INTRODUCTION

Palaeoenvironmental archives are important resources for providing baseline conditions of past environments and climates (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Gille, Goosse, Abram, Canziani, Charman, Clem, Crosta, De Lavergne, Eisenman, England, Fogt, Frankcombe, Marshall, Masson-Delmotte, Morrison, Orsi, Raphael, Renwick, Schneider, Simpkins, Steig, Stenni, Swingedouw and Vance2016; PAGES2k Consortium 2017; Tardif et al. Reference Tardif, Hakim, Perkins, Horlick, Erb, Emile-Geay, Anderson, Steig and Noone2019). These palaeoenvironmental records are critical for understanding the Earth system beyond short instrumental and observational records. Of vital importance in palaeoenvironmental reconstructions is the ability to develop precise and accurate chronological frameworks, with dating of Late Pleistocene and Holocene deposits typically undertaken by 14C dating. However, 14C dating of sediment sequences can be difficult due to the heterogenous composition of the organic carbon components of sedimentary archives (Lowe and Walker Reference Lowe and Walker2000), incursion from “old” sedimentary carbon (e.g., carbonates, coal beds) and the influence of aquatic carbon sources. In peat and shallow wetland deposits, penetration from roots and rhizomes from plants growing across the surface can have a substantial influence on the 14C ages of different sediment fractions (Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Turney, Hogg, Williams and Fogwill2019). Furthermore, the growth of roots can increase the mobility and vertical movement of humic acids and other particles through a sediment profile (Wüst et al. Reference Wüst, Jacobsen, van der Gaast and Smith2008). Caution is therefore recommended when dating bulk sediment fractions from lacustrine and palustrine systems (Sheppard et al. Reference Sheppard, Ali and Mehringer2020).

Over the past three decades, detailed reconstructions of atmospheric 14C concentrations have been developed (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Heaton, Hua, Palmer, Turney, Southon, Bayliss, Blackwell, Boswijk, Bronk Ramsey, Pearson, Petchey, Reimer, Reimer and Wacker2020; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell, Ramsey, Butzin, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Hajdas, Heaton, Hogg, Hughen, Kromer, Manning, Muscheler, Palmer, Pearson, van der Plicht, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Turney, Wacker, Adolphi, Büntgen, Capano, Fahrni, Fogtmann-Schulz, Friedrich, Köhler, Kudsk, Miyake, Olsen, Reinig, Sakamoto, Sookdeo and Talamo2020). Efforts have been made to 14C date terrestrial plant macrofossils that capture the atmospheric 14C signal, in order to develop precise, calibrated chronologies. Unfortunately, in many environments, few archives are rich in terrestrial plant macrofossils. An alternative approach is the 14C dating of terrestrial microfossils to capture the atmospheric 14C.

In 1989, Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Nelson, Mathewes, Vogel and Southon1989) demonstrated the first use of 14C dating of pollen concentrates by accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS). Since then, several studies have employed 14C dating of pollen concentrates to capture atmospheric 14C concentrations and provide more reliable chronological control than bulk sediment dating (Vandergoes and Prior Reference Vandergoes and Prior2003; Howarth et al. Reference Howarth, Fitzsimons, Jacobsen, Vandergoes and Norris2013; Fletcher et al. Reference Fletcher, Zielhofer, Mischke, Bryant, Xu and Fink2017). However, many studies have highlighted major challenges associated with dating of pollen concentrates, including incomplete removal of non-pollen material, isolation of pollen grains of terrestrial origin, removal of autochthonous components from pollen microstructure (Kilian et al. Reference Kilian, van der Plicht, Van Geel and Goslar2002), obtaining sufficient concentrations of pollen grains from organic matrices (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Goff, Jacobsen and Mooney2019; Zimmerman et al. Reference Zimmerman, Brown, Hassel and Heck2019), presence of reworked or anachronous pollen grains and the time required to generate the large numbers of samples required to develop precise and accurate chronological frameworks. Flow cytometry has been demonstrated to lessen some of the challenges associated with obtaining sufficient concentrations of pollen grains (Kasai et al. Reference Kasai, Leipe, Saito, Kitagawa, Lauterbach, Brauer, Tarasov, Gosla, Arai and Sakuma2021; Kron et al. Reference Kron, Loureiro, Castro and Čertner2021; Tennant et al. Reference Tennant, Jones, Brock, Cook, Turney, Love and Lee2013; Zimmerman et al. Reference Zimmerman, Brown, Hassel and Heck2019). However, the applicability to sedimentary sequences has so far produced varying levels of success (Tennant et al. Reference Tennant, Jones, Brock, Cook, Turney, Love and Lee2013; Tunno et al. Reference Tunno, Zimmerman, Brown and Hassel2021; Zimmerman et al. Reference Zimmerman, Brown, Hassel and Heck2019).

Typically, the number of dates (dating density) used for palaeoenvironmental records are insufficient for identifying age outliers or short term changes in accumulation histories, and often produce overly optimistic precision estimates (Blaauw et al. Reference Blaauw, Christen, Bennett and Reimer2018). A recent meta-analysis indicated that the majority of late-Quaternary palaeo-environmental records contain fewer than one date per 1000 years (Blaauw et al. Reference Blaauw, Christen, Bennett and Reimer2018). There are many reasons why the 14C or other numerical ages of a depositional layer may be offset from the actual age of surrounding sediments (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009); therefore, scatter between dated samples, and potential presence of outlier samples within a sequence is often unavoidable. Increasing the density of dated layers within archives, in conjunction with the application of Bayesian age-depth modeling techniques, has been suggested to improve the interpretability of archives and provide reasonable chronological confidence at centennial scales (Blaauw et al. Reference Blaauw, Christen, Bennett and Reimer2018). In general, the precision of age-depth models should improve with increased dating densities (Blaauw et al. Reference Blaauw, Christen, Bennett and Reimer2018; Telford et al. Reference Telford, Heegaard and Birks2004; Trachsel and Telford Reference Trachsel and Telford2017), provided the ages are accurate.

When increasing the density of dated intervals is not possible, the incorporation of the inherent age uncertainty between dated layers can produce more realistic reconstructions and increase the confidence in palaeoenvironmental interpretations. Age uncertainties are important when comparing multiple palaeoenvironmental records and assessing the synchronicity of events across records and identifying drivers of change. There still remain few examples of studies that integrate the inherent age uncertainty from age-depth models when conducting meta-analyses (Anchukaitis and Tierney Reference Anchukaitis and Tierney2013; Cadd et al. Reference Cadd, Petherick, Tyler, Herbert, Cohen, Sniderman, Barrows, Fulop, Knight, Kershaw, Colhoun and Harris2021; Tierney et al. Reference Tierney, Smerdon, Anchukaitis and Seager2013; Tyler et al. Reference Tyler, Mills, Barr, Sniderman, Gell and Karoly2015). The most common approach remains the application of “best-fit” or mean modeled age for individual depths, with little consideration paid to age uncertainties or precision.

Here we report on a method of rapid batch-processing for the isolation of pollen concentrates using a combination of filtration and floatation used at the Chronos 14-Carbon Cycling Facility at the University of New South Wales. We test the applicability of this pollen extraction procedure and subsequent 14C dating from two important palaeoenvironmental archives in eastern Australia that have previously been identified as difficult to date with 14C methods (Forbes et al. Reference Forbes, Cohen, Jacobs, Marx, Barber, Dodson, Zamora, Cadd, Francke, Constantine, Mooney, Short, Tibby, Parker, Cendón, Peterson, Tyler, Swallow, Haines, Gadd and Woodward2021; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020). 14C ages previously obtained from bulk sediment, plant remains and charcoal from sediment sequences from the Thirlmere Lakes and Welsby Lagoon have exhibited substantial scatter and stratigraphic inversions. Lake Werri Berri is part of the Thirlmere Lakes systems, which have a series of repeating peat deposits that extend to MIS5 and beyond. Welsby Lagoon preserves a sedimentary record that spans the past 80,000 years. Previous work by Lewis et al. (Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020) and studies on similar sites from sub-tropical sand islands (Barr et al. Reference Barr, Tibby, Moss, Halverson, Marshall, McGregor and Stirling2017; Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Gadd, Marshall, Mcgregor and Jacobsen2020; Moss et al. Reference Moss, Tibby, Petherick, McGowan and Barr2013), have highlighted the difficulties involved in creating 14C chronologies from these macrophyte dominated, shallow wetland sediments. We compare 14C pollen-concentrate ages with 14C ages of a range of other organic fractions, including stable polycyclic aromatic carbon (SPAC) compounds (Ascough et al. Reference Ascough, Bird, Meredith, Wood, Snape, Brock, Higham, Large and Apperley2010). Using three different Bayesian age-modeling programs (Oxcal, rbacon and Undatable) we assess variations between different software approaches, extract 500 age-depth iterations for proxy uncertainty comparisons and independently validate our results using optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020).

METHODS

The two sedimentary sequences used in this study are both located on the eastern seaboard of Australia (Figure 1). Previous studies examining sedimentary sequences extracted from these locations suggest that both records extend beyond the last glacial maximum (Black et al. Reference Black, Mooney and Martin2006; Cadd et al. Reference Cadd, Tibby, Barr, Tyler, Unger, Leng, Marshall, McGregor, Lewis, Arnold, Lewis and Baldock2018; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020; Forbes et al. Reference Forbes, Cohen, Jacobs, Marx, Barber, Dodson, Zamora, Cadd, Francke, Constantine, Mooney, Short, Tibby, Parker, Cendón, Peterson, Tyler, Swallow, Haines, Gadd and Woodward2021), a rare occurrence in Australia (Cadd et al. Reference Cadd, Petherick, Tyler, Herbert, Cohen, Sniderman, Barrows, Fulop, Knight, Kershaw, Colhoun and Harris2021). However, previous work from sedimentary records in these locations has identified major outliers in the 14C chronologies (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020; Forbes et al. Reference Forbes, Cohen, Jacobs, Marx, Barber, Dodson, Zamora, Cadd, Francke, Constantine, Mooney, Short, Tibby, Parker, Cendón, Peterson, Tyler, Swallow, Haines, Gadd and Woodward2021), indicating the need for a more targeted approach to the development of 14C chronologies for these important records.

Figure 1 Map of eastern Australia with shading indicating mean annual precipitation from 1960 to 1990 (BOM). Insets show the locations of Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island) and Lake Werri Berri (part of the Thirlmere Lakes system). Elevation (metres above sea level) is indicated by shading, with 50-m contour lines overlain. Satellite images (Google Earth) of Welsby Lagoon and Lake Werri Berri are shown on the right.

Lake Werri Berri is part of the Thirlmere Lakes system, approximately 40 km inland from the New South Wales south coast (Figure 1). The Thirlmere Lake system comprises five presently ephemeral lakes within a late Tertiary abandoned river valley. The sediments of the Thirlmere Lakes display repeating sequences of organic clay, clay, and clayey sands overlain by up to 4 m of Holocene, organic-rich lacustrine and palustrine sediments (Black et al. Reference Black, Mooney and Martin2006; Forbes et al. Reference Forbes, Cohen, Jacobs, Marx, Barber, Dodson, Zamora, Cadd, Francke, Constantine, Mooney, Short, Tibby, Parker, Cendón, Peterson, Tyler, Swallow, Haines, Gadd and Woodward2021). See Supplementary Information for further coring and sedimentological details.

For Lake Werri Berri, 22 samples were measured for 14C. These were derived from bulk sediment, charcoal, unidentified plant remains, humic acid, SPAC residues (Ascough et al. Reference Ascough, Bird, Meredith, Wood, Snape, Brock, Higham, Large and Apperley2010; Field et al. Reference Field, Marx, Haig, May, Jacobsen, Zawadzki, Child, Heijnis, Hotchkis, McGowan and Moss2018) and pollen-rich preparations isolated from the upper 3 m of sediment (to constrain the Holocene portion of the sedimentary sequence). SPAC was isolated from Lake Werri Berri samples using hydrogen pyrolysis at the Advanced Analytical Centre, James Cook University, following the approach of Ascough et al. (Reference Ascough, Bird, Brock, Higham, Meredith, Snape and Vane2009) and Meredith et al. (Reference Meredith, Ascough, Bird, Large, Snape, Sun and Tilston2012). All labile carbon and cellulose containing material is removed during hydrogen pyrolysis, with only aromatic carbon, resistant to remineralisation, remaining in the SPAC residue (Ascough et al. Reference Ascough, Bird, Meredith, Wood, Snape, Brock, Higham, Large and Apperley2010).

Welsby Lagoon is a perched, currently ephemeral wetland situated in the parabolic sand dunes of Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island), located off the coast of Brisbane, southeast Queensland (Figure 1). The 1270 cm Welsby Lagoon sediment sequence has a basal age of ∼130 ka (MIS5) (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020). See Supplementary Information for further coring and sedimentological details.

Three phases of wetland development have been identified from the Welsby Lagoon sediment sequences: 1. Basal sands below 1250 cm indicating the development of the perched wetland during MIS5; 2. Homogeneous, fine-grained, organic sediments from 1250–500 cm; 3. Sub-fibrous, poorly decomposed, fine-grained, organic sediments from 500–0 cm. The transition between the phase 2 sediments, interpreted to represent lacustrine conditions, and phase 3 sediments, interpreted to represent ephemeral wetland conditions, has been suggested as a period of prolonged drying that may have led to the complete desiccation of the wetland surface. Current proxy and dating resolution, however, has been insufficient to confirm the length and extent of dry conditions (Cadd et al. Reference Cadd, Tyler, Tibby, Baldock, Hawke, Barr and Leng2020, Reference Cadd, Tibby, Barr, Tyler, Unger, Leng, Marshall, McGregor, Lewis, Arnold, Lewis and Baldock2018; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020). We refine the timing of the period prior to this sedimentological transition in the Welsby Lagoon sequence and 14C date 38 samples from charcoal, the >100 µm sediment fraction, humic acid and pollen-rich preparations.

Total Organic Carbon (TOC %) from Lake Werri Berri (n = 55) and Welsby Lagoon (n = 50) were analyzed at Mawson Analytical Spectrometry Services (MASS), University of Adelaide on a EuroVector Elemental Analyser. For Lake Werri Berri, sediment samples were oven dried at 40°C, passed through a 2 mm sieve and ground to a fine powder. Samples were calibrated against glycine, glutamic acid and triphenylamine standards. TOC (%) data from Welsby Lagoon were previously reported by Cadd et al. (Reference Cadd, Tibby, Barr, Tyler, Unger, Leng, Marshall, McGregor, Lewis, Arnold, Lewis and Baldock2018).

Pollen Extraction Method and Radiocarbon Dating (Chronos Facility, UNSW)

The pollen extraction method is summarised in Figure 2. Pollen processing was completed at Chronos, UNSW, following laboratory protocols outlined in Turney et al. (Reference Turney, Becerra-Valdivia, Sookdeo, Thomas, Palmer, Haines, Cadd, Wacker, Baker, Andersen, Jacobsen, Meredith, Chinu, Bollhalder and Marjo2021). Sediment sub-samples were initially dispersed in Milli-Q® water for 1 hr and mixed with a vortex mixer prior to sieving through a 100 µm pluriStrainer sieve. Material >100 µm (primarily composed of unidentifiable plant remains) from Welsby Lagoon was transferred into a separate centrifuge tube. The alkaline-soluble organic material was extracted from the sediment fractions by heating samples at 80ºC in a 0.2 M NaOH solution for 20 min. This step was repeated between 3 to 5 times, until the supernatant solution was nearly colourless. The first 3 supernatant rinses from each sample were transferred to glass beakers for humic acid extraction. The base-soluble organic humic acid fraction was precipitated from supernatant collected in glass beakers using excess 4 M HCl heated for 1 hour. HA samples were centrifuged and rinsed with Milli-Q water until the pH of supernatant was >3.

Figure 2 Schematic of the pollen concentrate batch processing method developed at the Chronos 14-Carbon Cycle Facility (UNSW). Flow chart includes extraction protocol for plant remains and humic acids radiocarbon dated in this study.

Pollen-rich concentrates were extracted from the <100 µm base-insoluble organic humin fraction remaining after repeated NaOH washes. The humin fraction was density separated using sodium polytungstate (SPT) (Merck, Germany) at specific gravity of 1.8. Density separated samples were centrifuged for 25 minutes at 2200 rpm before the bottom of each tube was frozen in liquid nitrogen and pollen-rich float decanted into a clean 50-mL tube.

Due to the highly organic nature of the sediment samples, a subsequent 0.2 M NaOH wash was conducted on pollen samples after density separation to break down any residual organic material. Separated samples were then sieved through a 70-µm pluriStrainer sieve and subsequently through a 20-µm pluriStrainer sieve, with material retained on the 20-µm sieve transferred to a clean 50-mL glass tube. Finally, 1 M HCl was added to each sample and heated for 1 hr at 80ºC.

Bulk sediment from Lake Werri Berri and the >100 µm fraction from Welsby Lagoon were pre-treated using standard Acid-Base-Acid (ABA) procedures outlined in Turney et al. (Reference Turney, Becerra-Valdivia, Sookdeo, Thomas, Palmer, Haines, Cadd, Wacker, Baker, Andersen, Jacobsen, Meredith, Chinu, Bollhalder and Marjo2021), yielding a humin fraction. A large charcoal fragment was identified during sieving of the sample at 570 cm depth from Welsby Lagoon. This charcoal sample was subsequently removed from the >100 µm fraction and pre-treated with standard ABA protocols. SPAC residue samples were treated with 1 M HCl prior to graphitisation.

A total of 56 14C samples were pre-treated, graphitised, and measured at the Chronos Facility at the UNSW (Tables 1 and 2). All pre-treated samples were graphitised with an AGE3 system (Ionplus, Switzerland), whereby samples were combusted in an Elemental Analyser with resulting CO2 passed through a zeolite trap and reduced to graphite with hydrogen over an iron catalyst (Turney et al. Reference Turney, Becerra-Valdivia, Sookdeo, Thomas, Palmer, Haines, Cadd, Wacker, Baker, Andersen, Jacobsen, Meredith, Chinu, Bollhalder and Marjo2021; Wacker et al. Reference Wacker, Bonani, Friedrich, Hajdas, Kromer, Němec, Ruff, Suter, Synal and Vockenhuber2010). 14C measurement was undertaken using a MICADAS (Ionplus, Switzerland) accelerator mass spectrometer (Wacker et al. Reference Wacker, Bonani, Friedrich, Hajdas, Kromer, Němec, Ruff, Suter, Synal and Vockenhuber2010), following Turney et al. (Reference Turney, Becerra-Valdivia, Sookdeo, Thomas, Palmer, Haines, Cadd, Wacker, Baker, Andersen, Jacobsen, Meredith, Chinu, Bollhalder and Marjo2021).

Table 1 Radiocarbon ages of the different sediment fractions from Lake Werri Berri analyzed in this study. Calibrated ages BP were calibrated using the SHCal20 calibration curve (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Heaton, Hua, Palmer, Turney, Southon, Bayliss, Blackwell, Boswijk, Bronk Ramsey, Pearson, Petchey, Reimer, Reimer and Wacker2020).

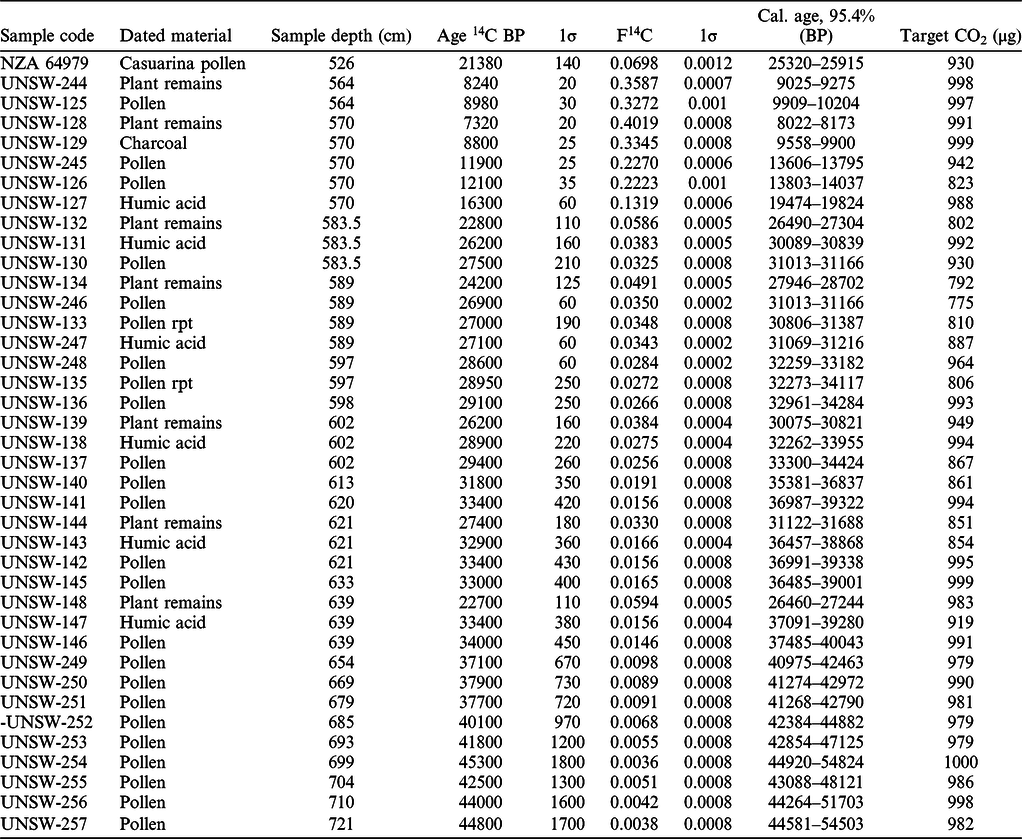

Table 2 Radiocarbon ages of the different sediment fractions from Welsby Lagoon analyzed in this study. Calibrated ages BP were calibrated using the SHCal20 calibration curve (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Heaton, Hua, Palmer, Turney, Southon, Bayliss, Blackwell, Boswijk, Bronk Ramsey, Pearson, Petchey, Reimer, Reimer and Wacker2020).

Radiocarbon Dating (ANSTO and Rafter Radiocarbon)

A pollen concentrate dominated by pollen from sclerophyllous tree species in the Casuarinaceae family was extracted from a sediment sub-sample from Welsby Lagoon (core WEL15-2) at 526 cm depth at Rafter Radiocarbon Laboratory at GNS Science, New Zealand, in 2018. See Supplementary Information for further details.

Four sediment sub-samples from the Holocene peats of the Lake Werri Berri (WB1) sedimentary sequence were analyzed at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO, Sydney, Australia) in 2019. Sediment samples were sieved at 500 µm to aid in locating macrofossil remains. Macrofossil remains selected for 14C dating included small twig fragments and elongated plant remains (Figure S1). Macrofossil remains were not identifiable to species and identifications are ambiguous as to whether they are terrestrial, or aquatic, plant remains or root material. The 14C dated charcoal samples included burnt seed pods, elongated plant remains and twigs. See Supplementary Information for further details.

Bayesian Age-Depth Modeling

The stratigraphic position of all calibrated 14C ages were initially examined in OxCal (Figures 3A and 4A). 14C ages from the same depth horizons were combined prior to calibration in OxCal and checked for internal consistency using a Chi-squared test during initial examination. Age-depth models from Lake Werri Berri incorporated the 22 14C ages obtained from the sediment sequence. The age-depth models constructed for the lacustrine phase of the Welsby Lagoon use the 38 14C ages obtained in this study and the 22 14C and 17 OSL ages reported by Lewis et al. (Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020).

Figure 3 Calibrated 14C ages for the different sediment fractions analyzed from Lake Werri Berri, plotted against sediment depth for A. All Calibrated 14C ages and B. Focus on the calibrated 14C ages of different sediment fractions from the same sediment layer.

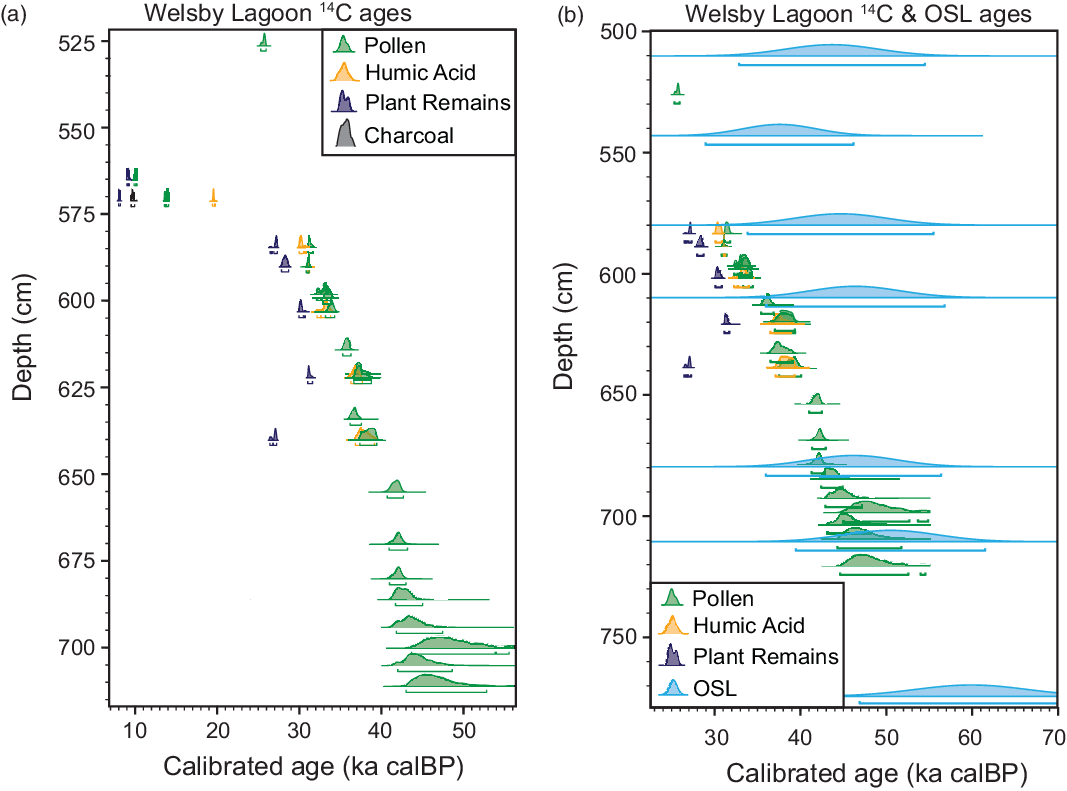

Figure 4 Calibrated 14C ages for the different sediment fractions analyzed from Welsby lagoon plotted against sediment depth for A. All Calibrated 14C ages between 525–725 cm depths and B. Comparison of calibrated 14C ages (this study) and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) ages from Lewis et al. (Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020) between 500–780 cm depths.

Bayesian age-depth models were developed for each sediment sequence using three programs, run across three different platforms; the stand alone “OxCal” program (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2008), the R based “rbacon” (Blaauw and Christen Reference Blaauw and Christen2011) and MATLAB program “Undatable” (Lougheed and Obrochta Reference Lougheed and Obrochta2019). 14C age determinations from the same depths, that passed the Chi-squared test, were combined prior to calibration and subsequent age-depth in both OxCal and Undatable. This feature is not available in the rbacon program, so 14C age were not combined prior to calibration and treated as separate samples. All 14C ages were calibrated using the SHCal20 calibration curve (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Heaton, Hua, Palmer, Turney, Southon, Bayliss, Blackwell, Boswijk, Bronk Ramsey, Pearson, Petchey, Reimer, Reimer and Wacker2020). Briefly, in OxCal a “P_Sequence” Poisson process model with a “General” outlier model was used. In rbacon default recommended memory prior parameters were used. In Undatable a sediment depositional simulation was used, with boot-strapped age-depth constraints subject to weighted random removal during each age-depth iteration. Full details of model development and code can be found in Supplementary Information.

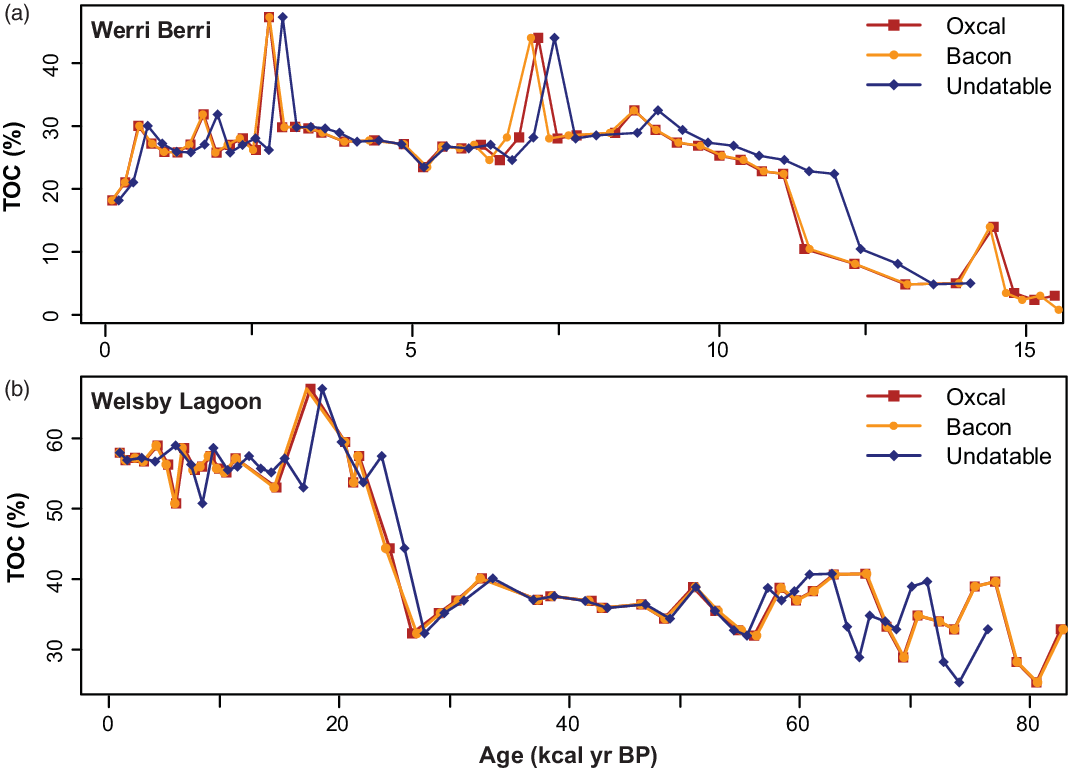

An ensemble of 500 age-depth model iterations were extracted using the three different Bayesian methods. Each ensemble was used to plot TOC (%) data against age from both sites to examine variations in the “uncertainty window” of each Bayesian model (e.g., Tibby et al. Reference Tibby, Tyler and Barr2018).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Pollen Radiocarbon Dating

The pollen concentrate method developed at Chronos provides a rapid, batch-processing method, which allows for 16 sediment samples (14 samples + 2 background samples) to be chemically pre-treated together in 1.5 days. Blanks processed using this method produce consistent, low F14C values, providing confidence that robust, finite ages <50,000 years can be achieved on pollen concentrate samples. The background measurements from the pollen samples extracted from >110,000 year old peat sediments from the Thirlmere Lakes (Forbes et al. Reference Forbes, Cohen, Jacobs, Marx, Barber, Dodson, Zamora, Cadd, Francke, Constantine, Mooney, Short, Tibby, Parker, Cendón, Peterson, Tyler, Swallow, Haines, Gadd and Woodward2021) using this method have yielded F14C values of 0.00318± 0.00007 (weighted average, n=18; including the Lake Werri Berri and Welsby Lagoon batches).

Lake Werri Berri

Radiocarbon Ages

For the Holocene peats of Lake Werri Berri, the calibrated age ranges from pollen concentrates overlap with the calibrated age ranges of bulk sediment, humic acid, and SPAC fractions from dated horizons at 111.3 (df = 4, χ2 = 3.45) and 123.7 cm sediment depth (df = 3, χ2 = 3.42) (Figure 3B; Supplementary Information). At sample depth 197.9 cm, the calibrated age ranges of the pollen concentrate, bulk sediment and humic acid samples overlap (df = 3, χ2 = 1.273), while the SPAC calibrated age displays poor agreement (Agreement Index; A = 5.3%), being ∼1,000 years younger. At sample depth 247.3 cm the pollen concentrate and humic acid calibrated age ranges overlap (df = 1, χ2 = 2.378), while the bulk sediment and the SPAC calibrated ages display poor agreement (A = 5.0% and A = 5.5%, respectively).

Charcoal or resistant aromatic carbon fractions (such as SPAC) in lacustrine environments can have considerable inbuilt age (Gavin Reference Gavin2001; Oswald et al. Reference Oswald, Anderson, Brown, Brubaker, Feng, Lozhkin, Tinner and Kaltenrieder2005; Eckmeier et al. Reference Eckmeier, van der Borg, Tegtmeier, Schmidt and Gerlach2009). One possible explanation for the bulk sediment sample at 247.3 cm returning an age approximately 400 years older than the pollen and humic acid fractions is that charcoal or resistant aromatic carbon, with substantial inbuilt age, may have been present within the bulk sediment (Eckmeier et al. Reference Eckmeier, van der Borg, Tegtmeier, Schmidt and Gerlach2009). In contrast, the SPAC samples analyzed from the deeper sediments of Lake Werri Berri (197.9 and 247.3 cm) returned ages ca. 1000 and 2000 years younger than other sediment fractions. The SPAC samples contained between 1–2% carbon, and subsequent CO2 amounts converted to graphite targets ranged from 137–338 ug C. We hypothesise that the lag between hydrogen pyrolysis, final HCl rinse and graphitisation (>1 year), storage of samples in humid environments and small sample size, may have increased the probability of contamination by CO2 or modern carbon during processing and graphitisation, which becomes increasingly pronounced in older samples (Paul et al. Reference Paul, Been, Aerts-Bijma and Meijer2016). The remainder of the paired samples (111.3 and 123.7 cm) fall within the calibrated error of the other 14C fractions dated, indicating there is limited vertical movement of these fractions through the sediment profile.

Of the four sediment sub-samples analyzed at ANSTO, the charcoal and unidentified plant remains at 107.6 cm and the charcoal remains at 269.6 cm display stratigraphic consistency with the 14C ages determined from the comparison depth locations analyzed (Table 1; Figure 3). The 14C ages of the unidentified plant remains at 159.5 and 284.5 cm are younger than the 14C ages from surrounding sediment layers (see discussion below; Table 1; Figure 3, Figure S1) suggesting they are likely to be composed, either entirely or partially, of intrusive root material from aquatic macrophytes growing across the wetland surface (Figure S1).

Age Modeling

The age-depth models produced by all three programs for Lake Werri Berri display similar results. 14C ages from the same depths that did not pass the Chi-squared test (SPAC sample at 197.9 cm and SPAC and bulk sediment at 247.3 cm; n = 3) were identified as outliers and manually rejected prior to age-depth modeling (Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Figure 5). In addition to the already identified outliers, the 14C age determinations of unidentified plant material at 159.5 and 284.5 cm returned calibrated ages 1000 to 2000 years younger than the age expected from the age-depth model and were classified as outliers (shown red, Figure 5). Re-assessment of the unidentified plant material indicates that this material may have been partially or wholly comprised of undecomposed root or sub-surface rhizome material. The re-evaluation of these samples provides confidence in the assignment of these samples as outliers.

Figure 5 Bayesian age-depth models for Lake Werri Berri developed using A. Oxcal, B. rbacon and C. Undatable. Simplified sediment stratigraphy is shown for the upper 3 m of the Werri Berri to the left of each model. Dates coloured in red were not used in model construction in Oxcal after being identified as outliers. The same samples were excluded from the Undatable model construction, however selected outliers cannot be plotted in Undatable. The red dates shown on the rbacon plot were included in the model construction, but are shown in red to indicate the Bayesian model did not pass through these ages. The sedimentation rate (cm/yr) calculated from each age-depth model is shown below each model. Mean sedimentation rate (cm/yr) is shown by the black lines and red shading represents the 95 and 68% age-depth uncertainty from 500 age-depth model iterations. Total organic carbon (%) plotted using weighted-mean (black line) and age-depth uncertainty from each age-depth model is shown in the bottom panel. Blue shading in the bottom panels represents the 95 and 68% age-depth uncertainty from 500 age-depth model iterations.

All three models display changes in sedimentation rate that are strongly controlled by the position of 14C ages (Figure 5). The rbacon models displays the highest frequency changes in accumulation rates, while Undatable displays the lowest frequency changes. When the mean age-depth model from each program is applied to the total organic carbon (TOC %) proxy data, both Oxcal and rbacon display similar results (Figures 5 and 7). The Undatable model produces a substantially different mean age-depth determination, providing ages up to 900 years older than the Oxcal and rbacon models at the same depth. The uncertainty windows, extracted from 500 age-depth model iterations, also display differences between the three different age models. The Undatable age model displays the greatest window of uncertainty, most notably between 5–15 ka cal yr BP. The OxCal and rbacon age-depth models display similar uncertainty envelopes, with OxCal producing a slightly greater uncertainty window at the base of the record between 12–15 ka (Figure 5).

Welsby Lagoon

Radiocarbon Ages

For the late Pleistocene record from Welsby Lagoon, the 14C ages of pollen concentrates from stratigraphically undisturbed sediments greater than 583.5 cm return increasing ages with increasing depth (Table 1, Figure 4A). 14C ages of all sediment fractions analyzed from 570 to 564 cm exhibit substantial scatter and age inversions. Calibrated age ranges of the >100 µm fraction do not overlap with the calibrated age ranges of pollen concentrate or humic acid fractions (Agreement Index=0% for all samples). The calibrated age ranges of the humic acid fraction overlap with the calibrated age ranges of pollen concentrates and pass the χ2 test at all depths greater than 583.5 cm where humic acids were analyzed: 639 cm (df = 2, χ2 = 0.78), 621 cm (df = 1, χ2 = 0.77), 602 cm (df = 1, χ2 = 2.3) and 589 cm (df = 2, χ2 = 0.93). There is slight overlap between calibrated age ranges of humic acid and pollen concentrate fractions at 583.5 cm, but poor agreement (df = 1, χ2 = 19.88, Acomb = 0.7%). There is no overlap between calibrated age ranges of any dated fraction (pollen concentrate, humic acid, >100 µm and charcoal) from sediment layers at 570 and 564 cm depths (Figure 4).

The >100 µm fraction extracted from the Welsby Lagoon sediment samples was primarily composed of unidentified plant remains. The 14C age determinations of the >100 µm fraction are consistently younger than the 14C ages from pollen concentrates and humic acid fractions from the same sediment layer (Figure 4). Similar to the unidentified plant remains from Lake Werri Berri, we consider the >100 µm fraction from Welsby Lagoon to be largely composed of root or rhizome material from aquatic macrophytes that grow across the wetland surface. Lewis et al. (Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020) suggested that the 14C ages on unidentified plant remains from Welsby Lagoon were likely to be chronological outliers. The additional analysis on paired samples here supports the conclusion of Lewis et al. (Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020) that these samples are unlikely to be stratigraphically reliable.

The palaeoenvironmental proxy data, sedimentology and chronological markers suggests that a transition from lake to swamp conditions occurred at Welsby Lagoon at 500 cm sediment depth (Cadd et al. Reference Cadd, Tibby, Barr, Tyler, Unger, Leng, Marshall, McGregor, Lewis, Arnold, Lewis and Baldock2018; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020). Substantial drying of the lacustrine system would have promoted the growth of aquatic macrophytes across the wetland and led to a transition to palustrine swamp conditions. The calibrated 14C ages of the >100 µm fractions, suggested to contain substantial root material (n = 5; 583.5–639 cm), range from 27.2–31.1 ka cal BP (95% CI), indicating that the site experienced widespread colonisation of aquatic macrophytes or terrestrial vegetation during this time. This timing, between ca. 27–31 ka cal BP, is consistent with progressive drying seen in similar systems along the east coast of Australia after 32 ka cal BP (Cadd et al. Reference Cadd, Petherick, Tyler, Herbert, Cohen, Sniderman, Barrows, Fulop, Knight, Kershaw, Colhoun and Harris2021; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Gadd, Jacobsen, Barr, Negus, Mariani, Penny, Chittleborough and Moss2021).

Sediment disturbance, in wash of anachronic material and penetration by root material are all possible causes of anomalous ages or outliers when dating wetland sedimentary sequences. Dated fractions from the sediment layers at 564 and 570 cm display a large range of age scatter and inconsistencies with other dated layers (Figures 4 and 6). Small organic particles and humic acids have been shown to migrate through sediment profiles (Clymo and Mackay Reference Clymo and Mackay1987), however, all 14C measurements from these depths display substantial scatter (up to 8.9 ka cal BP), indicating that the entire sediment layer was likely influenced by post-deposition disturbance or syn-depositional mixing. During prolonged periods of dry conditions, changes to the wetland surface may occur, including desiccation and dry cracking of underlying peat deposits and colonisation by rooted macrophyte or terrestrial vegetation. The location of the scattered ages at 564 and 570 cm, near the identified transition to swamp dominated sediments, supports the likelihood of post-depositional processes, related to changing wetland conditions, influencing these sediment layers.

Figure 6 Bayesian age-depth models for Welsby Lagoon developed using A. Oxcal, B. rbacon and C. Undatable. Simplified sediment stratigraphy is shown for the Welsby Lagoon core to the left of each model (adapted from Cadd et al. Reference Cadd, Tibby, Barr, Tyler, Unger, Leng, Marshall, McGregor, Lewis, Arnold, Lewis and Baldock2018). Dates coloured in red were not used in model construction in Oxcal after being identified as outliers. The same samples were excluded from the Undatable model construction, however selected outliers cannot be plotted in Undatable. The red dates shown on the rbacon plot were included in the model construction but are shown in red to indicate the Bayesian model did not pass through these ages. A “boundary” was specified in the OxCal model between the lacustrine and swamp phases of wetland development, in line with Lewis et al. (Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020). The sedimentation rate (cm/yr) calculated from each age-depth model is shown below each model. Mean sedimentation rate (cm/yr) is shown by the black lines and red shading represents the 95 and 68% age-depth uncertainty from 500 age-depth model iterations. Total organic carbon (%) plotted using weighted-mean (black line) and age-depth uncertainty from each age-depth model is shown in the bottom panel. Blue shading in the bottom panels represents the 95 and 68% age-depth uncertainty from 500 age-depth model iterations.

Figure 7 Total Organic Carbon (TOC %) from A. Lake Werri Berri and B. Welsby Lagoon plotted using mean age-depth determinations from Oxcal, rbacon and Undatable age-depth models.

Age Modeling

The modeled likelihood estimates failed to converge with all Welsby Lagoon age constraints included in OxCal, while model runs were completed in rbacon and Undatable using all age constraints (14C ages n = 58, OSL ages n = 17, Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020). The Undatable age-depth model was drawn towards the disturbed sediment ages at 564 and 570 cm when incorporating all age constraints. Assessment of material dated, and inspection of stratigraphic integrity of age determinations, led to several samples being identified as outliers and manually removed from subsequent model runs in Oxcal and Undatable (shown red in Oxcal model, outliers are not plotted in Undatable, Figure 6). 14C ages from the same sediment depths that did not pass the Chi-squared test (all >100 µm samples and depths 564 and 570 cm; n = 12) were identified as outliers and manually rejected prior to final age-depth modeling (Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Figure 6). All samples shown in Figure 6 were included in the rbacon model construction. The 14C ages identified as outliers and excluded from successive iterations by rbacon (shown in red, Figure 6), were the same ages identified as outliers by visual inspection and Oxcal outlier analysis.

The sedimentation rates and uncertainty windows, extracted from 500 age-depth model iterations, display differences between the three different age modeling programs. Undatable displays the largest window of uncertainty, in particularly between 60 and 80 ka, and a consistent, low sedimentation rate throughout. Oxcal and rbacon displays similar high frequency changes in accumulation rate at the same depth locations. The mean age-depth models from Oxcal and rbacon provide almost identical results for the timing of major changes represented in the TOC (%) data from Welsby Lagoon (Figures 6 and 7). However, the mean Undatable model produces a substantially different mean age-depth determination, producing ages up to 6,000 years older than the Oxcal and rbacon models at the same depths. These substantial differences between mean age-depth models occurs between 60 and 80 ka, where the Undatable model displays the greatest uncertainty window. In contrast, through the region of the core (580–720 cm) where the 20 pollen 14C ages have been incorporated in the age depth model, the three models show similar results and the lowest age-depth uncertainty (Figure 6).

Comparison with OSL Dates

Accuracy of pollen concentrate ages have previously been tested against other sedimentary fractions or independent chronological markers. Some studies have concluded that pollen concentrates may yield ages older than the depositional age of the sediment (Mensing and Southon Reference Mensing and Southon1999; Kilian et al. Reference Kilian, van der Plicht, Van Geel and Goslar2002; Newnham et al. Reference Newnham, Vandergoes, Garnett, Lowe, Prior and Almond2007; Martin et al. Reference Martin, Goff, Jacobsen and Mooney2019), while others have reported systematically younger pollen ages in comparison to other chronological markers (e.g., May et al. Reference May, Marx, Reynolds, Clark-Balzan, Jacobsen and Preusser2018). Older ages from pollen concentrates have been suggested due to preparation methods (Kilian et al. Reference Kilian, van der Plicht, Van Geel and Goslar2002), incomplete removal of non-pollen materials (Regnéll, Reference Regnéll1992; Richardson and Hall, Reference Richardson and Hall1994), inert organic fractions such as charcoal (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Goff, Jacobsen and Mooney2019) or storage and fluvial reworking of pollen in catchment soils (Mensing and Southon, Reference Mensing and Southon1999; Neulieb et al. Reference Neulieb, Levac, Southon, Lewis, Pendea and Chmura2013; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Xu, Turner, Zhou, Gao, Lü and Nesje2017; Zimmerman et al. Reference Zimmerman, Brown, Hassel and Heck2019). Younger than expected pollen concentrate ages have been attributed to preferential vertical mixing of airborne material through sediment profiles via dry cracks, and fungal and microbial growth during prolonged core storage (May et al. Reference May, Marx, Reynolds, Clark-Balzan, Jacobsen and Preusser2018; Neulieb et al. Reference Neulieb, Levac, Southon, Lewis, Pendea and Chmura2013; Wohlfarth et al. Reference Wohlfarth, Skog, Possnert and Holmquist1998). We assess the accuracy of the pollen concentrate ages from Welsby Lagoon using the independent OSL age determinations derived by Lewis et al. (Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020).

We find good agreement between pollen concentrate and OSL ages between 650 and 750 cm. However, whilst displaying overlapping uncertainty distributions, the pollen concentrate ages between 580 and 650 cm are younger than OSL ages in the same depth range (Figure 4; Figure 6). Low agreement between the pollen concentrate and OSL ages is apparent in the sediments underlying the transition to swamp at 500 cm. Cadd et al. (Reference Cadd, Tibby, Barr, Tyler, Unger, Leng, Marshall, McGregor, Lewis, Arnold, Lewis and Baldock2018, Reference Cadd, Tyler, Tibby, Baldock, Hawke, Barr and Leng2020) and Lewis et al. (Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020, Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Gadd, Jacobsen, Barr, Negus, Mariani, Penny, Chittleborough and Moss2021) hypothesised that the transitional boundary towards swamp-dominated sediments at 500 cm represented a period of substantial drying conditions. Dry cracking of underlying peat deposits or penetration by rooted emergent macrophytes is often associated with vertical mixing in ephemeral wetlands (May et al. Reference May, Marx, Reynolds, Clark-Balzan, Jacobsen and Preusser2018; Yaalon and Kalmar, Reference Yaalon and Kalmar1978). Desiccation of the peat or penetration of macrophyte roots underlying the 500 cm boundary may have affected all organic fractions dated. The presence of non-pollen organic contaminants in the pollen concentrate ages may be more likely in the wetland sediments directly underlying the 500-cm boundary. This observation, together with the pollen samples identified as outliers and scattered 14C ages obtained for different fractions between 564 and 570 cm, reinforces our interpretation that these layers were likely influenced by some degree of post-deposition disturbance or syn-depositional mixing. Translocation of younger pollen and other organic contaminants may have also affected the sediment below 570 cm, however the closely spaced pollen concentrate samples below this depth display clear relationship of increasing age with depth, without evidence of age reversals or outliers (Figures 4 and 6).

Vertical movement of sand-sized inorganic material via desiccation cracks or post-depositional mixing could equally have affected the reliability of the OSL ages in this part of the sequence. However, the single-grain equivalent dose (De) datasets of the four OSL samples from 510 to 610 cm do not exhibit discrete dose components indicative of widespread mixing (Arnold et al. Reference Arnold, Demuro, Navazo, Benito-Calvo and Pérez-González2013). The mean overdispersion value of these four samples (34.5 ± 2.3%) is higher than that typically reported for well-bleached and unmixed OSL samples (Arnold and Roberts Reference Arnold and Roberts2009), though it is consistent with those obtained for the twelve samples from the underlying layers (710 and 1270 cm; mean overdispersion = 33.3 ± 0.8%), which yielded OSL ages in agreement with the pollen concentrates. These De distribution characteristics were interpreted by Lewis et al. (Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020) as indicative of beta dose heterogeneity in the organic-rich matrices or minor near-surface bioturbation (e.g., root penetration) soon after deposition.

Additional factors that might explain the OSL and pollen 14C age offsets include unaccounted systematic errors in the OSL dose rate calculations. These may include deviations in the adopted long-term water contents, spatial heterogeneity in the gamma irradiation fields not adequately captured by laboratory dosimetry evaluations, undetected open-system behaviour in the 238U decay series, time-dependent changes in organic content, or complex compaction and dewatering effects. However, most of these factors would affect individual samples in opposing directions, and by non-uniform amounts, meaning they effectively represent random uncertainties at the site level. In addition, the existing OSL uncertainty calculations take into consideration spatial and temporal variations in dose rate parameters where they cannot be constrained directly (e.g., a ±10% variation in average water content has been included in the 2σ dose rate uncertainty calculations to account for punctuated drying events, such as that associated with the 500 cm boundary). While it is possible the minor offsets in the OSL and pollen 14C ages between 580 and 650 cm could be attributed to systematic dosimetric effects, the combined paleoenvironmental evidence from Cadd et al. (Reference Cadd, Tibby, Barr, Tyler, Unger, Leng, Marshall, McGregor, Lewis, Arnold, Lewis and Baldock2018, Reference Cadd, Tyler, Tibby, Baldock, Hawke, Barr and Leng2020) and Lewis et al. (Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Barr, Marshall, McGregor, Gadd and Yokoyama2020, Reference Lewis, Tibby, Arnold, Gadd, Jacobsen, Barr, Negus, Mariani, Penny, Chittleborough and Moss2021) and chronological evidence presented here (including the scattered 14C and age inversion at 564 and 570 cm) provides strong evidence for locally complex depositional processes associated with a substantial dry phase at 500 cm; potentially influencing both pollen concentrate and OSL ages, but to seemingly different extents.

Age-Depth Software Comparison

The mean age-depth profiles from Oxcal and rbacon provide very similar results when applied to the TOC (%) proxy data at both Lake Werri Berri and Welsby Lagoon (Figure 6). The mean age-depth model profile applied to the TOC (%) data from Undatable displays substantial differences to the Oxcal and rbacon models (Figure 6). The Undatable age-depth models for both sites also exhibits both the smoothest sedimentation rates and the largest uncertainty windows.

The Undatable software has two important features that are not included in either Oxcal or rbacon, the bootstrapping function and the ability to incorporate depth uncertainty to dated layers (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2008; Blaauw and Christen Reference Blaauw and Christen2011; Lougheed and Obrochta Reference Lougheed and Obrochta2019). The bootstrapping function within Undatable leads to an expansion of the uncertainty envelope when ages display increased scatter and reduces inflection points related to individual ages. This reduces the influence individual ages have on associated modeled chronologies and modeled accumulation rates, as seen in the Welsby Lagoon record (Figure 5). In addition, the xfactor function, which alters the scaling of the Gaussian functions determining the position of points between dated layers, increases the uncertainty window as distance between age constraints increases (Figures 4 and 5; Lougheed and Obrochta Reference Lougheed and Obrochta2019). These features of Undatable were included to allow the construction of age-depth models that incorporate realistic uncertainties, however as a consequence, age-depth models are less likely to identify small variations in sedimentation rate, unless those changes are supported by a high density of ages.

The Oxcal software provides a range of functions alongside its ability to produce age-depth models and has the most objective outlier analysis of all three of the model software. Oxcal’s outlier analysis allows the user to weight samples according to the likelihood an individual age determination is expected to be an outlier and apply an appropriate model to revise the age within the model context (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009). In addition to this method to weight individual dates, if an outlier model is not employed, an agreement index is indicated for individual ages and can indicate which age determinations are likely to be erroneous (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey1995, Reference Bronk Ramsey2009). Whilst Oxcal has robust methods for outlier detection, when a large number of outliers are present within a sequence, the internal consistency and reliability tests may result in the model failing to converge. This may require the user to manually remove samples until convergence is reached. In the case of the Welsby Lagoon model, without the removal of >70% of the outlier ages (indicated in red, Figure 5) the Welsby Lagoon model failed to converge. The identification and systematic removal of outliers can be time consuming and subjective when prior information identifying outlier samples is not available or straightforward.

The rbacon software uses a Student’s-t model to determine the presence of outliers, which assumes that the reported error cannot be truly known (Blaauw and Christen Reference Blaauw and Christen2011). This model has been shown to be robust to the presence of outliers and explaining the intrinsic scatter noted in radiocarbon measurements (Blaauw and Christen Reference Blaauw and Christen2011). The results from the rbacon models of Lake Werri Berri and Welsby Lagoon indicate that the outlier identification model works for these sites. The outlying samples that were identified and manually excluded through each successive Oxcal model construction, were identified and excluded by the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) iterations of rbacon, without the need for manual removal by the user.

For both Lake Werri Berri and Welsby Lagoon, rbacon successfully identified outliers without detailed prior site information. This ability makes rbacon a good choice when producing multiple age-depth models, particularly when the user does not have an intimate knowledge of a site (e.g., Dixon et al. Reference Dixon, Tyler, Henley and Drysdale2019; Cadd et al. Reference Cadd, Petherick, Tyler, Herbert, Cohen, Sniderman, Barrows, Fulop, Knight, Kershaw, Colhoun and Harris2021). The P_Sequence Poisson process depositional model in Oxcal was particularly difficult for the longer and more complicated Welsby Lagoon record. Oxcal has robust outlier identifications and model options, however, only returns a result when model convergence is successful. For the Welsby Lagoon record, multiple dated layers had to be classified as outliers for the OxCal model to achieve convergence.

In summary, all three software programs produced robust and easy to construct age-depth models for the Holocene record from Lake Werri Berri. For the longer and more complicated Welsby Lagoon record, the three software programs produced age-depth models with varying levels of ease, coding ability and knowledge of site-specific factors. All three models produced almost identical results for the period between 35 and 55 ka in the Welsby Lagoon sequence where a high density of dated layers was incorporated (Figure 6). The high density of pollen concentrate ages in this portion of the record provides sufficient constraints for the development of a precise age-depth model, suggesting that all programs would perform similarly in densely dated sedimentary sequences.

CONCLUSION

Often, wetland sedimentary sequences are devoid of sufficient terrestrial macrofossils to allow the development of well resolved, robust, 14C chronologies. In the absence of terrestrial macrofossils, other sediment components, such as bulk sediments, charcoal, coarse or fine sieved fractions, and terrestrial microfossils may provide the only option. Here we report a rapid, batch-processing, filtration and floatation method for isolating pollen concentrates to develop robust chronologies from two regionally important wetland sequences. Through the comparison of ages from different sediment fractions, and the application of Bayesian age-depth modeling, we demonstrate that in the absence of terrestrial macrofossils, terrestrial microfossils (pollen) can be used to create robust chronologies in both Holocene and MIS3 sedimentary records. The pollen concentrate 14C measurements determined from Lake Werri Berri and Welsby Lagoon return stratigraphically consistent ages, and often display overlapping calibrated age ranges with other 14C-dated fractions (humic acids, bulk sediment, SPAC; Figure 4) and OSL dated sediment layers. Discrepancies between 14C dated sediment fractions highlight the need to identify the most appropriate fraction for targeted dating based on site specific factors. The offset between pollen concentrate 14C ages and OSL dated sediment layers between 500 and 650 cm at Welsby Lagoon, in addition to the identification of outliers at 564 and 570 cm, provides evidence for post-depositional sediment mixing associated with a drying climate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island) and the surrounding waters as Quandamooka Country and thank the Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation for permission to undertake the work. We acknowledge the area of the Nattai System of Reserves and Thirlmere Lakes National Parks as D’harawal country. We thank Jonathan Marshall, Glenn McGregor, and Cameron Shultz for assistance in many aspects of the Minjerribah project. The work was supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Project (DP150103875) and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH, Project Number CE170100015). Radiocarbon dating at the Centre for Accelerator Science, ANSTO was conducted with the support of ANSTO grant AP11938 to Tim Cohen and by an AINSE Ltd. Honours Scholarship to Bryce Sherborne-Higgins.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2022.29