally, samples of known concentration of oxalic acid, supplied by NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology), were used as modern carbon standard to check the results. Conventional radiocarbon ages were then calculated by using the radioactive decay law of 14C. All 14C ages are expressed in conventional 14C yr BP relative to AD 1950, in accordance with the international convention (Stuiver and Polach Reference Stuiver and Polach1977). Conventional radiocarbon ages, as for those already published (see above for the references), were calibrated using the IntCal13 calibration curve and both OxCal v. 4.3.1 and CALIB v. 7.04 programs.

Samples and related data (archaeological contexts, type of materials, 14C ages, and calibrated time ranges corresponding to 95.4 percent probability levels) are presented below in tables separated for each period (from Early Bronze IA to Early Bronze IVB) and always listed in a strictly stratigraphic order.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION: SETTING SULTAN PERIODS IN ABSOLUTE CHRONOLOGY

Early Bronze IA (Period Sultan IIIa1, 3500–3200 BC)

EB IA (Period Sultan IIIa1) at Jericho is represented by five radiocarbon dates from charcoal samples collected in the cremation pile uncovered by Kenyon in Tomb A94; two more samples were collected from silo NDV in Trench III (Table 2).

Tomb A94 is one of the earliest tombs in the Jericho Necropolis, discovered in Area A at the northern edge of the tell (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1960: 16–40). It consisted of a large roughly circular chamber with a central pillar used for supporting the roof and contained multiple secondary burials with long bones piled in the center and skulls aligned along its walls, according to a typical EB IA burial custom (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1957: 96-99). Five 14C samples (GL-24, BM-1328, BM-1329, BM-1774R, BM-1775R) were collected in the cremation pile of long bones in the center of the tomb.Footnote 1 BM-dates from Tomb A94 belonged to two different series of charcoal samples measured in 1977–1978 (BM-1328 and BM-1329) and in 1981 (BM-1774 and BM-1775) in the British Museum 14C Laboratory (Burleigh Reference Burleigh1981: 502; 1983: 762). Some years later a careful re-examination of all the radiocarbon measurements from samples processed in the British Museum 14C Laboratory from 1980 and 1984 revealed a systematic error, as a result of which these dates were roughly 200–300 yr too young (Bowman et al. Reference Bowman, Amber and Leese1990: 59–60; van der Plicht and Bruins Reference van der Plicht and Bruins2001). Some samples could be dated again, including some charcoals from Jericho (revised dates are signalled by letters N or R added to the samples code name: Bowman et al. Reference Bowman, Amber and Leese1990: 62, 74, table 2a). The new 14C dates however showed a larger range of uncertainty (higher that±100), with calibrated age ranges from 400 up to 600 yr (see BM-1774R and BM-1775R). These 14C determinations may show how samples even from sealed archaeological contexts can nonetheless result in strong uncertainties. Nevertheless, these samples provide dates which can be used as termini post quos for the beginning of EB IA/Sultan IIIa1 period.

Two samples of short-lived materials taken from silo NDV in Trench III provided the only available dates from the tell for Sultan IIIa1/EB IA. The installation was plotted by Kenyon in the plan of Stage XVI, however it actually belonged to Stage XIII.phase xlii (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: pl. 265a), underneath wall NCJ visible in the West Section of the Trench (Figure 4). The two samples (GrN-18540 and GrN-18541), measured in the 1990s in Groningen University 14C Laboratory (Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht1998: 627; 2001: 1327–1328), consist of charred grains: namely, GrN-18540 of wheat (Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht1998: 627; 2001: 1327), while GrN-18541 of Emmer (Triticum dicoccum) (Hopf Reference Hopf1983: 595, sample SA 1030). GrN-18540 was dated to 4560±16 BP, while GrN-18541 was dated to 4465±30 BP; the calibrated ranges are between ca. 3370 and 3210 BC, pointing to an advanced phase of Sultan IIIa1/EB IA.

Samples from Tomb A94 came from charcoals which possibly produced an old-wood effect or belonged to items placed in the tomb over a long timeframe; calibrated ranges of these samples all cover a long time span, from ca. 3700 and 3000 BC, which however overlap the conventional chronology of Sultan IIIa/EB I (ca. 3500–3000 BC). In contrast, short-lived samples collected from EB IA contexts from the tell, provide calibrated dates with narrower ranges of uncertainty, which cover a time span apparently corresponding to that of conventional chronology for Sultan IIIa1/EB IA: ca. 3500–3200 BC.

Early Bronze IB (Period Sultan IIIa2, 3200–3050/3000 BC)

The mature Proto-Urban stage (Sultan IIIa2/EB IB), immediately preceding the rise of the city, that witnessed intense contacts with Egypt (Sala Reference Sala2012: 281–284), is of crucial importance in the history of the site during the Early Bronze Age (Nigro Reference Nigro2008). Its chronology can be framed by four dates from samples collected in Trench III (Figures 4–5, Table 3).

Sultan IIIa2/EB IB in Trench III comprises 2 stages, XIV and XV (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 195–202; Nigro Reference Nigro2005: 118, tab. 2). Two samples of charred seeds of unsorted cereal grains (GrN-18545 and GrN-18546) were collected into a brick-lined silo of an apsidal building (NCT+NCV) erected in Stage XV.phase l (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 198–199, pls. 119a-b, 265c-d, 266, 267a-b; Nigro Reference Nigro2005: 118). The apsidal building was completely destroyed in Stage XV.phase li-lii (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 199), and the two samples provided 14C determinations for this event. In the recent revaluation of EBA in Southern Levant (Regev et al. Reference Regev, de Miroschedji, Greenberg, Braun, Greenhut and Boaretto2012a: 537, table 1, fig. 7), Stage XIV.phase xliva and Stage XV.phase li-lii, and consequently the radiocarbon dates related to them, were erroneously attributed to the EB II or even to the EB III, thus resulting in a groundless raising of absolute chronology for these periods. According to a correct interpretation of the stratigraphy of Trench III, Stages XIV-XV correspond to Sultan IIIa2/EB IB. The two samples were measured in the 1990s in Groningen University 14C Laboratory: GrN-18545 was dated to 4530±19 BP; GrN-18546 was dated to 4512±15 BP (Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht1998: 626; 2001: 1325–1326). The calibrated 14C age ranges are between 3240 and 3104 BC. On the basis of the stratigraphy, such 14C determinations can be referred to a central phase of Sultan IIIa2/EB IB.

A further measurement on samples from contexts associated to Sultan IIIa2/EB IB has been conducted in the 2017 season of excavations. Two charcoal samples, LTL17372A and LTL17373A, were collected in Trench III from destruction layers marking the end of Sultan IIIa2/EB IB village (Stage XV.phase lix-Stage XVI.phase lx: Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 202; Nigro Reference Nigro2014b: 70), and measured by CEDAD Laboratory (Figure 6). LTL17372A was dated to 4451±45 BP, LTL17373A was dated to 4445±45 BP. The calibrated ranges of the two samples are between ca. 3190 and 3000 BC. These dates fit with the archaeological dating at about 3150–3000 BC for the final phase of Sultan IIIa2/EB IB, and the end of the period between 3050 and 3000 BC.

Figure 6 Northern edge of Trench III East Section during the 2017 season of excavations, with highlighted the spots from where EB IB samples (LTL17372A and LTL17373A) and EB IIA sample (LTL17369A) were collected.

Early Bronze IIA (Period Sultan IIIb1, 3050/3000–2850 BC)

Eleven dates come from samples collected in stratified layers of Trench III (Figures 4–5, Table 4) dating to the initial urban phase of Sultan IIIb1/EB IIA, when the impressive mud-brick city walls of Jericho were erected.

Sultan IIIb/EB II in Trench III comprises 2 stages (XVI, XV) distinguished by Kenyon (Reference Kenyon1981: 204–209), corresponding to the two main EB II sub-periods (Sultan IIIb1-2/EB IIA-B) identified by the Italian-Palestinian Expedition in Areas F and G (Nigro Reference Nigro2010a: tab. 1.1). The earliest one, Sultan IIIb1/EB IIA (= Stage XVI.phases lx/lxvii, Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 202–206; Nigro Reference Nigro2010a: 105), was erroneously considered the final phase of EB II (Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht1998: 627; 2001: 1328–1329) and even attributed to EB III (Regev et al. Reference Regev, de Miroschedji, Greenberg, Braun, Greenhut and Boaretto2012a: 537, table 1, fig. 7). This mistake, originating from a lack of knowledge of stratigraphy and associated finds, resulted in an incorrect dating of both EB II and EB III. As a correct interpretation of stratigraphy and finds (e.g. Nigro Reference Nigro2010a: 110, pls. LI:4-5, 9-10, LII: 3, 8, LIII: 4-5, 11 LIV: 1-2) suggests, Stage XVI definitely marks the beginning of EB II and not its end. In this period, new domestic structures were built on the southern terraced slope of the tell. 14C samples collected from Stage XVI layers (Table 4) and the descending chronological indications are discussed below.

Sultan IIIb1/EB IIA is represented by six dates from samples collected in destruction layers associated to a seismic shock occurring during the EB IIA (Stage XVI.phase lxii-lxiii). Two high-precision series of dates were made on such samples in the British Museum and Groningen laboratories. Charcoal samples were examined in London (BM-dates), while short-lived samples of charred seeds of weeds in Groningen (GrA-dates). BM-1778R and BM-1779R, redated in 1990s (Bowman et al. Reference Bowman, Amber and Leese1990: 74, table 2a), were collected on the southern terrace (Kenyon and Holland Reference Kenyon and Holland1983: xxxvii), as shown in the East Section (Figure 4), which however gave a large range of uncertainty like as the other BM-samples redated in the 1990s (see Table 2). The four remaining 14C dates (GrA-222, GrA-223 rep. 1, GrA-6315 rep. 2, GrA-6332 rep. 3) were obtained from charred seeds of weeds (Hopf Reference Hopf1983: 595–596, SA-739).Footnote 2 GrA-222, GrA-6315 rep. 2, GrA-6332 rep. 3 gave very similar dates (Table 4), consistent with the 14C ages of BM-1778R and BM-1779R, from the same context.Footnote 3 These three dates from short-lived samples were averaged (Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht2001: 1328), and the resulting calibrated date is 3025–2902 (93.9%) cal BC.

In the 2017 season, three charcoal samples were collected from the East and West Sections of Trench III (Figure 6), and then measured by CEDAD Laboratory (LTL17369A, LTL17370A and LTL17371A). These samples come from a destruction layer of the end of Sultan IIIb1/EB IIA (Stage XVI.phase lxvii). LTL17370A was dated to 4323±45 BP, LTL17371A to 4317±45 BP, LTL17369A to 4276±45 BP; the calibrated ranges for these samples are between 3029 and 2858 BC. These dates are quite consistent with those obtained from the other samples from Stage.XVI.

Calibrated dates from reliable samples collected in Sultan IIIb1/EB IIA contexts fall within the range of conventional archaeological chronology pointing to a date for Sultan IIIb1/EB IIA period between ca. 3050/3000 and 2850 BC.

Two more dates should be added to the Sultan IIIb1/EB IIA determinations. Samples collected in 2017 season from charred wooden beams inserted into the Sultan IIIc/EB III fortification walls in Area B (LTL17382A) and Area B-West (LTL17381A) gave dates consistent with the chronology of Sultan IIIb1/EB IIA (Table 6). These dates could confirm the hypothesis that the EB III city-walls were built incorporating the pre-existing Sultan IIIb/EB II defensive line not only on the northern and western sides of the tell (Nigro Reference Nigro2010a: 12–19, 22–34), but also on the southern side, where the EB II city-wall has never been clearly identified (Nigro Reference Nigro2010a: 21).

Early Bronze IIB (Period Sultan IIIb2, 2850–2700/2650 BC)

The late phase of Early Bronze II (Sultan IIIb2/EB IIB) is illustrated by seven dates from samples collected during Kenyon’s excavations (Table 5). One sample (BM-1783R) came from Trench II and belonged to Stage XVIII.Footnote 4 Six dates were obtained from samples collected in Trench III and associated to Stage XVII (Figures 4–5). Stage XVII was erroneously considered an early phase of the following EB III period (Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht1998: 627; 2001: 1329; Regev et al. Reference Regev, de Miroschedji, Greenberg, Braun, Greenhut and Boaretto2012a: 537, table 1, fig. 7), again with an unjustified raising of its absolute chronology. In Trench III, Sultan IIIb2/EB IIB is represented by a rectangular house (NEP+NEQ), built on the southern terrace, which remained in use during the whole Stage XVII (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 207, pl. 268c, 269a; Nigro Reference Nigro2010a: 106). Once again, two high-precision series of measurements were made on samples of charcoals (BM-550, BM-551, BM-552 and BM-1780N), and of short-lived organic materials (GrA-224 and GrA-225), all of them associated to the same stratigraphic phase (Stage XVII.phases lxviiia-lxixa), and collected in well stratified layers, as the finding spot is clearly buried under the earliest Sultan IIIc/EB III massive mudbrick city-walls (Nigro Reference Nigro2010a: fig. 4.49).

BM-1780N and BM-552 were charcoals sampled from burnt timbers excavated in the eastern room of the domestic unit, south of Wall NEO (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: pl. 268c) (Figures 4–5). These samples gave two quite different 14C ages (Bruins and van der Plicht Reference Bruins and van der Plicht1998: 625): BM-1780N was dated to 4320 ± 50 BP, the calibrated date is 3037–2877 (88.3%) cal BC OxCal and/or 3036–2877 (93%) cal BC CALIB; BM-552 was dated to 4115 ± 39 BP, calibrated date is 2780–2575 (70.0%) cal BC OxCal and/or 2780–2574 (73%) cal BC CALIB. However, it seems possible that the charcoals sampled for the 14C determinations belonged to timbers from trees cut in chronologically successive circumstances and then resulting in different dates. BM-1780N can be used as a terminus post quem in relation to the beginning of Sultan IIIb2/EB IIB.

GrA-224 and GrA-225 represent two different measurements made on a sample of charred onion bulbs (Allium sp.; Hopf Reference Hopf1983; SA-704, Jp.N. 5.30), from layers associated to Stage XVII.phase lxviiia-lxixa. According to Kenyon these layers “were accumulated in the western room … [of the domestic unit] … sagged into the fill of the silo NEH-NEJ” (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 207). A possible stratigraphic error occurred here. A pit existed from where BM-551 was taken as it is clearly visible in West Section (Figure 4). It was therefore erroneously attributed to Stage XVI.phase lxv-lxvi, while it should be associated to the later Stage XVII.phase lxviiia-lxixa (Table 5). BM-551, in facts, produced a date younger than samples GrA-224 and GrA-225, collected from layers at a higher elevation, but stratigraphically older (Figure 5). GrA-224 and BM-551 gave two quite similar 14C ages, this would suggest to rule out GrA-225.Footnote 5

Calibrated dates of samples from Sultan IIIb2/EB IIB contexts range between ca. 2870 and 2600 BC. Such radiocarbon determinations approximately fit with the archaeological-historical periodization for Sultan IIIb2/EB IIB ranging between ca. 2850 and 2650 BC.

A further date should be added to the Sultan IIIb2/EB IIB determinations. BM-554, collected during Kenyon’s excavations in Trench III, was sampled from a charcoal inserted in the mud-brick superstructure of the Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB fortification walls and associated to the final destruction at the end of EB IIIB (Table 7). However, this gave a date consistent with the chronology of the other Sultan IIIb1/EB IIB samples, and should belong to building materials employed in the earliest Sultan IIIb/EB II defensive line then reused in the later Sultan IIIc/EB III reconstructions of the fortification walls.

Sultan IIIb2/EB IIB ended with a severe destruction due to a terrible earthquake (Nigro Reference Nigro2014b: 72), which completely destroyed the city (Stage XVII.phase lxxi-Stage XVIII.phase lxxii), and was followed by a clearly different phase characterized by the erection of the EB III double city-walls (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 207–209, pls. 268c, 269; Nigro Reference Nigro2010a: 106–110). This stratigraphic caesura is neatly distinguishable all over the tell and can be dated, on the grounds of the above mentioned radiocarbon determinations, at about 2700/2650 BC.

Early Bronze IIIA (Period Sultan IIIc1, 2700/2650–2500 BC)

The absolute chronology of Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA at Jericho is based on nine dates from samples collected in different areas of the site. One sample (BM-553) was collected during Kenyon’s excavations in Trench III (Figure 4). A further eight samples were collected during the Italian-Palestinian excavations (2014-2017) in the areas where the remains of the EB IIIA city were brought to light: Area B (LTL17382A); Area B-West (LTL17381A); Area F (LTL17383A); Area G (LTL14952A, LTL14953A, LTL14954A, LTL14955A, LTL14956A) (Figure 2, Table 6).

Three samples (BM-553, LTL17381A, LTL17382A) originate from layers associated to the beginning of Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA, and related to the erection of the first EB III fortifications.

Period Sultan IIIc1-2/EB IIIA-B in Trench III comprises 2 different stages (XVIII and XIX). Stage XVIII belongs to Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA; in this stage Town Walls NFB and NFD, respectively the Inner and Outer City-Wall of the double fortification system, were erected (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 209–212, pl. 269b; Nigro Reference Nigro2006a: 361–375, tab. 2). BM-553 was collected from burnt timbers incorporated into Town Wall NFB (Stage XVIII.phase lxxii). It was dated to 3922 ± 78 BP, calibrated date is 2622–2196 (94.2%) cal BC OxCal and/or 2620–2196 (99%) cal BC CALIB. This sample, although burnt at the end of EB IIIB, and thus collected in a later stage, due to the old-wood effect (meaning that it was cut well before being burnt, presumably when it was set into the structure as architectural element), would suggest a date around 2620 BC. This date may be considered approximately that of the reconstruction of the city-wall where the sample was found, that is the beginning of Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA.

LTL17382A and LTL17381A were collected by the Italia-Palestinian Expedition in 2017 season respectively in Area B and Area B-West (Figure 7), where a stretch of the southwestern corner of the Sultan IIIc1-2/EB IIIA-B double city-walls was brought to light (Nigro Reference Nigro1998a: 32–46; 1998b: 89–91; Nigro and Taha Reference Nigro and Taha2009: 738–739, figs. 14–15; Nigro et al. Reference Nigro, Sala, Taha and Yassine2011: 580–581).

Figure 7 General view of Areas B and B-West, with Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB Building B1 (to the left), the EB IIIA-B double city-walls (to the right), from north.

Stratigraphy in Area B, as reconstructed by the Italian-Palestinian Expedition, comprises 5 phases (Activities 5-1): Activities from 5 to 3 are connected to Sultan IIIc/EB III, Activity 2 represents the Middle Bronze Age, while Activity 1 corresponds to modern disturbance and excavation activities. At the beginning of EB IIIA, the double city-wall fortification system was built (Nigro Reference Nigro1998a: 36–39, fig. 1.10; 2006a: 361–373): it consisted of a Main Inner City-Wall (Wall 2, prosecution of Kenyon’s Wall NFB) and an Outer City-Wall (Wall 56, Kenyon’s Wall NFD), with a blind room in between filled up with crushed and pulverized limestone. A gate (South Gate L.1800), discovered in the 2010 season, was opened through the Main Inner City-Wall during the EB IIIA (Nigro et al. Reference Nigro, Sala, Taha and Yassine2011: 580–581, figs. 10–11; 2016: 9), and this was obliterated at the end of the period after a dramatic collapse due to a fierce fire (Nigro Reference Nigro2014b: 75). LTL17382A was collected from the carbonized collapsed beam of Palestinian tamarisk (Tamarix sp.) used as lintel of the gate and found collapsed inside the passageway.

Stratigraphy in Area B-West comprises 5 phases (Activity 5-1), from the earliest EB III strata (Activities 5-4) to the latest Middle Bronze (Activity 3) and modern strata (Activities 2-1). Activity 5/Operation 5c belongs to Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA (Nigro Reference Nigro1998b: 84), and is represented by the erection of the Main Inner City-Wall (Wall 2, like in the nearby Area B) and Outer City-Wall (Wall 56). After the EB IIIA destruction (Activity 5/Operation 5b), the double city-walls were completely reconstructed in the successive Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB (Activity 5/Operation 5a): the Main Inner City-Wall was refurbished (Wall 1, prosecution of Kenyon’s Wall NFG), and the Outer City-Wall (Wall 51, prosecution of Kenyon’s Wall NFJ) was rebuilt and moved inwards (Nigro Reference Nigro1998b: 85, 90–91). LTL17381A was collected during the 2017 season from charred beams inserted at the bottom of Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA Inner City-Wall (W.2) to ensure air circulation and structural linkage to the massive mud-brick superstructure upon its stone foundation (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Tell es-Sultan/Jericho, Area B-West: location of sample LTL17381A collected from a carbonized wooden beam set across the Main Inner City-Wall (W.2) just upon its stone foundation, from northwest.

LTL17382A and LTL17381A gave dates older than their recovery contexts. More specifically, LTL17382A was dated to 4421 ± 45 BP, calibrated as 3127-2916 (69.3%) cal BC OxCal and/or 3126-2916 (73%) cal BC CALIB; LTL17381A was dated to 4376 ± 45 BP, calibrated as 3105–2894 (93.1%) cal BC OxCal and/or 3105–2895 (96%) cal BC CALIB. Both dates overlap a time range respectively from ca. 3120–2900 BC and ca. 3100–2890 BC, the same as for the EB IB-EB II samples (see Tables 3–5). However, the tamarisk wood beam of the gate (Area B) and the wooden beams inserted in the superstructure of the city-wall (Area B-West) might have been cut and set into the wall when it was first erected in Sultan IIIb1/EB IIA (the 14C date obtained thus refers to this time), to be subsequently reused when the fortifications were rebuilt in Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA, and finally burned when the city fortifications were set on fire at the end of Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB.

Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA is also represented by six samples collected in Areas F and G. Their stratigraphic location and the associated EB IIIA material culture is known (including Khirbet Kerak Ware, Nigro Reference Nigro2009: 72–74).

Area F was opened on the northern plateau of the site, where a large portion of the Sultan IIIb-c/EB II-III domestic quarter (Figure 9), extending to the west and to the east of a major street running northeast, was brought to light (Nigro Reference Nigro2000a: 15–51; 2006b: 10–17; Nigro and Taha Reference Nigro and Taha2009: 740–741, fig. 17).Footnote 6 Stratigraphy of Area F comprises 6 phases (Activities 6-1): Activities from 6 to 3 cover the Early Bronze Age, respectively EB II, EB IIIA-B and EB IV, while the latest two activities represent the Middle Bronze Age (Activity 2) and the modern frequentation (Activity 1). Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA houses, extensively excavated by the Italian-Palestinian Expedition (Nigro Reference Nigro2000b: 16-17), revealed a long stratigraphic sequence (Activity 5/Operations 5e-a) which ended with a destruction (Activity 5/Operation 5a). Two samples (LTL17383A, LTL17384A) were collected during the 2017 season in the layer of use (F.1290) of a house dated to Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA. LTL17383A was dated to 4154 ± 45 BP, while unfortunately it was not possible to date a short-lived sample (olive stone) from the same context (LTL17384A).

Figure 9 Tell es-Sultan/Jericho, Area F: general view of the EB II-III domestic quarter excavated on the northern plateau, from northwest.

Area G is located on the eastern flank of the Spring Hill, where a Sultan IIIb-c/EB II-III complex building, called Palace G, was brought to light and carefully investigated by the Italian-Palestinian Expedition (Figure 10). Upon the EB Palace scanty remains of the Sultan IIId1/EB IVA camp site (Nigro Reference Nigro2003: 130–131) were uncovered, drastically obliterated by the structures of the Middle Bronze II Palace, the so-called Hyksos Palace (Nigro et al. Reference Nigro, Sala, Taha and Yassine2011: 585-586). Palace G was erected on three terraces at the beginning of Sultan IIIb/EB II, reconstructed during Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA, and destroyed at the end of Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB by a fierce fire (Marchetti Reference Marchetti2003: 300–303, fig. 4; Nigro Reference Nigro2006b: 20–22, figs. 29–32; 2014b: 77–79; 2016: 10, figs. 8–9; 2017: 159–161, 164–165; Nigro et al. Reference Nigro, Sala, Taha and Yassine2011: 586–592). The thick destruction layers inside the rooms of the palace yielded a wealthy EB IIIB ceramic assemblage, and special finds such as ceremonial vessels, seal impressions, metal weapons (Nigro et al. Reference Nigro, Sala, Taha and Yassine2011: figs. 18–21).

Figure 10 Tell es-Sultan/Jericho, Area G: general view of Sultan IIIc/EB III Palace G, from east.

Five 14C samples (LTL14952A, LTL14953A, LTL14954A, LTL14955A, LTL14956A), collected in the 2014 season (Figure 11), belonged to charred beams of a wooden installation (B.1238) excavated in Room L.1224 and associated to the Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA reconstruction of the Palace. LTL14955A, LTL14953A, LTL14956A, LTL14954A, and LTL14952A dated respectively to 4113±45 BP, 4080 ± 40 BP, 4076 ± 40 BP, 4035 ± 40 BP, and 4009 ± 40 BP. Although found in the same context, these charcoals resulted in different dates, corroborating the interpretation that they belonged to timbers from trees cut in a chronologically successive sequence (Table 6).

Figure 11 Sampling of charcoals in Palace G, Room L.1224 (Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA), during the 2014 season of excavations.

Calibrated dates from samples collected in Areas F and G in Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA strata range between ca. 2880 and 2460 BC, which approximately overlap with the conventional archaeological dating ∼2700–2500 BC for this period.

Early Bronze IIIB (Period Sultan IIIc2, 2500–2300 BC)

EB IIIB (Period Sultan IIIc2) at Jericho is illustrated by five radiocarbon dates based on samples collected in different areas of the site. Two samples (BM-554, BM-1781R) were collected in Trench III (Figure 4); two samples (Rome-1177, Rome-1178) were collected in Area F and one sample (Jericho 1) in Area B by the Italian-Palestinian Expedition at the end of 1990s (Table 7).

Rome-1177 and Rome-1178 (Lombardo and Piloto Reference Lombardo and Piloto2000) were associated to Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB (Activity 4) according to the stratigraphic sequence of Area F. They originate from a filling which sealed the Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA destruction layers, which yielded diagnostic EB IIIA pottery fragments (Nigro Reference Nigro2000b: 29–31, figs. 1:32–38), among which some Khirbet Kerak Ware fragments (Nigro Reference Nigro2000b: 29, fig. 1:39; 2009: 72–74, figs. 7–8). Rome-1177 was dated to 3890 ± 60 BP, while Rome-1178 was dated to 3875 ± 60 BP: the corresponding calibrated dates range between 2495 and 2195 BC, which overlap the time span ∼2500–2300 BC archaeologically established for Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB.

BM-554 and BM-1781R were found in the destruction layers which marked the end of Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB, when the fortified city of Jericho was completely destroyed probably by an enemy attack (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 213; Nigro Reference Nigro2014b: 77–80, figs. 20–23; 2017: 164–166). Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB in Trench III corresponds to Stage XIX, when the fortification system was completely rebuilt for the last time (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 212–213, pl. 270a; Nigro Reference Nigro2014b: 75–77) after the destruction occurred at the end of Sultan IIIc1/EB IIIA (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 212, pl. 124b). BM-554 and BM-1781R were obtained from the same sample of charcoal and associated to Stage XIX.phase lxxvi-lxxviia, namely the end of Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB (Kenyon and Holland Reference Kenyon and Holland1983: xxxviii).Footnote 7 BM-554 was dated to 4170±42 BP, calibrated date is 2887–2626 (95.4%) cal BC using OxCal and/or 2824–2626 (78%) cal BC using CALIB. This date is older than its recovery context, namely the EB IIIB destruction layers, but is consistent with the other dates of Sultan IIIb2/EB IIB. As already noted for charcoal samples taken from the fortification walls (e.g. LTL17381A and LTL17382A), building materials (wooden posts and timbers) of the earliest Sultan IIIb/EB II defensive line may have been reused when the city-walls were rebuilt during Sultan IIIc/EB III, remaining embedded in the mud-brick superstructure until the final destruction of the EB IIIB city.

Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB in Area B was associated with the reconstruction of the Main Inner City-Wall (Wall 1, prosecution of Kenyon’s Wall NFG), which was repaired in various spots (Nigro Reference Nigro1998a: 36) incorporating the blocked South Gate (Nigro Reference Nigro1998a: 36; Nigro et al. Reference Nigro, Sala, Taha and Yassine2011: 581). In the same phase, Building B1 was erected against the inner side of the fortification wall (Nigro Reference Nigro1998a: 24–25; 2000a: 122). Building B1 was completely destroyed at the end of Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB (Activity 4/Operations 4c-a), as it is shown by its walls ruinously collapsed and by the thick destruction layers which filled up all the rooms (the same event is also visible in cracks and subsided sections of the nearby city-walls; Nigro Reference Nigro1998a: 25–26; 2000a: 122–123). Sample Jericho 1 was retrieved in the destruction layer which filled up Room L.39 (filling L.39c) when Building B1 was set on fire (Lombardo et al. Reference Lombardo, Piloto and Calderoni1998: 242). Jericho 1 was a charcoal from a timber set in the ceilings of the building, and may thus be referred to the Building B1 construction at the beginning of Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB (Nigro Reference Nigro1998a: 41). It was dated to 4000±60 BP, and the calibrated date is 2694–2337 (90.6%) cal BC OxCal and/or 2680–2336 (95%) cal BC CALIB. This sample, thus, would provide a chronological indication which coincides with archaeologically established conventional dates for Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB between ca. 2650 and 2300 BC. However, further short-lived samples are still needed to provide a reliable date of the destruction of the Early Bronze Age city at the end of Sultan IIIc2/EB IIIB, which ranges from 2350 to 2250 BC.

Early Bronze IVA-B (Period Sultan IIId1-2, 2300–2000/1950 BC)

There are no Sultan IIId1/EB IVA samples available from the tell, where this phase was identified in relatively restricted areas (Nigro Reference Nigro2003: 132).

The overlying Sultan IIId2/EB IVB is represented only by two charcoal samples collected during Kenyon’s excavations in stratified layers from Trench II and Trench III, associated to the latest EB IV occupation.

In Trench III, the latest Sultan IIId/EB IV occupation is illustrated by Stage XX and Stage XXI (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 213–215, pl. 273). BM-1782R was retrieved in layers associated to Stage XX.phase lxxxa, and related to a ditch, suggesting the existence of a village on the top of the mound, with dwellings spread to the north and to the south of the ditch (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 214; Nigro Reference Nigro2003: 129).

The same stratigraphic phase in Trench II corresponds to Stage XXI.phase lxviii (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 166–167; Nigro Reference Nigro2003: 128), that includes houses built on top of the northern EB IIIB Outer City-Wall in the latest phase of the period (Sultan IIId2/EB IVB). The post-urban rural village was destroyed by an earthquake at the end of EB IVB (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1981: 167; Nigro Reference Nigro2003: 131–133). BM-1784R was collected from the collapse layer (Stage XXI.phase lxviii-Stage XXII.phase lxixa) marking the end of the EB IVB settlement at Jericho.

The two samples provided very similar dates (Table 8): BM-1784R was dated to 3840 ± 110 BP, BM-1782R was dated to 3780 ± 110 BP. The calibrated dates overlap a time range between 2580 and 1907 BC. With a view to collecting further samples from EB IV contexts, these measurements suggest for the final phase of occupation of the Sultan IIId2/EB IVB village a latest date around 2000/1950 BC.

CONCLUSIONS

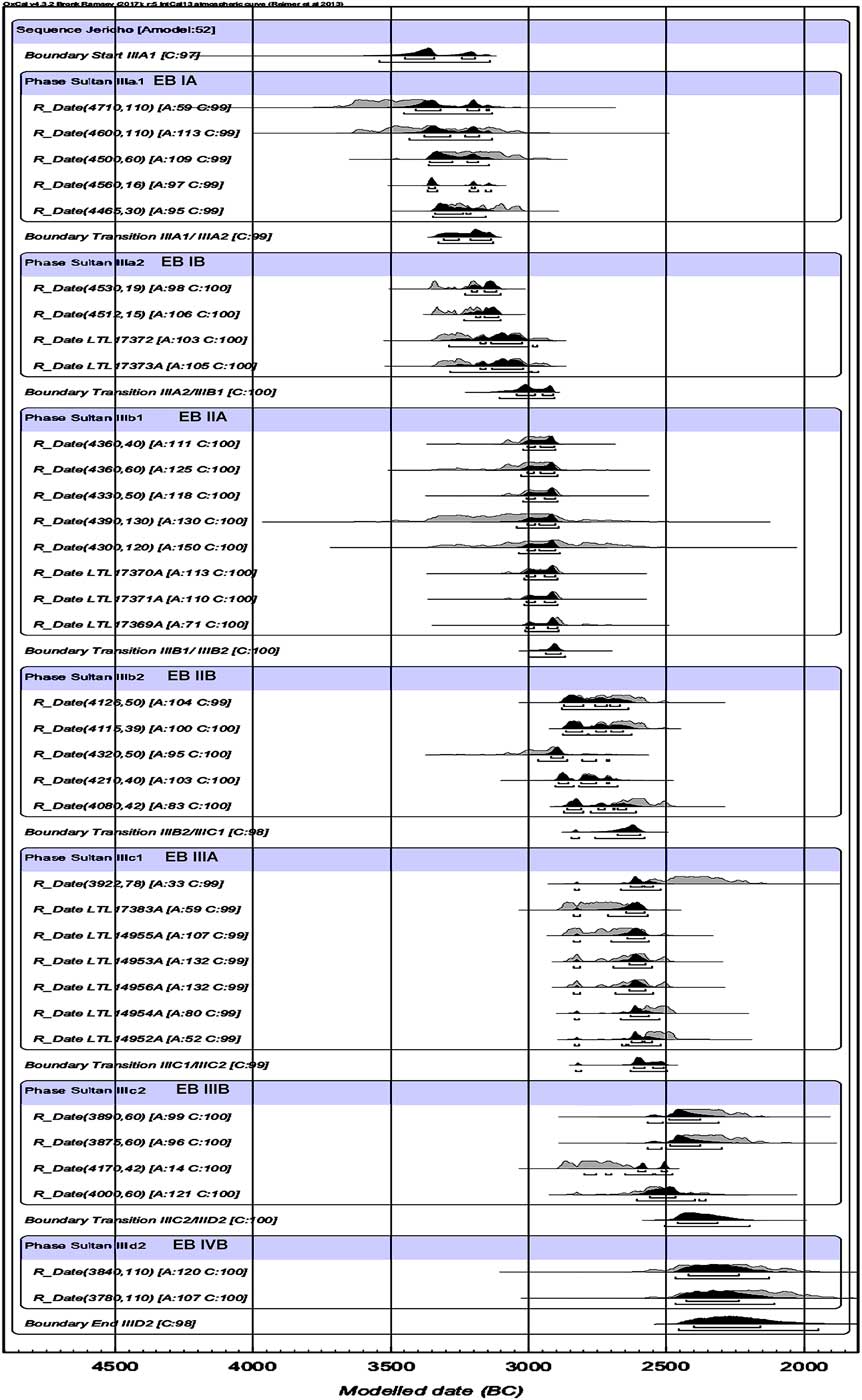

Re-examination of 14C dates available for Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho in the EBA (summarized in the multiple plot, Figure 12) has shown that archaeological periods (Table 9) and chronological divisions based on stratigraphic analysis and material culture sequences and associations can be matched with dates provided by 14C determinations. Whether the two systems keep their independence avoiding circular reasoning, the reassessed radiocarbon dates in relation to careful verified stratigraphic location of samples (e.g. from the beginning, mid or end) for each period may allow a more precise setting of archaeological periods and even highlight excavation or interpretive misunderstandings.

Figure 12 Multiple plot of Jericho Early Bronze Age 14C dates (OxCal v. 4.3.1).

Table 9 Archaeological periodization of Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho and the radiometric reassessed chronology.

At Jericho, archaeologists clearly marked in stratigraphy the inner subdivisions of each period, even though this is not always reflected in an obvious manner by material culture. These sub-periods have been tentatively dated thanks to available radiocarbon dates anchored to strata as shown in Table 9 thanks to Bayesian tools.Footnote 8

This absolute chronology of Tell es-Sultan/Jericho in the EBA contradicts the recently-proposed Levantine High Chronology (Regev et al. Reference Regev, de Miroschedji, Greenberg, Braun, Greenhut and Boaretto2012a, Reference Regev, de Miroschedji and de, Boaretto2012b, Reference Regev, Finkelstein, Adams and Boaretto2014; Höflmayer et al. Reference Höflmayer, Dee, Genz and Riehl2014; Falconer and Fall Reference Falconer and Fall2016; Regev Reference Regev2017). The latter, as far as Jericho is concerned, was based on some major misunderstandings of Kenyon’s stratigraphy—and in a complete oblivion of what was more precisely established by the Italian-Palestinian Expedition. Henceforth, the results of the present study suggest maintaining the already-established chronological relationships between Jericho and Palestine with Pre- and Early Dynastic Egypt.

Moreover, this study has made clear once again how many perils are concealed in the use of 14C to date stratigraphies and related archaeological chronologies. Different types of samples have different kinds of relationships with stratigraphy—with a special mention to the old-wood factor which can quite often occur in a site with monumental defensive structures built up and destroyed many times. Moreover, errors can also occur during samples chemical treatment before measurement, as some cases in the British Museum and Oxford Laboratories (and following re-measurements) have shown (Bowman et al. Reference Bowman, Amber and Leese1990; Waterbolk Reference Waterbolk1990; van der Plicht and Bruins Reference van der Plicht and Bruins2001: 1162).

In any case, the most dangerous and hazardous challenge has been that brought about by an indirect knowledge of stratigraphy, as the chronological implications of a sample mostly rely on its stratigraphic exact location and understanding. For this reason, plans, sections and photos, when available, of samples in situ are mostly needed and have been included in this study. In many cases, 14C determinations helped in better understanding stratigraphy.

Even though the result of this study, as summarized above in Table 9, are considered soundly reliable, as they stem from a multi-based approach to chronology and are the outcome of a pluriannual work at Tell es-Sultan, a further collection of precisely located samples and measurements is needed to double-check our preliminary time indications with new evidence, which may also be verified by means of further Bayesian interpretive models.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities of the State of Palestine for letting possible the joint Italian-Palestinian Pilot Project at Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho from 1997 and allowing analyses upon finds, the results of which are illustrated in the present paper. Our gratitude is addressed to: H.E. the Minister Rula Maa’yaa, the Director General of the Excavations Dr. Jehad Yasin; Dr. Saleh Tawafsha; Dr. Iyad Hamdan, the responsible of the site of Tell es-Sultan (Ariha province), and Mohammed Mansour for their invaluable help to the work of the Expedition. A special thank is addressed to the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affair, the DGSP – Ufficio VI Settore Archeologia, and the Italian Consulate in Jerusalem, which strongly supported our scientific commitment in Palestine. The academic authorities of Sapienza University of Rome, the Magnificus Rector Prof. Eugenio Gaudio, the Dean of the Faculty of Letters, Prof. Stefano Asperti, the Pro-Rector for Scientific Research, Prof. Teodoro Valente, the Pro-Rector for Internationalization, Prof. Bruno Botta, for the generous funding of the Jericho Project, and the Director and the Administrative Secretary of the Dept. of Oriental Studies, Prof. Alessandra Brezzi and Dr. Claudio Lombardi, for their scholarly and technical support.