Introduction

Social phobia, also known as social anxiety disorder, is a condition involving marked anxiety about social or performance situations in which there is a fear of embarrassing oneself under scrutiny by others (APA, 1994). Epidemiological surveys have shown social phobia to be a common disorder characterized by substantial co-morbid psychopathology and functional impairment (Schneier et al. Reference Schneier, Johnson, Hornig, Liebowitz and Weissman1992; Magee et al. Reference Magee, Eaton, Wittchen, McGonagle and Kessler1996; Furmark et al. Reference Furmark, Tillfors, Everz, Marteinsdottir, Gefvret and Fredrikson1999; Wittchen et al. Reference Wittchen, Stein and Kessler1999; Stein et al. Reference Stein, Torgrud and Walker2000). Social phobia's earlier onset compared with many other mental disorders (Weissman et al. Reference Weissman, Bland, Canino, Greenwald, Lee, Newman, Rubio-Stipec and Wickramaratne1996; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Stang, Wittchen, Stein and Walters1999, Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin and Walters2005a; Wittchen et al. Reference Wittchen, Stein and Kessler1999) and close association with putative risk factors such as behavioral inhibition (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Beidel and Wolff1996; Hayward et al. Reference Hayward, Killen, Kraemer and Taylor1998) and low positive affect (Mineka et al. Reference Mineka, Watson and Clark1998) suggest that social phobia may be an important target for broader prevention efforts as well as being a significant condition in its own right. However, despite growing awareness and understanding of social phobia (Heimberg et al. Reference Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995; Tarrier, Reference Tarrier2004; Coles & Horng, Reference Coles, Horng and Andrasik2006), information is lacking on key aspects of the disorder. The current report aimed to address some of these gaps using data from the recently completed National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R; Kessler & Merikangas, Reference Kessler and Merikangas2004).

The NCS-R expands on earlier epidemiological surveys of social phobia in four important ways. First, previous community surveys have yielded widely varying estimates of the prevalence of social phobia and, consequently, the extent of the public health problem posed by the disorder (Stein et al. Reference Stein, Walker and Forde1994; Magee et al. Reference Magee, Eaton, Wittchen, McGonagle and Kessler1996; Alonso et al. Reference Alonso, Angermeyer, Bernert, Bruffaerts, Brugha, Bryson, de Girolamo, Graaf, Demyttenaere, Gasquet, Haro, Katz, Kessler, Kovess, Lepine, Ormel, Polidori, Russo, Vilagut, Almanza, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, Autonell, Bernal, Buist-Bouwman, Codony, Domingo-Salvany, Ferrer, Joo, Martinez-Alonso, Matschinger, Mazzi, Morgan, Morosini, Palacin, Romera, Taub and Vollebergh2004; Grant et al. Reference Grant, Hasin, Blanco, Stinson, Chou, Goldstein, Dawson, Smith, Saha and Huang2005). To provide a more definitive prevalence estimate, social phobia diagnoses in the NCS-R were validated through independent semi-structured clinical interviews. Second, although there is considerable interest in potential subtypes of social phobia (Heimberg et al. Reference Heimberg, Holt, Schneier, Spitzer and Liebowitz1993; Furmark et al. Reference Furmark, Tillfors, Stattin, Ekselius and Fredrikson2000; Stein et al. Reference Stein, Torgrud and Walker2000; Hofmann et al. Reference Hofmann, Heinrichs and Moscovitch2004), few previous surveys have included a sufficiently large set of situational probes to test for subtype distinctions. The NCS-R assessed a larger number of social situations than previous surveys in order to address this issue, expanding in particular the assessment of interactional social fears. We consider evidence for subtypes based on number of social fears, such as the DSM-IV generalized subtype involving fears of ‘most’ social situations, and subtypes based on content of social fears, such as the distinction between performance and interactional fears that has been emphasized by some experts (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Beidel and Townsley1992; Hook & Valentiner, Reference Hook and Valentiner2002). Third, prior surveys have been limited by global measures of functional impairment and by a failure to separate the impairment due to social phobia versus co-morbid conditions. The NCS-R included a more extensive assessment of impairment than previous surveys and also assessed a wide range of co-morbid DSM-IV disorders. We control for co-morbid disorders to evaluate the unique effects of social phobia on role impairment. Finally, little is known about help-seeking in social phobia. We present novel data on utilization of mental health services by those with the disorder, including the proportion of affected cases who report receiving treatment specifically for social phobia.

Method

Sample

The NCS-R is a nationally representative face-to-face household survey of people aged 18+ years fielded between February 2001 and December 2003. Respondents were sampled using a multi-stage clustered area probability design. As in the baseline NCS (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, McGonagle, Zhao, Nelson, Hughes, Eshleman, Wittchen and Kendler1994), an initial recruitment letter and study fact brochure were followed by a visit from a professional survey interviewer, who described the study and obtained verbal informed consent before the interview. The response rate was 70.9%.

The NCS-R interview included two parts administered in one session. Part I comprised the core diagnostic assessment and was administered to all respondents (n=9282). Part II assessed additional disorders and correlates and was administered to all Part I respondents with any lifetime core disorder plus a probability subsample of other respondents (n=5692). The Part I sample is used here to examine prevalence and course, role impairment, treatment, and co-morbidity of DSM-IV social phobia with other Part I disorders. The Part II sample is used to examine sociodemographic correlates and co-morbidity with disorders assessed only in the Part II sample. The Part I sample was weighted to adjust for differential probability of selection and for residual variation between sample and population distributions on geographic and sociodemographic variables in the 2000 US Census. The Part II sample was additionally weighted to adjust for the higher selection probability of Part I respondents with a lifetime disorder. Further description of NCS-R sampling and weighting procedures appears elsewhere (Kessler & Merikangas, Reference Kessler and Merikangas2004).

Social fears and social phobia

Social phobia was assessed by Version 3.0 of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI 3.0; Kessler & Ustun, Reference Kessler and Ustun2004), a fully structured lay-administered interview. Respondents were administered the social phobia section if they endorsed a diagnostic stem question for either a performance or an interactional fear that was excessive and caused substantial distress, nervousness, or avoidance. The social phobia section assessed lifetime experiences of shyness, fear, or discomfort in each of 14 social situations. Respondents endorsing one or more of these fears were asked about age of the first fear and age of first avoidance. Responses of ‘all my life’ or ‘as long as I can remember’ were probed to determine whether onset occurred before first starting school (coded as age 4) or before (age 12) or after (age 13) the teenage years. Respondents were then assessed for DSM-IV social phobia. DSM-IV diagnostic hierarchy rules were not applied in making diagnoses of social phobia or any other mental disorder to minimize the impact of uncertain hierarchical exclusions on the relationship of social phobia with other disorders. The CIDI social phobia diagnoses were subsequently compared to clinical diagnoses based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al. Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams2002) in blind clinical reinterviews of a probability subsample of NCS-R respondents (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Abelson, Demler, Escobar, Gibbon, Guyer, Howes, Jin, Vega, Walters, Wang, Zaslavsky and Zheng2004). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.65 and the κ value (standard error) was 0.35 (0.07). The estimated prevalence of social phobia diagnosed by the CIDI was somewhat lower than that diagnosed by the SCID (McNemar χ12=5.7, p=0.017), suggesting that the CIDI diagnoses are conservative.

Co-morbid DSM-IV disorders

Other anxiety, mood, substance use, and impulse-control disorders were assessed using CIDI 3.0. As detailed elsewhere (Haro et al. Reference Haro, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, Brugha, De Girolamo, Guyer, Jin, Lepine, Mazzi, Reneses, Vilagut, Sampson and Kessler2006), blinded clinical reappraisal interviews using the SCID found generally good concordance between CIDI and SCID diagnoses of anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders. Diagnoses of impulse-control disorders were not validated due to the absence of a gold standard clinical assessment for these disorders in adults.

Other measures

Other correlates of social phobia examined here include sociodemographics, role impairment, and treatment-seeking. The sociodemographic variables include age at interview, sex, race-ethnicity, education, marital status, employment status, and family income. Impairment among 12-month cases was assessed by the Sheehan Disability Scales (Leon et al. Reference Leon, Portera, Olfson, Weissman, Kathol, Farber, Sheehan and Pleil1997), which asked about interference caused by social phobia in the domains of home management, work, close relationships, and social life during the month in the past year when social phobia was most severe. Each domain was self-rated by respondents on a 0–10 scale reflecting the extent to which social phobia interfered with the respondent's ability to function in the domain. Responses were collapsed into broad categories of Severe Impairment (responses in the range 7–10) and Any Impairment (in the range 1–10). Lifetime treatment and 12-month treatment were assessed specifically for social phobia and more generally for any mental health problem. Use of mental health services was assessed within five sectors: general medical, psychiatry, non-psychiatry mental health specialty, human services, and complementary-alternative.

Statistical analysis

Cross-tabulations were used to estimate prevalence of social fears and social phobia. Tetrachoric factor analysis was used to investigate the number of factors underlying the 14 social fears assessed by the CIDI. Latent class analysis (Goodman, Reference Goodman, Hagenaars and McCutcheon2002), performed using the iterative-fitting nag fortran library routine E04UCF (Numerical Approximation Group, 1990), was used to investigate the possibility of non-additivities in the associations among social fears. Selection of the optimal number of latent classes was based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; Burnham & Anderson, Reference Burnham and Anderson1998). The program selected random start values and replicated results 25 times to ensure there was no local minimum problem in solutions. The actuarial method (Halli & Rao, Reference Halli and Rao1992), a statistical method for projecting the risk of disorder onset in any given year of life, was used to estimate age-of-onset distributions for four mutually exclusive social phobia subgroups distinguished by their number of social fears. Associations of social phobia and the four subgroups with co-morbid disorders and sociodemographics were estimated using logistic regression. Conditional probabilities of impairment and treatment-seeking were examined using cross-tabulations. Standard errors and significance tests were estimated using the Taylor series linearization method (Wolter, Reference Wolter1985) implemented in the sudaan (Research Triangle Institute, 2002) software system to adjust for weighting and clustering in the NCS-R sample design. The associations of social phobia with multivariate correlates (e.g. the set of three dummy variables representing education) were evaluated using Wald χ2 tests based on design-corrected coefficient variance-covariance matrices. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed 0.05-level tests.

Results

Prevalence

As has been reported elsewhere (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin and Walters2005a, Reference Kessler, Chiu, Demler and Waltersb), prevalence estimates (standard error) for lifetime and 12-month DSM-IV social phobia are 12.1% (0.4) and 7.1% (0.3) respectively. Nearly one-quarter (24.1%) of all respondents in the survey reported at least one lifetime social fear, roughly twice the number of respondents with lifetime social phobia (Table 1). The most common lifetime social fears among those considered here are public speaking (21.2%) and speaking up in a meeting or class (19.5%). The least common fears are using a bathroom away from home (5.7%) and writing, eating, or drinking while being watched (8.1%).

Table 1. Lifetime prevalence of social fears and DSM-IV social phobia (n=9282)

SO, Social phobia; s.e., standard error.

a Percentages in this column equal the product of the percentages in the preceding two columns. For example, 9.7% of respondents in the Part I sample have a lifetime history of social phobia involving a fear of meeting new people.

b n=1143.

c Social fears assessed included both interactional fears (meeting new people, talking to people in authority, going to parties, entering an occupied room, talking with strangers, expressing disagreement, dating situation) and performance fears (speaking up in meeting/class, public speaking/performance, important examination/interview, working while being watched, writing/eating/drinking while being watched, using public bathroom).

Conditional probability of social phobia does not differ strongly across the social fears considered here. By contrast, a monotonic relationship exists between number of social fears and lifetime prevalence of social phobia, with conditional probabilities ranging from a low of 12% among respondents with only one fear to nearly 80% among respondents with all 14 fears considered here. Seventy-one percent of respondents estimated to meet lifetime criteria for social phobia met our operational definition of generalized social phobia by reporting eight or more fears.

Latent structure

Tetrachoric correlations were calculated among the 14 performance and interactional fears in the total sample and found to range from 0.73 to 0.98 with an interquartile range of 0.85–0.91 (detailed results available on request). Factor analysis of this matrix found a strong first factor (eigenvalue of 12.3) and a negligible second factor (eigenvalue of 0.2). Item loadings on the first unrotated factor from this analysis ranged from 0.82 (using public bathrooms) to 0.98 (meeting new people, speaking up in a meeting/class, public speaking).

A latent class analysis was performed to investigate the possibility that non-additive associations among fears exist that were missed by the factor analysis, which ignores interactions among items. If so, this could lead to more differentiation in the structure of multivariate fear profiles than suggested by the strong unidimensionality found in the factor analysis. A four-class solution provided the best fit to the data among respondents with lifetime social phobia based on a lower value of BIC (15416) than was obtained for other models (15442–15751). Class proportions range from 17.1% of cases in Class 1 to 36.0% of cases in Class 3. The general pattern is for conditional probabilities of individual fears to increase monotonically from Class 1 to Class 4, with the average number of fears among respondents in the classes ranging from 5.2 in Class 1 to 6.9 in Class 2, 9.3 in Class 3, and 12.0 in Class 4 (conditional probability estimates within classes available on request). Of 39 pairwise comparisons across contiguous classes (i.e. each of 13 fears compared in Classes 1 v. 2, 2 v. 3, and 3 v. 4), 85% show the conditional probability of the fear to be higher in the higher class and all but one violation of this pattern are substantively insignificant. The exception is a substantially higher conditional probability of fear of writing, eating, or drinking while being watched in Class 1 (99%) than in Classes 2–4 (25–83%). This finding might be taken to mean that Class 1 defines a unique profile of performance fears. However, fear of going to parties, an interactional fear, also has a high conditional probability in Class 1, arguing against this interpretation. Based on these observations, in conjunction with the strong general pattern of monotonicity in the table and the strong unidimensionality of the factor analysis results, we made no distinction between performance and interactional fears in subsequent analyses.

The finding of nested latent classes in which the predicted probabilities of varied social fears are generally higher in higher classes suggests that the classes are describing different levels of severity along a single dimension. As the four classes were differentiated largely by number of fears, respondents who met CIDI criteria for lifetime social phobia were classified into one of four ordered subgroups based on the number of fears they reported: 1–4 (10.3%), 5–7 (18.6%), 8–10 (31.0%), and 11+ (40.1%). The latter two subgroups feared more than half of the 14 situations assessed and consequently were considered to meet the DSM-IV definition of generalized social phobia, which requires fears about ‘most’ social situations. The generalized group was further subdivided based on the observation that conditional risk of social phobia increases markedly with 11 or more fears. The non-generalized group was further subdivided to examine the subset of cases falling closest to the diagnostic boundary, with the cut at four or fewer fears chosen to ensure a sufficient sample size in each non-generalized subgroup.

Age-of-onset distributions

Cumulative distributions of age at first fear were found to differ significantly across the four social phobia subgroups (χ32=27.6, p<0.001) (Fig. 1). Number of fears is positively associated with early onset of social fear, although the age-of-onset distributions for subgroups with 5–7, 8–10 and 11+ fears are substantively similar in that all have their highest slope between early childhood and mid-adolescence and there are few new onsets after the teen years. By contrast, the subgroup with 1–4 fears has a shallower slope, with fewer childhood onsets and a more gradual accumulation of new cases into the mid-20s.

Fig. 1. Age of onset of first social fear in four mutually exclusive social phobia subgroups involving different numbers of social fears. Cumulative age-of-onset distributions were estimated in the subsample of respondents with lifetime social phobia. The distributions differ significantly across the four social phobia subgroups (χ32=27.4, p<0.001).

Separate analysis in the subsample of respondents who report avoidance finds that avoidance is significantly related to number of fears (results not shown, but available on request). Avoidance of social situations is least common in the subgroup with 1–4 fears (67.5%) and increases monotonically with 5–7 (74.8%), 8–10 (79.3%) and 11+ (88.1%) fears (χ32=26.7, p<0.001). The age-of-onset distributions for avoidance are very similar to those for fear, with earlier onsets and steeper slopes found for subgroups with more fears. The main difference is that, for all subgroups, the age of first avoidance (median=12–14 years) is 1–2 years later than the age of first fear (median=10–13 years).

Recovery distributions

Survival distributions for recovery (2+ years free of symptoms) show that recovery is most likely for social phobia involving 1–4 fears and is somewhat more rapid for subgroups with fewer fears (χ32=8.1, p=0.043) (results not shown, but available on request). Nevertheless, the curves are similar in shape and slope and indicate that, regardless of number of fears, recovery typically takes decades to occur. Only 20–40% of social phobia cases recover within 20 years of onset and only 40–60% recover within 40 years.

Co-morbidity

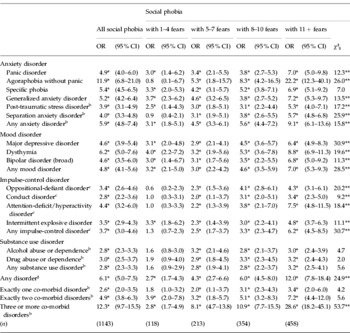

Nearly two-thirds (62.9%) of respondents with lifetime social phobia involving 1–4 fears meet criteria for at least one other lifetime DSM-IV/CIDI disorder and the proportions are even higher for social phobia with 5–7 fears (75.2%), 8–10 fears (81.5%) and 11+ fears (90.2%). This dose–response pattern is clearest for co-morbidity with other anxiety disorders and weakest for substance use disorders (detailed results available on request). Lifetime social phobia has a significantly elevated odds ratio (OR) with every DSM-IV disorder assessed in the NCS-R (Table 2). This pattern is not due to the confounding effect of time at risk, as the ORs were estimated in logistic regression equations that controlled for age in addition to sex and race-ethnicity. The ORs are highest with other anxiety disorders (3.9–11.9), lower with mood disorders (4.6–6.2), and lowest with impulse-control (2.8–4.4) and substance use (2.8–3.0) disorders. A statistically significant dose–response relationship exists between number of social fears and odds of most co-morbid disorders.

Table 2. Lifetime co-morbidity (OR)Footnote a of social phobia and four mutually exclusive social phobia subgroups with other DSM-IV disorders

OR, Odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

a The ORs were estimated in logistic regression models controlling for age at interview, sex, and race-ethnicity. The ORs compare respondents in each group with respondents who have no lifetime history of social phobia. The 3 degrees of freedom χ2 test compares social phobia subgroups involving 1–4 (n=118), 5–7 (n=213), 8–10 (n=354), and 11+ (n=458) fears, indicating whether the association of social phobia with each disorder varies significantly by number of fears. All disorders were defined using DSM-IV criteria without observing hierarchical exclusion rules.

b Assessed in the Part II sample (n=5692).

c Restricted to Part II respondents ages 18–44 (n=3197).

* Significant at the 0.05 level, two-sided test.

** Significant difference between the four mutually exclusive social phobia subgroups at the 0.05 level.

Role impairment

Nearly all respondents (92.6%) with 12-month social phobia reported role impairment as a result of social anxiety, with more than one-third (36.5%) reporting severe impairment in at least one domain of functioning (Table 3). As expected, the greatest impairment and clearest dose–response relationship with number of fears were found in the domains of social life and close relationships. Across role domains, the subgroup with 1–4 fears generally is least impaired while the subgroup with 11+ fears is most impaired. The greatest difference in impairment is typically between social phobia involving 1–4 versus 5+ fears.

Table 3. Role impairmentFootnote a in 12-month social phobia and four mutually exclusive social phobia subgroups

s.e., Standard error.

a Role impairment was assessed for respondents with social phobia who were in episode in the past 12 months. The 3 degrees of freedom χ2 test compares social phobia subgroups involving 1–4 (n=59), 5–7 (n=118), 8–10 (n=207), and 11+ (n=295) fears, indicating whether impairment varies significantly by number of fears.

b Values represent the proportions (standard errors) of respondents reporting severe or very severe impairment (score of 7–10) in each of the four Sheehan Disability Scale domains of functioning.

c Values represent the proportions (standard errors) of respondents reporting mild, moderate, severe, or very severe impairment (score of 1–10) in each of the four Sheehan Disability Scale domains of functioning.

* Significant difference between the four mutually exclusive social phobia subgroups at the 0.05 level.

To evaluate the independent impact of social phobia on impairment, analyses were replicated separately for 12-month pure (n=197) and co-morbid (n=482) cases (detailed results available on request). The dose–response pattern was found to be weaker among pure cases. The proportion of cases reporting severe impairment was also lower among pure than co-morbid cases, suggesting that the association between number of fears and impairment is partly explained by co-morbidity. Nevertheless, 89.9% of pure cases reported at least some functional impairment in the past 12 months resulting from social phobia, especially in social life (82.4%) and close relationships (71.0%).

Sociodemographic correlates

Sociodemographic correlates of lifetime DSM-IV social phobia include being younger than 60, previously married, and having ‘other’ employment status (mostly unemployed or disabled) (detailed results available on request). Being Hispanic or non-Hispanic Black is associated with reduced odds of social phobia. While all of these correlates are statistically significant, the ORs are fairly modest in magnitude (0.5–2.2). Furthermore, the association of each sociodemographic variable with social phobia varies significantly with number of fears. Social phobia involving 1–4 fears is more common among males and those of ‘other’ race-ethnicity (mostly American Indian or Asian). By contrast, social phobia involving a larger number of fears is significantly related to being younger, female, neither Hispanic nor non-Hispanic Black, never or previously married, neither a student nor retired, having less than a college education, an ‘other’ employment status, and low income. There are no consistent, meaningful differences in the sociodemographic correlates of pure and co-morbid lifetime social phobia.

Treatment

Roughly two-thirds (68.9%) of respondents with lifetime social phobia reported receiving treatment for a mental health problem at some time in their lives (Table 4). Only about one-third (35.2%) of lifetime cases, in comparison, reported ever receiving treatment specifically for social phobia. Respondents with 1–4 fears were seen about equally in general medical (38.8%) and mental health specialty (35.3%) settings, whereas those with 5+ fears were more often seen in mental health specialty (49.5–54.4%) than general medical (35.3–40.1%) settings. Number of fears is positively related to lifetime treatment. The proportions of lifetime cases that ever received treatment for any mental health problem (63.1–71.4%) and for social phobia (28.9–39.2%) increase monotonically across the four subgroups, although subgroup differences are fairly small in substantive terms. Subgroup differences are smaller for 12-month treatment and the association with number of lifetime fears is less clear.

Table 4. Lifetime and 12-month treatmentFootnote a of social phobia and four mutually exclusive social phobia subgroups

CAM, Complementary-alternative medicine; s.e., standard error.

a Values represent the proportions (standard errors) of respondents with social phobia who reported receiving treatment for any mental health problem or for social phobia specifically. A 3 degrees of freedom χ2 test compares the four social phobia subgroups, indicating whether lifetime or 12-month treatment-seeking varies significantly by number of fears.

b Includes primary care doctor, other general medical doctor, nurse, or any other health professional not mentioned elsewhere.

c Includes psychiatrist, psychologist, or other mental health professional in any setting; social worker or counselor in a mental health specialty setting; use of a mental health hotline.

d Includes religious or spiritual advisor, social worker or counselor in any setting other than a specialty mental health setting.

e Includes any other type of healer, participation in an internet support group, or participation in a self-help group.

f Refers to treatment obtained specifically for social phobia in any setting.

* Significant at the 0.05 level, two-sided test.

When analyses are restricted to pure (non-co-morbid) cases of social phobia, there is a significant inverse relationship between number of fears and social phobia-specific treatment (detailed results available on request). Among pure lifetime cases (n=213), the highest proportion who ever received treatment for social phobia is found in the subgroup with 1–4 fears (25.9%) and decreases monotonically with 5–7 fears (16.6%), 8–10 fears (14.3%), and 11+ fears (8.4%). There is a similar decrease among pure 12-month cases (n=197), with a sharp decline in 12-month social phobia treatment between the subgroup with 1–4 fears (15.9%) and all other subgroups (4.4–7.4%).

Discussion

These results should be interpreted in the context of three notable limitations. First, social phobia was assessed by fully structured lay interviews. Although clinical reappraisal studies have found generally good agreement between CIDI and SCID DSM-IV diagnoses, there is a tendency for CIDI lifetime prevalence estimates, including the social phobia estimates, to be conservative relative to SCID-based estimates (Haro et al. Reference Haro, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, Brugha, De Girolamo, Guyer, Jin, Lepine, Mazzi, Reneses, Vilagut, Sampson and Kessler2006). Had we applied the DSM-IV diagnostic hierarchy rules for social phobia, the CIDI prevalence estimates might be lower still. This suggests that the prevalence and societal burden of social phobia is underestimated by the CIDI results presented here. Although clinical diagnoses provide an important benchmark and the modest concordance of SCID and CIDI diagnoses is clearly a limitation of the study, the SCID itself is neither perfectly reliable nor a ‘gold standard’ measure of social phobia. For these reasons, CIDI–SCID concordance estimates might most appropriately be interpreted as lower-bound estimates of CIDI validity.

Second, respondents were administered the social phobia section if they reported at least one social fear that was excessive and associated with substantial anxiety or avoidance. This is in contrast to the baseline NCS, which required only that respondents report an ‘unreasonably strong’ social fear to be assessed for social phobia, and thus identified more respondents as having social fears. As the NCS-R screening questions excluded people with milder social fears from further assessment, our estimates of the prevalence of social fears are likely to be underestimates. Third, reports concerning age of onset and lifetime symptoms and treatment were recalled retrospectively. Although a number of strategies were used to reduce recall errors in the NCS-R (Kessler & Ustun, Reference Kessler and Ustun2004), they probably did not completely remove the differential recall accuracy likely to be associated with length of recall period.

Within the context of these limitations, the prevalence estimates of DSM-IV/CIDI social phobia (lifetime 12.1%, past-year 7.1%) are similar to the prevalence estimates of DSM-III-R social phobia reported a decade ago in the baseline NCS (lifetime 13.3%, past-year 7.9%) (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, McGonagle, Zhao, Nelson, Hughes, Eshleman, Wittchen and Kendler1994; Magee et al. Reference Magee, Eaton, Wittchen, McGonagle and Kessler1996), although higher than the prevalence estimates obtained in more recent epidemiological surveys (Alonso et al. Reference Alonso, Angermeyer, Bernert, Bruffaerts, Brugha, Bryson, de Girolamo, Graaf, Demyttenaere, Gasquet, Haro, Katz, Kessler, Kovess, Lepine, Ormel, Polidori, Russo, Vilagut, Almanza, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, Autonell, Bernal, Buist-Bouwman, Codony, Domingo-Salvany, Ferrer, Joo, Martinez-Alonso, Matschinger, Mazzi, Morgan, Morosini, Palacin, Romera, Taub and Vollebergh2004; Grant et al. Reference Grant, Hasin, Blanco, Stinson, Chou, Goldstein, Dawson, Smith, Saha and Huang2005). Unlike previous estimates, the NCS-R prevalence estimate was validated against clinician-administered SCIDs, which found that independent clinicians arrive at a prevalence estimate slightly higher than the CIDI estimate. This raises the question why so many prior studies failed to detect the genuinely high proportion of the population with the disorder. Lower estimates in some studies than others (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson, Hughes, George and Blazer1994; Stein et al. Reference Stein, Walker and Forde1994, Reference Stein, Walker and Forde1996; Bijl et al. Reference Bijl, van Zessen and Ravelli1998; DeWit et al. Reference DeWit, Ogborne, Offord and MacDonald1999; Wittchen et al. Reference Wittchen, Stein and Kessler1999; Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Henderson and Hall2001; Alonso et al. Reference Alonso, Angermeyer, Bernert, Bruffaerts, Brugha, Bryson, de Girolamo, Graaf, Demyttenaere, Gasquet, Haro, Katz, Kessler, Kovess, Lepine, Ormel, Polidori, Russo, Vilagut, Almanza, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, Autonell, Bernal, Buist-Bouwman, Codony, Domingo-Salvany, Ferrer, Joo, Martinez-Alonso, Matschinger, Mazzi, Morgan, Morosini, Palacin, Romera, Taub and Vollebergh2004; Grant et al. Reference Grant, Hasin, Blanco, Stinson, Chou, Goldstein, Dawson, Smith, Saha and Huang2005) may have resulted from differences in methodology or assessment (e.g. variation in the number and kinds of social situations assessed or in the diagnostic system used) or may reflect genuine differences between countries or cultures in the prevalence of the disorder (Demyttenaere et al. Reference Demyttenaere, Bruffaerts, Posada-Villa, Gasquet, Kovess, Lepine, Angermeyer, Bernert, de Girolamo, Morosini, Polidori, Kikkawa, Kawakami, Ono, Takeshima, Uda, Karam, Fayyad, Karam, Mneimneh, Medina-Mora, Borges, Lara, de Graaf, Ormel, Gureje, Shen, Huang, Zhang, Alonso, Haro, Vilagut, Bromet, Gluzman, Webb, Kessler, Merikangas, Anthony, Von Korff, Wang, Brugha, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Lee, Heeringa, Pennell, Zaslavsky, Ustun and Chatterji2004). Clinical validation studies of the sort included in the NCS-R would be needed to adjudicate between these possibilities.

We found very few cases of social phobia involving just one or two fears. It is possible that the unusually broad range of social fears assessed in the survey enhanced detection of multiple fears in those who might otherwise have been misclassified as more ‘specific’ cases. These different fears were strongly correlated in the total sample and the correlations fit a one-factor model in an exploratory factor analysis. A latent class analysis yielded further evidence of unidimensionality in that the four latent classes obtained were found to be largely nested; that is, successively higher classes were characterized by consistently higher conditional probabilities of almost all social fears. These findings replicate a latent class analysis performed in the NCS (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Stein and Berglund1998) that also found nested latent classes distinguished by number of social fears. Like other community surveys (Furmark et al. Reference Furmark, Tillfors, Stattin, Ekselius and Fredrikson2000; Stein et al. Reference Stein, Torgrud and Walker2000), these results offer little evidence for distinct fear profiles, such as those that have been hypothesized in the literature to involve performance versus interactional situations (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Beidel and Townsley1992; Hook & Valentiner, Reference Hook and Valentiner2002). Although analyses in some clinical samples have found multiple factors underlying social fears, the number and content of the factors has varied considerably across studies (e.g. Safren et al. Reference Safren, Heimberg, Horner, Juster, Schneier and Liebowitz1999; Baker et al. Reference Baker, Heinrichs, Kim and Hofmann2002). Future efforts to reconcile these findings will be ideally carried out in community as well as clinical samples, using a range of measures, to provide a clearer structural picture that is independent of instrumentation, setting, and selection effects.

The current study extends previous findings on co-morbidity in social phobia (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, McGonagle, Zhao, Nelson, Hughes, Eshleman, Wittchen and Kendler1994, Reference Kessler, Stang, Wittchen, Stein and Walters1999; Magee et al. Reference Magee, Eaton, Wittchen, McGonagle and Kessler1996; Sonntag et al. Reference Sonntag, Wittchen, Hofler, Kessler and Stein2000; Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Hinshaw, Kraemer, Lenora, Newcorn, Abikoff, March, Arnold, Cantwell, Conners, Elliott, Greenhill, Hechtman, Hoza, Pelham, Severe, Swanson, Wells, Wigal and Vitiello2001; Sareen et al. Reference Sareen, Chartier, Kjernisted and Stein2001, Reference Sareen, Stein, Cox and Hassard2004, Reference Sareen, Chartier, Paulus and Stein2006; Goodwin & Hamilton, Reference Goodwin and Hamilton2003) by including a wider range of co-morbid conditions and by documenting a significant association of co-morbidity with number of social fears. The associations between social phobia and other anxiety, mood, substance use, and impulse-control disorders may be explained in a number of ways (Kraemer et al. Reference Kraemer, Stice, Kazdin, Offord and Kupfer2001). Social phobia, which so often has its onset in childhood and therefore precedes most other disorders with which it is co-morbid, may be a direct or indirect risk factor for other mental disorders. The few prospective studies that have examined this issue have tended to find that social phobia is a predictor of later-onset depression (Stein et al. Reference Stein, Fuetsch, Muller, Hofler, Lieb and Wittchen2001; Bittner et al. Reference Bittner, Goodwin, Wittchen, Beesdo, Höfler and Lieb2004) and substance use (Zimmermann et al. Reference Zimmermann, Wittchen, Hofler, Pfister, Kessler and Lieb2003). An alternative possibility is that other early-onset mental disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or oppositional-defiant disorder, may increase the likelihood of developing social phobia as well as later disorders. Finally, common causes such as temperament (Kagan et al. Reference Kagan, Reznick and Snidman1988; Rosenbaum et al. Reference Rosenbaum, Biederman, Bolduc-Murphy, Faraone, Chaloff, Hirshfeld and Kagan1993; Stein, Reference Stein1998), personality (Cox et al. Reference Cox, Fleet and Stein2004; Hettema et al. Reference Hettema, Neale, Myers, Prescott and Kendler2006), genetic (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Neale, Kessler, Heath and Eaves1992; Stein et al. Reference Stein, Chartier, Hazen, Kozak, Tancer, Lander, Furer, Chubaty and Walker1998), or environmental (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Davis and Kendler1997; Lieb et al. Reference Lieb, Wittchen, Hofler, Fuetsch, Stein and Merikangas2000; Chartier et al. Reference Chartier, Walker and Stein2001) factors may predispose individuals both to social phobia and to other mental disorders. A shared vulnerability factor of low positive affect (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Chorpita and Barlow1998), for example, may help to explain the extensive co-morbidity of social phobia with unipolar mood disorders in the present sample and in clinical samples (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Campbell, Lehman, Grisham and Mancill2001). There is a need for prospective studies to clarify the associations of social phobia with other disorders and to account for the observed dose–response relationship between number of social fears and the extent of co-morbidity. Studies are also needed to determine whether early intervention for social anxiety might prevent the onset of co-morbid conditions related to primary social phobia (Kendall & Kessler, Reference Kendall and Kessler2002).

As the majority of people with social phobia have co-morbid disorders, it can be asked whether social phobia contributes uniquely to functional impairment. This question is reflected in suggestions by some commentators that social phobia is not associated with ‘harmful dysfunction’ and therefore is not a mental disorder at all (Wakefield et al. Reference Wakefield, Horwitz and Schmitz2005). That particular argument – which has been hotly debated (Campbell-Sills & Stein, Reference Campbell-Sills and Stein2005) – is especially relevant to diagnosable cases with just one or a few social fears, as they fall nearest to the diagnostic threshold and appear less impaired than those with more pervasive fears (Heimberg et al. Reference Heimberg, Hope, Dodge and Becker1990; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Stein and Berglund1998). To help address this issue, the current survey used the Sheehan Disability Scales to assess the impairment caused by social phobia across several domains of functioning. We found that social phobia, even in the absence of co-morbid conditions, is associated with significantly elevated impairment in multiple domains. Importantly, this holds true for social phobia limited to 1–4 fears, underscoring the significance of even these most circumscribed social phobia cases.

At the same time, consistent with previous research (Stein et al. Reference Stein, Torgrud and Walker2000), we found a dose–response relationship between number of social fears and degree of functional impairment. This finding is noteworthy, considering that pure social phobia cases involving a larger number of fears were less likely to receive treatment specifically for this disorder. Together, these data suggest that people who have the greatest need for social phobia treatment are those least likely to receive it. A possible explanation for these results is that individuals with multiple social fears may be more likely to view social anxiety symptoms as untreatable parts of their personality (i.e. shyness; Bruch et al. Reference Bruch, Hamer and Heimberg1995) than those with a limited number of fears. Another explanation is that these individuals may avoid seeking treatment for emotional problems because of fears of negative evaluation by care providers. This latter possibility is contradicted, however, by our finding that most respondents with social phobia had used non-social-phobia-specific mental health services. This finding implies that health care providers may be missing opportunities to treat social phobia. Careful screening for social phobia among patients presenting with other anxiety, mood, substance use, and impulse-control disorders not only may lead to better detection and treatment of social phobia but also may facilitate treatment of the co-morbid disorders.

In conclusion, the current study provides nationally representative data on the prevalence and correlates of social fears and social phobia in the USA. The results are largely consistent with previous epidemiological studies demonstrating that social phobia is prevalent in the community, co-morbid with other mental disorders, and often not treated. Important novel findings include the demonstration that social phobia, even in the non-co-morbid form, is associated with functional impairment; that social phobia is a unidimensional construct with a dose–response relationship between number of fears and degree of impairment; and that there is an inverse relationship between the severity of social phobia and the likelihood of receiving social phobia-specific treatment.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this article was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Career Development Award K01-MH076162 (A.M.R.) and by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator grant (J.S.).

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by NIMH (U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044780), and the John W. Alden Trust. Collaborating NCS-R investigators include Ronald C. Kessler (Principal Investigator, Harvard Medical School), Kathleen Merikangas (Co-Principal Investigator, NIMH), James Anthony (Michigan State University), William Eaton (The Johns Hopkins University), Meyer Glantz (NIDA), Doreen Koretz (Harvard University), Jane McLeod (Indiana University), Mark Olfson (New York State Psychiatric Institute, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University), Harold Pincus (University of Pittsburgh), Greg Simon (Group Health Cooperative), Michael Von Korff (Group Health Cooperative), Philip Wang (Harvard Medical School), Kenneth Wells (UCLA), Elaine Wethington (Cornell University), and Hans-Ulrich Wittchen (Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry, Technical University of Dresden). The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or the US Government. A complete list of NCS publications and the full text of all NCS-R instruments can be found at www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs. Send correspondence to: ncs@hcp.med.harvard.edu.

The NCS-R is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centers for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis. These activities were supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/.

Declaration of Interest

None.