INTRODUCTION: SOUTHEASTERN BALTIC BRONZE AGE HILLTOP SETTLEMENTS

Hilltop settlements during the Southeastern Baltic Bronze Age (ca. 1700–500 BCFootnote 1 ) were the first type of enclosed sites that had developed in the region. The pattern of these settlements reflects a changing social-economic environment (Figure 1), however the chronology of their emergence is still poorly known. Hilltop settlements were inhabited by farmers practicing intensive agriculture (Minkevičius et al. Reference Minkevičius, Podėnas, Urbonaitė-Ubė, Ubis and Kisielienė2019), a particular lifestyle that spread amongst the local communities after the lateFootnote 2 adoption of crop cultivation, from 14th–12th centuries cal BCFootnote 3 on (Grikpėdis and Motuzaite Matuzeviciute Reference Grikpėdis and Motuzaite Matuzeviciute2018). Alongside new opportunities for the social development, the economic stress caused by farming and accumulation of surplus has presented the local communities with a range of new threats and barter possibilities. Simultaneously with crop and pulse cultivation spread throughout SE Baltic in the Late Bronze Age (1100–500 BC), the more active foreign agency is tangible in the archaeological record. This is expressed by doubling of bronze consumption, appearance of stone-ship graves, early rusticated pottery, hoards with inherent Scandinavian finds and emergence of bronze production dominated by artifacts with western Baltic stylistic traits (Okulicz Reference Okulicz1976; Sidrys and Luchtanas Reference Sidrys and Luchtanas1999; Sperling Reference Sperling, Johanson and Tõrv2013; Wehlin Reference Wehlin2013; Čivilytė Reference Čivilytė2014). Therefore, it is likely that communication between SE Baltic and neighboring Lusatian and Scandinavian cultures had become significantly more active compared to the previous periods. One of the dangers communities with intensive farming faced was the loss of food stock, therefore a turn to establishment of better defended settlements was inevitable (O’Brien and O’Driscoll Reference O’Brien and O’Driscoll2017). Furthermore, the Southeastern Baltic society lacked maritime technologies to organize their own interregional contacts by long distance travels (cf. Ling et al. Reference Ling, Earle and Kristiansen2018), and all acquired wealth was highly dependent on the ability to establish communication with the ones who imported bronze into the region (Earle et al. Reference Earle, Ling, Uhnér, Stos-Gale and Melheim2015). SE Baltic Bronze Age culturally distinguishes from Lusatian and Scandinavian cultures as well as from the communities settled in the Northeastern Baltic and further to Eastern Europe due to distinctly different economic prehistory (Podėnas and Čivilytė Reference Podėnas and Čivilytė2019). This study takes an integrated approach towards the emergence of hilltop settlements in the region that consists of data from NE Poland, Kaliningrad, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia.

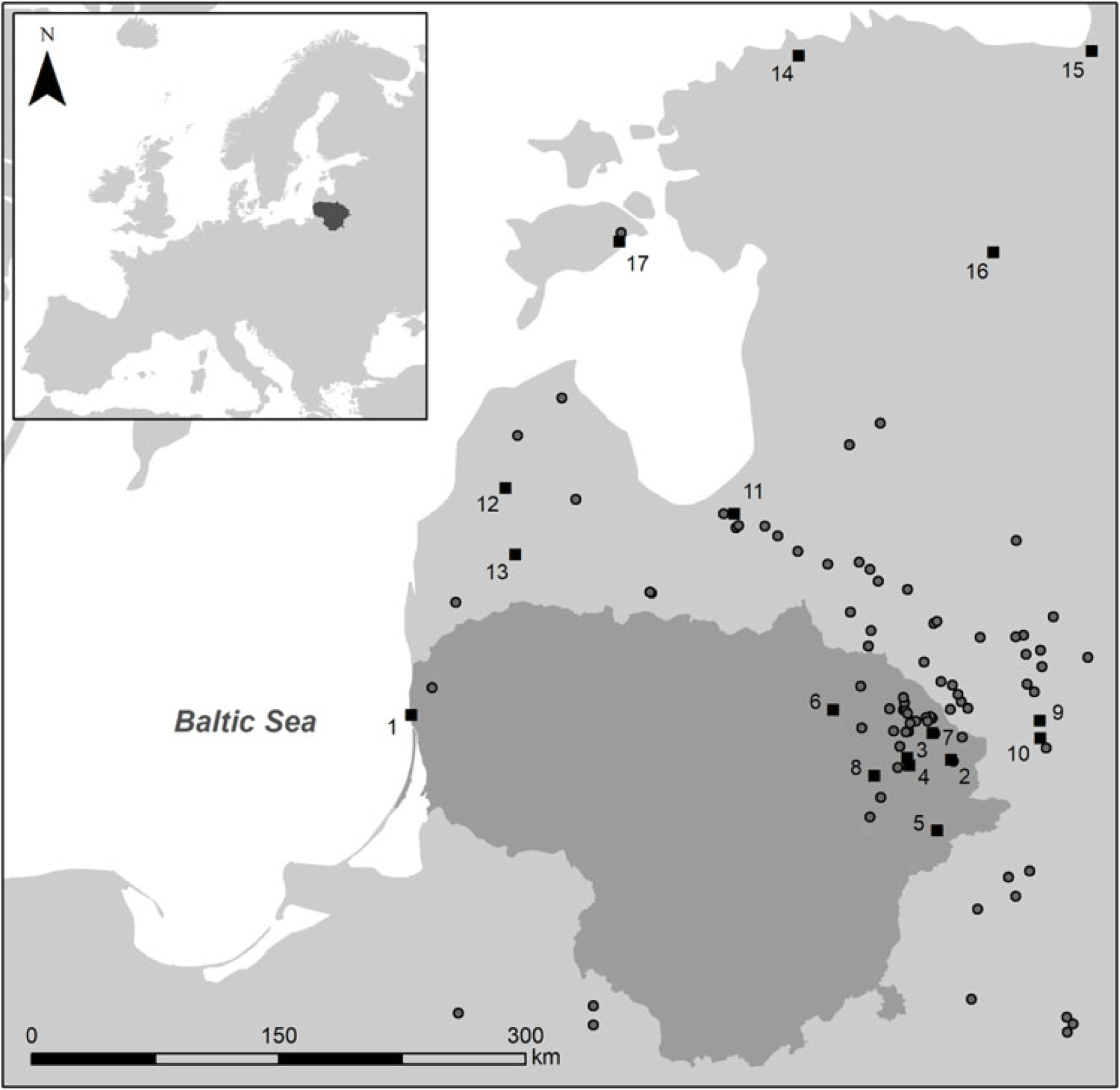

Figure 1 Map of the 14C dated sites in the SE Baltic. Squares: 1 – Kukuliškiai; 2 – Sokiškiai; 3 – Garniai I; 4 – Antilgė; 5 – Nevieriškės; 6 – Kereliai; 7 – Mineikiškės; 8 – Narkūnai; 9 – Zazony; 10 – Ratjunki; 11 – Ķivutkalns; 12 – Padure; 13 – Krievu kalns; 14 – Iru; 15 – Narva; 16 – ; 17 – Asva (see Table 1). Dots – other known hilltop settlements dated to Late Bronze Age by the studies on artifact typologies (data of 105 sites from Graudonis Reference Graudonis1967, Reference Graudonis, Bīrons, Mugurēvičs, Stubavs and Šnore1974, Reference Graudonis1989; Luchtanas Reference Luchtanas1992; Egoreichenko Reference Egoreichenko2006; Lang Reference Lang2007; Valk et al. Reference Valk, Kama, Olli, Rannamäe, Oras and Russow2012 with additions and modifications). Drawing by V. Podėnas. List of all localities is presented in Supplementary Material 1.

Considering the overall scarcity of information on the Bronze Age in the SE Baltic archaeology, the hilltop settlements distinguish as the most actively investigated type of site (Krzywicki Reference Krzywicki1914, Reference Krzywicki1917; Šnore Reference Šnore1936; Volkaitė–Kulikauskienė Reference Volkaitė-Kulikauskienė1986; Graudonis Reference Graudonis1989; Luchtanas Reference Luchtanas1992; Vasks Reference Vasks1994; Grigalavičienė Reference Grigalavičienė1995; Egoreichenko Reference Egoreichenko2006; Lang Reference Lang2007; Vasks et al. Reference Vasks, Kalniņa and Daugnora2011; Valk et al. Reference Valk, Kama, Olli, Rannamäe, Oras and Russow2012; Doniņa et al. Reference Doniņa, Vasks, Vilka, Urtāns and Virse2014; Sperling Reference Sperling2014). These settlements were excavated on numerous occasions from the beginnings of the 20th century and thus received a great deal of interpretation. However, the discussion on chronology is yet to reach a consensus. Due to the lack of distinctive typologies, the existing chronologies tend to vary greatly as the dating of the initial phase of hilltop settling are interpreted differently by different researchers, i.e. ranging from early 2nd millennium BC to early 1st millennium BC (Kulikauskas et al. Reference Kulikauskas, Kulikauskienė and Tautavičius1961; Gimbutienė Reference Gimbutienė1985; Volkaitė–Kulikauskienė Reference Volkaitė-Kulikauskienė1986; Grigalavičienė Reference Grigalavičienė1995; Lang Reference Lang2018). Over the last decades the research focus had shifted towards a 14C dating of the earliest hilltop settlements in attempts to solve this problem (Kriiska and Lavento Reference Kriiska and Lavento2006; Egoreichenko Reference Egoreichenko2006; Lang Reference Lang2007; Valk et al. Reference Valk, Kama, Olli, Rannamäe, Oras and Russow2012; Oinonen et al. Reference Oinonen, Vasks, Zariņa and Lavento2013; Sperling Reference Sperling2014; Vasks and Zariņa Reference Vasks and Zariņa2014; Sperling et al. Reference Sperling, Lang, Paavel, Kimber, Russow and Haak2015). Alongside, new debates emerged on sample selection and a call for application of necessary procedures to assure the link between the sample and the archaeological context (Motuzaite-Matuzeviciute Reference Motuzaite Matuzeviciute2015). Until now, the AMS 14C dates from Lithuania were scarce. Thus, the area of the most densely established hilltop settlements is a white spot on a map when discussing regional chronological development. Hitherto, it was impossible to compare and critically assess the dates from neighboring countries, nor to establish an integrated review of the emergence of hilltop settlement process in Southeastern Baltic.

Regional development models (Earle and Kolb Reference Earle, Kolb, Earle and Kristiansen2010) usually indicate the active contact zones where hilltop settlements emerge. In contrast, the Bronze Age hilltop settlements are unknown in the southern and central Lithuania, and only 1 is found in inland Estonia (Valk et al. Reference Valk, Kama, Olli, Rannamäe, Oras and Russow2012). The preferred environment is a likely culprit for this pattern, for example considering the geomorphological differences between Baltic Uplands and Middle Lithuanian, Middle Gauja, West-Estonian Lowlands (Tavast Reference Tavast and Engelbrecht1994; Zelčs and Markots Reference Zelčs, Markots, Ehlers and Gibbard2004; Guobytė and Satkūnas Reference Guobytė, Satkūnas, Ehlers, Gibbard and Hughes2011). Moreover, a significant variability in soils and fertility, water network and climatic conditions existed in the area between Estonia and NE Poland. These factors affected the social-economic development (Zvelebil and Rowley-Conwy Reference Zvelebil and Rowley-Conwy1984), however they do not explain the settlement pattern entirely as the hilltop settlements were established in more restricted areas near probable exchange networks (Podėnas and Čivilytė Reference Podėnas and Čivilytė2019). Therefore, other social-economic markers must be considered in discussion of the establishment of hilltop settlements in the SE Baltic. The concentration of hilltop settlements in the NE Lithuania and the SE Latvia, River Daugava vicinities and coastal zones of Eastern Baltic are indications of active economic development in these areas. The interconnection between local communities and outside travelers stands out as one of the most probable reasons behind a specific spatial distribution of hilltop settlements.

The existence of hilltop settlements indicates several crucial aspects: rising social tensions and behavioral change in local communities, the usage and importance of the coastal and River Daugava routes. Furthermore, these sites contain one of the earliest finds of locally executed metallurgy (Čivilytė Reference Čivilytė2014; Sperling Reference Sperling2014) and crop-rich archaeobotanical assemblages (Minkevičius et al. Reference Minkevičius, Podėnas, Urbonaitė-Ubė, Ubis and Kisielienė2019). However, a detailed timeline does not exist for the processes such as adoption of full agriculture (Piličiauskas Reference Piličiauskas2016; Piličiauskas et al. Reference Piličiauskas, Kisielienė and Piličiauskienė2017; Grikpėdis and Motuzaite Matuzeviciute Reference Grikpėdis and Motuzaite Matuzeviciute2018), beginning of metallurgy (Čivilytė Reference Čivilytė2014), appearance of new burial practices (Šturms Reference Šturms1936a, Reference Šturms1936b) and hilltop settlements in the southeastern Baltic. Consequently, this makes it hard to take relevant steps towards understanding whether the region’s agricultural development has resulted in a more active interest of neighboring cultures, or have the internal developments in the foreign areas driven the neighboring cultures to explore new markets, impacting communities such as the ones settled in the SE Baltic and transferring their knowledge to them in return for an established new marketFootnote 4 area.

This study aims to further the discussion of the emergence of hilltop settlements in the SE Baltic by presenting new 14C dates from Lithuania and critically reviewing the earliest dates from the region.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

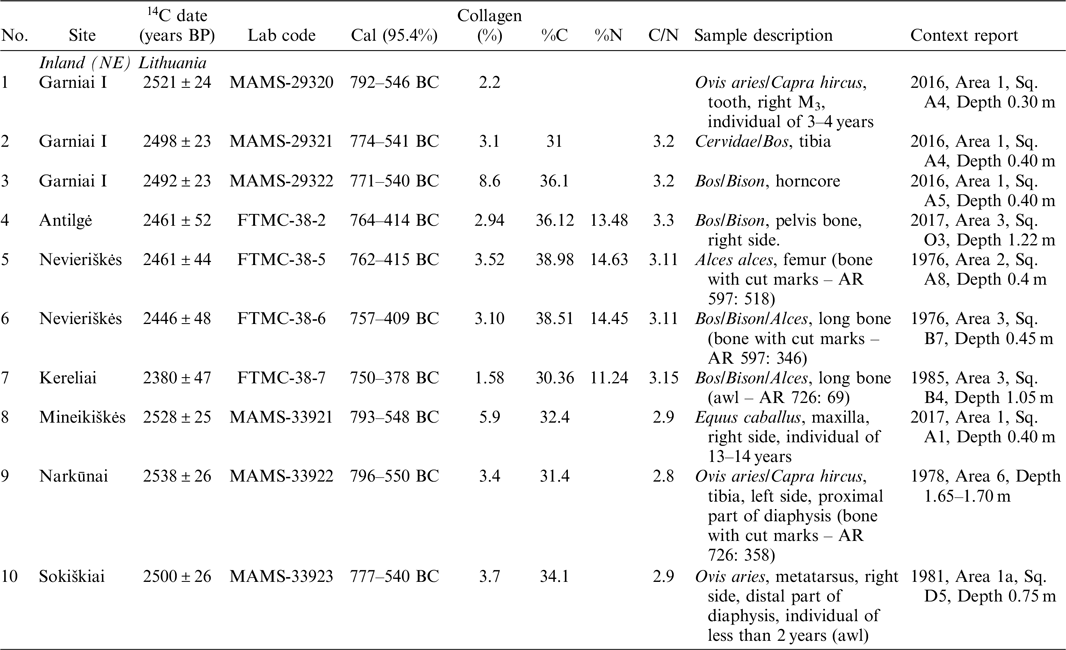

Table 1 presents the new dates from NE Lithuania. The samples were collected from unworked and worked animal bones. The assemblages used in the study consist of data from recently excavated Garniai I, Mineikiškės and Antilgė hilltop settlements and legacy collections of Narkūnai, Kereliai, Sokiškiai and Nevieriškės. Animal bones were identified by G. Piličiauskienė. In the Appendix, a summary of 14C dates has been constructed with an objective to discuss appearance and the earliest development of hilltop settlements in the Southeastern Baltic. This paper reviews all dates from the earliest to the 400 cal BC, i.e. the approximate end of the Hallstatt radiocarbon calibration plateau.

Table 1 New 14C-AMS dates of the inland (NE) Lithuania hilltop settlements. Blank = data not reported. (See the Appendix for dates from coastal Lithuania)

Including new data presented in this paper, currently 60 14C dates from 17 Southeastern Baltic sites are known. First 14C dates on charcoal samples were published by J. Graudonis (Reference Graudonis1989) in the monograph dealing with Ķivutkalns hilltop settlement. After a 17-yr halt, radiocarbon dating started to be routinely included into research design for this type of settlement (Egoreichenko Reference Egoreichenko2006). The same year marked the start of using different kinds of samples, as A. Kriiska and M. Lavento (Reference Kriiska and Lavento2006) published the first dating results of carbonized surface residues on pottery. Further studies included zooarchaeological (Oinonen et al. Reference Oinonen, Vasks, Zariņa and Lavento2013) and archaeobotanical samples (Minkevičius et al. Reference Minkevičius, Podėnas, Urbonaitė-Ubė, Ubis and Kisielienė2019). Supplementary Material 1 presents a more detailed review of dated sites alongside known information on the sample collection. In all, including the new data, this paper reviews 14C dating results of 30 charcoal samples, 14 animal and 2 human bones, 8 grains, and 6 carbonized surface residues on pottery.

Sites and Background of Sample Collection

Inland Lithuanian hilltop settlements together with sites from SE Latvia and NW Belarus account for the largest portion of the Bronze Age hilltop settlement pattern (Figure 1). The active and socially tense region was archaeologically investigated from the very beginnings of the 20th century (Krzywicki Reference Krzywicki1914, Reference Krzywicki1917) and has provided rich archaeological collections from at least 31 sites from Lithuania alone. This study dates 4 of the most frequently mentioned cases (Kereliai, Narkūnai, Nevieriškės, and Sokiškės) in the literature (Grigalavičienė Reference Grigalavičienė1986a, Reference Grigalavičienė1986b, Reference Grigalavičienė1992, Reference Grigalavičienė1995; Volkaitė–Kulikauskienė Reference Volkaitė-Kulikauskienė1986; Luchtanas Reference Luchtanas1992; Čivilytė Reference Čivilytė2014; Podėnas et al. Reference Podėnas, Čivilytė, Bagdzevičienė and Luchtanas2016a, Reference Podėnas, Luchtanas and Čivilytė2016b) and 3 recently archaeologically investigated sites (Antilgė, Garniai I, and Mineikiškės). All samples were selected from herbivore remains, found in cultural layers during archaeological excavations.

Numerous archeozoological finds form Kereliai, Narkūnai, Nevieriškės, and Sokiškiai hilltop settlements were collected during the archaeological investigations, however animal bone collections are missingFootnote 5 . Therefore, samples for this study were selected by reassessing the significantly smaller collection of worked bone finds stored in Lithuanian National Museum. All of these four hilltop settlements were reinhabited later in the Iron Age or the Medieval period. Two samples from Nevieriškė hilltop settlement were Alces femur and Ruminantia‘s (Bos/Bison/Alces) long bone. Alces femur with cut marks was found in the topsoil disturbed by modern agricultural activity and Bos/Bison/Alces long bone was uncovered in the upper part of the charcoal-rich cultural layer. Bronze Age horizon in Kereliai hilltop settlement was dated by taking a sample from an awl (Ruminantia‘s long bone) found in charcoal-rich cultural layer. Sokiškiai was dated by taking a sample from an awl made from Ovis aries metatarsus found in insufficiently documented contextFootnote 6 . Lastly, sample for radiocarbon dating of Narkūnai hilltop settlement was taken from Ovis aries/capra hircus tibia with cut marks. This was uncovered in the southern part of the settlement at the depth of 1.65–1.7 m. Assessment of the area description in the original excavation report (Kulikauskienė and Luchtanas Reference Kulikauskienė and Luchtanas1978) revealed that this depth could point to the context behind the palisade, close to undisturbed soil. Notably, the find was discovered in the same area as the previously supposed typologically earliest bronze pin ever found in the hilltop settlements (Volkaitė-Kulikauskienė Reference Volkaitė-Kulikauskienė1986; Luchtanas Reference Luchtanas1992). The pin resembled Central Polish Majków type (ca. 1500–1100 BC) bronze pins, but A. Čivilytė (Reference Čivilytė2014) has argued that analogy is rather remote and the Narkūnai find should be assessed with a caution.

The absence of datable samples has inspired archaeological investigations of Antilgė, Garniai I and Mineikiškės hilltop settlements during 2016–2017 (Čivilytė et al. Reference Čivilytė, Podėnas, Vengalis and Zabiela2017a, Reference Čivilytė, Podėnas, Vengalis and Zabiela2017b; Podėnas Reference Podėnas and Zabiela2018; Podėnas et al. Reference Podėnas, Troskosky, Kimontaitė, Čivilytė and Zabiela2018; Poškienė et al. Reference Poškienė, Podėnas, Luchtanas and Zabiela2018). Three sites share similar geomorphological characteristics. Hilltop settlements had been established on kames in Baltic Uplands that was formed by retracting Fennoscandian Ice Sheet (Rinterknecht et al. Reference Rinterknecht, Bitinas, Clark, Raisbeck, Yiou and Brook2008; Troskosky et al. Reference Troskosky, Podėnas and Dubinin2018). All sites lacked previous human activity. In addition, only Antilgė was inhabited later in 1st century BC–2nd century. AD. Based on the artifact typologies alone, Garniai I and Mineikiškės represent only the Late Bronze Age horizons. The samples of the two sites were collected from the edges of habitation areas, where cultural layers are were generally thicker due to the agglomeration of waste and refuse (Figure 2). Sample from Antilgė hilltop settlement was taken from the ditch that was surrounding the court. The latter sample was from the fill, moved from the habitation area. Other dates and finds from Antilgė indicated that the ditch was constructed in the Roman Iron Age (Poškienė et al. Reference Poškienė, Podėnas, Luchtanas and Zabiela2018).

Figure 2 A section of the Garniai I site, Area 1 with the calibrated AMS 14C dates. Excavations of 2016. Drawing by V. Podėnas.

AMS Radiocarbon (14C) Dating of Lithuanian Sites

Direct AMS 14C dating of the 10 animal bones was undertaken at Curt-Engelhorn-Zentrum Archaeometrie, Mannheim (Germany) and Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, Center for Physical Sciences and Technology, Vilnius (Lithuania). 5 samples were selected from the collections of Lithuanian National Museum. There was no information on consolidants used for conservation of the material. Remaining samples were collected during 2016–2017 archaeological excavations in Antilgė, Garniai I and Mineikiškės hilltop settlements. The collagen extracted from the bone samples was purified by ultrafiltration (fraction >30kD) and freeze-dried. Afterwards, collagen was combusted to CO2 in an Elemental Analyzer (EA), which later converted catalytically to graphite. In this study all radiocarbon ages were calibrated using the OxCal 4.3.2 software (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2017) and IntCal13 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). Calibrated dates are presented at 95.4% probability.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The 14C dating results are presented in Table 1. All 10 samples proved to contain sufficient amount of collagen and C/N ratios (2.8–3.3) indicated well preserved collagen in all of them (Madden et al. Reference Madden, Chan, Dundon and France2018). Herbivore bones collected from 7 sites were dated to roughly similar timeframe between 8th and 6/4th centuries cal BC. Results have proved that the studied Inland Lithuanian sites were contemporaneous with the most of previously dated samples from other hilltop settlements. However, the identification of hilltop settlement establishment initial phase in the SE Baltic relies on the deviations from the Hallstatt radiocarbon calibration plateau (ca. 800–400 cal BC).

Reliability of the previous dates is also severely limited by the fact that none of the charcoal samples were further examined to determine the species and age of the plant. Moreover, previously dated animal bones had not been identified to be herbivores (Oinonen et al. Reference Oinonen, Vasks, Zariņa and Lavento2013), except for Ovis aries bone from Asva (Rannamäe et al. Reference Rannamäe, Lõugas, Speller, Valk, Maldre, Wilczyński, Mikhailov and Saarma2016), which was dated to Poz-58805: 2505 ± 30, or cal BC 786–522 (2σ). Furthermore, more significant interpretational problems lie in assessing the dated samples of carbonized surface residue on pottery (Kriiska and Lavento Reference Kriiska and Lavento2006; Sperling Reference Sperling2014). The published dates lacked measurements of δ13C and δ15N stable isotopes, therefore it is impossible to estimate possible aquatic reservoir effects on samples.

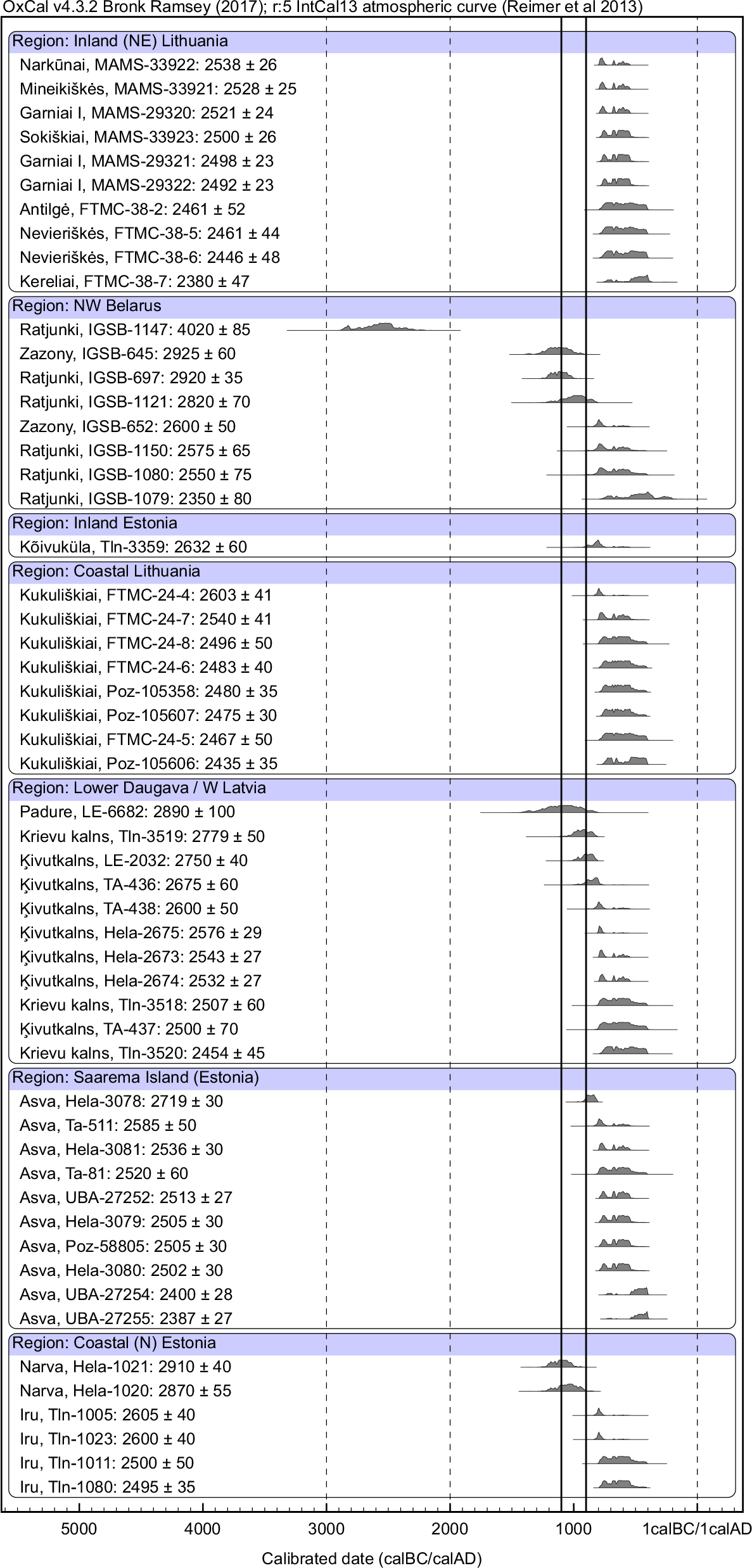

Dating of the inland cluster is significantly supplemented by the studies of hilltop settlements in NE Belarus. They are separated only by ca. 50 km from the sites investigated in this study. 6 out of 13 dates stand out among them as predating the Hallstatt plateau: IGSB-645: 2925 ± 60, IGSB-648: 3170 ± 200, IGSB-697: 2920 ± 35, IGSB-1121: 2820 ± 70, IGSB-1147: 4020 ± 85, IGSB-1148: 2970 ± 190. These dates are ambiguous due to the poor sample documentation and lack of context specification. Therefore, results raise concerns that charcoal collected during the excavations was not necessarily associated with archaeological context of the hilltop settlement. The dates may in fact represent other unidentified events, such as forest fires, that occurred before the establishment of the hilltop settlement. Most of the dated samples in Ratjunki and Zazony sites came from an unspecified layer, except for one case. A charcoal from a pit in Zazony provided a date of IGSB-652: 2600 ± 50, or cal BC 895–546 (2σ). Therefore, the claims that hilltop settlement appearance in the inland cluster of NE Lithuania, NW Belarus and SE Latvia in early to middle 2nd millennium BC (Gimbutienė Reference Gimbutienė1985; Egoreichenko Reference Egoreichenko2006) rely on questionable dates and stray finds. Lastly, the only site situated in inland Estonia (Kõivuküla) was dated to first half of I millennium BC, i.e. Tln-3359: 2632 ± 60, or cal BC 923–551 (2σ). Thus, based on the 10 new dates from Lithuania and more reliable Zazony and Kõivuküla dates (Figure 3) it is most likely that inland hilltop settlements were established sometime during 10th–6th centuries cal BC.

Figure 3 Diagram of calibrated 14C dates of the hilltop settlements in the SE Baltic. Based on the Appendix (see further references). Dates with the greater margin of error than 100 were removed as not precise enough. Solid lines mark the likeliest period (1100–900 cal BC) of the emergence of hilltop settlements in the region.

Hilltop settlements in the coastal Southeastern Baltic and its vicinities have aided the debate significantly by providing a series of dates. Coastal Lithuania is best represented by the Kukuliškiai site with 8 AMS 14C dates on the grains of cultivated plants (Minkevičius et al. Reference Minkevičius, Podėnas, Urbonaitė-Ubė, Ubis and Kisielienė2019). These have proved to be of similar chronology as the inland sites. Possibly the earliest dated samples were collected in sites from coastal Latvia and Estonia. These include charcoal from Ķivutkalns, Krievu kalns and Padure hilltop settlements and carbonized surface residue on pottery found in Asva and Narva settlements. The aforementioned ambiguity in interpretation of carbonized surface residue on pottery samples is especially significant in the case of Narva. Therefore, it is essential to obtain more reliable data to test the hypothesis that Narva hilltop settlement was established already in 13th–10th centuries cal BC, which would indicate an unlikely scenario of the earliest enclosed settlements in the SE Baltic emerging farther away from River Daugava route, in the region’s most NE corner. Otherwise, the earliest dates from Ķivutkalns situated in lower reaches of River Daugava (LE-2032: 2750 ± 40, or cal BC 996–816 (2σ), and TA-436: 2675 ± 60, or cal BC 976–771 (2σ)) correlate with the rest of the dates that were outside the Hallstatt radiocarbon calibration plateau. However, it is unlikely that dates LE-2032 and TA-436 refer to the initial phase of the settlement as stratigraphy indicated that settlement’s layer was established only after the usage of the cemetary had ceased at the hilltop (Graudonis Reference Graudonis1989). Further studies (Oinonen et al. Reference Oinonen, Vasks, Zariņa and Lavento2013; Mittnik et al. Reference Mittnik, Wang, Pfrengle, Daubaras, Zariņa, Hallgren, Allmäe, Khartanovich, Moiseyev, Tõrv, Furtwängler, Valtueña, Feldman, Economou, Oinonen, Vasks, Balanovska, Reich, Jankauskas and Krause2018) of the burials had dated the majority of human bones to ca. 8th–5th centuries BC (Hallstatt plateau). Therefore, Ķivutkalns hilltop settlement was established later than the LE-2032 and TA-436 have dates indicated. The charcoal samples for these dates could had been collected from ambiguous contexts. More reliable data was collected in the Latvian coastal zone, specifically in Krievu kalns (Tln-3519: 2779 ± 50, or cal BC 1047–821 (2σ)) and Padure (LE-6682: 2890 ± 100, or cal BC 1381–837 (2σ)) hilltop settlements (Vasks et al. Reference Vasks, Kalniņa and Daugnora2011; Doniņa et al. Reference Doniņa, Vasks, Vilka, Urtāns and Virse2014). Charcoal samples from the hearth and a posthole provided reliable archaeological context with the only drawback being the lack of identification of wood species and age estimation. Thus, current evidence suggests that hilltop settlements in coastal Southeastern Baltic appeared between 11th and 9th centuries cal BC.

The knowledge on the process of emergence of hilltop settlements is blurred by the low chronological resolution. This is further complicated by the Hallstatt calibration plateau. Therefore, it is difficult to understand how enclosed sites spread throughout the SE Baltic. There are three possible interpretations of current data: (1) the earliest hilltop settlements were established and spread swiftly throughout the coastal zone and appeared in inland later; (2) the earliest hilltop settlements established in Western Latvian coastal zone where there is a significant Scandinavian influence and gradually spread throughout the region via coastal, River Daugava and less significant water network communication; or (3) the earliest hilltop settlements emerged in the SE Baltic region’s west and east simultaneously were affected by the independent processes. More reliable data suggest that the second hypothesis seem the likeliest as the dates acquired from clear contexts indicate the earliest hilltop settlements concentrating in the vicinities of coastal Latvian zone. These sites had a significant role in developing interregional communication and exchange in the SE Baltic (Podėnas and Čivilytė Reference Podėnas and Čivilytė2019). Contacts with Scandinavian and Lusatian (Southern Baltic) cultures had provided further stimuli for the development of local societies after the full adoption of farming. Furthermore, the active communication had provided the Southeastern Baltic societies with stable metal supply. Even though adoption of foreign cultural elements is visible in the archaeological record, they transitioned to the Southeastern Baltic only on a limited scale. A good example is the stone-ship burial practices, inherent to the Nordic Bronze Age. These were actively used in Gotland and coastal Sweden (Wehlin Reference Wehlin2013), and also appear in the active contact zones in the SE Baltic, such areas as Saarema Island (Lang Reference Lang2007) and Western Latvia (Graudonis Reference Graudonis1967). These burial rites were not adopted by the local communities and had not spread to the inland region. However, it is likely these communities had established the hilltop settlements due to active usage of trade networks that were stimulated by Scandinavian settlements near the localities of stone-ship burials (Šturms Reference Šturms1947; Podėnas and Čivilytė Reference Podėnas and Čivilytė2019).

CONCLUSIONS

New AMS dates obtained from Bronze Age hilltop settlements have helped to refine the chronology of their appearance and early development in the Southeastern Baltic. They have provided comparative material to challenge previously constructed chronologies that dated emergence of hilltop settlements in the NE or SE areas of the SE Baltic region during early-mid II millennium BC. The securely dated contexts indicates contrastingly that these inland sites emerged significantly later during 10th–6th centuries cal BC. A review of all dates in the SE Baltic have indicated that coastal sites were established earlier than the inland ones, i.e. 11th–9th centuries cal BC. This points to the significance of coastal communication and western or southwestern directions of economic influence related to Nordic and Lusatian cultures.

This study highlights the necessity of further application of systematic AMS 14C dating, meticulous recording and thorough examination of the relations between the samples and specific archaeological context. This paper illustrated that data from the legacy excavations is plagued by the lack of proper documentation. The earliest dates were acquired by dating charcoal samples collected in ambiguous contexts exclusively. However, the existing dataset is considerably modest, therefore it is expected that further studies into the field would alter and correct the model proposed in this paper.

Archaeological evidence presents an intriguing case of societal change following the adoption of agriculture which took place significantly later than in neighboring Western and Southern Baltic regions. Local communities were subjected to significant economic advantages in metal trade and confronted the Bronze Age culture on an unprecedented scale. We are on the threshold of understanding how these communities responded to the external stimuli and explored the changing social, economic, and technological landscape.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to Giedrė Piličiauskienė for her kind assistance with animal bone identification and sample selection for this study. Thank you Karolis Minkevičius, Uwe Sperling, Andrejs Vasks, and Vanda Visocka for all the help in providing the information on lesser-known dates and archaeological context of several samples. For AMS dating presented in this study special thanks go to Ronny Friedrich and Klaus-Tschira-Archäometrie-Zentrum, Curt-Engelhorn-Zentrum Archaeometrie, Mannheim, and Žilvinas Ežerinskis and Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, Center for Physical Sciences and Technology, Vilnius. Lastly, I would like to thank K. Minkevičius and Agnė Čivilytė for providing valuable commentaries and proofreading the manuscript of the paper. This research was funded by a Lithuanian state PhD study program.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2019.152

APPENDIX

14C dates of the Southeastern Baltic hilltop settlements from the earliest to the end of the 5th century cal BC (end of the Halltsatt radiocarbon calibration plateau). Numeration continues from Table 1.