Background

The first 12 months after childbirth is a vulnerable time for any new mother, involving rapid biological, social, and emotional changes (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Molyneaux, Dennis, Rochat, Stein and Milgrom2014; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Chandra, Dazzan and Howard2014; Meltzer-Brody et al., Reference Meltzer-Brody, Howard, Bergink, Vigod, Jones, Munk-Olsen, Honikman and Milgrom2018). The incidence of new-onset mental disorder is high, particularly in the first 3 months postpartum (Wisner et al., Reference Wisner, Sit, Mcshea, Rizzo, Zoretich, Hughes, Eng, Luther, Wisniewski, Costantino, Confer, Moses-Kolko, Famy and Hanusa2013; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Chandra, Dazzan and Howard2014). Recent evidence further indicates variations in incidence, as moderate postpartum mental disorders (PPMD) (when defined as disorders treated with antidepressants and/or antipsychotics) occur in 7.72 cases per 1000 births, and moderate-severe disorders (when defined as disorders requiring psychiatric outpatient treatment) in 1.63 cases per 1000. In comparison, the most severe episodes requiring specialized inpatient psychiatric treatment, occur in 0.64 cases per 1000 births (Munk-Olsen et al., Reference Munk-Olsen, Maegbaek, Johannsen, Liu, Howard, Di Florio, Bergink and Meltzer-Brody2016).

Negative mental health outcomes have been observed among women suffering from PPMD, including a concerning highly elevated risk of suicide within the first year after initial diagnosis (Appleby et al., Reference Appleby, Mortensen and Faragher1998; Johannsen et al., Reference Johannsen, Larsen, Laursen, Bergink, Meltzer-Brody and Munk-Olsen2016; Khalifeh et al., Reference Khalifeh, Hunt, Appleby and Howard2016). This has been confirmed through inquiries into maternal deaths in the UK and other high-income countries which identified suicides as one of the leading causes of death among new mothers (Lewis, Reference Lewis and Lewis2001; Cantwell, Reference Cantwell, Clutton-Brock, Cooper, Dawson, Drife, Garrod, Harper, Hulbert, Lucas, McClure, Millward-Sadler, Neilson, Nelson-Piercy, Norman, O'Herlihy, Oates, Shakespeare, de Swiet, Williamson, Beale, Knight, Lennox, Miller, Parmar, Rogers and Springett2011; Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Schmied, Dennis, Barnett and Dahlen2013).

Prior history of self-harm is an established and significant risk factor for later suicide amongst the general population (Cavanagh et al., Reference Cavanagh, Carson, Sharpe and Lawrie2003; Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Metcalfe and Gunnell2014; Runeson et al., Reference Runeson, Haglund, Lichtenstein and Tidemalm2016; Olfson et al., Reference Olfson, Wall, Wang, Crystal, Gerhard and Blanco2017). One small case-control study of female emergency department attendees showed that the rate of self-harm in the postpartum period was lower than expected given the high incidence of new-onset mental disorder on the postpartum period (Appleby and Turnbull, Reference Appleby and Turnbull1995). However, to our knowledge no previous study has investigated and quantified the risk of self-harm specifically among women with the first onset of PPMD, or whether self-harm is associated with later suicide in this population.

Consequently, the aims of this study were:

• To describe the risk of self-harm among women with a diagnosis of first-onset PPMD compared to other groups of women from the background population (both mothers and childless women, with and without non-postpartum onset of mental disorders).

• To investigate the extent to which self-harm in women with a diagnosis of first onset PPMD is associated with later suicide.

Methods

Study design and population

In order to investigate our aim, we conducted an epidemiological register-based cohort study using Danish population data.

For our main analysis, we included all women born in Denmark on 1 January 1963 or later. Follow-up started at the women's 15th birthday and was completed at date of first hospital-registered self-harm episode; date of death, emigration, or 31 December 2016, whichever came first. This allowed a maximum follow-up period of 39 years in the cohort comprising a total of 1 202 292 women.

The main exposure variable was the first onset of moderate-severe PPMD. Moderate-severe PPMD was defined as a woman experiencing any first inpatient or outpatient contact with a psychiatric facility within 90 days after giving birth to her first live-born child and is referred to as ‘postpartum mental disorder’ across this paper. In defining contacts and treatments at psychiatric treatment facilities we included all diagnostic codes in the F-chapter of mental and behavioral disorders in ICD-10 (F00–F99) and the corresponding diagnostic codes in ICD-8 (290.xx–315.xx) (Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Mors, Bertelsen, Waltoft, Agerbo, Mcgrath, Mortensen and Eaton2014). By defining PPMD as those occurring within a restricted interval of 3 months after giving birth, we assumed that childbirth was the specific triggering factor causing the onset of the disorder in the affected women.

The main outcome of interest was any first self-harm leading to a hospital-registered episode, as a recorded inpatient or outpatient contact of self-harm at either medical or psychiatric hospitals. This was defined by the women included in the cohort fulfilling at least one of the following five criteria (Helweg-Larsen et al., Reference Helweg-Larsen, Kjøller, Juel, Sundaram, Laursen, Kruse, Nørlev and Davidsen2005; Gasse et al., Reference Gasse, Danielsen, Pedersen, Pedersen, Mors and Christensen2018):

(1) ‘suicide attempt’ as contact reason within the register,

(2) an ICD-8 diagnosis within diagnostic codes: E9500–E9599,

(3) contact with a main diagnosis within the ICD-10 F-chapter (mental disorder) and a secondary diagnosis of poisoning (ICD-10: T36–T50 and T52–T60) or lesions at the forearm, wrist, or hand (ICD-10: S51, S55, S59, S61, S65, and S69),

(4) a main diagnosis of poisoning with weak analgesics, epileptic drugs, or carbon monoxide (ICD-10: T39, T42, T43, and T58) or

(5) a diagnosis of suicide attempt or deliberate self-harm (ICD-10: X60–X84).

Please note, that we considered only the first recorded episode of self-harm from the list above.

Data sources

Data for the study was based on a total of four national Danish registers:

(1) The Danish Civil Registration System (CRS) (Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2011) was initiated in 1968 and holds information on every individual in Denmark through a unique identification number (CRS number). This identification number allows linkage of information on individuals within and between registries. We included data on CRS number, gender, date of birth, vital status, data on all children and the women's parents from this register.

(2) The Danish Psychiatric Central Register (PCR) (Mors et al., Reference Mors, Perto and Mortensen2011) includes data on all admissions to psychiatric inpatient facilities in Denmark since it was established in 1969. Information on all outpatient contacts to psychiatric facilities was added to the register from 1995. Therefore, we were able to identify information on psychiatric inpatient and outpatient contacts for the women included in the cohort. Additionally, we included data on any psychiatric contacts the women's parents might have had from 1969 and onwards, allowing us to adjust our analyses for confounding of family history of mental illness.

(3) The Danish National Patient Register (NPR) (Lynge et al., Reference Lynge, Sandegaard and Rebolj2011) provided data on all medical inpatient contacts to hospitals in Denmark from 1 January 1977 and onward. Information on outpatient contacts was added to the registry from 1 January 1995. This register allowed us to identify hospital records of self-harm among the women included in our cohort. Therefore, starting inclusion of women born from 1963 and onwards ensured complete follow-up information on the outcome of interest from the age of 15 years (start of follow-up) in 1978 for all women in the cohort. Furthermore, this register allowed us to draw information on parental self-harm and thereby the possibility to adjust for family history of self-harm in at least one parent.

(4) The Danish Register of Causes of Death (Helweg-Larsen, Reference Helweg-Larsen2011) was computerized in 1970 and provides data on all causes of death among Danish citizens dying in Denmark. This register contained the data necessary to define specifically suicides (ICD-10: X60–X84; ICD-8: E950–E959) as the cause of death among the women in our cohort as well as parental suicides. Hereby, we were able to adjust our analyses for suicide of at least one parent.

Until 31 December 1993 the diagnostic system used in Denmark was the ICD-8 (World Health Organization, 1976), and from 1 January 1994 the ICD-10 system was introduced (World Health Organization, 2016).

Definition of reference and comparison groups

For our main analysis, the defined reference group consisted of mothers from the healthy background population, giving birth to their first child with no records of a psychiatric diagnosis either before or after childbirth.

In additional analyses, we compared the risk of self-harm among women with PPMD to other groups of women with varying status of mental health and motherhood. This addition of further comparison groups was done to examine how mental health and motherhood influences the risk of both self-harm and suicide (Appleby and Turnbull, Reference Appleby and Turnbull1995; Johannsen et al., Reference Johannsen, Larsen, Laursen, Bergink, Meltzer-Brody and Munk-Olsen2016). Consequently, all women in the cohort were classified into a total of five groups in a time-dependent variable depending on their mental health and parity status throughout the follow-up period:

(1) Mothers with PPMD. This was defined as any first inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility within 90 days after giving birth to their first child.

(2) Mothers without mental disorders (reference group). This consisted of women with no registered history of contact to a psychiatric facility and who have given birth to at least one child.

(3) Mothers with a diagnosis of mental disorder occurring outside the postpartum period. This was defined as women who have given birth to their first child and have a first inpatient or outpatient psychiatric contact outside the 90-day postpartum period (either before or after).

(4) Childless women with mental disorders. This consisted of women with any first inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility without any record of childbirth.

(5) Childless women without mental disorders. This consisted of women without any record of contact to a psychiatric facility and without any record of childbirth.

When defining group 1 (mothers with PPMD) as the first-ever inpatient or outpatient contact within the short time-period of 90 days after giving birth, we assumed that childbirth was the specific trigger causing the psychiatric episode (Munk-Olsen et al., Reference Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Pedersen, Mors and Mortensen2006; Munk-Olsen et al., Reference Munk-Olsen, Jones and Laursen2014).

Please note that implementation of these five time-dependent variables enabled dynamic classifications where the women could transition between groups and contribute person-time to different comparison groups throughout the course of follow-up-time depending on when and if they had their first psychiatric contact and its possible relation to the potential birth of a first-born child (for further description see online Supplementary Appendix 1). Furthermore, our analysis built on the assumption that the specific dates of first psychiatric inpatient or outpatient contact and childbirth mark a change in group membership category. As a consequence, any potential prodromal phase leading up to the onset of mental disorders are not taken in to account, as is the case with any study design including time-dependent co-variates. Further, we conducted a sensitivity analysis of our main analysis expanding the onset of PPMD from the first 3months (90 days) after giving birth to 6 months postpartum (180 days).

Statistical analysis

We conducted survival analyses with hazard ratios (HRs) as the main outcome measure, using Cox regression in Stata, version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex.). Age was chosen as the underlying time in all analyses as is customary in these types of studies with register-based Cox regression. Further, all analyses were adjusted for calendar time as a time-dependent variable. Further, we adjusted for the time-dependent variables of family history of mental disorder, parental self-harm and parental suicide defined as any psychiatric inpatient or outpatient contact, any hospital recorded episode of self-harm or death categorized as suicide among either of the women's parents.

Analysis of short-term v. long-term risk of self-harm

In order to specifically study the short v. the long-term risk of self-harm following a diagnosis of PPMD, we conducted a subanalysis calculating specific HRs for the risk of receiving a first-ever hospital record for self-harm up to 12 months after first inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility as well as first-ever self-harm episode beyond the first 12 months after diagnosis. These HRs were compared to the risk of first-ever self-harm episode of mothers without any record of self-harm in the entire time-period from 1963 to 2016.

Analysis of suicide risk following a self-harm episode

In order to investigate our secondary aim of describing the risk of suicide among those with a history of self-harm, we conducted a sub-analysis on the sub-cohort of women registered with an episode of self-harm throughout the follow-up period. Here each woman was followed from the date of their first hospital-registered self-harm until the date of suicide, date of death by other causes or December 2016, whichever came first.

Results

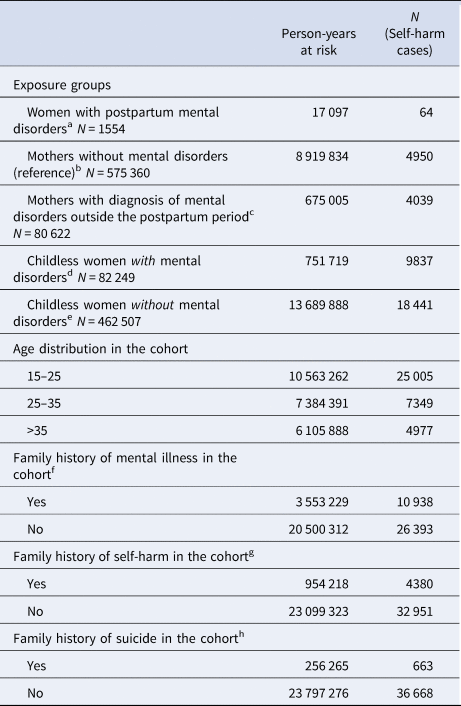

A total of 1 202 292 Danish women were included in our study cohort representing 24 053 543 person-years at risk throughout the entire follow-up period. We identified 1554 mothers with first onset PPMD (Table 1) i.e. experiencing first psychiatric outpatient or inpatient contact to a psychiatric facility within 90 days after giving birth to their first child. Among the mothers with PPMD, we identified 64 women who had a first-ever hospital record of self-harm following their diagnosis.

Table 1. Characteristics of the cohort presented with person-years at risk and number of self-harm cases

a Women with any first psychiatric inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility within 90 days after giving birth to her first child.

b Women with a record of childbirth but without any record of a psychiatric inpatient or outpatient contact.

c Women with a record of childbirth and an inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility outside the 90-day postpartum period.

d Women without any record of childbirth but with a first inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility.

e Women without any record of childbirth and without any record of an inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility.

f At least one mother and/or father with a record of inpatient or outpatient psychiatric treatment.

g At least one mother and/or father with a hospital registered episode of self-harm.

h At least one mother and/or father dying from suicide.

Among the 64 women with first onset PPMD and a hospital record of self-harm following their diagnosis, the majority were diagnosed with anxiety or stress-related mental disorders (n = 20, 31.3%) or affective mood disorders (n = 18, 28.1%) in the postpartum period. Six (9.4%) women had a schizophrenia or schizotypal disorder, and five (7.81%) women had diagnoses of mental and behavioral disorders associated with the puerperium. The remaining 15 (23.43%) women were recorded having other diagnoses including personality disorders.

Table 1 further shows the characteristics of the cohort in term of age-distribution, parental history of mental illness, self-harm and/or suicide presented as person-years at risk and number of self-harm cases.

Risk of self-harm

The adjusted HR of self-harm was 6.2 (95% CI 4.9–8.0) i.e. the risk was higher in women with first onset PPMD, compared to mothers from the healthy general population without mental disorders. However, when compared to both childless women and mothers with a mental disorder outside the postpartum period, women with PPMD had a lower risk of self-harm. More precisely, the risks for self-harm were: HR 10.1 (95% CI 9.6–10.5) for mothers with mental disorders occurring outside the postpartum period and 9.3 (95% CI 8.9–9.7) in childless women with mental disorders (see Table 2).

Table 2. Adjusted hazard ratios for self-harm in women with postpartum mental disorders and four comparison groups

a Adjusted for calendar time and family history of mental illness, family history of self-harm and family history of suicide.

b Women with any first psychiatric inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility within 90 days after giving birth to her first child.

c Women with a record of childbirth but without any record of a psychiatric inpatient or outpatient contact.

d Women with a record of childbirth and an inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility outside the 90-day postpartum period.

e Women without any record of childbirth but with a first inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility.

f Women without any record of childbirth and without any record of an inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility.

In our sensitivity analysis with the onset of PPMD expanded to 6 months (180 days) after childbirth, we found almost identical results (see online Supplementary Appendix 2).

Timing of self-harm after diagnosis

Table 3 shows the short-term and long-term risk of self-harm among women with PPMD compared to the lifetime risk of self-harm in mothers from the background population without mental disorders. Overall, risk of self-harm was highest in close proximity to the time of diagnoses – the HR of self-harm within the first 12 months after PPMD diagnosis was 13.5 (95% CI 8.4–21.7) among women with PPMD (n = 17 women). After the initial 12 months this risk decreased: HR 5.2 (95% CI 3.9–6.9) (n = 47 women).

Table 3. Short-term v. long-term risk of self-harm among women with postpartum mental disorders and four comparison groups

a Number of women with the first record of self-harm within the first 12 months after first psychiatric inpatient or outpatient contact.

b Adjusted for age, calendar time, family history of mental illness, family history of self-harm and family history of suicide.

c Number of women with the first record of self-harm after 12 months following first psychiatric inpatient or outpatient contact.

d Women with any first psychiatric inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility within 90 days after giving birth to her first child.

e Women with a record of childbirth but without any record of a psychiatric inpatient or outpatient contact.

f Women with a record of childbirth and an inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility outside the 90-day postpartum period.

g Women without any record of childbirth but with a first inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility.

h Women without any record of childbirth and without any record of an inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility.

Risk of recurrent episodes of self-harm and suicide

In total 33 (51.5%) of the 64 cases of self-harm in women with PPMD had at least one hospital record of subsequent self-harm during the follow-up period. 48.4% of the women self-harmed more than once, with eight individuals (12.5%) having more than four hospital registered episodes of self-harm (results not shown).

The HR for suicide after an episode of self-harm in women with first onset PPMD compared to mothers without a mental disorders was 8.7 (95% CI 3.5–21.7) (see Table 4). Furthermore, women with PPMD had a significantly higher risk of suicide than the other groups of women with mental disorders – both when compared with mothers with non-PPMD (HR 2.7; 95% CI 1.9–3.7; p value = 0.0104) and childless women with mental disorders (HR 2.8; 95% CI 2.1–3.8; p value = 0.0125).

Table 4. Survival analysis showing the risk of suicide among the women with at least one hospital registered episode of self-harm in five comparison groups

a Women with at least one hospital record of self-harm who later died by completed suicide.

b Hazard ratio adjusted for age, calendar time, family history of mental illness, family history of self-harm and family history of suicide.

c Women with any first psychiatric inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility within 90 days after giving birth to her first child.

d Women with a record of childbirth but without any record of a psychiatric inpatient or outpatient contact.

e Women with a record of childbirth and an inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility outside the 90-day postpartum period.

f Women without any record of childbirth but with a first inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility.

g Women without any record of childbirth and without any record of an inpatient or outpatient contact to a psychiatric facility.

Discussion

Using register data covering the entire Danish population, we found that women with first-onset PPMD are at increased risk of self-harm compared with mothers from the healthy background population. Nevertheless, their risk of self-harm was the lowest among all comparison groups of women with mental disorders – both mothers and non-mothers. Importantly, we further found that a record of self-harm among women with PPMD was associated with the significantly highest risk of later suicide among all the comparison groups.

Risk of self-harm in mothers with PPMD

This present study is, the first population-based study to describe the incidence of self-harm among women with first-onset PPMD. Primiparous women experiencing PPMD within the first 90 days postpartum had an increased risk of hospital contact due to self-harm, which was approximately 6 times higher than in mothers without mental disorders.

Previous studies have reported increased rates of suicidal ideation among women in the postpartum period (Lindahl et al., Reference Lindahl, Pearson and Colpe2005; Wisner et al., Reference Wisner, Sit, Mcshea, Rizzo, Zoretich, Hughes, Eng, Luther, Wisniewski, Costantino, Confer, Moses-Kolko, Famy and Hanusa2013), using data from a specific question relating to thoughts of self-harm (question 10) in the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in women with PPMD (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky1987; Lindahl et al., Reference Lindahl, Pearson and Colpe2005; Wisner et al., Reference Wisner, Sit, Mcshea, Rizzo, Zoretich, Hughes, Eng, Luther, Wisniewski, Costantino, Confer, Moses-Kolko, Famy and Hanusa2013). While the EPDS is a highly valid tool in identifying high risk patients for postpartum depression and questions regarding suicidal behavior (thoughts of self-harm and/or suicide) are included (Adouard et al., Reference Adouard, Glangeaud-Freudenthal and Golse2005; Rubertsson et al., Reference Rubertsson, Borjesson, Berglund, Josefsson and Sydsjo2011), for this study we used a much more specific instrument in evaluating suicidal behavior as we were able to identify women who had actually acted on potential self-harming impulses. One previous study has described an increased risk of self-harm among pregnant women with pre-existing mental disorders (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Van Ravesteyn, Van Denberg, Stewart and Howard2016). However, so far no studies have described the extent to which women with first onset PPMD act on such thoughts of self-harm.

Risk of self-harm compared to other groups of psychiatric patients

Motherhood, in general, appears to be a protective factor in terms of reducing self-harm, suicidal ideation, and mortality (Appleby and Turnbull, Reference Appleby and Turnbull1995; Johannsen et al., Reference Johannsen, Larsen, Laursen, Bergink, Meltzer-Brody and Munk-Olsen2016; Lysell et al., Reference Lysell, Dahlin, Viktorin, Ljungberg, D'onofrio, Dickman and Runeson2018). However, mental disorders constitute a well-established major risk factor for self-harm (Christiansen et al., Reference Christiansen, Larsen, Agerbo, Bilenberg and Stenager2013) and may, therefore, add to the complexity of the risk evaluation for suicidal and self-harming behavior in new mothers. In this present study, we considered various states of mental ill-health (absent, postpartum, non-postpartum) and also motherhood (mothers, non-mothers), by using multiple comparison groups of women drawn from the background population. The risk of self-harm in women with PPMD was increased (HR 6.2; 95% CI 4.9–8.0) when compared to mothers without any record of psychiatric admissions. While our results confirmed a generally increased risk of self-harm in the three groups of women with mental disorders (both mothers and childless women), in our more detailed analyses we found that women with a diagnosis of PPMD had the lowest risk of hospital recorded contacts due to self-harm involving hospital contact when compared to groups of women with alternate onset of mental disorders (both mothers and childless women). These results indicate important clinical variations in self-harm risks, related to both mental health and motherhood.

Self-harm as risk factor for later suicide in women with PPMD

Self-harm is one of the leading risk factors for later suicide (Cavanagh et al., Reference Cavanagh, Carson, Sharpe and Lawrie2003; Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Metcalfe and Gunnell2014; Runeson et al., Reference Runeson, Haglund, Lichtenstein and Tidemalm2016; Olfson et al., Reference Olfson, Wall, Wang, Crystal, Gerhard and Blanco2017). This was also confirmed in the present study, where women suffering from PPMD with records of self-harm had significantly highest risk of later suicide amongst all comparison groups (HR 8.7; 95% CI 3.5–21.7), including women with onset of mental disorders at alternate time points (both mothers and childless women). These results add to the already worrying evidence suggesting that women with the most severe forms of mental disorders following childbirth are at significantly increased risk of dying by suicide, especially within the first year after diagnosis (Appleby et al., Reference Appleby, Mortensen and Faragher1998; Johannsen et al., Reference Johannsen, Larsen, Laursen, Bergink, Meltzer-Brody and Munk-Olsen2016; Khalifeh et al., Reference Khalifeh, Hunt, Appleby and Howard2016; Lysell et al., Reference Lysell, Dahlin, Viktorin, Ljungberg, D'onofrio, Dickman and Runeson2018). An additional aspect is that women who do exhibit suicidal behavior in the postpartum period are more likely to use violent methods when dying by suicide and thereby possibly indicating a higher suicidal intent (Appleby, Reference Appleby1991; Lindahl et al., Reference Lindahl, Pearson and Colpe2005; Esscher et al., Reference Esscher, Essen, Innala, Papadopoulos, Skalkidou, Sundstrom-Poromaa and Hogberg2016). Unfortunately, we were not able to stratify our analysis on violent v. non-violent methods of self-harm and/or suicide due to lack of statistical power.

Clinical perspectives

Our results demonstrate that women with PPMD who have a hospital record of self-harm following their psychiatric diagnosis, constitute a selected group of high-risk patients for later suicide. These results must, however, be considered alongside the observation that absolute number of women with first onset PPMD who self-harm and commit suicide are low (five women in the present study). Regardless, every single case represents a significantly increased relative risk among this specific group of vulnerable new mothers, which is clinically significant.

Our results also show that the first year following initial diagnosis carries the highest risk of self-harm for women with PPMD (see Table 3), which indicates a particular at-risk period. Hence, goals for future research projects should be aimed at tools for early identification of women: (1) who will develop the first onset PPMD following childbirth and (2) who are at risk of self-harm and suicidal behaviors, in order to identify them before they act on such impulses.

Strengths and limitations

This study was based on information from the national Danish health registers. In Denmark there is free and equal access both to medical and mental health care and every individual treated is registered by CPR-number (Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2011). This way we were able to ensure a representative study population, and thus minimize selection bias.

We aimed to investigate types of PPMD, and consequently defined these as disorders requiring inpatient and outpatient contacts to specialized psychiatric treatment facilities. While information of inpatient treatment was available throughout the entirety of the study period data on outpatient contact were added to the national Danish registers from 1995 and onwards. Some women from the comparison groups of women without mental disorders (mothers and non-mothers) might have received treatment for mild-moderate mental disorders at their general practitioners without treatment being registered in the Danish Psychiatric Central Register and this information would therefore not be captured in our data. However such possible misclassification would lead to an underestimation of the risk of self-harm and suicide, rather than dilute our findings.

As self-harm is often stigmatized all uncertainties regarding the correct coding of self-harm as a deliberate act v. an accident cannot be ruled out completely. We applied a Danish developed algorithm for defining self-harm (Gasse et al., Reference Gasse, Danielsen, Pedersen, Pedersen, Mors and Christensen2018) which includes a more general spectrum of self-harm and could capture accidental injuries (e.g. overdose).

However, this potential misclassification bias would again lead to an underestimation of the prevalence of later suicide, as some deaths recorded as being accidental may have in fact been suicides, rather than dilute our findings.

The women included in this study were born from 1963 and followed until the year 2016. As a consequence, our cohort mainly consisting of younger women, illustrated with 17 947 653 (74.6%) of the person-years at risk within the age groups under 35 years (Table 1). This age distribution potentially limits generalizability of our results to older mothers. However, as it has been shown that self-harming behavior is especially prominent among younger individuals (Abdelraheem et al., Reference Abdelraheem, McAloon and Shand2019) we do believe that our study population is suitable for answering the study questions proposed.

We adjusted for possible confounding from age, family history of mental disorders and family history of suicidal behavior from both parental self-harm and/or suicide in our analyses, however, as in any observational study, we cannot rule out possible residual confounding.

Conclusion

Women with the most severe PPMD registered with a specialized psychiatric treatment have an increased risk of self-harm following their initial postpartum diagnosis when compared to mothers without a history of psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. However, among all groups of psychiatric patients (both mothers and childless women with alternate onset of mental disorders) women with PPMD have the lowest risk of self-harm.

Nevertheless, the particular concern should be focused on women with PPMD with a record of self-harm, as this group represents a clinical cohort with a significantly increased risk of subsequent suicide.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719001661

Author ORCIDs

Trine Munk-Olsen, 0000-0002-0786-7147.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIMH (National Institute of Mental Health) grant number: R01MH104468 and an unrestricted grant from the Lundbeck Foundation (grant number: R155-2012-11280)