INTRODUCTION

Global warming is expected to increase the frequency and/or intensity of extreme precipitation and drought events (IPCC, 2013), particularly in the Mediterranean basin, including Morocco (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Pal and Giorgi2006; Giorgi and Lionello, Reference Giorgi and Lionello2008; Tramblay et al., Reference Tramblay, Neppel, Carreau and Najib2012). These variable hydrological conditions could significantly impact the water resources in the Moroccan Middle Atlas region (Bouaicha and Benabdelfadel, Reference Bouaicha and Benabdelfadel2010). For Morocco, this hypothesis has been tested for different climate scenarios. Using a set of regional climate models with a variable-resolution configuration, Driouech et al. (Reference Driouech, Déqué and Sánchez-Gómez2010) have forecast a decrease in mean precipitation over Morocco associated with changes in the distribution and intensification of extreme events for the period 2021–2050. The maximum drought duration is estimated to increase over most of the country, especially in the western regions of the Atlas Mountains (Driouech et al., Reference Driouech, Déqué and Sánchez-Gómez2010). The climate of the Middle Atlas region is influenced by air masses coming from the Mediterranean, Saharan desert, and Atlantic Ocean (Knippertz et al., Reference Knippertz, Christoph and Speth2003; Ouda et al., Reference Ouda, El Hamdaoui and Ibn Majah2005). Combined with a steep orography, this climate setting leads to a precipitation distribution characterized by high spatial variability, a pronounced seasonality, and a strong inter-annual variability (Ouda et al., Reference Ouda, El Hamdaoui and Ibn Majah2005). Most of the meteorological observations are only available for the last 40 yr, based on a station network particularly sparse in the Middle Atlas region (Driouech et al., Reference Driouech, Déqué and Sánchez-Gómez2010; Tramblay et al., Reference Tramblay, Neppel, Carreau and Najib2012, Reference Tramblay, Ruelland, Somot, Bouaicha and Servat2013). In this region, it is a key challenge to extend the hydro-climate dataset beyond the instrumental record period in order to understand the full spectrum of past hydrological variability.

Analysis of natural archives such as lake sediments can potentially give access to the pre-instrumental hydro-climate data. Several studies have already shown the usefulness of lake sediments in reconstructing paleohydrological conditions in association with rainfall-induced runoff (Czymzik et al., Reference Czymzik, Brauer, Dulski, Plessen, Naumann, von Grafenstein and Scheffler2013; Gilli et al., Reference Gilli, Anselmetti, Glur and Wirth2013). Sedimentological and geochemical analysis on the sedimentary sequences can provide past reconstructions of flood frequency (Giguet-Covex et al., Reference Giguet-Covex, Arnaud, Enters, Poulenard, Millet, Francus, David, Rey, Wilhelm and Delannoy2012; Lapointe et al., Reference Lapointe, Francus, Lamoureux, Saïd and Cuven2012; Wilhelm et al., Reference Wilhelm, Arnaud, Sabatier, Crouzet, Brisset, Chaumillon and Disnar2012, Reference Wilhelm, Arnaud, Sabatier, Magand, Chapron, Courp and Tachikawa2013; Czymzik et al., Reference Czymzik, Brauer, Dulski, Plessen, Naumann, von Grafenstein and Scheffler2013; Vanniere et al., Reference Vanniere, Magny, Wirth, Simonneau, Gilli, Joannin, Chapron and Anselmetti2013) as well as soil erosion (Simonneau et al., Reference Simonneau, Chapron, Vannière, Wirth, Gilli, Di Giovanni, Anselmetti, Desmet and Magny2013). Corella et al. (Reference Corella, Benito, Rodriguez-Lloveras, Brauer and Valero-Garcés2014) compared daily maximum precipitation with detrital microfacies observed in lacustrine sequences (thickness and occurrence) for the period 1917–1994 and reconstructed annual floods events recorded since the fourteenth century in the northeastern Iberian Peninsula. Such an approach derived from lacustrine paleoflood records calibrated with instrumental data can substantially improve the quality of long-term flood reconstructions (Wilhelm and Ballesteros-Cànovas, Reference Wilhelm and Ballesteros-Cánovas2016). Several issues remain on the understanding of hydro-sedimentary dynamics, however, and weaken the reliability of such records. The response of shallow lakes to hydrological variability modulates their water levels and impacts the amount and/or source of clastic materials filling the lake. Indeed, changes in the source-to-sink relationship also depend on the geomorphological setting of the watershed and should be considered for the reconstruction of hydrological events.

The Middle Atlas Mountains are considered the “Moroccan water tower,” with its catchment feeding the two most important rivers of the country: Oued Oum-Er-Rbia (555 km long) and Oued Sebou (456 km long), both flowing into the Atlantic Ocean. The region contains several natural lakes lacking any surface outlet, which act as natural pluviometers which are very sensitive to hydro-climatic variations (Benkaddour, Reference Benkaddour1993; Damnati, Reference Damnati2000, Reference Damnati2009). For example, sedimentological, geochemical, and mineralogical analyses of the Lake Iffrah sediments, a tectono-karstic lake situated ∼80 km northeast of Lake Azigza, reveal a lake-level drop interpreted as the result of successive dry periods over the past three decades, and eutrophication linked to human activity (Etebaai et al., Reference Etebaai, Damnati, Reddad, Benhardouz, Benhardouz, Miche and Taieb2012). Similar trends have been recorded in other lacustrine sediments of the Middle Atlas covering the same time interval (Damnati et al., Reference Damnati, Etebaai, Reddad, Benhardouz, Benhardouz, Miche and Taieb2012). Unfortunately, these studies are not based on the calibration of sedimentological proxies with hydro-climate data, and the lacustrine sequences are often subject to dating problems and low temporal resolution of the data.

This study is focused on short sediment cores retrieved in the deep basin of Lake Azigza in the Middle Atlas in 2013. Analyses of the elemental composition (X-ray fluorescence; XRF), microstructure, mineralogy, granulometry, and radionuclide dating of the sedimentary sequences were performed. These data combined with the geomorphological properties of Lake Azigza were used to identify relevant proxies of lake water level and runoff activity. For the interval dated with radionuclides (1963–2013), the sedimentary proxies are calibrated using regional hydro-climate data. Finally, the runoff activity and lake-level proxies are applied to the entire sequence to infer past hydrological changes over the last 134 yr.

Study site

The Moroccan Middle Atlas is an intracontinental mountain range, which exhibits a large synclinal trough extending 350 km along a northeast-southwest-oriented belt. The geology of the region is characterized by tectono-karstic systems, represented by calcareous dolomites deposited during the Early Jurassic, overlying Triassic mudstones (Martin, Reference Martin1981). Because of its high elevation and the influence of oceanic precipitation, the Middle Atlas has relatively cold and humid conditions and is considered a mountainous Mediterranean climate area with mean annual temperatures of about 12°C, and an annual precipitation of about 900 mm (Martin, Reference Martin1981).

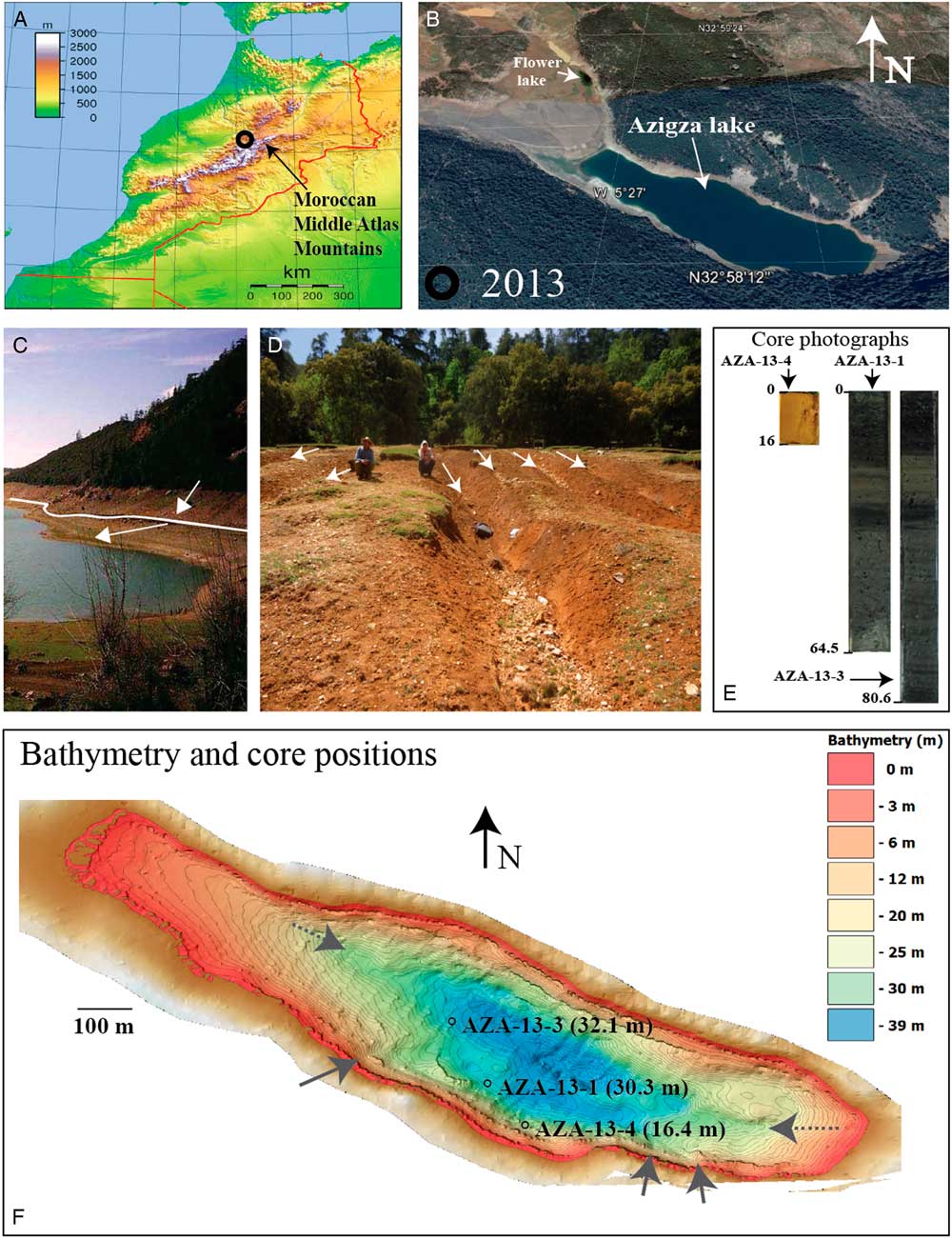

Lake Azigza (32°58′N, 5°26′W) is an endorheic and monomictic lake with tectono-karstic origin (Fig. 1A and B), located in the Moroccan Middle Atlas (1550 m above sea level). Nowadays, the lake has no surface outflow and occupies a unique depression with an area of about 0.55 km2 (measured in April 2013), having a maximum water depth of 42 m and a mean depth of 26 m (Fig. 1). Its catchment area is about 10.2 km2, covered by a green oak and cedar forest in the western part of the basin associated with the development of brunified fersialitic red soils (Flower et al., Reference Flower, Stevenson, Dearing, Foster, Airey, Rippey, Wilson and Appleby1989). Flower et al. (Reference Flower, Stevenson, Dearing, Foster, Airey, Rippey, Wilson and Appleby1989) also noted the low level of human disturbance in the watershed. The climate in this region is of Mediterranean sub-humid type, characterized by wet winters and dry summers with mean annual rainfall (MAP) of 900 mm (Martin, Reference Martin1981).

Figure 1 (color online) (A) Geographical position of Lake Azigza in the Moroccan Middle Atlas (black circle). (B) Photograph of the lake in 2013 (Google Earth). (C) Shorelines at the southeastern end of the lake. White line indicates highest visible limit between subaquatic and subaerial sediments next to the shorelines and white arrows highlight the shorelines inclination during low and high lake levels, respectively). (D) Gullies on the southern lake shore (white arrows). (E) Photographs of cores AZA-13-1, AZA-13-3 and AZA-13-4 showing core length (cm). (F) High-resolution bathymetry of the lake (derived from kriging method by interpolation on 150,000 points obtained with the Humminbird single beam sonar). Position of cores is indicated (black circle).

The region is characterized, however, by a strong inter-annual variability. For example, measurements obtained from a 4-yr meteorological-site-monitoring at Lake Azigza show that MAP is about 690 mm (Vidal et al., Reference Vidal, Rhoujjati, Adallal, Jouve, Bard, Benkaddour and Chapron2016). Over the past decades (1979–2015), MAP can differ by as much as 80% from the mean value (Vidal et al., Reference Vidal, Rhoujjati, Adallal, Jouve, Bard, Benkaddour and Chapron2016). Hydrological results from Lake Azigza indicate that water levels are linked to the precipitation regime (Vidal et al., Reference Vidal, Rhoujjati, Adallal, Jouve, Bard, Benkaddour and Chapron2016), a result that has been confirmed using hydrological mass balance modelling applied to Lake Azigza over the past 4 yr.

Previous studies have been conducted on the physicochemical and limnological properties of Lake Azigza (Gayral and Panouse, 1954; Flower et al., Reference Flower, Stevenson, Dearing, Foster, Airey, Rippey, Wilson and Appleby1989; Flower and Foster, Reference Flower and Foster1992; Benkaddour et al., Reference Benkaddour, Rhoujjati and Nour El Bait2008). Observations of paleoshorelines in the catchment indicate that multiple changes in lake level have occurred during the past few decades (Flower and Foster, Reference Flower and Foster1992).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Three short cores, AZA13-1 (64.5 cm), AZA13-3 (80.6 cm), and AZA13-4 (16 cm), were recovered in April 2013 in water depths of 30.3, 32.1, and 16.4 m, respectively, using a UWITEC gravity corer (63 mm diameter; Fig. 1E and F). High-resolution bathymetric profiles were performed using a Hummingbird 898c SI (83 kHz; bathymetry shown in Fig. 1F). All analyses were carried out at CEREGE laboratory (Centre de Recherche et d’Enseignement en Géosciences de l’Environnement, Aix-en-Provence), but some thin sections were prepared at EPOC laboratory (Environnements et Paléoenvironnements Océaniques et Continentaux, Bordeaux) and radionuclide measurements were performed at Géosciences laboratory (Montpellier).

Elemental composition and radiography

The ITRAX Core Scanner (Cox Analytical Systems) allows the simultaneous high-resolution acquisition of chemical composition of the sample by XRF scanning as well as the micro-variations in density and structure (microradiography; Croudace et al., Reference Croudace, Rindby and Rothwell2006). The positive X-ray signal obtained by radiography means that a darker image indicates denser sediment (Croudace et al., Reference Croudace, Rindby and Rothwell2006). Analyses of K, Si, Ca, Ti, Fe, Sr, and Mn, as well as the incoherent/coherent (inc/coh) ratio were performed on cores AZA-13-1 and AZA-13-3 with a 1-mm resolution and 15-s exposure time, using a Mo X-ray tube operating at 30 kV and 25 mA. The inc/coh value corresponds to the Compton to Rayleigh scattering ratio, representing the relative abundance between light and heavy elements (Croudace et al., Reference Croudace, Rindby and Rothwell2006; Chawchai et al., Reference Chawchai, Kylander, Chabangborn, Löwemark and Wohlfarth2016). The potential matrix effect on elemental XRF intensity was tested by comparing raw XRF elemental profiles with XRF intensity normalized against total counts. Since the main features of the elemental profiles are insensitive to normalization, we present elemental XRF intensity without the normalization.

Mineralogy

The mineralogical composition of the sediment was determined with an X-ray θ–θ diffractometer (X’Pert Pro MPD, Panalytical) using Co Kα radiation (λ = 1.79 Å), operated at 40 kV and 40 mA. Mineral phases were identified using the International Center of Diffraction Data PDF-2 database under the X’Pert Highscore plus software (Panalytical). Six samples (10-cm step) from core AZA-13-1 were ground in an agate mortar, providing powders that were placed on monocrystalline silicon plates cut parallel to the (501) face to ensure a very low background and absence of interfering diffraction peaks. These zero-background silicon plates were prepared with a droplet of ethanol to obtain a thin and homogeneous layer of powder. Statistical precision was improved by spinning the samples at 1500 rpm. A counting time of 22 s per 0.033° step was applied over a range 5–80° 2θ.

Clay minerals were separated from six bulk samples (at 10-cm intervals) taken from core AZA-13-1 using a sedimentation method according to Stokes’ law, after removing carbonates and organic matter with HCl (2M) and hydrogen peroxide (30 vol%), respectively. After ultrasonic disaggregation, the clay suspension was then deposited onto three glass slides to prepare oriented samples (for reference, ethylene-glycol saturation and heat treatment). Ethylene-glycol saturation was carried out on the oriented sample at ambient temperature in a glass desiccator to identify swelling clays (smectite or mixed-layer minerals containing smectite). The samples were heated in an oven at 490°C for four hours to distinguish kaolinite from chlorite.

Total organic carbon (TOC%) and total inorganic carbon (CaCO3%)

The total carbon (TC%) and total organic carbon (TOC%) contents were determined with a FISONS NA 1500 elemental analyzer. The protocol applied in this study follows the procedure of Pailler and Bard (Reference Pailler and Bard2002). Six samples (10-cm step) from core AZA-13-1 were desiccated in an oven for four days, and then ground and homogenized in an agate mortar. TOC% was measured after acid digestion to remove the carbonate fraction, and each sample was duplicated. Calcium carbonate contents were calculated using the following equation:

Laser diffraction grain size

The 14 samples (5-cm step) from core AZA-13-1 were fine grained, with a general grain size <63 μm. Organic matter was removed prior to analysis with hydrogen peroxide and dispersed using 0.3% sodium hexametaphosphate. The grain-size distribution was measured using a Beckman Coulter LS 13 320 laser granulometer with a range of 0.04 to 2000 μm. The calculation model uses the Fraunhöfer and Mie theories. All samples containing fine particles were thus measured at obscuration levels between 8 and 12% and between 45 and 70% with Polarization Intensity Differential Scattering. All samples show a bimodal grain-size distribution with modes centered on clays and silts (Supplementary Figure 1). In the following, results are shown for the clay fraction (<3 µm) and silt fraction (>3 µm).

Microfacies

Thin-section preparation

For core AZA-13-1, continuous thin sections were performed at EPOC. Sediments were subsampled using perforated aluminum slabs, before being dehydrated using the acetone-water exchange technique (Bénard, Reference Bénard1996; Zaragosi et al., Reference Zaragosi, Bourillet, Eynaud, Toucanne, Denhard, Van Toer and Lanfumey2006) and impregnated with an epoxy resin. After polymerization, resin-impregnated blocks were cut to obtain thin sections 10 cm in length, 4 cm in width, and 30 µm thick using a rotating lapidary unit.

For core AZA-13-4, thin sections were obtained at CEREGE. Sediments were subsampled with aluminum slabs and immersed in liquid nitrogen, before being lyophilized using the Lyophilisator CHRIST Alpha 1-2 LD plus. They were then impregnated with Araldite 2020 epoxy resin. Impregnated blocks were then cut to obtain sections 4.5 cm in length, 2.5 cm in width, and 30 µm thick using a rotating lapidary unit.

Microfacies characterization

The thin sections with dimensions of 10 × 4.5 cm were scanned using the EPSON 3200 PHOTO before analysis of microfacies under a Leica DM6000B instrument. Full motorization of the microscope stage (in X, Y, and Z) allows acquisition of a mosaic of several cm2. Microfacies were also analyzed by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). At the same time, a Si (Li) detector microprobe installed on the Hitachi S-3000N scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used for semi-quantitative elemental analysis. The generator was set at 15 kV, with an EDS acquisition time of 90 min. Elemental mapping (Si, Ca, Fe or Si, Ca, and K) of grains in the microfacies allows comparisons between the mineralogy and particle size of the sediment.

Age-depth model

Radionuclide activities of bulk sediment were measured on 13 samples from core AZA-13-3 between the top and 39 cm down core. Dating of sedimentary layers was carried out using 210Pb and 137Cs. These nuclides, together with U, Th, and 226Ra, were determined by gamma spectrometry at Géosciences Montpellier. Sediment subsamples from 1-cm-thick intervals were crushed after drying, transferred into small gas-tight polyethylene terephthalate tubes, and then stored for more than three weeks to ensure equilibrium between 226Ra and 222Rn. The activities of the nuclides of interest were measured using a Canberra Ge well detector and compared with the known activities of an in-house standard. Activities of 210Pb are obtained by integrating the area of the 46.5-keV photopeak. 226Ra activities are determined from the average of values derived from the 186.2-keV peak of 226Ra and the peaks of its daughter products in secular equilibrium with 214Pb (295 and 352 keV) and 214Bi (609 keV). In each sample, the 210Pb excess activities (210Pbex) are calculated by subtracting the 226Ra supported activity from the total 210Pb activity.

RESULTS

Age model

In core AZA-13-3, the 137Cs activity significantly increases at about 27 cm depth (Fig. 2). The Cs peak (200 mBq/g) is due to atmospheric nuclear tests and the associated radioactive fallout between 1962 and 1964 (Cambray et al., Reference Cambray, Playford, Lewis and Carpenter1989). Based on this peak event, a mean sedimentation rate of core AZA-13-3 is estimated at 0.54 cm/yr. The gradual down-core decrease of the 210Pbex activity (for the first 39 cm) suggests that the radionuclide signal is not affected by bioturbation (Fig. 2A). The Constant Flux/Constant Sedimentation (CFCS) model applied to the 210Pbex data yields a mean sedimentation rate of about 0.53 cm/yr. Since similar results are obtained from 210Pbex and 137Cs, we assume a constant sedimentation rate of 0.54 cm/yr during the last 50 yr (at 27 cm depth in core). The assumption of constant sedimentation rate is supported by the absence of drastic changes in grain size (clay, silt, and sand) along the entire core AZA-13-3 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2 Age-depth model for cores AZA-13-3 and AZA-13-1. (A) 226Ra, 210Pb, and 137Cs profiles in core AZA-13-3. The position of the identified peak of Nuclear Weapon Testing (NWT) corresponding to AD 1963 is indicated on the 137Cs profile. Sedimentation rates (CFCS) obtained from the 210Pb profile and the 137Cs peak. (B) Stratigraphic correlations between cores AZA-13-3 and AZA-13-1 based on K-XRF records. (C) Age-model of core AZA-13-1 derived from a CFCS model between 0 and 28 cm (2013-1963) using a mean sedimentation rate of 0.56 cm/yr, and linear interpolations between correlation points for the interval 28–63.5 cm (1963–1879).

Figure 3 Sedimentological and geochemical observations of core AZA-13-1.

From left to right: down-core distribution of facies; natural-light images of thin sections; core photograph; radiography; distribution of type 1, 2, and 3 microstructures (asterisks); Total organic content (TOC) % in bulk sediment and inc/coh ratio; CaCO3% content in bulk sediment and Ca-XRF intensity; PC2; Sr/Ti - XRF ratio; % silt fraction in sediment (black symbols indicate co-variation with TOC% at the base of the sequence, red symbols indicate co-variation with CaCO3%); % clay fraction in sediment, Fe-XRF, Ti-XRF, K-XRF, PC1, and Si-XRF. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The age-depth model for core AZA-13-3 was applied to core AZA-13-1 using the Analyseries software to correlate K-XRF intensities measured on both cores (Fig. 2B; Paillard et al., Reference Paillard, Labeyrie and Yiou1996). The correlation points based on the K-XRF profiles indicate a good correspondence between both records for the first 28 cm of the cores and a slight sediment compaction in core AZA13-1 after 28 cm to the base of the sequence (Fig. 2B). The age model, obtained considering a linear interpolation between these points, shows that core AZA-13-1 covers the last 134 yr (Fig. 2C), with a yearly (even slightly less) temporal resolution considering the XRF records.

Sedimentology

The lacustrine sedimentary facies are classified according to Schnurrenberger et al. (Reference Schnurrenberger, Russell and Kelts2003). The sedimentary sequences are composed of light-brown to dark, unconsolidated, matrix-supported, partly laminated clastic sediments and autochthonous carbonates. The term autochthonous carbonate refers to primary inorganic precipitation in the water column and post-depositional authigenic precipitation at the water-sediment interface and within sediment pore waters.

Core AZA-13-1

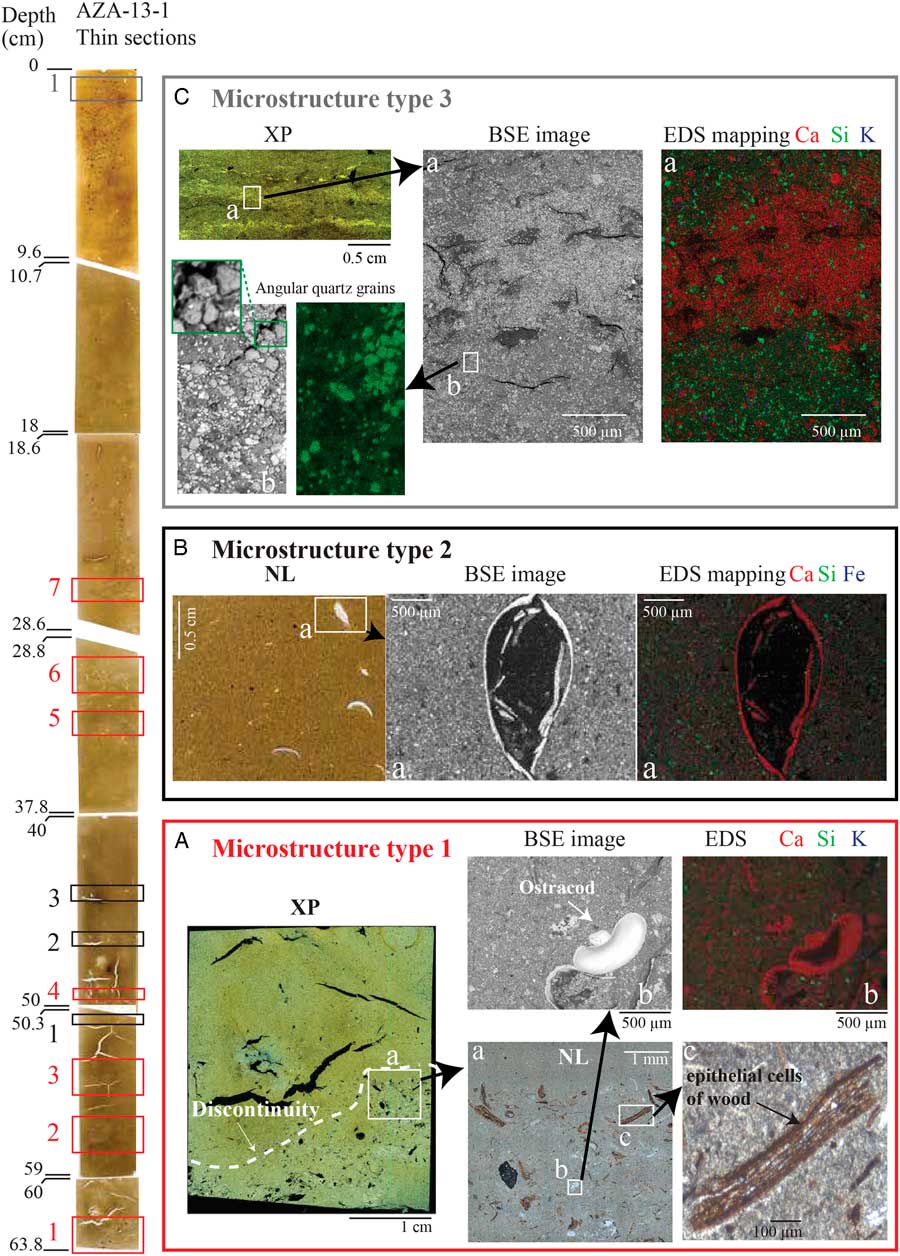

In core AZA-13-1, three facies are distinguished based on photographs, radiography (Fig. 3), and petrographic/SEM-EDS analyses (Fig. 4). Facies 1 is found at 64.5–55 cm and 29–16 cm, and is composed of light-brown sediments (Fig. 3) with several sub-horizontal discontinuous and mm-thick laminations (Fig. 4A). These laminations contain wood fragments, as shown by the presence of epithelial cells (Fig. 4A). Calcareous shells of ostracods and other bivalves are also present, as revealed by the SEM-EDS results (Fig. 4A). This facies is characterized by a high sediment density (Fig. 3, radiography image) and low inc/coh values (Fig. 3). Facies 2 is present within two depth intervals (55–29 and 16–5 cm; Fig. 3) and consists of homogeneous light-brown sediments composed of mm-sized bivalve and ostracod shells (Fig. 4B). The absence of laminations containing wood fragments is the main difference with Facies 1 (Fig. 4A and B). Also, the frequency of laminated layers in the down-core records varies between the different facies, with seven occurrences for type 1 called type-1 microstructures (T1M) against only three for type 2 (T2M; Fig. 4A and B). Facies 3 occurs only at the top of the core (between 1 and 5 cm; Fig. 3). It displays laminations, corresponding to the type 3 (T3M) with alternations of autochthonous carbonate layers and quartz-rich sediments (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4 (color online) Microscale observations of core AZA-13-1. On the left side, natural-light (NL) thin sections of core AZA-13-1 with down-core distribution of microstructures: type 1 (red rectangles), 2 (black rectangles), and 3 (grey rectangles). (A) Type-1 microstructures: cross-polarized light (XP) images showing discontinuity in sedimentary sequence. (a) Coarser materials are visible in NL image of the microstructure. Ostracods ([b] back-scattered electron [BSE] image) and (c) high amounts of wood fragments are present. Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping on indurated blocks (right hand side) shows calcitic shells of ostracods. The mapping is performed for Ca, Si, and Fe in each case. (B) Type 2 microstructures: NL image of thin section showing ostracod-rich layers. Note the absence of wood fragments in these structures and the large size of the calcitic bivalve shells. (C) Type 3 microstructures: XP image of thin section in the laminations at the top of the sequence. BSE image and EDS analyses of (a) laminations showing alternation of carbonate-rich and (b) detrital layers containing angular quartz grains.

Grain-size analyses of the total fraction of the sediment show that the sediment is mainly represented by silts (mean relative abundance of 73.5%), a result which is compatible with the trends observed in CaCO3% and Ca-XRF except in the basal part (Fig. 3). Carbonates are mainly calcite, with small proportions of dolomite and aragonite (Supplementary Figure 2). We consider that early diagenesis leading to calcite precipitation is negligible, since no sparitic cement is observed in either the petrographic or EDS analyses. The clay fraction (mean relative abundance of 26.5%) evolves in parallel with the contents of K, Ti, Fe, and Si (Fig. 3), and is mainly represented by interstratified clays, smectite, illite, and kaolinite (Supplementary Figure 3).

Core AZA-13-4

Because of their proximity to the shoreline, the sediments in core AZA-13-4 are coarser than in core AZA-13-1 (Fig. 5). AZA-13-4 is a short core containing brown unlaminated sediments with a coarse layer in the middle of the sequence. SEM analyses show that the sediment is mainly composed of detrital Si-rich minerals, of sand to fine-gravel grain size, with well-preserved or fragmented millimetric calcareous shells of ostracods and other bivalves (Fig. 5).

Figure 5 (color online) From left to right: photographs of core and indurated blocks, with SEM-EDS mapping of: (a and c) coarse detrital facies in middle of the sequence and (d and b) sand-sized detrital grains and calcitic shells of ostracods and other bivalves.

Geochemistry

In core AZA-13-1, XRF profiles show a co-variation between Fe and Ti (R 2 = 0.81; Table 1A) in close association with K (Fig. 3). The K and Si profiles are also strongly correlated (R 2 = 0.74; Table 1A) and show a similar variability with the clay fraction (Fig. 3). The inc/coh profile is almost a mirror image of the profiles of detrital elements (K, Si, Fe, and Ti; Fig. 3), displaying a co-variation with TOC% values except at the bottom of the core (Fig. 3). This may be due to the highly heterogeneous distribution of wood fragments in the sediment (Fig. 4A). The Ca contents co-vary with CaCO3% and the Sr/Ti ratio (Fig. 3). In general, Sr is enriched in aragonite, but the detrital fraction also contains terrigenous Sr. Similar depth-profiles of Ca, CaCO3%, and Sr/Ti are consistent with the mineralogical results indicating the presence of calcite and aragonite (Supplementary Figure 2). Apart from the interval between 64.5 and 48 cm, the carbonate phases show similar profiles compared with silt (Fig. 3).

Table 1 (A) Correlation coefficients (R) between X-ray fluorescence (XRF) elements used for the PCA for the entire AZA-13-1 sequence. (B) R of all elements in PC1 and PC2. The most significant R are indicated in bold.

Principal component analysis (PCA) is applied here to K, Si, Ca, Ti, Fe, Mn, Sr, and the inc/coh ratio. Elemental data is first centred to zero by subtraction of averages and then scaled with variance to give equal weight to each element (Weltje and Tjallingii, Reference Weltje and Tjallingii2008). PCA yields two main factorial axes (PC1 and PC2), which represent about 76.03% of the entire variability and allow us to distinguish three chemical end-members (Table 1A and Supplementary Figure 4A). PC1 is controlled by variations in the detrital elements Fe, Ti, Mn, K, Si, and Sr (first chemical end-member) and Ca (second chemical end-member). PC2 is controlled by Ca, which is itself anti-correlated with the inc/coh ratio (third chemical end-member); this ratio is a proxy of organic matter and water content in the sediment (Guyard et al., Reference Guyard, Chapron, St-Onge, Anselmetti, Arnaud, Magand, Francus and Mélières2007; Burnett et al., Reference Burnett, Soreghan, Scholz and Brown2011; Jouve et al., Reference Jouve, Francus, Lamoureux, Provencher-Nolet, Hahn, Haberzettl, Fortin and Nuttin2013). The correlation between Sr/Ti and Ca implies that carbonates primarily result from autochthonous precipitation. SEM-EDS analyses on microstructures type 1, 2, and 3 also support that carbonates are mainly originated from biogenic and endogenic precipitation (Fig. 4). The occurrence of dolomite indicates that minor contribution from detrital carbonates cannot be excluded (Supplementary Figure 2). The relatively low Rock-Eval hydrogen index values (HI = 310 mg HC/g TOC; Supplementary Table 1) in all samples suggest that the organic matter originates from a mixture of land-plant and algal production, and subsequently escaped remineralization during sedimentation (Carroll, Reference Carroll1998; Meyers, Reference Meyers2003). Organic matter is thus mainly derived from the catchment area (allochthonous). As a result, the opposite trend between Ca and inc/coh also supports the hypothesis that carbonates are mainly derived from autochthonous precipitation.

The relationships between the two main factorial axes of the PCA are compared with the identified sedimentary facies described previously. Facies 1 is characterized by a positive correlation between PC1 and PC2 (Supplementary Figure 4B), clay fraction, and CaCO3 content (Fig. 3). The inc/coh ratio decreases in this facies together with TOC values. The TOC content remains high at the base of the core due to the particularly high abundance of wood in the sediment. The geochemical signature of Facies 2 is characterized by a positive correlation between PC1 and PC2 (Supplementary Figure 4B), associated with lower PC1, PC2, clay fraction, and CaCO3 values (Fig. 3) and typically shows higher inc/coh ratio and TOC values. Facies 3 shows a negative correlation between PC1 and PC2 (Supplementary Figure 4B), but much higher PC1 and clay values, and lower CaCO3 and TOC values (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

Changes in lake level and runoff activity both have impacts on the source-to-sink processes leading to infilling of the lake. Geochemical, microstructural, and mineralogical analyses of the sediment provide crucial information to understand the link between hydro-sedimentary dynamics of the lake and precipitation regime.

In the following, we propose a proxy for runoff activity inferred from a combination of detrital elements (based on XRF intensity data) and a lake-level proxy derived from microstructural analyses. To assess the reliability of the proposed hydro-sedimentary indicators, the lake water level and runoff proxies are calibrated using regional hydro-climate data covering the past 50 yr corresponding to the interval dated with radionuclides (1963–2013). Then, we extend our approach to the entire sedimentary sequence, thus providing a hydrological reconstruction over the last century for the Middle Atlas region.

Hydro-sedimentary processes

Proxy of runoff activity

The presence of Fe, Ti, K, and Si-rich particles in core AZA13-1 is mainly associated with silicate minerals and clearly reflects the PC1 factorial axis (Table 1B). We therefore consider PC1 as an indicator of the detrital fraction of Lake Azigza sediments, which is closely linked to runoff activity in the catchment.

PC1 is related to quartz, kaolinite, illite, interstratified clays (probably illite/smectite), and chlorite (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). Detrital quartz grains are likely derived from sand-sized and altered Si-rich minerals detected in cores AZA-13-4 (core closer to the shoreline; Fig. 5), which are probably derived from Triassic sandstones (Martin, Reference Martin1981; Benkaddour, Reference Benkaddour1993). Potassium has been used as a proxy for clay minerals derived from soil weathering and erosion (Unkel et al., Reference Unkel, Björck and Wohlfarth2008; Cuven et al., Reference Cuven, Francus and Lamoureux2010; Kylander et al., Reference Kylander, Ampel, Wohlfarth and Veres2011; Hahn et al., Reference Hahn, Kliem, Oehlerich, Ohlendorf, Zolitschka and Team2014). This element is also associated with illite and chlorite minerals (Deer et al., Reference Deer, Howie and Zussman1992; Minyuk et al., Reference Minyuk, Brigham-Grette, Melles, Borkhodoev and Glushkova2007) that are detected in Lake Azigza sediments (Supplementary Figure 3). The similar trends shown by clays, K, and Ti indicate that the clay fraction is mainly derived from detrital inputs, and not from post-depositional processes, since Ti is mainly present in insoluble detrital particles (Demory et al., Reference Demory, Oberhänsli, Nowaczyk, Gottschalk, Wirth and Naumann2005; Jouve et al., Reference Jouve, Francus, Lamoureux, Provencher-Nolet, Hahn, Haberzettl, Fortin and Nuttin2013; Hahn et al., Reference Hahn, Kliem, Oehlerich, Ohlendorf, Zolitschka and Team2014). The presence of detrital minerals in Lake Azigza could also be linked to aeolian processes in addition to runoff activity since mass movement deposits are absent within the sediments. Microscopic observation of the detrital silt fraction reveals angular quartz grains (see an example in facies 3, Fig. 4C). This feature rules out the possibility of distal wind transport. Local winds could also transport detrital particles to the deep basin. At Lake Azigza, however, the wind intensity (∼4.3 km/h maximum) is probably not strong enough to mobilize a significant proportion of the detrital particles to the deep basin. Moreover, the silt fraction of the sediment is easily mobilized and maintained in suspension by the action of the wind (Tucker, Reference Tucker1991). In any case, the silt size fraction is mainly represented by autochthonous carbonates and not by detrital particles. Thus, we consider that runoff would have preferentially induced the transport of clays. The occurrence of small gullies (observed in the proximal catchment, Fig. 1D) incised into kaolinite-rich soils may have facilitated the mobilization of detrital clay particles during runoff activity.

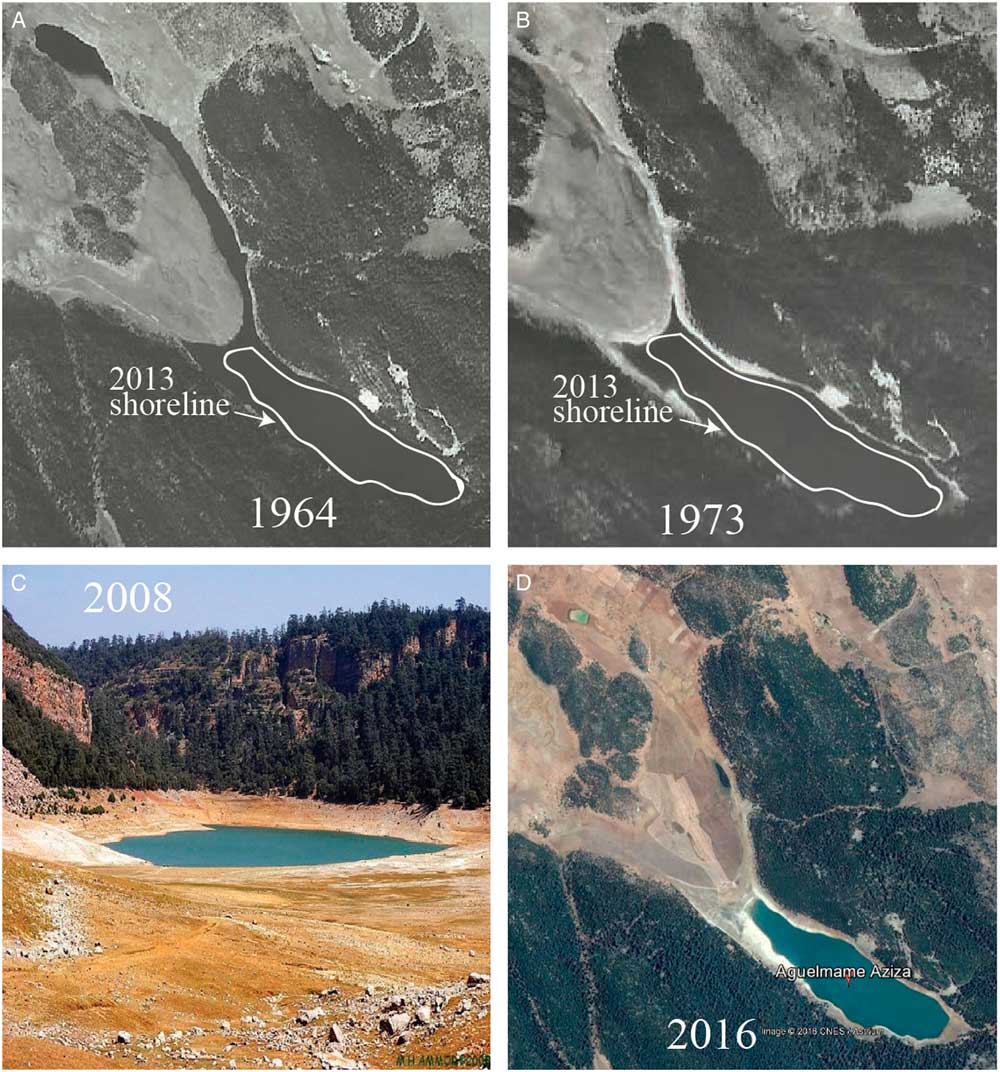

The main hydro-sedimentary process influencing the detrital sedimentation pattern can be described in two steps. First, increased precipitation causes a rapid rise in lake level (confirmed by measurements from a submerged probe and the meteorological station at Lake Azigza; Vidal et al., Reference Vidal, Rhoujjati, Adallal, Jouve, Bard, Benkaddour and Chapron2016). Second, the ensuing runoff carries more detrital particles with finer grain size, due to increased distal source materials and decreased availability of soil particles with the proximity of the forest. Other factors related to watershed-lake processes linking soil and vegetation dynamics may also influence detrital material available for the runoff. Rock-Eval HI values and mineralogical composition of the deep basin sediments suggest similar vegetation and soil conditions during the last century (Supplementary Figure 2). Aerial photographs of Lake Azigza over the past decades (1960s, 1970s, and 2000s; Fig. 6 do not reveal any drastic change in the cedar forest extent. Taken together, the available observations at Lake Azigza suggest that watershed conditions remained relatively stable over the study period, with negligible impact on the runoff activity.

Figure 6 (color online) Aerial photographs of the lake in (A) 1964 and (B) 1973 obtained from the National Agency of Land Conservation, Cadastre and Cartography, Rabat, Morocco. White lines correspond to the delimitation of shorelines in 2013. (C) Photograph of the lake in 2008 (view from the western side of the lake). The low lake level is marked by dewatering of the western shallow basin. (D) Google Earth satellite map of the lake in 2016.

Proxy of lake-level change

In core AZA13-1, microscale sedimentological analyses reveal two types of structures resulting from a high hydro-dynamic regime characterized by discontinuities and biological components derived from the shorelines (Fig. 4A). The first type (T1M, present in Facies 1) is characterized by fragments of ostracods, bivalves, and wood, while the second type (T2M, present in Facies 2) differs from the previous one by the absence of wood.

The basal coarse sand layers, associated with a fining-upward intermediate sequence and a top clay cap, are typical structures derived from hyperpycnal flows generated by floods, and have been described in several lakes in various geomorphological settings (Mulder et al., Reference Mulder, Migeon, Savoye and Faugères2001, Reference Mulder, Syvitski, Migeon, Faugères and Savoye2003; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Pollet, Chapron, Wessels and Wassmer2004; St-Onge et al., Reference St-Onge, Mulder, Piper, Hillaire-Marcel and Stoner2004; Chapron et al., Reference Chapron, Ariztegui, Mulsow, Villarosa, Pino, Outes, Juvignié and Crivelli2006; Guyard et al., Reference Guyard, Chapron, St-Onge, Anselmetti, Arnaud, Magand, Francus and Mélières2007; Wilhelm et al., Reference Wilhelm, Arnaud, Sabatier, Crouzet, Brisset, Chaumillon and Disnar2012, Reference Wilhelm, Arnaud, Sabatier, Magand, Chapron, Courp and Tachikawa2013; Corella et al., Reference Corella, Benito, Rodriguez-Lloveras, Brauer and Valero-Garcés2014; Jouve et al., Reference Jouve, Lisé-Pronovost, Francus and De Coninck2017). On the other hand, in their study of a shallow lake (30 m depth) with steep slopes, Corella et al. (Reference Corella, Benito, Rodriguez-Lloveras, Brauer and Valero-Garcés2014) were able to differentiate flood-induced turbidites from microstructures formed under lower-energy flow conditions. Turbidites and graded beds are associated with rainfall events under higher-energy hydrodynamic conditions than during the formation of discontinuous detrital layers.

In the Lake Azigza deep basin cores, there is no evidence for graded beds that could be related to flood-induced turbidites. Hence, the sedimentary structures are composed of different shoreline materials without any drastic change in grain size (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figure 1). This feature cannot be explained solely as being due to transport by low-density currents after a rainfall event. We need to consider the distance between the downstream gullies and the forest edge, which probably modulates the presence of wood fragments on the shoreline and their transport towards the deep basin. Wood fragments and biogenic carbonates (originating from the shoreline area) are present in Facies 1 (Fig. 4A). Facies 1 is also characterized by a high content of detrital proxies (PC1) and high sediment density (Fig. 3). During high lake-level stands, the shorelines are closer to the cedar forest, so the steeper slopes (Fig. 1C) increase the intensity of surface runoff in the lakeshore area and enhance transport to the deep basin. Consequently, the sedimentological and geochemical features of Facies 1 are interpreted as indicators of high lake-level stands. This observation is further supported by the abundance of diatoms and the composition of the assemblages, dominated by Cyclotella atomus and Cyclotella stelligera, which are indicators of freshwater inputs (Supplementary Figure 5).

Facies 2 shows sedimentary structures containing ostracods and other bivalve shells, but without wood fragments (Fig. 4B), i.e., these sediments have lower density and less abundant detrital minerals (Fig. 3). A reduced transport of detrital minerals to the deep basin is consistent with a decrease in runoff activity and can be linked to gentler slopes (Fig. 1C). In contrast to the interpretation developed for the high-energy sedimentary microstructures, Facies 2 can be related to low lake-level conditions. This is consistent with a decrease in the detrital fraction and a relative increase in organic matter (Fig. 3). In addition, Facies 2 is characterized by a lower abundance of frustules and/or assemblages dominated by Cyclotella spp., associated with benthic species (Supplementary Figure 5).

Calibration of the proxies

We now compare the geochemical signals with hydrological data. We use regional precipitation observations obtained from the Climate Research Unit (CRU) database. The geo-referenced CRU TS 3.22 dataset provides monthly precipitation on a grid with a spatial resolution of 0.5° in latitude and longitude centered at 5.75°W, 32.75°N for the period 1901 to 2013. This dataset compares well with the inter-annual variability of local precipitation, even if the monthly amount of precipitation is underestimated in the re-analysis of the data.

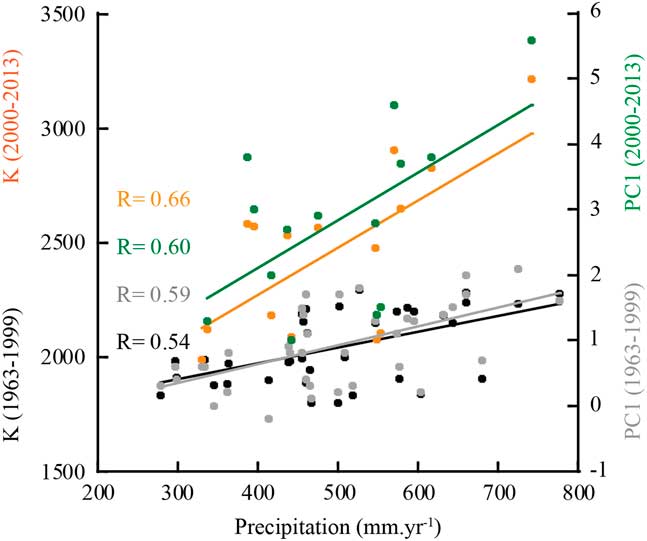

As a first step, we consider only annual precipitation from the CRU database for the period 1963–2013, which corresponds to the dated interval of the Azigza sedimentary sequences (Fig. 6A). Annual PC1 and K values are well correlated with annual precipitation (R = 0.59 and R = 0.54, respectively) for the period 1963–1999 (Fig. 8). During the 1960s and 1970s, precipitation is significantly above average values. This period seems to be associated with relatively high runoff activity (PC1). The increased runoff enhances the detrital input, favoring the presence of autochthonous carbonates and diluting organic matter in the sediment. During the 1980s and 1990s, precipitation, runoff activity, and autochthonous carbonates decreased, counter-balanced by an increase of organic content in the sediment (Fig. 3). From 2000 to 2008, the runoff signal rises drastically. This marked trend is accompanied by a short-term increase in monthly precipitation (Fig. 6A).

Our reconstruction is also consistent with lake-level indicators obtained from on-site measurements, historical aerial photographs, and earlier studies (Gayral and Panouse, 1954; Flower et al., Reference Flower, Stevenson, Dearing, Foster, Airey, Rippey, Wilson and Appleby1989; Flower and Foster, Reference Flower and Foster1992; Fig. 6 and 7). For example, the aerial photography from 1964 provides evidence of a high lake level, about 10 m above the 2013 level (our reference level; Fig. 6). During this period, the sediment is classified into Facies 1, corresponding to a high lake-level stand with increased runoff activity (Fig. 7). Flower and Foster (Reference Flower and Foster1992) estimated lake-level changes using the position of the shorelines between 1979 and 1984, as well as in 1990 (but no photographs are available). Compared to our reference level for 2013, we estimate that the lake level was about 3 m lower in 1990. Facies 2 is developed in the sedimentary sequence deposited at that time (Fig. 7), compatible with a low lake-level stand with a smaller distance between the coring site and the shorelines favoring deposition of coarser calcareous shells to the deep basin during rainfall events. The same observation can be made for the interval deposited in 2008, which records a major lake-level drop (Fig. 6C and 7).

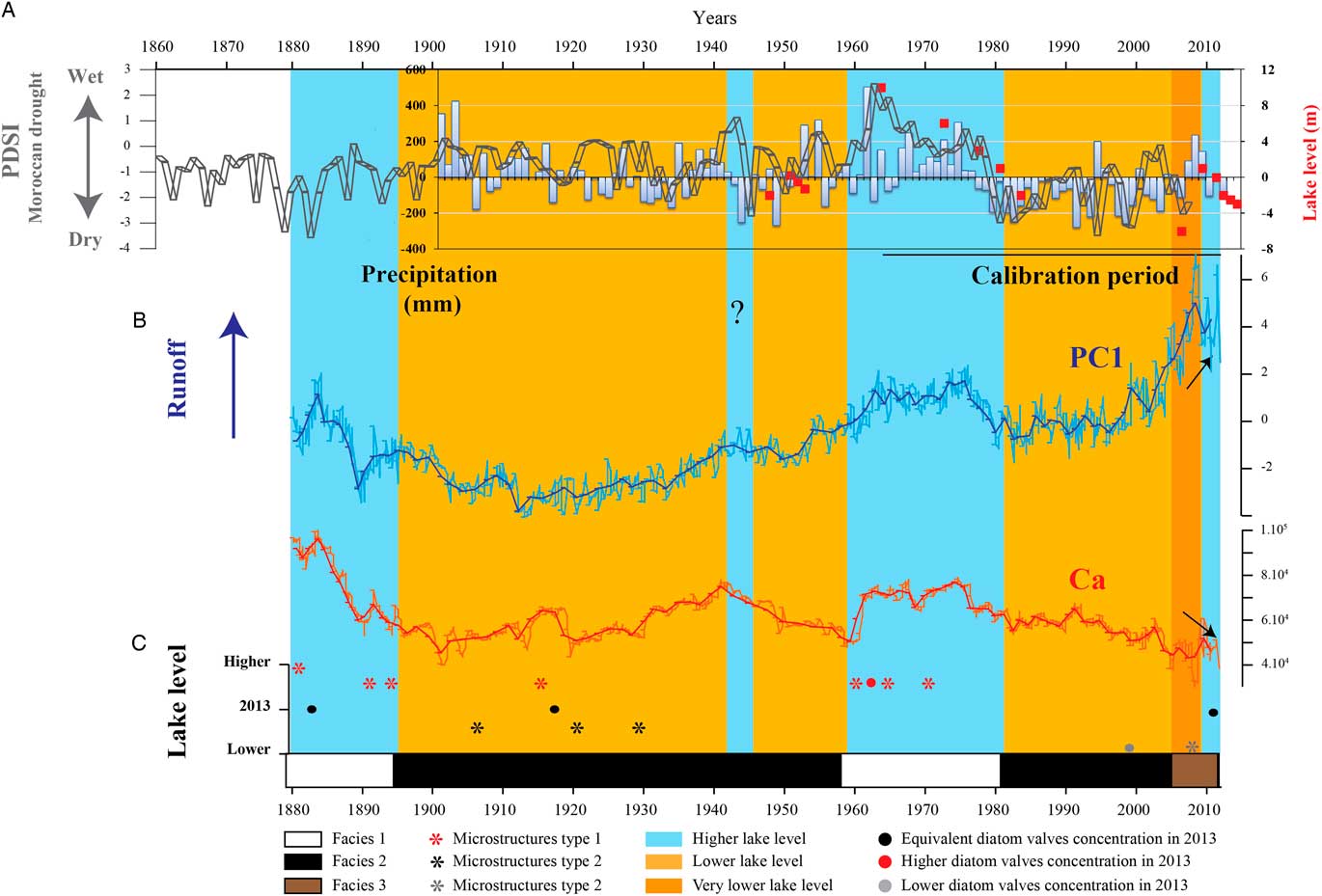

Figure 7 Runoff activity and lake water-level changes versus precipitation and drought severity index. Down-core distribution of facies from the bottom to top. (A) Annual precipitation CRU data (deviation from the mean calculated for the whole period 1901–2013). Lake level relative to the reference level of 2013 (red squares) derived from photographs available in Gayral and Panouse (1954), and lake-level measurements in Flower et al. (Reference Flower, Stevenson, Dearing, Foster, Airey, Rippey, Wilson and Appleby1989) and Flower and Foster (Reference Flower and Foster1992). Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) from Esper et al. (Reference Esper, Frank, Büntgen, Verstege, Luterbacher and Xoplaki2007) and Wassenburg et al. (Reference Wassenburg, Immenhauser, Richter, Niedermayr, Riechelmann, Fietzke and Scholz2013). Negative values reflect drier conditions and vice versa. (B) Ca and PC1 values (units expressed in factor scores) derived from AZA-13-1 age model. Assuming a mean sedimentation rate of about 0.56 cm/yr, the moving average of six measurements records the inter-annual variability. Black arrows highlight opposite trend for PC1 and Ca. (C) Position of lake-level indicators: type 1, 2, and 3 microstructures (asterisks) and diatom valve concentrations compared to 2013. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The high-resolution lake bathymetry clearly documents the hydro-sedimentary dynamics associated with low lake levels and the occurrence of paleochannels in the northwest and southeast parts of the deep basin (Fig. 1F). Isobath structures highlight three submerged channels (grey arrows in Fig. 1F) situated between 0 and 25 m depth, which were probably reactivated during the recent 2008 lake-level drop. Two deeper and larger submerged channels (dotted grey arrows in Fig. 1F) between 20 and 30 m depth, provide evidence of past lake-level drop(s) of much greater amplitude than in 2008.

At the top of the sequence, T3M correspond to the period shortly following the drastic drop in lake level in 2008 (about 7 m, Fig. 6 and 7). This drop is consistent with a decrease in runoff activity and precipitation during the 1990s and early 2000s (Fig. 7). Laminae of autochthonous carbonates are intercalated with laminae of coarser detrital grains (Fig. 4C), and are interpreted as annual laminated deposits (varves). The presence of autochthonous carbonates in the sediment is no longer linked to the runoff, but appears to be associated with supersaturated conditions in the water column during the spring/summer. Facies 3 has a geochemical signal marked by an anti-correlation between PC1 and PC2 (mostly Ca; R = −0.77; Supplementary Figure 4B), which indicates hydro-climate conditions are recorded differently in lake sediments during the 2000s. Facies 3 is coeval with a strong increase in PC1 index (Fig. 7). Nevertheless, the interval (2000–2013) is still characterized by a correlation between PC1 and precipitation (R = 0.6), but with an increase in the slope of the regression line (Fig. 8). The runoff proxy is linked to the availability of detrital materials due to enhanced erosional potential combined with drier conditions. The lake-level decrease of 8 m between 1979 and 1984 (Fig. 7), resulted in an increase of erodible surface area that could supply the lake with detrital materials. In a context of low lake-level conditions, the sensitivity of the proxy to precipitation variability is enhanced. The drastic lake-level drop is also consistent with the presence of a quasi-monospecific diatom assemblage dominated by Cyclotella ocellata, a species that is potentially very well-adapted in the context of a nutrient-depleted water column (Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 8 Annual K-XRF and PC1 versus precipitation for the period 1963–1999 (black and grey symbols and associated regression line) and for the period 2000–2013 (orange and green). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The Ca record Follows the PC1 index. Hence, PC1 is conditioned by two chemical end-members (detrital inputs and autochthonous carbonates; Supplementary Figure 4A) that are linked. In shallow waters close to the lake shore, supersaturated conditions systematically lead to the precipitation of autochthonous carbonates (aragonite and calcite; Supplementary Figure 2; Benkaddour, Reference Benkaddour1993, 2008). During rainfall events, autochthonous carbonates present in the drawdown zone and detrital carbonates from the watershed can be mobilized by the runoff and supplied to the deep basin. The more the runoff, the higher the carbonates in lake sediments. On the other hand, the increased influx of Ca2+ ions and nutrients due to higher surface runoff could favor the precipitation of autochthonous carbonates, as suggested by Brauer et al. (Reference Brauer, Mangili, Moscariello and Witt2008). While autochthonous carbonates in lacustrine sediments are generally used as a proxy of drier conditions (e.g., Damnati et al., Reference Damnati, Etebaai, Benjilani, El Khoudri, Reddad and Taieb2016) and warmer climate (Meyers, Reference Meyers2003), at Lake Azigza, carbonates are primarily related to higher runoff activity under wetter conditions. When the response of the runoff proxy is enhanced due to increased erodible surface in the 2000s, however, Ca is diluted by the large amount of the detrital elements (Ti, Fe, Si, Sr, Mn, and K) and diverges from PC1. The correspondence that exists between Ca and lake level during high lake level is not anymore valid when erosional potential is high. This is why the Ca record cannot be used as lake-level proxy.

Paleohydrological reconstructions since 1879

In the following section, we apply our age model to the entire sedimentary section of core AZA13-1.

The PC1 proxy indicates high runoff activity between 1880 and 1895 (Fig. 7). The T1M present in Facies 1 are composed of thick layers with a large amount of material derived from shorelines close to the forest (Fig. 4A). During this period, the diatom assemblage indicates increased freshwater inputs and a high lake-level stand (Supplementary Figure 5). After 1900, the Lake Azigza sedimentary sequence is dominated by the deposition of T2M (Fig. 4B), suggesting lower lake levels. From 1900 to the 1950s, the runoff activity is low (Fig. 7). During the first half of the twentieth century, the diatom assemblage is dominated by benthic species of Cyclotella, which suggests a lower lake-level context. At the beginning of the 1960s, the runoff activity becomes higher and remains stable until the beginning of the 1980s. Several T1M are developed during the 1960s (Fig. 7), which argues in favour of a higher lake level. During the 1980s and the 1990s, the runoff activity is low. The absence of microstructure indicates that the runoff intensity is also substantially reduced. After the mid-1990s, the runoff activity increases gradually (Fig. 7). In the 2000s, and for the first time in the entire sequence, divergent trends are observed between the runoff activity and carbonates (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figure 4B), which suggests a shift in the hydro-sedimentary dynamics. Higher detrital input to the deep basin leads to a dilution of carbonates and organic matter in the sediment. From the beginning of the 1980s, we can also observe rapid fluctuations in the runoff activity proxy. These rapid bursts in runoff activity could reflect an increase in the inter-annual hydrological variability and/or in the erosional potential since the 1980s, both participating to increase the sensitivity of the runoff proxy. The occurrence of T3M between 2008 and 2010 also highlights recent and rapid shifts in the hydro-sedimentary dynamics linked to significant hydrological changes in only 2 yr (Fig. 7A). This result suggests that, when compared to the last 134 yr, the major dry periods occurred since the beginning of the 2000s.

In the present study, we compare the lake sediment records with re-analysis of hydro-climate data (CRU) for the period 1901–2013 (Fig. 7). We also use the updated Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) covering a longer period (Esper et al., Reference Esper, Frank, Büntgen, Verstege, Luterbacher and Xoplaki2007; Wassenburg et al., Reference Wassenburg, Immenhauser, Richter, Niedermayr, Riechelmann, Fietzke and Scholz2013). For the period 1879 to 1901, the PDSI reconstruction shows negative values indicating dry conditions (Fig. 7). This apparent discrepancy with our sedimentary proxy results could be due to uncertainties in the age model at the base of the sequence of core AZA-13-1 subjected to compaction effect due to coring processes. When using the CFCS model for the entire core, the age at the bottom is 1899 instead of 1879. Close similarities in the K-XRF records from both cores AZA-13-3 and AZA-13-1, however, rather reinforces the age of 1879 at the base of sequence. It is also likely that the PDSI, a compilation of tree-ring width data from the Rif as well as the middle and the High Atlas, reflects a regional hydro-climate signal. After 1900, PDSI and CRU data show approximately similar trends (Fig. 7). Negative PDSI values between the 1900s and the 1950s suggest dry conditions with some fluctuations, which agrees with our interpretations. At the beginning of the 1960s, the lake level rises by about 10 m in comparison with levels for the mid-1950s (Fig. 6 and 7). Precipitation and PDSI reach their highest values of the last 134 yr, indicating much wetter conditions leading to high runoff activity.

Runoff activity decreases at the beginning of the 1980s, when lake level, PDSI, and precipitation are minimal (Fig. 7). In the mid-2000s, the hydro-sedimentary dynamics of the lake reaches a tipping point as discussed in the previous section. This shift is supported by a strong increase of the PC1 (and K) for the period 2000–2013 (Fig. 8). The dry period from the 1990s onwards seems to end with an exceptionally low lake level in 2008. The occurrence of several dry episodes at the end of the twentieth century have been also inferred from PDSI reconstructions (Esper et al., Reference Esper, Frank, Büntgen, Verstege, Luterbacher and Xoplaki2007). Although higher precipitation led to higher lake levels between 2009 and 2012, the level has dropped by about 3 m since 2013 (Fig. 6 and 7; Vidal et al., Reference Vidal, Rhoujjati, Adallal, Jouve, Bard, Benkaddour and Chapron2016). Consequently, the lake area appears to have been affected by several dry periods since the middle of the 1990s. These drier conditions could be the precursor signs of the impact of ongoing climate change on the precipitation regime in regions around the southern periphery of the Mediterranean, as expected for the twenty-first century (IPCC, 2013).

Earlier studies on deep-water sediment cores from Lake Azigza (Flower et al., Reference Flower, Stevenson, Dearing, Foster, Airey, Rippey, Wilson and Appleby1989) failed to yield satisfactory paleohydrological reconstructions mainly due to the low resolution of the geophysical and chemical dataset and the macro-scale approach of the sedimentological observations. Other studies on Middle Atlas lake sediments (Ifrah, Iffer, and Afourgagh; Damnati et al., Reference Damnati, Etebaai, Reddad, Benhardouz, Benhardouz, Miche and Taieb2012) suggest that wetter conditions prevailed in the early twentieth century, followed by unstable conditions between 1920 and 1965. After 1965, however, it is difficult to assess the impact of climatic versus human factors on past lake levels and on the hydro-geochemistry.

The methodological approach used here is applied to the sedimentary record of a lake with minor human disturbance, calibrated against past lake-level changes and regional precipitation data. By considering changes in the sedimentary facies together with lake-level fluctuations, we present evidence for variations in the hydro-sedimentary dynamics of Lake Azigza over the last 134 yr. This study improves our understanding of a lake-sediment record mainly controlled by detrital inputs and autochthonous carbonates with limited post-depositional processes, reflecting past hydrological variability at inter-annual to decadal time scales. As such, our study contributes valuable insights for the interpretation of lake infill sequences and can be applied to a wide range of lacustrine systems that exhibit substantial water-level fluctuations.

CONCLUSIONS

We show that the Lake Azigza sedimentary record is useful for studying the hydrological variability of the Middle Atlas region. Based on microfacies and XRF elemental analyses of the sediments, we provide proxies of runoff activity and lake-level changes. The onset and duration of the response to drier and wetter periods at the Lake Azigza site is well-represented by detrital element contents (K, Si, Ti, and Fe) that are considered as proxies of runoff activity. The sedimentary facies have specific geochemical signatures attributed to hydro-sedimentary processes (related to variable runoff activity) during high- and low lake-level periods. These lake-level changes are inferred from sediment microstructures linked to the runoff intensity and distance from the shoreline.

During high-precipitation periods, the surface runoff is increased, associated with a rise in the lake water level, implying that more detrital minerals and runoff-induced autochthonous carbonates are transported to the deep basin of the lake.

The sedimentological proxies are calibrated with regional hydro-climate data for the period 1963–2013 and then interpreted for the last 134 yr. The sediment record faithfully reproduces the hydrological fluctuations observed since 1879 at decadal scales. We show that the sensitivity of the PC1 index is increased after periods of drought (e.g., low lake level). The strong response of the runoff proxy for the last decade suggests that the major low lake level reached in 2008 could be the first sign of increased drought duration expected for the period 2021–2050 in the Middle Atlas Mountains. Moreover, calibration of dated sediment sequences with local precipitation data is crucial for understanding the complex hydro-sedimentary dynamics of lacustrine systems and developing reliable proxies of hydrological variability.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Among the staff at CEREGE, we particularly thank D. Borschneck for XRD analysis; D. Delanghe for grain-size sample preparation and useful discussions; J. Longerey and B. Devouard for thin-section preparation; F. Rostek for TOC% and CaCO3% measurements; M. Garcia for XRF measurements; and P. Roeser for helpful advice on lacustrine carbonates. The SETEL-CEREGE is warmly acknowledged for logistic support. S. Zaragosi is acknowledged for his support at the EPOC Laboratory. R. Boscardin is acknowledged for her support with Rock-Eval pyrolysis at ISTO Laboratory. This work is a contribution to Labex OT-Med (No. ANR-11-LABX-0061; PHYMOR project) and has received funding from Excellence Initiative of Aix-Marseille University - A*MIDEX, a French “Investissements d’Avenir” programme. This study was also funded by MISTRALS/Paleomex projects.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/qua.2018.94