Introduction

Bulimia nervosa (BN) is an eating disorder with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 1–3% (Trace et al., Reference Trace2012; Smink et al., Reference Smink, Van Hoeken and Hoek2013; Stice et al., Reference Stice, Marti and Rohde2013). It is characterised by recurrent binge eating, extreme weight-control behaviour, and an overconcern about body shape and weight (Cooper and Fairburn, Reference Cooper and Fairburn1993; Fairburn and Harrison, Reference Fairburn and Harrison2003) and generally starts in late adolescence or early adulthood. Although it usually begins with strict dieting and some weight loss, this dietary restriction becomes punctuated after some months or years by repeated binges and weight regain. In most cases, people with BN engage in purging and compensatory behaviours that include the use of excessive exercise and/or dietary restriction.

Cognitive behavioural therapy specific to eating disorders (CBT-ED) has been demonstrated to be an effective approach for the treatment of BN (Hay, Reference Hay2013; Poulsen et al., Reference Poulsen2014; Fairburn et al., Reference Fairburn2015; Linardon et al., Reference Linardon2017). Some evidence suggests that interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) can achieve results similar to CBT, although it is much slower to achieve these effects (Fairburn et al., Reference Fairburn1993; Agras et al., Reference Agras2000). The more recent ‘enhanced’ form of CBT appears to be more effective than IPT even at follow-up (Fairburn et al., Reference Fairburn2015). There is also evidence that supports the use of guided cognitive behavioural self-help (Bailer et al., Reference Bailer2004; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner2013). There are many more treatments for BN, although data on their outcomes are limited to date.

Traditional pairwise meta-analyses of RCTs are used to synthesise the results of different trials comparing the same pair of treatments, to obtain an overall estimate of the effect of one treatment relative to another. However, the few extant meta-analyses of treatments for people with BN have been limited to comparisons of a narrow range of treatments (Whittal et al., Reference Whittal, Agras and Gould2000; Thompson-Brenner et al., Reference Thompson-Brenner, Glass and Westen2003; Hay, Reference Hay2013; Polnay et al., Reference Polnay2014; Linardon et al., Reference Linardon2017). Network meta-analysis (NMA) has advantages over standard pairwise meta-analysis in that (1) all the treatments that have been tested in RCTs can be simultaneously compared with each other in one analysis; and (2) their effects can be estimated relative to each other and to a common reference condition (such as a wait list). Estimates of the relative effects of pairs of treatments that have often, rarely, or never been directly compared in an RCT can be calculated. Consequently, an NMA overcomes some of the limitations of a traditional meta-analysis in which conclusions are largely restricted to comparisons between treatments that have been directly compared in RCTs (Dias et al., Reference Dias2013).

An NMA was developed and conducted of all psychological, pharmacological, and combination therapies that are used for the treatment of adult BN, and which have been tested in RCTs. This NMA was used to inform the new national clinical guidance for eating disorders in England released by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2017). The guideline was developed by a Guideline Committee, an independent multi-disciplinary team consisting of clinical academics, health professionals and service users and carer representatives with expertise and experience in the field of eating disorders. This paper reports the findings of the NMA that was conducted to inform the NICE guideline on the most effective treatments for BN in adults.

Methods

Search strategy

A search for published and unpublished studies on the treatment of adults with eating disorders was conducted in the databases Embase, Medline, PsycINFO, and Central to inform the NICE guideline. All databases were searched from their inception to July 2016 and no language limits were set. The strategy used terms covering all eating disorders, in accordance with the NICE guideline scope. The balance between sensitivity (the power to identify all studies on a particular topic) and specificity (the ability to exclude irrelevant studies from the results) was carefully considered, and a decision was made to utilise a broad, population-based approach to the search in order to maximise retrieval in a wide range of areas. To aid retrieval of relevant and sound studies, ‘filters’ were used (where appropriate) to limit the search results to RCTs. See Online Supplementary Appendix 1 for full details of the search terms used.

Selection criteria

A systematic review of interventions for BN was carried out according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., Reference Moher2009).

The titles and abstracts of identified studies were screened by two reviewers against inclusion criteria specified in the guideline review protocols, until a good inter-rater reliability was observed (percentage agreement ⩾90%, or Kappa statistic K > 0.60) (NICE, 2017). Any disagreements between raters were resolved through discussion. Once full versions of the selected studies were acquired for assessment, full studies were checked independently by two reviewers, with any differences being resolved with discussion. Data were extracted on the study characteristics, aspects of the methodological quality, outcome data, and risk of bias.

RCTs for the systematic review of treatments for BN were included if they reported on treatments for people aged at least 18 years who fulfilled diagnostic criteria for BN (i.e. DSM-IV). Two reviewers independently assessed eligibility: studies were included if they were RCTs examining psychological, pharmacological, or combination therapies compared with a wait list, pill placebo, or another active treatment. Nutritional management was not considered in the review as this was seen as an add on to treatments for people with BN. Also, only treatments available and licensed in the UK for BN were included.

According to the NICE Guideline Committee's expert view, it was important to differentiate between CBT-ED and generic CBT. CBT-ED is the leading form of treatment for BN that places emphasis on the eating disorder psychopathology and may have some differences in efficacy when compared with CBT non-specific to eating disorders. It was also considered important to distinguish between group and individual treatments, and between pure and guided cognitive behavioural self-help because there may be some differences in efficacy and also on cost effectiveness, which is an important factor when making recommendations for NICE guidelines.

Network meta-analysis

To take all trial information into consideration, network meta-analytic techniques (mixed treatment comparisons) were employed to synthesise evidence. The critical outcomes in the systematic review conducted for the NICE guideline were remission, long-term recovery, and binge eating. The guideline systematic review of the clinical literature identified only one dichotomous outcome that could be utilised in the NMA – full remission at the end of treatment – as the reporting of the other outcome measures was inconsistent across the trials. The NMA was also used to inform a cost-effectiveness analysis and the Guideline Committee was of the view that full remission at the end of treatment was an important outcome to pursue in the economic evaluation.

The identified RCTs employed a range of definitions of full remission, utilising criteria such as abstinence from binge eating and purging. Following consultation with the NICE Guideline Committee, RCTs were included only if they defined full remission as either the abstinence of bulimia-related symptoms over a minimum of a 2-week period, or as no longer meeting DSM-IV criteria for BN (including cognitive elements). The definition of remission was decided before selection of studies. A number of excluded studies employed shorter time frames or lesser symptom reduction. However, stricter criteria for defining full remission were used because the fluctuating nature of symptom severity and gaps between behaviours in BN mean that a shorter time period would not be clinically meaningful. In studies where the time frame for remission was unclear, the Guideline Committee was consulted to decide whether the study should be included in the review.

A network of treatments included in the systematic review, for which data on full remission at the end of treatment were available, was designed. Only treatments that were connected to the network were considered. Treatment-as-usual arms were excluded, since the definitions of ‘treatment-as-usual’ varied across the studies and were therefore not informative to the Guideline Committee. Head-to-head comparisons of no interest (such as interventions not available or licensed for BN in the UK, as well as controls of no interest) were excluded from the analysis unless they allowed indirect comparisons between interventions of interest (see online Supplementary Appendix 2 for details of the included studies in the NMA). An intention to treat (ITT) analysis was adopted when estimating full remission (that is, all randomised patients were included and anyone discontinuing treatment, for whatever reason, was assumed not to be in remission). The flowchart diagram for the NMA is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart.

The Committee made an a apriori assumption that there would need to be at least 200 people randomised to a treatment across all included trials in the NMA for them to make a recommendation with confidence.

Statistical analysis

Both fixed effects and random effects models (Binomial Likelihood and Logit link) were run (see the online Supplementary Appendix 3 and 4 for WinBUGS fixed effects and random effects model codes, respectively) (Dias et al., Reference Dias2011a). The goodness-of-fit of each model to the data was measured by comparing the posterior mean of the summed deviance contributions to the number of data points (Dempster, Reference Dempster1997). The Deviance Information Criterion (DIC), which is equal to the sum of the posterior mean of the residual deviance and the effective number of parameters, was used as the basis for model comparison (Spiegelhalter et al., Reference Spiegelhalter2002). Model selection was also influenced by the posterior mean between study heterogeneity standard deviation (s.d). Analyses were undertaken in a Bayesian framework, using WinBUGS 4.1.3 (Lunn et al., Reference Lunn2013).

Relative effects are reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% credible intervals (CrI). Treatments were also ranked based on their effectiveness, with lower ranks indicating more effective treatments. Median ranks and 95% CrI are presented for each treatment.

Continuity correction

In the dataset, several studies reported zero events of interest in some arms (that is, the number of people achieving full remission was zero). Combining such data can be problematic: when zero events occur in some arms of a study, the log-OR becomes undefined (as does the variance), which causes problems in the analysis and precludes the estimation of relative effects. As a result, continuity corrections are needed. Using a continuity correction for studies with zero counts allows the log-OR to be estimated, and hence allows synthesis via standard NMA methods. There are many possible continuity correction methods (Sweeting et al., Reference Sweeting2004). In the present study, a continuity correction of 0.5 was added to both the number of events and the number of non-events across all study arms, in studies in which one or more (but not all) arms had zero events.

Inconsistency checks

A basic assumption of an NMA is that direct and indirect evidence estimate the same parameter. That is, the relative effect between A and B measured directly from an A v. B trial is the same as the relative effect between A and B estimated indirectly from A v. C and B v. C trials. Inconsistency arises when there is a conflict between direct evidence (from an A v. B trial) and indirect evidence (gained from A v. C and B v. C trials). This consistency assumption has also been termed the similarity or transitivity assumption (Mavridis et al., Reference Mavridis2015).

Evidence of inconsistency was checked for by comparing the standard network consistency model to an ‘inconsistency’, or unrelated mean effects, model (Dias et al., Reference Dias2013). The latter is equivalent to having separate, unrelated meta-analyses for every pair-wise contrast but with a common variance parameter in random effects models. Improvement in model fit or a substantial reduction in heterogeneity in the inconsistency model compared with the NMA consistency model, indicates evidence of inconsistency. The WinBUGS code for the inconsistency model is provided in the online Supplementary Appendix 5 (Dias et al., Reference Dias2011b).

Results

Identified studies and treatments

Seventy-five potentially eligible studies were identified, 54 of which were excluded (Fig. 1). Twenty-one trials with 1828 participants provided direct or indirect evidence on full remission associated with 12 treatment options: wait list, individual CBT-ED, individual IPT, guided cognitive behavioural self-help, individual behaviour therapy (BT), pure cognitive behavioural self-help (i.e. self-help with no support), group CBT-ED group, fluoxetine, relaxation, individual CBT-ED plus fluoxetine, group BT, and supportive psychotherapy. Among the 21 trials there were six studies (N = 452) comparing the same treatment in both arms (e.g. CBT-ED v. CBT-ED, etc.). Nevertheless, these were retained in the NMA as they contributed to the estimation of between-study heterogeneity. The resulting network of trials contributing data to the NMA is presented in Fig. 2. (Full details of the excluded studies are provided in the online Supplementary Appendix 6 and the final data file used in the NMA is shown in online Supplementary Appendix 7.)

Fig. 2. Network diagram of studies included in analysis of bulimia nervosa treatments. Note: The width of the lines is proportional to the number of trials directly comparing each pair of treatments. The size of each node is proportional to the number of randomised participants to each intervention (sample size). CrI, credible Interval; BT, behaviour therapy; CBT-ED, cognitive behavioural therapy specific to eating disorders; IPT, interpersonal psychotherapy

Risk of bias assessment

All included trials were assessed for risk of bias using the GRADE risk of bias tool (Balshem et al., Reference Balshem, Helfand and Schunemann2011; Guyatt et al., Reference Guyatt2011). Sequence generation and allocation concealment were adequately described in eleven and three trials, respectively. Trials were regarded at high risk of bias for lack of participant and provider masking. In four studies, assessors were aware of treatment assignment, and in four trials it was unclear if the assessors were blinded. Attrition was high in most trials. However, we used ITT analysis and treated drop outs as failures. As a result, attrition bias was not considered in the assessment. Included trials reported a variety of outcomes. Only two trials were registered on a trials database. Consequently, most studies were judged as being at unclear risk of reporting bias. No other potential biases were identified. (Risk of bias tables are presented in the online Supplementary Appendix 8.)

NMA model fit statistics

Convergence was satisfactory after at least 70 000 iterations. Models were then run for a further 70 000 iterations on two separate chains, and results are based on this further sample. The fixed and random effects models had a similar fit to the data when comparing the posterior mean residual deviance and DIC values. Moderate to high between-trials heterogeneity was observed when a random effects model was used (τ = 0.43, 95% CrI 0.04–0.93), which was of a similar magnitude to the relative effects expressed on the log- OR scale (see online Supplementary Appendix 9). No substantial differences were observed in posterior mean residual deviance or DIC values compared with the inconsistency model, which suggests no inconsistency. Model fit statistics for the fixed and random-effects models, continuity corrected, and for the random-effects inconsistency model are provided in online Supplementary Appendix 10. The random effects model had a slightly more favourable fit than the fixed effects, therefore all further analyses are based on that model.

Treatment outcomes

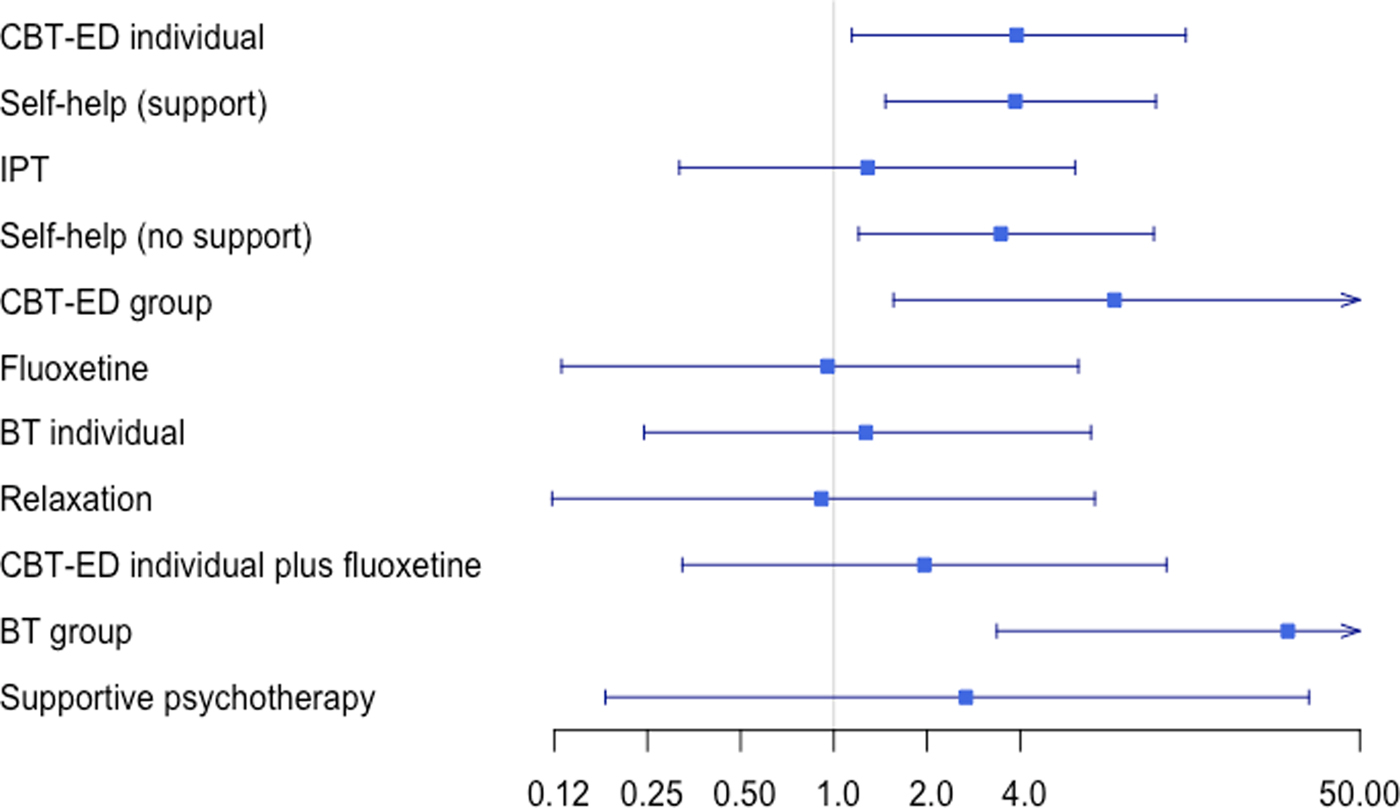

The posterior median OR and 95% CrI for each treatment for achieving full remission at the end of treatment compared with every other treatment are reported in Table 1. Compared with wait list, individual CBT-ED (OR 3.89, 95% CrI 1.19–14.02), guided cognitive behavioural self-help (OR 3.81, 95% CrI 1.51–10.90), pure cognitive behavioural self-help (OR 3.49, 95% CrI 1.20–11.21), group CBT-ED (OR 7.67, 95% CrI 1.51–55.66), and group BT (OR 28.70, 95% CrI 3.11–455.3) were significantly better at achieving full remission at the end of treatment. Group BT was also better than IPT, fluoxetine, individual BT, and relaxation. However, as indicated by the very wide 95% CrI, there was high uncertainty regarding the treatment effects of group BT and group CBT-ED. These therapies had very small numbers randomised across all studies and, as a result, their effects were very uncertain. Although there were differences in the mean effects between any other treatments, these were not statistically significant. The posterior median log OR (LOR) and 95% CrI for each treatment compared with every other for achieving full remission at the end of treatment as estimated by the NMA (and, where available, the respective results from the pairwise analysis) are provided in online Supplementary Appendix 9. The NMA and pairwise results were in agreement in all cases, which strengthens the results of the NMA.

Table 1. Median odds ratios and 95% CrI for every individual treatment compared with every other. (Lower triangle presents the results of the network meta-analysis and the upper triangle the results of available direct pair-wise comparisons)

CrI, credible interval; BT, behaviour therapy; CBT-ED, cognitive behavioural therapy specific to eating disorders; IPT, interpersonal psychotherapy.

Figure 3 shows the ORs (on a log-scale) in remission compared with wait list. Most of the treatments had very wide CrI and crossed the line of no effect. Most CrI also overlapped, indicating no difference between the treatments.

Fig. 3. Mean odds ratios on a log scale.

Treatment rankings

The treatments with the lowest posterior median rank were group BT (1st, 95% CrI 1st to 5th), followed by group CBT-ED (3rd, 95% CrI 1st to 9th), individual CBT-ED (4th, 95% CrI 2nd to 7th), and guided cognitive behavioural self-help (5th, 95% CrI 2nd to 8th). Table 2 shows the posterior median ranks and the associated 95% CrI.

Table 2. Posterior median rank and 95% CrI. (The lower the rank the better the treatment)

CrI, credible Interval; BT, behaviour therapy; CBT-ED, cognitive behavioural therapy specific to eating disorders; IPT, interpersonal psychotherapy.

The full results of the NMA are provided in online Supplementary Appendix 11.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first reported NMA in people with BN. Only one previous NMA in people with eating disorders was identified, examining the effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological interventions for binge-eating disorder (Peat et al., Reference Peat2017). Overall, the results of the present NMA suggest that group BT, group CBT-ED, individual CBT-ED and guided cognitive behavioural self-help are more effective than other treatments in achieving full remission at the end of treatment. The findings for group BT and group CBT-ED were based on very small numbers randomised (N < 70), and were characterised by very wide CrI. Similarly, the evidence for other treatments, with the exception of IPT, was limited. However, the mean effects for these treatments suggest a less good outcome when compared with cognitive or behavioural therapies. As a result, individual CBT-ED and guided cognitive behavioural self-help are the treatments for which there is the most reliable evidence. Also, the inconsistency checks did not identify any significant inconsistency between the direct and indirect evidence included in the NMA, which strengthens the conclusions of the analysis.

Not all trials identified in the systematic review provided data on full remission. ‘Full remission’ was not clearly defined in some RCTs, and there was wide variation in its definition when it was reported. In particular, a number of RCTs were excluded because remission was defined as abstinence from bulimia-related symptoms over a period of less than 2 weeks. According to the NICE Guideline Committee's expert opinion only abstinence from bingeing over and above 2 weeks should be considered. Although this 2-week period was seen as a relatively weak definition, more stringent inclusion criteria would have excluded the majority of studies since only few of them had longer reported periods.

It is acknowledged that not meeting full DSM-IV criteria is not the same as abstinence from binge eating and compensatory behaviours, and it could potentially include people in partial remission. However, given a limited evidence base the committee made a decision to include such studies. Use of the DSM-V criteria would have been more inclusive but DSM-IV criteria was still in operation when nearly all of the studies were conducted.

It should also be noted that papers used inconsistent definitions of behaviour change. Future research needs to adopt consistent and rigorous definitions. It is proposed that ‘abstinence’ be defined as (1) no objective binges or purging behaviours over the previous 3 months and (2) being not underweight. Similarly, ‘full remission’ should be defined as abstinence, plus attitudes towards eating, weight and shape within one standard deviation of the community range for the relevant population.

The ITT analysis meant that all participants were analysed in the group to which they had been randomised and all study non-completers were assumed to not be in remission. This strategy was supported by the NICE guideline committee and provides a conservative estimate of treatment effects.

It was not possible to investigate whether the end of treatment effects persisted or diminished in the long term because most trials stopped at the end of treatment (usually at 16 weeks). Hence, there was insufficient evidence to inform an NMA using remission data at long-term follow-up. Also, even though we included only those treatments available and licensed for use in the UK, only one trial was excluded on the grounds of being of no interest (Pope et al. Reference Pope1989, which compared trazodone with pill placebo). The findings should therefore be of interest to an international audience.

One limitation of the study is that the literature search is over a year old. However, a literature search on PubMed (conducted March 2018) failed to identify any relevant new RCTs.

The finding that, among the treatments with a robust evidence base, individual CBT-ED appears to be the most effective option to achieve remission at the end of treatment for people with BN is in line with other systematic reviews (Shapiro et al., Reference Shapiro2007; Hay, Reference Hay2013; Polnay et al., Reference Polnay2014; Linardon et al., Reference Linardon2017). Our analysis suggests that guided cognitive behavioural self-help is also effective. This outcome is also consistent with the findings of systematic reviews by Beintner et al. (Reference Beintner, Jacobi and Schmidt2014) and Linardon et al. (Reference Linardon2017), which showed that cognitive behavioural self-help treatments are useful in the treatment of BN (especially if the features of their delivery and indications are considered carefully).

A review by Polnay et al. (Reference Polnay2014) suggested that group CBT was effective compared with no treatment. However, there was insufficient evidence in their review on the effectiveness of group CBT relative to individual CBT. Our use of mixed treatment methodology enabled us to compare group therapies with other available treatment options. Although group CBT-ED and group BT were effective in achieving remission at the end of treatment, the estimates of effect were extremely uncertain. Similarly, even though combination therapies (e.g. CBT plus fluoxetine) and other psychological therapies (including individual IPT and individual BT) have shown some efficacy in individual studies, our synthesis pooled evidence using direct and indirect comparisons and found their effects small compared with other available treatments.

The present analysis found no convincing evidence for the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments although few studies provided direct comparisons between psychological therapies and pharmacological treatments.

Taking all these factors into account, the NICE guideline recommended that bulimia-nervosa-focused guided self-help should be offered as the first treatment for adults with BN in a stepped care treatment strategy, with the second step being individual CBT-ED (NICE, 2017).

Overall the evidence base was limited, in particular for a range of treatments. There is a clear need for well-conducted head-to-head studies that examine the effectiveness of pharmacological, individual as well as group psychological, and combined pharmacological and psychological therapies compared with each other for adults with BN. In particular, long-term comparative outcome data are needed.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718001071.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Guideline Committee for the NICE guideline on ‘Eating disorders: recognition and treatment’ (Anthony Bateman, Jane Dalgliesh, Ivan Eisler, Christopher Fairburn, Lee Hudson, Mike Hunter, Dasha Nicholls, Jessica Parker, Daniel Perry, Ursula Philpot, Susan Ringwood, Mandy Scott, Lucy Serpell, Phillip Taylor, Dominique Thompson, Janet Treasure, Hannah Turner, Christine Vize, and Glenn Waller). We also thank Nick Harris and Barry Johnston for editorial input. This work was initiated by the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCC-MH) and continued by the National Guideline Alliance (NGA) at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) from 1 April 2016. NCC-MH and NGA received funding from NICE to develop clinical and social care guidelines. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the RCOG, NGA, NCC-MH or NICE. ‘National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017) Eating disorders: recognition and treatment. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69’. The funder of the study had no further role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Author Contributions

EK contributed to the NMA analyses, conducted inconsistency checks. ES carried out the NMA and the associated analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. IM contributed to the study conception, planning, and NMA analyses. LF contributed to carrying out the systematic reviews, data extraction, proof reading, and copy editing. LSa contributed to carrying out the systematic reviews, and data extraction. SD contributed to the NMA analyses, and conducted inconsistency checks. ST performed search strategy. TK contributed to the study conception and interpretation of the results. CGF, GW, HT, and LSe provided clinical input and interpretation of the results and their clinical implications. All authors contributed to the write up of the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Declaration of interests

ES, IM, LF, LSa, ST, and TK received support from the NGA, which was in receipt of funding from NICE for the submitted work. SD and EK received support from the NICE Guidelines Technical Support Unit, University of Bristol, with funding from the Centre for Guidelines (NICE). The funder had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. CGF is the author of research papers, review articles, and books that have commented on the effectiveness of various treatments for eating disorders (including BN). Royalties received from publishers of the books concerned. CGF held (paid and unpaid) training workshops for clinicians on eating disorders; on eating disorder treatment in general; and on specific treatments for eating disorders (CBT; IPT; guided self-help). CGF is involved in developing an online means of training therapists in a specific treatment for eating disorders, including CBT. CGF is supported by a Principal Fellowship from the Wellcome Trust (046 386). LSr has no declarations of conflict of interest. HT is teaching and conducting research/publications in CBT. She is also involved in the development and evaluation of brief CBT interventions for eating disorders and in an effectiveness study of CBT when delivered in routine clinical settings. GW published books and a range of papers and book chapters on CBT for eating disorders; regularly gives workshops on evidence-based CBT for eating disorders.