INTRODUCTION

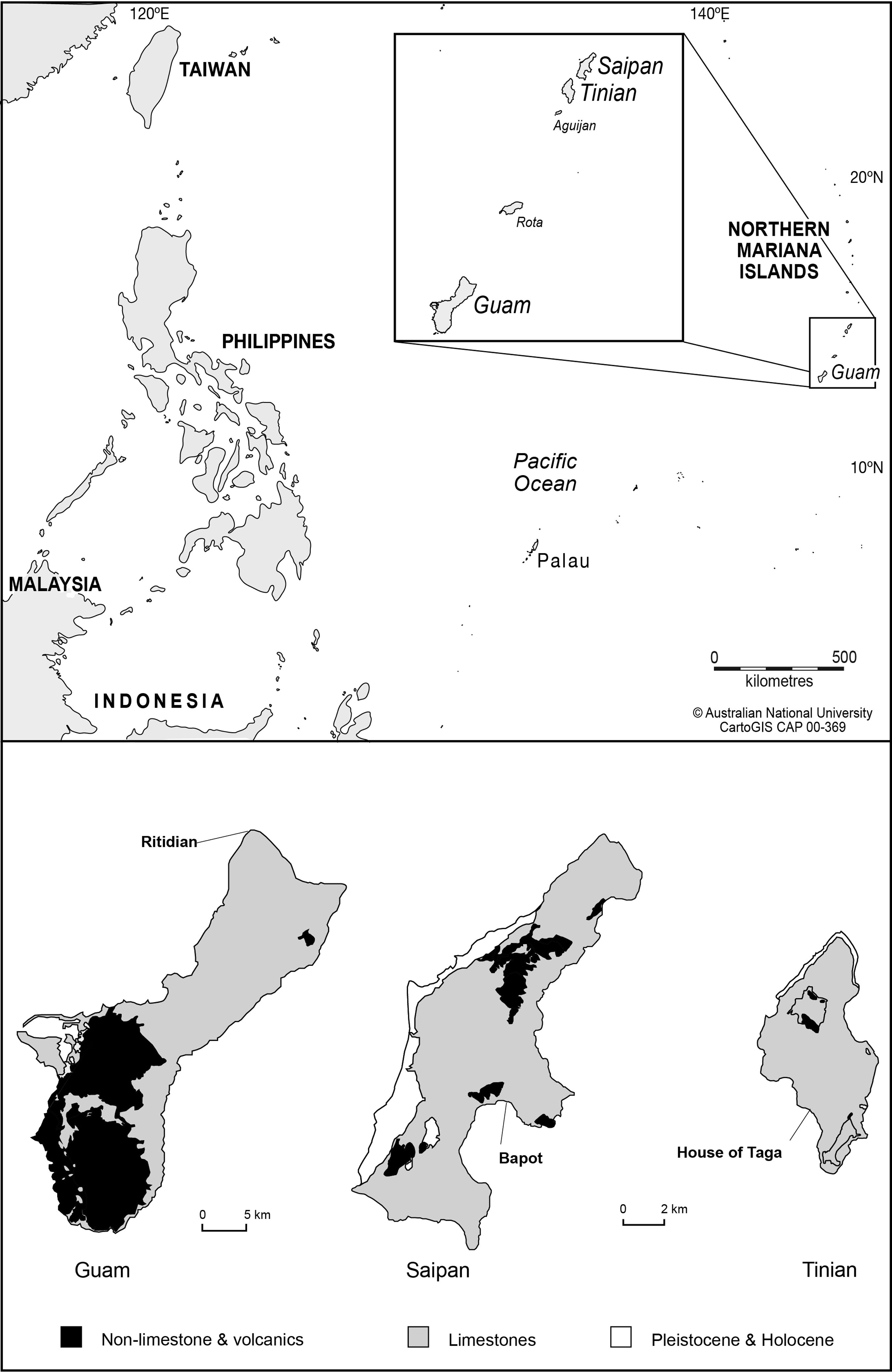

The colonization of the Pacific is an important chapter in the story of human dispersal. Dating archaeological sites in the Pacific is not easy, and the development of meaningful models of regional settlement has been fraught with problems (Spriggs Reference Spriggs, Chiu and Sand2007; Hung et al. Reference Hung, Carson, Bellwood, Campos, Piper, Dizon, Bolunia and Oxenham2011; Rieth and Athens Reference Rieth and Athens2017). One area of concern is the calibration of “marine” shell 14C dates and what reservoir correction to apply to the global marine 14C curve (e.g., Clark et al. Reference Clark, Quintus, Weisler, St Pierre, Nothdurft, Feng and Hua2016; Petchey and Kirch Reference Petchey and Kirch2019; Petchey Reference Petchey2020), especially in areas where terrestrial materials suitable for dating are scarce, but shells are abundant. Carson (Reference Carson2020) gives an overview of his research into the marine 14C reservoir around the Mariana Islands (Figure 1) using archaeological material. He uses this information to reinforce his theory (Carson Reference Carson2014) that settlement occurred by at least 3450 cal BP (1500 BC) in the region. However, his conclusions are contrary to marine reservoir research undertaken by Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017) and subsequently expanded on by Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018). We discuss each point of contention below.

1. A suspiciously wide variance in ΔR or a hard water impact on estuarine shell?

Figure 1 Map of the Mariana Islands and simplified surficial geology of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian based on Riegl (Reference Riegl and Hopley2011: their Figure 5). Archaeological sites with old marine shell ages shown relative to limestone bedrock where hard waters are likely.

Dating of shell from the Mariana Islands has a long and troubled history (see Cloud et al. Reference Cloud, Schmidt and Burke1956: 4; Clark et al. Reference Clark, Petchey, Winter, Carson and O’Day2010) because the three main islands, Saipan, Guam, and Tinian, are dominated by limestone bedrock (Mink and Vacher Reference Mink, Vacher, Vacher and Quinn1997; Stafford et al. Reference Stafford, Mylroie and Jenson2002; Carruth Reference Carruth2003). Freshwater, held within the aquifer lens under these islands, takes up bicarbonate ions as it seeps through the calcareous strata. Springs discharging at the coast introduce these old waters into the shells of animals that live close to the shore. This hard water effect is a recognized problem when dating shellfish in the Pacific (Dye Reference Dye1994; Spennemann and Head Reference Spennemann and Head1998; Petchey and Clark Reference Petchey and Clark2011), and offsets from the global marine calibration curve (a ΔR) can result in hundreds of years of error in some chronologies if incorrectly interpreted. Carson (Reference Carson2020) does not mention the limestone bedrock of the Mariana Islands or the possibility of a hard water effect on the ages of his Anadara sp. shells, despite being discussed in detail by Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017).

Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017: their Table 3) report a location and species-specific reservoir correction value of 218 ± 57 14C yearsFootnote 1 for Anadara (identified as Anadara cf. antiquata). This value was calculated from the 14C results of “paired” (contemporary) short-lived charcoal and shell samples excavated from the site of Unai Bapot. Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017) concluded that a hard water influence caused this extreme positive ΔR-value. Carson (Reference Carson2020: 13, point 6) implied that this correction was unusually large and indicated a mis-association of charcoal and shell pairs (we discuss this further below). Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017) also reported a reef-dwelling Conus sp. shell that returned a separate ΔR-value of 23 ± 37 14C years. They considered this a suitable correction for shellfish from reef/open ocean environments not influenced by hard water. Carson (Reference Carson2020: 13, point 7) fails to mention the Conus value or the explanations given by Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017) for the variation seen.

Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017) had observed that the δ13C of Anadara sp. and Gafrarium sp. shells was lower than reef taxa. Theoretically, marine bivalves should have a δ13C value at least 2‰ more positive (Tanaka et al. Reference Tanaka, Monaghan and Rye1986; Romanek et al.Reference Romanek, Grossman and Morse1992) than the dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in the ocean, which averages ˜1.3 to 1.7‰ in this region. In lagoons and estuaries, the uptake of DIC derived from decayed plant material is responsible for more negative δ13C values. This observation provided a means of identifying individual animals that were less likely to be affected by hard water. This theory of isotopic variation and the possibility of a changing ΔR over time was investigated in more detail in a subsequent and more extensive paper by Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018), which Carson (Reference Carson2020) does not appear to have read.

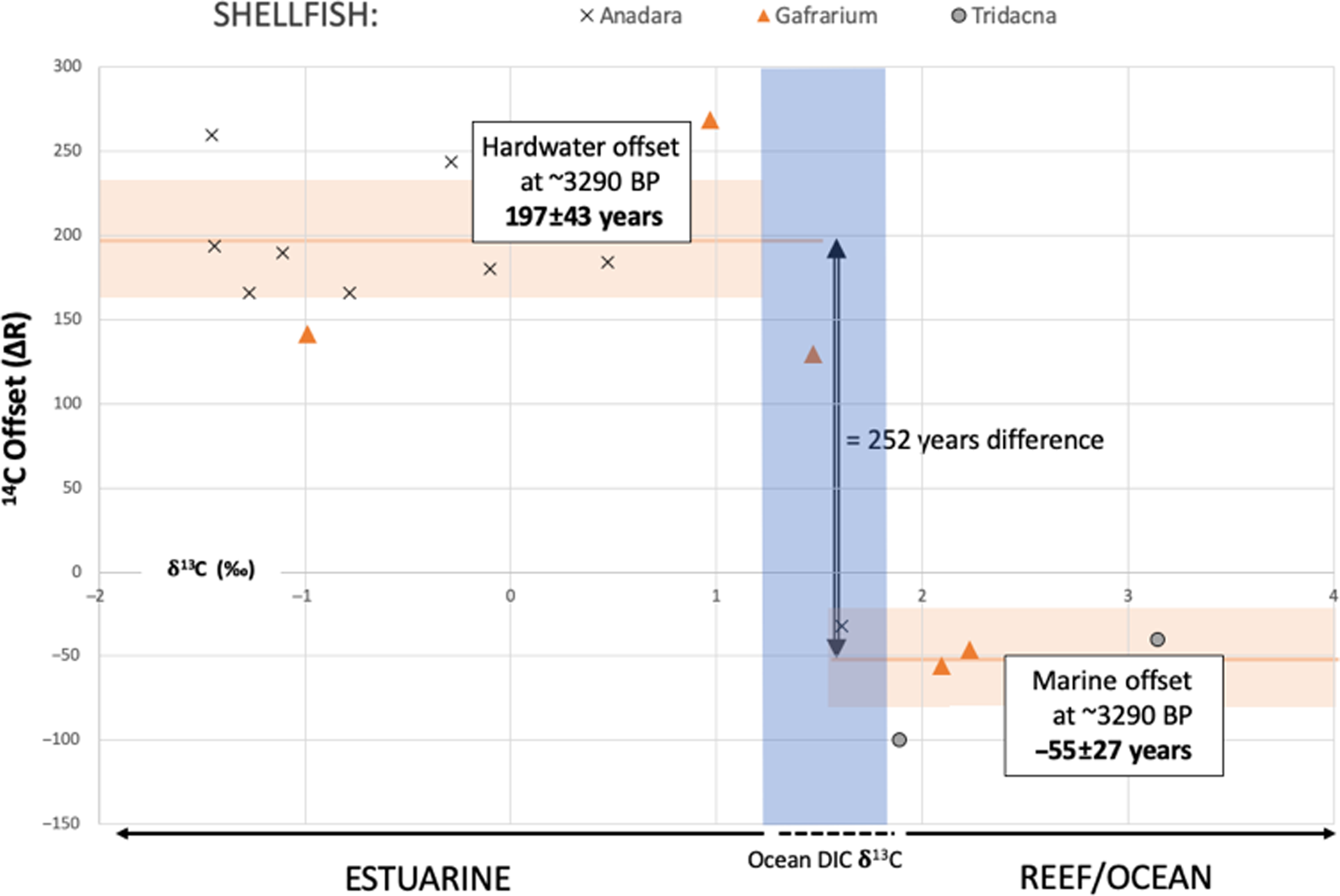

Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018) compared carbon isotopes of “estuarine” taxa, Anadara, and Gafrarium to reef taxa (here referred to as “marine”) such as Tridacna and Conus Footnote 2 . To test if some Anadara or Gafrarium could be reliably dated, Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018) measured δ13C of 57 Anadara and 45 Gafrarium shells and identified only a handful (<5%) with values more positive than the average ocean DIC value (i.e., >1.3‰). These were dated and returned radiocarbon ages much younger than individuals with more negative δ13C values (Figures 2 and 3). Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018) demonstrated that at Unai Bapot 3200 years ago, filter-feeding bivalves identified as “marine” based on δ13C (n=5, including 2 Anadara, 2 Gafrarium, and 1 Tridacna shell), had a ΔR offset from the global Marine13 curve of −55 ± 27 14C years. This value is equivalent to ΔR from South Pacific marine contexts dated to the same time-period (Petchey Reference Petchey2020). Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018) calculated an average “estuarine” ΔR offset of 197 ± 43 14C years for Gafrarium (n=3) and those Anadara (n=10) shells with a δ13C <1.3‰ (Figure 2). These results are consistent with the ΔR offsets previously reported by Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017). At this point, we do not have any additional data to support the application of this estuarine value to taxa outside of the confines of Unai Bapot because a range of hydrological, geological, and oceanographic conditions impact the shellfish. Therefore, there is no guarantee that taxa with a δ13C <1.3‰ will be affected by hard water, and researchers must assess isotopic results from limestone areas on a site-by-site basis. The mix of limestone and volcanic geologies and variable drainage across the Mariana Islands suggests that additional due diligence is needed when interpreting estuarine shell dates across this region. Petchey and Clark (Reference Petchey and Clark2011) have also demonstrated a link between shell δ13C hard water at sites on the limestone island of Tongatapu.

2. Inconsistencies in the stratigraphy and dating at Unai Bapot

Figure 2 Isotopic (δ13C versus ΔR) separation between estuarine and marine shellfish from Unai Bapot (layers V to VII) (adapted from Petchey et al. Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018). Note: ΔR values have been calculated with Marine13 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013) and are not suitable for use with Marine20 (Heaton et al. Reference Heaton, Köhler, Butzin, Bard, Reimer, Austin, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Hughen, Kromer, Reimer, Adkins, Burke, Cook, Olsen and Skinner2020).

Figure 3 Charcoal and shell radiocarbon dates from Unai Bapot Area A excavation, Unit 4. (a) All shell dates corrected using a ΔR of −55 ± 27 14C years. (b) Shell dates corrected using δ13C determined “estuarine” (<) and “marine” (>) ΔR values of 197 ± 43 and −55 ± 27 14C years, respectively. The grey bar indicates the maximum 95% prob. range for all samples of similar age. The ellipses indicate displaced samples in the upper layer IV and III deposits and surface disturbance. Black arrows point to 1500 BC. Marine13 and IntCal13 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013) are used to calibrate all dates.

Carson (Reference Carson2020: 13, points 1–3) outlines problems with the paired shell and charcoal dates used in the 2017 study. Specifically, he states that charcoal dates did not originate from discrete features and that paired samples were selected from redeposited contexts in the site’s lower layers.

In total, the ΔR research undertaken by Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017, Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018) compiled 40 radiocarbon dates on shell (n= 34, including 4 different shell taxa specifically selected for ΔR evaluation), charcoal (n= 5, including short-lived coconut), and rail bone (n=1). These came from a single 1 m × 1 m excavation unit (Unit 4). This formed part of a more extensive 3 m × 3 m excavation (Block A) 5–10 m further inland than Carson’s 2016 excavations on the same site (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Petchey, Winter, Carson and O’Day2010). Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018) evaluated the radiocarbon dates in stratigraphic sequence to assess disturbance over time using the Bayesian sequence and outlier approaches in OxCal (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a, Reference Bronk Ramsey2009b) (Figure 3). Charcoal samples from 48 cm down to 260 cm depth were grouped with shells from the same depths, and “estuarine” and “marine” ΔR calculated using the paired charcoal/shell approach (Figure 3). The reservoir corrected shell sequence was then compared to an additional 30 charcoal radiocarbon dates from nearby Block A excavation units (Petchey et al. Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018: their fig 8), including 16 charcoal samples from the lowest deposits below 200cm depth. The charcoal chronology produced a modeled starting date of 3290–3170 cal BP (95% prob.) comparable to the reservoir corrected shell chronology starting 3240–3130 cal BP (95% prob.). There was no evidence of disturbance in either the dates or artifacts until the upper spits of Layer V and above (above 190 cm depth). Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018) concluded that a second phase of activity, starting ˜2830 cal BP (880 BC) after a period of abandonment (Figure 3b), caused upward movement of earlier cultural material.

Carson’s 2016 excavation was unable to locate any charcoal from the oldest contexts. Instead, these lowest layers were dated using Anadara shell corrected with a regional Mariana Islands ΔR of –49 ± 61 14C years (Carson Reference Carson2020: his Table 2). His available charcoal dates (n= 5) are comparable to those from the lowest deposits in the Block A excavation reported by Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Petchey, Winter, Carson and O’Day2010). The 5 Anadara dates reported by Carson (Reference Carson2020) have δ13C <1.3‰ and reservoir corrected (using a ΔR of –49 ± 61 14C years) calibrated ages of between 1946 and 1230 BC (95.4%).

Carson (Reference Carson2020: 13, point 4) also questions the statistical methods employed by Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017: their Table 3). Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017) used a weighted mean methodology for combining ΔR and reported the standard deviation for the error term, a conservative approach designed to encompass variability (see Russell et al. [Reference Russell, Cook, Ascough, Scott and Dugmore2011] for the limitations of this method). Carson used the unweighted mean and failed to propagate the uncertainty correctly, instead taking the unweighted mean of the error term. Additionally, the individual estuarine ΔR values reported by Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017) differ from those Carson represents as our reported values. This difference is the result of Carson (Reference Carson2020: 11) using the Deltar online software package (http://calib.org/deltar) to recalculate the ΔR from our original pairs. This program uses the full probability distribution functions rather than an intercept method previously favored for ΔR research (see Reimer and Reimer Reference Reimer and Reimer2017). Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017: their Table 3) used the intercept methodology as outlined by Reimer et al. (Reference Reimer, McCormac, Moore, McCormick and Murray2002). The Deltar program was not available at the time of writing Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017) but was used in the 2018 study. The two methods produce results that are statistically the same in this instance.

3. Variability in marine reservoir values across the Mariana Islands. A uniform ΔR?

Carson (Reference Carson2020: his Table 2, p. 13–20) discusses in some detail the 5 charcoal/shell pairs he used to calculate the regional ΔR of -49 ± 61 14C years. These pairs come from 3 sites: Ritidian, the House of Taga, and Unai Bapot (Figure 1). Carson suggests the consistency of these results supports his conclusions (Carson Reference Carson2020: 13, point 5). However, only 3 out of the 5 ΔR pairs conform to the requirements for ΔR evaluation (i.e., that the age is determined by dating short-lived, “paired” terrestrial materials from contemporary contexts) (Ascough et al. Reference Ascough, Cook and Dugmore2005; Petchey Reference Petchey, Fairbairn, O’Connor and Marwick2009; Russell et al. Reference Russell, Cook, Ascough, Scott and Dugmore2011; Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Ascough, Lougheed, Rasmussen, Gell, Weckström, Skilbeck and Saunders2017), and these do not disprove the findings of Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017, Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018) at Unai Bapot. These are discussed in more detail below.

Carson (Reference Carson2020: his Table 2) reports a single ΔR-value of −90 ± 48 14C years for Unai Bapot, Layer VI. The charcoal material (Beta-448705; 3110 ± 30 BP) used was not identified as short-lived and could conceivably have significant inbuilt age. It, therefore, cannot be used in this type of analysis (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, McCormac, Moore, McCormick and Murray2002), despite the apparent close association of shell within a broken pottery bowl sitting in a hearth. Four wood charcoal dates reported from Layer V are younger (2840 ± 40 BP to 2960 ± 30 BP) but consistent with the lower layers of the Area A excavation undertaken by Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Petchey, Winter, Carson and O’Day2010). All Anadara dates from the site have δ13C values between −1.5‰ and +0.2‰, indicative of estuarine carbon input. The extensive study by Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018) at the same site indicates that all these Anadara dates will be affected by hard water, the oldest shell 14C ages (between 3530 ± 30 bp and 3710 ± 50 bp) from lower layers VI and VII are likely a manifestation of this issue. Additional dates on closely associated short-lived terrestrial material are needed to confirm Carson’s (Reference Carson2020) hypothesis.

Carson (Reference Carson2020: his Table 2) identified three charcoal/shell pairs from the Ritidian habitation site on Guam’s northern tip. Only two pairings use identified short-lived charcoal (Cocos nucifera endocarp). The positive δ13C values (+1.5‰ and +2.1‰) for paired Anadara shells are consistent with the uptake of ocean DIC, and the calculated ΔR (1 ± 56 and −70 ± 80 14C years) are comparable to the reef/ocean reservoir value reported by Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018). Carson (Reference Carson2020), however, bases his 1500 BC settlement age on the oldest cultural Anadara dates found at the site (Beta-253681; 3430 ± 40 BP, Beta-433371; 3480 ± 30 BP), both of which have δ13C values less than 1.3‰ (−0.7‰ and −1.9‰ respectively) (Carson Reference Carson2020: his Table 1). Several dates on non-cultural shell material from a similar depth to Beta-253681 returned a range of ages (3480 ± 40 BP, 3750 ± 30 BP, and 4100 ± 50 BP). They, therefore, do not confirm the reliability of this age interpretation, and a more robust ΔR assessment needs to be undertaken at this site.

Material excavated from the House of Taga on Tinian provided a single ΔR. The charcoal sample (Beta-313866; 3070 ± 30 BP) is described as “narrow twigs” of unknown diameter. A δ13C value of 0, suggestive of an estuarine source, is reported for the paired Anadara sample (Beta-316283; 3390 ± 30 BP). This single pairing returned a ΔR of −28 ± 48 14C years. More work is required to confirm if the western side of Tinian is unaffected by hard water, but groundwater drainage patterns (Gingerich Reference Gingerich2002) and the fact that most of the island is limestone suggest otherwise (Figure 1; Riegl Reference Riegl and Hopley2011:668). The absence of a hard water effect could be related to ocean currents removing water from the coastline (similarly, Rititian) rather than holding the freshwater near the coast, as happens on the southeast coast of Saipan where Unai Bapot is situated (cf. Petchey et al. Reference Petchey, Anderson, Zondervan, Ulm and Hogg2008, Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018: 182). Five additional Anadara shell dates, also from the lowest cultural layer at the House of Taga, have 14C ages ranging between 3390 ± 30 BP and 3500 ± 30 BP, and δ13C between −1.3‰ and +0.3‰. Ideally, paired terrestrial material is required to confirm the calendar ages of these older Anadara dates.

In a review of ΔR procedures, Russell et al. (Reference Russell, Cook, Ascough, Scott and Dugmore2011) noted that it is essential to carefully evaluate stratigraphic integrity to ensure the samples have not become mixed over time, and that the evaluation of any reservoir offset should not rely on a single set of paired dates. Such a program has been carried out at Unai Bapot by Petchey et al. (Reference Petchey, Clark, Winter, O’Day and Litster2017, Reference Petchey, Clark, Lindeman, O’Day, Southon, Dabell and Winter2018) with over 69 radiocarbon dates and analysis of 17 shell/charcoal pairs that provide a robust re-evaluation and explanation for ΔR discrepancies at that site.

DISCUSSION

Carson (Reference Carson2020: his Figure 3) identifies 8 sites in the Mariana Islands with “confirmed” early settlement dates to support his conclusions. Radiocarbon dates on estuarine shells, unidentified charcoals, or a combination of both form the chronologies for 5 of these sites. In all cases, the plant remains dated were not short-lived and could easily have been decades or centuries old when burnt by the original inhabitants. These would not be considered to produce reliable dates for human arrival on islands in other parts of the Pacific (Wilmshurst et al. Reference Wilmshurst, Hunt, Lipo and Anderson2010; Allen and Huebert Reference Allen and Huebert2014; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Conte, Smith and Szabo2019). Although questions about shell taxa variation and temporal variation in ΔR remain, sufficient evidence exists to doubt early dates on Anadara shells from archaeological contexts around the Mariana Islands. Removing the shell dates from consideration means there is no definite proof of settlement across the island archipelago before 3300 cal BP (1350 BC). We cannot negate an earlier date, but more robust dating programs are required from sites with early cultural remains to demonstrate this beyond a reasonable doubt.

Our proposed younger age for the settlement of the Mariana Islands based on new dates and ΔR assessment of shells from Unai Bapot has significant implications for archaeological research throughout the region because the oldest movement into Western Micronesia and movement into the West Pacific now appear to occur at a similar time (Rieth and Athens Reference Rieth and Athens2017; Fitzpatrick and Jew Reference Fitzpatrick and Jew2018). This suggests people moved through the islands in less than 200 years, a time frame that has consequences for our understanding of cultural development and the impact of environmental change. Given the importance of this argument to Pacific-wide frameworks of early colonization and potential interconnection among colonizing groups, it is critical to evaluate this further with data and procedures designed to achieve robust and precise chronologies (c.f., Bayliss Reference Bayliss2015). Carson’s (Reference Carson2020) paper claiming an initial settlement of the Mariana Islands around 3450 cal BP (1500 BC), using few dates, less than ideal 14C sample selection protocols, and ignoring the possibility of variable hard water impact, does little to forward this goal.