Introduction

Membrane proteins (MPs) fulfill essential biological functions in the cell and are important biomedical targets. Obtaining MP high-resolution structures can contribute tremendously to the development of novel therapies. However, structural studies of MPs are notoriously more challenging than those of soluble proteins. Many difficulties affect all steps of sample preparation from protein expression to structural determination. Extraction from the native lipid environment with and stabilization against surfactants are particularly critical steps, whose optimization is time-consuming. Over the years, many strategies and tools have been developed to overcome each type of difficulty.

The first MPs for which atomic models could be built were proteins that are naturally abundant (Deisenhofer et al., Reference Deisenhofer, Epp, Miki, Huber and Michel1985; Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Baldwin, Ceska, Zemlin, Beckmann and Downing1990; Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Wacker, Weckesser, Weite and Schulz1990). However, the low natural abundance of most MPs necessitated the development of recombinant expression strategies in either microbial host cells, such as Escherichia coli or Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Hays et al., Reference Hays, Roe-Zurz and Stroud2010; Zoonens and Miroux, Reference Zoonens and Miroux2010; Dilworth et al., Reference Dilworth, Piel, Bettaney, Ma, Luo, Sharples, Poyner, Gross, Moncoq, Henderson, Miroux and Bill2018), or other expression systems better suited to the production of mammalian MPs, such as baculovirus-infected insect cells or human embryo kidney cells (Bill et al., Reference Bill, Henderson, Iwata, Kunji, Michel, Neutze, Newstead, Poolman, Tate and Vogel2011; Andréll and Tate, Reference Andréll and Tate2013; Contreras-Gómez et al., Reference Contreras-Gómez, Sánchez-Mirón, García-Camacho, Molina-Grima and Chisti2014). These host cells have proven very efficient for producing MPs in amounts amenable to structural investigations.

Once they are expressed in suitable quantities, MPs need to be extracted from the membrane and purified in their native state. Unfortunately, their stability in aqueous solutions is often problematic. Perturbation of the protein structure by inadequate surfactants can generate misleading data (Cross et al., Reference Cross, Sharma, Yi and Zhou2011; Chipot et al., Reference Chipot, Dehez, Schnell, Zitzmann, Pebay-Peyroula, Catoire, Miroux, Kunji, Veglia, Cross and Schanda2018), which is a major concern in this field. Detergents are historically the first surfactants used for MP solubilization and purification. Detergents disrupt the membrane and adsorb onto the hydrophobic transmembrane surface of MPs, keeping them water-soluble (see e.g. Garavito and Ferguson-Miller, Reference Garavito and Ferguson-Miller2001; Otzen, Reference Otzen2015; Sadaf et al., Reference Sadaf, Cho, Byrne and Chae2015; Orwick-Rydmark et al., Reference Orwick-Rydmark, Arnold and Linke2016; Popot, Reference Popot2018). However, detergents tend to interfere with molecular interactions in MP transmembrane domains, leading to inactivation (for a recent discussion of causes and remedies, see Chapter 2 in Popot, Reference Popot2018). The extent of this problem varies both from one detergent and from one MP to another. Quite naturally, the first high-resolution structures of MPs ever obtained were those of abundant and detergent-resistant bacterial MPs. Access to the structures of generally more fragile and less abundant eukaryotic MPs has been made possible by progress in production methods, technical advances in structural approaches, and the development and increasingly frequent usage of novel, less destabilizing surfactants. Detergents and other emerging tools used to prepare MP samples for structural determination by single-particle electron cryo-microscopy (SP cryo-EM) have been described in Mio and Sato (Reference Mio and Sato2018) and Autzen et al. (Reference Autzen, Julius and Cheng2019).

In the present review, we have carried out a quantitative analysis, for all cryo-EM structures of MPs deposited as of January 1, 2021, of the use of detergents, amphipathic polymers such as amphipols (APols) and styrene-maleic acid (SMA) copolymers, protein-based nanodiscs (NDs), and other emerging compounds. The analysis is based on the list of MP structures available on Stephen White's database (https://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/mpstruc/), which is designed to be as inclusive as possible. This list contains all unique MP structures, coordinate files, and almost all published reports of MP structures accumulated in the protein data bank (PDB) since 1985. The goal of the present analysis is to give an overview of the evolution of approaches in this rapidly moving field and, more specifically, of current trends in the implementation of conventional and novel surfactants. Recently, a similar analysis has been performed (Choy et al., Reference Choy, Cater, Mancia and Pryor2021), which includes structures obtained by X-ray crystallography and NMR but bears on a more restricted corpus of cryo-EM data (see below).

The cryo-EM resolution revolution and its impact on MP structural biology

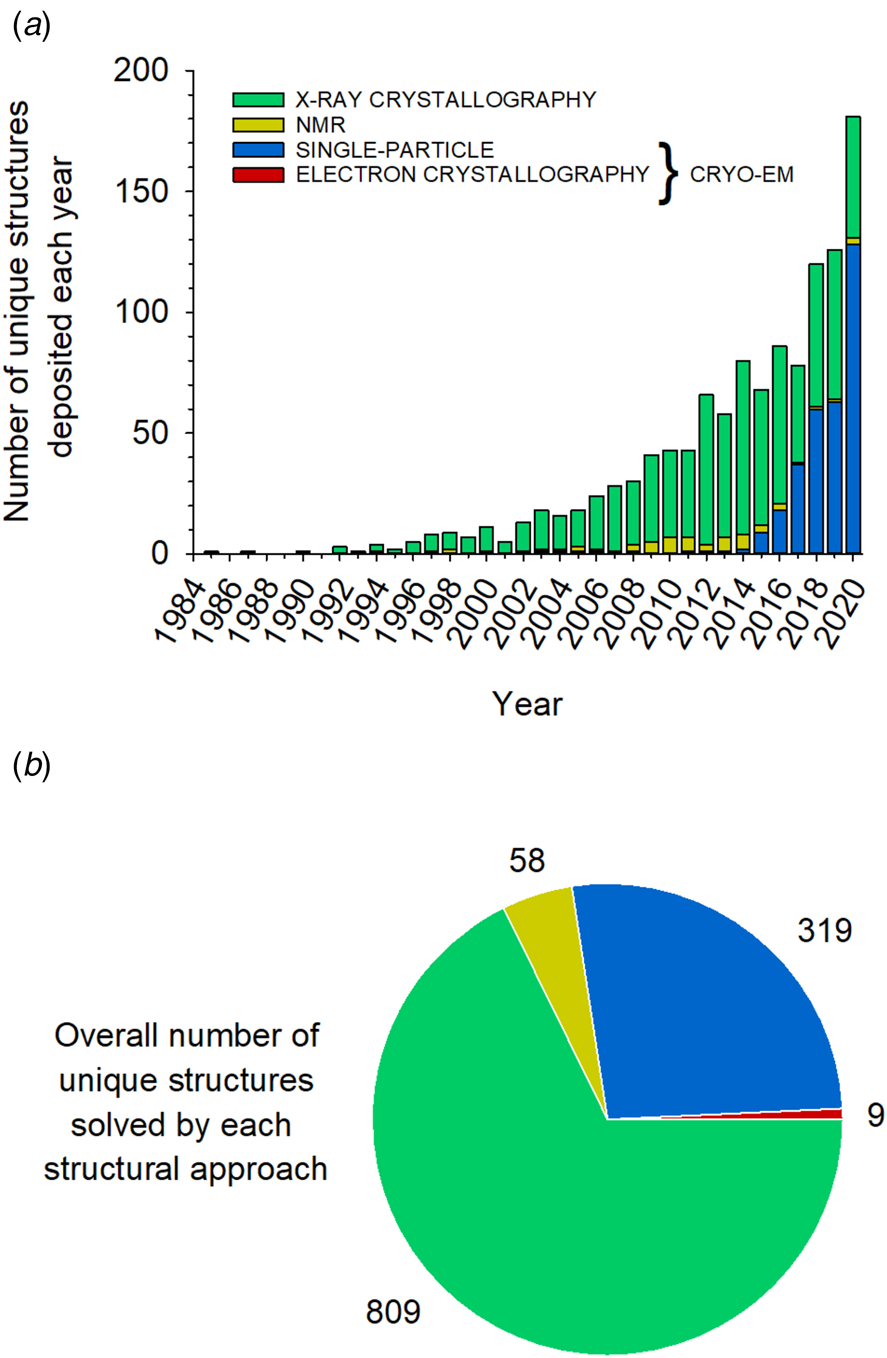

Approaches giving access to the three-dimensional (3D) structure of biological macromolecules include X-ray crystallography, solution and solid-state NMR spectroscopy, electron crystallography and SP cryo-EM. The distribution of the unique MP structures published during each of the past 35 years, sorted out according to the structural approach used, is shown in Fig. 1a. Over three decades, X-ray crystallography was the dominant technique in MP structural biology. As a result, more than two-thirds of the total number of currently available unique MP structures have been solved using this approach (Fig. 1b). X-ray crystallography can reveal atomic details of MP structure at a very high resolution. Its major bottleneck remains the production of well-ordered 3D crystals. This is particularly challenging for MPs due to the presence of detergent, instability, and/or intrinsic conformational heterogeneity (Tate, Reference Tate and Mus-Veteau2010). Significant progress has been achieved by resorting to strategies such as the binding of antibody fragments or nanobodies, MP stabilization through engineered mutations, the use of lipidic cubic phases, and/or novel techniques for collecting diffraction data, such as the use of micrometric synchrotron X-ray beams and X-ray free-electron lasers (for reviews, see e.g. Martin-Garcia et al., Reference Martin-Garcia, Conrad, Coe, Roy-Chowdhury and Fromme2016; Ishchenko et al., Reference Ishchenko, Abola and Cherezov2017). Over the past decade, however, the most spectacular breakthroughs have been achieved in cryo-EM (Nogales and Scheres, Reference Nogales and Scheres2015; De Zorzi et al., Reference De Zorzi, Mi, Liao and Walz2016; Vinothkumar and Henderson, Reference Vinothkumar and Henderson2016; Cheng, Reference Cheng2018; Nwanochie and Uversky, Reference Nwanochie and Uversky2019).

Fig. 1. Distribution of unique MP structures solved by each structural approach between 1985 and January 1, 2021. (a) Number of unique MP structures deposited each year using each approach. (b) Distribution of the 1195 unique structures extracted from Stephen White's database (https://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/mpstruc/) according to the approach used to solve them. The figures were prepared using the January 8, 2021, update of MP structures from this database. Some MP structures published in 2020 may therefore not be included.

Cryo-EM encompasses a variety of techniques for determining the structures of frozen-hydrated samples, which are based on the analysis of (i) images of single particles of purified biomolecules; (ii) images and diffraction patterns of crystalline arrays; and (iii) images of whole cells or cell sections (tomography). In electron cryo-tomography, although important biological insights can be gained from images of biomolecules within their native environment, the resolution is generally much lower than that achieved with the two other cryo-EM techniques, i.e. electron crystallography and SP analysis, from which structural data at near-atomic resolution can be obtained. Electron crystallography is typically applied to planar or tubular two-dimensional (2D) crystals (Abeyrathne et al., Reference Abeyrathne, Arheit, Kebbel, Castano-Diez, Goldie, Chami, Stahlberg, Renault and Kühlbrandt2012; Kühlbrandt, Reference Kühlbrandt2013). A more recent technique, referred to as microcrystal electron diffraction (MicroED), has been developed for the analysis of 3D microcrystals (Nannenga and Gonen, Reference Nannenga and Gonen2019; Nguyen and Gonen, Reference Nguyen and Gonen2020); for the moment, however, microED has not yet yielded any de novo MP structure.

Electron crystallography applied to 2D crystals has a long and prestigious history, as it was the approach that enabled building the first medium-resolution structural model ever obtained of a MP, that of the archaebacterial bacteriorhodopsin (at 7 Å resolution in the membrane plane (Henderson and Unwin, Reference Henderson and Unwin1975)), and, later, yielded the first data (at 3.5 Å in-plane) leading to an atomic model of the protein's transmembrane region (Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Baldwin, Ceska, Zemlin, Beckmann and Downing1990). Before 2013, deposited cryo-EM coordinates of MPs were all from 2D crystal electron crystallography. In 2013 were published the first near-atomic-resolution MP structures determined by SP cryo-EM (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Liao, Cheng and Julius2013; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Cao, Julius and Cheng2013). Since that date, the number of unique MP structures established by this approach has increased explosively (Fig. 1a). Decisive advances, particularly as regards data collection and correction, as well as software development for model building, have revolutionized the field (Cheng, Reference Cheng2015; Alnabati and Kihara, Reference Alnabati and Kihara2019). A combined approach of SP analysis applied to helical arrays (McCullough et al., Reference McCullough, Clippinger, Talledge, Skowyra, Saunders, Naismith, Colf, Afonine, Arthur, Sundquist, Hanson and Frost2015; Lopez-Redondo et al., Reference Lopez-Redondo, Coudray, Zhang, Alexopoulos and Stokes2018) or 2D crystals (Righetto et al., Reference Righetto, Biyani, Kowal, Chami and Stahlberg2019) has been reported. As a rule, however, SP analysis in cryo-EM refers to images of solubilized, unstained, isolated MPs embedded in a thin layer of vitreous ice, which are classified and averaged for 3D reconstruction.

Because it bypasses crystallization, which is the limiting step in X-ray and electron crystallography, SP cryo-EM has turned into a highly efficient approach to the structural analysis of MPs, to the point that three-quarters of the MP structures determined in 2020 have been obtained in this way (Fig. 1a). However, whereas both crystallography and NMR can solve the structures of small MPs, a size limit (currently ~100 kDa; see Nygaard et al., Reference Nygaard, Kim and Mancia2020) exists in SP cryo-EM because, if a MP is too small, aligning particle images becomes difficult (Henderson, Reference Henderson1995). Given that the technique is evolving rapidly, one can expect to reach in a near future a size limit close to ~40 kDa, as for soluble proteins (Zubcevic et al., Reference Zubcevic, Herzik, Chung, Liu, Lander and Lee2016). Alternatively, the size of small MPs can be artificially increased by binding either a natural (Frauenfeld et al., Reference Frauenfeld, Gumbart, van der Sluis, Funes, Gartmann, Beatrix, Mielke, Berninghausen, Becker, Schulten and Beckmann2011) or an artificial ligand (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Avila-Sakar, Kim, Booth, Greenberg, Rossi, Liao, Li, Alian, Griner, Juge, Yu, Mergel, Chaparro-Riggers, Strop, Tampé, Edwards, Stroud, Craik and Cheng2012), provided that the assembly is well-defined and rigid. This strategy has been widely employed for determining the cryo-EM structures of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in complex with either their natural G protein or arrestin ligands (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Khoshouei, Radjainia, Zhang, Glukhova, Tarrasch, Thal, Furness, Christopoulos, Coudrat, Danev, Baumeister, Miller, Christopoulos, Kobilka, Wootten, Skiniotis and Sexton2017; Draper-Joyce et al., Reference Draper-Joyce, Khoshouei, Thal, Liang, Nguyen, Furness, Venugopal, Baltos, Plitzko, Danev, Baumeister, May, Wootten, Sexton, Glukhova and Christopoulos2018; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Ma, Sutkeviciute, Shen, Zhou, de Waal, Li, Kang, Clark, Jean-Alphonse, White, Yang, Dai, Cai, Chen, Li, Jiang, Watanabe, Gardella, Melcher, Wang, Vilardaga, Xu and Zhang2019c; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Masureel, Qu, Janetzko, Inoue, Kato, Robertson, Nguyen, Glenn, Skiniotis and Kobilka2020a), an antibody fragment (Fab) and/or a nanobody (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Pöge, Morizumi, Gulati, Van Eps, Zhang, Miszta, Filipek, Mahamid, Plitzko, Baumeister, Ernst and Palczewski2019a; Tsutsumi et al., Reference Tsutsumi, Mukherjee, Waghray, Janda, Jude, Miao, Burg, Aduri, Kossiakoff, Gati and Garcia2020), or a combination of these ligands (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Hu, Ramachandran, Erickson, Cerione and Skiniotis2019; Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Thomsen, Cahill, Huang, Huang, Marcink, Clarke, Heissel, Masoudi, Ben-Hail, Samaan, Dandey, Tan, Hong, Mahoney, Triest, Little, Chen, Sunahara, Steyaert, Molina, Yu, des Georges and Lefkowitz2019; Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Marino, Adaixo, Pamula, Muehle, Maeda, Flock, Taylor, Mohammed, Matile, Dawson, Deupi, Stahlberg and Schertler2019; Yin et al., Reference Yin, Li, Jin, Yin, de Waal, Pal, Yin, Gao, He, Gao, Wang, Zhang, Zhou, Melcher, Jiang, Cong, Edward Zhou, Yu and Eric Xu2019a; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Shen, Zhao, Mao, Zhou, Shen, de Waal, Bi, Li, Jiang, Wang, Sexton, Wootten, Melcher, Zhang and Xu2020; Qiao et al., Reference Qiao, Han, Li, Li, Zhao, Dai, Chang, Tai, Tan, Chu, Ma, Thorsen, Reedtz-Runge, Yang, Wang, Sexton, Wootten, Sun, Zhao and Wu2020). More recently, another class of chimeric binders, called megabodies, consisting of a nanobody grafted onto a larger scaffold protein via two short peptide linkers, has been engineered to overcome size limitations while improving the particle orientation in ice (Uchański et al., Reference Uchański, Masiulis, Fischer, Kalichuk, López-Sánchez, Zarkadas, Weckener, Sente, Ward, Wohlkönig, Zögg, Remaut, Naismith, Nury, Vranken, Aricescu, Pardon and Steyaert2021).

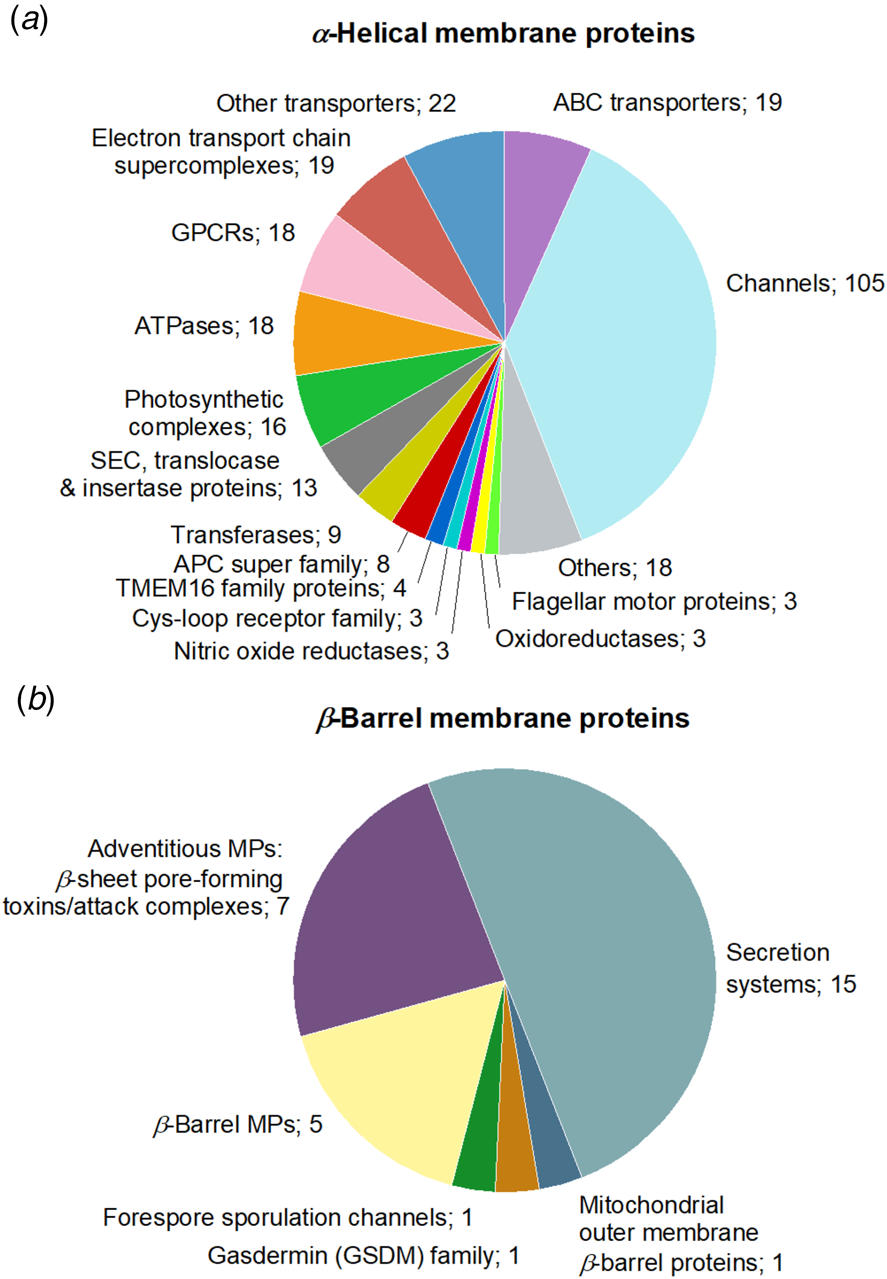

Structural studies of eukaryotic MPs have strongly benefited from progresses in SP cryo-EM, to the point that currently ~76% of the unique MP structures solved by this technique are those of eukaryotic MPs, versus ~35% of those solved by X-ray crystallography (Fig. 2a). Among eukaryotic cryo-EM MP structures, mammalian proteins represent ~68%, an evolution that also reflects recent progresses in expression strategies (Fig. 2b). Challenging protein complexes whose structural determination was not technically possible 10 years ago are now accessible. The distribution of structures obtained by cryo-EM is overwhelmingly in favor of integral MPs with α-helical (89%) rather than β-barrel transmembrane domains (~9%), whereas monotopic MPs represent ~2%. The main subgroups of α-helical MPs are channels, ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, electron transport chain supercomplexes, GPCRs, and ATPases (Fig. 3a), secretion complexes constituting the main subgroup of β-barrel MPs (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 2. Distribution of unique MP structures according to biological origin. (a) Unique MP structures were classified into five groups (archaea, bacteria, eukaryotes, viruses, and unclassified). The latter group comprises four crystallographic structures of de novo designed MPs. (b) Repartition of mammalian versus other eukaryotic MP structures solved by either SP cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography over the past 6 years.

Fig. 3. Family distribution of unique MP structures solved by SP cryo-EM. The groups of (a) α-helical and (b) β-barrel MPs gather 281 and 30 unique MP structures, respectively. ‘Others’, in the α-helical MP group, refers to cryo-EM structures of MPs belonging to the membrane-spanning 4-domain (MS4) family, antiporters, cellulose synthases, sterol-sensing domain (SDD) proteins, Type VII secretion systems, intramembrane proteases, adventitious MPs (α-helical pore-forming toxins), host-defense proteins, decarboxylases, novel receptors (STRA6 retinol-uptake receptor in complex with calmodulin), transhydrogenases, adenylyl cyclases, chain length determinant proteins, and glycoproteins. ‘Other transporters’ gather one cryo-EM structure of drug/metabolite transporter, two structures of H+/Cl− or F− exchange transporters, two structures of transporters belonging to the major facilitator superfamily (MFS), three structures of multi-drug efflux transporters and, finally, fourteen structures of MPs belonging to the solute carrier (SLC) transporter superfamily.

The resolutions achieved using SP cryo-EM keep improving from year to year. In 2018, the structure with the highest resolution was that of a voltage-gated sodium channel, obtained at 2.8 Å resolution when bound to the gating modifier toxin Dc1a (PDB accession code: 6A90) and at 2.6 Å resolution in the presence of the pore blocker tetrodotoxin (PDB accession code: 6A95) (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Li, Jiang, Pan, Wu, Cristofori-Armstrong, Smith, Chin, Lei, Zhou, King and Yan2018). In 2019, a resolution of 2.37 Å was achieved for the structure of tetrameric Photosystem I (PDB accession code: 6K61) (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Li, Li, Zhong, Li, Zhang, Zhang, Chu, Ma, Li, Zhao and Gao2019). Finally, in 2020, the threshold of 2 Å resolution was crossed with the structure of the sheep connexin-46 solved at 1.9 Å (PDB accession code: 7JKC) (Flores et al., Reference Flores, Haddad, Dolan, Myers, Yoshioka, Copperman, Zuckerman and Reichow2020) and that of a homopentameric β3 γ-aminobutyric acid type-A receptor solved at 1.7 Å (PDB accession code: 7A5 V) (Nakane et al., Reference Nakane, Kotecha, Sente, McMullan, Masiulis, Brown, Grigoras, Malinauskaite, Malinauskas, Miehling, Uchański, Yu, Karia, Pechnikova, de Jong, Keizer, Bischoff, McCormack, Tiemeijer, Hardwick, Chirgadze, Murshudov, Aricescu and Scheres2020).

Despite this dramatic progress in improving the resolution of SP cryo-EM data, one should keep in mind that many of the atomic models reported in the PDB have benefited from docking high-resolution structures derived from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or other cryo-EM studies as initial templates into cryo-EM maps. Structures of soluble extramembrane domains or homologous proteins from different species are often used. Rigid or flexible fitting methods are commonly applied for the validation and interpretation of cryo-EM structures (compared to rigid fitting methods, flexible ones allow conformational changes that improve fitting the model into the experimental map). Many atomic models derived from cryo-EM result therefore from a mix between these different approaches rather than being fully ab initio structures. The higher the resolution achieved, of course, the safer is the resulting model, which is a strong incentive for improving the quality of experimental data. Which biochemical approaches are being developed to this end is the main subject of this review.

Selection of reports

Despite technical advances, substantial barriers still stand in the way of many cryo-EM projects. Obtaining cryo-EM grids of sufficient quality for high-resolution structural analysis is not a trivial task. There is no unique answer to the question, ‘Which detergent or detergent substitute is the most appropriate for MP structural determination by SP cryo-EM?’ In any study, the final choice of the surfactant(s) in which the structure will be determined depends not only on the target MP, but also on the relative amount of efforts invested optimizing one or another set of experimental conditions. A surfactant that appeared inferior in a first study can thus provide superior results in another. For instance, it was initially observed that the human γ-secretase yielded a higher-resolution cryo-EM structure in APol A8-35 than in digitonin (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Bai, Ma, Xie, Yan, Sun, Yang, Zhao, Zhou, Scheres and Shi2014), whereas, a few years later, using a version of γ-secretase fused with T4 lysozyme, two other structures were obtained in digitonin at a higher resolution than that initially achieved in A8-35 (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Zhou, Zhou, Guo, Yan, Ke, Lei and Shi2019; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Yang, Guo, Zhou, Lei and Shi2019). Beyond some obvious limitations, such as the fact that current membrane scaffold protein (MSP)-based NDs (Denisov and Sligar, Reference Denisov and Sligar2017; Sligar and Denisov, Reference Sligar and Denisov2020) cannot accommodate MPs with very large transmembrane domains and thus are not appropriate for studying large supercomplexes (see below), trial-and-error is still the only way to proceed. Yet, examining the set of all MP structures determined to-date by SP cryo-EM reveals some interesting trends that can help selecting the most promising tools.

Analyzing unique MP structures provides an overview of the types of structures solved and their biological origin. Based on this dataset, an analysis of the surfactants used for solubilization and structure determination of MPs (whatever the structural approach used) has been recently published (Choy et al., Reference Choy, Cater, Mancia and Pryor2021). However, the structure of a given MP has often been published more than once, generating several PDB files for the same protein. In the present study, we chose to include all of these data, hereafter called ‘published reports’. This raises the number of experimental situations from 1195 unique structures to 2212 published reports (Fig. 4). As regards cryo-EM alone (including both SP and electron crystallography), this number increases from 328 unique structures (187 in Choy et al. (Reference Choy, Cater, Mancia and Pryor2021)) to 616 reports, thus providing a more exhaustive view of the extent to which each type of surfactant is used. Most of the structures have been obtained by SP cryo-EM analysis (316 unique MP structures, 587 reports). The number of α-helical MPs almost doubles, with 536 reports versus 281 unique structures (six reports missing from S. White's database have been included in the list (Wang and Sigworth, Reference Wang and Sigworth2009; Glavier et al., Reference Glavier, Puvanendran, Salvador, Decossas, Phan, Garnier, Frezza, Cece, Schoehn, Picard, Taveau, Daury, Broutin and Lambert2020; Hua et al., Reference Hua, Li, Wu, Iliopoulos-Tsoutsouvas, Wang, Wu, Shen, Johnston, Nikas, Song, Song, Yuan, Sun, Wu, Jiang, Grim, Benchama, Stahl, Zvonok, Zhao, Bohn, Makriyannis and Liu2020; McDowell et al., Reference McDowell, Heimes, Fiorentino, Mehmood, Farkas, Coy-Vergara, Wu, Bolla, Schmid, Heinze, Wild, Flemming, Pfeffer, Schwappach, Robinson and Sinning2020; Yao et al., Reference Yao, Fan and Yan2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhao, Gao, Wu, Gao, Zhang, Wang, Wu, Wu, Gurcha, Veerapen, Batt, Zhao, Qin, Yang, Wang, Zhu, Zhang, Bi, Zhang, Yang, Guddat, Xu, Wang, Li, Besra and Rao2020)). Here again, the most representative subgroups include channels, ABC transporters, electron transport chain supercomplexes, ATPases, and GPCRs. The latter comprise 67 structures overall for only 18 unique ones. The resolution of the vast majority of structures reported lies between 2 and 5 Å (554 over 593 files, i.e. >90%), with a median around 3.4–3.5 Å. Knowing that the resolution of cryo-EM maps is usually not uniform due to protein flexibility and dynamics, which tend to degrade the resolution at the periphery of the protein as compared to its core, the resolution value is usually given on an indicative basis. Somewhat arbitrarily, a threshold of 5 Å resolution (sufficient to fit α-helices into EM maps) was chosen for a structure to be included in our analysis, the aim being to obtain as broad an overview as possible of the diversity of surfactants that can be used to achieve near-atomic resolution, while leaving aside those that have not yet proven up to this task. In certain studies, SP cryo-EM analysis of a given MP was performed in two or three distinct environments, leading to the refinement of several models deposited in the PDB. This is a very interesting situation, whose lessons will be discussed below. To obtain the widest possible view of all usable environments, such ‘duplicate’ structures have been included when appropriate (i.e. whenever several distinct structures have been deposited in the PDB and/or the electron microscopy data bank (EMDB)), increasing the number of experimental situations that have yielded 2-5 Å resolution structures from 554 to 604 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Number of unique cryo-EM MP structures and published reports analyzed in this study. Among the cryo-EM structures, SP analysis is the predominant technique, only nine unique MP structures having been solved using electron crystallography. Most cryo-EM MP structures have been solved by SP analysis applied to images of isolated MPs embedded in vitreous ice, one and two structures having been obtained by SP analysis applied to 2D crystals and helical assemblies, respectively. The list of reports analyzed comes from Stephen White's database, manually completed with 60 SP cryo-EM structures for which a PDB and/or EMDB accession number was available (see below). Two cryo-EM structures of MPs reconstituted into liposomes have been included. In addition, examination of each of the 587 studies revealed that some cryo-EM structures were missing. They have been manually integrated into the list of reports as follows: (a) in four studies, an additional cryo-EM structure of a distinct MP or MP complex was identified and added to the list of reports, (b) in 50 studies, a 3D reconstruction of a MP has been obtained in two different surfactants, yielding two distinct refined structures, generating two sets of experimental conditions that have been included in our analysis as ‘duplicates’, and (c) in two studies, the cryo-EM structure of a MP has been obtained in three different surfactants, yielding ‘triplicates’. These additional experimental conditions were gathered in three groups: ‘Duplicates 1’: distinct cryo-EM structures were obtained in two (or three) different surfactants, whereas the detergent used for the purification was unchanged; ‘Duplicates 2’: both the purification and vitrification surfactants differed; ‘Duplicates 3’: the vitrification surfactant was the same but the purification was performed in two distinct detergents.

An overview of surfactant usage at the vitrification step

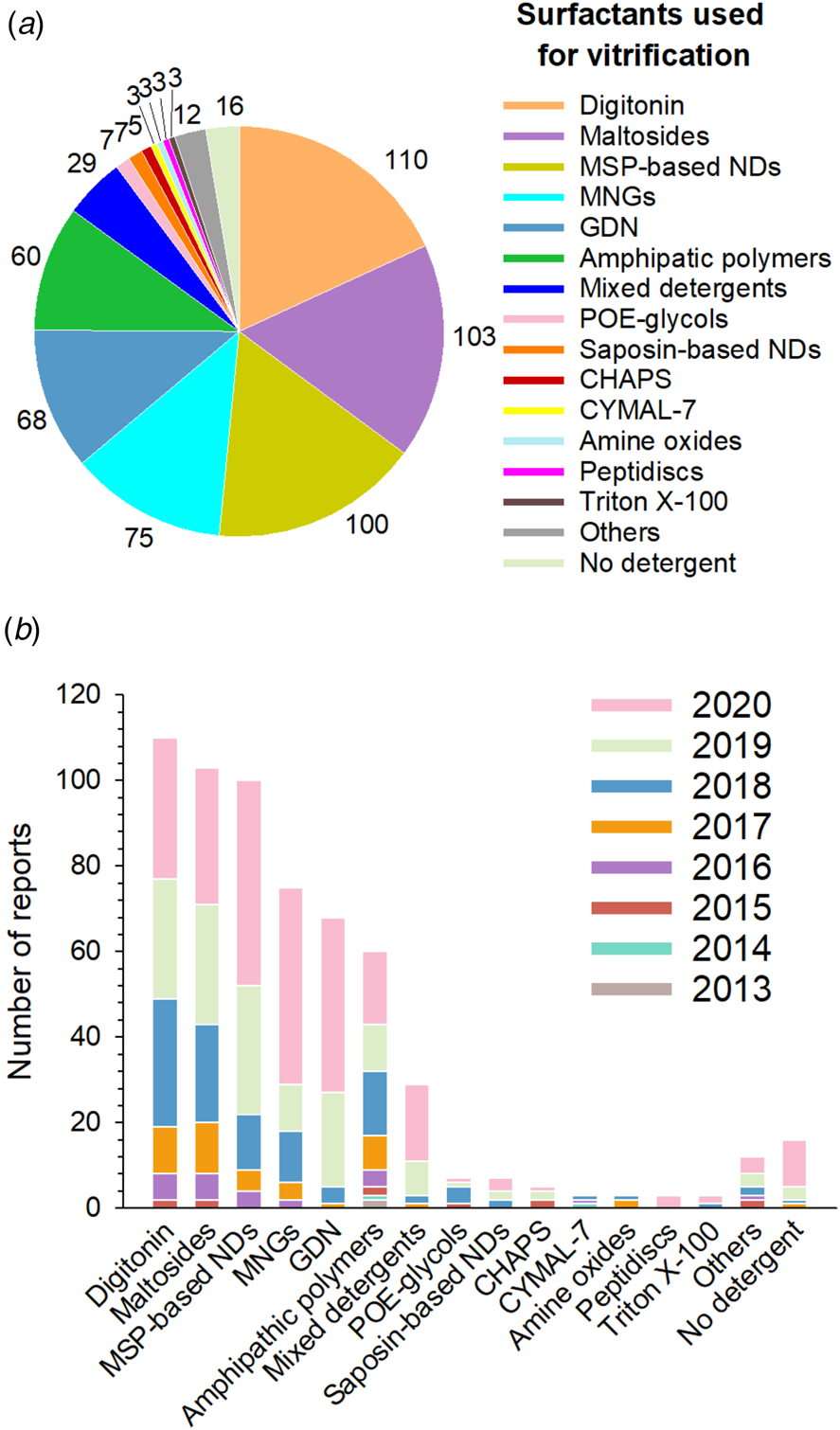

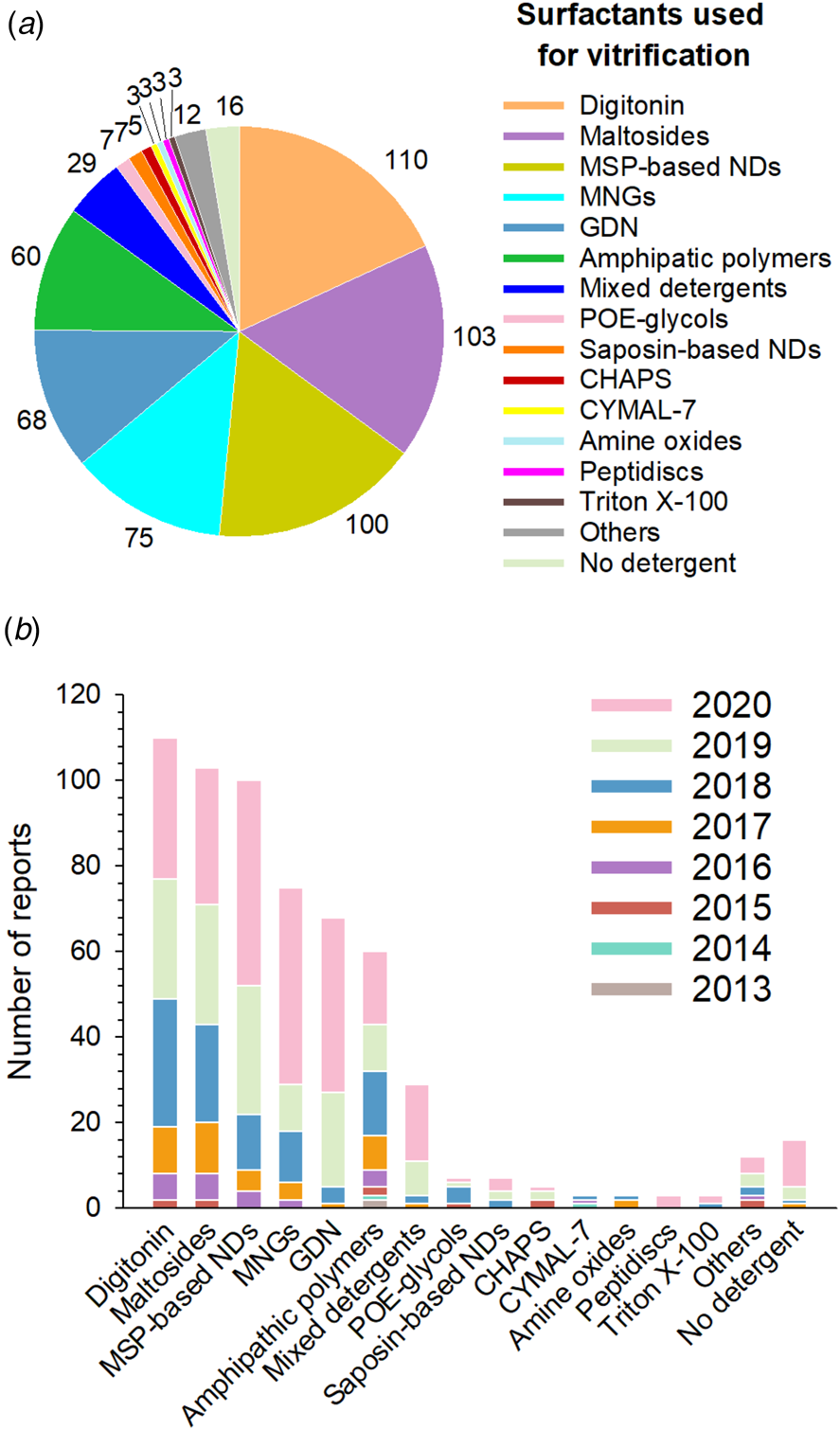

Among SP cryo-EM structures obtained at a resolution of 5 Å or better (hereafter noted ⩽5 Å), the six surfactants most frequently used for vitrification are, in order of decreasing frequency of use, (1) digitonin, (2) detergents with a single maltose-based polar moiety and a single alkyl chain (mostly n-dodecyl-α- (or β-) d-maltoside (DDM), occasionally undecyl- or decyl-maltoside (respectively UDM and DM)), (3) MSP-based NDs, (4) detergents belonging to the maltoside-neopentyl glycol (MNG) family, which feature two maltose-based polar heads and two alkyl chains, (5) glyco-diosgenin (GDN), and (6) classical APols (mainly A8-35 and PMAL-C8) (Figs 5–7).

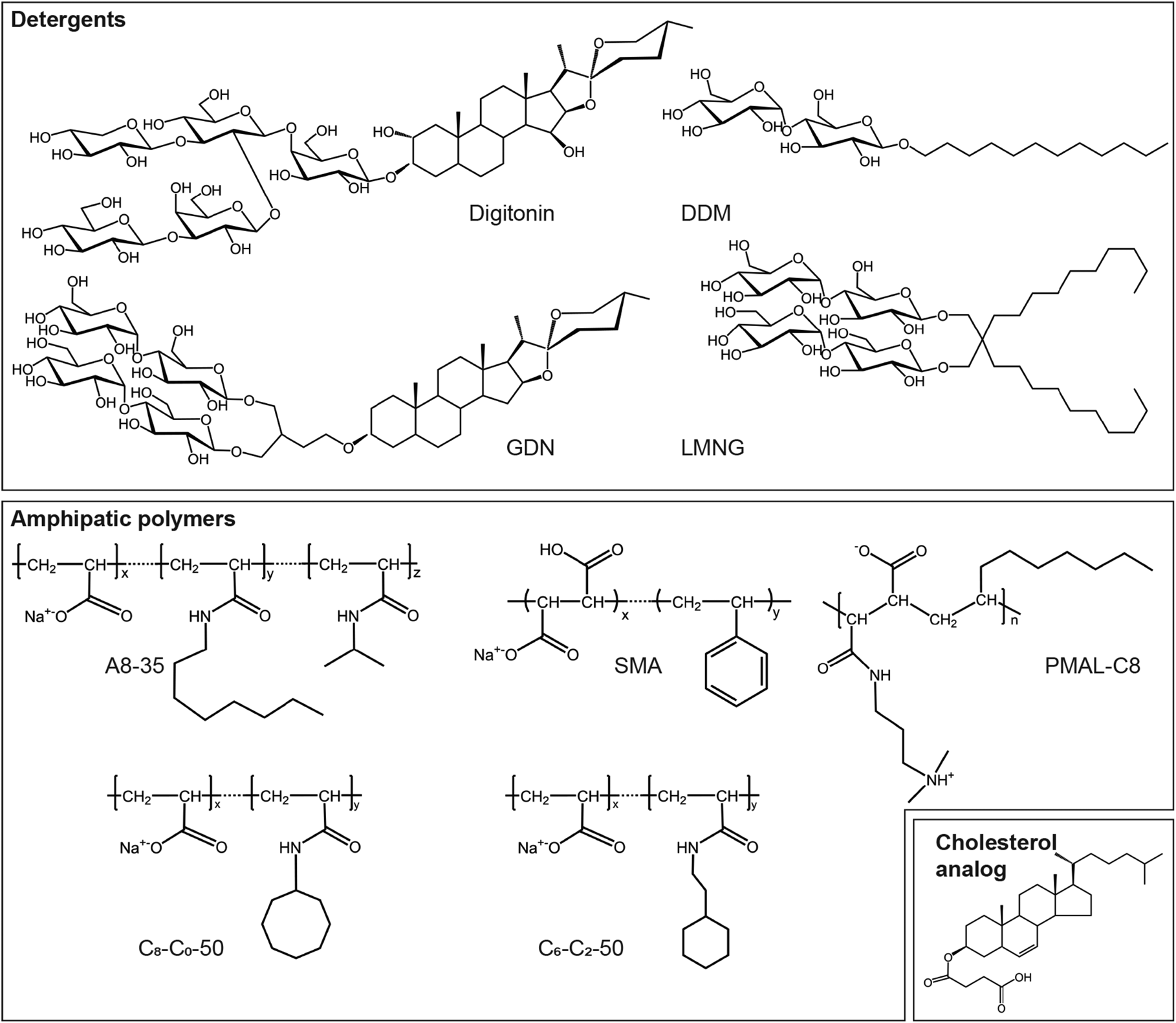

Fig. 5. Some of the amphipathic environments used for MP stabilization. Chemical structures of detergents: digitonin, glyco-diosgenin (GDN), n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM) and Lauryl Maltoside-Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG); APols: A8-35, PMAL-C8, SMA, and CyclAPols C8-C0-50 and C6-C2-50; hydrosoluble cholesterol analog: cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS).

Fig. 6. Membrane protein structures established in protein-based nanodiscs. (a) Molecular model of an MSP-based ND (side view). The two MSPs are shown in red and blue, the 160 associated lipids in orange and grey. From Shih et al. (Reference Shih, Denisov, Phillips, Sligar and Schulten2005). (b) Molecular model of a saposin-based ND (top view). The saposin A dimer is in purple, the 26 associated lipid molecules in reddish brown. From Li et al. (Reference Li, Richards, Bagal, Campuzano, Kitova, Xiong, Privé and Klassen2016). (c) Family distribution of MPs whose structures have been solved after reconstitution in protein-based NDs. ‘Other transporters’ comprise cryo-EM structures of three multi-drug efflux transporters, three amino acid secondary transporters, three major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters, and three transporters distributed among the three superfamilies of drug/metabolite transporters (DMT), CorA ion transporters and solute carrier (SLC) transporters. (d) Distribution of MSPs and lipids used to reconstitute MPs in protein-based NDs. The MSP called zap1 is derived from Zebra fish apo-lipoprotein A-1; MSP2X was constructed by linking two MSP1E3D1 chains with a two-amino acid linker; csMSP1E3D1 is a circularized version of MSP1E3D1. In three studies, the MSP used has not been clearly mentioned (‘unspecified’). When the lipids were a mix of natural and synthetic lipids, they are noted as ‘natural and synthetic lipids’; when their nature has not been clearly mentioned, as ‘natural or synthetic lipids’.

Fig. 7. Surfactants used at the vitrification step. (a) Distribution of all surfactants in which MP structures have been solved by SP cryo-EM to a resolution ⩽5 Å (604 reports overall, taking all duplicates into account). (b) Number of near-atomic resolution MP structures reported each year since 2013 according to the type of surfactant used at the vitrification step. ‘Others’ gather two cryo-EM structures obtained in Brij-35 and ten other structures obtained in one of the following surfactants: Tween 20, Igepal CA-630 (NP40), lauryldimethylamine oxide, MNA-C12, PCC-a-M, sodium cholate, Facade-EM (FA-3), octyl glucoside, sodium deoxycholate, and liposomes. Sixteen of the cryo-EM structures gathered in Stephen White's database are either MP fragments, toxins, or peripheral MPs vitrified in the absence of detergent.

Digitonin, the most popular surfactant, was used for ~18% of MP structures determined at resolutions ⩽5 Å (Fig. 7a). This natural detergent is a pentasaccharide derivative of steroidal aglycon digitogenin, produced by the purple foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) (Fig. 5). Commercial digitonin is in fact a mixture consisting of about five glycosides, the main components of this mixture being digitonin and digalonin, a saponin of similar structure, in which the 2-hydroxy digitogenin is missing (Fukunaga et al., Reference Fukunaga, Szabo, Fales and Pitha1988). Commercial preparations of digitonin cannot be used directly, because even the best preparations contain 30–50% w/w of material that cannot be dispersed evenly in water, and the effects of unpurified digitonin are unpredictable. Therefore, purification of commercial digitonin by recrystallization is recommended (Kun et al., Reference Kun, Kirsten and Piper1979). Whereas digitonin presents quite a few drawbacks, such as batch-to-batch variations, formation of large micelles, crystallization at low temperature and ill-defined critical micellar concentration (CMC <0.5 mM), it is widely used in cryo-EM due to its mildness. GDN is a recent synthetic detergent (Chae et al., Reference Chae, Rasmussen, Rana, Gotfryd, Kruse, Manglik, Cho, Nurva, Gether, Guan, Loland, Byrne, Kobilka and Gellman2012), whose chemical structure mimics that of digitonin (Fig. 5). Due to its homogeneity, the CMC of GDN, which is very low (~18 μM), is better defined than that of digitonin (Chae et al., Reference Chae, Rasmussen, Rana, Gotfryd, Kruse, Manglik, Cho, Nurva, Gether, Guan, Loland, Byrne, Kobilka and Gellman2012). SP cryo-EM structures of GDN-solubilized MPs appeared for the first time in 2017. Three years later, its use is reported more often than that of digitonin (in 41 structures versus 33 for digitonin) (Fig. 7b).

The second most widely used surfactants in cryo-EM are maltoside detergents such as DDM, UDM and DM, with a clear preference for DDM (86 structures out of 103). DDM (Fig. 5) was developed in the mid ‘70s to early ‘80s (Rosevear et al., Reference Rosevear, VanAken, Baxter and Ferguson-Miller1980) and has been widely used in X-ray crystallography (Dilworth et al., Reference Dilworth, Piel, Bettaney, Ma, Luo, Sharples, Poyner, Gross, Moncoq, Henderson, Miroux and Bill2018; Choy et al., Reference Choy, Cater, Mancia and Pryor2021). The polar head of DDM, UDM and DM is provided by a disaccharide (maltose), whereas the hydrophobic parts are 12-, 11-, and 10-carbon n-alkyl chains, respectively. The CMC value of DDM is low (~0.17 mM for β-DDM) and it forms well-defined micelles; UDM and DM have higher CMC values (0.59 and 1.8 mM, respectively) (Bhairi and Mohan, Reference Bhairi and Mohan2007; Stetsenko and Guskov, Reference Stetsenko and Guskov2017; and see Table 2 in Abeyrathne et al. (Reference Abeyrathne, Arheit, Kebbel, Castano-Diez, Goldie, Chami, Stahlberg, Renault and Kühlbrandt2012)).

MNG detergents were synthesized and initially used mainly for GPCR crystallization (Chae et al., Reference Chae, Rasmussen, Rana, Gotfryd, Chandra, Goren, Kruse, Nurva, Loland, Pierre, Drew, Popot, Picot, Fox, Guan, Gether, Byrne, Kobilka and Gellman2010). These molecules carry two alkyl chains and two hydrophilic groups derived from maltose, linked via a central quaternary carbon atom (Fig. 5). Because of the presence of two long alkyl chains, MNGs have very low CMCs (e.g. ~10 μM for LMNG, which is by far the most widely used MNG, with 73 structures out of 75). While MNGs appear only at the fourth position of the most frequently used surfactants, with an overall frequency of ~12% (Fig. 7a), they represent one of the surfactant classes most frequently used in 2020 (Fig. 7b), partly due to their use for solving GPCR structures.

The third and sixth most often used surfactant classes are, respectively, protein-based NDs and amphipathic polymers called APols, both developed in the ‘90s. These two detergent substitutes are structurally very different, but both aim at solving the problem of detergent-induced MP instability by eliminating the detergent altogether.

APols constitute a family of short and flexible amphipathic polymers specially developed for MP biochemistry (Tribet et al., Reference Tribet, Audebert and Popot1996; Popot et al., Reference Popot, Althoff, Bagnard, Banères, Bazzacco, Billon-Denis, Catoire, Champeil, Charvolin, Cocco, Crémel, Dahmane, de la Maza, Ebel, Gabel, Giusti, Gohon, Goormaghtigh, Guittet, Kleinschmidt, Kühlbrandt, Le Bon, Martinez, Picard, Pucci, Sachs, Tribet, van Heijenoort, Wien, Zito and Zoonens2011; Zoonens and Popot, Reference Zoonens and Popot2014; Popot, Reference Popot2018) (Fig. 5). For a long time, when X-ray crystallography was the predominant technique in MP structural biology, APols were considered relatively unattractive. This was due to the mistaken view that the use of polydisperse molecules would hinder crystallization. This point is not necessarily relevant, given that most of the molecules comprising the surfactant belt are disordered anyway (for discussions, see Charvolin et al. (Reference Charvolin, Picard, Huang, Berry and Popot2014), and Chapter 11 in Popot, Reference Popot2018). Indeed, a recent study has shown that a mix of DDM and A8-35 (the latter used as a stabilizing agent) allows one to solve the X-ray structure of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B at a higher resolution than can be achieved with DDM alone (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Georgieva, Borbat, Freed and Heldwein2018; Cooper and Heldwein, Reference Cooper and Heldwein2020). More to the point is the fact that early APols carried charged polar moieties, which tend to hamper 3D crystallization, whereas non-ionic APols (NAPols) (Bazzacco et al., Reference Bazzacco, Billon-Denis, Sharma, Catoire, Mary, Le Bon, Point, Banères, Durand, Zito, Pucci and Popot2012) have only recently become commercially available. The use of APols has been reported in >100 EM studies (those published from 1998 until late 2017 are reviewed in Chapter 12 of Popot, Reference Popot2018). In the present analysis, only the cryo-EM structures of APol-complexed MPs included in Stephen White's database with resolutions ⩽5 Å have been taken into consideration. Out of 60 cryo-EM MP structures determined using APols, 34 were obtained in A8-35 (Tribet et al., Reference Tribet, Audebert and Popot1996) (Fig. 5) and 19 in PMAL-C8 (Nagy et al., Reference Nagy, Kuhn Hoffmann, Keyes, Gray, Oxenoid and Sanders2001) (Fig. 5). A8-35 first left its mark in SP cryo-EM with the low-resolution structure (at ~19 Å) of a mammalian MP supercomplex, that of the bovine mitochondrial respirasome (Althoff et al., Reference Althoff, Mills, Popot and Kühlbrandt2011). It also led to the first near-atomic resolution structures (at 3.8 and 3.27 Å) of a MP ever solved by SP cryo-EM, those of the transient receptor potential cation channel V1 (TRPV1) (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Liao, Cheng and Julius2013; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Cao, Julius and Cheng2013). To date, the use of NAPols has been reported in only one cryo-EM structure, that of the outer mitochondrial membrane translocase (TOM) core complex (PDB accession code: 5O8O); however, due to indistinguishable 3D maps of the complex in DDM and NAPols, the two datasets have been merged into a single map refined to 6.8 Å (Bausewein et al., Reference Bausewein, Mills, Langer, Nitschke, Nussberger and Kühlbrandt2017) and therefore have not been included among the reports analyzed in this review.

The co-polymerization of styrene and maleic acid yields APol variants known as SMA co-polymers (Fig. 5). SMAs form with lipids and MPs the so-called SMALPs. Their interest derives mainly from their ability to extract MPs from membranes without resorting to detergents (Knowles et al., Reference Knowles, Finka, Smith, Lin, Dafforn and Overduin2009; Stroud et al., Reference Stroud, Hall and Dafforn2018). As of January 1, 2021, only four MP structures had been solved at high resolution using SMAs (Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Fu, Xu, Grassucci, Zhang, Frank, Hendrickson and Guo2018; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Benlekbir, Venkatakrishnan, Wang, Hong, Hosler, Tajkhorshid, Rubinstein and Gennis2018; Tascón et al., Reference Tascón, Sousa, Corey, Mills, Griwatz, Aumüller, Mikusevic, Stansfeld, Vonck and Hänelt2020; Yoder and Gouaux, Reference Yoder and Gouaux2020), probably due to a set of limitations that have already been discussed elsewhere (Autzen et al., Reference Autzen, Julius and Cheng2019). For instance, the isolation conditions with SMAs (typically, high ionic strength buffers such as 500 mM NaCl or l-arginine) and/or the purification conditions (12–24 h of incubation with affinity resins) tend to be too harsh for fragile MPs of mammalian origin.

CyclAPols, a novel generation of APols that carry cyclic, saturated hydrocarbon chains instead of alkyl ones (Fig. 5), have also proven able to directly extract MPs without resorting to detergents while stabilizing target MPs to the same extent as classical APols (Marconnet et al., Reference Marconnet, Michon, Le Bon, Giusti, Tribet and Zoonens2020). With these molecules, the usual protocol of detergent/APol exchange is therefore no longer mandatory. CyclAPols have been recently validated for high-resolution structure determination by SP cryo-EM (Higgins et al., submitted for publication).

Finally, protein-based NDs are nanometric-sized objects of discoidal shape formed by lipid bilayer patches stabilized by two encircling amphipathic helical proteins derived from apolipoprotein A1, called MSPs (Fig. 6a; for recent reviews, see Denisov and Sligar, Reference Denisov and Sligar2017; Denisov et al., Reference Denisov, Schuler and Sligar2019; Sligar and Denisov, Reference Sligar and Denisov2020). The total number of MP structures established in MSP-based NDs at resolutions ⩽5 Å is 100. Seven additional structures have been reported using a related system, called Salipro, where another protein, saposin A, replaces MSPs (Fig. 6b) (Frauenfeld et al., Reference Frauenfeld, Löving, Armache, Sonnen, Guettou, Moberg, Zhu, Jegerschöld, Flayhan, Briggs, Garoff, Löw, Cheng and Nordlund2016). Furthermore, three other structures have been obtained with a system called peptidiscs, based on reconstituting the detergent-solubilized MP into short amphipathic bi-helical peptides derived from the apolipoprotein A1 in the absence of additional lipids (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Young, Zhao, Fabre, Jun, Li, Li, Dhupar, Wason, Mills, Beatty, Klassen, Rouiller and Duong2018). The main groups of MPs whose structures have been solved after reconstitution in protein-based NDs are channels, ABC transporters, ATPases, Cys-loop receptors and members of the TMEM16 family (Fig. 6c). At variance with other amphipathic environments, which depend on securing surfactants from commercial sources, protein-based NDs can be produced in the laboratory. MSPs, which can be expressed in E. coli, have been engineered to form NDs of various diameters compatible with the incorporation of MPs of different transmembrane domain sizes. MSP2N2, MSP1E3D1 and MSP1D1 form NDs with diameters comprised between ~10 and ~17 nm (Denisov et al., Reference Denisov, Grinkova, Lazarides and Sligar2004; Grinkova et al., Reference Grinkova, Denisov and Sligar2010) and are the most frequently used MSPs, with 37, 24 and 22 cryo-EM structures, respectively (Fig. 6d). Up to now, the largest transmembrane domains embedded in MSP-based NDs are those of the yeast vacuolar ATPase V o proton channel (Roh et al., Reference Roh, Stam, Hryc, Couoh-Cardel, Pintilie, Chiu and Wilkens2018, Reference Roh, Shekhar, Pintilie, Chipot, Wilkens, Singharoy and Chiu2020) and of the human calcium homeostasis modulator 5 (CALHM5) (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wan, Jin, Li, Bhat, Guo, Lei, Guan, Wu and Ye2020), which comprise 48 and 44 transmembrane α-helices, respectively. Despite a lower number of transmembrane α-helices, the diameter of CALHM5 is wider than that of ATPase V o due to the presence of a large 60 Å diameter pore at the center. In this study, circularized NDs in which the N and C termini of MSPs are covalently linked were used, whereas conventional MSP1E3D1 yielded NDs of sufficient size to accommodate the transmembrane domain ATPase V o. Circularized NDs were engineered to be more homogeneous and stable than standard NDs (Nasr et al., Reference Nasr, Baptista, Strauss, Sun, Grigoriu, Huser, Plückthun, Hagn, Walz, Hogle and Wagner2017; Nasr and Wagner, Reference Nasr and Wagner2018). Circularized MSPs can form NDs of larger diameter (50 nm, and up to 80 nm) as compared to standard MSPs, but these wider NDs have yet to yield high-resolution cryo-EM structures.

Regarding the lipid components, lipid extracts from natural sources (soybean, brain, E. coli, yeast and thylakoids) are found in almost half of the MP structures established in protein-based NDs (46 cases), whereas pure or mixed synthetic phospholipids are found in 44 cases (Fig. 6d). The most frequently used NDs are those resulting from a combination of MSP2N2 and natural lipids.

In 2019 and 2020, MSP-based NDs have been the most widely used system in SP cryo-EM (Fig. 7b) because the important role of lipid/MP interactions is being paid increasing attention to. This justifies the choice of NDs, which, at the cost of a lengthy optimization process required to obtain high-quality samples, allows one to solve MP structures in an artificial lipid bilayer more similar to the native membrane than any of the other surfactants used in SP cryoEM, barring liposomes. In the past, analyses of MPs embedded into liposomes were essentially performed by subtomography cryo-EM, yielding medium- to low-resolution structural data. More recently, imaging liposome-embedded MPs using SP cryo-EM has been developed based on the method of random spherically constrained SP reconstruction. This approach relies on fitting and subtracting a model of the membrane contribution to each image and reconstituting the MP particles alone (Wang and Sigworth, Reference Wang and Sigworth2010; Tonggu and Wang, Reference Tonggu and Wang2020). It has yielded cryo-EM structures of the large conductance voltage- and calcium-activated potassium (BK) channels first at 17 Å (Wang and Sigworth, Reference Wang and Sigworth2009), and then at 3.5 Å (Tonggu and Wang, Reference Tonggu and Wang2018). Recently, another method of cryo-EM data processing was developed to determine high-resolution structures of MPs reconstituted into liposomes, as exemplified by the 3.9 Å structure of the multidrug-resistant transporter AcrB (Yao et al., Reference Yao, Fan and Yan2020). These approaches have the unique potential of making it possible to examine the structure of MPs under conditions where they experience a gradient of solutes or a transmembrane electric field. One should nevertheless bear in mind that none of these systems, be they liposomes, MSP-based NDs, SMALPs or MP/APol/lipid complexes, provides MPs with an environment identical to that of the native membrane, if only because, in the latter, the two monolayers have different compositions (for a discussion, see Chapter 3 in Popot, Reference Popot2018).

A practice worth mentioning is the addition, to surfactant-solubilized MPs, of cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS; Fig. 5), a water-soluble cholesterol analog that improves the stability of many purified MPs (Weiss and Grisshammer, Reference Weiss and Grisshammer2002; Magnani et al., Reference Magnani, Shibata, Serrano-Vega and Tate2008; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Liu, Chun, Wacker, Wu, Cherezov and Stevens2011). According to published reports, 207 MPs out of 604 have been solubilized in the presence of CHS, and in 90 cases, CHS was kept along with the purification surfactants, which are preferentially maltoside-derived detergents and MNGs (Fig. 8a). In total, 71% of the MP structures solved in the presence of CHS, many of which are GPCRs and channels (Fig. 8b), have been obtained with these two detergents. With respect to the total number of MP structures solved in these two surfactant classes, the use of CHS represents 37% of the cases.

Fig. 8. Addition of cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS) to MP samples. (a) Purification surfactants used in combination with CHS. (B) Distribution of MP structures solved in the presence of CHS among protein classes. ‘Others’ are as described in the legend to Figure 7.

For the sake of exhaustiveness, the present analysis has considered all SP cryo-EM structures solved to resolutions ⩽5 Å. One may argue that a threshold of 4 Å is more appropriate for building high-resolution models (Cheng, Reference Cheng2015). However, this would have reduced the number of experimental conditions to be analyzed from 604 to 487. We have checked that lowering the threshold from 5 to 4 Å has no impact on the general conclusions, i.e. the six most frequently used surfactants remain the same, their ranking changing as follows: MSP-based NDs now come first, with 18% of the structures, closely followed by maltoside detergents and digitonin, with almost 18 and 17%, respectively, then MNGs and GDN, each with 12%, and APols with ~9%. One clear lesson is that, as of now, no surfactant has emerged as the universal best environment for high-resolution SP cryo-EM.

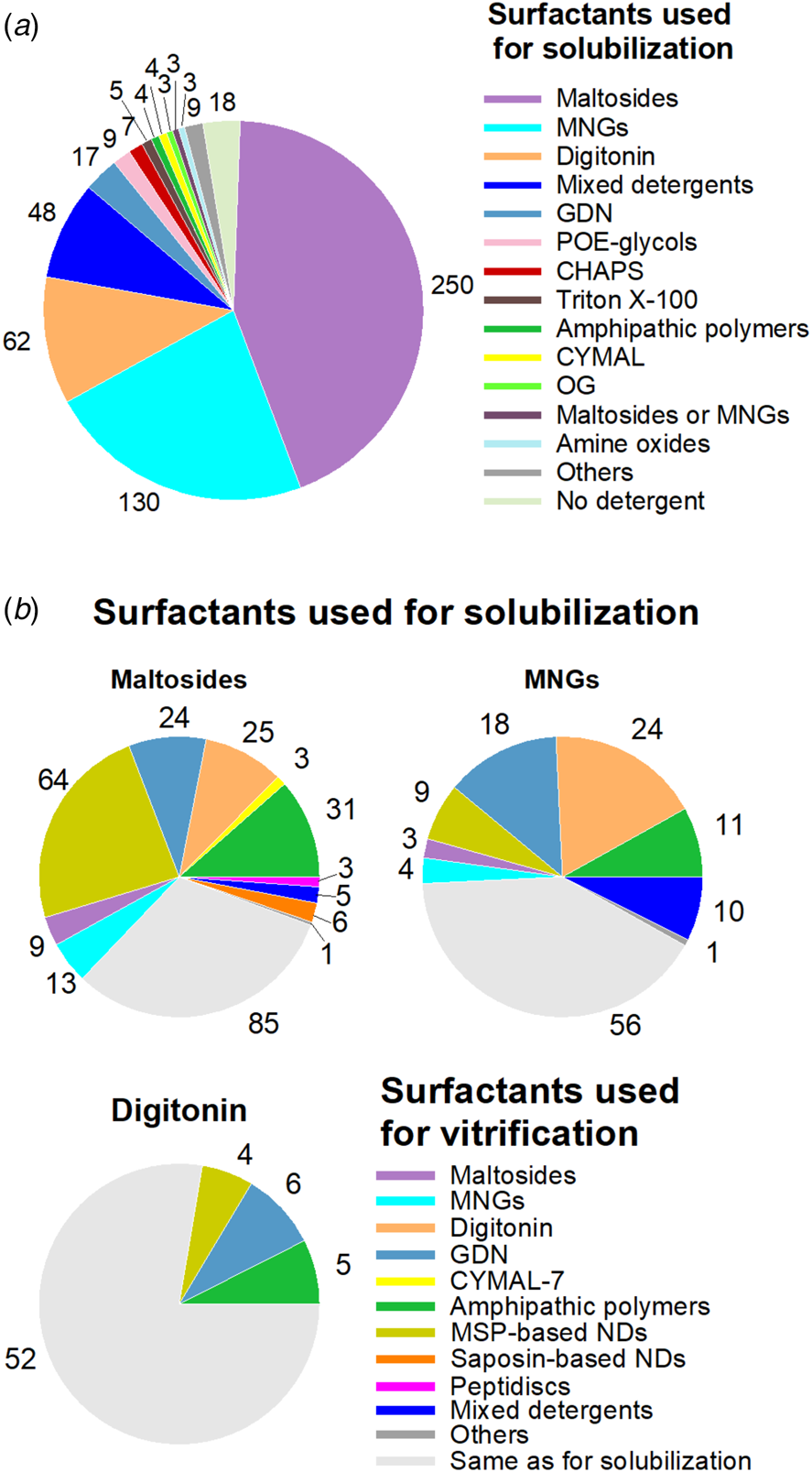

Surfactant exchange before sample application to the grid

The surfactant used for protein purification is very often exchanged before the sample is applied onto the grids (Fig. 9; for references, see Table S1 in the Supplementary Information). Most often, extraction from the membrane and the first steps of purification are performed using one surfactant (hereafter referred to as the ‘purification surfactant’), whereas the last steps are used to exchange it for that in which the sample will be vitrified (‘vitrification surfactant’). Maltoside detergents are most frequently used for purification (~44%), followed by MNGs (~23%) and digitonin (~11%) (Fig. 9a). However, in ~68% of cases, MPs purified in maltoside detergents (essentially DDM) were subsequently transferred to a different amphipathic environment, most often MSP-based NDs, APols, digitonin, or GDN, before applying the sample to the grids (Fig. 9b). In nine cases, the maltoside detergent used for purification was exchanged for another maltoside detergent. Exchange of MNGs is also very common (~59% of cases), most often for digitonin, GDN or APols. Digitonin is less often exchanged. Out of 67 structures of MPs purified in digitonin (taking into account duplicates), 52 were obtained without resorting to surfactant exchange (Fig. 9b). Figure 10 summarizes, for each of the six types of surfactants most commonly used at the vitrification step, which medium the proteins were initially purified in. Slightly more than half of MPs whose structure was solved in digitonin were purified in other detergents, mainly maltoside-based detergents and MNGs. The frequent transfer to digitonin of MPs extracted with another detergent is not unexpected, given that digitonin is both less solubilizing and less destabilizing than most detergents. A large fraction of those MPs whose structure was solved in GDN were initially purified in maltoside detergents or in MNGs (Fig. 10).

Fig. 9. Surfactant exchange between MP purification and sample deposit onto cryo-EM grids. (a) Detergents used for MP solubilization and the initial steps of purification. In three cases (labeled ‘Maltoside or MNGs’), the detergent used for solubilization has not been clearly specified. (b) Surfactants used for vitrification, depending on which detergent was used for solubilization, namely either maltoside detergents (mainly DDM), MNGs (mainly LMNG), or digitonin. In Panel A, the analysis includes duplicates provided that the surfactants used for solubilization were different (i.e. including duplicates 2 and 3), whereas in panel (b) all duplicates leading to ⩽5 Å structures have been included. References to studies using the combinations of surfactants shown in panel (b) are given in the Supplementary Information in the legend to Table S1.

Fig. 10. Surfactants used for solubilization and the initial steps of purification, depending on which surfactant was used for vitrification (either digitonin, GDN, MSP-based NDs, APols, maltoside detergents, or MNGs). All duplicates are included. In one case, the detergent used for vitrification has not been clearly specified and could be either maltosides or MNGs.

When MSP-based NDs or APols are used for vitrification, surfactant exchange is most often obligatory, given that neither of these surfactants is effective for direct solubilization. In the case of APols, one can expect that the number of structures solved without surfactant exchange will increase should the use of SMAs and other APols suitable for direct MP extraction, like CyclAPols, develop in the future. Currently, near two-thirds and half of the MPs whose structures were established in MSP-based NDs or in APols, respectively, were purified in maltoside detergents (Fig. 10).

MNGs are also often chosen as final surfactants. Almost three-quarters of the MP structures established in MNGs were obtained without detergent exchange. In 16% of the cases, the MP was first extracted using a maltoside-based detergent. In four cases, the MNG used for purification was exchanged before vitrification for another MNG.

DDM is, by far, the detergent that is the most often used for MP extraction and purification (Fig. 9a). As such, it is, most likely, the first detergent tested in initial imaging attempts. It is therefore noteworthy that DDM is, nevertheless, replaced with another surfactant in more than two-thirds (~68%) of the studies we examined (Fig. 9b). Conversely, DDM and the other maltoside detergents are seldom used to replace the detergent used for purification (Fig. 10). There are likely two main reasons for moving or keeping away from DDM for imaging: (i) the desire to transfer the protein to less perturbing and/or more native-like an environment, and (ii) the higher quality of images obtained with other surfactants. These two issues, of course, are not independent of each other.

Overall, the analysis summarized in Figs 9 and 10 indicates that it is more the exception than the rule that the surfactant used for extraction and purification be the one kept for preparing cryo-EM specimens, as it is exchanged in 60% of the cases. Table S1 of the Supplementary Information provides references to those studies in which the protein was initially obtained in one of the three types of surfactants most commonly used for purification, maltosides, MNGs and digitonin, sorted out according to what the medium used for vitrification was.

In any original study of a new MP, optimization of the purification and vitrification conditions is likely to stop once the quality of images appears sufficient for obtaining near-atomic resolution. In subsequent studies, however, when a better structural preservation and/or resolution is desired, or a different conformational state is explored, the search for improved conditions is broadened and may well lead to favoring another surfactant than that used in the first study. Because surfactants that have given good results in the past are tested first, there is initially a bias in their favor, which does not necessarily reflect an actual superiority, and the use of novel molecules tends to lag behind. A notable exception to this pattern is GDN, which, certainly by virtue of its similarity to digitonin and the advantages it presents over it, seems to have been adopted with remarkable rapidity.

Effect of surfactants on image quality

Many parameters affect the resolution of cryo-EM structures, including the number of particles used for the 3D reconstruction, grid preparation, imaging conditions, etc. A straightforward relationship between the surfactants used and image quality is therefore difficult to establish. However, a few cryo-EM studies have reported duplicate (or, in two cases, triplicate) structures of the same MP in two (or three) distinct amphipathic environments. One can expect that, in each of these studies, where the starting material is the same, all efforts have been made to optimize image quality and that, as a consequence, differences of resolution from one surfactant to the next can be more likely related to the surfactant itself than to any other factor.

Whereas high-CMC detergents are known to degrade the quality of images due to (i) their tendency to destabilize MPs (cf. Chapter 2 in Popot, Reference Popot2018) and (ii) the presence of abundant micelles in the background, which lowers the contrast, resorting to low-CMC detergents tends to improve the resolution. These detergents, such as LMNG, exhibit an extremely slow off-rate, which has been used to develop a gradient-based detergent removal (GraDeR) approach enabling an extensive elimination of free detergent micelles and detergent monomers to further improve image quality (Hauer et al., Reference Hauer, Gerle, Fischer, Oshima, Shinzawa-Itoh, Shimada, Yokoyama, Fujiyoshi and Stark2015). Empty NDs and APol excess can also be removed from the samples, before vitrification, by size exclusion chromatography.

Because it is not known beforehand which amphipathic environment will yield the best data, using in parallel two or more vitrification surfactants, which, a few years ago, was an anecdotal practice, is becoming increasingly frequent. Table 1 shows a comparison of the resolutions achieved for a given MP or MP complex, in a given study, in the presence of various amphipathic environments (the best resolution achieved in a given study is noted in red, the surfactant used indicated on the top line, whereas other data obtained in the same study using an alternative surfactant – reported in the left column – are noted in black). It reveals a clear tendency in favor of MSP-based NDs (12 of the best structures), followed by GDN (6), maltoside-based detergents, MNGs and APols (5 each). An additional benefit of such comparative approaches is that two structures solved at similar resolution in distinct environments may reveal different conformations, which could provide a glimpse into the conformational landscape of the protein. A case in point is mouse TMEM16A, whose structures in LMNG and NDs show what seems to be two distinct closed conformations, featuring either one or two bound Ca2+ ions per monomer (Dang et al., Reference Dang, Feng, Tien, Peters, Bulkley, Lolicato, Zhao, Zuberbühler, Ye, Qi, Chen, Craik, Jan, Minor, Cheng and Jan2017). There are other such examples in the literature, such as, for instance, the cryo-EM structures of the full-length rabbit TRPV2 channel obtained in APols versus MSP-based NDs (Zubcevic et al., Reference Zubcevic, Hsu, Borgnia and Lee2019). This suggests that different amphipathic environments exert different constraints on the transmembrane domain of a given MP, leading to the stabilization of different conformational states. Molecular dynamics data show that APols may slow down MP dynamics (Perlmutter et al., Reference Perlmutter, Popot and Sachs2014). On the one hand, this probably contributes to stabilizing MPs as compared to conventional detergents (Picard et al., Reference Picard, Dahmane, Garrigos, Gauron, Giusti, le Maire, Popot and Champeil2006; Pocanschi et al., Reference Pocanschi, Popot and Kleinschmidt2013); on the other, it may favor low-energy conformational states. This can be seen as an advantage to reduce the conformational heterogeneity of samples, like nanobodies and/or Fabs do. Compared to APols, NDs may restrict transmembrane domain conformational states to a lesser extent. Nevertheless, a tight wrapping of MPs by MSPs has been reported (for examples, see Arkhipova et al., Reference Arkhipova, Guskov and Slotboom2020; Roh et al., Reference Roh, Shekhar, Pintilie, Chipot, Wilkens, Singharoy and Chiu2020), which may potentially give rise to conformational constraints. The presence of lipids in MP/ND or MP/polymer complexes may increase the dynamics of the system, allowing MPs to adopt a range of conformations, which can be relevant to the protein's function.

Table 1. A comparison of resolutions achieved for a given MP or MP complex vitrified in various amphipathic environments

Only the resolutions (in Å) of MP cryo-EM structures published in the same study and for which PDB or EMDB accession codes are available are reported. These reports are referred to in the text and figures as ‘duplicates’. The columns list the surfactants whose use led to the best resolution for the MP considered (in a given study), printed in red, the lines the alternative surfactants used in the same study, the resolution achieved being indicated in black. In four studies, the analysis resulted in indistinguishable 3D reconstructions regardless of the environment and the data were pooled to yield a single structure, in which cases the resolution is printed in green. These four studies and those which resorted to two or more surfactants belonging to the same surfactant family have not been included in the total number of best-resolution structures achieved with each surfactant family (last line).

Note that for duplicate structures obtained using the same surfactant family, the difference of resolution could be attributed to the following reasons: adetergent exchange in one case and not in the other, the best resolution being obtained when the sample was purified and kept in digitonin rather than purified in MNG and transferred to digitonin; btwo versions of the target MP (wild-type versus mutant); cthe vitrification detergent was either DDM or DM, the latter giving the best resolution; dthe lipid compositions of NDs differed; etwo pH values (6.2 and 7.5) were used, the best resolution being obtained at the highest pH; fthe vitrification surfactant was either A8-35 or PMAL-C8, the latter giving the best resolution.

In some cases, the same resolution was achieved in two distinct amphipathic environments: gthe structures of the apo and halo forms of TMEM16 were obtained at different resolutions, namely 3.7 and 3.8 Å for the calcium-free structure in DDM and MSP-based NDs, respectively, and 3.6 Å for the calcium-bound one regardless to the environment; hthe detergent sample was prepared using the GraDeR approach (Hauer et al., Reference Hauer, Gerle, Fischer, Oshima, Shinzawa-Itoh, Shimada, Yokoyama, Fujiyoshi and Stark2015); ithe same resolution (3.8 Å) was reported for the innexin-6 hemichannel in LMNG and NDs; however, the resolution in LMNG can be improved to 3.4 Å by reducing the anisotropy of the reconstruction thanks to the addition in the refinement process of particles from a dataset in which a Fab fragment was bound to the target MP; jthe structures of two conformational states of the metabotropic glutamate receptor (a GPCR) were solved to the same resolution (4 Å), namely the active conformation in GDN and the inactive (apo) form in MSP-based NDs; that of the apo form in GDN could be solved to only 7.9 Å resolution; note that a large population of the receptor in its apo form was observed to be dissociated from its dimeric state into monomeric forms, suggesting detergent-induced destabilization; k‘Others’ in the last column correspond to MNA-C12 (influenza virus hemagglutinin) and Triton-X100 (MS-ring of bacterial flagellum).

In other studies, on the contrary, no significant differences were observed, as is the case of the 3.8 Å resolution structures of the innexin-6 gap junction proteins in an undocked hemichannel observed in either NDs or MNG (Burendei et al., Reference Burendei, Shinozaki, Watanabe, Terada, Tani, Fujiyoshi and Oshima2020), or of the 2.9 Å resolution structures of the human potassium-chloride cotransporter (KCC1) in NDs versus GDN (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Chang, Han, Xu, Zhang, Zhao, Yang, Wang, Li, Delpire, Ye, Bai and Guo2019b). In one case, three cryo-EM structures of the same MP, the autophagy-related 9 protein, were resolved in three different environments, namely MSP-based NDs, APols, and LMNG. Whereas no significant differences were observed between NDs and APols, both surfactants leading to 3.4 Å structures with an r.m.s.d. over all Cα atoms of 0.68 Å, the use of LMNG resulted in a lesser resolution (Maeda et al., Reference Maeda, Yamamoto, Kinch, Garza, Takahashi, Otomo, Grishin, Forli, Mizushima and Otomo2020). In four cases, the absence of differences between distinct amphipathic environments led to merging different datasets to build a single cryo-EM structure (whose resolution is noted in green in Table 1).

Over the years, groups that initially used a particular surfactant to study a given MP or MP complex may move to another one. A case in point is that of mitochondrial respiratory supercomplexes, historically solubilized and purified in digitonin. Different types of supercomplexes have been identified, the biggest one being the respirasome, which results from the association of complexes I1III2IV1, comprising altogether 80 subunits and featuring 132 transmembrane helices. The digitonin/protein ratio used during solubilization considerably affects the types and relative amounts of supercomplexes (Pérez-Pérez et al., Reference Pérez-Pérez, Lobo-Jarne, Milenkovic, Mourier, Bratic, García-Bartolomé, Fernández-Vizarra, Cadenas, Delmiro, García-Consuegra, Arenas, Martín, Larsson and Ugalde2016), pointing to a dissociating effect. The first 3D reconstruction ever achieved of a whole mammalian respirasome, which predated the ‘resolution revolution’ in SP cryo-EM, was obtained by stabilizing the supercomplex in APol A8-35 after extracting it with digitonin. Whereas the resolution of the map was limited to ~19 Å, it made it possible to position the three respiratory complexes with respect to each other within the supramolecular assembly (Althoff et al., Reference Althoff, Mills, Popot and Kühlbrandt2011). Five years later, thanks to progress in cryo-EM technology, four structures of respirasomes from three different organisms were obtained at subnanometer resolution and published nearly simultaneously (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Wu, Guo, Yan, Lei, Gao and Yang2016; Letts et al., Reference Letts, Fiedorczuk and Sazanov2016; Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Mills, Vonck and Kühlbrandt2016; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Gu, Guo, Huang and Yang2016). In one study, it was reported that 42% of the particles had lost complex IV when purified in digitonin, whereas the particles extracted with a DDM analog, PCC-a-M (Hovers et al., Reference Hovers, Potschies, Polidori, Pucci, Raynal, Bonneté, Serrano-Vega, Tate, Picot, Pierre, Popot, Nehmé, Bidet, Mus-Veteau, Bußkamp, Jung, Marx, Timmins and Welte2011), and transferred to A8-35 were homogeneous and stable (Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Mills, Vonck and Kühlbrandt2016). In another study, where digitonin was used both for purification and vitrification, two 3D reconstructions of the ovine respirasome in ‘tight’ and ‘loose’ forms were obtained at resolutions of 5.8 and 6.7 Å, respectively (Letts et al., Reference Letts, Fiedorczuk and Sazanov2016). Over storage, the ratio of the tight to loose respirasomes changed in favor of the loose form, whose population doubled after overnight incubation at 4 °C before grid preparations. In the same study, the authors also presented the cryo-EM structure of supercomplex I1III2 in digitonin at 7.8 Å. More recently, the same authors reported that transferring the digitonin-solubilized supercomplex I1III2 to APol A8-35 preserved all expected enzymatic activities and significantly improved the supercomplex stability over time, leading to cryo-EM structures solved, in four distinct states, at resolutions ranging from 4.6 to 3.8 Å (Letts et al., Reference Letts, Fiedorczuk, Degliesposti, Skehel and Sazanov2019). Nevertheless, replacing digitonin with APol is most likely not the only reason explaining the improvement of resolution, as other parameters such as the number of particles, grid preparation, and imaging conditions may have affected the final resolution of the 3D reconstruction. In addition, one should keep in mind that, despite their lesser dissociating character as compared to detergents, too high an excess of APols can also result in breaking up large MP complexes into subfragments (Popot et al., Reference Popot, Althoff, Bagnard, Banères, Bazzacco, Billon-Denis, Catoire, Champeil, Charvolin, Cocco, Crémel, Dahmane, de la Maza, Ebel, Gabel, Giusti, Gohon, Goormaghtigh, Guittet, Kleinschmidt, Kühlbrandt, Le Bon, Martinez, Picard, Pucci, Sachs, Tribet, van Heijenoort, Wien, Zito and Zoonens2011; Sverzhinsky et al., Reference Sverzhinsky, Qian, Yang, Allaire, Moraes, Ma, Chung, Zoonens, Popot and Coulton2014). This process can be limited by (i) fine-tuning the APol concentration following a rather simple method (for a detailed protocol, see Le Bon et al., Reference Le Bon, Marconnet, Masscheleyn, Popot and Zoonens2018), (ii) using less dissociating APols such as NAPols, and (iii) adding lipids.

Vitrification

The usual approach to vitrification is as follows: the carbon film of a cryo-EM grid is rendered hydrophilic by plasma treatment, the sample is deposited on the grid and incubated in a chamber under controlled humidity and temperature, excess liquid is removed (blotted) by touching the surface of the grid with a filter paper, and the resulting thin supported liquid film is flash-frozen by immersion into a cryogen (typically liquid ethane) (Dobro et al., Reference Dobro, Melanson, Jensen and McDowall2010; Sgro and Costa, Reference Sgro and Costa2018). Blotting is considered one of the critical steps for achieving reproducible ice quality and thickness (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Han, Gomez, Turner, Fletcher and Glaeser2020). Processes that avoid the hard-to-standardize contact with a filter paper are thus being developed. These include self-blotting grids (nano-wire support grids absorbing the excess liquid due to an increased adsorption surface (Razinkov et al., Reference Razinkov, Dandey, Wei, Zhang, Melnekoff, Rice, Wigge, Potter and Carragher2016)), removal of excess liquid by applying a pressure gradient (‘Preassis’; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Xu, Carroni, Lebrette, Wallden, Moe, Matsuoka, Högbom and Zou2019b), microfluidic isolation and controlled deposition of the protein of interest (Schmidli et al., Reference Schmidli, Albiez, Rima, Righetto, Mohammed, Oliva, Kovacik, Stahlberg and Braun2019), or automated deposition of minimal sample volumes, either directly (‘Spotiton’ inkjet dispenser (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Albiez, Bieri, Syntychaki, Adaixo, McLeod, Goldie, Stahlberg and Braun2017); ‘Vitrojet’ pin-printing (Ravelli et al., Reference Ravelli, Nijpels, Henderikx, Weissenberger, Thewessem, Gijsbers, Beulen, López-Iglesias and Peters2020)) or through microfluidic-based (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Fu, Kaledhonkar, Jia, Shah, Jin, Liu, Sun, Chen, Grassucci, Ren, Jiang, Frank and Lin2017) or ultrasound-based (Ashtiani et al., Reference Ashtiani, Venugopal, Belousoff, Spicer, Mak, Neild and de Marco2018) spraying. To our knowledge, no new structure has so far been solved using any of the latter prototypes, despite promising preliminary results. Commercial vitrification devices based on blotting (sold by FEI, Leica, and Gatan) remain overwhelmingly dominant (~95% of the studies). Including home-made devices, more than 97% of the sample preparation is performed with a paper-based blotting step (the missing 3% reflecting a lack of information rather than blotting alternatives). This might be attributable to a lack of visibility/availability of newly developed prototypes, or to still ongoing proof-of-concept studies. A point to keep in mind is that, at the blotting stage, most of the surfactant adsorbed at the air/water interface will be removed. The rate of reformation of a surfactant monolayer will depend on the nature and concentration of the surfactant, which may affect such factors as thinning of the film and MP adsorption at the interface.

Can surfactants be used as vitrification helpers?

The preparation of high-quality cryo-EM grids depends on being able to preserve the target macromolecule in a vitreous thin film, with the particles exhibiting an even distribution and, ideally, adopting random orientations within the ice layer. The key to achieving high resolution is a careful optimization of cryo-specimen preparation (Sgro and Costa, Reference Sgro and Costa2018). For MP samples, the presence of surfactant represents a critical factor. Several types of difficulties have been identified, including uneven dispersion of MPs throughout the ice film (aggregation at the edge of the holes in carbon films, particularly if the ice film is too thin, and/or preferential orientations) and lowering of the contrast due to the presence of detergent micelles in the background. The latter problem has encouraged the use of APols, NDs or low-CMC detergents to minimize the presence of free surfactant. MP dispersion within the ice film constitutes the most difficult parameter to control (Drulyte et al., Reference Drulyte, Johnson, Hesketh, Hurdiss, Scarff, Porav, Ranson, Muench and Thompson2018). Commercial cryo-EM grids are metal mesh grids, typically copper, with a support film of amorphous carbon layered over the top, which can be either continuous or perforated. Amorphous carbon support films remain the preferred cryo-EM support material because it is relatively inexpensive. However, it is prone to bending and deformation as a result of exposure to the electron beam (Brilot et al., Reference Brilot, Chen, Cheng, Pan, Harrison, Potter, Carragher, Henderson and Grigorieff2012), entailing afterwards a correction of beam-induced movements. All-gold cryo-EM grids, which have been shown to significantly reduce specimen motion during illumination with the electron beam (Russo and Passmore, Reference Russo and Passmore2014), are now more frequently tested. Chemical modification of gold-coated grids with a thiol bearing a PEG group has been developed as a mean to reduce the aggregation of soluble proteins on the support and at the edges of the holes (Meyerson et al., Reference Meyerson, Rao, Kumar, Chittori, Banerjee, Pierson, Mayer and Subramaniam2014), an approach that has also been shown to improve the distribution and orientations of MPs (Blaza et al., Reference Blaza, Vinothkumar and Hirst2018). Another approach is the chemical modification of the MP itself by reacting its surface-exposed lysines with an appropriately functionalized low-molecular-mass PEG (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Cabanos and Rapoport2019; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Siggel, Ovchinnikov, Mi, Svetlov, Nudler, Liao, Hummer and Rapoport2020). Obtaining thicker films can alleviate the orientation problem and it seems that APols can help (Flötenmeyer et al., Reference Flötenmeyer, Weiss, Tribet, Popot and Leonard2007). An additional risk, which affects both MPs and soluble proteins, is protein adsorption at the air/water interface, which generally results in partial or complete denaturation (Noble et al., Reference Noble, Dandey, Wei, Brasch, Chase, Acharya, Tan, Zhang, Kim, Scapin, Rapp, Eng, Rice, Cheng, Negro, Shapiro, Kwong, Jeruzalmi, des Georges, Potter and Carragher2018). Immobilizing proteins on a graphene-coated surface is a way to prevent this adsorption, as shown with soluble proteins (D'Imprima et al., Reference D'Imprima, Floris, Joppe, Sánchez, Grininger and Kühlbrandt2019). Binding of megabodies has also been reported to randomize the particle distribution in ice for MPs that normally exhibit preferential orientations (Uchański et al., Reference Uchański, Masiulis, Fischer, Kalichuk, López-Sánchez, Zarkadas, Weckener, Sente, Ward, Wohlkönig, Zögg, Remaut, Naismith, Nury, Vranken, Aricescu, Pardon and Steyaert2021).

Surfactant molecules adsorb at the air/water interface, which has two interesting consequences: on the one hand, this reduces the surface tension of the buffer and likely influences the thinning kinetics; on the other, it creates a barrier that limits protein adsorption and denaturation at the interface (Glaeser et al., Reference Glaeser, Han, Csencsits, Killilea, Pulk and Cate2016; Glaeser and Han, Reference Glaeser and Han2017). The first effect adds to the complexity of grid preparation because the rate at which the film drains, its thickness at the time of vitrification and, as a result, the even or uneven distribution and orientation of MPs can be difficult to control. It is, however, a factor that can be harnessed to improve particle distribution (cf. Flötenmeyer et al., Reference Flötenmeyer, Weiss, Tribet, Popot and Leonard2007).

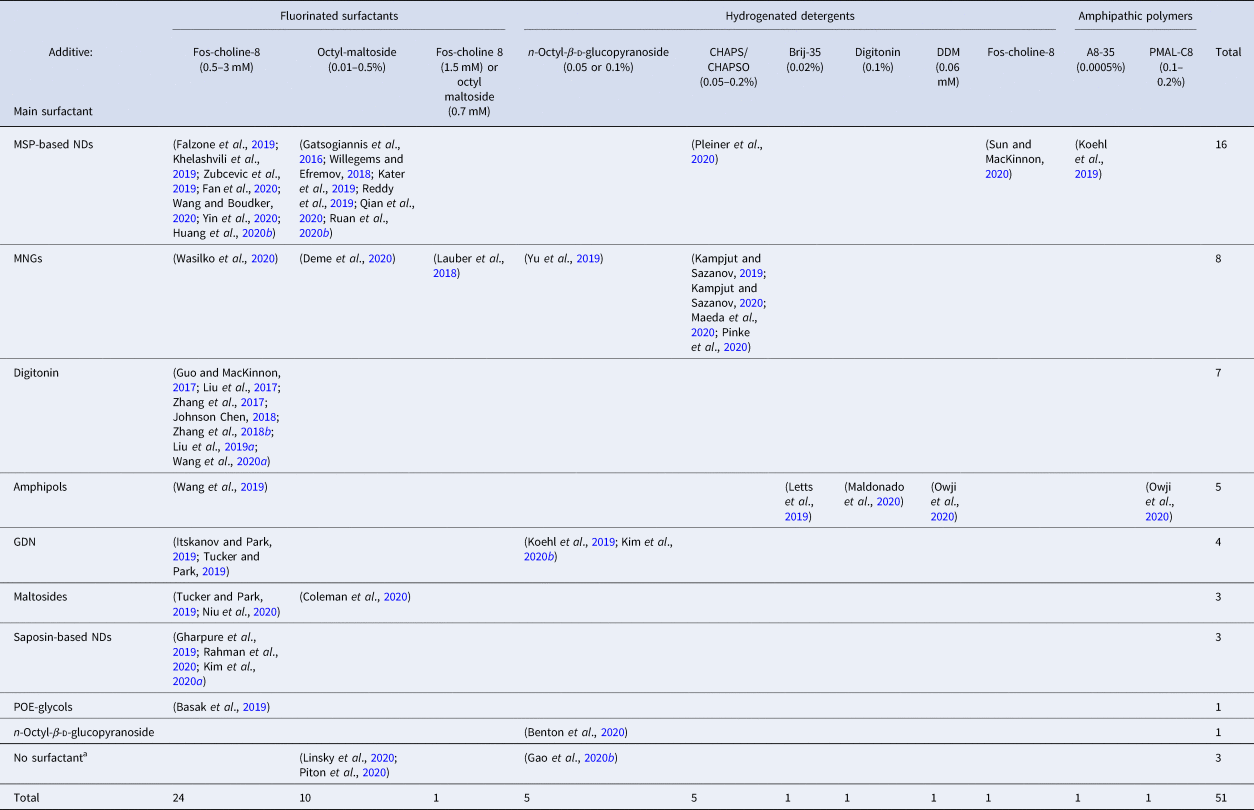

It has been reported that the addition of small amounts of surfactants to a sample of soluble proteins can improve particle distribution and/or orientation within the ice film, which facilitates collecting the various views required for 3D reconstruction. This improvement has been observed for instance with detergents such as CHAPSO (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Noble, Kang and Darst2019) as well as with APol A8-35 (Chowdhury et al., Reference Chowdhury, Ketcham, Schroer and Lander2015; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Konermann, Brideau, Lotfy, Wu, Novick, Strutzenberg, Griffin, Hsu and Lyumkis2018a). Table 2 lists the cases where a secondary surfactant has been added to solubilized MP samples in order to improve the quality of the samples. NDs and MNGs are the two systems in which the addition of extra surfactants has been most often resorted to (Table 2).

Table 2. Studies in which the addition of secondary surfactants to solubilized MP samples has been carried out before vitrification

a No surfactant has been used for the purification of SARS-CoV-2S ectodomain (residues16–1206) (Linsky et al., Reference Linsky, Vergara, Codina, Nelson, Walker, Su, Barnes, Hsiang, Esser-Nobis, Yu, Reneer, Hou, Priya, Mitsumoto, Pong, Lau, Mason, Chen, Chen, Berrocal, Peng, Clairmont, Castellanos, Lin, Josephson-Day, Baric, Fuller, Walkey, Ross, Swanson, Bjorkman, Gale, Blancas-Mejia, Yen and Silva2020), the mycobacterial EspB heptamer, which appears as an external membrane protein (Piton et al., Reference Piton, Pojer, Wakatsuki, Gati and Cole2020), and the visual G protein-effector complex, a peripherally attached complex to the rod photoreceptor outer segment membranes (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Eskici, Ramachandran, Poitevin, Seven, Panova, Skiniotis and Cerione2020b).

Fluorinated surfactants have proven particularly useful for this task because (i) they mix poorly with hydrogenated alkyl chains of detergent molecules and (ii) they are strongly attracted to the air/water interface, where they oppose the adsorption of hydrogenated molecules (cf. Chapter 3 in ref. Popot (Reference Popot2018)). Fluorinated Fos-choline 8, with a CMC of 2.5 mM, is most frequently used, followed by fluorinated octylmaltoside (CMC = 0.7 mM). MP cryo-EM structures have also been obtained using as additives hydrogenated detergents, such as Fos-choline 8, DDM, digitonin, CHAPS/CHAPSO, Brij-35, or octylglucoside (Table 2). An interesting observation is that A8-35 can also facilitate sample vitrification for ND-trapped MPs (Koehl et al., Reference Koehl, Hu, Feng, Sun, Zhang, Robertson, Chu, Kobilka, Laeremans, Steyaert, Tarrasch, Dutta, Fonseca, Weis, Mathiesen, Skiniotis and Kobilka2019). As with small surfactants, the addition of A8-35 seems to oppose the adsorption of MP/ND complexes at the air/water interface, most likely due to its forming an interfacial film (cf. Giusti et al., Reference Giusti, Popot and Tribet2012).

Preferential orientation has been reported in the case of the ryanodine receptor RyR1 trapped in A8-35 (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Fan and Serysheva2015). Random orientation of the particles was achieved following addition to the sample of a low concentration of octylglucoside (one-tenth of the CMC). The mechanism underlying this effect is not clear (for a discussion, see Chapter 12 in Popot, Reference Popot2018). Combining two or more surfactants can thus have favorable effects, although it complicates optimizing grid preparation.

Using functionalized APols for immobilizing MP complexes or labelling transmembrane domains