INTRODUCTION

The transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture occurred independently in western and eastern Eurasia between 10,500 and 6000 cal yr BP (Lev-Yadun et al., Reference Lev-Yadun, Gopher and Abbo2000; Tanno and Willcox, Reference Tanno and Willcox2006; Barton et al., Reference Barton, Newsome, Chen, Wang, Guilderson and Bettinger2009; Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Qin, Zheng, Zhao, Chen, Hosoya and Sun2009). Determining the forces driving the emergence of agriculture in the early Holocene has attracted a large amount of archaeological and paleoclimatic research in western Eurasia (Childe, Reference Childe1928, Reference Childe1936; Binford, Reference Binford1968; Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen, Reference Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen1992), but only recently has the emergence of agriculture in the eastern part of Eurasia, East Asia, started to become clear. Recent studies suggest that humans domesticated foxtail millet (Setaria italic) and broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum) in China’s Yellow River valley around 10,000 cal yr BP (Crawford and Shen, Reference Crawford and Shen1998; Cohen, Reference Cohen2011). Archaeobotanical and isotopic studies suggest that humans first cultivated millet during the Peiligang period (8500–7000 cal yr BP) at several sites in Henan Province, located in north-central China (Zhao, Reference Zhao2005; The Gansu Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, 2006; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Crawford, Liu and Chen2007). However, fully sedentary Neolithic societies did not emerge until the early Yangshao period (7000–6000 cal yr BP) (Qin, Reference Qin2012; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Xia and Zhang2014; Zhao, Reference Zhao2014). As the chronology of the emergence of agriculture becomes more resolved in China, archaeologists will have more opportunities to explore the reasons driving the shift in subsistence practices that eventually created the sedentary, agricultural way of life seen in the archaeological record of northern China’s late Neolithic period (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Jones, Zhao, Liu and O’Connell2012; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Wan, Perry, Lu, Wang, Zhao and Li2012).

Many archaeologists have claimed that climate change is a primary force driving people to practice agriculture (Bar-Yosef, Reference Bar-Yosef2011; Hou and Xiao, Reference Hou and Xiao2011; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Dong, Zhang, Liu, Jia, An and Ma2015a), but climate change has a wide range of effects on societies that vary from region to region. For example, changes in climatic conditions can shift regional-scale ecological and geomorphic regimes, requiring humans to adopt new subsistence strategies (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Xu, Jing, Tang, Li and Tian2010). Multiproxy paleoenvironmental data can potentially reveal how variations in geomorphology and vegetation relate to climatic fluctuations, helping build more accurate models of the paleoenvironmental changes that influenced human activities and eventually resulted in the emergence of agriculture. Therefore, understanding the relationship between climate change and the emergence of agriculture requires multiple types and scales of data that integrate changes in vegetation, geomorphology, climate, and culture.

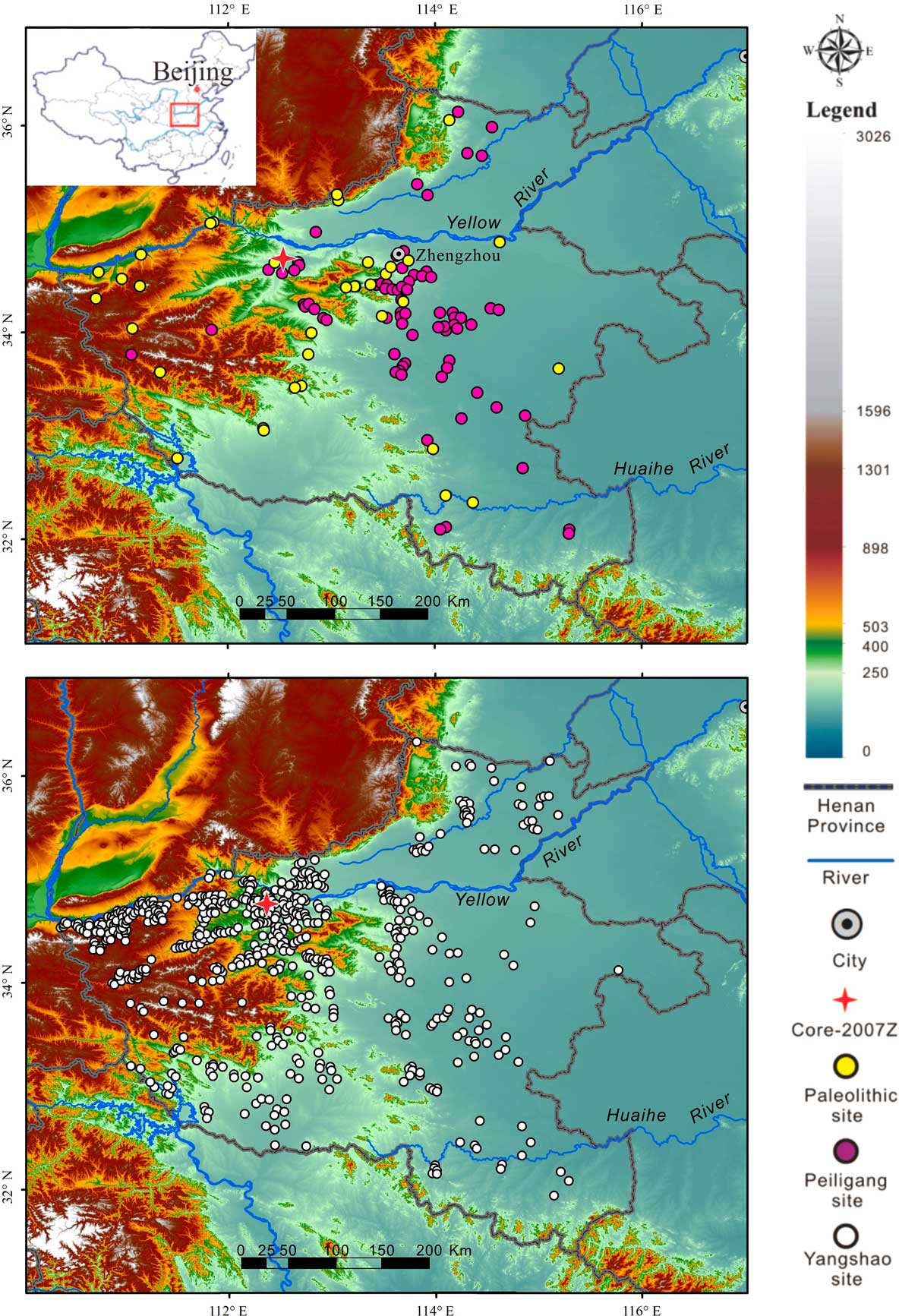

To better understand the relationship between the emergence of agriculture in northern China and changes in geomorphology and vegetation, we analyzed pollen, magnetic susceptibility (MS), and grain size from sediment cores taken within the Luoyang Basin. The Luoyang Basin is one of the centers of the earliest agriculture in China, and previous archaeological work has comprehensively documented many archaeological sites in the basin that capture the time period when societies transitioned from mobile hunting and gathering to sedentary agriculture (Liu, Reference Liu2004; Erlitou Team of Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences [IA, CASS], 2005). Most Paleolithic sites are located in the low mountains and foothills (Fig. 1), and early agricultural sites dating to the Peiligang (8500–7000 cal yr BP) and Yangshao (7000–5000 cal yr BP) periods are distributed on the lower plains and along river valleys (Fig. 1). To date, archaeologists have found several Peiligang sites and more than 100 Yangshao sites in the Luoyang Basin (Erlitou Team of IA, CASS, 2005). Archaeologists have not found any Paleolithic sites in the lower Luoyang Basin despite intensive archaeological investigations (Liu, Reference Liu2004; Xu, Reference Xu2004). The shifting spatiotemporal pattern of archaeological sites suggests a major reorganization in the way humans interacted with their environment during the transition from the early to middle Holocene. However, the current understanding of landscape evolution of the Luoyang Basin during the Holocene is primarily based on three profiles done along the loessic hills and riverbanks (Rosen Reference Rosen2007, Reference Rosen2008; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chen and Wang2007; Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Macphail, Liu, Chen and Weisskopf2017). In this article, we compare our results from a core taken within the Luoyang Basin with other paleoclimatic records to reconstruct the early to middle Holocene environmental history of the basin as a way to examine the interrelationship between climate, geomorphology, and the emergence of agriculture.

Figure 1 (color online) Distribution of Paleolithic, early–middle Neolithic sites in Henan Province, north-central China (based on Bureau of National Cultural Relics, 1991). Paleolithic period (before 10,000 yr BP); Peiligang period (8500–7000 yr BP); Yangshao period (7000–6000 yr BP).

STUDY AREA

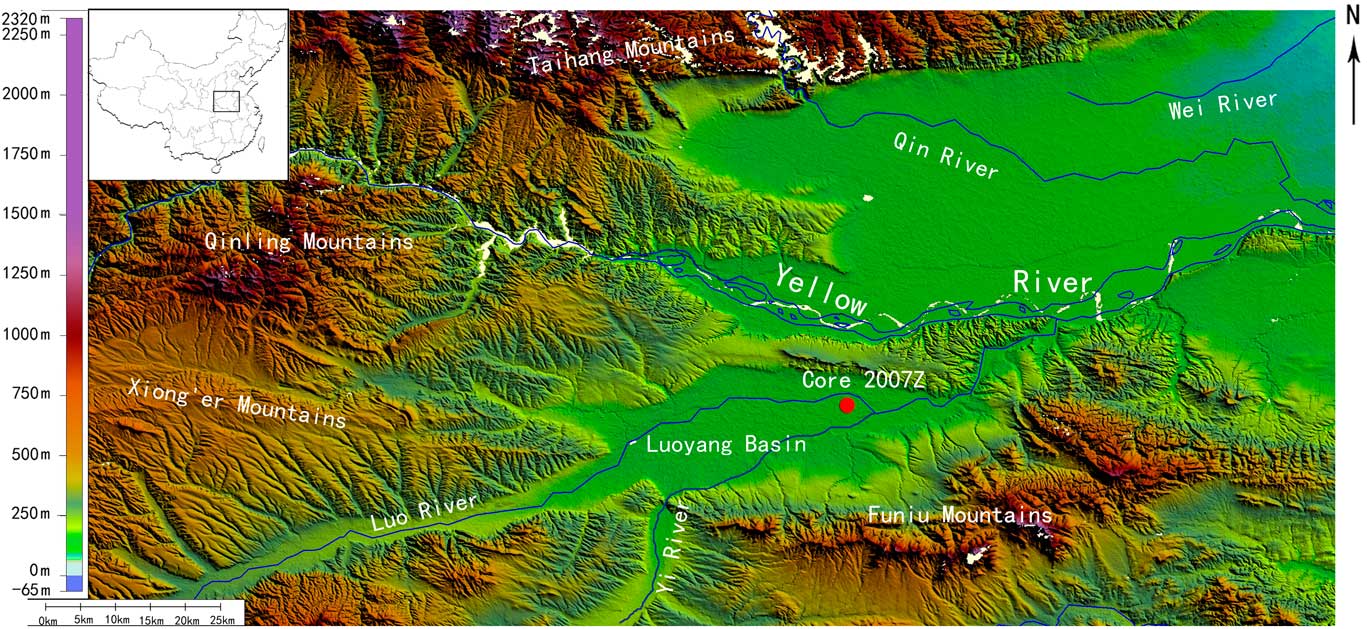

The Luoyang Basin is located in the middle reaches of the Yellow River in the western part of Henan Province (Fig. 2). It is part of the broad physiographic region known as the Central Plains, which is characterized by temperate forests. In nearby mountainous areas, common vegetation types include coniferous and deciduous forest and shrubs, including Pinus armandii, Pinus massoniana, Abies chensiensis, and Betula albo-sinensis. At lower elevations, Ulmus pumila, Populus tomentosa, and Salix matsudana are predominant. In wetlands, Salix sinopurpurea and Typha are present (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Wang, Wang and Jia1989). At present, modern and historical agriculture, primarily consisting of wheat, corn, and soybeans, has almost completely replaced the naturally occurring vegetation. The Luoyang Basin is cold in winter (0–3°C) and hot in summer (25–27°C). The mean annual precipitation is about 600 mm, the majority of which falls from May to September. Interannual variations of summer precipitation are intense, and severe droughts are recorded throughout history (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Zheng and Ge2007; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Zhao, Yang and Wang2012).

Figure 2 (color online) Map of the Luoyang Basin in north-central China and location of core 2007Z.

The Luoyang Basin is surrounded by the Loess Plateau to the north, the Funiu Mountains to the south and east, the Qinling Mountains to the west. The foothills to the north and west are covered with loess. Originating in the southern and western mountain ranges, the Yi River and Luo River meet in the eastern part of the Luoyang Basin to form the Yiluo River. The Luoyang Basin is the floodplain of the Yi River and the Luo River. As a result, the basin has accumulated a large amount of sediment derived from the surrounding mountain ranges. The Yi River has an average discharge of about 3.6×106 m3/day, and the peak discharge reaches 3000 m3/s. About 90% of the floods in the Luoyang Basin occur in July and August when the summer monsoon reaches this area (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Huang, Zhou, Pang, Zha, Guo, Zhang and Zhao2015). According to historical records, the Luoyang Basin has experienced more than 100 recorded flood events, with particularly strong floods dating to AD 223, 1761, 1898, and 1954. In prehistory, flood sediments from a profile in the Luoyang Basin suggest that an extraordinary flood happened around 3100–3000 cal yr BP (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Huang, Zhou, Pang, Zha, Guo, Zhang and Zhao2015).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In 2007, we drilled two sediment cores (2007Z2 and 2007Z3) (34°41′33.5″N, 112°41′8.3″E; 116 m above sea level) from the first terrace of the Yiluo River with a mechanical corer. The drilling site is located about 1.5 km to the north of the Luo River, 4 km to the south of the Yi River (Figs. 1 and 2), and about 1–3 m above the Luo River. The two cores reached a depth of 1060 cm. The two cores are only 50 cm apart and have almost identical stratigraphy. In total, 244 samples for grain-size and MS analyses were collected from core 2007Z3 at 2.5 cm intervals, and 122 pollen samples were collected from core 2007Z3 at 5 cm intervals. We recovered two wood samples and two bulk organic samples from core 2007Z3, as well as five charcoal samples from core 2007Z2 for radiocarbon dating. We only focus on the sediment core below 4.25 m because a sedimentation hiatus between ~6000 and 4000 cal yr BP (Xia et al., Reference Xia, Zhang and Zhang2014) and late Holocene human activities that have influenced landform evolution (Storozum et al., Reference Storozum, Mo, Wang, Ren, Zhang and Kidder2017) and ecological composition (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Xu, Jing, Tang, Li and Tian2010) complicate the pollen and sedimentologic analyses.

In total, nine samples were collected from two cores for accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) 14C dating (see Table 1). The radiocarbon samples were dated at Peking University’s Department of Archaeology. The dates occur in chronological order (Table 1). Because the parallel cores are very close to each other and have identical stratigraphy, we combined the radiocarbon dates from the two cores into a single data set (core 2007Z). Finally, we generated an age-depth model using Bacon, a Bayesian age-modeling software program (Blaauw and Christen, Reference Blaauw and Christen2011) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 (color online) Age-depth model for core 2007Z in Luoyang Basin, north-central China, generated by the Bayesian age-modeling software Bacon (Blaauw and Christen, Reference Blaauw and Christen2011) with IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al., Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey and Buck2013).

Table 1 Accelerator mass spectrometry 14C ages and modeled calibrated ages for Core 2007Z, Luoyang Basin, north-central China.

For pollen analysis, approximately 100 g of dry sample was sieved with 280 μm mesh to remove the gravel-sized fraction. Then, we followed the pretreatment method of Faegri and Iversen (Reference Faegri and Iversen1989), including chemical treatments with 10% HCl, 10% NaOH, and 40% HF, and sieved with fine mesh (size 6 μm). The final concentrates were mounted in a glycerol gel. A tablet of Lycopodium clavatum (about 6000 grains) was added to each sample before the chemical treatments to enable calculation of pollen concentrations (Maher, Reference Maher1981). The pollen grains were counted with a light microscope at 400× magnification. For each sample, the total number of pollen grains counted ranged from 76 to 438 grains. The pollen sum used for pollen percentage calculations excluded aquatic pollen and spores. Pollen diagrams were plotted using Tilia software (E. Grimm of Illinois State Museum, Springfield, IL, USA). We used CONISS to zone the pollen diagram through constrained cluster analysis based on the percentages of the terrestrial pollen types (Grimm, Reference Grimm1987).

Sedimentologic analyses include granulometry and MS. Grain size was analyzed with a Malvern Master Sizer 2000. The samples were prepared with H2O2 (10%) to remove organic matter, HCl (10%) to remove carbonates, and (NaPO3)6 to aid dispersion of the particles (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Xiao, Nakamura, Liu and Inouchi2005). Grain-size data in alluvial sediments can be used as an index of the intensity of water flow, where high values (coarse sediments) reflect strong water flow and low values (finer sediments) reflect weak water flow (e.g., Royse, Reference Royse1968; Walling and Moorehead, Reference Walling and Moorehead1987). We used a Bartington MS2 magnetic susceptibility meter to measure high-frequency MS (Dearing, Reference Dearing1994). The MS of fluvial sediments can reflect hydrodynamic conditions (Ji and Xia, Reference Ji and Xia2007; Zhou and Zhao, Reference Zhou and Zhao2007). Higher MS values are found in well-developed soils, and lower MS values are usually associated with an increase in carbonate content (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Bloemendal, Wang, Li and Oldfield1997). Grain size is a proxy for environmental dynamics, and MS has quite different values within aquatic or terrestrial sediments in this area. Both of these methods allow us to infer changes in both sedimentary processes and climatic conditions (Nádor et al., Reference Nádor, Lantos, Tóth-Makk and Thamó-Bozsó2003).

RESULTS

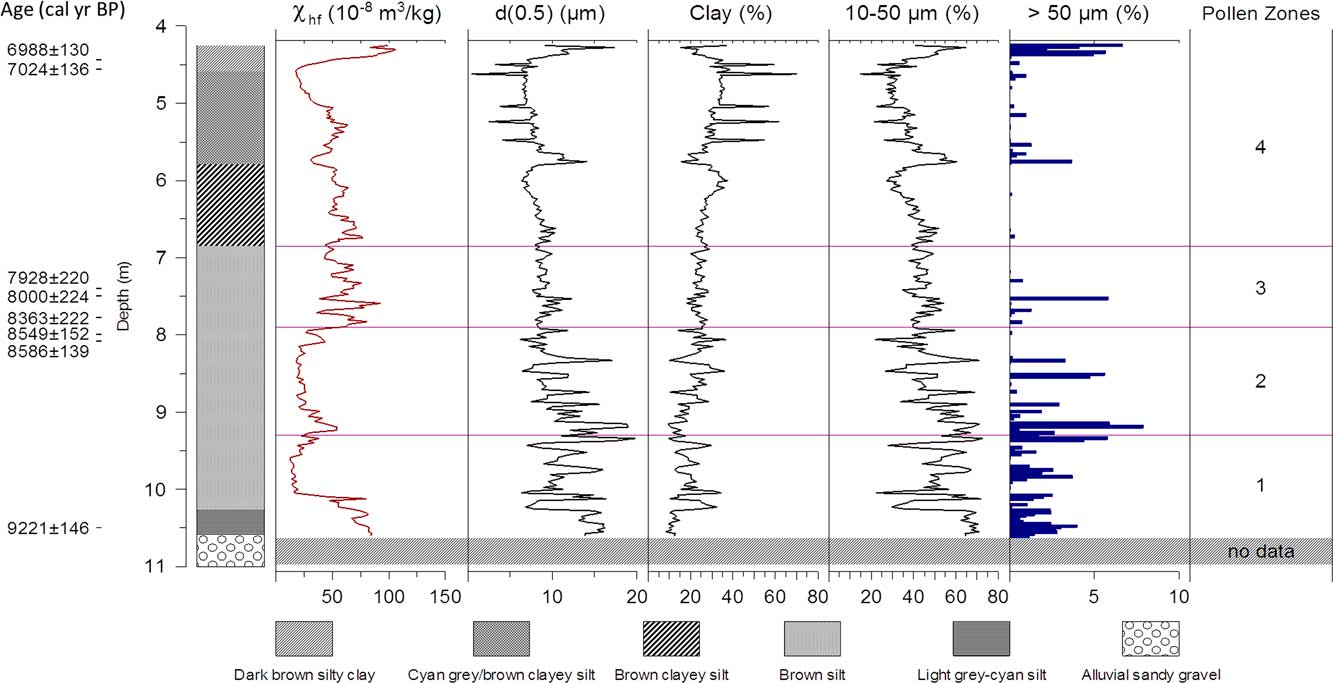

In the field, we divided the core (11 m to 4.25 m) into six lithologic layers based on visual color and grain size at depth: (1) 11–10.6 m, an alluvial sandy gravel layer (no proxy data); (2) 10.6–10.25 m, a cyan-gray or brown clayey silt layer, possible lacustrine sediments; (3) 10.25–6.85 m, a yellow to brown clayey silt layer with gray blocky peds; (4) 6.85–5.78 m, a brown clayey silt layer; (5) 5.78–4.62 m, a cyan gray/brown clayey silt layer; and (6) 4.62–4.25 m, a dark-brown silty clay layer (see Fig. 4, the lithology of the core). We excluded the lowest gravel layer for further analyses.

Figure 4 (color online) High-frequency magnetic susceptibility, median grain size, content of clay, coarse silt, and fine sand for core 2007Z, Luoyang Basin, north-central China.

The lower part of the core (10.6–4.25 m) spans the period from 9230 to 6920 cal yr BP. Although our radiocarbon ages are derived from both bulk organic sediments and charcoal, they are comparable. AMS 14C analysis of bulk sediments may yield younger ages than macrofossils from the same depths (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Amundson and Trumbore1996), but comparison of the radiocarbon ages derived from bulk sediments and macrofossil dates from core 2007Z3 suggests that the dating results from the two bulk organic samples are reliable. Using these ages as chronological anchors, we calculated that the sedimentation rates changed from 0.08 cm/yr to 0.38 cm/yr (Table 1, Fig. 3).

The MS of the sediments is variable (Fig. 4). The high frequency MS (χhf) values at depth 10.6–10 m are quite high (mean 70×10−8 m3/kg), and from 10 to 8 m the MS values become much lower (mean 30×10−8 m3/kg). MS values increase to about 50×10−8 m3/kg at depth of 8–5 m and decrease again from 5 to 4.4 m. Both the median grain size and sand-silt-clay fraction grain-size data indicate that the sediments become finer up-column (Fig. 4).

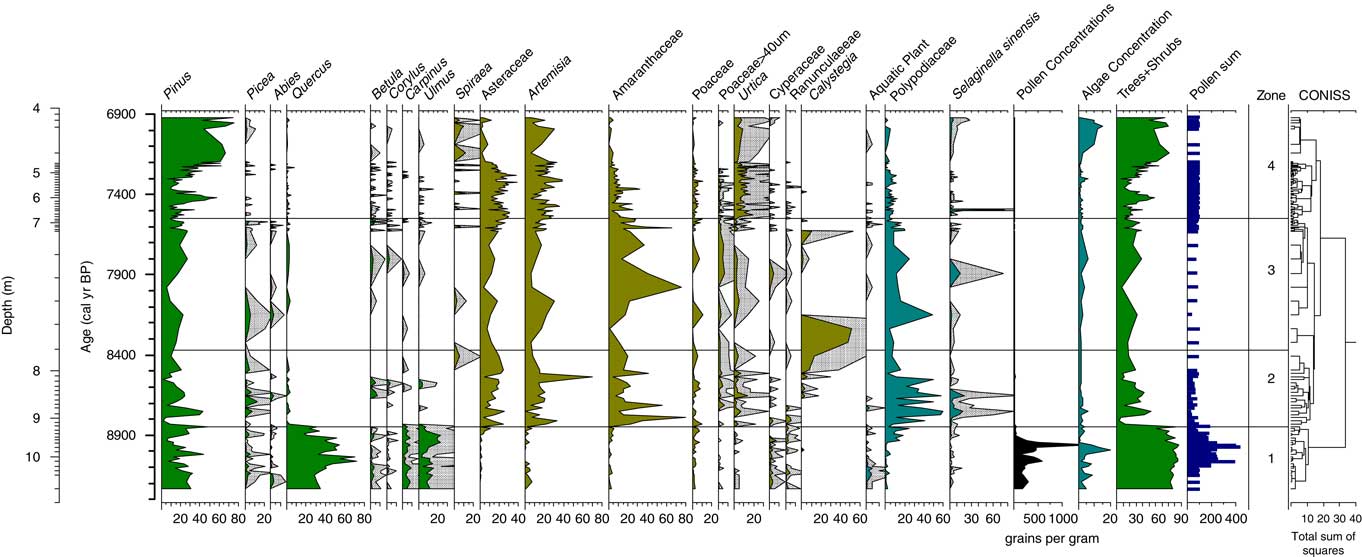

We identified a total of 67 pollen taxa in the 122 samples from core 2007Z3. The dominant tree pollen types include Pinus, Picea, Quercus, Carpinus, and Betula, and the main herbs include Asteraceae, Artemisia, Amaranthaceae (=Chenopodiaceae), Poaceae, and Urtica. The algae types include Concentricystes and Zygnema. Four pollen zones could be recognized based on the CONISS analysis (Fig. 5). We summarize the results of the sedimentologic and palynological analysis below 4.25 m and group them into four zones according to pollen zones (Figs. 4 and 5).

Figure 5 (color online) Pollen diagram for core 2007Z, Luoyang Basin, north-central China (shaded area is a five times exaggeration).

Zone 1 (10.6–9.31 m; 9230–8850 cal yr BP)

This zone includes a light gray-cyan silt lacustrine layer found at a depth of 10.6–10.25 m and a brown silt layer found at the depth of 10.25–9.31 m. These two clear lithologic layers have different MS values. The mean value of χhf is 77.1×10−8 m3/kg in the lower section, and these values decreased to 26.6×10−8 m3/kg at the upper section (10.25–9.31 m). The mean value of Md (median grain size) for zone 1 is 12.1 μm, and it varied from 19.8 to 6.4 μm. The mean values calculated for the content of clay (<5 μm), coarse silt (10–50 μm), and fine sand (>50 μm) for zone 1 were 17.4%, 55.3%, and 1.3%, respectively. Above 10.25 m, the particle size, especially the silt content, has larger fluctuations than the lower section with less coarse silt. The constant change in χhf and Md values at depth ~10.25 m in zone 1 reflects changes in the sedimentary environment and climatic condition.

Zone 1 pollen assemblages are dominated by high counts of arboreal pollen, with arboreal taxa such as Quercus (mean 38.1%), Pinus (21.1%), Ulmus (10.7%), and Carpinus (4.2%) accounting for 80% of the pollen sum. Herb pollen composes only 13.2% (mean) of the pollen sum, including Artemisia (1.8%), Poaceae (2.6%), and Amaranthaceae (1.6%). The high values of broad-leaved tree and shrub pollen suggest a warm and humid climate with continuous forest cover. Aquatic plants (including Typha, Myriophyllum, and Nymphoides) and algae, an assemblage consistent with a lacustrine to swamp environment, were relatively abundant in the lower part of this zone.

Zone 2 (9.31–7.9 m; 8850–8370 cal yr BP)

This zone is a brown clayey silt layer. The mean value of χhf in zone 2 is as low as 28.3×10−8 m3/kg with a general trend toward lower values (Fig. 4). The mean value of Md in zone 2 is 10.6 μm, with a general trend toward lower values as well. The mean values calculated for the content of clay, coarse silt, and fine sand in zone 3 were 21.0%, 49.1%, and 0.9%, respectively (Fig. 4).

In zone 2, Quercus, Ulmus, and Pinus decreased to 0.6%, 0.3%, and 9.7%, respectively, whereas Amaranthaceae, Artemisia, Asteraceae, and Poaceae increased to 15.6%, 12.6%, 9.7%, and 3.2%, respectively. Herb pollen dominates the pollen assemblages, reaching 61–96.3% (mean 51.7%). Arboreal pollen only accounted for 14.3% of the pollen sum. The decrease in tree pollen (especially broad-leaved tree taxa) and increase in herb pollen suggest that the regional vegetation changed from forest to open forest steppe vegetation. Another main feature of this pollen zone is that it contains the highest fern spore content (mean 34.1%) of the whole sequence (Fig. 5).

Zone 3 (7.9–6.86 m; 8370–7550 cal yr BP)

Zone 3 has the same visual lithologic features as zone 2. The χhf increased in zone 3 with large variations, and its mean value is 58.7×10−8 m3/kg. The mean value of Md in zone 3 is 9.0 μm, and median grain size decreased with less variation. The mean values calculated for the content of clay, coarse silt, and fine sand in zone 3 were 24.0%, 43.8%, and 0.2%, respectively (Fig. 4). The smaller and relatively consistent grain size and reduced amounts of coarse silt and fine sand suggest that flooding events did not occur during this period.

In zone 3, Pinus increased to 13.5%. Herbs remained dominant, accounting for an average 60.0% of the pollen sum. Arboreal pollen accounted for 6.0–28.1% (mean 19.0%) of the pollen sum. Most of the arboreal pollen is Pinus, with low abundances of broad-leaved deciduous taxa. The average percentage of Polypodiaceae spores (13.8%) is lower than zone 2, possibly indicating drier soil conditions.

Zone 4 (6.86–4.25 m; 7550–6920 cal yr BP)

This zone contains three lithologic layers (Fig. 4). The mean value of χhf in this zone is 49.2×10−8 m3/kg. Both χhf and grain size have a declining trend until 4.45 m when both χhf and Md synchronously increase (after 7200 cal yr BP). The mean value of Md decreased to 8.0 μm. The mean percentages of clay, coarse silt, and fine sand in this zone are 30.5%, 37.9%, and 0.3%, respectively.

In zone 4, Pinus has an increasing trend with an average 29.7%, and arboreal pollen increases to 33.4%. Herb pollen accounts for 59.6% of the pollen sum. Both Amaranthaceae and Asteraceae decrease after ~7200 cal yr BP. The higher percentages of tree and shrub pollen after 7200 cal yr BP indicate a wetter climate and recovering vegetation. A notable feature of this pollen zone is an increase in the abundance of Urtica pollen, with consistently high values in zone 4 spectra (mean 8.5%).

DISCUSSION

Our multiproxy palynological and sedimentary data from the cores taken in the Luoyang Basin enable us to reconstruct changes in geomorphology and vegetation within the context of archaeological cultures and climatic fluctuations in northern China. In this section, we first present our findings within the context of broad climatic and cultural processes. Then, we use the palynological record from the Luoyang Basin to discuss changes in vegetation. Finally, we discuss our findings within the context of the emergence of agriculture in northern China during the early to middle Holocene.

Early–Middle Holocene climate background and local environmental context

Analyses of lacustrine sediments, loess deposits, ice cores, and stalagmites have shown that from 11,700 to 9000 cal yr BP, climatic conditions became warmer and more humid in northern China (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Lü, Negendank, Mingram, Luo, Wang and Chu2000; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Yao, Thompson, Henderson and Davis2002; Qin et al., Reference Qin, Yuan, Cheng, Lin, Zhang, Wang, Edwards, Hua and Ran2005; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Wang, Cheng, Hardt, Edwards, Kong and Wu2010; Marcott et al., Reference Marcott, Shakun, Clark and Mix2013; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xu, Chen, Birks, Liu, Zhang and Jin2015b). However, a cold and dry climatic event around 8400–8000 cal yr BP interrupted these relatively warm and humid conditions (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Wu, Si, Liang, Nakamura, Liu and Inouchi2006; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Chen, Zhang, Ma, Zhu, Li and Xu2008; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Meyers, Jia, Zheng, Xue, Wang and Xie2013). This event is considered a regional manifestation of the 8.2 ka event recorded in the Greenland ice core (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Dyke, Hillaire-Marcel, Jennings, Andrews, Kerwin and Bilodeau1999; Dykoski et al., Reference Dykoski, Edwards, Cheng, Yuan, Cai, Zhang, Lin, Qing, An and Revenaugh2005; Qin et al., Reference Qin, Yuan, Cheng, Lin, Zhang, Wang, Edwards, Hua and Ran2005; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Meyers, Jia, Zheng, Xue, Wang and Xie2013). After this brief period of cold and dry conditions from around 8000 to 3000 cal yr BP, the climate became even warmer and wetter in northern China with average temperatures in the region 2–4°C higher than today (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Kong, Wang, Tang, Wang, Yao, Zhao, Zhang and Shi1992; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Xiao, Li, Tian and Nakagawa2010; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Zhang and Chen2014; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xu, Chen, Birks, Liu, Zhang and Jin2015b).

Changes in the climate of northern China had geomorphic effects in the Luoyang Basin. As a result of the warm and wet climatic conditions around 10,000 cal yr BP, stream incision created the Yiluo River’s terrace T2 (Xia et al., Reference Xia, Zhang and Zhang2014). Afterward, once these streams stabilized, they became an aggrading system, accumulating sediment on the floodplain during the early Holocene. At around 7000 cal yr BP, the warm and wet conditions of the middle Holocene likely caused another stream incision event that formed terrace T1 (Xia et al., Reference Xia, Zhang and Zhang2014). However, it is unclear how the changes in the streams in the Luoyang Basin changed from 10,000 cal BP to 7000 cal BP.

In our core sequence (Fig. 4), the MS and grain-size data suggest a change in hydrology during this period of the early Holocene. From 9230 to 8370 cal yr BP, the high percentage of sand-sized grains reflects an increasing flood frequency. Unlike the silt-sized loess found throughout this region that contains virtually no sand-sized grains (Zhang and Xia, Reference Zhang and Xia2011), flood sediments contain a much higher percentage of sand-sized grains. The relatively low MS values likely indicate an anoxic environment. The increase in sand-sized grains and low MS values of sediments found in the cores suggest that frequent flooding may have created marshes on the ancient floodplain, now terrace T1. The shift to smaller grain size (less sand content) and higher MS values at 8370 cal yr BP may represent reduced flood frequency. The change in flood frequency may be related to the 8.2 ka global event, before the warming from 8000 to 3000 cal yr BP led to river incision that created terrace T1. Archaeologists have found ash pits dating to the Yangshao (7000–5000 cal yr BP) and Longshan (5000–4000 cal yr BP) periods within terrace T1, indicating that ancient people lived on the river terrace T1 after it formed (Erlitou Team of IA, CASS, 2005).

Vegetation history in the Luoyang Basin during the early to middle Holocene

When using pollen to reconstruct past vegetation, it is important to assess potential changes in pollen source area over time. For example, the pollen source area of a pond or wetland is different from that of an alluvial context (e.g., Hall, Reference Hall1989; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Carpenter and Walling2007). Pollen found within small ponds without river input usually reflects the local vegetation (Debusk, Reference Debusk1997; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Tian, Bunting, Li, Ding and Cao2012), but pollen preserved in alluvial sediments may come from both local vegetation and upstream sources (Zhu et al, Reference Zhu, Xie, Cheng, Chen and Zhang2003; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Carpenter and Walling2007). A palynological study of surface shore sediments from the lower reaches of the Yellow River found that herbaceous pollen types (e.g., Amaranthaceae, Artemisia, Poaceae, and Astereaceae) mainly originate from grasses on floodplains and beaches (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Yang, Wang, Wu and Meng1995, Reference Xu, Yang, Wu, Meng and Wang1996). Given the inferred changes in hydrology, this pollen record from the Luoyang Basin likely reflects both shifts in vegetation composition and a change in pollen source area. The pollen from lacustrine-alluvial sediments (9230–8850 cal yr BP) represents both local and regional vegetation, whereas the pollen assemblages from the floodplain (8850–8370 cal yr BP) and loessic sediments (8370–7200 cal yr BP) reflect mainly local vegetation with smaller contributions from the regional vegetation. Here we discuss changes in vegetation composition based on the fossil pollen data from 9230 to 6920 calyrBP. We divide our discussion into four stages (Fig. 5).

Stage 1, deciduous forest (9230–8850 cal yr BP)

The high content of Quercus, Ulmus, and Carpinus pollen types indicates a broad-leaved deciduous forest. Pinus trees likely grew on the plain or in the mountains. The composition of forests in the Luoyang Basin at this time is similar to that revealed by other pollen records from northern and central China. Pollen assemblages from Gonghai Lake also contain the pollen of broad-leaved deciduous Ulmus and Betula trees that dates to the early Holocene (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Chen, Zhang, Cao, Li, Li, Li, Chen, Liu and Wang2017), and the pollen records in the Dajiuhu peats suggest that broad-leaved deciduous forest also occurred in mountainous areas (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Ma, Yu, Tang, Zhang and Lu2010). A strong Asian monsoon (Dykoski et al., Reference Dykoski, Edwards, Cheng, Yuan, Cai, Zhang, Lin, Qing, An and Revenaugh2005) and high temperatures (Fig. 6a) (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Meyers, Jia, Zheng, Xue, Wang and Xie2013; Marcott et al., Reference Marcott, Shakun, Clark and Mix2013) likely influenced early Holocene forest composition.

Figure 6 Comparison of 2007Z record, Luoyang Basin, north-central China, with other regional and global environmental records. (a) Synthesized Northern Hemisphere (30°–90°N) temperature record for the Holocene (solid red line) (Marcott et al., Reference Marcott, Shakun, Clark and Mix2013); temperature reconstruction based on pollen data at Dajiuhu peat site in central China (solid black line) (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Chen, Zhang, Ma, Zhu, Li and Xu2008). (b) Pollen-based annual precipitation reconstructed from Gonghai Lake, northern China (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xu, Chen, Birks, Liu, Zhang and Jin2015b). (c) Asian monsoon intensity from Dongge Cave record (Dykoski et al., Reference Dykoski, Edwards, Cheng, Yuan, Cai, Zhang, Lin, Qing, An and Revenaugh2005). (d) Tree pollen percentages from 2007Z3 of this study. (e) Median diameter grain-size (Md) curve from 2007Z of this study. (f) Box plot of elevations of the archaeological sites. (g) Site density in the Luoyang Basin and surrounding area (based on data from Bureau of National Cultural Relics, 1991). m asl, meters above sea level; VPDB, Vienna Pee Dee belemnite. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Stage 2, grassland dominated (8850–8370 cal yr BP)

The decrease in tree pollen and the increase in herb pollen indicate the development of a grassland ecosystem in the Luoyang Basin. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that humans conducted wide-scale forest clearance, the paucity of archaeological sites predating the Peiligang period (before 8500 cal yr BP) makes this explanation unlikely (Qiao, Reference Qiao2010). A climatic explanation is also unlikely because both the regional temperature and precipitation did not change much during this period (Fig. 6a–c). Therefore, we argue that changes in local geomorphology and hydrology (such as changes of river course) altered both pollen sources and assemblages. For example, the high percentage of Polypodiaceae spores in stage 2 indicates a generally wet and warm climate, similar to China’s subtropical zones (Lin, Reference Lin2000). This type of environment is consistent with the higher percentage of sand-sized grains found on an aggrading floodplain environment.

Stage 3, grassland with some Pinus trees (8370–7550 cal yr BP)

In this stage, the Pinus pollen percentage slightly increases and the percentage of broad-leaved deciduous taxa pollen (Quercus, Ulmus, and Carpinus) remains low (Fig. 5). At the same time, the percentage of Amaranthaceae pollen increases, indicating a much drier climate. In Northern China, deciduous forests began to decline around 8500 cal yr BP (Li and Liang, Reference Li and Liang1985; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Yu, Chen, Zhang and Yang2009). Compared with the previous stage, the reduced abundance of Polypodiaceae and increase in Calystegia indicate drier soils, consistent with the small grain size and higher MS associated with dry climate. Paleoclimate data from across the region indicate cool and dry conditions during this time period (Fig. 6) (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Chen, Zhang, Ma, Zhu, Li and Xu2008; Marcott et al., Reference Marcott, Shakun, Clark and Mix2013). The 8.2 ka event appears in the Dongge Cave record, and a period of weak monsoon activity in China began at ~8400 cal yr BP that lasted several hundred years (Dykoski et al., Reference Dykoski, Edwards, Cheng, Yuan, Cai, Zhang, Lin, Qing, An and Revenaugh2005; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cheng, Edwards, He, Kong, An, Wu, Kelly, Dykoski and Li2005) (Figs. 5 and 6a and c).

Stage 4, human-disturbed vegetation (7550–6920 calyrBP)

In comparison with stage 3, the decline in Amaranthaceae pollen and the increase in Asteraceae and Artemisia pollen indicate a wetter climate, a trend that matches the increase in precipitation reconstructed from Lake Daihai (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Xiao, Li, Tian and Nakagawa2010). One of the main changes during this period is the greater abundance of Urtica pollen, an indicator of human activities (Li et al., Reference Li, Cui and Zhou2008). The elevated values of Urtica pollen suggest an increase in human-caused disturbance to the natural vegetation. It is also notable that the greater percentage of tree pollen after ~7200 cal yr BP is accompanied by an increase in sand-sized grains, indicating stronger floods that may be associated with a wetter climate in northern China (Fig. 6b) (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Xiao, Li, Tian and Nakagawa2010; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xu, Chen, Birks, Liu, Zhang and Jin2015b).

Environmental forcing on shifts in human subsistence strategies

Previous studies have suggested that during the early and middle Holocene (10,000–7000 cal yr BP) the humid climate (Dykoski et al., Reference Dykoski, Edwards, Cheng, Yuan, Cai, Zhang, Lin, Qing, An and Revenaugh2005) promoted the emergence of early agriculture and Neolithic archaeological cultures like the Yangshao (7000–6000 cal yr BP) (Han, Reference Han2015). Although multidisciplinary studies have broadened the archaeological understanding of the transition from hunting and gathering to sedentary agriculture in China (e.g., Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chen, Bettinger, Barton, Ji, Morgan and Wang2010; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Ma, Li, Yu, Stevens and Zhuang2015; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Lu, Zhang, He and Huan2016), the specific ways that climate has influenced the development of agriculture in China remains unclear. Our paleoenvironmental reconstructions of the small Luoyang Basin may provide insights into how the variability of local ecologies might have influenced shifting human subsistence strategies.

According to recent work at several late Neolithic sites in north-central China, foragers occupied the Luoyang Basin area around 50,000 cal yr BP (Wang and Wang, Reference Wang and Wang2014). Site density during the late Paleolithic period (>10,000 cal yr BP) was low (Figs. 2 and 6g). To date, most known Paleolithic sites (before 10,000 cal yr BP) in Henan Province are located at higher elevations along the foothills of mountains (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Hunt and Jones2009; Ren et al., Reference Ren, Lemoine, Mo, Kidder, Guo, Qin and Liu2016) (Figs. 2 and 6e). This pattern suggests that Paleolithic groups lived primarily in the forest and forest-steppe transition zone, an area that was probably favorable for hunting and gathering (Chen, Reference Chen2006). Based on our data, the frequently flooding and marshy conditions in the lower basin would not have been suitable for human occupation in the early Holocene (before 8350 cal yr BP).

When the East Asian summer monsoon weakened and climate became colder and drier around 8400 cal yr BP (Dykoski et al., Reference Dykoski, Edwards, Cheng, Yuan, Cai, Zhang, Lin, Qing, An and Revenaugh2005; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cheng, Edwards, He, Kong, An, Wu, Kelly, Dykoski and Li2005; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Chen, Zhang, Ma, Zhu, Li and Xu2008; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Meyers, Jia, Zheng, Xue, Wang and Xie2013), the Luoyang Basin changed from a swampy floodplain to an upland dry loess environment. After about 8370 cal yr BP, the lower basin became more suitable for hunting and agriculture because of the nutrient-rich soils laid down by earlier floods. Around this time, humans probably moved down from the piedmont areas on the mountain slope into the basin to gather newly available plants and hunt animals (Fig. 6f).

Although hunting and gathering was probably the main subsistence strategy during the early Peiligang period (e.g., Hu et al., Reference Hu, Ambrose and Wang2006, Reference Hu, Ambrose and Wang2007), we hypothesize that the newly available stable land surface after 8370 cal yr BP provided extensive and suitable areas for millet cultivation for the first time during human occupation of the Luoyang Basin. As indicated by higher site density than the Paleolithic stage (Fig. 6f), population increased during the Peiligang period, probably as a result of the transition to a food production subsistence strategy (Fig. 6g). Recent archaeobotanical studies from Peiligang sites in north-central China have recovered carbonized millet remains (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Crawford, Liu and Chen2007; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wong, Yao, Zhang, Zhou, Fang and Cui2011).

Precipitation in Northern China increased after ~7700 cal yr BP and reached a maximum around 7000–6000 cal yr BP (Fig. 6b) (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Xiao, Li, Tian and Nakagawa2010; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xu, Chen, Birks, Liu, Zhang and Jin2015b). Temperature also remained relatively high during this time period (Marcott et al., Reference Marcott, Shakun, Clark and Mix2013). Regional Neolithic cultures increasingly depended on intensive millet-based agriculture (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xu, Chen, Birks, Liu, Zhang and Jin2015b; Han, Reference Han2015). As the regional climate became wetter and flooding events became frequent, Yangshao sites started to appear across a broader range of elevation than during the previous Peiligang and Paleolithic periods (Fig. 6f). Although people during the Paleolithic and Peiligang were likely more mobile than those that lived during the Yangshao period, we suggest that, because of the increased investment in agricultural production, the settlement patterns during the Yangshao period reflected the need of people to relocate to higher elevations to avoid occasional flooding (Figs. 4 and 6e). Likewise, it was beneficial for people to settle at lower elevations to take advantage of access to water (Fig. 6f).

Changes in the environment influenced human activities, but human activities also influenced the environment (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Xu, Jing, Tang, Li and Tian2010; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Liu, Dong, Qiang, Bai, Zhao and Chen2017). After the development of agriculture during late Peiligang period, indicators of human activities like Urtica pollen increased significantly, suggesting that humans started to affect natural vegetation through agricultural activities around 7000 cal yr BP. In the upland areas of the southern part of the Luoyang Basin, Rosen (Reference Rosen2007, Reference Rosen2008) and Rosen et al. (Reference Rosen, Macphail, Liu, Chen and Weisskopf2017) suggest that later during the Yangshao period, people practiced an intensive form of rice agriculture that eventually increased the rates of sedimentation into the Luoyang Basin.

CONCLUSION

We have attempted to understand the relationships between climate, geomorphology, vegetation, and culture in northern China during the early and middle Holocene by conducting palynological and sedimentologic analyses on sediment cores from the Luoyang Basin. Our pollen data indicate that a deciduous forest existed in the area between 9230 and 8850 cal yr BP. Steppe prevailed from 8850 to 7200 cal yr BP. Afterward, the vegetation transitioned to steppe with some trees. Our grain-size analysis suggests that flooding was frequent in the Luoyang Basin before ∼8370 cal yr BP. From around 8370 to 7530 cal yr BP, the grain-size, MS, and pollen data indicate that the swampy floodplain of the Luoyang Basin became more like a dry, upland loessic environment. After ∼7200 cal yr BP, the increasingly wet and humid climate increased flood frequency. Our results suggest that the swampy floodplain in the Luoyang Basin was not suitable for long-term habitation before 8370 cal yr BP. Afterward, upland loess conditions became more suitable for millet-based agriculture during the Peiligang and Yangshao periods. Around 7000 cal yr BP, the appearance of Urtica pollen coincides with an increased presence of Yangshao period settlements in the Luoyang Basin, suggesting human activities had an increased influence on the vegetation composition of the Luoyang Basin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the constructive comments from Dr. Wyatt Oswald and two anonymous reviewers. We thank Dr. Guoliang Chen; Hongzhang Wang for the field work; and Dr. Aifeng Zhou, Dr. Decheng Liu, and Yaping Li for editing some of the figures. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41501216, 41671077, and 41171168), the Major program of the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 12&ZD151), the National Key Technology R&D Program of China (No. 2013BAK08B02), the MOE Project of Humanities and Social Sciences (No. 14YJCZH207), the New Beginning Project of BUU (No. 2K201214), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. lzujbky-2015-k09).