INTRODUCTION

Earth's Critical Zone (CZ) is the “heterogeneous, near-surface environment in which complex interactions involving rock, soil, water, air, and living organisms regulate the natural habitat and determine the availability of life-sustaining resources” (NRC, 2001). The concept of the CZ as a means to integrate studies of the near surface terrestrial environment on planet Earth was introduced in 1998 (Ashley, Reference Ashley1998) and formalized in a National Research Council Report (NRC, 2001). It is now applied globally.

The CZ is the outer skin of Earth's surface recording the collective impacts of the atmosphere, cryosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere and pedospheres on the lithosphere by weathering (Amundson et al., Reference Amundson, Richter, Humphreys, Jobbagy and Gaillardert2007). Most CZs begin at the top of the plant canopy and extend down through the vadose zone into the groundwater, where biogeochemical mediation of biotic and abiotic reactions occur (Amundson et al., Reference Amundson, Richter, Humphreys, Jobbagy and Gaillardert2007; Chorover et al., Reference Chorover, Kretzschmar, Garcia-Pichel and Sparks2007; Akob and Küsel, Reference Akob and Küsel2011). Various chemical gradients exchange matter and energy with the Earth system through space and time (Brantley and Lebedeva, Reference Brantley and Lebedeva2011). Processes acting in the CZ are affected by both: (1) the internal dynamics of that system, e.g., mantle convection, volcanism, and earthquakes; and (2) the external dynamics such as climate change and now anthropogenic forcing (TRANSITIONS, 2012).

To understand the full range of processes operating during the Quaternary Period, we need to understand how the CZ operates today (modern environmental studies). In the USA, National Critical Zone Observatories (CZO), 2007–2020, with 12 natural laboratories located in a variety of geological settings was an extremely successful NSF-funded program involving thousands of scientists, have produced a plethora of publications with continued output expected for years to come (Criticalzone.org,01/05/2020). There are also CZOs in China and Europe and they too mostly focus on modern processes. Ancient CZs may have responded in the past to different climatic and biotic states. To understand the full range of processes operating during the Quaternary Period, studies also need to focus on the buried CZs (Paleo Critical Zones, or PCZs) that archive the geological record. However, researchers need to be aware of those environmental settings such as terraces whose records can be overprinted or that might develop as palimpsests. The state of being “buried” is key here as PCZs must be isolated from modern processes to maintain the integrity of the ancient environmental record.

PCZs are time slices that capture aspects of the: hydrosphere (e.g., precipitation amounts, seasonality records, groundwater discharge zones); atmosphere (pCO2 and pO2); biosphere (e.g., organic molecular biomarkers, plant and animal remains); and lithosphere (e.g. bedrock, lava flows, clastics, soils). Tracking change from one PCZ to the next through geological time can, therefore, provide an integrative history that is robust and more comprehensive than the individual records would yield.

CZs are all-inclusive. They are more than just soils. Similarly, PCZs are more than just paleosols. The CZ research framework is a wide-ranging approach that has the ultimate goal of learning about the totality of conditions from the top of canopy to the bottom of the weathering zone. There exists a large community of scientists that has been active for decades conducting research using proxies and physical remains to interpret the environmental and climate records archived in sediments. Paleoenvironmental reconstruction is a form of PCZ research, but using different terminology. The contribution of PCZs is crucial to our understanding of Earth surfaces processes. However, many studies were narrowly focused on specific and often limited objectives. The PCZ framework ideally integrates every aspect of ancient records. The deposits can now be looked at with new and innovative ways.

Identifying and distinguishing competing influences in PCZs remains a major challenge. Preservation of the signatures of various contributing factors is subject to complexities of subsequent weathering and especially erosion, but significant records of hydrosphere, biosphere, atmosphere, lithosphere and pedosphere, can be preserved and provide the evidence needed to interpret the CZs of the Quaternary Period through time and space. The objectives of this paper are:

1. Demonstrate the relevance of CZ concepts to interpret the sedimentary record of the Quaternary preserved in PCZs.

2. Extract paleolandscape, paleoenvironment, paleoecology and paleoclimate records of “time slices” recorded in PCZs.

3. Demonstrate application of PCZs to human origin research using case studies: i) Early hominins (Homo habilis); and ii) Native Americans (Homo sapiens).

4. Open a discussion of Proto (i.e. abiotic) Critical Zones on rocky bodies of the Solar System, such as Mars that appear to lack an extant biosphere.

THE CRITICAL ZONE CONCEPT

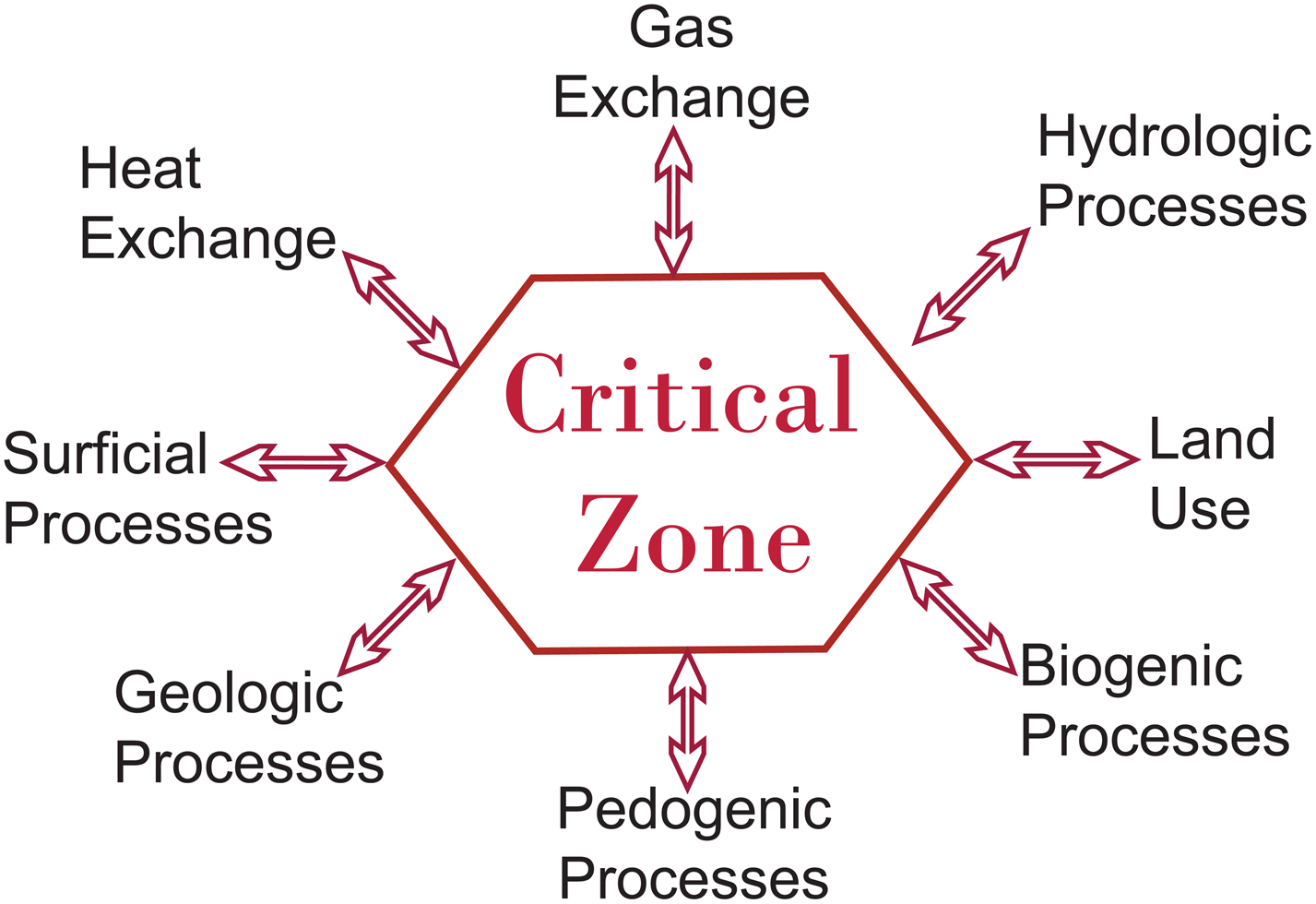

Earth's CZ as first defined in the NRC report (NRC, 2001) extends from the atmosphere at the top of the canopy through bedrock to the limit of weathering, although, the physical characteristics of this lower boundary are controversial (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, von Blanckenburg and White2007; Brantley et al., Reference Brantley, Megonigal, Scatena, Balogh-Brunstad, Barnes, Bruns and Van Cappellen2011). Tectonic processes at depths may create fractures well below the base of the CZ that locally focus groundwater and affect weathering, geomorphic processes and landform development (Molnar et al., Reference Molnar, Anderson and Anderson2007; Riebe et al., Reference Riebe, Jesse Hahm and Brantley2017). The characteristics of individual PCZs are determined by chemical reactions triggered by gasses in the atmosphere, heat from the sun, or simply the presence of water or perhaps microbial forms of life? The CZ as originally visualized was a way to integrate the research of the four scientific spheres (lithosphere, hydrosphere [including cryosphere], biosphere and atmosphere) at the surface of Earth and to study the linkages, feedbacks and record of processes. Thus, the CZ concept represents the spirit of system science. Rather than closeting studies by a variety of disciplines into their respective pigeonholes the CZ perspective provides the holistic framework from which the tendrils of improved understanding can radiate outward to new disciplines and/or feedback into the component disciplines. The CZ includes the ocean bottom, lake bottoms, land beneath glaciers, forests, deserts, floodplains and volcanoes (Ruddiman, Reference Ruddiman2000). (Fig. 1). Aquatic environments have not been included in most CZ research, but they should be considered part of this research. Wetlands, lakes, coastal zones and the ocean are fundamental parts of Earth's CZ.

Figure 1. Earth's CZ is the heterogeneous, near-surface environment in which complex interactions of the major components of the climate system, i.e., rock, soil, water, ice, air, and living organisms force and responded to climate variations (Ruddiman, Reference Ruddiman2000). The CZ is the interface between the lithosphere and hydrosphere, cryosphere and atmosphere.

From the onset, the CZ was often equated by the scientific community to soil development and pedogenic processes (Wilding and Lin, Reference Wilding, Lin, Lin, Bouma and Pachepsky2003; Derry and Chadwick, Reference Derry and Chadwick2007; Alekseeva et al., Reference Alekseeva, Kabanov, Alekseev, Kalinin and Alekseeva2016). Paleopedologists and hydrologists have contributed hugely to our understanding of CZ processes, e.g., the work of Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Bouma, Pachepsky, Western, Thompson, van Genuchten and Vogel2006), Lin (Reference Lin2010) and Fan (Reference Fan2015). There is a definite overlap between the CZ as conceived and the pedosphere realm, but the CZ is much more. The CZ is the entire surface of Earth and it extends upward including the biomass on the surface and downward through the saturated and unsaturated portions of the pedosphere. But because of the possibility of erosion on the Earth's surface, paleosols are likely only a portion of the former CZ, i.e., a truncated part of the record.

THE PALEO CRITICAL ZONE CONCEPT (PCZ)

CZ is the thin skin of Earth upon which life thrives. The modern CZ is where the transfer of mass and energy takes place (Fig. 2). Internally, gas and heat exchange activate hydrological processes, increase biological productivity and generates pedogenic processes. Microbes are expected to be present everywhere (Akob and Küsel, Reference Akob and Küsel2011). Externally, large-scale geological processes, local surficial processes and anthropogenic input are causes that turn the crank and drive the weathering machine (Brantley et al., Reference Brantley, Goldhaver and Ragnarsdottir2007). The integrative studies of the CZ as laid out in the National Resource Council Report (2001) made a strong case for applying the concept developed on modern Earth to geological time scales. The idea was to identify ancient (now termed PCZ) or deep time records that have been separated from the Earth's surface (Fig. 3). They are an untapped resource of paleoenvironmental information from time slices at key times in the four-billion-year history of CZ processes. They include environmental variations caused by major volcanic episodes, meteorite impacts and other extreme events. This archive of CZ history likely records a far richer range of states of the landscape and environment than we can observe directly in the tiny slice of time we occupy today living in the modern Earth’s CZ.

Figure 2. Mass and energy flux for the CZ is a dynamic interval with mass and energy fluxes driven by solar energy. CZ is a unifying concept that accommodates a variety of near surface processes, feedbacks, linkages and most importantly is a physical record of them.

Figure 3. Schematic diagram depicting the elements of the CZ, a near surface environment that extends from the top of the vegetation canopy to the base of weathering. When buried CZs become PCZs but are usually truncated with the bedrock rarely preserved. In stacked PCZs the base is composed of sediment.

Figure 4 illustrates what a complete PCZ textural record might look like and the geological factors, such as sedimentation rate or tectonism that would determine the potential for preservation. A high sedimentation rate, stable or subsiding surfaces lead to the thickest PCZs. Uplift, erosion and low sedimentation produces thin or no records. The position of the water table, vadose zone and phreatic zone are indicated. A complete idealized PCZ when forming would contain a basal layer of (1) dry unweathered bedrock, overlain by what would have been (2) wet unweathered bedrock, and in turn overlain with (3) fractured bedrock. Perhaps a more realistic depiction based on what we know of the natural environment might show a more complicated CZ architecture that has deep penetrating fractures generated by tectonic deformation (Molnar et al., Reference Molnar, Anderson and Anderson2007). The physical nature of the base of the CZ will vary with the geological context. The lithosphere will vary from bedrock to sedimentary deposits. Stacked PCZs will by their nature be sediment (Fig. 3) and vary in the time for their formation. Overlying the (3) the wet fractured bedrock is (4) a regolith mix of sediment and suspended bedrock clasts. Near the top (5) is irregularly layered sediment (clay, silt, sand and clasts) and (6) organic-rich sediment (humus) at the top in humid environments and mineral formation in arid environments.

Figure 4. Factors that affect its development and preservation potential are listed together with a diagram of a complete PCZ from vegetation surface (top) to unweathered bedrock (base).

Only few studies have been conducted on “PCZs”, as such, however there have been many studies over the last decades on “buried soils” or “buried paleosols”, e.g., although many have a narrow research scope such as of tracking climate change (Alexandrovskiy et al., Reference Alexandrovskiy, Glasko, Krenke and Chichagova2004; Zech, Reference Zech2006) or developing a new dating technique (Balco and Rovey, Reference Balco and Rovey2008). Lukens et al. (Reference Lukens, Lehmann, Peppe, Fox, Driese and McNulty2017) studies an Early Miocene record successfully using the PCZ approach to reconstruct the flora and fauna. Nordt et al. (Reference Nordt, Hallmark, Driese, Dworkin and Atchley2012) applied the CZ concept to an early PCZ and Nordt and Driese (Reference Nordt and Driese2013) to a Cretaceous alluvial record. Both of these studies were termed deep-time Critical Zones (DTCZ), which is defined in the 2001 NRC Report as pre-Quaternary (<2.6 Ma). But, to date there have been few Quaternary-age PCZ studies.

THE QUATERNARY PERIOD

The Quaternary Period is divided into two epochs, the Pleistocene beginning at 2.588 Ma and ending ~ 12.7 ka and followed by Holocene that officially would merge with the Common Era (C.E.). We have entered the Anthropocene in which human activity is the dominant influence on climate perhaps arguably beginning as early as 8,000 years ago (Ruddiman, Reference Ruddiman2005), The industrial revolution accelerated the rise of CO2 in the atmosphere triggering major warming changes to Earth (Ruddiman, Reference Ruddiman2005; Cronin, Reference Cronin2010; Zalasiewicz et al., Reference Zalasiewicz, Williams, Haywood and Ellis2011).

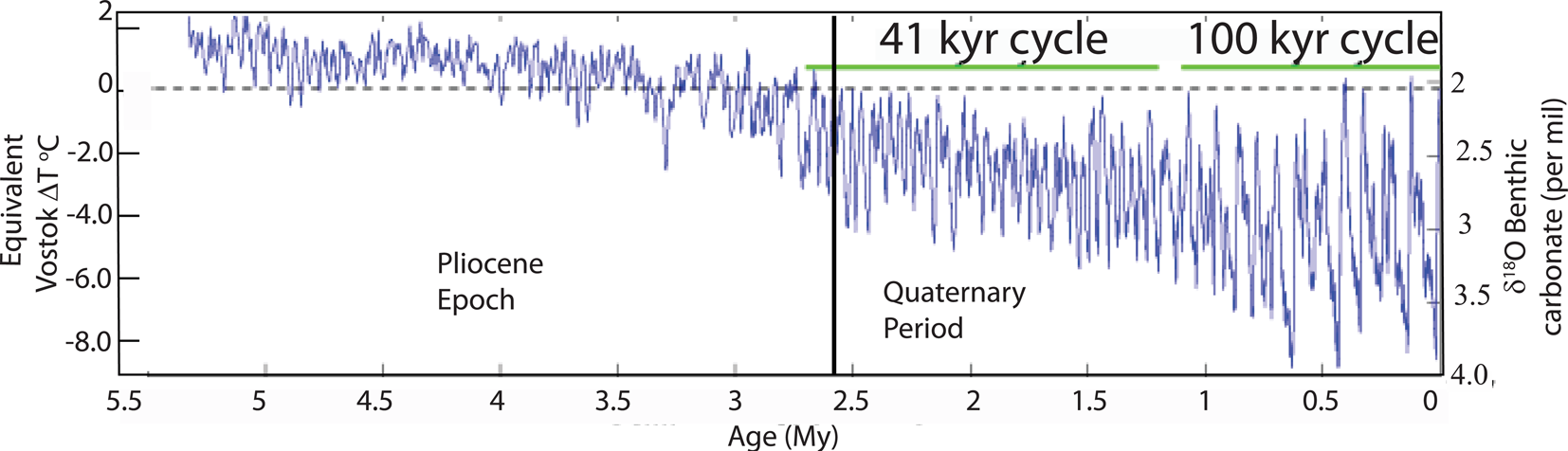

The Quaternary Period is typically thought of as the “Ice Age”, a time driven by Milankovitch cycles characterized by growth and melting of glaciers at high elevations and high latitude (Fig. 5). The 41,000 year cycles dominated the first ~1.5 Ma and 100,000 cycles the latter portion (Lisiecki and Raymo, Reference Lisiecki and Raymo2005). Sea level fluctuations up to 120 m tracked the growth and then decay of continental ice sheets and land bridges between land masses that opened and closed (Imbrie and Imbrie, Reference Imbrie and Imbrie1986; Denton et al., Reference Denton, Anderson, Toggweiler, Edwards, Schaefer and Putnam2010). Mid to lower latitude areas were also affected by Milankovitch-driven climate cycles causing a shift in global temperatures (cooler) and changes to atmospheric circulation that affected the spatial and temporal distribution of rainfall (Ruddiman, Reference Ruddiman2000; Kieniewicz and Smith, Reference Kieniewicz and Smith2009; Cronin, Reference Cronin2010). Major environmental changes occurred in vegetation and fauna (Lowe and Walker, Reference Lowe and Walker2015). There was a major extinction of large mammals, such as mammoths and mastodons, sloths and saber tooth cats during the late Quaternary (Stuart, Reference Stuart1991; Barnosky et al., Reference Barnosky, Koch, Feranec, Wing and Shabel2004).

Figure 5. Milankovitch-driven climate is present across 5.5 million years of climate change as shown by changes in δ18O‰ in carbonate benthic forams. From Global Warming Art Project:Wikipedia Commons.

The early Quaternary Period was a time when the rate of evolution and the rate of speciation increased (Vrba et al., Reference Vrba, Denton, Partridge and Burckle1996; Barnosky, Reference Barnosky2005; NRC, 2010). As this acceleration of change in hominins occurred climate variability (magnitude and frequency) increased (Fig. 5). The association between climate variability and human evolution is not necessarily a cause and effect connection, but the coincidence has been noted by several researchers e.g. (Potts, Reference Potts1996; DeMenocal, Reference DeMenocal2011; Shultz and Maslin, Reference Shultz and Maslin2013)

PCZ RECORDS OF HOMININS: CASE STUDIES

Case Study 1: Homo habilis (1.84 Ma), East Africa

Hominin evolution began in Africa and was well advanced by the beginning of the Quaternary Period (2.588 Ma; NRC, 2010). Most of the hominin archaeological sites are in the East African Rift System where extensional tectonics regularly produces accommodation space, localized high sedimentation and volcanic outpouring of datable lavas, pyroclastics and ash beds. Preservation potential is high in the rift. Rift tectonics (uplift and down faulting), changing base level, climate fluctuations and active volcanism produced a continually changing land surface and sedimentation rates. Most of the rest of the hominin record is found in fossil-rich cave deposits in South Africa (Kullmer, Reference Kullmer2015). Oddly, the oldest hominin fossil ~7.2 million years old was found in neither the rift valley or in the caves, but rather in the intracratonic basin of Lake Chad (Brunet et al., Reference Brunet, Guy and Pilbean2002). During the Late Pliocene, hominins evolved into two distinct lines, the Australopithecines who went extinct at ~ 1.0 Ma (Grine, Reference Grine and Grine1988; Wood and Richmond, Reference Wood and Richmond2000) and the hominins who thrived and culminated in Homo sapiens, the only species now left on Earth. Unfortunately, there is a dearth of hominin remains in Africa for study. However, the East African Rift System is comprised of copious rift basins that are infilled with huge thicknesses of sediment (Frostick, Reference Frostick and Selley1997; Gawthorpe and Leeder, Reference Gawthorpe and Leeder2000) and thus the region has great potential for future discovery of fossils and PCZ records.

FLK Zinj Site, Olduvai Gorge

The study of human origins grabbed the world's attention with the discovery of Zinjanthropus in 1959 in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania by Louis and Mary Leakey (Leakey, Reference Leakey1959). Although the fossil (OH5) was later reclassified as Paranthropus boisei, the name “Zinj” has stuck and the FLK Zinj archaeological site is now a World Heritage locality visited by hundreds of thousands of tourists annually. The site is an excellent model of a high yielding PCZ and serves as an example of what valuable information on hominin habitats and behavior can be gleaned from the sedimentary record (Magill et al., Reference Magill, Ashley, Domínguez-Rodrigo and Freeman2016).

The site has two excavations (FLK Zinj and FLK NN) conducted by the Leakeys in the early 1960s (Leakey, Reference Leakey1971). Figure 6A depicts a paleoenvironmental reconstruction of a woodland covering a low topographic mound and a spring and wetland complex 200 m to the north. The Zinj fracture system, a north-south normal fault cuts directly through the wetland, but passes just to the west of woodland. The Zinj Fault can be traced southward for a least a mile (Driese and Ashley, Reference Driese and Ashley2016). The fault has been identified as a groundwater-conveying fracture system in this part of the Olduvai basin. A number of studies give details on this paleo water source and its importance to hominins living there (Ashley et al., Reference Ashley, Barboni, Domínguez-Rodrigo, Bunn, Mabulla, Diez-Martin, Barba and Baquedano2010; Domínguez-Rodrigo et al., Reference Domínguez-Rodrigo, Bunn, Mabulla, Ashley, Diez-Martín, Barboni, Prendergast, Yravedra, Barba, Sanchez, Baquedano and Pickering2010; Arráiz et al., Reference Arráiz, Barboni, Ashley, Mabulla, Baquedano and Domínguez-Rodrigo2017).The sedimentary records, PCZs, the woodland (Fig. 6B) and wetland (Fig. 6C) are immediately overlain by an airfall tuff (Tuff IC), thus they are correlated and equivalent in age. Single crystal 40Ar/39Ar dating yielded and age of 1.84 Ma for the tuff (Deino, Reference Deino2012).

Figure 6. An example of a PCZ in Africa dated at 1.84 Ma. (A) Artists rendition of the paleoenvironment of hominins shows a small woodland and a spring-fed wetland 200 meters apart. (B) PCZ is outcrop of an organic-rich paleosol directly overlain by an airfall tuff (Tuff IC). Soil formed in the woodland and contains copious mammal bone fragments and stone tools. (C) PCZ is outcrop of freshwater carbonate (tufa) mixed with clay that was deposited in the spring-fed wetland located on a lake margin. Modified from Ashley et al. (Reference Ashley, De Wet, Karis, O'reilly and Baluyot2014).

Figure 6B is a photo of a recent excavation at the FLK Zinj archaeological site that had yielded two hominins, Paranthropus (H5) and Homo habilis (H6) in 1959. The hominin remains were recovered from a buried soil, i.e. an organic-rich paleosol (325 m2 area) along with 2500 stone tools (Leakey, Reference Leakey1971). Thousands (~3500) of vertebrate bones, many cut-marked presumably by hominins were also recovered from this bone bed. Recent biogeochemical studies of the biomarkers including lignin and leaf waxes revealed that the paleosol had formed beneath a woodland (Magill et al., Reference Magill, Ashley, Domínguez-Rodrigo and Freeman2016). Plant biomarkers relate to ecosystem structure including the canopy within the Critical Zone and can distinguish C4 arid-adapted grasses (δ13Cwax values = -20‰) from C3 trees and forbs (δ13Cwax values = -36‰). Figure 6C is a view of an excavation by the Leakeys in FLK NN that shows a 40 cm thick freshwater carbonate (tufa) containing admixed clay that is the same age as the bone bed. Stable isotope data, microfossils and biomarkers indicate diverse plants like sedge and ferns that formed in a freshwater spring-fed wetland (Fig. 6A). These aquatic plants may have served as food sources for hominins.

Piecing together the information from the PCZ, the Zinj archaeological site was a small woodland to which hominins brought animal limbs and carcasses to eat in the safety of the trees. The assumption is that the vertebrates were drawn to the wetland-spring complex for the freshwater and were killed by carnivores and then scavenged or possibly hunted by hominins (Bunn and Kroll, Reference Bunn and Kroll1986; Ashley et al., Reference Ashley, Barboni, Domínguez-Rodrigo, Bunn, Mabulla, Diez-Martin, Barba and Baquedano2010; Domínguez-Rodrigo et al., Reference Domínguez-Rodrigo, Bunn, Mabulla, Ashley, Diez-Martín, Barboni, Prendergast, Yravedra, Barba, Sanchez, Baquedano and Pickering2010). Preliminary research on the taphonomy of the vertebrate remains from the Zinj site suggests that Early Pleistocene Homo was an ambush predator (Bunn and Gurtov, Reference Bunn and Gurtov2014).

Significance of the PCZ approach is that the multifaceted information that is accrued and allows interpretations beyond a simple presence or absence of a type of vegetation (Stinchcomb and Beverly, Reference Stinchcomb and Beverly2019). Paleoanthropologists have been struggling with interpretation of the archaeological sites, as to the hominin behavior involved with respect to food access and foraging. Were hominins hunting or scavenging? The details of the landscape, the presence of water and edible food and whether the canopy was opened or closed provides important information for developing models of sophisticated hominin behavior.

Case 2: Homo sapiens, (10 Ka), The Americas

The chronology and route(s) taken by modern humans that migrated out of Africa and spread throughout the world is a study in progress (Fleagle et al., Reference Fleagle, Shea, Grine, Baden and Leakey2010). DNA studies indicate migrations of small groups began by at least 80 ka and most likely followed coastal routes that ensured freshwater and food (Faure et al., Reference Faure, Walter and Grant2002; Gugliotta, Reference Gugliotta2008). Humans eventually arrived in the Americas by crossing the Bering Land Bridge that connected the Asian continent to the North American continent (Waters, Reference Waters2019). Evidence from nuclear gene markers, mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosomes indicates that all Native Americans came from Asia (Karafet et al., Reference Karafet, Zegura, Hammer and Ubelaker2006; Merriwether, Reference Merriwether and Ubelaker2006).

This land mass, Beringia, was created by the lowering of sea level during the last glacial maximum (LGM at ~25-18 ka; Goebel et al., Reference Goebel, Waters and O'Rourke2008). Glaciers covered the land between 33 ka to ~12 ka. Thus, migration routes, here too, likely followed the coast until an ice-free corridor on land opened up. The coastline and any archaeological records of humans arriving in the new world were unfortunately submerged under accelerated sea level rise that occurred due to massive continental ice loss at the end of the LGM-early Holocene. Sea level has been quasi-stable since ~ 6 ka. Eustatic sea level rise since the industrial revolution (~ CE 1850) is measured in decimeters, and less along much of the Pacific Coast of North America where tectonic uplift causes relative local sea level fall. Although, not abundant, pre-Clovis archaeological sites occur in both North and South America containing records of human bones and their cultural remains. Some notable archeological sites that have documented peopling of the unglaciated land south of the ice sheets to as early as 17.5 ka are Monte Verde, Chile (~18 ka; Dillehay et al., Reference Dillehay, Ocampo, Saavedra, Sawakuchi, Vega, Pino and Collins2015); Cooper's Ferry, Idaho (~16.0 ka; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Madsen, Becerra-Valdiva, Higham, Sisson, Skinner and Stueber2019); Debra L. Friedkin, Texas (15.5 ka; Waters et al., Reference Waters, Keene, Forman, Prewitt, Carlson and Wiederhold2018); and Paisley Caves, Oregon (12.3 ka; Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Jenkins, Gotherstrom, Naveran, Sanchez, Hofreiter and Thomsen2008; Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Davis, Stafford, Campos, H, Jones and Cummings2012).

Studies in the central plains of the US indicate that buried paleosols of Paleoindian-age are found in alpine bogs, alluvial fans, and river valleys (Mandel, Reference Mandel2008). But, many are likely hidden from view deeply buried in river valleys that were infilled during postglacial adjustment of watersheds to change in vegetation, base level and climate (Mandel, Reference Mandel2008; Waters, Reference Waters2019). Others may have been eroded or submerged on the continental shelf. However, many buried archaeological sites have been discovered and studied providing important information on where the first Americans came from, when they arrived and the cultural traditions they brought with them (Meltzer, Reference Meltzer2009; Waters, Reference Waters2019). These deposits have been termed “buried soils” or “buried paleosols” because of physical and chemical evidence of pedogenesis (Birkeland, Reference Birkeland1999; Retallack, Reference Retallack2001). Buried soils display great variability in characteristics and are an important subset of the full spectrum deposits found in PCZs.

Richard Beene Site, Texas, USA

The Richard Beene archaeological site in southwestern, Texas, was chosen as a case study of Homo sapiens records found in buried soils, that has the potential to continue to inform us about the Quaternary period. The site is well exposed, well dated and has been extensively studied (Mandel et al., Reference Mandel, Jacob, Nordt, Thoms and Mandel2007; Thoms and Clabaugh, Reference Thoms and Clabaugh2011; Mandel et al., Reference Mandel, Thoms, Nordt and Jacob2018). The site is an ideal candidate for applying the more inclusive PCZ methodologies. The use of the holistic approach of PCZ analysis provide new insights and hopefully maximize the understanding of the paleoclimate, paleoenvironment and subsistence strategies of early humans in the Americas (Ferraro et al., Reference Ferraro, Hoggarth, Zori, Binetti and Stinchcomb2018).

A field sketch of an outcrop at Richard Been archaeological site of Mandel et al. (Reference Mandel, Thoms, Nordt and Jacob2018) illustrated in Figure 7 shows the interpreted stratigraphy and radiocarbon ages. The 20-m-thick stratigraphic sequence is a spectacular exposure that reveals stacked sedimentary packages of floodplain alluviation alternating with periods of stability and pedogenesis overlying sand and gravel (33,000–20,000 14C yr BP). Records of vertebrates (14,000–11,000 14C yr BP) contained no human bones or cultural remains. However, overlying these layers, twenty stratigraphically distinct archaeological deposits were identified yielding > 80,000 artifacts excavated from areas totaling 730 m2. The archaeology represented Early Archaic (~ 8800 14C yr BP to Late Pre-Columbian (~ 1,200–400 14C yr BP) cultural periods (Fig. 7). Some paleoenvironmental data were collected: (1) the CaO3 (%) that is used as a proxy to track changes in aridity through time; and (2) organic carbon (%). The relative proportion of C3 and C4 plants on landscape, that in turn reflect changes in temperature and moisture, was estimated from soil organic matter using a mass balance equation developed by Nordt et al. (Reference Nordt, Boutton, Jacob and Mandel2002). However, PCZs are time slices that capture much more, such as aspects of the hydrosphere (e.g., precipitation amounts, seasonality records, groundwater discharge zones), atmosphere (pCO2 and pO2), biosphere (organic molecular biomarkers, fossils including hominins), pedosphere (micromorphology and geochemical profiles), and lithosphere (clastic sediments and paleosols). Thus, tracking changes in PCZs through time can provide an integrative history of time humans were walking the landscape. Integrative, holistic records from PCZ inform us more than individual records on their own.

Figure 7. An example of a PCZ in North America dates at 10 ka. Generalized cross-section of the west wall from a quarry excavated into Medina River alluvium (Mandel et al., Reference Mandel, Thoms, Nordt and Jacob2018). Exposure reveals stacked stratigraphic units, paleosols and sites of dated material (designated alphabetically). The radiocarbon ages were determined mainly on wood charcoal.

CRITICAL ZONES IN THE SOLAR SYSTEM

PCZs are the “deep time” archives of Earth's ancient surfaces that were buried, thus completely separated from mass and energy fluxes at the surface. As PCZs stack up they are a valuable record of the variability of CZ through time (Fig. 3). With the advent of the space age and exploration of other bodies of our solar system we will be looking into the unknown for other forms of life, useable sources of water, and valuable minerals. We will need to make observations to interpret and, hopefully, understand the geological processes operating on planet surfaces. Under this scenario, a logical next step is to apply the concept of the CZ and PCZ to the study of planetoidal surfaces within the Solar System, such as Mars, asteroids and comets. Abiotic CZs (proto-CZs), that support organic chemical reactions, may already be recognized on Ceres and comet 67P-Churyumov-Gerasimenko (European Space Agency, 2019). Terrestrial studies of the CZ have generally concentrated on the biological aspects of the concept so studies of proto-CZs on other Solar System bodies require a dramatic shift of emphasis. The exploratory focus will likely be on Mercury, Venus and Mars, the bigger planetoids in the asteroid belt and moons of the gas giants further out from the Sun (Ashley and Delaney, Reference Ashley and Delaney2017). Exploration of Mars over the last decade with rovers and satellites have revealed sedimentary rocks (Grotzinger et al., Reference Grotzinger, Hayes, Lamb, McLennan, Mackwell, Simon-Miller, Harder and Bullock2013). These rocks could have PCZs and with the appropriate technology might be studied in future missions. Not enough is current known about PCZs on Mercury or Venus.

The CZ is a region of mass and energy flux, and is a multidimensional boundary zone(s) between the solid planetoid and its gaseous +/- liquid envelopes, at various locales on the surface (Fig. 8). Earth's CZ's have physical, chemical, biological and three-dimensional morphological aspects that evolve through time. All solid bodies of the Solar System must have proto-CZs though they should vary dramatically reflecting the boundary conditions on the specific planetary body. In particular, the effect of biological components, if any, remains to be assessed. Basic factors that influence the structure and evolution of planetary CZ's are similar to those on Earth (Fig. 2), but terrestrial studies of the CZ have focused on the biological aspects of the concept and are mostly limited to short time scales, in large part because of the turbulent nature of the atmosphere-hydrosphere system and its cascade of processes and effects on the physical and chemical weathering, transport, and deposition of sediment across space and time scales at Earth's surface.

Figure 8. Comparison of CZs on Earth and other bodies in the Solar System. Radiation flux from atmosphere/exosphere fuel reactions in regolith enhanced by fluid and gas fluxes. Proto-CZs (abiotic CZ's) that support organic chemistry have been recognized (cf. Rosetta at comet 67P-Churyumov-Gerasimenko; European Space Agency, 2019).

Mars: A case study of a rocky planet

PCZs as records of early processes on the Martian surface

Mars has been explored since 1976, starting with data from orbiters and followed by Lander Missions that provided troves of high-resolution images as well as geochemical and geophysical data. From that we now know that Mars is geologically complex and may have had a history somewhat similar to Earth. Mars is a single plate planet with no extant plate tectonics. Similarly, the ambiguity about the presence or absence of biological activity contributes to these fundamental differences between Earth and Mars and will influence each planet's CZs differently.

Mass and energy flux processes that are likely prior to the onset of biological activity are: (1) hydrologic cycles; (2) carbon cycles; (3) gas exchange (major and trace); (4) weathering (chemical and physical); (5) erosion and deposition (physical processes); (6) lithification (diagenesis); and (7) soil genesis (pedology) by impact “gardening”, the process by which impacts move material from depth and emplace it on or near to the surface. Gardening is also called “mixing” or “overturn”. In addition, extraterrestrial CZ's include (9) solar and cosmic radiation fluxes, and (10) impact caused resurfacing events that result in punctuated evolutionary histories not typically studied on Earth. Both contemporaneous proto-CZs and PCZs occur. PCZs provide a holistic integration of ancient landscapes including paleo-atmosphere, paleo-hydrosphere and paleo-biosphere (Retallack, Reference Retallack2014; EuropeanSpaceAgency, 2019). Evidence of CZ's can be over-printed, obliterated and even removed by surface processes, so proto-CZs may be poorly preserved or incomplete in the stratigraphic record.

Earth is a ‘habitable zone’ planet, but we here discuss the application of the CZ to other rocky planets and bodies in the Solar System (Morbidelli et al., Reference Morbidelli, Lunine, O'Brien, Raymond and Walsh2012) where the physical evidence is more accessible than the biological evidence. Eight factors are essential for a habitable zone. (1) Water is an essential component of all CZs. The role of H2O phases must be considered in detail because the presence or absence of water influences not only the potential for extant life but also the physical evolution of planetary surfaces. (2) Carbon cycles for other bodies remain poorly understood. Both biogenic and abiogenic carbon cyclicity is fundamental and, indeed, is the ‘Holy Grail’ of biogenic CZ studies. (3) On Earth, interaction with the dense atmosphere, in addition to the hydro/cryosphere, is fundamental to CZ evolution, but atmospheres/exospheres on other bodies have analogous gas exchange processes (Figure 8). (4) Weathering and (5) erosion are the most readily accessible aspects of planetological CZs. Because the effects of these processes are observable from telescopes, satellites, and landers they have received most attention. (6) Lithification is critical to the preservation of the CZ evidence that can be studied either remotely or by detailed sampling. (7) Soil formation processes transform local regolith to the most widespread surface material on Solar System bodies (Vaniman et al., Reference Vaniman, Reedy, Heiken, Olhoeft, Mendel, Heiken and French1991). (8) The absence of unequivocal evidence of extraterrestrial life permits us to neglect biological aspects at present.

Critical zones on Mars

Identification of CZ's on Mars, is already feasible at Gale Crater (Li et al., Reference Li, Li, Ran, Feng and Zuo2015) and using GPR but studies aimed at elucidating the internal structure of a CZ will require coring and sampling at a minimum. Investigating life on Mars requires that we identify and document the environments most conducive to life (CZ's) across the entire planet. The processes and thus the structure of the CZ's likely vary with latitude, longitude and elevation, aspect, bedrock, and energy flux just as they do on Earth.

If Mars was ever habitable (Boston et al., Reference Boston, Ivanov and McKay1992), Martian PCZ's are more likely to reveal the transition from proto-CZ (abiotic) to biotic CZ than on Earth (Fig. 8) where biology dominates and has done since the first evidence of life appeared at ~3–4 Ga. Discussion of potential CZs on Mars in the form of “inverted” CZs (Boston, Reference Boston2015) has begun, but remains to be explored in greater detail. Mars has abundant water (Kargel, Reference Kargel2004). The triple point of water is stable in the relatively shallow subsurface of Mars and may represent the locus of mass and energy fluxes in Martian regolith and soil. The physical, chemical (and biological) consequences of coexisting H2O phases in the near surface will differ across the surface of Mars.

CZs on Mars are the optimum sites for identifying any extant life. PCZs will provide the record of any biological activity during the Noachian and Hesperian Periods from ~4.1 to 3.7 Ga and ~3.7 to 3.0 Ga, respectively.

Atmospheric pressure on Mars ranges from 610Pa in Hellas basin, to 72Pa on Olympus Mons. The triple point of water (611Pa) is easily achieved at depth in many regions of Mars and hence chemical reactions that are catalyzed by liquid water must occur in lowland regions (such as Hellas, Valles Marineris and Vastitus). The almost ubiquitous presence of briny solutions on Mars (Toner et al., Reference Toner, Catling and Light2014) is direct evidence of CZ processes on the planet.

Impact resetting of environments has occurred throughout geological time and provides a stratigraphic constraints on CZ studies. The effect of impacts ranges from microscale ‘gardening’ of the Martian landscape to basin scale erosion that disrupts and evacuates large volumes of crust and spreads debris planet wide. Such large impacts provide the chronometer for proto- and PCZ formation.

CZs are the most important archive of near surface planetary processes where deposition and erosion provide a mobile surface. On balance CZs are steady-state dynamic environments and their 3-D structure evolves (continuously) with time and should be the primary targets of surface exploration. The concept of the CZ, as a record of surficial mass and energy fluxes at surface of rocky bodies can be effectively applied throughout the Solar System.

CONCLUSIONS

The CZ concept provides the framework for studying environments where biology, geology, and chemistry all interact to produce assemblages that provide holistic records of the wide variety of environments found on planet Earth. Over the last two decades scientists have restricted research to mainly chemical and physical weathering processes in the modern CZ. It is now time to take lessons learned from the modern environment and apply to ancient environments using the PCZ Concept. PCZs may also inform our understanding of the modern CZ.

The Quaternary Period is a time of continually changing landscapes, i.e., CZs, forced by astronomical climate cycles. This geologic period is also a time of biological change, of species evolution, extinctions and migrations. The buried sedimentary records are an untapped source of information. Case studies of the archaeological sites of two representative members of genus Homo successfully illustrate the rich records that can be gleamed from PCZs. Finally, as we enter the space age and begin to explore neighboring planets, the CZ concept has great potential as a research tool. Critical Zones, using an expanded definition to include proto-CZs, occur at the surface of all rocky bodies in the Solar System and provide the goal for the search for paleo-biology and life in the future. The holistic aspect of the CZ concept provides more complete targets for missions to explore the near surface of planetoidal bodies such as Mars, asteroids and comets.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The views presented here have evolved over a couple decades in discussions with numerous colleagues. It is difficult to untangle where specific ideas have come from. I appreciate the insights and opinions of Steven Driese, Clayton Magill, Emily Beverly, Gary Stinchcomb, Henry Lin, Kate Freeman, Daniel Deocampo, Jeremy Delaney, Gregory Retallack, Susan Brantley, Lee Nordt, Doris Barboni, Michelle Goman, Andrea Shilling, Tim White, and Monica Norton. I am particularly grateful to Rolf Mandel for his support and assistance with the Richard Beene archaeological record. An earlier version was much improved by the constructive comments of Karl Wegmann, Lewis Owen and an anonymous reviewer.