INTRODUCTION

The Arctic region of Western Siberia has a rich archaeological record, particularly for the Late Holocene, with perhaps the most widely known site in this region being Ust’-Polui. Located just above the Arctic Circle at the southern end of the Yamal Peninsula (Figure 1), this Iron Age site was first discovered in 1932 and then excavated in 1935–1936, 1946, and 1991, with the most recent period of excavations occurring from 1993 to 1995, and 2006 to 2015 (Adrianov Reference Adrianov1936a, Reference Adrianov1936b, Reference Adrianov1936c; Moshinskaia Reference Moshinskaia1953, Reference Moshinskaia1965; Fedorova and Gusev Reference Fedorova and Gusev2008; Gusev and Fedorova Reference Gusev and Fedorova2012). This long history of excavation at Ust’-Polui, and the intermittent presence of permafrost at the site, has resulted in the recovery of over 50,000 artifacts, several sets of human remains, and a very large faunal assemblage (Chernetsov and Moszyńska Reference Chernetsov and Moszyńska1974; Fedorova and Gusev Reference Fedorova and Gusev2008; Gusev and Fedorova Reference Gusev and Fedorova2012; Razhev and Poshekhonova Reference Razhev and Poshekhonova2012; Vizgalov et al. Reference Vizgalov, Kardash, Kosintsev and Lobanova2013). Ust’-Polui is perhaps most notable because it has produced possible early evidence for reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) keeping in the Arctic, including multiple artifacts that seem to be parts of reindeer headgear or bridles (Gusev et al. Reference Gusev, Plekhanov and Fedorova2016).

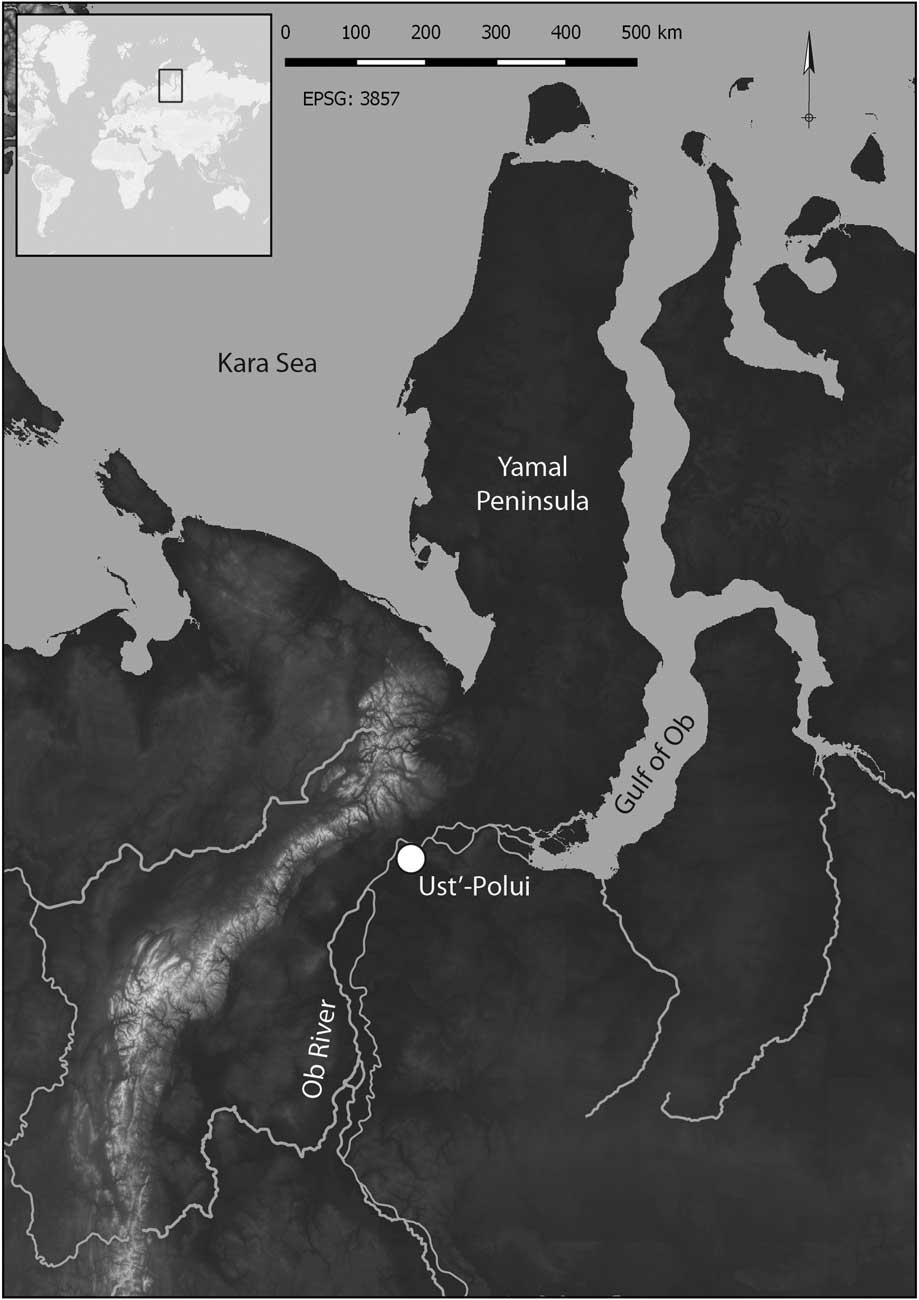

Figure 1 Map of the study area (66.5576 N, 66.5605 E), with the location of Ust’-Polui and major geographical features indicated. The map was created using Landsat open access data, courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Our initial interests in Ust’-Polui were not the reindeer-related items there, but rather the roles of the dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) at this site and the various practices involved in keeping them. Well over 100 dogs are represented at Ust’-Polui, mostly as disarticulated skeletal elements found scattered among other faunal remains and artifacts. Moszyńska (Reference Moszyńska1974) argued that the abundance of dog remains, the presence of antler swivels (possible tethering equipment), and a knife handle decorated with a possible depiction of a dog wearing a harness, all indicated that dog sledding was practiced at Ust’-Polui. Sacrifice of dogs was also said to have occurred here, evidenced by 15 dog skulls found in single concentration in 1935, all without their mandibles and having their brain cases fractured open (Moszyńska Reference Moszyńska1974). Further, the more recent excavations at Ust’-Polui have uncovered articulated whole skeletons of several dogs that were intentionally buried.

To best interpret these dog remains and the other materials at Ust’-Polui, a reliable chronology for the site’s occupation is needed. The early phase of reporting on Ust’-Polui was prior to the widespread use of radiocarbon (14C) dating in Siberia, and assessment of its chronology at that time was based on artifact cross-dating. Specifically, Moszyńska (Reference Moszyńska1974:321–4) noted similarities in some of the bronze and antler items at Ust’-Polui with those from the Ananino culture in the Kama River basin of northeastern Europe, and based on this suggested Ust’-Polui dated between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC. Prior to the present study, the only other published chronological data for Ust’-Polui consisted of four dendrochronology assessments, which ranged in age from 76 to 49 BC, and a 14C date on one of these wood samples of 2070 ± 30 BP (B-7063) (Khantemirov and Shiatov Reference Khantemirov and Shiiatov2012).

Given our initial interests, a way forward is to directly date the dog remains recovered from the site. However, one challenge in studying the chronologies of ancient dogs and other omnivores, including humans, is that such organisms can acquire carbon from various sources, including environments with significant old-carbon reservoirs. While marine reservoir effects have been widely studied in archaeology for decades (Gillespie and Temple Reference Gillespie and Temple1977), freshwater reservoir effects (FREs) have only recently become broadly acknowledged in the field, particularly in Siberia. For example, several recent papers have clearly documented FREs in this region of Russia, particularly at and near Lake Baikal and in southwest Siberia (Nomokonova et al. Reference Nomokonova, Losey, Goriunova and Weber2013; Marchenko et al. Reference Marchenko, Orlova, Panov, Zubova, Molodin, Pozdnyakova, Grishin and Uslamin2015; Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Schulting, Goriunova, Bazaliiskii and Weber2014; Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Bronk Ramsey, Bazaliiskii, Goriunova and Weber2014, Reference Schulting, Bronk Ramsey, Bazaliiskii and Weber2015; Svyatko et al. Reference Svyatko, Mertz and Reimer2015). Ideally, the presence of old carbon biases is demonstrated through paired 14C dates, one on the organism that fed in the potential old carbon environment, the other on the remains of an associated organism that acquired its carbon outside of such food chains. Such dates can then be paired with stable carbon and nitrogen isotope data, which helps in reconstructing past food webs, and in understanding the extent to which the dated organisms were incorporating old carbon from 14C depleted environments such as freshwater rivers or lakes.

This paper presents new 14C dates for wood charcoal, faunal remains, and human bone from Ust’-Polui, including a few sets of paired dates. Stable isotope data are also presented for this site in an effort to reconstruct dietary patterns, including those of dogs and people. Together, these data allow the chronology of Ust’-Polui to be clarified, human dietary patterns and dog provisioning practices to be better understood, and a major FRE to be clearly documented for the first time in Arctic Siberia.

SETTING AND BACKGROUND

Ust’-Polui is located in the city of Salekhard, Russian Federation, and on the edge of a peninsula that forms the northeast bank of the Polui River near its junction with the Ob River (Figure 1). Today the site is in a zone of forested tundra, with open tundra being present within a few kilometers. The Ob River, which has its upper tributaries in central Asia and the Altai Mountains of Russia, is nearly 5km wide and highly braided where it joins the Polui River. The Ob in this region is flanked by broad floodplains with extensive wetlands. About 150 km downstream of Ust’-Polui, this river joins the Gulf of Ob. This body of water separates the Yamal and Gydan peninsulas and is an extension of the Kara Sea. The foothills of the Polar Ural Mountains are about 60 km to the west.

While portions of the site were destroyed by modern construction, several hundred square meters of intact deposits at Ust’-Polui have been excavated. The site is considered by all investigators to have a single major Iron Age component, and a very minor and short-lived medieval occupation (Gusev and Fedorova Reference Gusev and Fedorova2012). Gusev and Fedorova (Reference Gusev and Fedorova2012), who excavated the site over the last several decades, refer to Ust’-Polui as a sanctuary (“sviatilishche”) or sacrifice site that was it mostly used for sacred practices by various regional forager groups. Their interpretation is based on several sets of evidence. First, at least the northern and eastern margins of the site were enclosed by a moat and wood fence. A wooden foot bridge, oriented due north, spanned the moat about 10 m from its northern end. The presence of this bridge, and the shallow and narrow nature of the trench (1.2–1.6 m deep by 1.3–1.6 m wide) are thought to have rendered this feature unsuitable for use as a fortification, perhaps indicating its use as a symbolic barrier. Second, a large number of ornamental objects have been found at Ust’-Polui, including several human figurines and other anthropomorphic depictions, some of which are very similar to historical idols from the region. Third, several sets of human remains were present, including burials and isolated skeletal elements. Human remains appear to be rare at most regional habitation sites. Fourth, the unusual abundance of dog remains at the site, particularly the concentration of crania mentioned previously, has been interpreted as evidence of dog sacrifices. Fifth, artifacts at the site were often found in loose concentrations, sometimes in oval or round patches, and occasionally around large stones or on prepared surfaces. These concentrations are thought to be remnants of prepared sacrificial offerings. Earlier researchers too argued that many ritual activities occurred at Ust’-Polui, but also suggested the location, or portions of it, functioned at times as a fortified habitation site (Moszyńska Reference Moszyńska1974; Gusev and Fedorova Reference Gusev and Fedorova2012).

Faunal remains from Ust’-Polui have been most recently summarized by Bachura et al. (Reference Bachura2016). Despite the inconsistent use of sieves during excavation, fish remains were still most numerically abundant in the site’s overall faunal assemblage, accounting for ~48% of the identified specimens. Burbot (Lota lota) make up just over 62% of the identified fish remains, with inconnu (Stenodus nelma) and whitefish (Coregonus spp.) being the only other fish to make up 10% or more of the identified specimens. All of these fish are freshwater or anadromous species that at least seasonally inhabit the Ob and is lower tributaries. Mammal remains account for 28% of the identified remains with ~63% of these being from reindeer, and ~21% from dogs. All other mammals are represented by far smaller quantities of specimens, with only hare (Lepus timidus), beaver (Castor fiber), and arctic fox (Lagopus lagopus) remains each accounting for more than one percent of the identified mammals. Finally, bird remains constitute about 24% of the identified faunal specimens, with ~59% of the identified specimens being from ptarmigan (mostly Lagopus lagopus). Waterfowl constituted ~28% of the identified specimens, with the other avian remains mostly being from birds of prey.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Radiocarbon dates on 42 wood charcoal samples are available for this study (Table 1). One sample (B-7063) was dated by acclerator mass spectrometry (AMS) at the University of Bern Laboratory for the Analysis of Radiocarbon. All other dates on charcoal were generated through the conventional radiometric technique. These include six dates obtained through the Institute of the History of Material Culture, Russian Academy of Science (samples with LE prefix), and 35 dates from the Institute of Geology and Mineralogy, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (prefix SOAN). In addition, 22 AMS 14C dates were obtained through the Tandem Laboratory, University of Uppsala (prefix Ua), including 20 dates on human and faunal bones, along with one date each on birch bark and leather (Table 2).

Table 1 Radiocarbon determinations on wood charcoal from Ust’-Polui.

Table 2 Non-charcoal radiocarbon determinations from Ust’-Polui. Stable isotope values are those obtained during radiocarbon dating, where available.

The only well-preserved human skeleton at Ust’-Polui, represented by date Ua52103, was found 30–40 cm below the modern soil surface. It was about one meter outside the moat and 13 m southeast of the wood foot bridge. Based on this contextual information, the skeleton was considered to be of similar age to the main site component. The skeleton belonged to a 35–40-yr-old female and was found in a flexed position on its left side. Among the skeletal remains were bits of hide, likely parts of clothing worn by the deceased. A sample of this hide material was also dated (Ua54157). Fragments of birch (Betula sp.) bark were found under the skeleton, and remnants of fir (Abies sp.) branches were found resting on its upper surface.

A second burial at Ust’-Polui was found within the main site area and 110–130 cm below the modern surface, well below the site’s other archaeological deposits. Based on its position, the burial was believed to predate Ust’-Polui’s main component. This adult skeleton was poorly preserved, and it was tightly flexed and resting on its left side. The body was interred within a rectangular-shaped grave pit possibly supported by a wooden frame; a layer of birch bark was found directly under the skeleton, and fir twigs were found resting on its upper surface. The bark and twigs likely formed a container for the body. The skeleton was directly dated (Ua52102), as was a sample of the birch bark found directly below it (Ua54158).

The final human bone dated in this study (Ua52101) was an isolated adult tibia from the main site area found among artifacts and faunal remains. Note that other isolated human remains were found in the main site area in the 1930s and 1990s (Fedorova and Gusev Reference Fedorova and Gusev2008). These remains could be from earlier graves that were disturbed during the main period of site use. Alternatively, they could have been transported to Ust’-Polui as disarticulated skeletal elements and then deposited at the site as part of secondary mortuary rituals.

The final two sets of paired dates from the site, Ua-54159/54160 and 54161/54162, consist of reindeer bone and fish bone samples. In both cases the reindeer bones and fish bones were found directly next to each other within 3–5 cm thick sediment layers (designated by the excavators as “horizons”).

All dates were calibrated and modeled in Oxcal 4.2.4 using the IntCal-13 dataset (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2014; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). Site stratigraphy and artifact typology indicate that all objects dated here, perhaps with the exception of the human remains and their associated items, come from a single period or phase of site occupation. Sets of dates are thus analyzed as single phases using the default settings in the Oxcal phase model. In these models, age range estimates are given for the start and end of the phase at the 95.4% confidence interval in years cal BP [highest posterior distribution (HPD) intervals]. Means and standard deviations for the starts and end intervals of phases, generated by OxCal, are also provided, also at the 95.4% confidence level. Age offset uncertainties for paired dates are the sums of the squares of the uncertainties of the two dates being compared (following Svyatko et al. Reference Svyatko, Mertz and Reimer2015). Provenience information for all samples was translated directly from Russian-language reports. The amount of contextual information available for the dated samples varies widely depending upon the year of excavation.

A total of 45 archaeological bone fragments yielded collagen suitable for stable isotope analysis, including two samples from humans, 32 from dogs, and 11 from nine from other fauna taxa represented in the site assemblage (Table 3). Stable isotope analysis was conducted at the University of Alberta Department of Anthropology archaeological laboratory using a modified version of the Oxford sample preparation method (Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Higham, Bowles and Hedges2004). All samples were cleaned, and ~1 mm of outer bone surfaces were removed. Samples were then sonicated for 10min in three changes of double-distilled water, and air dried. The samples were ground to powder consistency in a Spex Certiprep liquid nitrogen mill. Approximately 500 mg of powder from each sample was placed in a polyethylene vial with 12 mL of 1% hydrochloric acid (HCl) and allowed to demineralize. After demineralization, samples were centrifuged and rinsed in double-distilled water until they reached neutrality as determined by pH testing strips. Upon reaching neutrality, the samples were drained of water. Twelve mL of .01M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution was then added to remove humates. Vials were shaken and allowed to react at room temperature for 20 hr. Samples were then centrifuged and rinsed in changes of double-distilled water until they reached neutrality, and were drained of water. Immediately following this step, another 12 mL of 1% HCl was added to sample vials. Vials were shaken and left to react for 2 hr at room temperature. Samples were then centrifuged and rinsed with double-distilled water until neutrality and then drained.

Table 3 All δ13C and δ15N values for Ust’-Polui obtained in this study through the University of Alberta laboratory.

Six mL of acidulated water with a pH of 3 were added to each vial and shaken. The samples were then placed in a 75°C water bath and left to allow the collagen to gelatinize into solution for 20 hr. The supranatant from each sample was filtered through a glass fiber filter paper using a Nalgene 40 mm Büchner filter and a 125 mL sidearm/filtering flask. Approximately 6 mL of filtrate from each sample was poured into a dual-chambered Vivaspin® 30 µL ultrafiltration vial and centrifuged until 1 mL remained in the upper chamber. This amount was pipetted into a pre-weighed centrifuge vial, frozen, lyophilized and then analyzed at the University of Alberta’s Biogeochemical Analytical Services Laboratory (BASL). Samples were analyzed for δ15N and δ13C ratios using a EuroVector EuroEA3028-HT elemental analyzer coupled to a GV Instruments IsoPrime continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer. δ13C and δ15N ratios (‰) were determined using the following equation:

where Rsample is the ratio of 15N/14N or 13C/12C in the sample, and Rstandard refers to the international standards Vienna Pee Dee Belemite (VPDB) and AIR, respectively. BASL used NIST 8415 whole egg powder SRM as a δ13C and δ15N QA/QC check throughout analyses. Measurement accuracy for the δ13C and δ15N was ±0.1‰ and ±0.2‰, respectively. Assessment of collagen sample validity involved the following quality indicators: (1) percent collagen yield above 1% by weight; (2) percent carbon and nitrogen by weight above ~26% for carbon and 11% for nitrogen; and (3) atomic C/N ratio values between 3.1 and 3.6 (DeNiro Reference DeNiro1985; DeNiro and Weiner Reference DeNiro and Weiner1988; Ambrose Reference Ambrose1990; van Klinken Reference Van Klinken1999).

RESULTS

Charcoal Dates

Charcoal dates SOAH-9424 and 9428 were excluded prior to modeling, as both are from sediments under the archaeological deposits at the site. The remaining 40 dates are from the primary Iron Age component and were entered into a single phase model in Oxcal. In the first run of the model, samples SOAH-9317 and 9536, the youngest and oldest dates, respectively, were marked as in poor agreement. With these dates included, the mean start and end dates for the phase were 354 BC and 352 AD (Table 3). In the next run of the model, SOAH-9317 and 9536 were removed, which then resulted in SOAN-9318 being identified as in poor agreement. This date was then removed and the model was run a third time. In this final model, none of the 37 dates were in poor agreement, and the mean modeled starting and ending dates were 260 BC and 139 AD, respectively (Table 4; Figure 2).

Figure 2 Results of Bayesian modelling of radiocarbon determinations with phase boundaries marked for each subset of dated materials.

Table 4 Phase model age ranges for subsets of radiocarbon ages from Ust’-Polui.

Importantly, many of the charcoal dates have relatively large margins of error, some just over a century. The imprecision of these dates helps create the relatively wide starting and ending age ranges in the phase models. Further, all but one of the charcoal dates were obtained through standard radiometric dating, which requires comparatively large samples, meaning individual dates nearly always reflect the ages of multiple sets of tree rings rather than the death of individual trees. In other words, the bulk or mixed nature of these samples also may render some of the dates inaccurate. Some old carbon effects (in-built age effects) also potentially influence these dates, including the burning of old wood, and the presence of naturally occurring charcoal in the site sediments. Both would produce 14C ages somewhat older than the events of interest and potentially lengthen the estimate age of the phase. Overall, we suspect the combination of these possible biases in the charcoal dates perhaps makes the age range estimates for Ust’-Polui slightly too old, but the extent of this bias is unclear. Note that the three previously published dendrochronology dates for Ust’-Polui ranged from 76 to 49 BC (Khantemirov and Shiatov Reference Khantemirov and Shiiatov2012), well within the modeled time range of the 37 charcoal 14C dates.

Reindeer and Dog Bone Dates

The 14C dates on all other material at the site, including bone and antler, were obtained through the AMS dating method, and all have margins of error around 30 or fewer years—they are far more precise than nearly all of the charcoal dates. These dates also each represent shorter periods of time, such as the last few years prior to the death of an animal, which means they are potentially more accurate than the dates on bulk charcoal samples just presented. In analyzing the reindeer and dog dates, models were created for each species individually, as their very different diets potentially means their bone carbon was acquired from very different environments.

The seven 14C dates on reindeer bone were modeled as a single phase in Oxcal, as all samples come from the site’s primary component. This produced a modeled mean start age of 111 BC and a mean end age of 352 AD (Table 4; Figure 2). While this model was built on a far smaller set of samples than the charcoal phase models just described, the age range estimates of the phase model still overlap those generated by the charcoal dates. For example, the mean start age for the reindeer dates is only about one century later, and the end mean about two centuries later than those of the charcoal model with the poor agreement samples removed. Given the overlap in the reindeer bone and charcoal models, and the lack of evidence for an age bias in the reindeer dates, all charcoal and reindeer bone dates (n = 47) were entered into a single phase model. In the first run of the model, SOAH-9317 and 9536 were identified as being in poor agreement with the other dates, just as in the charcoal model. With all dates included, the mean of the start age was 318 BC±60, and the mean of the end date of 339 AD±67 (Table 4). Excluding SOAH 9317 and 9536, the model then identified SOAH-9318 as being in poor agreement, just as in the charcoal model second run. Removing all three poor agreement dates, the start and end date means were 262 BC±61 and 231 AD±47, respectively (Table 4; Figure 2). Subsequent runs of the model with poor agreement dates removed recurrently identified additional dates as being in poor agreement, and progressively narrowed the estimate of the phase duration. Taking a conservative approach, we have excluded these age models.

The seven dates on dog bones were also modeled as a single phase. These includes dates on dog remains recovered in the 1930s and those from more recent excavations at Ust’-Polui, and all were assigned to the site’s primary component. When modeled, the dog bone dates showed no overlap with the reindeer or charcoal phase models (Table 4; Figure 2). The mean modeled start date of the phase is 1129 BC, which is 775 yr prior to the youngest mean starting date for the other five models. The modeled end date for the dog dates is 679 BC, or 818 yr before the oldest end date in the other models. In other words, the dog dates at face value are far older than the other dated materials from Ust’-Polui, despite all contextual information indicating they should be of similar age.

Human and Paired Dates

Given that only three 14C dates are available for human remains, and that one of the two graves is thought to predate the primary occupation component, a phase model is inappropriate. When the human dates were calibrated, all clearly predate the reindeer and charcoal modeled age ranges, just as was seen with the dog bone dates (Table 2). Date Ua52103, from the grave thought to be most closely associated with the site’s main occupation, is at face value the youngest of the three dated human skeletons, with a calibrated age range of 793 to 540 BC. Its age is within the modeled age range of the dog remains at the site. The other two human dates are similar in age to each other and just predate the site’s dog remains.

The paired dates most clearly indicate that the dog, human, and fish bone samples have an old carbon bias that renders them centuries too old. Paired dates are available for both human burials at the site, and for two sets of stratigraphically associated fish bone and reindeer bone samples (Table 2). A single date (Ua54163) on an isolated fish bone is available for comparative purposes. These dates show a fairly clear pattern (Table 5). First, the age offsets in the paired samples range from 568 ± 43 to 1021 ±43 yr, with an average offset of 784.25 yr. Second, the three fish bone dates are similar in age to the site’s dated dog remains, and the two paired fish bone samples have age offsets of 582 ± 40 and 966±39 yr. Third, the human bone dates are far older than their associated paired dates. Specifically, the site’s youngest human bone date (Ua52103) is 568 yr older than the leather material (date Ua54157) found with it, while the date on the deeply buried skeleton (Ua52102) is 1021 yr older than the birch bark it was lying directly on. Notably, the youngest human burial here and its paired date should be cautiously evaluated. The δ13C value of the leather is –13.7 (Table 2), which is far higher than all terrestrial mammals at the site, suggesting that it may be from a marine mammal, which could have some marine reservoir offset (discussed below). Further, this human has far higher δ13C values than the other dated human and dog remains at Ust’-Polui, indicating that its dietary protein differed from that consumed by the other dated organisms. Overall, the leather date (Ua54157) falls within the modeled age range of the reindeer bone and charcoal dates from Ust’-Polui, while the birch bark date (Ua54158) predates the reindeer bone age range by just over a century, but falls within the modeled age range of the charcoal dates.

Table 5 Age offsets observed in paired radiocarbon age determinations for Ust’-Polui.

The final indication of a patterned age bias in some of the bone dates is the δ13C values obtained during 14C dating. When all bone 14C ages are plotted against their δ13C values, two data point clusters are evident (Figure 3). The first cluster, with δ13C values between –20.0 and –18.4‰ (mean = –19.0‰), and 14C ages from 2052 to 1732 BP, is formed by the site’s seven reindeer bone dates. The second cluster has far lower δ13C values, between –26.9 to –24.7‰ (mean=–26.1‰), and older 14C ages, spanning from 3234 to 2515 BP. This cluster consists of all of the dog and fish bone dates, and two of the human dates. The final human sample, Ua52103, falls midway between the two clusters. In other words, bones with lower δ13C values produce dates inconsistent with those on charcoal and the dendrochronology dates, while those with higher δ13C values tend to be far more consistent with these other datasets. The fact that lower δ13C values are seen in the human and dog samples (both omnivores) as well as in the fish samples, while higher values are only found in the herbivorous reindeer bones, suggests that aquatic environments and regular consumption of aquatic foods is causing the observed age differences in the Ust’-Polui datasets.

Figure 3 Biplot of δ13C values obtained during radiocarbon dating and uncalibrated radiocarbon age midpoints for bones dated from Ust’-Polui.

Stable Isotopes

A biplot of δ13C and δ15N values obtained at the University of Alberta shows that the humans and dogs exhibit the highest δ15N values of all analyzed samples, with means of 17.2‰ and 13.9‰, respectively (Table 3; Figure 4). The two humans have a mean δ13C value of –26.2‰, and the dogs a mean value of –25.8‰, which are the lowest δ13C values in the study. The dominant terrestrial herbivores at Ust’-Polui, reindeer, have a mean δ15N value of 6.2‰ and mean δ13C value of –19.4‰. Waterfowl were relatively abundant in the site’s faunal assemblage and these are represented by a single duck (Anas sp.) specimen, which has isotope values most similar to two small carnivores, the sable (Martes zibellina) and the arctic fox. All three have far higher δ13C values than those of the dogs and humans. Ptarmigan were also relatively abundant at the site, and the one analyzed specimen has a very low δ15N value of 1.5‰, and a δ13C value of –21.1‰. Similar values have been found for modern Arctic ptarmigan flesh in other studies (Feige et al. 2002; Ehrich et al. Reference Ehrich, Ims, Yoccoz, Lecomte, Killengreen, Fuglei, Rodnikova, Ebbinge, Menyushina, Nolet, Pokrovsky, Popov, Schmidt, Sokolov, Sokolova and Sokolov2015). The values for two Ust’-Polui marine mammal samples, from walrus (Odenobus rosmarinus; δ13C = –17.3‰, δ15N = 12.5‰) and seal (Phoca sp.; δ13C = –18.8‰, δ15N = 4.8‰), both have far higher δ13C values than any of the above fauna. This is consistent with expectations based on other studies, which report arctic pinniped flesh δ13C values no lower than about –22‰ (Hoekstra et al. Reference Hoekstra, Dehn, George, Solomon, Muir and O’Hara2002, Reference Hoekstra, O’Hara, Fisk, Borga, Solomon and Muir2003; Muir et al. Reference Muir, Savinova, Savinov, Alexeeva, Potelov and Svetochev2003; Dehn et al. Reference Dehn, Sheffield, Follmann, Duffy, Thomas and O’Hara2006; Matley et al. Reference Matley, Fisk and Dick2015; Jaouen et al. Reference Jaouen, Szpak and Richards2016). Note that the seal δ15N value is unusually low compared to modern arctic pinnipeds, which typically have δ15N values (for flesh samples) greater than 10.0‰ (see Hoekstra et al. Reference Hoekstra, Dehn, George, Solomon, Muir and O’Hara2002, Reference Hoekstra, O’Hara, Fisk, Borga, Solomon and Muir2003; Muir et al. Reference Muir, Savinova, Savinov, Alexeeva, Potelov and Svetochev2003; Dehn et al. Reference Dehn, Sheffield, Follmann, Duffy, Thomas and O’Hara2006; Matley et al. Reference Matley, Fisk and Dick2015; Jaouen et al. Reference Jaouen, Szpak and Richards2016). It is possible that the specimen was misidentified prior to sampling. If the humans and dogs at Ust’-Polui were heavily reliant on any of the above terrestrial or marine fauna, we would expect their δ13C values to fall somewhat above those of these fauna, which they do not.

Figure 4 Biplot of δ13C and δ15N values for bone collagen from Ust’-Polui, all obtained through the University of Alberta laboratory.

While freshwater fish bones were very abundant at Ust’-Polui, our efforts to generate reliable fish bone collagen stable isotope values were unsuccessful. Note, however, that δ13C and δ15N values were obtained for two Ust’-Polui inconnu and one burbot sample during 14C dating (Table 2). As these values were attained through different methods than those used to generate the dog and human data described above, they cannot be directly compared to the University of Alberta laboratory values. Nonetheless, the δ13C values for these specimens are quite low, ranging between –26.7‰ and –24.7‰, and their δ15N values are between 11.2‰ and 13.6‰. This is consistent with the results of research on modern freshwater river and lake fish from the Arctic. Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope values in freshwater systems are complex and vary widely, reflecting factors including the productivity of the body of water and contributions of terrestrial organic matter to its food web as well as the microhabitat and feeding niche of the organism in question (e.g. Hecky and Hesslein Reference Hecky and Hesslein1995; Chetelat et al. Reference Chételat, Cloutier and Amyot2010; Premke et al. Reference Premke, Karlsson, Steger, Gudasz, von Wachenfeldt and Tranvik2010; for reviews and applications in archaeology see Katzenberg and Weber Reference Katzenberg and Weber1999; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Capriles and Hastorf2010; Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Müldner, Van Neer, Ervynck and Richards2012). Studies of Arctic freshwater river and lake fish typically report very low δ13C values for these organisms ranging from about –30‰ to –20‰ (Hesslein et al. Reference Hesslein, Capel, Fox and Halfard1991; Hecky and Hesslein Reference Hecky and Hesslein1995; Feige et al. Reference Feige, Ehrich, Popov and Broekhuizen2012).

The human and dogs at Ust’-Polui have δ13C values well within the range of such freshwater fish. Further, the comparatively high δ15N values of the humans and dogs are also consistent with regular consumption of fish.

Overall, the stable isotope data, and the dominance of freshwater fish within the site’s faunal assemblage, strongly suggest both people and dogs at Ust’-Polui were consuming significant amounts of freshwater fish. Given that dogs cannot effectively fish for themselves, particularly in the far North where surface water is frozen for much of the year, these data also indicate human provisioning of dogs with fish. Note that the single analyzed wolf (Canis lupus) specimen has a markedly different dietary signature from the Ust’-Polui dogs, with a δ13C value of –19.3‰ and a δ15N value of 11.6‰. Unlike the dogs, it was clearly consuming very little aquatic fauna in its diet.

DISCUSSION

Marine reservoir effects are unlikely to account for the old carbon offsets observed in our data. First, marine environments are considerable distances from Ust’-Polui. The southern half of the Gulf of Ob is heavily dominated by the outflow of the Ob River, meaning that freshwater environments continue to be found for several hundred kilometers to the northeast within this body of water (Diansky et al. Reference Diansky, Fomin, Kabatchenko, Litvinenko and Gusev2015). The nearest high salinity marine environments to Ust’-Polui are at Baydaratskaya Bay on the west side of the Yamal peninsula, about 200 km directly overland to the north; this bay is an extension of the Kara Sea. Second, the local proposed marine reservoir effect in this region is too small to account for the age offsets observed in our study. Marine reservoir values for known-age bivalves from the eastern shore of Novaya Zemlya far to the northwest on the Kara Sea range from 330 to 764 yr (Forman and Polyak Reference Forman and Polyak1997). However, the highest such values are from dates on a single species (Portlandia arctica) that inhabits low salinity waters. Forman and Polyak (Reference Forman and Polyak1997) postulated that the high offset values result from these bivalves incorporating old carbon from glaciers or streams on Novaya Zemlya (a freshwater reservoir effect), or from the substrate they inhabit. The authors further argue that dates (n = 9) on other shellfish species from the Kara and Barents seas are more representative of the regional open marine reservoir effect in this region, and these have an average offset value of 277±78 yr (Forman and Polyak Reference Forman and Polyak1997). This is far less than the average age offset observed in our paired 14C dates.

Far more parsimonious with the location of Ust’-Polui on the landscape, its stable isotope and faunal data, and the 14C age offsets observed in this study is a freshwater source for the old carbon effects. As described above, the low δ13C values of the dog and human remains provide no indication of reliance on marine foods, perhaps with the exception of the youngest human burial at the site (represented by date Ua52103), which has a higher δ13C value than the other dated dogs and humans at the site. Overall, the dog and human stable isotope values at Ust’-Polui are most consistent with diets of a mixture of terrestrial mammals and freshwater organisms, the latter most likely local fish. As mentioned, fish remains were numerically dominant at the site, and burbot, whitefish, and inconnu were most abundant among the identified specimens. Conversely, birds remains were third in relative abundance following fish and mammals, and waterfowl account for less than one-third of the site’s identified bird remains, being far outnumbered by remains of ptarmigan, which inhabit the forest and tundra. Further, access to waterfowl was probably more seasonally restricted than access to fish or mammals (from late spring through early fall), as these birds are largely dependent on the presence of open water (Vizgalov et al. Reference Vizgalov, Kardash, Kosintsev and Lobanova2013). Fishing in the Ob was probably most effective in the warmer part of the year but could have occurred nearly year-round. Rivers in this region, except those flowing from the Ural Mountains to the west, experience a period of low oxygen and high organic input beginning around January (±1.5 months) and lasting until the breakup of the ice in May or June (Dunin-Gorkavich Reference Dunin-Gorkavich1995). In anticipation of this phenomenon in the fall, most fish, including burbot and whitefish, move out of the rivers and into the Gulf of Ob, or into locations such as the mouths of rivers originating in the Urals (Vizgalov et al. Reference Vizgalov, Kardash, Kosintsev and Lobanova2013). Runs of anadromous fish such as inconnu also occur in the lower Ob only in summer (Vizgalov et al. Reference Vizgalov, Kardash, Kosintsev and Lobanova2013). Some winter fishing in the Ob and its tributaries is also possible, particularly at the river mouths and in other areas that remained well oxygenated.

Provisioning dogs with fish is in some ways expected. Previous stable isotope work on Middle Holocene archaeological dog remains from the Cis-Baikal region of Siberia indicates that most dogs had diets consisting of significant quantities of aquatic foods (Losey et al. Reference Losey, Bazaliiskii, Garvie-Lok, Germonpré, Leonard, Allen, Katzenberg and Sablin2011, Reference Losey, Garvie-Lok, Leonard, Katzenberg, Germonpre, Nomokonova, Sablin, Goriunova, Berdnikova and Savel’ev2013), particularly along the western shore of Lake Baikal, and on the lake’s outlet river, the Angara; both regions are rich freshwater fisheries. Ethnographic sources commonly report that dogs were regularly provisioned with fish bones and flesh in Northwest Siberia, particularly in areas where fishing was common (Khomich Reference Khomich1966; Lukina and Ryndina Reference Lukina and Ryndina1987; Perevalova Reference Perevalova2004; Aksenova et al. Reference Aksenova, Baulo, Perevalova, Ruttkan-Miklian, Sokolova, Soldatova, Taligina, Tyshkova and Fedorova2005; Gemuev et al. Reference Gemuev, Molodin and Sokolova2005; Elert Reference Elert2006; Lukina Reference Lukina2010). Dog predation on or scavenging of fish outside of human settlements was probably rare in the Arctic, except in tidal areas in summer, and isotope data showing that dogs consumed significant amounts of aquatic protein are likely a good indication that humans intentionally provisioned dogs mostly with fish. Dogs of course can feed themselves by preying on terrestrial mammals, and in this regard the isotope data are more ambiguous. Any terrestrial component in their diets could be interpreted as dog self-provisioning, human provisioning, scavenging, or potentially all three in various combinations. Finally, the general similarity in dietary structure between humans and dogs at Ust’-Polui is also not surprising, as similar patterns have been observed in stable isotope studies in many locations (Guiry Reference Guiry2012, Reference Guiry2013; Losey et al. Reference Losey, Garvie-Lok, Leonard, Katzenberg, Germonpre, Nomokonova, Sablin, Goriunova, Berdnikova and Savel’ev2013), and the abundance of fish remains at Ust’-Polui indicate some human reliance on these animals as food sources.

Several sources of old carbon in the Ob River watershed potentially contributed to the offsets observed in our human, dog, and fish samples. First, limestone, a major source of fossil carbon in some freshwater systems (Philippsen Reference Philippsen2013), is present within the watershed (Larin Reference Larin2004; Vyssotski et al. Reference Vyssotski, Vyssotski and Nezhdanov2006). Second, extensive areas of the river basin are peatlands, many of which began forming early in the Holocene (Kremenetski et al. Reference Kremenetski, Velichko, Borisova, MacDonald, Smith, Frey and Orlova2003), and dissolved old carbon from them could have entered the aquatic food chain. Third, permafrost is widespread in the Ob basin, and melting of these sediments could have been another source of old carbon. Finally, small (<1 km in area) cirque glaciers are present in the Polar Ural Mountains (Svendsen et al. Reference Svendsen, Krüger, Mangerud, Astakhov, Paus, Nazarov and Murray2014), and their meltwater also could have contributed some 14C depleted carbon to the northern portion of the Ob watershed. While variable combinations of all four of these sources likely shaped the FREs carried by the fish that were consumed at Ust’-Polui, the factors influencing waterfowl were probably more complex, as their seasonal migrations exposed them to a wider array of carbon sources, including those beyond western Siberia.

Returning to the chronology of Ust’-Polui, several key points can be made. First, given the old carbon offsets in the dated human, dog, and fish bones, we propose that the charcoal or charcoal/reindeer bone phase models (with poor agreement samples removed) provide the most reasonable estimates for the primary occupation of Ust’-Polui. Using the means of the modeled start and end ranges suggests the primary component spanned from ~260 BC to 140 AD, or to as late as 230 AD (Table 4). These dates encompass the dendrochrology dates available for the Ust’-Polui (Khantemirov and Shiatov Reference Khantemirov and Shiiatov2012), and just post-date the earlier typological age estimate for this site (Moszyńska Reference Moszyńska1974). Second, the earliest human burial at the site, represented by date Ua54158 (birch bark from the grave), appears to have been created just prior to formation of the primary component, or very early in its history. The other burial, represented by date Ua54157 (leather from the grave), was contemporaneous with the primary component, as was assumed based on its context. Third, it is difficult to precisely estimate the age offsets in the dog remains and the isolated human bone dated in this study. While these samples have no paired dates for calculation of such offsets, all were found within site’s primary deposits. The dog dates have a modeled start period mean of 1129 BC (Table 4), which predates our accepted start mean of 260 BC by 869 yr. Further, the earliest modeled mean start date in this study, based on all available charcoal dates (poor agreement samples included), is 354 BC, or 775 yr later than the dog dates start mean. These age differences are roughly similar to the average age offset value for our four paired samples, which is 784 yr. Removing the pair of dates from the youngest human burial at the site, where the human may have consumed at least some marine foods and thus carries an age offset from different or mixed carbon reservoirs, the average offset in the remaining three paired samples increases to 856 yr.

CONCLUSION

This study is the first to demonstrate a major freshwater reservoir effect in the lower Ob River region of Arctic Siberia. The resulting age bias in 14C dates from this region will depend on many factors, including organisms’ overall reliance on aquatic foods, and the particular offset values of the specific aquatic foods that are eaten by those organisms over time. The two sets of dated human remains with paired dates in this study have age offsets of 568 and 1021 yr, and the suggested age bias in the site’s dog remains is at least 775 yr. Such large age offsets are potentially very misleading in terms of understanding site chronologies and developing broader culture histories. This points to the need for stable isotope data on all dated bone samples, and the necessity of dating more than one material type from any given context. To develop methods for more precisely estimating FRE offsets in the region’s 14C-dated samples, additional paired samples with stable carbon and nitrogen isotope data are needed. Better understanding of the region’s stable isotope ecology is also required, particularly for local fish and waterfowl.

The partial dietary reliance on aquatic foods by both the people and dogs at Ust’-Polui matches well the zooarchaeological data from this site, which indicates that fish remains were highly abundant. Provisioning of dogs with fish is widely reported in the region’s ethnographic literature, and the data presented here indicate that such animal management practices have a deep history along the lower Ob River. The extent of human reliance on fish and other aquatic foods beyond Ust’-Polui in Arctic Siberia remains poorly documented, but could be assessed in future stable isotope studies. Study of paleodiet in this region will of course be informative about diachronic and ecological patterning in subsistence practices, but also may reveal other old carbon reservoir effects that are presently causing unrecognized biases in archaeological 14C dates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this project was provided by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada grant (#SSHRC IG 435-2014-0075) and by a grant from the European Research Council to D Anderson (#295458). M Sablin’s participation in the project involved the participation of ZIN RAS (state topic N 01201351185). Special thanks are offered to Dr Mingsha Ma and Alvin Kwan in the University of Alberta’s Biogeochemical Analytical Services Laboratory. Dr Rick Schulting provided valuable suggestions regarding several aspects of this paper, which are most appreciated. Some of the collections analyzed here are property of the Palaeoecology Laboratory, Institute of Plant and Animal Ecology, Ural Division of the Russian Academy of Science.