INTRODUCTION

Evidence of neotectonic activity is scarce in cratonic areas, especially those that were subject to Quaternary glaciations because the glacial deposits typically show abundant non-tectonic disturbances and dislocations that overprint indications of the tectonic and seismic activity during that period (e.g., Murray, Reference Murray and Maltman1994; Maltman et al., Reference Maltman, Hubbard and Hambrey2000).

Evidence of soft-sediment deformation structures (SSDS) interpreted as paleoseismic deformations (seismites) in Lithuania and adjacent areas were recently reported from several sites and were attributed mainly to the post-glacial seismic activity induced by glacioisostatic rebound of the lithosphere (Hasegawa et al., Reference Hasegawa, Basham, Gregersen and Basham1989; Muir-Wood, Reference Muir-Wood2000; Moretti and van Loon, Reference Moretti and van Loon2014; Brandes et al., Reference Brandes, Steffen, Steffen and Wu2015; van Loon et al., Reference van Loon, Pisarska-Jamroży, Nartiss, Krievāns and Soms2015, Reference van Loon, Pisarska-Jamrozy, Nartiss, Krievans and Soms2016; Bitinas et al., Reference Bitinas, Damušytė and Vaikutienė2016; Druzhinina et al., Reference Druzhinina, Bitinas, Molodkov and Kolesnik2017;). The term ‘seismites’ was introduced by Seilacher (Reference Seilacher1969) to document strata that were partially or entirely deformed by earthquake-triggered processes. Seismically induced liquefaction deformations are difficult to identify (van Loon, Reference van Loon2009) and could be mis-interpreted as cryoturbations, glaciotectonic, or water- or sediment-escape structures in the unconsolidated Quaternary soft layers (Bitinas and Lazauskienė, Reference Bitinas and Lazauskienė2011; van Loon, Reference van Loon2014). So far, no evidence of association of the documented paleoseismic deformations (seismites) with the neotectonically active faults and their recent seismic activity has been reported from Lithuania and adjacent areas. The identification of the neotectonic zones, especially those showing seismic activity, is of great practical significance for planning and maintenance of industrial, environmentally sensitive objects, especially nuclear power plants (e.g., Mörner, Reference Mörner2013). In particular, IAEA safety requirements determine the term ‘Capable fault,’ which is defined as being active during the Quaternary period (ASCE, 2000; IAEA, 2010).

In contrast with highly complex glacial deposits, lacustrine sediments infilling extensive paleolacustrine basins with a flat bottom surface of the bottom layer provide a unique possibility to trace neotectonic vertical movements in a more consistent way. Moreover, the lacustrine and glaciolacustrine sediments are especially sensitive to the earthquake tremors and could be documented in outcrops and in shallow seismic profiles (Doughty et al., Reference Doughty, Eyles, Eyles and Boyce2014; Jakobsson et al., Reference Jakobsson, Björck, O'Regan, Flodén, Greenwood, Swärd, Lif, Ampel, Koyi and Skelton2014; Shvarev et al., Reference Shvarev, Nikonov, Rodkin and Poleshchuk2018; Ojala et al., Reference Ojala, Mattila, Hämäläinen and Sutinen2019). These observations sometimes allow assessment of the magnitude of strong earthquakes. For example, the magnitude of the Quaternary seismic tremors was estimated as large as M = 7.0 and higher in Finland (Ojala et al., Reference Ojala, Mattila, Hämäläinen and Sutinen2019). Similar characteristics of Quaternary earthquakes were evaluated in Sweden (Mörner, Reference Mörner1995, Reference Mörner2009; Lund et al., Reference Lund, Roberts and Smith2017). These regions are situated in the northwestern part of the East European craton, like the Lithuanian territory, except with much larger post-glacial rebound magnitudes in the Fennoscandian Shield.

The earliest Quaternary pre-Pleistocene lacustrine sediments, attributed to the Daumantai Formation, were mapped in the well-studied Vilnius area (Satkūnas, Reference Satkūnas1998). The kidney-shaped pseudonodules classified as seismites were documented in the Buivydžiai outcrop located in the proximity of this zone. The seismites are found in the proglacial lacustrine (glaciolacustrine) sediments deposited before the Weichselian glacial maximum.

The aim of this paper is to elucidate the relationship of the seismites of the Buivydžiai site with the adjacent fault and its neotectonic and seismic activity, as a contribution to understanding the significance of neotectonics in the region.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Geological mapping at a scale of 1:50 000 was performed in the vicinities of Vilnius in 1986–1991 (Fig. 1). The area is as large as 2070 km2, and 146 boreholes were drilled through the entire cover of the Quaternary system, which averages 100 m in thickness, reaching up to 250 m in the morainic highlands and paleo-incisions. The Quaternary deposits overlie Neogene, Cretaceous, and Paleozoic bedrock. A large area of lacustrine sediments, 10–20 m thick, occurring on the pre-Quaternary bedrock, was identified in the mapping area. These sediments are attributed to the Daumantai Preglacial Formation (Daumantai Formation) of the pre-Pleistocene division of the Quaternary system (Guobytė and Satkūnas, Reference Guobytė and Satkūnas2011). These are the oldest Quaternary deposits known in the region and accumulated before the oldest pre-Elsterial glaciation (Satkūnas, Reference Satkūnas1998).

Figure 1. Location of the reference outcrops mentioned in the text (D = Daumantai, B = Buivydžiai) and the geological mapping area.

SSDS were documented in the glaciolacustrine sediments cropping out in the Neris valley close to Buivydžiai village. The sediments occur below the late Weichselian MIS2 brown glacial till. The site was analyzed in a background of the tectonic framework unraveled by dense drilling and gravity and magnetic surveys. The magnitude and depth of the hypocenter are suggested by occurrence of the SSDS with respect to the potential seismogenic fault. Recent seismic activity is also discussed in relation to this particular paleoseismic event.

The detailed stratigraphic and lithogenetic interpretation of the Quaternary sediments in all mapping boreholes was based on lithological signatures (grain-size, mineral and geochemical composition) of sediments and paleobotanical evidence (Satkūnas, Reference Satkūnas1998). Stratigraphic identification of the Pliocene sediments and the Daumantai Formation is macroscopically rather complicated due to similarities of the lithological composition (predominantly, sandy lacustrine sediments), however they were subdivided on basis of mineralogical data.

The geological section of the Buivydžiai outcrop was studied in the course of geological mapping, and the SSDS were documented in this outcrop in 2016 (Satkūnas, Reference Satkūnas, Pisarska-Jamroży and Bitinas2018). Importantly, there is no good tectonic-structural control of the studied area. Most of boreholes did not reach the key stratigraphic horizons to enable compilation of detailed structural maps of the pre-Quaternary sediments. However, there are consistent data from gravimetric and magnetometric mapping at the scale of 1:200,000 (Korabliova and Popov, Reference Korabliova and Popov1997). These data, along with deep drilling data, provide some knowledge on the crystalline basement of the study area.

Measurements of the first-level geodetic leveling profiles were carried out along the country-scale line Turmantas-Vilnius (Paršeliūnas et al., Reference Paršeliūnas, Sacher and Ihde2000; Petroškevičius et al., Reference Petroškevičius, Putrimas, Krikštaponis, Būga, Neseckas, Obuchovski, Stepanovienė, Tumelienė, Viskontas and Zigmantienė2005; Anikėnienė, Reference Anikėnienė2008; Zakarevičius et al., Reference Zakarevičius, Šliaupa, Anikėnienė, Dėnas and Šliaupienė2008). These data were analyzed to correlate the recent ground surface motions with the ancient tectonic structures. The profile line is ~150 km long, trending NE-SW in East Lithuania, and crosses the mapping area.

TECTONIC SETTING OF THE AREA

Lithuania is situated in the Baltic sedimentary basin overlying high-grade metamorphic and magmatic rocks of Paleoproterozoic and Mesoproterozoic ages (Motuza, Reference Motuza2005). The thickness of the sedimentary sequence increases from ~0.2 km in the southeast to >2 km in the west. The study area is located in the shallow eastern periphery of the basin, passing in the east to the Mazury-Belarus Arch (also called Anteclise) that separates the Baltic sedimentary basin from the Moscow basin in the east (Stirpeika, Reference Stirpeika1999).

The thickness of the sedimentary cover is only 500–530 m in the study area straddling the boundary between the Baltic basin and the Mazury-Belarus Arch. The Ediacaran and Paleozoic (lower Cambrian, Ordovician, lower Silurian, and middle Devonian) sediments are preserved here. The Paleozoic deposits are covered by lower Cretaceous marine sediments that are dissected in places by deep paleoincisions formed during the Quaternary Period. Some isolated patches of the continental deposits of upper Neogene age are mapped locally.

The eastern periphery of the Baltic basin is less affected by tectonics compared to west Lithuania, where a dense network of faults (mainly middle Paleozoic in age) was documented by extensive drilling and seismic survey related to oil exploration (Šliaupa et al., Reference Šliaupa, Poprawa and Jacyna2000; Šliaupa, Reference Šliaupa2002a). Only two faults that have been proved by drilling are located 40–50 km to the west of the study area (i.e., the Birštonas and Strėva faults, described in unpublished geological mapping reports). The amplitude of those faults reaches ~80 m, both faults are likely of Mesozoic age. So far, no other faults have been proved in the study area by drilling.

There are a number of faults suspected in the sedimentary cover; however, they were not proved by any targeted dense drilling or seismic profiling. A large-scale W-E trending Vilkaviškis-Birštonas-Vilnius fault was suggested close to Vilnius to the south and crosses the whole territory of Lithuania, although drilling data are still too scarce to certify the presence of this fault.

Seismicity of the region

The Baltic sedimentary basin is located in the East European Craton, which shows very little recent seismic activity. For many years, it had been considered as an aseismic region of Earth's crust formed during the Paleoproterozoic time. This perception was changed when extensive studies of historical reports were initiated in the Baltic and Belarus regions in relation to re-assessment of the seismic hazard of the Ignalina nuclear power plant located in northeast Lithuania (Avotinia et al., Reference Avotinia, Boborikin, Yemelianov and Sildvee1988; Boborikin et al., Reference Boborikin, Avotinia, Yemelianov, Sildvee and Suveizdis1993; Aizberg et al., Reference Aizberg, Garetsky, Aronov, Karabanov and Safronov1999; Šliaupa et al., Reference Šliaupa, Kačianauskas, Markauskas, Dundulis and Ušpuras2006; Dundulis et al., Reference Dundulis, Kačianauskas, Markauskas, Stupak, Stupak and Šliaupa2017). More than 40 historical seismic events were reported in the Baltic region (Fig. 2). Information was collected from newspapers, historical annals, etc. No specific geological (e.g., soft-sediment deformation) structures were analyzed until recently, the results of which are discussed below.

Figure 2. Documented historical (since year 1328) earthquakes (black points) plotted against the fault (bold lines) network (modified after Pačėsa and Šliaupa, Reference Pačėsa and Šliaupa2011). Recent earthquakes Daugavpils (Da), Bystritsa (By), Gudogai (Gd), and Smalininkai mentioned in the text are indexed. Light gray stars indicate locations of documented seismites in lacustrine (Ry = Ryadno, Ta = Tauragė, B = Buivydžiai, Ra = Rakuti, Va = Valmiera) and alluvial (Sl = Slinkis) sediments (after Bitinas and Lazauskienė, Reference Bitinas and Lazauskienė2011; van Loon et al., Reference van Loon, Pisarska-Jamroży, Nartiss, Krievāns and Soms2015; Druzhinina et al., Reference Druzhinina, Bitinas, Molodkov and Kolesnik2017; Satkūnas, Reference Satkūnas, Pisarska-Jamroży and Bitinas2018; Pisarska-Jamroży et al., Reference Pisarska-Jamroży, Belzyt, Bitinas, Jusienė and Woronko2019); dark gray stars show Middle Ordovician suspected seismites (Os = Osmussaare, Pa = Pakre) (after Suuroja et al., Reference Suuroja, Kirsimae, Ainsaar, Kohv, Mahane, Suuroja, Koeberl and Martinez-Ruiz2003; Nestor et al., Reference Nestor, Soesoo, Linna, Hints and Nõlvak2007).

The most complete seismic catalogue of the Baltic and partially the Belarus area was compiled by Pačėsa and Šliaupa (Reference Pačėsa and Šliaupa2011), containing information on 78 seismic events. It is notable that several earthquakes were reported at the end of 1908, which closely followed the strong Messina (Italy) earthquake of December 28, 1907, which may have induced seismic activity in the Baltic region.

Since then, no earthquake has been registered in Lithuanian territory, though numerous events were reported from neighboring countries close to the Lithuanian border. The oldest trusted earthquake (M = 4.0) was described in 1375 in southernmost Latvia, close to the northern border of Lithuania. The strongest historical earthquake documented since that event reached magnitude M = 4.5. For decades, this was considered as the maximum possible earthquake magnitude in the Baltic region. The most common depth of the epicenters was calculated to be ~5–10 km. The strongest seismic events were generated at greater depths of 12–20 km (Pačėsa and Šliaupa, Reference Pačėsa and Šliaupa2011).

Only two moderate earthquakes have been registered instrumentally in the Baltic region. One of the strongest instrumentally recorded earthquakes took place on Osmussaare Island (Estonia) in 1976 (magnitude M = 4.75). It should be noted that earthquakes as old as the Middle Ordovician have occurred in this area. Suuroja et al. (Reference Suuroja, Kirsimae, Ainsaar, Kohv, Mahane, Suuroja, Koeberl and Martinez-Ruiz2003) recognized evidence of paleoseismic events on Osumussaare Island in the western Gulf of Finland, Estonia, where they described strongly deformed Kunda Stage limestones of Middle Ordovician age (ca. 475 Ma old) in the outcrops. Similar signatures of paleoseismic activity also have been reported to the east in the Pakri Peninsula (NW Estonia) in the kerogen-rich Kunda Stage (Middle Ordovician) limestones (Nestor et al., Reference Nestor, Soesoo, Linna, Hints and Nõlvak2007). Alternatively, these features can be related to one of the impact craters that occur in the area of the present Gulf of Finland and north Estonia. However, there is no proven tectonic control of those events. These structures are well exposed in the Baltic Klint, but drilling and geophysical information is lacking in this area.

The most recent and strongest known earthquake was recorded in the west Kaliningrad District (Russia) on September 29, 2004. The magnitude was assessed as strong as M = 5.3 (Gregersen et al., Reference Gregersen, Wiejacz, Debski, Domanski, Assinovskaya, Gutterch and Mantiniemi2007) and set the new upper limit of possible earthquakes in the Baltic region. The main shock was preceded and followed by two smaller seismic events. The earthquakes caused moderate infrastructure damage in the Kaliningrad District and lesser damage in north Poland and west Lithuania; it was felt as far away as ~800 km. The hypocenter depth was calculated at 16–20 km. Solution of the focal mechanism suggests that the W-S striking large-scale Sambian fault, which is ~300 km long, was shifted by NNE-SSW horizontal tectonic forces (Alpine far-field tectonic effect). The focal mechanism solution is in good agreement with the break-out measurements in hydrocarbon exploration wells in the southern Baltic Sea.

The Bystritsa earthquake (magnitude M = 3.8–4.0, registered December 29, 1908) is of particular interest because it was located only 12 km from the Buivydžiai site, which suggests the same tectonic control of both seismic events. So far, no tectonic structure has been identified to account for this recurrent seismic activity in the Baltic region.

The most active seismic source in the Baltic region is confined to the most tectonically fragmented Saldus-Liepaja fault-ridge, striking W-E across Latvian territory (Fig. 2). It is the largest tectonic zone recognized in the Baltic sedimentary basin. The vertical amplitude exceeds 600 m in some places (Brangulis and Kanevs, Reference Brangulis and Kanevs2002). The main phase of the fault formation (including the Saldus-Liepaja ridge) occurred in the Baltic sedimentary basin during the latest Silurian–earliest Devonian and is attributed to the collision of the Baltica continent to the Laurentia continent, which significantly increased horizontal stress field in the orogenic foreland area (Šliaupa et al., Reference Šliaupa, Poprawa and Jacyna2000, Reference Šliaupa, Satkūnas, Motuza and Šliaupienė2017; Šliaupa, Reference Šliaupa2002a; Šliaupa and Hoth, Reference Šliaupa, Hoth, Harf, Björk and Hoth2011).

Some seismites have been reported from outcrops of the Late Glacial and Holocene sands and silts in Lithuania and adjacent countries (Fig. 2). Diapir-like, liquefaction-induced structures were reported from the Ryadno Holocene fluvial sediments in the highest alluvial terrace of the Šešupė River in the northern Kaliningrad District (Russia) close to the Lithuanian border. These structures have been interpreted to be seismic in origin (Druzhinina et al., Reference Druzhinina, Bitinas, Molodkov and Kolesnik2017). It is notable that similar pseudonodular structures were reported in Holocene sediments in the Tauragė area, close to the Ryadno site (Bitinas and Lazauskienė, Reference Bitinas and Lazauskienė2011). The signatures of those structures resemble those induced by seismic tremors, with sandy layer fragments ‘sinking’ into the underlying muddy sediments. The Slinkis seismites are of particular interest because they are documented in glaciofluvial sediments dated ~22 kyr (Pisarska-Jamroży et al., Reference Pisarska-Jamroży, Belzyt, Bitinas, Jusienė and Woronko2019), which is close to the age of the Buivydžiai seismites.

The Daumantai Formation

Daumantai Formation deposits are widely distributed in east Lithuania (Fig. 3), where they overlie pre-Quaternary deposits. The Daumantai sediments are absent on the paleouplifts and in paleoincisions of the pre-Quaternary surface, which was formed by glacial and glaciofluvial erosion during the Elsterian, Saalian, and Weichselian glaciations. The Daumantai sediments were assigned to the lowermost Quaternary based on palynological and lithological studies (Satkūnas, Reference Satkūnas1998). In addition, magnetic susceptibility, correlated with TOC, Fe, and Ti data, was applied for a detailed subdivision of the Daumantai Formation (Baltrūnas et al., Reference Baltrūnas, Zinkutė, Šeirienė, Katinas, Karmaza, Kisielienė, Taraškevičius and Lagunavičienė2013). Paleomagnetic polarity data show that the lowermost part of the Daumantai Formation should be attributed to the Matuyama Chron, while most of the Daumantai section was deposited during the Brunhes Chron (Baltrūnas et al., Reference Baltrūnas, Zinkutė, Šeirienė, Katinas, Karmaza, Kisielienė, Taraškevičius and Lagunavičienė2013; Bitinas et al., Reference Bitinas, Katinas, Gibbard, Saarmann, Damušytė, Rudnickaitė, Baltrūnas and Satkūnas2015), the boundary of which is dated 777.6 kyr (Hyodo and Kitaba, Reference Hyodo and Kitaba2015).

Figure 3. Location of the mapping boreholes in the study area: 1 = boreholes in which Daumantai Formation sediments are absent due to glacial erosion (borehole number indicated); 2 = boreholes that penetrated the Daumantai Formation (borehole number, altitudes of top/bottom a.m.s.l.); 3 = geological cross-section line (see Fig. 4); 4 = suggested Buivydžiai tectonic zone; 5 = location of the Buivydžiai outcrop (coordinates of the outcrop are 54°51′57″N, 25°44′37″E); 6 = area of present distribution of the Daumantai Formation lacustrine sediments.

The stratotype for the Daumantai Formation was described in the 25 m high outcrop in the Šventoji River valley close to Daumantai (Kondratienė et al., Reference Kondratienė, Sinkunas, Gaigalas, Satkunas and Kondratienė1993) (Figs. 1, 5), where these sediments overly the Anykščiai Formation (upper Pliocene). The boundary between the Quaternary (Daumantai Formation) and the Neogene (Anykščiai Formation) was established using pollen and lithological criteria. Sands, attributed to the Anykščiai Formation, are characterized by minerals of the ‘Neogene continental’ association, which is represented by stabile minerals, such as quartz (up to 95%), zircon (up to 3.4%), staurolite (up to 6.7%), and ferric oxides and hydroxides (up to 9.6%). The Anykščiai Formation sand is characterized by minimum content of the unstable minerals as pyroxene, garnet, epidote, and hornblende (Juozapavičius, Reference Juozapavičius and Narbutas1976). In the Daumantai Formation sands, the magnetite-garnet-amphibole association is characteristic, which is similar to glacial Pleistocene sediments containing the amphibole-garnet-magnetite heavy minerals association.

The Daumantai sediments have been documented over an area of 2070 km2 (Fig. 3), where these deposits were cored in 59 boreholes. The Daumantai Formation rests on the surface of pre-Quaternary rocks of Paleozoic and Mesozoic ages and overlies upper Pliocene (Neogene) sandy deposits that are <10 m thick. The thickness of the Daumantai Formation deposits varies between 2.4 m and 21.5 m, averaging 9.0 m. The Daumantai Formation is represented by fine-grained sand, sandy silt, with interlayers of silt and less common clay (Fig. 4, 5). Organic matter and terrestrial plant fragments are abundant in Daumantai deposits. In most boreholes, the Daumantai deposits show an increasing content of clay and silt fractions in the upper part of the formation. This may have resulted from deepening of the lake basin during Daumantai deposition (Satkūnas, Reference Satkūnas1998).

Figure 4. Cross-section of the Quaternary succession and underlying substrate rocks across the Buivydžiai outcrop (see Fig. 3 for location of the cross-section). Stratigraphy: S2 = Upper Silurian; D2-Middle Devonian; Quaternary formations: Dm = Daumantai Formation; Dz = Dzūkija Formation; Dn = Dainava Formation; Zm = Žemaitija Formation; Md = Medininkai Formation; Nm = Nemunas Formation. For the stratigraphic subdivision of the Quaternary deposits of Lithuania see Guobytė and Satkūnas (Reference Guobytė and Satkūnas2011). Lithology: 1 = till, 2 = silt and clay, 3 = sand, 4 = gravel; other symbols: 5 = mapping borehole, 6 = location of seismites, 7 = the Buivydžiai fault.

Figure 5. Daumantai Formation sand exposed in the stratotype Daumantai outcrop (25 m high), 75 km north of the Buivydžiai site. The Daumantai Formation overlies the Anykščiai Formation (undulating contact) and is overlain by late Weichselian till (courtesy of V. Mikulėnas).

RESULTS

Late Pleistocene seismites of the Buivydžiai outcrop

Pseudonodular structures were recorded in the glaciolacustrine sediments in the Buivydžiai outcrop, 30 km north-east of Vilnius (Fig. 6). The exposure is located in the valley of the Neris River and is 32 m high. This outcrop is best known due to cropping out of the disputed middle Saalian interglacial (so called Snaigupėlė Formation) organic-rich sediments in the lower part of the section (Fig. 6), which have been studied by various researchers (e.g., Kondratienė and Vichnevskaya, Reference Kondratienė and Vichnevskaya1974; Šeirienė et al., Reference Šeirienė, Šinkūnas, Stančikaitė, Kisielienė and Gedminienė2019).

Figure 6. Geological section of the Buivydžiai outcrop. Legend: 1 = till, 2 = clay, 3 = silt, 4 = sandy silt, 5 = sandy silt with SSDS, 6 = sand, 7 = gravel, 8 = cross-stratified sand (dip-azimuth mainly ~260°). Stratigraphy: IV = Holocene (Neris River alluvial sediments), gr = Grūda Formation, nm = Nemunas Formation, mr = Merkinė Formation, md = Medininkai Formation, s = Snaigupėlė Formation. Genesis of sediments: a = alluvial, lm = limnic, lg = glaciolacustrine, g = glacial. Seismites occur at 4.2 m depth.

The SSDS were identified in the glaciolacustrine (proglacial lake) sandy silt (Figs. 6, 7) of predominant grain-size 0.05–0.005 mm, composing 55–60% of the sediment, 4.2 m below the late Weichselian MIS 2 (Nemunas 3) brown glacial till (Fig. 6). The proglacial lake sandy–silty sediments are underlain by massive clay. Lacustrine sediments accumulated in front of the advancing late Weichselian ice sheet (Nemunas 3) just prior to MIS 2, and are attributed to a time span of 25–24 kyr BP (Fig. 8). The soft, fine-grained sediments should have been sensitive to any kind of mechanical instability and liquefaction.

Figure 7. (color online) (A) Seismites in glaciolacustrine sediments documented in the Buivydžiai outcrop (photo by V. Mikulėnas). The kidney-shaped pseudonodule chain (K1–K4) is shown. The bottom contact of most of the nodules is marked by a thin, muddy coating. Nodules are composed of fine-grained sand hosted by fine-grained silty sand. Few undulating blackish thin surfaces (BS) mark slightly deformed short breaks in sedimentation; (B) photo with perpendicular cuttings into the outcrop in order to revealto illustrate size of the sandy lenses; (C) enlarged view of one of the seismitic lenses.

Figure 8. Climatostratigraphic events of the late Pleistocene along the line C–P from the central region of glaciation in Sweden to the line of the Last Glacial Maximum (vicinity of Vilnius) (Satkūnas et al., Reference Satkūnas, Grigienė, Jusienė, Damušytė and Mažeika2009). The star indicates supposed time and location of the Buivydžiai earthquake.

The kidney-shaped pseudonodules, composed of fine-grained sand, are mainly 10–14 cm long, 3–4 cm thick, and 5–15 cm wide (in plan view) lenses that ‘float’ in the sandy silt sediments (Fig. 7A–C). The lower contact of nodules commonly is marked by a thin, dark coating that could be interpreted as a remnant of the erosional surface, which implies a new depositional cycle starting with sandy deposition after a short break in sedimentation. Rarely, smaller sand lenses (~1.5 cm long) with convex lower and planar upper surfaces, resembling pillow-beds, occur between the kidney-shaped lenses. The grain size compositions of the disrupted layer of very fine-grained sand and the underlaying sandy silt are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Grain size composition (mm) of sandy silt (int. 3.6–6.8 m) and sand of the Buivydžiai outcrop (int. 6.8–7.4 m) (see Fig. 5 for outcrop geological section).

The fine-grained composition is most typical for SSDS induced by sediment liquefaction (Üner, Reference Üner2014; Paudel, Reference Paudel2015; Velázquez-Bucio and Garduño-Monroy, Reference Velázquez-Bucio and Garduño-Monroy2018). Pseudonodules form when the overlying sand layer is detached and sinks to form isolated kidney-shaped bodies encased in the underlying sediment (i.e., it is a gravity-driven mechanism). Several processes, both seismic and non-seismic, can trigger formation of these types of pseudonodules (e.g., rapid deposition, gravity-induced mass movements, lake storm waves) (Tokimatsu and Yoshimi, Reference Tokimatsu and Yoshimi1983; Moretti and van Loon, Reference Moretti and van Loon2014). This kind of pseudonodule is formed by mobilization of unconsolidated, overpressured sediments facilitated by expulsion of pore water (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Moretti and Alfaro2011). Introduction of material from the surface towards the base increases the pore pressure and gives way to the injection of material from the base towards the top. According to Owen et al. (Reference Owen, Moretti and Alfaro2011), the movement of these sediments is driven by gravitational processes, even if they are not directly connected to the surface, and their mobility is similar to surficial processes.

Several blackish erosional surfaces are present, marking short breaks in sedimentation that indicate a shallow sedimentation environment (Fig. 7). It is notable that those surfaces are slightly undulating, suggesting mechanical deformation by escaping fluidized sandy silt from below (Fig. 9). It is notable that the lower contact of the nodules of the disrupted sand layer is also marked by blackish coating, suggesting deposition of the sand on the erosional surface (Fig. 7).

Figure 9. Formation model of seismic structures of the Buivydžiai outcrop. (A) Section of the glaciolacustrine sediments accumulating in the basin prior late Weichselian glacial advance; (B) formation of seismic kidney-shaped sand pseudonodules separated (protruded) by cones of sandy silt. 1 = silt, 2 = sand, 3 = liquefied sandy silt, 4 = cones of sandy silt.

Most of the ball and pillow structures neither are laterally equivalent nor grade into sand lenses and have no vertical repetition, which can be inferred to be a result of seismic triggering. Seismic events can be recorded in sedimentary successions as seismites—layers characterized by earthquake-induced soft-sediment deformation structures, including convolutions, dish and pillars, flame structures, and sand volcanoes. Seismites are formed by liquefaction of unconsolidated sediments triggered by strong earthquakes (Seilacher, Reference Seilacher1969; Lowe, Reference Lowe1975; Van Loon, Reference van Loon2014; Nirei et al, Reference Nirei, Takayuki, Marker, Satkūnas, Kazaoka and Furuno2015, Reference Nirei, Kazaoka, Uzawa, Hiyama, Satkūnas and Mitamura2016).

Indications of fault tectonics

Based on drilling data, the top surface of the Daumantai Formation occurs at nearly the same level about +67 m a.m.s.l. in the southern part of the study area, while it is mapped at a higher level (+75 m a.m.s.l.) in the northern part of the study area (Fig. 3). The altitude difference is ~5–8 m and suggests presence of an active linear zone, oriented NW-SE, with a relatively uplifted northern flank. It cannot be considered as an erosional feature because the formation overlies the Neogene peneplain, which does not have any distinct relief irregularities. It also implies that this linear zone was neotectonically active, causing vertical displacement of the Daumantai Formation. Furthermore, the western continuation of the Buivydžiai zone is represented by vergence of several faults. They are marked by the local isolated remnant patch of the Daumantai sediments elongated NW-SE, which can be interpreted as the down-thrusted fault microblock (Fig. 3).

Recent studies revealed the significant role of the crystalline basement tectonic grain on the tectonic evolution of the sedimentary cover and neotectonic activity, including recent vertical movements (Šliaupa et al., Reference Šliaupa, Satkūnas, Motuza and Šliaupienė2017). Most of the study territory is situated in the western part of the Belarus-Podlasie Granulite Belt of Paleoproterozoic age (Motuza, Reference Motuza2005; Motuza et al., Reference Motuza, Motuza, Salnikova and Kotov2008). It is represented by mafic and migmatitic granulites that are mirrored by the lenticular pattern of the gravity and especially magnetic field anomalies (Fig. 10). Anomalies trend NE-SW and point to the thin-skinned internal structure of the basement.

Figure 10. Magnetic field map (*10,000 nT). ByE = Bystritsa earthquake (December 29, 1908; M = 3.5–4.0; depth 9 km), GuE = Gudogai earthquake (December 28, 1908; M = 4.5; depth uncertain) and B = Buivydžiai outcrop locations are indicated.

The Buivydžiai fault is discernible in the gravity and magnetic field maps by the left-lateral shift (in plan view) of the lenticular anomalies (Fig. 10). The Bystritsa earthquake is confined to the NW-SE striking sharp gradient zone between the local magnetic high and background magnetic low. Some distinct W-E trending shear zones also are suggested by a magnetic low just south of Vilnius. It is confined to the above-mentioned suspected Birštonas-Vilnius fault in the sedimentary cover. The Gudogai earthquake was recorded December 28, 1908, just one day before the Bystritsa earthquake. It was a stronger (M = 4.5) event compared to the Bystritsa earthquake (Pačėsa and Šliaupa, Reference Pačėsa and Šliaupa2011); both earthquakes can be reasonably classified as a main shock and an aftershock. The Vilnius fault is marked by the southern limit of the distribution of the Daumantai lacustrine sediments elongated to the west (25 km long and 15 km wide) (Fig. 3).

Neotectonic activity of the Buivydžiai zone is also evident in the lithological pattern in the Quaternary succession. Boreholes drilled to the north of the zone are characterized by a distinct predominance of sandy sediments in the Quaternary section, while till is the dominant lithology to the south (Fig. 4). Obviously, the Buivydžiai fault exerted significant influence on the sedimentation processes during Quaternary glacial deposition. Furthermore, some effect on the surface processes can be considered. The Buivydžiai fault controls the NW-SE stretch of the Neris valley. There are no discernable traces of fault activity in the relief farther to the north-west. Due to the marginal position of the Buivydžiai site, no remanent glacioisostatic rebound movements are active in the area anymore, and recent Bystritsa and Gudogai earthquakes should have been tectonic in nature.

Recent tectonic movements

There are no unambiguous indications of the Buivydžiai fault in the pre-Quaternary sedimentary cover because most of the mapping boreholes did not reach any reference stratigraphic boundary to compile a detailed structural map. However, depth variations of the Middle Devonian deposits (Fig. 4) hint to a relative subsidence of the northern flank of the Buivydžiai fault during pre-Quaternary time.

Recent vertical ground motions were documented by repeated measurements of the first-class geodetic leveling network of Lithuania (Paršeliūnas et al., Reference Paršeliūnas, Sacher and Ihde2000; Petroškevičius et al., Reference Petroškevičius, Putrimas, Krikštaponis, Būga, Neseckas, Obuchovski, Stepanovienė, Tumelienė, Viskontas and Zigmantienė2005; Zakarevičius et al., Reference Zakarevičius, Šliaupa, Anikėnienė, Dėnas and Šliaupienė2008). According to the map of recent movements of Lithuania, the rate of background vertical movements ranges from –3.5 mm/yr to +2.5 mm/yr (Zakarevičius, Reference Zakarevičius1994; Anikėnienė, Reference Anikėnienė2008). The Turmantas-Vilnius geodetic leveling line crosses the entire study area from northeast to southwest (Fig. 11). Generally, it shows a relative subsidence trend to the south. The Buivydžiai zone is distinct in changing the trend of vertical movements from systematically southward subsidence increase north of the fault to little subsidence variations south of the fault.

Figure 11. Annual vertical ground motion rates (mm/yr) defined by geodetic leveling measurements, first-class Turmantas-Vilnius geodetic leveling benchmarks (annual motion rates are shown).

Assuming average vertical displacement of 8 m of the Daumantai Formation along the tectonic zone over ca. 780 kyr, the average rate of vertical Quaternary movements can be calculated as 0.01 mm/yr. This is tenfold lower compared to the rate (0.19 mm/yr) of the 2.3 m vertical shift of the Baltic Lake terrace that formed ca. 12,000 years ago along the west-east trending fault close to Būtingė village in northwesternmost Lithuania (Šliaupa et al., Reference Šliaupa, Bitinas and Zakarevičius2005).

DISCUSSION

Late Pleistocene and Holocene seismicity in the Baltic region

Signatures of the late Pleistocene and early Holocene earthquakes have been reported from several sites in the Baltic region. They are especially abundant in the Fennoscandian shield that was subject to maximum glacial isostatic perturbations. In most cases, the documented earthquakes were induced by isostatic rebound following ice sheet retreat. It is, therefore, commonly thought that earthquakes are triggered by rapid changes in the vertical pressure caused by the diminishing of thick land-ice masses (Muir-Wood, Reference Muir-Wood, Gregersen and Bashman1989; Ardvidsson, Reference Ardvidsson1996).

In contrast, the Buivydžiai SSDS were described in proglacial lake sediments deposited in front of the advancing ice sheet during the last Weichselian glaciation phase, and therefore are not related to isostatic rebound processes. They correlate to seismites described in the aforementioned Slinkis outcrop. Similar proglacial seismites were recognized at Rügen Island (northeasternmost Germany) (Pisarska-Jamroży et al., Reference Pisarska-Jamroży, Belzyt, Börner, Hoffmann, Hüneke, Kenzler, Obst, Rothe and van Loon2018). The liquefaction-induced deformations were described in the glaciolacustrine and glaciofluvial sediments that were deposited, based on previous OSL (optically stimulated luminescence) dating, just before advancement of the Scandinavian ice sheet during the last glacial maximum, which is similar to the Buivydžiai seismites. This implies that advancing ice sheets can also activate faults and increase seismic activity. During ice sheet expansion, an extensional stress regime is established in the upper half of Earth's crust in front of the ice sheet, while compression increases below the ice sheet due to vertical loading (Allen, Reference Allen2013).

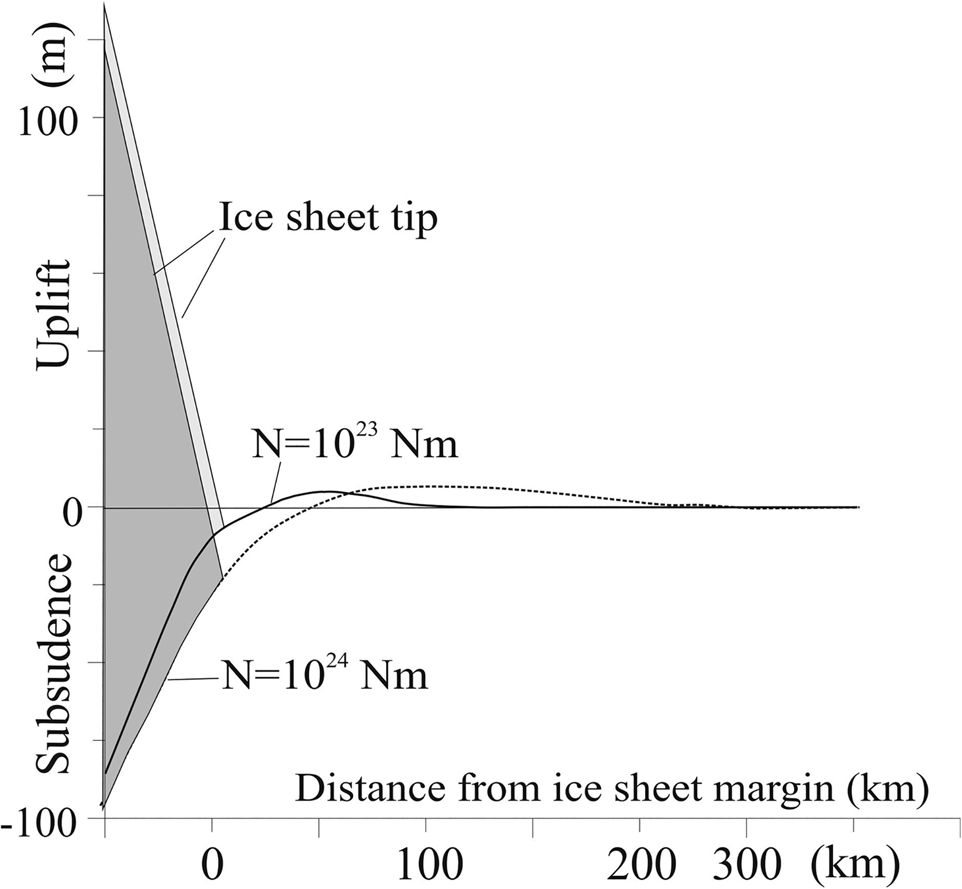

Glacial isostatic subsidence and the succeeding isostatic rebound considerably change the stress field and associated fault activation in Earth's crust (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Sauber and Rose2000; Zoback and Grollimund, Reference Zoback and Grollimund2001). Šliaupa (Reference Šliaupa2002b) carried out 2D geodynamic modeling of the last glaciation and deglaciation for the Baltic region, and considered two models of ice sheet geometry (convex-shape and concave-shape margin). The concave margin model does not show any significant changes in the stress regime in front of the ice mass, and therefore cannot be considered as an important factor for increase in seismic activity. The convex-shaped ice sheet margin model implies upwarping of the forebulge in frontal area of the ice sheet (Fig. 12). Two models of the lithosphere (low rigidity [N = 1023 Nm] and high [rigidity N = 1024 Nm]) were calculated. The high rigidity model is in concert with the rheological modeling results of the lithosphere. Šliaupa and Hoth (Reference Šliaupa, Hoth, Harf, Björk and Hoth2011) modeled ~40 km of effective elastic thickness (EET) of the lithosphere in the study area, which is close to that calculated from gravity-topography correlation for southeasternmost Latvia by Poudjom Djomani et al. (Reference Poudjom Djomani, Fairhead and Griffin1999). Modeling of the stress regime of the rigid lithosphere (Fig. 13) suggests differential horizontal extension up to -23 MPa in front of the ice sheet, while compressional regime is modeled bellow the ice sheet. The shear stress can be calculated as high as -11.5 MPa in the marginal area. It should be noted that the ice sheet suppresses fault activity in the glaciated area due to vertical ice loading (Klemann and Wolf, Reference Klemann and Wolf1999). Therefore, earthquake activation in front of the advancing ice sheet is an expected phenomenon, as exemplified in the Rügen, Slinkis, and Buivydžiai seismic events. It is notable that both sites are located at a similar northern latitude (54°25′N and 54°52′N, respectively) in relation to advancement of a mature thick ice sheet. The extensional regime of fault activation and related seismicity is, therefore, the most likely mechanism.

Figure 12. Modeling of the lithosphere (surface) bending under ice sheet load in the near-margin area (after Šliaupa, Reference Šliaupa2002b). Rigidity of the lithosphere is assumed to be N = 1023 Nm and N = 1024; maximum thickness of the ice is assumed to be 2500 m in Fennoscandia; horizontal axis marks distance from the ice margin (mark 0 km).

Figure 13. Stress field (MPa) in Earth's upper crust and bending amplitude (m) due to glacial loading of the rigid lithosphere (after Šliaupa, Reference Šliaupa2002b). Horizontal axis is scaled (km).

Field observations indicate that the minimum required earthquake magnitude to cause sediment seismic deformation should be no less than M = 4.5 for most susceptible soils (Green and Bommer, Reference Green and Bommer2019), but in most cases M ≥ 6.0 (Papadopoulos and Lefkopoulos, Reference Papadopoulos and Lefkopoulos1993). There are several empirical equations relating maximum distance of the liquification site to fault rapture and earthquake epicenter and magnitude. Based on 10 relationship equations (see Maurer et al., Reference Maurer, Green, Quigley and Bastin2015 for review), the maximum distance of an earthquake of magnitude M = 6.0 to the liquefaction site clusters is ~20 km. For larger earthquake magnitudes, the maximum distance to the liquefaction site increases (e.g., for magnitude M = 6.5, the maximum distance is ~30 km). The maximum distance is also sensitive to other parameters, such as the epicentral depth, the source mechanism of the earthquake, soil properties depending on grain size and packing of the sediment, duration of shaking, etc. Empirical data derived from Sweden indicated that a shallow-focus earthquake of magnitude M = 6.6 may cause liquefaction features ~20 km from the epicenter (Lagerbäck and Sundh, Reference Lagerbäck and Sundh2008).

The liquefaction effect of thrust faults can be traced over larger distances compared to normal faults (Castilla and Audemard, Reference Castilla and Audemard2007). The latter regime is suggested for the Buivydžiai earthquake. The earthquake can be alternatively related to the Vilnius fault mentioned above. This fault is suspected to have initiated the Gudogai earthquake on December 28, 1908. It is located only 30 km south of the Buivydžiai site. However, no other evidence of latest Quaternary seismites has been documented in the region, despite a number of good-quality outcrops available that would indicate seismic activity of the Buivydžiai fault. It also hints to the shallow depth of the hypocenter.

It should be noted that liquefaction features may be recognized at much larger distances compared to brittle-deformation structures. Seismically induced Quaternary gravel fractures have been documented largely close (0.5–2.0 km) to major faults in the Outer Carpathians in south Poland (Tokarski et al., Reference Tokarski, Świerczewska, Lasocki, Quoc Cuong, Strzelecki, Olszak, Kukulak, Alexanderson and Krąpiec2020). No brittle tectonic deformations were identified either in the Buivydžiai outcrop or elsewhere in the Eastern Baltic region, suggesting a more distant location of the earthquake hypocenters to the liquefaction sites.

The displacement amplitude can be also suggested for the Buivydžiai fault. Statistical correlation of earthquake magnitude and fault displacement implies that for magnitude M = 6.5, the maximum displacement can be expected to be as moderate as 0.4–0.6 m for normal faults (Bonilla et al., Reference Bonilla, Mark and Lienkaemper1984). The amplitude of the Buivydžiai fault is of 5–8 m in the Daumantai Formation, therefore liquefaction features recognized in the Buivydžiai outcrop reflect only a small portion of the total amplitude of the total fault rupture during the Quaternary time.

Isostatic rebound after deglaciation leads to inversion of the stress pattern in Earth's upper crust, especially increasing the horizontal compression in the formerly glaciated area. It explains much of the higher recent seismic activity in Latvia and Estonia compared to Lithuania because the rebound effect remains active for a long time in formerly thick ice-covered regions. This isostatic uplift takes place in two distinct phases: (1) the initial uplift after deglaciation is rapid and is ‘elastic’ in nature, whereas (2) the long phase is related to slow viscous mantle flow (Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Davis, Scherneck, Milne, Vermeer, Mitrovica and Bennett2002).

Formation of the seismites

The liquified sandy silt is dominated by non-plastic fine-grained sediment, and content of plastic clay minerals is only 6.5–8.0% (Table 1). The liquefaction resistance/susceptibility is controlled by several factors. Field and laboratory observations indicate a significant drop in the cyclic resistance of soils containing non-/low-plastic fines (FC) >35% (Green et al., Reference Green, Olsson and Polito2006). Cyclic resistance ratio decreases significantly within the FC fraction interval 35–55%, and changes little with increasing silt content >55% (Green et al., Reference Green, Olsson and Polito2006), which is close to the silt fraction content in the studied sandy silt (~50–54%). This explains brittle fragmentation (pseudonodules) of the clean sandy interlayers.

Formation of seismites at the Buivydžiai site also was facilitated by the peculiar distribution of lithologies in the Quaternary cover. Some persistent activity of alluvial deposition points to recurrent incision of the paleovalley, which is cut into the substrates of both the Paleozoic rocks and Quaternary sediments (Fig. 4). The paleovalleys may significantly increase the seismic tremor intensity due to larger seismic wave amplitude amplification in sandy lithologies compared to till deposits. Ground seismic engineering studies in northeast Lithuania indicate that the seismic wave velocity is 206–216 m/s in glacial till at the depths of 3–6 m, and increases downwards to ~430 m/s at the depths of 15–25 m, while seismic velocity at this depth range varies from 100–150 m/s in sandy lithologies (Gadeikis et al., Reference Gadeikis, Dundulis, Žaržojus, Gadeikytė, Urbaitis, Gribulis and Šliaupa2012, Reference Gadeikis, Dundulis, Žaržojus, Gadeikytė, Urbaitis, Gribulis, Šliaupa and Gabrielaitis2013).

CONCLUSIONS

Peculiar structures bearing distinct features of soft-sediment deformation structures (SSDS) were identified in the uppermost Quaternary glaciolacustrine sediments in the Buivydžiai outcrop in east Lithuania. Kidney-shaped pseudonodules of sand are disrupted by extrusions of liquified sandy silt, the grain size composition of which is prone to liquefaction.

The sandy silt layer is covered by a till that was deposited during the Late Weichselian ice advance (MIS 2), which implies formation of seismites in front of the advancing mature Fennoscandian ice sheet ca. 25–24 ka BP. It is a quite a peculiar setting of glacially induced seismites because the main seismic activity phase commonly takes place during ice sheet retreat, which results in postglacial isostatic rebound. The Buivydžiai earthquake was related to an increase of fault activity in the associated forebulge that formed in front of advancing ice sheet. An extensional regime should have been established in this setting.

The dense borehole network identified the presence of a NW-SE trending fault in the study area in proximity to the Buivydžiai outcrop. Although the fault is suggested in the crystalline basement underlaying the sedimentary cover, it is best mapped in the lowermost Quaternary lacustrine sandy sediments of the Daumantai Formation that accumulated to the south of the advancing Fennoscandian ice sheet. The vertical displacement of the Buivydžiai fault is ~5–8 m. Furthermore, persistent activity of the Buivydžiai fault is evinced by a sharp change in the deposition environment of the Quaternary sediments. Sandy lithologies predominate to the north, while glacial till predominates in the southern flank of the fault.

No other soft-sediment deformation structures (SSDS) were identified in the study area, which suggests limited extent of seismically induced liquefaction. It also suggests moderate earthquake magnitude (M = 6.0–6.5) and a shallow hypocenter depth of the earthquake, which is typical for the forebulge setting (Singh, Reference Singh2003). The Buivydžiai fault preserved seismic activity until recently, as evinced by the Bystritsa earthquake (magnitude M = 3.8–4.0), registered December 29,1908, just 12 km from the Buivydžiai site. Geodetic leveling indicates that the Buivydžiai fault has been active during recent time.

The Buivydžiai case indicates that active faults (in terms of the seismic safety) are present in the Baltic region and can be detected using different techniques, which is an important message for the management of the nuclear facilities operating or being at the construction stage in the region (e.g., Ignalina NPP radioactive waste storage facilities, Astravets NPP in Belarus close to the Lithuanian border, Baltic NPP in Kaliningrad District).

So far, six sites of soft-sediment deformation structures (SSDS), attributed to late Pleistocene seismic activity, have been identified in and close to Lithuania. It is notable that two of them (Slinkis and Buivydžiai) were documented in proglacial sandy silty sediments deposited just before they were covered by the ice sheet, while four other SSDS sites were documented in the postglacial sediments (Fig. 2). It is postulated that isostatic rebound is a stronger seismic triggering mechanism compared to geodynamic processes initiated in front of advancing ice sheet. The Lithuanian case suggests that the ice sheet effect on Earth's geodynamic response may be more complex than previously thought. Ice sheet maturity also could be an important parameter. It is notable that seismites of the Buivydžiai, Slinkis, and Rügen sites mark the marginal part of the ice sheet at its most mature stage when glacially induced tectonic forces tentatively reached their peak intensity.

Acknowledgments

The authors cordially thank Dr. Andrzej Piotrowski, an anonymous reviewer, Senior Editor Nicholas Lancaster, and Associate Editor Jaime Urrutia Fucugauchi for their constructive remarks on the manuscript.