INTRODUCTION

Egyptian necropolises have provided millions of animal mummies, reflecting the ancient Egyptian’s heartfelt belief in the efficacy of animal cults, and demonstrating the significant place that these cults occupied in Egyptian religious practice from the 7th century BC through the Roman period (~AD 300) (e.g. Kessler Reference Kessler1986; Charron Reference Charron1996; Vernus and Yoyotte Reference Vernus and Yoyotte2005; von den Driesch et al. Reference von den Driesch, Kessler, Steinmann, Berteaux and Peters2005; Ikram Reference Ikram2015a). For the ancient Egyptians, each god had at least one totemic animal, and it was thought that part of the divine spirit of any particular god could enter the body of its totemic animal, which could be recognized by distinctive markings. During its lifetime, that animal would be worshipped as a god, and upon its death it would be mummified and buried with all that was due to a divinity—one might liken this to the way in which the Dalai Lama is conceived of and chosen (Kessler Reference Kessler1986; Ray Reference Ray2001; Ikram and Iskander Reference Ikram and Iskander2002; Ikram Reference Ikram2015a). In addition, many animal mummies exist in the form of votive offerings (Charron Reference Charron1990; Ikram and Iskander Reference Ikram and Iskander2002; Ikram Reference Ikram2015a, Reference Ikram2015b). These were creatures that were sacrificed and offered to a particular deity in the hopes that the dedicants’ prayers might be answered, and are akin to the practice of lighting a candle in a church, although more permanent and more bloody. This practice has created a significant group of animal mummies. Within the group of votive mummies lies a subgroup: ancient falsified mummies. These consist of fragments of animals (feathers, fur, bits of bone) or even mud, wrapped to look like a mummy of whichever animal was offered in that catacomb. These mummies have been variously interpreted as sacred relics from animals that were gathered up and wrapped and offered as an act of piety, the idea that a part of a creature can symbolize the whole, or they were the result of laziness on the part of the priests, or a deliberate defrauding of pilgrims (Kessler Reference Kessler1986, Reference Kessler1989; Ray Reference Ray2001; Ikram and Iskander Reference Ikram and Iskander2002; Ikram Reference Ikram2015a). The number of mummies that were generated due to this intense religious belief influenced Egypt’s economy, religious beliefs, and feelings of nationalism throughout the final phases of Egyptian civilization (Ikram Reference Ikram2015a, Reference Ikram2015b). Despite the popularity of these cults and the massive numbers of animal mummies that have been found, the chronological range of the popularity of animal cults is still not fully understood, with vague dates being assigned to this practice.

The multidisciplinary research project MAHES (French acronym for Egyptian Mummies of Animals and Humans) has been established by the University of Montpellier and in particular, the CNRS Laboratory Archaeology of Mediterranean Societies (Charron et al. Reference Charron, Porcier, Ikram, Pasquali, Lichtenberg, Mérigeaud, Tafforeau, Richardin, Vieillescazes, Piques, Letellier-Willemin, Bailleul-LeSuer and Servajean2015; Porcier et al. Reference Porcier, Charron, Ikram, Pasquali, Lichtenberg, Mérigeaud, Tafforeau, Richardin, Vieillescazes, Piques, Letellier-Willemin, Bailleul-LeSuer and Servajean2015), which is working on holistically studying a large collection of animal mummies held in the Musée des Confluences at Lyon, in order to understand the history and culture of ancient Egypt, religious beliefs, the chronology of this practice, the geographic distribution of these cults, and their socioeconomic role in ancient Egyptian society.

Researchers have the opportunity to make use of the collection of animal mummies of the Confluences Museum in Lyon (France), the largest group in the world outside of Egypt. This exceptional collection, comprising 2500 specimens, includes a wide range of mummified animals dating to a broad time period, from the New Kingdom until the first centuries of our era (Porcier and Berthet Reference Porcier and Berthet2014). The majority of these mummified remains was studied at the beginning of the 20th century by Dr. Louis Lortet, director of the Natural History Museum of Lyon, and the naturalist Claude Gaillard (Lortet and Gaillard Reference Lortet and Gaillard1903, Reference Lortet and Gaillard1907, Reference Lortet and Gaillard1909). These works remain essential references for research on the fauna of ancient Egypt (Nicolotti and Postel Reference Nicolotti and Postel1994). However, although fundamental, these publications are now outdated in many respects (only the external appearance of the wrapped mummies was investigated, outdated nomenclatures, appropriate research to that time, but not to current standards) and they mostly ignore any archaeological data: the places and contexts of excavations, as well as the religious character of the mummies.

Generally, scholars have ascribed the apogee of animal mummies to a long period of time spanning about 680 BC until AD 350 (Smelik and Hemelrijk Reference Smelik and Hemelrijk1984; Kessler Reference Kessler1986, Reference Kessler1989; Ray Reference Ray2001; Ikram Reference Ikram2015a). However, increasingly there is an idea that the dating of activities related to these cults can be better defined and that these nuances will reveal more about the Late and Greco-Roman period (7th century BC to the 4th century AD) history, culture, and economy of ancient Egypt’s history, culture, and economy during the Late and Greco-Roman periods (7th century BC to the 4th century AD) (Ikram Reference Ikram2015a, Reference Ikram2015b; Wasef et al. Reference Wasef, Wood, El Merghani, Ikram, Curtis, Holland, Willerslev, Millar and Lambert2015).

Thus, 63 samples from mummies and their wrappings, from the Musée des Confluences’ collection, were examined using 14C, in order to establish a chronological framework for animal cult activities in Egypt. Specimens were taken from different species of mummies (cattle, rams, gazelles, cats, dogs, foxes, shrews, baboons, ibis, crocodiles, fish, etc.), in order to establish a basis of dates for such cultic activity (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Photographs of six mummies of the Confluences Museum, showing the diversity of animal species and mummification techniques: (a) Nile perch mummy, Inv 90001178 (© Département du Rhône, Patrick Ageneau); (b) ram skeleton, Inv 90001215 (© Département du Rhône); (c) shrew mummies bundle, Inv 90001224, this wrapped bundle contains many mummified shrews (© Département du Rhône); (d) head of mummified calf, Inv 90001213 (© Département du Rhône, Patrick Ageneau); (e) Nile goose mummy, Inv 90001198 (© Département du Rhône); (f) gazelle mummy, Inv 90001623 (© Projet MAHES, Stéphanie Porcier).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling

A total of 63 samples were collected from selected mummies stored at the Musée des Confluences. Only mummies that were damaged in some way were sampled in order not to compromise the integrity of museum objects. A variety of species were chosen in order to see if there were chronological differences in the popularity of specific animals or cults. Between 10 and 30 mg of textile or 200 and 500 mg of bone were sampled with small pliers or very small scissors, taking care to sterilize the tools and to avoid contamination. It should be noted that using textiles to date mummies is slightly problematic in that mummy bandages often consist of reused textiles, and thus the fabric might be older—up to as much as 50 yr or possibly more—than the mummy (Letellier-Willemin et al. Reference Letellier-Willemin2015a, Reference Letellier-Willemin2015b; Wasef et al. Reference Wasef, Wood, El Merghani, Ikram, Curtis, Holland, Willerslev, Millar and Lambert2015).

The mummies themselves had been collected in the 19th century by L Lortet and C Gaillard (1903, 1907, 1909) from a variety of sites, most of which were dated in a general way to the Late Period to Roman era, with more specific dates assigned based on ceramic evidence (Berthet Reference Berthet2016). Had it not been for these scholars, most of these mummies would have been looted, burned as fuel, or used as fertilizer (Ikram and Dodson Reference Ikram and Dodson1998). Unfortunately, despite the fact that Lortet and Gaillard kept fairly good notes for the time, some of the samples do not have specific cemeteries associated with them, although educated guesses can be made as to their origin based on our knowledge of the collection process and history as outlined by Lortet and Gaillard (Reference Lortet and Gaillard1903, Reference Lortet and Gaillard1907, Reference Lortet and Gaillard1909).

Sample Preparation

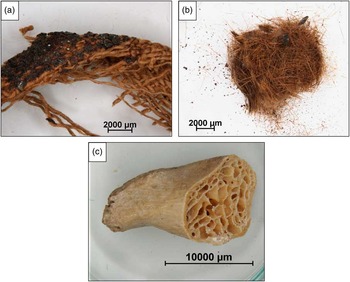

The varied nature of collected samples, which included biological tissues (hair, bones, cartilage, and horn) or vegetal materials (in the form of linen textiles) required the establishment of a special sample preparation protocols due to the presence of high quantities of exogenic organic compounds such as bodily fluids, mummification balms, grease, fats, and oils (Figure 2). These complex mixtures, if they are not correctly eliminated, could give false dates (older or younger) for the objects (Quiles et al. Reference Quiles, Delqué-Količ, Bellot-Gurlet, Comby-Zerbino, Ménager, Paris, Souprayen, Vieillescazes, Andreu-Lanoë and Madrigal2014; Wasef et al. Reference Wasef, Wood, El Merghani, Ikram, Curtis, Holland, Willerslev, Millar and Lambert2015).

Figure 2 Macrophotographs of three samples from animal mummies of the Confluences Museum: (a) textile sample from an ibis mummy (Inv 90002478); (b) hair sample from a shrew mummy (Inv 90001273A); (c) bone sample from a goat mummy (Inv 51000070) (©C2RMF, Gaëtan Louarn).

Cleaning and Solvent Extraction

In order to eliminate all sources of organic contaminations, samples were submitted with a protocol established for museum objects (Richardin and Gandolfo Reference Richardin and Gandolfo2013a, Reference Richardin and Gandolfo2013b; Richardin et al. 2013). Samples were first washed with ultrapure water (Direct-Q system from Millipore), then with a mixture of methanol/dichloromethane (v/v 1/1) (for analysis, VWR International), and finally with acetone (AnalaR Normapur, VWR International) in an ultrasonic bath for 10–15 min. After the last treatment, samples were thoroughly rinsed three times with ultrapure water.

Textiles, Hair, and Wool Samples Preparation

Textiles, hair, and wool samples were treated with the classic AAA method (Richardin et al. Reference Richardin, Gandolfo, Moignard, Lavier, Moreau and Cottereau2010a, Reference Richardin, Cuisance, Buisson, Asensi-Amoros and Lavier2010b). This consisted of a series of washes at 80°C for 1 hr with a 0.5N hydrochloric acid solution (HCl, VWR International), then with a 0.01N sodium hydroxide aqueous solution (NaOH, VWR International), and once again with the 0.5N HCl solution. Before each treatment, the supernatant was removed and the remaining fragments rinsed with water until neutrality of the washing waters was achieved. Finally, the cleaned samples were dried overnight under low vacuum (100 mbar) at 5°C.

Extraction of Collagen from Bones

Collagen from bones, when preserved, is the most reliable source for 14C dating. The extraction of soluble collagen used was based on the method described by Longin (Reference Longin1971). A 2N hydrochloric acid (HCl, VWR International) treatment is used to solubilize the mineral fraction, in a cold ice bath for 30–60 min. The solution was diluted with water, and then allowed to stand at 4°C for 4–5 hr. After centrifugation, acid was removed, the solid was washed with ultrapure water to pH 4–5, and left at 4°C overnight. Further washings are performed until the sample is neutral. The second step is a basic treatment with a 0.1N sodium hydroxide solution (NaOH,VWR International) in an ice bath for 1 hr, followed by further rinses until neutrality is achieved. A further acid treatment with the 2N HCl solution is performed in an ice bath for 1 hr, followed by rinsing to pH 3. Then, hydrolysis is carried out at 9°C overnight. The obtained solution is filtered on quartz-fiber filter. Finally, the filtrate is dried by lyophilization.

Combustion and Graphitization

The dried organic fraction is then combusted 5 hr at 850°C under high vacuum (10–6 Torr). Next, 2 to 2.5 mg of pretreated sample are combusted in a quartz tube with 500 mg CuO [Cu(II)oxide on Cu(I) oxide heart for analysis, VWR International] and Ag wire (99.95%, Aldrich). The combustion gas is separated by cryogenic purification and the CO2 is collected in a sealed tube. The graphitization is achieved by direct catalytic reduction of the CO2 with hydrogen, using Fe powder at 600°C and an excess of H2. During the process, the carbon is deposited on the iron and the powder is pressed into a flat pellet.

Radiocarbon Measurements and Calibration

All measurements were performed at the Artemis AMS facility of Saclay, France (Moreau et al. Reference Moreau, Caffy, Comby, Delqué-Količ, Dumoulin, Hain, Quiles, Setti, Souprayen, Thellier and Vincent2013). 14C ages were calculated with correcting the isotope fractionation δ13C, calculated from accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) measurements of the 13C/12C ratio. Calendar ages were determined using OxCal v 4.2 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) and the most recent calibration curve data for the Northern Hemisphere, IntCal13 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). Calibrated age ranges correspond to 95.4% probability (2σ).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The 14C ages and calibrated age ranges of samples are given in Table 1, and almost all date to the Ptolemaic era (~323–30 BC), although some mummies are much earlier, and a few are later. The first point of discussion concerns the wide range of dates obtained for the mummies: between 3180±30 BP [1506–1407 cal BC] for a single specimen, that of a Nile goose (Inv 90001198), and 1800±30 BP [130–326 cal AD] for a gazelle mummy (Inv 90001291), a range of more than 2000 yr (Figure 3). These results correspond to dates starting in the New Kingdom (~1539–1077 BC) and continuing until the Roman period (~30 BC–AD 391). As noted above, on the basis of texts and ceramic evidence, animal cults are thought to have started flourishing in the Late Period (starting in ~664 BC), and continuing through the Roman period, ending with the establishment of Christianity as the state religion in Egypt.

Figure 3 Range of calibrated 14C dates for all animal species

Table 1 14C age and calibrated age of all samples.

Though the gazelle mummy fits into this timespan, as do all the other mummies studied, the goose is much earlier. It is possible that the mummy type is neither sacred nor votive, but that of a pet or, more likely, falling into the category of “other” (Ikram Reference Ikram2015a). A limited corpus of pet mummies are known from ancient Egypt (Ikram and Iskander Reference Ikram and Iskander2002; Ikram Reference Ikram2015a). Although geese do not number among these examples, images and references to pet birds (including ducks and geese) are recorded (Houlihan Reference Houlihan1996; Vernus and Yoyotte Reference Vernus and Yoyotte2005), and it is possible that this goose is such a creature. However, as the bird was part of a foundation deposit of the Memorial Temple of Thutmoses III (~1481–1425 BC) at Thebes (Lortet and Gaillard Reference Lortet and Gaillard1909: 155), it is more likely that it was a special kind of sacrifice, thus far unique in foundation deposits (Weinstein Reference Weinstein1973). Of course, it is also possible, although unlikely for this well-provenanced object whose 14C dates fall within Thutmosis’ reign, that the linen was far older than the bird, and this is an early example of recycling. As noted above, using textiles to date the mummies could potentially be an issue (Letellier-Willemin et al. Reference Letellier-Willemin2015a, Reference Letellier-Willemin2015b; Wasef et al. Reference Wasef, Wood, El Merghani, Ikram, Curtis, Holland, Willerslev, Millar and Lambert2015). Nonetheless, it does seem that, on the whole, whether bones or textiles were sampled, the date range of the samples is similar, regardless of the site (e.g. specimens 51000043, 90002317, and 90001211), suggesting that for large-scale industrial-type burials of animals, there was a quick turnover in embalming materials, including mummy bandages.

The spectrum of dates gathered from the different animals may suggest changes in the popularity of different gods and their associated animals, or points during which particular cults in specific locations flourished. Sacred Ibis mummies (Threskionis aethiopicus; 13 samples) are dated to between 2390±30 and 2010±30 BP, from just before the “official” date assigned to the start of the Late Period, and continuing to the beginning of the Roman period. This range fits in very well with the whole span of time during which animal mummies were popular, and it should be noted that ibis burials were associated with Thot, the god of learning and divine justice, and the focus of one of the most widespread and enduring of Egyptian cults. Although this range is wider than that found by other studies on ibises, albeit ones that had far fewer specimens (Wasef et al. Reference Wasef, Wood, El Merghani, Ikram, Curtis, Holland, Willerslev, Millar and Lambert2015), the majority of our ibises also fall within the Ptolemaic to Roman (~332 BC–AD 391) timeframe, the same period as for the other specimens (Wasef et al. Reference Wasef, Wood, El Merghani, Ikram, Curtis, Holland, Willerslev, Millar and Lambert2015). Further analyses of ibis mummies from diverse locations should help to more precisely document the rise and fall of the cult of Thot.

Some trends have emerged from this study, such as the earlier presence of shrew and cattle mummies at Asyut compared to canine mummies. Canines were associated with the city gods: Anubis and, more significant, Wepwawet; one should bear in mind that for the Egyptians the phenotype was the basis of classifications for animals; thus, foxes would fall within canine types for the Egyptians (Houlihan Reference Houlihan1996; Charron Reference Charron2011). Shrews and cattle were both associated with the sun god Re, with the former being the nocturnal manifestation of that god (Brunner-Traut Reference Brunner-Traut1965; Ikram Reference Ikram2005) and bulls being associated with him from the earliest times (Dodson Reference Dodson2015). Canines are associated with Wepwawet/Anubis, god of travel and embalming, and long revered in Asyut (Charron Reference Charron2011; Ikram Reference Ikram2013). Thus, it is somewhat surprising that animals associated with the sun cult should antedate those associated with the deity of the city. Either our findings indicate that the practice of animal mummification started with the sun god, the main god of Egypt, and then extended to other divinities, or indicate that our understanding of the importance of Wepwawet/Anubis at Asyut is flawed. If the former, this will mean a re-examination of scholarly understanding of the foundation and evolution of animal cults. This conundrum can only be clarified by further analyses of samples of different types of animal mummies from Asyut, but already, the dating has opened new avenues of inquiry.

Analyses of additional samples might clarify the situation in terms of tracking the geographical popularity of the cult: quite possibly the vogue for a particular cult rose and fell. According to our study, monkey and goat mummies fall into a range of dates similar to the ibises, dating from the Late Period and into the Ptolemaic period. The cattle sampled from three necropolises (Saqqara, Asyut, and Thebes), however, seem to be slightly later in date, while the small mammal mummies (shrews, dogs, foxes, and cats), fish, and reptiles seem to span the entire time period during which animal cults flourished.

However, the Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia) and gazelle (Gazella spp.) date exclusively to the Roman period (Inv 51000065 is 1965±30 BP, which corresponds to around 40 cal BC–cal AD 85, and Inv 90001291, 1800±30 BP, or cal AD 130–330), and are found in diverse sites, from Giza to Kom Ombo. These results suggests the rise of certain cults during this time or changes in how particular gods were revered. This might indicate the rise of a new cult or the renaissance of an old one, possibly associated with the goddess Anukis, daughter of Re, who was part of the Elephantine island triad of divinities (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2003: 138) and associated with gazelles. The discovery of gazelle mummies might provide evidence for her cult being celebrated in the Memphite region. Perhaps there was some association with the Roman goddess Diana, mistress of the hunt, as well. Alternatively, gazelles were associated with Reshep, a Near Eastern divinity who was incorporated into the Egyptian pantheon in the New Kingdom, and who might have enjoyed a renaissance in the Roman era, perhaps due to an increased international population (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2003: 126). In any case, the presence of these mummies provides an interesting insight into changing religious beliefs in terms of new cults, resurgence of old ones, or a change in how gods were revered, and which are possibly associated with the advent of the Romans.

It would thus seem that many animals that were readily available (notably ibis, cattle, ovicaprines, dogs, and shrews) were mummified throughout the timespan when animal cults were active. Monkeys are documented from the Late Period into the mid-Ptolemaic period, but not before, unless as pets (at present). However, the clustering of dates for all creatures, in the late 3rd to the 1st centuries BC, might indicate that this was the apogee of this form of worship, which started to decrease during the 1st century AD, dying out slowly, except in certain places and with certain animals (cattle and crocodiles, to name but two) by the late 3rd century AD. This is a change from the earlier idea that the phenomenon was most popular in the 5th and 6th centuries BC.

Also, it is possible that issues of economy and trade can be better understood by the dating of animal mummies. For instance, the (admittedly few) examples of baboon mummies date to the Late Period and the Ptolemaic era, perhaps indicative of a flourishing trade in exotic animals between Egypt and sub-Saharan Africa during this time. The possible absence of such animals being available for mummification in the Roman period might indicate Egypt’s waning power and Rome’s ascendancy, as animals that previously would have been brought to Egypt and kept there were now being sent on to Rome as animals kept as pets, in zoos, or in circuses.

CONCLUSION

The dates reported here (Table 1) represent the first chronological results obtained from the Musée des Confluences in Lyon’s collection of animal mummies. For the first time ever, a large-scale research project (MAHES) has launched an extensive program of 14C dating of animal mummies of diverse species coming from all over Egypt. The 14C dating has confirmed the textual and ceramic dates that indicate that animal mummification became popular from the 7th century BC and continued into the Roman era, and refined on these cult practices in terms of documenting the changing popularity of certain cults.

Although this work represents only a selection of the Museum’s collection, we already have been able to identify broad trends in the history of animal cults. A considerable range of species, including shrews, cats, foxes, dogs, monkeys, cattle, ibises, crocodiles, and fish, were prepared as offerings for a variety of gods during the Late Period, with an apogee reached during the mid-Ptolemaic period, with a tapering off of some species during the Roman period, when an increased popularity in the cults associated with gazelle and Barbary sheep emerged. This raises questions about changes in religious beliefs and changing popularity of different divinities, as well as the economics associated with obtaining different species of animals for mummification, such as monkeys, which are the subject of a new and more detailed research project. Of course, further samples of any particular species might change the picture that has emerged thus far, but the current data serve as a starting point upon which we can build.

More 14C work on the Musée de Confluences collection, as well as on other museum collections of animal mummies and mummies that are being excavated in Egypt, will further flesh out our understanding of the timespan of activity in different necropolises or even specific portions of a particular catacomb. This will enhance our comprehension of economic and sociocultural factors associated with ancient Egyptian animal cults.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors want to thank the staff of the LMC14 (Laboratory of Radiocarbon Measurement) from Saclay (France) for their contribution to the analytical work (graphitization and 14C measurements). The authors also thank the Museum of Confluences in Lyon, the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), ARCHIMEDE Labex project and MAHES project for the partial funding of this project. This project supported by LabEx ARCHIMEDE from the Investissement d’Avenir program ANR-11-LABX-0032-01.