INTRODUCTION

The discovery of a complex of archaeological sites in Ulów has revealed a long history of human settlement in a region previously thought to have been uninhabited in prehistory and especially during the Roman period. The sites are near the village of Ulów in the Middle Roztocze region (Tomaszów Lubelski municipality, Tomaszów County, Lublin Province), part of the Central Polish uplands in southeastern Poland (Figure 1). Archaeological site 3 in Ulów (50°28'9.98''N; 23°18'26.49''E; 342 m asl) is in sandy terrain covered by forest. Rescue excavations at this site started in 2001 in order to prevent its destruction by continuous illegal excavations (Niezabitowska Reference Niezabitowska2005; Niezabitowska-Wiśniewska Reference Niezabitowska-Wiśniewska2009). Vestiges of different cultural units were identified at this site. The oldest material was dated to the Late Palaeolithic. Other objects represented different cultures from the Mesolithic and Neolithic to the Middle Ages.

Figure 1 Location of archaeological site 3 in Ulów in the Roztocze region, southeastern Poland.

Archaeological Investigations

The excavated area of site 3 in Ulów covers 2236.70 m2. The archaeological features can be grouped into four main types based on their function and cultural units (Figure 2, Table 1). Type 1 includes features related to the graves of barrows of the Corded Ware culture, a Late Neolithic culture that developed in the 3rd millennium BC (Figure 2) (Włodarczak Reference Włodarczak2009; Niezabitowska-Wiśniewska and Wiśniewski Reference Niezabitowska-Wiśniewska and Wiśniewski2011). Within this type, Type 1A is distinguished, describing pits dug into the barrow mounds, which are signs of subsequent looting.

Figure 2 Distribution of anthropogenic features in excavation units at site 3 in Ulów, with photos of examples of different types of archaeological features.

Table 1 Radiocarbon dating of charcoal samples from site 3 in Ulów.

Type 2 includes features associated with the Wielbark culture. This culture is traditionally related to the Goths, who during the Late Roman and the Early Migration periods (3rd–5th c. AD) inhabited southeastern Poland. This type is represented mainly by cremation graves, which usually contained rich offerings including metal, pottery, and glass artifacts. We dated most of these objects to phase C3/D1 of the Roman period, corresponding to ages between 360/370 and 430 AD (Tejral Reference Tejral1988; Godłowski Reference Godłowski1992). The graves were scattered in the northern part of the site and were not associated with Late Neolithic barrows (Figure 2). The function of other archaeological features (Type 2A) in which material of the Wielbark culture occurred is more difficult to interpret. Hearth remains with pavement were also found (Type 2B).

The remaining archaeological features usually did not contain any material usable for age estimation by relative chronology, or else their material was of mixed chronology. Type 3 includes three groups of post-holes forming rectangular structures (4.0 × 3.5 m, 4.4×3.8 m, 1.8×1.7–1.8 m). Type 4 includes large fragments of burnt wood (Figure 2). Type 4A consists of conspicuously large, deep, rectangular structures.

The aim of this study was to establish the absolute chronology of the graves of the Corded Ware and Wielbark cultures (Types 1 and 2), and the absolute chronology of the features that lacked well-dated archaeological material (Types 3 and 4).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Wood charcoal fragments were the only botanical material found at site 3 in Ulów. Anthracological analysis can help identify the different uses of wood during funeral ceremonies (Moskal-del Hoyo Reference Moskal-del Hoyo2012). The charcoals came from hand-picked samples recovered during excavation work in 2001-2010. A given grave or feature yielded 1–9 samples. There were only a few charcoals in Corded Ware culture graves (Type 1). More than 1150 charcoal fragments were taxonomically identified to 14 taxa. For radiocarbon (14C) dating, 43 charcoal fragments (Table 2) from different types of features were chosen: 1 from Type 1, 2 from Type 1A, 13 from Type 2, 2 from Type 2A, 2 from Type 2B, 13 from Type 3, and 10 from Type 4.

Charcoal fragments were identified taxonomically by standard methods used in anthracology (e.g. Moskal-del Hoyo Reference Moskal-del Hoyo2012). Branches or twigs were selected, based on ring curvature (Marguerie and Hunot Reference Marguerie and Hunot2007). This material, young wood, is better suited for 14C dating (Moskal-del Hoyo and Kozłowski Reference Moskal-del Hoyo and Kozłowski2009).

The taxonomically identified charcoal fragments were selected for 14C dating. Since many samples contained large fragments of burnt wood, they were first sorted for liquid scintillation counting (LSC). This conventional 14C analysis was performed in the Laboratory of Absolute Dating in Kraków (Poland). Samples were chemically pretreated with AAA (acid-alkali-acid). The procedure included standard synthesis of benzene from the samples (Skripkin and Kovalyukh Reference Skripkin and Kovalyukh1994). 14C measurements were carried out using a HIDEX 300SL triple photomultiplier liquid spectrometer (Krąpiec and Walanus Reference Krąpiec and Walanus2011). AMS 14C measurements were performed in the Radiocarbon Laboratory in Poznań (see Goslar et al. Reference Goslar, Czernik and Goslar2004 for details). Calibrated 14C ages (cal AD/BC) were obtained based on the IntCal13 14C calibration dataset (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013) and OxCal 4.2 calibration software (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Based on the 14C dating results, three main chronological horizons were distinguished (Figures 3–5) and divided into subgroups (Table 1).

Figure 3 Distribution of 14C dating results of samples (numbers as in Table 1) in excavation units at site 3 in Ulów. Horizons 0–III.

Figure 4 14C dating results of samples from Late Neolithic archaeological features (Horizon I). The model applied yields a calculation of the probability distribution pattern for the calendar-age beginning, end, and possible time span of the phase.

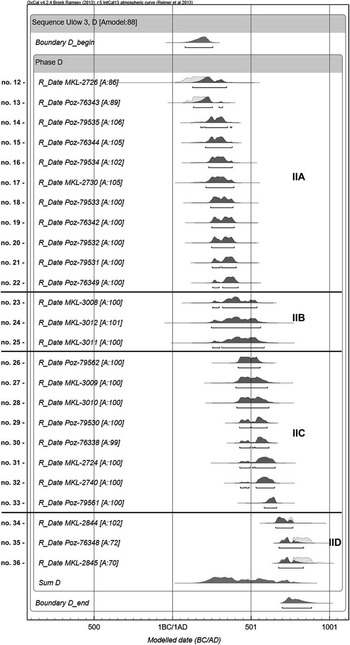

Figure 5 Model showing the probability distribution pattern for samples of Horizon II, originating during the first millennium AD.

Horizon I is represented by Late Neolithic features of the Corded Ware culture (Figure 3) and archaeological features of Types 1 and 4A. Only one barrow grave (Type 1) contained charcoals, from which one fragment of ash Fraxinus excelsior was dated. The result (ca. 2620–2490 BC, 68.2% probability, Table 1, no. 10) was in accordance with the relative chronology of the Ulów barrows, which were initially interpreted to be of the younger phase of the Corded Ware culture (Niezabitowska-Wiśniewska and Wiśniewski Reference Niezabitowska-Wiśniewska and Wiśniewski2011). All of the Type 4A (Table 1, no. 3–5, 7–9, 11) features also proved to be Late Neolithic. Taxonomical analysis of charcoal fragments from those features showed that only oak Quercus sp. wood was used. Such features, which are situated between barrows, have no exact analogues in other Corded Ware sites in Poland, but we should point out that only areas adjacent to barrows have usually been excavated; vast areas rather farther from the barrows generally are not investigated. In the light of these results, the presence of Corded Ware pottery scattered in the vicinity of the remains of those wooden structures may indicate the past practice of unknown, more complicated rites associated with the Late Neolithic cemetery. Occasionally, features with remains of burnt and cremated bones have also been found under and outside barrows (Machnik Reference Machnik1966; Włodarczak Reference Włodarczak2006).

The time interval represented by the Late Neolithic features of the Corded Ware culture was established from a model enabling calculation of the probability distribution for the beginning, end, and possible time span of the phase in calendar age (Figure 4). The model indicates that the analyzed objects may represent a broad chronological range from the beginning of the fourth millennium until the middle of the third millennium (Figure 4).

The relationship between the barrows (Type 1) and the wooden structures (Type 4A) requires more study. Although the 14C dating from barrow I indicates a period later than that of the wooden structures, other barrows from the nearest area, such as barrow II of site 4 in Ulów, showed a chronology of around 3000–2800 BC (Niezabitowska-Wiśniewska, unpublished). The differences in chronology may also be related to the use of wood obtained from oak, which is a genus of long-lived trees that may give a date older than the moment of its use by humans (the “old wood” problem; Schiffer Reference Schiffer1986). This applies especially to timber remains.

In southeastern Poland, the development of the Corded Ware culture began between 2800 and 2700 BC, and the final stage occurred around 2300 BC (Jarosz and Włodarczak Reference Jarosz and Włodarczak2007). Its age estimation may be more complicated, however, as for this period two plateaus of the calibration curve appear, at 2880–2580 and 2470–2200 BC (Włodarczak Reference Włodarczak2009). In this context and in the light of new 14C dates from the Lublin Upland (Włodarczak Reference Włodarczak2016), it might be also assumed that the dating results of oak timber might reflect the “old wood” problem.

One dating result came from a typical cremation grave of the Wielbark culture (Type 2) with cremated bones and rich offerings (grave 40, Table 1, no. 6). The presence of charcoal dated to the Late Neolithic suggests that post-depositional processes were responsible for the admixture of anthracological material, attributable to the location of this grave in an area of Late Neolithic features with a great amount of burnt wood (Type 4A) (Figure 3).

Horizon II (Types 2–4) is associated with cultures that developed during the first millennium AD. It can be divided into four subgroups (Table 1, IIA–IID). Horizons IIA and IIB correspond to the Wielbark culture. Five graves (Type 2), one feature with pavement (Type 2B) and five features of Type 3 belong to Horizon IIA (Table 1, no. 12–22). According to the relative chronology they represent the Late Roman period, falling between the 3rd and 4th centuries AD. Figure 5 presents the probability distribution pattern produced from a model taking into account all dating results. Feature 32K (Table 1, no. 12) and grave 14 (Table 1, no. 13) gave the oldest dating results, correlated with the period between the end of the 1st century AD and the beginning of the 3rd century AD. This seems slightly too early for the presence of the Goth culture in southeastern Poland, as Goths appeared in the Lublin Upland no earlier than at the end of the 2nd century AD (Kokowski Reference Kokowski1991, Reference Kokowski2010, Reference Kokowski2013). However, these two dating results are in accord with the relative chronology, as the main and highest peak falls at the beginning of the 3rd century AD (Figure 5), which corresponds to the presence of the Wielbark culture in the Lublin region. The majority of the dating results from other graves and features can be placed in the second half of the 3rd century and the 4th century AD. The result from grave 84 (Table 1, no. 22), which gave the youngest date of this horizon, correlates well with the relative chronology, as this grave was initially dated to the C3/D1 phase and the dating result points to 335–400 AD (68.2% probability).

Horizon IIB is represented by three dating results, which indicate the Late Roman and Migration periods (4th–5th c. AD) (Table 1, Figure 5). The data from feature 20K (Table 1, no. 24, Type 3) and grave 42A (Table 1, no. 25, Type 2), which are near each other (Figure 3), are similar. It is important to note that feature 72 with stone pavement (Table 1, no. 23, Type 2B) is similar to feature 99 (Table 1, no. 17, Type 2B) of Horizon IIA, which was used by people of the Wielbark culture. These kinds of features are known from other cemeteries of the Wielbark culture and can be interpreted as fireplaces related to funeral rites (Chowaniec Reference Chowaniec2005; Gałęzowska Reference Gałęzowska2007).

Horizon IIC represents the Migration period and the Early Middle Ages according to the relative chronology, corresponding to the 5th and 6th centuries and the beginning of the 7th century AD (Table 1, Figure 5). All of the 14C measurements come from features (Table 1, no. 26–33, Types 3 and 4). 14C dating of feature 68/10 dug into barrow II (Table 1, no. 30, Type 1A) confirmed that this feature is evidence of later looting of the Neolithic graves in the barrow. From this feature a charcoal of hornbeam Carpinus betulus was selected for dating, because this tree is late arrival in the region (Bałaga Reference Bałaga1998; Korzeń et al. Reference Korzeń, Margielewski and Nalepka2015) and its presence in a late Neolithic grave was doubtful. The function of features of Type 4 with a large accumulation of pine wood (Table 1, no. 26, Type 4) is still difficult to interpret.

Six dating results came from features of Type 3 (Figure 3, Table 1, no. 27–29, 31–33) which suggest that at least two rectangular structures were built during this period, evidenced by groups of post-holes. As described previously, six charcoal samples from features of Type 3 were also dated to Horizons IIA and IIB (Table 1, no. 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 24). Based on the dating results as well as the dominance of objects belonging to the Wielbark culture mixed with a few small cremated bones and charcoals, it is likely that the “older” charcoals represent burial remains and a cremation layer from the surface of the cemetery of the Wielbark culture, on which a structure with post-built walls was built later. During this construction work, charcoals from different chronological and cultural units would have been mixed together. If so, it has implications for our interpretation of cultural processes in the late stage of the Migration period and Early Middle Ages: it was thought that these lands had been uninhabited, and this leaves an open question. Who settled there between the end of the 5th century and the beginning of the 7th century AD? Did Goths of the Wielbark culture remain in this area? Did a new unknown tribe of Late Germanic people appear? Infrequent material typical of the latter group was found at the site. It is unlikely that these buildings were made by the first Slavic people, who usually did not build such things (Parczewski Reference Parczewski1988, Reference Parczewski1993; Godłowski Reference Godłowski2000; Bemmann and Parczewski Reference Bemmann and Parczewski2005). In addition, the palynological analyses performed so far near the Ulów site 3 (Pidek, unpublished) have not helped in detecting the existence of the inhabitance during the Migration Period due to the lack of pollen zones dated to this period.

Horizon IID corresponds to the Early Middle Ages (7th–8th c. AD, Figure 5). This horizon was represented by charcoals found in three features of Types 3 and 4 (Table 1, no. 34–36). Since they did not belong to the Corded Ware culture or to the Wielbark culture, it is very difficult to interpret their function and to connect them to a particular culture, but from this period some single finds of Slavic tribes were found at Ulów.

Seven charcoals were dated to Horizon III of the Middle Ages (second half of 14th c. to first half of 15th c. AD) (Table 1, Figures 3 and 6). Feature 68A/11 (Table 1, no. 37, Type 1A) again apparently comes from a looting pit. Two dated charcoals from different areas of feature 69 (Table 1, no. 40–41) gave very similar results placing them in the first half of the 15th century AD. This feature contained artifacts characteristic of the Wielbark culture, including a wheel-made vessel, so the charcoal remains likely indicate later disturbance of feature 69. The situation is similar for graves 2, 25, and 68 (Table 1, no. 38–39, 42–43). They most likely were Wielbark culture burials, as many remains of cremated bones and rich offerings typical for this cultural unit were documented. The presence of charcoals dated to the Middle Ages shows that post-depositional processes caused the admixture of anthracological material. The existence of a settlement at Ulów during the Middle Ages was not confirmed, but the sporadic presence of humans is inferred from single archaeological findings.

Figure 6 Model showing the probability distribution pattern of samples from the Middle Ages.

Finally, two charcoals of Scots pine Pinus sylvestris from two Wielbark culture graves (Type 2) turned out to be of early Holocene origin (Horizon 0A and 0B). These results are not surprising, as both graves had an admixture of lithic material dated by typological analysis to the Late Palaeolithic and Mesolithic. The manner in which the graves were made could not be determined; probably they were dug into older cultural layers. These graves are on the southern edge of the Wielbark culture cemetery, away from the main concentration of graves. Their material may have moved from the original burials or from the cremation layer (Figure 3).

In view of these results, we can suggest some general trends in the use of wood, probably related to its availability in different periods of local development of the vegetation cover in the Holocene (Bałaga Reference Bałaga1998; Korzeń et al. Reference Korzeń, Margielewski and Nalepka2015). For example, only oak wood was used in the Neolithic structures that left remains of large beams (Type 4A), indicating a preference for oak timber. Its mechanical properties make oak an excellent construction material, as previously confirmed in work on numerous archaeological sites (Zielski and Krąpiec Reference Zielski and Krąpiec2004). Different kinds of wood were found in Wielbark culture graves from Horizons I and II, but birch Betula sp. and pine Pinus sylvestris were ubiquitous and most frequent. These trees have shown frequent occurrence in other incineration cemeteries of the Roman period (Sławiński et al. Reference Sławiński, Gierasimow and Kościk1958; Czeczuga and Kłyszejko Reference Czeczuga and Kłyszejko1974; Moskal-del Hoyo Reference Moskal-del Hoyo2012). Birch in particular could have been chosen due to the ignition properties of its bark, which contains betulin, a chemical compound which rapidly ignites even fresh and wet wood; it also allows birch wood to reach higher temperatures during burning (Lityńska-Zając et al. Reference Lityńska-Zając, Wasylikowa, Cywa, Tomczyńska, Madeyska, Koziarska and Skawińska-Wieser2014). In two hearths with pavement, from the same culture, only oak wood was documented. Among the features dated to Horizon III late-arriving trees such as fir Abies alba and beech Fagus sylvatica prevailed. These findings have implications for selection of charcoals for 14C dating. Anthracological analysis may prove helpful in choosing the best charcoal samples to use for 14C dating of particular cultural units, and it may also help in elucidating problems of taphonomy when a given taxon does not fit the taxonomic list of the whole charcoal assemblage characteristic for a specific culture. At a multicultural site such as the one reported here, which shows clear evidence of mixing of material, only charcoal fragments analyzed by 14C unquestionably belong to particular archaeological features.

CONCLUSIONS

Radiocarbon dating of charcoals sampled from different types of archaeological features confirmed and clarified the chronology of cemeteries that originated during the periods of the Corded Ware and Wielbark cultures at site 3 in Ulów. A group of features with burnt wooden structures and with a small amount of archaeological material (Type 4A) were demonstrated to be of Late Neolithic origin. The 14C datings confirmed the occurrence of multiple post-depositional processes leading to the formation of disturbed layers of archaeological features. For example, there was a discrepancy between the chronology of archaeologically well-dated artifacts from grave contexts (Type 2) and the 14C dates of charcoal samples. The results also indicated that the barrow dated to the Corded Ware culture was looted in later periods. 14C dating also revealed much greater intensity of settlement during the early and late stages of the Middle Ages, previously not inferred from a few earlier findings. These dating results also suggest that there probably was no hiatus in this area between the late Wielbark culture and the first Slavic groups; this is unusual in Polish prehistory.

For multicultural sites like site 3 in Ulów, a large sequence of 14C datings is essential for proper determination of the age of different archaeological features. A full archaeological reconstruction of the different phases of multicultural settlements requires the use of complementary methods in the framework of an interdisciplinary research program.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Science Centre in Poland (DEC–2013/09/B/HS3/03352) and by statutory funds of the W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences. Michael Jacobs line-edited the text.