Introduction

Bipolar disorder is characterized by abrupt and unpredictable shifts between states of depression and (hypo)mania (APA, 1994) and carries high personal and economic costs for affected individuals and their families. The development of effective therapies requires investigation of the underlying psychological and neurobiological mechanisms involved in different phases of the disorder. One important target of psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), has been self-referential thinking processes (Scott & Pope, Reference Scott and Pope2003).

Studies have identified several abnormalities in self-referential cognition in bipolar disorder, with marked similarities to unipolar depression (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Stanton, Garland and Ferrier2000), including increased rumination (Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Knowles, Tai and Bentall2007), an implicit pessimistic attributional style (Lyon et al. Reference Lyon, Startup and Bentall1999), low self-esteem (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Scott, Haque, Gordon-Smith, Heron, Caesar, Cooper, Forty, Hyde, Lyon, Greening, Sham, Farmer, McGuffin, Jones and Craddock2005) and dysfunctional attitudes towards the self (Scott & Pope, Reference Scott and Pope2003). Van der Gucht et al. (Reference Van der Gucht, Morriss, Lancaster, Kinderman and Bentall2009) found that a negative cognitive style, characterized by sociotropy, autonomy, behavioral inhibition and rumination, was more evident during depressive than during other types of bipolar episode but that this style was still evident in euthymic patients, even after current symptoms were controlled for statistically. In contrast to those with unipolar depression, individuals with bipolar disorder have been characterized as having concerns with perfectionism, autonomy and self-criticism (Alloy et al. Reference Alloy, Abramson, Walshaw and Neeren2006), more complex patterns of self-esteem that depend upon phase of illness (Scott & Pope, Reference Scott and Pope2003) and pronounced short-term fluctuations in mood and self-esteem (Knowles et al. Reference Knowles, Tai, Jones, Highfield, Morriss and Bentall2007), along with an increased need for social approval (Pardoen et al. Reference Pardoen, Bauwens, Tracy, Martin and Mendlewicz1993).

Another line of research has focused on psychological mechanisms specific to mania, such as behavioral activation and increased sensitivity to reward (Depue & Iacono, Reference Depue and Iacono1989) triggered by goal-attainment events (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Sandow, Meyer, Winters, Miller, Solomon and Keitner2000b), risk taking (Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Knowles, Tai and Bentall2007; Van der Gucht et al. Reference Van der Gucht, Morriss, Lancaster, Kinderman and Bentall2009), and also higher-level cognitive appraisals relating to goal pursuit (Mansell & Pedley, Reference Mansell and Pedley2008). In Van der Gucht et al.'s (Reference Van der Gucht, Morriss, Lancaster, Kinderman and Bentall2009) study, these processes were specific to manic episodes. However, Mansell & Morrison (Reference Mansell and Morrison2007) reported that higher-level appraisals relating to goal pursuit (which were not measured in the Van der Gucht study) were evident in euthymic patients and predicted the future development of mania.

An important complication in examining psychological processes in bipolar disorder concerns the possibility that depression and mania are not simply polar opposites, and that both can be present in an individual at the same time (Dilsaver et al. Reference Dilsaver, Chen, Shoaib and Swann1999; Sato et al. Reference Sato, Bottlender, Klenidienst and Moller2005). In a longitudinal analysis of symptoms of patients studied for about a year, we found that there was a small but statistically significant positive correlation between depressive and manic symptoms, but that they nonetheless fluctuated fairly independently over time (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Morriss, Scott, Paykel, Kinderman, Kolamunnage-Dona and Bentall2011).

It follows that the longitudinal relationships between symptoms of mania and depression must be taken into account when considering self-referential and other psychological processes in bipolar disorder. The aim of this study was therefore to extend our previous work (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Morriss, Scott, Paykel, Kinderman, Kolamunnage-Dona and Bentall2011) by examining relationships between specific thinking processes related to the self-concept (namely, self-esteem, externalizing bias, dysfunctional attitudes and self-discrepancies; that is constructs that are likely to be related to each other) and specific symptoms (mania, depression), while taking into account the co-morbidity between the symptoms. In addition to investigating these processes in a cross-sectional design, we examined them longitudinally.

Method

Participants

Data were obtained from 253 individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder according to DSM-IV (APA, 1994), recruited for a multicenter randomized controlled trial of adjunctive CBT for bipolar disorder. Recruitment was conducted at five National Health Service (NHS) sites in the UK, namely Cambridge, Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester and Preston. Participants were randomly assigned to up to 22 sessions of CBT along with treatment as usual (TAU; n = 127) or TAU only (n = 126), and assessed on the measures reported in this study every 24 weeks for 18 months (i.e. at four time points: at baseline, 24th, 48th and 72nd week). Exclusion criteria were kept to a minimum so that the recruited sample reflected the clinical complexity of the population.

The sample was selected to be as representative as possible of patients with bipolar disorder likely to be considered for psychological intervention. Inclusion criteria were age ⩾18 years, diagnosis of bipolar disorder according to DSM-IV (APA, 1994), at least two episodes of the illness within the past 12 months (i.e. hypomania, mania, depression, mixed state) according to DSM-IV and contact with mental health services within the past 6 months. Exclusion criteria were an acute episode of mania (in which case patients were invited to take part once their manic episode had remitted), rapid-cycling bipolar disorder, bipolar disorder secondary to an organic cause, meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder according to DSM-IV, uncertain primary diagnosis due to substance misuse, current psychological treatment for bipolar disorder and inability to provide written informed consent. Treatment effects are described elsewhere (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Paykel, Morriss, Bentall, Kinderman, Johnson, Abbott and Hayhurst2006); in brief, there was no overall effect of CBT. Johnson et al.'s (Reference Johnson, Morriss, Scott, Paykel, Kinderman, Kolamunnage-Dona and Bentall2011) analysis of the relationship between depressive and manic symptoms in the sample was based on the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation-II (LIFE-II; Keller et al. Reference Keller, Lavori, Friedman, Nielson, Endicott, McDonald-Scott and Andreassen1987) symptom ratings obtained for weekly periods by telephone interview; the analyses reported here pertain to the less frequent Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Assessment Scale (MAS) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) face-to-face assessments conducted in the same study, which are more fine-grained, offer a wider range of scores and are therefore more suitable for analyses as continuous variables. The sample characteristics, including the proportions of patients in receipt of different kinds of medication at inception into the study (see Scott et al. Reference Scott, Paykel, Morriss, Bentall, Kinderman, Johnson, Abbott and Hayhurst2006 for more details), are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample characteristics (n = 253) at inception

HAMD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (cut-off point ⩾7 indicating relapse); MAS, Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Assessment Scale; s.d., standard deviation.

Clinical measures

Two clinical measures were administered in face-to-face interviews conducted by trained interviewers (see Scott et al. Reference Scott, Paykel, Morriss, Bentall, Kinderman, Johnson, Abbott and Hayhurst2006) at inception and then every 8 weeks for 18 months. For the purpose of the present analysis we included measures taken every 24 weeks only, coinciding with the administration of the psychological measures.

(1) The HAMD (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1960) consists of 17 items rated by the interviewer on a 0–4 scale. Scores of 6/7 and lower indicate remission, and scores >14 indicate need for treatment. The HAMD shows inter-rater reliability coefficients up to 0.90 (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1960), good validity and reliability (Rehm, Reference Rehm, Bellack and Hersen1988).

(2) The MAS, Modified Version (MAS-M; Licht & Jensen, Reference Licht and Jensen1997), is widely used to assess symptoms of mania and is designed to be administered alongside the HAMD. Each of its 11 items is rated on a five-point scale, resulting in a total score ranging between 0 and 44. The scale shows a high inter-observer reliability and an acceptable level of consistency across items (Bech et al. Reference Bech, Bolwig, Kramp and Rafaelsen1979).

Psychological measures

The following psychological measures were administered every 24 weeks for 18 months.

(1) The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire (RSEQ; Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg1965) is a 10-item measure assessing trait self-esteem. Scores on each of the two scales (positive self-esteem and negative self-esteem) can range from 5 to 20, with high scores reflecting high positive/negative self-esteem. Previous studies reported high total RSEQ scores endorsed by manic/hypomanic and remitted individuals (Lyon et al. Reference Lyon, Startup and Bentall1999; Scott & Pope, Reference Scott and Pope2003). In addition, Scott & Pope (Reference Scott and Pope2003) found that hypomanic patients score high on both the negative and positive RSEQ scales.

(2) The 24-item version of the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS; Power et al. Reference Power, Katz, McGuffin, Duggan, Lam and Beck1994) assesses negative cognitive schemas. Scores on each of the three eight-item subscales (achievement, dependency and self-control) can range from 8 to 56 and items are rated on a seven-point scale. Previous studies have shown that, similarly to those with major depression, bipolar I individuals report high levels of dysfunctional attitudes (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Scott, Haque, Gordon-Smith, Heron, Caesar, Cooper, Forty, Hyde, Lyon, Greening, Sham, Farmer, McGuffin, Jones and Craddock2005).

(3) The Internal, Personal and Situational Attributions Questionnaire (IPSAQ; Kinderman & Bentall, Reference Kinderman and Bentall1995) was modified from the Attributional Style Questionnaire (ASQ; Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, Semmel, von Baeyer, Abramson, Metalsky and Seligman1982) and is designed to assess the extent to which individuals attribute negative and positive events to different attributional loci. The scale consists of 32 social vignettes describing 16 positive and 16 negative events. The respondent is asked to generate the most likely cause of each event and to state whether the cause is due to self, other people or circumstances. Six subscale scores are generated (number of positive events attributed to self, other people, and circumstances; and corresponding scores for negative events) and these are used to calculate two composite scores: externalizing bias (EB) and personalizing bias (PB). EB is the difference between positive and negative events attributed to self (i.e. EB >0 indicates tendency to attribute more positive events than negative events to the self). PB indicates the proportion of negative events attributed to other people as opposed to external situations, and is calculated by dividing the proportion of negative events attributed to others by the sum of all negative events attributed to external causes (i.e. other people and circumstances; PB >0.5 a indicates tendency to attribute negative events to other people rather then circumstances). The IPSAQ presents acceptable reliability and validity, and has been used previously to assess schizophrenia patients (Kinderman & Bentall, 1996) but not bipolar patients. However, studies using the ASQ have found that bipolar manic patients show a normal self-serving bias whereas bipolar depressed patients have a tendency to attribute more negative than positive events to the self (Lyon et al. Reference Lyon, Startup and Bentall1999).

(4) The Personal Qualities Questionnaire (PQQ), based on the Selves Questionnaire (Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Bond, Klein and Strauman1986), was used to assess discrepancies between self-concepts. Participants are asked to generate three lists of up to 10 attributes describing: (a) themselves (self-actual); (b) who they would like to be (self-ideal); and (c) how they think other people see them (other-actual). We used the method of Scott & O'Hara (Reference Scott and O'Hara1993) to calculate two scores reflecting the consistency/discrepancy between the self-actual and self-ideal domains (self-actual:self-ideal) and between the self-actual and other-actual domain (self-actual:other-actual). Using MS Word's thesaurus we identified matches and mismatches between the relevant domains. Matches were identified if the same word or its synonym was used in the corresponding domains and mismatches if antonyms were used in the corresponding domains. Total self-actual:self-ideal and self-actual:other-actual discrepancy scores were calculated by subtracting the total number of matches from the total number of mismatches in each domain. Self-actual:self-ideal discrepancies have been shown to be related to depression (Strauman & Higgins, Reference Strauman and Higgins1988; Strauman, Reference Strauman1989) whereas self-actual:other-actual discrepancies have been shown to be associated with paranoia (Kinderman & Bentall, 1996). Bentall et al. (Reference Bentall, Kinderman and Manson2005) reported that, compared to controls, manic patients showed excessive consistency between self-actual and self-ideal domains whereas bipolar-depressed patients showed excessive discrepancy between the domains. They found that bipolar patients showed no evidence of abnormal self-actual:other-actual consistency/discrepancy scores.

Statistical analyses

The longitudinal structure of these data is likely to lead to violations of the independence of errors assumption underlying standard unilevel regression analyses. Multilevel modelling is the appropriate statistical technique for addressing these issues, as it allows for the nested nature of the data (repeated measurements nested within individuals; Twisk, Reference Twisk2006). We calculated two-level models using the xtreg module of Stata version 9.1 (Stata Corporation, USA), with psychological and clinical measures nested within each participant. To account for the unbalanced nature of the design (i.e. data missing in the dataset), all analyses were carried out using maximum likelihood estimation (Rabe-Hesketh & Skrondal, Reference Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal2005). All multilevel models were estimated on all available data. Hence, participants contributed to an analysis even if they had missing data on predictors, but not when they had missing data on the dependent variables (HAMD and MAS scores). First, a multilevel model was estimated to examine the bivariate association between depression and mania. Second, for each psychological predictor considered (self-esteem, externalizing bias, dysfunctional attitudes and self-discrepancies), separate multilevel models were estimated using symptom scores (HAMD and MAS) as the outcome variables. In light of Johnson et al.'s (Reference Johnson, Morriss, Scott, Paykel, Kinderman, Kolamunnage-Dona and Bentall2011) observation of a modest correlation between LIFE-II depression and mania scores over time, models of depression were corrected for the confounding effect of mania by adding MAS scores into the equation. Similarly, models of mania were also estimated while controlling for depression in the later analysis.

The cross-sectional analyses considered above allow for the investigation of the symptom-specific associations. However, these are not informative of the dynamic (and potentially causal) relationship between self-referential processes and symptoms. Therefore, we carried longitudinal multilevel regression analyses to examine whether the psychological variables found to be associated with depression and mania in the previous analyses predicted symptoms longitudinally. Specifically, we examined whether psychological variables at the previous assessment wave predicted current symptoms of depression and mania (i.e. psychological variables at T1 as predictors of outcome variables at T2; psychological variables at T2 as predictors of outcome variables at T3, and predictors at time T3 predict outcomes at time T4). In analyses using depression as the outcome variable, we controlled for the confounding effect of symptoms of depression at the previous assessment along with current levels of mania. Similar models were estimated for mania as the outcome variable, while controlling for the confounding effect of previous mania and current depression. Finally, all analyses were repeated to control for the potentially confounding effects of antidepressant, antipsychotic and mood-stabilizing medication.

Results

Group differences on clinical and psychological measures

As the data were drawn from a clinical trial comparing patients assigned to either CBT or TAU, we examined whether scores of the psychological variables and symptom measures (i.e. depression and mania) differed between groups assigned to different treatments. A series of multilevel regression models was estimated using the categorical predictor group as the independent variable. The results from multilevel analyses showed no significant between-group differences for patients assigned to different treatments for any of the psychological variables (i.e. self-esteem, dysfunctional attitudes, attributional style, and discrepancies between self-concept) or for the specific symptoms (i.e. depression and mania) considered in this study (all p's >0.11). These results are consistent with the main outcome findings reported elsewhere (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Paykel, Morriss, Bentall, Kinderman, Johnson, Abbott and Hayhurst2006). There was a relatively small but significant association between depression and mania [β = 0.17, s.e. = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.10 to 0.23]. This finding, using the HAMD and MAS ratings, replicates the previous findings of Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Morriss, Scott, Paykel, Kinderman, Kolamunnage-Dona and Bentall2011) using the more frequent LIFE-II ratings obtained from the same participants, and establishes the need to control for this co-morbidity in our analyses of the psychological data.

A breakdown of patients' symptoms at each assessment wave is provided in Table 2. As HAMD and MAS ratings are relevant for only a 1-week period, LIFE-II ratings for mania and depression were used instead. The score for each time point was retrieved as an average of two weekly ratings prior to each assessment. Using this classification of episodes experienced across the duration of the study, 161 participants (63.4%) were euthymic throughout, one (0.4%) participant was depressed throughout, and none were hypomanic/manic throughout. Eleven (4.3%) experienced both euthymia and hypomania/mania, 76 (29.9%) experienced both euthymia and depression, and none experienced depression and hypomania/mania in the absence of euthymia. Finally, five (2.0%) experienced all three types of episodes.

Table 2. Breakdown of mood symptoms ratings at each assessment wave using the LIFE-II

LIFE-II, Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation II: ‘no symptoms’ = ratings of 1; ‘subsyndromal symptoms’ = ratings of 1.5–4; ‘clinically symptomatic’ = ratings of 4.5–6.

Values given as n (%).

The association of the self-esteem scores with depression and mania

The results of analyses of positive and negative self-esteem in relation to current depression and mania are shown in Table 3. Depression was associated with high negative self-esteem and low positive self-esteem and these associations remained significant when controlling for the confounding effect of mania. When similar models were estimated with mania as the dependant variable, high positive self-esteem became significantly associated with mania only after controlling for current levels of depression. By contrast, high negative self-esteem lost statistical significance when current levels of depression were included in the model.

Table 3. Association of the positive and negative scales of the RSEQ with depression (HAMD) and mania (MAS)

RSEQ, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire; HAMD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MAS, Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Assessment Scale; CI, confidence interval; SE + , Positive Self-Esteem scale of the RSEQ; SE–, Negative Self-Esteem scale of the RSEQ; n.s., not significant.

** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

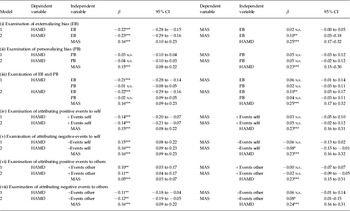

The association of the attributional style with depression and mania

The analyses of attributional style are shown in Table 4. Consistent with numerous studies of unipolar patients (Sweeney et al. Reference Sweeney, Anderson and Bailey1986), depression was associated with low externalizing bias and this effect remained after including mania in the model. Of note, in a model with mania as the outcome variable, an excessive externalizing bias reached significance, but only after adding depression into the model. Hence mania, when controlling for depression, was associated with an excessive tendency to assume external causes for negative events. Personalizing bias scores, which have been related to paranoia (Kinderman & Bentall, 1996), were not associated with either of the clinical outcomes.

Table 4. Association of the IPSAQ with depression (HAMD) and mania (MAS)

IPSAQ, Internal, Personal and Situational Attributions Questionnaire; HAMD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MAS, Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Assessment Scale; CI, confidence interval; +Events self, attributing positive events to self; –Events self, attributing negative events to self; +Events other, attributing positive events to others; –Events other, attributing negative events to others; n.s., not significant.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

To more closely study how attributions for negative and positive events were associated with bipolar depression, we carried out multilevel analyses that examined the extent to which positive and negative events were separately attributed to the three attributional loci: caused by self, caused by others or caused by circumstances (also shown in Table 4). We first carried out the analyses with the attributional style scores alone, and in a subsequent step controlled for the effect of mania. Depression was negatively associated with attributing positive events to self and negative events to others, but positively associated with attributing negative events to self and positive events to others. All of these effects remained when controlling for mania. By contrast, when we repeated these analyses for mania, we found it was negatively correlated with attributing negative events to self and positively correlated with attributing negative events to others, although both associations were weak. As in the analyses of the attributional composite scores, these findings were only significant when controlling for the confounding effect of depression. Attributions of negative or positive events to circumstances were not predictive of either depression or mania.

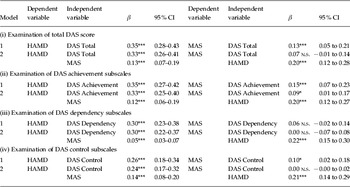

The association of the dysfunctional attitudes with depression and mania

The analyses of DAS scores are shown in Table 5. Consistent with previous research on unipolar depression (Power et al. 1995), total scores were associated with depression, and this effect remained when controlling for mania. In a similar model calculated with mania as the outcome variable, the total scores, which were initially significant, lost significance when depression was added into the model.

Table 5. Association of the DAS with depression (HAMD) and mania (MAS)

DAS, Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale; HAMD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MAS, Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Assessment Scale; CI, confidence interval; n.s., not significant.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

To investigate the role of a dysfunctional cognitive style in more detail, we carried out similar analyses with each of the subscale scores (i.e. achievement, dependency and control scales) as independent variables and with depression as the dependent variable. All of the subscales were associated with depression even after controlling for mania. When similar models were calculated with mania as the dependent variable, on the contrary, only achievement and control scores were associated with mania and this effect remained significant only for achievement when depression was added into the model.

The association of the self-consistency/self-discrepancy scores with depression and mania

Consistent with previous research with unipolar patients (Strauman, Reference Strauman1989), depression was associated with low self-actual:self-ideal consistency and also high self-actual:others-actual discrepancy, and these effects remained significant after including mania in the model (see Table 6). None of the self-consistency predictors was significantly associated with mania at the first stage. After controlling for depression, the self-actual:self-ideal consistency scores showed a weak positive association with mania, consistent with the findings of Bentall et al. (Reference Bentall, Kinderman and Manson2005).

Table 6. Association of the PQQ with depression (HAMD) and mania (MAS)

PQQ, Personal Qualities Questionnaire; sa:si, self-actual:self-ideal discrepancy; sa:oa, self-actual:others-actual discrepancy; HAMD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MAS, Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Assessment Scale; CI, confidence interval; n.s., not significant.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Psychological variables measured at an earlier time point as predictors of current depression and mania

As outlined in our analysis plan, we also attempted to determine whether our psychological variables predicted symptoms at a future assessment point (see Table 7). We found that low positive self-esteem and high negative self-esteem at the previous assessment wave were significantly associated with current depression and that this effect remained even after controlling for previous depression and current mania. Similar associations were found when mania was the outcome variable; low positive self-esteem and high negative self-esteem at the previous assessment wave were significant predictors of mania. However, this effect did not remain significant when current levels of depression were added into the model. No other psychological variable significantly predicted future symptoms.

Table 7. RSEQ at previous assessment wave as a predictor of current depression (HAMD) and mania (MAS)

RSEQ, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire; HAMD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MAS, Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Assessment Scale; CI, confidence interval; SE + _lag, positive self-esteem at previous assessment wave; SE–_lag, negative self-esteem at previous assessment wave; HAMD_lag, depression at previous assessment wave; MAS_lag, mania at previous assessment wave; n.s., not significant.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Controlling for the effects of medication

To rule out any potential confound due to medications, a series of multilevel analyses was carried out to investigate the associations between medication use (i.e. three dichotomous variables representing use of antipsychotic, antidepressant and mood stabilizing medication) and the symptom and psychological variables used in the present analyses. No association was found between the symptom variables and current use of antipsychotics or mood-stabilizing medications (all p's >0.05). However, current use of antidepressants was significantly related to more severe depressive symptoms (p < 0.05), but no statistically significant association was observed with symptoms of mania (p > 0.05). The use of antidepressants was also significantly related to several psychological measures of interest, including lower positive self-esteem, higher negative self-esteem, lower externalizing bias scores, greater self-attributions for negative events, greater other-attributions for positive events and higher DAS dependency scores (all p's <0.05). Despite these associations, when we reran all of the previous analyses on the cross-sectional and prospective relationships between psychological variables and symptoms after controlling for the effect of medication use, all of the findings remained unchanged. These findings suggest that the relationship between negative cognitive style and antidepressant use is confounding by indication; that is, that negative cognitive styles are related to depressive symptoms that, in turn, lead to use of antidepressants.

Discussion

Bipolar symptoms are inherently unstable over time, presenting special challenges for attempts to understand the underlying mechanisms responsible. A further complication is that depressive and manic symptoms can vary independently over time within the same individual (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Morriss, Scott, Paykel, Kinderman, Kolamunnage-Dona and Bentall2011), exacerbating the difficulty of identifying which mechanisms are associated with each group of symptoms. To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate how cognitive self-referential processes relate to bipolar symptoms in a way that adequately addresses these difficulties. We examined these relationships, and the predictive properties of the psychological measures, longitudinally, that is in four assessments over a period of 18 months, using robust statistical methods that allow for the inter-relatedness of data.

Our findings require comment and review. First, our cross-sectional analyses show that many of our measures related to the current symptom status of the patients participating in the study. Self-esteem, externalizing bias, dysfunctional attitudes and self-discrepancies were associated with the current severity of depressive symptoms, and these associations remained significant when mania was controlled for in the models. These findings, using robust methods, confirm that, at a psychological level, bipolar depression seems to be very similar to unipolar depression, as observed by previous researchers (e.g. Scott et al. Reference Scott, Stanton, Garland and Ferrier2000; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Scott, Haque, Gordon-Smith, Heron, Caesar, Cooper, Forty, Hyde, Lyon, Greening, Sham, Farmer, McGuffin, Jones and Craddock2005; Alloy et al. Reference Alloy, Abramson, Walshaw and Neeren2006).

Consistent with observations of the relationships between goal attainment and goal pursuit (Johnson, Reference Johnson2005; Taylor & Mansell, Reference Taylor and Mansell2008), current mania was only associated with the achievement subscale of the DAS, once depression had been controlled for. This finding is consistent with Alloy et al.'s (2009) observation that bipolar individuals score highly on cognitions specifically related to behavioral activation system sensitivity, as proposed by Depue et al. (Reference Depue, Krauss, Spoont, Magnusson and Ohman1987) and Depue & Iacono (Reference Depue and Iacono1989). Several other self-referential processes became weakly, but significantly, associated with current mania only after controlling for current depression; namely, the self-serving externalizing attributional bias (i.e. avoidance of attributing negative events to self and an inclination to attribute negative events to external causes) and an abnormally low discrepancy between perceptions of the actual self and ideals (similar affects for self-esteem are discussed later). A possible explanation for this observation, in line with psychoanalytic theories beginning with Abraham (Reference Abraham and Jones1911/1927), is that current mania is associated with a tendency to avoid negative beliefs about the self. Another related interpretation is that bipolar patients have increased need for social approval and desirability (Pardoen et al. Reference Pardoen, Bauwens, Tracy, Martin and Mendlewicz1993).

However, all of these observations concern psychological abnormalities, which are temporarily closely linked to symptoms. Our prospective analyses revealed few associations between our psychological variables and future symptoms, thereby confirming that most of the mechanisms under investigation (for example, dysfunctional attitudes and attributional processes) are tied to current symptom severity. However, self-esteem seemed to be not entirely state related, predicting depression longitudinally. Of note, the observed relationship between self-esteem and mania was different for the cross-sectional versus longitudinal analyses. In our cross-sectional analyses, current mania was significantly associated with high positive self-esteem after controlling for concurrent depression, whereas negative self-esteem no longer reached significance after concurrent levels of depression were included in the model. By contrast, longitudinally, future mania was predicted by low positive and high negative self-esteem, which is the pattern that we found to be associated with current depression cross-sectionally. It is important to note that the predictive properties of self-esteem for mania were not sustained when current depression was added into the model. A possible explanation for this group of findings is that negative self-esteem leads to future depression, which in turn leads to compensatory mechanisms in an attempt to avoid depressive feelings, for example externalizing attributions, thereby provoking manic symptoms.

These findings add to existing evidence about the role of self-esteem and related processes in bipolar disorder. In a meta-analytic study, Nilsson et al. (2010) showed that remitted bipolar patients have, in general, lower self-esteem compared to control participants, but slightly higher self-esteem than unipolar depressed patients. Studies comparing patients with bipolar disorder and major depression have found similarities in both groups but only on implicit (rather than explicitly assessed) self-esteem (Corwyn, Reference Corwyn2000). In a study comparing bipolar remitted, unipolar and healthy individuals, Knowles et al. (Reference Knowles, Tai, Jones, Highfield, Morriss and Bentall2007) found that remitted bipolar patients showed a seemingly contradictory pattern of normal self-esteem when measured explicitly, but highly unstable self-esteem when assessed over a period of a few days, and concluded that the instability was indicative of a negative underlying self-schema. Similarly, Scott & Pope (Reference Scott and Pope2003) found that high scores on negative self-esteem were predictive of future depressive episodes. In sum, our results support previous evidence that bipolar depression is related to, and predicted by, low self-esteem (Staner et al. Reference Staner, Tracy, Dramaix and Genevrois1997; Johnson et al. 2000; Scott & Pope, 2003) using explicit measures and a longitudinal assessment.

Despite the strengths of the present study (a large representative sample, a longitudinal design with repeated assessments, carried out by trained raters), some limitations must be acknowledged. Although we have shown that many of the processes we investigated are associated with current symptoms, the absence of a healthy control group prevented us from determining whether there was a residual negative cognitive style when the patients were euthymic. In a cross-sectional study comparing controls with bipolar patients in different episodes, Van der Gucht et al. (Reference Van der Gucht, Morriss, Lancaster, Kinderman and Bentall2009) reported that negative cognitive processes were most evident during bipolar depression, but were present in an attenuated form even during the euthymic phase. A second limitation concerns the measures used, which reflected our understanding of bipolar disorder at the time that the study was designed. Hence, the relatively few associations between self-referential processes and mania may be due, at least partly, to the fact that these measures were developed to assess cognitive styles in individuals with unipolar depression rather than, for example, reward-seeking, which is now thought to be an important process in mania (Johnson, Reference Johnson2005; Abler et al. Reference Abler, Greenhouse, Ongur, Walter and Heckers2008). In particular, we could have used measures of behavioral activation (Van der Gucht et al. Reference Van der Gucht, Morriss, Lancaster, Kinderman and Bentall2009) and goal pursuit-related appraisals (Mansell & Morrison, Reference Mansell and Morrison2007) and these should be included in future studies of this kind.

As noted earlier, to our knowledge this is the first study of psychological processes in bipolar disorder to use robust statistical methods to allow for covariation between symptoms and fluctuations over time. We consider that our approach has implications for, and is applicable to, any condition in which symptom covariation and instability over time is an issue (probably the majority of psychiatric disorders). In terms of clinical implications, the findings accentuate the importance of the therapeutic management of negative self-concept shared by both depression and mania in bipolar disorder.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Medical Research Council (original data collection; Project ref.: G9721149) and by a studentship for H. Pavlickova from the National Institute for Social Care and Health Research, the Welsh Assembly Government (Project ref.: HS/09/004).

Declaration of Interest

None.