Introduction

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is highly prevalent worldwide (Stoltenborgh, van IJzendoorn, Euser, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, Reference Stoltenborgh, van IJzendoorn, Euser and Bakermans-Kranenburg2011) and is linked to an increased risk of severe subsequent psychopathology in adolescence and adulthood like suicidality, depression, psychosis, substance abuse, personality disorders, and particularly post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Cutajar et al., Reference Cutajar, Mullen, Ogloff, Thomas, Wells and Spataro2010; Pérez-Fuentes et al., Reference Pérez-Fuentes, Olfson, Villegas, Morcillo, Wang and Blanco2013). PTSD symptomatology is especially complex and comorbid following CSA (Bryant, Reference Bryant2019; Karatzias et al., Reference Karatzias, Hyland, Bradley, Cloitre, Roberts, Bisson and Shevlin2019), where sexual symptoms are nearly ubiquitously present (Büttner, Dulz, Sachsse, Overkamp, & Sack, Reference Büttner, Dulz, Sachsse, Overkamp and Sack2014; Pulverman, Kilimnik, & Meston, Reference Pulverman, Kilimnik and Meston2018). Yet, it is only recently that sexual symptoms in PTSD have gained growing attention, and apart from mere comorbidity rates, still too little is known about how sexual symptoms and PTSD are related to each other (Bornefeld-Ettmann et al., Reference Bornefeld-Ettmann, Steil, Lieberz, Bohus, Rausch, Herzog and Müller-Engelmann2018; Yehuda, Lehrner, & Rosenbaum, Reference Yehuda, Lehrner and Rosenbaum2015). Sexual symptoms are also still often overlooked in treatment studies and current treatments for PTSD seem to have little or no effect on sexual symptoms (O'Driscoll & Flanagan, Reference O'Driscoll and Flanagan2016). Hence, the etiology, diagnostics, and treatment of sexual symptoms in PTSD following childhood sexual abuse need further clarification. In particular, the status and the specific associations of sexual symptoms need to be understood better to inform the development of future treatment modules.

CSA, PTSD, sexual, depressive, and dissociative symptoms

CSA is associated with sexual anxiety, sexual avoidance, abuse flashbacks, aversion, dissociation during intercourse, negative feelings, and low sexual satisfaction (Bigras, Daspe, Godbout, Briere, & Sabourin, Reference Bigras, Daspe, Godbout, Briere and Sabourin2017; Rellini, Reference Rellini2008; Staples, Rellini, & Roberts, Reference Staples, Rellini and Roberts2012; Vaillancourt-Morel et al., Reference Vaillancourt-Morel, Godbout, Labadie, Runtz, Lussier and Sabourin2015) as well as sexual difficulties with desire, arousal, or orgasmic ability (Laumann, Paik, & Rosen, Reference Laumann, Paik and Rosen1999; Najman, Dunne, Purdie, Boyle, & Coxeter, Reference Najman, Dunne, Purdie, Boyle and Coxeter2005; Stephenson, Pulverman, & Meston, Reference Stephenson, Pulverman and Meston2014) in both men and women. However, in many cases a decreased desire or problems to achieve arousal and orgasm are not associated with significant levels of personal or interpersonal distress. Instead, many women with CSA feel distressed when they are ‘fully functional’ and able to experience desire, arousal and orgasm, as they often experience negative affect during sexual arousal (Stephenson, Hughan, & Meston, Reference Stephenson, Hughan and Meston2012). Furthermore, survivors of CSA often suffer from altered sexual self-schemas (Meston, Rellini, & Heiman, Reference Meston, Rellini and Heiman2006) as well as feelings of disgust and being contaminated (Badour, Feldner, Babson, Blumenthal, & Dutton, Reference Badour, Feldner, Babson, Blumenthal and Dutton2013; Jung & Steil, Reference Jung and Steil2012). CSA is also linked to chronic pelvic pain (Lampe et al., Reference Lampe, Doering, Rumpold, Sölder, Krismer, Kantner-Rumplmair and Söllner2003; Reiter, Shakerin, Gambone, & Milburn, Reference Reiter, Shakerin, Gambone and Milburn1991), dyspareunia and vaginism (Leonard & Follette, Reference Leonard and Follette2002), high-risk sexual behavior (Choi, Batchelder, Ehlinger, Safren, & O'Cleirigh, Reference Choi, Batchelder, Ehlinger, Safren and O'Cleirigh2017; Senn, Carey, & Vanable, Reference Senn, Carey and Vanable2008), prostitution (Cooper, Kennedy, & Yuille, Reference Cooper, Kennedy and Yuille2001; Tschoeke, Borbé, Steinert, & Bichescu-Burian, Reference Tschoeke, Borbé, Steinert and Bichescu-Burian2019), and compulsive sexual behavior (Vaillancourt-Morel et al., Reference Vaillancourt-Morel, Godbout, Labadie, Runtz, Lussier and Sabourin2015). CSA has also been linked to paraphilic interests (Briere, Smiljanich, & Henschel, Reference Briere, Smiljanich and Henschel1994; Frías, González, Palma, & Farriols, Reference Frías, González, Palma and Farriols2017; Fuss et al., Reference Fuss, Jais, Grey, Guczka, Briken and Biedermann2019; Lee, Jackson, Pattison, & Ward, Reference Lee, Jackson, Pattison and Ward2002; Nordling, Sandnabba, & Santtila, Reference Nordling, Sandnabba and Santtila2000).

CSA increases the risk of depression in adulthood (Coles, Lee, Taft, Mazza, & Loxton, Reference Coles, Lee, Taft, Mazza and Loxton2015). Also, PTSD is associated with depressive symptoms (Lazarov et al., Reference Lazarov, Suarez-Jimenez, Levy, Coppersmith, Lubin, Pine and Neria2019), and PTSD symptom severity co-occurs with depressive symptom severity in female sexual assault survivors (Au, Dickstein, Comer, Salters-Pedneault, & Litz, Reference Au, Dickstein, Comer, Salters-Pedneault and Litz2013). Depressive symptoms can have a severe impact on sexual functioning (Clayton & Balon, Reference Clayton and Balon2009).

Furthermore, pathological dissociation is highly prevalent among survivors of CSA and patients with complex PTSD (Hyland, Shevlin, Fyvie, Cloitre, & Karatzias, Reference Hyland, Shevlin, Fyvie, Cloitre and Karatzias2020; Vonderlin et al., Reference Vonderlin, Kleindienst, Alpers, Bohus, Lyssenko and Schmahl2018). Dissociative symptoms during sexual behavior are common among adults with CSA and increase vulnerability to high-risk sexual behavior and sexual revictimization (Hansen, Brown, Tsatkin, Zelgowski, & Nightingale, Reference Hansen, Brown, Tsatkin, Zelgowski and Nightingale2012). Simultaneous sexual preoccupation and sexual aversion has been linked to dissociation (Noll, Trickett, & Putnam, Reference Noll, Trickett and Putnam2003).

Theoretical models of sexual symptoms following CSA should consider physiological, cognitive, and affective processes (Rellini, Reference Rellini2008). Recent studies stress the role of PTSD as a mediating factor between CSA and sexual dysfunction (Bornefeld-Ettmann et al., Reference Bornefeld-Ettmann, Steil, Lieberz, Bohus, Rausch, Herzog and Müller-Engelmann2018; Yehuda et al., Reference Yehuda, Lehrner and Rosenbaum2015). However, the links of CSA to both sexual preferences causing distress and sexual dysfunction in survivors of CSA are not yet well understood.

CSA, PTSD, and sexual symptoms: A complex network perspective

An elaborated understanding of the co-occurrence of sexual symptoms and PTSD in survivors of CSA has long been hampered by the latent variable theory, the theoretical foundation of traditional psychopathology. In this framework, psychiatric disorders are conceptualized as latent variables causing observable symptoms (Borsboom, Reference Borsboom2008). This seemingly trivial assumption can lead to severe pitfalls, particularly regarding the understanding of heterogeneity and comorbidity of psychiatric disorders (Cramer, Waldorp, van der Maas, & Borsboom, Reference Cramer, Waldorp, van der Maas and Borsboom2010). For example, the exclusion of depression symptom criteria from ICD-11 PTSD did not result in the intended decrease of the comorbidity rate of PTSD and depression, reflecting the necessity to consider depression symptoms in conceptualizing PTSD (Barbano et al., Reference Barbano, der Mei, DeRoon-Cassini, Grauer, Lowe, Matsuoka and Shalev2019). In a complex network framework, comorbidity can easily be explained through bridge symptoms which occur in two or more disorders and link communities of symptoms (Cramer et al., Reference Cramer, Waldorp, van der Maas and Borsboom2010). Over and above that, even though psychiatric disorders are no discrete entities, network analysis can help to make meaningful distinctions between psychiatric disorders, e.g. between complex PTSD and borderline personality disorder (Knefel, Tran, & Lueger-Schuster, Reference Knefel, Tran and Lueger-Schuster2016) or PTSD, depression, and anxiety (Gilbar, Reference Gilbar2020).

Second, traditional reductionist models lack a focus on symptoms and their associations (Borsboom, Cramer, & Kalis, Reference Borsboom, Cramer and Kalis2019; Fried & Nesse, Reference Fried and Nesse2015) and thereby clearly fall short of the sophistication of reasoning in clinical practice (Fava, Rafanelli, & Tomba, Reference Fava, Rafanelli and Tomba2012). From a complex network perspective on the other hand, psychiatric disorders do not reflect latent entities but are a direct result of the causal interplay of symptoms (Borsboom & Cramer, Reference Borsboom and Cramer2013; Hofmann & Curtiss, Reference Hofmann and Curtiss2018). If the causal relations of symptoms become sufficiently strong, a network can get stuck in a disorder state, i.e. symptoms sustain each other mutually (Borsboom, Reference Borsboom2017). Third in a network framework, centrality analyses can be used to identify symptoms of particular importance in a network and thereby guide the identification of worthwhile targets for clinical intervention (McNally, Reference McNally2016). Outcome in trauma-focused psychotherapy has been found to be significantly linked to the extent of change of such central symptoms (Papini, Rubin, Telch, Smits, & Hien, Reference Papini, Rubin, Telch, Smits and Hien2020). Hence, there is promising evidence that the insights gained in network analyses are likely apt to inform the development of efficacious treatments in the future. Fourth and last, network analysis might help to explore idiographic symptom dynamics and help to personalize treatment (Fisher, Reeves, Lawyer, Medaglia, & Rubel, Reference Fisher, Reeves, Lawyer, Medaglia and Rubel2017).

In summary, as network analysis allows to investigate complex symptomatologies on a symptom-level and thereby to gain deep insights into comorbidity, possible causal mechanisms and worthwile treatment targets, it is a tool particulary well suited for the investigation of often neglected aspects of PTSD symptomatology (e.g. Armour et al., Reference Armour, Greene, Contractor, Weiss, Dixon-Gordon and Ross2020; Cramer, Leertouwer, Lanius, & Frewen, Reference Cramer, Leertouwer, Lanius and Frewen2020; Glück, Knefel, & Lueger-Schuster, Reference Glück, Knefel and Lueger-Schuster2017).

Therefore, we planned to investigate the prevalence of sexual symptoms, i.e. in our context difficulties engaging in sexual activities and sexual preferences causing distress, in PTSD following CSA. Then, to gain deeper insight into the associations of sexual symptoms in PTSD following CSA, we planned to analyze the associations of sexual symptoms with PTSD symptomatology in a large clinical sample of patients suffering from PTSD following CSA using network analysis. As depressive and dissociative symptoms are known to have a high impact on PTSD networks (Barbano et al., Reference Barbano, der Mei, DeRoon-Cassini, Grauer, Lowe, Matsuoka and Shalev2019; Cramer et al., Reference Cramer, Leertouwer, Lanius and Frewen2020), they were included as well in the analysis. Last, using measures of centrality and bridge centrality, we aimed to identify worthwhile treatment targets.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Our convenience sample consisted of 445 inpatients [male = 41 (9.2%); female = 404 (90.8%)] with an ICD-10 diagnosis of PTSD following childhood sexual abuse who were treated in the department of psychotraumatology of Clinic St. Irmingard, Germany. All diagnoses were clinical diagnoses given by attending psychologists and doctors relying on the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV personality disorders (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams, & Benjamin, Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams and Benjamin1994; Fydrich, Renneberg, Schmitz, & Wittchen, Reference Fydrich, Renneberg, Schmitz and Wittchen1997) as well as the German version of the structured interview of disorders of extreme stress (Boroske-Leiner, Hofmann, & Sack, Reference Boroske-Leiner, Hofmann and Sack2008; Pelcovitz et al., Reference Pelcovitz, van der Kolk, Roth, Mandel, Kaplan and Resick1997). Childhood sexual abuse was operationalized as at least a ‘moderate’ childhood sexual abuse score in the childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein and Fink, Reference Bernstein and Fink1998). The mean age of the sample was 48.1 years (s.d. = 10.5). Importantly at the time of admission, 321 patients (72.1%) had long-term psychopharmacological medication, the majority for more than 1 year (N = 269; 60.5%); 304 (68.3%) patients received antidepressants, 148 patients (33.3%) received anxiolytics, and 204 patients (45.8%) received antipsychotics. A more detailed description of the participants can be obtained from the online supplement. All psychometric tests were administered within 1 week after admission as part of the clinical routine assessment.

Assessments

Trauma history

Patients were administered the CTQ to retrospectively assess potentially traumatic childhood experiences. The CTQ consists of 25 items corresponding to the five subscales sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. Patients indicate the severity of items like ‘Someone tried to make me do sexual things or watch sexual things.’ on a 5-point Likert scale. The German version of the CTQ (Wingenfeld et al., Reference Wingenfeld, Spitzer, Mensebach, Grabe, Hill, Gast and Driessen2010) has good psychometric properties.

Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms

The Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R; Weiss & Marmar, Reference Weiss and Marmar1996) was used to assess PTSD symptoms. The IES-R consists of 22 items like ‘I had dreams about it’ that are answered on a 4-point Likert scale and correspond to three subscales (intrusion, avoidance, hyperarousal). The psychometric properties of the German translation (Maercker & Schützwohl, Reference Maercker and Schützwohl1998) are sound.

General psychopathology and sexual symptoms

The ICD-10 symptom rating (ISR; Fischer, Tritt, Klapp, and Fliege, Reference Fischer, Tritt, Klapp and Fliege2010) is a self-rating questionnaire closely related to the syndrome structure of ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1992). In many aspects, it resembles the internationally better known symptom checklist 90 revised (Derogatis, Reference Derogatis1983) to which it is highly correlated (Tritt et al., Reference Tritt, von Heymann, Zaudig, Loew, Söllner, Fischer and Bühner2010). With 29 items like ‘I no longer enjoy doing things I used to enjoy.’, the ISR assesses 36 symptoms. Internal consistency and validity are sufficient. Difficulties engaging in sexual activities is assessed using the item ‘I have difficulties engaging in sexual activities.’. The paraphilia item ‘I have a problem with my sexual preferences.’ is in accordance with modern conceptualizations of paraphilia focusing on distress and not the mere presence of atypical sexual preferences (Reed et al., Reference Reed, Drescher, Krueger, Atalla, Cochran, First and Saxena2016). On the other hand, its specificity is presumably low and item endorsement could possibly also hint to distress associated with a non-paraphilic sexual orientation. Hence, the item should be interpreted as reflecting what we term ‘sexual preferences causing distress’. To gain a deeper understanding of the symptomatology associated with an endorsement of the paraphilia screening item, we analyzed all patient charts regarding the presence of transsexuality, transvestism, transvestic fetishism, exhibitionism, voyeurism, pedophilia, sadomasochistic rape phantasies, sexual sadism, sexual masochism, high-risk sexual behavior, compulsive sexual behavior, and non-heterosexual orientation. Furthermore, we assessed whether patients had a history as sex workers.

Dissociative symptoms

The Dissociative Experiences Scale – Taxon (DES-T; Waller, Putnam, and Carlson, Reference Waller, Putnam and Carlson1996) was developed to assess symptoms indicative of pathological dissociation like identity alteration, depersonalization, and auditory hallucinations. A cut-off of 20% has been shown to reliably identify subjects with a dissociative disorder (Waller & Ross, Reference Waller and Ross1997). The German version offers good psychometric properties (Spitzer, Freyberger, Brähler, Beutel, & Stieglitz, Reference Spitzer, Freyberger, Brähler, Beutel and Stieglitz2015).

Data analytic plan

R version 3.6.1 (R Core Team, 2019) and the R packages qgraph (Epskamp, Cramer, Waldorp, Schmittmann, & Borsboom, Reference Epskamp, Cramer, Waldorp, Schmittmann and Borsboom2012), apaTables (Stanley, Reference Stanley2018), networktools (Jones, Reference Jones2019), and bootnet (Epskamp, Borsboom, & Fried, Reference Epskamp, Borsboom and Fried2018) were used for data analysis.

Network estimation

The network approach to psychopathology allows to visualize the multivariate interdependencies of symptoms. In a symptom network, nodes represent symptoms and edges reflect pairwise relations between these symptoms. For our analysis, 22 PTSD symptoms, four depression symptoms, eight dissociative symptoms, and two sexual symptoms were included in the network estimation procedure. Using partial polychoric correlations, we investigated the connectivity of each symptom while controlling for all other associations in the network. To control for the possibility of false positive associations, we used the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO; Tibshirani, Reference Tibshirani2011), thereby setting small edges which are likely due to noise exactly to zero and regularizing the network (Epskamp & Fried, Reference Epskamp and Fried2016). Model selection was conducted using the extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC) with a conservative tuning hyperparameter of ɣ = 0.5 ensuring high specificity (Foygel & Drton, Reference Foygel and Drton2010).

Network visualization

The Fruchtermann-Reingold algorithm (Fruchterman & Reingold, Reference Fruchterman and Reingold1991) was used to place nodes with more and/or stronger connections more closely together. The maximum edge value was set to the strongest edge identified in the network (0.47) and the minimum edge value was set to 0.03 to enhance interpretability. We set positive edges to be printed in green and negative ones in red. Stronger connections are indicated by more saturated and thicker edges. Importantly, the Fruchtermann-Reingold algorithm fosters readability but does not allow for a meaningful interpretation of the distances between nodes.

Centrality Estimation and Bridge Centrality Estimation

Following recommendations from recent methodological work (Epskamp et al., Reference Epskamp, Borsboom and Fried2018; Fried et al., Reference Fried, Eidhof, Palic, Costantini, Huisman-van Dijk, Bockting and Karstoft2018; Hallquist, Wright, & Molenaar, Reference Hallquist, Wright and Molenaar2019), we used strength centrality to analyze the direct connections of nodes. Reflecting the sum of all absolute edge weights a node is directly connected to, strength centrality quantifies the connectivity of a node to all other nodes of the network and can thereby hint to ‘core’ symptoms of particular importance of a psychiatric disorder (Blanken et al., Reference Blanken, Deserno, Dalege, Borsboom, Blanken, Kerkhof and Cramer2018; Bringmann et al., Reference Bringmann, Elmer, Epskamp, Krause, Schoch, Wichers and Snippe2019). In networks consisting of symptoms of different psychiatric disorders, it is also important to consider bridge centrality (Jones, Ma, & McNally, Reference Jones, Ma and McNally2019). Bridge symptoms in a network are symptoms that work as a link between communities of disorder-specific symptoms and may therefore be helpful in explaining comorbidity. Hence, we also analyzed which symptoms are of importance in the communication of PTSD, depression, dissociation, and sexual symptom communities. Bridge expected influence (1-step) and bridge expected influence (2-step) were chosen as outcome parameters as recommended when negative edges are present. Bridge expected influence (1-step) is defined as the sum of the values of all edges between a node and all nodes from different communities. Bridge expected influence (2-step) also considers indirect effects a node may have on other communities via other nodes.

Local clustering analysis

Local clustering coefficients measure local density in a network by quantifying the degree to which the nodes a node is connected to are connected to each other, respectively. Hence, the coefficients can be interpreted as reflecting the redundancy of a node. For the present analyses, following recommendations by Costantini et al. (Reference Costantini, Epskamp, Borsboom, Perugini, Mõttus, Waldorp and Cramer2015), we chose the Zhang coefficient (Zhang & Horvath, Reference Zhang and Horvath2005).

Accuracy and Stability

To analyze the accuracy of the network, we bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals of all edge weights. In a next step, we used the subsetting bootstrap function implemented in the bootnet package (Epskamp et al., Reference Epskamp, Borsboom and Fried2018) to investigate the stability of the centrality measures in re-estimated networks using samples with dropped subjects. High correlations of the original centrality estimates with the estimates from re-estimated networks indicate high stability. In a third step, we applied a correlation stability analysis. The correlation stability coefficient reflects the maximum number of dropped cases to retain a 95% probability of a correlation of at least r = 0.7 between the parameters of the original network and the parameters of the dropped cases networks and should not be below 0.25 (Epskamp et al., Reference Epskamp, Borsboom and Fried2018).

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 171 patients (38.4%) presented with a comorbid personality disorder, with emotionally unstable personality disorder being the most prevalent-specific personality disorder (N = 77; 17.3%). In all, 131 patients (29.4%) had a comorbid diagnosis of a dissociative disorder. Of these patients, the majority had either a mixed dissociative disorder (N = 44; 9.9%) or a complex dissociative disorder (N = 65; 14.6%) according to the phenomenological approach of Dell (Reference Dell2006). A total of 18 patients (4.0%) presented with dissociative identity disorder and 47 patients (10.6%) presented with dissociative disorder not otherwise specified. A comorbid affective disorder was present in 348 patients (82.7%).

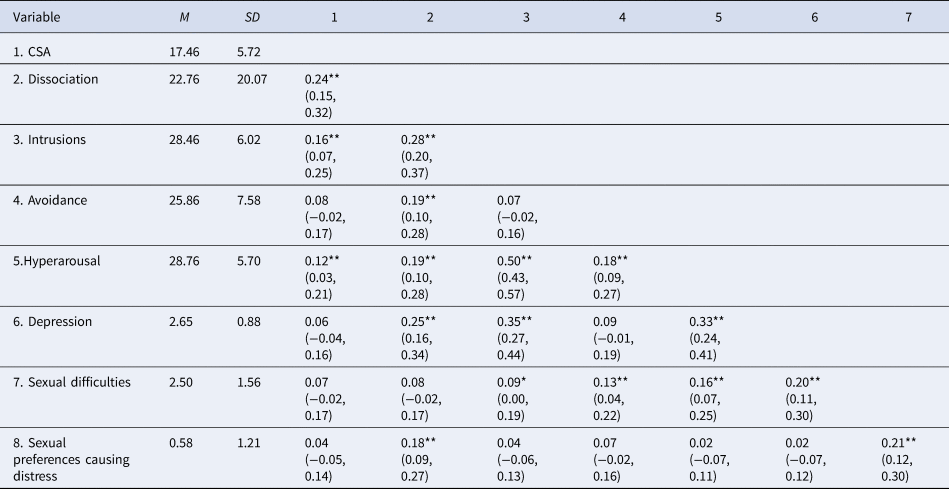

Descriptive statistics and correlations of the psychometric assessments can be obtained from Table 1. Most importantly, patients reported both severe CSA in the CTQ (M = 18.0; s.d. = 5.7) as well as severe PTSD symptoms in the IES-R (M = 83.1; s.d. = 13.5). In total, 201 patients (45.2%) reported a DES-T value above the cut-off value of 20% (M = 22.8; s.d. = 20.1; median = 17.8; min = 0; max = 87.5). The mean score of the depression scale of the ISR was found to be 2.8 (s.d. = 0.8; median = 2.8; min = 0.25; max = 4). A total of 360 patients (81%) reported difficulties engaging in sexual activities to some degree in the ISR (M = 2.5; s.d. = 1.6; median = 3; min = 0; max = 4) and 102 (23%) patients reported to suffer from their sexual preferences in the ISR (M = 0.6; s.d. = 1.2; median = 0; min = 0; max = 4).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics Means, standard deviations, and correlations with 95% confidence intervals

CSA, childhood sexual abuse scale of the CTQ; Dissociation, DES-T sum score; Intrusions, IES-R intrusion score; Avoidance, IES-R avoidance score; Hyperarousal, IES-R hyperarousal score; Depression, ISR depression scale; Sexual difficulties, ISR sexual dysfunction item; Sexual preferences causing distress, ISR paraphilia item.

Note. M and s.d. represent mean and standard deviation, respectively. Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval for each correlation. * indicates p < 0.05. ** indicates p < 0.01.

For 80 of the 102 patients who reported to suffer from their sexual preferences, the respective patient charts contained sufficient data on sexual anamnesis for further analyses. A total of 43 patients (53.75%) reported to suffer from masochistic rape fantasies. High-risk sexual behavior was found in 41 cases (51.25%), and compulsive sexual behavior was found in 21 cases (26.25%). Sexual masochism was reported by 17 patients (21.25%). For more comprehensive results of the chart analyses, please see the supplement.

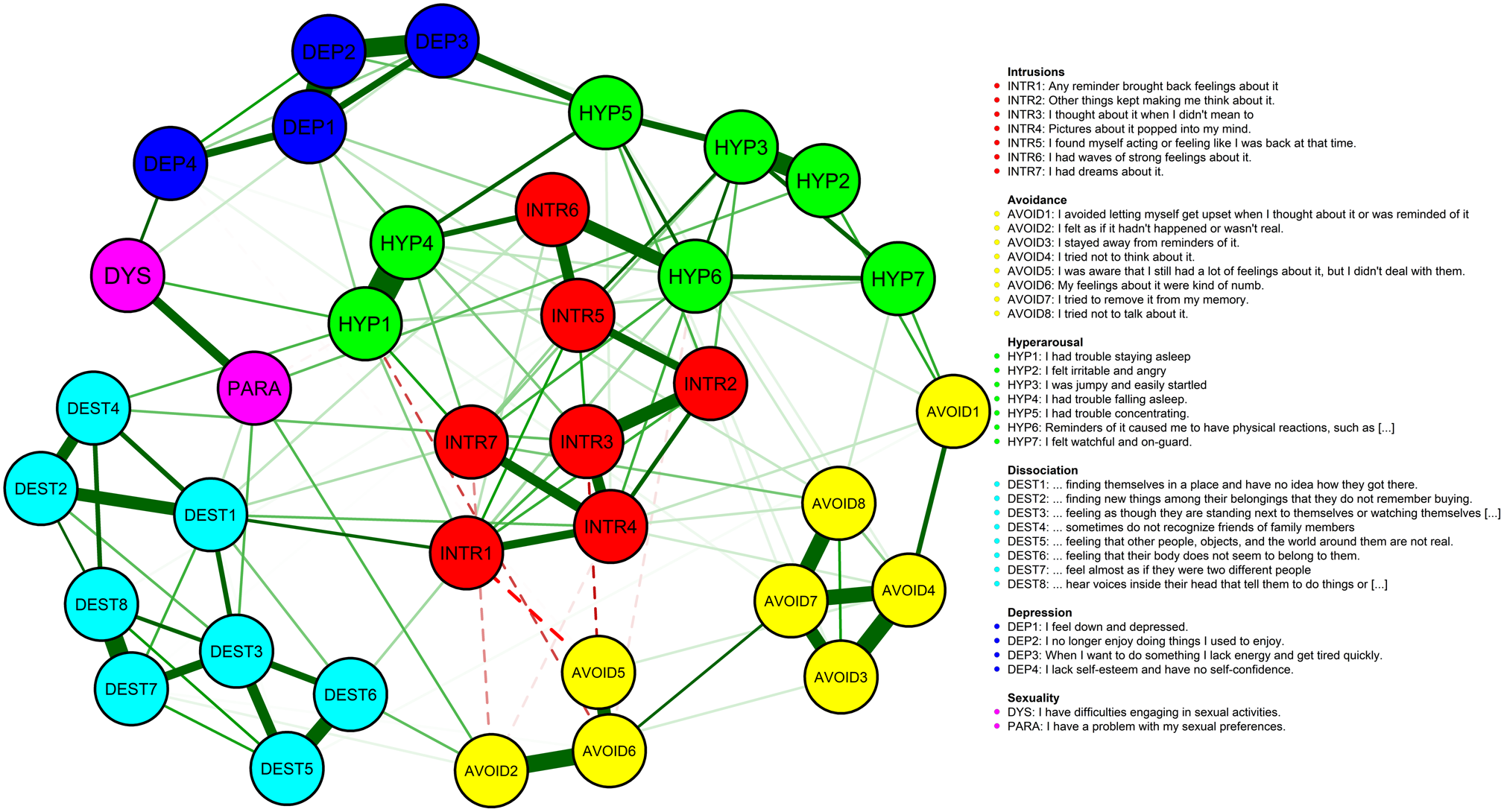

gLASSO network

A visualization of the network structure can be obtained from Fig. 1. The majority of the associations identified were positive. The strongest association found in the network was between troubles falling asleep (HYP1) and troubles staying asleep (HYP4). Other associations of particular strength were found between emotional (INTR6) and physical reactions (HYP6) to trauma reminders as well as between anhedonia (DEP2) and lack of energy (DEP3).

Fig. 1. gLASSO regularized partial correlation network with EBIC model selection. Negative associations are represented by dashed lines in the print version. For the color version, please see the online article.

Strong associations were found between intrusive symptoms and hyperarousal symptoms (INTR2/HYP3, INTR6/HYP4, INTR5/HYP3). A mixed picture was found for avoidance symptoms. A subgroup of avoidance symptoms (AVOID2, AVOID5, AVOID6) was found to be negatively associated with intrusive and hyperarousal symptoms like nightmares (INTR7), sleep disorder (HYP1), intrusive thoughts (INTR3), and intrusive feelings (INTR1). Yet, another subgroup of avoidance symptoms was found to be positively linked to both intrusive symptoms (AVOID4/INTR4, AVOID8/INTR7, etc.) and hyperarousal symptoms (AVOID1/HYP2, AVOID8/HYP7, etc.).

Difficulties engaging in sexual activities (DYS) were found to be specifically linked to the network via lack of self-esteem (DEP4), sleep disorder (HYP1), and lack of energy (DEP1). Also, difficulties engaging in sexual activities were found to be linked to sexual preferences causing distress (PARA). The latter ones, on the other hand, were found to be linked to the network via dissociative amnesia (DEST1), depersonalization (DEST3), derealization (AVOID2), and irritability and anger (HYP2).

Dissociative symptoms were found to be linked primarily to intrusive symptoms (DEST1/INTR1, DEST1/INTR4, DEST1/INTR7, DEST4/INTR3 etc.). Somatoform dissociation (DEST6) was found to be linked to physical reactions to trauma reminders (HYP6). Whereas depressive symptoms of anhedonia (DEP2) and lack of energy (DEP3) showed links to troubles concentrating (HYP5), depressed mood (DEP1) was linked to both hyperarousal (HYP1, HYP4) as well as intrusive symptoms (INTR2, INTR6).

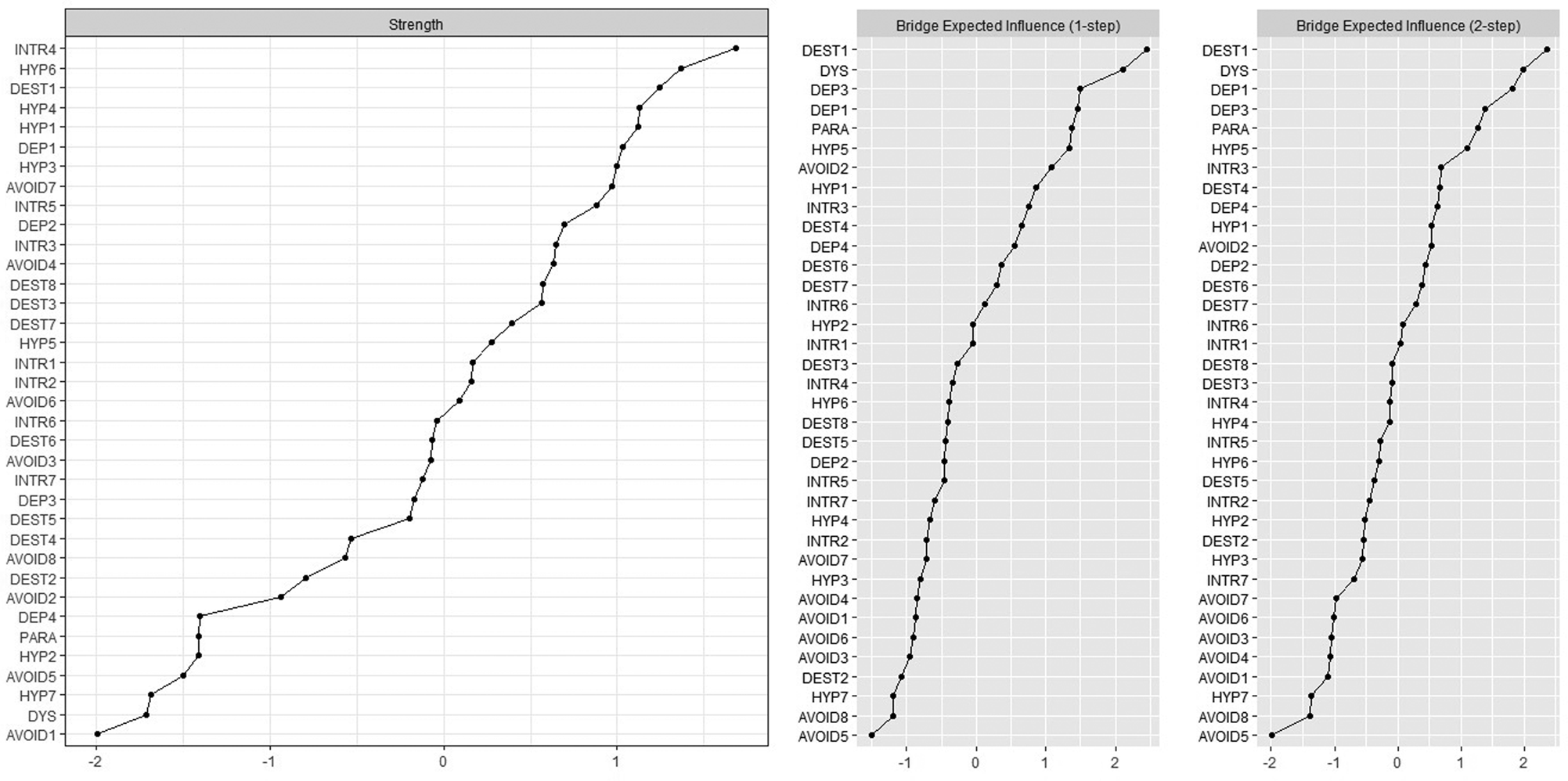

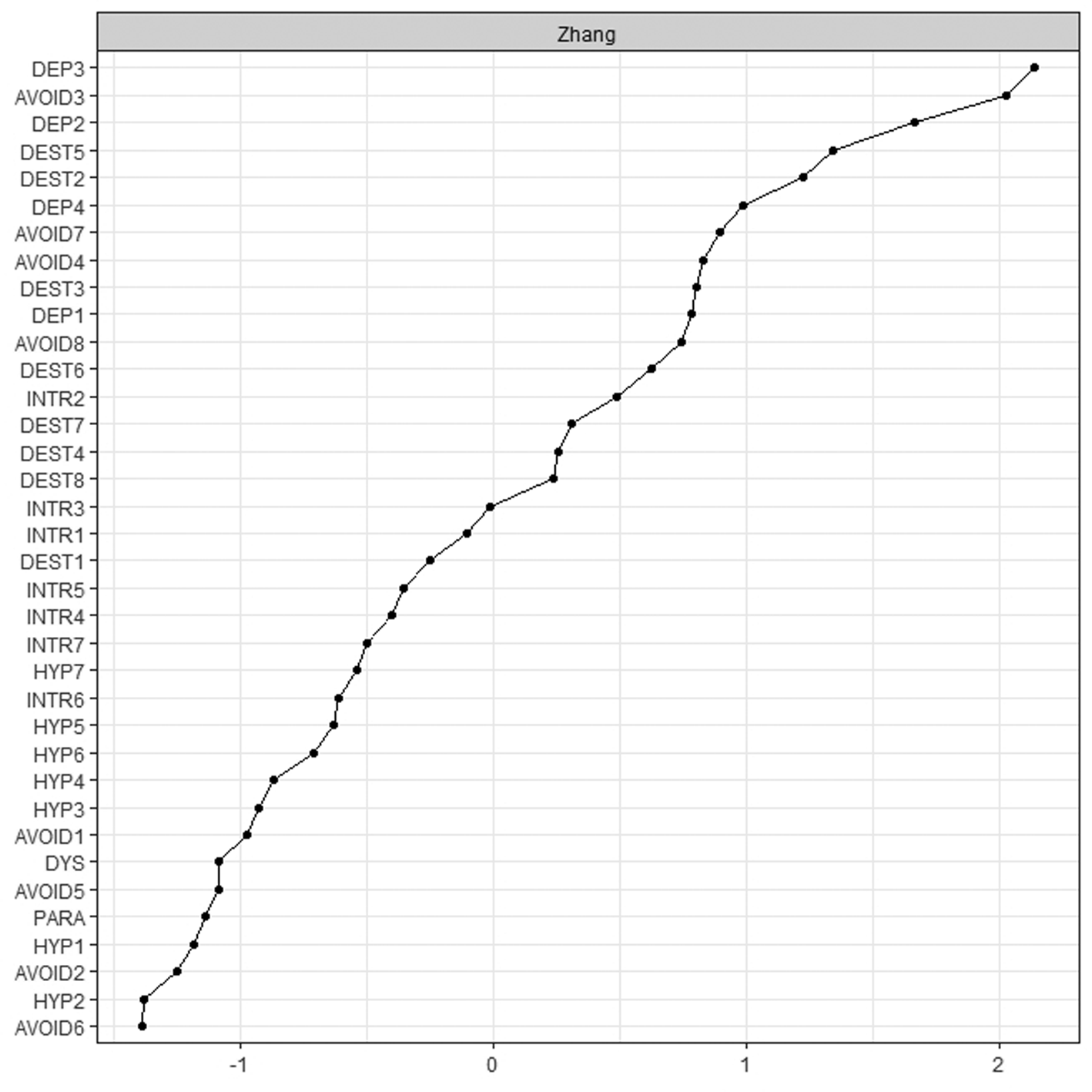

In this particular order, visual intrusions (INTR4), physical reactions to trauma reminders (HYP6), dissociative amnesia (DEST1), troubles falling asleep (HYP4), and staying asleep (HYP1) were identified as the five symptoms with the greatest influence on the network (please see Fig. 2). Regarding bridge centrality, items of dissociative amnesia (DEST1), difficulties engaging in sexual activities (DYS), lack of energy (DEP3), and depressed mood (DEP1) showed to be of particular importance in the communication of PTSD, dissociative, depressive, and sexual symptoms (please see Fig. 2). Using Zhang's estimate of local clustering, high redundancies were found for depression items (DEP3, DEP2, DEP4, DEP1), avoidance items (AVOID3, AVOID7, AVOID4), and dissociative items (DEST5, DEST2, DEST3). Sexual symptoms were not found to cluster locally, indicating low redundancy. Please see Fig. 3.

Fig. 2. Strength centrality and bridge expected influence of the network's symptoms ordered by strength and influence.

Fig. 3. Zhang's estimate of local clustering ordered by strength of local clustering.

Accuracy and stability

The edge weight bootstrap analysis (see Fig. 4) reflects an accurately estimated network with strong edges being substantially stronger than the majority of edges. The subset bootstrapping analysis showed sufficient stability of both the strength as well as the bridge expected influence centrality estimate (see Fig. 4). The correlation stability coefficients were found to be CS = 0.52 for strength centrality and 0.28 for bridge expected influence.

Fig. 4. Accuracy and stability analysis. Top: Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for the edge weights in the gLASSO EBIC network. The labels of the edges/symptoms on the y-axis have been removed to avoid cluttering. The red line shows the sample edge weight values and the grey areas show the respective bootstrapped confidence intervals. Bottom left: Results of the subsetting bootstrap analysis reflect high correlations of the node strength centrality for the original gLASSO EBIC network and the indices of networks constructed with subsets of the original sample. Bottom right: Results of the subsetting bootstrap analysis reflect high correlations of the bridge expected influence centrality for the original gLASSO EBIC network and the indices of networks constructed with subsets of the original sample.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, our analysis represents the first network analysis of sexual, depressive, dissociative, and PTSD symptoms in a sample of patients with PTSD following CSA. Limitations of the analysis are the use of only two sexual symptom items and the assessment by self-report measures. Retrospective self-reported childhood abuse should be interpreted with caution due to biases (Bürgin, Boonmann, Schmid, Tripp, & O'Donovan, Reference Bürgin, Boonmann, Schmid, Tripp and O'Donovan2020).

First, our results are in line with findings hinting to a high prevalence of sexual symptoms in PTSD (Bornefeld-Ettmann et al., Reference Bornefeld-Ettmann, Steil, Lieberz, Bohus, Rausch, Herzog and Müller-Engelmann2018; Büttner et al., Reference Büttner, Dulz, Sachsse, Overkamp and Sack2014). Chart analyses furthermore provided preliminary evidence that suffering from one's sexual preferences in patients with PTSD following CSA is likely due to either high-risk sexual behavior, compulsive sexual behavior, sexual masochism and in particular masochistic rape fantasies, or a combination thereof. Our results are thereby in line with previous findings regarding links of CSA to sexual masochism and masochistic rape fantasies (Briere et al., Reference Briere, Smiljanich and Henschel1994; Frías et al., Reference Frías, González, Palma and Farriols2017; Horowitz, Reference Horowitz1990; Nordling et al., Reference Nordling, Sandnabba and Santtila2000; Shulman & Home, Reference Shulman and Home2006). Whereas masochistic rape fantasies are common and linked to openness to sexual experience and reduced sexual guilt in the general population (Bivona & Critelli, Reference Bivona and Critelli2009; Bivona, Critelli, & Clark, Reference Bivona, Critelli and Clark2012; Strassberg & Lockerd, Reference Strassberg and Lockerd1998), in survivors of CSA, unwanted rape fantasies involving pain, humiliation, or force often cause considerable distress (Westerlund, Reference Westerlund1992). Second, our results in many ways replicate prior network analyses on PTSD, thereby answering critical claims regarding replicability and generalizability of network analyses (Borsboom, Robinaugh, Rhemtulla, & Cramer, Reference Borsboom, Robinaugh, Rhemtulla and Cramer2018; Contreras, Nieto, Valiente, Espinosa, & Vazquez, Reference Contreras, Nieto, Valiente, Espinosa and Vazquez2019; Forbes, Wright, Markon, & Krueger, Reference Forbes, Wright, Markon and Krueger2017; Reference Forbes, Wright, Markon and Krueger2019). Third, the inclusion of depressive, dissociative, and sexual symptoms besides PTSD symptoms allows for an analysis of the interplay of a variety of common sequelae of CSA on an item-level. Fourth, and in particular, our results allow to investigate the specific associations of sexual symptoms in PTSD following CSA.

Our centrality analysis is in line with findings from a Bayesian network analysis regarding the key role of physiological reactions to trauma reminders in PTSD following CSA (McNally, Heeren, & Robinaugh, Reference McNally, Heeren and Robinaugh2017) as well as with findings reflecting the central role of sleep problems, concentration problems, and anhedonia in explaining the comorbidity of depression and PTSD (Afzali et al., Reference Afzali, Sunderland, Teesson, Carragher, Mills and Slade2017; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Batchelder, Ehlinger, Safren and O'Cleirigh2017). Furthermore, our analysis replicates findings from a multisite study comparing four PTSD samples identifying intrusions, an exaggerated startle response, heightened physiological reactivity, and anhedonia as central aspects of PTSD (Fried et al., Reference Fried, Eidhof, Palic, Costantini, Huisman-van Dijk, Bockting and Karstoft2018). Interestingly, at the same time, in our sample of survivors of CSA, dissociative amnesia exerted much higher effects than reported by Fried et al. (Reference Fried, Eidhof, Palic, Costantini, Huisman-van Dijk, Bockting and Karstoft2018) for their samples. This may hint to a specific role of pathological dissociation in PTSD following childhood abuse (Kratzer et al., Reference Kratzer, Heinz, Pfitzer, Padberg, Jobst and Schennach2018; Vang, Shevlin, Karatzias, Fyvie, & Hyland, Reference Vang, Shevlin, Karatzias, Fyvie and Hyland2018).

Furthermore, dissociative symptoms were not only found to be of central importance for the network, they also showed to be linked specifically to intrusive symptoms and hence to what is assumed to be the core of PTSD, i.e. a memory disorder (Brewin, Reference Brewin2011). Thereby, our results replicate findings of links of depersonalization and intrusive symptoms in adult survivors of sexual abuse (McBride, Hyland, Murphy, & Elklit, Reference McBride, Hyland, Murphy and Elklit2020) and stress the importance to consider both trauma-related distress associated with normal waking consciousness as well as qualitatively distinct trauma-related altered states of consciousness (Frewen, Brown, & Lanius, Reference Frewen, Brown and Lanius2017).

Sexual preferences causing distress were not found to be directly linked to intrusive traumatic memories, leading to doubts that they represent mere classically conditioned sexual reactions. Instead, they were found to be linked to derealization, depersonalization, and dissociative amnesia. Our results are therefore in line with previous findings of a link of pathological dissociation and simultaneous sexual preoccupation and sexual aversion (Noll et al., Reference Noll, Trickett and Putnam2003), a link of high-risk sexual behavior and avoidance of thoughts and feelings (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Batchelder, Ehlinger, Safren and O'Cleirigh2017), and indirect connections of PTSD and high-risk sexual behavior (Armour et al., Reference Armour, Greene, Contractor, Weiss, Dixon-Gordon and Ross2020). Furthermore, sexual preferences causing distress were linked to irritability and anger. Anger is another insufficiently recognized major feature of PTSD following childhood abuse and has been conceptualized as a maladaptive strategy to avoid trauma-related emotions such as helplessness (Glück et al., Reference Glück, Knefel and Lueger-Schuster2017). In summary, sexual preferences causing distress seem to be linked specifically to the ‘non-realization’ of traumatic events (Janet, Reference Janet1919). Rape fantasies, masochism, and sexual reenactments of past abuse may be understood as a dissociative mechanism to escape from painful feelings and to reverse the helplessness endured during traumatic experiences of sexual violence, thereby bestowing survivors a temporarily sense of control (Howell, Reference Howell1996; Lahav, Talmon, Ginzburg, & Spiegel, Reference Lahav, Talmon, Ginzburg and Spiegel2019; Money, Reference Money1987; Ruszczynski, Reference Ruszczynski, Morgan and Ruszczynski2007), which is maintained by operant conditioning (Wilson & Wilson, Reference Wilson and Wilson2008). This was also in line with conceptualizations of sexual masochism as an emotional self-regulation process in women with borderline personality disorder and childhood sexual abuse (Frías et al., Reference Frías, González, Palma and Farriols2017). Yet, the question whether sexual preferences causing distress may be understood as a dysfunctional coping mechanism relying on dissociation and maintained by operant conditioning needs further exploration. Moreover, we cannot rule out the possibility that at least some patients reported to suffer from non-paraphilic sexual preferences for reasons like prejudice and minority stress (Meyer, Reference Meyer2003) which should also be considered in future studies.

Apart from a link to sexual preferences causing distress, difficulties engaging in sexual activities were found to be linked specifically to low self-esteem, sleep disorder and lack of energy, stressing the role of depressive symptoms and contradicting prior results linking difficulties engaging in sexual activities in PTSD primarily to PTSD and not depressive symptoms (Bornefeld-Ettmann et al., Reference Bornefeld-Ettmann, Steil, Lieberz, Bohus, Rausch, Herzog and Müller-Engelmann2018; Wilcox, Redmond, & Hassan, Reference Wilcox, Redmond and Hassan2014; Yehuda et al., Reference Yehuda, Lehrner and Rosenbaum2015). In this context, it is important to stress again that our results do not allow to rule out that the associations identified are caused by variables not included in the analysis. On the contrary, considering the high prevalence of long-term psychopharmaceutical treatments in the sample, it is likely that the link of depressive symptoms and difficulties engaging in sexual activities might at least partly be due to antidepressant medication (Kotler et al., Reference Kotler, Cohen, Aizenberg, Matar, Loewenthal, Kaplan and Zemishlany2000; Montejo, Montejo, & Navarro-Cremades, Reference Montejo, Montejo and Navarro-Cremades2015). Another noticeable aspect is that our results regarding a link of difficulties engaging in sexual activities and low self-esteem are in line with conceptualizations of difficulties engaging in sexual activities in PTSD stressing the importance of cognitive-emotional schemas (Leonard & Follette, Reference Leonard and Follette2002). Other possible explanations of the link of difficulties engaging in sexual activities and low self-esteem are that difficulties engaging in sexual activities may lead to reductions in self-esteem or that difficulties engaging in sexual activities and low self-esteem and negative expectations have a reciprocal relationship that forms a vicious circle (Frank, Noyon, Höfling, & Heidenreich, Reference Frank, Noyon, Höfling and Heidenreich2010). Different causal pathways of difficulties engaging in sexual activities in PTSD might exist and more extensive research is needed urgently.

In summary, our results reflect a high prevalence as well as distinct associations and mechanisms of sexual symptoms in PTSD following CSA. Even though they were found to show specific links to other aspects of psychopathology, negligible local clustering estimates indicate that the relative independence of sexual symptoms in PTSD following CSA requires their specific consideration in research and treatment. Thereby, our results might also offer a possible explanation of why so far psychological treatments of PTSD have shown to have no effect on sexual symptoms (O'Driscoll & Flanagan, Reference O'Driscoll and Flanagan2016). We agree that sexual symptoms need to be addressed specifically in the diagnostics and treatment of PTSD (Bornefeld-Ettmann et al., Reference Bornefeld-Ettmann, Steil, Lieberz, Bohus, Rausch, Herzog and Müller-Engelmann2018; Yehuda et al., Reference Yehuda, Lehrner and Rosenbaum2015).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001750.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Deutschsprachige Gesellschaft für Psychotraumatologie (DeGPT) for support, advice, and in particular for the organization of the DeGPT Autumn School in 2018 with a valuable workshop on network analysis by Sanne Booij. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

L.K., P.H., R.S., and M.B. planned the study. L.K., P.H., and their team were responsible for the data collection. L.K. and M.K. realized the statistical analysis. All authors interpreted and discussed the results. L.K., M.K., S.B., and M.B. drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the draft critically and gave their approval to the final version.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Due to the retrospective nature of the investigation, a formal consent of the local ethics committee was not required. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the analysis.