INTRODUCTION

The British Quaternary record is one of the best stratigraphically resolved terrestrial archives in the world (Candy et al., Reference Candy, Rose, Coope, Lee, Parfitt, Preece and Schreve2010). A combination of litho-, morpho-, and biostratigraphy, in association with absolute dating techniques, means that it is now possible to routinely correlate interglacial deposits with individual Marine Oxygen Isotope Stages (MIS)/substages over the past 450,000 yr (Bridgland, Reference Bridgland2000; Schreve, Reference Schreve2001a; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Rose, Coope, Lee, Parfitt, Preece and Schreve2010, Reference Candy, Schreve, Sherriff and Tye2014). For the early middle Pleistocene, 780,000–450,000 yr, such resolution is not possible, mainly because this time interval lies beyond the range of most dating techniques (Preece and Parfitt, Reference Preece and Parfitt2000, Reference Preece and Parfitt2012; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Rose, Coope, Lee, Parfitt, Preece and Schreve2010; Penkman et al., Reference Penkman, Preece, Bridgland, Keen, Meijer, Parfitt, White and Collins2011). However, a combination of biostratigraphy and amino acid racemisation (AAR) allows interglacial deposits to be separated into discrete stratigraphic groups and correlations with MIS proposed (Penkman et al., Reference Penkman, Preece, Bridgland, Keen, Meijer, Parfitt, White and Collins2011; Preece and Parfitt, Reference Preece and Parfitt2012; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015). As well as allowing important palaeoclimatic questions to be investigated, such as the diversity of Pleistocene interglacial environments, the stratigraphic resolution of the British sequence allows the rich Palaeolithic record of this region to be placed into a chronostratigraphic framework (Penkman et al., Reference Penkman, Preece, Bridgland, Keen, Meijer, Parfitt, White and Collins2011). The British Palaeolithic record is particularly long and diverse, with evidence for human occupation going back to ca. 1 Ma (Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Ashton, Lewis, Abel, Coope, Field and Gale2010), with well-documented evidence for clear cultural transitions across this period (Fig. 1; Ashton et al., Reference Ashton, Lewis and Stringer2011; Pettitt and White, Reference Pettitt and White2012). Importantly, it is the robust chronostratigraphic framework of the British terrestrial sequence that allows the timing of these changes/transitions to be established.

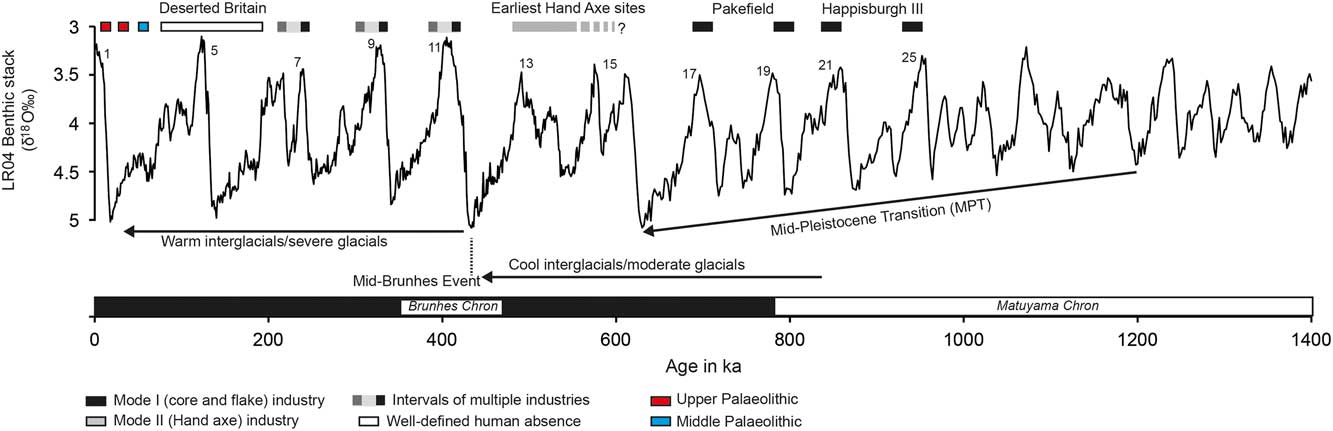

Figure 1 (color online) A comparison between the LR04 stacked benthic δ18O record and the British Palaeolithic record. Two possible time periods are shown for Pakefield and Happisburgh II as the absolute age of these sites are not clear (for discussion, see Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Barendregt, Breda, Candy, Collins, Coope and Durbidge2005, Reference Parfitt, Ashton, Lewis, Abel, Coope, Field and Gale2010; Westaway, Reference Westaway2011). Candy et al. (Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015) have argued that the first appearance of Mode II archaeology is during Marine Oxygen Isotope Stage (MIS) 13 or, at the earliest, late MIS 15. The major climatic events/tranisitions during this period are shown below the benthic record.

A key research question is the relationship between patterns of climate forcing and human occupation in this region (see Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Barendregt, Breda, Candy, Collins, Coope and Durbidge2005, Reference Parfitt, Ashton, Lewis, Abel, Coope, Field and Gale2010; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015). The prevailing model is one of abandonment of the British Isles by early humans during glacial stages and reoccupation during interglacial/temperate episodes (Ashton and Lewis, Reference Ashton and Lewis2002; Ashton et al., Reference Ashton, Lewis and Stringer2011). It is, however, important to highlight that over the period within which humans have occupied this region, a number of major climatic transitions occurred, modifying the pattern of glacial/interglacial cyclicity and the intensity of both glacial and interglacial periods (Fig. 1). During the early–middle Pleistocene transition (EMPT; 1.2 to 0.6 Ma), the periodicity of glacial-interglacial cycles shifted from 41 to 100 ka, giving rise to very asymmetric climatic cycles with long and severe glacial periods (Pisias and Moore, Reference Pisias and Moore1981; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Archer, Pollard, Blum, Rial, Brovkin, Mix, Pisias and Roy2006; McClymont et al., Reference McClymont, Sosdian, Rosell-Melé and Rosenthal2013). A second step occurred at the mid-Brunhes event (MBE; ca. 450 ka), which represents an increase in the magnitude of both glacial cooling and interglacial warmth from MIS 12 onwards (Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Kuijpers and Troelstra1986; Lang and Wolff, Reference Lang and Wolff2011; Candy and McClymont, Reference Candy and McClymont2013). Sea level reconstructions also indicate higher sea level during peak interglacial conditions after MIS 12 (Bintanja and van de Wal, Reference Bintanja and van de Wal2008; Elderfield et al., Reference Elderfield, Ferretti, Greaves, Crowhurst, McCave, Hodell and Piotrowski2012; Spratt and Lisiecki, Reference Spratt and Lisiecki2016). The implication of such climatic transitions is that the characteristics of glacial/interglacial cycles and, therefore, the potential environmental extremes and stresses experienced by the earliest humans to occupy northwest Europe may be very different from that which was experienced by human populations in the late middle or late Pleistocene (Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Barendregt, Breda, Candy, Collins, Coope and Durbidge2005; 2011; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Silva and Lee2011; Hosfield, Reference Hosfield2011).

The major limitation of the British terrestrial record is that there is no long-term, continuous climatic record with which the archaeological sequence can be compared. Consequently, there is a limited understanding of the impact of transitions such as the EMPT and MBE and their environmental implications for early humans. The British terrestrial record is highly fragmented. Interglacial deposits (primarily fluvial channel fills/overbank deposits, short lacustrine sequences, and raised beach sediments) typically provide high-resolution records of short intervals of time (Candy et al., Reference Candy, Rose, Coope, Lee, Parfitt, Preece and Schreve2010). This allows the palaeoenvironment of discrete phases of human occupation to be constructed but provides limited information on the nature of the climate cycles, both their duration and magnitude, that these populations would have experienced (Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015). Consequently, it is difficult to place the Palaeolithic record into the context of long-term climate evolution.

Most studies have compared the British archaeological record with benthic δ18O records (i.e., Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Barendregt, Breda, Candy, Collins, Coope and Durbidge2005, Reference Parfitt, Ashton, Lewis, Abel, Coope, Field and Gale2010), an approach that is clearly problematic because such sequences record an “average” of global ice volume, rather than climate change in any particular region per se (or specifically climate change in the region of the British Isles), and are complicated by changes in the temperature of the bottom water masses (Sosdian and Rosenthal, Reference Sosdian and Rosenthal2009; Elderfield et al., Reference Elderfield, Ferretti, Greaves, Crowhurst, McCave, Hodell and Piotrowski2012). Although the North Atlantic contains numerous sea surface temperature (SST) records, the majority of these are not relevant to Britain because either (1) they do not occur at latitudes and longitudes that are appropriate to the British Isles (Naafs et al., Reference Naafs, Hefter, Acton, Haug, Martinez-Garcia, Pancost and Stein2012), (2) they reconstruct SST at too low resolution to be relevant to the palaeoclimatic questions that are being asked (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Herbert, Brown, Raymo and Haywood2009), or (3) they do not span the entirety of the time interval in question (e.g., the last 1 Ma; Wright and Flower, Reference Wright and Flower2002). There is currently no single long, high-resolution record of climate change available that is appropriate with which to compare the British archaeological record.

This article aims to address this issue by reinvestigating two records that have the potential to provide a long SST record for the northeast Atlantic. Both site M23414 (Kandiano and Bauch, Reference Kandiano and Bauch2003) and Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Site 980 (Wright and Flower, Reference Wright and Flower2002) contain foraminifera that allow mean annual plus winter and summer SSTs to be reconstructed at a resolution of at least 1.2 ka and occur at a latitude and longitude that is relevant to understanding the palaeoclimate of the British Isles. M23414 spans the interval 0–0.5 Ma (Kandiano and Bauch, Reference Kandiano and Bauch2003) while the foraminifera record of Site 980 spans 0.5–1 Ma (Wright and Flower, Reference Wright and Flower2002); consequently, the two records allow the last 1 Ma of climate history of this region to be discussed in detail. The article has two main aims: first, to highlight the main patterns/trends in SST records over glacial/interglacial cycles over the past 1 million yr; second, to compare and contrast these patterns with the record of human occupation that is seen in the British terrestrial sequence. The article concludes by discussing, through an integration of the terrestrial and marine record, the major changes in glacial/interglacial forcing that occurred in this region over the past 1 Ma and the relevance of these changes to understanding the environmental drivers of human occupation.

PALAEOCLIMATE IN THE NORTHEAST ATLANTIC AND THE EARLY HUMAN OCCUPATION OF NORTHWEST EUROPE

Palaeolithic occupation of northwest Europe

There is abundant evidence for human occupation in northwest Europe, particularly the British Isles (Fig. 1), during the early middle Pleistocene (EMP; 780–450 ka) (Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Barendregt, Breda, Candy, Collins, Coope and Durbidge2005, Reference Parfitt, Ashton, Lewis, Abel, Coope, Field and Gale2010; Hosfield, Reference Hosfield2011; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015), with more limited evidence for occupation in the late early Pleistocene (>780 ka). In Britain, the two oldest sites contain Mode I archaeology (core and flake tools) and are suggested to date to 950–850 ka (Happisburgh III) and ca. 700 ka (Pakefield) on the basis of lithostratigraphy, biostratigraphy, AAR, and palaeomagnetic dating (Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Barendregt, Breda, Candy, Collins, Coope and Durbidge2005, Reference Parfitt, Ashton, Lewis, Abel, Coope, Field and Gale2010; Penkman et al., Reference Penkman, Preece, Bridgland, Keen, Meijer, Parfitt, White and Collins2011). Although there is little debate over these being the oldest archaeological sites in Britain, there has been discussion over their precise age, with Westaway (Reference Westaway2011) arguing that both sites could be incorporated into a stratigraphic model that places them in separate substages of MIS 15. Less controversial is the presence of a large number of sites containing Mode II archaeology (Acheulian hand axes) in deposits that predate the MIS 12 glaciation but, on the basis of biostratigraphic, AAR, and geochronological lines of evidence, correlate to late within the EMP, MIS 13, or late MIS 15 (Hosfield, Reference Hosfield2011; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015). From MIS 12 onwards, the evidence for Palaeolithic occupation becomes more abundant and follows a relatively clear pattern of human occupation of the British Isles during warm MIS (interglacial/interstadial events) and abandonment during cold MIS (White and Schreve, Reference White and Schreve2000; Ashton and Lewis, Reference Ashton and Lewis2002). However, it is now becoming increasingly clear that each interglacial/warm stage has a distinct pattern of human occupation and lithic technology (i.e., White and Schreve, Reference White and Schreve2000). This pattern persists until the last interglacial/glacial cycle when there is an absence of humans in Britain during MIS 5e but evidence for occupation in the middle of the last glacial period (MIS 3; Ashton and Lewis, Reference Ashton and Lewis2002; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Ashton and Jacobi2011).

Multiproxy reconstructions from the earliest occupation sites (1–0.5 Ma) indicate that humans were inhabiting western Europe under a range of environments from interglacial climates that were significantly warmer than modern-day Britain (i.e., the “Mediterranean” environment recorded at Pakefield; Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Barendregt, Breda, Candy, Collins, Coope and Durbidge2005; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Rose and Lee2006; Coope, Reference Coope2006) through to more boreal late interglacial or interstadial climates (i.e., at Happisburgh III and many of the Acheulian sites; Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Ashton, Lewis, Abel, Coope, Field and Gale2010; Hosfield, Reference Hosfield2011; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015). The age of these sites spans key intervals in the long-term evolution of Pleistocene climate (Lisiecki and Raymo, Reference Lisiecki and Raymo2005). The interval 1–0.5 Ma, which spans the earliest known appearance of humans in northwest Europe and the widespread adoption of hand axe technologies, is associated with the EMPT and the increasing strength of glacial cycles (Pisias and Moore, Reference Pisias and Moore1981; Lisiecki and Raymo, Reference Lisiecki and Raymo2005; Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Sosdian, White and Rosenthal2010). In particular, the first evidence of “Hudson Strait” Heinrich(-like) events in the North Atlantic occurred during MIS 16, indicating a step change in continental ice sheet extent/dynamics (Hodell et al., Reference Hodell, Channell, Curtis, Romero and Röhl2008; Naafs et al., Reference Naafs, Hefter, Ferretti, Stein and Haug2011, Reference Naafs, Hefter and Stein2013). These early archaeological sites occur prior to the MBE and, therefore, potentially in association with “muted” climate cycles (i.e., “cool” interglacial periods; Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Kuijpers and Troelstra1986; Lang and Wolff, Reference Lang and Wolff2011) with moderate sea level high stands from MIS 19 to 13 (Fig. 3; Bintanja and van de Wal, Reference Bintanja and van de Wal2008; Elderfield et al., Reference Elderfield, Ferretti, Greaves, Crowhurst, McCave, Hodell and Piotrowski2012; Spratt and Lisiecki, Reference Spratt and Lisiecki2016).

The implication that the early occupation of northwest Europe occurred in a context of subdued climate cycles, compared with later occupation in the past 400 ka, is heavily based on the correlation of the terrestrial record with LR04 (and other benthic δ18O records) and, hence, a globally averaged signal. It is becoming increasingly evident that transitions such as the EMPT and MBE are spatially variable in both their impact and expression (i.e., Candy and McClymont, Reference Candy and McClymont2013; McClymont et al., Reference McClymont, Sosdian, Rosell-Melé and Rosenthal2013), and, in the absence of a long climatic record from the region of the British Isles, it cannot be assumed that global records faithfully represent environmental shifts by which early humans in northwest Europe would have been affected.

Climate records from the North Atlantic

Although a wealth of SST records exist for the North Atlantic (Fig. 1), the time interval that they span and the resolution of the palaeoclimate data they contain means that few are appropriate for understanding the long-term climate history of the British Isles (see Candy and McClymont, Reference Candy and McClymont2013). As the aim of many of the studies that have generated these records has been the investigation of the EMPT, these temperature records either (1) finish at 0.5 Ma, with no SST data for MIS 12 onwards (Wright and Flower, Reference Wright and Flower2002), or (2) record key climatic intervals at such a low resolution that it cannot be assumed that their thermal regime and climatic structure is reliably characterised (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Herbert, Brown, Raymo and Haywood2009).

In the first category are sites such as Site 980, which contain a high-resolution (0.6 ka) foraminifera SST record of the interval of the period 0.99–0.5 Ma but no comparable record for the interval 0.5–0 Ma (Wright and Flower, Reference Wright and Flower2002). An example of the second category are sites such as ODP 982, which has an alkenone-based SST record that extends from the present back into the Pliocene (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Herbert, Brown, Raymo and Haywood2009). However, the resolution of this record across the last 1 Ma is low (4.5 ka) and is also highly variable. For example, although data resolution during MIS 11 is 1.8 ka, during MIS 13 it is 7 ka. Although high-resolution SST records do exist for the North Atlantic, they occur at much lower latitudes than that of the British Isles; these include U1313 with a resolution of 0.4 ka (Naafs et al., Reference Naafs, Hefter, Acton, Haug, Martinez-Garcia, Pancost and Stein2012) and the high-resolution records generated from a number of cores, extending back into the EMP, from around the Iberian margin (Martrat et al., Reference Martrat, Grimalt, Shackleton, de Abreu, Hutterli and Stocker2007; Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Voelker, Grimalt, Abrantes and Naughton2011, Reference Rodrigues, Alonso-Garica, Hodell, Rufino, Naughton, Grimalt, Voleker and Abrantes2017).

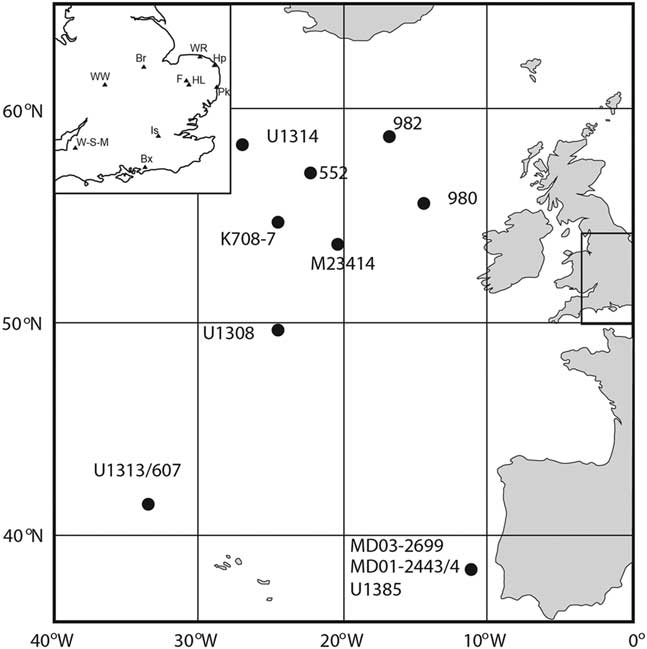

Early studies of Pleistocene SST variability in the North Atlantic spliced different marine core records to produce composite palaeoclimate records spanning the last 1 Ma (Ruddiman et al., Reference Ruddiman, Shackleton and McIntyre1986, Reference Ruddiman, Raymo, Martinson, Clement and Backman1989). Although such an approach makes a number of assumptions about the relative comparability of long-term ocean circulation at the different sites in question, it does allow a more detailed investigation into long-term climate variability to be made. Furthermore, such an approach does allow for the possibility of constructing a long-term, high-resolution SST record for the area of the northern Atlantic relevant to the British Isles as two records are found in this region that, when combined, provide a high-resolution foraminifera-based SST record for the past 1 Ma. These records are (1) M23414 (53°32ʹN, 20°17ʹW), which spans the interval 0.5–0 Ma and has an SST record at a resolution of 1 sample per 1.2 ka (Kandiano and Bauch, Reference Kandiano and Bauch2003), and (2) Site 980 (55°29ʹN, 14°42ʹW), which spans the interval 1.0–0.5 Ma and has an SST record at a resolution of 1 sample per 0.7 ka (Wright and Flower, Reference Wright and Flower2002).

Both sites have been used to generate summer and winter SST values using planktonic foraminifera data. Kandiano and Bauch (Reference Kandiano and Bauch2003) used three different techniques, the modern analogue technique (MAT), the transfer function technique (TFT), and the revised analogue method. SST reconstructions by these three approaches were in good agreement with each other, but Kandiano and Bauch (Reference Kandiano and Bauch2003) focussed on the MAT-derived estimates as this approach yielded better calibration results. Wright and Flower (Reference Wright and Flower2002) used both the TFT and MAT approaches, and although there was a general consistency for the climatic structure and magnitude of warmth experienced during MIS 13 and 15 generated by these two techniques, this is less true for older parts of the record. For example, the interglacial SST peaks of MIS 19 and 21 are significantly warmer when MAT is applied to the foraminifera data in comparison with the estimates generated by TFT. Both the communality values of the TFT and the dissimilarity scores of the MAT do not suggest that either technique generates temperatures from nonanalogue communities in these intervals. However, Wright and Flower (Reference Wright and Flower2002) argued that the high temperatures experienced were unlikely to be artefacts of the technique as both MIS 19 and MIS 21 had the subpolar Neogloboquadrina pachyderma sinistral near zero for the longest interval at any point in the Site 980 record (1.0–0.5 Ma).

METHODOLOGY

This study uses the planktonic foraminifera data from Site 980 and M23414 to recalculate mean annual SST using the same technique (MAT applied using the multiproxy approach for the reconstruction of the glacial ocean surface (MARGO) data set; Kucera et al., Reference Kucera, Weinelt, Kiefer, Pflaumann, Hayes, Weinelt and Chen2005) in order to produce an SST record of the last 1 Ma. Although the foraminifera data on which these reconstructions are based have been previously published, the SST values presented here are entirely new and slightly different from the previous publications (Figure 1). The chronologies applied to these SST records, as generated by the original authors, are based on (1) tuning the benthic δ18O of the record in question to a previously orbitally resolved benthic record, as is the case for Site 980 (Wright and Flower, Reference Wright and Flower2002), or (2) using sediment reflectance properties of the record in question to tune to a neighbouring record that has been orbitally tuned, as is the case for M23414 (Kandiano and Bauch, Reference Kandiano and Bauch2003). The chronologies presented here are those generated by retuning to the LR04 data set (Lisiecki and Raymo, Reference Lisiecki and Raymo2005). The M23414 record spans 0–505 ka, while Site 980 spans 513–998 ka; consequently, a ca. 8 ka gap exists in the SST record provided by these two records, situated in the middle of MIS 13. In this study, this gap is filled by including planktonic foraminifera-based SST data from Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP) Site U1314 (Alonso-Garcia et al., Reference Alonso-Garcia, Sierro, Kucera, Flores, Cacho and Andersen2011b).

Although the two records are separated by ~320km (Fig. 2), the SST records are combined as a single composite SST record (Fig. 3). This approach is considered valid for two reasons. First, at the present day the summer and winter SST values are identical (Fig. 4) at both core sites from surface to a depth of 300 m (the zone within which planktonic foraminifera exist). Second, although no continuous SST record exists for the interval 0–500 ka in Site 980, we applied the same technique (MAT and the MARGO data set) to the foraminifera data of MIS 5 (Oppo et al., Reference Oppo, McManus and Cullen2006) and compared this SST reconstruction to M23414 (Fig. 4), and these show that the thermal regime at Site 980 during the last interglacial period was identical to that which occurred at M23414. Consequently, although the sites are spatially distinct, there is good reason to believe that they experienced similar temperature histories.

Figure 2 Map showing the locations of the key marine records and, inset, British terrestrial sites discussed in the text (Br, Brooksby; Bx, Boxgrove; F, Feltwell; HL, High Lodge; Hp, Happisburgh; Is, Isleworth; Pk, Pakefield; WR, West Runton; W-S-M, Westbury-sub-Mendip; WW, Waverley Wood).

Figure 3 (color online) A comparison of the M23414/ Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Site 980 mean annual sea surface temperature (SST) record (a) calculated in this study using the original foraminifera data and the modern analogue technique (MARGO data set), with the sea level record of Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP) Site 1123 (Elderfield et al., Reference Elderfield, Ferretti, Greaves, Crowhurst, McCave, Hodell and Piotrowski2012) and the sea level stack SL16 (b; Spratt and Lisiecki, Reference Spratt and Lisiecki2016), LR04 benthic stack (c; Lisiecki and Raymo, Reference Lisiecki and Raymo2005), and the EPICA (European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica) Dome Concordia (EDC) temperature anomaly record (d; Jouzel et al., Reference Jouzel, Masson-Delmotte, Cattani, Dreyfus, Falourd, Hoffmann and Minster2007).

Figure 4 Comparison of modern (a) and Pleistocene (b) sea surface temperature (SST) characteristics of sites M23414 (black) and Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Site 980 (grey). Both the modern winter and summer temperature values and the reconstructions for SST values during Marine Oxygen Isotope Stage (MIS) 5e show that the sites have similar climatic contexts and are, therefore, suitable for the production of a combined SST record. Modern temperature data from WOA13, MIS 5e data recalculated for this study from Kandiano and Bauch (Reference Kandiano and Bauch2003) and Oppo et al. (Reference Oppo, McManus and Cullen2006).

SST characteristics of M23414/ODP 980 over the past 1 Ma

The late middle and late Pleistocene (last ~450 ka)

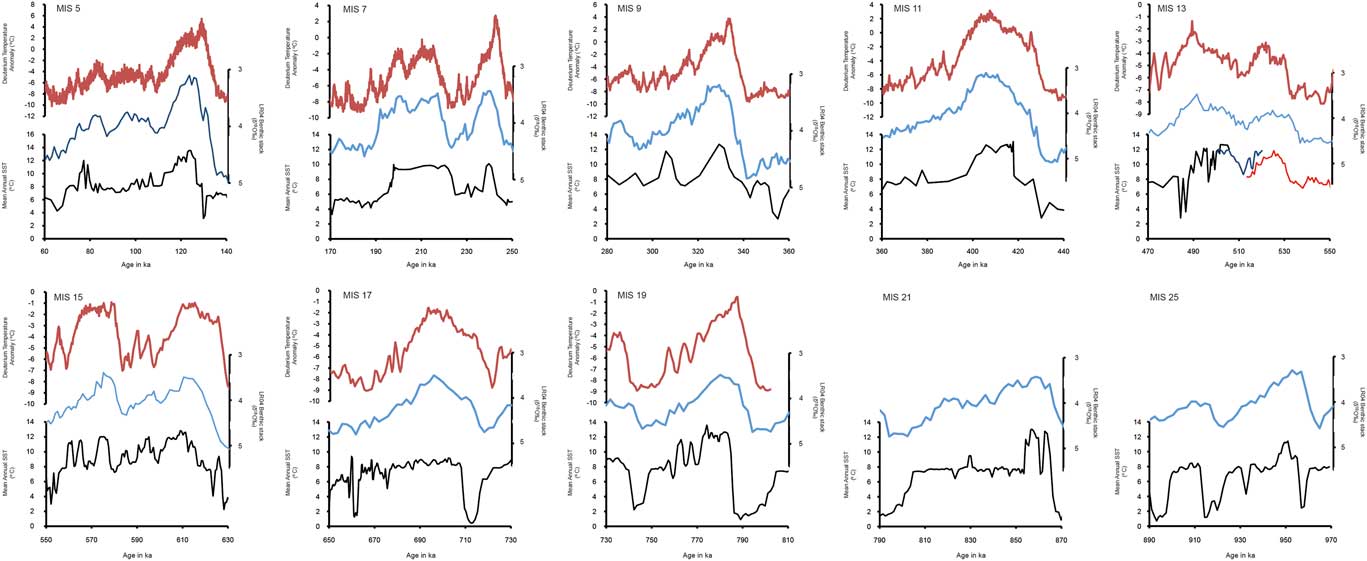

Figure 3 compares the combined M23414/ODP Site 980 record with both LR04 (0–1000 ka) and the EDC temperature anomaly record (0–800 ka) EPICA Community Members, 2004; Lisiecki and Raymo, Reference Lisiecki and Raymo2005; Jouzel et al., Reference Jouzel, Masson-Delmotte, Cattani, Dreyfus, Falourd, Hoffmann and Minster2007). Detailed interglacial comparisons between the SST record presented here and LR04 and, for MIS 5 to 19, EDC are shown in Figure 5. These comparisons show that a strong consistency exists between the climatic stratigraphy (i.e., the timing and number of warm/cold interludes) of these records. However, the absolute magnitude of glacial/interglacial cycles seen in the North Atlantic is not routinely consistent with that observable in LR04 and EDC. For example, all warm stages of the past 450 ka are characterised by clear climatic oscillations at the isotopic substage level with the exception of MIS 11. Both MIS 5 and MIS 9 contain a strong interglacial SST peak early in the warm stage and at least one significant, but cooler, interstadial peak that occurs later, both of which are separated by cooling events. This pattern can be seen in both LR04 and EDC; however, in both cases the magnitude of the interstadial peak is stronger in the northeast Atlantic than in either of these two records. In M23414, for example, MIS 5a is characterised by warmth that is as strong as that experienced in some middle Pleistocene interglacial periods, but in both EDC and LR04, this interstadial event is significantly cooler or characterised by significantly higher δ18O values than any fully interglacial episode. The absence of a strong interstadial event in late MIS 11 is also common to both LR04 and EDC, although a brief SST oscillation occurs in M23414 at ca. 375 ka. The low resolution of M23414 during late MIS 11 prevents a detailed record of climate change for this period, but other high-resolution North Atlantic records only show moderate warming events with SST much colder than during MIS 11c (e.g., Stein et al., Reference Stein, Hefter, Grützner, Voelker and Naafs2009; Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Voelker, Grimalt, Abrantes and Naughton2011). The structure of MIS 7 in M23414 is very similar to that in both LR04 and EPICA, consisting of a short early warm event (7e) and a major cooling event (7d) followed by a longer period of warmer temperatures (7c and a) with evidence of only minor cooling within it (7b).

Figure 5 (color online) Detailed comparison between sea surface temperature (SST; mean annual) data from M23414 (Marine Oxygen Isoptope Stages [MIS] 5–11) and Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Site 980 (MIS 15–25) with LR04. MIS 13 shows a composite SST record from M23414, U1314, and ODP 980. A comparison with the EDC temperature anomaly record is also made for MIS 5–19 where such data are available.

The late early Pleistocene and EMP (~1 Ma–450 ka)

The climatic stratigraphy of MIS 13 and 15 in Site 980 is again consistent with that seen in LR04 and EDC. MIS 13 is considered a lukewarm interglacial stage in which ice sheets were relatively large for an interglacial period and SST was generally lower than during other interglacial periods of the last 1 Ma (Lang and Wolff, 2011, PAGES, 2016). MIS 13 warmest intervals in the M23414/ODP Site 980 record show only slightly lower SST than during other interglacial periods, indicating that even though the ice sheets were larger, SST was rather high in the northeast Atlantic. This period is characterised by two long warm intervals (of ca. 20 ka) separated by a cold interval. Although there is a gap within the MIS 13 record, the temperature maximum occurs in late MIS 13, during the second interstadial event, a feature apparently unique to this interval but common to the record of MIS 13 in many long climatic archives (Lang and Wolff, Reference Lang and Wolff2011; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015). The SST record of MIS 15 is clearly complex, comprising multiple warm peaks with SST similar to the interglacial periods of the last ~450 ka, separated by cold episodes. This pattern is generally consistent with the structure of MIS 15 in LR04 and EDC, which both show two major warm events, although some of the warming events in Site 980 show stronger intensity than in LR04 and EDC (Lisiecki and Raymo, Reference Lisiecki and Raymo2005; Jouzel et al., Reference Jouzel, Masson-Delmotte, Cattani, Dreyfus, Falourd, Hoffmann and Minster2007). The glacial stage MIS 14 in Site 980 is relatively short compared with all other glacial stages in the record, and characterised by a relatively minor decline in temperatures (Lang and Wolff, Reference Lang and Wolff2011). Relatively mild temperatures were also recorded in MIS 8 but during a longer interval. Consequently, although the interval MIS 15/14/13 contains numerous climatic events, it represents a prolonged period in which SST oscillated between “mild” and “warm” conditions, which is relatively unique in the entirety of the last 1 Ma of SST in the North Atlantic. The SST record of MIS 19 shows a strong interglacial peak early in the warm stage, while MIS 17 appears anomalously cool, colder than any other interglacial period in the entire record and colder than many of the warm-stage interstadial events (i.e., MIS 5a) of the past 500 ka. MIS 21 and 23 lie beyond the range of EPICA but again show good consistency with their expression in LR04, within which both MIS show that the interglacial peak occurs early in the warm stage. The second half of MIS 21 is cooler but relatively stable in Site 980, mirroring the structure of this warm stage in LR04.

Long-term trends in North Atlantic SST

The M23414/ODP Site 980 record shown in Figure 3 allows observations to be made about long-term climatic trends in the northeast Atlantic. Although the record does not include the start of the EMPT (ca. 1.2 Ma), it does show that by 1 Ma the coldest phases of glacial cycles were as extreme, and in some cases as long, as those that occurred in the late middle Pleistocene and onwards. A similar observation can be made in the Iberian margin SST record of the last 1 Ma (Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Alonso-Garica, Hodell, Rufino, Naughton, Grimalt, Voleker and Abrantes2017). The lowest SST values recorded in MIS 18, 20, and 22 are as low as those that occurred in MIS 2 and 12. The low temperatures of MIS 20 appear to have persisted for ca. 20 ka. During this time interval, the thermal maxima of interglacial periods such as MIS 19 and 21 were as warm as those of the Holocene. Consequently, during at least the last 1 Ma, the pattern of extreme glacial/interglacial SST in the northeast Atlantic presented the same magnitude as for the late middle and late Pleistocene. The record is also informative with regard to the MBE. On the basis of previously published marine and terrestrial records, Candy and McClymont (Reference Candy and McClymont2013) have suggested that this event is absent in Britain and the North Atlantic. The composite M23414/ODP Site 980 record is relevant to this debate as it supports the suggestion that the MBE is poorly expressed in the North Atlantic, albeit with the caveat that the point at which the two records are joined is the approximate position of the MBE. However, other North Atlantic records like IODP Sites U1314 and U1313 and the composite record of the Iberian margin do not show a clear MBE as well (Alonso-Garcia et al, Reference Alonso-Garcia, Sierro and Flores2011a; Naafs et al., Reference Naafs, Hefter, Ferretti, Stein and Haug2011; Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Alonso-Garica, Hodell, Rufino, Naughton, Grimalt, Voleker and Abrantes2017).

The pattern of interglacial SST shown in Figure 3 also highlights that the period 0.78–0.45 Ma was, in this region, a period of complex climatic change. That there was little change in the extremity of interglacial/glacial cycles across the MBE is supported by the fact that (1) the thermal maxima of MIS 13, 15, and 19 were as warm as most post-MBE interglacial periods and (2) the temperature minima of MIS 16, 18, and 20 were as cool (and as prolonged) as many of the post-MBE cold stages. However, it is also true to say that this record shows a number of subdued climatic cycles, with MIS 17 being a particularly cool interglacial period and MIS 14 being a cold stage characterised by a particularly short and moderate glacial maxima. High-intensity interglacial periods clearly occur in the northeast Atlantic prior to the MBE; however, some aspects of the EMP interval appear to be relatively unique. In particular, the period MIS 15/14/13 (ca. 0.62 to 0.49 Ma) appears to be relatively distinct in that it is characterised by prolonged “warmth,” effectively representing, in this region, the longest period of persistent warm or mild SST of the past 1 Ma. This interval is also characterised by relatively subdued sea level changes, with moderate high stands during interglacial peaks and a small sea level decrease during MIS 14.

In summary, although many aspects of the M23414/ODP Site 980 SST record are consistent with that of other long climate records (i.e., the structure of many late middle and late Pleistocene warm phases, the prolonged warmth of the interval MIS 15–13), there are many features of this record that are very different (i.e., the strength of climate/cycles in the late early Pleistocene, the magnitude of interglacial warmth in the EMP, and the strength of interstadial events in many warm stages of the past 0.45 Ma). This comparison highlights the fact that a locally specific record, rather than a “global” record, is important for understanding the precise climatic history of a region.

LONG-TERM CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE NORTHEAST ATLANTIC AND THE PALAEOLITHIC RECORD OF THE BRITISH ISLES

Glacial/interglacial cycles

It is widely accepted that abandonment during glacial periods and reoccupation during interglacial periods/warm stages characterises the British Palaeolithic of the past 400 ka (Ashton and Lewis, Reference Ashton and Lewis2002; Ashton et al., Reference Ashton, Lewis and Stringer2011; Pettitt and White, Reference Pettitt and White2012). The SST record presented in this study shows that from MIS 12 onwards, high-magnitude climate cycles were well established with the magnitude of mean annual temperature shifts from full glacial to full interglacial being on the order of ~13°C. Consequently, the M23414/ODP Site 980 record provides evidence for high-magnitude climate cycles during this interval, which would support this pattern of human migration. Significantly, the SST record also shows that during the transition from the early to middle Pleistocene, glacial/interglacial cycles of a magnitude and duration that were consistent with those of the late middle and late Pleistocene were already established by 1 Ma. This implies that the earliest known occupation event in northern Europe, the site of Happisburgh III, would have occurred against the backdrop of extreme glacial/interglacial cycles, not the more moderate 40 ka cycles that are apparent in many benthic δ18O records (see Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Ashton, Lewis, Abel, Coope, Field and Gale2010). What adaptations would have been necessary for the successful migration into, and occupation of, northern Europe is a key research question. The SST record presented here shows that there is nothing different about the nature of glacial/interglacial forcing at this time that would make the challenges of occupying this region any different from that which later human populations would have experienced.

Climate variability at the isotopic substage level

A key characteristic of both the Palaeolithic and palaeoenvironmental record of the British late middle Pleistocene is the evidence for “complexity” that exists within deposits of a single warm isotopic stage (White and Schreve, Reference White and Schreve2000; Candy and Schreve, Reference Candy and Schreve2007; Ashton et al., Reference Ashton, Lewis, Parfitt, Penkman and Coope2008). MIS 11 and 9, for example, both contain evidence for three distinct types of lithic industries (see White and Schreve, Reference White and Schreve2000); an early core and flake industry (the “Clactonian”) and a later Mode II industry occur in both of these warm stages. The later deposits of MIS 11 contain evidence for technological innovations (the presence of twisted ovate hand axes), while the later MIS 9 deposits contain the first evidence of Levallois technology in northern Europe. It has been suggested that the presence of this archaeological diversity and its potential implications for the migration into Britain of different populations of early humans is a function of climate forcing during a single MIS at substage level. MIS 7 sequences also contain abundant evidence for large climatic shifts with multiple temperate phases separated by evidence for significant climatic deteriorations (Candy and Schreve, Reference Candy and Schreve2007; Schreve, Reference Schreve2001b).

In the M23414/ODP Site 980 record, one of the clearest features of warm stages of the past 0.45 Ma is the evidence for strong forcing at the isotopic substage level. After the main interglacial “peak,” most stages contain evidence for a cooling event followed by a post-interglacial warm event. The magnitude of the cooling event is approximately half that experienced during a full interglacial/glacial shift, whereas the magnitude of the warm event is close to that of fully interglacial conditions. This latter observation is particularly significant as, in the British terrestrial record, climatic reconstructions for warm stage interstadial events, such as MIS 5a at Isleworth, indicate summer temperatures comparable to, or even higher than, modern-day conditions (Coope et al., Reference Coope, Gibbard, Hall, Preece, Robinson and Sutcliffe1997). The climatic framework for warm MIS of the past 0.45 Ma in the northeast Atlantic is one of strong substage forcing, which would explain the palaeoenvironmental complexity seen in stages such as MIS 5 and 7, while also providing a potential driver for the archaeological diversity seen in MIS 9 and 11. It is only in MIS 11 that the warming in a postinterglacial interstadial event appears relatively subdued; this is consistent with the apparent absence of such an event in LR04 and the short duration of late–MIS 11 interstadial events in EDC and multiple North Atlantic records (Lisiecki and Raymo, Reference Lisiecki and Raymo2005; Jouzel et al., Reference Jouzel, Masson-Delmotte, Cattani, Dreyfus, Falourd, Hoffmann and Minster2007). Candy et al. (Reference Candy, Schreve, Sherriff and Tye2014) have argued that the variability of the expression of such events in different records is a combination of differences in the resolution of such records and the relatively short duration of these interstadial events. The subdued nature of the warming seen in late MIS 11 within M23414 could be a function of this as the sample resolution is ca. 1.6 ka, because the data presented in Oppo et al. (Reference Oppo, McManus and Cullen1998) from Site 980 indicate several cooling-warming events during late MIS 11. Moreover, a number of authors have argued for clear but short-lived warming events in the British Isles during late MIS 11 (Schreve, Reference Schreve2001b; Coope and Kenward, Reference Coope and Kenward2007; Ashton et al., Reference Ashton, Lewis, Parfitt, Penkman and Coope2008; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve, Sherriff and Tye2014).

Minimal cooling during MIS 15–13

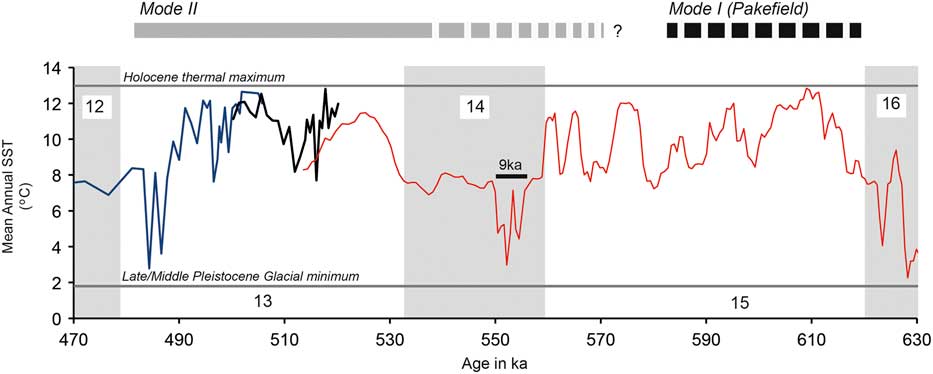

With respect to early human occupation, the period MIS 15–13 is one of the most significant intervals as it is associated with (1) a proliferation in the number of archaeological sites found in northwest Europe and (2) the widespread adoption of Mode II technologies (Hosfield, Reference Hosfield2011; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015; and see Schreve et al., Reference Schreve, Moncel and Bridgland2015 and references therein). This is true not only for the British Isles, but also for much of western and central Europe north of the Alps (see Schreve et al., Reference Schreve, Moncel and Bridgland2015). It is also an important interval in the SST history of the northeast Atlantic as it is a period of uniquely prolonged warmth (Fig. 6) with moderate sea level changes. The MIS 14 cold stage is the warmest of any glacial period of the last 1 Ma, while the climatic minimum lasts for less than 9 ka. North Atlantic records suggest the Arctic (or subpolar) front was farther north than during MIS 16 or 12 (Alonso-Garcia et al., Reference Alonso-Garcia, Sierro and Flores2011a). Furthermore, there is no evidence for Heinrich(-like) events in the North Atlantic during MIS 14, indicating small continental ice sheets around the Atlantic (Hodell et al., Reference Hodell, Channell, Curtis, Romero and Röhl2008; Naafs et al., Reference Naafs, Hefter, Ferretti, Stein and Haug2011, Reference Naafs, Hefter and Stein2013). Hao et al. (Reference Hao, Wang, Oldfield and Guo2015) suggest that MIS 14 was such a minor cold stage that it can be argued that, in the Northern Hemisphere at least, interglacial conditions persisted for in excess of 100 ka. Whether this means that conditions were fully interglacial or more interstadial-like is unclear, but it appears to be a period that contained minimum evidence for glacial conditions. Hao et al. (Reference Hao, Wang, Oldfield and Guo2015) have argued that these persistent warm conditions promoted favourable conditions for a second wave of hominins from Africa into Eurasia. It is, therefore, important to stress both the uniqueness of the climate of this time interval and its significance to early human occupation in northwest Europe. The slightly lower sea level (Elderfield et al., Reference Elderfield, Ferretti, Greaves, Crowhurst, McCave, Hodell and Piotrowski2012; Spratt and Lisiecki, Reference Spratt and Lisiecki2016) compared with other interglacial periods is also a factor that may have facilitated the occupation of the British Isles. Although sea level records (Fig. 3) also indicate that this was an interval when eustatic levels were relatively low, with respect to other interglacial conditions, this does not necessarily mean that Britain was more accessible to early colonisers. The land bridge (in the region of the Strait of Dover) that allowed a permanent connection between Britain and the continent persisted until MIS 12, when it was destroyed by a major glacial outburst flood (Toucanne et al., Reference Toucanne, Zaragosi, Bourillet, Gibbard, Eynaud, Giraudeau and Turon2009). No geographic boundary to early human colonisation of Britain would, therefore, have existed during the period MIS 15–13 regardless of eustatic sea level.

Figure 6 (color online) Sea surface temperature (SST) record of Marine Oxygen Isoptope Stages 15 to 13 in the M23414/U1314/ Ocean Drilling Program Site 980 record and its relationship to the earliest Palaeolithic sites (for discussion, see Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015 and text).

Only two known archaeological sites, Pakefield and Happisburgh III, are known from northwest Europe prior to the MIS 15–13 interval (and Westaway [Reference Westaway2011] has argued that both of these sites could be encompassed within the climatostratigraphy of MIS 15). The sites of Boxgrove, Waverley Wood, Brooksby, Happisburgh I, Feltwell, Westbury-sub-Mendip, and High Lodge, among others, can, however, all be confidently placed in the MIS 15–13 interval (Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015). Consequently, although evidence for human occupation of this region does occur prior to MIS 15, it is during the period of prolonged warmth, MIS 15–13, that evidence for human occupation proliferates. The observation that the first period during which abundant evidence for human occupation in northwest Europe occurs is a period of prolonged climatic warmth is, therefore, an important one. The M23414/ODP Site 980 SST record indicates that the interglacial peaks of this interval were as strong as those that occurred from MIS 11 onwards; however, much of this period may have been more interstadial in character than fully interglacial. Candy et al. (Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015) have shown that very few of the occupation events in this interval occurred during peak interglacial conditions with the palaeocology of many of these sites being late-interglacial or interstadial in character. This would fit in with the SST evidence for the climate of this interval, which is indicative of a period of prolonged “warm” but not always fully interglacial conditions.

Climatostratigraphy of the EMP and its significance for the age of the earliest occupation events

For the last 0.45 Ma in Britain, it is routinely possible to correlate interglacial/interstadial deposits with specific MIS; for the period 0.45–0.8 Ma, however, this is more difficult (Candy et al., Reference Candy, Rose, Coope, Lee, Parfitt, Preece and Schreve2010; Preece and Parfitt, Reference Preece and Parfitt2012). This interval lacks the robust river terrace/raised shoreline stratigraphies that have been so important in subdividing the British late middle and late Pleistocene, while few radiometric dating techniques exist that can be applied to this period. Biostratigraphy and AAR have allowed the identification of biostratigraphic assemblages for the EMP, some of which can be relatively securely placed into MIS 13 and/or late MIS 15 (Penkman et al., Reference Penkman, Preece, Bridgland, Keen, Meijer, Parfitt, White and Collins2011; Preece and Parfitt, Reference Preece and Parfitt2012; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015). However, a number of older biostratigraphic groups exist. On the basis of biostratigraphy, these must be older than MIS 13; however, in light of the fact that none of the deposits that these fossil assemblages occur within have reversed magnetisation, they must be younger than 0.78Ma.

Two observations are crucial here: first, that Preece and Parfitt (Reference Preece and Parfitt2012) suggest the existence of five discrete biotsratigraphic assemblages that correlate to fully temperate episodes within the period 0.45–0.78 Ma, and second, that there is a suggestion, which appears robust, that MIS 19 is not represented in the British sequence because the early/middle part of this interglacial period should be magnetically reversed and this has yet to be observed within any British temperate-stage deposit (Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015). The five different biostratigraphic groups identified by Preece and Parfitt (Reference Preece and Parfitt2012) must, therefore, be resolved within three warm MIS. This situation is further complicated by the fact that two interglacial sequences, Pakefield and West Runton, that must, on the basis of biostratigraphy and prevailing palaeoclimate, be distinct temperate episodes (Stuart and Lister, Reference Stuart and Lister2001; Preece and Parfitt, Reference Preece and Parfitt2012) have very similar AAR values, implying that they accumulated during the same MIS (Penkman et al., Reference Penkman, Preece, Bridgland, Keen, Meijer, Parfitt, White and Collins2011).

The M23414/ODP Site 980 record is an important first step in the resolution of these inconsistencies, as it highlights the climatic complexity of warm stages of the EMP, such as MIS 15. This warm stage contains at least three temperate substages that appear, in terms of temperature regime, to be fully interglacial. Furthermore, these substages are each separated by some 20 ka and are, therefore, sufficiently chronologically distinct from one another to allow for biostratigraphic differences to exist between the flora and fauna of each substage. The climatic structure of MIS 15 is, therefore, compatible with the existence of two biostratigraphically and climatically distinct interglacial periods that are indistinguishable on the basis of AAR values.

Previously, it had been proposed that Pakefield and West Runton occurred in distinct MIS with Pakefield correlating to either MIS 19 or 17 (Stuart and Lister, Reference Stuart and Lister2001; Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Barendregt, Breda, Candy, Collins, Coope and Durbidge2005; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015). The suggestion that the deposits at Pakefield correlate to MIS 19 has always been debated as the Brunhes/Matuyama boundary occurs in the middle of this interglacial period, and yet despite the deposits at Pakefield recording a major part of a temperate stage, all of the sediment units exhibit normal magnetic properties. The correlation of the Pakefield sequence with MIS 17 is questioned here on the basis of the SST record of this interglacial period seen in Site 980. The palaeoecological assemblage from Pakefield has been used to reconstruct one of the warmest interglacial climates known to have occurred in the British Isles with summer temperatures at least 3–4°C warmer than the present day (Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Barendregt, Breda, Candy, Collins, Coope and Durbidge2005; Candy et al., Reference Candy, Rose and Lee2006, Reference Candy, Rose, Coope, Lee, Parfitt, Preece and Schreve2010; Coope, Reference Coope2006, Reference Coope2010); however, in Site 980 the SST values of MIS 17 are the coldest of any interglacial period of the past 1 Ma. It is, therefore, considered unlikely that the enhanced warmth recorded at Pakefield is compatible with the cool SST regime in the immediate northeast Atlantic. In this context, the proposed correlation of Pakefield with MIS 15, which contains intervals of high SST values in Site 980, seems reasonable.

If it is accepted that the climatic complexity of MIS 15, recorded in Site 980, can account for biostratigraphically distinct sequences, such as West Runton and Pakefield, to have accumulated during a single MIS, this has major implications for the earliest human occupation of northwest Europe. On the basis of the presence of archaic small mammal species present in the Pakefield sequence (Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Barendregt, Breda, Candy, Collins, Coope and Durbidge2005), this site is the second oldest, after Happisburgh III, of all of the Palaeolithic sites in northwest Europe (Parfitt et al., Reference Parfitt, Ashton, Lewis, Abel, Coope, Field and Gale2010). This implies that, with the exception of Happisburgh III, all of the early (pre–MIS 12 or pre-Anglian) archaeological sites in Britain must correlate with the prolonged warm interval represented by MIS 15–13 (Candy et al., Reference Candy, Schreve and White2015). This unique climatic period, therefore, becomes of increasing importance to our understanding of early human occupation in this region as it would appear that the first major proliferation of archaeological evidence occurred during a 100 ka period dominated by interglacial and interstadial conditions.

Conclusions

SST data from M23414/ODP Site 980 have been used to investigate the evolution of climates in the region of the British Isles for the past 1 Ma, with the particular aim of understanding the climatic background to early human occupation in northwest Europe. The correlation between this SST record and the British Palaeolithic record allows the following conclusions to be drawn. First, that by the time of the earliest known occupation of Britain, the extreme 100 ka glacial/interglacial cycles that characterise the late middle and late Pleistocene had already become established. The magnitude and frequency of the climate cycles that this earliest colonisation occurred in the context of would, therefore, have been no different from glacial/interglacial cycles of the late Pleistocene. Second, that the archaeological complexity that is observable in many warm isotopic stages is mirrored by climatic complexity. During the late middle and late Pleistocene, the occurrence of large-scale stadial/interstadial climatic oscillations after the main interglacial peak of many warm stages, meaning that archaeological complexity occurs, is routinely found against a backdrop of strong climate forcing. Finally, the time interval during which the first major proliferation of early archaeological evidence occurs in Britain, MIS 15–13, is found in association with a period of prolonged warmth, which is unique in the climate history of the past 1 Ma in this region. Most of this time interval is characterised by interglacial to interstadial conditions with the glacial interval of MIS 14 being short lived and subdued, and it is under these conditions that the first widespread colonisation of Britain and northern Europe appears to have occurred.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

IC wishes to acknowledge the Leverhulme funded “Ancient Human Occupation of Britain” project, during which many of these ideas were formulated. MA-G is supported by the Portuguese National Science and Technology Foundation (PTDC/MAR-PRO/3396/2014, UID/Multi/04326/2013, and SFRH/BPD/96960/2013). The authors would like to thank Dr. David Naafs and an anonymous reviewer for providing detailed and constructive comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.