Introduction

Socially anxious individuals are prone to heightened fear, anxiety, and avoidance of social interactions and situations associated with potential scrutiny (Alden and Taylor, Reference Alden and Taylor2004; Heimberg et al., Reference Heimberg, Hofmann, Liebowitz, Schneier, Smits, Stein, Hinton and Craske2014). In addition to heightened negative affect (NA), socially anxious individuals tend to report lower levels of positive affect (PA) (Anderson and Hope, Reference Anderson and Hope2008; Kashdan and Collins, Reference Kashdan and Collins2010; Kashdan et al., Reference Kashdan, Weeks and Savostyanova2011; Geyer et al., Reference Geyer, Fua, Daniel, Chow, Bonelli, Huang, Barnes and Teachman2018). Social anxiety symptoms lie on a continuum and, when extreme, can become debilitating (Lipsitz and Schneier, Reference Lipsitz and Schneier2000; Katzelnick et al., Reference Katzelnick, Kobak, DeLeire, Henk, Greist, Davidson, Schneier, Stein and Helstad2001; Kessler, Reference Kessler2003; Rapee and Spence, Reference Rapee and Spence2004; Craske et al., Reference Craske, Stein, Eley, Milad, Holmes, Rapee and Wittchen2017; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Lim, Roest, de Jonge, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, de Girolamo, Florescu, Gureje, Haro, Harris, He, Hinkov, Horiguchi, Hu, Karam, Karam, Lee, Lepine, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Ten Have, Torres, Viana, Wojtyniak, Xavier, Kessler and Scott2017; Krueger et al., Reference Krueger, Kotov, Watson, Forbes, Eaton, Ruggero, Simms, Widiger, Achenbach, Bach, Bagby, Bornovalova, Carpenter, Chmielewski, Cicero, Clark, Conway, DeClercq, DeYoung, Docherty, Drislane, First, Forbush, Hallquist, Haltigan, Hopwood, Ivanova, Jonas, Latzman, Markon, Miller, Morey, Mullins-Sweatt, Ormel, Patalay, Patrick, Pincus, Regier, Reininghaus, Rescorla, Samuel, Sellbom, Shackman, Skodol, Slade, South, Sunderland, Tackett, Venables, Waldman, Waszczuk, Waugh, Wright, Zald and Zimmerman2018; Conway et al., Reference Conway, Forbes, Forbush, Fried, Hallquist, Kotov, Mullins-Sweatt, Shackman, Skodol, South, Sunderland, Waszczuk, Zald, Afzali, Bornovalova, Carragher, Docherty, Jonas, Krueger, Patalay, Pincus, Tackett, Reininghaus, Waldman, Wright, Zimmerman, Bach, Bagby, Chmielewski, Cicero, Clark, Dalgleish, DeYoung, Hopwood, Ivanova, Latzman, Patrick, Ruggero, Samuel, Watson and Eaton2019; Ruscio, Reference Ruscio2019). Social anxiety disorder is among the most prevalent mental illnesses; contributes to the development of other psychiatric disorders, such as depression; and is challenging to treat (Schneier et al., Reference Schneier, Johnson, Hornig, Liebowitz and Weissman1992; Rodebaugh et al., Reference Rodebaugh, Holaway and Heimberg2004; Acarturk et al., Reference Acarturk, Cuijpers, Van Straten and De Graaf2009; Mathew et al., Reference Mathew, Pettit, Lewinsohn, Seeley and Roberts2011; Neubauer et al., Reference Neubauer, von Auer, Murray, Petermann, Helbig-Lang and Gerlach2013; Craske et al., Reference Craske, Stein, Eley, Milad, Holmes, Rapee and Wittchen2017; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Lim, Roest, de Jonge, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, de Girolamo, Florescu, Gureje, Haro, Harris, He, Hinkov, Horiguchi, Hu, Karam, Karam, Lee, Lepine, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Ten Have, Torres, Viana, Wojtyniak, Xavier, Kessler and Scott2017). Relapse and recurrence are common, and pharmaceutical treatments are associated with significant adverse effects (Bruce et al., Reference Bruce, Yonkers, Otto, Eisen, Weisberg, Pagano, Shea and Keller2005; Rhebergen et al., Reference Rhebergen, Batelaan, de Graaf, Nolen, Spijker, Beekman and Penninx2011; Scholten et al., Reference Scholten, Batelaan, van Balkom, Wjh Penninx, Smit and van Oppen2013, Reference Scholten, Batelaan, Penninx, van Balkom, Smit, Schoevers and van Oppen2016; Gordon and Redish, Reference Gordon, Redish, Redish and Gordon2016; Spinhoven et al., Reference Spinhoven, Batelaan, Rhebergen, van Balkom, Schoevers and Penninx2016; Batelaan et al., Reference Batelaan, Bosman, Muntingh, Scholten, Huijbregts and van Balkom2017). Yet the situational factors that govern the momentary experience and expression of social anxiety in the real world remain incompletely understood. To date, most of what it known is based on either retrospective report or acute laboratory challenges (Alden and Wallace, Reference Alden and Wallace1995; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Davila, Farrow and Grant2006; Buote et al., Reference Buote, Pancer, Pratt, Adams, Birnie-Lefcovitch, Polivy and Wintre2007; Afram and Kashdan, Reference Afram and Kashdan2015; Crişan et al., Reference Crişan, Vulturar, Miclea and Miu2016).

As part of an on-going prospective-longitudinal study focused on individuals at risk for the development of mood and anxiety disorders, we used smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to intensively sample momentary levels of NA and PA in the daily lives of 228 young adults. Subjects were selectively recruited from a pool of 6594 individuals screened for individual differences in dispositional negativity (i.e. negative emotionality), the tendency to experience more intense, frequent, or persistent levels of depression, worry, fear and anxiety – including social anxiety (Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Tromp, Stockbridge, Kaplan, Tillman and Fox2016; Hur et al., Reference Hur, Stockbridge, Fox and Shackman2019). This ‘enrichment’ strategy enabled us to examine a broader spectrum of social anxiety symptoms than alternate approaches, such as convenience sampling. Because EMA data are captured in real time (e.g. Who are you with?), they circumvent the biases that can distort retrospective reports and provide insights into how emotional experience dynamically responds to moment-by-moment changes in social context (Barrett, Reference Barrett1997; Shiffman et al., Reference Shiffman, Stone and Hufford2008; Csikszentmihalyi et al., Reference Csikszentmihalyi, Mehl and Conner2013; Lay et al., Reference Lay, Gerstorf, Scott, Pauly and Hoppmann2017). We focused on young adulthood because it is a time of profound, often stressful developmental transitions (e.g. moving away from home, forging new social relationships; Hays and Oxley, Reference Hays and Oxley1986; Alloy and Abramson, Reference Alloy and Abramson1999; Arnett, Reference Arnett2000; Pancer et al., Reference Pancer, Hunsberger, Pratt and Alisat2000). In fact, more than half of undergraduate students report overwhelming anxiety, with many experiencing the first onset or a recurrence of anxiety and mood disorders during this period (Auerbach et al., Reference Auerbach, Alonso, Axinn, Cuijpers, Ebert, Green, Hwang, Kessler, Liu, Mortier, Nock, Pinder-Amaker, Sampson, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Andrade, Benjet, Caldas-de-Almeida, Demyttenaere, Florescu, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, Karam, Kiejna, Kovess-Masfety, Lee, McGrath, O'Neill, Pennell, Scott, Ten Have, Torres, Zaslavsky, Zarkov and Bruffaerts2016, Reference Auerbach, Mortier, Bruffaerts, Alonso, Benjet, Cuijpers, Demyttenaere, Ebert, Green, Hasking, Murray, Nock, Pinder-Amaker, Sampson, Stein, Vilagut, Zaslavsky, Kessler and Collaboratorsin press; American College Health Association, 2016; Global Burden of Disease Collaborators, 2016; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Lim, Roest, de Jonge, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, de Girolamo, Florescu, Gureje, Haro, Harris, He, Hinkov, Horiguchi, Hu, Karam, Karam, Lee, Lepine, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Ten Have, Torres, Viana, Wojtyniak, Xavier, Kessler and Scott2017; Lipson et al., Reference Lipson, Lattie and Eisenberg2018). Those with elevated levels of social anxiety tend to experience substantial distress and impairment and are more likely to develop psychopathology (Merikangas et al., Reference Merikangas, Avenevoli, Acharyya, Zhang and Angst2002).

We were particularly interested in understanding how the momentary emotional experience of socially anxious individuals varies as a function of social context. Emotion is profoundly social (Fox and Shackman, Reference Fox, Shackman, Fox, Lapate, Shackman and Davidson2018). Emotional experiences are routinely shared and dissected with friends, family, and romantic partners (Rime, Reference Rime2009). Humans and other primates routinely seek the company of close companions in response to stressors, and increased social engagement promotes positive affect (Cottrell and Epley, Reference Cottrell, Epley, Suls and Miller1977; Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Weinstein, Hudja, Bloomer, Barstead, Fox and Lemay2018). Indeed, there is abundant evidence that close companions play a critical role in coping with stress and regulating negative affect (Bolger and Eckenrode, Reference Bolger and Eckenrode1991; Myers, Reference Myers, Kahneman, Diener and Schwartz1999; Wade and Kendler, Reference Wade and Kendler2000; Buote et al., Reference Buote, Pancer, Pratt, Adams, Birnie-Lefcovitch, Polivy and Wintre2007; Marroquin, Reference Marroquin2011; Zaki and Williams, Reference Zaki and Williams2013; Kendler and Gardner, Reference Kendler and Gardner2014; Coan and Sbarra, Reference Coan and Sbarra2015; Ramsey and Gentzler, Reference Ramsey and Gentzler2015; Reeck et al., Reference Reeck, Ames and Ochsner2016). Many of these beneficial effects appear to be disrupted in socially anxious individuals (Alden and Taylor, Reference Alden and Taylor2004).

We began by testing whether social anxiety is associated with the amount of time allocated to different social contexts (e.g. with close companions) and whether this reflects the number of self-reported confidants. Social avoidance is diagnostic of social anxiety disorder, is a key component of dimensional measures of social anxiety, and contributes to functional impairment and reduced quality of life (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Beidel, Dancu and Keys1986; Liebowitz, Reference Liebowitz1987; Beidel et al., Reference Beidel, Turner and Morris1999; Strahan and Conger, Reference Strahan and Conger1999; APA, 2013). Among community samples, adults with elevated levels of social anxiety are less likely to have a close friend and more likely to be unmarried by mid-life (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Hughes, George and Blazer1994). They are also more likely to be lonely (Lim et al., Reference Lim, Rodebaugh, Zyphur and Gleeson2016). Recent work using unobtrusive, smartphone-based global positioning system (GPS) data provides additional evidence suggestive of social inhibition and avoidance (Boukhechba et al., Reference Boukhechba, Chow, Fua, Teachman and Barnes2018), demonstrating that socially anxious university students spend significantly less time at ‘leisure’ (e.g. gymnasiums, pubs, cinemas, and coffee shops) and ‘food’ (e.g. restaurants, food courts, and dining halls) locations during peak hours in the evening. Socially anxious students also spent more time at home or off-campus (e.g. parents’ home), particularly on weekends, and visited fewer locations overall, suggesting a more restricted range of activities (see also Chow et al., Reference Chow, Fua, Huang, Bonelli, Xiong, Barnes and Teachman2017). Whether this pattern reflects generalized avoidance, specific avoidance of socially ‘distant’ individuals (e.g. strangers, acquaintances), or a lack of confidants remains unknown.

Next, we used a series of multilevel models (MLMs) to understand the interactive effects of social anxiety and the social environment on momentary affect. This enabled us to test whether socially anxious individuals experience heightened NA and attenuated PA in the presence of distant others, as one would expect based on laboratory studies of interactions with unfamiliar peers and researchers (Meleshko and Alden, Reference Meleshko and Alden1993; Creed and Funder, Reference Creed and Funder1998; Coles et al., Reference Coles, Turk and Heimberg2002; Kashdan and Roberts, Reference Kashdan and Roberts2004, Reference Kashdan and Roberts2006, Reference Kashdan and Roberts2007; Heerey and Kring, Reference Heerey and Kring2007; Kashdan et al., Reference Kashdan, Ferssizidis, Farmer, Adams and McKnight2013b; Crişan et al., Reference Crişan, Vulturar, Miclea and Miu2016). This expectation is reinforced by evidence from EMA studies that children with social anxiety disorder experience diminished PA in the presence of distant others (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Lee, Wright, Gilchrist, Forbes, McMakin, Dahl, Ladouceur, Ryan and Silk2017). Whether this pattern is also evident in adults remains unknown.

Using a MLM approach, we also tested two competing predictions about the consequences of close companions. One possibility is that socially anxious individuals derive increased emotional benefits (e.g. lower levels of NA) from close companions. Consistent with this view, the presence of a friend has been shown to normalize behavioral signs of anxiety and reduce negative self-thoughts in socially anxious adults exposed to an experimental speech challenge (Pontari, Reference Pontari2009). Likewise, diary studies suggest that spousal support plays a key role in dampening negative affect among patients with social anxiety disorder (Zaider et al., Reference Zaider, Heimberg and Iida2010) and EMA studies show that the presence of close companions is associated with disproportionately enhanced PA in children with social anxiety disorder (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Lee, Wright, Gilchrist, Forbes, McMakin, Dahl, Ladouceur, Ryan and Silk2017) and adults with elevated levels of dispositional negativity (Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Weinstein, Hudja, Bloomer, Barstead, Fox and Lemay2018). In fact, a variety of work suggests that individuals with low levels of psychological well-being and patients with depression reap larger emotional benefits from positive daily events (Rottenberg, Reference Rottenberg2017; Lamers et al., Reference Lamers, Swendsen, Cui, Husky, Johns, Zipunnikov and Merikangas2018). Although socially anxious adults often show symptoms of depression and anhedonia, it is unclear whether similar benefits extend to this population.

A competing possibility is that socially anxious individuals fail to capitalize on available socio-emotional support. Indeed, socially anxious individuals tend to be less emotionally expressive, disclosing, and intimate with companions (Vernberg et al., Reference Vernberg, Abwender, Ewell and Beery1992; Meleshko and Alden, Reference Meleshko and Alden1993; Sparrevohn and Rapee, Reference Sparrevohn and Rapee2009; Cuming and Rapee, Reference Cuming and Rapee2010; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Morelli, Ong and Zaki2018). They perceive themselves as receiving less social support (La Greca and Lopez, Reference La Greca and Lopez1998; Torgrud et al., Reference Torgrud, Walker, Murray, Cox, Chartier and Kjernisted2004; Cuming and Rapee, Reference Cuming and Rapee2010); perceive their friendships to be of a lower quality (Rodebaugh, Reference Rodebaugh2009; Rodebaugh et al., Reference Rodebaugh, Lim, Shumaker, Levinson and Thompson2015); are less satisfied with friends, family, and romantic partners (Stein and Kean, Reference Stein and Kean2000; Starr and Davila, Reference Starr and Davila2008; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Sarver and Beidel2012); and are prone to emotional neediness and overreliance (Davila and Beck, Reference Davila and Beck2002; Darcy et al., Reference Darcy, Davila and Beck2005). Perhaps as a consequence, socially anxious individuals report elevated levels of interpersonal conflict (Cuming and Rapee, Reference Cuming and Rapee2010) and many patients show profound impairment of interpersonal relationships (Wittchen et al., Reference Wittchen, Fuetsch, Sonntag, Müller and Liebowitz2000; Rapaport et al., Reference Rapaport, Clary, Fayyad and Endicott2005; Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Cisler and Tolin2007; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Lim, Roest, de Jonge, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, de Girolamo, Florescu, Gureje, Haro, Harris, He, Hinkov, Horiguchi, Hu, Karam, Karam, Lee, Lepine, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Ten Have, Torres, Viana, Wojtyniak, Xavier, Kessler and Scott2017). Taken together, these observations motivate the prediction that socially anxious individuals derive smaller emotional benefits or even costs (e.g. higher levels of NA) from close companions.

Discovering the situational factors associated with the real-world experience of social anxiety is important. The identification of potentially modifiable targets, such as social context, has the potential to guide the development of improved intervention strategies.

Method

Overview

As part of an on-going prospective-longitudinal study focused on individuals at risk for the development of internalizing disorders, we used well-established measures of dispositional negativity (often termed neuroticism or negative emotionality; Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Tromp, Stockbridge, Kaplan, Tillman and Fox2016; Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Weinstein, Hudja, Bloomer, Barstead, Fox and Lemay2018) to screen 6594 young adults (57.1% female; 59.0% White, 19.0% Asian, 9.9% African American, 6.3% Hispanic, 5.8% Multiracial/Other; M = 19.2 years, s.d. = 1.1 years). Screening data were stratified into quartiles (top quartile, middle quartiles, bottom quartile) separately for males and females. Individuals who met preliminary inclusion criteria were independently recruited from each of the resulting six strata. Approximately half the subjects were recruited from the top quartile, with the remainder split between the middle and bottom quartiles (i.e. 50% high, 25% medium, and 25% low). Given the typically robust relations between measures of dispositional negativity and social anxiety – R 2 = 0.25 in the present sample – this ‘enrichment’ strategy allowed us to examine a relatively wide range of social anxiety symptoms without gaps or discontinuities. All subjects were first-year university students in good physical health with consistent access to a smartphone. All reported the absence of a lifetime psychotic, bipolar, neurological, or developmental disorder. Given the focus of the larger prospective-longitudinal study on risk for the development of mental illness, all subjects reported the absence of current alcohol/substance abuse, suicidal ideation, internalizing disorder (past 2 months), and psychiatric treatment. To maximize the range of psychiatric risk, subjects with a lifetime history of anxiety and mood disorders were not excluded, as in prior studies of high-risk populations (Alloy et al., Reference Alloy, Abramson, Hogan, Whitehouse, Rose, Robinson, Kim and Lapkin2000). At the baseline laboratory session, subjects provided informed written consent, were familiarized with the EMA protocol (see below), and completed the social anxiety and social network assessments. Beginning the next day, subjects completed up to 8 EMA surveys/day for 7 days. All procedures were approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board. The sample does not overlap with that detailed in prior work by our group (Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Weinstein, Hudja, Bloomer, Barstead, Fox and Lemay2018).

Subjects

Two-hundred and forty-two subjects completed both the baseline assessment and EMA protocol. Fourteen subjects were excluded from analyses: 2 withdrew and 12 (~5%) failed to complete >39 survey prompts (70% compliance). The final sample included 228 subjects (51.3% female; 62.7% White, 17.5% Asian, 8.3% African American, 4.9% Hispanic, 6.6% Multiracial/Other; M = 18.76 years, s.d. = 0.35 years).

Power analysis

Sample size was determined a priori as part of the application for the award that supported this research (R01-MH107444). The target sample size (N ≈ 240) was chosen to afford acceptable power and precision given available resources (Schönbrodt and Perugini, Reference Schönbrodt and Perugini2013). At the time of study design, G-power 3.1.9.2 (http://www.gpower.hhu.de) indicated >99% power to detect a benchmark medium-sized effect (r = 0.30) with up to 20% planned attrition (N = 192 usable datasets) using α = 0.05 (two-tailed).

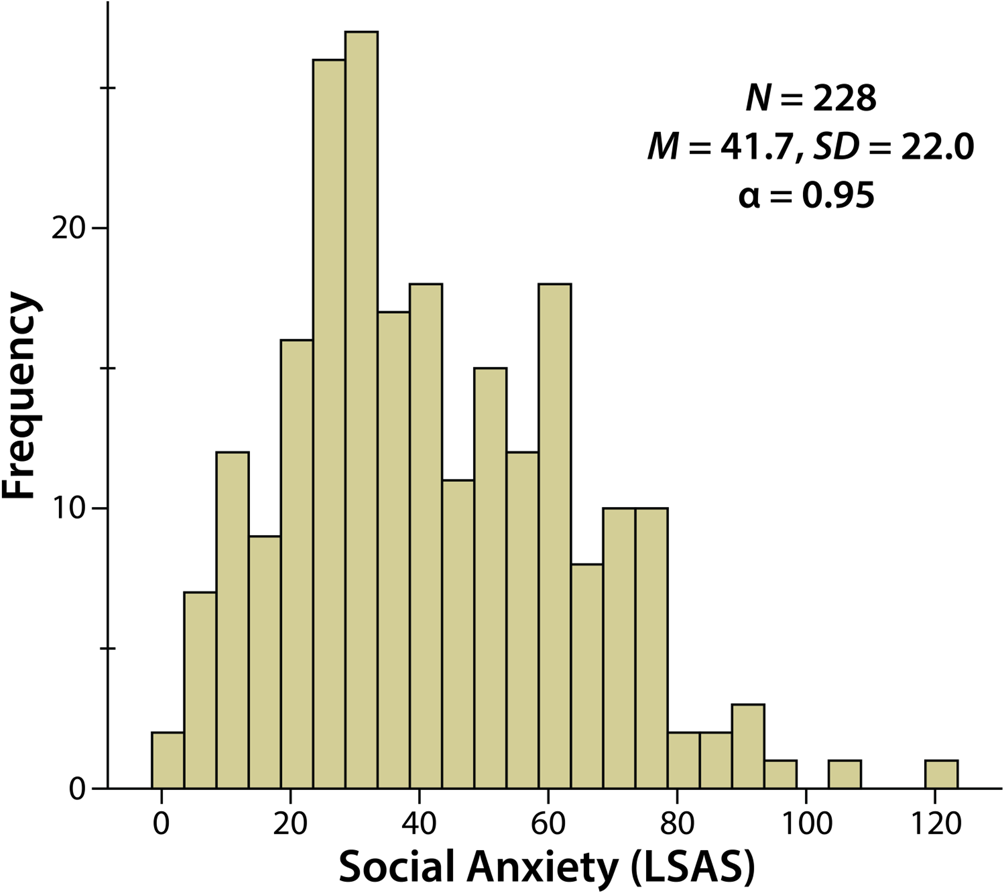

Social anxiety

At baseline, the self-report version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) was used to quantify social anxiety (Liebowitz, Reference Liebowitz1987). Subjects used a 0 (none) to 3 (severe) scale to rate the amount of fear and anxiety they typically experience in response to 24 everyday situations (e.g. going to a party, meeting strangers, returning goods to a store, speaking up at meeting). They used a 0 (never) to 3 (usually) rating scale to rate the frequency of avoiding the 24 situations. Social anxiety was quantified by summing the 48 responses. As shown in Fig. 1, LSAS scores were approximately normally distributed (M = 41.7, s.d. = 22.0, Range = 1–121, α = 0.95) and somewhat higher than that previously reported in large university convenience samples (N = 856, M = 34.7, s.d. = 20.4; Russell and Shaw, Reference Russell and Shaw2009)Footnote 1, Footnote 2Footnote †.

Fig. 1. Social anxiety. Social anxiety was assessed at baseline using the self-report version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS). The two highest cases were not excluded because they are sensible – given the nature of the scale and the sample – and because they did not exert undue statistical leverage (Hoaglin et al., Reference Hoaglin, Iglewicz and Tukey1986; Hoaglin and Iglewicz, Reference Hoaglin and Iglewicz1987). Exploratory analyses indicated that the exclusion of these cases did not meaningfully alter the results (not reported).

Social network size

At baseline, the self-reported number of close companions was measured using an item (How many people do you know where you have a close, confiding relationship and can share your most private feelings?) from the modified Kendler Social Support Inventory (MKSSI; Spoozak et al., Reference Spoozak, Gotman, Smith, Belanger and Yonkers2009). Single-item measures of social network size are routinely used in epidemiology research (e.g. Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Myers and Prescott2005; Van Lente et al., Reference Van Lente, Barry, Molcho, Morgan, Watson, Harrington and McGee2012; Kocalevent et al., Reference Kocalevent, Berg, Beutel, Hinz, Zenger, Harter, Nater and Brahler2018). The resulting descriptive statistics (M = 5.6, s.d. = 4.1, Range = 0–30) are broadly consistent with the results of past work focused on confidant networks in university students (Sarason et al., Reference Sarason, Levine, Basham and Sarason1983; Freberg et al., Reference Freberg, Adams, McGaughey and Freberg2010) and friendship networks in community-dwelling adults (Wang and Wellman, Reference Wang and Wellman2010).

EMA procedures

SurveySignal (Hofmann and Patel, Reference Hofmann and Patel2015) was used to automatically deliver 8 text messages/day to each subject's smartphone. On weekdays, messages were delivered every 1.5 to 3 h (M = 115 min, s.d. = 25) between 8:30 AM and 10:30 PM. As in prior work by our group (Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Weinstein, Hudja, Bloomer, Barstead, Fox and Lemay2018), weekday messages were delivered during the ‘passing periods’ between regularly scheduled university courses to maximize compliance. On weekends, messages were delivered every 1.5 to 2.5 h (M = 99 min, s.d. = 17) between 11:00 AM and 11:00 PM. Messages were delivered according to a fixed schedule that varied across days (e.g. the third message was delivered at 12:52 PM on Mondays and 12:16 PM on Tuesdays). Messages contained a link to a secure on-line survey. Subjects were instructed to respond within 30 min (Latency: Median = 2 min, s.d. = 7 min, Interquartile Range = 9 min) and to refrain from responding at unsafe or inconvenient moments (e.g. while driving). A reminder was sent when subjects failed to respond within 15 min. During the baseline laboratory session, several well-established procedures were used to maximize compliance (Palmier-Claus et al., Reference Palmier-Claus, Myin-Germeys, Barkus, Bentley, Udachina, Delespaul, Lewis and Dunn2011), including: (1) delivering a test message in the laboratory and confirming that the subject was able to successfully complete the on-line EMA survey, (2) 24/7 technical support, and (3) monetary bonuses. Base compensation was $10, with $20 bonuses for ⩾70% and ⩾80% compliance, respectively (Total = $10–$50). In the final sample, EMA compliance was acceptable (M = 87.9%, s.d. = 6.2%, Minimum = 71.4%, Total = 11 224) and unrelated to social anxiety, p = 0.77.

EMA survey

Current NA (afraid, nervous, worried, hopeless, sad) and PA (calm, cheerful, content, enthusiastic, joy, relaxed) at the time of the survey prompt was rated using a 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) scale. Subjects also indicated their current social context (‘At the time of ping, who was around?’): alone, close friend(s), family, friend(s), romantic partner, acquaintance(s), co-worker(s), and/or stranger(s). Composite measures of NA and PA were computed by averaging the relevant items (αs > 0.92). To enable follow-up assessments of generality, composite anxiety (afraid, nervous, worried) and depression (hopeless, sad) facet scales were computed (αs > 0.88). Building on prior work by our group and others (Diener and Seligman, Reference Diener and Seligman2002; Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Weinstein, Hudja, Bloomer, Barstead, Fox and Lemay2018), friends, close friends, family, and romantic partners were re-coded as ‘Close’ companions. Acquaintances, co-workers, and strangers were re-coded as ‘Distant’ companions. This approach is conceptually similar to the distinction between ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ social connections (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1973). Analyses indicated that assessments completed in the presence of a mixture of Close and Distant companions (8%) showed intermediate effects and are omitted from the present report.

Analytic strategy

The overarching aim of the present study was to understand the joint explanatory influence of Social Anxiety (LSAS) and Social Context (EMA) on real-world Affect (EMA-derived NA, PA). In all cases, hypothesis testing employed a continuous measure of Social Anxiety.

We began by testing whether variation in Social Anxiety prospectively predicts the aggregate amount of time allocated to different social contexts. A standard multivariate mediation framework was then used to test whether relations between Social Anxiety and Social Context were statistically attributable, at least in part, to variation in Social Network Size (e.g. elevated social anxiety → fewer confidants → less time with close companions) (Hayes, Reference Hayes2017), where Size was indexed using the MKSSI. As in prior work by our group (Stout et al., Reference Stout, Shackman, Pedersen, Miskovich and Larson2017), the significance of the indirect effect (‘mediation’) was assessed using non-parametric bootstrapping (5000 samples). Although the mediation framework provides useful information, it rests on strong assumptions and positive results do not license causal inferences (Bullock et al., Reference Bullock, Green and Ha2010; Green et al., Reference Green, Ha and Bullock2010). Pirateplots were created using the yaRrr package for R (Phillips, Reference Phillips2017). Hotelling's test for dependent correlations was computed using FZT (https://psych.unl.edu/psycrs/statpage/comp.html).

Next, a series of MLMs was implemented in SPSS (version 24.0.0.0) with momentary assessments of Affect and Social Context nested within subjects and intercepts free to vary across subjects. Separate MLMs were computed for NA and PA. Level 2 variables (i.e. Social Anxiety) were mean centered.

The equations defined below outline the basic structure of our final MLMs in standard notation (Raudenbush and Bryk, Reference Raudenbush and Bryk2002). At the first level, Affect during EMA t for individual i was modeled as a function of Social Context:

Alone served as the dummy-coded reference category for primary analyses (as in Equation 1). Distant companions served as the reference category for follow-up analysesFootnote 3.

At the second level, the association between Social Context and Affect was modeled as a function of individual differences in Social Anxiety:

Conceptually, this enabled us to test prospective relations between Social Anxiety and Affect, cross-sectional relations between EMA-derived measures of Social Context and Affect, and the potentially interactive effects of Social Anxiety and Social Context. We also explored the impact of incorporating variation in the amount of time allocated to different contexts as a nuisance variable. For significant effects, we examined generality across NA facets (i.e. anxious and depressed mood). As an additional validity check, we confirmed that similar results were obtained when two authors independently analyzed the data using SPSS (J.H.) and R (M.G.B.), respectively.

Results

Momentary emotional experience covaries with social context

Consistent with other work in young adults (Larson, Reference Larson1990; Berry and Hansen, Reference Berry and Hansen1996; Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Weinstein, Hudja, Bloomer, Barstead, Fox and Lemay2018), our sample spent slightly more than half their time with others (Close = 44.1%, Distant = 13.4%, Alone = 42.5%), although there were marked individual differences in the amount of time devoted to each social environment (Fig. 2). Individuals who spent more time with close others reported lower average levels of NA (r = −0.14, p = 0.03) and higher average levels of PA (r = 0.31, p < 0.000). Conversely, those who spent more time alone reported higher average levels of NA (r = 0.14, p = 0.03) and lower average levels of PA (r = −0.28, p < 0.001), replicating past work (e.g. Diener and Seligman, Reference Diener and Seligman2002; Oishi et al., Reference Oishi, Diener and Lucas2007; Diener et al., Reference Diener, Seligman, Choi and Oishi2018; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Updegraff, Iida, Dishion, Doane, Corbin, Van Lenten and Ha2018; Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Weinstein, Hudja, Bloomer, Barstead, Fox and Lemay2018). The average amount of time spent with distant others was unrelated to average mood (ps > 0.20). In sum, individuals who spend more time with close companions report modestly enhanced mood, whereas those who are prone to seclusion show the opposite effect.

Fig. 2. Percentage of usable momentary assessments acquired in the presence of close companions, distant companions, or alone. Figure depicts the data (jittered gray points; individual participants), density distribution (colored bean plots), Bayesian 95% highest density interval (HDI; white bands), and mean (black bars) for each social context. HDIs permit population-generalizable visual inferences about mean differences and were estimated using 1000 samples from a posterior Gaussian distribution.

Socially anxious individuals spend less time with close companions and have smaller confidant networks

On average, individuals with higher levels of social anxiety spent significantly less time in the company of close companions (r = −0.16, p = 0.01) and showed a trend to spend more time alone (r = 0.13, p = 0.06), consistent with prior work (Alden and Taylor, Reference Alden and Taylor2004; Afram and Kashdan, Reference Afram and Kashdan2015). A mediation analysis suggested that this reflects reduced access to close companions. As shown in Fig. 3, individuals with higher levels of social anxiety report fewer confidants (a = −0.19, p = 0.005), which is also consistent with prior work (Montgomery et al., Reference Montgomery, Haemmerlie and Edwards1991; Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Hughes, George and Blazer1994; La Greca and Lopez, Reference La Greca and Lopez1998). In turn, individuals with fewer confidants were less likely to be in the presence of close companions (b = 0.31, p < 0.001) at the time of momentary assessmentFootnote 4. Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effect excluded zero, indicating significant mediation. Likewise, the direct effect of social anxiety on the amount of time spent with close companions was no longer significant after accounting for variation in the number of confidants (c′ path in Fig. 3; p > 0.10)Footnote 5. Interestingly, social anxiety was not significantly related to the amount of time spent with distant companions (p = 0.20), contraindicating a general bias to avoid others. The association between social anxiety and the amount of time allocated to close companions was significantly stronger than that with distant companions, t Hotelling = 2.18, p = 0.03.

Fig. 3. The negative association between social anxiety and the amount of time with close companions is significantly explained by reduced access to confidants. Figure depicts the corresponding mediation model. Path labels indicate standardized regression coefficients, with c′ indicating the coefficient while controlling for variation in the self-reported number of confidants. Socially anxious individuals report fewer confidants, and individuals with fewer confidants were, in turn, less likely to be in the presence of close companions at the time of momentary assessment.

Social anxiety is associated with diminished real-world emotional experience

MLM analyses demonstrated that social anxiety is associated with reduced quality of real-world emotional experience. Individuals with higher levels of social anxiety report significantly increased NA (t = 25.2, b = 0.12, s.e. = 0.005, p < 0.001) and reduced PA (t = −24.1, b = −0.19, s.e. = 0.008, p < 0.001), consistent with past research (Kashdan, Reference Kashdan2004; Kashdan and Steger, Reference Kashdan and Steger2006; Kashdan et al., Reference Kashdan, Farmer, Adams, Ferssizidis, McKnight and Nezlek2013a, Reference Kashdan, Ferssizidis, Farmer, Adams and McKnight2013b)Footnote 6.

The quality of momentary emotional experience covaries with the presence of close companions

Relative to seclusion or the presence of distant others, MLM results showed that close companions are associated with lower levels of NA (Alone: t = −0.7.51, b = −0.09, s.e. = 0.012, p < 0.001; Distant: t = −6.71, b = −0.10, s.e. = 0.015, p < 0.001) and higher levels of PA (Alone: t = 15.79, b = 0.31, s.e. = 0.019, p < 0.001; Distant: t = 15.03, b = 0.37, s.e. = 0.025, p < 0.001). Relative to seclusion, distant companions are associated with lower levels of PA (PA: t = −2.59, b = −0.06, s.e. = 0.024, p = 0.01; NA:p > 0.30). Results were similar when controlling for variation in the amount of time allocated to different social contexts (online Supplementary Table S1). These findings reinforce the conclusion that the quality of momentary emotional experience is positively associated with the presence of close friends, family, and romantic partners.

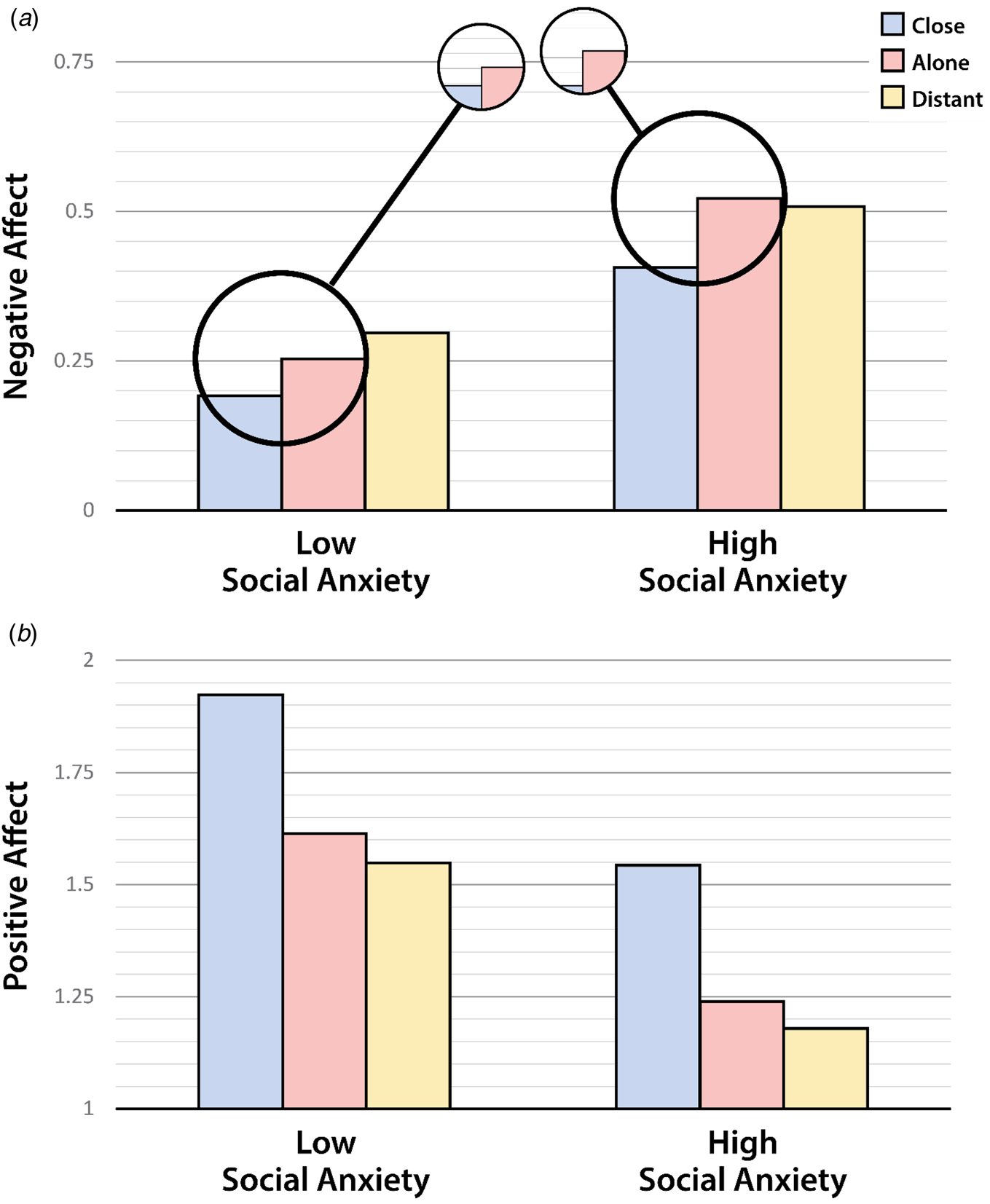

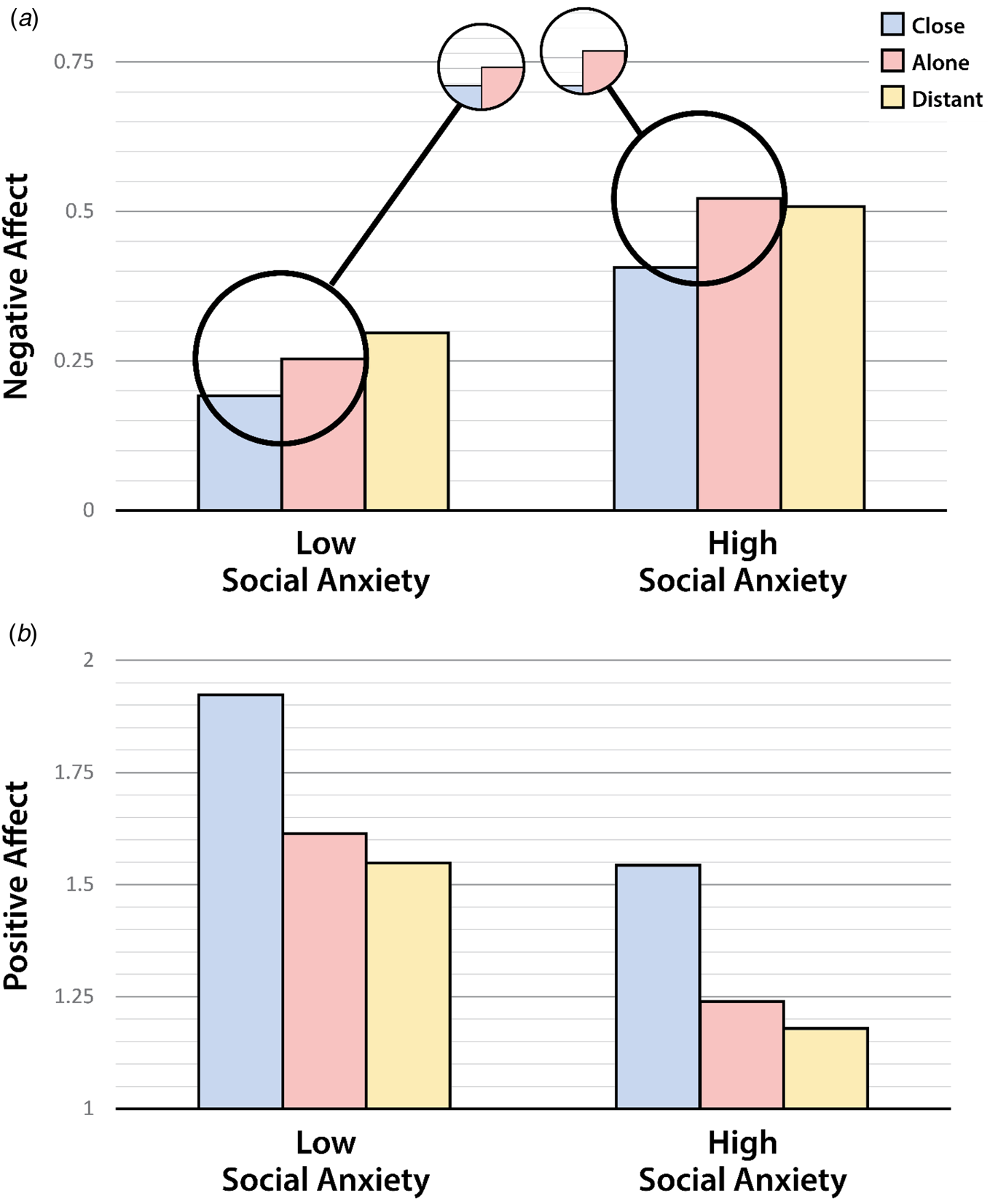

Socially anxious individuals derive larger emotional benefits from close companions

We next considered the joint impact of social anxiety and social context on momentary mood (Table 1). As shown in the upper panel of Fig. 4, the results of this more comprehensive MLM revealed that socially anxious individuals derive larger emotional benefits – indexed by significantly lower levels of NA – from close companions relative to seclusion (Social Anxiety × Close-Alone, t = −2.27, b = −0.03, s.e. = 0.012, p = 0.02). In short, individuals with higher levels of social anxiety tend to experience the least intense, most normative levels of NA in the company of friends, family, and romantic partners. This effect remained significant after controlling for the amount of time allocated to different social contexts (online Supplementary Table S2)Footnote 7. Other interactions were not significant for NA or PA (p > 0.80). Social anxiety was not associated with an exaggerated emotional response in the presence of co-workers, strangers, and other distant companions (Fig. 4 and Table 1). The same general pattern of results was evident for analyses focused on the anxious and depressed facets of momentary NA (online Supplementary Tables S3 and S4).

Table 1. The impact of social anxiety and social context on momentary emotional experience

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Fig. 4. The deleterious impact of social anxiety on momentary emotional experience depends on social context. Individuals with higher levels of social anxiety derive larger emotional benefits – larger decrements in negative affect (NA) – from close companions relative to being alone as shown in the upper panel. Hypothesis testing relied on a continuous measure of social anxiety. For illustrative purposes, predicted values derived from multilevel modeling are depicted for extreme levels (±1 s.d.) of social anxiety.

Discussion

Social anxiety lies on a continuum, from mild to debilitating, and young adults with elevated symptoms of social anxiety are more likely to show significant impairment and develop frank psychopathology. The present study provides new insights into the ways in which real-world emotional experience varies as a function of social anxiety and the social environment. Our results demonstrate that the presence of close companions is associated with lower levels of momentary NA (Fig. 4), including anxiety and depression. Importantly, individuals with higher levels of social anxiety were found to spend significantly less time with close companions and a mediation analysis suggested that this association is partially explained by smaller confidant networks (Fig. 3). Social anxiety was unrelated to the number of assessments completed in the presence of co-workers, strangers, and other distant companions, contraindicating a general social avoidance bias. Although social anxiety at baseline was prospectively associated with a diminished quality of momentary emotional experience (i.e. increased NA and reduced PA), MLM analyses demonstrated that individuals with higher levels of social anxiety derive significantly larger benefits – manifesting as lower levels of NA, anxiety, and depression – from the company of close companions (Fig. 4). In contrast, socially anxious individuals were not disproportionately sensitive to the presence of distant companions (Table 1 and Fig. 4). Indeed, they showed similarly high levels of NA when they were alone. Although social anxiety research and treatment has predominantly focused on responses to novelty and potential threat, our results underscore the centrality of friends, family, and romantic partners. These findings provide a framework for understanding the deleterious consequences of extreme social anxiety and guiding the development of improved interventions.

The present findings extend developmental and laboratory research highlighting the importance of social and interpersonal processes for emotion regulation and mental wellbeing (Maresh et al., Reference Maresh, Beckes and Coan2013; Zaki and Williams, Reference Zaki and Williams2013; Coan and Sbarra, Reference Coan and Sbarra2015; Reeck et al., Reference Reeck, Ames and Ochsner2016; Rubin et al., Reference Rubin, Barstead, Smith, Bowker, Pérez-Edgar and Fox2018). Our observations motivate the hypothesis that the pervasive NA characteristic of socially anxious young adults partially reflects difficulties forming or maintaining close relationships, consistent with work focused on children and adolescents at risk for developing social anxiety disorder (Ladd et al., Reference Ladd, Kochenderfer-Ladd, Eggum, Kochel and McConnell2011; Frenkel et al., Reference Frenkel, Fox, Pine, Walker, Degnan and Chronis-Tuscano2015; Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Tromp, Stockbridge, Kaplan, Tillman and Fox2016; Markovic and Bowker, Reference Markovic and Bowker2017; Rubin et al., Reference Rubin, Barstead, Smith, Bowker, Pérez-Edgar and Fox2018). With fewer confidants, socially anxious individuals spend significantly less time with close companions and are less frequent beneficiaries of their mood-enhancing effects (Figs 3 and 4). Socially anxious individuals appear to have an intact capacity for social mood enhancement. Indeed, they show lower levels of NA in the company of close companions, in broad accord with work focused on depressed samples (Rottenberg, Reference Rottenberg2017). This perspective is also well aligned with evidence from prospective longitudinal studies indicating that close friendships and other kinds of social support and intimacy reduce the risk of developing anxiety symptoms in adolescence and early adulthood (Teachman and Allen, Reference Teachman and Allen2007; Rodebaugh, Reference Rodebaugh2009; Tillfors et al., Reference Tillfors, Persson, Willen and Burk2012; Frenkel et al., Reference Frenkel, Fox, Pine, Walker, Degnan and Chronis-Tuscano2015; Narr et al., Reference Narr, Allen, Tan and Loeb2019). Likewise, among patients undergoing treatment for social anxiety, higher levels of perceived social support are associated with a more favorable prognosis (Rapee et al., Reference Rapee, Peters, Carpenter and Gaston2015).

Naturally, our results do not license causal inferences. We cannot rule out the possibility that reduced access to confidants begets higher levels of social anxiety or, more likely, that these two constructs exert bi-directional effects (Rubin et al., Reference Rubin, Barstead, Smith, Bowker, Pérez-Edgar and Fox2018). Likewise, it could be that socially anxious individuals actively seek out the company of close companions when they are experiencing lower levels of NA. Nevertheless, randomized laboratory studies reinforce the conclusion that close companions play a key role in mitigating NA. For example, the presence of a close companion has been shown to normalize negative affect and catastrophic cognitions (‘I'm going to die’) in anxiety patients exposed to a panic-inducing CO2 challenge (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Hollon, Carson and Shelton1995) and to normalize behavioral signs of anxiety in socially anxious young adults during a videotaped speech challenge (Pontari, Reference Pontari2009). Taken with the present results, these observations motivate the hypothesis that friends, romantic partners, and family members serve as a regulatory ‘prosthesis’ for socially anxious individuals.

Relying on close companions is risky. This is particularly true for socially anxious individuals, who tend to experience elevated levels of interpersonal conflict (Cuming and Rapee, Reference Cuming and Rapee2010) and, among patients, marked impairment of interpersonal relationships (Wittchen et al., Reference Wittchen, Fuetsch, Sonntag, Müller and Liebowitz2000; Rapaport et al., Reference Rapaport, Clary, Fayyad and Endicott2005; Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Cisler and Tolin2007; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Lim, Roest, de Jonge, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, de Girolamo, Florescu, Gureje, Haro, Harris, He, Hinkov, Horiguchi, Hu, Karam, Karam, Lee, Lepine, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Ten Have, Torres, Viana, Wojtyniak, Xavier, Kessler and Scott2017). Relationship distress and dissolution reduces or eliminates the possibility of interpersonal emotion regulation and, ultimately, can contribute to the development, maintenance, and recurrence of psychopathology (Rehman et al., Reference Rehman, Gollan and Mortimer2008; Marroquin, Reference Marroquin2011; Whisman and Baucom, Reference Whisman and Baucom2012; Baucom et al., Reference Baucom, Belus, Adelman, Fischer and Paprocki2014). Even in the absence of relationship problems, as young adults transition to full-time employment, marriage, and parenting, social network size naturally begins to decline and more time is spent with distant companions or alone (Larson, Reference Larson1990; Lansford et al., Reference Lansford, Sherman and Antonucci1998; Wrzus et al., Reference Wrzus, Hanel, Wagner and Neyer2013, Reference Wrzus, Wagner and Riediger2016; Sander et al., Reference Sander, Schupp and Richter2017) – effects that may be amplified in more recent cohorts, which tend to allocate less time to face-to-face social interaction and experience elevated levels of loneliness (Twenge et al., Reference Twenge, Spitzberg and Campbell2019). Many middle-aged and older adults report that they have no confidant (McPherson and Smith-Lovin, Reference McPherson and Smith-Lovin2006), depriving them of the emotional benefits of close companions. This is likely to be exacerbated among individuals with elevated levels of social anxiety, who are less likely to have close friends and more likely to be unmarried by mid-life (Montgomery et al., Reference Montgomery, Haemmerlie and Edwards1991; Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Hughes, George and Blazer1994; La Greca and Lopez, Reference La Greca and Lopez1998). Extending the present approach to earlier and later developmental periods is an important challenge for future research, and prospective-longitudinal studies are likely to be especially fruitful.

Social anxiety is often cast as an increased sensitivity to scrutiny from others, especially unfamiliar others, which manifests as heightened avoidance, fear (‘phobia’), and anxiety (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Our results underscore the need to broaden this perspective. As indexed by EMA, social anxiety was unrelated to the amount of time spent with distant companions. Moreover, socially anxious individuals did not report heightened NA when they were in the presence of distant companions (Table 1 and Fig. 4). This finding suggests that socially anxious individuals tend to experience normative emotional responses to distant companions in the absence of clear signs of rejection, scrutiny, or threat. Another possibility is that hyper-reactivity to strangers is specific to pathological levels of social anxiety or is only evident in a subset of socially anxious individuals. Adjudicating between these accounts represents another important avenue for future research.

From a clinical perspective, these observations suggest that naturally occurring social relationships are a potentially important target for intervention. Existing treatments for social anxiety typically focus on the individual, but our results highlight the value of simultaneously considering the role of close companions and developing supplementary interventions to enhance social connection, acceptance, and support. This could take the form of nurturing social-cognitive skills (e.g. emotional disclosure), cultivating stronger and more frequent ties with existing companions and social networks (e.g. via behavioral activation approaches), or reducing maladaptive thoughts and behaviors (e.g. neediness, overreliance) that promote conflict and rejection (Masi et al., Reference Masi, Chen, Hawkley and Cacioppo2011; Cacioppo et al., Reference Cacioppo, Grippo, London, Goossens and Cacioppo2015; Kok and Singer, Reference Kok and Singer2017). The development of smartphone-based interventions would provide a scalable and cost-effective alternative to more traditional modalities. Already, 77% of U.S. adults, and 94% of U.S. adults under the age of 30 own a smartphone (Pew Research Center, 2018). Mobile applications may be particularly useful for individuals who are unable or unwilling to use traditional care delivery systems and for subclinical presentations of social anxiety that do not warrant resource-intensive treatments (Ruscio, Reference Ruscio2019). Regardless of delivery method, intervention research would also provide a crucial opportunity for testing the causal contribution of close companions to the everyday experience of social anxiety.

Our results highlight some additional avenues for future research. To understand the generalizability of our inferences, it will be useful to extend the present approach to larger and more representative samples and to populations with more severe symptoms, distress, and impairment. Future EMA studies may benefit from using larger sampling windows or selectively targeting periods of increased stress or disrupted social intimacy (e.g. transition from high school or university, or from university to full-time work) in order to capture a wider range of social interactions and their association with momentary affect. It will also be helpful to examine the nature and quality of naturalistic social interactions – including momentary perceptions of social connection, emotional support, and conflict – in more detail using either EMA (e.g. context- or event-triggered) or behavioral observations. Developing a clearer understanding of the processes that promote heightened levels of NA during periods of solitude – when both social support and social threat are absent (Fig. 4) – is also likely to be useful (Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Tromp, Stockbridge, Kaplan, Tillman and Fox2016).

In conclusion, the present study suggests that close companions play an important role in the momentary experience of socially anxious young adults. The use of well-established techniques for intensive EMA and a relatively large sample selectively recruited from a pool of more than 6000 young adults increases our confidence in the reproducibility and translational relevance of these findings.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719002022.

Data

Raw data have been or will be made available via the National Institute of Mental Health's RDoC Database (https://data-archive.nimh.nih.gov/rdocdb).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of C. Garbin, L. Friedman, R. Tillman, and members of the Affective and Translational Neuroscience laboratory and constructive feedback from four anonymous reviewers and K. Rubin. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (DA040717, MH107444) and University of Maryland. Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

A.J.S. and K.A.D. designed the study. K.A.D., A.S.A., S.I. collected data. K.A.D., S.I., J.H. processed data. J.H., A.J.S., M.G.B., and K.A.D. designed the analytic strategy. J.H., M.G.B., and A.J.S. performed analyses. J.H. drafted the paper. J.H., M.G.B., and A.J.S. created figures and tables. A.J.S. supervised and funded the work. All authors edited the paper and approved the final version.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.