INTRODUCTION

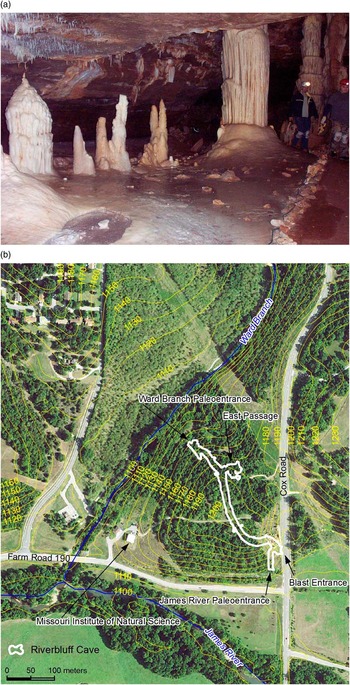

Riverbluff Cave was discovered in late 2001 when a road construction crew blasted into a large room near one of the cave’s (former) natural entrances (Fig. 1a). Before the blast, all natural entrances had been sealed by various geologic processes; thus, the general condition of the cave prior to closure had been preserved for some unknown duration. Members of the Missouri Speleological Survey (MSS) soon began mapping the cave (Fig. 1b) and discovered well-preserved trackways and claw marks within and atop an upper sediment layer, along with various rodent, snake, and peccary skeletons (Rovey et al., Reference Rovey, Forir, Balco and Gaunt2010). Additionally, fossil remains of larger vertebrates, including horse and mammoth, were visible within a gravel bed within a stratified sequence along the cave’s main passage (Fig. 2, Table 1). These discoveries prompted county officials to purchase the land above the cave and establish the Missouri Institute of Natural Science Museum to catalog and preserve the cave’s specimens.

Figure 1 (color online) Riverbluff Cave. (a) Main room. This photograph shows a large room just inside the cave’s blast entrance. (b) Location of Riverbluff Cave between Ward Branch and James River. The contours (feet above mean sea level) are from the local U.S. Geological Survey 7.5′ quadrangle map. The Missouri Speleological Survey provided a draft of this figure.

Figure 2 (color online) Fossils from the gravel beds within Riverbluff Cave (see Table 1). (a) Mammoth tibia. (b) Mammoth rib. (c) Mammoth, juvenile jaw and molar. (d) Horse metacarpal.

Table 1 Faunal list from the “Mammoth Horizon” (layers 6/7) in Riverbluff Cave.

Notes: We thank Larry Agenbroad (deceased) and Greg McDonald for examining the mammoth and horse bones, respectively. Specimens are curated at the Missouri Institute of Natural Science Museum, Springfield, Missouri. The provisional assignment of the mammoths to M. trogontherii is based on the molar dentition, although the juvenile characteristics make this assignment more difficult.

Mammoth and horse fossils have been found previously in Missouri and Missouri caves (Kurtén and Anderson, Reference Kurtén and Anderson1980; Hawksley, Reference Hawksley1986), but mammoth finds are rare, and these discoveries have rarely, if ever, been made within a precise geologically datable context. Therefore, we conducted a series of dating techniques for these strata to determine or constrain their ages and the general history of the cave. Recently, the institute staff assigned the mammoth remains provisionally to the species Mammuthus trogontherii (steppe mammoth) based on a juvenile molar. If this assignment is confirmed by additional discoveries, these results would support the recent theory that M. trogontherii was the ancestral mammoth species in North America (Lister and Sher, Reference Lister and Sher2015).

SETTING

Riverbluff Cave is in Greene County, Missouri, near the southeast margin of the Springfield Plateau Physiographic Subprovince (Fig. 3), which is largely defined by a caprock of the Burlington-Keokuk Formation. This formation is a tightly cemented crinoidal grainstone, which is highly susceptible to karstification and cave development. Most caves of the Springfield Plateau are branchwork or rudimentary/single-passage types (Dom and Wicks, Reference Dom and Wicks2003), implying origins from point-source recharge within upland sinkholes or swallow holes along sinking streams. Riverbluff Cave (Fig. 1) is such a single-passage cave between Ward Branch and the James River. A (short?) offshoot (East Passage) is nearly sealed from the main passage by breakdown materials and indicates that the cave once may have been part of a more extensive branchwork system. Current seepage into the cave drains downward from several sump areas, indicating that an undiscovered lower tier may be present and/or developing beneath the explored level.

Figure 3 Regional location map.

The top of the Ward Branch paleoentrance is approximately 13 m above the present channel. After that entrance was abandoned because of incision, it was eventually sealed by a combination of breakdown within the cave and colluvium from the upper bluff. The James River paleoentrance extends to the top of a fluvial terrace at approximately 9 m above the modern floodplain. That entrance is choked with fine-grained sediment, possibly a combination of soil colluvium and vertical-accretion (overbank) deposits from the James River.

The Ward Branch paleoentrance is several meters higher than the James River paleoentrance. Thus, the cave floor generally slopes toward the James River, in accordance with the surface drainage, and sediment normally would have entered the cave from its upstream or Ward Branch direction. Nevertheless, flooding along the James River also could have reached the downstream paleoentrance, flowed back into the cave, and deposited fine-grained suspension sediment.

CAVE DEVELOPMENT MODEL

Stock et al. (Reference Stock, Granger, Sasowsky, Anderson and Finkel2005) presented a model that appears to closely describe the formation, infilling, and abandonment of Riverbluff Cave. In this model, single-passage caves develop between a master stream and a swallow hole in a tributary. Coarse sediment is transported from the swallow hole as bed load and deposited within the cave so long as that entrance is very close to the channel elevation. During this time, any fine-grained sediment, temporarily deposited during waning flow or as infiltration through the ceiling, is periodically flushed from the cave during high-discharge events. Thus, fine-grained sediment generally does not accumulate during this early phase of sedimentation.

As the tributary incises below the swallow hole, that entrance is abandoned and coarse sediment no longer enters the cave. Thereafter, fine-grained sediment is transported into the cave as suspended load during flooding along the master stream, so long as that entrance is within the maximum flood height. This later sediment caps the earlier coarse materials and becomes finer upward as the main stream incises progressively farther below that entrance. After the backflow ceases and the cave “enters” the vadose zone, speleothems and flowstone eventually form a cap above the detrital sediment.

With minor modifications, this model fits the features of Riverbluff Cave. One potential difference relates to the cave’s (inferred) former branchwork pattern. Cave development from the Ward Branch swallow hole likely intersected and enlarged an existing conduit in the vicinity of East Passage.

SEDIMENT SEQUENCE

Riverbluff Cave is consistent with the model described previously in that coarse-grained detrital sediment is generally overlain by laminated silty clay (Table 2, Fig. 4). The coarse sediment must have entered the cave from the upstream (Ward Branch) direction, given the slope toward the James River paleoentrance. We interpret the fine-grained laminated sediments as slack-water facies (i.e., Bosch and White, Reference Bosch and White2004; White, Reference White2007), which were deposited within local sumps or throughout the cave during flooding along the James River. In discussing these strata, we follow conventions established by the MSS in numbering consecutive sediment “layers” from the top down, although we discuss them in geologic sequence (oldest to youngest).

Figure 4 Sedimentary strata within Riverbluff Cave. The location is where the cave passage is below the 1200 contour closure in Figure 1. Photograph shows layers 4–9. Layers 6/7 are the fossiliferous gravel beds. Yellow pins are survey markers 60 cm apart vertically; excavations (arrows) are sample sites for both paleomagnetic and cosmogenic-isotope analyses. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 2 Sediment layers in Riverbluff Cave.

Note: Textural percentages are for the ≤2 mm fraction.

The sediment within Riverbluff Cave is unusual for Missouri caves (Reams, Reference Reams1998) and elsewhere (White, Reference White1988) in that a consistent sedimentary sequence is present throughout much of the cave (Table 2, Fig. 4). The earliest fluvial sediments fully exposed (layers 9 and 10) are thin (~10–20 cm) beds of sandy loam with sparse (≤2%) gravel. Layer 10 (older) is preserved locally, but overlying strata can be traced more extensively throughout the cave wherever a flowstone caprock has not buried the younger detrital sediment.

Layer 8, the “gray silt” (~50–100 cm) has a complex postdepositional redox history and is distinct from all other strata within the cave. It is a gray (gleyed) laminated silt containing abundant organic debris as both wood and humus concentrated within organic-rich laminae. Gleying is locally splotchy and more intense around the organic inclusions, proving that reduction was at least partly postdepositional. The silt also preserves faint oxidized mottles, which locally cut across the intensely gleyed splotches. These features indicate a general loss of primary iron oxides via reduction and dissolution with local preservation of secondary iron oxides that segregated into mottles during intermittent aeration, as is common within reduced (Bg) soil horizons (e.g., Hallberg et al., Reference Hallberg, Fenton and Miller1978). Layer 8, although more extensive than layer 10 below, also appears to be a localized deposit situated above a low area of the cave’s rock floor. We interpret this layer as a deposit from locally ponded water that collected within a slowly draining sump between high-discharge events.

Layer 8 is overlain by coarse gravelly pebbly sands of variable thickness and with larger cobble clasts, designated as layers 6 and 7 (the “gravel beds”). The particle-size distribution of these beds is distinctly bimodal; although they contain >20% clay, the percentage of total fines decreases downward, and fine silt is absent at the base. A current that could prevent deposition of fine silt should have also prevented clay deposition, so the fines likely infiltrated into the gravel from above during deposition of the overlying red clay.

Layers 6 and 7 are coarser than all other strata within the cave and seem to indicate an unusually high-discharge event. These layers are designated as two units because they are separated locally by a thin silty bed, although they are otherwise visually indistinguishable. Both layers have vague cross bedding, and the upper gravel surface is hummocky; thus, we interpret the gravel as amalgamated sets of gravel bars. The gravel contains unusually high concentrations of vertebrate fragments; limited excavation to date (several cubic meters) has yielded dozens of specimens of seven different taxa including at least two different mammoths (Table 1). The high concentration of vertebrate bones suggests several possible scenarios: (1) these individuals died in the cave, (2) smaller remains were dragged into the cave by predators, or (3) they died just outside the cave during a local mass-mortality event.

A fining-upward sequence of laminated red clay (layers 1–5) rests on the gravel beds. We interpret the “red clay” sequence as a slack-water facies ponded by backflow from the James River during floods. Although bedding planes are discernable within this sequence, they are not generally traceable beyond a few meters. The different “layers” actually denote uniform (30.5 cm) divisions established by the MSS for surveying and sampling. The upper part of the red clay (layers 1 and 2) is burrowed and includes abundant (up to 8% by weight) small fragments of rodent bone. It is unclear whether these fragments are detrital, intrusive, or both.

Sometime after deposition, the detrital sedimentary sequence was partially exposed along a small gully in portions of the cave (Fig. 4). The red clay (layers 1–5) is capped locally by speleothems and flowstone, although in several locations stalagmites are partially buried within the clay, indicating contemporaneous detrital and chemical sedimentation.

DATING METHODS

Biostratigraphy, radiocarbon, and U-Th

The major focus of this work is dating the various vertebrate fossils that have been found within Riverbluff Cave. In this section, we first summarize general biostratigraphic observations and preliminary results from radiocarbon and U-Th data. These methods have not yielded unambiguous results but provide some age constraints. In subsequent sections, we more thoroughly discuss paleomagnetic and cosmogenic-nuclide measurements that provide a detailed chronology for portions of the Riverbluff Cave sediment sequence.

Mammoth (Mammuthus) remains in North America imply an approximate age between 1.5 Ma and 10 ka (Kurtén and Anderson, Reference Kurtén and Anderson1980; Graham, Reference Graham1998, Lister and Bahn, Reference Lister and Bahn2007), but beyond this range, we had no initial age constraints for the sediment layers and their fossil remains. We first attempted radiocarbon analysis on a peccary tooth recovered from atop the red clay (layer 1). The result, however, is an open age of approximately >55,000 14C yr BP. This result, combined with the presence of mammoth remains in layers 6 and 7, provides a wide age bracket of ~55,000 ka to 1.5 Ma for layers 1–7.

We attempted to obtain additional age control with U-Th dating of buried speleothems (e.g., Dorale et al., Reference Dorale, Edwards, Alexander, Shen, Richards and Cheng2004). Two stalagmites from atop the red clay (layer 1) were thus collected and analyzed, but these results were unusable because of low uranium values.

Paleomagnetism

Paleomagnetic remanence can provide useful information on cave-sediment age, particularly when combined with other techniques (e.g., White, Reference White2007). Paleomagnetic datums within a series of tiered cave passages were first used to estimate stream incision rates in the Mammoth Cave and Appalachian Plateau regions (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1982; Sasowsky et al., Reference Sasowsky, White and Schmidt1995; Springer et al., Reference Springer, Kite and Schmidt1997). More recently, paleomagnetic measurements have been used in combination with cosmogenic-nuclide burial ages of sediment in other caves (Stock et al., Reference Stock, Granger, Sasowsky, Anderson and Finkel2005; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Matmon, Fink, Ron and Niedermann2011; Matmon et al., Reference Matmon, Ron, Chazan, Porat and Horwitz2012).

The possible age range of ~55 ka to 1.5 Ma for sediment layers 1–7 spans portions of two polarity chrons, the Brunhes Normal (~0.77 Ma to present) and the Matuyama Reversed (2.6 Ma–0.77 Ma), (Singer, Reference Singer2014). Additionally, a short normal subchron (the Jaramillo) occurred between ~1.08 and 1.01 Ma. Therefore, any reversed remanence within these strata would require a depositional age >0.77 Ma. A normal detrital remanent magnetization (DRM; the remanence acquired during deposition) would give a presumptive age of <0.77 Ma, with only a slight chance of an older age coinciding with the Jaramillo Subchron.

We collected 30 samples for paleomagnetic analysis from the fine-grained sediment layers within Riverbluff Cave. Initially, we collected four sets of six samples from layers 8 and 3–5. We avoided sampling coarse-grained sediment and the upper burrowed portions of the red clay (layers 1 and 2). Five of the six samples in these initial sets were collected for alternating-field (AF) demagnetization by pressing an oriented plastic box into a leveled surface within each sampling horizon. A sixth sample per set was collected for thermal demagnetization by casting a plaster cube around a pedestal cut into a leveled surface. After demagnetization of these original 24 samples, we collected 6 additional samples for thermal demagnetization from layer 8, for reasons discussed subsequently.

All paleomagnetic samples were subjected to stepwise demagnetization using either AF or thermal techniques. After each demagnetization step, the sample’s magnetic remanence was measured in multiple orientations to help assess the stability of remanence and to determine an optimum demagnetization level. After demagnetization, the high- and low-frequency magnetic susceptibility was measured for each sample to determine the bulk magnetite content and its frequency dependence, which is a function of grain size and remanence stability. Later, remanence intensities were measured under a series of applied direct current fields to construct isothermal remanence curves for one sample per set. The general shape of the isothermal remanent magnetization (IRM) curves is particularly diagnostic in distinguishing hematite/goethite versus magnetite dominance as the mineral carrier of the magnetic remanence.

Cosmogenic-nuclide burial dating

The technique of “burial dating” using the cosmic ray–produced nuclides 26Al and 10Be has been widely used to date cave sediment within tiered passages of cave systems along major drainages and hence to quantify rates of stream incision and landscape development (Granger et al., Reference Granger, Kirchner and Finkel1997, Reference Granger, Fabel and Palmer2001; Anthony and Granger, Reference Anthony and Granger2004; Stock et al., Reference Stock, Anderson and Finkel2004, Reference Stock, Granger, Sasowsky, Anderson and Finkel2005, Reference Stock, Riihimaki and Anderson2006).

The basic idea of burial dating using the 26Al and 10Be pair in quartz is that when quartz grains reside at Earth’s surface, nuclear reactions induced by cosmic radiation produce these nuclides at a fixed ratio. If the quartz is then deposited in a subsurface location (i.e., a cave) where it is shielded from cosmic radiation by thick overlying rock or sediment, then production is nearly completely halted, and accumulated 26Al (t1/2=0.7 Ma) decays faster than 10Be (t1/2=1.4 Ma). Thus, the 26Al/10Be ratio in quartz in fluvial sediments within caves is inversely proportional to the length of time the sediment has resided in the cave.

Quartz grains within the cave sediment are predominantly chert from local limestone bedrock, as well as paleosols and weathering residuum developed on this bedrock. As the cave roof consists of the same bedrock, chert nodules could have been deposited inside the cave by rockfall from the cave roof, in which case they would be unsuitable for burial dating. However, these nodules are uniformly larger than a few centimeters in size, whereas fluvially transported chert grains display a large range of grain sizes. Thus, we extracted medium to coarse sand (0.125–0.85 mm) from cave sediment by disaggregating in water and wet sieving, then we isolated and purified quartz grains by carbonate dissolution in HNO3 or HCl followed by repeated etching in dilute HF interspersed with sonication in a hot KOH solution to disaggregate fluoride precipitates. Total Al concentrations in the resulting quartz separates were 100–150 ppm. We extracted Al and Be from quartz separates by standard methods of HF dissolution and column chromatography (Stone, Reference Stone2004), determined total Al concentrations by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrophotometry on aliquots of the dissolved sample, and measured Al and Be isotope ratios by accelerator mass spectrometry at the Center for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Total carrier and process blanks varied between 5700±2200 and 17,300±4200 atoms 10Be and between 22,000±22,000 and 65,000±50,000 atoms 26Al and were always less than 0.1% of the total number of atoms measured. Be isotope ratio measurements were originally normalized to the standard KNSTD3110 (Nishiizumi, Reference Nishiizumi2004a); however, we have renormalized them to the 07KNSTD3110 standard (Nishiizumi et al., Reference Nishiizumi, Imamura, Caffee, Southon, Finkel and McAnich2007). Al isotope ratio measurements are normalized to the KNSTD standards (Nishiizumi, Reference Nishiizumi2004b).

Zerathe et al. (Reference Zerathe, Braucher, Lebourg, Bourlès, Manetti and Léanni2013) showed that standard methods of purifying quartz by dilute HF etching were not adequate to entirely remove contamination by atmospherically produced 10Be for some chert samples. However, the maximum concentration of spurious 10Be they observed in their study was ~20,000 atoms/g, which is 1%–2% of typical 10Be concentrations observed in Riverbluff Cave samples and smaller than analytical uncertainties. In addition, they showed that leaching in KOH (which, as noted previously, is employed in the University of Washington laboratory as a means of improving efficiency of the HF etching by disaggregating fluoride precipitates) also improves the efficiency of removing atmospheric 10Be. For these reasons, we assume that contamination by atmospherically produced 10Be is insignificant.

Our primary objective was to determine the depositional age of the fossiliferous gravel beds, particularly the level with concentrated vertebrate fossils at the layer 6–layer 7 contact. Thus, samples include (1) a composite sample from the fossiliferous gravel spanning the layer 6–layer 7 contact, (2) above the gravel near the base of the red clay in layer 5, (3) directly below the gravel within the top of the gray silt in layer 8, and (4) in silty units in subjacent layers 9 and 10. We did not analyze any samples in the red clay above layer 5 because of the low concentration of sand-sized quartz grains.

In calculating burial ages, we assume that quartz grains experienced a two-stage exposure history in which they originated from steady erosion of the watershed upstream of the cave and were then washed into the cave and have remained buried at their present depth since that time. This would be true regardless of whether sediment originated from Ward Branch or the James River. Given these assumptions, 26Al and 10Be concentrations are related to the burial age of the sample as follows:

where

![]() $$N_{i,m}$$

is the measured concentration of nuclide i at the present time (atoms/g),

$$N_{i,m}$$

is the measured concentration of nuclide i at the present time (atoms/g),

![]() $$P_i(0)$$

is the surface production rate of nuclide i (atoms/g/yr),

$$P_i(0)$$

is the surface production rate of nuclide i (atoms/g/yr),

![]() $${\lambda _i}$$

is the decay constant for nuclide i,

$${\lambda _i}$$

is the decay constant for nuclide i,

![]() $$z_b$$

is the burial depth of the sample (g/cm2),

$$z_b$$

is the burial depth of the sample (g/cm2),

![]() $$ P_i(z_b)$$

is the production rate (atoms/g/yr) at the burial depth of the sample,

$$ P_i(z_b)$$

is the production rate (atoms/g/yr) at the burial depth of the sample,

![]() $${\epsilon}$$

is the surface erosion rate prior to burial (g/cm/yr),

$${\epsilon}$$

is the surface erosion rate prior to burial (g/cm/yr),

![]() $$ t_b$$

is the duration of burial (yr), and

$$ t_b$$

is the duration of burial (yr), and

![]() $$\Lambda $$

is the effective attenuation length for spallogenic production (here taken to be 160 g/cm2). The first term on the right-hand side of these equations is the formula for the nuclide concentration in a steadily eroding surface, with a radioactive decay factor applied to correct it to the present time; the second term is the nuclide inventory produced at the sample depth during the period of burial. If the sample is deeply buried, the second term is much smaller than the first term. Given the sample depth, the measured 26Al and 10Be concentrations, a knowledge of the nuclide production-depth function P(z), and the decay constants, this pair of equations can be solved to yield the surface erosion rate and the burial age. Granger (Reference Granger2006) gives further details, as well as a complete summary of the development and applications of burial dating.

$$\Lambda $$

is the effective attenuation length for spallogenic production (here taken to be 160 g/cm2). The first term on the right-hand side of these equations is the formula for the nuclide concentration in a steadily eroding surface, with a radioactive decay factor applied to correct it to the present time; the second term is the nuclide inventory produced at the sample depth during the period of burial. If the sample is deeply buried, the second term is much smaller than the first term. Given the sample depth, the measured 26Al and 10Be concentrations, a knowledge of the nuclide production-depth function P(z), and the decay constants, this pair of equations can be solved to yield the surface erosion rate and the burial age. Granger (Reference Granger2006) gives further details, as well as a complete summary of the development and applications of burial dating.

In solving Equations 1 and 2, we computed nuclide production rates attributable to spallation using the scaling scheme of Stone (Reference Stone2000), as implemented in Balco et al. (Reference Balco, Stone, Lifton and Dunai2008), and the production rate calibration data set described in Balco et al. (Reference Balco, Briner, Finkel, Rayburn, Ridge and Schaefer2009). This assumes that the 26Al/10Be production ratio for spallation is 6.75. We computed nuclide production rates attributable to muons using a MATLAB implementation, described in Balco et al. (Reference Balco, Stone, Lifton and Dunai2008), of the method of Heisinger et al. (Reference Heisinger, Lal, Jull, Kubic, Ivy-Ochs, Knie, Lazarev and Nolte2002a, Reference Heisinger, Lal, Jull, Kubic, Ivy-Ochs, Neumaier, Knie, Lazarev and Nolte2002b). However, we used revised muon interaction cross sections derived from depth profile measurements on an Antarctic sandstone core as part of the CRONUS-Earth project (Stone, J., personal communication, 2014). These cross sections are as follows: for 10Be, f*=0.0011 and σ0=0.81 μb; for 26Al, f*=0.0084 and σ0 =13.6 μb (these symbols correspond to those used by Heisinger et al.). The burial depth of our samples (7100 g/cm2) reflects the thickness (26.5 m) and rock density measured in hand samples (2.68 g/cm3) of the cave roof overlying the sample site. The mean elevation of the Ward Branch watershed upstream of the cave is 350 m. We used values of 4.99±0.043×10−7 per year and 9.83±0.25 ×10−7 per year for the 10Be and 26Al decay constants, respectively (Nishiizumi, Reference Nishiizumi2004b; Chmeleff et al., Reference Chmeleff, von Blanckenburg, Kossert and Jakob2010; Korschinek et al., Reference Korschinek, Bergmaier, Faestermann, Gerstmann, Knie, Rugel and Wallener2010).

We used a 10,000-iteration Monte Carlo simulation to estimate uncertainties in the burial ages. Table 5 shows internal and external uncertainties. Internal uncertainties include only measurement uncertainty in the nuclide concentrations. External uncertainties also include uncertainties in nuclide production rates, uncertainties in 10Be and 26Al decay constants, and a 5% uncertainty in the burial depth. By far the most significant uncertainties are measurement uncertainties in the nuclide concentrations and the uncertainty in the 26Al decay constant; others are minor by comparison.

Finally, we also incorporated the geologic constraint that our samples are stratigraphically ordered into the uncertainty estimate, by rejecting the results of Monte Carlo iterations that did not yield ages in the correct stratigraphic order. This generally follows the approach of Muzikar and Granger (Reference Muzikar and Granger2006), except that we used a Monte Carlo simulation instead of an analytical solution. As the burial ages of adjacent samples overlap within their uncertainties in all cases, this step results in a small adjustment of the most likely values for the ages, as well as a small decrease in the formal uncertainty of the ages, relative to the ages computed without considering the stratigraphic relationship of the samples (Table 5). We use these age estimates that take into account stratigraphic constraints in the subsequent discussion.

Several geologic processes could potentially violate our assumption of a two-stage burial history for these samples and thus introduce systematic errors into the burial ages. First, if the samples experienced a long period of burial elsewhere before being deposited in the cave, their 26Al and 10Be concentrations would not be in equilibrium with steady surface erosion. In effect, they would have a burial age greater than zero at the time they were buried at their present site. However, the geomorphic context of this site makes this possibility very unlikely; both Ward Branch and the James River are relatively small catchments that lack thick terraces or floodplain deposits in which sediment could be sequestered for a significant time before deposition in the cave. For example, the alluvium along Ward Branch upstream of the cave is uniformly less than 1 m thick. Cutbank exposures of the current James River floodplain upstream from Riverbluff Cave are also thin, typically with <2 m of alluvium above bedrock. Thus, there is little possibility of significant burial of the sediment before deposition within the cave.

Second, if sediment within the cave were eroded and redeposited, its burial age would reflect the time of initial entry into the cave rather than emplacement at its present location. Stock et al. (Reference Stock, Granger, Sasowsky, Anderson and Finkel2005), for example, invoked this possibility to account for discrepancies between burial ages and magnetic polarity in Sierra Nevada caves. However, the stratigraphy at Riverbluff Cave again renders this possibility unlikely because the sediment package is upward fining, reflecting the transition from active streambed deposition to slack-water (suspension) deposition. Later flows into the cave were apparently not competent to remobilize the sand-size grains used in the analysis. Additionally, the cave is relatively small and directly fed from river channels. Unlike previous studies, Riverbluff Cave is not an extensive cave system where upstream passages could contribute previously buried sediment to downstream passages. In summary, the geologic and geomorphic conditions of the cave support a simple two-stage exposure history for our samples. In addition, we argue later that the stratigraphic consistency among ages further renders the possibilities of prior burial and redeposition within the cave unlikely.

RESULTS AND INTERPRETATIONS

Paleomagnetism

Paleomagnetic measurements of the red clay (layers 3–5) are easy to interpret. Results from the gray silt (layer 8) are complex, but informative. Therefore, we first summarize results from layers 3–5 and then discuss at greater length measurements from the gray silt.

All samples from the red clay in layers 3–5 had a stable normal-polarity DRM (Table 3). Mean inclinations are close to the expected dipole value for this latitude (~56°), while declinations are close to due north with a small westerly deviation. Remanence directions were stable upon step demagnetization with consistent normal orientations. Vector-intensity plots (Fig. 5a) of the measured orientations are virtually straight lines trending toward the origin, indicating that a single magnetic remanence is present, and no underlying or secondary remanence was uncovered by either AF or thermal demagnetization. These samples had median destructive AF fields in the range of 10–15 mT, indicating a remanence carried predominantly by single-domain magnetite (or maghemite) grains, which are ideal for retaining a stable DRM. Moreover, the fact that the same remanence directions persist beyond peak demagnetization intensities of 40 mT means that this is not a viscous remanence acquired by relaxation of magnetic grains into alignment with the current magnetic field. IRM measurements (not shown) confirm that magnetite (or maghemite) is the principle magnetic mineral, as the samples are essentially saturated by 200–300 mT. AF demagnetization of these samples was nearly complete by 40–50 mT, also implying insignificant amounts of hematite or iron hydroxides that may form authigenically and record a secondary chemical remanent magnetization (CRM). Finally, thermal degmagnetization isolates magnetite as the remanence carrier. The normal polarity components persist above 500°C, but maghemite generally is destroyed (inverts to hematite) at lower temperatures, so the normal magnetization is not a secondary CRM produced by oxidation of magnetite to maghemite. In summary, all paleomagnetic evidence is consistent with deposition of the red clay during a normal-polarity magnetic field. Together with the biostratigraphic constraints, these results indicate that the red clay is almost certainly younger than the most recent polarity transition at ~0.77 Ma.

Figure 5 Vector-intensity plots illustrating demagnetization of Riverbluff Cave sediment. Units are those of magnetic intensity (A/m ×10−3). (a) Layer 3 (red clay), normal polarity. Demagnetization of this sample is typical of the laminated red clay (layers 3–5). (b) Layer 8 (gray silt), sample L8B1, mixed polarity. This sample has a normal declination (with a pronounced westerly component), but a reversed inclination. (c) Layer 8 (gray silt), sample L8C1, mixed polarity. This sample has a reversed declination with a normal inclination. H and V denote horizontal and vertical components of magnetization, respectively.

Table 3 Summary of paleomagnetic measurements, layers 3–5.

Notes: Inclinations and declinations are vector means of six samples, five demagnetized under alternating-field (AF) treatment and one with thermal. Individual inclinations and declinations are taken at the optimum demagnetization level (10 mT for AF and 350°C thermal) based on vector intensity plots and the reproducibility of measurements in multiple orientations. Principal components analyses of the individual samples’ demagnetization sequence give virtually identical orientations.

a Fisher precision parameter.

b The 95% confidence limit about the mean orientation.

c Number of samples per set.

Results from the gray silt (layer 8) are not as simple. First, the direction of magnetization is inconsistent within different samples, and second, stable components of both normal and reversed polarity are present (Table 4, Fig. 5b and c).

Table 4 Paleomagnetic results for layer 8.

Notes: Orientations for alternating-field (AF) samples are taken at the 10 mT demagnetization step, although these are essentially constant through each step. Orientations for thermal samples generally are taken at the optimum thermal demagnetization step of 350°C (see explanation in Table 3 and the text).

a Samples denoted by “PCA” (principal components analysis) had significant principal components, generally spanning demagnetization steps between 100°C and 500°C.

Of the initial six samples from layer 8, the five subjected to AF treatment did not demagnetize under peak fields up to 100 mT; this remanence is very hard and therefore cannot be attributed to magnetite or maghemite, leaving hematite or goethite (a proxy for various iron hydroxides) as the possible carrier. The intensity of the natural remanent magnetization of layer 8 samples was approximately one-tenth to one-twentieth that of the samples in the overlying red clay, which is a characteristic of a remanence carried by hematite or goethite. This difference is also consistent with lower bulk susceptibility values (a proxy measure of magnetite content) in the same ratio. Moreover, IRM curves for these samples do not saturate in fields exceeding 2000 mT, confirming a scarcity of magnetite/maghemite.

The sixth specimen of the initial set from layer 8 began to demagnetize under thermal treatment while uncovering a reversed magnetic remanence, but the plaster containing the sample disintegrated before demagnetization was complete. We therefore took six additional samples from the gray silt for thermal demagnetization. These samples demagnetized nicely, but with mixed orientations. Nearly all of these samples, however, revealed stable reversed components during demagnetization (Fig. 5b and c). Most inclinations of the thermally demagnetized samples from layer 8 are shallow, while declinations, whether normal or reversed, generally have a prominent westerly component. Stable remanence directions persist past 500°C during thermal demagnetization, which indicates that the remanence is carried by hematite, as goethite is destroyed (inverts to hematite) at lower temperatures. Therefore, the different polarity components are carried by hematite grains with similar coercivity and cannot be separated by stepwise demagnetization.

We speculate that any depositional remanence within the gleyed sediment of layer 8 was destroyed by intense postdepositional chemical reduction and concomitant iron-oxide dissolution (e.g., Karlin and Levi, Reference Karlin and Levi1985; Canfield and Berner, Reference Canfield and Berner1987). Simultaneously, a weak secondary CRM was acquired within mottles or afterward as oxidizing conditions were reestablished and authigenic hematite crystallized over an extended time spanning the Matuyama/Brunhes reversal. Under this scenario, the dominant polarity measured for any given sample would depend on local variation in the rate of crystallization before and after this reversal, and the shallow inclination of most samples would be the result of vector averaging of two opposite orientations within grains of comparable coercivity. Likewise, the declinations’ distinct westerly component would be the average of a reversed orientation in some grains and a normal orientation in others.

In summary, samples from the gray silt (layer 8) lack significant amounts of magnetite and apparently do not record a primary or depositional magnetic remanence. They do, however, retain a CRM carried by hematite with a mixture of both normal and reversed-polarity components. Nevertheless, the common preservation of stable reversed components indicates that layer 8 was subjected to a reversed-polarity field. Therefore, layer 8 and all subjacent strata should be >0.77 Ma old.

Burial dating

26Al-10Be burial ages range from 0.570±0.072 to 0.984±0.065 Ma (external uncertainties; see Table 5, Figs. 6 and 7). (Note that these ages are refined from initial estimates reported in a field guide [Rovey et al., Reference Rovey, Forir, Balco and Gaunt2010] using updated decay constants.) All burial ages are consistent with the stratigraphic order of the samples within respective error limits, and this age range spans the Matuyama/Brunhes polarity transition. The oldest age (0.984±0.065 Ma, layer 10) is indistinguishable from the younger boundary of the Jaramillo Normal Polarity Subchron (1.08–1.01 Ma). Thus, sediment deposition within Riverbluff Cave may have spanned additional magnetic reversals, although we did not attempt any paleomagnetic measurements below layer 8 because of the lack of fine-grained (cohesive) sediment.

Figure 6 26Al-10Be two-nuclide plot for Riverbluff Cave samples. This diagram is a graphic solution to the simultaneous Equations 1 and 2 in the text. The asterisks in the axis labels indicate that the measured nuclide concentrations are normalized to the surface 10Be and 26Al production rates. Note that axes are plotted on an arithmetic scale instead of the more usual logarithmic scale. For additional discussion of this type of diagram, see Granger (Reference Granger2006). The contours of age and erosion rate reflect subsurface nuclide production by muons at the present location of the samples, calculated as described in the text. Burial ages here are slightly younger than those in an earlier field guide (Rovey et al., Reference Rovey, Forir, Balco and Gaunt2010) because of the use of updated decay constants.

Figure 7 Results of Monte Carlo estimate of the uncertainty in the burial ages. Light gray histograms show uncertainty distributions for each burial age when each sample is considered individually. The black histograms show the uncertainty distributions when the stratigraphic relationship of the samples is taken into account by rejecting the results of Monte Carlo realizations that do not yield ages in stratigraphic order. All histograms are normalized to the same total area. Dotted line shows the Matuyama-Brunhes paleomagnetic boundary. As this figure is intended to show the relationship between the individual ages, it reflects measurement uncertainty only. Errors in production rates and/or decay constants would have the effect of shifting the entire array of ages together.

Table 5 26Al-10Be concentrations and burial ages for Riverbluff Cave sediments.

Note: The calculated burial ages here are slightly younger than those in an earlier field guide (Rovey et al., Reference Rovey, Forir, Balco and Gaunt2010) because of updated decay constants.

a Normalized to the Be isotope ratio standards of Nishiizumi et al. (Reference Nishiizumi, Imamura, Caffee, Southon, Finkel and McAnich2007).

b Normalized to the Al isotope ratio standards of Nishiizumi (Reference Nishiizumi2004b).

c Both internal and external (in parentheses) uncertainties are shown. Internal uncertainties include only measurement error in 26Al and 10Be concentrations. External uncertainties also include uncertainties in nuclide production rates and decay constants.

DISCUSSION

Burial ages are consistent with all paleomagnetic and biostratigraphic constraints discussed previously. The base of the red clay (layer 5, normal polarity) has a burial age of 0.570±0.072 Ma, and the underlying gravel (layers 6/7, polarity not determined) has a burial age of 0.658±0.065 Ma; both of these are younger than the Matuyama/Brunhes transition at 0.77 Ma. The upper portion of the gray silt (layer 8, with reversed remanence), which is immediately below the fossiliferous gravel, has a burial age of 0.823±0.064 Ma, which is slightly older than the same paleomagnetic datum, although indistinguishable from it given the uncertainty. As the magnetic samples from the gray silt all came from the lower two-thirds of this layer, the polarity transition could possibly be present within the uppermost portion. Burial ages for stratigraphically lower samples (layers 9 and 10) are significantly older than the datum.

In summary to this point, (1) the respective burial ages are in the correct stratigraphic order, and (2) the burial ages are consistent with our inference from the paleomagnetic data that the Matuyama/Brunhes datum lies between layers 5 and 8 or perhaps within the uppermost portion of 8. These results support the general validity of the geologic assumptions involved in computing burial ages. If either redeposition or preburial of the sediment had introduced significant systematic errors, a correct stratigraphic order and consistency with the magnetic boundary would be unlikely.

We conclude that the burial ages accurately represent the depositional age of the lower sedimentary sequence in layers 5–10. Sediment began to accumulate within the cave before 0.984±0.065 Ma. The oldest sediments are divided into an upper and lower channel facies by the gray silt (layer 8), a localized fine-grained layer dated at 0.823±0.064 Ma. This phase of sedimentation lasted until 0.658±0.065 Ma, when the channel-facies sequence was capped by the gravel beds that contain abundant vertebrate fragments, including horse and mammoth. These fossiliferous gravel beds extend to the Ward Branch paleoentrance; thus, that entrance was an active swallow hole at around 0.658 Ma but was abandoned because of incision thereafter. Today, the top of this paleoentrance is approximately 13 m above the active channel along Ward Branch, implying a long-term incision rate of about 20 m/Ma. At ca. 0.66 Ma, however, a high-discharge event(s) either transported a high concentration of vertebrate fragments into the cave from the Ward Branch drainage basin or reworked skeletal remains from individuals that died within or were dragged into the cave. The first possibility implies some sort of mass mortality along the Ward Branch channel. Regardless, these events occurred during the earliest Middle Pleistocene, apparently during Marine Oxygen Isotope Stage 16, which is generally considered to be one of the most intense glacial intervals during the entire Pleistocene (e.g., Lisiecki and Raymo, Reference Lisiecki and Raymo2005). Moreover, the burial age of host strata (the gravel layer) is indistinguishable from that of the last major Yellowstone eruption at ca. 0.64 Ma, and the distribution of deposits from this eruption (the Lava Creek B tephra) in adjacent states clearly implies that this ash should have reached Missouri (Izett and Wilcox, Reference Izett and Wilcox1982; Wilcox and Naeser, Reference Wilcox and Naeser1992). Given that ash falls are a notorious cause of mass mortality, landscape instability, and high-discharge fluvial events (the events inferred here), this bed should be examined systematically for evidence of volcanic materials. A tephrochronological datum within this sequence would also be an excellent means of further testing/verifying the accuracy of the burial dating method over this age range, as well as the assumptions specific to this study.

By 0.570±0.072 Ma (layer 5, base of the red clay), all Ward Branch entrances apparently were abandoned and backflow from flooding along the James River was the only significant source of detrital sediment for the cave. Alternatively, some of the red clay may have been deposited by floodwaters of Ward Branch that were ponded within the cave by high water above the James River entrance. Regardless, these events deposited a fining-upward sequence of laminated clay as both streams incised until floods could no longer reach the cave’s entrances. If the base of the red clay marks the beginning of entrenchment below the cave’s downstream entrance, which is about 9 m above the active floodplain, the implied long-term incision rate is between 14 and 16 m/Ma, somewhat lower than the 20 m/Ma estimate for the Ward Branch tributary.

In addition to burial ages, 26Al and 10Be concentrations in cave sediments provide an estimate of the erosion rate in their source watershed at the time of sediment emplacement (Granger, Reference Granger2006; Table 5, Fig. 6). Apparent erosion rates inferred from Riverbluff Cave samples are between 0.75 m/Ma (layer 10) and 1.83 m/Ma (layer 8), with highest erosion rates in the middle of the section (Table 5). These are similar to, but uniformly lower than, erosion rates inferred from burial dating of cave sediments elsewhere in the central United States (Granger et al., Reference Granger, Fabel and Palmer2001; Anthony and Granger, Reference Anthony and Granger2004), and they are comparable to preglacial erosion rates inferred from 10Be concentrations within buried paleosols in northern Missouri (Rovey and Balco, Reference Rovey and Balco2015). As the apparent erosion rate inferred from cosmogenic-nuclide concentrations in fluvial sediment represents a weighted average of the true erosion rate prevailing during the time the cosmogenic-nuclide inventories accumulated (Bierman and Steig, Reference Bierman and Steig1996; Schaller et al., Reference Schaller, von Blanckenburg, Hovius, Veldkamp, van den Berg and Kubik2004), the observed factor-of-two variation in apparent erosion rate implies a larger variation in true erosion rates. Alternatively, variation in apparent erosion rates may reflect differences in basin-averaged erosion rates in Ward Branch and the James River, combined with variations in the proportion of cave sediment derived from these sources. Nevertheless, cosmogenic-nuclide erosion rates reflect averages over the length of time to erode ~1 m of surficial materials. Therefore, as a rough approximation, the apparent erosion rates of about 1 m/Ma reflect averages from the Early Pleistocene to the early Middle Pleistocene. Thus, the Early–Middle Pleistocene landscape on the Springfield Plateau generally was quite stable with little topographic relief, as is still true for much of that province today. In contrast, the incision rates of ~14–20 m/Ma estimated here are much higher than the average erosion rate inferred from the concentrations of cosmogenic nuclides within grains eroded from the respective watersheds. The differences imply the beginning of marked entrenchment of the major streams and concomitant generation of topographic relief near the major valleys during the Early–Middle Pleistocene, presumably in response to the post-Pliocene drop in mean sea level.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Burial ages determined for five distinct strata that span the majority of the sediment sequence within Riverbluff Cave range from 0.984 to 0.570 Ma with 0.06–0.07 Ma uncertainties. All ages are consistent with the stratigraphic order of the samples, along with biostratigraphic constraints and the inferred position of the Matuyama/Brunhes paleomagnetic datum.

The cave sediment generally is a fining-upward sequence reflecting the transition from coarse-grained bed load (upstream, Ward Branch sources) to suspended load (downstream, James River source), as the rivers progressively entrenched beneath their paleoentrances. The elevation of these entrances above the active floodplains of both streams implies long-term incision rates of approximately 20 and 14–16 m/Ma for Ward Branch and the James River, respectively.

Deposition of channel-facies sediment began by 0.984±0.051 Ma, and coarse-grained sediment was deposited intermittently until 0.658±0.051 Ma. This long duration, which was interrupted by localized accumulations of silty “sump” deposits, likely reflects the contribution of sediment from various swallow holes along Ward Branch. The coarse-grained sediments are capped by highly fossiliferous gravel beds. The reason for the high concentration of vertebrate fossils, notably mammoth and horse, remains speculative, but their age is closely constrained at 0.658±0.051 Ma, which is indistinguishable from that of the widespread Lava Creek B tephra ejected during the last major Yellowstone eruption. It seems likely that the best possibility for preservation of this ash in the Missouri Ozarks is within the area’s abundant sinkhole basins and associated cave systems, such as Riverbluff Cave.

After deposition of the gravel beds and by 0.570±0.072 Ma, all Ward Branch entrances had been abandoned, and backflows from flooding along the James River were the only sources of detrital sediment. These floods deposited a fining-upward sequence of silt-rich and then clay-rich laminated red sediment. The age of the uppermost red clay, and thus the cessation of detrital sediment accumulation, is poorly constrained, because it lacks sand-sized grains that are necessary for the isotopic measurements required for burial dating. Additional U-Th dating of stalagmites partially buried within the upper clay may provide better control on the age of the upper red clay and the age of vertebrate fossils and trackways atop this sediment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Missouri Speleology Survey for help during this project and for providing a draft of Figure 1b. This project was supported by University Research Grant 1015-22-0832 from Missouri State University.